Implementation of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Radio Telescope Control and Scheduling

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. The Radio Telescope Conversion Project

2.1.1. Antenna Specification

2.1.2. X-Y Pedestal System

2.1.3. Drivetrain Characteristics

2.2. Reinforcement Learning

The Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithm (PPO)

2.3. Simulated Environment

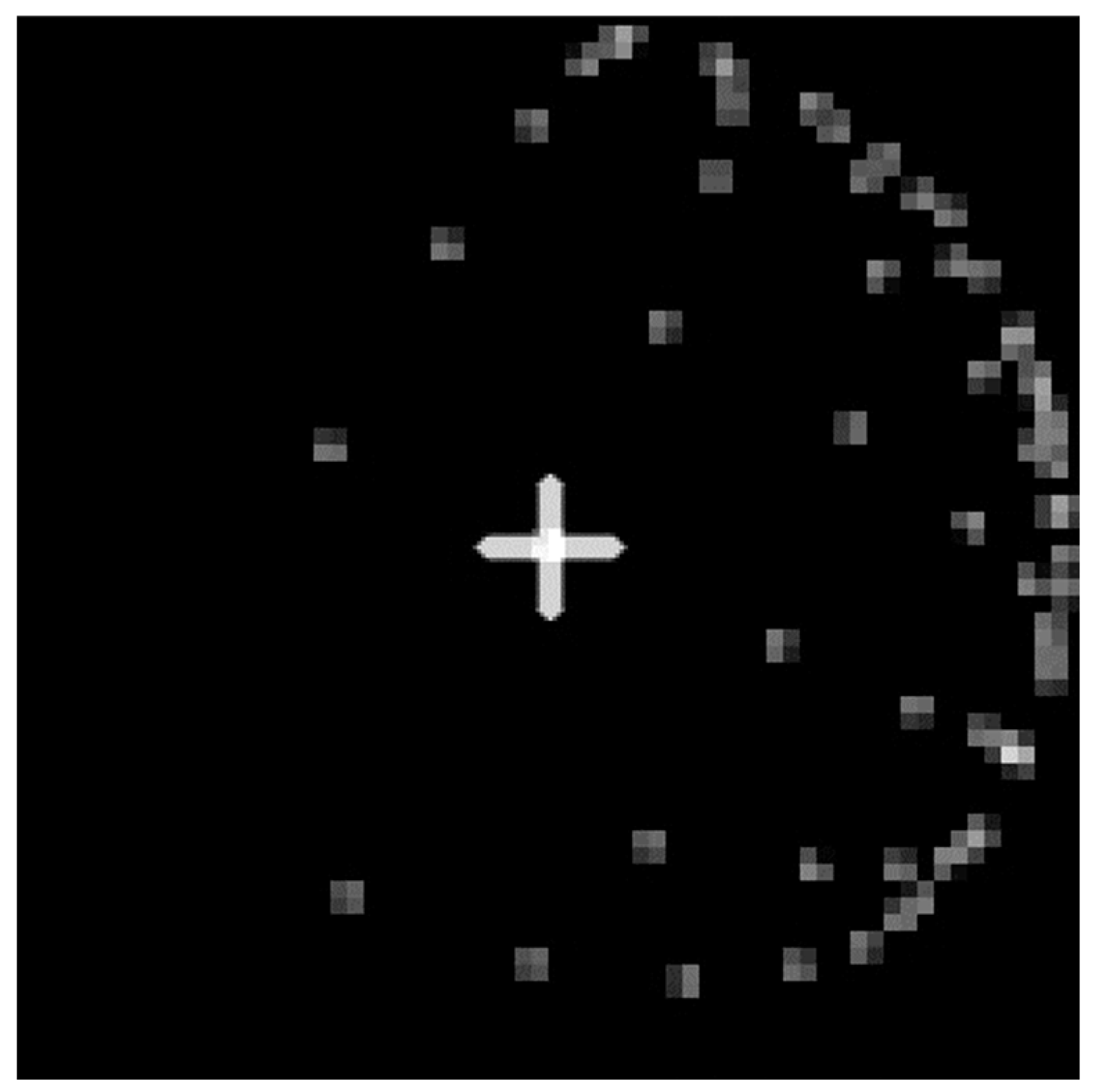

2.3.1. Observation Space

2.3.2. Action Space

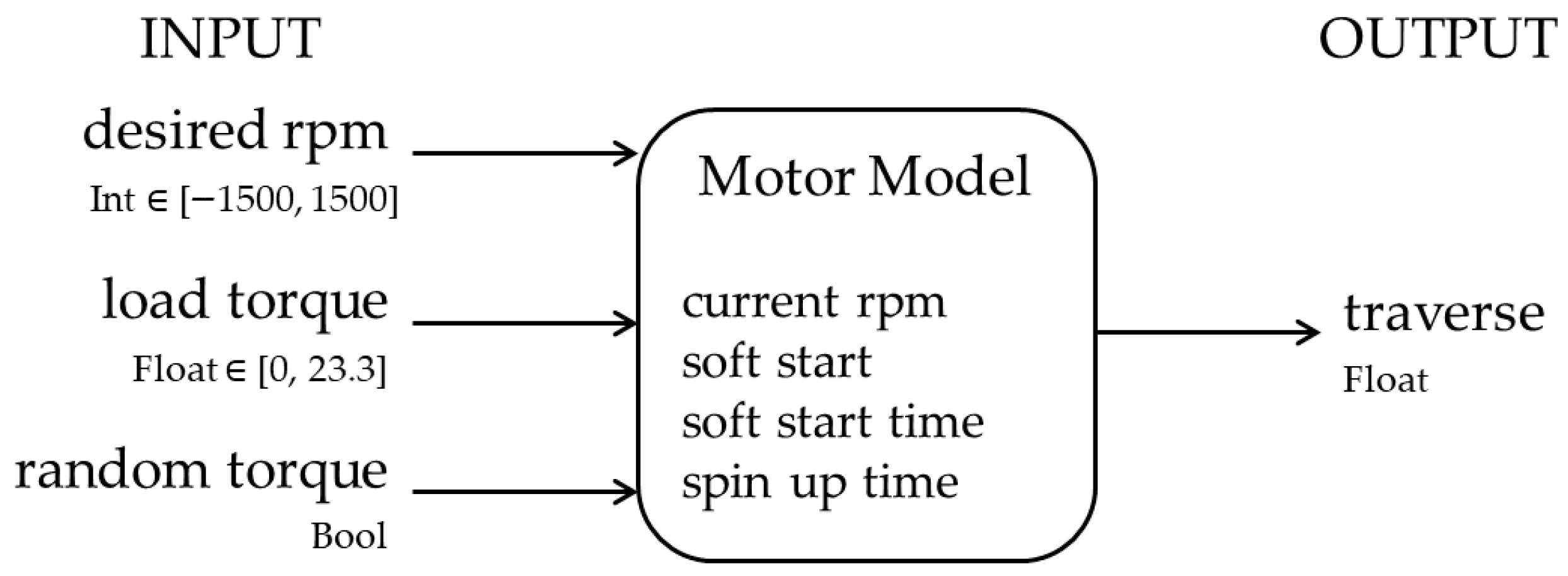

2.3.3. Telescope Model

2.4. Telescope Control Model

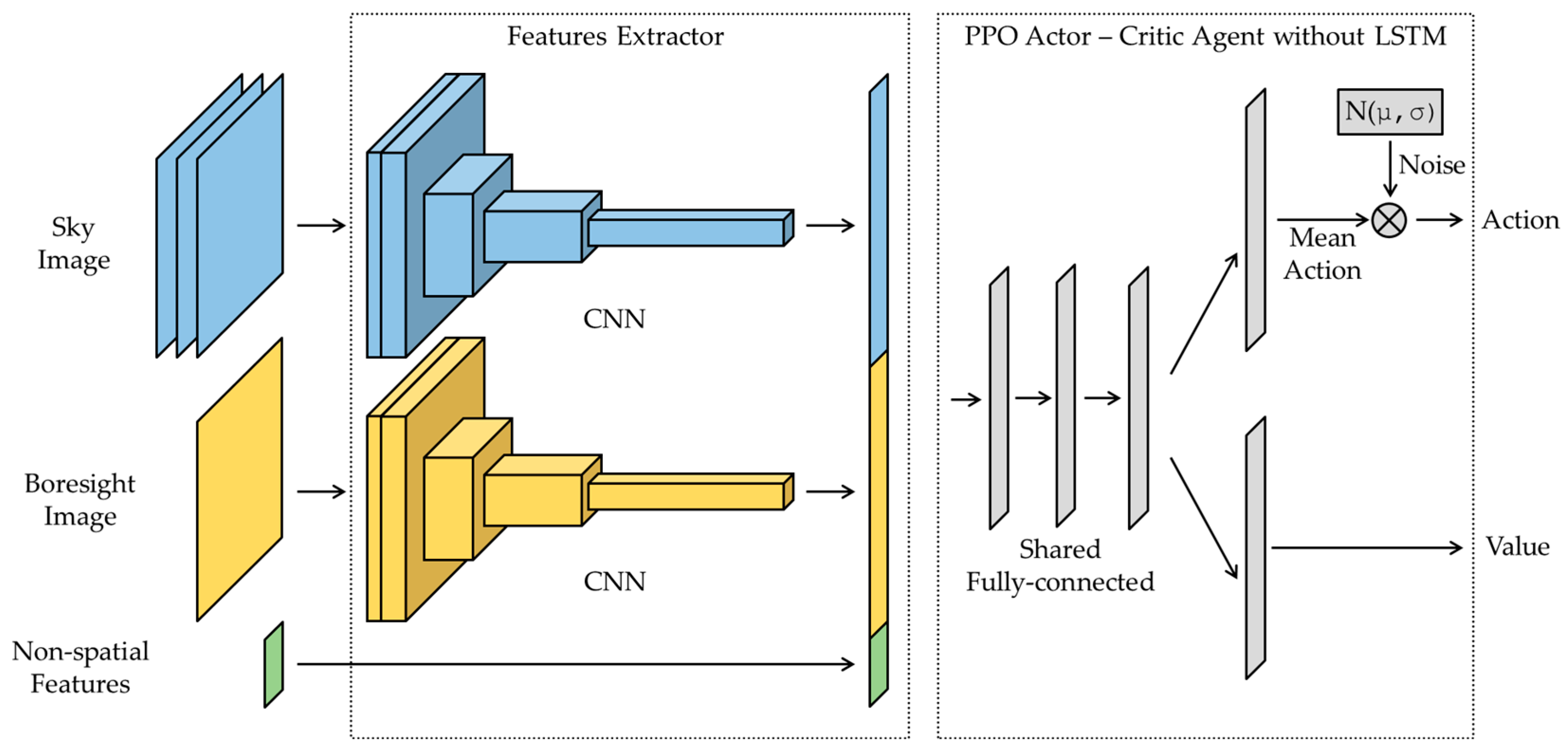

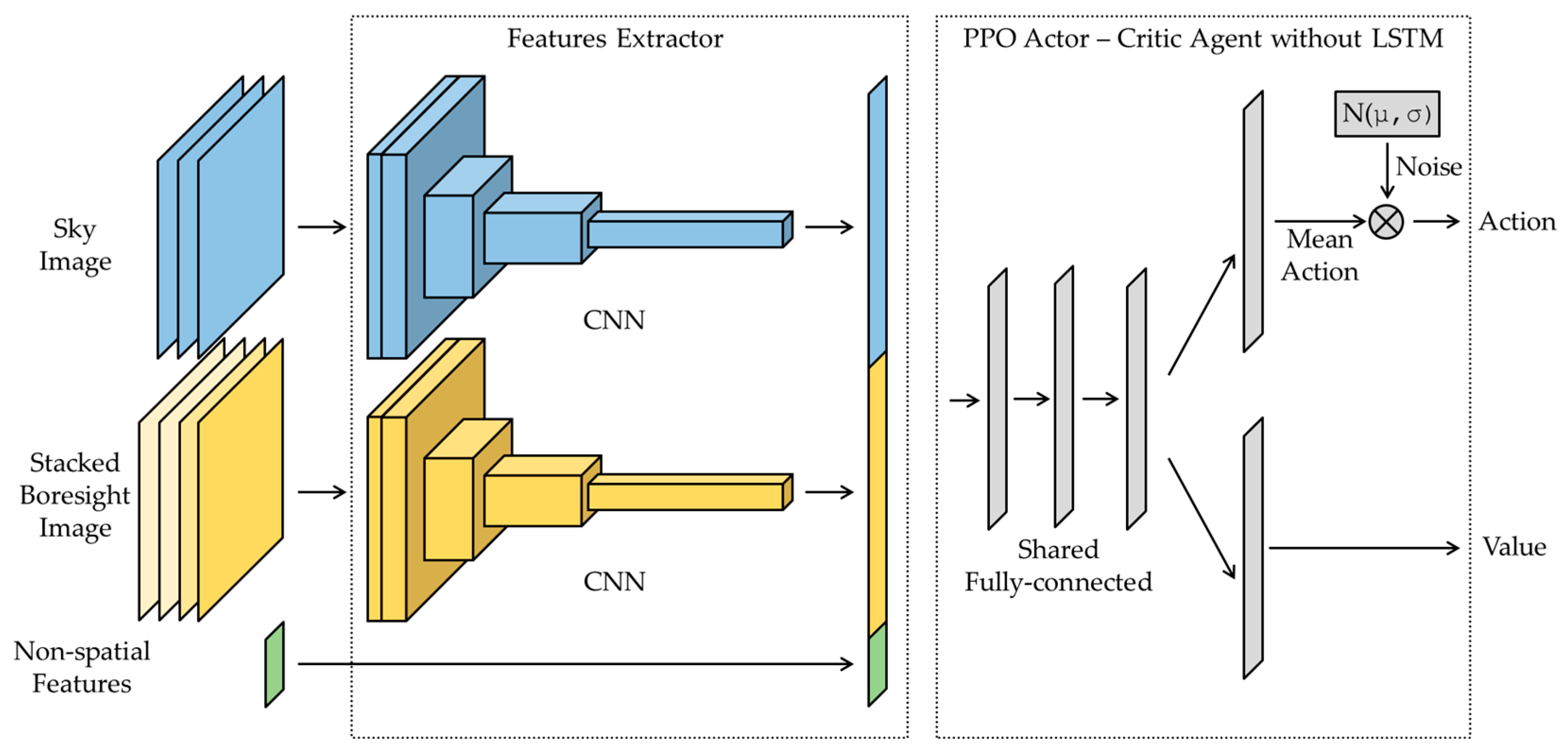

2.4.1. Model Structure

- Antenna location: the boresight’s local coordinates (X ∈ [−1, 1], Y ∈ [−1, 1]);

- Target cluster information: attributes for up to 8 target clusters, including their position, size, and obstructed status. Specifically, this consisted of cluster coordinates (X ∈ [−1, 1], Y ∈ [−1, 1]) and normalized cluster size (size ∈ [−1, 1]). Target clusters outside of the telescope horizon were masked out, and obstructed target clusters were given a negative size to encode their unobservable status.

2.4.2. Model Training

2.4.3. Reward Shaping

2.5. Evaluation

2.5.1. Performance Metrics

2.5.2. Feature Extractor Evaluation

2.5.3. Agent Evaluation

2.5.4. Real-World Performance

- Observation: The telescope boresight position was taken directly from the telescope encoders through UDP broadcast. Observation target coordinates were calculated in real time, and the obstacle layer was generated from real-time ADS-B feeds and weather radar.

- Action: The servomotor was configured to operate in speed control mode. The action output from the DRL agent was transmitted to the Servopack through a Modbus RTU analog output module. This analog output module transmitted a voltage signal in the range of [−3, 3] V, which corresponded to the servomotor’s operational rpm range of [−1500, 1500] rpm.

3. Results

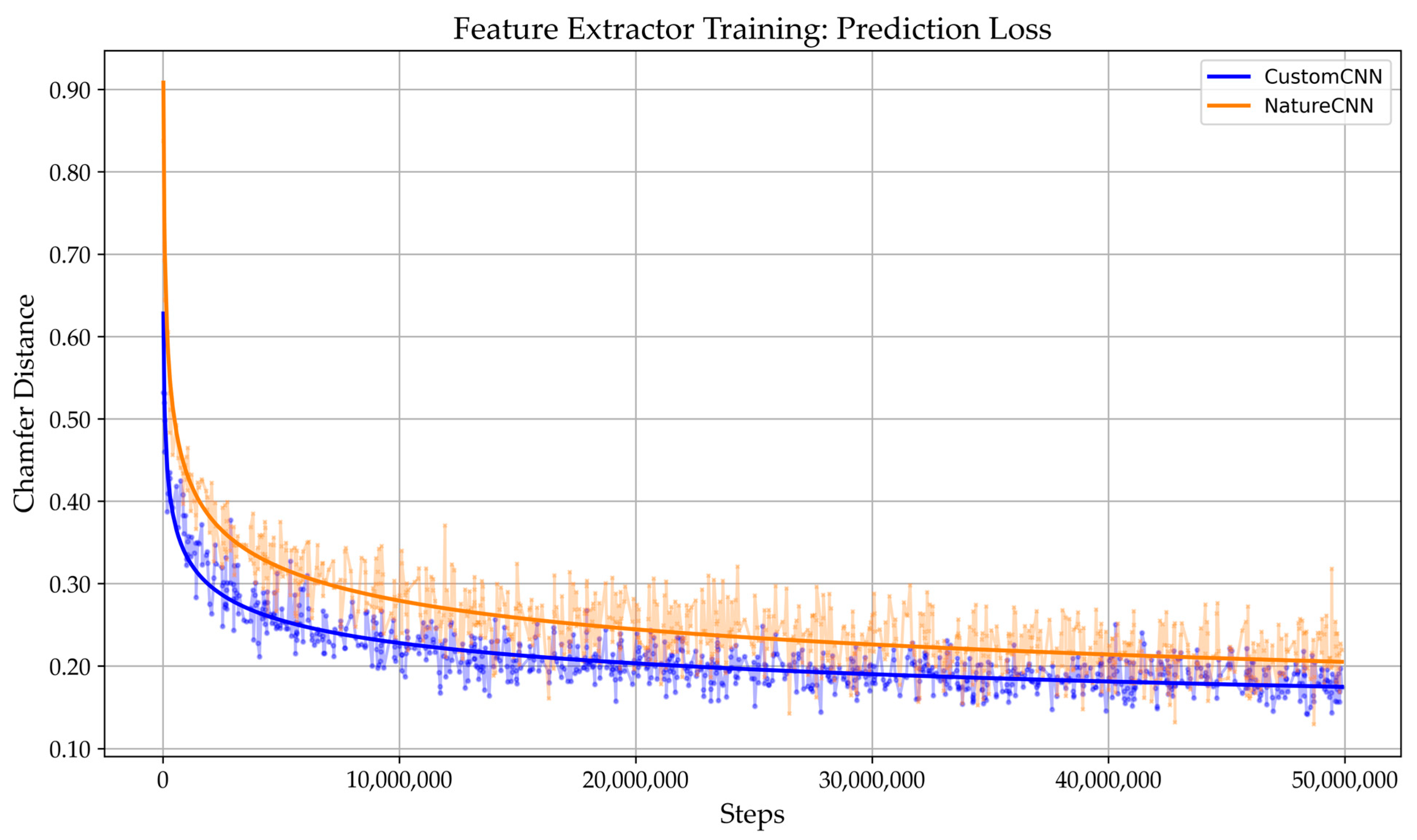

3.1. Performance of Feature Extraction Baselines

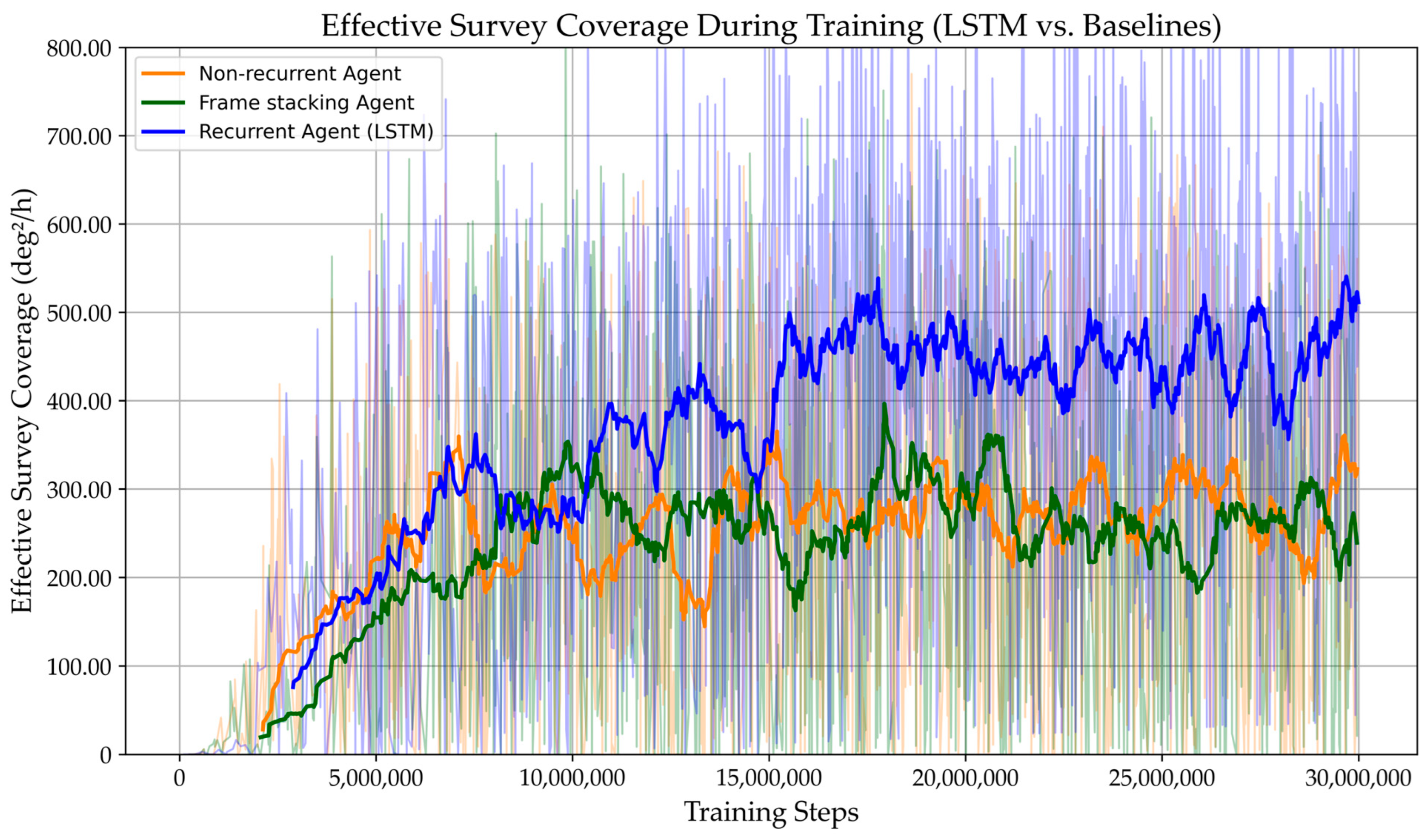

3.2. Impact of Temporal Awareness

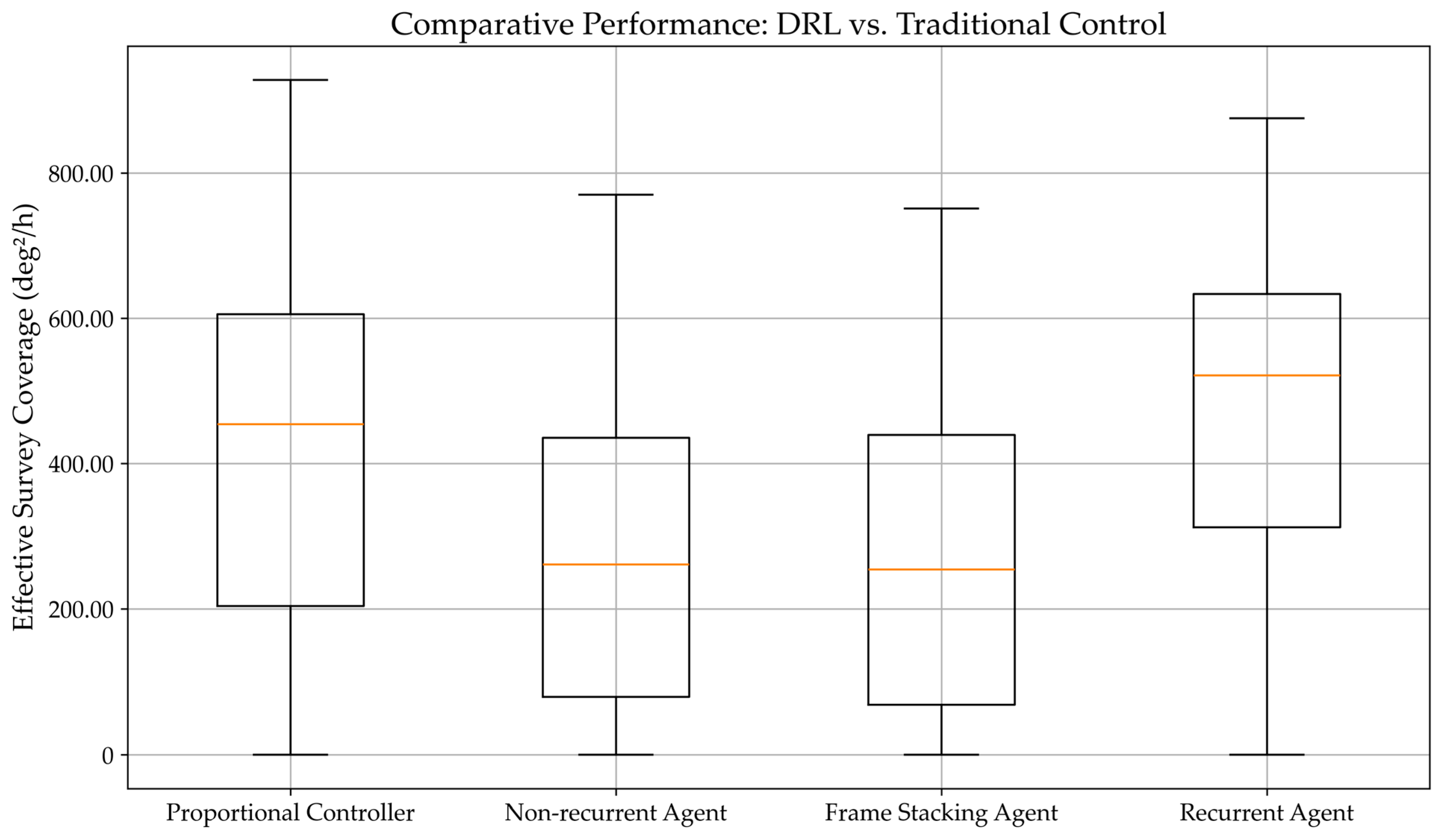

3.3. Sim-to-Real Policy Transfer

4. Discussion

4.1. Feature Extractor Validation and Architectural Impact

4.2. Validation of Recurrent Architecture and Final Implications

4.3. Impact of Temporal Awareness in Sim-to-Real Policy Transfer

4.4. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusions

- The LSTM policy achieved the highest median survey coverage of 521 deg2/h, surpassing the traditionally tuned proportional controller.

- The LSTM demonstrated superior reliability, evidenced by the tightest interquartile range (321 deg2/h) among all agents, confirming its consistent robustness across complex, unpredictable scenarios.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AUT | Auckland University of Technology |

| ADS-B | Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| DRL | Deep Reinforcement Learning |

| IRASR | Institute for Radio Astronomy and Space Research |

| IQR | Interquartile Range |

| KMITL | King Monkut’s Institute of Technology Ladkrabang |

| KL | Kullback–Leibler (Divergence) |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| LEO | Low Earth Orbit |

| MOS-1 | Maritime Observation Satellite-1 |

| MDP | Markov Decision Process |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error |

| MEO | Medium Earth Orbit |

| MSR | Microwave Scanning Radiometer |

| MESSR | Multi-spectral Electronic Self-Scanning Radiometer |

| NASDA | National Space Development Agency of Japan |

| PID | Proportional–Integral–Derivative (Controller) |

| PPO | Proximal Policy Optimization |

| RFI | Radio Frequency Interference |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| RL | Reinforcement Learning |

| RTU | Remote Terminal Unit |

| SGD | Stochastic Gradient Descent |

| TCS | Telescope Control System |

| TRPO | Trust Region Policy Optimization |

| UDP | User Datagram Protocol |

| VTIR | Visible and Thermal Infrared Radiometer |

References

- Bhat, N.; Swainston, N.; McSweeney, S.; Xue, M.; Meyers, B.; Kudale, S.; Dai, S.; Tremblay, S.; Van Straten, W.; Shannon, R.; et al. The Southern-sky MWA Rapid Two-metre (SMART) pulsar survey—I. Survey design and processing pipeline. Publ. Astron. Soc. Aust. 2023, 40, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buchner, J. Dynamic Scheduling and Planning Parallel Observations on Large Radio Telescope Arrays with the Square Kilometre Array in Mind. Master’s Thesis, Auckland University of Technology, Auckland, New Zealand, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Shyalika, C.; Silva, T.; Karunananda, A. Reinforcement Learning in Dynamic Task Scheduling: A Review. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baan, W. RFI mitigation in radio astronomy. In Proceedings of the General Assembly and Scientific Symposium, Groningen, The Netherlands, 29–31 March 2011; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Colome, J.; Colomer, P.; Guàrdia, J.; Ribas, I.; Campreciós, J.; Coiffard, T.; Gesa, L.; Martínez, F.; Rodler, F. Research on schedulers for astronomical observatories. In Proceedings of the SPIE—The International Society for Optical Engineering, Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1–2 July 2012; Volume 8448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.-N.; Chung, A. An Intelligent Design for a PID Controller for Nonlinear Systems. Asian J. Control. 2014, 18, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghahramani, A.; Karbasi, T.; Nasirian, M.; Sedigh, A.K. Predictive Control of a Two Degrees of Freedom XY robot (Satellite Tracking Pedestal) and comparing GPC and GIPC algorithms for Satellite Tracking. In Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Control, Instrumentation and Automation, Shiraz, Iran, 27–29 December 2011; pp. 865–870. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, X.K.; Wang, H.; Tian, Y. Trajectory Tracking Control of XY Table Using Sliding Mode Adaptive Control Based on Fast Double Power Reaching Law. Asian J. Control. 2016, 18, 2263–2271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction, 2nd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; p. xxii. [Google Scholar]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Graves, A.; Antonoglou, I.; Wierstra, D.; Riedmiller, M. Playing Atari with Deep Reinforcement Learning. arXiv 2013, arXiv:1312.5602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.; Steinweg, M.; Kaufmann, E.; Scaramuzza, D. Autonomous Drone Racing with Deep Reinforcement Learning. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Prague, Czech Republic, 27 September–1 October 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Weisz, G.; Budzianowski, P.; Su, P.H.; Gašić, M. Sample Efficient Deep Reinforcement Learning for Dialogue Systems with Large Action Spaces. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2018, 26, 2083–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, J.; Bodin, K.; Lindmark, D.; Servin, M.; Wallin, E. Reinforcement Learning Control of a Forestry Crane Manipulator. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2103.02315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mienye, I.D.; Swart, T.G.; Obaido, G. Recurrent Neural Networks: A Comprehensive Review of Architectures, Variants, and Applications. Information 2024, 15, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García, J.; Fernández, F. A comprehensive survey on safe reinforcement learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2015, 16, 1437–1480. [Google Scholar]

- OpenAI; Akkaya, I.; Andrychowicz, M.; Chociej, M.; Litwin, M.; McGrew, B.; Petron, A.; Paino, A.; Plappert, M.; Powell, G.; et al. Solving Rubik’s Cube with a Robot Hand. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.07113. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, X.; Andrychowicz, M.; Zaremba, W.; Abbeel, P. Sim-to-Real Transfer of Robotic Control with Dynamics Randomization. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaspar, M.; Munoz Osorio, J.D.; Bock, J. Sim2Real Transfer for Reinforcement Learning without Dynamics Randomization. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.11635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Wolski, F.; Dhariwal, P.; Radford, A.; Klimov, O. Proximal Policy Optimization Algorithms. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1707.06347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulman, J.; Levine, S.; Moritz, P.; Jordan, M.; Abbeel, P. Trust Region Policy Optimization. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1502.05477. [Google Scholar]

- Brockman, G.; Cheung, V.; Pettersson, L.; Schneider, J.; Schulman, J.; Tang, J.; Zaremba, W. OpenAI Gym. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.01540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffin, A.; Hill, A.; Gleave, A.; Kanervisto, A.; Ernestus, M.; Dormann, N. Stable-Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2021, 22, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Abadi, M.; Barham, P.; Chen, J.; Chen, Z.; Davis, A.; Dean, J.; Devin, M.; Ghemawat, S.; Irving, G.; Isard, M. TensorFlow: A System for Large-Scale Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the 12th USENIX Symposium on Operating Systems Design and Implementation (OSDI 16), Savannah, GA, USA, 2–4 November 2016; pp. 265–283. [Google Scholar]

- Paszke, A.; Gross, S.; Massa, F.; Lerer, A.; Bradbury, J.; Chanan, G.; Killeen, T.; Lin, Z.; Gimelshein, N.; Antiga, L.; et al. PyTorch: An Imperative Style, High-Performance Deep Learning Library. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1912.01703. [Google Scholar]

- Chollet, F. Keras. GitHub. 2015. Available online: https://github.com/fchollet/keras (accessed on 3 December 2025).

- Astropy, C.; Price-Whelan, A.M.; Lim, P.L.; Earl, N.; Starkman, N.; Bradley, L.; Shupe, D.L.; Patil, A.A.; Corrales, L.; Brasseur, C.E.; et al. The Astropy Project: Sustaining and Growing a Community-oriented Open-source Project and the Latest Major Release (v5.0) of the Core Package. Astrophys. J. 2022, 935, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mnih, V.; Kavukcuoglu, K.; Silver, D.; Rusu, A.; Veness, J.; Bellemare, M.; Graves, A.; Riedmiller, M.; Fidjeland, A.; Ostrovski, G.; et al. Human-level control through deep reinforcement learning. Nature 2015, 518, 529–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Description | Original Spec. | After Conversion |

|---|---|---|

| System | X-Y, Cassegrain reflector, beam waveguide antenna | Unchanged |

| Drive system | Analog electric servomotor | Digital electric servomotor |

| N-S motor | 3.7 kW 1750 rpm 20.2 N·m | 1.5 kW 1500 rpm 8.3 N·m |

| N-S gear ratio | 1:5000 | 1:30,000 |

| E-W drive train | 1.5 kW 1750 rpm 8.2 N·m | 1.5 kW 1500 rpm 8.3 N·m |

| E-W gear ratio | 1:9900 | 1:59,400 |

| Frequency band | S-band and X-band | L-band, S-band and X-band |

| Main reflector diameter | 12 m | Unchanged |

| Subreflector diameter | 1.51 m | Unchanged |

| Primary axis velocity | 2.10 deg/s | 0.30 deg/s |

| Secondary axis velocity | 1.06 deg/s | 0.15 deg/s |

| Primary axis range | ±85 deg (hard limit) | ±80 deg (soft limit) |

| Secondary axis range | ±85 deg (hard limit) | ±80 deg (soft limit) |

| Description | Value Range | Encoded Range |

|---|---|---|

| Remaining simulation steps | [0, ∞), capped at 4096 | [0, 1] |

| X action at t−1 | [−1, 1] | [−1, 1] |

| Y action at t−1 | [−1, 1] | [−1, 1] |

| X action at t−2 | [−1, 1] | [−1, 1] |

| Y action at t−2 | [−1, 1] | [−1, 1] |

| X action at t−3 | [−1, 1] | [−1, 1] |

| Y action at t−3 | [−1, 1] | [−1, 1] |

| Layer | Species | Size of Output | Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Input Layer | 64 × 64 × 3 1 | |

| 1 | Conv2d, ReLU | 64 × 64 × 32 | 3 × 3 |

| 2 | Conv2d, ReLU | 64 × 64 × 64 | 3 × 3 |

| 3 | Maxpool2d | 32 × 32 × 64 | 2 × 2 |

| 4 | Conv2d, ReLU | 32 × 32 × 128 | 3 × 3 |

| 6 | Maxpool2d | 16 × 16 × 128 | 2 × 2 |

| 7 | Conv2d, ReLU | 16 × 16 × 256 | 3 × 3 |

| 8 | Maxpool2d | 8 × 8 × 256 | 3 × 3 |

| 9 | Conv2d, ReLU | 8 × 8 × 256 | 3 × 3 |

| 10 | Maxpool2d | 4 × 4 × 256 | 2 × 2 |

| 11 | Conv2d, ReLU | 1 × 1 × 256 | 4 × 4 |

| 12 | Flatten | 256 |

| Parameters | Range | Type |

|---|---|---|

| Random Load Torque Flag | True, False | Boolean |

| Random Time Flag | True, False | Boolean |

| Random Telescope Angle Flag | True, False | Boolean |

| Random Load Torque Magnitude | [−0.2, 0.2] | Float |

| Number of Target Clusters | 1–4 | Integer |

| Target Dwell Time (s) | 1–60 | Integer |

| Number of Interference Sources | 0–4 | Integer |

| Time | Unix Timestamp | Integer |

| Telescope X Angles (deg) | [−80, 80] | Float |

| Telescope Y Angles (deg) | [−80, 80] | Float |

| Parameters | Value |

|---|---|

| Optimizer | Adam |

| Learning Rate | 5 × 10−5 |

| Annealing Learning Rate | False |

| Discount Factor | 0.99 |

| GAE | True |

| GAE Lambda | 0.95 |

| PPO Clip Ratio | 0.2 |

| Target KL | None |

| Clip Value Loss | True |

| Value Loss Coefficient | 0.5 |

| Max Gradient Normalization | 0.5 |

| Rollout Buffer | 32,768 |

| Minibatch Size | 2048 |

| Environment Count | 16 |

| Exploration Noise | 0.2 |

| Name | Condition | Reward |

|---|---|---|

| Sky clearance | No targets over the horizon. Successfully observed any target. | 0.0025 per remaining steps. Capped at 10. |

| Target clearance | Uninterruptedly maintaining a target inside boresight during the dwell time. | 1 |

| Target approach | Angular distance to the closest unobstructed target. | 0.010 per mrad (closer) 0.011 per mrad (further) |

| Feature Extractor | Pre-Training | Training Steps to Convergence | Mean Survey Coverage (deg2/h) |

|---|---|---|---|

| NatureCNN | No | No | - |

| CustomCNN | No | No | - |

| NatureCNN | Yes | 6 million | 234 |

| CustomCNN | Yes | 7 million | 275 |

| Agent Architecture | Training Steps to Convergence | Mean Survey Coverage (deg2/h) | Relative Improvement (vs. Non-Recurrent) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-recurrent | 7 million | 275 | N/A |

| Frame Stacking | 10 million | 270 | −2.1% |

| Recurrent | 18 million | 475 | 72.7% |

| Metric | Proportional Controller | Non-Recurrent Agent | Frame Stacking Agent | Recurrent Agent (LSTM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q1 | 204 | 80 | 69 | 312 |

| Q2 | 454 | 261 | 254 | 521 |

| Q3 | 606 | 435 | 439 | 633 |

| IQR | 402 | 355 | 370 | 321 |

| Min | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Max | 928 | 770 | 751 | 876 |

| Metric | Proportional Controller | Non-Recurrent Agent | Frame Stacking Agent | Recurrent Agent (LSTM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deg2/h | Change | Deg2/h | Change | Deg2/h | Change | Deg2/h | Change | |

| Q1 | 167 | −18.1% | 80 | 0% | 80 | +15.9% | 301 | −3.5% |

| Q2 | 391 | −13.9% | 229 | −12.3% | 262 | +3.1% | 516 | −1.0% |

| Q3 | 587 | −3.1% | 392 | −9.7% | 424 | −3.4% | 631 | −0.3% |

| IQR | 420 | +4.5% | 312 | −11.8% | 344 | −7.0% | 330 | +2.8% |

| Min | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Max | 866 | −6.7% | 727 | −5.6% | 774 | +3.1% | 880 | +0.5% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Puangragsa, S.; Sahavisit, T.; Laon, P.; Puangragsa, U.; Phasukkit, P. Implementation of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Radio Telescope Control and Scheduling. Galaxies 2025, 13, 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060137

Puangragsa S, Sahavisit T, Laon P, Puangragsa U, Phasukkit P. Implementation of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Radio Telescope Control and Scheduling. Galaxies. 2025; 13(6):137. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060137

Chicago/Turabian StylePuangragsa, Sarut, Tanawit Sahavisit, Popphon Laon, Utumporn Puangragsa, and Pattarapong Phasukkit. 2025. "Implementation of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Radio Telescope Control and Scheduling" Galaxies 13, no. 6: 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060137

APA StylePuangragsa, S., Sahavisit, T., Laon, P., Puangragsa, U., & Phasukkit, P. (2025). Implementation of Deep Reinforcement Learning for Radio Telescope Control and Scheduling. Galaxies, 13(6), 137. https://doi.org/10.3390/galaxies13060137