Proteasome and Ribosome Ubiquitination in Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells in Response to Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (OxLDL)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture and Treatment

2.2. Sample Preparation and Protein Digestion

2.3. Enrichment of Ubiquitinated Peptides

2.4. LC-MS/MS Analysis

2.5. Mass Spectrometry Data Processing

2.6. Statistical Analysis

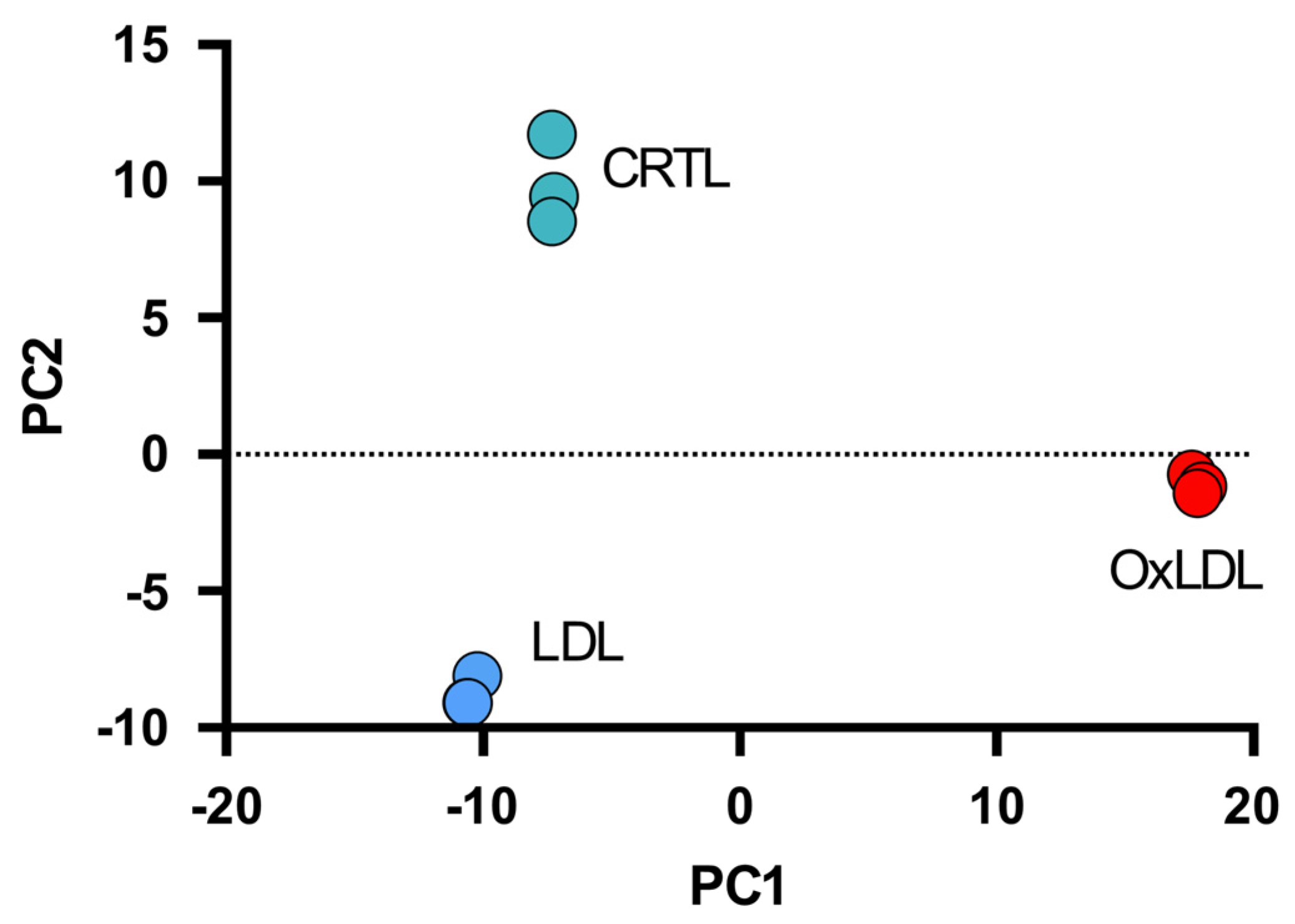

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AMD | Age-related macular degeneration |

| FC | Fold change |

| FDR | False discovery rate |

| LC-MS/MS | Liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry |

| LDL | Low-density lipoprotein |

| OxLDL | Oxidized low-density lipoprotein |

| PCA | Principal component analysis |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| TEAB | Triethylammonium bicarbonate |

| UPS | Ubiquitin–proteasome system |

References

- Wong, E.; Cuervo, A.M. Integration of clearance mechanisms: The proteasome and autophagy. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2010, 2, a006734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noormohammadi, A.; Calculli, G.; Gutierrez-Garcia, R.; Khodakarami, A.; Koyuncu, S.; Vilchez, D. Mechanisms of protein homeostasis (proteostasis) maintain stem cell identity in mammalian pluripotent stem cells. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2018, 75, 275–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.K.; Puri, S.; Sharma, A.; Pastor, A.; Chaudhuri, T.K. Molecular Chaperones: Structure-Function Relationship and their Role in Protein Folding. In Regulation of Heat Shock Protein Responses; Asea, A.A.A., Kaur, P., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 181–218. [Google Scholar]

- Varshavsky, A. The ubiquitin system, autophagy, and regulated protein degradation. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2017, 86, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bursch, W. The autophagosomal-lysosomal compartment in programmed cell death. Cell Death Differ. 2001, 8, 569–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, N.; Li, J.; Chen, X.; Zhao, M.; Huang, L. Association Between Autophagy and Ubiquitin-proteasome System in Age-related Macular Degeneration. Nat. Cell Sci. 2023, 1, 2–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandi, D.; Tahiliani, P.; Kumar, A.; Chandu, D. The ubiquitin-proteasome system. J. Biosci. 2006, 31, 137–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, A.L.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, D.; Collins, G.A. Mechanisms that activate 26S proteasomes and enhance protein degradation. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, S.; Zhou, J.; Li, D. Functions and Diseases of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 727870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakkaraju, A.; Umapathy, A.; Tan, L.X.; Daniele, L.; Philp, N.J.; Boesze-Battaglia, K.; Williams, D.S. The cell biology of the retinal pigment epithelium. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 78, 100846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bird, A. Role of retinal pigment epithelium in age-related macular disease: A systematic review. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 2021, 105, 1469–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Datta, S.; Cano, M.; Ebrahimi, K.; Wang, L.; Handa, J.T. The impact of oxidative stress and inflammation on RPE degeneration in non-neovascular AMD. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2017, 60, 201–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Sivaprasad, S. Drusen and pachydrusen: The definition, pathogenesis, and clinical significance. Eye 2021, 35, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campello, L.; Singh, N.; Advani, J.; Mondal, A.K.; Corso-Diaz, X.; Swaroop, A. Aging of the Retina: Molecular and Metabolic Turbulences and Potential Interventions. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2021, 7, 633–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, J.; Fernandes, A.F.; Sparrow, J.R.; Pereira, P.; Taylor, A.; Shang, F. The proteasome: A target of oxidative damage in cultured human retina pigment epithelial cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 3622–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giorgianni, F.; Beranova-Giorgianni, S. Oxidized low-density lipoprotein causes ribosome reduction and inhibition of protein synthesis in retinal pigment epithelial cells. Biochem. Biophys. Rep. 2022, 32, 101345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finkbeiner, S. The Autophagy Lysosomal Pathway and Neurodegeneration. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2020, 12, a033993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hazim, R.A.; Volland, S.; Williams, D.S. A Rapid protocol for the differentiation of human ARPE-19 cells. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2018, 59, 3980. [Google Scholar]

- Fronk, A.H.; Vargis, E. Methods for culturing retinal pigment epithelial cells: A review of current protocols and future recommendations. J. Tissue Eng. 2016, 7, 2041731416650838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samuel, W.; Jaworski, C.; Postnikova, O.A.; Kutty, R.K.; Duncan, T.; Tan, L.X.; Poliakov, E.; Lakkaraju, A.; Redmond, T.M. Appropriately differentiated ARPE-19 cells regain phenotype and gene expression profiles similar to those of native RPE cells. Mol. Vis. 2017, 23, 60. [Google Scholar]

- Koirala, D.; Beranova-Giorgianni, S.; Giorgianni, F. Early Transcriptomic Response to OxLDL in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 8818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thanou, E.; Koopmans, F.; Pita-Illobre, D.; Klaassen, R.V.; Ozer, B.; Charalampopoulos, I.; Smit, A.B.; Li, K.W. Suspension TRAPping Filter (sTRAP) Sample Preparation for Quantitative Proteomics in the Low microg Input Range Using a Plasmid DNA Micro-Spin Column: Analysis of the Hippocampus from the 5xFAD Alzheimer’s Disease Mouse Model. Cells 2023, 12, 1242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordureau, A.; Münch, C.; Harper, J.W. Quantifying ubiquitin signaling. Mol. Cell 2015, 58, 660–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang da, W.; Sherman, B.T.; Lempicki, R.A. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat. Protoc. 2009, 4, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Acosta-Alvear, D.; Harnoss, J.M.; Walter, P.; Ashkenazi, A. Homeostasis control in health and disease by the unfolded protein response. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2025, 26, 193–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, J.; Zou, T.; Lin, Z. The Roles of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System in the Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Pathway. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa-Mattioli, M.; Walter, P. The integrated stress response: From mechanism to disease. Science 2020, 368, eaat5314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bond, S.; Lopez-Lloreda, C.; Gannon, P.J.; Akay-Espinoza, C.; Jordan-Sciutto, K.L. The Integrated Stress Response and Phosphorylated Eukaryotic Initiation Factor 2alpha in Neurodegeneration. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 79, 123–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, H.; Fan, Y.; Wu, L.; Fang, Y.; Wei, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Cao, Y. Integrated stress response mediates HSP70 to inhibit testosterone synthesis in aging testicular Leydig cells. Reprod. Biol. 2024, 24, 100954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choo, J.; Schlosser, D.; Manzini, V.; Magerhans, A.; Dobbelstein, M. The integrated stress response induces R-loops and hinders replication fork progression. Cell Death Dis. 2020, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Wang, X.; Li, X.; Qiu, K.; Jiao, F.; Liu, Y.; Kong, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wu, Y. Proteasome Inhibition Activates Autophagy-Lysosome Pathway Associated with TFEB Dephosphorylation and Nuclear Translocation. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2019, 7, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, C.; Liu, Y.; Fu, Z. Implications of endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in aging and cardiovascular diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2024, 15, 1413853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husnjak, K.; Elsasser, S.; Zhang, N.; Chen, X.; Randles, L.; Shi, Y.; Hofmann, K.; Walters, K.J.; Finley, D.; Dikic, I. Proteasome subunit Rpn13 is a novel ubiquitin receptor. Nature 2008, 453, 481–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, T.-X.; Zhao, M.; Qiu, X.-B. Substrate receptors of proteasomes. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1765–1777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakata, E.; Bohn, S.; Mihalache, O.; Kiss, P.; Beck, F.; Nagy, I.; Nickell, S.; Tanaka, K.; Saeki, Y.; Forster, F.; et al. Localization of the proteasomal ubiquitin receptors Rpn10 and Rpn13 by electron cryomicroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2012, 109, 1479–1484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, T.; Song, Y.; Ray, A.; Wan, X.; Yao, Y.; Samur, M.K.; Shen, C.; Penailillo, J.; Sewastianik, T.; Tai, Y.T.; et al. Ubiquitin receptor PSMD4/Rpn10 is a novel therapeutic target in multiple myeloma. Blood 2023, 141, 2599–2614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sokolova, V.; Li, F.; Polovin, G.; Park, S. Proteasome Activation is Mediated via a Functional Switch of the Rpt6 C-terminal Tail Following Chaperone-dependent Assembly. Sci. Rep. 2015, 5, 14909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, H.; Choi, A.J.; Kang, G.Y.; Park, H.S.; Kim, H.C.; Lim, H.J.; Chung, H. Increased 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 in the aqueous humor of patients with age-related macular degeneration. BMB Rep. 2014, 47, 292–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakamura, Y.; Nakano, K.; Umehara, T.; Kimura, M.; Hayashizaki, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Horikoshi, M.; Padmanabhan, B.; Yokoyama, S. Structure of the oncoprotein gankyrin in complex with S6 ATPase of the 26S proteasome. Structure 2007, 15, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franklin, T.B.; Krueger-Naug, A.M.; Clarke, D.B.; Arrigo, A.P.; Currie, R.W. The role of heat shock proteins Hsp70 and Hsp27 in cellular protection of the central nervous system. Int. J. Hyperth. 2005, 21, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sooraj, K.; Shukla, S.; Kaur, R.; Titiyal, J.S.; Kaur, J. The protective role of HSP27 in ocular diseases. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2022, 49, 5107–5115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersen, K.M.; Madsen, L.; Prag, S.; Johnsen, A.H.; Semple, C.A.; Hendil, K.B.; Hartmann-Petersen, R. Thioredoxin Txnl1/TRP32 is a redox-active cofactor of the 26 S proteasome. J. Biol. Chem. 2009, 284, 15246–15254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kriegenburg, F.; Poulsen, E.; Koch, A.; Krüger, E.; Hartmann-Petersen, R. Redox Control of the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System: From Molecular Mechanisms to Functional Significance. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 15, 2265–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wooten, M.W.; Hu, X.; Babu, J.R.; Seibenhener, M.L.; Geetha, T.; Paine, M.G.; Wooten, M.C. Signaling, polyubiquitination, trafficking, and inclusions: Sequestosome 1/p62’s role in neurodegenerative disease. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2006, 2006, 62079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasiak, J.; Pawlowska, E.; Szczepanska, J.; Kaarniranta, K. Interplay between Autophagy and the Ubiquitin-Proteasome System and Its Role in the Pathogenesis of Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, U.R.; Madden, B.J.; Charlesworth, M.C.; Fautsch, M.P. Proteome analysis of human aqueous humor. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 4921–4931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.W.; Kang, J.W.; Ahn, J.; Lee, E.K.; Cho, K.C.; Han, B.N.; Hong, N.Y.; Park, J.; Kim, K.P. Proteomic analysis of the aqueous humor in age-related macular degeneration (AMD) patients. J. Proteome Res. 2012, 11, 4034–4043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dougherty, S.E.; Maduka, A.O.; Inada, T.; Silva, G.M. Expanding Role of Ubiquitin in Translational Control. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monem, P.C.; Arribere, J.A. A ubiquitin language communicates ribosomal distress. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2024, 154, 131–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brandman, O.; Hegde, R.S. Ribosome-associated protein quality control. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2016, 23, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matsuo, Y.; Ikeuchi, K.; Saeki, Y.; Iwasaki, S.; Schmidt, C.; Udagawa, T.; Sato, F.; Tsuchiya, H.; Becker, T.; Tanaka, K.; et al. Ubiquitination of stalled ribosome triggers ribosome-associated quality control. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundaramoorthy, E.; Leonard, M.; Mak, R.; Liao, J.; Fulzele, A.; Bennett, E.J. ZNF598 and RACK1 Regulate Mammalian Ribosome-Associated Quality Control Function by Mediating Regulatory 40S Ribosomal Ubiquitylation. Mol. Cell 2017, 65, 751–760.e754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Back, S.; Gorman, A.W.; Vogel, C.; Silva, G.M. Site-Specific K63 Ubiquitinomics Provides Insights into Translation Regulation under Stress. J. Proteome Res. 2019, 18, 309–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, R.; Gendron, J.M.; Rising, L.; Mak, R.; Webb, K.; Kaiser, S.E.; Zuzow, N.; Riviere, P.; Yang, B.; Fenech, E.; et al. The Unfolded Protein Response Triggers Site-Specific Regulatory Ubiquitylation of 40S Ribosomal Proteins. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 35–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papendorf, J.J.; Kruger, E.; Ebstein, F. Proteostasis Perturbations and Their Roles in Causing Sterile Inflammation and Autoinflammatory Diseases. Cells 2022, 11, 1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hohn, A.; Tramutola, A.; Cascella, R. Proteostasis Failure in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Focus on Oxidative Stress. Oxidative Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 2020, 5497046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurtishi, A.; Rosen, B.; Patil, K.S.; Alves, G.W.; Moller, S.G. Cellular Proteostasis in Neurodegeneration. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 3676–3689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, K.; Matsuda, N. Proteostasis and neurodegeneration: The roles of proteasomal degradation and autophagy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2014, 1843, 197–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, J.; Gaur, M.; Swaroop, A.; Taylor, A. Proteostasis in aging-associated ocular disease. Mol. Asp. Med. 2022, 88, 101157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Accession Number | Protein Name | Adjusted p-Value | FC OxLDL Versus CRTL | # Ubiquitinated Peptides | # Ubiquitinated Residues | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q16186 | Proteasomal ubiquitin receptor (ADRM1/Rpn13) | 2.32 × 10−5 | 1.53 | 2 | 2 | 0.979 | 0.096 |

| P04792 | Heat shock protein beta-1 (HspB1) | 1.07 × 10−8 | 4.23 | 4 | 5 | 0.795 | −0.609 |

| P55036 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 4 (PSMD4/Rpn10) | 3.93 × 10−6 | 1.58 | 4 | 6 | 0.948 | 0.292 |

| P62191 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 4 (PSMC1/Rpt2) | 3.79 × 10−6 | 2.83 | 7 | 7 | 0.989 | −0.011 |

| P35998 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 7 (PSMC2/Rpt1) | 4.01 × 10−7 | 4.25 | 8 | 9 | 0.992 | −0.051 |

| P62333 | 26S proteasome regulatory subunit 10B (PSMC6/Rpt4) | 7.49 × 10−9 | 10.31 | 9 | 12 | 0.982 | −0.173 |

| O75832 | 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 10 (PSMD10/Gankyrin) | 6.36 × 10−8 | 2.82 | 1 | 1 | 0.997 | 0.008 |

| O43396 | Thioredoxin-like protein 1 (TXNL1) | 5.82 × 10−12 | inf | 4 | 4 | 0.991 | −0.129 |

| Accession Number | Protein Name | Adjusted p-Value | FC OxLDL Versus CRTL | # Ubiquitinated Peptides | # Ubiquitinated Residues | PC1 | PC2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| P63244 | Small ribosomal subunit protein (RACK1) | 2.04 × 10−2 | 1.50 | 2 | 2 | 0.246 | −0.718 |

| P62906 | Large ribosomal subunit protein (uL1) | 3.75 × 10−8 | 3.33 | 2 | 2 | 0.817 | −0.568 |

| P36578 | Large ribosomal subunit protein (uL4) | 6.77 × 10−3 | −4.32 | 2 | 2 | −0.815 | −0.508 |

| P62424 | Large ribosomal subunit protein (eL8) | 7.53 × 10−4 | −1.63 | 3 | 3 | −0.747 | −0.657 |

| P32969 | Large ribosomal subunit protein (uL6) | 4.12 × 10−3 | 1.88 | 1 | 1 | −0.341 | −0.922 |

| P62241 | Small ribosomal subunit protein (eS8) | 5.41 × 10−4 | −1.92 | 1 | 1 | −0.701 | −0.708 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Giorgianni, F.; Beranova-Giorgianni, S. Proteasome and Ribosome Ubiquitination in Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells in Response to Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (OxLDL). Biomedicines 2025, 13, 3004. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123004

Giorgianni F, Beranova-Giorgianni S. Proteasome and Ribosome Ubiquitination in Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells in Response to Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (OxLDL). Biomedicines. 2025; 13(12):3004. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123004

Chicago/Turabian StyleGiorgianni, Francesco, and Sarka Beranova-Giorgianni. 2025. "Proteasome and Ribosome Ubiquitination in Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells in Response to Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (OxLDL)" Biomedicines 13, no. 12: 3004. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123004

APA StyleGiorgianni, F., & Beranova-Giorgianni, S. (2025). Proteasome and Ribosome Ubiquitination in Retinal Pigment Epithelial (RPE) Cells in Response to Oxidized Low-Density Lipoprotein (OxLDL). Biomedicines, 13(12), 3004. https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines13123004