Abstract

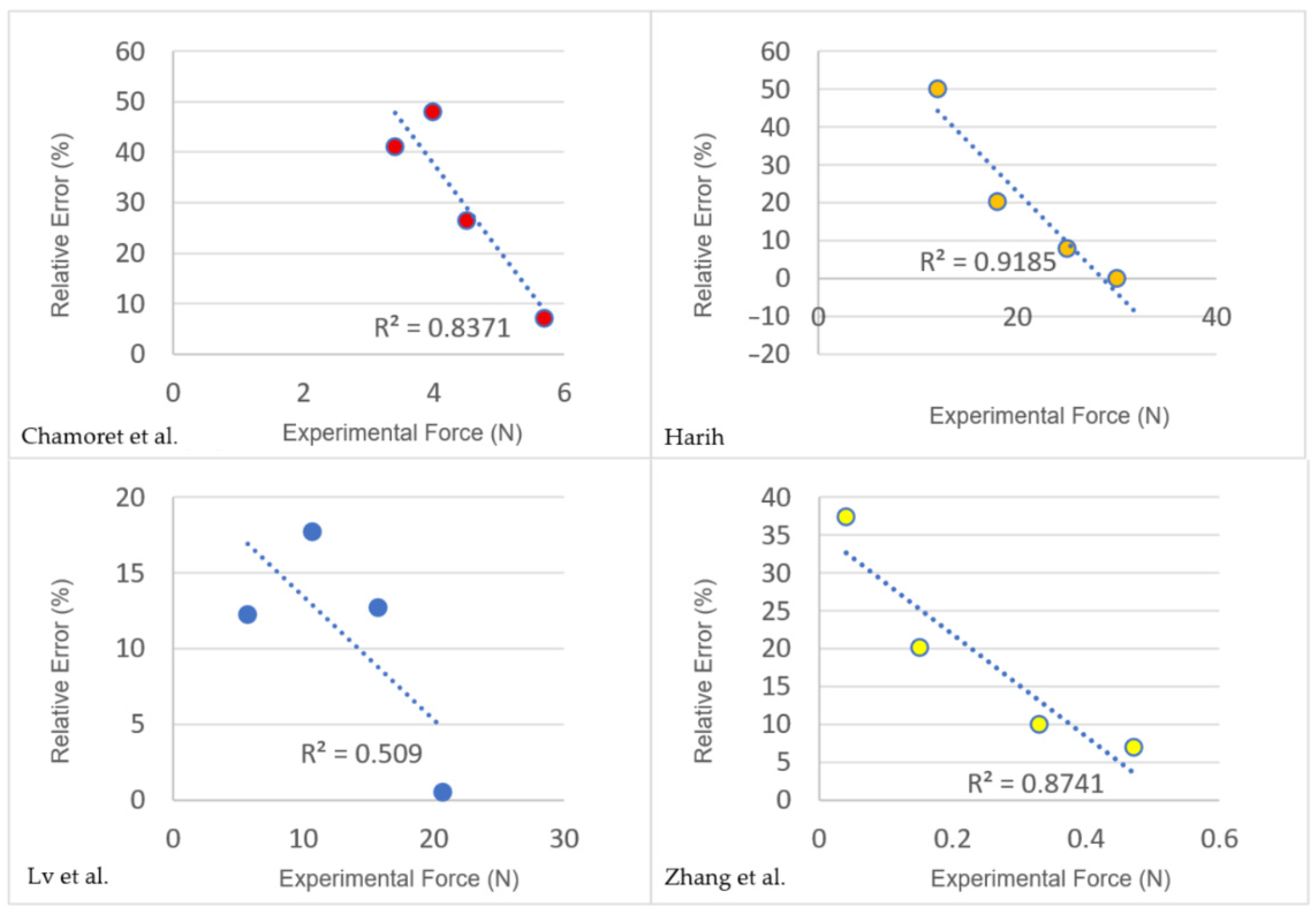

Glove fit is crucial for both wear comfort and safety. A well-fitting glove can be realized by combining anthropometric hand measurements from three-dimensional (3D) scanning with the finite element method (FEM). This study reviews how accurate hand measurements and model interactions can be achieved to improve design and enhance protection. A total of 26 articles were selected for an integrated analysis and evaluation. The results indicate an increase in accuracy in 3D scanning with greater resolution, in which the optimum value has not been discovered. While the numbers of landmarks (ranging from 14 to 50) depend on the specific purpose, they do not directly correlate with precision. On the other hand, the authenticity of the FEM is closely related to the number and size of the finite elements, with simulation error decreasing as the applied force increases (R2 > 0.78). It is also noteworthy that the image-based approach, motion state, and model used in the FEM do not significantly affect precision. Both technologies provide a comprehensive approach for glove design, as they combine accurate anatomical data with predictive modeling of mechanical performance and fit. Yet, challenges are identified, such as divergent standards in data retrieval and low accessibility, which inhibit the application of these two techniques in glove construction. Future studies should address the issues of improving scanning coverage, standardizing the data collection models, expanding glove application in different fields, and adopting artificial intelligence to improve the design, construction, or manufacture of gloves.

1. Introduction

Gloves support users with various functions like compression and musculoskeletal protection, so that they can participate in certain sports or activities that expose them to injury more safely. The performance of the users also greatly depends on the fit and wear comfort of the gloves. As such, the construction of gloves and sizing can be optimized through anthropometric hand measurements and simulation. Nevertheless, current sizing processes cannot accommodate a large number of customers, due to the high variance in palm size and thickness. Also, the sizing accuracy and performance of the glove can be distinctly affected by excessive material in the stressed area during sports activities or an improper fit [1]. For instance, the gap between the gloves and palm, caused by oversized gloves, reduces the perceived sensation when grasping a target due to the ill-fitting or suboptimal material of the gloves, which also results in ineffective force transmission during grasping [2]. These further trigger slippage and injuries when grasping objects. Thus, a proper glove fit is essential for optimal performance.

Current technology enables designers to obtain more accurate measurements of the palm, with techniques such as 3D scanning. These innovative means enable designers to capture the hand dimensions and muscle changes across different phases of motion, thereby creating a practical visualization of the palm to provide a better fit for glove construction compared to abstract images or traditional measurement instruments. Compared to traditional measurement methods, the techniques provide more accuracy and enhance efficiency due to minimal human intervention or high data variance [3].

The simulation of the hand by using the finite element method (FEM) has significant implications in glove construction: particularly in therapeutic and biomedical applications. A pre-evaluation of glove performance can be performed by creating a visual model to simulate the pressure applied [4,5]. The use of data capture techniques—for instance, FEM—enables the simulation of the hand with the digitized hand formed by meshes and a virtual skeletal structure. On the other hand, the data collected can be used to analyze the interaction between the hand and external objects. Evaluation of the protection from wearable devices like gloves and orthoses, or stress with different movements of the hand, can be performed. This benefits the analysis of the hand strain ratio by visualizing the compressed or deformed areas. The pattern-making and construction of the gloves can also reference the finger movements and skin deformation, acquired by the conversion between the 3D models of finite elements and flattened 2D surfaces [4,6,7,8].

These technologies, however, have notable limitations. Three-dimensional scans often overlook hand–object interactions and the practical glove contact data, while FE models cannot accurately represent the complex, non-linear behavior of the soft tissues and muscle forces. Although previous research has advanced hand measurements and simulation, the methodologies remain fragmented, with limited integration or a systematic review. To address these knowledge gaps and improve glove designs, this paper provides a comprehensive review of the techniques for collecting anthropometric data on the hand through scanning and FE simulation, and compares their applications, mechanisms, and accuracy. This analysis aims to guide future research and integrated approaches for glove construction.

2. Materials and Methods

This review includes examining the different approaches in hand anthropometry, including 3D scanning and numerical simulation, by using the FEM, along with an assessment of their techniques and applications. A wide scope and the latest technologies in the two areas are covered, while relevance, timeliness, and objectivity are ensured. Research is conducted with the Web of Science (WoS), Scopus, and PubMed databases to provide a broader and unbiased view, while focusing on the hand measurement techniques or technologies and the digital simulation of hands. A large number of research studies are reviewed with the selection criteria and eligibility is determined according to the inclusion criteria (shown in Table 1), to provide dedicated and associated information.

Table 1.

Inclusion criteria for the articles of the review.

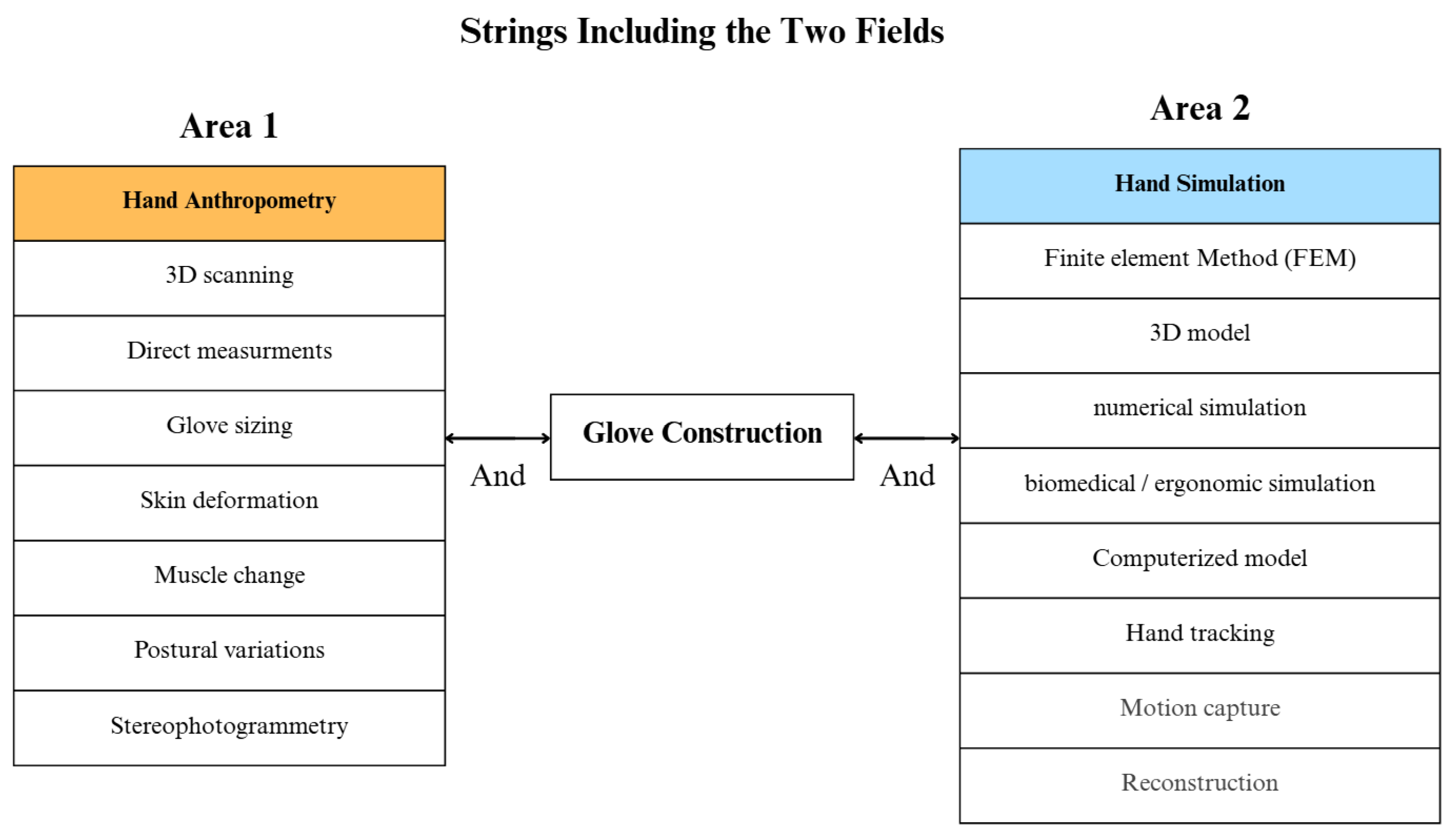

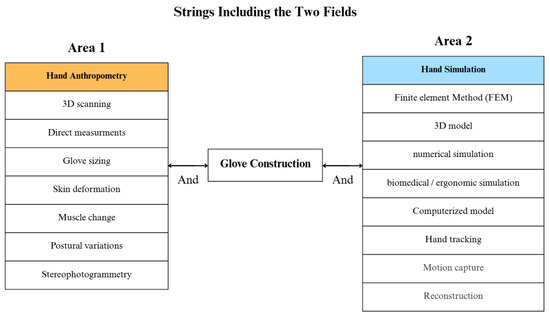

Focusing on the development of the anthropometry and simulation of the hand, two major components are selected with the intention to enhance the coverage of the literature review, which are as follows: (1) hand anthropometric measurements obtained by 3D scanning and (2) simulation of the hand by using FEM. The publication range is set from 2015 to 2025 to ensure adequate coverage and current articles. The search begins with a keyword query on the WOS, Scopus, and PubMed databases by using two search string areas that pertain to hand anthropometry and glove material, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Keyword query.

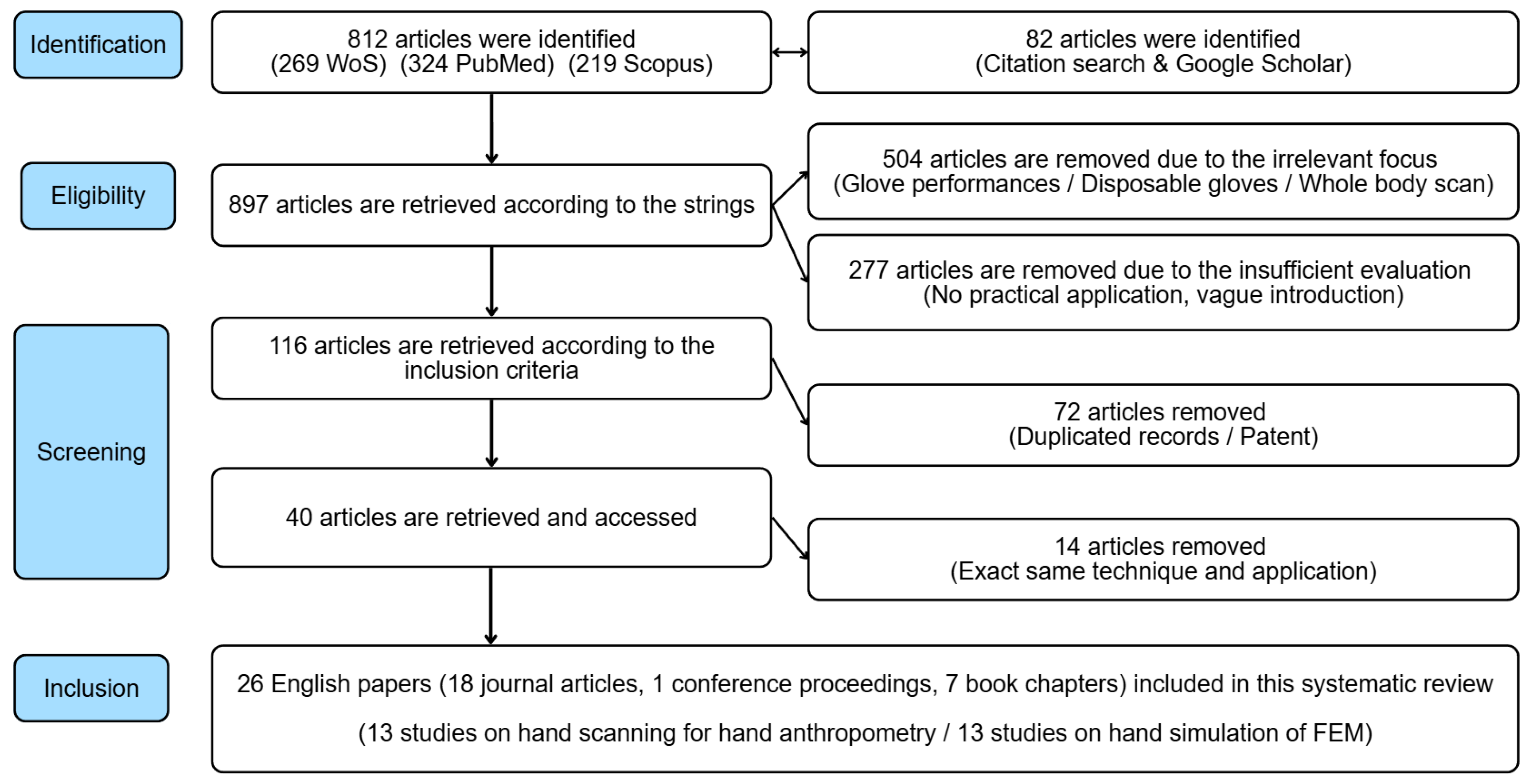

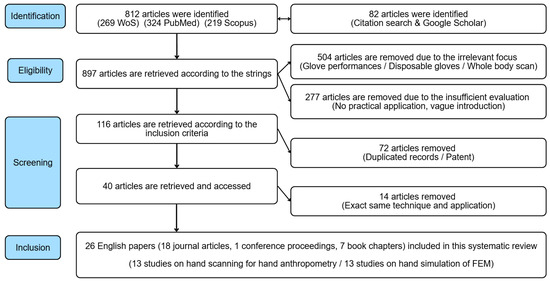

After applying the query in Figure 1, a flow chart is created, as shown in Figure 2, which shows that 812 articles are identified in the three databases, with patents excluded. Also, 82 articles are retrieved with the same settings in Google Scholar and a citation search. Due to their irrelevance and lack of evaluation, 504 and 278 articles were removed, respectively. Duplicate articles were also removed among the remaining 112 papers, which resulted in 40 articles. Finally, papers that used the exact same techniques and applications were removed, which provided a final number of 26 English-language articles.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of selection of articles.

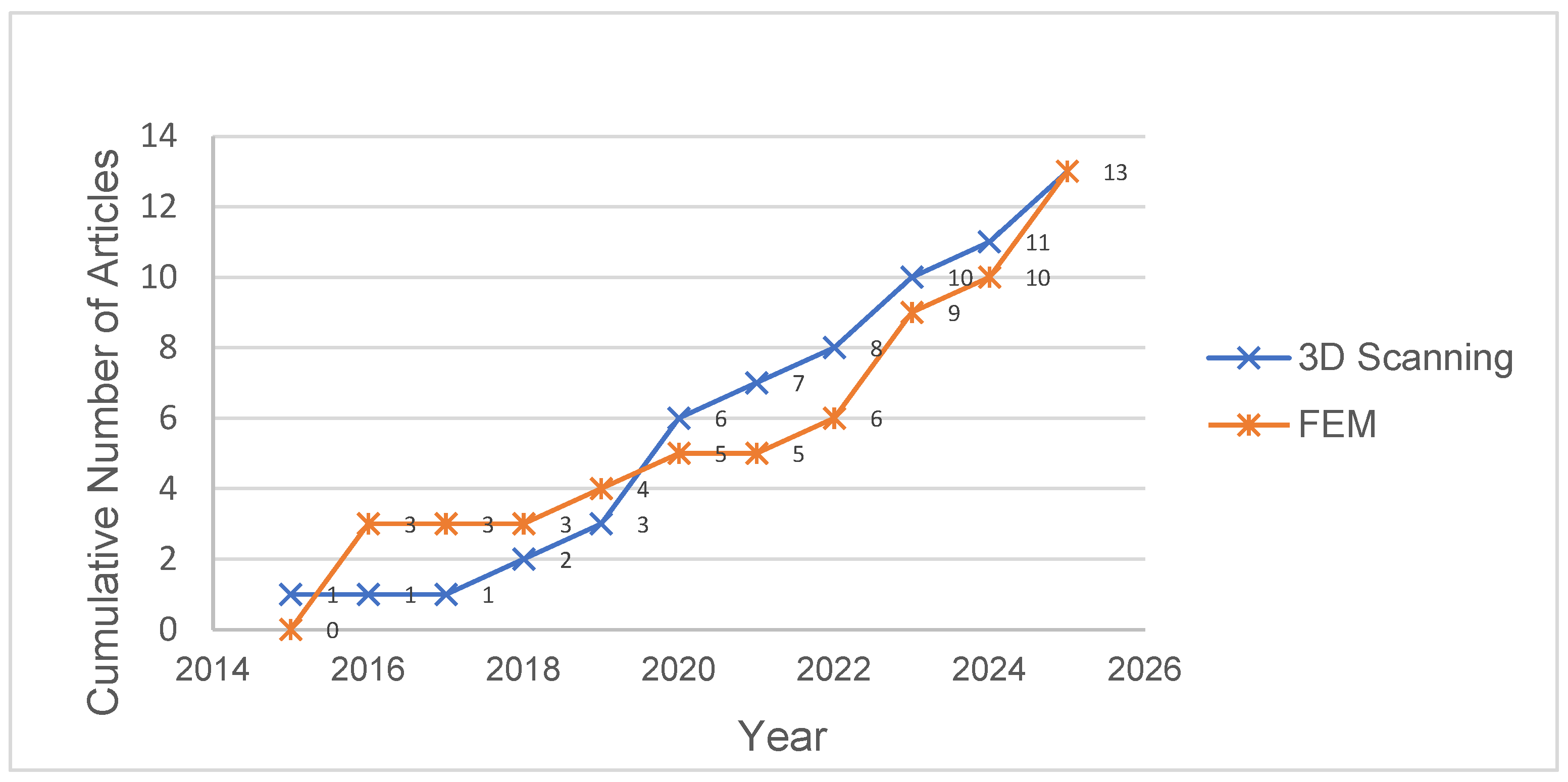

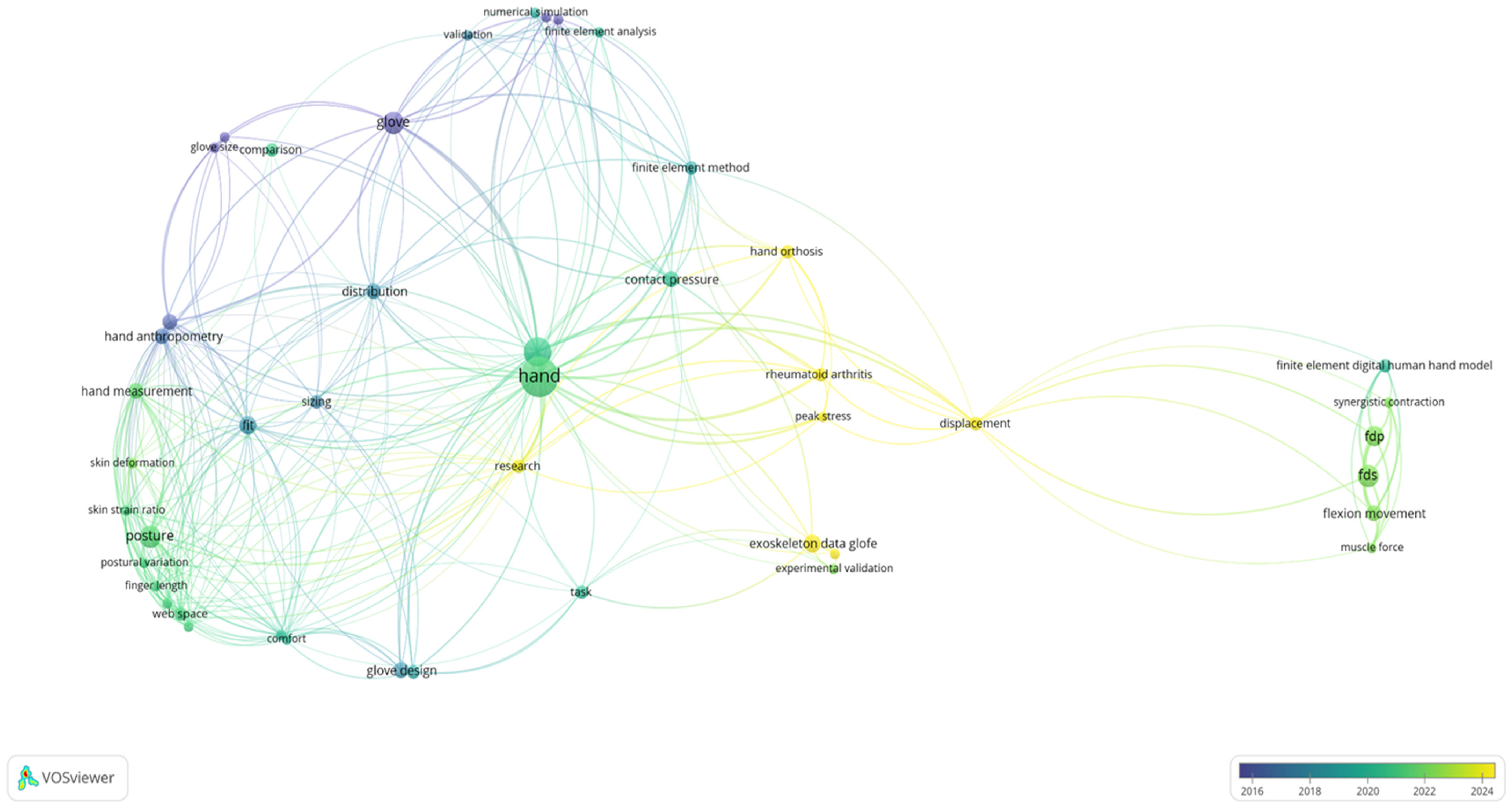

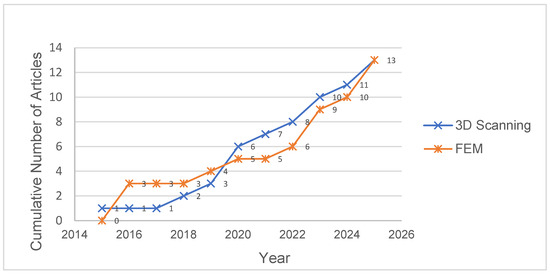

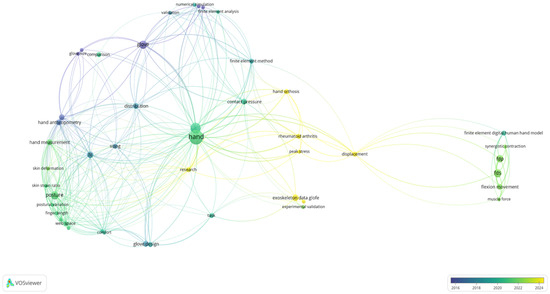

As shown in Figure 3, from 2015 to 2025, there has been a notable increase in research publications related to 3D hand scanning and FE hand models. The number of articles in these areas grew by approximately 50% over the decade, indicating a rising interest and advancement in these technologies. This growth reflects ongoing efforts to improve image quality and accurately capture complex anatomical features of the hand and fingers, especially in dynamic situations, and to reduce the simulation errors in hand models. Systematic reviews and meta-analysis (PRISMA) statements and the trend analysis with the VOS viewer V.1.6.13 (Leiden University’s Centre for Science and Technology Studies, Leiden, The Netherlands) are used for the evaluation of topics and keywords among the research screened. During the process, full counting was used and the minimum keyword occurrence was set to two to enhance the relevance. The results and keywords are shown in Figure 4. In total, 45 keywords are filtered, in which those with higher occurrence and more relevance are shown with larger circles. It can be observed that studies on hand measurements extend to examining ‘skin deformation’ and ‘postural variance’ from 2020 to 2023. On the other hand, the terms ‘hand orthosis,’ ‘rheumatoid arthritis,’ and exoskeleton gloves’ are the most recent keywords (2025) associated with the FEM.

Figure 3.

Publication trend of the articles of the two areas from 2015 to 2025.

Figure 4.

Keyword analysis chart of reviewed articles with publication trend.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Hand Anthropometry Measurements by 3D Scanning

Table 2 and Table 3 list the studies that applied 3D scanning for collecting hand measurements and the corresponding scanners used. Some papers include comparisons with 2D scanning in terms of accuracy and found that 2D scanning is less accurate (8.7–16% relative error) than 3D scanning (0–8%), despite its advantages in terms of cost and time (195% faster than 3D scanning) [9]. Two-dimensional scanning cannot measure the curve and silhouette of the hand, but only the straight distance, while 3D scanning captures detailed surface and depth information by projecting structured patterns onto the hand with customizable landmarks for precise, multi-angle anthropometric measurements and actions like grasping and pinching, transcending 2D scanning [3,10,11,12,13]. While 3D scanning also compares the stress–strain ratio of the hand skin in different levels of grasping and splaying, which is mainly located in slant webs (29.13–51.38%) and metacarpal (37.64–102.77%), providing clearer measurements under dynamic poses [6,12]. This is essential to construct gloves with a good fit that will not hinder the hand in different circumstances. Kwan et al. [12] also found that conventional gloves designed with the use of hand dimensions from a finger-splayed posture can restrict finger movement during dynamic poses, such as bending. Chen et al. [14] further capture hand contact data with objects in identifying contact areas during grasping. The data contributes to the glove design, especially sport or protective gloves, where extra protection is required in high-stress areas. For example, foam paddings or multiple layers can be added to reduce shock and pain in specific parts of the glove [15,16].

Table 2 displays the partial scanners with precision involved in the studies. The resolution is related to precision. A lower error is shown in Artec Leo 3D scanners (1.16–1.46%), which have a relatively higher resolution (2.3M pixels), accompanied by greater accuracy. The claim that high resolution detects dimensional variations in skin or muscle during different hand gestures, which can range from 0.02% to 30.85%, approximately 0.01–300 mm, to produce authentic hand surfaces with a desirable quality of 3D images with the high resolution of the scanners (up to 2.3M pixels) is strengthened [12,16,17]. Notably, CT scanning has similar precision in collecting surface dimensions compared with structured light, yet the resolution required is left unclear [8], while 38% of the articles include the Artec Eva 3D scanner, which has a lower resolution and scanning speed, considering the lower cost. Although a higher cost is presented for greater accuracy and speed [13,17,18,19], few articles compare their precision practically in terms of dimension and the time required.

The number and placement of landmarks can be adjusted based on the research focus, ranging from 14 to 50 landmarks, which can be positioned on the sides of fingers or web spaces, in stances like measuring skin deformation and contact data [11,12]. An increasing number of landmarks may more effectively detect subtle changes related to muscle activation during dynamic gestures, such as grasping, especially over shorter skin distances [6,12]. However, there is no validation of the relationship between the landmark number or distribution and precision, due to the lack of experimental data obtained by direct measurement or diverse study purposes, like the mass collection of hand sizes and skin strain ratio [12,15,19,20]. There is no relationship discovered between the landmark numbers and the sample number or age. A total of 46% of the studies involve subjects younger than 40, while only 30% of the studies cover the opposite. The studies that involve younger subjects aim to mainly analyze the muscle and skin changes, as the group is more likely to wear gloves in sports or industries. Yet this may cause difficulties in designing gloves for the older groups in terms of rehabilitation, due to the lack of analysis and measurements on their hands. One limitation is that the studies do not include the evaluation of diverse hand sizes’ anthropometry, nor the differences between hands of different ethnicities, which may affect the glove sizing globally.

There are also limited articles discussing the training of the various scanners with software, leaving the resources required to train or learn unclear [19]. Since the scanners are dependent on software, such as the mesh configuration by Rapidform XOR or Mesh and the comparison by CloudCompare, the time for training to obtain the integrated data is increased. Considering that a higher resolution of the scanners and operating various software is essential for in-depth analysis of the hand anthropometry, the inconsistency and varying resources of time and cost required may be a challenge for small or medium-sized research.

Table 2.

Basic information about the 3D scanners involved in the studies.

Table 2.

Basic information about the 3D scanners involved in the studies.

| Scanners | Relative Error (%) | Price (USD) | Resolution | Scanning Speed | Handheld Supportive | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Artec Eva 3D | - | 19,800 | 1.3 megapixels, up to 0.1 mm | 16 FPS | Yes | [7,9,11,12,20] |

| Artec Leo 3D | 1.16–1.46 | 34,800 | 2.3 megapixels, up to 0.1 mm | 80 FPS | Yes | [17,18] |

| Infoot | - | - | up to 0.5 mm | Not disclosed | No | [6] |

| Occipital Structure Sensor | 5.08 | 527–995 | VGA (640 × 480)/1.3 megapixels, up to 1 mm | 30–60 FPS | Yes | [17] |

| Gemini Structured Light Scanning | 3.94 | - | up to 0.05–0.1 mm | Not disclosed | No | [8] |

Table 3.

Summary of reviewed papers (including anthropometric measurements acquired through scans).

Table 3.

Summary of reviewed papers (including anthropometric measurements acquired through scans).

| Techniques | Hand Posture (s) | Machines | Sample Size | Paper Focus/Topic | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26 landmarks on the palm | Grasping, fingers splayed, fingers closed | Occipital structure sensor attached to a tablet, Anthroscan | 15 male and 15 female university students, no hand injuries | Hand anthropometry under motion | [13] |

| Fingers splayed | 30 females, no limits on age | Fitting of certain sports gloves in 4 sizes for females | [1] | ||

| 24 landmarks on the hand scanned with plaster hand models | Fingers splayed | Gemini structured light scanning system, computed tomography (CT) scanning, direct measurement | 6 male and 4 female age 26–35, no hand injuries | Efficiency and precision of 3D scanning compared to CT scanning and direct measurement | [8] |

| 47 landmarks on palm (joints and finger web) | Fingers splayed, relaxed, ball grasp | Artec Eva 3D scanner and Rapidform XOR software | 20 females and males, age 18–40, no hand injuries | Tracking the hand measurements and skin deformation in dynamic poses for designing gloves | [12] |

| A few landmarks placed near the finger web | Fingers closed | Artec Eva 3D scanner, with CloudCompare and MeshLab | One female aged 25, no hand injuries | Determination of dimensional allowances by comparison between gloved and bare hand | [7] |

| No landmarks, take hand length and hand breadth metacarpals, according to ISO 7250 [21] | Fingers closed | Harpenden Anthropometer, measuring tape, Artec Eva 3D scanner, Brother 2D scanner | 13 males and 12 females, age 25–45 | Precision, reliability, cost, and complexity among direct measurements, 2D and 3D scanning | [9] |

| 17 landmarks on the dorsal palm and wrist | Fingers splayed, slight grasping, power grasping | INFOOT scanner, with calculations performed by Geomagic Studio 12 | 13 females, age 40–65, M size, no hand injuries | Skin deformation behavior during dynamic hand poses | [6] |

| 14 landmarks on a plaster hand | Fingers splayed | Bone calipers, measuring tape, Occipital Structure Sensor, Artec Leo 3D scanner | 12 subjects, no limits on age or gender | Precision of different 3D scanning methods compared to direct measurement | [17] |

| 50 landmarks on the dorsal side of the hand with scanning | Fingers splayed, cylinder grasped | Artec Eva 3D scanner with Geomagic Studio | 111 females, age 18–26, no hand injuries | Relationship between grasping and hand skin deformation | [11] |

| No landmarks, stain left on cotton gloves after grasping objects with splayed hand is scanned | 52 objects grasped | EinScan 3D scanner, with the painted areas separated by mapping texture and point clouds, which will be marked on 3D-printed hands | 8 males and 4 females, age 20–30, no hand injuries | Development of technique of Ti3D-contact to obtain hand contact areas | [14] |

| Landmarks in ISO 7250 [21] | Fingers splayed, fingers closed | Artec Eva 3D scanner with Geomagic Wrap | 468 males and 469 females, age 22–60 | Collection of hand dimension of large-scale Chinese population | [20] |

| 23 landmarks on the hands, which represent 7 specific measurements | No specific poses are mentioned | Artec Leo 3D scanner, with 7 measurements, auto/semi-auto measured by Anthroscan | 15 of 800 subjects, no limits on age or gender | Precision of the auto/semi-auto measurement of the hand by 3D hand scanning | [18] |

| No specific landmarks with a 3D printed hand model (age 19, male) | Finger splayed | Structure Sensor Pro for iPad, with 3D models shown with Meshmixer program | 42 untrained and 45 trained university students | Precision of acquiring hand measurements between trained and untrained students | [19] |

3.2. Hand Simulation by FEM

The FEM simulates and captures both static and dynamic deformation and the strain of the hand under pressure and motion by reconstructing the hand with meshes that follow the contours and curves of the target [22,23,24]. Table 4 summarizes the applications and attributes of the reviewed FEM studies. Its application varies from analyzing contact data while grasping and pinching objects to the stress–strain ratio of the hand under conditions like gloves and orthoses [4,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. During grasping, for example, stress is mainly distributed in the areas of the finger bases, distal, and proximal phalanges when holding spheres, thenar convex area when grasping cylinders. The peak force is 18–125% higher for spheres [24,34]. Wei et al. [24] found that subcutaneous tissues (0.95–9.4%) deform more than the skin (1–8%) while grasping. The contact pressure and area increase with larger objects and smaller hands [25]. Glove fabrics strongly affect hand pressure, which increases by 24% when spandex content rises from 8% to 15% [5]. Therefore, contributions to glove construction can be made by evaluating the contact pressure or area to the hand with the FEM after collecting accurate hand dimensions and stress–strain ratio. The material and pattern-making can be revised for a desirable fit and wear comfort.

The precision of the FEM model relates primarily to the element number. Table 5 shows the relationship between the element number and precision in relative errors. The lowest average relative error of 7.87% is also recorded as the greatest element number used (1,262,481) [27], implying a positive relationship between the element numbers and precision. Although research [26] mentioned that a longer computation cost and time are required for greater element numbers, the optimum value of the parameters is not discussed to balance with the accuracy.

In terms of image-based approaches, 3D scanning offers great convenience with precision in collecting the outer surfaces of the target, yet excludes the internal soft tissue and muscle, limiting accuracy and authenticity compared to CT or magnetic resonance (MR) scans [27,28,29]. Only one study [4] includes 3D scanning for the FEM, with RMSE between 0.47 and 1.99 kPa. Considering that the FEM directly depends on the hand data input, further discussion between image-based approaches, especially 3D scanning, and accuracy should be conducted.

FEM models define the strain characteristics of the target material. Over 61% of the studies reviewed applied Abaqus for evaluating contact data, while 8% applied ANSYS and LS-DYNA for RA diagnosis and muscle vibration, respectively. No clear correlations are discovered in terms of precision among the three software, due to different purposes. Among Abaqus, linear and minor deformations, a linear elastic model involving the two parameters of Young’s modulus (strain ratio to stress, GPa/MPa/kPa) and Poisson’s ratio (deformation ratio in axial or lateral directions, P) is used [23,28,30]. A high Young’s modulus (15 GPa~18 GPa) and low Poisson’s ratio (0.2~0.3 P) are used for stiff bones, while the opposite is true for soft, incompressible skin (177 kPa~16.7 MPa, 0.3~0.4 P) [4,30,31]. Ogden hyper-elastic coefficients are used to evaluate the non-linear deformation and contact data of hand tissues [32,33,34]. Yet, there is no major correction found between the accuracy and model type, according to the results.

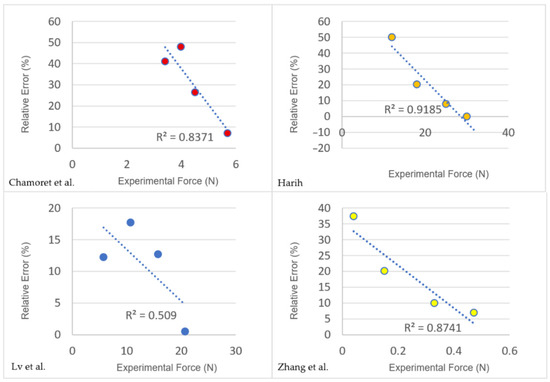

Figure 5 also presents the relationship between experimental force and precision. Harih [33] stated that the force increases from 12 to 30 N, while the relative error decreases significantly from 50% to 0%. Lv et al. [30] also mentioned that the lowest value of 0.48% is recorded after reaching the maximum force of 20.7 N. The coefficient of determination (R2) of the three studies [5,30,33] is above 0.83 (0.78 on average), which supports that the increasing force within the range is generally associated with a reduction in error for the FEM. Although Charomet’s study [31] presents a similar curve to the three, a lower R2 and higher error are observed. A possible reason could be the lower number of elements used. However, the time effect on muscle change is not well-developed, since the majority of the studies only cover the motion of grasping in a short period (<15 s), without analyzing the force variance and loss after the muscle activation [5,25,32,34]. Since the force may decrease after a certain period of time due to muscle fatigue, the force levels simulated can be distinctive during and after muscle activation.

Table 4.

Summary of papers reviewed (including FEM applications for hand simulation).

Table 4.

Summary of papers reviewed (including FEM applications for hand simulation).

| Type of Image-Based Approach | FEM Reconstructions on Hand | Material Parameters (Young’s Modulus, Poisson Ratio (P)/Ogden Hyper-Elastic Model (µ and α)) | Sample Sizes | Paper Focus/ Topic | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 3D imaging, 3D laser scanner (NextEngineInc.) | Four-node linear tetrahedron (>2.3 mm), static | Bone: 17 GPa, 0.3 P Skin: 177 kPa, 0.4 P | One female, age 25, fingers splayed, bare hand | Simulate the glove-skin interface pressure of therapy gloves | [4] |

| Open-source 3D anatomical digital hand model | Four-node linear tetrahedron (2 mm for bones, 1 mm for soft tissues), static | Bone: 14–20 GPa, 0.3 P Soft Tissues: 177 kPa, 0.4 P | 5 male subjects, age 21–24, no hand injuries, fingers splayed, cylindrical grasping gloved hand | Simulate the contact data of gloved hands grasping cylindrical objects | [5] |

| 2D CT imaging, then 3D modeling with Geomagic Studio | Linear tetrahedron (1 mm for bones, 0.5 mm for cartilage, 3 mm for soft tissues), static | Cortical and Canellous Bones: 18,000 and 100 MPa, 0.20/0.25 P RA Cortical and Canellous Bones: 12,000 and 33 MPa, 0.20/0.25 P Soft Tissue: 177 kPa, 0.4 P | One male with no hand injuries, fingers splayed. One male with rheumatoid arthritis, fingers splayed, bare hand/hand with orthosis | Compare the stress and displacement of the normal hand, the hand with RA, and the hand with RA and orthosis | [27] |

| 2D CT imaging, then 3D modeling with Scan2Mesh | Eight-node brick elements (7 mm for bones); four-node shell elements (2 mm for skin and flesh), dynamic | Bone: 15,000 MPa, 0.2 P Flesh: 0.5 MPa, 0.3 P Skin: 16.7 MPa, 0.4 P | One adult subject, no limits on age or gender, no hand injuries, cylindrical grasping, bare hand | Simulate the contact pressure of bare hands grasping cylindrical objects | [31] |

| 2D CT images, then 3D models by Geomagic Studio | Four-node linear tetrahedron for the entire hand, quasi-static | Bone: 17 GPa, 0.3 P Nail: 170 MPa, 0.3 P Soft Tissues: −0.0759–0.0657µ, 4.712–4.941α, 0.45 P | One subject, no limits on age or gender, fingers splayed and grasping, bare hand | Simulate the hand reactions (tissue strain, pressure, vibration) in actions like grasping | [33] |

| 3D model from human model database | Four-node solid tetrahedron elements (5 mm for bones and skin); three-node triangular shell elements (5 mm for soft tissue), dynamic | Bone: Rigid Skin: 80 kPa, 0.48 P Soft tissues: (−)9.32/(−)15.7µ, −1.21/9.34α, 0.48 P | 54 males, age 30–51, calculated and represented as 3 hand dimensions, cylindrical grasping, bare hand | Simulate the contact pressure, tactile comfort of bare hands grasping cylindrical objects | [32] |

| 3D model from human model database | Tetrahedron solid elements for bones and soft tissue; triangular shell elements for skin, quasi-static | Bone: 17 GPa, 0.3 P Skin: 0.014 GPa, 0.3 P Soft tissues: 0.014 GPa, 0.3 P | One subject, no limits on age or gender, cylindrical grasping, bare hand | Simulate the contact pressure, tactile comfort of bare hands grasping cylindrical objects | [25] |

| Open-source MR images, then 3D model by open-source software | Hexahedron elements for ligaments, tendon, tissue, and nerve; tetrahedral elements for bone, static | Bone: 10,000 MPa, 0.3 P Soft tissues: 24.9/37.6/12.5/12.9µ, 10.9/8.89/4.51/6.5α | One subject, no limits on age or gender, fingers splayed, bare hand | Diagnose carpal tunnel syndrome of the hand by analyzing the relationships between compression of the median nerve and finger flexion | [28] |

| 2D CT/MR images, then 3D models by Creo | Four-node solid tetrahedron elements for the entire hand, quasi-static | Bone: 17 GPa, 0.3 P Skin: −0.0759–0.0657µ, 4.941–6.425α Soft tissues: −0.0489–0.0396µ, 5.262–6.751α | One male, aged 23, fingers splayed, grasping, gloved hand | Define and simulate loading and boundary conditions, and predict contact pressure under different contact patterns | [24] |

| 3D image, 3D scanner (Artec 3D); Bone data from CT | Ten-node quadratic tetrahedron solid elements (5 mm for bone, fat, and skin), static | Bone: 15 GPa, 0.3 P Fat: 0.034 MPa, 0.45 P Skin: 0.177 MPa, 0.4 P | One male, no limits on age, slightly grasping hand with orthosis | Simulate the level and distribution of pressure perceived by the hand under orthosis | [26] |

| Open-source 3D hand model | Four-node linear tetrahedron solid elements (2 mm for bone, 1 mm for soft tissue), dynamic | Bone: 15 GPa, 0.3 P Soft tissues: −0.0489–0.0396µ, 5.262–6.751α | One male, cylindrical grasping, sphere grasping, three-finger pinching, bare hand | Simulate the contact pressure in grasping for designing exoskeleton gloves | [34] |

| 2D MR images, then 3D models by LS-Dyna | Tetrahedron elements (1 mm for isotropic/anisotropic muscle), dynamic | Isotropic muscle: 22.4 kPa (not activated), 338.8 kPa (MAX), 0.499 P Anisotropic muscle: 338.8 kPa, 0.499 P (longitudinal), 25.2 kPa, 0.963 P (transversal) | One male, aged 28, cylindrical grasping and pushing, bare hand | Analyze the vibratory behavior of hand muscles in cylindrical grasping and pushing actions | [29] |

| 2D CT images, then 3D models by MIMICS 19.0; muscle-tendon displacements measured by ultrasound imaging | Four-node linear tetrahedron elements (for bone, tendon, and ligament), dynamic | Bone: 17,000 MPa, 0.3 P Tendon: 68–125.31 MPa, 0.45 P Ligament: 20–114.03 MPa, 0.45 P | One male, aged 30, no hand injuries, fingers lifting with different forces and fingers splayed | Analyze the force applied in different muscles and their roles during fine hand movements | [30] |

Table 5.

The precision of FEM application among studies with the model and image-based approach used.

Table 5.

The precision of FEM application among studies with the model and image-based approach used.

| Model Used | Motion State | Element Size (mm) | Element Numbers | Relative Error (%) | Image-Based Approach | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Linear | Dynamic | 2 | 50,400 | 24.95 | 2D CT images | [31] |

| Linear | Dynamic | - | 326,427 | 10.82 | 2D CT with ultrasonic | [30] |

| Hyper-elastic | Quasi-static | - | 375,514 | 10.85 | Open-source 3D model | [33] |

| Linear | Static | 0.5, 1, 3 | 1,262,481 | 7.87 | 2D CT images | [27] |

Figure 5.

The relationship between the increasing force and the relative error among the studies [5,30,31,33].

4. Limitations and Future Directions

4.1. Limitations of 3D Scanning and FEM

After reviewing the articles and research in the literature, it was found that both hand anthropometric measurements obtained by scanning and simulation of the hand by using the FEM have their limitations. The limitations are due to the different standards of data collection or simulation, convenience with accessibility, and data retrieval.

4.1.1. Standards of Data Collection Simulation

A significant issue with the standardization of 3D scanning is the location of anatomical landmarks. The number and placement of landmarks can vary depending on the study. For instance, the hand landmarks for measuring the hand length vary from two to four [1,9,12]. Since landmarks are typically marked manually, their positions may differ between operators or be affected by slight hand movements and skin deformation of the subjects. This issue may escalate in older subjects above 40 due to skin aging, yet numerous articles only include younger age groups under 40. The comparison of landmark distribution and the accuracy of hand scanning between the two age groups is neglected. There is currently no standardized method for fixing landmark locations, and this issue is rarely addressed in the literature. As a result, variability in landmark placement can reduce the accuracy and robustness of 3D scanning measurements.

While Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ratio in the FEM are typically used for modeling linear elastic materials, such as the skin and bones, the Ogden model is used to analyze the soft tissues of the hand, due to its ability to capture both stiffness and non-linearity [24,28,32,34]. Higher Ogden values indicate higher stiffness and increased sensitivity to non-linear strain under pressure. However, some studies still apply linear models to soft tissues [25,27]. The lack of standardized guidelines and limited comparative research makes selecting the most appropriate material model for soft tissues challenging. Yet, no clear variance is presented in precision between the two models. The insufficient sample size of articles can be one challenge. Therefore, further studies need to focus on this issue to elaborate on the differences.

4.1.2. Convenience with Accessibility

CT and MR imaging are commonly used in the FEM to collect cross-sectional views of the hand but have notable limitations beyond safety concerns. Expensive, complex equipment and infrastructure are required, thus restricting their use to specialized environments such as hospitals [35], resulting in lower accessibility for small companies or research groups. Portable CT and MR imaging technologies are currently less accurate and still under development [36,37]. While higher accuracy is found in 3D scanners with greater resolution, it is accompanied by an increasing cost. Considering that the studies reviewed involve diverse scanners, software, and measurement areas, the relationship between the scanners and precision, in unified settings, should be discussed. While the balance between cost, scanning properties, and resources for training of 3D scanners needs to be focused on.

Both 3D scanning and FEM require mesh refining and flattening for proper and accurate measurements. However, a high computational cost and time are needed for simulating the curvatures and skin deformation by using the FEM and meshing, with mesh size affecting accuracy [22,27]. No optimum value can be found to balance the mesh, or element attributes required, and effectiveness. The same issue is found in 3D scanning with dependencies on software. The correlations between training resources, accuracy, and convenience are not identified. This may affect the research time and accessibility, due to the variances in applications and operations in numerous software and scanners.

4.1.3. Data Retrieval

Three-dimensional scanning effectively captures the external shape and silhouette of the hand but does not provide information about the muscles and bones that lie underneath the skin. However, stiffness and strain ratios differ among bone, dermis, and subcutaneous tissues of the hand, which means that there are different reactions during contact or under pressure. Hence, 3D scanning is less accurate than advanced techniques like CT or MR imaging, which can capture detailed musculoskeletal data. However, CT and MR imaging both require longer acquisition times and incur higher computational costs, so they are unsuitable for large sample sizes compared to 3D scanning [35,38]. There is currently no single method offering both a high-precision surface and internal hand structure data with convenience and accessibility. The subject-specific feature of the FEM also causes challenges in the generalizability of glove sizing. This limitation restricts the application of the FEM in glove design, as models are often based on data from only a single or a few subjects (85% of studies reviewed only cover one subject), resulting in reduced versatility among different hand sizes.

4.2. Future Directions

Challenges remain in using scanning and FEM technologies for glove construction, particularly regarding fit and customization. The following four future research directions are recommended: enhancing image collection through 3D scanning, standardizing or comparing data retrieval, extending the FEM to different areas, and integrating artificial intelligence (AI) for machine learning (ML).

4.2.1. Enhanced Image Collection Through 3D Scanning

Enhancing 3D scanning to capture the subcutaneous tissue and bone dimensions, or integrating it with CT and MR imaging, could enable the simultaneous acquisition of both external and internal hand structures in a single scan. This approach would improve efficiency and accessibility by reducing the acquisition time and costs and allowing for data collection from a larger area of the hand. The number of subjects of the FEM may also be increased, as more subjects can be included due to the shortened acquisition time of the hand measurements. Advanced scanning would also facilitate analysis of the hand’s dimensional changes in the skin and muscles, thus revealing the relationships between the skin and tissue strain ratio under various gestures and motions. With comprehensive measurements of the hand under static and dynamic conditions, the sizing and patterning of gloves can be modeled more accurately, thus ensuring a contoured fit and higher wear comfort during movement.

4.2.2. Standardization or Comparison of Data Retrieval

Standardizing data retrieval processes in both 3D scanning and the FEM is essential. Considering that the landmarks’ distribution and number present a high variance between studies [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38] and standards like ISO 7250 [21], defining and unifying the landmark parameters in the aspects of age group or study design should be the focus. Automatic landmark tracking and placement are suggested instead of manual methods, which can reduce human errors and variability, especially when using a larger number of landmarks or targeting specific locations like the finger webs [12], which is not well-addressed in the current literature. Additionally, comparing linear elastic and hyper-elastic Abaqus FEM material models in terms of precision and computational efficiency, in addition to other FEM models of LS-DYNA and ANSYS on hand simulation, will help to identify the most accurate and cost-effective approach for representing the hand. Simplifying the material definition and methods will also improve accessibility and ease of use. With unified landmark locations and material models, data collection can be standardized and reused across multiple subjects, enabling consistent evaluations and comparisons. This standardization supports scalable and efficient glove production, based on reliable hand data.

4.2.3. Extension of FEM to Different Areas

Hand movements in finite element modeling, like grasping and pinching with bare hands, are often featured, while scenarios that involve gloved hands are less explored. Since hand strain and contact areas can differ significantly when wearing gloves, real-time data on pressure and contact during dynamic movement should be collected for enhanced accuracy. This is particularly important in fields such as rehabilitation, sports, and the glove industry, where evaluating the support or protection provided by gloves is essential. The design can be refined and manufactured through FEM simulations at the prototyping stage and subjective wear trials can offer additional insights for further improvement.

4.2.4. Possible Applications with AI and ML

Combining AI and 3D scanning or finite element modeling may overcome the challenge of mass production of gloves that can accommodate different individuals, due to varying hand dimensions. Algorithms with ML automate and accelerate landmark detection and distribution in 3D scanning by accommodating and testing material models in the FEM for a large data set. Further generating combinations of possible materials and glove patterns, based on the hand dimensions acquired statically and dynamically, is also possible for the glove design and manufacture, in which time can be optimized to reduce repetitive trial-and-error practices of manual analysis in the wear trials and material selection.

5. Conclusions

The review has summarized recent advancements in hand anthropometric measurements through 3D scanning and FEM simulation, and highlighted their applications, and the techniques, materials, or postures involved. Both techniques enable the reconstruction and simulation of the hand in static or dynamic states, thus allowing for the prediction and measurement of hand dimensions and strain ratios.

Higher precision of 3D scanning is performed with a greater resolution for the scanners, while the number and distribution of landmarks are allocated with the study’s purposes. The evaluation of the precision and resources required for training between the scanners with software is unclear, which should be focused on in future studies. Scanners with lower cost and high precision still require further development to provide wider accessibility and generalizability.

FEM simulation is based on the element number used to provide greater authenticity. The model and image-based approach used may not have significance in the accuracy, which requires further evaluations. While CT and MR imaging are widely adopted for acquiring internal anatomical structures, 3D scanning is more limited to surface data, yet insufficient research evaluates their impact on precision in comparison. A trend is also discovered: lower error is presented by increasing force within the test range.

Both techniques play crucial roles in glove design and construction. Future improvements could include enhancing scanning capability, standardizing data collection and analysis methods, expanding the FEM’s capabilities, and integrating AI. These advancements will increase accuracy and robustness, while maintaining accessibility, thus supporting the development of gloves with optimal fit, wear comfort, protection, and support. Standardized and advanced techniques will also streamline glove allowances, material selection, and pattern design, thus facilitating scalable and efficient glove manufacturing processes.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; methodology, C.-Y.C., S.-C.H., and M.-Y.K.; software, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; validation, C.-Y.C., S.-C.H. and M.-Y.K.; formal analysis, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; investigation, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; resources, K.-L.Y.; data curation, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; writing—original draft preparation, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; writing—review and editing, C.-Y.C., S.-C.H., M.-Y.K. and K.-L.Y.; visualization, C.-Y.C. and S.-C.H.; supervision, K.-L.Y.; project administration, K.-L.Y.; funding acquisition, K.-L.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Research Institute for Sports Science and Technology, PolyU Academy for Interdisciplinary Research of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, grant number 1-CD3A.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge financial support from the Research Institute for Sports Science and Technology (RISports), PolyU Academy for Interdisciplinary Research (PAIR) of The Hong Kong Polytechnic University (project account 1-CD3A).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| FEM | Finite element method |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| MR | Magnetic resonance |

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| ML | Machine learning |

| WoS | Web of Science |

| ICC | Intraclass correlation coefficient |

| RA | Rheumatoid arthritis |

| FDP | Flexor digitorum profundus |

| FDS | Flexor digitorum superficialis |

References

- Griffin, L.; Sokolowski, S.L.; Savvateev, E.; Bhuyan, A.U.I.A. Comparison of Glove Specifications, 3D Hand Scans, and Sizing of Sports Gloves for Athletes. In Proceedings of the 3DBODY.TECH 2019—10th International Conference and Exhibition on 3D Body Scanning and Processing Technologies, Lugano, Switzerland, 22–23 October 2019; pp. 109–118. [Google Scholar]

- Kovacs, K.; Splittstoesser, R.; Maronitis, A.; Marras, W.S. Grip Force and Muscle Activity Differences Due to Glove Type. AIHA J. 2002, 63, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.; Yick, K.L.; Ng, S.P.; Yip, J. 2D and 3D anatomical analyses of hand dimensions for custom-made gloves. Appl. Ergon. 2013, 44, 381–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, A.; Yick, K.L.; Ng, S.P.; Yip, J.; Chan, Y.F. Numerical simulation of pressure therapy glove by using Finite Element Method. Burns 2016, 42, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, H.; Lake, M.J. Accuracy prediction of wearable flexible smart gloves. AUTEX Res. J. 2024, 24, 20230008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, S.H.; Troynikov, O.; Watson, C. Skin Deformation Behavior during Hand Movements and Their Impact on Functional Sports Glove Design. Procedia Eng. 2015, 112, 92–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szkudlarek, J.; Zagrodny, B.; Zarychta, S.; Zhao, X. 3D Hand Scanning Methodology for Determining Protective Glove Dimensional Allowances. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zeng, L.; Pan, D.; Sui, X.; Tang, J. Evaluating the Accuracy of Hand Models Obtained from Two 3D Scanning Techniques. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 11875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Filho, P.C.A.; da Silva, L.; Castellucci, H.I.; Rodrigues, M.; Pereira, E.; Pombeiro, A.; Colim, A.; Carneiro, P.; Arezes, P.; Guedes, J.C.; et al. Comparison Between Anthropometric Equipment and Scanners in Hand Measurement. In Occupational and Environmental Safety and Health V; Arezes, P.M., Melo, R.B., Carneiro, P., Castelo Branco, J., Colim, A., Costa, N., Costa, S., Duarte, J., Guedes, J.C., Perestrelo, G., et al., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; Volume 492, pp. 43–58. [Google Scholar]

- Paoli, A.; Neri, P.; Razionale, A.V.; Tamburrino, F.; Barone, S. Sensor Architectures and Technologies for Upper Limb 3D Surface Reconstruction: A Review. Sensors 2020, 20, 6584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, Y.; Wu, S.; Hu, Q.; Zhou, W.; Shen, Y.; Yan, X.; Ma, Y. Influence of Grasping Postures on Skin Deformation of Hand. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 21416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwan, M.; Yick, K.; Chow, L.; Yu, A.; Ng, S.; Yip, J. Impact of Postural Variation on Hand Measurements: Three-Dimensional Anatomical Analysis. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0250428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffin, L.; Kim, N.; Carufel, R.; Sokolowski, S.; Lee, H.; Seifert, E. Dimensions of the Dynamic Hand: Implications for Glove Design, Fit, and Sizing. In Advances in Interdisciplinary Practice in Industrial Design, 2nd ed.; Shin, C.S., Ed.; Springer International Publishing AG: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 790, pp. 38–48. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Chen, H.; Ouyang, Y.; Cao, C.; Gao, W.; Hu, Q.; Jin, H.; Zhang, S. A High-Resolution and Whole-Body Dataset of Hand-Object Contact Areas Based on 3D Scanning Method. Sci. Data 2025, 12, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanseverino, G.; Schwanitz, S.; Krumm, D.; Odenwald, S.; Lanzotti, A. Understanding the Effect of Gloves on Hand-Arm Vibrations in Road Cycling. Proceedings 2020, 49, 70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zare Bidoki, F.; Ezazshahabi, N.; Mousazadegan, F.; Latifi, M. Objective and Subjective Evaluation of Various Aspects of Hand Performance Considering Protective Glove’s Constructional Parameters. J. Ind. Text. 2022, 51 (Suppl. S4), 6533S–6562S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifert, E.; Griffin, L. Comparison and Validation of Traditional and 3D Scanning Anthropometric Methods to Measure the Hand. In Proceedings of the 11th Int. Conference and Exhibition on 3D Body Scanning and Processing Technologies, Lugano, Switzerland, 17–18 November 2020; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Bhuyan, A.U.I.; Griffin, L. Make It Easy: Reliability of Automatic Measurement for 3D Hand Scanning. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference and Exhibition on 3D Body Scanning and Processing Technologies, Lugano, Switzerland, 17–18 November 2020; p. 38. [Google Scholar]

- Glazer, C.; Oravitan, M.; Pantea, C.; Almajan-Guta, B.; Jurjiu, N.-A.; Marghitas, M.P.; Avram, C.; Stanila, A.M. Evaluating 3D Hand Scanning Accuracy Across Trained and Untrained Students. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Q.; Wang, H.; Liu, K. Anthropometric Hand Dimensions of Chinese Adults Using Three-Dimensional Scanning Technique. In Design, User Experience, and Usability: Design for Emotion, Well-Being and Health, Learning, and Culture; Soares, M.M., Marcus, A., Rosenzweig, E., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 13322, pp. 377–387. [Google Scholar]

- ISO 7250; Basic Human Body Measurements for Technological Design. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Mena, A.; Wollstein, R.; Baus, J.; Yang, J. Finite Element Modeling of the Human Wrist: A Review. J. Wrist Surg. 2023, 12, 478–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cei, G.; Artoni, A.; Bianchi, M. A Review on Finite Element Modelling of Finger and Hand Mechanical Behaviour in Haptic Interactions. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 2025, 24, 895–917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Zou, Z.; Wei, G.; Ren, L.; Qian, Z. Subject-Specific Finite Element Modelling of the Human Hand Complex: Muscle-Driven Simulations and Experimental Validation. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2020, 48, 1181–1195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokari, K.; Arimoto, R.; Pramudita, J.A.; Ito, M.; Noda, S.; Tanabe, Y. Palmar Contact Pressure Distribution During Grasping a Cylindrical Object: Parameter Study Using Hand Finite Element Model. Adv. Exp. Mech. 2019, 4, 135–140. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, X.; Ahmed-Kristensen, S.; Zhu, Q.; Han, T.; Zhu, L.; Chen, W.; Cao, J.; Nanayakkara, T. Identification of Excessive Contact Pressures under Hand Orthosis Based on Finite Element Analysis. Prosthet. Orthot. Int. 2025, 49, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Yang, J.; Feng, P.; Li, X.; Chen, W. Biomechanical Analysis of Rheumatoid Arthritis of the Hand and the Design of Orthotics: A Finite Element Study. Bioengineering 2025, 12, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peshin, S.; Karakulova, Y.; Kuchumov, A.G. Finite Element Modeling of the Fingers and Wrist Flexion/Extension Effect on Median Nerve Compression. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 1219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vauthier, S.; Noël, C.; Settembre, N.; Ngo, N.H.P.; Gennisson, J.; Chambert, J.; Foltête, E.; Jacquet, E. Factoring Muscle Activation and Anisotropy in Modelling Hand-Transmitted Vibrations: A Preliminary Study. Proceedings 2023, 86, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, Y.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, X.; Hou, C.; An, M. Analysis on Synergistic Cocontraction of Extrinsic Finger Flexors and Extensors during Flexion Movements: A Finite Element Digital Human Hand Model. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0268137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamoret, D.; Bodo, M.; Roth, S. A First Step in Finite-Element Simulation of a Grasping Task. Comput. Assist. Surg. 2016, 21 (Suppl. S1), 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hokari, K.; Pramudita, J.A.; Okada, K.; Ito, M.; Tanabe, Y. Development of a Gripping Comfort Evaluation Method Based on Numerical Simulations Using Individual Hand Finite Element Models. Int. J. Hum. Factors Ergon. 2023, 10, 187–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harih, G. Development of a Tendon Driven Finger Joint Model Using Finite Element Method. In Advances in Human Factors in Simulation and Modeling; Cassenti, D.N., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 780, pp. 463–471. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, H.; Newton, M.A.A. Enhancing Assistive Technology Design: Biomechanical Finite Element Modeling for Grasping Strategy Optimization in Exoskeleton Data Gloves. Med. Eng. Phys. 2025, 137, 104308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reyes-Santias, F.; Antelo, M. Explaining the Adoption and Use of Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Image Technologies in Public Hospitals. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2021, 21, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wald, L.L.; McDaniel, P.C.; Witzel, T.; Stockmann, J.P.; Cooley, C.Z. Low-Cost and Portable MRI. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging 2020, 52, 686–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersson, H.; Tamaddon, A.; Malekian, M.; Ydström, K.; Siemund, R.; Ullberg, T.; Wasselius, J. Comparison of Image Quality between a Novel Mobile CT Scanner and Current Generation Stationary CT Scanners. Neuroradiology 2023, 65, 503–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckel, R.; Jacob, M.; Chaudhari, A.; Perlman, O.; Shimron, E. Deep Learning for Accelerated and Robust MRI Reconstruction. Magn. Reson. Mater. Phy. 2024, 37, 335–368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).