Agaricus sinodeliciosus and Coprinus comatus Improve Soil Fertility and Microbial Community Structure

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Determination of Soil Physiochemical Properties

2.3. Metagenomic Data Analysis

2.3.1. Data Assembly

2.3.2. Analysis of Microbial Composition

2.3.3. Analysis of Microbial Diversity

2.3.4. Key Differential Microorganism Discovery

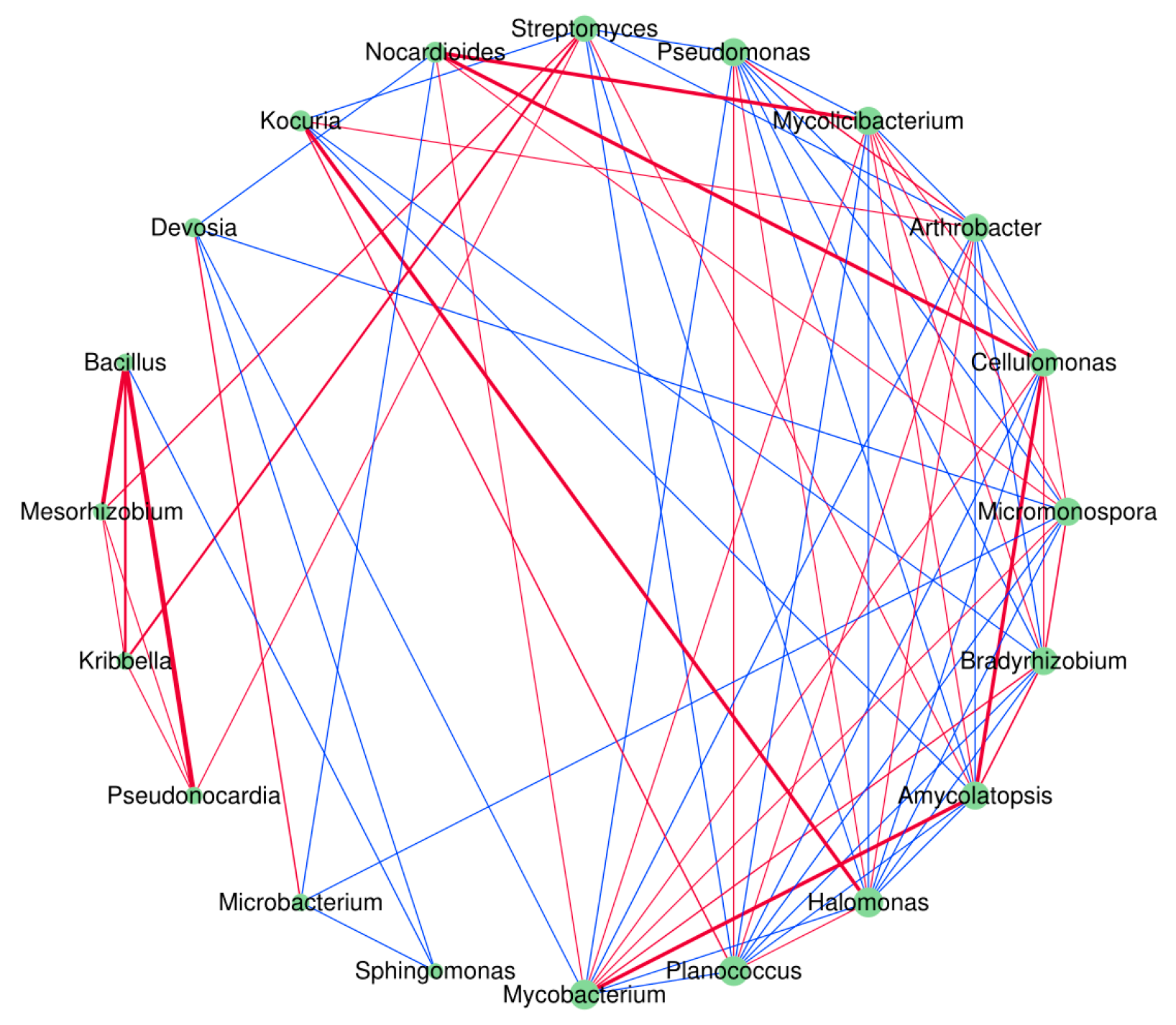

2.3.5. Analysis of Microbial Symbiotic Networks

2.3.6. Statistical Analyses

2.3.7. AI-Assisted Language and Structural Polishing

3. Results

3.1. The Effects of A. sinodeliciosus and C. comatus on Soil Physicochemical Properties

| Physicochemical Properties | WT | DFG | JT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water content (W, %) | 5.71 ± 0.76 a | 7.92 ± 0.62 b | 6.38 ± 0.15 a |

| Electrical conductivity (E, µS/cm) | 1638.67 ± 145.65 a | 22.43 ± 0.81 b | 5.45 ± 0.54 b |

| pH | 7.93 ± 0.55 a | 8.75 ± 0.26 b | 7.62 ± 0.93 c |

| Total carbon (TC, g/kg) | 25.22 ± 1.20 a | 32.15 ± 2.28 b | 53.78 ± 1.44 c |

| Total nitrogen (TN, g/kg) | 1.86 ± 0.21 a | 3.63 ± 0.14 b | 3.87 ± 0.17 b |

| Hydrolyzable nitrogen (HN, mg/kg) | 162.31 ± 30.02 a | 304.10 ± 19.77 b | 321.21 ± 11.93 b |

| Available phosphorus (AP, mg/kg) | 8.22 ± 1.49 a | 8.80 ± 1.64 a | 21.63 ± 2.00 b |

| Available potassium (AK, mg/kg) | 382.02 ± 9.35 a | 1080.02 ± 32.60 b | 2659.19 ± 112.87 c |

| Total salt (TSalt, g/kg) | 16.30 ± 3.04 a | 126.37 ± 2.74 b | 34.18 ± 11.37 c |

3.2. Effects of A. sinodeliciosus and C. comatus on Soil Microorganisms

3.2.1. Effects on Soil Microbial Content

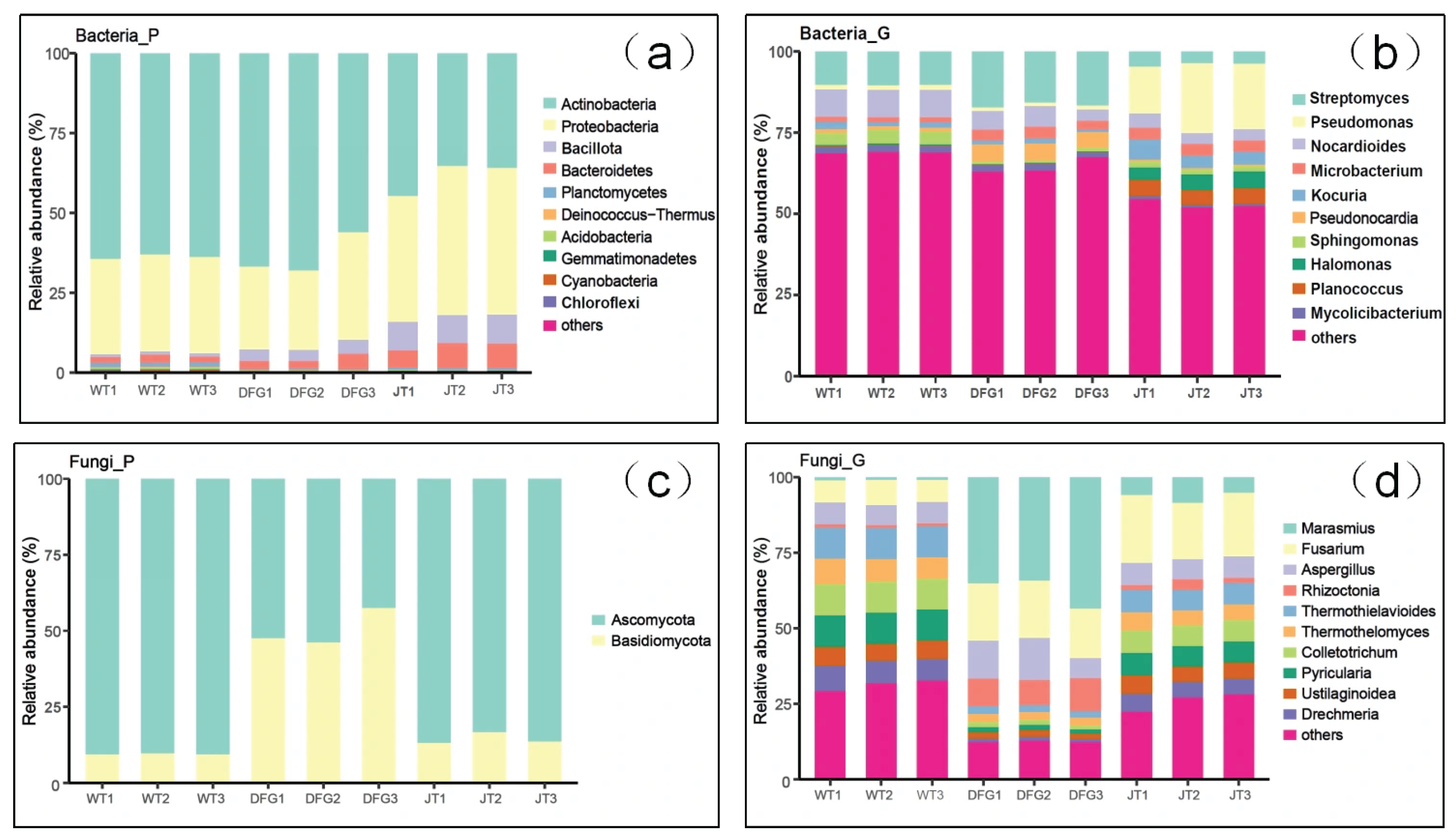

3.2.2. Effects on Soil Microbial Composition

3.2.3. Effects on Soil Microbial Diversity

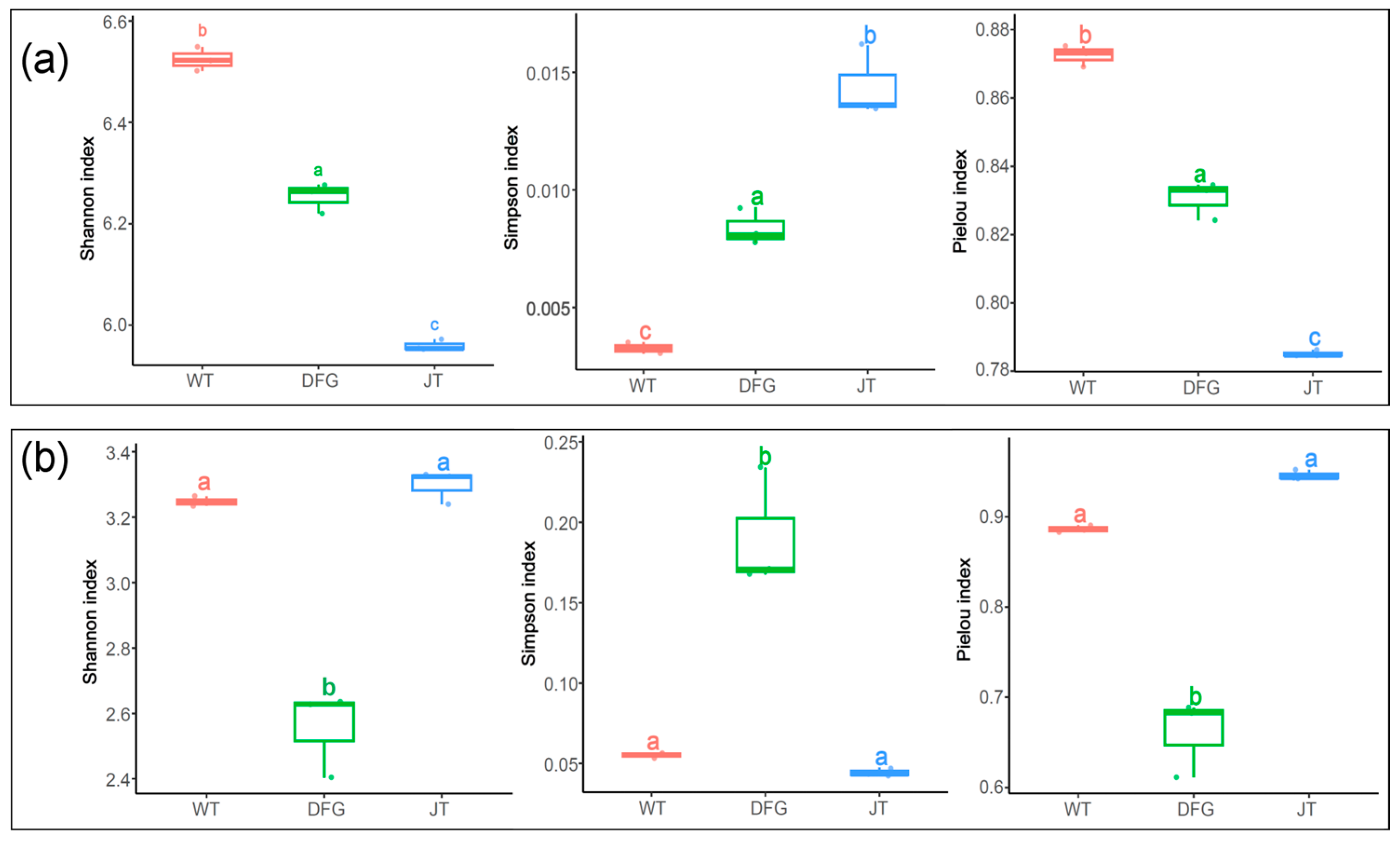

- (1)

- Alpha diversity analysis

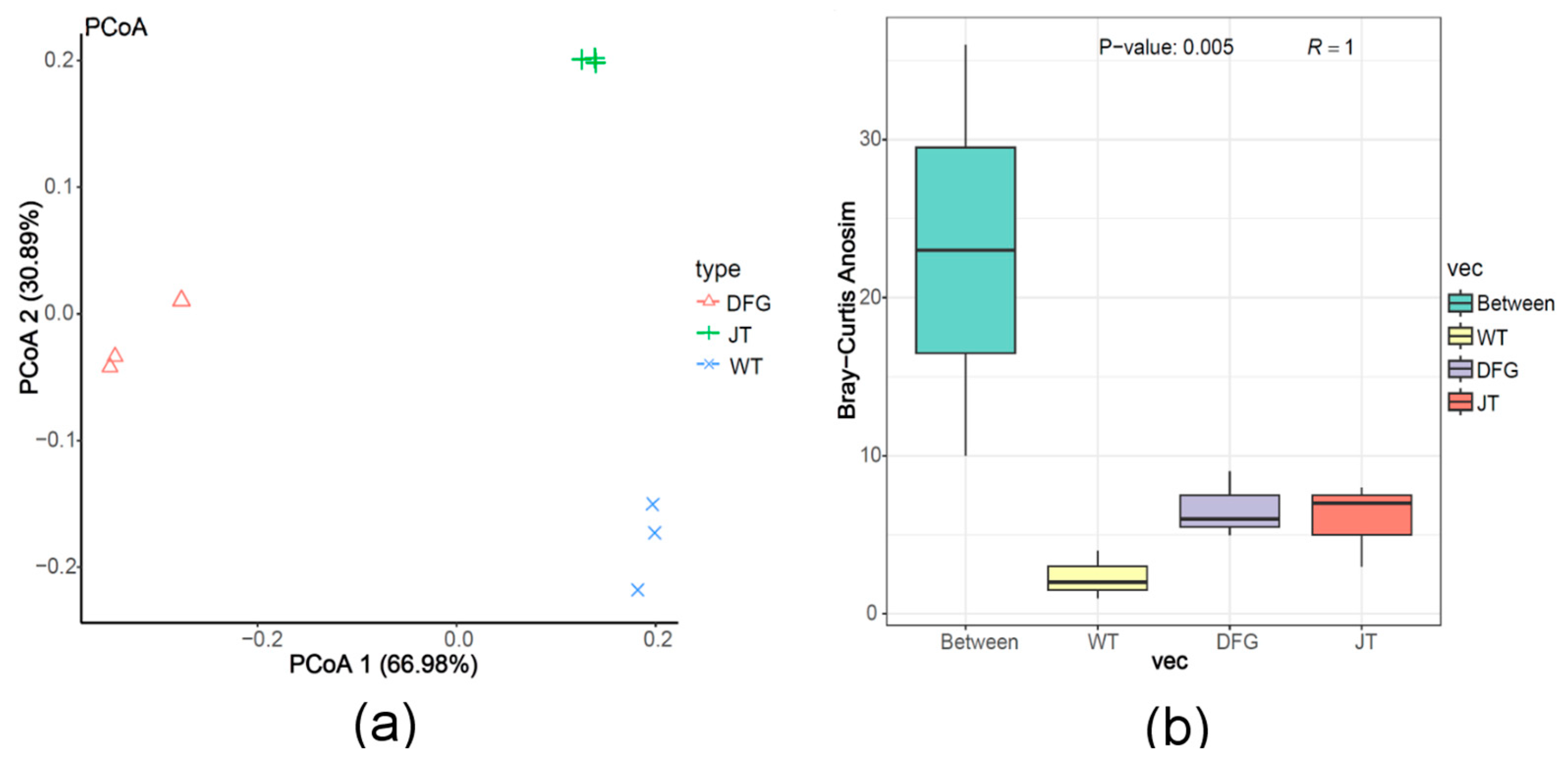

- (2)

- Beta diversity analysis

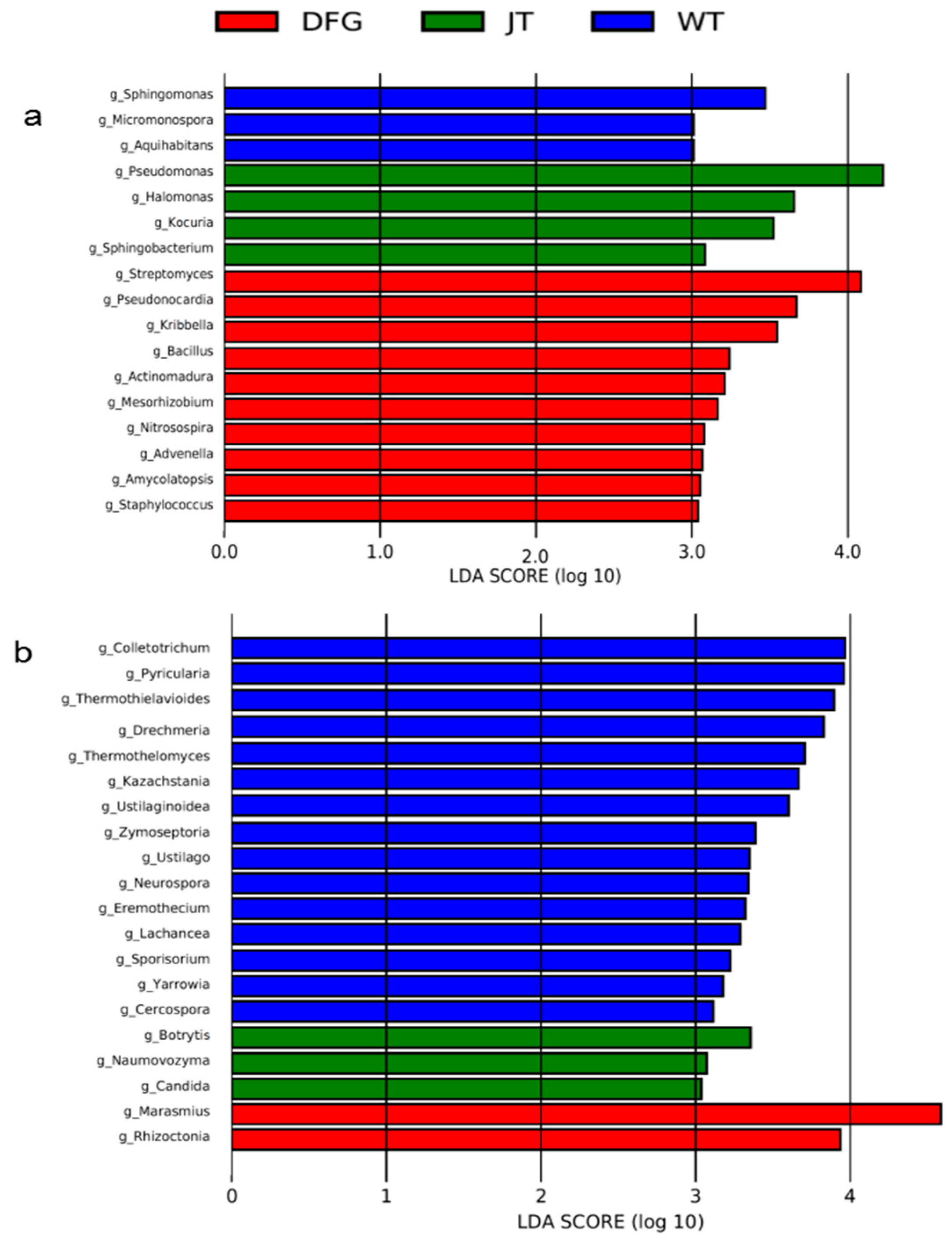

3.2.4. Marker Microbial Analysis

3.3. Soil Microbial Correlation Analysis

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between Soil Microorganisms and Physicochemical Properties

4. Discussion

4.1. Macrofungi Enhance Soil Fertility

4.2. Macrofungi Reshape Soil Microbial Communities

4.3. Coupling Relationship Between Microorganisms and Physicochemical Properties

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DFG | Agaricus sinodeliciosus, called “Da Fei Gu” in China |

| JT | Coprinus comatus, called “Ji Tui Gu” in China |

| WT | The control |

| TC | Total carbon |

| TN | Total nitrogen |

| HN | Hydrolyzable nitrogen |

| AP | Available phosphorus |

| AK | Available potassium |

| TSalt | Total salt |

References

- Huang, S.-S.; Liu, H.; Li, X.-F.; Wang, C.-Y.; Zhang, X.; Wang, J.-J.; Song, F.; Bao, J.; Zhang, H. Exploring the Biodiversity and Antibacterial Potential of the Culturable Soil Fungi in Nyingchi, Tibet. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, M.; Liu, F.; Sun, L.; Wang, Y.; Wan, J.; Wang, R.; Zhou, H.; Wang, W.; Xu, J. Floccularia luteovirens modulates the growth of alpine meadow plants and affects soil metabolite accumulation on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Plant Soil 2021, 459, 125–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Lu, H.; Zhang, X.; Chen, Q. The Genomic and Transcriptomic Analyses of Floccularia luteovirens, a Rare Edible Fungus in the Qinghai—Tibet Plateau, Provide Insights into the Taxonomy Placement and Fruiting Body Formation. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Gao, Q.B.; Zhang, F.Q.; Fu, P.C.; Wang, J.L.; Yan, H.Y.; Chen, S.L. Genetic variation and phylogenetic relationships of the ectomycorrhizal Floccularia luteovirens on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Microbiol. 2017, 55, 600–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ling, Z.L.; Cao, B.; Hu, S.N.; Geng, J.N.; Liu, F.; Liu, D.M.; Zhao, R.L. Insights into the genomic evolution and the alkali tolerance mechanisms of Agaricus sinodeliciosus by comparative genomic and transcriptomic analyses. Microb. Genom. 2023, 9, 000928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Bai, X.; Zhao, R. Microbial communities in the native habitats of Agaricus sinodeliciosus from Xinjiang Province revealed by amplicon sequencing. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 15719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowakowski, P.; Naliwajko, S.K.; Markiewicz-Żukowska, R.; Borawska, M.H.; Socha, K. The two faces of Coprinus comatus—Functional properties and potential hazards. Phytother. Res. 2020, 34, 2932–2944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stojković, D.; Reis, F.S.; Barros, L.; Glamočlija, J.; Ćirić, A.; van Griensven, L.J.; Soković, M.; Ferreira, I.C. Nutrients and non-nutrients composition and bioactivity of wild and cultivated Coprinus comatus (OF Müll.) Pers. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 59, 289–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, J.J.; Zhao, G.P.; Tuo, Y.L.; Qi, Z.X.; Yue, L.; Zhang, B.; Li, Y. Ecological factors influencing the occurrence of macrofungi from eastern mountainous areas to the central plains of Jilin province, China. J. Fungi 2022, 8, 871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilich, M.A.; Wieters, E.; Broitman, B.R.; Marquet, P.A.; Navarrete, S.A. Species co-occurrence networks: Can they reveal trophic and non-trophic interactions in ecological communities? Ecology 2018, 99, 690–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freilich, S.; Kreimer, A.; Meilijson, I.; Gophna, U.; Sharan, R.; Ruppin, E. The large-scale organization of the bacterial network of ecological co-occurrence interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010, 38, 3857–3868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, M.; Wei, Y.; Lian, L.; Wei, B.; Bi, Y.; Liu, N.; Yang, G.; Zhang, Y. Macrofungi promote SOC decomposition and weaken sequestration by modulating soil microbial function in temperate steppe. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 899, 165556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Y.; Lin, X.; Zhang, J.; Zeng, J. Dissipation of polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in soil microcosms amended with mushroom cultivation substrate. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2012, 47, 191–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Y.; Mortimer, P.E.; Hyde, K.D.; Kakumyan, P.; Thongklang, N. Mushroom cultivation for soil amendment and bioremediation. Circ. Agric. Syst. 2021, 1, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, R.; Zhang, H.C.; Gao, Q.B.; Zhang, F.Q.; Chi, X.F.; Chen, S.L. Bacterial communities associated with mushrooms in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau are shaped by soil parameters. Int. Microbiol. 2023, 26, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Shi, X.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, W. Dynamics of soil microbiome throughout the cultivation life cycle of morel (Morchella sextelata). Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 979835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, J.; He, C.; Wang, F.; Ling, N.; Jiang, S. Habitat-specific changes of plant and soil microbial community composition in response to fairy ring fungus Agaricus xanthodermus on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2024, 6, 230214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Jolivet, M.; Guo, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, C.; Li, X. Cenozoic evolution of the Qaidam basin and implications for the growth of the northern Tibetan plateau: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 220, 103730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, F.; Kong, W.; Xu, W. Edaphic characterization and plant zonation in the Qaidam Basin, Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, Q.; Riegel, H.; Gong, L.; Heermance, R.; Nie, J. Detailed processes and potential mechanisms of pliocene salty lake evolution in the Western Qaidam basin. Front. Earth Sci. 2021, 9, 736901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hui, R.; Tan, H.; Li, X.; Wang, B. Variation of soil physical-chemical characteristics in salt-affected soil in the Qarhan Salt Lake, Qaidam Basin. J. Arid Land 2022, 14, 341–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, C.; Wei, Y.; Yao, W.; Lei, Y.; Sun, Y. Soil microbes drive the flourishing growth of plants from Leucocalocybe mongolica fairy ring. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 893370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, Q.; Liu, J.; Yu, Z.; Li, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, G. Three years of biochar amendment alters soil physiochemical properties and fungal community composition in a black soil of northeast China. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2017, 110, 56–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.L.; Willett, V.B. Experimental evaluation of methods to quantify dissolved organic nitrogen (DON) and dissolved organic carbon (DOC) in soil. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2006, 38, 991–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Yi, Q.; Gao, D.; Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Wang, K.; Xiao, D.; Hu, P.; Zhao, J. Soil micro-food web composition determines soil fertility and crop growth. Soil Ecol. Lett. 2025, 7, 240264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hereira-Pacheco, S.; Arias-Del Razo, I.; Miranda-Carrazco, A.; Dendooven, L.; Estrada-Torres, A.; Navarro-Noya, Y.E. Metagenomic analysis of fungal assemblages at a regional scale in high-altitude temperate forest soils: Alternative methods to determine diversity, composition and environmental drivers. PeerJ 2025, 13, e18323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Wang, X.; Wang, X.; Liu, X. Changes in microbial community succession and volatile compounds during the natural fermentation of bangcai. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1581378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galanova, O.O.; Mitkin, N.A.; Danilova, A.A.; Pavshintsev, V.V.; Tsybizov, D.A.; Zakharenko, A.M.; Golokhvast, K.S.; Grigoryeva, T.V.; Markelova, M.I.; Vatlin, A.A. Assessment of Soil Health Through Metagenomic Analysis of Bacterial Diversity in Russian Black Soil. Microorganisms 2025, 13, 854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, S.; Wang, M.; Dong, X.; Ji, Y.; Wu, H.; Koski, T.M.; Wang, M.; Li, Q. Shifts in soil microbial and nematode communities over progression of pine wilt disease occurring in Pinus koraiensis stands. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1634289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, L.; Wang, W.; Chen, Z.; Chen, X.; Xiong, Y. The Variations in Soil Microbial Communities and Their Mechanisms Along an Elevation Gradient in the Qilian Mountains, China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 1797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ren, G.; Shi, W.; Li, W.; Wang, C.; Zhao, G. Pyrolysis temperature shapes biochar-mediated soil microbial communities and carbon-nitrogen metabolism. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1657149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zou, X.; Yao, K.; Zeng, Z.; Zeng, F.; Lu, L.; Zhang, H. Effect of different vegetation restoration patterns on community structure and co-occurrence networks of soil fungi in the karst region. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1440951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, Q.; Yang, J.; Chen, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, C. Rice-edible mushroom Stropharia rugosoannulata rotation mitigates net global warming potential while enhancing soil fertility and economic benefits. Eur. J. Agron. 2025, 164, 127521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, E.; Paredes, C.; Bustamante, M.A.; Moral, R.; Moreno-Caselles, J. Relationships between soil physico-chemical, chemical and biological properties in a soil amended with spent mushroom substrate. Geoderma 2012, 173, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, M.I.; Mujawar, L.H.; Shahzad, T.; Almeelbi, T.; Ismail, I.M.; Oves, M. Bacteria and fungi can contribute to nutrients bioavailability and aggregate formation in degraded soils. Microbiol. Res. 2016, 183, 26–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, P.; Yu, F.; Perez-Moreno, J. Macrofungi cultivation in shady forest areas significantly increases microbiome diversity, abundance and functional capacity in soil furrows. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Familoni, T.V.; Ogidi, C.O.; Akinyele, B.J.; Onifade, A.K. Genetic diversity, microbiological study and composition of soil associated with wild Pleurotus ostreatus from different locations in Ondo and Ekiti States, Nigeria. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2018, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dou, T.; Zhang, K.; Shi, X.; Liu, W.; Yu, F.; Liu, D. Crop—Mushroom Rotation: A Comprehensive Review of Its Multifaceted Impacts on Soil Quality, Agricultural Sustainability, and Ecosystem Health. Agronomy 2025, 15, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGee, C.F. Microbial ecology of the Agaricus bisporus mushroom cropping process. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 1075–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabel, M.A.; Jurak, E.; Mäkelä, M.R.; de Vries, R.P. Occurrence and function of enzymes for lignocellulose degradation in commercial Agaricus bisporus cultivation. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 4363–4369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, N.A.; Kumar, J.; Wani, M.S.; Tantray, Y.R.; Ahmad, T. Role of Mushrooms in the Bioremediation of Soil. In Microbiota and Biofertilizers; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 2, pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Niu, G. Genomics-driven natural product discovery in actinomycetes. Trends Biotechnol. 2018, 36, 238–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amorim, E.A.D.F.; Castro, E.J.M.; da Souza, S.V.; Alves, M.S.; Dias, L.R.L.; Melo, M.H.F.; da Silva, I.M.A.; Villis, P.C.M.; Bonfim, M.R.Q.; Falcai, A.; et al. Antimicrobial potential of Streptomyces ansochromogenes (PB3) isolated from a plant native to the amazon against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 574693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chouyia, F.E.; Ventorino, V.; Pepe, O. Diversity, mechanisms and beneficial features of phosphate-solubilizing Streptomyces in sustainable agriculture: A review. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1035358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thai, M.; Safianowicz, K.; Bell, T.L.; Kertesz, M.A. Dynamics of microbial community and enzyme activities during preparation of Agaricus bisporus compost substrate. ISME Commun. 2022, 2, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ke, L.Q.; Li, P.D.; Xu, J.P.; Wang, Q.S.; Wang, L.L.; Wen, H.P. Microbial communities and soil chemical features associated with commercial production of the medicinal mushroom Ganoderma lingzhi in soil. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 15839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-M.; Yao, H.-Y.; Feng, W.-L.; Jin, Q.-L.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Li, N.-Y.; Zheng, Z. Microbial community structure of casing soil during mushroom growth. Pedosphere 2009, 19, 446–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaario, L.M.; Fritze, H.; Spetz, P.; Heinonsalo, J.; Hanajík, P.; Pennanen, T. Tricholoma matsutake dominates diverse microbial communities in different forest soils. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 8523–8531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, W.; Wang, J.; Jin, Q.; Guo, Z.; Cai, W. Analysis of Soil Fungal Community Characteristics of Morchella sextelata Under Different Rotations and Intercropping Patterns and Influencing Factors. Agriculture 2025, 15, 823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oakley, B.B.; Carbonero, F.; Van Der Gast, C.J.; Hawkins, R.J.; Purdy, K.J. Evolutionary divergence and biogeography of sympatric niche-differentiated bacterial populations. ISME J. 2010, 4, 488–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshru, B.; Fallah Nosratabad, A.; Mahjenabadi, V.A.; Knežević, M.; Hinojosa, A.C.; Fadiji, A.E.; Enagbonma, B.J.; Qaderi, S.; Patel, M.; Baktash, E.M.; et al. Multidimensional role of Pseudomonas: From biofertilizers to bioremediation and soil ecology to sustainable agriculture. J. Plant Nutr. 2025, 48, 1016–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hayat, R.; Ali, S.; Amara, U.; Khalid, R.; Ahmed, I. Soil beneficial bacteria and their role in plant growth promotion: A review. Ann. Microbiol. 2010, 60, 579–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rath, K.M.; Maheshwari, A.; Bengtson, P.; Rousk, J. Comparative toxicities of salts on microbial processes in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 2012–2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, H.; Wang, S.; Gao, Z.; Pan, H.; Zhuge, Y.; Ren, X.; Hu, S.; Li, C. Aggregate stability and organic carbon stock under different land uses integrally regulated by binding agents and chemical properties in saline-sodic soils. Land Degrad. Dev. 2021, 32, 4151–4161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrasco, J.; Preston, G.M. Growing edible mushrooms: A conversation between bacteria and fungi. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 858–872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, S.; Liu, L.; Ding, X. Influence of organic fertilization on clay mineral transformation and soil phosphorous retention: Evidence from an 8-year fertilization experiment. Soil Tillage Res. 2023, 230, 105702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.Y.; Zhu, C.L.; Yu, J.B.; Wu, X.Y.; Huang, S.Q.; Yang, F.; Tigabu, M.; Hou, X.L. Response of soil bacteria of Dicranopteris dichotoma populations to vegetation restoration in red soil region of China. J. Soil Sci. Plant Nutr. 2023, 23, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.; Shi, G.; Zhang, Q.; Meng, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Jiang, S.; Zhou, G.; Feng, H. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi serve as keystone taxa for revegetation on the Tibetan Plateau. J. Basic Microbiol. 2019, 59, 609–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Q.; Xie, Z.; Tang, G.; Jiang, H.; Guo, J.; Mao, Y.; Wang, B.; Meng, Q.; Yang, J.; Jia, S.; et al. Fungal community composition and function in different spring rapeseeds on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, China. Plant Soil 2024, 503, 659–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | WT | DFG | JT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective sequence (reads) | 40,100,457.67 ± 24,815.72 a | 40,075,380.67 ± 56,909.47 a | 40,092,891.33 ± 12,338.52 a |

| Effective sequence (%) | 28.87 ± 0.31 a | 36.03 ± 1.62 b | 38.03 ± 0.45 b |

| Unknown species sequences (%) | 71.13 ± 0.31 a | 63.97 ± 1.62 b | 61.97 ± 0.45 b |

| Microbial sequences (%) | 28.87 ± 0.31 a | 36.03 ± 1.62 b | 38.00 ± 0.4 b |

| Bacterial sequence (%) | 28.33 ± 0.25 a | 35.67 ± 1.63 b | 37.33 ± 0.45 b |

| Fungal sequence (%) | 0.02 ± 0.06 a | 0.13 ± 0.02 b | 0.02 ± 0.06 a |

| viral sequence (%) | 0.01 ± 0.00 a | 0.03 ± 0.01 b | 0.01 ± 0.00 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lv, X.; Wang, H.; Wang, W. Agaricus sinodeliciosus and Coprinus comatus Improve Soil Fertility and Microbial Community Structure. J. Fungi 2025, 11, 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120866

Lv X, Wang H, Wang W. Agaricus sinodeliciosus and Coprinus comatus Improve Soil Fertility and Microbial Community Structure. Journal of Fungi. 2025; 11(12):866. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120866

Chicago/Turabian StyleLv, Xinxia, Hengsheng Wang, and Wenying Wang. 2025. "Agaricus sinodeliciosus and Coprinus comatus Improve Soil Fertility and Microbial Community Structure" Journal of Fungi 11, no. 12: 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120866

APA StyleLv, X., Wang, H., & Wang, W. (2025). Agaricus sinodeliciosus and Coprinus comatus Improve Soil Fertility and Microbial Community Structure. Journal of Fungi, 11(12), 866. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof11120866