Evolution of Caprock Sealing Capacity Under CO2–Mechanical Coupling in Geological Carbon Storage

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Samples and Methods

2.1. Samples

2.2. Experiment

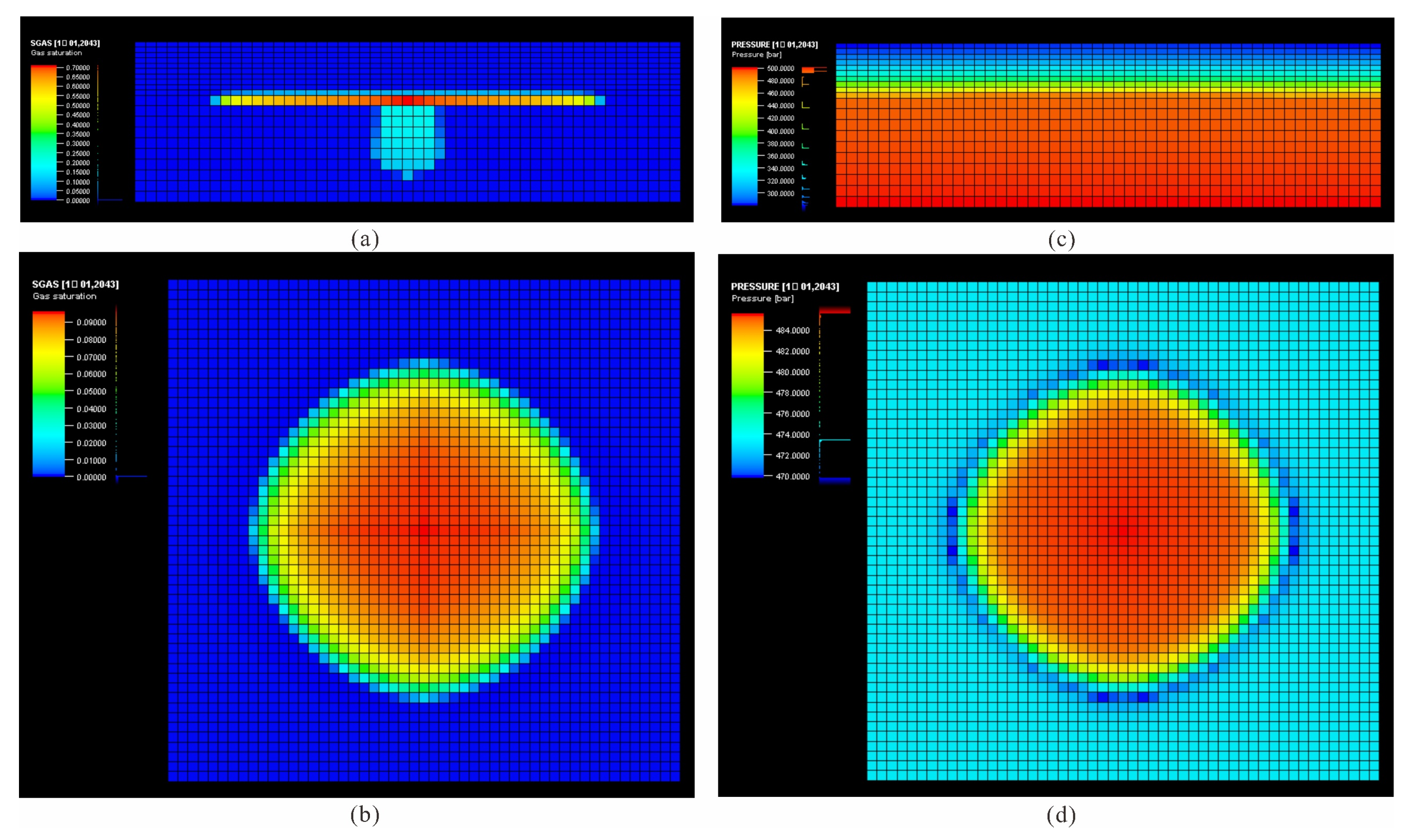

2.3. Numerical Simulation

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Stress Sensitivity Characteristics of Caprock Permeability

3.2. Evolution of Caprock Permeability Under Stress

3.3. Influence of Physical Properties on Caprock Sealing Capacity

3.4. Influence of Mechanical Properties on Caprock Sealing Capacity

4. Conclusions

- (1)

- Mudstone caprocks show strong stress-sensitive permeability at low pore pressures. Once effective stress exceeds about 20 MPa, the permeability stress sensitivity drops markedly. The degree of permeability change is controlled by the caprock’s inherent porosity and pore pressure: higher porosity or lower pore pressure increases stress sensitivity and alters pore-throat connectivity more significantly.

- (2)

- For mudstone caprocks, vertical total stress increases with porosity, permeability, and Young’s modulus, with permeability being the most influential factor. In contrast, vertical effective stress decreases as these parameters increase, but is most affected by porosity, then permeability, and lastly Young’s modulus.

- (3)

- Lower permeability and porosity generally enhance the sealing performance of the caprock. Simultaneously, during CO2 injection, a higher Young’s modulus contributes to greater mechanical stability of the caprock.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gholami, R.; Raza, A.; Iglauer, S. Leakage risk assessment of a CO2 storage site: A review. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2021, 223, 103849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kearns, J.; Teletzke, G.; Palmer, J.; Thomann, H.; Kheshgi, H.; Chen, Y.H.; Paltsev, S.; Herzog, H. Developing a consistent database for regional geologic CO2 storage capacity worldwide. Energy Procedia 2017, 114, 4697–4709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Xu, M.; Wei, S.; Shen, S.; Zhang, X. Carbon reduction potential of China’s coal-fired power plants based on a CCUS source-sink matching model. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2021, 168, 105320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ringrose, P. CO2 Storage Project Design, How to Store CO2 Underground: Insights from Early-Mover CCS Projects; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; pp. 85–126. [Google Scholar]

- Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (UK). Carbon Capture Usage and Storage: A Government Response on Potential Business Models for Carbon Capture, Usage, and Storage; Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (UK): London, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, J.; Wei, N.; Wu, L.; Zhang, N.; Xu, M. Progress in leakage study of geological CO2 storage. Rock Soil Mech. 2017, 38, 181–188. [Google Scholar]

- Green, C.; Ennis-King, J.; Pruess, K. Effect of vertical heterogeneity on long-term migration of CO2 in Saline Formations. Energy Procedia 2009, 1, 1823–1830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espinoza, D.N.; Santamarina, J.C. CO2 breakthrough-Caprock sealing efficiency and integrity for carbon geological storage. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 66, 218–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheibi, S.; Holt, R.M.; Vilarrasa, V. Effect of faults on stress path evolution during reservoir pressurization. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 63, 412–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Khdheeawi, E.A.; Vialle, S.; Barifcani, A.; Sarmadivaleh, M.; Iglauer, S. Impact of reservoir wettability and heterogeneity on CO2-plume migration and trapping capacity. Int. J. Greenh. Gas Control 2017, 58, 142–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquo, B.D.; de Montleau, P.; Daniel, J.M.; Codreanu, D.B. Qualification of a CO2 storage site using an integrated reservoir study. Energy Procedia 2014, 51, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renard, F.; Mair, K.; Gundersen, O. Surface roughness evolution on experimentally simulated faults. J. Struct. Geol. 2012, 45, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.; Jha, N.K.; Pal, N.; Keshavarz, A.; Hoteit, H.; Sarmadivaleh, M. Recent advances in carbon dioxide geological storage, experimental procedures, influencing parameters, and future outlook. Earth-Sci. Rev. 2022, 225, 103895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.Z.; Dai, Q.Q.; Zeng, L.B.; Li, R.Q.; Zhang, R.J.; Qu, L.; Zhu, Y.W.; Liao, H.Y.; Wu, H. Effects of natural fractures in cap rock on CO2 geological storage: Sanduo Formation and Dainan Formation of the early Eocene epoch in the Gaoyou Sag of the Subei Basin. Pet. Sci. 2025, 8, 002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.; Ahmadinia, M.; Shariatipour, S.M.; Lawton, D.; Osadetz, K.; Saeedfar, A. Impact of reservoir permeability, permeability anisotropy and designed injection iate on CO2 gas behavior in the shallow saline aquifer at the CaMI Field Research Station, Brooks, Alberta. Nat. Resour. Res. 2020, 29, 2735–2752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Wang, G.; Zhao, X.; Han, Z.; Lu, K.; Lai, J.; Wang, S.; Li, D.; Li, Y.; Wu, K. Fractal model for permeability estimation in low-permeable porous media with variable pore sizes and unevenly adsorbed water lay. Mar. Pet. Geol. 2021, 130, 105135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadatnia, N.; Sharghi, Y.; Moghadasi, J.; Ezati, M. Coupled hydro--mechanical simulation in the carbonate reservoir of a giant oil field in southwest Iran. J. Pet. Explor. Prod. Technol. 2024, 14, 59–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Jia, S.P.; Xu, M.; Zhang, P.J.; Li, J.; Zhang, L.G. Coupled seepage-stress analysis of fault instability induced by CO2 injection. J. Northeast Pet. Univ. 2023, 47, 69–78. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, W.; Lu, X.; Fan, M.; Zhang, D.; Cao, J. Advances in the research of shale caprocks: Type, micropore characteristics and sealing mechanisms. Bull. Mineral. Petrol. Geochem. 2019, 38, 885–896+869. [Google Scholar]

- Singh, H.; Islam, A. Enhanced safety of geologic CO2 storage with nanoparticles. Int. J. Heat Mass Transf. 2018, 121, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loucks, R.L.; Reed, R.M.; Ruppel, S.; Jarvie, D.M. Morphology, genesis, and distribution of nanometer-scale pores in siliceous mudstones of the Mississippian Barnett shale. J. Sediment. Res. 2009, 79, 848–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Q.; Luo, Q.; Zhang, C.; Lu, C.; Zhang, Y.; Lu, S.; Zhao, Y. Pore structure characteristics of tight-oil sandstone reservoir based on a new parameter measured by NMR experiment: A case study of seventh Member in Yanchang Formation, Ordos Basin. Acta Pet. Sin. 2016, 37, 887–897. [Google Scholar]

- Agrawal, P.; Mascini, A.; Bultreys, T.; Aslannejad, H.; Wolthers, M.; Cnudde, V.; Butler, I.B.; Raoof, A. The impact of pore-throat shape evolution during dissolution on carbonate rock permeability: Pore network modeling and experiments. Adv. Water Resour. 2021, 155, 103991. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, L.T.; Loucks, R.G.; Zhang, T.; Ruppel, S.C.; Shao, D. Pore and pore network evolution of Upper Cretaceous Boquillas (Eagle Ford–equivalent) mudrocks: Results from gold tube pyrolysis experiments. AAPG Bull. 2016, 100, 1693–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Zhao, Q.; Yang, H.; Ge, H.K. Combining acoustic emission and unsupervised machine learning to investigate microscopic fracturing in tight reservoir rock. Eng. Geol. 2025, 107939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Mineral | Maximum (%) | Minimum (%) | Average (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chlorite | 50.7 | 38.0 | 48.3 |

| Illite | 3.2 | 1.4 | 2.6 |

| Calcite | 15.6 | 8.2 | 12.6 |

| Quartz | 25.0 | 11.2 | 22.6 |

| Other | 15.1 | 7.7 | 13.9 |

| Models | Porosity (%) | Permeability (mD) | Young’s Modulus (GPa) |

|---|---|---|---|

| P-2 K-2 E-2 | 7 | I = 0.0001 J = 0.0001 K = 0.00001 | 5 |

| P-1 | 4 | I = 0.0001 J = 0.0001 K = 0.00001 | 5 |

| P-3 | 10 | ||

| K-1 | 7 | I = 0.0001 J = 0.0001 K = 0.0001 | 5 |

| K-3 | I = 0.001 J = 0.001 K = 0.001 | ||

| E-1 | 7 | I = 0.0001 J = 0.0001 K = 0.00001 | 10 |

| E-3 | 15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wu, H.; Dai, Q.; Wang, R.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, Y. Evolution of Caprock Sealing Capacity Under CO2–Mechanical Coupling in Geological Carbon Storage. Processes 2025, 13, 3863. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123863

Wu H, Dai Q, Wang R, Zhou Y, Zhang Y. Evolution of Caprock Sealing Capacity Under CO2–Mechanical Coupling in Geological Carbon Storage. Processes. 2025; 13(12):3863. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123863

Chicago/Turabian StyleWu, Hao, Quanqi Dai, Rui Wang, Yinbang Zhou, and Yunzhao Zhang. 2025. "Evolution of Caprock Sealing Capacity Under CO2–Mechanical Coupling in Geological Carbon Storage" Processes 13, no. 12: 3863. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123863

APA StyleWu, H., Dai, Q., Wang, R., Zhou, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2025). Evolution of Caprock Sealing Capacity Under CO2–Mechanical Coupling in Geological Carbon Storage. Processes, 13(12), 3863. https://doi.org/10.3390/pr13123863