Abstract

Using twenty sectors of TESS observations and the hitherto unutilized radial velocities from the David Dunlap Observatory survey, we fully characterize the close binary TV UMi. Its nearly sinusoidal light curves are well explained by a low-inclination, shallowly-eclipsing model in marginal contact, with a dark spot whose longitudinal migration is strongly correlated with the eclipse time variations. We derive the orbital parameters of the binary and determine the masses and radii of the components with a precision of a few percent. The estimated age and the position of TV UMi on the theoretical HR diagram indicate it’s a relatively young late-type contact binary of the W subtype.

1. Introduction

A large fraction (20–30%) of eclipsing binaries are contact systems [1,2], where the component stars are close enough to form a stable and long-lived co-rotating common envelope. Because the common envelope fills a Roche surface, the ratio of the component radii is proportional to the ratio of the component masses [3]; that is, the more massive star must necessarily be the larger. This unique property of contact binaries allows, in principle, the determination of the mass ratio from photometric light curves. Absolute parameters of the stars and the orbital parameters of the system can then be estimated even in the absence of velocity curves, which are necessary for full characterization of non-contact binaries.

In the era of large survey astronomy, photometric light curves are abundant, but velocity curves remain a rare commodity; only a small fraction (about two hundred) of contact binaries have been characterized using radial velocities as well as light curves [4]. In this modest sample, a major contribution was made by the David Dunlap Observatory (hereafter DDO) radial velocity survey [5], which remains incompletely utilized.

One of the stars observed in the DDO survey for which no combined photometric and spectroscopic solution has been published to date is TV UMi (, , , ): a close binary with an almost sinusoidal light curve and a visual companion that complicates both photometric and spectroscopic measurements. The companion is itself an eccentric, spectroscopic binary with an orbital period of about 31 days [6], making TV UMi a quadruple system and all the more astrophysically interesting. The components of the wide system were resolved in 2018 with the separation of [7,8]. It has been matched with a ROSAT X-ray source by Haakonsen and Rutledge [9].

The optical variability of TV UMi was examined by Selam [10], who used the HIPPARCOS photometry to classify the system as a contact binary and obtain an estimate of its orbital parameters with the simplified light curve synthesis method of Rucinski [11]. The photometric mass ratio resulting from this analysis () is much smaller than the spectroscopic value obtained by Pribulla et al. [6] (), which is not surprising given the very low inclination and the absence of obvious eclipses.

In this work, we use the abundant TESS [12] observations in combination with the DDO radial velocities to completely characterize TV UMi. The TESS data and their reduction are described in Section 2. The radial velocities are taken from Pribulla et al. [6], who measured them using the broadening function technique [13]. As our analysis shows, TV UMi is a shallowly eclipsing, marginal-contact W UMa binary of the W subtype with a dark spot of likely magnetic origin.

Apart from standard simultaneous modeling of the phase-binned light curve and the velocity curve (detailed in Section 3), we also model each individual orbital cycle present in the TESS observations and establish the correlation between longitudinal spot migration and eclipse time variations. Finally, we place the components of TV UMi on the HR diagram in Section 4, estimate its age and compare it to a selection of similar contact binaries.

2. TESS Light Curves

The TESS data were obtained from the MAST Portal1 using the lightkurve 2.52 Python package [14]. We selected the observations made at the two-minute cadence throughout 20 TESS sectors, making for about 323,000 individual observations over 1138 orbital cycles, of which 1027 have complete phase coverage.

Orbital phases were calculated with the ephemeris given in the next subsection. Data from different TESS sectors were stitched into a single light curve as follows: in every sector, the PDCSAP flux and its corresponding error were divided by the maximal value of a parabola fitted through the phase-folded light curve maximum between phases 0.24 and 0.26, resulting in normalized flux values. For the purpose of modeling, we phase-binned the resulting light curve to 1000 normal points.

Eclipse Times and the Updated Ephemeris

We measured the eclipse times from the TESS data by fitting a parabola through each minimum. Using these measurements and the initial period reported by Pribulla et al. [6], we updated the ephemeris for TV UMi as follows:

The eclipse time measurements are given in Table 1.

Table 1.

Eclipse times from TESS observations.

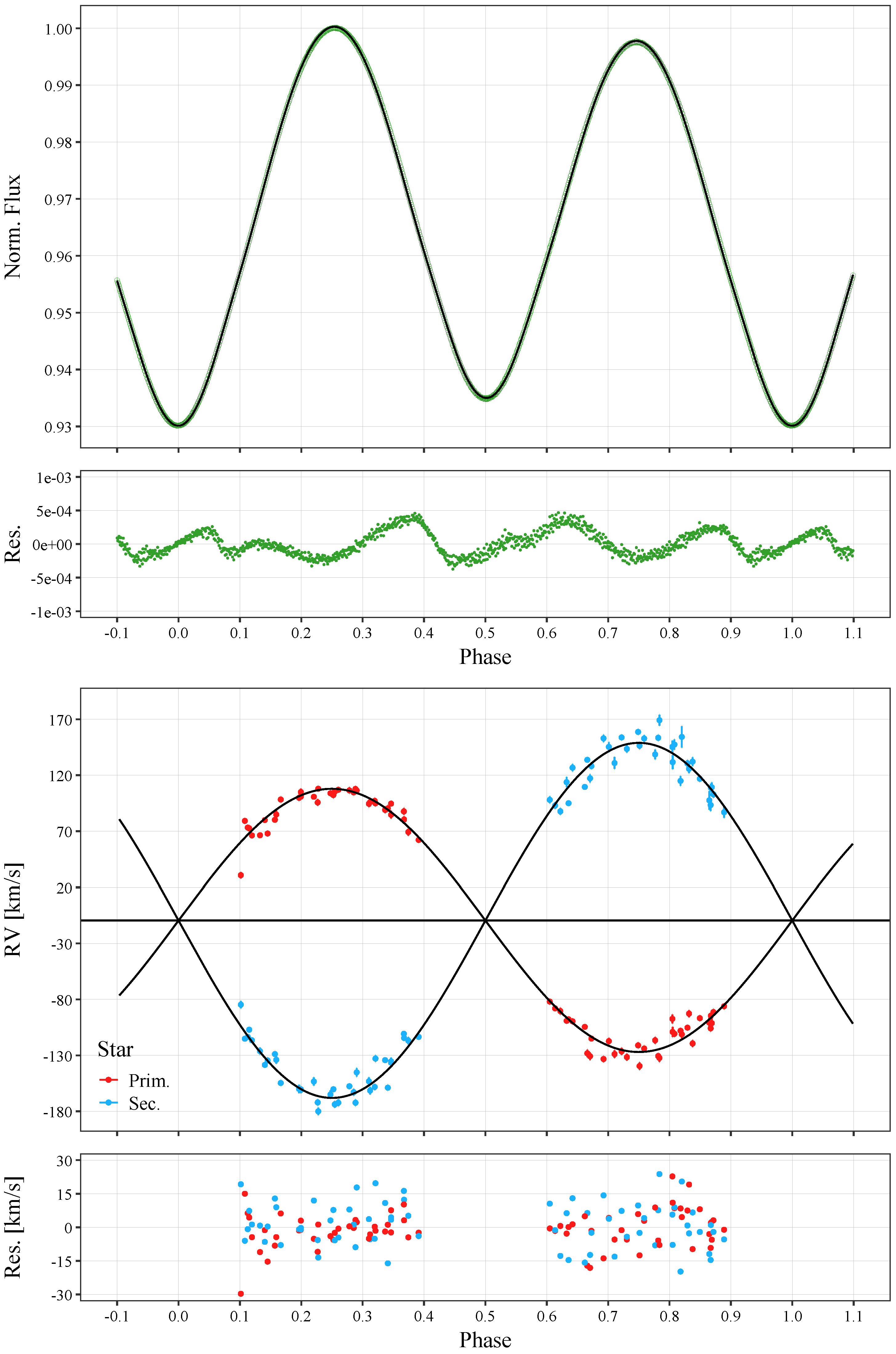

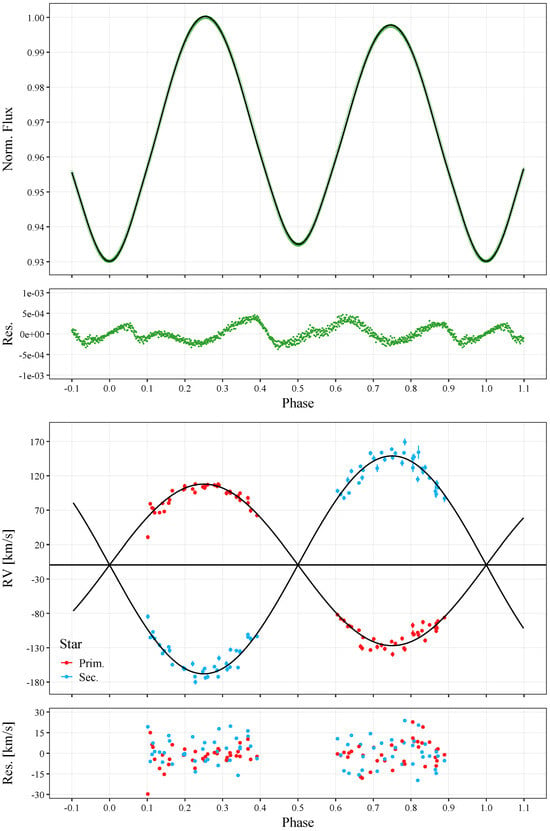

Note that the radial velocities in Pribulla et al. [6] were phased with a different ephemeris, where the shallower eclipse was taken as the point of reference corresponding to phase 0. In the current work, the deeper minimum corresponds to phase 0. Thus, there is a phase shift of 0.5 between the radial velocities shown in Figure 3 of Pribulla et al. [6] and those shown in Figure 1 of the present work.

Figure 1.

(Top): the light curve of TV UMi. The phase-binned TESS observations are plotted as green circles, and the best-fitting model (detailed in Table 2) is plotted as a black line. The circle size is indicative of the mean observational error (≈0.0004). (Bottom): the velocity curves of TV UMi. The observed radial velocities from Pribulla et al. [6] are plotted as red dots for the primary, and as blue dots for the secondary star, and the best-fitting model is plotted as a black line. The residuals between the observations and the model are shown below the corresponding plots.

Table 2.

Model parameters and derived quantities. The range pertains to the upper and lower limits of free parameters during model optimization.

Table 2.

Model parameters and derived quantities. The range pertains to the upper and lower limits of free parameters during model optimization.

| Quantity | Value | Error | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3.037 | 0.030 | 1–10 | |

| q | 0.7411 | 0.0030 | 0.7–0.8 |

| −9.55 | 0.50 | −30–30 | |

| 48.28 | 0.59 | 30–60 | |

| 6152 | 200 | ||

| 6336 | 365 | 5500–7500 | |

| 1.0033 | 0.0029 | 1.0–1.1 | |

| 0.4405 | 0.0043 | 0.0–0.5 | |

| Phase Shift (LC) | 0.4984 | 0.0013 | 0.4–0.6 |

| Phase Shift (RV) | 0.5486 | 0.0010 | 0.4–0.6 |

| Dimensionless surface potential | 3.3063 | 0.0088 | |

| Degree of overcontact [%] | 2.1 | 1.8 | |

| Spot on the Primary Star | |||

| 0.9770 | 0.0037 | 0.9–1.0 | |

| Angular Radius | 27.9 | 2.5 | 10–45 |

| Longitude | 150 | 35 | 0–360 |

| Latitude | 18 | 15 | −90–90 |

| Absolute Parameters | |||

| 1.254 | 0.038 | ||

| 0.929 | 0.028 | ||

| 1.240 | 0.016 | ||

| 1.080 | 0.015 | ||

| 1.95 | 0.51 | ||

| 1.68 | 0.48 | ||

| 4.3493 | 0.0028 | ||

| 4.3393 | 0.0029 | ||

| 117.43 | 0.40 | ||

| 158.46 | 0.44 |

3. Modeling

The analysis of the light and velocity curves was done with the modernized version of the program described in Djurasevic [15] and Djurasevic et al. [16], that calculates a numerical model of a close binary system where the stars are represented as Roche surfaces. The model outputs synthetic light curves by summing the flux contributions from elementary surfaces whose visibility at each phase of the orbital motion depends on the orbit inclination and the relatives sizes of the stars. The flux contributions are calculated in the blackbody approximation, taking in consideration various second-order effects, such as the limb-darkening, gravity darkening and mutual irradiation. The original code was extensively modified for automated computing of large numbers of models in parallel (see e.g., [17]), and expanded to allow the synthesis and fitting of velocity curves.

One or more spots may be present on each star. In this model, the spots are circular and parametrized with angular coordinates, radius and the temperature ratio of the affected elementary surfaces with and without the spot. The inclusion of spots in the models of eclipsing binaries is often necessary to account for the asymmetry of the light curve knows as the O’Connell effect [18], where one of the maxima is notably higher than the other, which implies surface brightness inhomogeneity. Spots may be hotter (bright) or cooler (dark) than the unaffected star surface.

In the case of TV UMi, the inclusion of one spot is sufficient to account for the light curve asymmetry. We place it on the cooler of the two components, as it is more likely to exhibit magnetic activity. Alternate models, with multiple spots and with a single spot on the hotter star, were considered and rejected because they did not produce superior fits to the observations.

We fit the light and velocity curves simultaneously. The following parameters are free during model optimization: the mass ratio (q); the orbital separation (a); the center of mass velocity (); the orbital inclination (i); the filling factor (the ratio of the star’s polar radius to the polar radius of the critical Roche lobe) of the primary star (); the effective temperature of the secondary star (); the third light, ; the phase shifts of the light curve and the velocity curve; and the spot parameters: the longitude (), latitude (), angular size () and the temperature contrast of affected elementary surfaces, . The parameter space of spot locations, sizes and temperatures was explored using additional model grids.

The temperature of the primary star was fixed to the value from the tabulations in Eker et al. [19] for a star of spectral type F8 (), as classified by Pribulla et al. [6]. The gravity-darkening exponents and the albedos were fixed to the theoretical values appropriate for stars with convective envelopes: and [20,21,22]. The limb-darkening was calculated using a four-term law with filter-specific coefficients from Claret [23]. We consider the rotation of the components synchronized with the orbital motion.

The final model parameters obtained by fitting the phase-binned light curve and the velocity curves are given in Table 2. The errors are the standard deviations from the ensemble of models for individual cycles (discussed in detail in the next section), with the exception of , for which we assume an uncertainty of 200 K roughly corresponding to the range between spectral classes F7 and G0 in the tabulations of Eker et al. [19]. The observations and the model are shown in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

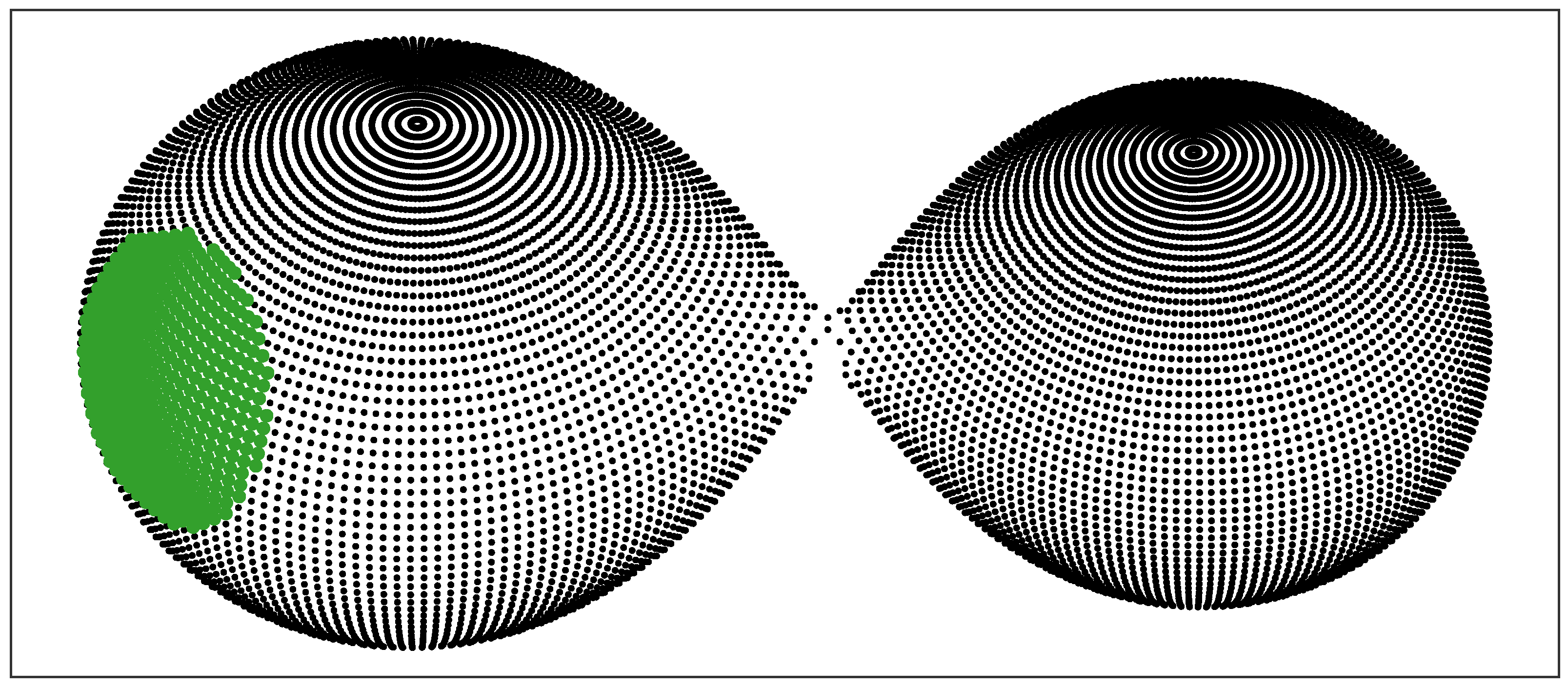

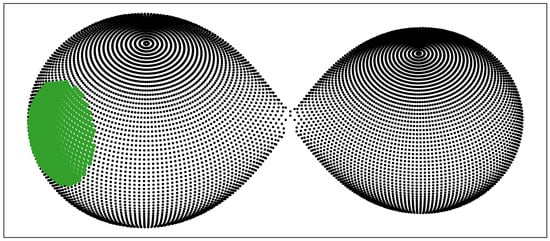

Figure 2.

The 3D representation of the model for TV UMi. The spot is plotted with larger, green dots.

Models of Individual Orbital Cycles

Apart from modeling the phase-binned light curve of TV UMi, we also modeled each of the 1027 orbital cycles with complete phase coverage present in the TESS data as separate light curves, using the phase-binned model as the starting point, but otherwise in the same manner (the same parameters were allowed to vary or were fixed). This procedure provides an ensemble of models that can be used to estimate the precision of the model parameters and the derived quantities, similarly to the bootstrap method. At the same time, it provides a time series of model parameters that can be analyzed for evidence of significant variation.

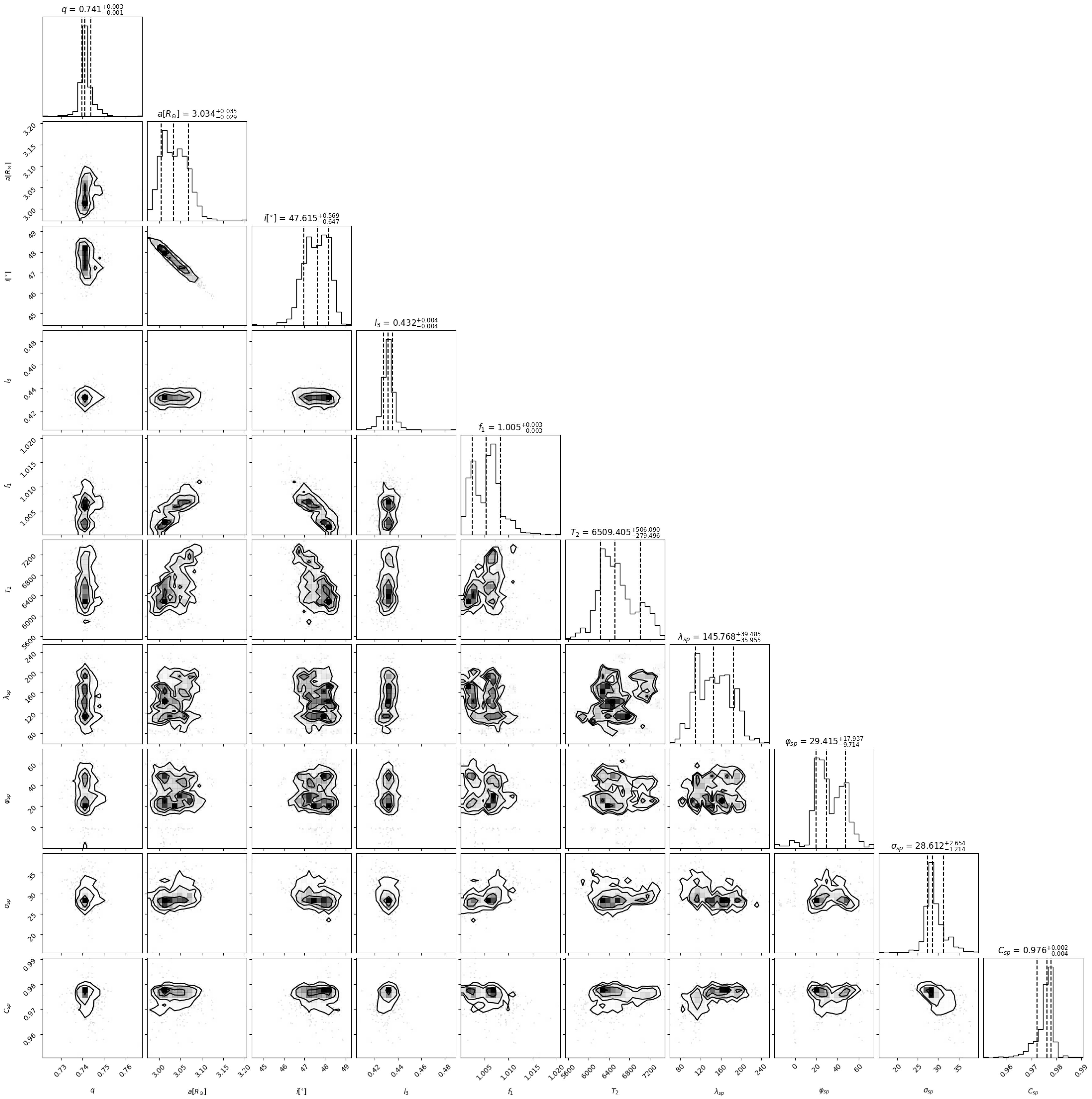

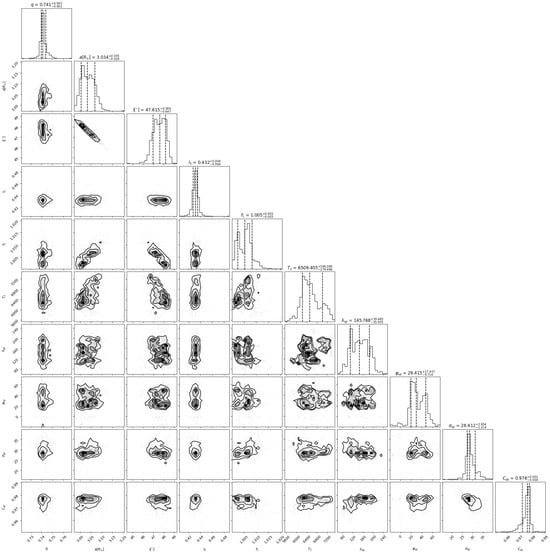

As can be seen from Table 2, most of the model parameters change only slightly from cycle to cycle, except for the spot parameters, whose locations vary over a wide range, and the secondary temperature. This can also be seen in the corner plot constructed from the ensemble of individual cycle models, given in Figure 3, which shows that the parameters determining the configuration of the system are very well constrained.

Figure 3.

The corner plot obtained from the ensemble of individual cycle models.

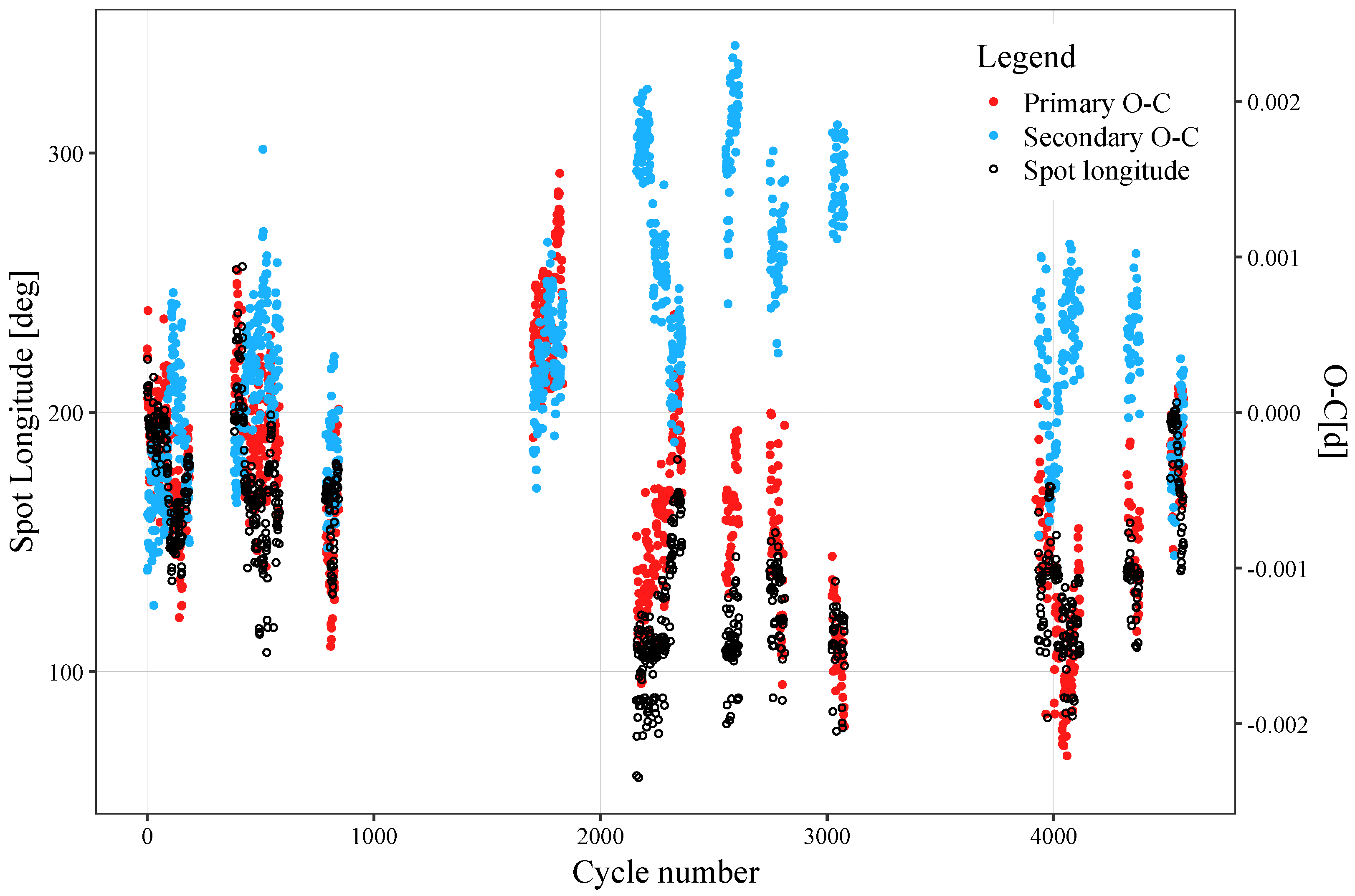

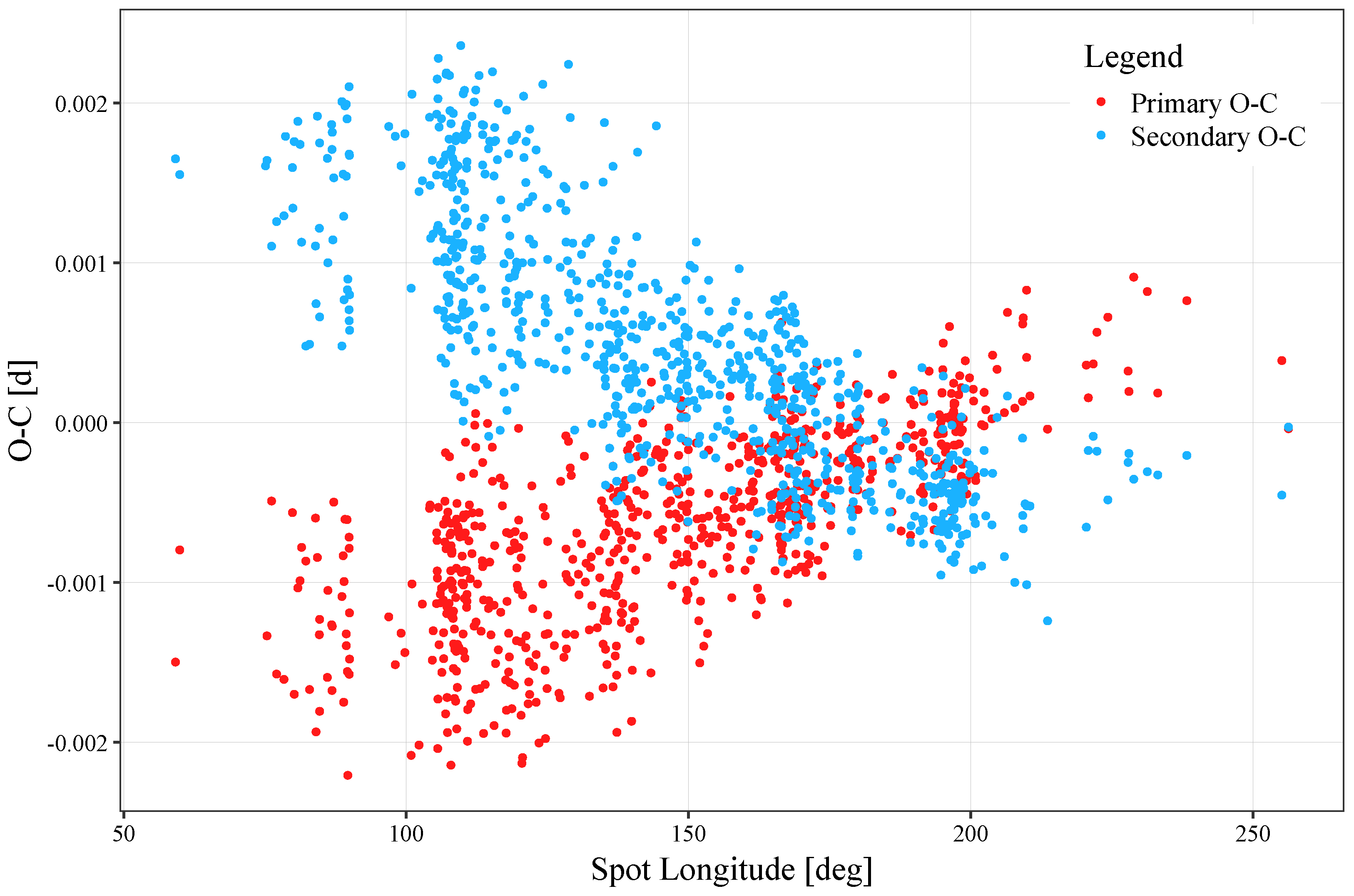

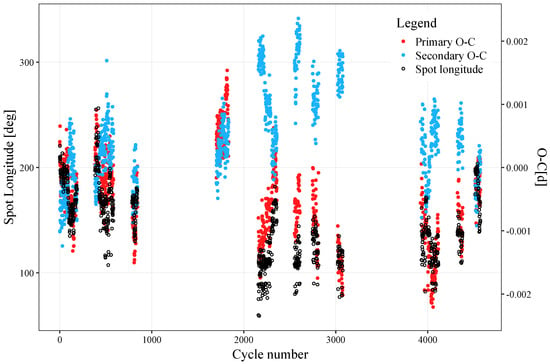

Plotting the spot longitude as a function of time together with the O-C residuals (OCR) in Figure 4 demonstrates a remarkable agreement between the longitude and primary eclipse OCR. Meanwhile, the secondary eclipse OCR appear anti-correlated with both the spot longitude and the primary eclipse OCR. This is an expected observational signature of spot migration according to Tran et al. [24], who found anti-correlated primary and secondary OCR in a sample of contact binaries observed by the Kepler space telescope and explained it with a simplified model of a spotted binary. This phenomenon was further analyzed and confirmed in our previous works [17,25].

Figure 4.

Eclipse time variations (red dots for the primary, and blue for the secondary eclipse), plotted together with the variation of spot longitude (black circles). Cycles 1600–1900 show no O’Connell effect, so we modeled them without a spot, which is why the measurements of spot longitude are missing from that region of the plot.

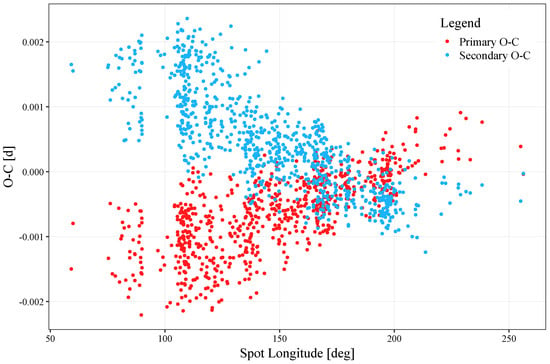

The apparent (anti-)correlation with the (secondary) primary OCR in the case of TV UMi is further demonstrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Eclipse time variations (red dots for the primary, and blue for the secondary eclipse) as a function of spot longitude.

4. Discussion

The interpretation of the results presented above is complicated by the fact that TV UMi is a quadruple system. However, the analysis of the contact binary is sound regardless of the signature of the non-eclipsing member in the observations:

The radial velocities we use were measured with the broadening function technique, where the non-eclipsing member was clearly distinguished from the components of the contact binary [6], and therefore, does not affect the radial velocities and the orbital parameters of the contact pair.

The contamination of the photometric observations by the non-eclipsing member is accounted for by the third light parameter (), which represents constant additional flux. Our estimate of the third light, , is in excellent agreement with the spectroscopic estimate from Pribulla et al. [6] (, which would correspond to ). As the companion binary is non-eclipsing and has a period two orders of magnitude longer than the contact binary, its contribution to the light curve of TV UMi could be considered as constant; but even if it has some variability of its own, that too would be accounted for by the third light in the individual cycle models. While we do not find significant variation of the third light across cycles, we cannot rule out that such variability exists.

Based on the arguments above, we conclude that the characterization of the contact binary is reliable despite its membership in a multiple system.

Although the light curve of TV UMi appears to be entirely sinusoidal, the best-fitting model suggests a low-inclination system with shallow eclipses and spots causing the O’Connell effect.

Throughout this work, we observe the convention that the larger and more massive star is denoted with the index 1 and referred to as the primary, and the smaller, less massive star is denoted with the index 2 and referred to as the secondary. The mass ratio is defined as and is always less than unity.

According to these definitions and the ephemeris given in Equation (1), in TV UMi, the secondary star is eclipsed in the deeper minimum at phase 0. This situation corresponds to the W subtype of W UMa binaries defined by Binnendijk [26], where the smaller, less massive secondary appears to be hotter than the larger, more massive primary.

With the mass ratio of , TV UMi belongs to the H subtype of W UMa stars defined by Csizmadia and Klagyivik [27]. Latković et al. [28] found that H stars have lower temperatures, shorter periods, and smaller fillouts than non-H stars. Compared to the summary statistics given in the same paper, TV UMi has a temperature higher than average, a period that’s also slightly longer than the average, but its fillout is smaller than 90% of the sample presented by Latković et al. [28] (hereafter, WUMaCat).

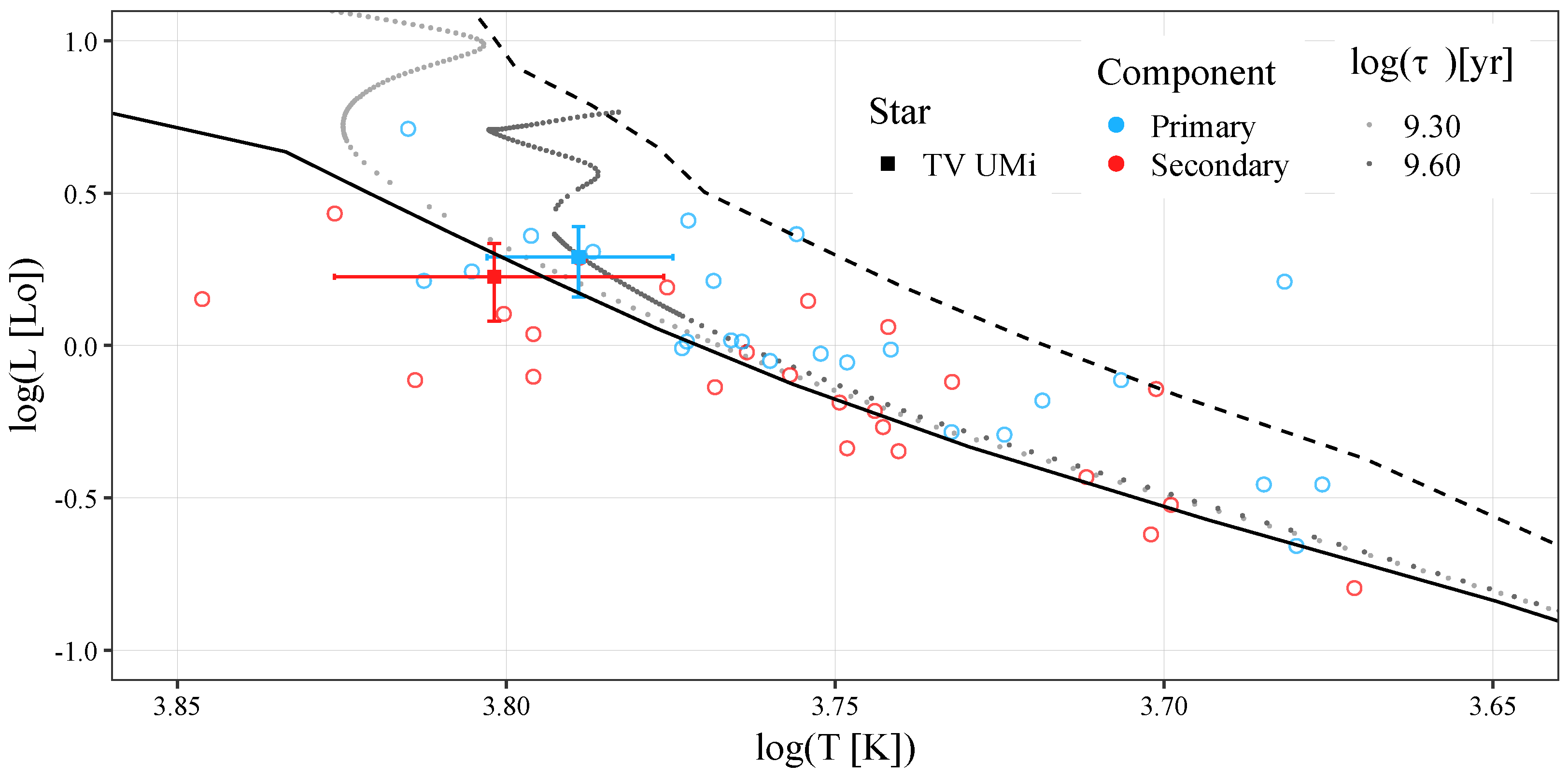

Following the method of age calculation for W UMa binaries developed by Yildiz and Doğan [29] and Yıldız [30], as detailed in Appendix A of Latković et al. [28], we estimate the age of TV UMi at Gy, which makes it younger than 90% stars with age estimates in WUMaCat.

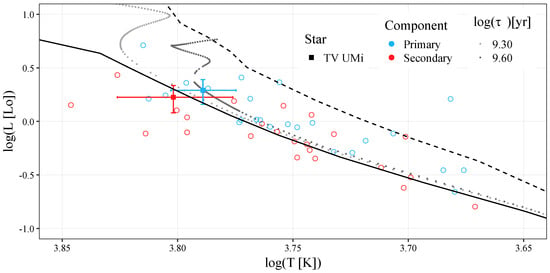

Figure 6 shows TV UMi on the theoretical Hertzsprung-Russell diagram (HRD) with a selection of similar systems found in WUMaCat (listed in Table 3). The figure also shows the zero-age main sequence (ZAMS), the terminal-age main sequence (TAMS), and selected isochrones from the MIST grid of evolutionary models [31,32,33] for rotating stars (rot=vvcrit0.4) and solar metallicity (feh=p0.00). The isochrone corresponding to the age of the system as estimated above () lies below the primary of TV UMi, which is instead best described by the isochrone corresponding to , or Gy. The discrepancy is significant, even when considering the upper limit of the age estimate from the absolute parameters, of Gy. However, this is not surprising, because the MIST models were made for single stars, and as a contact binary, TV UMi can be expected to deviate from single-star evolution.

Figure 6.

The HRD showing the components of TV UMi (filled squares) together with a selection of similar stars (empty circles) listed in Table 3. The primaries are plotted with blue symbols, and the secondaries with red. Also plotted are the ZAMS (solid black line) and the TAMS (dashed black line), as well as two isochrones: one for the age of the system calculated from its absolute parameters, corresponding to (light gray dotted line), and the one that best fits the position of the primary of TV UMi, corresponding to (dark gray dotted line). The ZAMS, TAMS and the isochrones are taken from the MIST grid of evolutionary models [31,32,33].

Table 3.

Contact binaries similar to TV UMi in order of increasing period. All the quantities are taken from Latković et al. [28]. The masses, radii and luminosities are in solar units.

We assumed that a dark spot on the larger (and cooler) star is responsible for the visible O’Connell effect. The usual interpretation of such spots in close binaries is that they are of magnetic origin, because the tidal spin-orbit synchronization compels the stars to rotate much faster than they would if they were single, and fast rotation produces stronger magnetic fields. Our cycle-by-cycle analysis showed that the spot migrates, and that its longitudinal motion is strongly correlated with the eclipse timing variations.

5. Conclusions

The combined analysis of TESS light curves and velocity curves from the DDO survey shows that TV UMi is a young ( Gy) shallowly eclipsing ( marginal contact binary (degree of contact of 2.1%) of the W subtype, with a large mass ratio (), an F7-G1 primary and a G6-K0 secondary. The masses and radii of the components are determined with a precision of a few percent. Eclipse time variations are found to be strongly correlated with the longitudinal migration of a large, dark spot on the primary star. Although we could detect no period change over the five years of TESS observations, continued monitoring of eclipse times might reveal whether the system is evolving towards deeper contact or a detached configuration, and help characterize the orbital motion of the quadruple system it belongs to.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Č. and O.L.; methodology, A.Č. and O.L.; software, A.Č.; investigation. A.Č.; validation, O.L.; data curation, O.L.; writing—original draft preparation, A.Č.; writing—review and editing, O.L.; visualization, O.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Ministry of Science, Technological Development and Innovation of Republic of Serbia under the grant number 451-03-136/2025-03/200002.

Data Availability Statement

The full dataset with eclipse times whose preview is given in Table 1 is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.18411807 (accessed on 28 January 2026). TESS data are available for download through the MAST portal. The intermediate results of the analyses (e.g., the parameters of the individual cycle models) may be made available on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

This work has made frequent use of the Simbad database at http://simbad.u-strasbg.fr/simbad/ (accessed on 28 January 2026), operated at the CDS, Strasbourg, France, and NASA’s Astrophysics Data System Bibliographic Services at http://adsabs.harvard.edu/ (accessed on 28 January 2026). We acknowledge the extensive use of the R programming language [55] and of the ggplot plotting package [56]. Figure 3 was generated using the cornerplot Python package [57]. We are grateful to the anonymous referees for the careful reading of the manuscript and the constructive feedback that helped improve it.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| DDO | David Dunlap Observatory |

| MAST | Barbara A. Mikulski Archive for Space Telescopes |

| HRD | Hertzsprung-Russell Diagram |

| ZAMS | Zero-Age Main Sequence |

| TAMS | Terminal-Age Main Sequence |

| OCR | O-C Residuals |

Notes

| 1 | https://mast.stsci.edu/portal/Mashup/Clients/Mast/Portal.html (accessed on 28 January 2026) |

| 2 | https://lightkurve.github.io/lightkurve/ (accessed on 28 January 2026) |

References

- Głowacki, M.; Soszyński, I.; Udalski, A.; Szymański, M.K.; Skowron, J.; Skowron, D.M.; Mróz, P.; Pietrukowicz, P.; Poleski, R.; Kozłowski, S.; et al. The OGLE Collection of Variable Stars. Over 75 000 Eclipsing and Ellipsoidal Binary Systems in the Magellanic Clouds. Acta Astron. 2024, 74, 241–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.H.; Li, K.; Gao, X.; Guo, Y.N.; Sun, G.Y. Using Machine Learning Method for Variable Star Classification Using the TESS Sectors 1–57 Data. Astrophys. J. 2025, 986, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuiper, G.P. On the Interpretation of β Lyrae and Other Close Binaries. Astrophys. J. 1941, 93, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latković, O.; Čeki, A. Light curve analysis of six totally eclipsing W UMa binaries. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 2021, 73, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerbeck, H.W.; Rucinski, S.M. Radial Velocity Studies of Southern Close Binary Stars. II. Spring/Summer Systems. Astron. J. 2007, 133, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pribulla, T.; Rucinski, S.M.; Lu, W.; Mochnacki, S.W.; Conidis, G.; Blake, R.M.; DeBond, H.; Thomson, J.R.; Pych, W.; Ogłoza, W.; et al. Radial Velocity Studies of Close Binary Stars. XI. Astron. J. 2006, 132, 769–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mason, B.D.; Wycoff, G.L.; Hartkopf, W.I.; Douglass, G.G.; Worley, C.E. The 2001 US Naval Observatory Double Star CD-ROM. I. The Washington Double Star Catalog. Astron. J. 2001, 122, 3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochsenbein, F.; Bauer, P.; Marcout, J. The VizieR database of astronomical catalogues. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. 2000, 143, 23–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haakonsen, C.B.; Rutledge, R.E. XID II: Statistical Cross-Association of ROSAT Bright Source Catalog X-ray Sources with 2MASS Point Source Catalog Near-Infrared Sources. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2009, 184, 138–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selam, S.O. Key parameters of W UMa-type contact binaries discovered by HIPPARCOS. Astron. Astrophys. 2004, 416, 1097–1105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, S.M. A Simple Description of Light Curves of W UMa Systems. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 1993, 105, 1433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ricker, G.R.; Winn, J.N.; Vanderspek, R.; Latham, D.W.; Bakos, G.Á.; Bean, J.L.; Berta-Thompson, Z.K.; Brown, T.M.; Buchhave, L.; Butler, N.R.; et al. Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS). J. Astron. Telesc. Instruments Syst. 2015, 1, 014003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rucinski, S. Determination of Broadening Functions Using the Singular-Value Decomposition (SVD) Technique. In Proceedings of the IAU Colloquium 170: Precise Stellar Radial Velocities, Victoria, BC, Canada, 21–26 June 1998; Hearnshaw, J.B., Scarfe, C.D., Eds.; Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series; Astronomical Society of the Pacific: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1999; Volume 185, p. 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lightkurve Collaboration; Cardoso, J.V.d.M.; Hedges, C.; Gully-Santiago, M.; Saunders, N.; Cody, A.M.; Barclay, T.; Hall, O.; Sagear, S.; Turtelboom, E.; et al. Lightkurve: Kepler and TESS Time Series Analysis in Python. Astrophysics Source Code Library. Available online: https://ascl.net/1812.013 (accessed on 28 January 2026).

- Djurasevic, G. An Analysis of Active Close Binaries/CB/Based on Photometric Measurements-Part One-a Model of Active CB with Spots on the Components. Astrophys. Space Sci. 1992, 196, 241–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Djurasevic, G.; Zakirov, M.; Hojaev, A.; Arzumanyants, G. Analysis of the activity of the eclipsing binary WZ Cephei. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. Ser. 1998, 131, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latković, O.; Čeki, A. Combined light curve and radial velocity analysis of the neglected contact binary S Ant. New Astron. 2024, 113, 102291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connell, D.J.K. The so-called periastron effect in eclipsing binaries (summary). Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1951, 111, 642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eker, Z.; Bakış, V.; Bilir, S.; Soydugan, F.; Steer, I.; Soydugan, E.; Bakış, H.; Aliçavuş, F.; Aslan, G.; Alpsoy, M. Interrelated main-sequence mass-luminosity, mass-radius, and mass-effective temperature relations. Mon. Not. R. Astron. 2018, 479, 5491–5511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Zeipel, H. The radiative equilibrium of a rotating system of gaseous masses. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1924, 84, 665–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucy, L.B. Gravity-Darkening for Stars with Convective Envelopes. Z. Fuer Astrophys. 1967, 65, 89–92. [Google Scholar]

- Ruciński, S.M. The Proximity Effects in Close Binary Systems. II. The Bolometric Reflection Effect for Stars with Deep Convective Envelopes. Acta Astron. 1969, 19, 245. [Google Scholar]

- Claret, A. Limb and gravity-darkening coefficients for the TESS satellite at several metallicities, surface gravities, and microturbulent velocities. Astron. Astrophys. 2017, 600, A30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran, K.; Levine, A.; Rappaport, S.; Borkovits, T.; Csizmadia, S.; Kalomeni, B. The Anticorrelated Nature of the Primary and Secondary Eclipse Timing Variations for the Kepler Contact Binaries. Astrophys. J. 2013, 774, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čeki, A.; Şenavcı, H.V.; Latković, O.; Uzunçam, E.; Yorulmaz, E.B.; Bahar, E. Comprehensive analysis of the eclipsing binaries V527 Dra and V2846 Cyg. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2024, 532, 3582–3603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binnendijk, L. The orbital elements of W Ursae Majoris systems. Vistas Astron. 1970, 12, 217–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Csizmadia, S.; Klagyivik, P. On the properties of contact binary stars. Astron. Astrophys. 2004, 426, 1001–1005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Latković, O.; Čeki, A.; Lazarević, S. Statistics of 700 Individually Studied W UMa Stars. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2021, 254, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildiz, M.; Doğan, T. On the origin of W UMa type contact binaries-a new method for computation of initial masses. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 430, 2029–2038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, M. Origin of W UMa-type contact binaries-age and orbital evolution. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 437, 185–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxton, B.; Marchant, P.; Schwab, J.; Bauer, E.B.; Bildsten, L.; Cantiello, M.; Dessart, L.; Farmer, R.; Hu, H.; Langer, N.; et al. Modules for Experiments in Stellar Astrophysics (MESA): Binaries, Pulsations, and Explosions. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2015, 220, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotter, A. MESA Isochrones and Stellar Tracks (MIST) 0: Methods for the Construction of Stellar Isochrones. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2016, 222, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.; Dotter, A.; Conroy, C.; Cantiello, M.; Paxton, B.; Johnson, B.D. Mesa Isochrones and Stellar Tracks (MIST). I. Solar-scaled Models. Astrophys. J. 2016, 823, 102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitrov, D.P.; Kjurkchieva, D.P. Ultrashort-period main-sequence eclipsing systems: New observations and light-curve solutions of six NSVS binaries. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2015, 448, 2890–2899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriwattanawong, W.; Sarotsakulchai, T.; Maungkorn, S.; Reichart, D.E.; Haislip, J.B.; Kouprianov, V.V.; LaCluyze, A.P.; Moore, J.P. A photometric analysis of the neglected EW-type binary V336 TrA. New Astron. 2018, 61, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, G.; Fisher, W.A.; Holmgren, D. Studies of late-type binaries. I. The physical parameters of 44i Bootis ABC. Astron. Astrophys. 1989, 211, 81–98. [Google Scholar]

- Kiron, Y.R.; Sriram, K.; Vivekananda Rao, P. CCD photometry of W UMa-type contact binaries in the old open cluster Berkeley 39. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2011, 11, 1469–1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deb, S.; Singh, H.P. Physical parameters of 62 eclipsing binary stars using the All Sky Automated Survey-3 data - I. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 412, 1787–1803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Hu, S.M.; Guo, D.F.; Jiang, Y.G.; Gao, D.Y.; Chen, X. The first photometric analysis and period investigation of the W UMa type binary system V1139 Cas. New Astron. 2015, 34, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baran, A.; Zola, S.; Rucinski, S.M.; Kreiner, J.M.; Siwak, M.; Drozdz, M. Physical Parameters of Components in Close Binary Systems: II. Acta Astron. 2004, 54, 195–206. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, K.; Yu, Y.X.; Zhang, J.F.; Xiang, F.Y. Long-term Photometry and Orbital Period Change of the W UMa-type Binary v0599 Aur: Evidence of about 11 yr Magnetic-activity Cycle. Astron. J. 2020, 160, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazeas, K.D.; Baran, A.; Niarchos, P.; Zola, S.; Kreiner, J.M.; Ogloza, W.; Rucinski, S.M.; Zakrzewski, B.; Siwak, M.; Pigulski, A.; et al. Physical Parameters of Components in Close Binary Systems: IV. Acta Astron. 2005, 55, 123–140. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, X.; Deng, L.; de Grijs, R.; Zhang, X.; Xin, Y.; Wang, K.; Luo, C.; Yan, Z.; Tian, J.; Sun, J.; et al. Physical Parameter Study of Eight W Ursae Majoris-type Contact Binaries in NGC 188. Astron. J. 2016, 152, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poro, A.; Halavati, A.; Lashgari, E.; Davoudi, F.; Gardi, A.; GholizadehSoghar, K.; Dashti, Y.; Mohammadizadeh, F.; Hedayatjoo, M. The First Light Curve Solution of GW Leo and Refined Ephemeris of Two Contact Binary Systems. Astron. Rep. 2021, 65, 543–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiron, Y.R.; Sriram, K.; Vivekananda Rao, P. A photometric study of contact binaries V3 and V4 in NGC 2539. Bull. Astron. Soc. India 2012, 40, 51. [Google Scholar]

- Kjurkchieva, D.P.; Popov, V.A.; Eneva, Y.; Petrov, N.I. The W UMa binaries USNO-A2.0 1350-17365531, V471 Cas, V479 Lac and V560 Lac: Light curve solutions and global parameters based on Gaia distances. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2019, 19, 014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjurkchieva, D.; Stateva, I.; Popov, V.A.; Marchev, D. Photometric and Spectral Observations of the W UMa Stars NSVS 4161544 and 1SWASP J034501.24+493659.9. GAIA Challenges. Astron. J. 2019, 157, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjurkchieva, D.P.; Popov, V.A.; Vasileva, D.L.; Petrov, N.I. Photometric observations and light curve solutions of the W UMa stars NSVS 2244206, NSVS 908513, CSS J004004.7+385531 and VSX J062624.4+570907. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 16, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanrıver, M. The first photometric solution and period variation of BG Vul binary star. New Astron. 2014, 28, 79–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, Y.C.; Jagirdar, R.; Joshi, S. Photometric studies of two W UMa type variables in the field of distant open cluster NGC 6866. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2016, 16, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özdemir, S.; Demircan, O.; Erdem, A.; Çiçek, C.; Bulut, İ.; Soydugan, E.; Soydugan, F. A photometric study of the recently discovered eclipsing binary V899 Herculis. Astron. Astrophys. 2002, 387, 240–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanti Priya, D.; Sriram, K.; Vivekananda Rao, P. Photometric study of an eclipsing binary in the field of M37. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2014, 14, 1166–1172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.W.; Li, L.F.; Jiang, D.K. A photometric study of the high-mass-ratio contact binary AV Puppis. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1906.02466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Lee, C.U.; Kim, S.L.; Kim, H.I.; Park, J.H. The Light and Period Variations of the Eclipsing Binary AA Ursae Majoris. Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 2011, 123, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Foreman-Mackey, D. corner.py: Scatterplot matrices in Python. J. Open Source Softw. 2016, 1, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.