1. Introduction

Optimal control theory addresses the challenge of designing control functions for dynamical systems, governed by differential equations, to optimize specific performance criteria. These problems are inherently more complex than conventional static optimization, as decision variables represent time-dependent trajectories rather than scalar values [

1]. In real-world engineering applications, system performance must often balance multiple competing objectives, giving rise to multi-objective optimal control problems (MOOCPs), where solutions are characterized by Pareto-optimal sets representing trade-offs between conflicting goals [

2].

Scalarization methods represent a classical approach for handling MOOCPs by transforming them into parameterized single-objective subproblems. Techniques such as Weighted Sum (WS), Normal Boundary Intersection (NBI), and Normalized Normal Constraint (NNC) have been widely applied in this context [

3,

4]. However, these methods face significant limitations: the WS method cannot generate solutions in non-convex regions of the Pareto front [

5,

6], while NBI and NNC, though capable of handling non-convex Pareto fronts, require numerous independent optimization problems to be solved, leading to substantial computational burdens [

7]. Recent advancements incorporating Centroidal Voronoi Tessellation (CVT) algorithms have improved solution distribution uniformity but remain computationally intensive, particularly for high-dimensional problems and interior points of the Pareto front [

8].

Evolutionary algorithms (EAs), particularly Multi-Objective Evolutionary Algorithms like NSGA-II and genetic algorithms (GAs), offer population-based solutions for MOOCPs [

9]. While demonstrating global search capabilities, EAs face challenges including susceptibility to local optima, sensitivity to operator selection, and computational inefficiency [

10,

11]. The performance of standard GA is particularly constrained by its dependence on problem-specific operator tuning and limited convergence speed [

10]. To address these limitations, researchers have developed sophisticated hybrid approaches including (1) multi-operator evolutionary algorithms combining different selection, crossover, and mutation strategies [

12,

13] and (2) integration with other metaheuristics including particle swarm optimization [

14,

15], descent methods [

16], simulated annealing [

17], and cuckoo search algorithms [

18]. These hybridizations have demonstrated improved convergence properties and solution quality across various optimal control applications.

Set-oriented algorithms, such as the simple cell mapping (SCM) method, provide a global framework for analyzing and solving multi-objective optimal control problems. In SCM, the state space is discretized into a uniform grid of cells [

19]. The system’s dynamics are then analyzed by mapping each cell to one or more image cells [

20], enabling a comprehensive exploration of the entire domain, including the identification of global attractors and their basins [

21,

22]. A key advantage of set-oriented methods is their ability to naturally approximate the entire Pareto frontier, including non-convex and disconnected segments, in an integrated process. While the computational burden of the basic SCM method increases significantly with the dimensionality of the design space [

23], its efficiency can be greatly enhanced by focusing the cell mapping search only on promising regions, such as the neighborhoods of solutions provided by a preliminary evolutionary search [

24]. Compared to more complex cell mapping (CM) techniques, SCM is often preferred for deterministic optimization due to its computational simplicity and directness. Other set-oriented methods, like subdivision techniques, share this global perspective but may also face challenges with excessive computational load in complex, high-dimensional problems [

25].

In this study, because of the weaknesses mentioned above, we have tried to present an effective numerical approach for finding solutions to multi-objective nonlinear optimal control problems by presenting a hybrid method (genetic algorithm and cell mapping). The proposed hybrid method uses NSGA-II for efficient global exploration to identify promising regions near the Pareto set and then uses SCM for precise local refinement within those regions. This approach not only dramatically reduces the computational burden associated with a pure SCM search over the entire design space but also significantly improves the accuracy and uniformity of the Pareto frontier approximation compared to a pure NSGA-II and SCM. To validate the proposed algorithm’s performance, it was tested on a suite of four problems: two standard benchmarks and two real-world multi-objective optimal control problems. Its performance was quantitatively assessed based on the convergence to the true Pareto-optimal set and the diversity of the obtained solution set.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. In

Section 2, mathematical formulations of MOCP are briefly introduced. The hybrid method is described in

Section 3. Finally, in

Section 4, two benchmark MOPs and two practical MOCPs are presented to demonstrate the efficiency of the proposed algorithm.

2. Multi-Objective Optimal Control Problem

The multi-objective optimal control problem is generally formulated as follows:

where

m is the number of objectives and

n is the state space dimension. Also,

and

show the state and control variables, respectively. The objective

is defined as follows:

The functions

and

are continuous and

J is the cost function to be minimized. The final time

may be known or variable. The function

represents the dynamic system equations, and also the vectors

b and

indicate the initial and terminal boundary conditions, and path and final inequality constraints on the states and controls are given by the vectors

and

, respectively. The set of all admissible pairs

that are satisfied in Equations (2)–(6) is defined as

[

26].

In multi-objective problems, due to the existence of multiple objectives (usually in conflict with each other), it is difficult to find an acceptable solution that optimizes all objectives simultaneously [

27]. Therefore, it is necessary to explain the concept of Pareto optimality [

28], which is defined as follows.

Definition 1. A solution is said to not dominate whenever there is no solution like so that it is no worse than in all objectives and is strictly better in at least one objective [2]. Definition 2. A solution is a Pareto optimal solution of the MOCP if and only if it is not dominated by another solution like [2]. Definition 3. A set of non-dominated solutions is said to be a Pareto set, and we call their image in the objective space the Pareto frontier [2]. Definition 4. Let u and be two vectors and A and be two sets of the vectors. The maximum norm distance and the semi-distance are defined as

- 1.

- 2.

- 3.

3. Non-Dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm II (NSGA-II)

Genetic algorithm (GA) is a meta-heuristic algorithm inspired by the laws of genetics and natural selection. This algorithm starts by creating a random population of candidate solutions in the design space, and then the fitness of the population is checked. From among the candidate solutions, the best ones are selected to produce the next generation and the combination, and the mutation operation is performed on them. In subsequent iterations, by performing this process, the candidate solutions gradually converge to the true solution [

29].

The GA for MOPs has many variations, and the differences in these variations mainly lie in the fitness assignment, elitism, and diversification methods. Non-dominated sorting genetic algorithm II (NSGA-II) [

29] is one of these variations and is one of the most effective multi-objective GAs. NSGA-II is a modified version of NSGA that was first introduced by Srinivas and Deb [

30]. The difference between these two versions is that the NSGA-II algorithm uses fast non-dominated sorting, elitism, and population distance techniques. The elitism technique ensures that the best solutions from the previous step are retained in the current step. This process clearly increases the convergence speed of the algorithm.

First, the parent population is randomly generated as a candidate solution. Then, by performing operation tournament selection, crossover, and mutation on the parents, a population of offspring is generated. Both populations are sorted using non-dominated sorting. In addition, another strategy, the crowding distance, is also used. This measure shows how close a solution is to its neighbors, so that the greater the distance, the better the Pareto front diversity. This operation continues until one of the stopping conditions of the algorithm is met. For more details, the interested reader is referred to Deb et al. (2002) [

29].

EAs behave better than other methods for specific problem classes but may perform worse for other problem classes. Given that evolutionary algorithms are inherently stochastic, they can approximate the Pareto set well for most problems. These algorithms also have some weaknesses, such as the fact that they only consider a subset of solutions that are close to the optimal solutions. In addition, a significant portion of the solution set is ignored by the archiving technique [

31]. Additionally, EAs can get stuck in local optima when using local search alone. However, hybridizing EAs with other search and optimization techniques can overcome this limitation and provide optimized solutions.

4. Simple Cell Mapping (SCM)

Cell mapping techniques were first introduced in [

19] for the global analysis of nonlinear dynamical systems. In SCM, the cell state space is an n-dimensional grid of cells of the same size. The basic idea of the SCM method is that each cell has a single image, which is usually determined using the Center Point Method, where a single trajectory from the center of the cell domain is examined. In other words, all states within a cell are mapped to a single cell.

To discretize the performance index

, a finite set of mapping time intervals and admissible control inputs can be considered. We denote the set of mapping time steps and the set of admissible control vectors by

with a step size

and

, respectively. Using Equation (

7), we can obtain the point-to-point mapping.

where

F is described as a point-to-point mapping and the state vector and control in the k-th mapping step are represented by the

and

, respectively. Here, the dynamics of the whole cell are shown by

z. Using the point-to-point mapping of Equation (

8), the center of

z is imaged. The cell containing this image is considered the image of cell

z. This cell is then called the image cell of

z [

19]:

Because the exact image of the center of the

z is approximated by the center of its image cell, this operation causes a significant error in the long term of the solution of dynamical systems [

19,

32]. However, the SCM method provides an effective procedure for examining the properties of the global solution of the system. For more studies, the reader is referred to Hsu [

19].

5. The Hybrid Method

The SCM method first discretizes the design space and then creates cell-to-cell mappings for the MOP search algorithm [

19]. The SCM method examines the entire search space to find the solution of MOP. Because the Pareto set only covers a small part of the design space, the computational burden and performance of the method will be significantly improved if we apply the SCM method around the Pareto set.

On the other hand, the NSGA-II algorithm is an evolutionary algorithm with random search [

9]. The process starts with an initial population as candidate solutions and by evaluating their fitness, the best solutions are selected from them to produce the next generation. This process continues its evolutionary path until the stopping condition of the algorithm is met.

In this section, first we introduce discretization of the control space based on an equidistant partition of [0,T] as with a step size . The time interval is divided into n subinterval to .

The equidistant nodes on the set of control values correspond to the

i-th component of the control vector function that is divided into constants

. Furthermore, we assume that all components of the control vector function are at each time subinterval. Using the characteristic function, the

i-th component of the control function vector can be written as follows:

where

and

is a part of a piecewise linear function

on an interval

obtained by connecting the nodes

and

. For each control, we need its corresponding trajectory to evaluate the performance index. In accordance with the control, the corresponding trajectory must be in discretized form. So, corresponding to each piecewise linear control function, we solve the given system of differential equations that represent the dynamic system to be controlled; for

, we solve this numerically using any numerical solver of high accuracy (

: for instance, the

is a widely used, robust, and high-accuracy numerical method for solving Ordinary Differential Equations (ODEs), making it suitable for simulating the controlled system dynamics in optimal control problems) using the given initial conditions on the state variables. Based on generate vectors in

as

, the value of the performance index is found

to be minimized using any numerical integration formula of high accuracy.

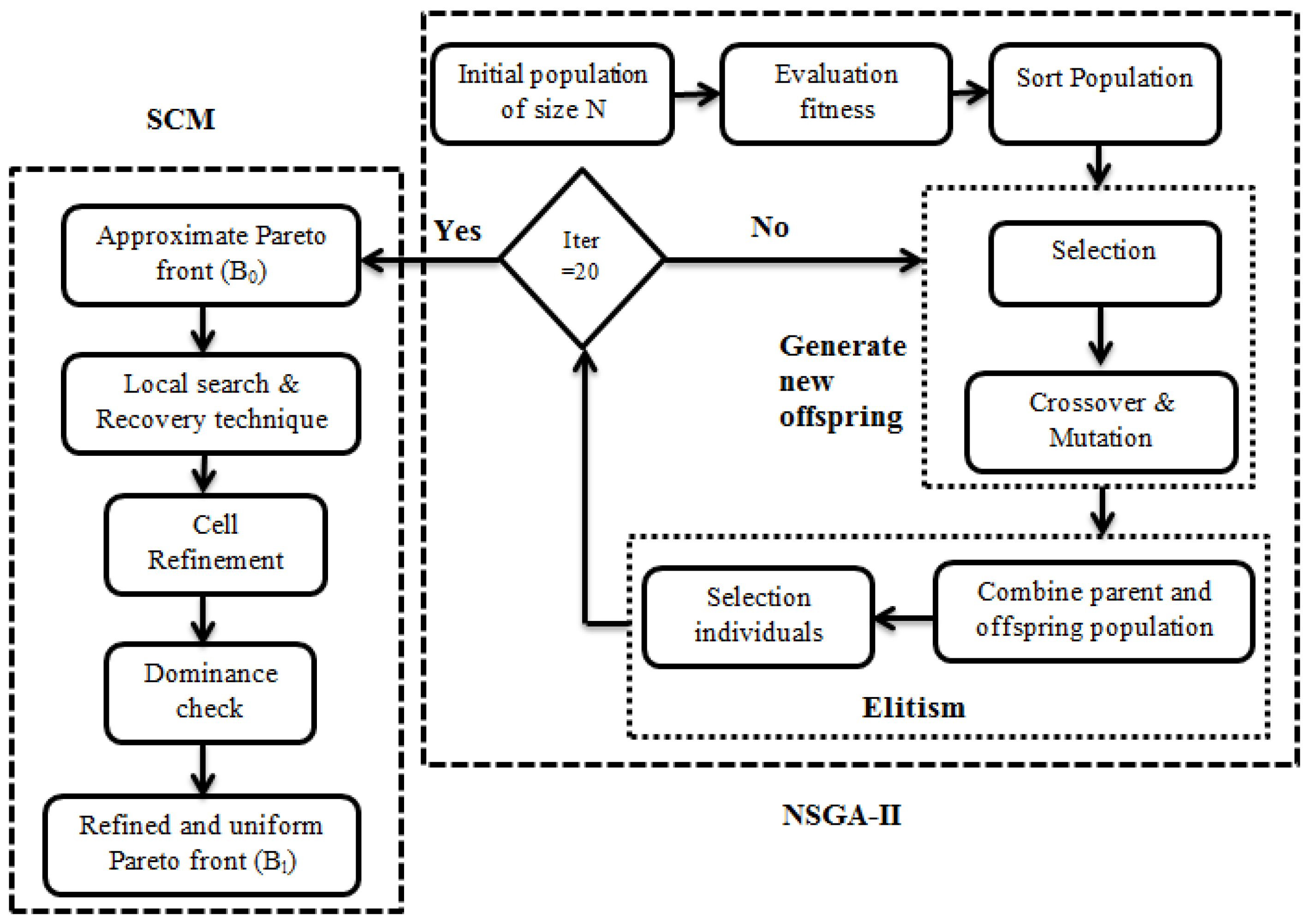

Now, we introduce a hybrid technique to solve the MOCP which includes the advantages of NSGA-II and SCM methods. In the hybrid method, the NSGA-II algorithm is first invoked. Initially, an initial population of solutions is generated and then over a small number of generation cycles, a set close to or on the Pareto frontier is generated. In the next step, this set of points is considered as input to the SCM method. Based on that, a set of cells containing these points is identified. Next, a neighborhood search method and a recovery process in the cell space are used to find the Pareto points. In order to obtain better results, the cells can be further refined [

33].

The set B contains all the cells of interest, which gradually increase during the process. The fitness of each cell in B is compared with all its orthogonal neighbors . Among the non-dominated cells, the cell with the steepest decent is added to the set . The current cell is part of the solution if it has no dominant neighbors. In this case, it is added to the set B. This process continues until no more non-dominant neighboring cells can be added to the current set. Next, cell refinement is performed on the cell set . Finally, after finding the solution set, the dominance of all cells is checked. It is noteworthy that instead of using the Jacobian gradient matrix, the dominant relation is used for simple cell mapping.

The purpose of using the NSGA-II algorithm in the hybrid method is to reduce the computational burden of the entire search space. Since we use a small population size in the NSGA-II, the entire Pareto set is not formed. The SCM method is used in the following. This method works in such a way that it evaluates neighboring cells.

In the hybrid method, SCM is applied to the set of cells containing the initial NSGA-II solutions (

) and their neighborhoods. This is in contrast to traditional SCM, which discretizes and evaluates the entire search space. This modification directly improves computational efficiency. Furthermore, the accuracy of the final solutions is enhanced through the “Subdivision” (refinement) process. Finally, the neighborhood search helps discover connected parts of the Pareto set that NSGA-II might have missed, leading to better convergence to the complete Pareto frontier. The flowchart of the hybrid method is shown in

Figure 1.

The pseudo-code of the proposed algorithm is presented below. Let z and D represent the destination cell and , respectively.

Pseudo-Code for Hybrid Algorithm

Here is the Algorithm 1:

| Algorithm 1: Pseudo-Code for Hybrid Algorithm |

1. First Discretize the control and state space 2. Ran NSGA-II algorithm to find initial solution 3. For to iter 3.1. Set , 3.2. While 3.2.1. Put in , in z and 3.3. For each 3.3.1. If dominate and 3.3.1.1. Put s in z 3.3.1.2. Put 3.4. If 3.4.1. Put z in S 3.5. If 3.5.1. If 3.5.1.1. Put z in 3.5.2. For each 3.5.2.1. If dominate and not exists such that s dominate b 3.5.2.2. Put s in S 3.6. 3.7. Put in N 4. Put the non-dominated terms of S in 5. For 5.1 (Subdivision): construct from Such that where , and B is n-dimensional cell can be expressed as 6. Selection: define the new collection |

6. Performance Metrics

In this section, we present the performance metrics proposed in the literature to evaluate the performance of NSGA-II, SCM, and hybrid algorithms. To evaluate the convergence of the solution to the true Pareto frontier, we use the generational distance metric (

), and to measure the diversity of the solutions, we use the diversity metric

. These metrics are defined as follows, respectively [

34],

where

S represents the solution set and

is defined as follows, where

and

represent the members of the solution set and the closest member to the Pareto correct set, respectively.

where

M represents number of objectives.

where

represents the Euclidean distance between the extreme points in true Pareto optimal frontier and

represents the boundary solutions of the Pareto set. Also,

shows the average of all distances

.

The smaller the and values, the better the algorithm will perform.

7. Numerical Results

In this section, first we present two examples of benchmark MOPs and then two problems that deal with multi-objective optimal controls for nonlinear dynamical systems to compare SCM, NSGA-II, and hybrid methods. The details of implementation of the algorithms for each problem are presented in the form of a table. For fair evaluation and comparison, we have considered the number of function evaluations to be approximately the same for all three methods. For Algorithm NSGA-II, the number of evaluations is obtained by the product of the number of iterations and the population size.

It should be noted that determining the optimal combination of generation count and population size is an optimization problem in itself. Since this falls outside the scope of the current study and due to the stochastic nature of the genetic algorithm (GA), the computation was repeated 20 times to obtain a statistical average of the performance metrics. Furthermore, the Wilcoxon rank-sum test was employed to evaluate the null hypothesis at a

confidence level. Because the MOCP problems in

Section 7.3 and

Section 7.4 do not have a known Pareto frontier, we ran each algorithm separately with

function cells and then combined the two solution sets into one. Among them, the non-dominated solutions were selected as the expected Pareto solutions.

7.1. Fonseca’s Problem

First, we consider Fonseca’s problem as [

35]

where

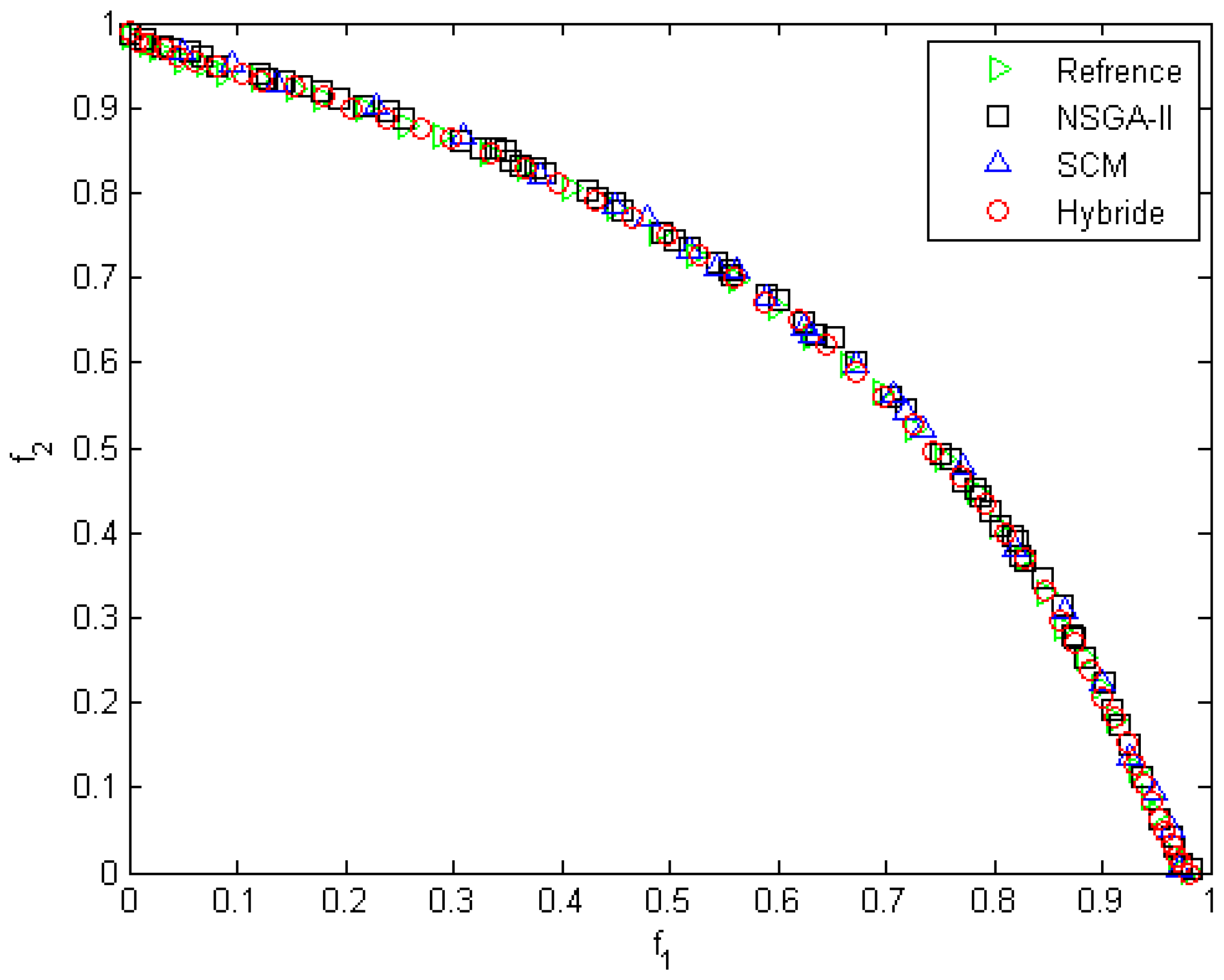

This is a non-convex problem with three variables and two objectives. The results of the exchange between objectives for all three algorithms are shown in

Figure 2. This figure depicts the true solutions with green triangles, and the solutions from the NSGA-II, SCM, and the hybrid method with squares, blue triangles, and circles, respectively. As can be observed, the points generated by the hybrid method (circles) are more uniformly distributed along the Pareto frontier compared to the other two methods.

Table 1 shows a comparison of methods for Fonseca’s problem. The metric average and diversity values are shown in

Table 1. The results presented in

Table 1 demonstrate the superior performance of the hybrid method, which yields convergence

and diversity

metrics of 0.026 and 0.102, respectively. These values, being lower than those obtained by the other methods, confirm the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid approach, and as a result, the hybrid method has better efficiency.

7.2. Deb’s Problem

This problem has two variables and two objectives defined as follows:

where

This test problem was introduced by Deb [

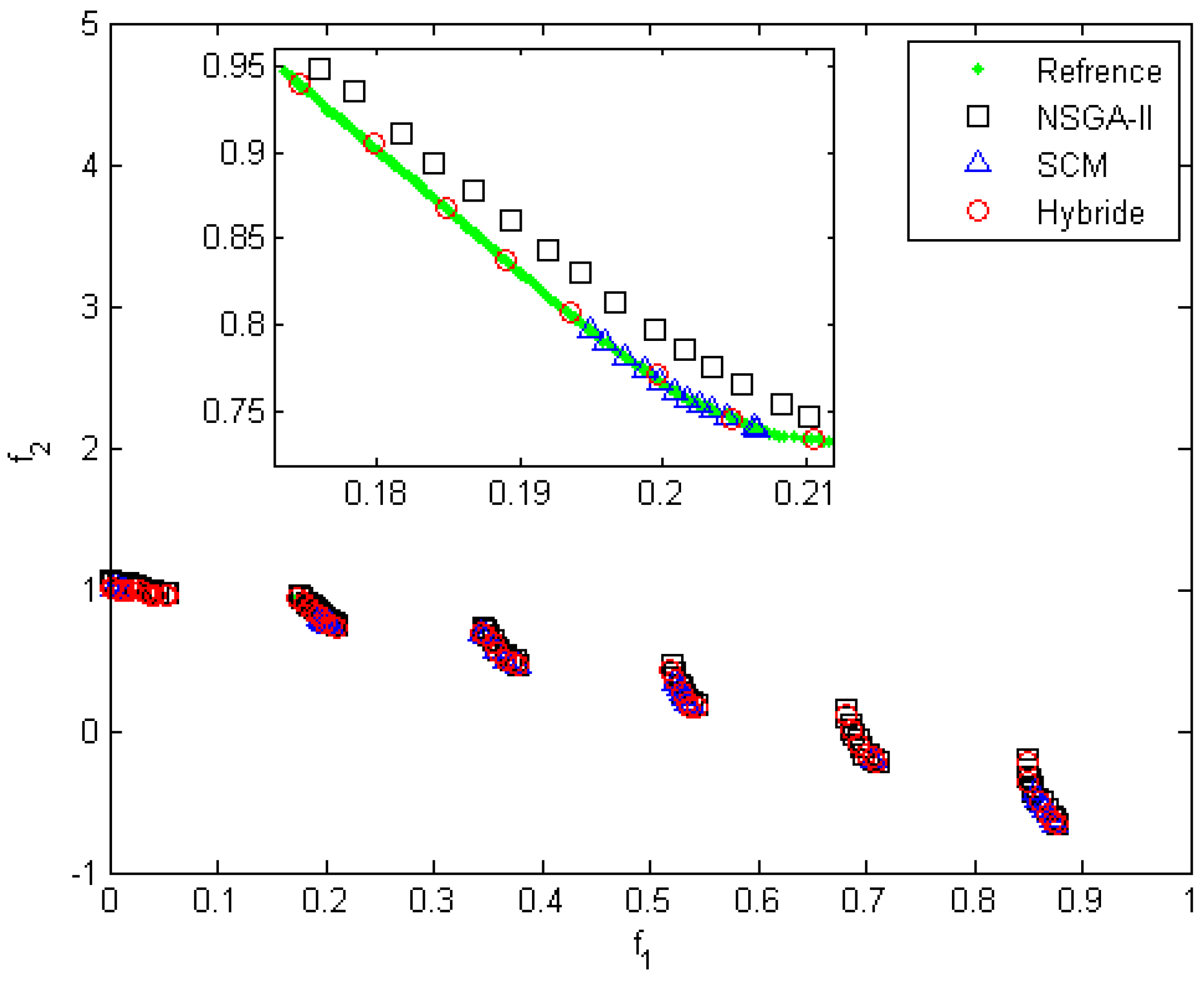

34]. The Pareto frontier consists of several discontinuous sections.

Figure 3 shows the Pareto frontier generated by hybrid, SCM, and NSGA-II algorithm. The details of the solution for this problem are reported in

Table 2. The zoom-in view in

Figure 3 depicts the distribution of the Pareto solution on the Pareto frontier obtained by the hybrid, NSGA-II, and SCM methods. As can be seen from the figure, the hybrid method generates more uniformly distributed solutions than the NSGA-II and SCM methods. It is noteworthy that the quality of the solution of the SCM method does not change significantly with the increase in the number of function evaluations. This is because a large part of the solution has been lost at the initial cell stage and is no longer recoverable.

Table 2 shows that although the hybrid method did not perform well compared to other methods in terms of CPU time, it performed better than other methods in terms of diversity and convergence of the solution. Although the proposed method takes more time to find the solutions due to the subdivision of the cells, the accuracy of its solutions is higher. In addition, the mentioned method produces a Pareto frontier with uniform points.

7.3. Home Heating System

The following problem is a multi-objective optimal control problem introduced by Bianchi, 2006 [

36]. This problem concerns a heating system with two objectives. The objectives are to minimize the energy input over an entire day and maximize the thermal comfort. The dynamic model and objectives are as follows:

where the state variables

and

denote the temperature of the water and room, respectively. The variable control

is the heat of the pump, and also

denotes the outside temperature and includes a disturbance

, and the control

u is limited to the range of 0 to 15,000.

The initial room and water temperatures are 19.5 °C.

Table 3 shows the parameter values.

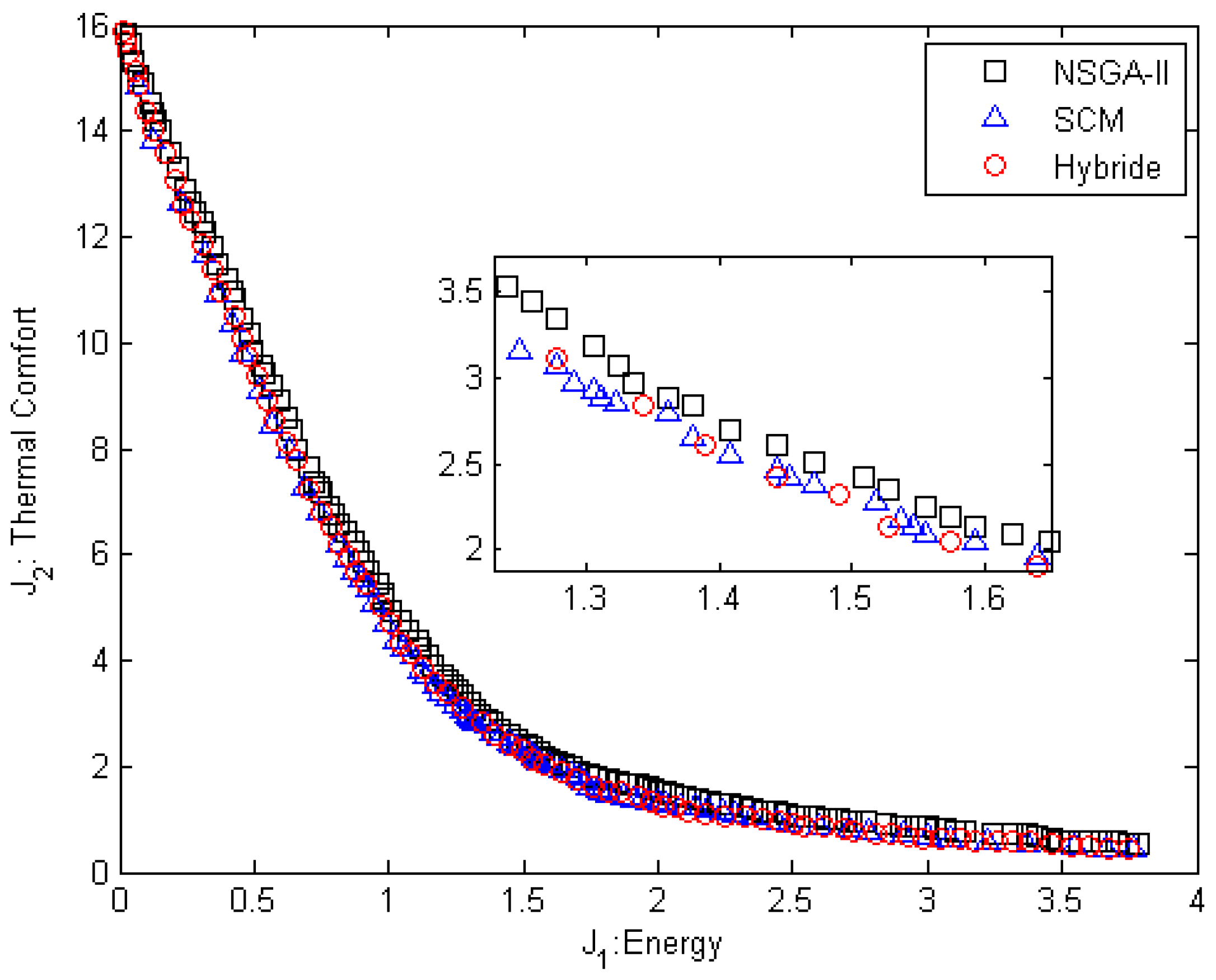

Figure 4 shows the Pareto frontier generated by all the three algorithms. According to

Figure 4, we understand that with increasing input energy, thermal comfort gradually decreases.

Figure 3 shows that the Pareto points obtained from the SCM method are mostly located in the curved part of the Pareto frontier, while the Pareto points obtained from the NSGA-II and hybrid methods are uniformly distributed along of the Pareto frontier. The zoom-in view in

Figure 4 depicts the distribution of the Pareto solution on the Pareto frontier obtained by the hybrid, NSGA-II, and SCM methods. As can be seen from the figure, the hybrid method generates more uniformly distributed solutions than the NSGA-II and SCM methods. The results of

Table 4 show that the values of

and

for the hybrid method are lower than the other methods. This means that the hybrid method has better convergence and diversity of solutions than the SCM and NSGA-II methods.

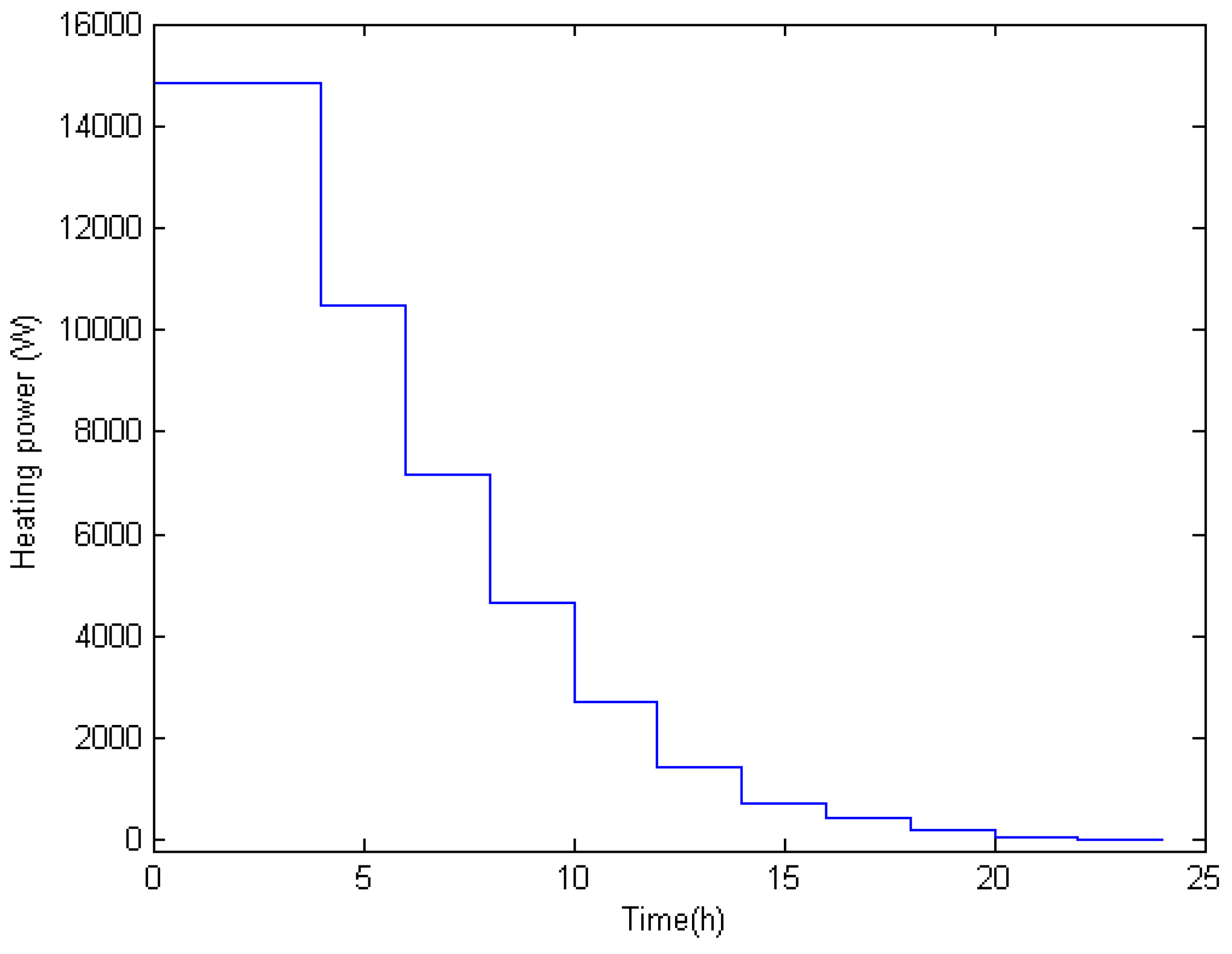

Figure 5 shows the control trajectory corresponding to the utopia point, the minimum Euclidean distance from the minimum values of the objectives. According to it, we find that more heating is used during the night when the cold increases, and then less heating is used during the day due to the increase in temperature.

7.4. Fed-Batch Bioreactor

This is the second multi-objective optimal control problem we will consider. This problem was introduced by Ohno et al. [

37] and is based on the fed-batch lysine fermentation process. The objectives are to obtain the maximum productivity and yield simultaneously. The equations and objectives of the problem are defined as follows:

where the states variables

, and

denote the biomass, substrate, product (lysine), and fermenter volume, respectively. The initial conditions are

. The control variable

denotes the volumetric rate of the feed stream, which contains a limiting substrate concentration

of 2.8 g/L. The parameters of the problem are given in

Table 5.

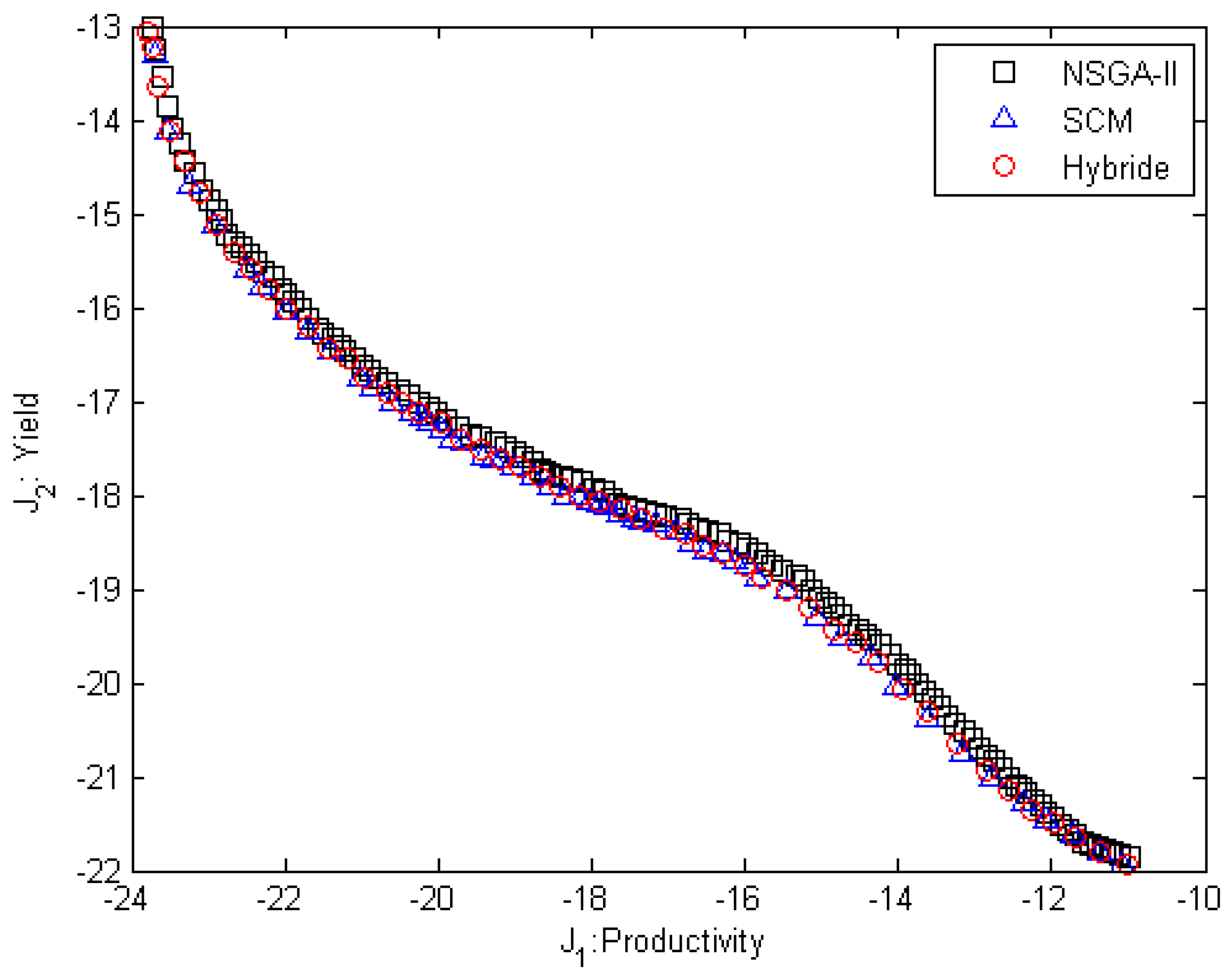

We show the Pareto frontier in

Figure 6 obtained by the three strategies. Details of the computational time and convergence rate and diversity of the solutions for all three methods are shown in

Table 6. The results presented in

Table 6 demonstrate the superior performance of the hybrid method, which yields convergence

and diversity

metrics of 0.017 and 0.008, respectively. These values, being lower than those obtained by the other methods, confirm the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid approach, and as a result, the hybrid method has better efficiency.

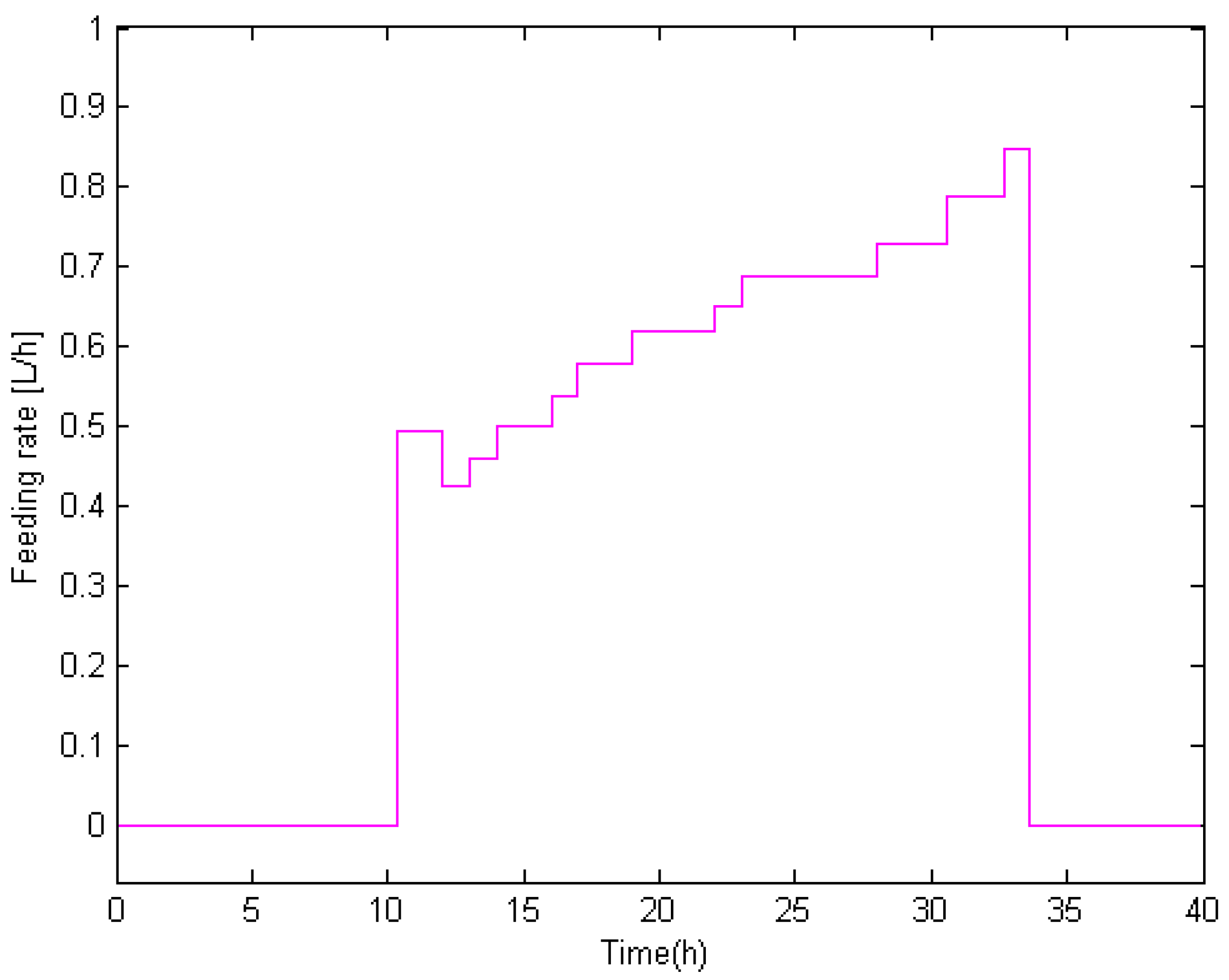

Figure 7 depicts the optimal feeding profile. From the figure, we can see that maximum lysine production is only achieved if only productivity is considered. However, if the goal is to find maximum yield, the height of the individual profile is reduced but it becomes more durable.

8. Results of Comparative Statistical Analysis

A comparative analysis using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was conducted to determine the efficacy of the three methods—NSGA-II, SCM, and the proposed hybrid method. The results for each performance metric, detailed below, are evaluated at a

confidence level (

). A detailed comparison of all three methods using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test is presented in

Table 7.

Time Performance: The statistical test yielded p-values of 0.082 and 0.096 for the respective comparisons. Since these values exceed the significance level of 0.05, we fail to reject the null hypothesis. This leads to the conclusion that there is no statistically significant difference in the time performance of the three methods under investigation.

Convergence Performance: In contrast, the analysis of the convergence metric resulted in p-values of 0.018 and 0.011. With these values being below the 0.05 threshold, the null hypothesis is rejected. This provides statistical evidence for a significant difference in convergence performance. Subsequent pairwise comparisons revealed that the hybrid method consistently outperformed both the NSGA-II and SCM methods.

Dispersion Performance: Similarly, for the dispersion metric, the p-values of 0.024 and 0.006 are statistically significant (). Therefore, we reject the null hypothesis, confirming a significant difference in the dispersion characteristics of the methods. The hybrid method was found to exhibit the lowest dispersion value, indicating its superior stability.

So it can be said that the hybrid method demonstrates a statistically significant advantage in terms of both solution quality (convergence) and reliability (diversity).

9. Conclusions

This study has introduced a novel hybrid methodology that effectively integrates the NSGA-II algorithm with the simple cell mapping (SCM) technique for solving multi-objective optimal control problems. The performance of the proposed approach was rigorously evaluated against established benchmarks and practical problems, with quantitative assessment based on two critical metrics: generational distance (GD), measuring convergence accuracy to the true Pareto front, and a diversity metric, evaluating the distribution uniformity of solution sets.

The results demonstrate that our hybrid method consistently outperforms conventional approaches across both benchmark and practical problems. The algorithm successfully generates solution sets with superior convergence characteristics while maintaining excellent diversity across the Pareto front. This balanced performance confirms the efficacy of combining evolutionary algorithms with set-oriented methods, leveraging NSGA-II’s global exploration capabilities with SCM’s precise local refinement. The proposed framework represents a significant advancement in multi-objective optimal control methodology, offering researchers and practitioners an effective tool for handling complex optimization scenarios where multiple competing objectives must be simultaneously considered. In addition, the Wilcoxon rank sum test also showed significant results for all examples presented in the objective space, which led to the rejection of the null hypothesis at the confidence level ().

Future research will be directed along several promising avenues to advance the methodological framework. A primary focus will be the enhancement of computational efficiency through the implementation of localized adaptive cell division, which intensifies refinement predominantly in regions proximate to the Pareto front, coupled with an adaptive time-stepping scheme that employs larger steps in domains with smooth dynamics and finer resolutions in sensitive, high-gradient areas. The scope of the algorithm will be expanded to tackle high-dimensional multi-objective optimal control problems (MOCPs) by leveraging adaptive cell mapping and dimension reduction techniques. Further extensions will aim to adapt the framework for real-time optimal control applications and problems featuring time-varying parameters.

The proposed method also has some limitations. While the hybrid method reduces the SCM search space, the initial phases of NSGA-II and cell refinement still pose computational challenges for very-high-dimensional problems (e.g., state dimensions ). The accuracy of the solution is inherently dependent on the granularity of the discretization of the control and state space, which is a common limitation in cell mapping methods.