Multi-UAV Cooperative Search in Partially Observable Low-Altitude Environments Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning

Highlights

- Propose a multi-agent deep reinforcement learning algorithm named Normalizing Graph Attention Soft Actor-Critic (NGASAC) to solve the problem of multi-UAV cooperative search in low-altitude partially observable environments.

- To address the multi-UAV collaborative search problem in real scenarios, we propose a phased search strategy.

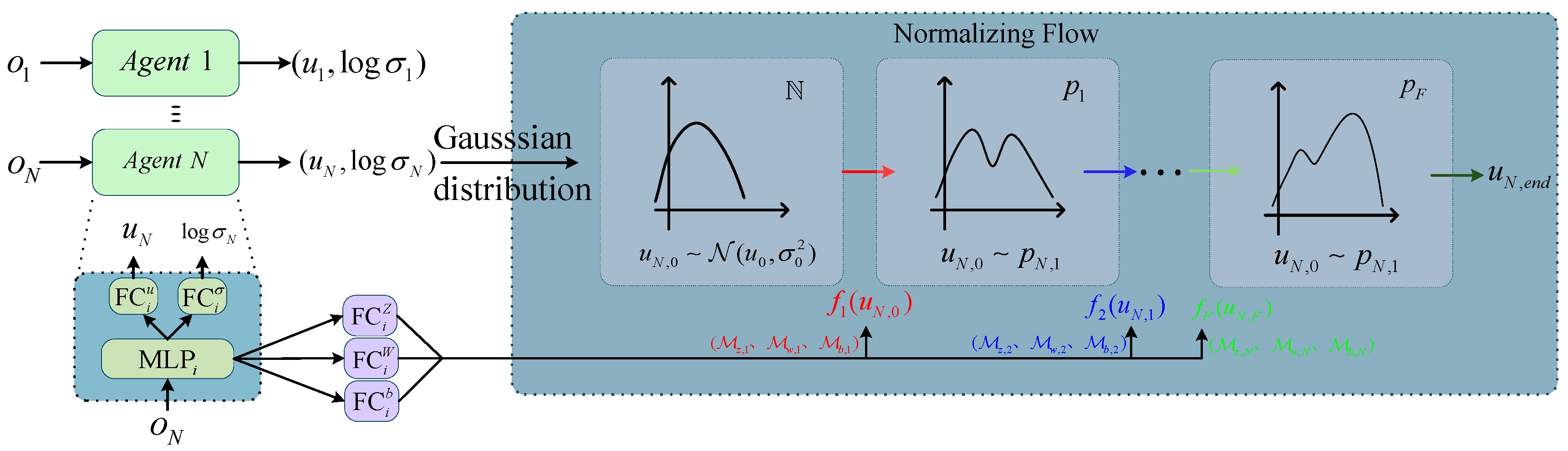

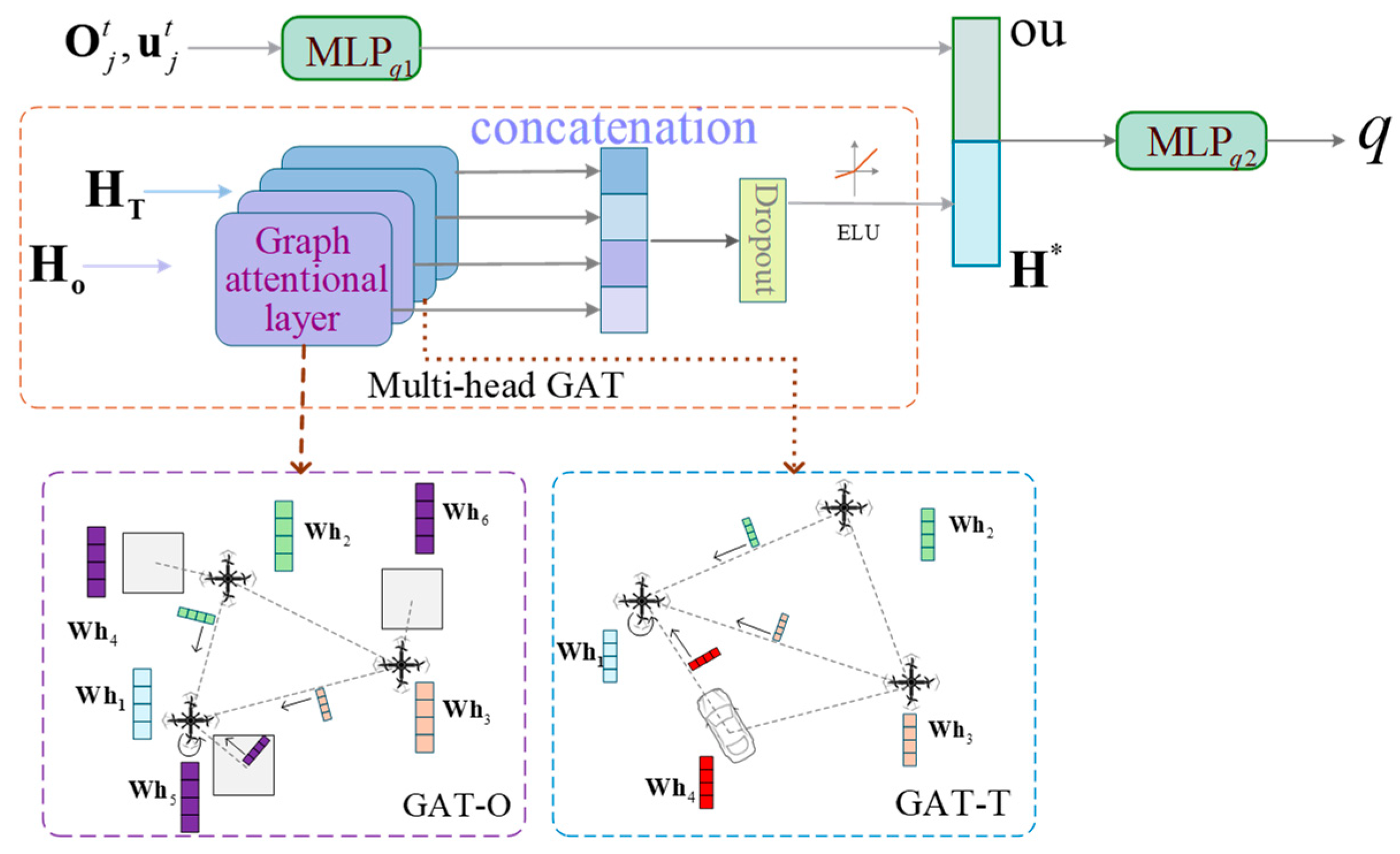

- NGASAC integrates a normalizing flow (NL) layer and a multi-head graph attention network (MHGAT). The normalizing flow technique maps traditional Gaussian sampling to a more complex action distribution, thereby enhancing the expressiveness and flexibility of the policy. Simultaneously, by constructing a multi-head graph attention network that captures “obstacle–target” relationships, the algorithm improves the UAVs’ ability to learn and reason about complex spatial topologies, leading to significantly better performance in cooperative search and stable surveillance of hidden targets.

- The phased search strategy achieves adaptive allocation of search resources by dynamically responding to changes in the target state, thereby enhancing search efficiency and task success rate.

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Cooperative Search

2.2. MADRL

3. System Model and Problem Formulation

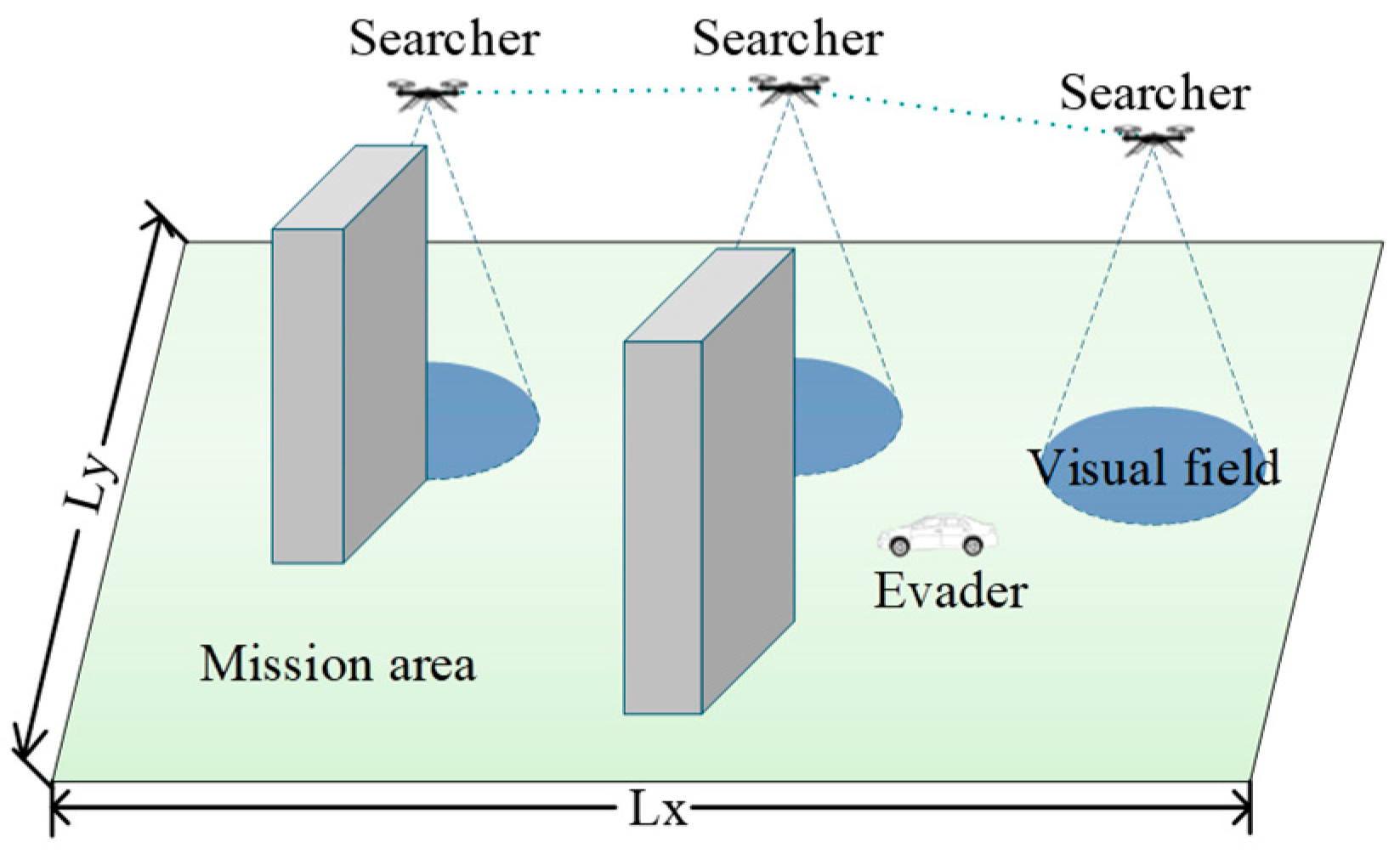

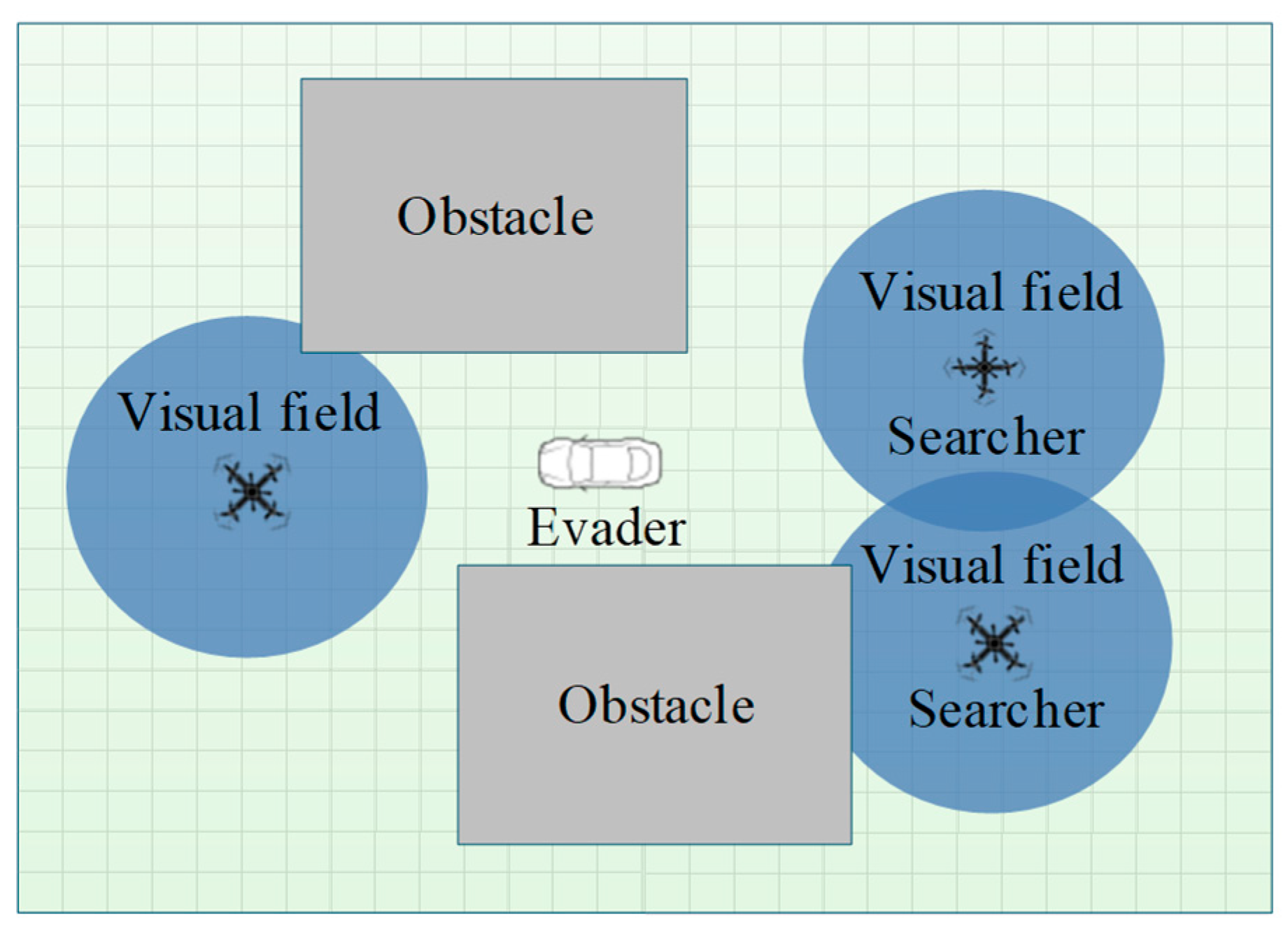

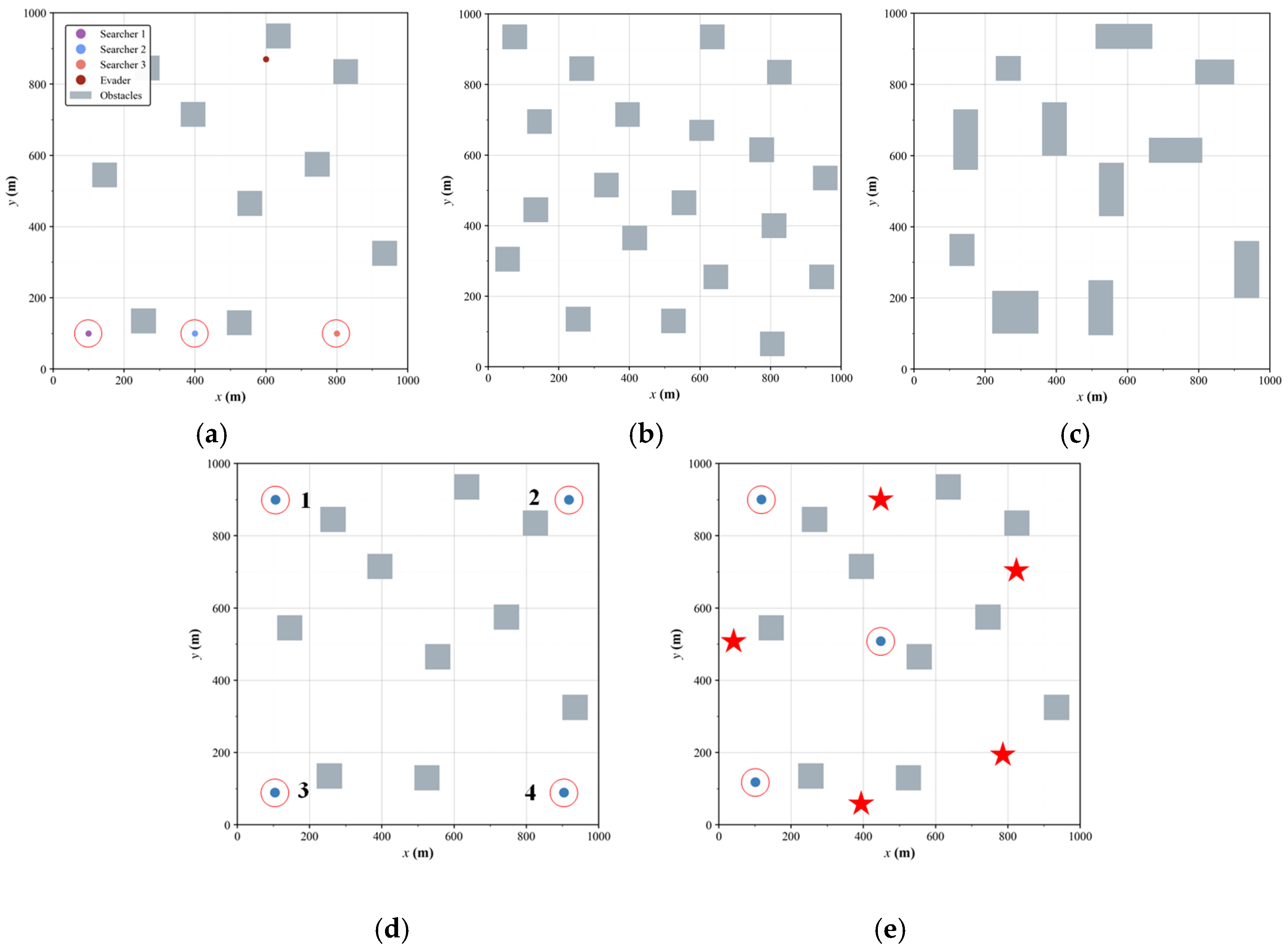

3.1. Scenario Description

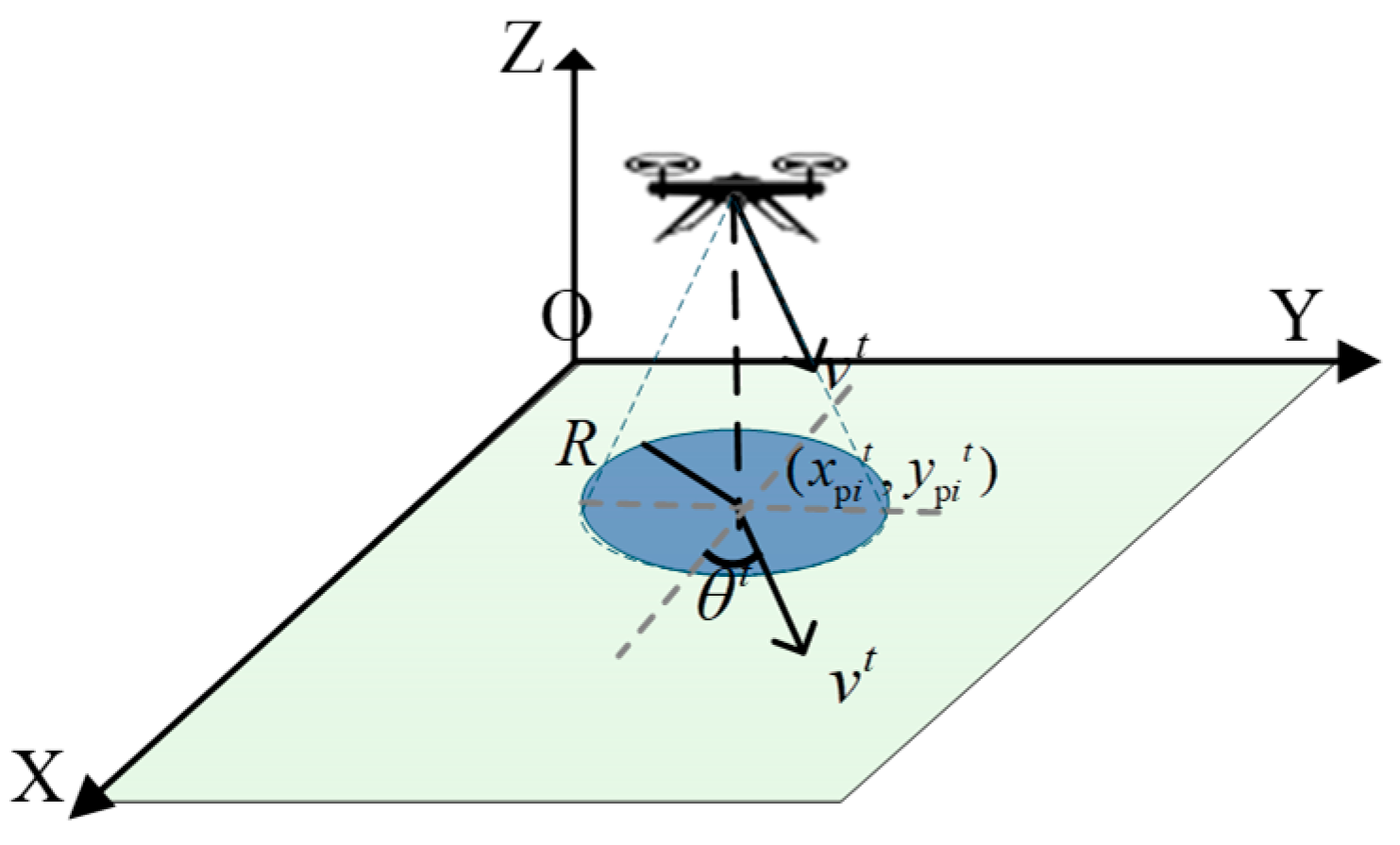

3.2. UAV Kinematic and Circular Sensing Range

3.3. Task Constraints

4. Methodology

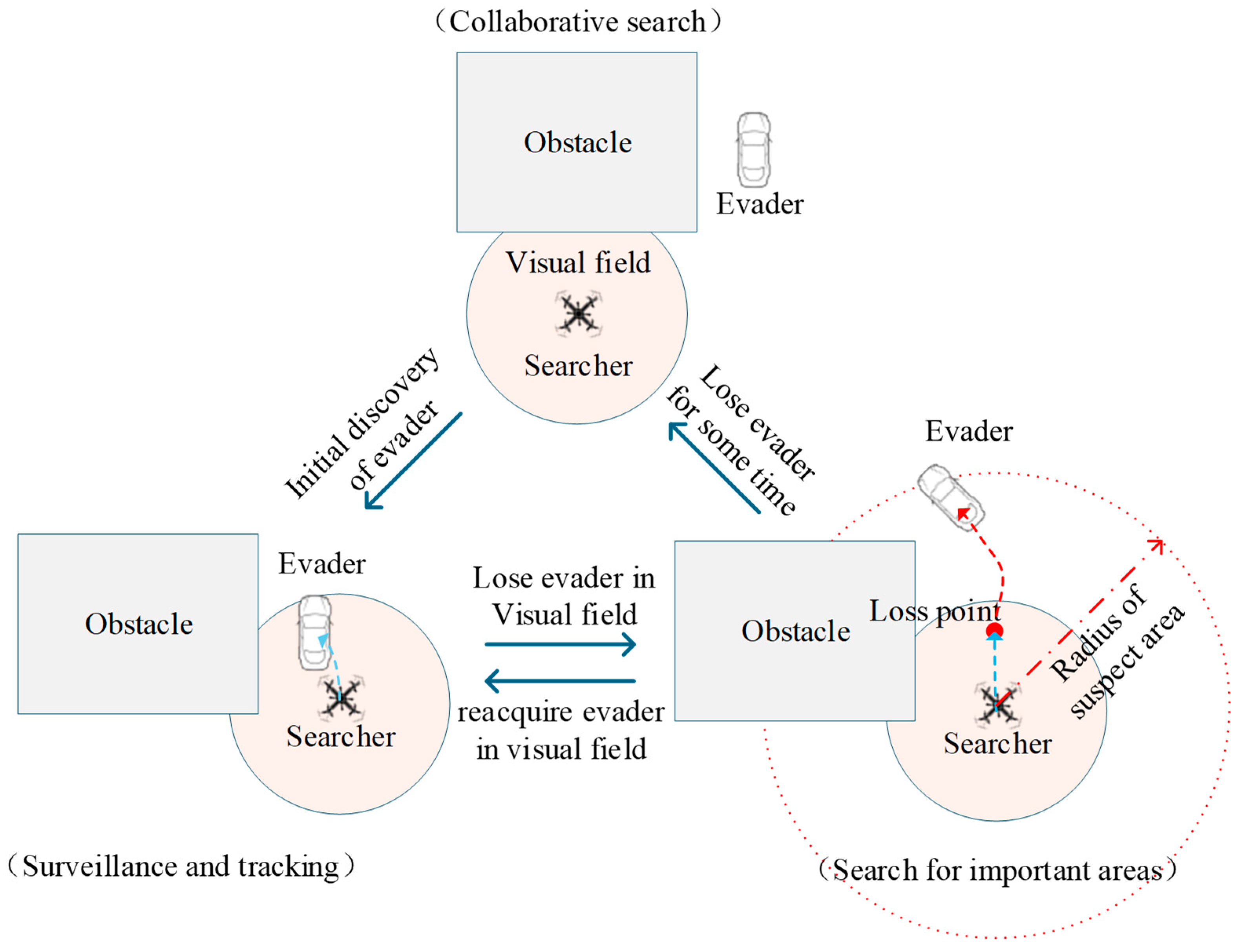

4.1. Introduction to Phased Search Strategy

4.2. POMDP

4.2.1. State Space

4.2.2. Action Space

4.2.3. Local Observation Space

4.2.4. Reward Function

4.3. NGASAC

4.3.1. Normalizing Flow-Based Actor Network

4.3.2. Multi-Head Graph Attention Critic Network

4.3.3. Training Algorithm

| Algorithm 1: NGASAC Algorithm |

| Input: Search space and initial positions of all agents Output: Policy networks for all agents 1: Initialize policy networks , -value networks , and target Q-value networks , with 2: Initialize replay buffer with capacity 3: for episode = 1: E do 4: for t = 1: do 5: Obtain global state and joint observation 6: for i = 1: N do 7: Extract individual observation from 8: Select action according to policy network 9: end for 10: Execute joint action 11: Receive reward ,next global state , and next joint observation 12: Store transition in 13: Sample a random batch from 14: Update Q-value networks by minimizing loss in Equation (43): , for 15: Update each policy network by minimizing loss in Equation (45): , for 16: Update temperature coefficient by minimizing loss in Equation (46): 17: Update target networks via soft update (Equation (44)) 18: end for 19: end for |

4.3.4. Algorithm Complexity Analysis

5. Simulations

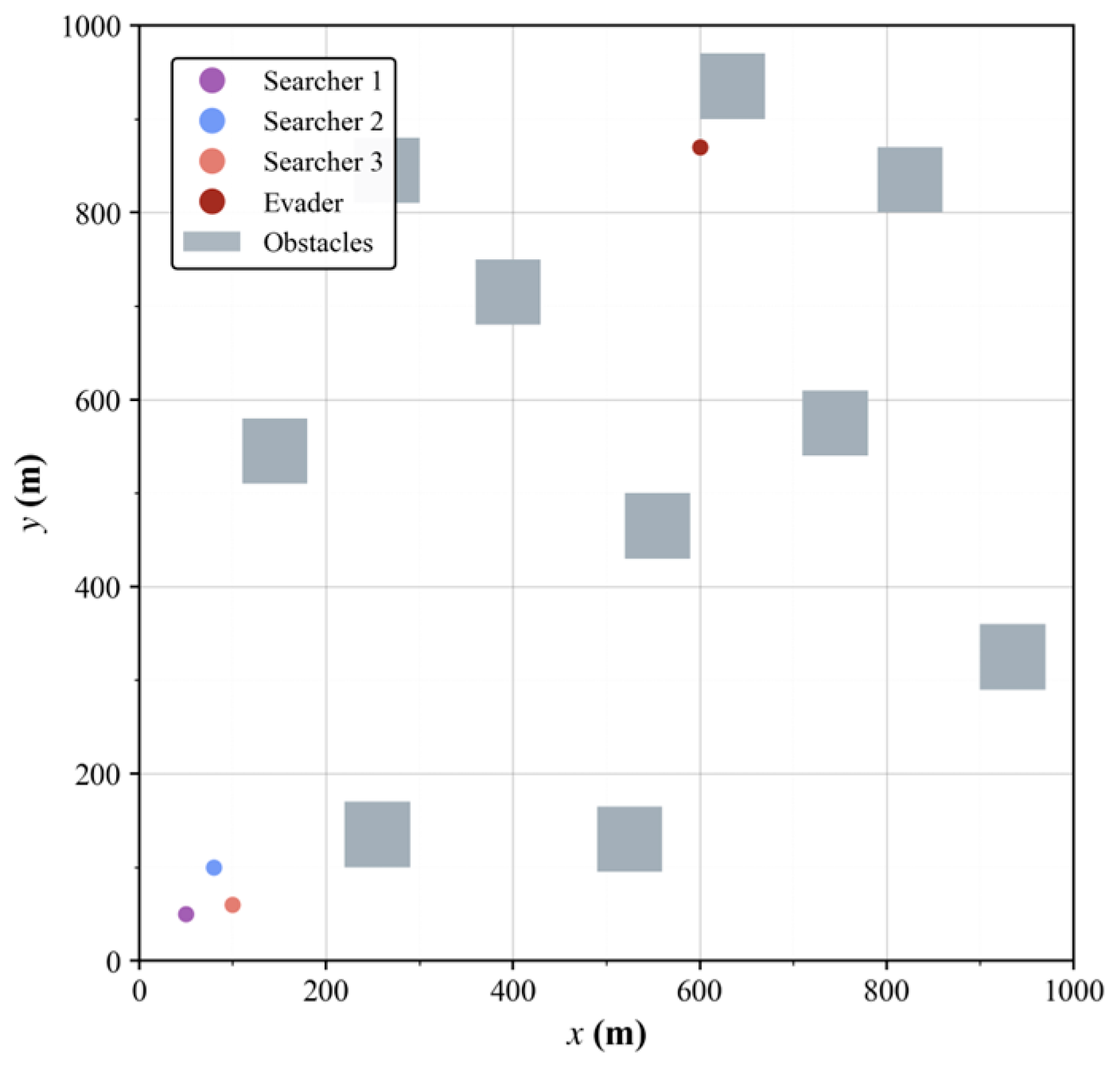

5.1. Simulation Environment Setup

5.2. Evasion Strategies

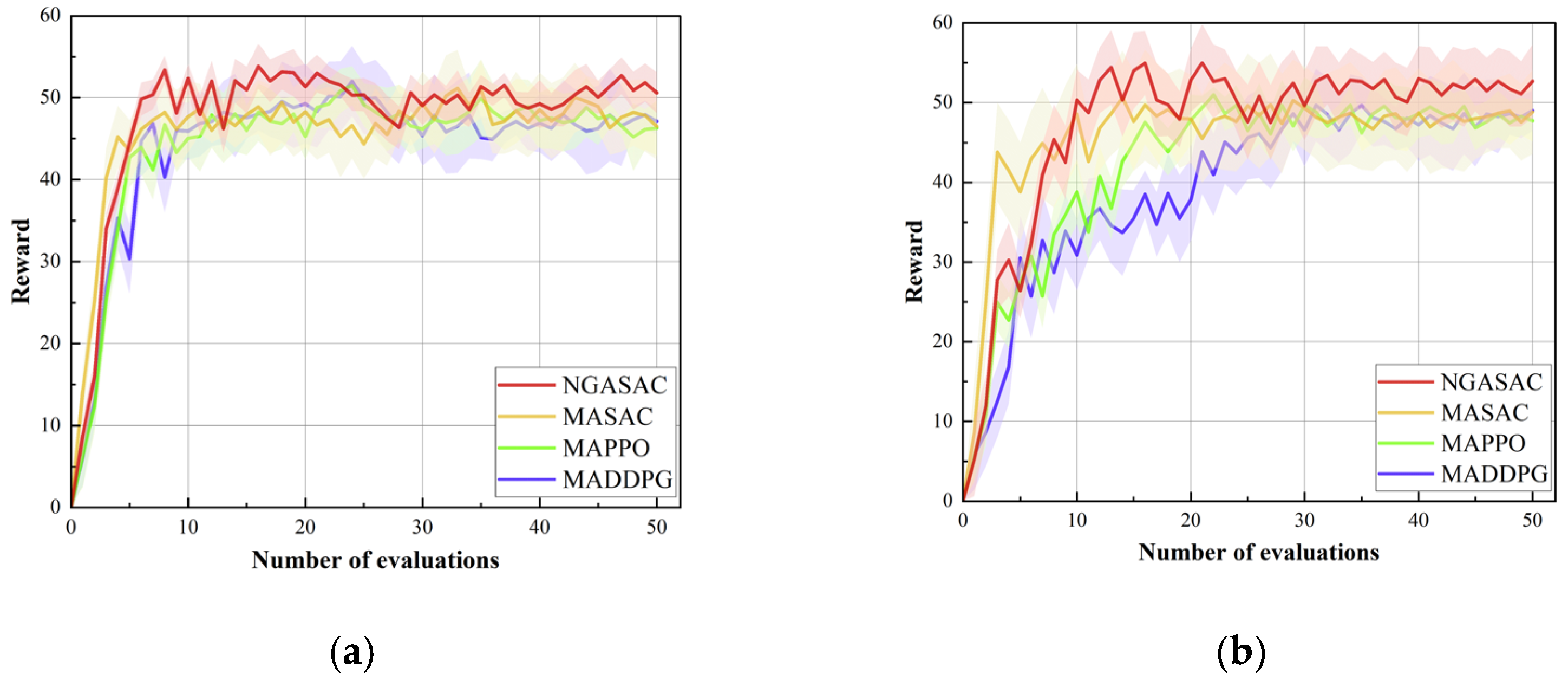

5.3. Comparative Simulations

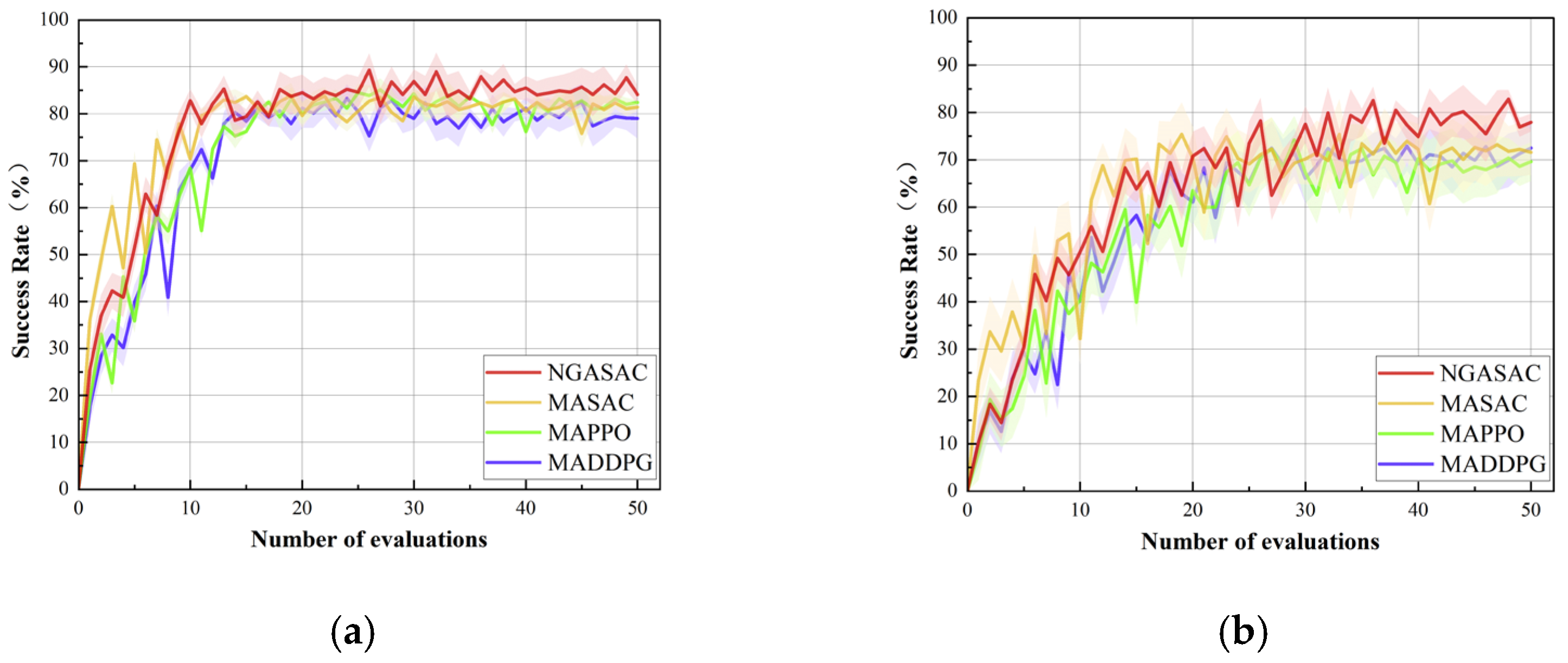

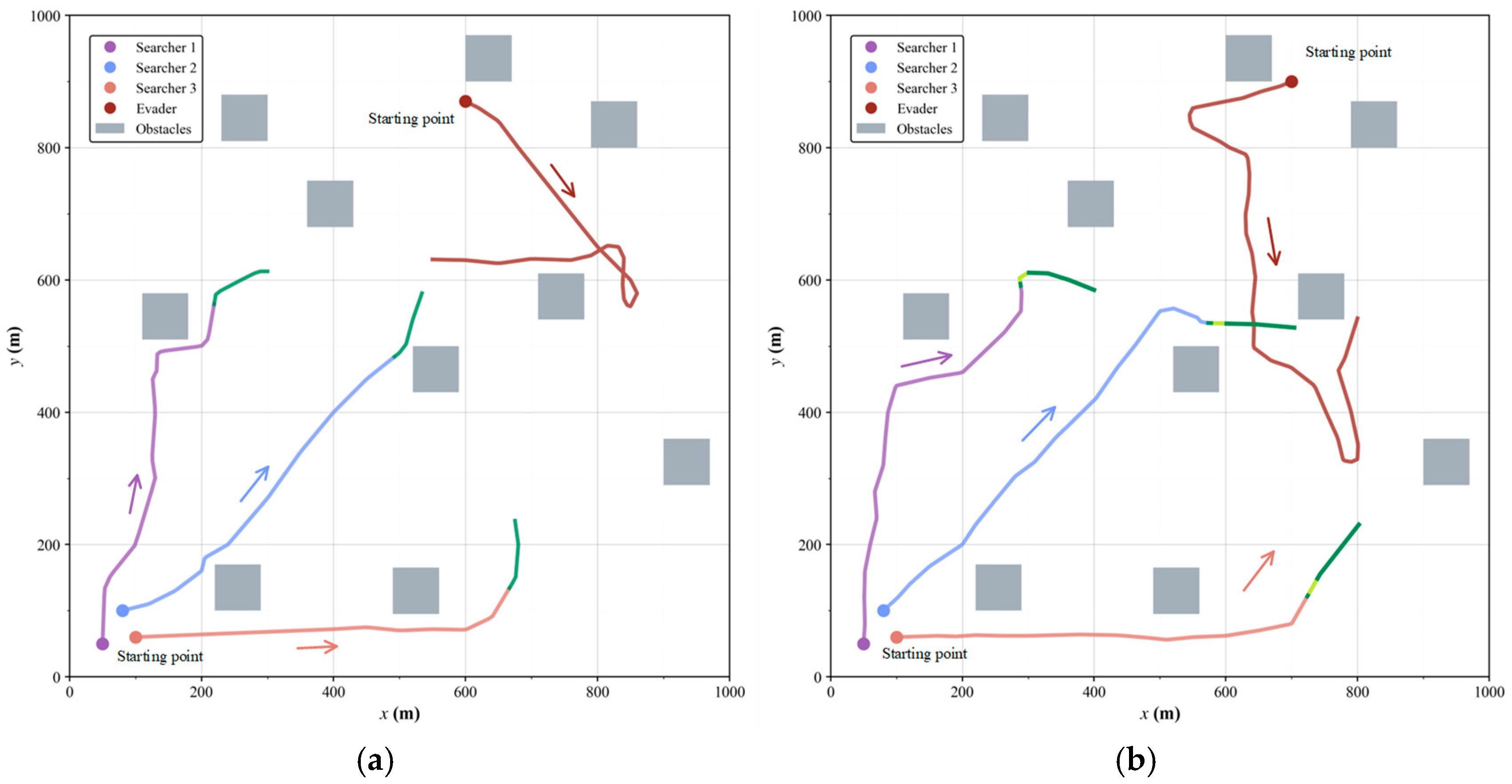

5.4. Generalization Simulations

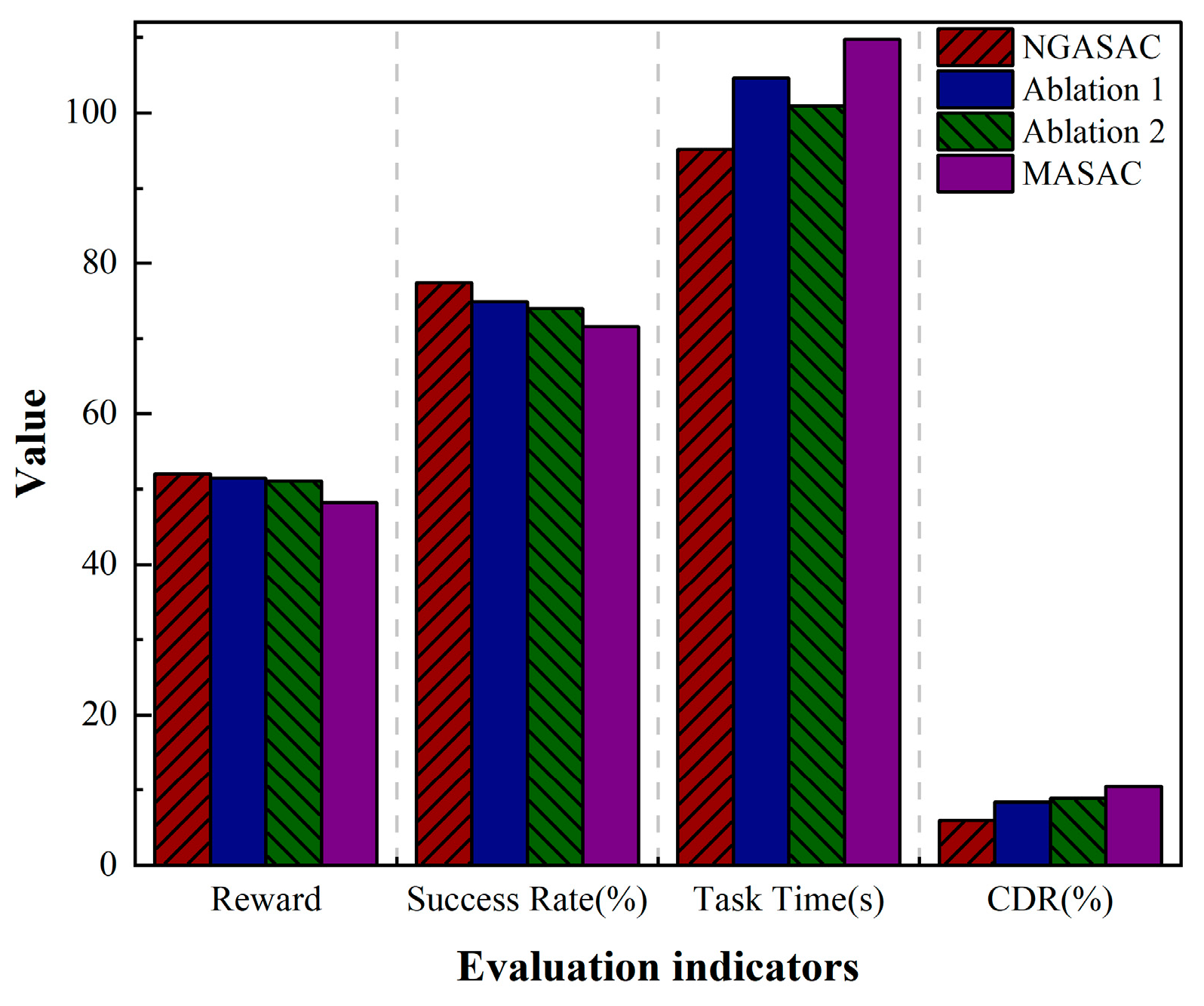

5.5. Ablation Studies

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zuo, Z.; Liu, C.; Han, Q.-L.; Song, J. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: Control Methods and Future Challenges. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 601–604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, J.; Song, D.; Shang, H.; Wang, N.; Hua, C.; Wu, C.; Qi, X.; Han, J. Search and rescue rotary-wing uav and its application to the lushan ms 7.0 earthquake. J. Field Robot. 2016, 33, 290–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, J.; Su, T.; Wang, Q.; Du, X.; Guizani, M. Multiple moving targets surveillance based on a cooperative network for multi-UAV. IEEE Commun. Mag. 2018, 56, 82–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, H.; Zhao, J.; Deng, Y.; Shi, Y.; Ding, X. Dynamic discrete pigeon-inspired optimization for multi-UAV cooperative search-attack mission planning. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2020, 57, 706–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Bao, W.; Zhu, X.; Fei, B.; Men, T.; Xiao, Z. Cooperative path optimization for multiple UAVs surveillance in uncertain environment. IEEE Internet Things J. 2021, 9, 10676–10692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.; Zhang, C.; Xu, C.; Xiong, F.; Zhang, Y.; Umer, T. Energy-efficient industrial internet of UAVs for power line inspection in smart grid. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 14, 2705–2714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, L.; Wan, L.; Wang, X. Learning-based resource allocation strategy for industrial IoT in UAV-enabled MEC systems. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2020, 17, 5031–5040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, T.H.; Hollinger, G.A.; Isler, V. Search and pursuit-evasion in mobile robotics: A survey. Auton. Robot. 2011, 31, 299–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Wu, G.; Luo, B.; Wang, L. Multi-UAV cooperative pursuit strategy with limited visual field in urban airspace: A multi-agent reinforcement learning approach. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2025, 12, 1350–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zong, Q.; Zhang, X.; Dou, L.; Tian, B. Game of drones: Multi-UAV pursuit-evasion game with online motion planning by deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2022, 34, 7900–7909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Zha, W.; Peng, Z.; Gu, D. Multi-player pursuit–evasion games with one superior evader. Automatica 2016, 71, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, X.; Gan, W.; Song, D.; Zhou, L. Pursuit-evasion game strategy of USV based on deep reinforcement learning in complex multi-obstacle environment. Ocean. Eng. 2023, 273, 114016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, B.P.L.; Ong, B.J.Y.; Loh, L.K.Y.; Liu, R.; Yuen, C.; Soh, G.S.; Tan, U.X. Multi-AGV’s temporal memory-based RRT exploration in unknown environment. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2022, 7, 9256–9263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, X.; Zhou, Z.; Li, Y.; Xiao, B.; Xun, Y. Multi-UAV adaptive cooperative formation trajectory planning based on an improved MATD3 algorithm of deep reinforcement learning. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2024, 73, 12484–12499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Dong, L.; Sun, C. Cooperative control for multi-player pursuit-evasion games with reinforcement learning. Neurocomputing 2020, 412, 101–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Desouky, S.F.; Schwartz, H.M. Self-learning fuzzy logic controllers for pursuit–evasion differential games. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2011, 59, 22–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Wang, H.; Xu, Z. Cooperative pursuit strategy for multi-UAVs based on DE-MADDPG algorithm. Acta Aeronaut. Et Astronaut. Sin. 2022, 43, 522–535. [Google Scholar]

- Haarnoja, T.; Zhou, A.; Abbeel, P.; Levine, S. Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR), Stockholm, Sweden, 10–15 July 2018; pp. 1861–1870. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, B.; Hu, T.; Zjou, Y.; Huang, T.; Yang, C.; Gui, W. Survey on Multi-agent Reinforcement Learning for Control and Decision-making. ACTA Autom. Sin. 2025, 51, 510–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, B.; Rashid, T.; Schroeder de Witt, C.; Kamienny, P.-A.; Torr, P.H.S.; Böhmer, W.; Whiteson, S. Facmac: Factored multi-agent centralised policy gradients. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12208–12221. [Google Scholar]

- Ackermann, J.; Gabler, V.; Osa, T.; Sugiyama, M. Reducing overestimation bias in multi-agent domains using double centralized critics. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.01465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rezende, D.; Mohamed, S. Variational inference with normalizing flows. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning (PMLR), Lille, France, 7–9 July 2015; pp. 1530–1538. [Google Scholar]

- Lillicrap, T.P.; Hunt, J.J.; Pritzel, A.; Heess, N.; Erez, T.; Tassa, Y.; Silver, D.; Wierstra, D. Continuous control with deep reinforcement learning. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1509.02971. [Google Scholar]

- Ben, J.; Sun, Q.; Liu, K.; Yang, X.; Zhang, F. Multi-head multi-order graph attention networks. Appl. Intell. 2024, 54, 8092–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, B.; Bao, W.; Zhu, X.; Liu, D.; Men, T.; Xiao, Z. Autonomous cooperative search model for multi-UAV with limited communication network. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 19346–19361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, G.; Lei, L.; Zhang, X.; Li, Z.; Cai, S.; Zhang, L. Multi-UAV cooperative search based on reinforcement learning with a digital twin driven training framework. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2023, 72, 8354–8368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, K.; Chen, C.; Wu, T.; Xin, B.; Liang, M.; Deng, F. Evolutionary state estimation-based multi-strategy jellyfish search algorithm for multi-UAV cooperative path planning. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 10, 2490–2507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.Q.; Lin, X.; Zhu, Y.F.; Tian, J.; Zhu, Z. Enhancing Multi-UAV Reconnaissance and Search Through Double Critic DDPG With Belief Probability Maps. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2024, 9, 3827–3842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Y.; Lee, S. Efficient multi-UAV path planning for collaborative area search operations. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 8728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hentout, A.; Maoudj, A.; Kouider, A. Shortest Path Planning and Efficient Fuzzy Logic Control of Mobile Robots in Indoor Static and Dynamic Environments. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2024, 27, 21–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, K.; Xu, J.; Yuan, L.; Li, M.; Qian, C.; Zhang, Z.; Yu, Y. Multi-agent dynamic algorithm configuration. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2022, 35, 20147–20161. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, F.; Gong, W.; Wang, L.; Jin, Y. Constrained multi-objective optimization with deep reinforcement learning assisted operator selection. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2024, 11, 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.R.; Hong, Y.T.; Wang, J.L.; Xu, J.P.; Tang, Y.; Han, Q.-L.; Kurths, J. Cooperative and competitive multi-agent systems: From optimization to games. IEEE/CAA J. Autom. Sin. 2022, 9, 763–783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, R.S.; Barto, A.G. Reinforcement Learning: An Introduction; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J.; Luo, J.; Jiang, C.; Lin, G. A multi-agent deep reinforcement learning approach for multi-UAV cooperative search in multi-layered aerial computing networks. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 10, 2490–2507. [Google Scholar]

- Du, W.; Guo, T.; Chen, J.; Li, B.; Zhu, G.; Cao, X. Cooperative pursuit of unauthorized UAVs in urban airspace via Multi-agent reinforcement learning. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2021, 128, 103122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mateescu, A.; Popescu, D.C.; Stefan, I.L. Machine Learning Control for Assistive Humanoid Robots Using Blackbox Optimization of PID Loops Through Digital Twins. Rom. J. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2025, 28, 63–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Souza Junior, C. Hunter Drones: Drones Cooperation for Tracking an Intruder Drone. Ph.D. Thesis, Université de Technologie de Compiègne, Compiègne, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lefebvre, T.; Dubot, T. Conceptual design study of an anti-drone drone. In Proceedings of the 16th AIAA Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, Washington, DC, USA, 13–17 June 2016; p. 3449. [Google Scholar]

- Lai, Y.C.; Lin, T.Y. Vision-based mid-air object detection and avoidance approach for small unmanned aerial vehicles with deep learning and risk assessment. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Name | Symbol | Value | Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Angular Velocity | rad/s | ||

| Evader Velocity | 12 | m/s | |

| Searcher Velocity | 9–11 | m/s | |

| Searcher Acceleration | −1–1 | m/s2 | |

| Searcher Sensing Radius | 200 | m | |

| Minimum Safe Distance | 1 | m | |

| Maximum Radar Range | 100 | m | |

| Obstacle Warning Distance | 25 | m | |

| Required Monitoring Duration | 10 | s |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter | Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training steps | Replay buffer size | ||

| Batch size | 256 | Soft update coefficient | 0.01 |

| Discount factor | 0.95 | Dropout rate | 0.01 |

| Optimizer | Adam | LeakyReLU parameter | 0.2 |

| Number of attention heads | 2 and 2 | Constant | |

| Number of flow layers | 4 | Constant | |

| Hidden layer dimension | 64 | Constant | 100 |

| Actor network learning rate | Constant | 0.25 | |

| Critic network learning rate | Constant | 1.2 | |

| Entropy learning rate | Constant | 0.02 | |

| Success reward | 10 | Failure penalty | −10 |

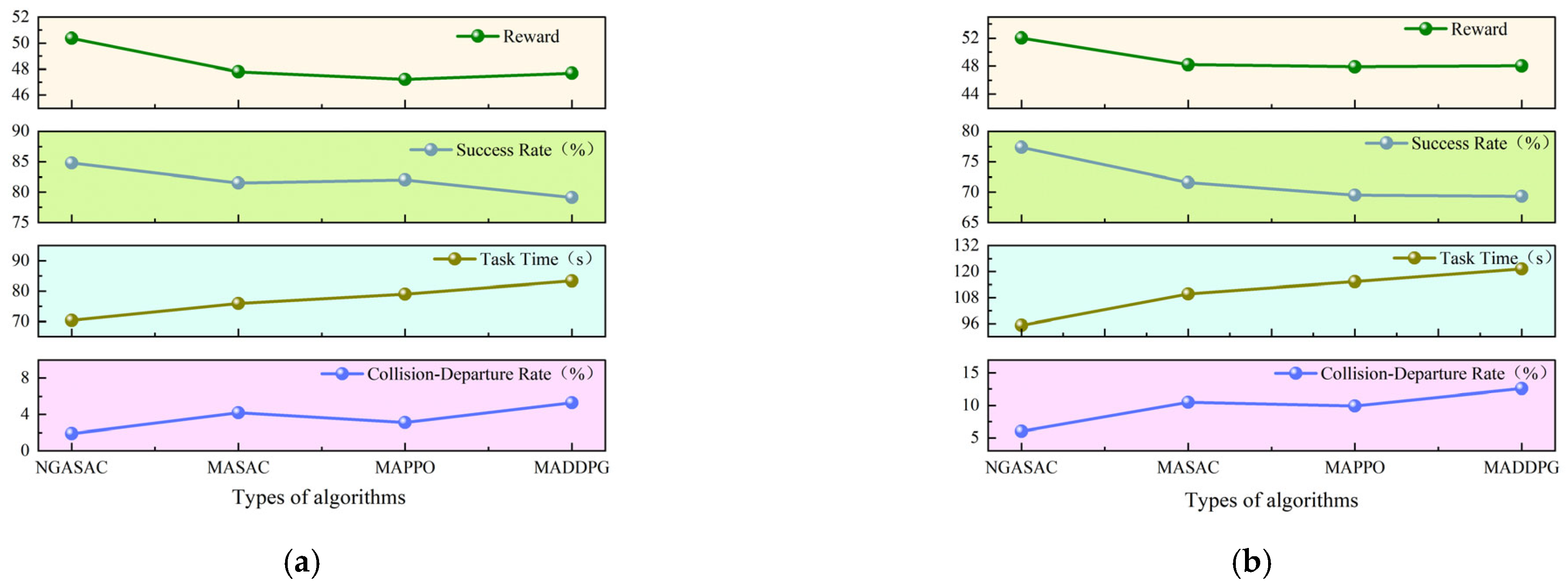

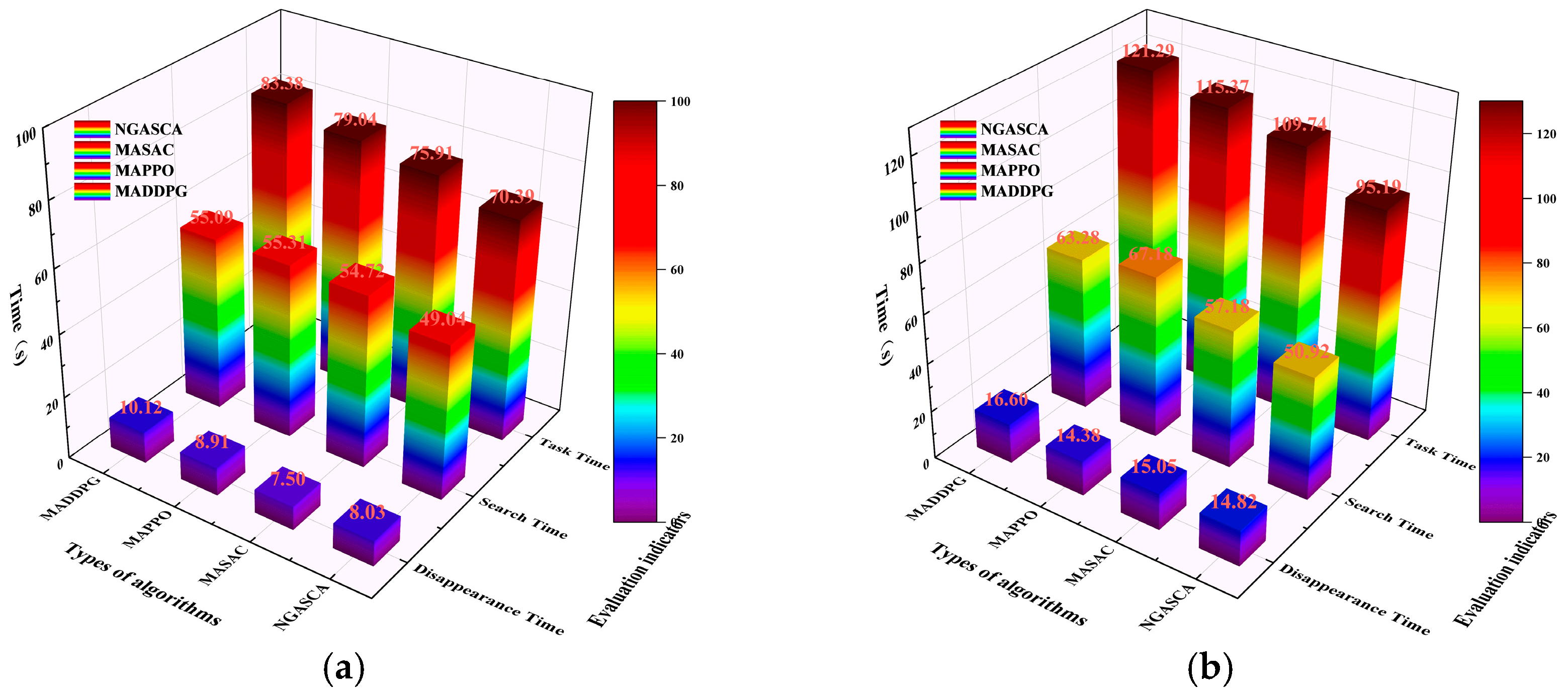

| Evasion Strategy | Random Evasion | Evasive Escape | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Algorithm | NGASAC | MASAC | MAPPO | MADDPG | NGASAC | MASAC | MAPPO | MADDPG |

| Reward | 50.38 ± 2.30 | 47.80 ± 4.14 | 47.22 ± 3.82 | 47.69 ± 4.35 | 52.03 ± 4.93 | 48.20 ± 6.88 | 47.90 ± 4.06 | 48.04 ± 5.63 |

| Success Rate (%) | 84.80 | 81.50 | 82.00 | 79.10 | 77.40 | 71.60 | 69.50 | 69.30 |

| Task Time (s) | 70.39 ± 6.30 | 75.91 ± 5.74 | 79.04 ± 5.05 | 83.38 ± 4.99 | 95.19 ± 8.49 | 109.74 ± 9.03 | 115.37 ± 8.65 | 121.29 ± 7.37 |

| Collision Departure Rate (%) | 1.90 | 4.20 | 3.10 | 5.30 | 6.00 | 10.50 | 9.90 | 12.60 |

| Search Time (s) | 49.04 ± 7.36 | 54.72 ± 6.70 | 55.31 ± 6.37 | 55.09 ± 7.60 | 50.92 ± 8.58 | 57.18 ± 7.99 | 67.18 ± 6.22 | 63.28 ± 7.83 |

| Disappearance (s) | 8.03 ± 2.36 | 7.50 ± 2.44 | 8.91 ± 2.09 | 10.12 ± 3.81 | 14.82 ± 5.39 | 15.05 ± 4.40 | 14.38 ± 5.28 | 16.60 ± 6.35 |

| S0 | S1 | S2 | S3 | S4 | S5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward | 52.03 | 53.85 | 48.37 | 51.82 | 54.9 | N/A |

| Success Rate (%) | 77.40 | 81 | 69 | 75 | 88 | 90 |

| Task Time (s) | 95.19 | 88.40 | 112.74 | 101.57 | 74.60 | 92.49 |

| Collision Departure Rate (%) | 6 | 7 | 15 | 11 | 9 | 8 |

| Search Time (s) | 50.92 | 49.37 | 57.06 | 53.91 | 41.49 | N/A |

| Disappearance (s) | 14.82 | 18.26 | 30.11 | 26.5 | 12.88 | N/A |

| NGASAC | Ablation 1 | Ablation 2 | MASAC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reward | 52.03 | 51.44 | 51.08 | 48.2 |

| Success Rate (%) | 77.4 | 74.9 | 74 | 71.6 |

| Task Time (s) | 95.19 | 104.62 | 100.93 | 109.74 |

| Collision Departure Rate (%) | 6 | 8.4 | 8.9 | 10.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, X.-X.; Yao, W.-Q.; Zhang, Y.; Yu, H.; Wang, C. Multi-UAV Cooperative Search in Partially Observable Low-Altitude Environments Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Drones 2025, 9, 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120825

Yang X-X, Yao W-Q, Zhang Y, Yu H, Wang C. Multi-UAV Cooperative Search in Partially Observable Low-Altitude Environments Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Drones. 2025; 9(12):825. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120825

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Xiu-Xia, Wen-Qiang Yao, Yi Zhang, Hao Yu, and Chao Wang. 2025. "Multi-UAV Cooperative Search in Partially Observable Low-Altitude Environments Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning" Drones 9, no. 12: 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120825

APA StyleYang, X.-X., Yao, W.-Q., Zhang, Y., Yu, H., & Wang, C. (2025). Multi-UAV Cooperative Search in Partially Observable Low-Altitude Environments Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning. Drones, 9(12), 825. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120825