Abstract

In this study, the corrosion behavior of pure aluminum in methyl esters with different degrees of unsaturation and chain lengths, as found in biodiesel, was investigated using electrochemical techniques. The methyl esters evaluated included methyl acrylate (C4H6O2) and methyl linoleate (C19H34O2), which were added to methyl propionate (C4H8O2) and methyl oleate (C19H36O2), respectively. The electrochemical techniques employed were electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) and electrochemical noise (EN), complemented by detailed scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analyses. The results indicated that both the corrosion rate and the susceptibility to localized corrosion, such as pitting, increased with higher degrees of unsaturation and longer alkyl chain lengths. The corrosion process remained under charge transfer control and was not directly influenced by these factors. However, the charge transfer resistance decreased with increasing unsaturation and chain length, consistent with the observed increase in corrosion rate.

1. Introduction

Biodiesel has gained considerable attention as an alternative to petroleum diesel because of its renewable nature, lower toxicity, reduced exhaust emissions, and enhanced physical and chemical properties compared to conventional diesel fuels [1,2,3,4]. The rapid depletion of fossil fuel resources has led to a growing demand for biodiesel, highlighting the importance of research in this area due to the non-renewable nature of traditional fuels [5]. Despite these advantages, biodiesel is not entirely suitable for direct use in diesel engines, as it exhibits several disadvantages when compared to petroleum diesel. One of the most significant limitations is its poor oxidative stability when exposed to atmospheric conditions [6,7]. The oxidation process results in the formation of highly volatile compounds such as ketones, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids, which can adversely affect diesel engine performance depending on the extent of oxidation. A high degree of unsaturation further increases the susceptibility of biodiesel to oxidative degradation [8,9,10]. Additionally, biodiesel exhibits a great corrosive behavior due to the presence of free fatty acids and moisture content [11,12,13]. Alves et al. [14] investigated the corrosion behavior of 316 stainless steel in biodiesel produced from soybean oil via two different processes: methanolysis and ethanolysis, yielding fatty acid methyl esters and fatty acid ethyl esters, respectively. The corrosion rate of stainless steel was low and comparable to that exhibited in both methyl and ethyl esters; however, the steel showed a slight susceptibility to pitting-type corrosion. In a separate study, Kugelmeier et al. [15] assessed the corrosion resistance of aluminum, copper, carbon steel, and 304 stainless steel in soybean biodiesel. Copper and carbon steel exhibited the highest corrosion rates, followed by stainless steel, whereas aluminum showed no evidence of corrosion. Kaul et al. [16] investigated the corrosion behavior of aluminum in various biodiesels derived from Jatropha curcas, Karanja, Mahua, and Salvadora. Their results showed that biodiesel produced from Jatropha curcas exhibited the highest corrosivity, while biodiesel obtained from Salvadora was the least aggressive. Likewise, different metallic materials may display distinct corrosion behaviors when exposed to the same biodiesel. For instance, in a study examining the corrosion of several metals in palm biodiesel, aluminum exhibited a lower corrosion rate compared to copper and brass [17]. In a similar study, Hu et al. [18] assessed the corrosion performance of common automotive metals, including aluminum (Al), copper (Cu), 304 stainless steel (304 SS), and 1018 carbon steel (1018 CS), in biodiesel produced from rapeseed oil and methanol. The authors reported that copper showed the highest corrosion rate, followed by 1018 CS, whereas 304 SS demonstrated the greatest resistance to corrosion. Despite its advantages over conventional diesel, biodiesel is considerably more prone to degradation, which often results in higher corrosivity than that of petroleum diesel [19,20]. Biodiesel degradation primarily occurs through auto-oxidation reactions, moisture uptake, and microbial activity during storage and use [21,22]. The extent of degradation may vary depending on the feedstock, due to differences in chemical composition, particularly in terms of the degree of unsaturation. The oxidation rate of biodiesel is influenced more strongly by the composition of its alkyl esters than by external factors such as temperature, exposure to air or light, and the presence of metals [23]. Lower oxidative stability is associated with a higher number of double bonds in the methyl esters. Furthermore, increasing the ester alkyl chain length promotes greater adsorption and aggregation on metal surfaces, thereby enhancing corrosive behavior [24]. In another study, Liu et al. [25] evaluated five imidazolium-based ionic liquids with different alkyl chain lengths (C8–C16) and demonstrated that the inhibition efficiency increased with increasing chain length, owing to enhanced adsorption and the formation of a protective film on Q235 steel. Similarly, Singh et al. [26] investigated the relationship between alkyl chain length and the corrosion inhibition efficiency of N-acylated chitosans on mild steel in an acidic medium, highlighting the importance of the interaction between the hydrophobic chain and the metal surface. Numin et al. [27] examined the effect of alkyl chain length (C10, C12, C14, C16, and C18) of a quaternary ammonium surfactant corrosion inhibitor on Fe (110) in acetic acid, and found that the most favorable adsorption occurred for the C12 chain. Zamindar et al. [28] presented a recent review on ionic liquid-based corrosion inhibitors, reporting that the inhibition properties depend on the length and nature of the alkyl group, which influences adsorption on metal surfaces such as steel. Similar findings were reported by Feng et al. [29], who observed that the inhibition efficiency of imidazolium-type ionic liquids increased with increasing alkyl chain length attached to the imidazolium ring.

As can be seen, all of these research studies have been conducted either on complex compounds such as biodiesel or corrosion inhibitors, including different alkyl esters with varying chain lengths and degrees of unsaturation. However, to evaluate two specific compounds rather than a complex biodiesel mixture, the objective of this study is to assess the influence of the alkyl chain length and degree of unsaturation on the corrosion behavior of pure aluminum. We have chosen Al because many automotive engine components made of aluminum—such as pistons, piston rings, cylinders, and transmission parts—are in contact with fuel, either petroleum diesel or biodiesel, and thus are attacked by the latter since it is more corrosive than the former.

2. Experimental Produce

2.1. Testing Material

Although pure aluminum is not commonly used in practical engineering applications, it was selected in this study to eliminate the influence of second phases, which are invariably present in aluminum alloys. It is well known that second phases can promote the detachment of protective films and induce micro-galvanic corrosion between the second phases and the aluminum matrix, leading to localized corrosion. These effects could obscure the intrinsic influence of alkyl chain length and degree of unsaturation on the corrosion behavior of pure aluminum to lead a basic understanding of the corrosion characteristics of this metal in biodiesel by avoiding complications imposed by alloying elements.

2.2. Testing Solution

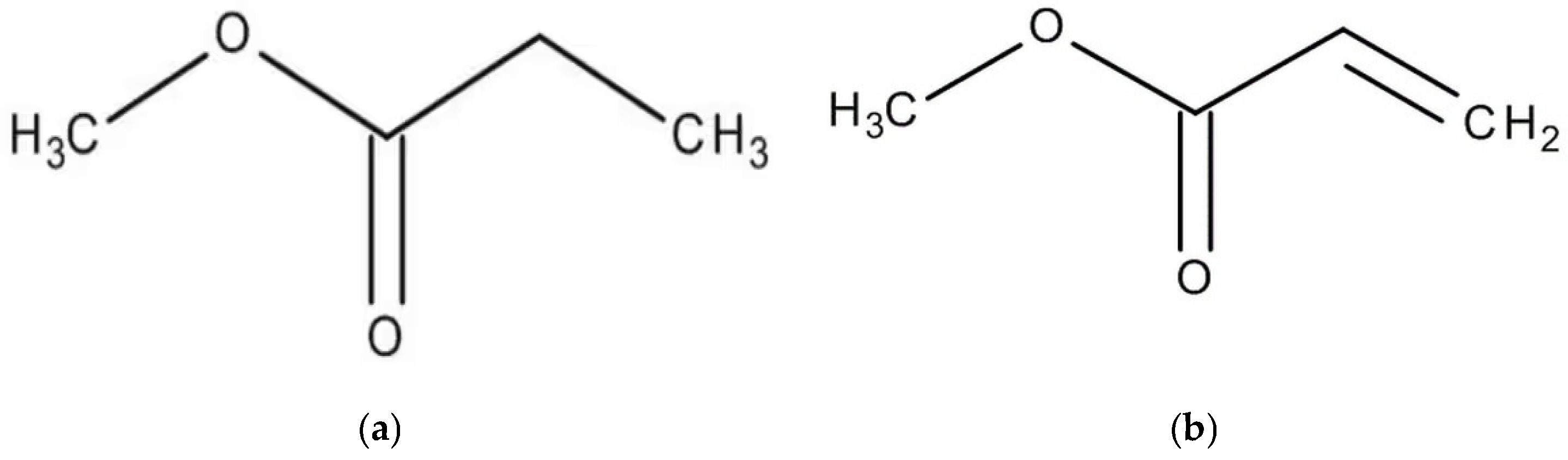

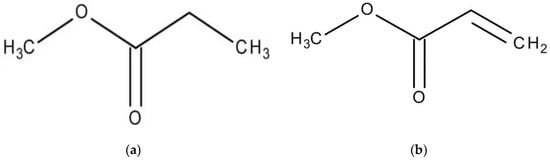

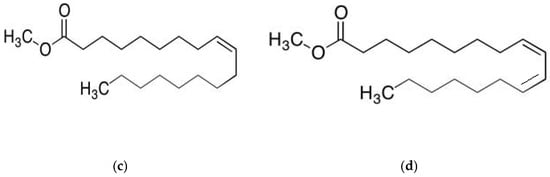

To evaluate the influence of alkyl chain length, two methyl esters with different chain lengths were selected: methyl propionate (C4H8O2) and methyl oleate (C19H36O2). In addition to this, to assess the effect of the degree of unsaturation, esters with identical carbon chain lengths but higher levels of unsaturation were also examined. Specifically, methyl acrylate (C4H6O2) and methyl linoleate (C19H34O2) were included at different concentrations and compared with methyl propionate and methyl oleate, respectively. These reagents were obtained from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). The chemical structures of these compounds are presented in Figure 1. Although methyl propionate and methyl acrylate contain the same number of carbon atoms, the former has a lower degree of unsaturation than the latter. Similarly, methyl oleate and methyl linoleate possess the same carbon chain length but differ in their degree of unsaturation, with methyl linoleate exhibiting a higher number of double bonds. Thus, two solutions were used in this research work: one solution included pure methyl propionate containing different concentrations, including 0, 10, 50 and 100 μM, of methyl oleate; another solution consisted of methyl acrylate with different concentrations, i.e., 0, 10, 50 and 100 μM of methyl linoleate.

Figure 1.

Chemical structure of (a) methyl propionate, (b) methyl acrylate, (c) methyl oleate and (d) methyl linoleate.

2.3. Electrochemical Measurements

Electrochemical techniques, namely electrochemical noise (EN) analysis and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), were employed in this study. EN measurements were conducted using a zero-resistance ammeter (ZRA) from ACM Instruments (Grange-over-Sands, UK) in a three-electrode electrochemical cell, where graphite served as the auxiliary electrode, a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode was used as the reference, and aluminum (Al) bars acted as the working electrodes. Although the cell was not open to the air, the entry of oxygen was not avoided. Similarly, the tests were carried out during the rainy season, so the entry of humidity was not avoided either. The Al specimens were encapsulated in a polymeric resin, exposing a surface area of 0.32 cm2. Prior to immersion in the corrosive solution, metal surfaces were mirror-polished, washed with water, and blown with warm air. Before starting the tests, the free corrosion potential value, Ecorr, was allowed to reach a steady state value during 30 min. EN measurements of both potential and current were recorded weekly in blocks of 1024 data points at a sampling rate of 1 read/s. Current noise measurements were obtained using a second, nominally identical working electrode. Signal trends were removed by applying a least-squares fitting procedure. The noise resistance parameter (Rn) was calculated as the ratio of the standard deviation of the potential noise (σv) to that of the current noise (σi). Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements were performed weekly using a Gamry PCI4-300 potentiostat/galvanostat (Warminster, PA, USA) over a frequency range of 0.05–20,000 Hz, with a perturbation amplitude of 30 mV applied around the free corrosion potential. Tests lasted 1200 h as recommended in the literature [17,18] and repeated three times. After testing, the corroded specimens were examined using a low-vacuum LEO scanning electron microscope (SEM) (LEO Electron Microscope Inc., Thornwood, NY, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. EIS Measurements

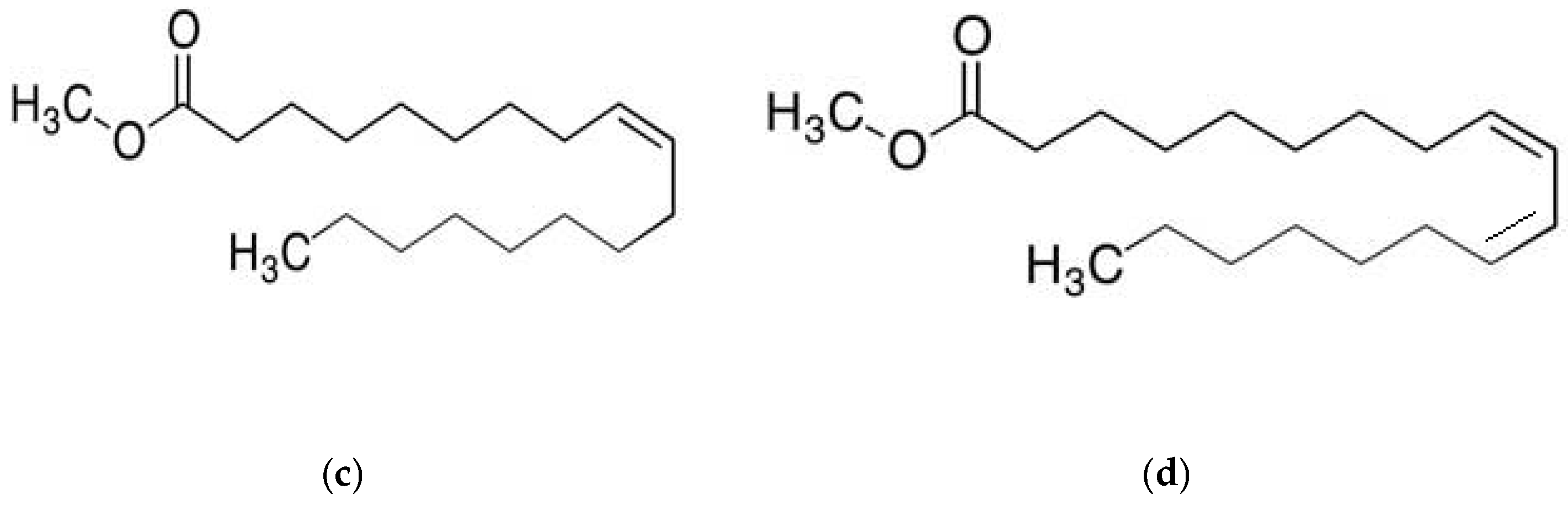

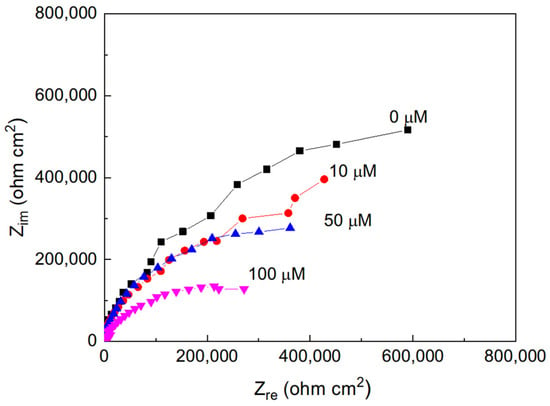

Nyquist plots for pure aluminum immersed in methyl propionate containing different concentrations of methyl acrylate are presented in Figure 2. As shown, the impedance spectra consist of a single depressed capacitive semicircle whose center lies on the real axis, indicating that the corrosion process is predominantly controlled by charge transfer across the electrochemical double layer. With increasing methyl acrylate concentration, a progressive decrease in the diameter of the semicircle is observed. The diameter of the capacitive loop corresponds to the charge transfer resistance (Rct), which is equivalent to the polarization resistance (Rp) and is inversely proportional to the corrosion current density (Icorr). Therefore, the reduction in Rct with increasing methyl acrylate content reflects an enhancement in the corrosion rate, indicating that a higher degree of unsaturation increases the corrosive nature of the medium. Thus, with the addition of methyl acrylate, which has a higher number of double bonds than that of methyl propionate, the corrosion rate of Al increases, which is in agreement with the results previously published [20,21,22,23,24].

Figure 2.

Nyquist plots for Al in methyl propionate with the addition of methyl acrylate at different concentrations.

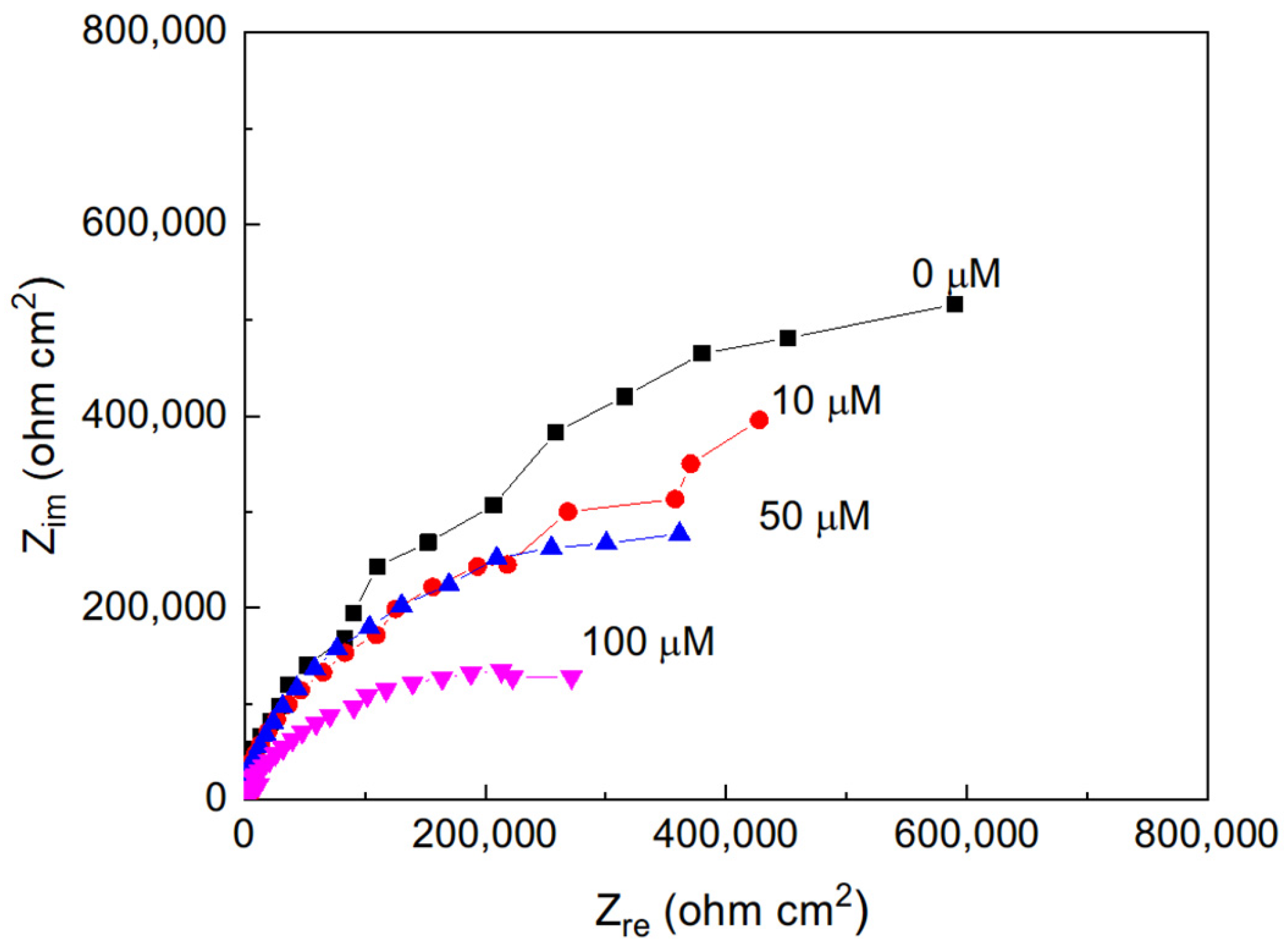

The effect of the addition of different concentrations of methyl linoleate to methyl oleate on the Nyquist plots for Al, displayed a similar trend to that observed for aluminum immersed in methyl oleate with varying concentrations of methyl linoleate (Figure 3), where the impedance response also exhibits capacitive semicircles centered on the real axis. The semicircle diameter decreased with an increase in the methyl linoleate concentration, indicating; thus, an increase in the Al corrosion rate.

Figure 3.

Nyquist plots for Al in methyl oleate with the addition of different concentrations of methyl linoleate.

The shape of the semicircles was not altered in this case, indicating that the corrosion process is governed by charge transfer, showing that the corrosion process did not change with the length of the alkyl esters. Thus, by increasing either the alkyl chain length or the number of double bonds, the corrosion rate of Al was increased. Similar behavior has been previously reported for pure aluminum exposed to palm oil biodiesel [30]. Vergara-Juarez et al. [31] evaluated Cu in similar methyl Esther, Methyl Hexanoate (MH) and Methyl Hexanoate +25% Methyl Trans-3-Hexenoate (MT3H) at 145 and 158 °C during 1000 h. Nyquist diagrams in both cases described one capacitive semicircle at high and intermediate frequency values, followed by a second capacitive semicircle at the lowest frequencies [31]. The total impedance for the tests in MH had values of 100,000 ohm cm2 and decreased with the addition of MT3H down to 80,000 ohm cm2. These values are more or less within the same order of magnitude as the ones obtained in the present work.

In general, the semicircle diameters obtained for aluminum immersed in methyl oleate containing varying concentrations of methyl linoleate are smaller than those observed for aluminum in methyl propionate with added methyl acrylate. The increase in the corrosion rate of metals exposed to compounds containing double bonds has been attributed to the higher reactivity of π-electrons in unsaturated bonds (C=C, C=O, etc.) compared to σ-bonds. These π-electrons are more susceptible to attack by oxygen, acids, or metal surfaces, increasing the likelihood of reactions that destabilize protective oxide films on metals [32,33].

In addition, double bonds and conjugated systems interact strongly with metal d-orbitals, enabling their adsorption onto metal surfaces and, in some cases, the formation of unstable surface complexes. Such interactions can disrupt protective passive layers and, when the adsorbed film is non-protective, lead to an increase in corrosion. Furthermore, unsaturated molecules can promote cathodic reactions by acting as electron acceptors and depolarizers in electrochemical cells. This behavior accelerates cathodic processes such as oxygen reduction, thereby increasing the overall corrosion rate [34,35,36].

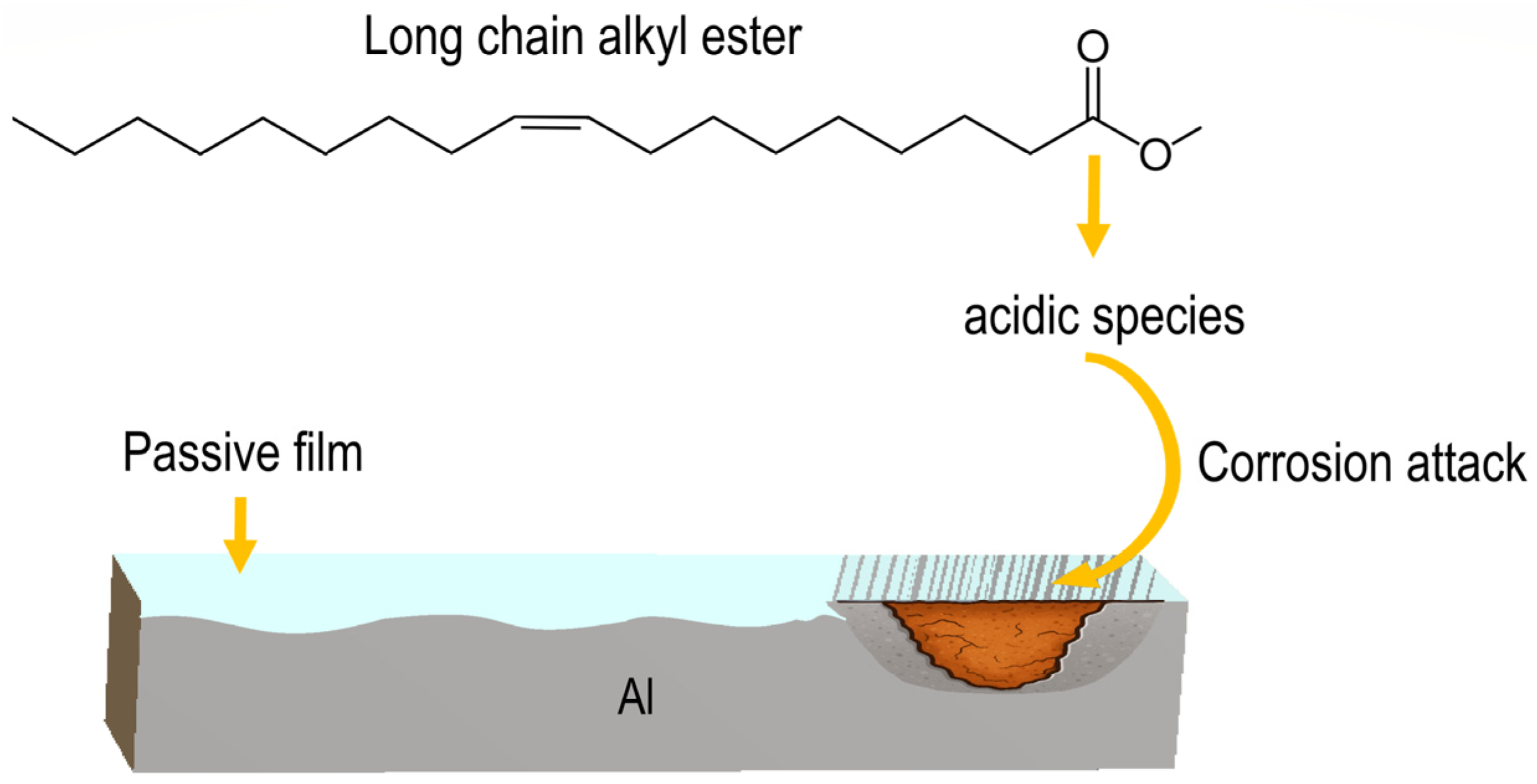

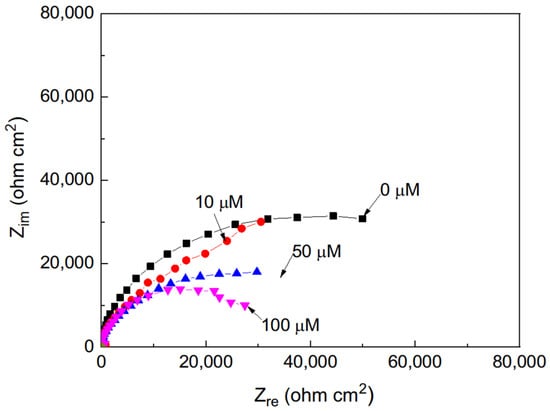

On the other hand, longer chains increase adsorption and degradation potential, strongly promoting oxidation, acid formation, and metal corrosion. They exhibit stronger adsorption on metal surfaces (not always protective) due to greater van der Waals interactions and higher surface affinity [26]. If the adsorbed film is unstable, discontinuous, or reactive, it can disrupt passive layers and create localized corrosion sites, thereby promoting localized forms of corrosion such as pitting. However, the main reason why longer-chain compounds tend to be more corrosive is related to oxidation, acid formation, and surface interactions [27]. These compounds readily oxidize and form acidic species by reacting with oxygen to produce peroxides, aldehydes, and carboxylic acids, which lead to corrosive attack as illustrated in Figure 4. When long-chain molecules degrade, they break into multiple smaller acidic fragments that accumulate in the solution, making the environment more aggressive [31].

Figure 4.

Scheme showing how the degradation of alkyl esters produces acidic species that attacks Al.

Closely related to this is the effect of oxygen, which initiates autoxidation reactions, leading to the formation of peroxides and hydroperoxides, aldehydes, ketones, short-chain organic acids, and polymerized oxidation products. These compounds increase the acidity, polarity, and overall aggressiveness of the medium, thereby enhancing its corrosivity toward metals such as aluminum. When water is present—as was the case in this study due to humidity from rainfall—it increases the electrical conductivity of the ester phase, providing an electrolytic medium that enables anodic and cathodic reactions and facilitates metal dissolution. In addition, water promotes the hydrolysis of fatty acid methyl esters, producing fatty acids and methanol. The resulting free fatty acids further increase acidity and corrosiveness, particularly toward steel, copper, and aluminum.

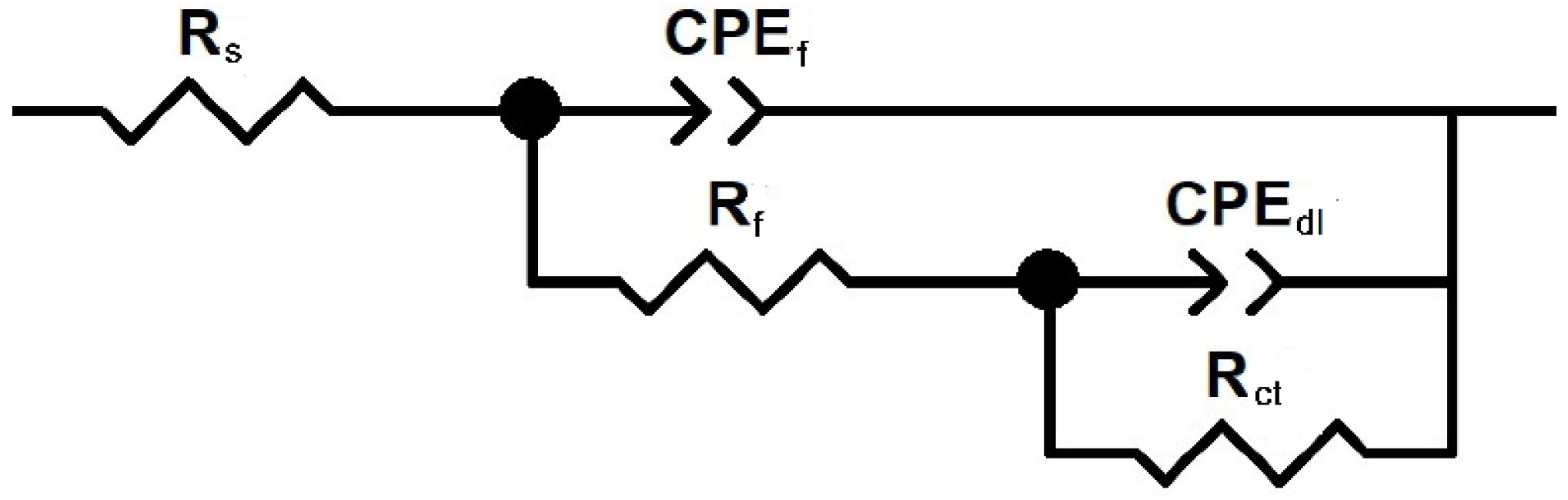

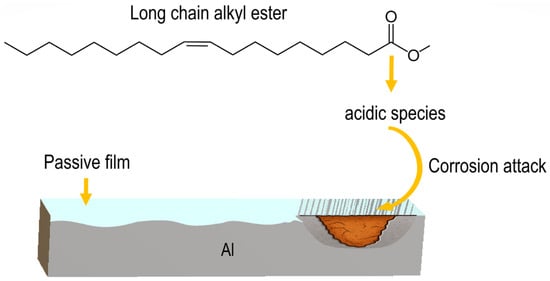

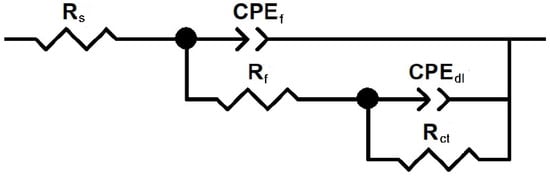

The EIS data were interpreted using equivalent electrical circuits composed of resistive and capacitive elements, as illustrated in Figure 5. In these circuits, the solution resistance is denoted by Rs, the charge transfer resistance by Rct, and the double-layer capacitance by Cdl. The resistance and capacitance associated with any film formed on the metal surface are represented by Rf and Cf, respectively [31]. To account for surface heterogeneities and deviations from ideal capacitive behavior, a constant phase element (CPE) was introduced in place of an ideal capacitor. The impedance of the CPE is expressed as:

where Y is a proportionality constant, i is √−1, ω = 2πf is the angular frequency, f is the frequency, and n is a parameter related to surface characteristics such as roughness [31]. The fitted EIS parameters corresponding to the first and last days of exposure to biodiesel are summarized in Table 1.

ZCPE = Y−1 (iω)−n

Figure 5.

Electric circuit used to fit EIS data.

Table 1.

Electrochemical parameters used to fit EIS data.

Table 1 shows that Rs has high values, which is due to their low conductivity, similar to those reported by Vergara-Juarez et al. [31] for Cu in methyl hexanoate (MH) and methyl hexanoate +25% methyl trans-3-hexenoate, with values of 601 and 435 ohm cm2, respectively. An important observation is that, regardless of the ester’s chemical composition, the resistance of the corrosion products (Rf) is substantially higher than the charge transfer resistance (Rct), indicating that the protective behavior of the metal is primarily governed by the film formed by these corrosion products. The Rct values decrease with the addition of either methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate, reflecting an increase in the corrosion rate. Vergara-Juarez et al. [31] reported Rct values of 5.1 and 2.7 × 105 ohm cm2 and 601 ohm cm2, one order of magnitude lower than the ones reported in this work, whereas the Rf values they reported were around 2.4 × 104, one order of magnitude lower than the ones reported in Table 1. Concurrently, the CPEdl values increase with increasing concentrations of methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate. This can be explained by considering that capacitance is proportional to the product of the film dielectric constant and the vacuum permittivity, and inversely proportional to the double electrochemical layer thickness [32]. Therefore, the increase in capacitance (or CPEdl) may result from either an increase in the dielectric constant or a decrease in the double electrochemical layer thickness. At low concentrations of methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate, where the corrosion rate is minimal, the metal surface remains relatively smooth, and the CPE exponent (nf) is close to 1.0. As the concentration of these esters—and thus the corrosion rate—increases, the metal surface becomes rougher, causing nf to decrease toward a value of approximately 0.5.

If we take the added alkyl esters, i.e., methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate, as a corrosion inhibitor, a parameter similar to the inhibitor efficiency, called I.E., which measures the Rct value for methyl propionate and methyl oleate, has been reduced, and can be calculated as follows:

where Rct1 is the Rct value obtained for Al immersed either in methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate, whereas Rct2 is the Rct value for Al immersed with the additions of either methyl propionate or methyl oleate. Table 1 clearly shows that both methyl propionate and methyl oleate reduced the Rct values obtained for Al immersed in methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate, with a more pronounced effect of the former.

I.E. = (Rct1 − Rct2)/Rct1 × 100

In order to have more quantitative results, from Nyquist diagrams, we obtained the polarization resistance value, Rp, as:

and used the Stearn-Geary equation to calculate the corrosion current density velu, Icorr:

where B is the Stern-Geary constant, normally 52 mV. To calculate the corrosion rate, C.R. in mm/y, we used the following relationship:

where EW and ρ are the equivalent weight and density for Al. Replacing Icorr from Equation (3), we can obtain:

Rp = Rs + Rct + Rf

Icorr = B/Rp

C.R. = (0.00327 IcorrEW)/ρ

C.R. = (0.00327 BEW)/ρRp

Thus, by using the EW and ρ for Al, the Rp and calculated corrosion rate, C.R. values are reported in Table 2. Since the Rp values are very high due to the low conductivity of methyl esters used, the C.R. values are very low as compared to those reported in the literature for pure Al in different biodiesels, which fluctuated between 0.04 and 3 mm/y. However, it can be seen that the addition of either compounds with unsaturation or longer alkyl chain length increases the corrosion rate values.

Table 2.

Corrosion rates, C.R., for Al in presence of methyl propionate + methyl acrylate and methyl oleate + methyl linoleate.

3.2. EN Measurements

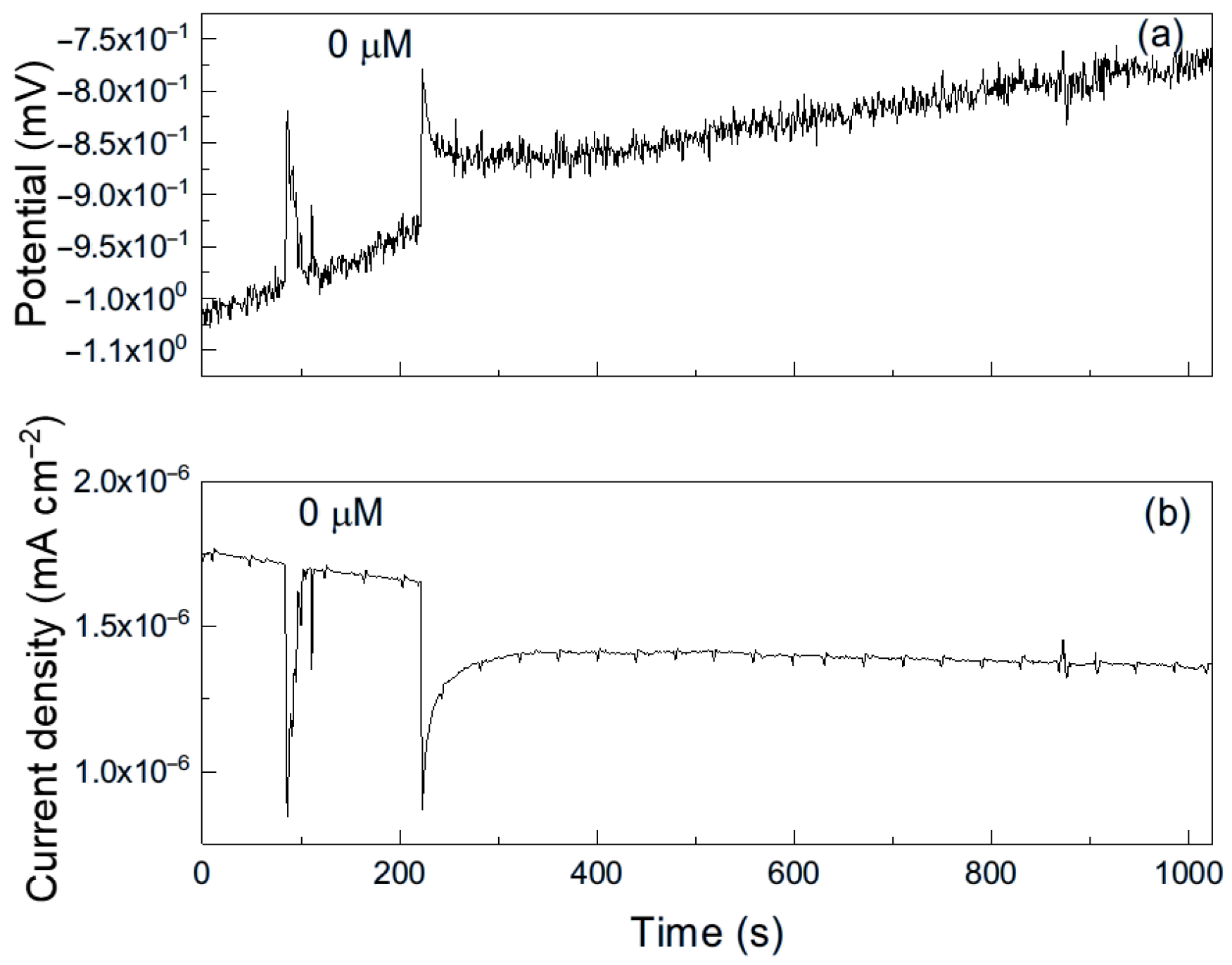

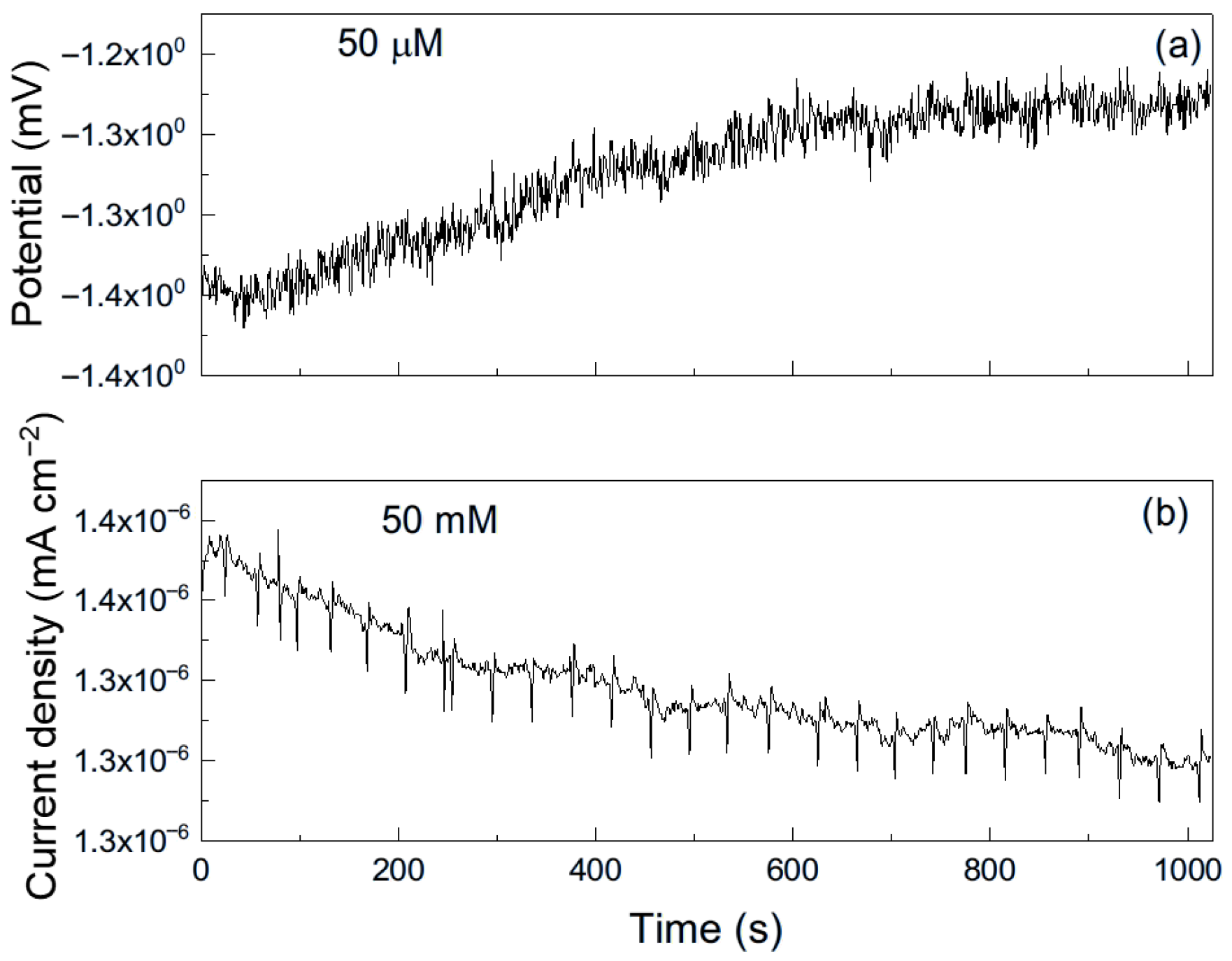

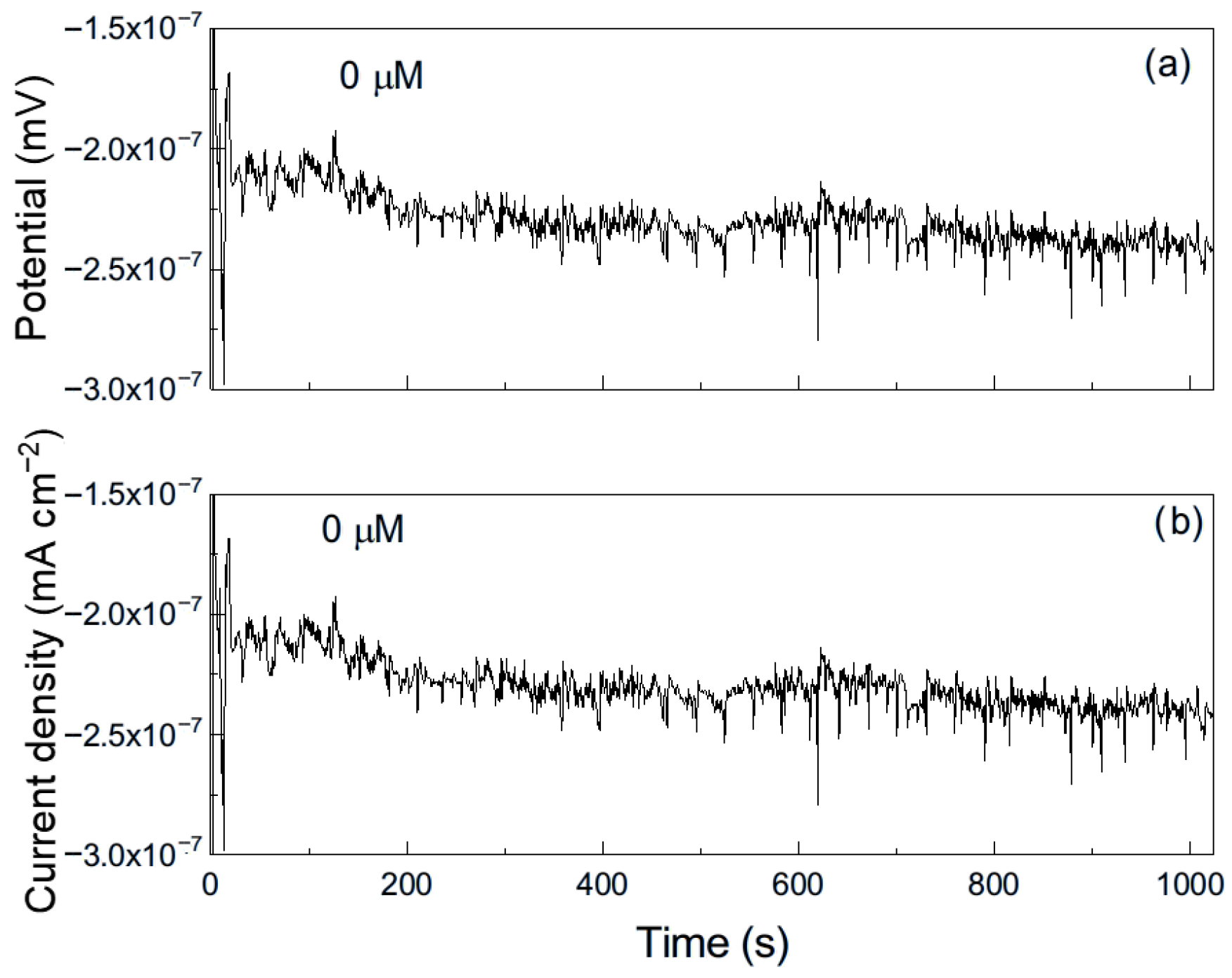

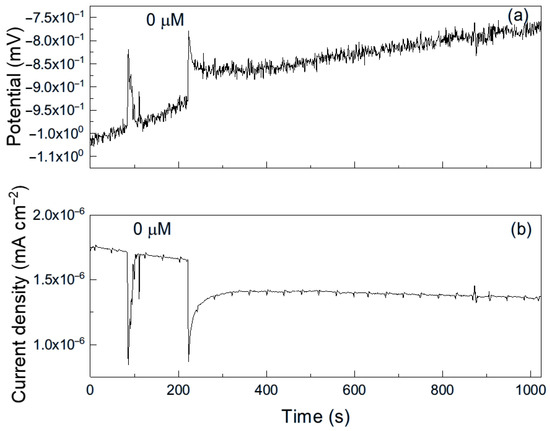

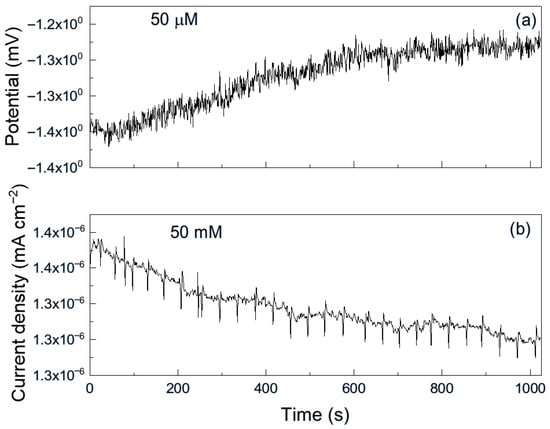

As an example, Figure 6 shows a representative time series of current and potential noise for aluminum exposed to methyl propionate. The data reveal transients of low intensity and high frequency, combined with less frequent transients of higher intensity, which are indicative of the rupture and reformation of a protective film or metastable pitting-type corrosion [33]. When 50 μM of methyl acrylate was added (Figure 7), both the intensity and frequency of the transients increased, suggesting more frequent film rupture and a higher susceptibility of the metal to localized corrosion, such as pitting. These transients result from the cyclical rupture and reformation of protective films on the metal surface. As established above, double bonds and conjugated systems interact strongly with metal d-orbitals, enabling their adsorption onto metal surfaces and, in some cases, the formation of unstable surface complexes. Such interactions can disrupt protective layers and, thus, leave those sites unprotected, giving rise to an increase in the localized corrosion rate, and, therefore, in the current. When the film is repaired and formed again, the current recovers its original value as observed in Figure 7b.

Figure 6.

Noise time series in (a) potential and in (b) current for Al immersed in pure methyl propionate.

Figure 7.

Noise time series in (a) potential and in (b) current for Al immersed in methyl propionate + 50 μM methyl acrylate.

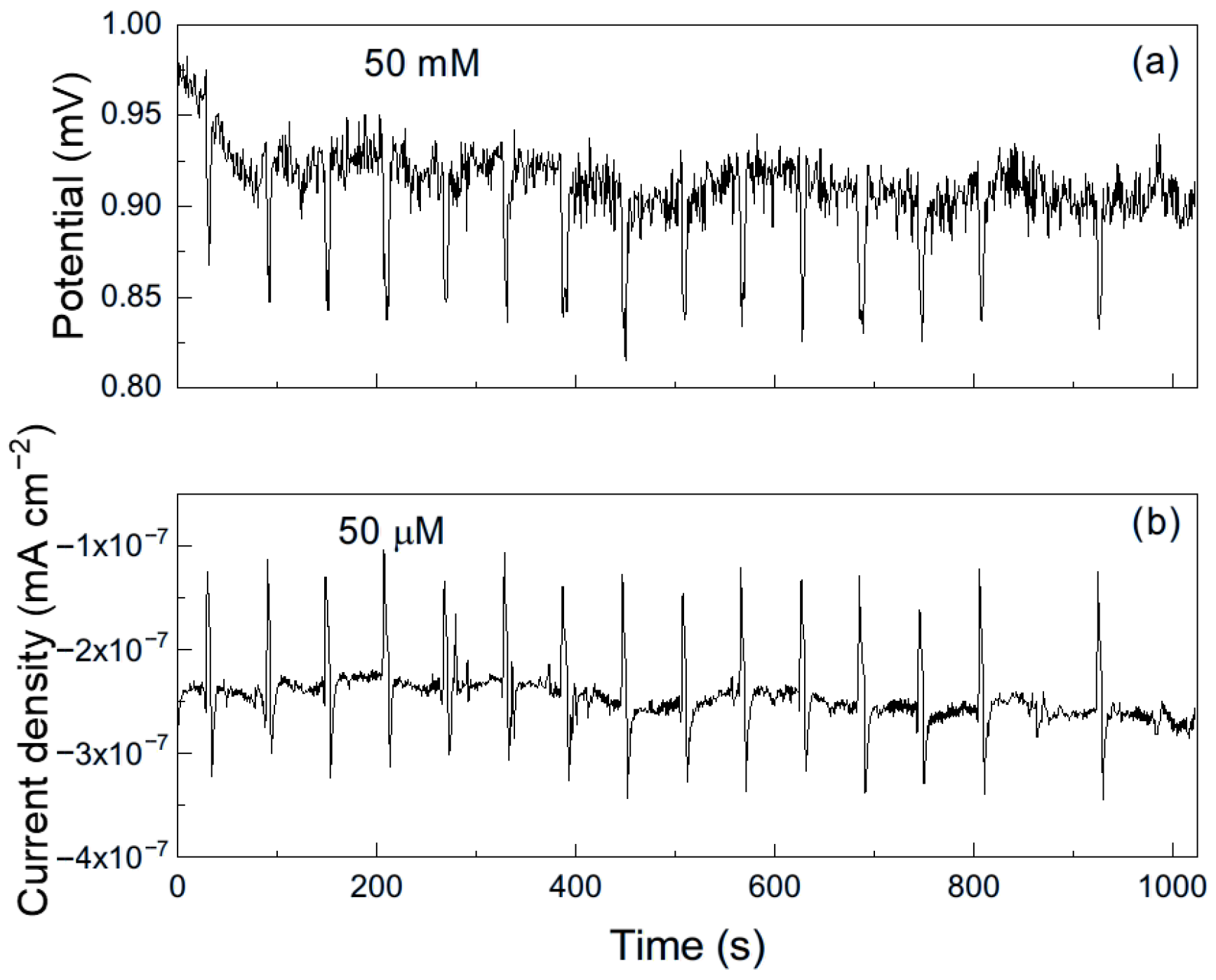

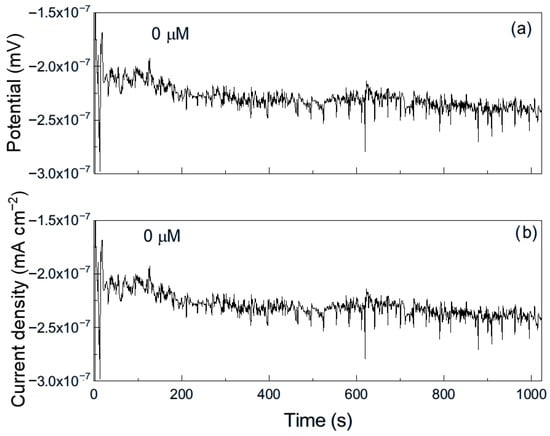

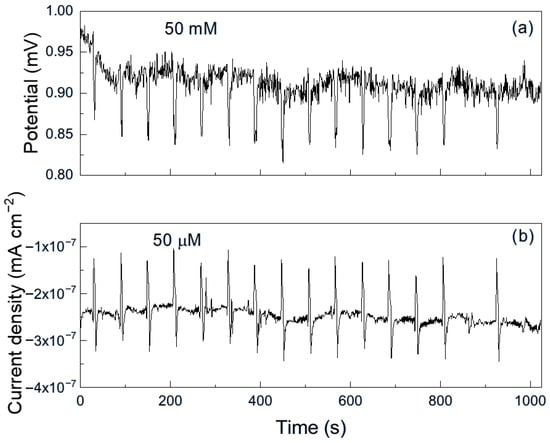

For aluminum immersed in pure methyl oleate (Figure 8), the time series for both potential and current exhibit predominantly low-intensity, high-frequency transients, indicative of uniform corrosion, along with occasional higher-intensity, lower-frequency transients, corresponding to localized corrosion events. However, upon the addition of 50 μM methyl linoleate (Figure 9), the time series displays highly periodic transients of greater intensity, reflecting repeated rupture and reformation of the protective film. This behavior indicates that aluminum is highly susceptible to localized corrosion, such as pitting, under these conditions [33]. As explained above, long alkyl esters or the presence of unsaturations exhibit stronger adsorption on metal surfaces (not always protective) due to greater van der Waals interactions, higher reactivity of π-electrons in unsaturated bonds and higher surface affinity [26], enabling their adsorption onto metal surfaces and, in some cases, the formation of unstable surface complexes. Such interactions can disrupt protective passive layers and, when the adsorbed film is non-protective, lead to an increase in corrosion. If the adsorbed film is unstable, discontinuous, or reactive, it can disrupt passive layers and create localized corrosion sites, thereby promoting localized forms of corrosion such as pitting.

Figure 8.

Noise time series in (a) potential and in (b) current for Al immersed in pure methyl oleate.

Figure 9.

Noise time series in (a) potential and in (b) current for Al immersed in methyl oleate + 50 μM methyl linoleate.

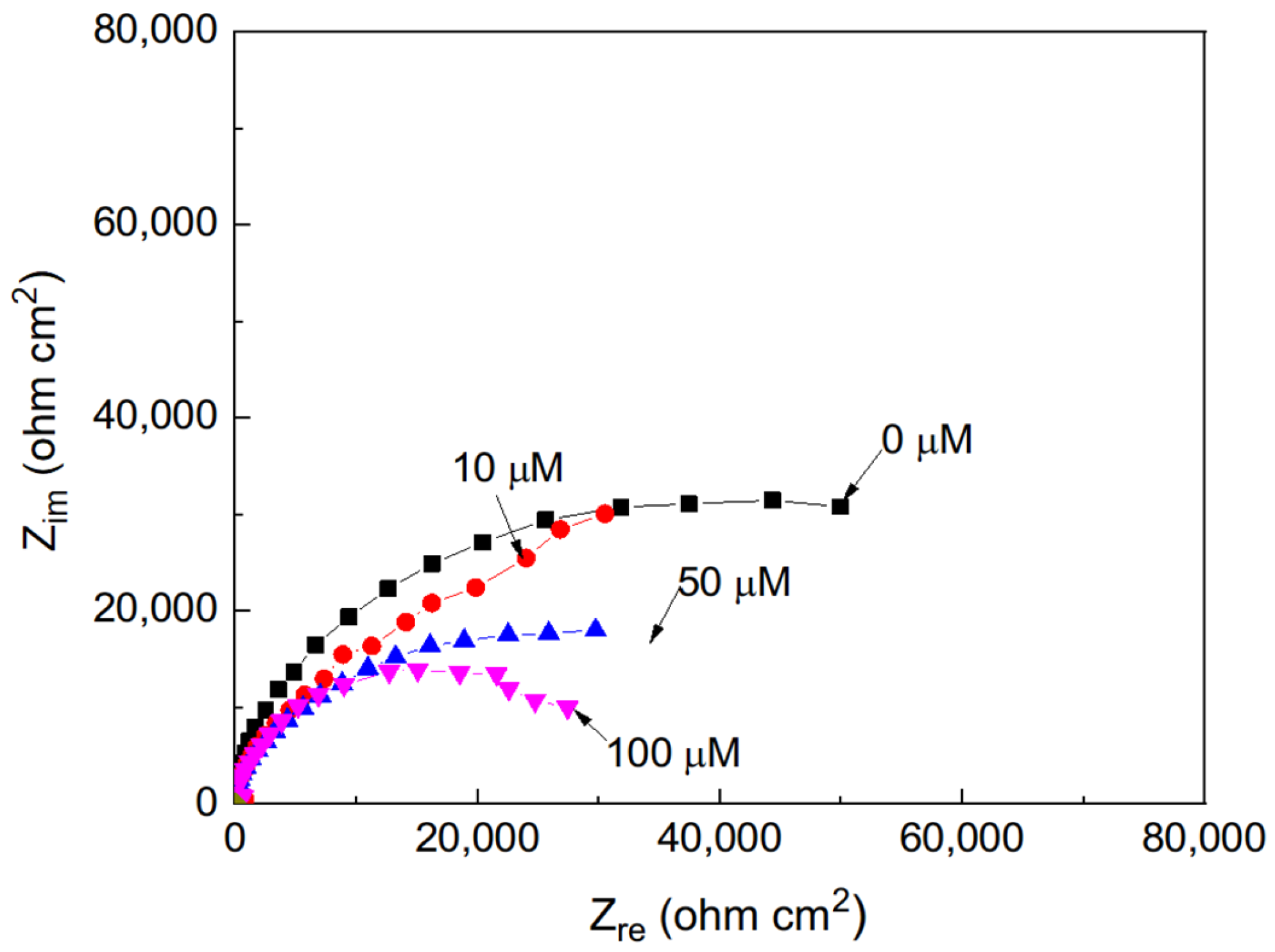

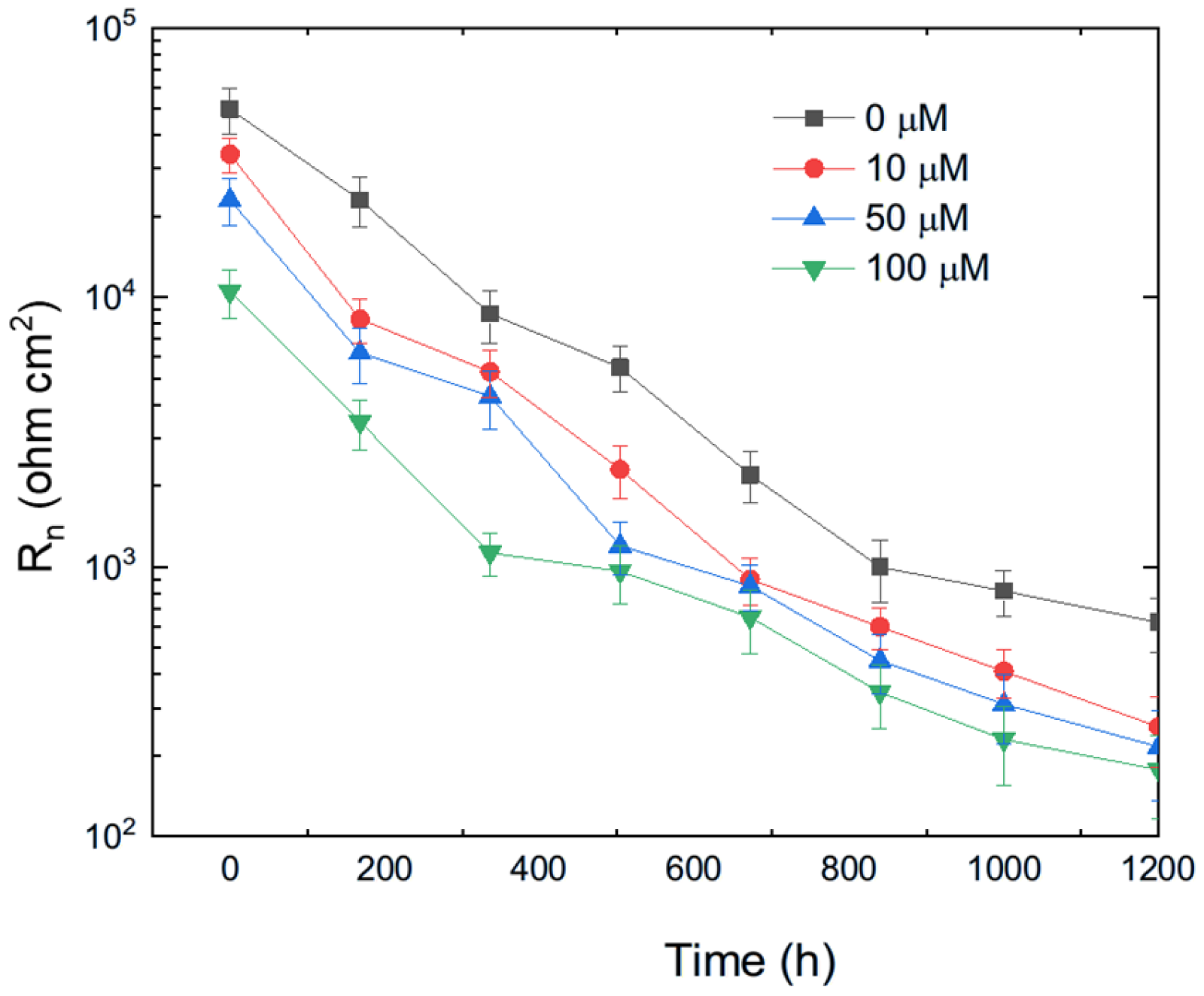

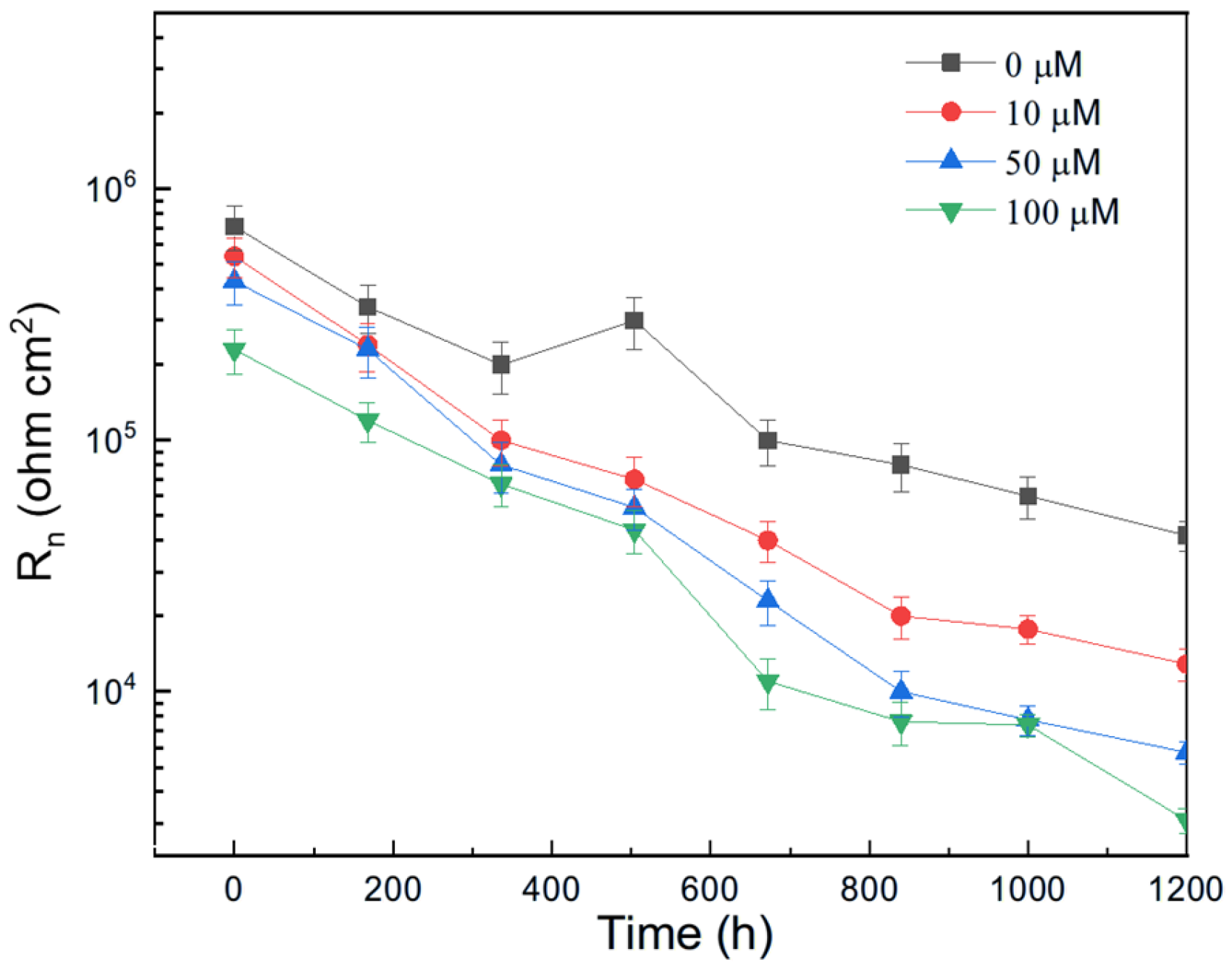

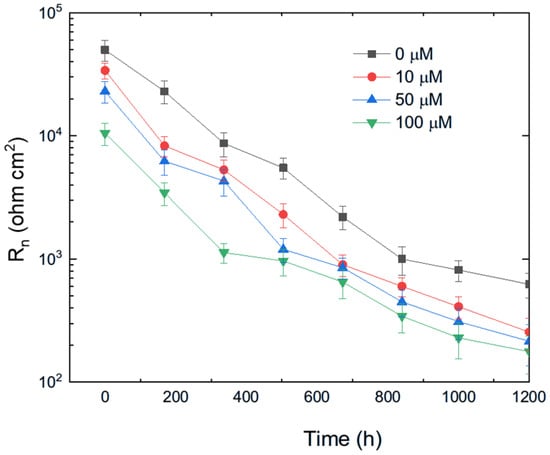

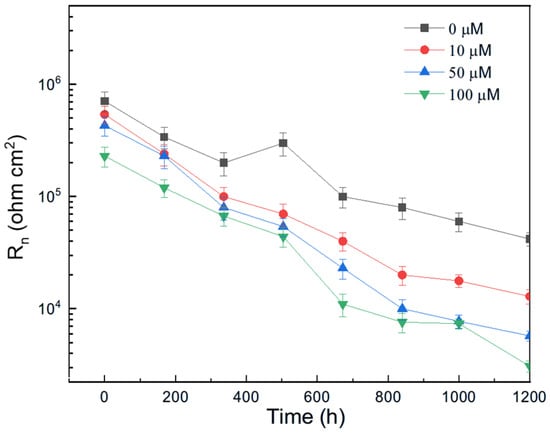

The variation in Rn for pure aluminum immersed in methyl propionate with different concentrations of methyl acrylate is shown in Figure 10, while the effect of adding methyl linoleate to methyl oleate is presented in Figure 11. These figures show that the addition of either methyl acrylate or methyl linoleate reduces the Rn value, and increasing their concentration leads to a further decrease, corresponding to an increase in the corrosion current density (Icorr). Additionally, the presence of a longer alkyl chain also lowers the Rn value. It can be noticed that the Rn values for Al immersed in methyl propionate + methyl acrylate are higher than those in methyl oleate + methyl linoleate, and that, in general terms, an increase in either the degree of unsaturation or the alkyl chain length brings a decrease in the Rn value, indicating an enhancement in the corrosion rate of aluminum.

Figure 10.

Effect of the addition of methyl acrylate to methyl propionate on the variation in the Rn value with time for Al.

Figure 11.

Effect of the addition of methyl linoleate to methyl oleate on the variation in the Rn value with time for Al.

3.3. Corroded Surface Analysis

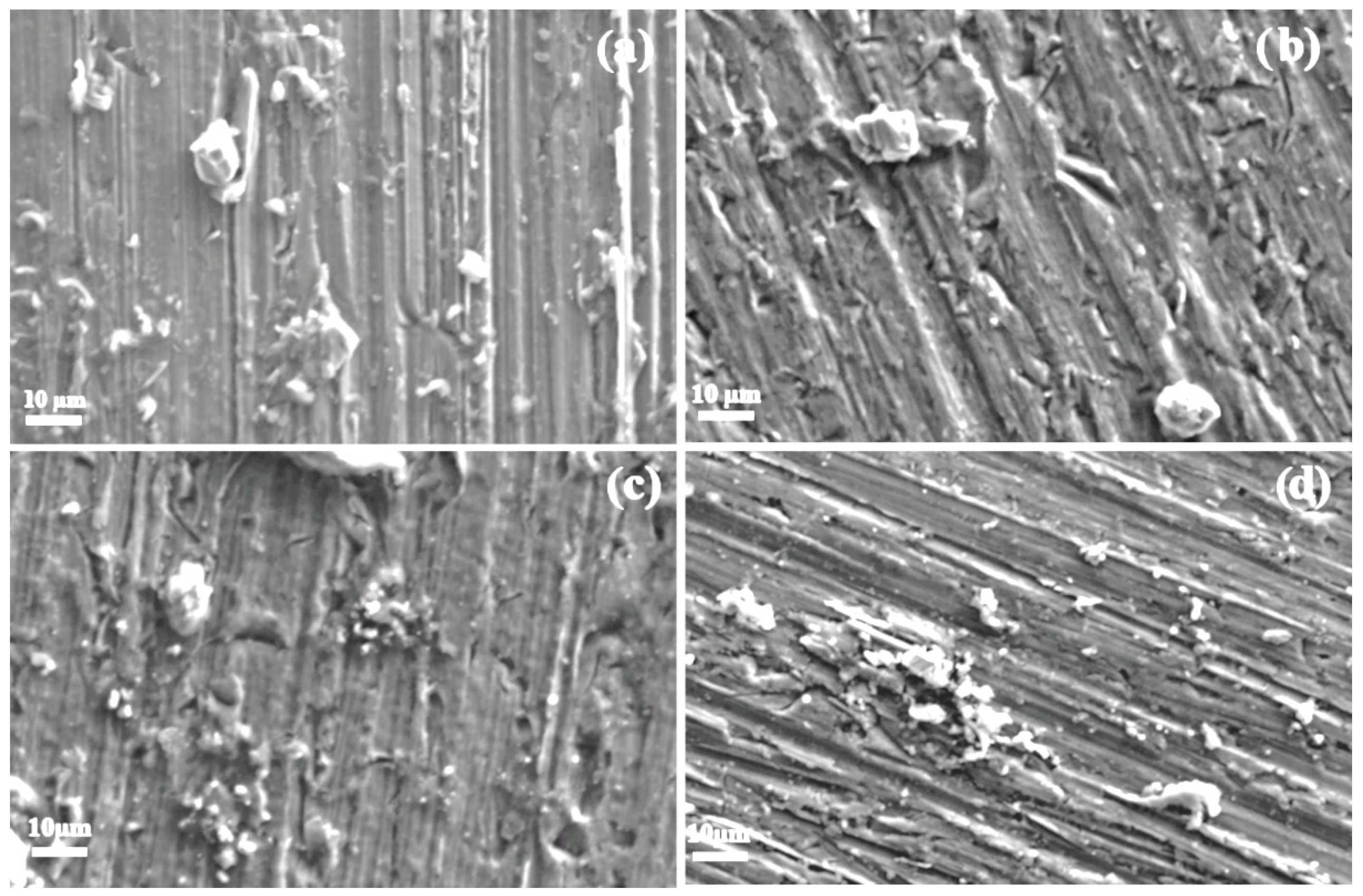

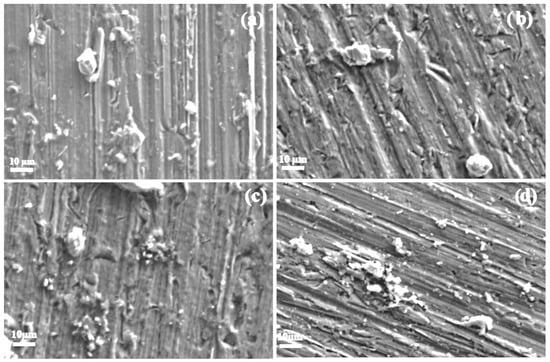

SEM micrographs of aluminum specimens corroded in various methyl ester solutions are presented in Figure 12 and Figure 13. Figure 12 shows specimens exposed to methyl propionate with different concentrations of methyl acrylate. For the specimen immersed in pure methyl propionate (Figure 12a), no visible damage is observed on the metal surface, with only minor corrosion products present, consistent with the current and potential noise time series shown in Figure 6. When 10 μM of methyl acrylate was added (Figure 12b), a few small pits with diameters below 10 μm appeared, along with some corrosion products. As the concentration of methyl acrylate increases (Figure 12c,d), both the number of pits and the amount of corrosion products covering the surface increase, in agreement with the trends observed in the noise time series in Figure 7, indicating enhanced corrosiveness of the solution.

Figure 12.

SEM micrographs of Al immersed in methyl propionate with the addition of (a) 0, (b) 10, (c) 50 and (d) 100 μM methyl acrylate.

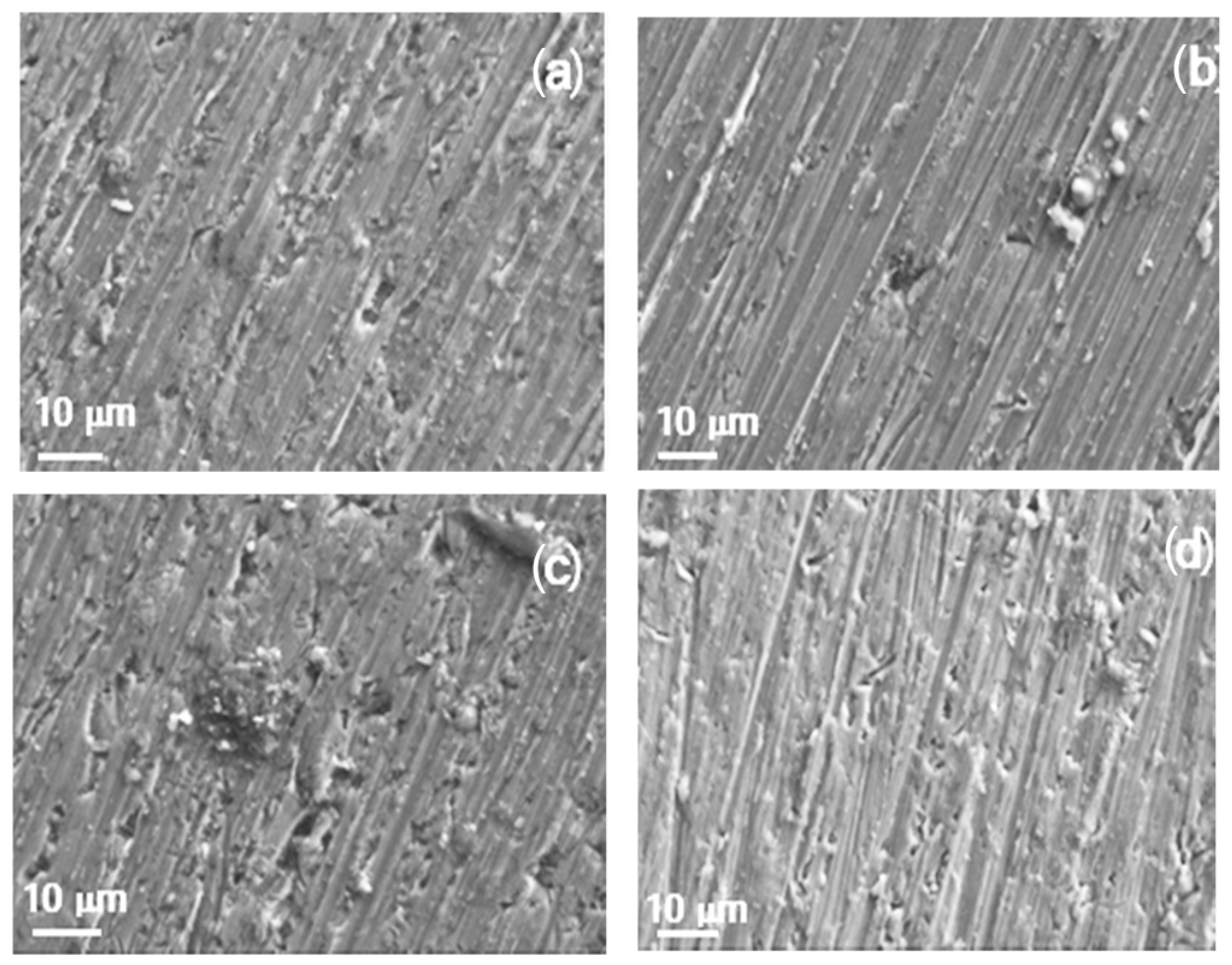

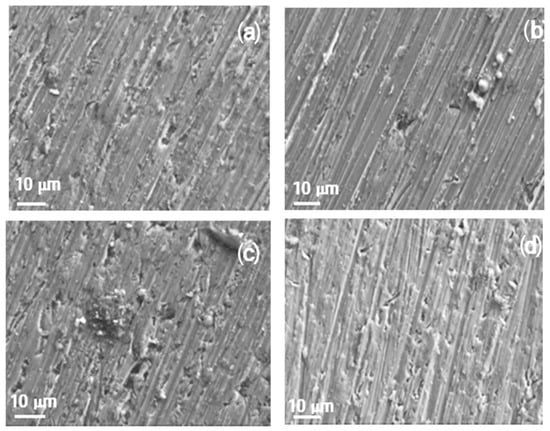

Figure 13.

SEM micrographs of Al immersed in methyl oleate with the addition of (a) 0, (b) 10, (c) 50 and (d) 100 μM methyl linoleate.

For specimens corroded in pure methyl oleate or methyl oleate containing 10 μM methyl linoleate (Figure 13a,b), a few small pits are observed on the aluminum surface alongside corrosion products. However, at higher concentrations of methyl linoleate (Figure 13c,d), the number of pits increases significantly, consistent with the time series shown in Figure 9. By comparing Figure 12 and Figure 13, it is evident that an increase in alkyl chain length leads to a higher pit density. For aluminum exposed to pure methyl propionate (Figure 12a), no pits were observed on the metal surface. In contrast, aluminum exposed to pure methyl oleate (Figure 13a) showed clear evidence of pitting. Likewise, samples exposed to compounds with longer alkyl chains, namely methyl oleate containing methyl linoleate (Figure 13b–d), exhibited a greater number of pits than those exposed to shorter alkyl chains, such as methyl propionate with methyl acrylate (Figure 12b–d). In addition to this, the pit size for specimens exposed to short alkyl length measures around 2 μm diameter and with lower density as compared with those present in specimens exposed to long alkyl chain length, where a higher number of pits with a diameter around 5–8 μm.

Thus, it is evident that an increase in both the degree of unsaturation and a longer alkyl chain length enhances the susceptibility of pure aluminum to localized corrosion in the presence of methyl esters.

4. Conclusions

A study was conducted to evaluate the effect of the degree of unsaturation and the alkyl chain length of methyl esters on the corrosion behavior of pure aluminum. The EIS results indicated that both the charge transfer resistance and the resistance of the corrosion product film decreased with increasing unsaturation and chain length. The corrosion process remained under charge transfer control and was not directly influenced by these factors. EN measurements revealed that the susceptibility to localized corrosion, such as pitting, increased with higher unsaturation and longer chain lengths, which was further confirmed by the analysis of corroded specimens. Similarly, the noise resistance, which is equivalent to the charge transfer resistance, decreased with increasing unsaturation and chain length, reflecting an increase in the corrosion rate of aluminum.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, O.E.C.-M. and A.K.G.-L.; software and validation I.R.-C. and A.M.R.-A.; formal analysis and investigation R.L.-C. and J.P.-C.; writing—original draft preparation and project administration, J.G.G.-R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by CONAHCYT, grant number 549489.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Jose Juan Ramos-Hernandez and Maura Casales Diaz for their SEM work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yang, G.; Yu, J. Advancements in Basic Zeolites for Biodiesel Production via Transesterification. Chemistry 2023, 5, 438–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gülüm, M.; Bilgin, A. A comprehensive study on measurement and prediction of viscosity of biodiesel-diesel-alcohol ternary blends. Energy 2018, 148, 341–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mosarof, M.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Alabdulkarem, A.; Habibullah, M.; Arslan, A. Assessment of friction and wear characteristics of Calophyllum inophyllum and palm biodiesel. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 83, 470–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelazayem, O.; El-Gendy, N.; Abdel-Rehim, A.A.; Ashour, F.; Sadek, M.A. Biodiesel production from castor oil in Egypt: Process optimisation, kinetic study, diesel engine performance and exhaust emissions analysis. Energy 2018, 157, 843–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Yuan, K.; Zhu, G.; Wang, W. Friction and wear behaviors of catalytic methylesterified bio-oil. Tribol. Int. 2014, 71, 168174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knothe, G.; Steidley, K.R. The effect of metals and metal oxides on biodiesel oxidative stability from promotion to inhibition. Fuel Process. Technol. 2018, 177, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arumugam, S.; Sriram, G.; Ellappan, R. Bio-lubricant-biodiesel combination of rapeseed oil: An experimental investigation on engine oil tribology, performance, and emissions of variable compression engine. Energy 2014, 72, 618–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, I.M.A.; Barradas-Filho, A.O.; Marques, E.P.; Pereira, C.F.; Marques, A.L.B. Oxidative stability of biodiesel by mixture design and a four-component diagram. Fuel 2018, 219, 389398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fattah, I.M.R.; Masjuki, H.H.; Kalam, M.A.; Mofijur, M.; Abedin, M.J. Effect of antioxidant on the performance and emission characteristics of a diesel engine fueled with palm biodiesel blends. Energy Convers. Manag. 2014, 79, 265272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H. Effect of temperature on the corrosion behavior of mild steel upon exposure to palm biodiesel. Energy 2011, 36, 3328–3334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, K.V.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Fazal, M.A.; Gupta, M. Corrosion of magnesium and aluminum in palm biodiesel: A comparative evaluation. Energy 2013, 57, 478–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, A.T.; Tabatabaei, M.; Aghbashlo, M. A review of the effect of biodiesel on the corrosion behavior of metals/alloys in diesel engines. Energy Sources Part A Recovery Util. Environ. Eff. 2020, 42, 2923–2943. [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, X.P.; Vu, H.N. Interactions between Used Cooking Oil Biodiesel Blends and Elastomer Materials in the Diesel Engine. Int. J. Ren. Energy Dev. 2019, 8, 119–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.M.; Dutra-Pereira, F.K.; Bicudo, T.C. Influence of stainless steel corrosion on biodiesel oxidative stability during storage. Fuel 2019, 249, 73–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kugelmeier, C.L.; Monteiro, M.R.; Da Silva, R.; Kuri, S.E.; Sordi, V.L.; Della Rovere, C.A. Corrosion behavior of carbon steel, stainless steel, aluminum, and copper upon exposure to biodiesel blended with petrodiesel. Energy 2021, 226, 120344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, S.; Saxena, R.C.; Kumar, A.; Negi, M.S.; Bhatnagar, A.K.; Goyal, H. Corrosion Behavior of Biodiesel from Seed Oils of Indian Origin on Diesel Engine Parts. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007, 88, 303–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H. Biodiesel degradation mechanism upon exposure of metal surfaces: A study on biodiesel sustainability. Fuel 2022, 310, 122341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, E.; Xu, Y.; Hu, X.; Pan, L.; Jiang, S. Corrosion behavior of metals in biodiesel from rapeseed oil and methanol. Renew. Energy 2012, 37, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H.; Ann, L.J.; Fazal, M.A. Corrosion Characteristics of Copper and Leaded Bronze in Palm Biodiesel. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 329–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCornick, R.L.; Ratcliff, M.; Moens, L.; Lawrence, T. Several factors affecting the stability of biodiesel in standard accelerated tests. Fuel Process. Technol. 2007, 88, 651–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazal, M.A.; Haseeb, A.S.M.A.; Masjuki, H.H. Comparative Corrosive Characteristics of Petroleum Diesel and Palm Biodiesel for Automotive Materials. Fuel Process. Technol. 2010, 91, 1308–1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmmad, M.S.; Hassan, M.B.H.; Kalam, M.A. Comparative corrosion characteristics of automotive materials in Jatropha biodiesel. Int. J. Green Energy 2018, 15, 393–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuleta, E.C.; Baena, L.; Rios, L.A.; Calderon, J.A. The oxidative stability of biodiesel and its impact on the deterioration of metallic and polymeric materials: A review. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2012, 23, 2159–2167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, J.; Yu, W.; You, Y.; Liu, L. Molecular modeling of the inhibition mechanism of 1-(2-aminoethyl)-2-alkyl-imidazoline. Corros. Sci. 2010, 52, 2059–2065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.; Wang, B.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Gao, G.; Zhou, J. Effect of Alkyl Chain Length on the Corrosion Inhibition Performance of Imidazolium-Based Ionic Liquids for Carbon Steel in 1 M HCl Solution: Experimental Evaluation and Theoretical Analysis. Langmuir 2024, 40, 8806–8819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Mansour, A.A.; Singh, M.; Thakur, S.; Pani, B.; Salghi, R. Relation of alkyl chain length and corrosion inhibition efficiency of N-acylated chitosans over mild steel in acidic medium. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2024, 4, 113179. [Google Scholar]

- Numin, M.S.; Jumbri, K.; Eng, K.K.; Hassan, A.; Borhan, N.; Daud, N.M.R.N.M.; A, A.M.N.; Suhor, F.; Dzulkifli, N.N. Effect of Alkyl Chain Length of Quaternary Ammonium Surfactant Corrosion Inhibitor on Fe (110) in Acetic Acid Media via Computer Simulation. ChemEngineering 2025, 9, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamindar, S.; Mandal, S.; Murmu, M.; Banerjee, P. Unveiling the future of steel corrosion inhibition: A revolutionary sustainable odyssey with a special emphasis on N+-containing ionic liquids through cutting-edge innovations. Mater. Adv. 2024, 5, 4563–4569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Feng, Y.; Zhou, X.; Wang, Q.; Cao, Y. Single and Double Alkyl Chain Quaternary Ammonium Salts as Environment-Friendly Corrosion Inhibitors for a Q235 Steel in 0.5 mol/L H2SO4 Solution. Coatings 2023, 13, 1847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Ballote, L.; López-Sansores, J.F.; Maldonado-López, L.; Garfias-Mesias, L.F. Corrosion Behavior of Aluminum Exposed to a Biodiesel. Electrochem. Commun. 2009, 11, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vergara-Juarez, F.; Hernandez-Medina, E.; Porcayo-Calderon, J.; Acevedo-Quiroz, M.E.; Perez-Quiroz, J.T.; Quinto-Hernandez, A. Corrosion on copper induced by biodiesel surrogates in the gas phase: The effect of the C=C double bond. Materials 2025, 18, 4395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, M.A.; Amin, S.; Mohamed, A.A. Current and emerging trends of inorganic, organic and eco-friendly corrosion inhibitors. RSC Adv. 2024, 14, 31877–31920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castillo-Robles, J.M.; de Freitas Martins, E.; Ordejón, P. Molecular modeling applied to corrosion inhibition: A critical review. Npj Mater. Degrad. 2024, 8, 72–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pehan, S.; Jerman, M.S.; Kegl, M.; Kegl, B. Biodiesel influence on tribology characteristics of a diesel engine. Fuel 2009, 88, 970–979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alves, S.M.; Mello, V.S.; Medeiros, J.S. Palm and soybean biodiesel compatibility with fuel system elastomers. Tribol. Int. 2013, 65, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hladky, K.; Dawson, J.L. The measurement of localized corrosion using electrochemical noise. Corros. Sci. 1982, 22, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.