1. Introduction

As a branch of artificial intelligence, the recurrent neural network (RNN) model has been widely studied in the fields of science and engineering [

1]. It is a kind of recurrent neural network that takes sequence data as input, recursion in the evolutionary direction of sequence, and links all cyclic nodes together [

2]. Thanks to the rapid development of neural networks, the RNN has also been widely and deeply applied in many fields, including computer vision [

3], neuroscience [

4], speech recognition [

5] and other hot issues [

6,

7,

8]. In order to solve a variety of different computational problems and nonlinear optimization problems, researchers around the world have proposed a variety of RNN variants and improved algorithms [

9,

10,

11]. In general, classical recurrent neural networks can be divided into continuous-time RNNs and discrete-time RNNs. Using the numerical differential formula, the continuous-time RNN model can be discretized into a discrete-time RNN model. However, even if the original continuous-time RNN model is convergent, the numerical differential rules may not be able to generate a convergent and stable discrete-time RNN model, which also means that the classical RNNs have limitations in dealing with time-varying problems.

In order to better apply RNNs to time-varying problems, Zhang et al. [

12] encode the discrete-time RNN model as a serial processing program and execute it on a digital computer and formally propose a special type of recurrent neural network, called zeroing neural network (ZNN). As a new type of RNN specially used to solve time-varying problems, ZNN can perfectly track time-varying solutions by using the time derivative of time-varying parameters [

13]. With the further study of the ZNN model, more and more ZNN variant models have appeared one after another. Li et al. [

14] proposed a predefined time-convergent ZNN model to achieve fast convergence in solving time-varying equality-constrained quadratic program (ECQP) problems. Jin et al. [

15] studied another predefined fixed-time convergent ZNN model by using the power piecewise activation function. Li et al. [

16] proposed a new second-order error processing design formula and further proposed a double integral enhanced zero neural network (DIEZNN) model to solve the time-varying quadratic matrix equation problem affected by linear noise. Guo et al. [

17] proposed a new harmonic noise rejection ZNN (HNR-ZNN) model, which effectively determines the optimal solution of time-varying ECQP under harmonic noise interference by introducing the dynamic characteristics of harmonic signals. In terms of specific applications, ZNNs have successfully dealt with time-varying problems in areas including robotics, chaotic systems, and image processing [

18,

19,

20], and ZNNs are promising in all areas with time-varying problems.

The energy use of buildings currently occupies a very high proportion in the global electricity market, consuming about 30–40% of primary energy [

21]. A key challenge in this domain is the demand response (DR) problem, whose effective resolution enables simultaneous optimization of energy costs and preservation of user comfort [

22]. Under the time-of-use electricity price mechanism, the building energy consumption demand can be converted into a flexible electricity load by installing energy storage equipment in the building, and the electricity capacity can be increased and stored during the low electricity price period to reduce the electricity consumption during the peak electricity price period [

23]. Model predictive control (MPC) has been proven to be a strategy to achieve efficient control of building energy systems [

24], which can provide significant energy savings while maintaining a reasonable indoor environment, but there are also some inherent problems. Firstly, in the process of demand response, there are many continuous time-varying functions, and the MPC method needs to discretize them, which will inevitably introduce errors. Secondly, MPC requires a more accurate dynamic model, but many parameters of the system are difficult to obtain directly in the actual operation of the project. Finally, the computational complexity of the MPC method is high, the corresponding demand for computing resources is large, and the convergence speed is slow.

Beyond traditional optimization methods, recent advances in deep reinforcement learning (DRL) have shown promising results in complex energy management tasks. Representative studies include bi-level adaptive storage expansion strategies for microgrids [

25] and distributed DRL approaches for active distribution networks with renewable integration [

26]. These DRL methods excel in handling high-dimensional state spaces and long-term strategic decisions through data-driven learning. However, they face challenges in real-time demand response applications, including extensive training requirements, a lack of interpretability, and potential instability during online adaptation. This research gap motivates the exploration of approaches that combine model-based rigor with adaptability to time-varying conditions. The zeroing neural network (ZNN) presents such an alternative—offering deterministic convergence guarantees while efficiently handling time-varying parameters. Unlike DRL’s black-box policies, ZNN explicitly incorporates system dynamics, providing transparent and analytically grounded control decisions.

Despite the advancements in MPC and DRL, a significant research gap remains in efficiently solving the time-varying demand response problem with guarantees of real-time performance and robustness. Specifically, MPC struggles with model accuracy and computational burden, while DRL faces challenges in training stability and interpretability for such dynamic systems. To bridge this gap, this paper hypothesizes that the Zeroing Neural Network (ZNN), by leveraging its inherent capability to handle time-varying parameters directly and its model-agnostic nature, can provide a superior control solution. Therefore, this paper proposes a ZNN-based framework to address the challenge of time-varying demand response within building electro-thermal integrated systems. Compared with the traditional RNN and MPC methods, ZNN provides a more adaptive and real-time control solution for the time-varying demand response problem of building electric–thermal systems by virtue of its time-varying derivative construction mechanism, low model dependence, and high computational efficiency. Firstly, the thermodynamic model of the electric–thermal coupling system is constructed, and the ZNN controller is designed accordingly. Then, the demand response mechanism and performance evaluation index of the system are clarified. Finally, the simulation results of the model are analyzed to clarify the error of the ZNN control method, which provides guidance for the time-varying demand response prediction and control method selection of the electric–thermal coupling system.

3. Simulation Results and Discussion

Based on the system model and control rate constructed above, this section will analyze the simulation results from six aspects: electricity price response, power tracking, error analysis, temperature dynamics, heat balance, disturbance estimation, and robustness testing to fully present the dynamic characteristics of the system under the ZNN control rate.

3.1. Electricity Price Response

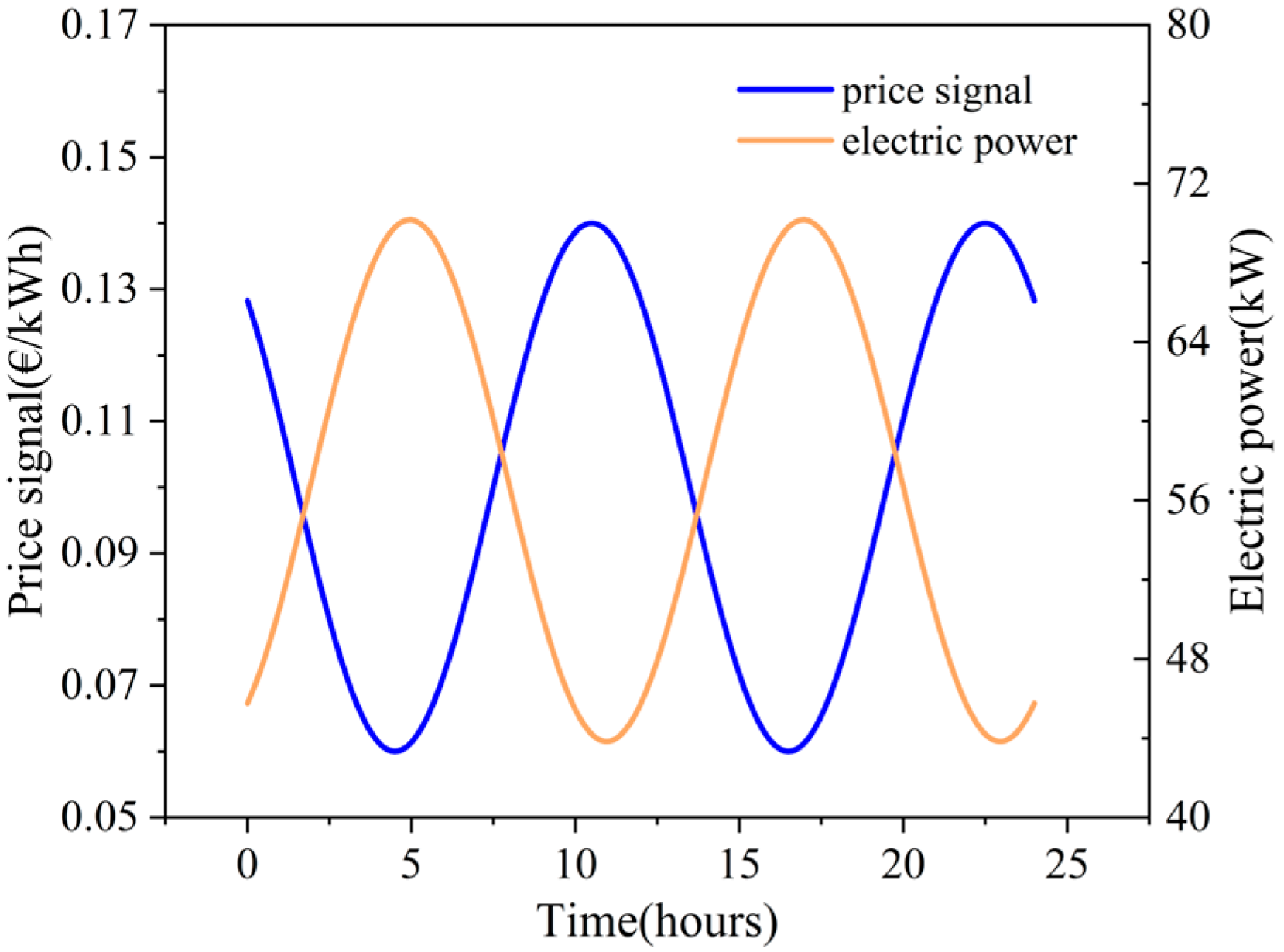

It is necessary to analyze the response characteristics of the electricity price, that is, pay attention to the dynamic relationship between the electricity price signal and power consumption. In the design of the electricity price signal, the system simulates the time-of-use electricity price and fluctuates within 24 h.

Figure 1 shows the day-to-day variation of the electricity price fluctuation in the target power. The target power needs to respond to the electricity price signal, that is, to minimize the electricity cost under the premise of meeting the heat demand. When the electricity price is low and the heat demand is low, the heat pump can run more and store the heat. When the electricity price is high and the heat demand is high, the stored heat can be used to meet the demand. As shown in the diagram, the cycle of the target power is consistent with the electricity price cycle, and due to the fact that the user needs time to adjust after the electricity price changes in the actual situation, there is a phenomenon of response lag, and the phase shift in the diagram also accurately reflects this phenomenon.

3.2. Power Tracking

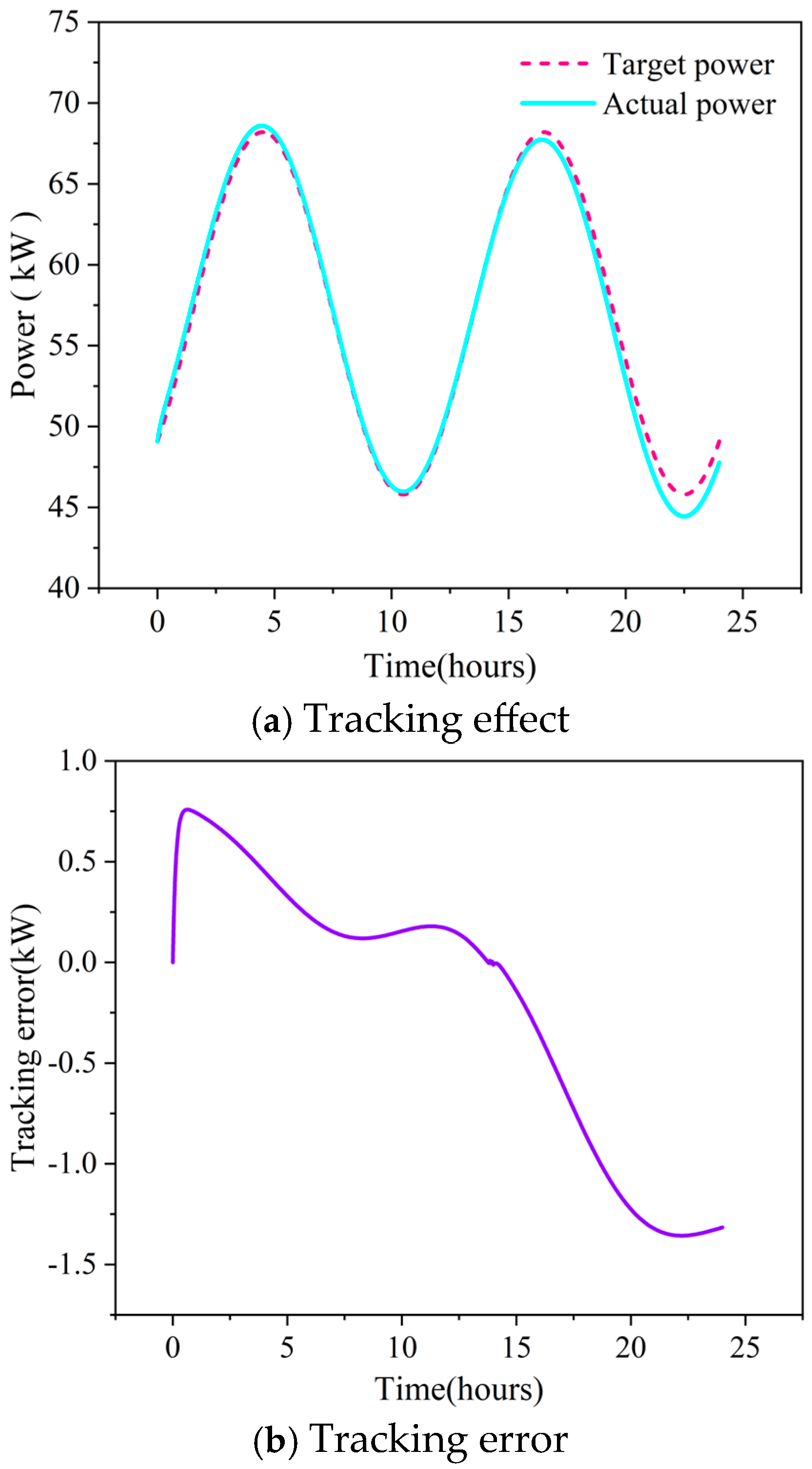

Figure 2a shows the tracking effect of the target power and the actual power. The power tracking performance of the constructed system is one of the core control objectives. DR requires the system to adjust the power consumption according to external instructions. The tracking performance directly reflects the accuracy of the ZNN controller responding to the DR signal. As shown in the figure, the actual power curve of the system in the period achieves a close follow-up to the target curve.

Figure 2b gives the real-time tracking error in the operation process based on the tracking effect of the target power and the actual power. As shown in the figure, the error curve fluctuates around the zero axis, which indicates that there is no steady-state deviation in the power tracking process. When the running time reaches 22.2 h, the maximum tracking error is −1.38 kW, which is less than 1.5% of the rated power, which also verifies the stability of the ZNN controller.

3.3. Dynamic Thermal Performance

The thermodynamic characteristics of the system include two parts: heat storage temperature change and thermal power balance analysis.

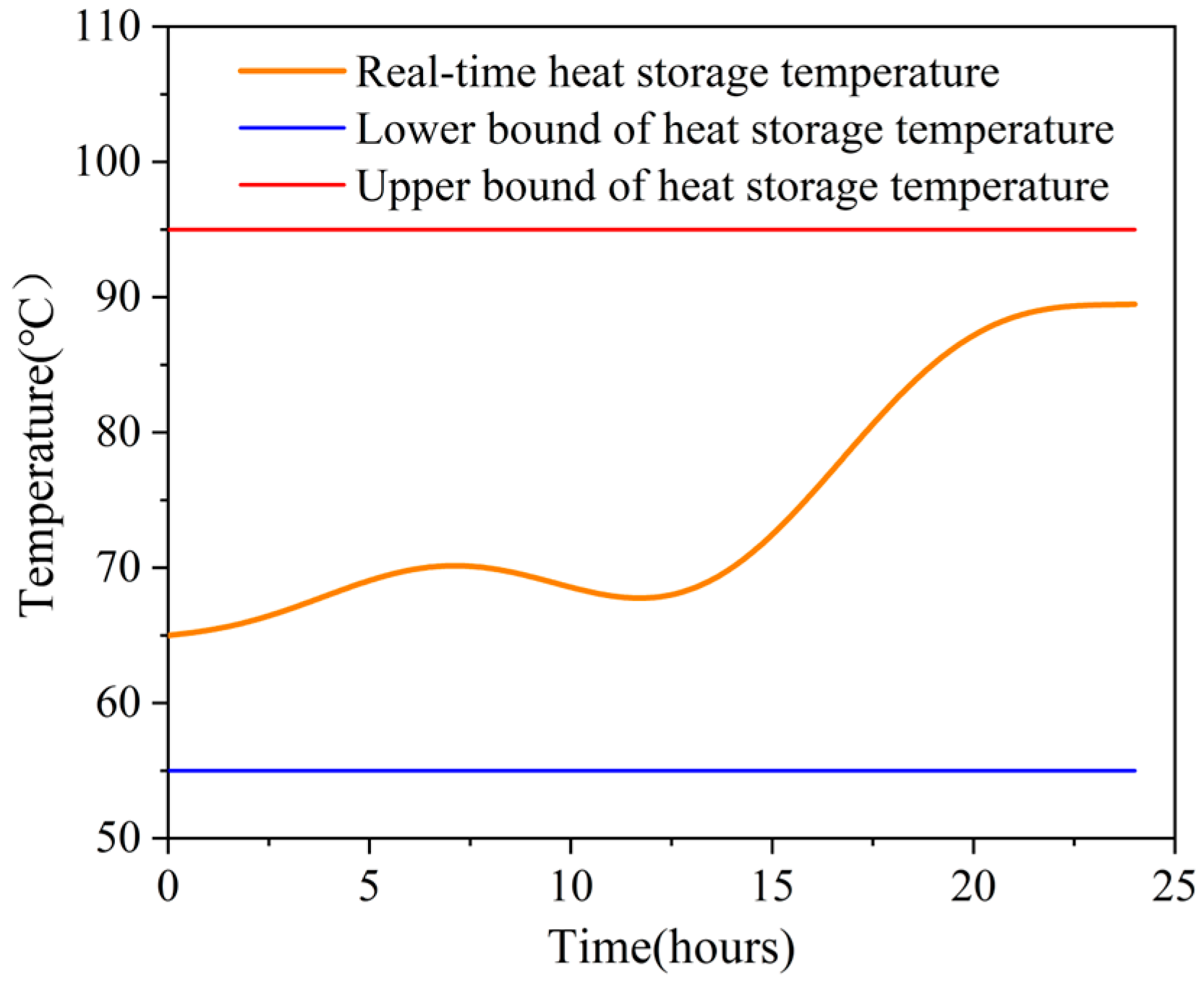

Figure 3 shows the real-time temperature of the heat storage tank during the operation of the system, in which the upper and lower bounds of the heat storage temperature are set to 95 °C and 55 °C, respectively. As shown in the figure, during the operation of the system, the heat storage temperature continued to rise in the first seven hours, rising from 65 °C to 70 °C, followed by a five-hour decline. Then, after 8 h of rapid rise, the temperature reached about 90 °C and gradually stabilized. In fact, the change of heat storage temperature is closely related to the balance of system thermal power.

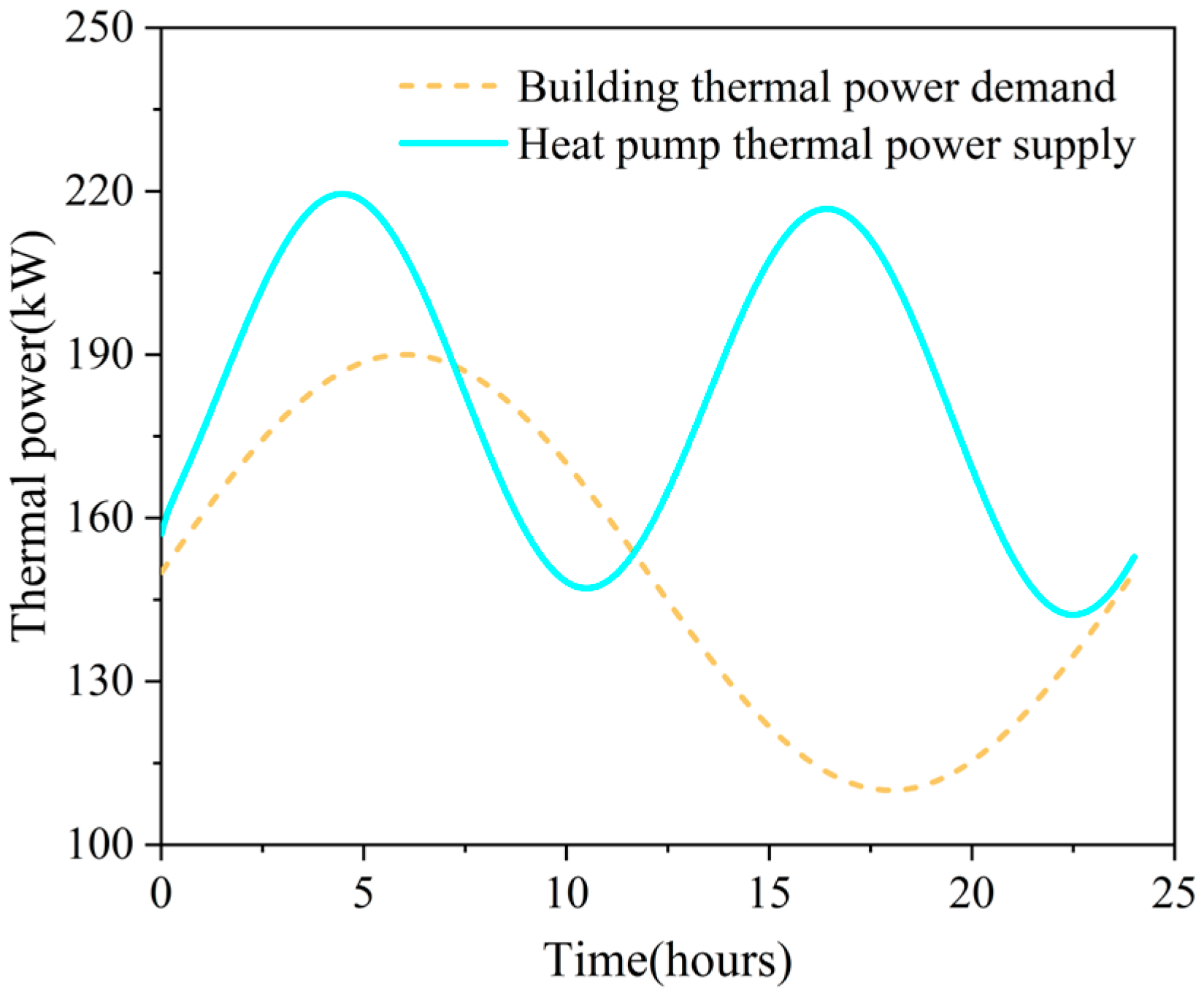

Figure 4 shows the thermal power balance process of the electro-thermal coupling system. Specifically, the real-time heat change of the heat storage tank depends on the relationship between the heat supply of the heat pump and the heat demand of the building. When the heat supply of the heat pump is greater than the heat demand of the building, the excess heat will be stored in the heat storage tank and cause the temperature of the heat storage tank to rise. When the building heat demand is greater than the heat pump heat supply, the heat in the heat storage tank will be used to meet the building heat demand and lead to a decrease in temperature. As shown in

Figure 3 and

Figure 4, during the 0 to 7 h of system operation, the heat supply of the heat pump is slightly larger than the heat demand of the building, and the heat storage tank has a slight temperature rise. In 7 to 11.5 h, the heat supplied by the heat pump cannot meet the heat demand of the building, and the heat storage tank releases heat to the building. In 11.5 to 24 h, the difference between the heat supply and the heat demand of the building increases first and then decreases, so the temperature rise of the heat storage tank also increases first and then decreases.

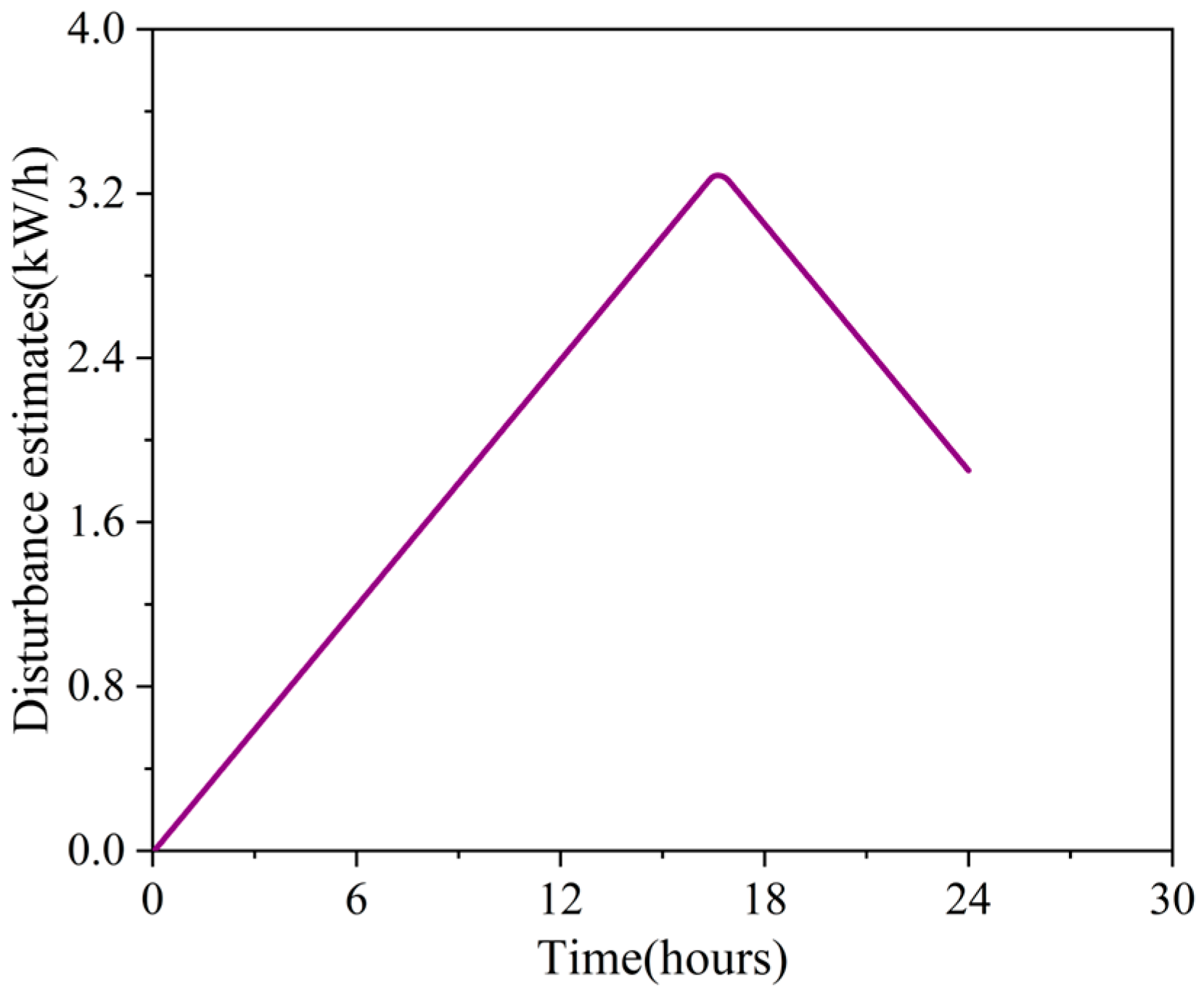

3.4. Disturbance Estimation

Disturbance estimation plays an important role in the control system, which represents the real-time estimation of unknown disturbances. In the ZNN control of the designed electro-thermal coupling system, the disturbance may come from many aspects, such as the uncertainty of the model parameters, the change of the external environment, the unmodeled dynamics and so on. By designing a disturbance observer, the controller can estimate and compensate for these disturbances, thereby improving the robustness and tracking performance of the system.

Figure 5 shows the real-time change of the disturbance estimation value of the system in this paper. As shown in the figure, during the 0 to 16 h of system operation, the estimated value of interference continues to increase and has a maximum disturbance estimated value of 3.29 kW/h at 16.6 h. This is because during the corresponding operating time, the actual power of the system continues to be lower than the target power, that is, a negative error is generated, resulting in a continuous increase in the estimated value of the disturbance. After 16 h, the temperature of the heat storage tank continues to rise, and the output of the heat pump is much larger than the building demand, so the disturbance estimation is reduced.

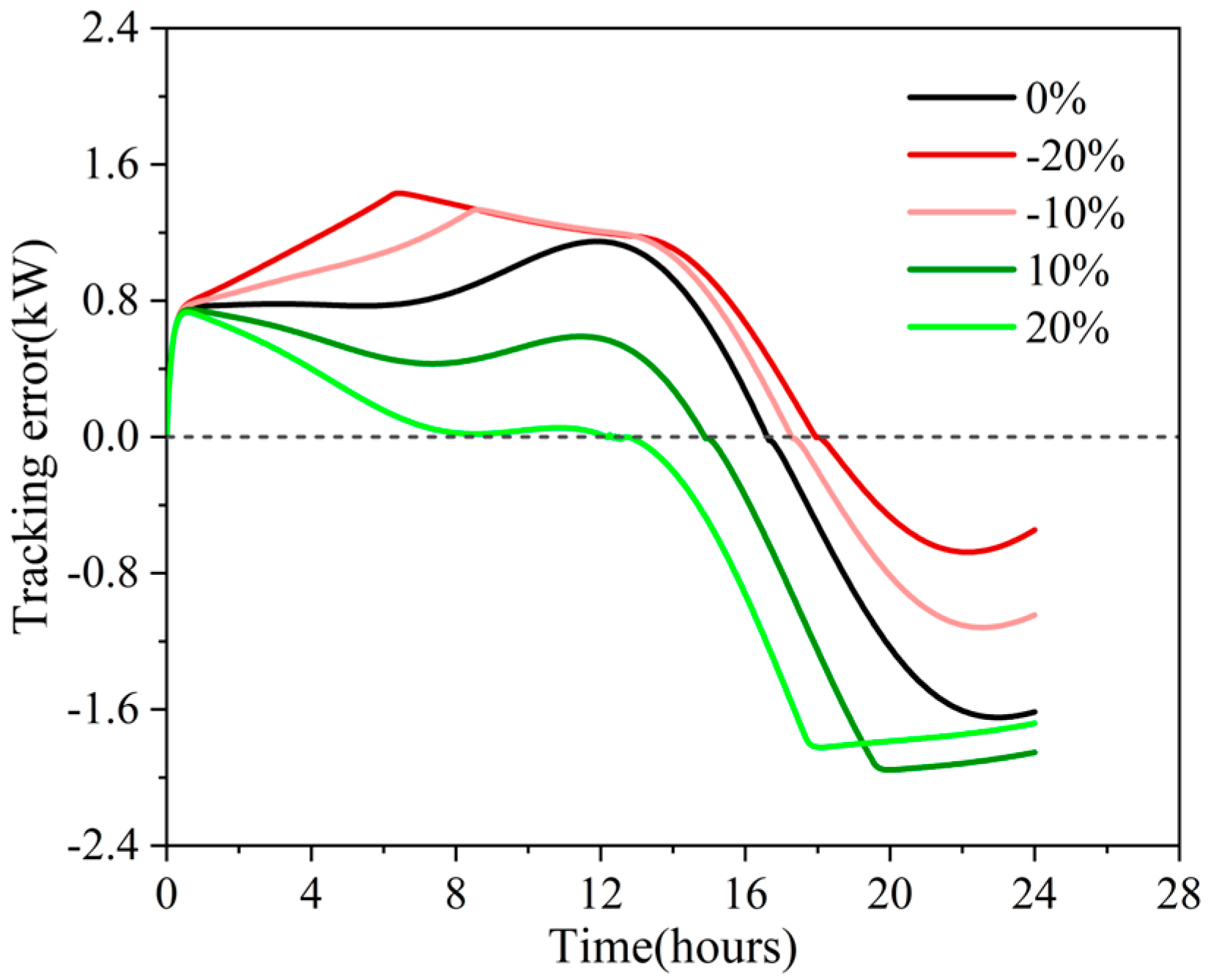

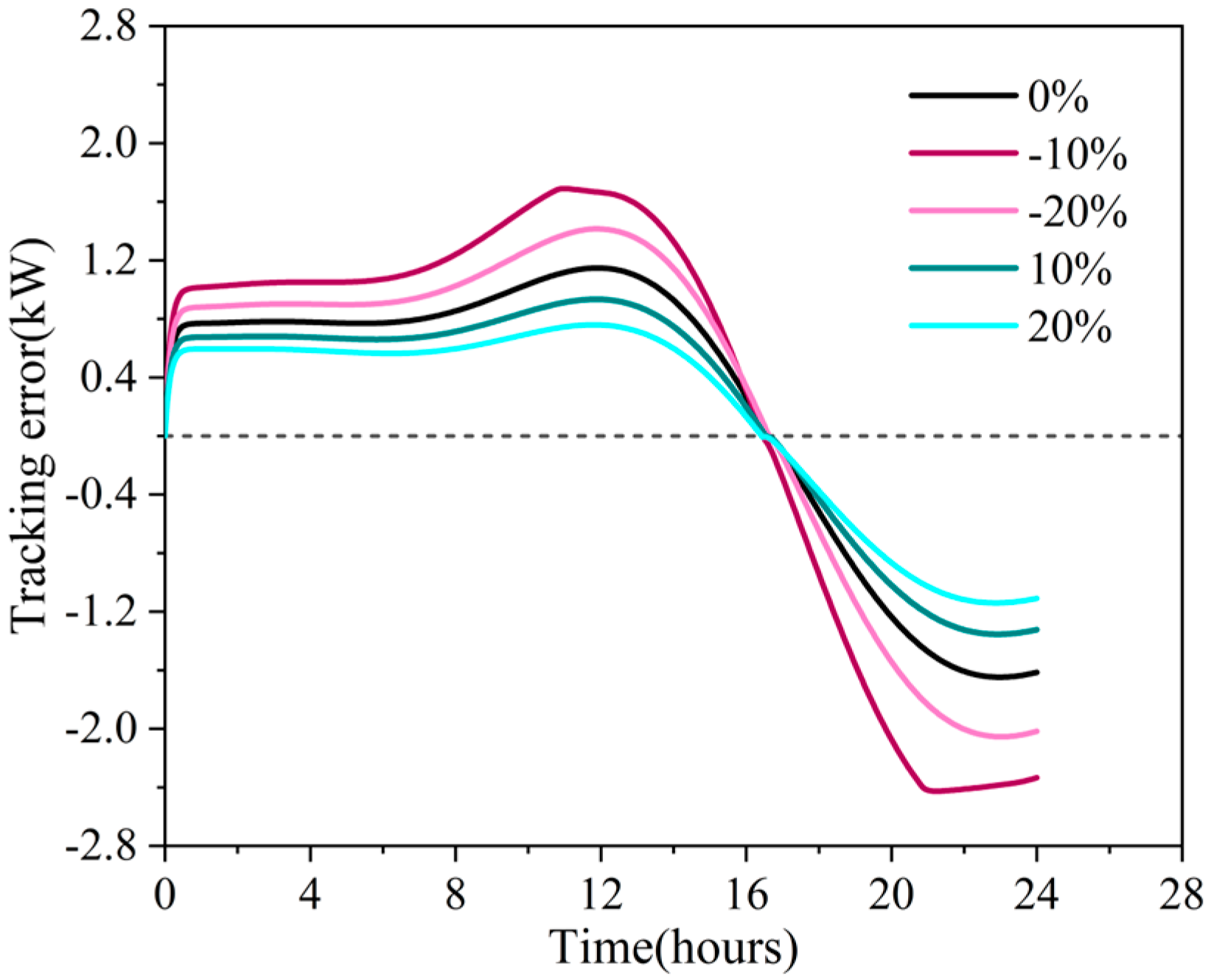

3.5. Robustness Testing

Robustness refers to the ability of the system to maintain its performance index under non-ideal conditions such as parameter changes, model uncertainties, or external disturbances. For the electro-thermal coupling system model designed in this paper, there are often uncertainties in practical engineering applications. For example, the parameters may have measurement errors, the external environment may deviate from the design conditions, and the equipment performance may decline. Therefore, in order to verify whether the electro-thermal coupling system under the ZNN control method can work reliably under the condition of uncertainty and avoid serious degradation or even instability of the system performance caused by model mismatch, this section tests the robustness of the designed ZNN controller. Firstly, in the part of the parameter disturbance setting, the two key parameters of the coefficient of performance of the heat pump and heat capacity of the heat storage tank are selected as objects, and the error changes of the system under the condition of parameter uncertainty are analyzed, respectively.

Firstly, the tracking error of the system is analyzed in the case of COP disturbance.

Figure 6 shows the real-time tracking error of the system in the case of a COP disturbance of 0.8–1.2. It can be seen from the diagram that when the COP is reduced by the disturbance, the tracking error of the first half of the system operation process increases, and the second half decreases. When the COP increases due to the disturbance, the tracking error in the first half of the system operation process decreases, and the tracking error in the second half increases. It can be seen from the diagram that when the COP is reduced by the disturbance, the tracking error of the first half of the system operation process increases, and the second half decreases. When the COP increases due to the disturbance, the tracking error in the first half of the system operation process decreases, and the tracking error in the second half increases. This is because when the COP is reduced, in order to meet the heat load in the early stage, a higher electric power is required, and it may exceed the set target power, so the tracking error is large, and the heat load is reduced in the later stage, the required power is small, and the error response is reduced. When the COP increases, the higher COP means that only a small electric power is needed to meet the heat demand, so the actual power is lower than the target power, and the heat load is reduced in the later period, but the reduction in the target power lags behind, so the negative error is large. In addition, when the actual COP is greater than the nominal COP, the system has a high efficiency of heat generation, so the electric power can be reduced faster when the heat load decreases, and the error changes from positive to negative faster.

Figure 7 shows the real-time tracking error of the system under the condition of heat capacity disturbance of the heat storage tank. With the decrease in the heat capacity of the heat storage tank, the tracking error of the whole period of the system operation will increase, and the time node when the tracking error changes from positive to negative is not affected by the heat capacity disturbance. The reason for the above phenomenon is that when the heat capacity of the heat storage tank decreases, the temperature changes faster, resulting in a greater change in the feedback term of the heat storage state in the system model and interfering with the power tracking control, thereby increasing the tracking error. In addition, the positive and negative conversion of the tracking error in the control system means that the relative size of the actual power and the target power changes, which depends on the change of the heat load and the change of the electricity price. The heat capacity disturbance coefficient does not change the time series characteristics of the building heat load and the demand response target power, so the turning time is independent of the heat capacity parameter disturbance.

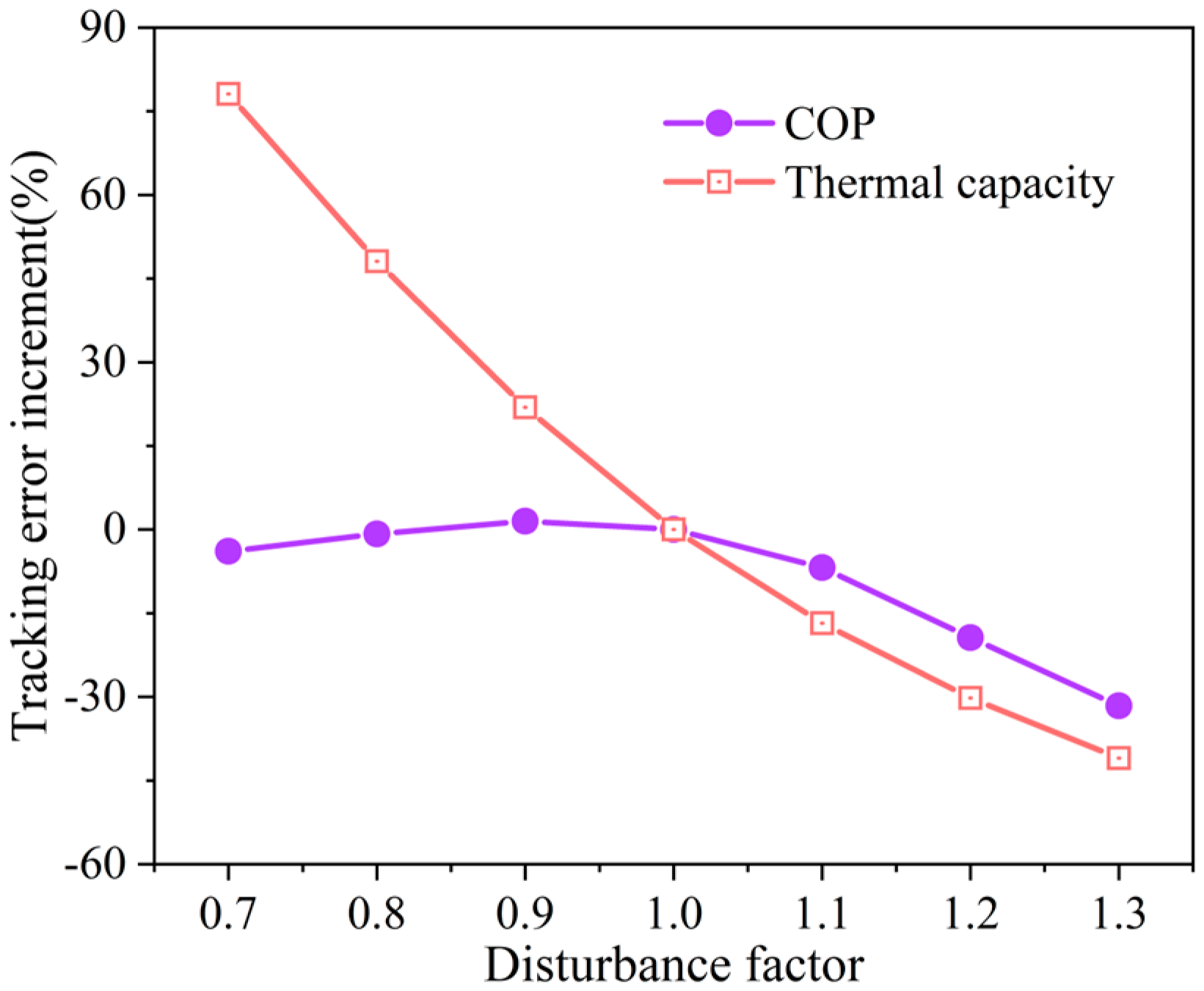

In order to more intuitively and comprehensively show the influence of the disturbance coefficient of the heat pump COP and the heat capacity of the heat storage tank on the tracking error of the ZNN controller of the system,

Figure 8 shows the change of the average tracking error during the operation of the system under different disturbance coefficients. It can be found from the figure that when the COP of the heat pump is disturbed, the average tracking error of the system is less affected. When the COP disturbance coefficient reaches 1.3, the average tracking error reduction is 31.6%, and when the COP disturbance coefficient is 0.7, the average tracking error reduction is only 3.9%. However, the disturbance of the heat capacity of the heat storage tank has a great influence on the average tracking error of the system. When the disturbance coefficient of the heat capacity is 0.7, the increase of the average tracking error reaches 78.1%, and when the disturbance coefficient of the heat capacity is 1.3, the decrease of the average tracking error also reaches 41%.

Table 2 quantitatively summarizes the system’s robustness under parameter disturbances. For COP variations, the tracking error shows a non-monotonic trend: higher COP values (1.1–1.3) significantly reduce MAE, as improved thermal efficiency allows better power matching during low heat-load periods. Conversely, for thermal capacity disturbances, the system exhibits higher sensitivity: reduced capacity (0.7–0.9) increases MAE by 21.9% to 78.1%, due to accelerated temperature dynamics interfering with power tracking control. In addition, in practical engineering application scenarios, due to changes in external conditions, most of the disturbances to the COP of the heat pump and the heat capacity of the heat storage tank will lead to performance degradation. Subsequent research should focus on robust control under conditions of system performance degradation. Finally, to validate the superiority of the proposed ZNN approach, a brief comparative analysis with a conventional PID controller was conducted. As shown in

Table 3, the ZNN controller achieved a mean absolute tracking error of 0.918 kW, while the PID controller reached 2.857 kW, representing a 67.9% improvement in tracking accuracy. Furthermore, the maximum tracking error for the ZNN controller was −1.38 kW, compared to −4.36 kW for the PID controller. The superior performance of the ZNN controller can be attributed to its inherent ability to handle time-varying parameters and its model-based nature, which explicitly accounts for system dynamics. In contrast, the PID controller struggles to adapt to the rapidly changing target power and system conditions characteristic of demand response scenarios.

4. Conclusions and Prospects

4.1. Conclusions

As a kind of neural network dedicated to finding the zero point of the equation, the zeroing neural network has played an indispensable role in the field of solving time-varying problems through the continuous research and exploration of researchers in recent years. This study verifies the significant advantages of the ZNN in time-varying demand response, which still maintains low error tracking and strong robustness in high dynamic electricity price and heat load scenarios and provides a new method for the real-time control of complex energy systems. In the process of building energy management, the time-varying demand response problem cannot be ignored. Based on this, this study designed a set of building electric–thermal integrated systems using the ZNN control method and carried out model building, control setting, simulation, and performance analysis for the designed system. The main results are as follows:

(1) For the electric–thermal integrated system of building energy management, the thermodynamic dynamic model is constructed, the ZNN control law is defined, the corresponding demand response mechanism is established, and the robustness design is also carried out.

(2) Based on the constructed model and ZNN control law, the system’s electricity price response, power tracking performance, dynamic energy storage performance, and interference estimation are analyzed. The results show that the target power of the system is well adapted to the real-time electricity price, and there is only a slight response lag. The ZNN control achieves a very low tracking error, and the maximum tracking error is only −1.38 kW. During the operation of the system, the heat storage tank releases heat to cool down when the building heat demand is higher than the heat output of the heat pump, and absorbs heat to heat up when the heat output of the heat pump is higher than the building heat demand; the real-time disturbance estimation value of the system is relatively small, and the maximum disturbance estimation value is 3.28 kw/h after 16.6 h of operation.

(3) The robustness test of the designed system is carried out to clarify the change of tracking error under the condition of system uncertainty. The COP of the heat pump and the heat capacity of the heat storage tank are used as parameters for testing. The results show that the system can still maintain high robustness when the COP is disturbed. When the COP disturbance parameter is 1.3, the tracking error is reduced by 31.6%. Relatively speaking, the tracking error fluctuates greatly when the heat capacity of the heat storage tank is disturbed. The smaller the heat capacity, the greater the tracking error. When the heat capacity disturbance parameter is 0.7, the tracking error increases by 78.1%. In addition, a comparative study with traditional PID control is carried out. The results show that the ZNN has significant performance advantages in time-varying demand response scenarios.

4.2. Research Prospects and Challenges

While the simulation results demonstrate significant potential, the real-world deployment of the proposed ZNN framework faces several practical constraints. These include (1) the dependency on accurate system identification of building thermal dynamics, which can be resource-intensive for existing buildings; (2) the requirement for reliable, real-time sensor data (e.g., storage temperature, heat load), an infrastructure absent in many legacy buildings; (3) the challenge of computational integration with industry-standard Building Management Systems (BMS) via protocols like BACnet or Modbus; and (4) the necessity for extensive field validation to prove long-term reliability and economic benefits to stakeholders. Subsequent research can further employ advanced ZNN models with better convergence and stronger robustness to solve a variety of time-varying problems in more complex new integrated energy systems.