Abstract

Background: The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) authorized over 690 machine learning (ML)-enabled medical devices between 1995 and 2023. In 2024, new guidance enabled the inclusion of Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCPs), raising expectations for transparency, equity, and safety under the Good Machine Learning Practice (GMLP) framework. Objective: The objective was to assess regulatory pathways, predicate lineage, demographic transparency, performance reporting, and PCCP uptake among ML-enabled devices approved by the FDA in 2024. Methods: We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of all FDA-authorized ML-enabled devices in 2024. Data extracted from FDA summaries included regulatory pathway, predicate genealogy, performance metrics, demographic disclosures, PCCPs, and cybersecurity statements. Descriptive and nonparametric statistics were used. Results: The FDA authorized 168 ML-enabled Class II devices in 2024. Most (94.6%) were cleared via 510(k); 5.4% were cleared via De Novo. Radiology dominated (74.4%), followed by cardiovascular (6.5%) and neurology (6.0%). Non-US sponsors accounted for 57.7% of clearances. Among 159 510(k) devices, 97.5% cited an identifiable predicate; the median predicate age was 2.2 years (IQR 1.2–4.1), and 64.5% ML-enabled. Predicate reuse remained uncommon (9.9%). Median review time was 162 days (151 days for 510(k) vs. 372 days De Novo; p < 0.001). A total of 49 devices (29.2%) reported both sensitivity and specificity; 15.5% provided demographic data. PCCPs appeared in 16.7% of summaries, and cybersecurity considerations appeared in 54.2%. Conclusions: While 2024 marked a record year for ML-enabled device approvals and internationalization, uptake of PCCPs and transparent performance and demographic reporting remained limited. Policy efforts to standardize disclosures and strengthen post market oversight are critical for realizing the promises of GMLP.

1. Introduction

Artificial intelligence (AI) innovations have transitioned from experimental proofs of concept to regulated clinical products with remarkable speed. In the United States, one of the leading hubs for digital health innovation, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) had authorized 692 AI/Machine Learning (ML)-enabled devices by 2023, representing a 20-fold increase compared to the mean annual approval rate between 1995 and 2015 [1]. This growth has sharpened long-standing questions about how to ensure the safety, effectiveness, and equity of technologies whose performance can evolve continuously in response to new data.

Regulatory bodies have begun to facilitate the marketing of these innovations while addressing the emerging challenges through a life-cycle, practice-oriented framework. In 2021, the FDA, Health Canada, and the United Kingdom Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency released ten “Good Machine Learning Practice” (GMLP) guiding principles, spanning rigorous software engineering, representative datasets, human-AI team performance, and post-deployment monitoring [2]. Building on GMLP principle 10, the FDA adapted guiding principles in early 2024 on Predetermined Change Control Plans (PCCPs)—a mechanism that enables sponsors to seek prospective authorization for specified algorithm updates, thereby aligning regulatory review with the rapid cadence of model iteration [3].

Yet technological innovation has outpaced regulatory frameworks, ensuring that AI devices are being developed and evaluated in ways that advance equity and transparency. A recent scoping review of 692 FDA-approved AI/ML devices between 1995 and 2023 found that only 3.6% reported race or ethnicity of validation cohorts, less than 1% provided socioeconomic information, and fewer than 2% linked to peer-reviewed performance studies. These gaps may exacerbate health disparities, particularly among vulnerable and underrepresented populations, and compromise the reliability of approved devices [4]. The consequences of inadequate demographic representation and algorithmic bias are not merely theoretical. For example, previous research demonstrated that a widely deployed population-health algorithm systematically underestimated illness severity in Black patients by relying on healthcare expenditures as a proxy for clinical need, thereby embedding structural inequities in healthcare access into clinical decision-making [5].

Regulatory documentation itself may further cloud the picture. One systematic review showed that nearly one-fifth of AI devices marketed in the United States described capabilities that were not reflected in their cleared indications for use, which raised concerns about “function creep” beyond the evidence base reviewed by the FDA [6]. Meanwhile, early uptake of PCCPs appears limited, and it remains unclear whether the new guidance has improved AI fairness disclosures, including performance metrics, demographic representativeness, or cybersecurity practices [7].

Recent analyses offer additional context for interpreting these gaps. Studies evaluating PCCPs highlight their potential to streamline oversight of evolving software while also identifying limitations in current regulatory readiness and stakeholder familiarity with these tools [8,9]. Complementary analyses in pediatric AI governance underscore ongoing risks related to insufficient demographic diversity and unclear accountability structures [10]. Broader assessments of U.S. AI/ML regulation likewise point to persistent gaps in data governance, monitoring rigor, and oversight of continuously learning systems, further underscoring why mechanisms such as GMLP and PCCPs have become central to regulatory modernization efforts [11].

The present study provides a comprehensive assessment of all AI/ML-enabled medical devices cleared or approved by the FDA during calendar year 2024. Focusing on regulatory pathways, predicate genealogies, approval timelines, reporting of performance and demographic data, cybersecurity provisions, and adoption of PCCPs, we aim to determine whether the most recent cohort of clearances signals substantive progress toward the goals articulated in GMLP or perpetuates previously documented shortcomings. Insights from this analysis are intended to inform ongoing policy deliberations and to guide clinicians, developers, and regulators seeking to balance rapid innovation with the imperatives of safety, effectiveness, and health equity.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Data Source

We conducted a cross-sectional analysis of all ML-enabled medical devices approved by the FDA in 2024. Device data were extracted from the FDA’s official database of AI/ML-enabled medical devices (https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/software-medical-device-samd/artificial-intelligence-and-machine-learning-aiml-enabled-medical-devices, accessed on 17 May 2025). As all materials are in the public domain, institutional review board oversight was not required.

2.2. Data Extraction

For each device, we systematically extracted device-level identifiers (submission number, manufacturer, sponsor country, specialty panel, intended use, and regulatory pathway), regulatory characteristics (device class, presence of PCCP, designation as software-as-a-medical-device [SaMD], cybersecurity statements, and pediatric indication), machine-learning characteristics (algorithm architecture where documented), bias and fairness variables (disclosure of demographic baseline variables including sex, age, and race/ethnicity), performance metrics (sensitivity, specificity, area under the receiver-operating-curve, positive/negative predictive value, and other task-appropriate metrics with confidence intervals where provided), and 510(k) genealogy data (submission numbers of primary and secondary predicates, reference devices, year of clearance, and ML-enablement status). Data were extracted manually from FDA 510(k) and De Novo decision summaries. Each variable was cross-checked for internal consistency across the device summary, labeling, and decision memo to ensure accuracy.

2.3. Regulatory Pathway and Genealogy Analysis

We categorized devices according to their regulatory pathway (510(k) or De Novo) and further classified 510(k) devices by submission type (Traditional, Special, or Abbreviated). For devices approved through the 510(k) pathway, we identified primary predicates and any additional predicates or reference devices cited in the substantial equivalence determination. We documented the approval date of each predicate to establish temporal relationships and calculated the time elapsed between predicate approval and subsequent device clearance.

To identify ML-enabled medical devices, we cross-referenced each predicate against the FDA’s official database of AI/ML-enabled medical devices. Each predicate was labeled as either ML-enabled or non-ML-enabled based on its inclusion in the FDA list. For each 510(k)-cleared device, we constructed a regulatory genealogy by identifying its primary predicate and determining whether that predicate was ML-enabled. We documented instances of predicate reuse and calculated the frequency with which specific predicates were cited. The regulatory pathway of each predicate was also recorded to characterize the lineage structure of contemporary ML-enabled medical devices.

2.4. Approval Timeline Evaluation

We calculated the time from FDA submission to clearance for each device by comparing submission and approval dates documented in FDA summaries. These approval timelines were analyzed across different regulatory pathways, medical specialties, and manufacturer origins.

2.5. Regulatory Preparedness Evaluation

We assessed the presence of PCCPs in device submissions as an indicator of regulatory preparedness for algorithm modifications. Additionally, we documented mentions of cybersecurity considerations, pediatric indications, and SaMD classifications.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics are reported as counts and percentages, medians with interquartile ranges (IQR), or means ± SD as appropriate. Continuous variables were compared with the Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Approval-time distributions were right-skewed and therefore summarized with medians (IQR) and compared across pathways and specialty panels with nonparametric tests. Statistical analyses were performed using RStudio (Version 2023.06.1 + 524). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Given the primarily descriptive aims of the study, p-values are interpreted as heuristic measures of association.

3. Results

3.1. Characteristics of FDA-Approved AI/ML Medical Devices in 2024

During the calendar year 2024, the FDA approved a total of 168 ML-enabled medical devices. Of these, the vast majority (159 devices, 94.6%) were cleared through the 510(k) regulatory pathway, while 9 devices (5.4%) received approval via the De Novo pathway. All ML-enabled devices authorized in 2024 were classified as Class II under the FDA’s risk-based regulatory framework. Among 510(k) approvals, most were submitted through the Traditional 510(k) process, accounting for 137 devices or 86.2%. An additional 20 devices (12.6%) were cleared via Special 510(k) process and 2 devices (1.3%) via Abbreviated 510(k) (Table 1) process.

Table 1.

Summary Characteristics of Machine Learning-Enabled Medical Devices Approved by the FDA in 2024 (n = 168).

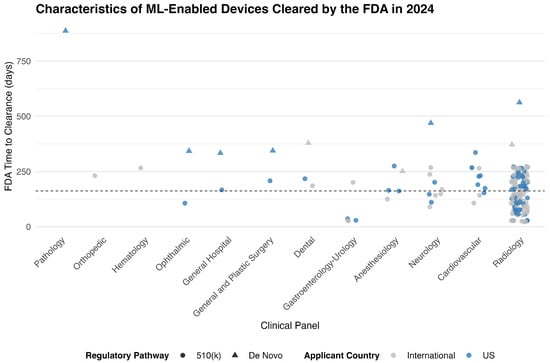

3.2. Distribution of Devices by Clinical Specialty

Radiology accounted for the vast majority of ML-enabled device approvals in 2024, with 125 devices (74.4%) cleared under this panel. The next most common specialties were Cardiovascular (11 devices, 6.5%) and Neurology (10 devices, 6.0%). Other panels contributed smaller numbers, including Anesthesiology and Gastroenterology–Urology (5 devices each), Dental (3 devices), and several others with only one or two approvals (Figure 1, Table 1).

Figure 1.

FDA Time to Clearance for ML-Enabled Devices in 2024, by Clinical Panel and Regulatory Pathway. Each point represents a medical device authorized by the FDA in 2024. Symbols indicate regulatory pathway (circle for 510(k), triangle for De Novo), and color indicates applicant origin (blue for U.S.-based sponsors, gray for international). The vertical axis shows the FDA review duration in days. The dashed horizontal line indicates the overall median time to clearance (162 days).

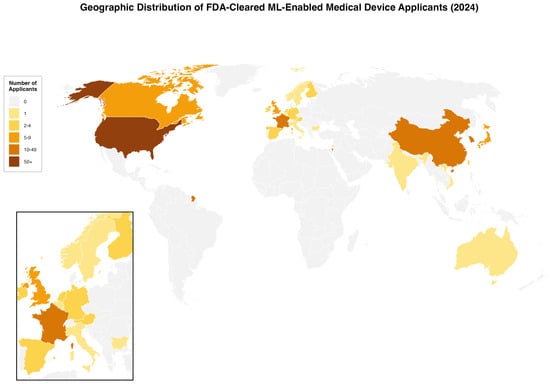

3.3. Geographic Distribution of FDA-Approved AI/ML Devices

In 2024, non-US applicants accounted for the majority of FDA-cleared ML-enabled medical devices, with 97 approvals (57.7%). Overall, 168 devices were cleared from 24 countries. The top contributing countries were the United States (71 devices, 42.3%), followed by France (16, 9.5%), China (14, 8.3%), South Korea (11, 6.5%), Israel (11, 6.5%), and Japan (7, 4.2%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Geographic Distribution of FDA-Cleared ML-Enabled Medical Device Applicants in 2024. World map showing the number of applicants by country for FDA-cleared machine learning-enabled medical devices in 2024 (N = 168). Countries are color-coded by the number of applicants. Inset shows European detail. The US had 71 applicants (42·3%), France 16 (9·5%), and China 14 (8·3%).

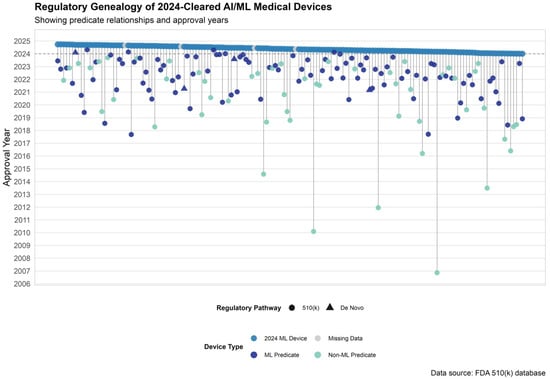

3.4. Regulatory Genealogy and Innovation Lineage of 510(K) AI/ML Devices

3.4.1. Temporal Patterns of Predicate Selection

Among the 159 AI/ML-enabled devices approved via the 510(k) pathway in 2024, 155 devices (97.5%) had identifiable primary predicates. The remaining 4 devices (2.5%) lacked predicate information in publicly available FDA summaries. Of the 155 devices with valid predicate data, predicates were most commonly approved in 2022 (43 predicates, 27.7%) and 2023 (41 predicates, 26.5%), followed by 2021 (22 predicates, 14.2%) and 2020 (15 predicates, 9.7%). A small number of predicates dated back more than a decade, with the earliest approved in 2006 (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Predicate Genealogy of AI/ML Devices Cleared by the FDA in 2024. Predicate device lineage for 2024-cleared AI/ML-enabled devices. Each vertical line connects a 2024-cleared device (top row) to its primary predicate, color-coded by predicate type: dark blue for ML-enabled predicates, teal for non-ML predicates, and gray for missing data. Shapes indicate regulatory pathway.

Across all predicate devices cited by AI/ML devices cleared in 2024, the median time since predicate market entry was 2.2 years (IQR: 1.2–4.1). ML-based predicates were significantly newer to market than non-ML predicates (median 1.9 years [IQR: 1.0–3.0] vs. 2.8 years [IQR: 1.7–5.5]; p < 0.001).

3.4.2. Predicate Reuse and ML vs. Non-ML Lineage

A total of 141 unique primary predicates were used by 510(k)-cleared AI/ML devices in 2024. Of these, 14 predicates (9.9%) were reused by more than one 2024 device. Among the 141 unique predicates, 91 (64.5%) were identified as AI/ML-based. Eleven of the 91 AI/ML-based predicates (12.1%) were reused, compared to 3 of 50 non-ML predicates (6.0%).

Among reused predicates, the median time from original clearance to reuse was 1.4 years (IQR: 1.2–2.3). ML-based predicates had a median reuse age of 1.5 years (IQR: 1.3–2.2), compared to 1.2 years (IQR: 0.9–4.0) for non–ML predicates.

The majority of predicates were originally cleared through the 510(k) pathway (137 predicates, 97.2%), while 4 predicates (2.8%) were approved via the De Novo pathway (Figure 3).

3.4.3. AI Predicate Lineage Structure

Among the 155 FDA-cleared AI/ML devices approved via the 510(k) pathway in 2024, 126 devices (81.3%) relied solely on a single primary predicate for substantial equivalence. The remaining devices demonstrated more complex regulatory ancestry, with twenty-nine devices (18.7%) citing additional predicates. In addition, 50 devices (32.3%) included reference devices to support technological comparisons.

3.4.4. FDA Approval Timelines

The median time from FDA submission to clearance for all ML-enabled devices in 2024 was 162 days (IQR: 106 to 230 days), with a range of 23 to 887 days. Devices cleared through the 510(k) pathway had a significantly shorter median approval time of 151 days, compared to 372 days for those approved via the De Novo pathway (p < 0.001). Across medical specialties, approval times varied substantially. Radiology devices—the most common panel—had a median approval time of 146 days, significantly shorter than devices reviewed under other panels (p = 0.002). No statistically significant difference in approval times was observed between devices originating from the United States (median 172 days) and those from international manufacturers (median 151 days) (p = 0.42) (Supplementary Table S1).

3.5. Performance Metrics and Demographic Representativeness (AI Fairness)

3.5.1. Performance Metrics

Among the 168 ML-enabled medical devices cleared by the FDA in 2024, both sensitivity and specificity were reported jointly in 49 devices (29.2%). Sensitivity alone was reported in 54 devices (32.1%), while specificity alone was reported in 49 devices (29.2%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Regulatory and Clinical Characteristics of FDA-Authorized Machine Learning-Enabled Medical Devices in 2024.

3.5.2. Fairness and Representativeness

Demographic information related to sex or race and ethnicity was reported in 77 of the 168 device summaries (45.8%). Sex data were reported in 73 devices (43.5%). Race or ethnicity—categorized as White, Black, Asian, or Other—was reported in 26 devices (15.5%) (Table 2).

3.6. Predetermined Change Control Plans and Regulatory Preparedness

Among the 168 AI/ML-enabled medical devices cleared or approved in 2024, 28 devices (16.7%) included PCCPs, while 140 devices (83.3%) did not. Cybersecurity considerations were mentioned in 91 devices (54.2%). Pediatric indications were identified in 30 devices (17.9%). A total of 46 devices (27.4%) were categorized as SaMD (Table 1).

PCCPs were most commonly observed among devices reviewed under the Radiology panel (15 devices), followed by Neurology (4 devices), Anesthesiology (3 devices), and smaller counts in other specialties. By region, US-based manufacturers accounted for 17 of 28 PCCPs (60.7%), while 11 devices (39.3%) originated from international developers, including submissions from Israel (3 devices, 10.7%) and France (2 devices, 7.1%). Overall, PCCPs were submitted by manufacturers from nine different countries.

4. Discussion

In 2024, the FDA authorized a record 168 AI/ML-enabled devices, surpassing prior years and signaling sustained momentum in digital health innovation [12]. Radiology remained dominant, but nearly 58% of approvals originated from international sponsors. While the majority of devices were cleared via the 510(k) pathway, most predicates were recent and increasingly AI/ML-enabled, reflecting the fast-paced evolution of this sector. Despite regulatory advances, the actual uptake of PCCPs and performance transparency remains modest. Only 16.7% of devices reported PCCPs, and less than one-fifth disclosed complete sensitivity/specificity metrics. Demographic data reporting improved from historical norms but still fell short: just 15.5% of summaries reported race or ethnicity, limiting the ability to evaluate representativeness and equity. To our knowledge, this is the first study to systematically evaluate PCCP reporting in FDA-authorized AI/ML-enabled medical devices following the implementation of the FDA’s 2024 PCCP guidance.

These findings have several regulatory-science implications. The modest uptake of PCCPs, despite their importance for lifecycle oversight, suggests ongoing uncertainty among manufacturers about how to operationalize adaptive model management under emerging FDA expectations [9,13]. Similarly, limited reporting of performance metrics and demographic characteristics aligns with prior evidence of substantial transparency gaps in FDA-cleared AI technologies [1] and reinforces concerns about inadequate information for assessing clinical generalizability at the time of authorization [14]. Persistent underreporting of race and ethnicity is especially consequential given growing evidence of significant subgroup performance differences across diverse populations [15]. Taken together, these patterns show that key disclosure practices remain incomplete and have not yet kept pace with evolving regulatory expectations.

Compared with the 1995–2023 baseline of 692 devices, the 2024 cohort showed a steeper year-to-year growth rate, shorter review times, and slightly improved transparency. Demographic reporting rose from 3.6% to 16%, yet fewer than one in five summaries provided race or ethnicity data [1]. While this reflects progress, the absence of structured, subgroup-level reporting continues to limit assessments of fairness and external validity in healthcare AI. Persistent gaps in demographic transparency reflect entrenched representation bias—a well-documented barrier to the generalizability of model performance and clinical outcomes across diverse populations [16,17].

Recent evaluations further highlight the scale of this challenge. A systematic review of 48 AI studies found that more than half exhibited a high risk of bias, largely attributable to absent sociodemographic data, imbalanced datasets, and inadequate algorithmic design [18]. Similarly, a review of 555 neuroimaging AI models revealed that 83% had a high risk of bias, with most studies relying almost exclusively on data from high-income regions [19]. Likewise, a systematic review demonstrated that among 11 cardiovascular AI studies reviewed, 9 (82%) showed significant performance differences across racial and ethnic groups, with some studies showing sensitivity differences as high as 52.6% versus 39.6% between Black and White patients [15].

Our findings reinforce prior evidence that representation bias is not an isolated anomaly but a pervasive, systemic flaw. Combined with algorithmic biases introduced during model development and validation, representation bias critically undermines the generalizability and clinical applicability of AI/ML models. Without systematic strategies for bias recognition and mitigation, the ethical and equitable deployment of AI in healthcare will remain at risk.

Consistent with the historical dominance of the substantial-equivalence pathway [20,21], the overwhelming majority of AI/ML-enabled medical devices cleared in 2024 proceeded through the 510(k) pathway. Despite the innovative nature of AI/ML devices and their moderate-risk classification, De Novo review remained limited to five percent of all approvals. The markedly shorter review times and lower evidentiary thresholds associated with 510(k) submissions likely further incentivized manufacturers to pursue the 510(k) route.

Analysis of primary predicate genealogy revealed that more than one-third of devices cleared via 510(k) relied on conventional, non-ML-based systems, similar to trends observed between 2019 and 2021 [22]. Predicate reuse was uncommon—only 14 of 141 unique predicates (9.9%) were cited by more than one 2024 clearance—indicating a rapidly turning lineage in which most predicates serve a single subsequent device. These findings highlight a persistent reliance on the 510(k) framework, even for software that is ostensibly innovative, and reveal a mixed predicate ancestry that may complicate future efforts to monitor safety signals across related AI products.

Beyond the substantial-equivalence framework, other regulatory domains such as cybersecurity and change management also merit attention. Although cybersecurity considerations were mentioned in just over half of device summaries and PCCPs appeared in only 17% of cases, both findings likely reflect the recency of regulatory expectations in these areas. As PCCP frameworks and cybersecurity guidance continue to evolve, improvements in the completeness and consistency of these disclosures may be anticipated in future device cohorts. As the global development pipeline for AI/ML-enabled medical devices continues to expand [23], proactive and adaptive regulatory strategies will be essential to ensure that future approvals adequately address emerging clinical and technological complexity.

The study has some limitations. First, the analysis relied exclusively on publicly available FDA summaries, which often lack standardized reporting, particularly regarding performance metrics, demographic representativeness, and cybersecurity measures. This limitation may have led to an underestimation of the true extent of disclosures, such as PCCPs or risk mitigation strategies. Second, the classification of devices as AI/ML-based depended on available documentation; in cases of ambiguous or incomplete descriptions, there is a possibility of misclassification. Third, the study could not assess postmarket modifications, iterative algorithm updates, or real-world performance drift, which are increasingly relevant in evaluating the lifecycle safety and effectiveness of AI/ML-enabled medical devices. Fourth, while the analysis captures regulatory genealogy through primary predicate selection, it does not trace extended secondary or tertiary generation predicate linkages, potentially underestimating the complexity of predicate ancestry. Finally, given the recent introduction of PCCP and cybersecurity frameworks, findings from the 2024 cohort may not fully reflect the long-term uptake or impact of these regulatory initiatives, and ongoing surveillance will be necessary to assess trends over time.

5. Conclusions

In 2024, the FDA approved a record number of ML-enabled medical devices, with the vast majority cleared via the 510(k) pathway. Approvals were predominantly concentrated in radiology and increasingly originated from international developers. While most devices relied on recently approved predicates, predicate reuse remained uncommon. Interestingly, reused predicates were more frequently AI/ML-based than non-AI/ML-based. Approval timelines were shortest for specialties with the highest volume of submissions. Reporting of performance metrics and demographic representation was inconsistent. Additionally, cybersecurity considerations and Predetermined Change Control Plans were documented in only a minority of devices. A substantial proportion of submissions were classified as software as a medical device, underscoring the increasing digitalization of regulated clinical technologies.

Future work should track how disclosure practices evolve over time and whether emerging FDA initiatives, such as PCCPs and strengthened cybersecurity expectations, improve the completeness and quality of public information. Longitudinal studies linking regulatory data with clinical and postmarket performance will be essential to determine whether current pathways adequately support the safe, effective, and equitable deployment of medical AI.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/biomedicines13123005/s1, Table S1: FDA Approval Timelines by Regulatory Pathway, Country of Origin, and Clinical Panel.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, B.A.; methodology, B.A., L.F.G.-G., L.A.d.S.B. and F.F.; data curation, B.A., L.F.G.-G. and L.A.d.S.B.; formal analysis, B.A. and L.F.G.-G.; visualization, B.A.; writing—original draft preparation, B.A., L.F.G.-G., L.A.d.S.B. and F.F.; writing—review and editing, A.L., U.G., F.F. and all authors; supervision, F.F.; project administration, F.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable. The study analyzed publicly available FDA regulatory documents.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Muralidharan, V.; Adewale, B.A.; Huang, C.J.; Nta, M.T.; Ademiju, P.O.; Pathmarajah, P.; Hang, M.K.; Adesanya, O.; Abdullateef, R.O.; Babatunde, A.O.; et al. A Scoping Review of Reporting Gaps in FDA-Approved AI Medical Devices. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- US Food and Drug Administration. Good Machine Learning Practice for Medical Device Development: Guiding Principles. FDA, 2025. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/153486/download (accessed on 17 July 2025).

- US Food and Drug Administration. Predetermined Change Control Plans for Machine Learning-Enabled Medical Devices: Guiding Principles. FDA, 2024. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/media/173206/download (accessed on 14 June 2025).

- McNamara, S.L.; Yi, P.H.; Lotter, W. The Clinician-AI Interface: Intended Use and Explainability in FDA-Cleared AI Devices for Medical Image Interpretation. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obermeyer, Z.; Powers, B.; Vogeli, C.; Mullainathan, S. Dissecting Racial Bias in an Algorithm Used to Manage the Health of Populations. Science 2019, 366, 447–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clark, P.; Kim, J.; Aphinyanaphongs, Y. Marketing and US Food and Drug Administration Clearance of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning Enabled Software in and as Medical Devices: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e2321792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillis, J.M.; Visser, J.J.; Cliff, E.R.S.; van der Geest–Aspers, K.; Bizzo, B.C.; Dreyer, K.J.; Adams-Prassl, J.; Andriole, K.P. The Lucent yet Opaque Challenge of Regulating Artificial Intelligence in Radiology. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carvalho, E.; Mascarenhas, M.; Pinheiro, F.; Correia, R.; Balseiro, S.; Barbosa, G.; Guerra, A.; Oliveira, D.; Moura, R.; dos Santos, A.M.; et al. Predetermined Change Control Plans: Guiding Principles for Advancing Safe, Effective, and High-Quality AI–ML Technologies. JMIR AI 2025, 4, e76854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- DuPreez, J.A.; McDermott, O. The Use of Predetermined Change Control Plans to Enable the Release of New Versions of Software as a Medical Device. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2025, 22, 261–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richter, F.; Holmes, E.; Richter, F.; Guttmann, K.; Duong, S.Q.; Gangadharan, S.; Schadt, E.E.; Salmasian, H.; Gelb, B.D.; Glicksberg, B.S. Toward Governance of Artificial Intelligence in Pediatric Healthcare. npj Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahimzadeh, V. US Regulation of Medical Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML) Research and Development. In Handbook of Research on AI in Medicine; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2025. [Google Scholar]

- Joshi, G.; Jain, A.; Araveeti, S.R.; Adhikari, S.; Garg, H.; Bhandari, M. FDA-Approved Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML)-Enabled Medical Devices: An Updated Landscape. Electronics 2024, 13, 498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warraich, H.J.; Tazbaz, T.; Califf, R.M. FDA Perspective on the Regulation of Artificial Intelligence in Health Care and Biomedicine. JAMA 2025, 333, 241–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Windecker, D.; Baj, G.; Shiri, I.; Kazaj, P.M.; Kaesmacher, J.; Gräni, C.; Siontis, G.C. Generalizability of FDA-Approved AI-Enabled Medical Devices for Clinical Use. JAMA Netw. Open 2025, 8, e258052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cau, R.; Pisu, F.; Suri, J.S.; Saba, L. Addressing Hidden Risks: Systematic Review of Artificial Intelligence Biases across Racial and Ethnic Groups in Cardiovascular Diseases. Eur. J. Radiol. 2025, 183, 111867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hasanzadeh, F.; Josephson, C.B.; Waters, G.; Adedinsewo, D.; Azizi, Z.; White, J.A. Bias Recognition and Mitigation Strategies in Artificial Intelligence Healthcare Applications. NPJ Digit. Med. 2025, 8, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Celi, L.A.; Cellini, J.; Charpignon, M.-L.; Dee, E.C.; Dernoncourt, F.; Eber, R.; Mitchell, W.G.; Moukheiber, L.; Schirmer, J.; Situ, J.; et al. Sources of Bias in Artificial Intelligence That Perpetuate Healthcare Disparities—A Global Review. PLoS Digit. Health 2022, 1, e0000022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Aelgani, V.; Vohra, R.; Gupta, S.K.; Bhagawati, M.; Paul, S.; Saba, L.; Suri, N.; Khanna, N.N.; Laird, J.R.; et al. Artificial Intelligence Bias in Medical System Designs: A Systematic Review. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2024, 83, 18005–18057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Liu, X.; Yang, Q.; Wang, Y.-J.; Miao, K.; Gong, Z.; Yu, Y.; Leonov, A.; Liu, C.; Feng, Z.; et al. Evaluation of Risk of Bias in Neuroimaging-Based Artificial Intelligence Models for Psychiatric Diagnosis: A Systematic Review. JAMA Netw. Open 2023, 6, e231671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darrow, J.J.; Avorn, J.; Kesselheim, A.S. FDA Regulation and Approval of Medical Devices: 1976–2020. JAMA 2021, 326, 420–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aboy, M.; Crespo, C.; Stern, A. Beyond the 510(k): The Regulation of Novel Moderate-Risk Medical Devices, Intellectual Property Considerations, and Innovation Incentives in the FDA’s De Novo Pathway. npj Digit. Med. 2024, 7, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muehlematter, U.J.; Bluethgen, C.; Vokinger, K.N. FDA-Cleared Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning-Based Medical Devices and Their 510(k) Predicate Networks. Lancet Digit. Health 2023, 5, e618–e626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Development Pipeline and Geographic Representation of Trials for Artificial Intelligence/Machine Learning–Enabled Medical Devices (2010 to 2023)|NEJM AI. Available online: https://ai.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/AIpc2300038 (accessed on 9 June 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).