1. Introduction

Since its discovery in Japan in 2009 [

1],

Candidozyma auris (formerly known as

Candida auris) [

2] has emerged as a serious global health concern. In fact, in 2022 the World Health Organization (WHO) included this yeast in the critical group of the fungal priority pathogens list [

3]. One of the most alarming traits is its significant multi-drug resistance to antifungal agents, with some strains being resistant to all available antifungal treatments against systemic candidiasis, also known as panresistant clinical isolates [

4]. Furthermore, its ability to persist on both abiotic and biotic surfaces facilitates outbreaks in healthcare settings, where it can easily spread among immunocompromised patients [

5,

6]. Additionally, it is often misidentified in clinical laboratories, delaying accurate diagnosis and treatment [

7]. All of these characteristics contribute to the high mortality of hospital-associated infections caused by this yeast, which can reach up to 60% [

8].

Currently, there are only four classes of antifungal agents available for treating invasive candidiasis, with resistance observed against each class in

C. auris. Consequently, there is an urgent need for novel treatments to address infections caused by this species [

4]. In this context, monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) constitute a promising therapeutic option for candidiasis and other fungal infections, either on their own or in combination with existing antifungal agents [

9].

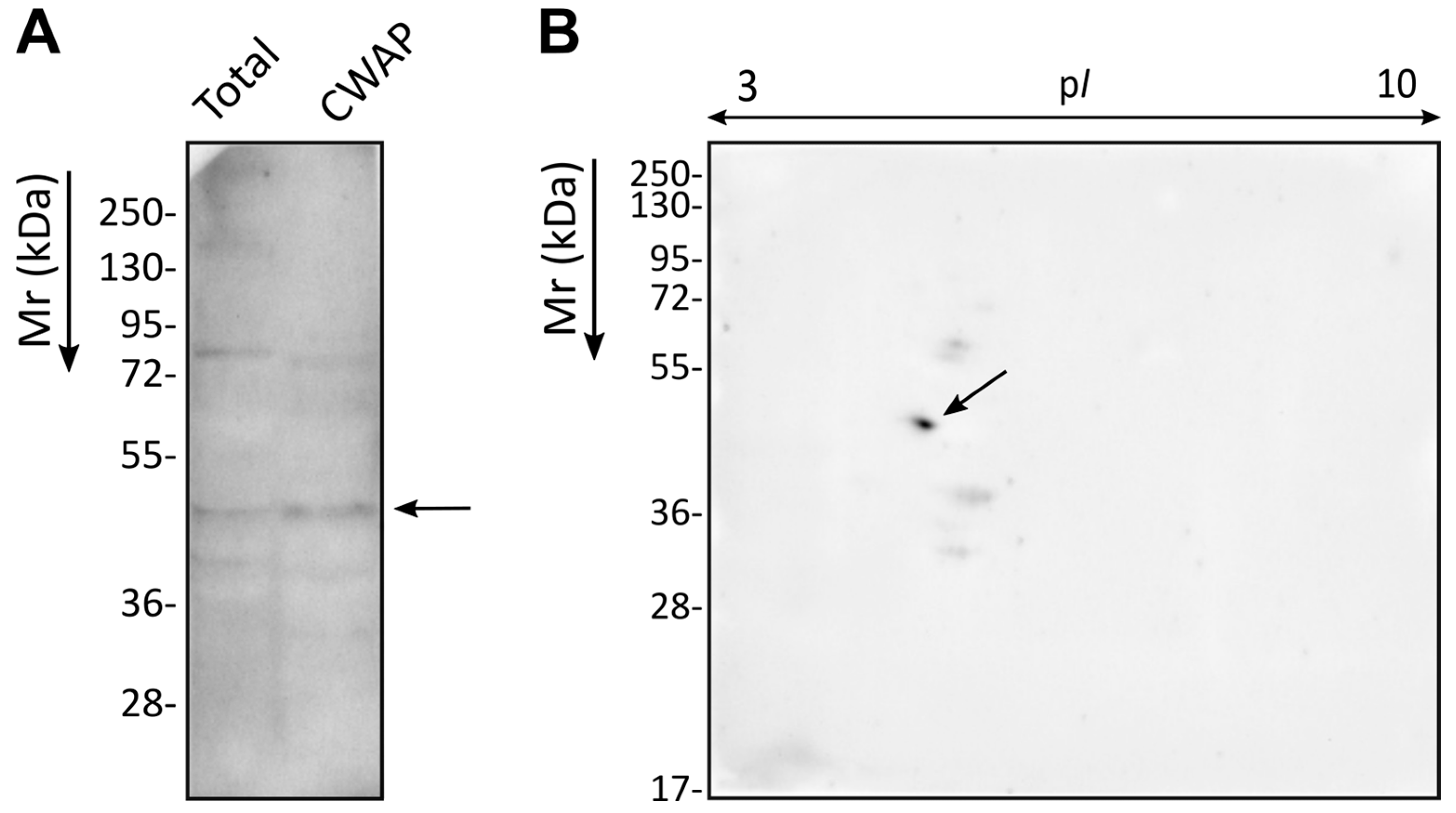

Previously, our research group developed the IgG1 Ca37 monoclonal antibody against the

Candida albicans alcohol dehydrogenase 1 (Adh1), a cytosolic and cell wall-associated protein (CWAP) that not only plays a metabolic role but also functions as an antigen and allergen [

10]. Moreover, it may even act as an adhesin by binding to fibronectin [

10] and serum plasminogen of the host [

11]. Indeed, the Ca37 mAb demonstrated antifungal efficacy against

C. albicans in vitro and in vivo in the

Galleria mellonella animal model [

12].

It is worth highlighting that

C. albicans Adh has low homology with the human protein [

12], but is highly conserved among different species of

Candida and related genera, which makes it an interesting therapeutic target. In fact, the Ca37 mAb also showed reactivity against

Candida parapsilosis,

Nakaseomyces glabratus (formerly

Candida glabrata), and

C. auris [

12]. Specifically, in the case of the

C. auris Adh, the homology with

C. albicans Adh1 protein is 80% as confirmed by BLAST analysis “

https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi (accessed on 19 September 2025)”.

Therefore, given the reduced availability of effective treatments against C. auris and the potential activity that the Ca37 mAb could also have against this species, the aim of this work was to evaluate the effect of the Ca37 mAb on C. auris both in vitro and in vivo. First, we examined the immunoreactivity of Ca37 mAb against C. auris cell wall-associated proteins. We then characterised its in vitro activity by assessing fungal growth inhibition after 18 h and the potential opsonisation effect using a murine macrophage cell line. Finally, we evaluated the protective effect of Ca37 mAb in vivo in both Galleria mellonella and a murine model of systemic infection.

Altogether, this study provides new insights into the therapeutic potential of Ca37 mAb against C. auris, while also highlighting the need for further in vivo investigations to optimise efficacy and safety.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Yeast and RAW 264.7 Cell Line Cultures

Five C. auris isolates belonging to the clade III from bloodstream infections were used in this study: four non-aggregative isolates, CECT (Spanish Culture Type Collection) 13225, CJ-194, CJ-195, and CJ-196, and an aggregative one, CECT 13226. These C. auris isolates were obtained from an outbreak at La Fe University and Polytechnic Hospital (Valencia, Spain) and were provided by Dr. Javier Pemán.

All yeast strains were cryopreserved at −80 °C and cultured on Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA) (VWR, Radnor, PA, USA) at 37 °C for 24 h prior to use. To obtain C. auris cells, the fungi were suspended in Phosphate-Buffered Saline (PBS) (Corning Inc., Corning, NY, USA). The cell density was adjusted using a Bürker counting chamber to inoculate 105 yeast cells/mL in Sabouraud Dextrose Broth (SDB) (VWR) and cells were incubated at 37 °C overnight with shaking at 120 rpm. Finally, the fungal cells were collected by centrifugation (8100× g for 3 min), washed twice in PBS and adjusted to the needed concentration.

RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cell line (ATCC, Manassas, MA, USA) was grown in RPMI 1640 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated Fetal Bovine Serum (VWR), L-glutamine (2 mM) (VWR), penicillin (10,000 U/mL), streptomycin (10 mg/mL) and amphotericin B (25 μg/mL) (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity atmosphere. Cell passages were done when cells reached 80–90% confluence. In addition, cell viability was determined by staining an aliquot with 0.4% Trypan Blue Solution (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) and counting in a Bürker counting chamber. All assays were performed with cultures showing at least 95% viability.

2.2. C. auris Total Protein and CWAP Extraction

Total protein and CWAP were extracted independently from

C. auris CECT 13225, following the methodologies described by Areitio et al. [

13] and Pitarch et al. [

14], respectively. For total protein extracts, yeast cells were resuspended in PBS containing 1% β-mercaptoethanol (Merck) and 1% Pharmalyte (Cytiva, Washington, DC, USA). For CWAP, cells were resuspended in lysis buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4; 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride [PMSF]). In both cases, yeast cells were mixed with 0.5 mm glass beads and disrupted using a MillMix 20 BeadBeater (Tehtnica, Železniki, Slovenia) for 20 min at 30 Hz. The lysates were centrifuged to separate the supernatant and pellet. For total protein extract, the supernatant was collected and stored at −20 °C until use. For CWAP, the pellet was retained and sequentially washed five times with each of the following cold solutions: distilled H

2O, 5% NaCl, 2% NaCl, 1% NaCl, and 1 mM PMSF. The washed pellet was subsequently treated with SDS extraction buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M EDTA, 2% SDS, 10 mM DTT) for 10 min at 100 °C and centrifuged. The resulting supernatant was collected as the CWAP fraction and stored at −20 °C until use.

2.3. Detection and Identification by LC-MS/MS of the Immunoreactive Protein Spots

Protein separation by SDS-PAGE was carried out by loading protein samples onto 10% acrylamide gels, which were run at 70 mA, 100 W, and 200 V for 45 min in a Mini-PROTEAN II system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Page Ruler Plus (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used as the molecular weight marker. For two-dimensional electrophoresis, the method described by Antoran et al. [

12] was applied, using 7 cm Immobiline DryStrip gels pH 3–10 (Cytiva) for isoelectric focusing under the following conditions: rehydration for 12 h, 500 V for 2000 Vhr, 1000 V for 3000 Vhr, 5000 V for 10,000 Vhr, and 5000 V for 40,000 Vhr. Proteins were then separated by SDS-PAGE, and gels were stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue R250 (Merck) for protein visualisation.

For WB, proteins were transferred to Amersham Hybond-P PVDF membranes (Cytiva) for 1 h at 400 mA using a Trans-Blot Semi-Dry Transfer Cell system (Bio-Rad) with Bjerrum Schafer-Nielsen buffer (0.582% [w/v] Tris, 0.293% [w/v] glycine, 20% [v/v] methanol, pH 9.2). Successful transfer was confirmed by staining with Ponceau Red (0.2% [w/v] Ponceau Red and 1% [v/v] acetic acid) (Merck). After blocking, the membranes were incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary Ca37 mAb at a concentration of 60 μg/mL in Tris-Buffered Saline Milk (TBSM; 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% [w/v] Tween 20, and 5% [w/v] skimmed milk powder; all from Merck). After washing the membrane four times for 5 min each with TBS, the secondary antibody, anti-mouse IgG-HRP conjugate (DC02L, Merck), diluted 1:100,000 in TBSM, was added and incubated for 30 min. The membrane was then washed again with TBS and the proteins of interest were visualised using the ECL Prime chemiluminescence kit (NZYTech, Lisbon, Portugal) in a G: BOX Chemi imaging system (Syngene, Cambridge, UK). All incubation steps were performed at room temperature with constant agitation, unless otherwise specified.

The selected protein spots were manually excised from gels stained with Coomassie Brilliant Blue G250 (Merck) and identified by Liquid Chromatography–Mass Spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) at the University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU) proteomics service, SGIker, following the method described by Areitio et al. [

13], with some modifications. Briefly, LC-MS/MS analyses were performed using Exploris 240 mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), coupled to an EASY-nLC 1200 system (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Peptide sequences were searched against the

C. auris subset of the UniProt database “

https://www.uniprot.org/ (accessed on 6 June 2025)” for protein identification. The mass spectrometry proteomics data have been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium via the PRIDE [

15] partner repository with the dataset identifier PXD070229.

2.4. Inhibitory Effect of Ca37 Monoclonal Antibody on Fungal Growth In Vitro

To assess the impact of the Ca37 mAb on

C. auris, we followed the protocol established by Magliani et al. [

16].

C. auris CECT 13225 yeast cells were adjusted to a density of 1.5 × 10

3 cells/mL and incubated with antibody concentrations of 1, 2, 10 and 20 μg/mL and without antibody at 37 °C and 120 rpm for 18 h. To remove antibody aggregates, the mAb was subjected to a thermal-cycling treatment as described by Sadavarte and Ghosh [

17], and then filtered prior to use.

Once the optimal concentration (10 μg/mL) was selected, all isolates described in

Section 2.1 were tested. To verify the specificity of Ca37 mAb inhibition, an IgG1 isotype control antibody (M5384, Merck) was included and incubated with the yeast cells under the same conditions. Following incubation, three independent replicates of each condition, untreated control, IgG1 isotype control, and Ca37 mAb treatment, were plated on SDA. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for 24 h, and the resulting Colony-Forming Units (CFUs) were counted. Growth in the Ca37 mAb and IgG1 isotype groups was normalised to the untreated control to calculate the percentage of growth.

In addition, a growth curve was performed using C. auris CECT 13,255 to characterise the kinetics of the Ca37 mAb. A total of 1.5 × 103 cells/mL were incubated at 37 °C for 40 h. Absorbance was measured at 600 nm using a Synergy TM HT plate reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA) every 10 min after vigorous shaking for one minute. Incubations were carried out in SDB medium under three conditions: fungal cells incubated with PBS (untreated control), 10 µg/mL Ca37 mAb, or 10 µg/mL IgG1 isotype control. In addition, medium-only controls containing PBS, Ca37 mAb, or IgG1 isotype were also included. Absorbance values were converted to C. auris log10 cells/mL.

2.5. In Vitro Phagocytosis Assay

To study the role of the mAb in opsonisation, a phagocytosis assay was conducted in 24-well plates. In each well, a 12 mm diameter coverslip was placed, and on top of it, 105 RAW 264.7 macrophages were seeded in supplemented RPMI 1640. The cells were incubated for 24 h, allowing their number to approximately double. After incubation, the liquid from the wells was removed and co-incubation with C. auris CECT 13225 was initiated using the same medium but without amphotericin B. A Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) of 5 was used and 10 μg/mL Ca37 mAb was added to each well of the treatment group, while PBS was added to the untreated control group. After co-incubation periods of 1, 2, and 4 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and 95% humidity atmosphere, the coverslips were removed, and placed in cold PBS to stop the phagocytosis. Finally, these coverslips were examined under a reverse microscope (Eclipse TE2000-U, Nikon, Tokyo, Japan), and the phagocytosis percentage ([phagocytic macrophages/total macrophages] × 100) and the phagocytic index ([phagocytised yeast/phagocytic macrophages] × 100) were calculated. For each incubation time, three biological replicates were prepared for both the Ca37 mAb and PBS groups, each consisting of three wells. In every well, at least 100 macrophages were counted across five fields of view.

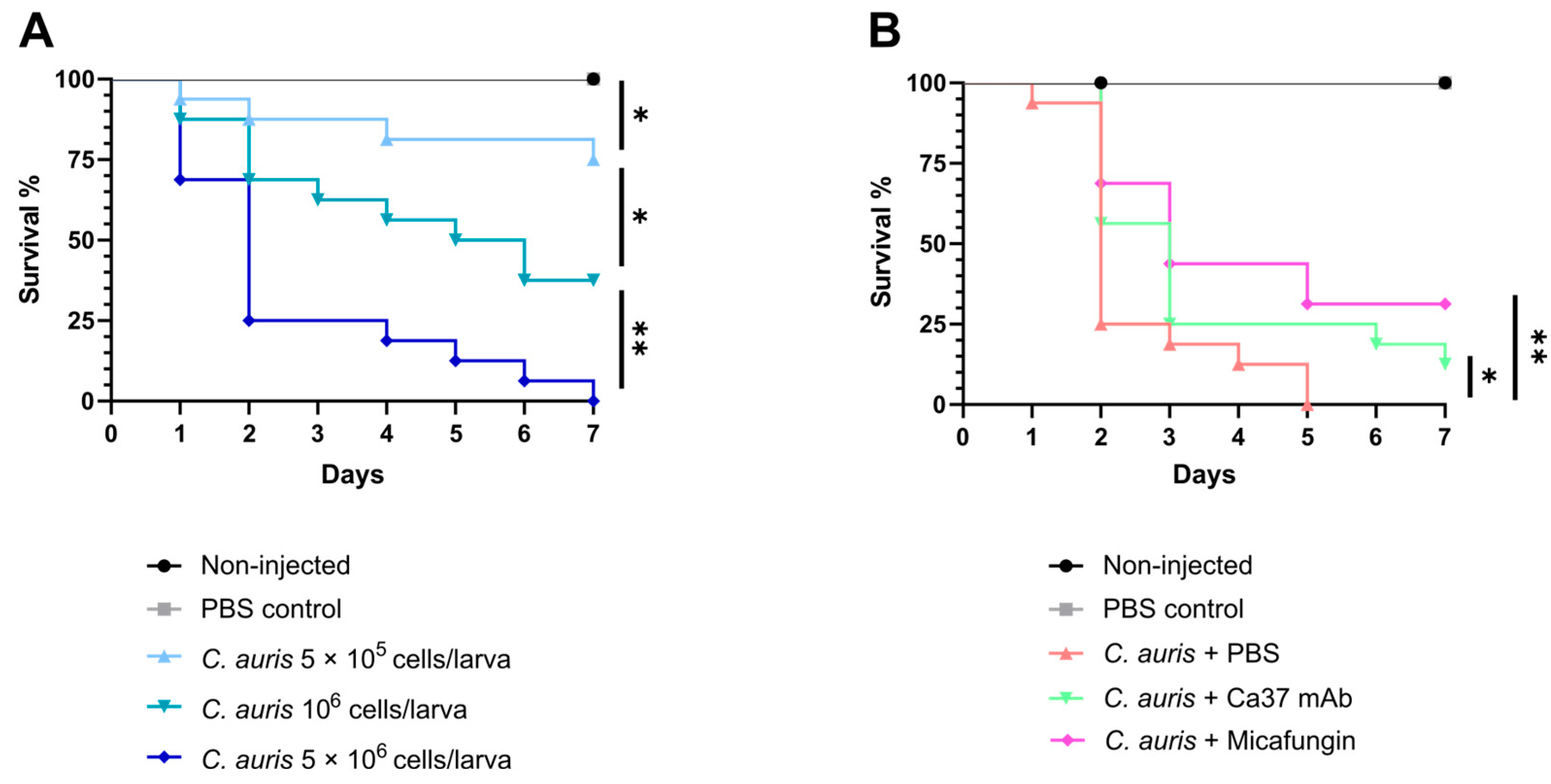

2.6. Galleria mellonella Infection Studies

Galleria mellonella sixth-instar larvae (200–250 mg) were obtained from Reptimercado S. COOP (Murcia, Spain). Larvae were kept without food overnight in the dark before use and cleaned with 70% ethanol on the day of the experiment. For inoculation, syringes with a 26G needle (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) were used. For optimal infection dose assessment, 10 μL of inoculum were injected into the last left pro-leg of each larva. Three infection doses of

C. auris CECT 13225, corresponding to 5 × 10

5, 10

6 and 5 × 10

6 cells per larva, were tested. Before the first use, after changing treatments and every six injections the syringe was cleaned with the following products: 10% bleach, 100% ethanol, sterile filtered distilled water, and sterile filtered PBS [

18]. Sixteen larvae were used per group, and two negative controls were included in all experiments: non-injected (only cleaned with 70% ethanol) and injected with sterile filtered PBS (PBS control). This approach allowed for the monitoring of natural larval death and death resulting from the injection procedure. After inoculation, larvae were incubated at 37 °C, and mortality was observed daily over 7 days by removing dead larvae. Finally, the inoculated yeasts were plated on SDA in triplicate, allowing CFU counts to determine the initial inoculum density.

Once the optimal infection dose of 5 × 106 cell/larva was established, the effect of Ca37 mAb as treatment was evaluated. For this purpose, each larva from all groups received two injections of 10 μL in the last pro-legs. The first injection involved inoculating C. auris in the las left pro-leg, and the additional injection was administered in the last right pro-leg using either PBS, 10 μg/mL Ca37 antibody, or 5 mg/kg micafungin. To achieve the final concentrations in the larvae, the average weight of the group was taken into account. Micafungin dosage was adjusted according to larval weight, while for Ca37 mAb, grams were assumed to equal millilitres, and the stock was prepared accordingly.

Micafungin was chosen as positive control treatment, as it is commonly used against infections caused by

Candida species. The dose used in this study has been used as a treatment against

C. auris yeast in mice [

19] and even against

Candida species in

G. mellonella [

20].

2.7. Murine Infection Studies

Six-week-old Swiss male and female mice, sourced from Janvier Labs (Le Genest-Saint-Isle, France), were housed and used at the SGIker Animal Facility of the UPV/EHU. They were kept in sterile, filter-aerated cages and had continuous access to food and water. The UPV/EHU Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee approved all experimental protocols (M20/2023/121). In total, 48 immunocompetent mice (24 males and 24 females) were used and divided into four groups: PBS—PBS (uninfected untreated), PBS—Ca37 mAb (uninfected treated), C. auris—PBS (infected untreated), and C. auris—Ca37 mAb (infected treated). Each group consisted of six female and six male mice, which were split into two groups (three males and three females), to perform two independent experiments.

Mice were anesthetised with an intraperitoneal injection of 100 mg/kg ketamine and 10 mg/kg xylazine. A total of 5 × 10

7 C. auris CECT 13225 cells, suspended in 0.2 mL of PBS, were intravenously injected into the tail vein of each animal in the two infection groups. The inoculation dose of

C. auris was selected based on a previous study of our research group that demonstrated its ability to consistently establish infection in murine models [

13]. The two uninfected groups received 0.2 mL of PBS as the first injection. Additionally, after the first injection and on days three and six, mice were treated with either PBS or the Ca37 mAb. The dose of 10 μg/mL Ca37 mAb was selected based on preliminary data demonstrating its efficacy both in vitro and in vivo (using

G. mellonella) against

C. albicans [

12] and

C. auris in this study. The dose for mice was calculated based on the assumption that blood volume represents approximately 6% of body weight [

21]. Thus, the Ca37 mAb dose was adjusted to this estimated blood volume of each mouse according to its body weight on the injection day. The

C. auris inoculum was confirmed by plating and counting serial dilutions of the infection dose on SDA plates.

Every day, mice were weighed and a wellbeing evaluation was carried out following the approved symptoms scoring table (

Table S1). All types of symptoms were studied, although two major groups predominated: physical symptoms (hunched abdomen and ruffled fur) and neurophysiological symptoms (particularly leaning to one side and stereotypies). Eleven days post-infection, the mice were euthanised and brain, lungs, kidneys, spleen, and liver were collected. Each organ was divided into two halves; one half was used for fungal load determination via CFUs counting, and the other half was preserved for histological examination.

For the fungal load assessment, the organs were weighed and homogenised in 1 mL of PBS. A 0.1 mL aliquot of the diluted homogenate was plated in duplicate on SDA plates containing 10 μg/mL chloramphenicol and 25 μg/mL gentamicin (Merck). Plates were incubated at 37 °C, and CFUs were counted after 2–3 days. The limit of detection (LOD) was defined as the lowest microbial density (log CFU/g) required to detect one CFU in the plated volume. Data below the LOD, including zero values, were censored at this limit. Fungal load was calculated as CFU per gram of organ tissue. Log10 transformations were applied to CFU data to normalise the distribution before statistical analysis.

Following dissection, organ samples were fixed in neutral buffered formaldehyde and routinely dehydrated in a graded series of ethanol for subsequent histological examination. Paraffin blocks were obtained from kidney samples, as they were the organs with the highest fungal burden. Five µm thick sections were obtained in a Leica RM 2125RT microtome (Leica Biosystems, Nussloch, Germany) and sections were adhered to previously albumin coated microscopical slides. Slides where then dried overnight at 37 °C and then Haematoxylin–Eosin (H&E) stain was carried out for general observation [

22]. For Periodic Acid-Schiff (PAS) staining, sections were dewaxed in xylene and rehydrate in a graded series of ethanol to distilled water. Samples were oxidised with periodic acid (1%) for 10 min and rinse in distilled water. Then, sections were cover with Schiff reagent for 20 min and rinsed in running tap water for 5 min. Nuclei were stained with haematoxylin for counterstain and after differentiation, dehydrated in graded series of ethanol, cleared with xylene and coverslip [

23].

To determine the volume density of the granulomatous inflammations observed in kidney samples, the area of the total renal tissue and the area on the inflammations were outlined by hand and determined with the aid of an image analysis software (ImageJ v1.54, National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MA, USA). Then, the volume density was calculated based on the relation between the area of the inflammations and the total area of the renal tissue ([area of the inflammation/total area of renal tissue] × 100).

2.8. Statistics

Each experiment was conducted independently three times, except for the Galleria mellonella and mouse infection studies. For G. mellonella, experiments were repeated twice with n = 32 larvae per group. For the mouse experiments, a total of 48 mice (24 males and 24 females) were used, split into two independent experiments of 24 mice each. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22 (Professional Statistic, Chicago, IL, USA). Data normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test, and homogeneity of variances was assessed using the Levene’s test. For normally distributed data, analysis was performed using Student’s t-test for two-group comparisons, or U-Mann–Whitney for no-normally distributed ones. Statistical analyses comparing survival curves of G. mellonella were conducted using GraphPad version 8.0.2, employing the Mantel–Cox test. A significance level of p < 0.05 was set for all comparisons.

4. Discussion

In this study, we evaluated the antifungal potential of the Ca37 mAb against

C. auris, an emerging multidrug-resistant pathogen associated with nosocomial outbreaks and high mortality [

4]. The toxicity, limited efficacy, and emerging resistance of current antifungal therapies have intensified the search for alternative approaches, such as monoclonal antibody-based immunotherapy [

25].

The Ca37 mAb generated by our group targeted the Adh of

C. albicans [

12], which is a well-characterised immunogenic protein with multiple roles in fungal pathogens. Several glycolytic enzymes, including Adh, function as moonlighting proteins in

Candida spp., localising in the cell wall and contributing to virulence [

10]. Their surface localisation facilitates interaction with host immune components and provides a target for antibody-mediated recognition. At least seven isoforms of

C. albicans Adh have been identified, with Adh1 being the predominantly expressed variant and responsible for catalysing the conversion of ethanol to acetaldehyde, a reaction with implications for biofilm formation and morphogenesis [

10].

In contrast, knowledge of Adh function in

C. auris is limited. Recent studies suggest a distinct expression profile. Specifically, antifungal stress (e.g., pyrvinium pamoate treatment) induces upregulation of Adh1 and Adh5, consistent with a metabolic shift towards fermentation under mitochondrial dysfunction [

26]. Moreover, Adh2 has been implicated in biofilm formation in antifungal resistant strains, suggesting functional specialisation across isoforms [

27].

Given the relevance of this protein, the high sequence homology within the

Candida and related genera, and its low similarity to human homologues (

Table S2), this protein represents an attractive therapeutic target. Thus, the Ca37 mAb has previously shown inhibitory activity in vitro and protective effects in vivo against

C. albicans infection in

G. mellonella [

12]. However, its effect on

Candida species and other genera, including

C. auris, was unknown.

Our data show that the Ca37 mAb is active in vitro not only against

C. albicans [

12] but also against

C. auris, suggesting that surface-exposed Adh plays a role in fungal viability and is a target for antibody-mediated inhibition. Although our results do not conclusively demonstrate that Ca37 mAb specifically recognizes

C. auris Adh, this protein was present in the mixture of CWAPs corresponding to the two spots detected by the mAb in the immunoproteomics assay.

In addition, the Ca37 mAb significantly inhibited

C. auris growth at the same dose previously identified as optimal for

C. albicans [

12]. However, differences in growth inhibition between

C. albicans and

C. auris strains were observed. While growth inhibition in

C. albicans ranged from 70% to 90% [

12], inhibition among

C. auris isolates was more variable, ranging from 46.5% to 83%. This difference between the species may reflect variations in the amino acid sequences of Adh, although the specific epitope recognised by Ca37 mAb has not yet been identified. The activity showed isolate-dependent variability, consistent with other findings using mAbs targeting other conserved fungal antigens, such as Phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (Pgk1) and trimannose carbohydrate (β-Man3), which also displayed differential effects across

C. auris strains [

28]. In our study, the isolate exhibiting the lowest inhibition (CECT 13226) corresponded to an aggregative phenotype. Although the aggregative phenotype has been linked to the evasion of phagocytosis [

29], its potential to evade humoral immunity, such as antibodies, remains unclear. Further studies are needed to determine whether this phenotype contributes to reduced antibody accessibility or epitope masking.

The Ca37 mAb also enhanced phagocytosis by murine macrophages, suggesting a dual mechanism of action combining direct antifungal activity and immune-mediated mechanisms. This dual mechanism is consistent with previous reports on antifungal mAbs against

C. auris and other fungi [

28,

30,

31].

In vivo, similar to the effect observed with

C. albicans [

12], the Ca37 mAb conferred protection to

G. mellonella larvae infected with

C. auris, as evidenced by a statistically significant increase in survival compared to untreated control. These findings indicate that the Ca37 mAb exerts a protective effect in

G. mellonella against both species.

Finally, the Ca37 mAb was evaluated in an immunocompetent murine model to confirm its efficacy in a mammalian host. Among infected mice, untreated animals showed a greater, although not statistically significant weight loss compared with those treated with the Ca37 mAb. Moreover, regarding animal welfare, whereas no clinical symptoms were observed in uninfected mice, those infected but treated with the Ca37 mAb exhibited fewer clinical signs and delayed onset of both physical and neurophysiological symptoms, compared to the infected untreated group, indicating a potential protective effect of the antibody on overall clinical condition.

No significant differences in fungal CFU counts were detected across the organs analysed between the infected groups, but the reduction in fungal loads in kidneys and brain (the two organs showing the highest levels of fungal burden) of treated animals warrants further investigation, including the use of other different mAb doses. It is important to note, however, that fungal burden was only assessed at the experimental endpoint, and the fungal load at earlier time points, particularly during antibody administration, remains unknown. Furthermore, the pharmacodynamics of the mAb are unknown. Indeed, other studies evaluating anti-

C. auris mAbs in murine models have reported reductions in fungal burden as early as day 3, 4, or 7 post-infection in immunosuppressed mice [

28,

30,

31]. Regarding sex-related differences, in the infected-untreated group, fungal loads in the brain and liver were higher in males than in females. Similarly, males exhibited more pronounced symptoms in general. This could be related to the stronger immunological responses previously reported in females compared with males [

32]. However, few studies have included both sexes in systemic

C. auris infections in mice, and most research has not specifically addressed sex-related differences.

Histological analysis of the kidneys revealed no detectable abnormalities in both uninfected groups (PBS—PBS and PBS—Ca37 mAb), supporting the safety profile of Ca37 mAb. However, the infected Ca37 mAb-treated group displayed a more extensive immune infiltration and a larger infiltrated area in the kidneys than infected untreated mice, potentially indicating enhanced immune recognition of

C. auris facilitated by the mAb. Notably, while this enhanced immune response did not result in a significant reduction in fungal burden, it did correlate with improved clinical condition. These findings suggest that Ca37 mAb may contribute to host defence by enhancing opsonisation and/or immune recruitment rather than exerting a direct fungicidal effect in vivo, although the underlying processes remain to be elucidated. This effect could be particularly relevant in the context of

C. auris, a pathogen known for its ability to evade immune recognition [

33]. In the case of other described anti-

C. auris mAbs, these showed reduction in fungal burden accompanied by decreased immune cell infiltration [

30] or reduced serum levels of inflammatory markers [

28], accompanied by a reduction in fungal burden. However, models are completely different, as they used immunosuppressed mice and studied the effect at shorter period of infection.

Despite the results presented, this study has also some limitations such as the lack of assessment of the synergistic effect with conventional antifungal drugs, as Ca37 demonstrated in vitro with fluconazole and micafungin against

C. albicans [

12]. Similarly, other monoclonal antibodies have shown activity against biofilms in vitro [

28,

30] suggesting that evaluating Ca37 mAb against

C. auris biofilms could also be of considerable interest. Moreover, including isolates from different

C. auris clades would be valuable. Future studies addressing these aspects will help to better define the therapeutic potential of Ca37 mAb.

Therefore, the findings of this study suggest that Ca37 mAb targets a cell wall-associated antigen involved in host–pathogen interactions and highlight its potential as a candidate for immunotherapy against C. auris. The observed in vitro inhibition of C. auris, enhanced phagocytosis by murine macrophages, and protective effect in G. mellonella further support its potential. Nevertheless, optimising dosing regimens, treatment timing, and exploring potential synergistic effects with existing antifungals will be critical to maximise efficacy in mammalian models. Although improvements in health status and a greater immune response against C. auris were observed in the treated murine model, additional studies are needed to refine this approach and validate its translational relevance.