PLMT-Net: A Physics-Aware Lightweight Network for Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction in Interactive Driving Scenarios

Highlights

- A physics-aware, modular and vectorized architecture (PLMT-Net) achieves competitive accuracy on the Argoverse 1 dataset while reducing model parameters and inference time.

- Embedding physics priors at two levels—interaction-target filtering and physics-guided graph attention—improves the physical plausibility and stability of multi-agent trajectory prediction.

- The method offers a practical path to real-time, resource-constrained deployment without sacrificing prediction quality.

- Lightweight physics priors integrated into learned attention provide a generalizable design pattern that can enhance robustness and physical feasibility in future trajectory-forecasting systems.

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The overall architecture adopts a modular and vectorized design, enabling reduced model complexity and improved inference efficiency without compromising prediction performance.

- (2)

- We propose a physical-information-based strategy to filter interaction targets, eliminating irrelevant and disruptive agents.

- (3)

- We propose a graph attention network that incorporates physical priors to guide attention weights toward physically plausible interaction targets, effectively improving the realism and stability of interaction modeling.

- (4)

- We conduct experiments on the Argoverse 1 dataset. The proposed method strikes a favorable balance between prediction accuracy, physical feasibility, and computational efficiency, demonstrating promising performance and potential for practical applications.

2. Related Work

2.1. Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction

2.2. Physical Information Fusion Modeling

2.3. Lightweight Prediction Model

2.4. Our Method

3. Method

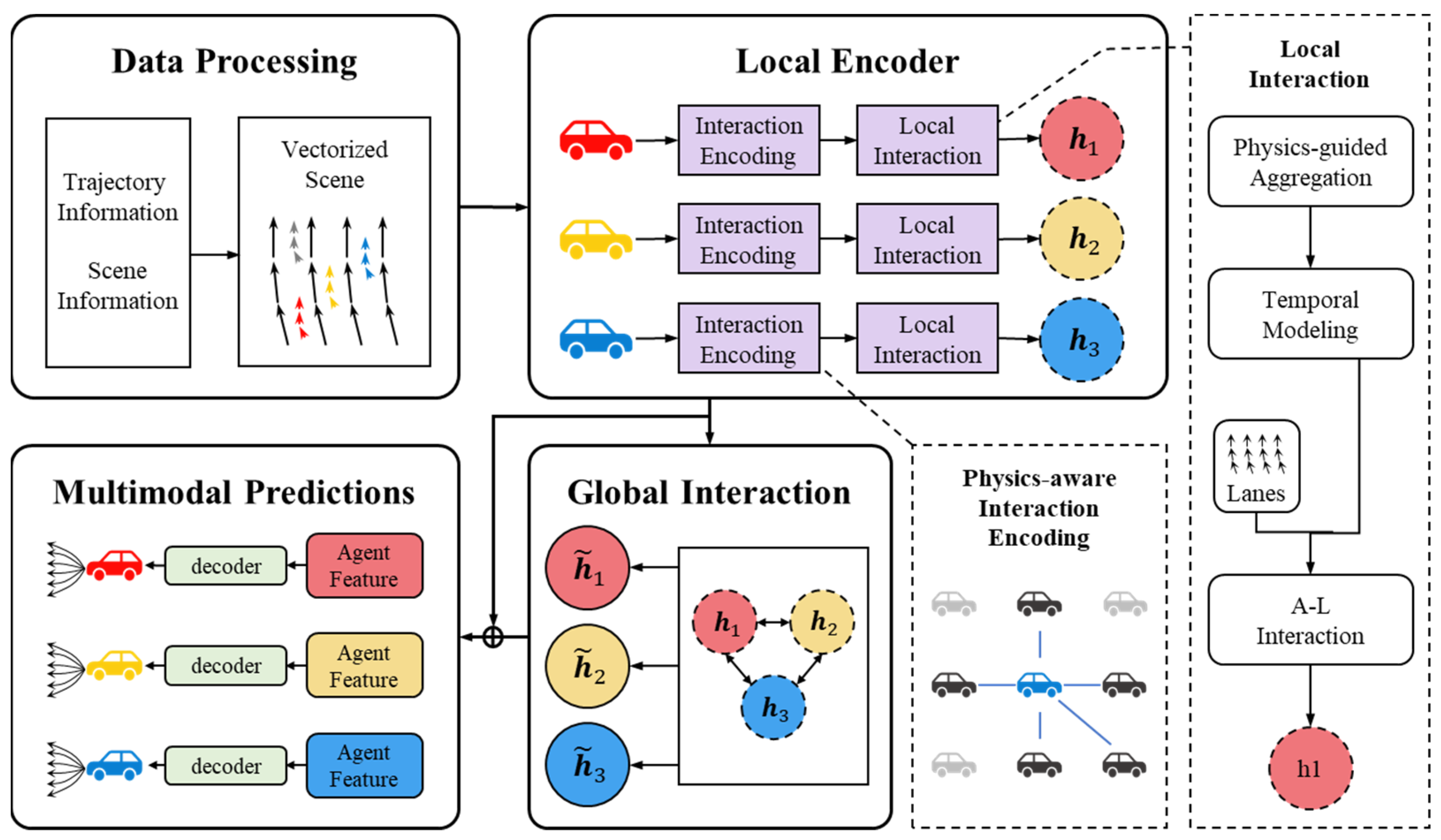

3.1. PLMT-Net Structure

3.2. Data Processing Module

3.3. Physics-Aware Local Encoder Module

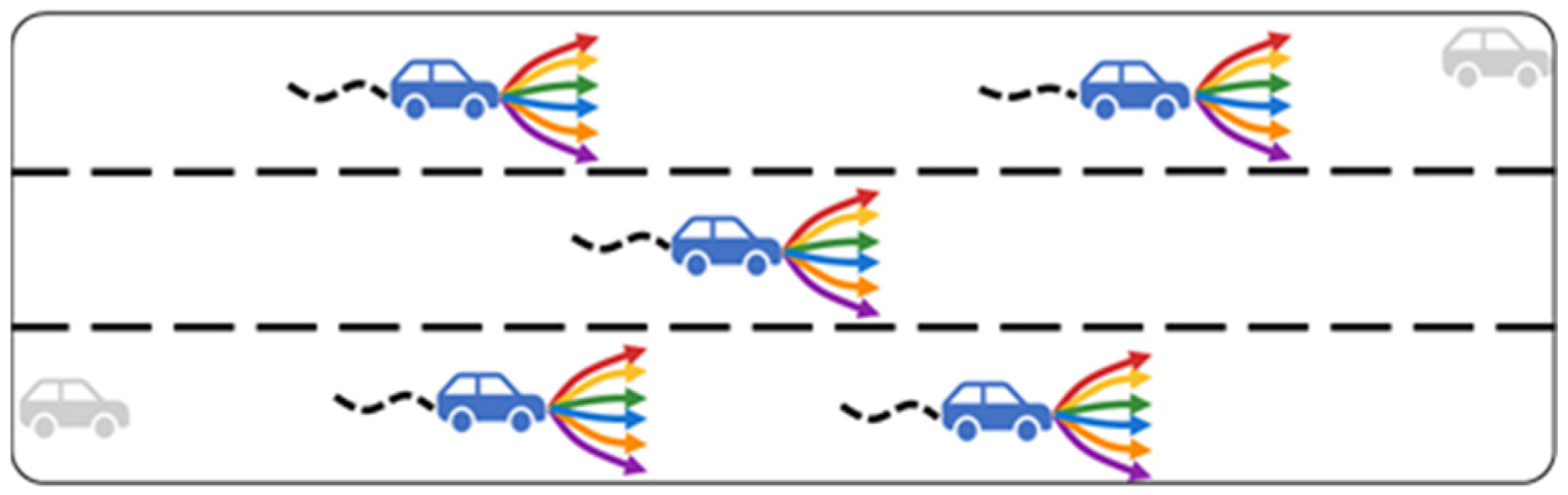

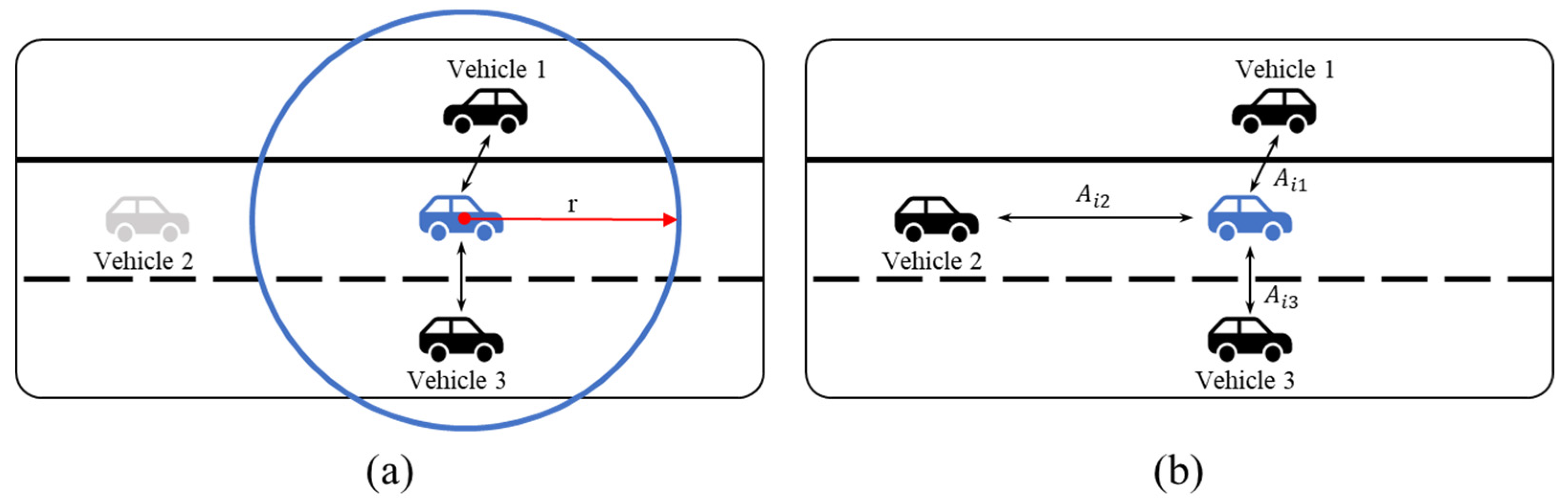

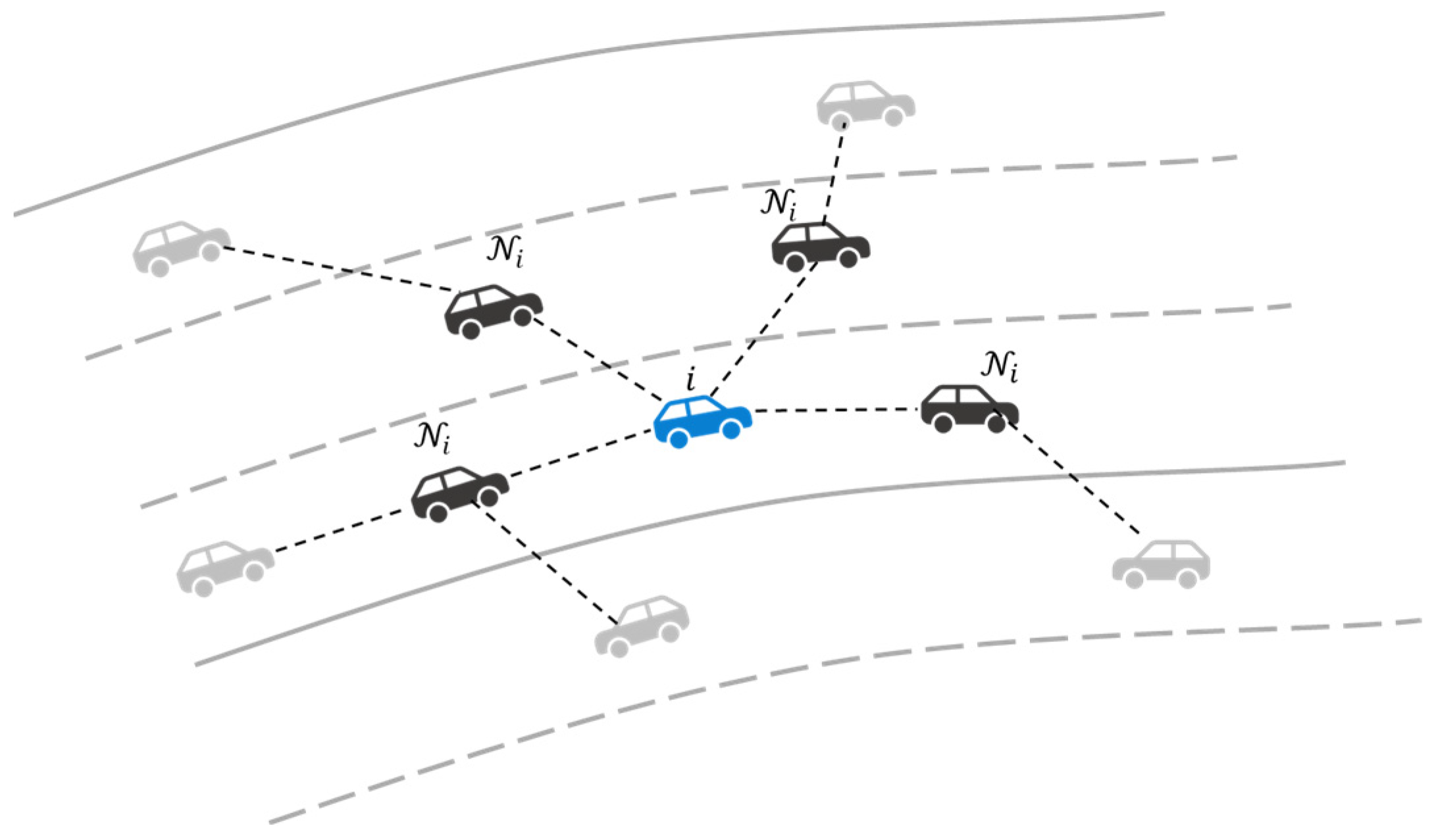

3.3.1. Physics-Aware Interaction Encoding

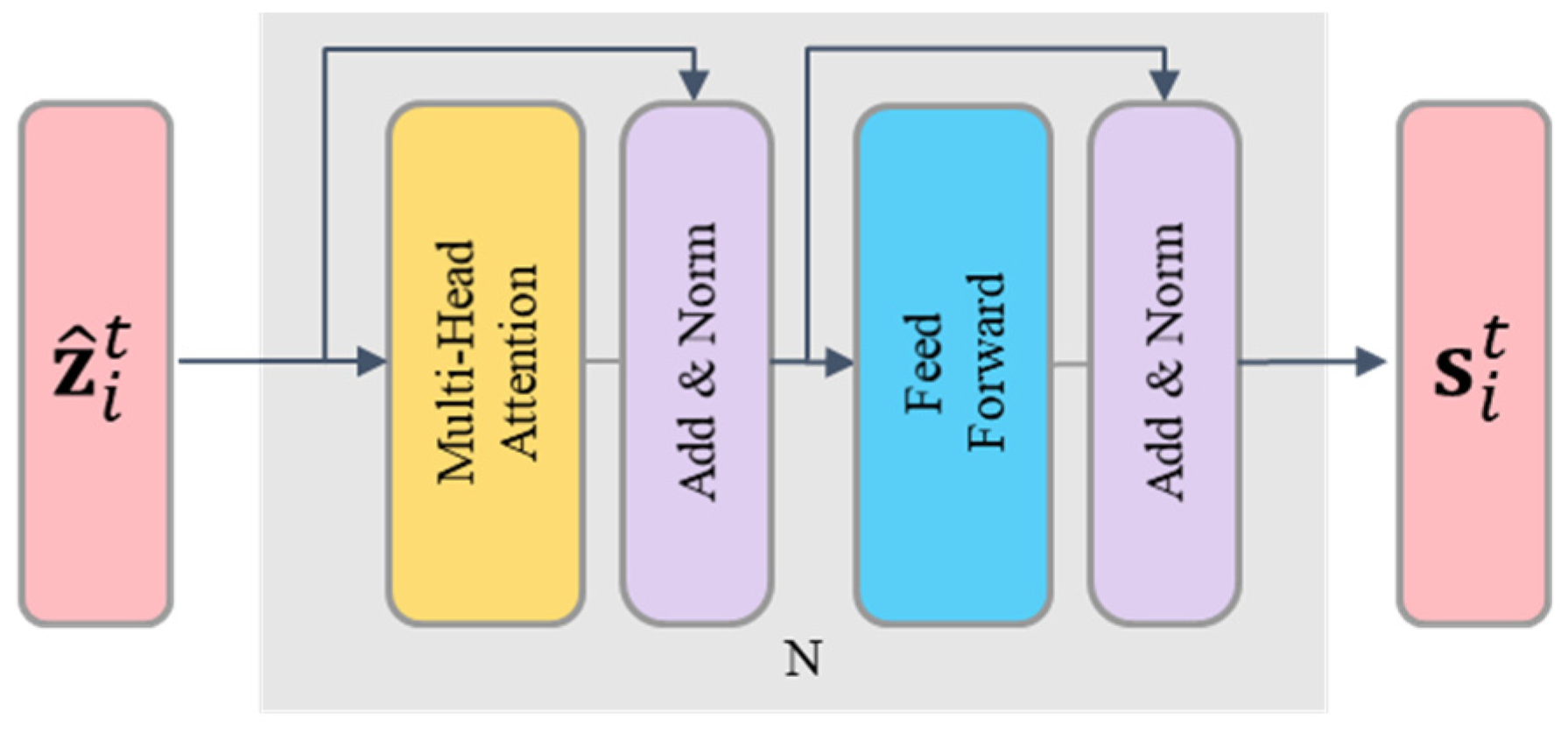

3.3.2. Physics-Guided Contextual Aggregation

3.3.3. Temporal Modeling

3.3.4. Agent and Lane Interaction

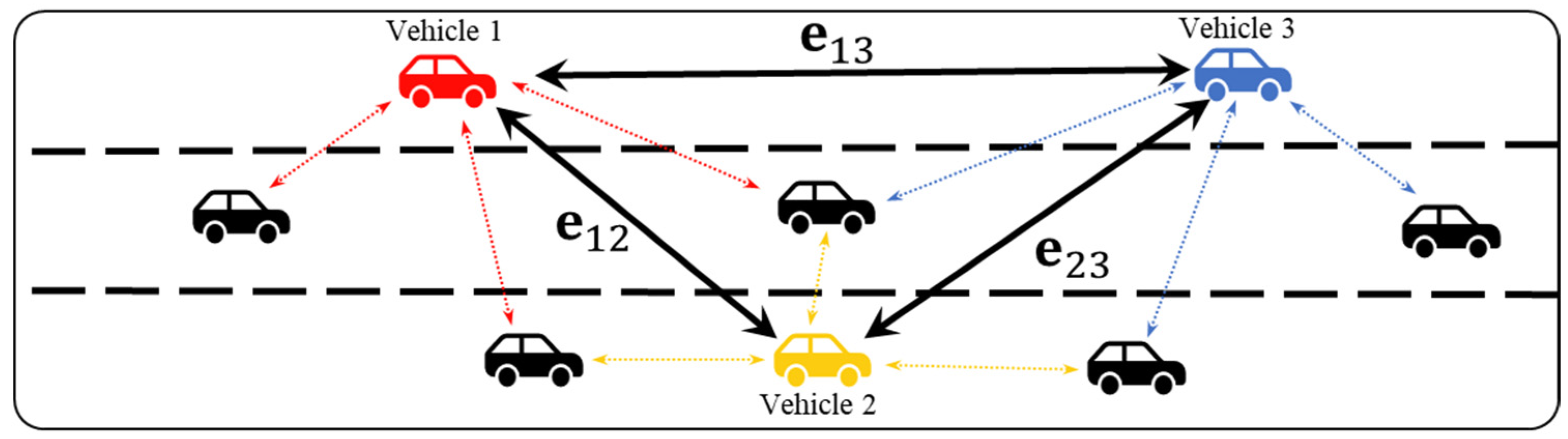

3.4. Global Interaction Module

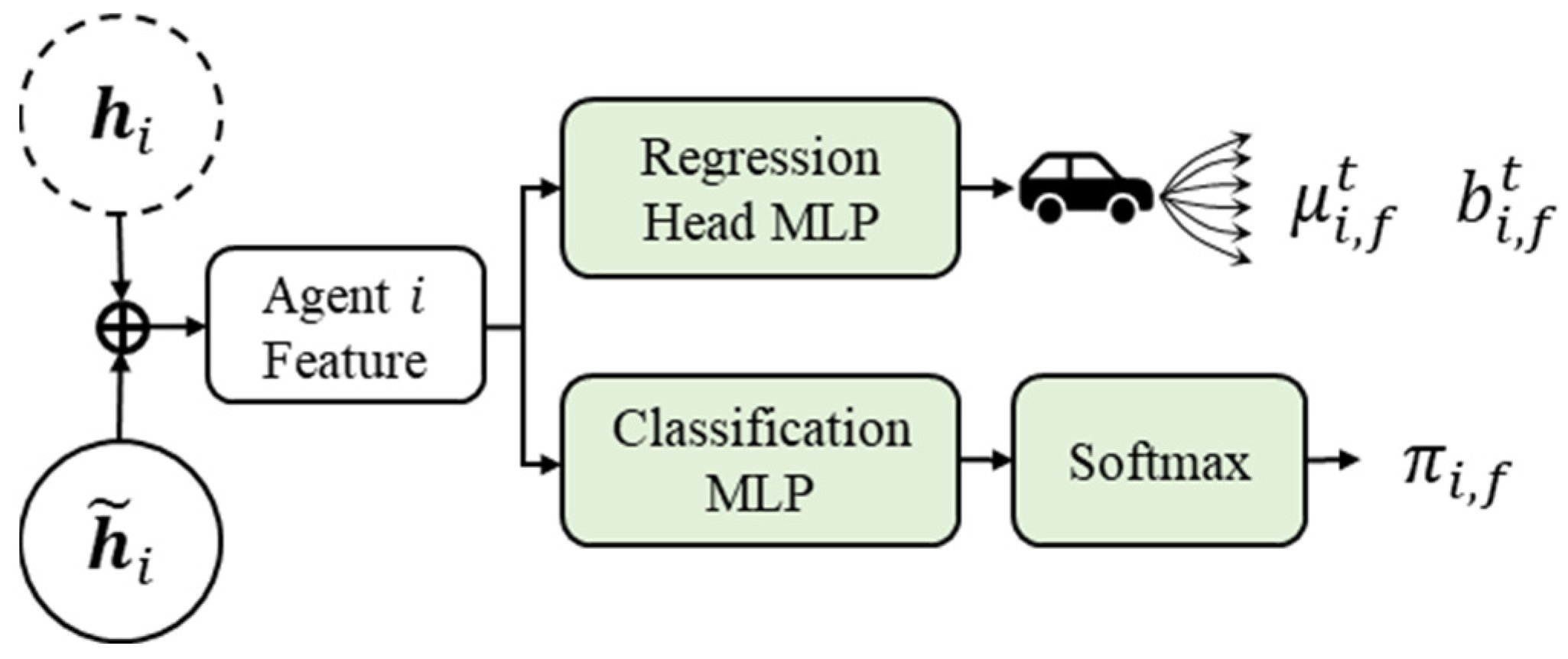

3.5. Multimodal Predictions Module

3.6. Loss Function

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Dataset

4.1.2. Evaluation Index

4.1.3. Implementation Details

4.2. Ablation Studies

4.2.1. Interactive Neighbor Filtering Strategy

4.2.2. Importance of Introducing Physical Information

4.2.3. Importance of Each Module

4.3. Inference Efficiency and Memory Footprint

4.4. Results

4.4.1. Comparison with Existing Methods

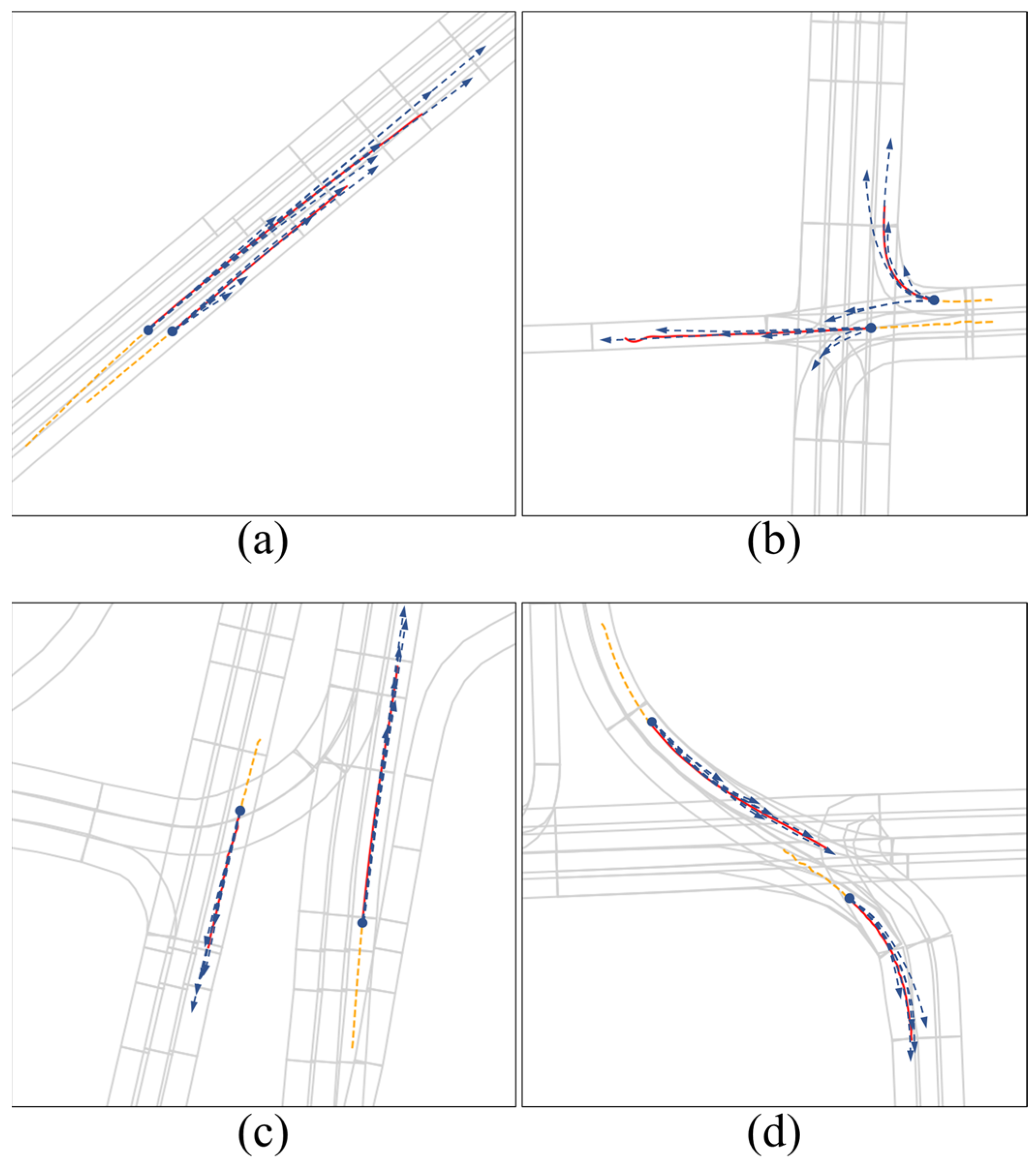

4.4.2. Visualization of Prediction Results

5. Discussion

5.1. Real-Time Feasibility and Deployment Efficiency

5.2. Robustness Under Sensor Noise and Uncertainty

5.3. Practical Implications and Interpretability

5.4. Limitations and Future Work

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| Algorithm A1 PLMT-Net Inference (Four-step Pipeline, per Agent i) |

| 1. 2. 3. Inputs: 4. H_i ← historical trajectory of agent i 5. C_i ← candidate neighbors with histories {H_j} 6. M ← local map features 7. Params ← {W^Q, W^K, W^V, TemporalEncoder, Decoder} 8. Hyperparams ← {a, b, c, α, β, λ} 9. K ← ceil(0.8 × |C_i|) 10. 11. 1) Data vectorization: 12. z_i ← EncAgent(H_i, M) 13. z_ij ← EncPair(H_i, H_j, M) for each j ∈ C_i 14. d_ij, Δv_ij, cosθ_ij ← compute_physical_cues(H_i, H_j) 15. 16. 2) Local encoder (our contributions): 17. // (2a) Physics-aware neighbor formation 18. A_ij = −a·d_ij − b·Δv_ij + c·cosθ_ij // Eq. (4) 19. N_i = TopK_by_value(A_ij, K) // Eq. (5) 20. // (2b) Physics-guided local attention 21. q_i = W^Q·z_i; k_ij = W^K·z_ij; v_ij = W^V·z_ij 22. w_ij = −α·d_ij − β·Δv_ij + λ·cosθ_ij // Eq. (8) 23. ℓ_ij = (q_iT·k_ij)/√d_k + w_ij 24. α_ij = softmax_over_j(ℓ_ij) 25. c_i = Σ_{j∈N_i} α_ij·v_ij 26. // (2c) Temporal modeling 27. h_i = TemporalEncoder(concat(z_i, c_i)) 28. 29. 3) Global interaction: 30. h∼_i = GlobalAggregator({h_*}) 31. 32. 4) Multimodal decoding: 33. {Ŷ_i^(m), π_i^(m)}_{m=1..M} = Decoder(h∼_i) 34. 35. Notes: 36. • TopK reduces local computation from O(|C_i|·d_k) to O(K·d_k). 37. • softmax(x + w) ∝ exp(w)·softmax(x), interpreted as a physics prior on attention. 38. |

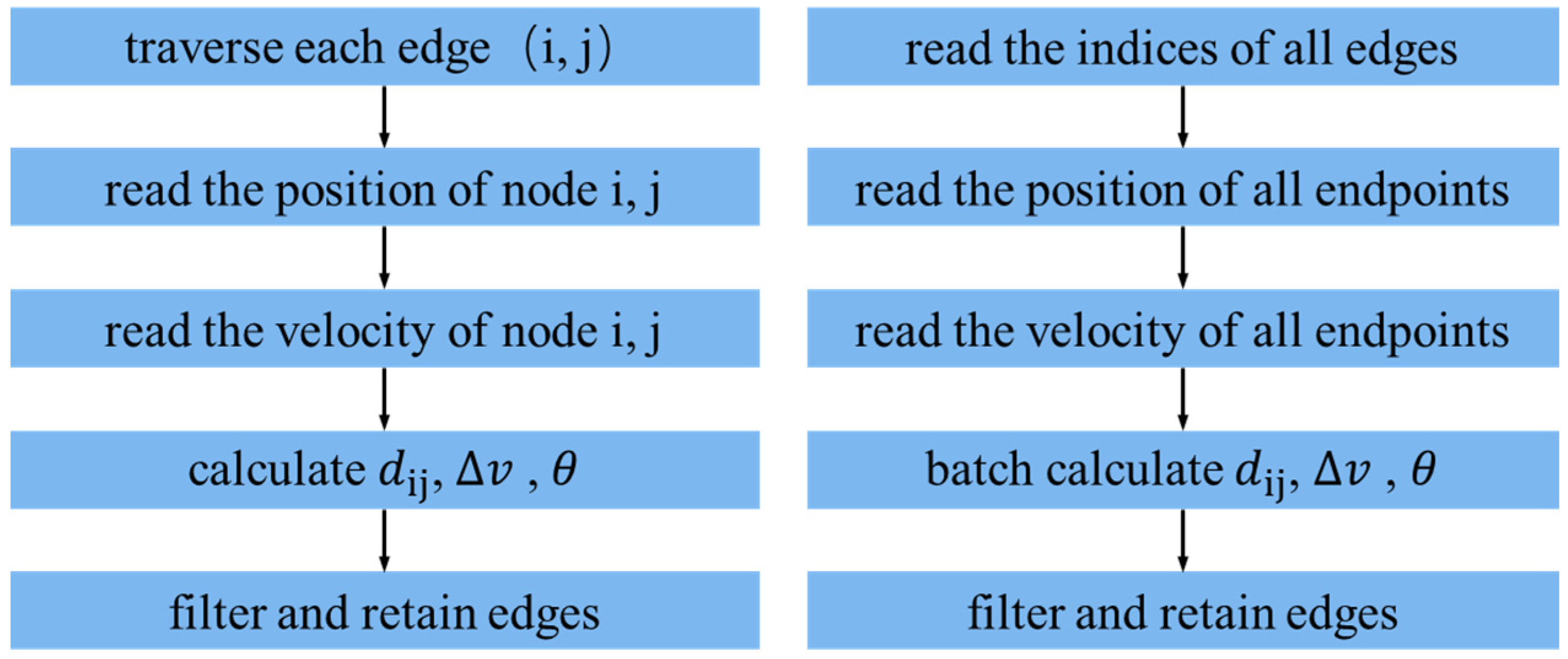

Appendix A.2

| # Loop-based version (simplified) for (i, j) in edges: d = ||pi - pj|| dv = |vi - vj| theta = angle(vec_i, vec_j) score = -a* d - b* dv + c* cos(theta) |

| # Vectorized version (batch processing) pi1, pi2 = positions[row, t], positions[row, t+1] pj1, pj2 = positions[col, t], positions[col, t+1] vi, vj = velocity[row, t], velocity[col, t] d = ||pj1 - pi1|| (batch norm) dv = |vi - vj| (element-wise abs) theta = vectorized_angle(pi2 - pi1, pj2 - pj1) score = -a * d - b* dv + c * cos(theta) |

References

- Huang, Y.; Du, J.; Yang, Z.; Zhou, Z.; Zhang, L.; Chen, H. A survey on trajectory-prediction methods for autonomous driving. IEEE Trans. Intell. Veh. 2022, 7, 652–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Mao, X.; Fang, Y.; Zhu, D.; Meng, M.Q.-H. A survey on deep-learning approaches for vehicle trajectory prediction in autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Biomimetics (ROBIO), Sanya, China, 27–31 December 2021; pp. 978–985. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, X.; Jia, H.; Huang, Q.; Luo, Q.; Wang, N.; Mao, Z. A vehicle driving intention prediction method based on gated dual tower transformer model for autonomous driving. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 285, 128000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Ye, Q.; Candela, E.; Escribano-Macias, J.J.; Hu, B.; Demiris, Y.; Angeloudis, P. Risk-Aware Stochastic Vehicle Trajectory Prediction With Spatial-Temporal Interaction Modeling. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 6, 37–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Guo, J.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, J.; Pu, J. Lane Transformer: A High-Efficiency Trajectory Prediction Model. IEEE Open J. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2023, 4, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Y.; Sapp, B.; Bansal, M.; Anguelov, D. Multipath: Multiple probabilistic anchor trajectory hypotheses for behavior prediction. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1910.05449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, H.; Radosavljevic, V.; Chou, F.-C.; Lin, T.-H.; Nguyen, T.; Huang, T.-K.; Schneider, J.; Djuric, N. Multimodal trajectory predictions for autonomous driving using deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; pp. 2090–2096. [Google Scholar]

- Liang, M.; Yang, B.; Hu, R.; Chen, Y.; Liao, R.; Feng, S.; Urtasun, R. Learning lane graph representations for motion forecasting. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part II 16. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 541–556. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, J.; Sun, C.; Zhao, H.; Shen, Y.; Anguelov, D.; Li, C.; Schmid, C. Vectornet: Encoding hd maps and agent dynamics from vectorized representation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 11525–11533. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Fang, L.; Jiang, Q.; Zhou, B. Multimodal motion prediction with stacked transformers. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 7577–7586. [Google Scholar]

- Mercat, J.; Gilles, T.; El Zoghby, N.; Sandou, G.; Beauvois, D.; Gil, G.P. Multi-head attention for multi-modal joint vehicle motion forecasting. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 9638–9644. [Google Scholar]

- Ye, M.; Cao, T.; Chen, Q. Tpcn: Temporal point cloud networks for motion forecasting. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 11318–11327. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Z.; Ye, L.; Wang, J.; Wu, K.; Lu, K. Hivt: Hierarchical vector transformer for multi-agent motion prediction. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 8823–8833. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, M.; Qu, X.; Li, X. A recurrent neural network based microscopic car following model to predict traffic oscillation. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2017, 84, 245–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savarese, S. Social lstm: Human trajectory prediction in crowded spaces. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 961–971. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, A.; Johnson, J.; Fei-Fei, L.; Savarese, S.; Alahi, A. Social gan: Socially acceptable trajectories with generative adversarial networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–22 June 2018; pp. 2255–2264. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Z.; Tomizuka, M. Social-wagdat: Interaction-aware trajectory prediction via wasserstein graph double-attention network. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2002.06241. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Ying, X.; Chuah, M.C. Grip++: Enhanced graph-based interaction-aware trajectory prediction for autonomous driving. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.07792. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, N.; Choi, W.; Vernaza, P.; Choy, C.B.; Torr, P.H.; Chandraker, M. Desire: Distant future prediction in dynamic scenes with interacting agents. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 336–345. [Google Scholar]

- Sadeghian, A.; Kosaraju, V.; Sadeghian, A.; Hirose, N.; Rezatofighi, H.; Savarese, S. Sophie: An attentive gan for predicting paths compliant to social and physical constraints. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 1349–1358. [Google Scholar]

- Chandra, R.; Guan, T.; Panuganti, S.; Mittal, T.; Bhattacharya, U.; Bera, A.; Manocha, D. Forecasting trajectory and behavior of road-agents using spectral clustering in graph-lstms. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2020, 5, 4882–4890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mozaffari, S.; Al-Jarrah, O.Y.; Dianati, M.; Jennings, P.; Mouzakitis, A. Deep learning-based vehicle behavior prediction for autonomous driving applications: A review. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 23, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raissi, M.; Perdikaris, P.; Karniadakis, G. Physics-informed neural networks: A deep learning framework for solving forward and inverse problems involving nonlinear partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 378, 686–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Liao, Z.; Rui, Y.; Li, L.; Ran, B. A physical law constrained deep learning model for vehicle trajectory prediction. IEEE Internet Things J. 2023, 10, 22775–22790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salzmann, T.; Ivanovic, B.; Chakravarty, P.; Pavone, M. Trajectron++: Dynamically-feasible trajectory forecasting with heterogeneous data. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision–ECCV 2020: 16th European Conference, Glasgow, UK, 23–28 August 2020; Proceedings, Part XVIII 16. Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 683–700. [Google Scholar]

- Westerhout, F.S.; Schumann, J.F.; Zgonnikov, A. Smooth-Trajectron++: Augmenting the Trajectron++ behaviour prediction model with smooth attention. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 26th International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC), Bilbao, Spain, 24–28 September 2023; pp. 5423–5428. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Zhao, B.; Hu, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, X. Multi-Modal Vehicle Motion Prediction Based on Motion-Query Social Transformer Network for Internet of Vehicles. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 28864–28875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.; Mo, X.; Lv, C. Multi-modal motion prediction with transformer-based neural network for autonomous driving. In Proceedings of the 2022 International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Philadelphia, PA, USA, 23–27 May 2022; pp. 2605–2611. [Google Scholar]

- Hinton, G.; Vinyals, O.; Dean, J. Distilling the knowledge in a neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1503.02531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Pool, J.; Tran, J.; Dally, W. Learning both weights and connections for efficient neural network. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1506.02626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, A.G.; Zhu, M.; Chen, B.; Kalenichenko, D.; Wang, W.; Weyand, T.; Andreetto, M.; Adam, H. Mobilenets: Efficient convolutional neural networks for mobile vision applications. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.04861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandler, M.; Howard, A.; Zhu, M.; Zhmoginov, A.; Chen, L.-C. Mobilenetv2: Inverted residuals and linear bottlenecks. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 4510–4520. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, A.; Sandler, M.; Chu, G.; Chen, L.-C.; Chen, B.; Tan, M.; Wang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Pang, R.; Vasudevan, V. Searching for mobilenetv3. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 1314–1324. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, J.; Li, H.; Zhang, Q. Trajectory Prediction for V2X Collision Warning Using Pruned Transformer Model. In Proceedings of the 2024 6th International Conference on Intelligent Control, Measurement and Signal Processing (ICMSP), Xi’an, China, 29 November–1 December 2024; pp. 549–556. [Google Scholar]

- Shaw, P.; Uszkoreit, J.; Vaswani, A. Self-attention with relative position representations. Assoc. Comput. Linguist. 2018, 2, 464–468. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, NAACL-HLT 2019, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Chang, M.-F.; Lambert, J.; Sangkloy, P.; Singh, J.; Bak, S.; Hartnett, A.; Wang, D.; Carr, P.; Lucey, S.; Ramanan, D. Argoverse: 3d tracking and forecasting with rich maps. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 8748–8757. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, J.; Sun, C.; Zhao, H. Densetnt: End-to-end trajectory prediction from dense goal sets. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Montreal, BC, Canada, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 15303–15312. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, X.; Jia, X.; Li, Y.; Xiong, H. Dynamic scenario representation learning for motion forecasting with heterogeneous graph convolutional recurrent networks. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 2946–2953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Screening Strategy | minADE | minFDE | MR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-K Selection (80%) | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.09 |

| Top-K Selection (70%) | 0.68 | 1.03 | 0.10 |

| Top-K Selection (90%) | 0.67 | 1.03 | 0.10 |

| Min-score Thresholding | 0.69 | 1.03 | 0.10 |

| Model | minADE | minFDE | MR |

|---|---|---|---|

| Full Model | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.09 |

| w/o Physics in Selection | 0.68 | 1.03 | 0.09 |

| w/o Physics in Attention | 0.69 | 1.03 | 0.10 |

| w/o Physics Overall | 0.69 | 1.04 | 0.10 |

| A-A | Temporal | A-L | Global | minADE | minFDE | MR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| √ | √ | √ | 0.71 | 1.07 | 0.11 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 0.87 | 1.40 | 0.17 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 0.77 | 1.21 | 0.13 | |

| √ | √ | √ | 0.71 | 1.09 | 0.11 | |

| √ | √ | √ | √ | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.09 |

| Setting (Batch) | Per-Batch Latency (ms) | Per-Sample Latency (ms) | Throughput (Samples/s) | Peak VRAM Allocated (MB) | Peak VRAM Reserved (MB) | Device |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLMT-Net (bs = 1) | 60.6 | 60.6 | 16.51 | 68.4 | 92.0 | RTX 3090 (24 GB) |

| PLMT-Net (bs = 8) | 123.2 | 15.4 | 64.93 | 224.0 | 436.0 | RTX 3090 (24 GB) |

| Model | minADE | minFDE | MR | # Param | Latency (ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PLMT-Net | 0.67 | 1.02 | 0.09 | 652K | 60.6 |

| HiVT | 0.69 | 1.04 | 0.10 | 662K | 49.4 |

| LaneGCN | 0.71 | 1.08 | 0.10 | 3701K | 55.32 |

| DenseTNT | 0.75 | 1.05 | 0.10 | 1103K | 138.59 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, W.; Liu, F.; Liu, H.; Chen, M.; Zhao, L. PLMT-Net: A Physics-Aware Lightweight Network for Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction in Interactive Driving Scenarios. Drones 2025, 9, 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120826

Yu W, Liu F, Liu H, Chen M, Zhao L. PLMT-Net: A Physics-Aware Lightweight Network for Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction in Interactive Driving Scenarios. Drones. 2025; 9(12):826. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120826

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Wan, Fuyun Liu, Huiqi Liu, Ming Chen, and Liangliang Zhao. 2025. "PLMT-Net: A Physics-Aware Lightweight Network for Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction in Interactive Driving Scenarios" Drones 9, no. 12: 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120826

APA StyleYu, W., Liu, F., Liu, H., Chen, M., & Zhao, L. (2025). PLMT-Net: A Physics-Aware Lightweight Network for Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction in Interactive Driving Scenarios. Drones, 9(12), 826. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9120826