From Nature to Science: A Review of the Applications of Pectin-Based Hydrogels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methodology

3. General Features About Pectin

| Source | Extraction Method | Outcomes | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Riang husk | Ultrasound-assisted using DESs | The combination Be: CA (1:5) proved to be the most effective for optimizing pectin yield from Riang husks. The optimal experimental settings were recorded at an ultrasonic power of 28.11 W, L/S ratio of 40 mL/g, and 60 min of extraction time. Inhibition of cellular damage upon exposure to H2O2 in HaCaT cells. Antioxidant activity at 0.26 ± 0.02 mmol Trolox equivalents/g. | [36] |

| GFP | Maceration | Citric acid-based hydrolysis conducted at 70–80 °C and a pH of 2–3 resulted in a 1.25-fold increase in the yield of HMP. FTIR analysis revealed 17.6% methoxyl content among samples. SEM-EDX evaluation evidences the high abundance of oxygen, potassium, and calcium. The 60–75% degree of esterification enabled the manufacture of jellies with improved color, texture, and odor. | [37] |

| Carrot pomace | Enzymatic | Enzyme-based extraction comprehended the activity of cellulase and hemicellulose. When combined with heat treatment, the implemented enzymes promoted the obtention of high pectin yields with improved purity, but lower molar mass. The implemented extraction process resulted in improved monosaccharide ratios. | [38] |

| Dillenia indica | Microwave-assisted | The optimized parameters were identified at 1:23.66 solid–solvent, 400 W microwave power, and 7 min of extraction time. The extracted pectin exhibited 9.61 ± 0.31%, 73.56 ± 1.86%, 74.15 ± 0.28%, and 1.16 ± 0.16% of methoxyl value, anhydrouronic acid content, degree of esterification, and protein content, respectively. The analyzed pectin displayed endothermic and exothermic behavior. The moisture content and as content were 7.23 ± 0.25% and 2.23 ± 0.25%, respectively. | [39] |

| Dried pomace | Microwave-assisted high-pressure CO2/H2O | The ideal conditions for extracting pectin consisted of 130 °C of temperature, 2.0 min of extraction time, and 22.5:1 mL/g of liquid-to-solid ratio. The implemented extraction procedure was 28.4%, saving 97% time when compared with conventional acid hydrolysis. The extracted pectin exhibited high purity when compared with commercial standards according to FTIR analysis. The obtained pectin displayed high emulsifying activity (61.67%) and upregulated solubility (87.36%). | [40] |

| Banana peels | Soxhlet | The optimal conditions for pectin extraction were at 80 °C and pH 4.5, resulting in 13.06% extraction yield. The determined compositional features consisted of 39.23% galacturonic acid content, 70.70% degree of esterification, and 11.50% methoxyl content. The extracted pectin, in combination with ascorbic acid, was ideal for the development of coatings for banana storage. Stored bananas with pectin-based coatings exhibited improved color retention and downregulated polyphenol-oxidase activity. | [41] |

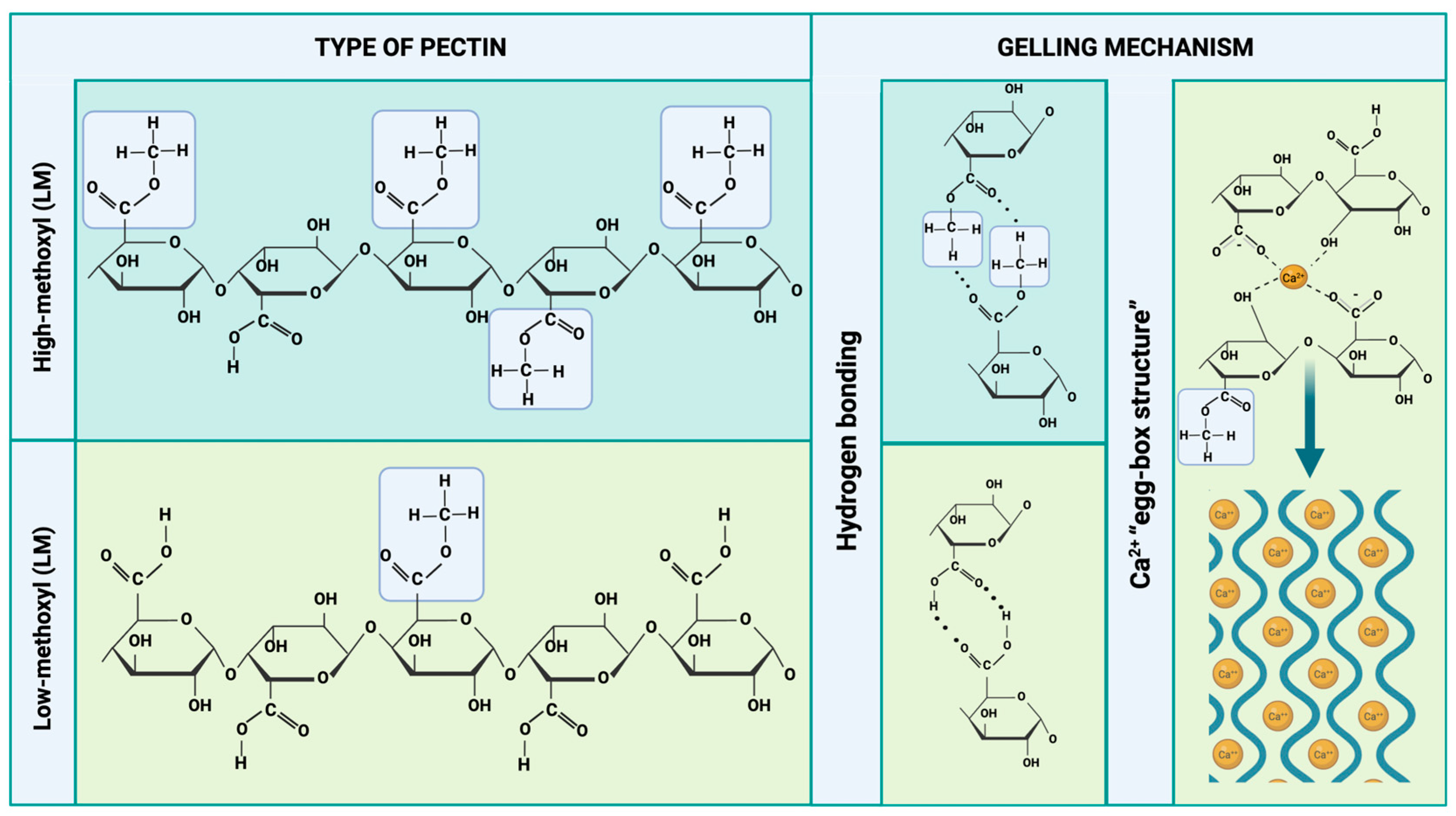

4. Gelling Mechanisms

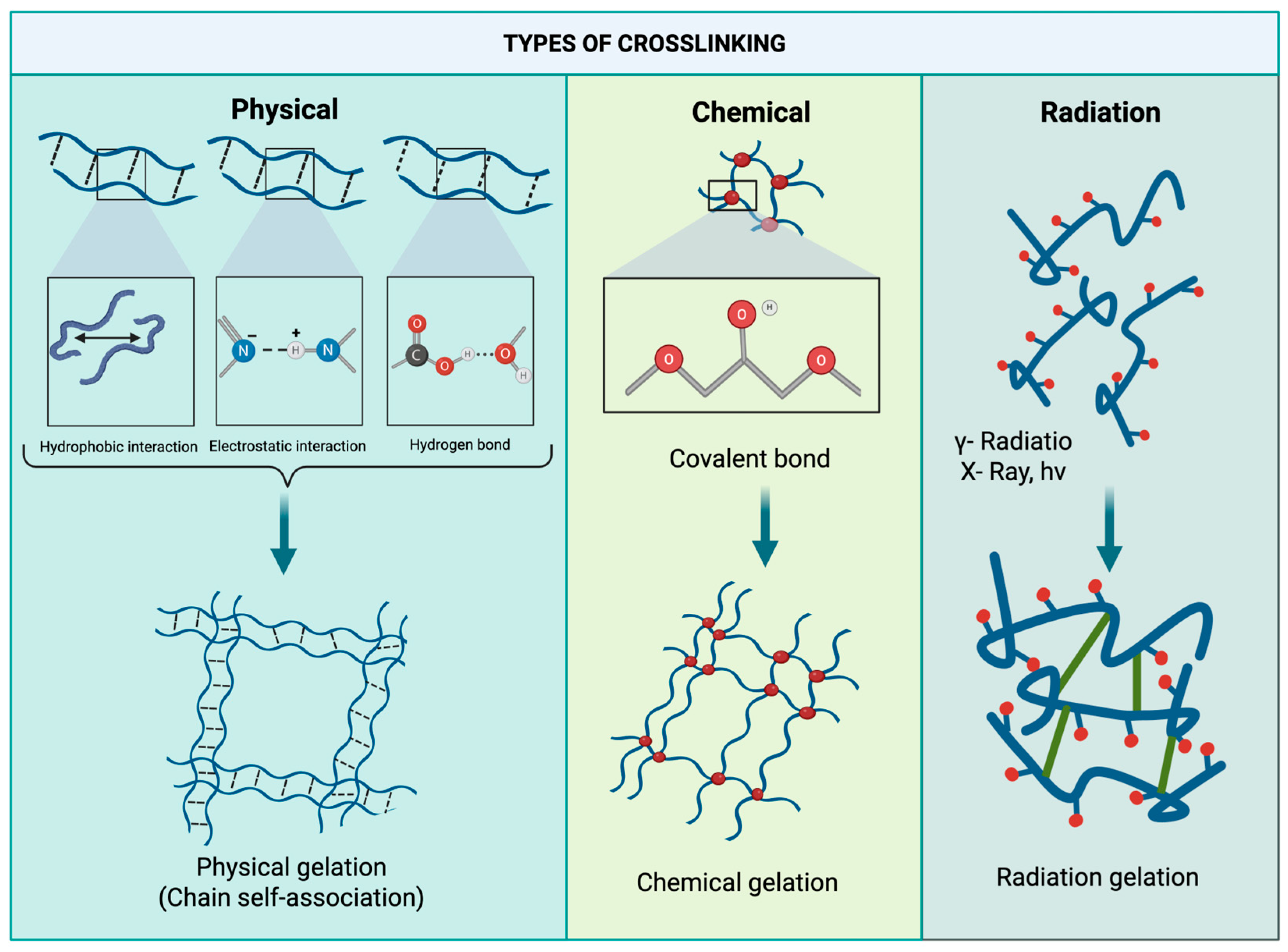

5. Pectin as a Source for Hydrogel

6. Pectin Hydrogel Applications

| Field of Application | Type of Hydrogel | Main Outcome | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agriculture | Sodium alginate/pectin hydrogel | Bacillus subtilis ZF71 was loaded into the synthesized hydrogel for controlling the incidence of Fusarium root rot in cucumber. The developed hydrogel exhibited a 90% coating uniformity among seeds. The developed hydrogel enabled the conservation of B. subtilis ZF71 cells’ viability. Greenhouse assays occurred in 53.26% control efficiency of Fusarium. | [55] |

| Environment | Pectin hydrogel-metal–organic framework | The experimental variables for evaluating metal removal capacity included contact time, pH, and concentration. The synthesized hydrogel exhibited 95.11% adsorption efficiency of Cu(II), and 97.75 mg/g capacity at pH 5. When evaluated towards Cu(II), the obtained hydrogel displayed 92.62% removal efficiency and 28.189 mg/g capacity at 1 min. | [56] |

| Biomedicine | Oxidized pectin-containing type I collagen hydrogel | Ozonation (25 mg/h) at a flow rate of 1 L/min) was utilized to increase the hepatogenic performance of pectin-containing type I collagen hydrogel. 40 min of ozonation improved the migration and albumin production in HepG2 cells upon exposure to the synthesized hydrogel. When HepG2 cells were transplanted into mature male Balb/c mice, the developed hydrogel, combined with 40 min of ozonation, decreased fibrotic changes and immunological responses after 14 days. | [57] |

| Food industry | Pectin and fish bone powder hydrogel | The synthesized hydrogel was utilized as a fat replacer in beef patty samples. The incorporation of the developed hydrogel reduced fat levels while increasing calcium content. The evaluation of 25% of the synthesized hydrogel decreased microbial count when evaluating beef patty samples at 4 °C for 7 days. At 25%, the reported hydrogel also downregulated thiobarbituric acid reactive substances levels. | [58] |

6.1. Drug Delivery

6.2. Tissues Engineering

6.3. Wound Healing

| Material | Features | Main Results | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Carboxyethyl chitosan (CEC)/oxidized pectin (OP)/polyethyleneimine (PEI) | It was characterized by FTIR, H NMR, and SEM. | Swelling ratios exceeded 700% for CEC/OP hydrogels and 1500% for CEC/OP/PEI hydrogels. They degraded at pH 1 and 3 but remained stable at pH 7.4 and 10 after 168 h. Antibacterial efficacy reached 97.3% for CEC/OP and 98.7% for CEC/OP/PEI against S. aureus and E. coli. | [9] |

| Carboxymethyl chitosan/pectin/polydopamine/rhEGF | It was characterized by FTIR, SEM, and rheological and mechanical properties evaluation. The hydrogel demonstrates a swelling capacity of 133.313 ± 3.45% | Antimicrobial activity reached inhibition rates of 52.2% against E. coli and 75.4% against S. aureus. | [10] |

| Chitosan, pectin, PVA, and 3-APDEMS | The developed hydrogels were characterized by FTIR and TGA. The change in swelling (max. 1275%) of hydrogels with change in pH of buffer media indicated the pH-dependent response of prepared stimuli responsive hydrogel. It possessed hydrophilicity (72°) and porosity (79%). | Anti-microbial potential of the fabricated hydrogels was analyzed via liquid diffusion method against E. coli Gram-negative bacteria and S. aureus Gram-positive bacteria. The optical density values of prepared hydrogels against S. aureus are slightly higher as compared to values in E. coli. | [61] |

| Pectin, polyvinylpyrrolidone, 3-APDEMS, and sepiolite clay | It was characterized by FTIR and SEM. The swelling response ranged from 890 to 1233% after 120 min, depending on crosslinker concentration. All hydrogels degraded after 21 days in PBS pH 7.4. | Hydrogels exhibited remarkable antimicrobial activity against E. coli (zones 23 and 18 mm) and B. subtilis (zone 16 mm). | [64] |

| Pectin–chitosan with ciprofloxacin-loaded dopamine-modified micelles | It was characterized by H NMR spectrometry, FT-IR, XRD, and DSC. | The developed hydrogels had a porosity between 43.1 and 85.4 mg/cm3, a density between 46.5 and 7.2 mg/cm3, and absorbed more than 150 times their own liquid weight. The pectin–chitosan hydrogels loaded with ciprofloxacin demonstrated drug release properties with enhanced antibacterial activity against Staphylococcus aureus after 24 h, were biocompatible in cytotoxicity and hemolysis assays, and in vivo animal studies and histological examinations showed that they were promising for preventing bacterial infections and promoting tissue regeneration. | [77] |

| Pectin-glutaraldehyde-glycerol | It was characterized by DSC and FTIR. Glutaraldehyde acted as a cross-linker and glycerol as a plasticizer. | The developed hydrogels exhibited antimicrobial activity against S. aureus, with a larger inhibition zone than MEBO (positive control). Their ability to maintain an acidic environment was expected to act as a barrier against microorganisms and reduce microbial activity. | [78] |

| Low methoxyl pectin, zeolite (Pz), or 2-thiobarbituric acid (PTBA) | It was characterized by SEM and DSC. Rheological properties were measured. SEM showed higher porosity for PTBA compared with Pz. | Hydrogels exhibited inhibitory effects with diameters of 11 mm (pectin), 8 mm (Pz), and 9 mm (PTBA) against E. coli, and 12 mm, 7 mm, and 9 mm against S. aureus. | [81] |

| Garlic carbon dots, acrylic acid, pectin, and ammonium persulfate | It was characterized by SEM and FTIR. The average pore size of the developed hydrogel was 1.00 µm. | The hydrogel exhibited an equilibrium swelling ratio of 6.21. The bactericidal rate after 24 h of contact against 1 × 106 CFU/mL of methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) and multidrug-resistant Salmonella Typhimurium (MRST) exceeded 99.99%. The healing rate of MRSA-infected mouse epidermal wounds reached 93.29% after 10 days of treatment. The hydrogel displayed excellent mechanical properties, which enabled better fitting to wound tissue and facilitated the release of garlic carbon dots. | [82] |

| Pectin–gelatin with pH dependent release of curcumin | It was characterized by FTIR, XRD, EDX, SEM, and BET analysis. The developed films presented a swelling degree in the range of 189–465% and a water retention capacity of 130–390%, depending on ZnO nanoparticle content. | The hydrogels exhibited improved compression strength and controlled degradation compared with controls. They promoted cell proliferation and migration for wound healing and showed antimicrobial activity against E. coli, S. aureus, and A. niger, with inhibition zones of 22, 19, and 17 mm, respectively. The antifungal activity was consistent with streptomycin (10 µg/disk) against A. niger. | [83] |

| Chitosan/pectin/ZnO nanoparticles | It was characterized by FTIR, XRD, EDX, SEM and BET analysis. The developed films presented the swelling degree and water retention ability in the range of 189–465 and 130–390%, respectively, according to the content of ZnO nanoparticles. Hydrogels showed an improved compression strength and controlled degradation in comparison with control. | Developed hydrogels demonstrated the improved cell proliferation and migration ability for the effective wound healing; and presented antimicrobial activity against 0.1% bacteria (E. coli and S. aureus) and fungi A. niger inoculums, with inhibition zones of 22, 19, and 17 mm, respectively. The antifungal activity of the developed hydrogel was consistent with that of commercial antifungal agent, Streptomycin (10 µg/disk) against A. niger. | [84] |

| Pectin and conjugated polyphosphate | Mechanical strength and flexibility of the developed hydrogel were investigated through rheology determination, and it was characterized by FTIR and UV-Vis. | The hemostatic hydrogel exhibited a microporous structure and a controlled release profile of vancomycin, which accelerated wound repair by preventing microbial invasion. Although the inhibition zones were smaller than with vancomycin solution, the hydrogel disk showed sufficient antibacterial performance to prevent infections. | [85] |

| Polysaccharide from Fructus Ligustri Lucidi (FLL-E) Incorporated in PVA/Pectin Hydrogels | It was characterized by SEM, UV-Vis, FTIR, NMR, and XRD. | The hydrogel promoted wound closure by enhancing collagen synthesis, preventing dysfunction in ECM remodeling via TIMP signaling, accelerating re-epithelialization, degrading inflammatory factors, and enhancing cell proliferation. Antimicrobial tests showed that pectin alone had limited activity, PVA none, and PVA-pectin less than pectin. However, FLL-E incorporation provided notable antibacterial activity against S. aureus and E. coli, indicating that activity was related to drug release. | [86] |

| Quaternized chitosan and pectin hydrogel loaded with propolis | It was characterized by SEM and FTIR. The disintegration of hydrogel films was studied after immersion in PBS, and water swelling showed increasing trends, reaching a plateau after 8 h. | The antibacterial activity of the hydrogel films was evaluated against S. aureus, S. epidermidis, and S. pyogenes. Blending QCS with pectin reduced antibacterial activity due to charge neutralization. However, incorporation of propolis provided antibacterial activity against S. aureus and S. pyogenes, but not against S. epidermidis. | [87] |

| Hyaluronic acid/Pectin injectable hydrogel | It was characterized by FTIR, SEM, and X-ray spectroscopy. The hydrogels exhibited self-healing due to Fe3+–COO− interactions, and demonstrated injectability and biocompatibility. | Excess Fe3+ levels provided antibacterial activity. The HA/PT hydrogels reduced S. aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa viability by ~99.9% after 120 min and achieved complete bacterial death after 360 min. | [88] |

| Chitosan, Oxidized Pectin, and Tantalum Metal–Organic Framework Hydrogel | It was characterized by SEM, energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy, EDAX mapping, XRD, FTIR, and N2 adsorption/desorption isotherm analysis. The developed hydrogel possessed a particle size of 51 nm and a specific surface area of ~26 m2/g. | The hydrogel films were effective against Yersinia ruckeri, Vibrio fluvialis, Edwardsiella tarda, Lactococcus garvieae, and Streptococcus iniae, with greater efficacy against Gram-positive strains. | [89] |

| Citrus peel pectin/metal composite hydrogel | It was characterized by texture analysis, FTIR, XPS, XRD, SEM, and TGA. The hydrogels had a weight of 412.9–694.78 mg and thickness of 1.23–2.41 mm. | The release of Cu2+ ions varied with pH, being faster at pH 10 and slower at pH 7. CPP–Cu hydrogels exhibited better antibacterial activity against S. aureus than CPP alone. | [90] |

| Sodium alginate-pectin/TiO2 | It was characterized by FTIR, XRD, FE-SEM, EDX, ICP-OES, and UV-Vis. The hydrogel showed a solubility of approximately 10%. | Antimicrobial potential was confirmed by liquid diffusion against E. coli and S. aureus. Inhibition was greater against S. aureus. | [91] |

| Pectin, polyacrylic acid and gallic acid (PC-PAAc/GA) | It was characterized by FTIR, XRD, TGA, AFM, and FE-SEM. The hydrogels reached swelling equilibrium in 350 min with 1300% swelling. | Hydrogels containing gallic acid exhibited clear inhibition zones against E. coli and S. aureus, whereas controls without gallic acid showed no inhibition. | [92] |

| Pectin, cellulose, silk fibroin, and Mg(OH)2 | It was characterized by EDX, FE-SEM, XRD, and FTIR. The hydrogels had a swelling ratio of 473–567%. Compressive strength, strain, and Young’s modulus were determined under dry and wet conditions. | Biofilm absorbance decreased progressively from polystyrene (0.76) to Pec-Cel (0.47) and Pec-Cel/SF/Mg(OH)2 nanobiocomposite (0.27), indicating higher antibacterial effect. | [93] |

| Clindamycin-loaded alginate/pectin/hyaluronic acid hydrogel | It was characterized by FE-SEM, film thickness, and pH evaluations. The water vapor transmission rate ranged from 1153 to 151 g/m2/24 h. | The hydrogels containing 300 µg clindamycin/mg reduced MRSA viability by >5 log (~99.999%). | [94] |

| Pectin-bacterial cellulose/polypyrrole | It was characterized by TA-XT2i, SEM, and FTIR. The optimal formulation contained 30% bacterial cellulose and exhibited enhanced ibuprofen release under electrical potential. | Hydrogels inhibited Streptococcus and Enterobacter. Ibuprofen-loaded hydrogels demonstrated activity against Gram-positive and Gram-negative strains except E. coli. | [95] |

| Quaternized chitosan and oxidized pectin | It was characterized by H NMR, FTIR, and XPS. The hydrogel showed self-healing within 30 min, rapid gelation (<1 min), a storage modulus of 394 Pa, and hardness of 700 mN. | QCS showed better antibacterial activity than oxidized pectin, while hydrogel samples displayed poor antibacterial performance, requiring > 500 mg/mL for effectiveness compared with standard antibiotics. | [96] |

| Water hyacinth cellulose (C), alginate (A), and pectin (P) | It was characterized by FTIR and XRD. The hydrogel exhibited a swelling ratio of 173.28% and a water content of 71.93%. | Hydrogels without quercetin showed no antibacterial activity, whereas incorporation of quercetin increased inhibition zones to 16.4 mm against S. aureus and 21.0 mm against P. aeruginosa. | [97] |

| Chitosan, dialdehyde bacterial cellulose, and pectin | It was characterized by FTIR and TGA. Swelling decreased from 1750 to 1200% with increasing content of chitosan and pectin. | Hydrogels containing chitosan exhibited inhibition zones of 3.3 to 11.9 mm against S. aureus but showed no inhibition against E. coli. | [98] |

6.4. Food

6.5. Agro-Industrial

6.6. Environmental and Bioremediation

6.7. Other Materials

7. Future Prospects

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Huo, H.; Shen, J.; Wan, J.; Shi, H.; Yang, H.; Duan, X.; Gao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Kuang, F.; Li, H.; et al. A Tough and Robust Hydrogel Constructed through Carbon Dots Induced Crystallization Domains Integrated Orientation Regulation. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 6221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petit, N.; Gomes, A.; Chang, Y.J.; Da Silva, J.; Leal, E.C.; Carvalho, E.; Gomes, P.; Browne, S. Development of a Bioactive Hyaluronic Acid Hydrogel Functionalised with Antimicrobial Peptides for the Treatment of Chronic Wounds. Biomater. Sci. 2025, 13, 3561–3575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, A.; Sharma, A.; Singh, A.; Han, S.S.; Sood, A. Strategy and Advancement in Hybrid Hydrogel and Their Applications: Recent Progress and Trends. Adv. Eng. Mater. 2024, 26, 2400944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, R.; Liu, Z. The Effect of Swelling/Deswelling Cycles on the Mechanical Behaviors of the Polyacrylamide Hydrogels. Polymer 2024, 312, 127634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stealey, S.; Dharmesh, E.; Bhagat, M.; Tyagi, A.M.; Schab, A.; Hong, M.; Osbourn, D.; Abu-Amer, Y.; Jelliss, P.A.; Zustiak, S.P. Super-Lubricous Polyethylene Glycol Hydrogel Microspheres for Use in Knee Osteoarthritis Treatments. npj Biomed. Innov. 2025, 2, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Z.; Li, J.; Ni, W.; Zhan, R.; Xu, X. Co-Delivery of Antimicrobial Peptide and Prussian Blue Nanoparticles by Chitosan/Polyvinyl Alcohol Hydrogels. Carbohydr. Polym. 2025, 348, 122873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adi Sulianto, A.; Adiyaksa, I.P.; Wibisono, Y.; Khan, E.; Ivanov, A.; Drannikov, A.; Ozaltin, K.; Di Martino, A. From Fruit Waste to Hydrogels for Agricultural Applications. Clean Technol. 2023, 6, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Jin, J.; Zhong, X.; Liu, L.; Tang, C.; Cai, L. Polysaccharide Hydrogels for Skin Wound Healing. Heliyon 2024, 10, e35014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, H.; Zhang, Y.; Zhou, C.; Zhang, C.; Liu, B. Engineering pH Responsive Carboxyethyl Chitosan and Oxidized Pectin -Based Hydrogels with Self-Healing, Biodegradable and Antibacterial Properties for Wound Healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 253, 127364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, D.; Qiu, P.; Hong, F.; Wang, Y.; Ren, P.; Cheng, X.; Wang, L.; Liu, T.; Liu, J.; Zhao, J. Polydopamine Modified Multifunctional Carboxymethyl Chitosan/Pectin Hydrogel Loaded with Recombinant Human Epidermal Growth Factor for Diabetic Wound Healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 274, 132917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.-P.; Jin, M.-Y.; Huang, S.; Zhuang, Z.-M.; Zhang, T.; Cao, L.-L.; Lin, X.-Y.; Chen, J.; et al. Versatile Dopamine-Functionalized Hyaluronic Acid-Recombinant Human Collagen Hydrogel Promoting Diabetic Wound Healing via Inflammation Control and Vascularization Tissue Regeneration. Bioact. Mater. 2024, 35, 330–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Chen, T.; Ren, C.; Bao, B.; Huang, R.; Sun, Y.; Yu, C.; Yang, Y.; Wong, W.T.; Zeng, Q.; et al. High-Strength Gelatin Hydrogel Scaffold with Drug Loading Remodels the Inflammatory Microenvironment to Enhance Osteoporotic Bone Repair. Adv. Mater. 2025, 37, 2501051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koivunotko, E.; Koivuniemi, R.; Monola, J.; Harjumäki, R.; Pridgeon, C.S.; Madetoja, M.; Linden, J.; Paasonen, L.; Laitinen, S.; Yliperttula, M. Cellulase-Assisted Platelet-Rich Plasma Release from Nanofibrillated Cellulose Hydrogel Enhances Wound Healing. J. Control. Release 2024, 368, 397–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, J.; Peng, J.; Hu, C.; Lei, S.; Wu, D. A General Strategy for Prepared Multifunction Double-Ions Agarose Hydrogel Dressing Promotes Wound Healing. Mater. Des. 2024, 240, 112854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rana, A.K.; Gupta, V.K.; Hart, P.; Thakur, V.K. Cellulose-Alginate Hydrogels and Their Nanocomposites for Water Remediation and Biomedical Applications. Environ. Res. 2024, 243, 117889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Das, T.; Patel, D.K. Efficient Removal of Cationic Dyes Using Lemon Peel-Chitosan Hydrogel Composite: RSM-CCD Optimization and Adsorption Studies. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 275, 133561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davydova, G.A.; Chaikov, L.L.; Melnik, N.N.; Gainutdinov, R.V.; Selezneva, I.I.; Perevedentseva, E.V.; Mahamadiev, M.T.; Proskurin, V.A.; Yakovsky, D.S.; Mohan, A.G.; et al. Polysaccharide Composite Alginate–Pectin Hydrogels as a Basis for Developing Wound Healing Materials. Polymers 2024, 16, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Cid, P.; Jiménez-Rosado, M.; Romero, A.; Pérez-Puyana, V. Novel Trends in Hydrogel Development for Biomedical Applications: A Review. Polymers 2022, 14, 3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pectic Polysaccharides and Their Functional Properties. In Polysaccharides; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 1729–1749. ISBN 978-3-319-16297-3.

- Scheller, H.V.; Jensen, J.K.; Sørensen, S.O.; Harholt, J.; Geshi, N. Biosynthesis of Pectin. Physiol. Plant. 2007, 129, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haas, K.T.; Wightman, R.; Peaucelle, A.; Höfte, H. The Role of Pectin Phase Separation in Plant Cell Wall Assembly and Growth. Cell Surf. 2021, 7, 100054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harholt, J.; Suttangkakul, A.; Vibe Scheller, H. Biosynthesis of Pectin. Plant Physiol. 2010, 153, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahasrabudhe, N.M.; Beukema, M.; Tian, L.; Troost, B.; Scholte, J.; Bruininx, E.; Bruggeman, G.; Van Den Berg, M.; Scheurink, A.; Schols, H.A.; et al. Dietary Fiber Pectin Directly Blocks Toll-Like Receptor 2–1 and Prevents Doxorubicin-Induced Ileitis. Front. Immunol. 2018, 9, 383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Methyl-Esterification, de-Esterification and Gelation of Pectins in the Primary Cell Wall. In Progress in Biotechnology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1996; pp. 151–172.

- Mohnen, D. Pectin Structure and Biosynthesis. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2008, 11, 266–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dranca, F.; Talón, E.; Vargas, M.; Oroian, M. Microwave vs. Conventional Extraction of Pectin from Malus Domestica ‘Fălticeni’ Pomace and Its Potential Use in Hydrocolloid-Based Films. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 121, 107026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, L.; Cheng, L.; Yang, Q.; Shi, K.; Han, F.; Luo, W.; Duan, S. Source, Extraction, Properties, and Multifunctional Applications of Pectin: A Short Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 2883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Chen, X.; Dai, J.; Cui, H.; Lin, L. Edible Films of Pectin Extracted from Dragon Fruit Peel: Effects of Boiling Water Treatment on Pectin and Film Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 147, 109324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çilingir, S.; Goksu, A.; Sabanci, S. Production of Pectin from Lemon Peel Powder Using Ohmic Heating-Assisted Extraction Process. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2021, 14, 1349–1360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, X.; Zhu, Y.; Shu, C.; Gao, J.; Liu, F.; Pan, S. Extraction of Pectin from Satsuma Mandarin Peel: A Comparison of High Hydrostatic Pressure and Conventional Extractions in Different Acids. Molecules 2022, 27, 3747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divyashri, G.; Krishna Murthy, T.P.; Ragavan, K.V.; Sumukh, G.M.; Sudha, L.S.; Nishka, S.; Himanshi, G.; Misriya, N.; Sharada, B.; Anjanapura Venkataramanaiah, R. Valorization of Coffee Bean Processing Waste for the Sustainable Extraction of Biologically Active Pectin. Heliyon 2023, 9, e20212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Amo-Mateos, E.; Cáceres, B.; Coca, M.; Teresa García-Cubero, M.; Lucas, S. Recovering Rhamnogalacturonan-I Pectin from Sugar Beet Pulp Using a Sequential Ultrasound and Microwave-Assisted Extraction: Study on Extraction Optimization and Membrane Purification. Bioresour. Technol. 2024, 394, 130263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham Tan Quoc, L. Physicochemical characteristics and antioxidant activities of banana peels pectin extracted with microwave-assisted extraction. J. Agricult. Forest 2022, 68, 145–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento Oliveira, A.; de Almeida Paula, D.; Basílio de Oliveira, E.; Henriques Saraiva, S.; Stringheta, P.C.; Mota Ramos, A. Optimization of Pectin Extraction from Ubá Mango Peel through Surface Response Methodology. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 113, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandel, V.; Biswas, D.; Roy, S.; Vaidya, D.; Verma, A.; Gupta, A. Current Advancements in Pectin: Extraction, Properties and Multifunctional Applications. Foods 2022, 11, 2683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saelee, M.; Myo, H.; Khat-udomkiri, N. Sustainable Pectin Extraction from Riang Husk Using Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction with Deep Eutectic Solvents and Its Potential in Antipollution Products. Ultrason. Sonochemistry 2025, 114, 107256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iqbal, M.A.; Akram, S.; Khalid, S.; Amin, L.; Ahmad, F.; Malhat, F.; Muhammad, G.; Ashraf, R.; Mushtaq, M. Citric Acid–Assisted Extraction of High Methoxy Pectin from Grapefruit Peel and Its Application as Milk Stabilizer. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 6134–6150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laet, E.; Bernaerts, T.; Morren, L.; Vanmarcke, H.; Van Loey, A.M. The Use of Different Cell Wall Degrading Enzymes for Pectin Extraction from Carrot Pomace, in Comparison to and in Combination with an Acid Extraction. Foods 2025, 14, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, N.; Nickhil, C.; Deka, S.C. Optimization and Characterization of Physicochemical, Morphological, Structural, Thermal, and Rheological Properties of Microwave-Assisted Extracted Pectin from Dillenia Indica Fruit. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 295, 139583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biltekin, S.İ.; Elik Demir, A.; Koçak Yanik, D.; Göğüş, F. A Novel and Environmentally Friendly Technique for Extracting Pectin from Black Carrot Pomace: Optimization of Microwave-Assisted High-Pressure CO2/H2O and Characterization of Pectin. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2025, 18, 2531–2544. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Athanasopoulou, E.; Charpa, P.; Sarafidou, M.; Koutinas, A.; Tsironi, T. Extraction of Pectin from Banana Peels and Utilization in a Bioactive Coating for Postharvest Banana Preservation. Discov. Food 2025, 5, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Yi, J.; Ma, Y.; Bi, J. The Role of Amide Groups in the Mechanism of Acid-Induced Pectin Gelation: A Potential pH-Sensitive Hydrogel Based on Hydrogen Bond Interactions. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 141, 108741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Chen, H.; Wang, Z.; Chen, Z.; Yu, S. Sugarcane Molasses-Induced Gelation of Low-Methoxy Pectin. Ind. Crops Products 2023, 205, 117509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Tyramine Modification of High and Low Methoxyl Pectin: Physicochemical Properties, Antioxidant Activity, and Gelation Behavior. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 144, 108949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Li, R.; Guo, X.; Liu, P.; Zhang, J. Effect of Apple High-Methoxyl Pectin on Heat-Induced Gelation of Silver Carp Myofibrillar Protein. Food Chem. 2024, 441, 138366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Qi, J.; Liao, J.; Liu, Z.; He, C. Study on Low Methoxyl Pectin (LMP) with Varied Molecular Structures Cross-Linked with Calcium Inducing Differences in the Gel Properties. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 146, 109271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padma Ishwarya, S.; Sandhya, R.; Nisha, P. Advances and Prospects in the Food Applications of Pectin Hydrogels. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 4393–4417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sadeghi, M. Pectin-Based Biodegradable Hydrogels with Potential Biomedical Applications as Drug Delivery Systems. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnology 2011, 2, 36–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajaz, N.; Khalid, I.; Minhas, M.U.; Barkat, K.; Khan, I.U.; Syed, H.K.; Asghar, S.; Munir, R.; Aslam, F. Pectin-Based Hydrogels with Adjustable Properties for Controlled Delivery of Nifedipine: Development and Optimization. Polym. Bull. 2020, 77, 6063–6083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwarit, T.; Masavang, S.; Mahe, J.; Sommano, S.; Ruksiriwanich, W.; Brachais, C.H.; Chambin, O.; Jantrawut, P. Mango (Cv. Nam Dokmai) Peel as a Source of Pectin and Its Potential Use as a Film-Forming Polymer. Food Hydrocoll. 2020, 102, 105611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lugao, A.B.; Onia, S.; Malmonge, M. Use of Radiation in the Production of Hydrogels. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. B Beam Interact. Mater. At. 2021, 185, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Groult, S.; Buwalda, S.; Budtova, T. Pectin Hydrogels, Aerogels, Cryogels and Xerogels: Influence of Drying on Structural and Release Properties. Eur. Polym. J. 2021, 149, 110386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, W.; Wang, Z.; Xiao, Y.; Zhang, S.; Wang, J. Advances in Crosslinking Strategies of Biomedical Hydrogels. Biomater. Sci. 2019, 7, 843–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, C.; Huang, W.; Zou, Y.; Huang, W.; Fei, P.; Zhang, G. Fabrication of Phenylalanine Amidated Pectin Using Ultra-Low Temperature Enzymatic Method and Its Hydrogel Properties in Drug Sustained Release Application. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 216, 263–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdukerim, R.; Li, L.; Li, J.-H.; Xiang, S.; Shi, Y.-X.; Xie, X.-W.; Chai, A.-L.; Fan, T.-F.; Li, B.-J. Coating Seeds with Biocontrol Bacteria-Loaded Sodium Alginate/Pectin Hydrogel Enhances the Survival of Bacteria and Control Efficacy against Soil-Borne Vegetable Diseases. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 279, 135317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vigneswararajah, V.; Thavarajah, N.; Fernando, X. Synthesis of Pectin Hydrogels from Grapefruit Peel for the Adsorption of Heavy Metals from Water. Technologies 2025, 13, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khosrowshahi, N.D.; Amini, H.; Khoshfetrat, A.B.; Rahbarghazi, R. Oxidized Pectin/Collagen Self-Healing Hydrogel Accelerated the Regeneration of Acute Hepatic Injury in a Mouse Model. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 304, 140931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thammawong, W.; Chanshotikul, N.; Sriuttha, M.; Kwantrairat, S.; Hemung, B.-O. Utilization of a Hydrogel Made from Mixed Pectin/Fish Bone Powder as a Fat Replacer in Beef Patty. Appl. Food Res. 2025, 5, 101067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vesvoranan, O.; Liu, B.S.; Zheng, Y.; Wagner, W.L.; Sutlive, J.; Chen, Z.; Khalil, H.A.; Ackermann, M.; Mentzer, S.J. Active Loading of Pectin Hydrogels for Targeted Drug Delivery. Polymers 2023, 15, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, S.S.; Ji, S.M.; Park, M.J.; Suneetha, M.; Uthappa, U.T. Pectin Based Hydrogels for Drug Delivery Applications: A Mini Review. Gels 2022, 8, 834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hafeez, S.; Islam, A.; Durrani, A.K.; Butt, M.T.Z.; Rehmat, S.; Khurshid, A.; Khan, S.M. Fabrication of Pectin-Based Stimuli Responsive Hydrogel for the Controlled Release of Ceftriaxone. Chem. Pap. 2022, 77, 1809–1819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Chang, R.; Shen, J.; Wang, Y.; Song, H.; Kang, X.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, S.; Qin, J. Self-Healing Pectin/Cellulose Hydrogel Loaded with Limonin as TMEM16A Inhibitor for Lung Adenocarcinoma Treatment. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 219, 754–766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetouani, A.; Elkolli, M.; Haffar, H.; Chader, H.; Riahi, F.; Varacavoudin, T.; Le Cerf, D. Multifunctional Hydrogels Based on Oxidized Pectin and Gelatin for Wound Healing Improvement. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 212, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehmat, S.; Rizvi, N.B.; Khan, S.U.; Ghaffar, A.; Islam, A.; Khan, R.U.; Mehmood, A.; Butt, H.; Rizwan, M. Novel Stimuli-Responsive Pectin-PVP-Functionalized Clay Based Smart Hydrogels for Drug Delivery and Controlled Release Application. Front. Mater. 2022, 9, 823545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quadrado, R.F.N.; Macagnan, K.L.; Moreira, A.S.; Fajardo, A.R. Redox-Responsive Hydrogels of Thiolated Pectin as Vehicles for the Smart Release of Acetaminophen. React. Funct. Polym. 2022, 181, 105448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, J.; Arnold, R.D.; Wicker, L. Pectin and Charge Modified Pectin Hydrogel Beads as a Colon-Targeted Drug Delivery Carrier. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2013, 104, 116–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morello, G.; De Iaco, G.; Gigli, G.; Polini, A.; Gervaso, F. Chitosan and Pectin Hydrogels for Tissue Engineering and In Vitro Modeling. Gels 2023, 9, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markov, P.A.; Krachkovsky, N.S.; Durnev, E.A.; Martinson, E.A.; Litvinets, S.G.; Popov, S.V. Mechanical Properties, Structure, Bioadhesion, and Biocompatibility of Pectin Hydrogels. J. Biomed. Mater. Res.—Part A 2017, 105, 2572–2581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popov, S.; Paderin, N.; Khramova, D.; Kvashninova, E.; Melekhin, A.; Vityazev, F. Characterization and Biocompatibility Properties In Vitro of Gel Beads Based on the Pectin and κ-Carrageenan. Mar. Drugs 2022, 20, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batool, N.; Sarfraz, R.M.; Mahmood, A.; Rehman, U.; Zaman, M.; Akbar, S.; Almasri, D.M.; Gad, H.A. Development and Evaluation of Cellulose Derivative and Pectin Based Swellable pH Responsive Hydrogel Network for Controlled Delivery of Cytarabine. Gels 2023, 9, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mokhtar, M.H.; Syahir, M.; Hamzah, A.; Hezri Mokhtar, M.; Amirah, S.; Latiff, A.; Hasraf, N.; Nayan, M. Physical Characterisation and In-Vitro Kinetic Modelling on Drug Release Study of Polyvinyl Alcohol/Polyethylene Glycol/Pectin Hydrogel for Cartilage Tissue Application. ASM Sci. 2022, 16, 68–75. [Google Scholar]

- Vowden, K.; Vowden, P. Wound Dressings: Principles and Practice. Surgery 2017, 35, 489–494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathieu, D.; Linke, J.-C.; Wattel, F. Chapter 2.2.9 Non-healing wounds. In Handbook on Hyperbaric Medicin; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, S.; DiPietro, L.A. Critical Review in Oral Biology & Medicine: Factors Affecting Wound Healing. J. Dent. Res. 2010, 89, 219–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinha, D.; Seth, S.; Das, A.; Bhattacharyya, U.K.; Ghosh, K.; Nandi, A.; Banerjee, P.; Ray, S. Tuned Gum Ghatti and Pectin for Green Synthesis of Novel Wound Dressing Material: Engineering Aspects and in Vivo Study. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2022, 76, 103730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.S.; Sun, K.H.; Park, Y. Evaluation of Melia Azedarach Extract-Loaded Poly (Vinyl Alcohol)/Pectin Hydrogel for Burn Wound Healing. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0270281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, K.; Hao, Y.; Liu, Y.; Cao, R.; Zhang, X.; He, S.; Wen, J.; Zheng, W.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y. Preparation of Pectin-Chitosan Hydrogels Based on Bioadhesive-Design Micelle to Prompt Bacterial Infection Wound Healing. Carbohydr. Polym. 2023, 300, 120272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordin, N.N.; Aziz, N.K.; Naharudin, I.; Anuar, N.K. Effects of Drug-Free Pectin Hydrogel Films on Thermal Burn Wounds in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetic Rats. Polymers 2022, 14, 2873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Noruzi, E.B.; Aliabadi, H.A.M.; Sheikhaleslami, S.; Akbarzadeh, A.R.; Hashemi, S.M.; Gorab, M.G.; Maleki, A.; Cohan, R.A.; Mahdavi, M.; et al. Recent Advances on Biomedical Applications of Pectin-Containing Biomaterials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 217, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsakhawy, M.A.; Abdelmonsif, D.A.; Haroun, M.; Sabra, S.A. Naringin-Loaded Arabic Gum/Pectin Hydrogel as a Potential Wound Healing Material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 701–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocaaga, B.; Kurkcuoglu, O.; Tatlier, M.; Dinler-Doganay, G.; Batirel, S.; Güner, F.S. Pectin–Zeolite-Based Wound Dressings with Controlled Albumin Release. Polymers 2022, 14, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Song, L.; Yang, X.; Ye, Y.; Sun, J.; Ji, J.; Geng, S.; Ning, D.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Antimicrobial Carbon Dots/Pectin-Based Hydrogel for Promoting Healing Processes in Multidrug-Resistant Bacteria-Infected Wounds. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 264, 130477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bostancı, N.S.; Büyüksungur, S.; Hasirci, N.; Tezcaner, A. pH Responsive Release of Curcumin from Photocrosslinked Pectin/Gelatin Hydrogel Wound Dressings. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 134, 112717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soubhagya, A.S.; Moorthi, A.; Prabaharan, M. Preparation and Characterization of Chitosan/Pectin/ZnO Porous Films for Wound Healing. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 157, 135–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Chang, R.; Liu, X.; Ma, X.; Chen, D.; Wang, Y.; Li, W.; Qin, J. Self-Healing Hydrogel Based on Polyphosphate-Conjugated Pectin with Hemostatic Property for Wound Healing Applications. Biomater. Adv. 2022, 139, 212974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, Y.; Hu, L.; Chen, X.; Zuo, L.; Bai, X.; Du, W.; Xu, N. Antibacterial and Anti-Inflammatory Polysaccharide from Fructus Ligustri Lucidi Incorporated in PVA/Pectin Hydrogels Accelerate Wound Healing. Molecules 2024, 29, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phonrachom, O.; Charoensuk, P.; Kiti, K.; Saichana, N.; Kakumyan, P.; Suwantong, O. Potential Use of Propolis-Loaded Quaternized Chitosan/Pectin Hydrogel Films as Wound Dressings: Preparation, Characterization, Antibacterial Evaluation, and in Vitro Healing Assay. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 241, 124633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, N.-G.; Chandika, P.; Kim, S.-C.; Won, D.-H.; Park, W.S.; Choi, I.-W.; Lee, S.G.; Kim, Y.-M.; Jung, W.-K. Fabrication and Characterization of Ferric Ion Cross-Linked Hyaluronic Acid/Pectin-Based Injectable Hydrogel with Antibacterial Ability. Polymer 2023, 271, 125808. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-dolaimy, F.; Altimari, U.S.; Abdulwahid, A.S.; Mohammed, Z.I.; Hameed, S.M.; Dawood, A.H.; Alsalamy, A.H.; Suliman, M.; Abbas, A.H.R. Hydrogel Assisted Synthesis of Polymeric Materials Based on Chitosan, Oxidized Pectin, and Tantalum MOF Nanostructures as Potent Antibiotic Agents Against Common Pathogenic Strains Between Humans and Aquatic. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. 2024, 34, 874–884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Yu, S.; Chen, H.; Guo, X.; Cai, P.; Meng, H. One-Step Electrogelation of Pectin Hydrogels as a Simpler Alternative for Antibacterial 3D Printing. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2022, 654, 129964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mallakpour, S.; Mohammadi, N. Development of Sodium Alginate-Pectin/TiO2 Nanocomposites: Antibacterial and Bioactivity Investigations. Carbohydr. Polym. 2022, 285, 119226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sayed, A.; Hany, F.; Abdel-Raouf, M.E.-S.; Mahmoud, G.A. Gamma Irradiation Synthesis of Pectin- Based Biohydrogels for Removal of Lead Cations from Simulated Solutions. J. Polym. Res. 2022, 29, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eivazzadeh-Keihan, R.; Ahmadpour, F.; Aliabadi, H.A.M.; Radinekiyan, F.; Maleki, A.; Madanchi, H.; Mahdavi, M.; Shalan, A.E.; Lanceros-Méndez, S. Pectin-Cellulose Hydrogel, Silk Fibroin and Magnesium Hydroxide Nanoparticles Hybrid Nanocomposites for Biomedical Applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2021, 192, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, N.; Cao, J.; Lee, J.; Kim, H.; Yoo, J.-W. Development of Clindamycin-Loaded Alginate/Pectin/Hyaluronic Acid Composite Hydrogel Film for the Treatment of MRSA-Infected Wounds. J. Pharm. Investig. 2021, 51, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krathumkhet, N.; Imae, T.; Paradee, N. Electrically Controlled Transdermal Ibuprofen Delivery Consisting of Pectin-Bacterial Cellulose/Polypyrrole Hydrogel Composites. Cellulose 2021, 28, 11451–11463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chanmontri, M.; Swilem, A.E.; Mutch, A.L.; Grøndahl, L.; Suwantong, O. Physicochemical and in Vitro Biological Evaluation of an Injectable Self-Healing Quaternized Chitosan/Oxidized Pectin Hydrogel for Potential Use as a Wound Dressing Material. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 242, 124984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiwarit, T.; Chanabodeechalermrung, B.; Kantrong, N.; Chittasupho, C.; Jantrawut, P. Fabrication and Evaluation of Water Hyacinth Cellulose-Composited Hydrogel Containing Quercetin for Topical Antibacterial Applications. Gels 2022, 8, 767. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, N.; Ngwabebhoh, F.A.; Zandraa, O.; Chaudhry, M.; Saha, N.; Saha, T.; Solovyov, D.; Salms, G.; Salms, G.; Sosnik, A.; et al. Self-Crosslinked Polysaccharide-Based Injectable Hydrogels Formulated with Chitosan/Pectin/Bacterial Cellulose. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2024, 142, e57752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzoor, A.; Dar, A.H.; Pandey, V.K.; Shams, R.; Khan, S.; Panesar, P.S.; Kennedy, J.F.; Fayaz, U.; Khan, S.A. Recent Insights into Polysaccharide-Based Hydrogels and Their Potential Applications in Food Sector: A Review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 213, 987–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Said, N.S.; Olawuyi, I.F.; Lee, W.Y. Pectin Hydrogels: Gel-Forming Behaviors, Mechanisms, and Food Applications. Gels 2023, 9, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopjar, M.; Ćorković, I.; Buljeta, I.; Šimunović, J.; Pichler, A. Fortification of Pectin/Blackberry Hydrogels with Apple Fibers: Effect on Phenolics, Antioxidant Activity and Inhibition of α-Glucosidase. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gautam, M.; Santhiya, D. Pectin/PEG Food Grade Hydrogel Blend for the Targeted Oral Co-Delivery of Nutrients. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2019, 577, 637–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mekala, S.; Silva, E.K.; Saldaña, M.D.A. Ultrasound-Assisted Production of Emulsion-Filled Pectin Hydrogels to Encapsulate Vitamin Complex: Impact of the Addition of Xylooligosaccharides, Ascorbic Acid and Supercritical CO2 Drying. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2022, 76, 102907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, W.; Jia, X.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, H.; Zhu, Q.; Yin, L. Interpenetrating Polymer Network Hydrogels of Soy Protein Isolate and Sugar Beet Pectin as a Potential Carrier for Probiotics. Food Hydrocoll. 2021, 113, 106453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellinas, C.; Ramos, M.; Jiménez, A.; Garrigós, M.C. Recent Trends in the Use of Pectin from Agro-Waste Residues as a Natural-Based Biopolymer for Food Packaging Applications. Materials 2020, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nuzzo, A.; Mazzei, P.; Drosos, M.; Piccolo, A. Novel Humo-Pectic Hydrogels for Controlled Release of Agroproducts. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 10079–10088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Aziz, G.H.A.; Ibrahim, A.S.; Fahmy, A.H. Using Environmentally Friendly Hydrogels to Alleviate the Negative Impact of Drought on Plant. Open J. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 111–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmoud, M.E.; Mohamed, A.K. Novel Derived Pectin Hydrogel from Mandarin Peel Based Metal-Organic Frameworks Composite for Enhanced Cr(VI) and Pb(II) Ions Removal. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 164, 920–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirsa, S.; Asadzadeh, F.; Karimi Sani, I. Synthesis of Magnetic Gluten/Pectin/Fe3O4 Nano-Hydrogel and Its Use to Reduce Environmental Pollutants from Lake Urmia Sediments. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2020, 30, 3188–3198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Song, J.; He, Q.; Wang, H.; Lyu, W.; Feng, H.; Xiong, W.; Guo, W.; Wu, J.; Chen, L. Novel Pectin Based Composite Hydrogel Derived from Grapefruit Peel for Enhanced Cu(II) Removal. J. Hazard. Mater. 2020, 384, 121445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Sabando, J.; Coin, F.; Melillo, J.H.; Goyanes, S.; Cerveny, S. A Review of Pectin-Based Material for Applications in Water Treatment. Materials 2023, 16, 2207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.-E.; Bejenaru, L.E.; Bejenaru, C.; Blendea, A.; Mogoşanu, G.D.; Biţă, A.; Boia, E.R. Advancements in Hydrogels: A Comprehensive Review of Natural and Synthetic Innovations for Biomedical Applications. Polymers 2025, 17, 2026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, H.; Wei, H.; Qi, Y.; Ding, S.; Li, H.; Si, S. Advances in Hybrid Hydrogel Design for Biomedical Applications: Innovations in Drug Delivery and Tissue Engineering for Gynecological Cancers. Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2025, 41, 115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, X.; Zhou, L. Progress, Challenge and Perspective of Hydrogels Application in Food: A Review. npj Sci. Food 2025, 9, 155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rumon, M.H.; Rahman, S.; Akib, A.A.; Sohag, S.; Rakib, R.A.; Khan, A.R.; Yesmin, F.; Shakil, M.S.; Rahman Khan, M.M. Progress in Hydrogel Toughening: Addressing Structural and Crosslinking Challenges for Biomedical Applications. Discov. Mater. 2025, 5, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, Y.; Wang, C.; Khalifa, I.; Zhu, Y.; Wang, Z.; Chen, H.; Liang, X.; Zhang, H.; Hu, L.; Yang, W. Pectin: A Review with Recent Advances in the Emerging Revolution and Multiscale Evaluation Approaches of Its Emulsifying Characteristics. Food Hydrocoll. 2024, 157, 110428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilson, N.W.; Botte, G.G. Novel Biopolymer Pectin-Based Hydrogel Electrolytes for Sustainable Energy Storage. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 7312–7326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günter, E.A.; Popeyko, O.V.; Shevchenko, O.G.; Vityazev, F.V. Modification of Texture and in Vitro Digestion of Pectin and κ-Carrageenan Food Hydrogels with Antioxidant Properties Using Plant Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 316, 144682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rubio-Martin del Campo, K.N.; Rivas-Gastelum, M.F.; Garcia-Amezquita, L.E.; Sepulveda-Villegas, M.; López-Mena, E.R.; Mejía-Méndez, J.L.; Sánchez-López, A.L. From Nature to Science: A Review of the Applications of Pectin-Based Hydrogels. Macromol 2025, 5, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040058

Rubio-Martin del Campo KN, Rivas-Gastelum MF, Garcia-Amezquita LE, Sepulveda-Villegas M, López-Mena ER, Mejía-Méndez JL, Sánchez-López AL. From Nature to Science: A Review of the Applications of Pectin-Based Hydrogels. Macromol. 2025; 5(4):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040058

Chicago/Turabian StyleRubio-Martin del Campo, Karla Nohemi, María Fernanda Rivas-Gastelum, Luis Eduardo Garcia-Amezquita, Maricruz Sepulveda-Villegas, Edgar R. López-Mena, Jorge L. Mejía-Méndez, and Angélica Lizeth Sánchez-López. 2025. "From Nature to Science: A Review of the Applications of Pectin-Based Hydrogels" Macromol 5, no. 4: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040058

APA StyleRubio-Martin del Campo, K. N., Rivas-Gastelum, M. F., Garcia-Amezquita, L. E., Sepulveda-Villegas, M., López-Mena, E. R., Mejía-Méndez, J. L., & Sánchez-López, A. L. (2025). From Nature to Science: A Review of the Applications of Pectin-Based Hydrogels. Macromol, 5(4), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/macromol5040058