Integrating GIS and Official Statistics Using GISINTEGRATION

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Challenge of GIS Data Integration

3. Overview of the GISINTEGRATION Package

3.1. Package Structure

3.1.1. Preliminary Definition

3.1.2. Modularity and Adaptability

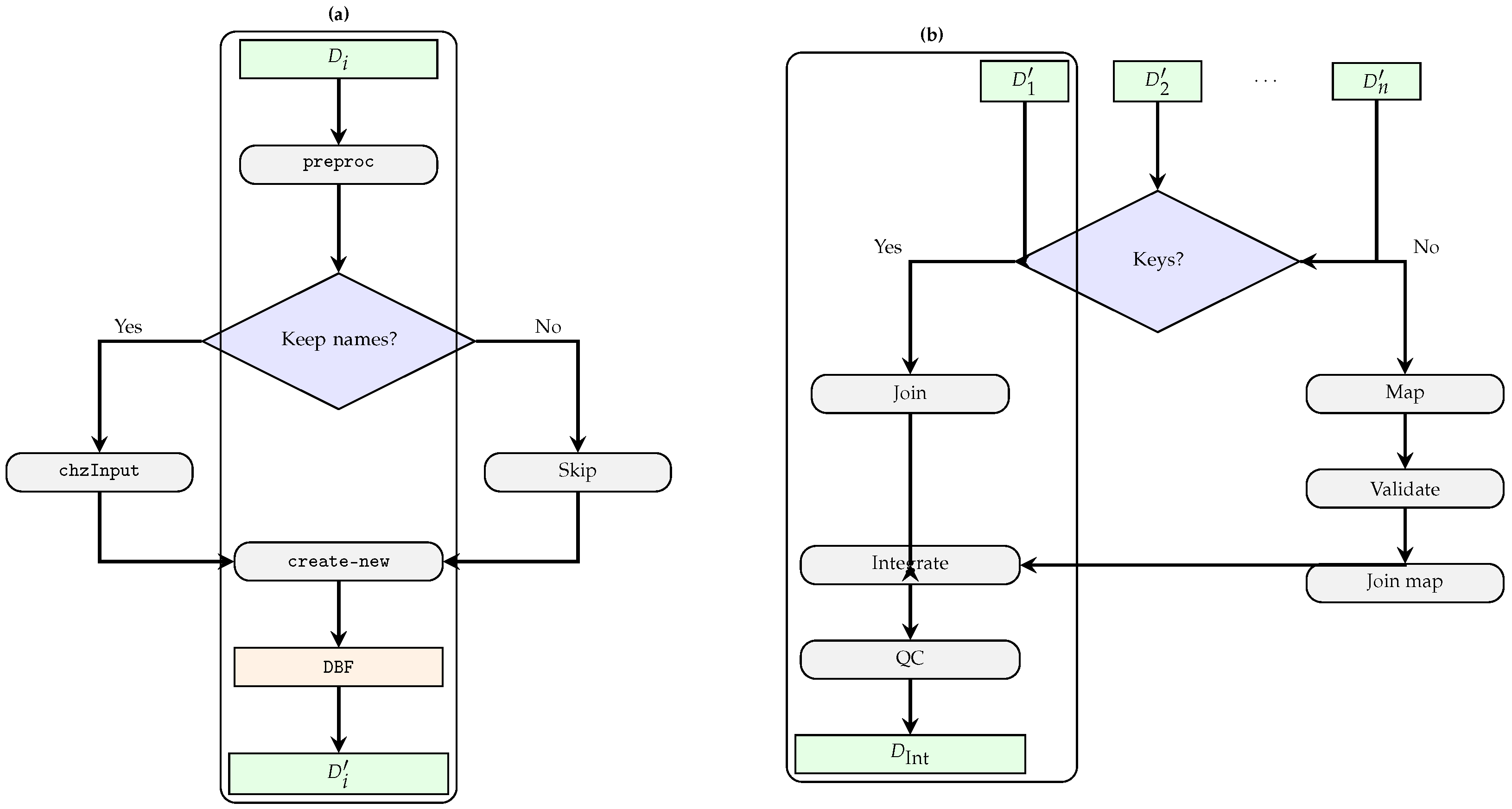

- Data Preprocessing: The preproc function standardizes variable names across datasets, ensuring consistency and reducing manual intervention. By addressing naming inconsistencies and discrepancies in data formats, preproc minimizes errors and prepares datasets for seamless integration. This step is crucial for ensuring compatibility across diverse GIS and non-GIS datasets, especially in large-scale projects.

- User Consultation: The chzInput function allows users to specify variables that should retain their original names, providing flexibility in preprocessing. This feature empowers users to maintain domain-specific naming conventions where necessary, ensuring that critical variables retain their interpretability and relevance to stakeholders.

- Final Data Preparation: The create-new-data function performs comprehensive preprocessing, including variable name harmonization, format adjustments, and the elimination of redundant or irrelevant data. This function outputs two refined data frames optimized for analysis, streamlining downstream workflows and reducing the need for additional cleaning steps.

- DBF File Generation: The preprocLinkageDBF function automates data cleaning, normalization, and format transformations, making it possible to generate DBF files compatible with popular GIS software such as ArcGIS and QGIS. This capability ensures that datasets are ready for spatial visualization and advanced geospatial analyses, bridging the gap between data preprocessing and practical application.

- Common Variable Identification: The selVar function identifies shared variables between datasets, facilitating the selection of blocking variables for linkage procedures. This step is essential for merging datasets from multiple sources, enabling robust data integration for tasks such as spatial modeling, demographic analysis, and environmental monitoring. Additionally, it aids in detecting potential inconsistencies or overlaps, enhancing data reliability.

- Interactive User Experience: GISINTEGRATION includes an interactive interface that guides users through preprocessing steps. This feature reduces the learning curve for new users while allowing advanced users to customize the pipeline according to their needs, fostering a balance between simplicity and flexibility.

3.1.3. Efficiency and Compatibility

3.2. Workflow Description

- 1.

- Preprocessing GIS Datasets.Call to standardize variable names. This step normalizes naming conventions across :It resolves inconsistencies like mixed-case variable names or invalid characters.

- 2.

- User-Specific Customization.If the user wants to retain certain domain-specific variable names, apply:where varsToKeep is a subset of variable names that must remain unchanged.

- 3.

- Final Data Preparation.Consolidate all preprocessing steps into a final refined version:This harmonizes variable formats (e.g., date, numeric) and removes redundant attributes, yielding a dataset ready for analysis.

- 4.

- DBF File Preparation.To facilitate geospatial visualization in software like ArcGIS or QGIS, generate DBF outputs:This ensures direct compatibility with common GIS platforms.

- 5.

- Identifying Common Variables.Finally, detect shared variables for linkage or merging:This step is crucial for joining datasets and verifying consistency across multiple sources.

3.3. Advanced Features in the Workflow

- Batch Processing:This allows a user to process an entire collection in one session, reducing manual work.

- Interactive Debugging: Any errors or warnings during provide detailed logs, indicating which function in triggered the issue and offering suggestions for resolution.

- Integration with R Markdown: Users can embed calls inside literate programming documents, ensuring reproducibility and simplified reporting.

- Custom Output Formats: In addition to DBF, the pipeline supportsenabling flexible dissemination of cleaned datasets. The GISINTEGRATION workflow ensures consistent, efficient, and reliable data integration across diverse GIS and non-GIS sources.

3.4. Positioning and Benchmarks

3.5. Scope and Future Development

- Raster and remote-sensing integration: automated workflows for linking gridded data (e.g., population density, air quality, NDVI) with administrative boundaries using zonal statistics and spatial resampling.

- Temporal harmonization: support for dynamic datasets with explicit time attributes, enabling longitudinal comparisons and versioned boundary handling.

- Topological and scale reconciliation: integration of functions for detecting and resolving boundary overlaps, gaps, and mismatched resolutions.

- Conflation tools: semi-automated matching of spatial features across differing data sources to support map alignment and geocoding validation.

4. Application to Official Statistics

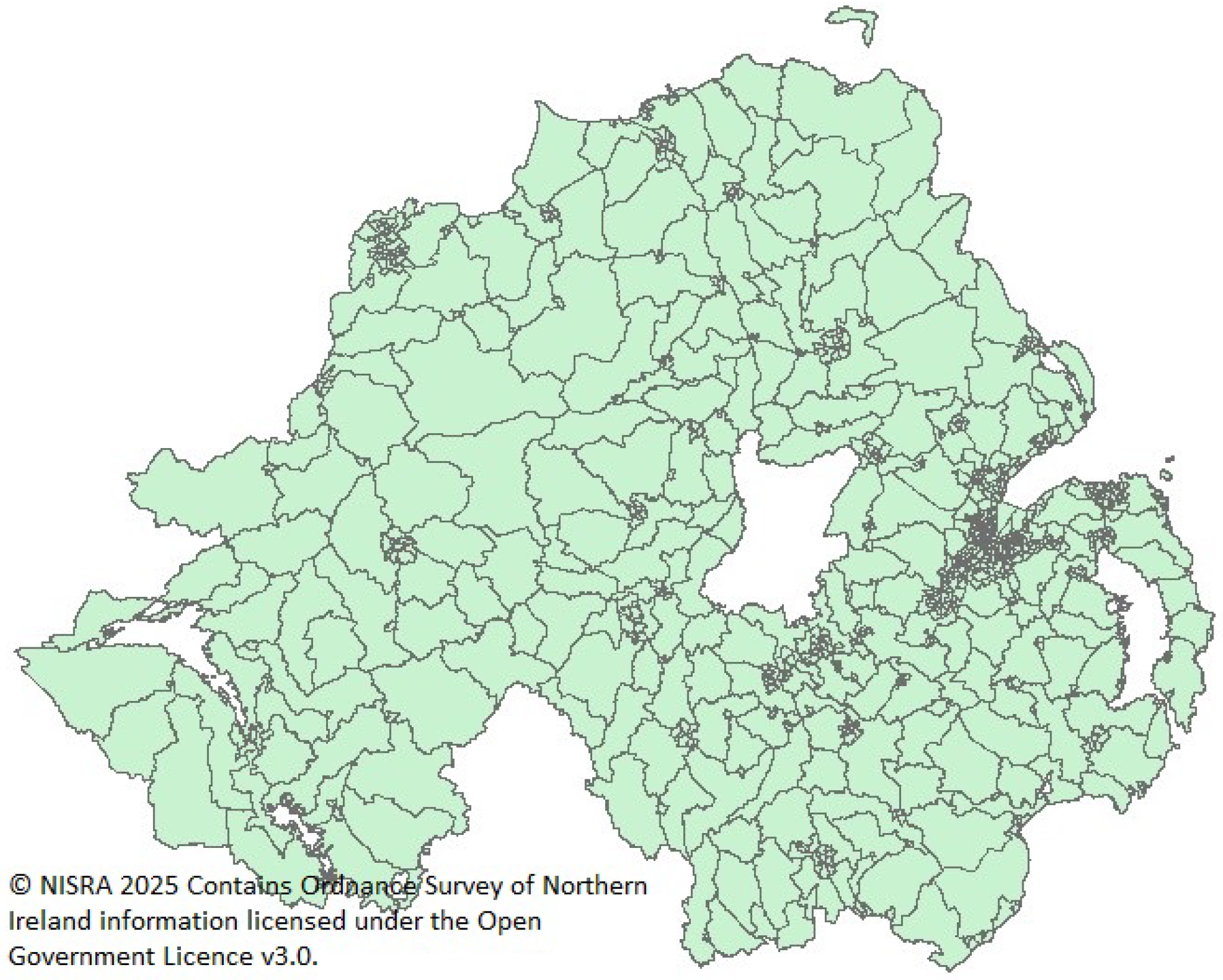

4.1. Population Census Data

4.1.1. Dataset Description

- Super Data Zones (SDZ2021) [27]:a manageable dataset primarily used to test the GISINTEGRATION functionalities and refine workflow parameters.

- Census 2021 Population Density Data (census-2021-ms-a14) [28]:This dataset reflects the original structure provided by NISRA, including certain metadata sheets.

4.1.2. Integration Results and Visualization in GISINTEGRATION

- Efficiency Gains

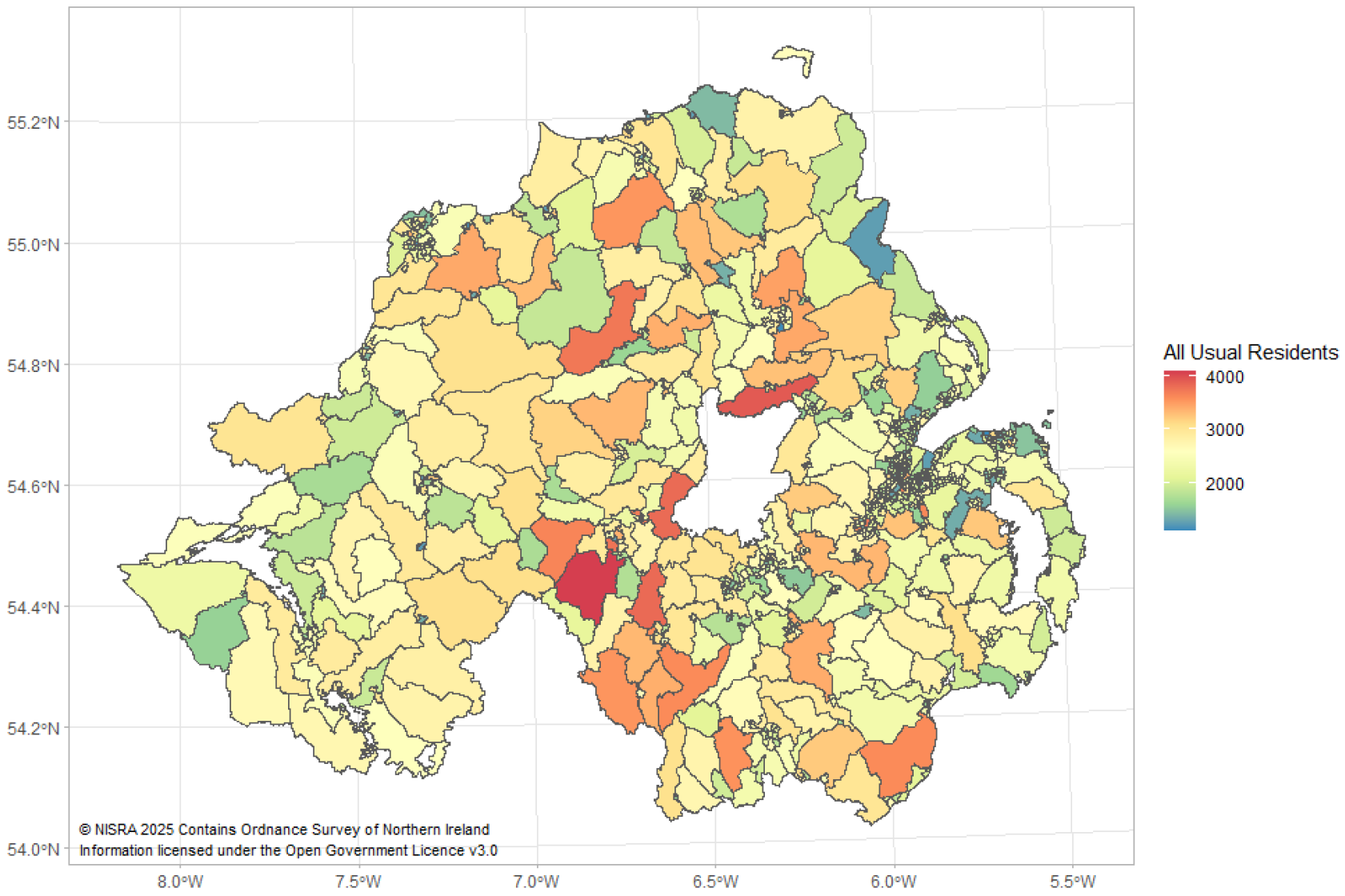

4.1.3. Population Density

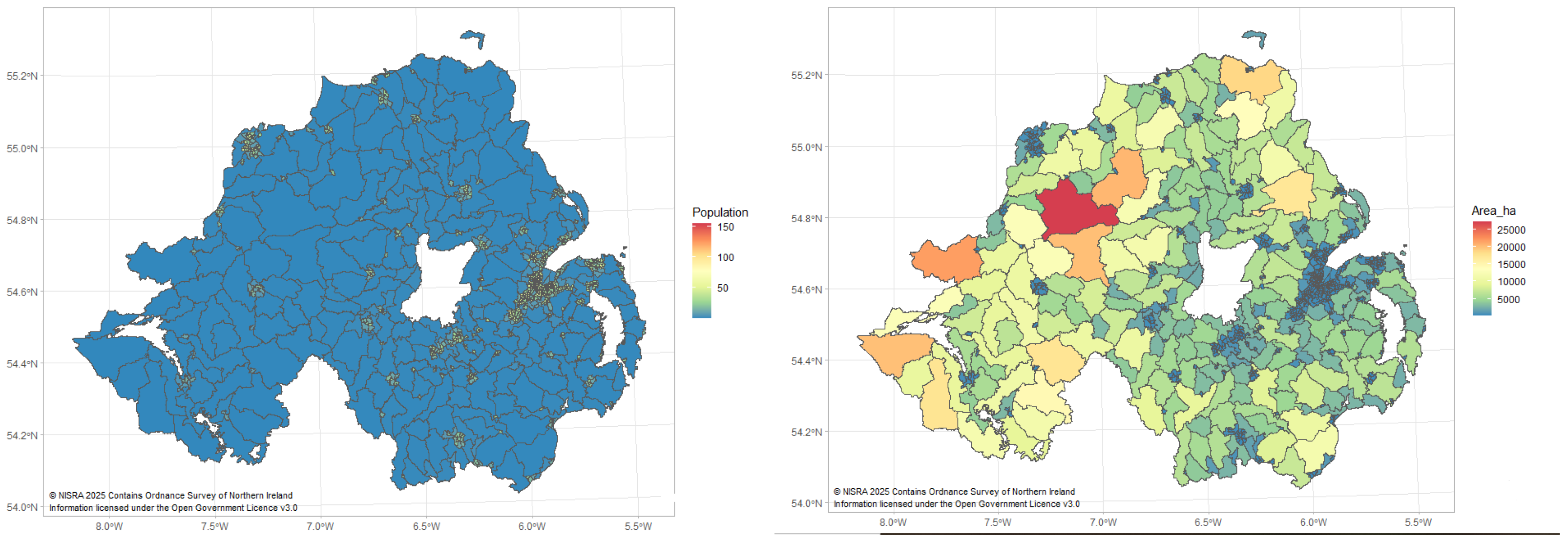

4.1.4. Multiple-Attribute Visualization

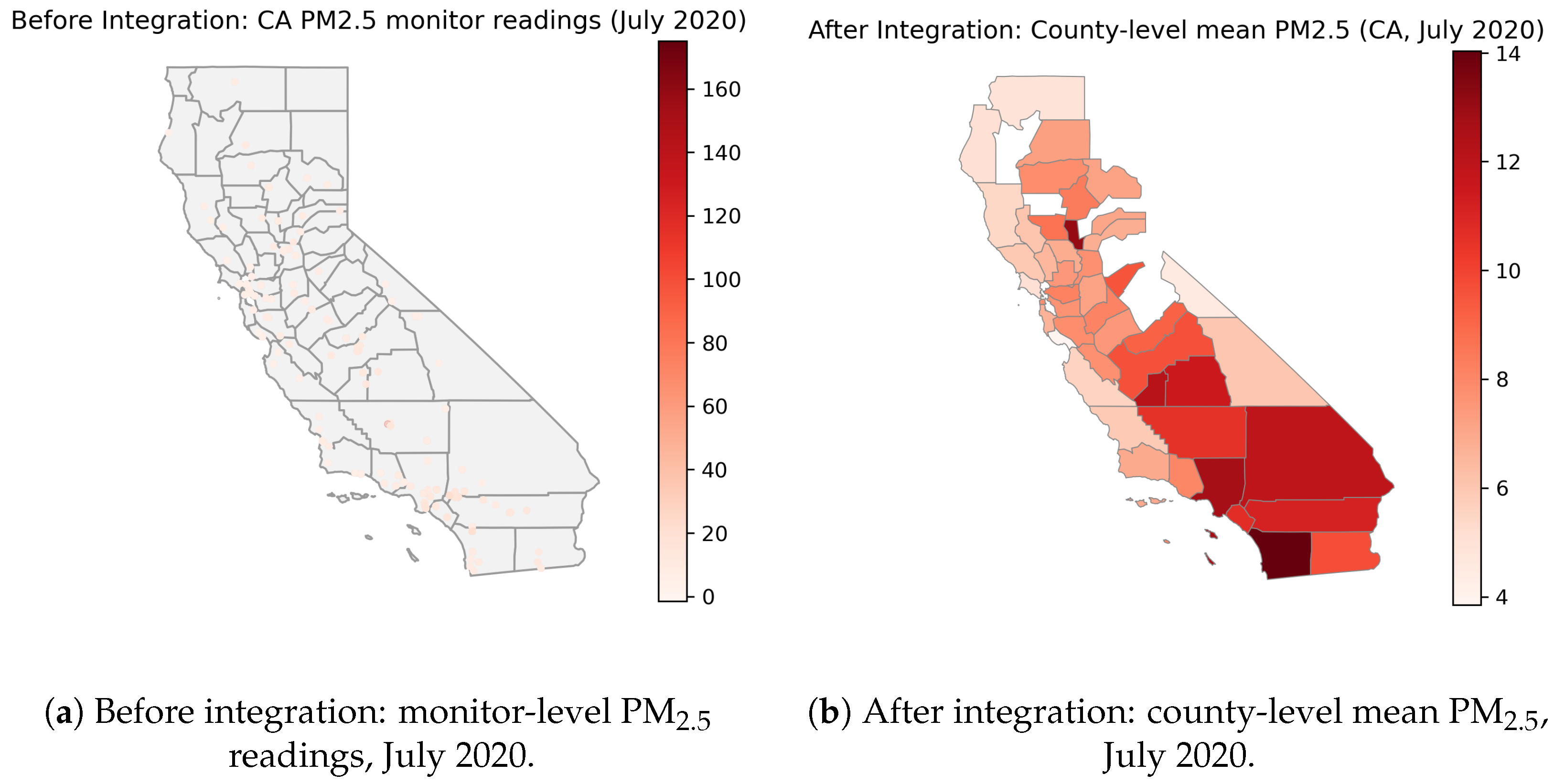

4.2. Application: Integration of Air Quality Data with Administrative Boundaries

- PM2.5: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) AirData, Air Quality System (AQS) Daily Summary files for parameter 88101 (PM2.5, FRM/FEM mass), year 2020.

- County boundaries: U.S. county polygons (FIPS-coded GeoJSON) distributed via Plotly Datasets, derived from the U.S. Census Bureau’s TIGER/Line shapefiles.

4.2.1. Visualization and Outputs

- The spatial aggregation clarifies geographic variation in PM2.5 exposure, with higher values observed in several counties in southern and central California. This transformation enhances interpretability and supports equitable air-quality policy design.

- Coverage: Number and percentage of counties with at least one valid spatial assignment.

- Variance reduction: Comparison of variance at the monitor level versus the county-level aggregated means, as an indicator of noise reduction and signal stability.

- Descriptive statistics: Mean and median PM2.5 concentrations across all counties with sufficient coverage.

4.2.2. Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Lessons from Population Census Integration

- Rapid alignment with evolving geographies. NSOs frequently revise output geographies (e.g., DZ2021 and SDZ2021). By automating variable harmonization and schema reconciliation, GISINTEGRATION shortens the lag between geographic releases and the availability of analysis-ready statistical layers.

- Traceability and reproducibility. Renaming, selection, and export steps are logged and repeatable, which is critical when disseminating official statistics and updating products as methods or source tables evolve.

- Flexible attribute linkage. The workflow makes it straightforward to attach multiple attributes (e.g., all usual residents, population density, area) to the same spatial units, enabling multi-attribute visualization and downstream modeling.

- Interoperable outputs. Standards-compliant DBF/CSV/GeoJSON exports allow immediate use in common GIS tools (ArcGIS/QGIS) and web mapping stacks, facilitating internal analysis and public communication.

- Geographic change management. Newly defined zones require robust crosswalks to legacy geographies for time series comparability. Maintaining concordances and versioned metadata is as important as the one-off linkage.

- Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP). Indicators such as density or rates depend on zoning systems and scale. Although the package standardizes processing, analysts must still interpret results in light of MAUP and consider sensitivity analyses across geographies (e.g., SDZ vs. DZ).

- Key discovery and semantic alignment. Even within one statistical system, code lists, field names, and formats can vary across tables and vintages. Automated key/variable discovery (selVar) reduces brittle, hand-coded joins and avoids silent mismatches.

5.2. Lessons from Air-Quality Integration

- Policy alignment through spatial aggregation. Aggregating monitor readings to counties produces indicators aligned with decision-making units, improving interpretability for health and regulatory uses.

- Stability gains. Variance reduction from monitor-level values to county means indicates improved signal stability, aiding communication and comparisons across jurisdictions.

- Coverage diagnostics. Retaining counts of contributing observations provides an explicit measure of data sufficiency and helps flag counties that may require alternative estimation strategies.

- Uneven monitoring networks. Spatial clustering of monitors may bias county means. Where coverage is sparse or absent, model-based fusion (e.g., satellite products, reanalysis) or small-area estimation can complement direct aggregation.

- Exposure representativeness. Simple arithmetic means do not capture diurnal patterns, episodic events, or population-weighted exposure; additional weighting or temporal smoothing may be warranted depending on the question.

5.3. Cross-Cutting Themes

- Standardization before sophistication. Routine—but error-prone—steps (naming, typing, key discovery, export constraints) are the bottleneck. Automating these with auditable logs unlocks analyst time for interpretation and advanced methods.

- Governance-grade metadata. Reliable integration depends on versioned geographies, documented concordances, and explicit CRS handling. Embedding these artifacts in the pipeline improves institutional memory and reproducibility.

- Interoperability as a design goal. Outputs that “just work” in mainstream GIS and analysis environments reduce friction for both specialists and non-specialists, speeding dissemination.

5.4. Limitations and Sensitivities

- Data quality and representativeness. Integration cannot compensate for missingness, measurement error, or siting bias. Diagnostics (coverage, variance, outlier checks) should accompany any aggregated indicators.

- Geographic dependence of results. MAUP and boundary updates can shift indicator values; where feasible, provide multi-scale views or stability checks across alternative zonations.

- Scope of current implementation. The present focus is vector/tabular data. Raster integration, temporal versioning of boundaries, and conflation/topological correction are flagged for future development.

5.5. Implications for Producers and Users

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Agrawal, S.; Gupta, R.D. Web GIS and its architecture: A review. Arab. J. Geosci. 2017, 10, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhurandhar, P.; Tamrakar, A.; Patra, J.P. Review on GIS-based online information system for rural development in Chhattisgarh. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 8226–8231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhu, D.; Ye, S.; Yao, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, N.; Han, Y.; Zhang, L. Design and implementation of geographic information systems, remote sensing, and global positioning system–based information platform for locust control. J. Appl. Remote Sens. 2014, 8, 084899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UN-GGIM. Future Trends in Geospatial Information Management: The Five to Ten Year Vision, 3rd ed.; Report by the United Nations Committee of Experts on Global Geospatial Information Management; UN-GGIM: New York, NY, USA, 2020; Available online: https://ggim.un.org/meetings/GGIM-committee/10th-Session/documents/Future_Trends_Report_THIRD_EDITION_digital_accessible.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Vinueza-Martinez, J.; Correa-Peralta, M.; Ramirez-Anormaliza, R.; Franco Arias, O.; Vera Paredes, D. Geographic Information Systems (GISs) Based on WebGIS Architecture: Bibliometric Analysis of the Current Status and Research Trends. Sustainability 2024, 16, 6439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodchild, M.F. Geographical information science. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1992, 6, 31–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longley, P.A.; Goodchild, M.F.; Maguire, D.J.; Rhind, D.W. Geographic Information Science and Systems; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://storymaps.arcgis.com/collections/470ca804de874925aadb4db9e9eca293 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Available online: https://unstats.un.org/unsd/ccsa/isi/2019/introduction.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Available online: https://www.un.org/geospatial/ (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Available online: https://unece.org/DAM/stats/publications/2016/Issue1_Geospatial.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Gong, H.; Simwanda, M.; Murayama, Y. An Internet-Based GIS Platform Providing Data for Visualization and Spatial Analysis of Urbanization in Major Asian and African Cities. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, C.; Zhu, Y.; Fu, J.; Dong, M. A lightweight collaborative GIS data editing approach to support urban planning. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNECE Working Paper on Statistics, Issue 10. Issues and Obstacles to the Greater Integration of Statistical and Geospatial Information Across the UNECE Region. Available online: https://unece.org/sites/default/files/2024-08/INGEST%20issues%20and%20obstacles%20WP_combined.pdf (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Available online: https://statswiki.unece.org/spaces/GeoStat/blog/2024/02/14/437420257/Unlocking+the+Power+of+Geospatial+Data+with+GIS+Data+Integration+A+New+R+Package (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Adouane, K.; Stouffs, R.; Janssen, P.; Domer, B. A model-based approach to convert a building BIM-IFC data set model into CityGML. J. Spat. Sci. 2020, 65, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amirebrahimi, S.; Rajabifard, A.; Mendis, P.; Ngo, T. A BIM-GIS integration method in support of the assessment and 3D visualisation of flood damage to a building. J. Spat. Sci. 2016, 61, 317–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arroyo Ohori, K.; DiakitA, A.; Krijnen, T.; Ledoux, H.; Stoter, J. Processing BIM and GIS models in practice: Experiences and recommendations from a GeoBIM project in the Netherlands. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, F.; Abualdenien, J.; Borrmann, A. An evaluation of the strict meaning of owl:sameAs in the field of BIM GIS Integration. CEUR Workshop Proc. 2021, 3081, 154–165. [Google Scholar]

- Hassani, H.; Marvian Mashhad, L.; Stewart, S.; Macfeely, S. GISINTEGRATION: An R Package for GIS Data Preprocessing and Integration. CRAN. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/GISINTEGRATION/index.html (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Annoni, A.; Smits, P.C. Main problems in building European environmental spatial data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2003, 24, 3887–3902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villa, P.; Molina, R.; Gomarasca, M.A. Data Harmonisation in the Context of the European Spatial Data Infrastructure: The HUMBOLDT Project Framework and Scenarios. In Earth Observation of Global Changes (EOGC); Springer: Berline/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Bordogna, G.; Kliment, T.; Frigerio, L.; Brivio, P.A.; Crema, A.; Stroppiana, D.; Boschetti, M.; Sterlacchini, S. A Spatial Data Infrastructure Integrating Multisource Heterogeneous Geospatial Data and Time Series: A Study Case in Agriculture. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2016, 5, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evelpidou, N.; Cartalis, C.; Karkani, A.; Saitis, G.; Philippopoulos, K.; Spyrou, E. A GIS-Based Assessment of Flood Hazard through Track Records over the 1886–2022 Period in Greece. Climate 2023, 11, 226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, M.; Hou, W.; Gao, F.; Xu, B.; Zeng, J.; Jia, D.; Li, J. Spatial Distribution and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Settlements in the Shiyang River Basin, Western China. Sustainability 2023, 15, 12126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajami, A.; Kuffer, M.; Persello, C.; Pfeffer, K. Identifying a Slums’ Degree of Deprivation from VHR Images Using Convolutional Neural Networks. Remote Sens. 2019, 11, 1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Super Data Zone. Available online: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/support/geography/super-data-zones-census-2021 (accessed on 10 November 2025).

- Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency. Available online: https://www.nisra.gov.uk/publications/census-2021-person-and-household-estimates-for-data-zones-in-northern-ireland (accessed on 10 November 2025).

| Task | sf/terra (LOC) | GISINTEGRATION (LOC) | Added Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variable harmonization (15 files) | 90–140 | 6–10 | Automated renaming, audit log |

| Key discovery and crosswalk build | Custom joins | 1–2 | Concordance generation |

| Spatial join and DBF-safe export | 20–40 | 2–3 | Standards-compliant fields |

| QA summary (coverage, variance) | Manual | Auto | Built-in quality metrics |

| Batch pipeline (multi-dataset) | Ad hoc loops | 1 | Reproducible processing |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hassani, H.; Marvian Mashhad, L.; Stewart, S.; MacFeely, S. Integrating GIS and Official Statistics Using GISINTEGRATION. AppliedMath 2025, 5, 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040166

Hassani H, Marvian Mashhad L, Stewart S, MacFeely S. Integrating GIS and Official Statistics Using GISINTEGRATION. AppliedMath. 2025; 5(4):166. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040166

Chicago/Turabian StyleHassani, Hossein, Leila Marvian Mashhad, Sara Stewart, and Steve MacFeely. 2025. "Integrating GIS and Official Statistics Using GISINTEGRATION" AppliedMath 5, no. 4: 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040166

APA StyleHassani, H., Marvian Mashhad, L., Stewart, S., & MacFeely, S. (2025). Integrating GIS and Official Statistics Using GISINTEGRATION. AppliedMath, 5(4), 166. https://doi.org/10.3390/appliedmath5040166