Mechanisms and Functions of Chromophore Regeneration in the Classical Visual Cycle: Implications for Retinal Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy

Abstract

1. Literature Search Strategy

2. Introduction

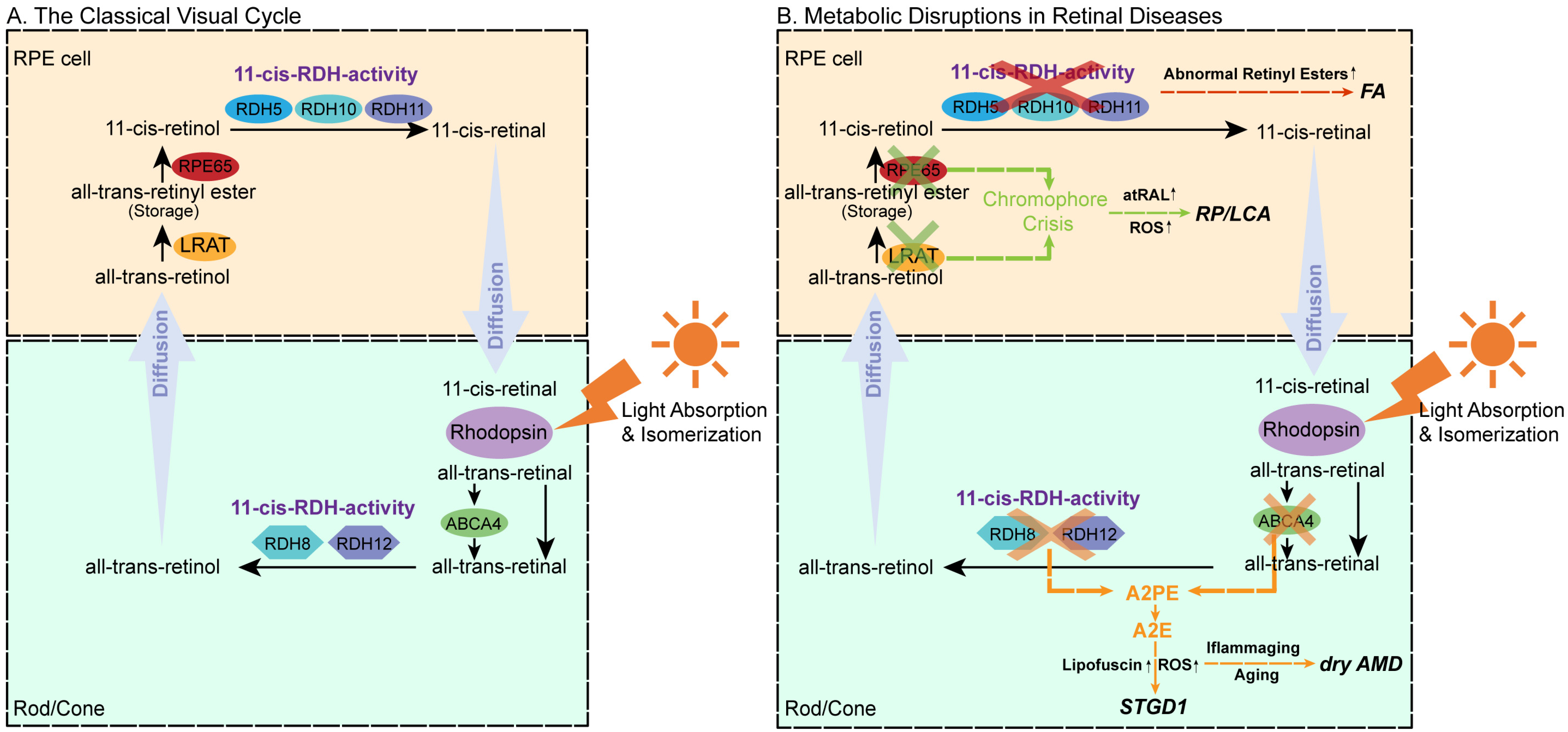

3. Molecular Mechanisms of the Visual Cycle

3.1. Precycle Events

3.2. Core Metabolic Phase

3.2.1. Esterification

3.2.2. Isomerization–Hydrolysis

3.2.3. Oxidation

3.2.4. Trafficking and Delivery

3.3. Protective and Regulatory Mechanisms

3.3.1. Photon Capture and Signal Amplification

3.3.2. Antioxidant Defense

3.3.3. Metabolic Feedback Regulation

4. Chromophore Metabolic Abnormalities and Retinal Diseases

4.1. Stargardt Disease Type 1 (STGD1)

4.1.1. ABCA4 and RDH8 Synergistic Pathogenic Mechanisms

4.1.2. Pharmacological and Gene-Based Therapeutic Strategies for STGD1

4.2. Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD)

4.2.1. Visual Cycle Inefficiency and Retinoid Toxicity

4.2.2. Pharmacological and Biophysical Therapeutic Strategies for Dry AMD

4.3. Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP) and Leber Congenital Amaurosis (LCA)

4.3.1. LRAT and RPE65 Synergistic Pathogenic Mechanisms

4.3.2. Gene-Based and Pharmacological Therapeutic Advances for RP and LCA

4.4. Fundus Albipunctatus (FA)

4.4.1. RDH5 and RLBP1 Synergistic Pathogenic Mechanisms

4.4.2. Gene, Metabolic, and Cellular Therapeutic Strategies for FA

5. Therapeutic Limitations and Real-World Barriers in Visual-Cycle

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Abbreviation | Full Term |

| A2E | N-retinylidene-N-retinylethanolamine |

| A2PE | N-retinylidene-N-retinyl-phosphatidylethanolamine |

| atRAL | All-trans-retinal |

| atROL | All-trans-retinol |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| 11cRAL | 11-cis-retinal |

| 11cROL | 11-cis-retinol |

| CRALBP | Cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein |

| CRBP | Cellular retinol-binding protein |

| ABCA4 | ATP-binding cassette transporter 4 |

| LRAT | Lecithin:retinol acyltransferase |

| RDH | Retinol dehydrogenase |

| RPE | Retinal pigment epithelium |

| RPE65 | Retinal pigment epithelium-specific 65 kDa protein |

| RP | Retinitis pigmentosa |

| STGD1 | Stargardt disease type 1 |

| LCA | Leber congenital amaurosis |

| FA | Fundus albipunctatus |

| PBM | photobiomodulation |

References

- Burton, M.J.; Ramke, J.; Marques, A.P.; Bourne, R.R.A.; Congdon, N.; Jones, I.; Ah Tong, B.A.M.; Arunga, S.; Bachani, D.; Bascaran, C.; et al. The Lancet Global Health Commission on Global Eye Health: Vision beyond 2020. Lancet Glob. Health 2021, 9, e489–e551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.S.; Kefalov, V.J. The cone-specific visual cycle. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2011, 30, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kefalov, V.J. The Retina-Based Visual Cycle. Annu. Rev. Vis. Sci. 2024, 10, 293–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakeley, L.R.; Chen, C.; Chen, C.K.; Chen, J.; Crouch, R.K.; Travis, G.H.; Koutalos, Y. Rod outer segment retinol formation is independent of Abca4, arrestin, rhodopsin kinase, and rhodopsin palmitylation. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2011, 52, 3483–3491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mizobuchi, K.; Hayashi, T.; Ueno, S.; Kondo, M.; Terasaki, H.; Aoki, T.; Nakano, T. One-Year Outcomes of Oral Treatment With Alga Capsules Containing Low Levels of 9-cis-β-Carotene in RDH5-Related Fundus Albipunctatus. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2023, 254, 193–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cremers, F.P.M.; Lee, W.; Collin, R.W.J.; Allikmets, R. Clinical spectrum, genetic complexity and therapeutic approaches for retinal disease caused by ABCA4 mutations. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2020, 79, 100861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Georgiou, M.; Robson, A.G.; Fujinami, K.; de Guimarães, T.A.C.; Fujinami-Yokokawa, Y.; Daich Varela, M.; Pontikos, N.; Kalitzeos, A.; Mahroo, O.A.; Webster, A.R.; et al. Phenotyping and genotyping inherited retinal diseases: Molecular genetics, clinical and imaging features, and therapeutics of macular dystrophies, cone and cone-rod dystrophies, rod-cone dystrophies, Leber congenital amaurosis, and cone dysfunction syndromes. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2024, 100, 101244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, G.; Liu, Z.; Xie, S.; Li, C.; Lv, L.; Zhang, M.; Zhao, J. Genetic and phenotypic characteristics of four Chinese families with fundus albipunctatus. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 46285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Fry, L.E.; Wang, J.H.; Martin, K.R.; Hewitt, A.W.; Chen, F.K.; Liu, G.S. RNA-targeting strategies as a platform for ocular gene therapy. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2023, 92, 101110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.H.; Zhan, W.; Gallagher, T.L.; Gao, G. Recombinant adeno-associated virus as a delivery platform for ocular gene therapy: A comprehensive review. Mol. Ther. J. Am. Soc. Gene Ther. 2024, 32, 4185–4207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Ma, X.; Muthuraman, P.; Raja, A.; Jayaraman, A.; Petrukhin, K.; Cioffi, C.L.; Ma, J.X.; Moiseyev, G. The novel visual cycle inhibitor (±)-RPE65-61 protects retinal photoreceptors from light-induced degeneration. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solano, Y.J.; Everett, M.P.; Dang, K.S.; Abueg, J.; Kiser, P.D. Carotenoid cleavage enzymes evolved convergently to generate the visual chromophore. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2024, 20, 779–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dai, X.; Jin, X.; Ye, Q.; Huang, H.; Duo, L.; Lu, C.; Bao, J.; Chen, H. Intraperitoneal chromophore injections delay early-onset and rapid retinal cone degeneration in a mouse model of Leber congenital amaurosis. Exp. Eye Res. 2021, 212, 108776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feathers, K.L.; Jia, L.; Khan, N.W.; Smith, A.J.; Ma, J.X.; Ali, R.R.; Thompson, D.A. Gene Supplementation in Mice Heterozygous for the D477G RPE65 Variant Implicated in Autosomal Dominant Retinitis Pigmentosa. Hum. Gene Ther. 2023, 34, 639–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.; Wang, J.S.; Kefalov, V.J.; Crouch, R.K. Interphotoreceptor retinoid-binding protein as the physiologically relevant carrier of 11-cis-retinol in the cone visual cycle. J. Neurosci. 2011, 31, 4714–4719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Choi, E.H.; Tworak, A.; Salom, D.; Leinonen, H.; Sander, C.L.; Hoang, T.V.; Handa, J.T.; Blackshaw, S.; Palczewska, G.; et al. Photic generation of 11-cis-retinal in bovine retinal pigment epithelium. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 19137–19154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaluski, J.; Bassetto, M.; Kiser, P.D.; Tochtrop, G.P. Advances and therapeutic opportunities in visual cycle modulation. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2025, 106, 101360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, Z.; Silverman, D.; Li, S.; Bina, P.; Yau, K.W. Dark continuous noise from visual pigment as a major mechanism underlying rod-cone difference in light sensitivity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2418031121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lórenz-Fonfría, V.A.; Furutani, Y.; Ota, T.; Ido, K.; Kandori, H. Protein fluctuations as the possible origin of the thermal activation of rod photoreceptors in the dark. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010, 132, 5693–5703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Thompson, D.A.; Koutalos, Y. Reduction of all-trans-retinal in vertebrate rod photoreceptors requires the combined action of RDH8 and RDH12. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 24662–24670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Golczak, M.; Maeda, T.; Palczewski, K. Limited roles of Rdh8, Rdh12, and Abca4 in all-trans-retinal clearance in mouse retina. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 5435–5443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maeda, A.; Maeda, T.; Sun, W.; Zhang, H.; Baehr, W.; Palczewski, K. Redundant and unique roles of retinol dehydrogenases in the mouse retina. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19565–19570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lenis, T.L.; Hu, J.; Ng, S.Y.; Jiang, Z.; Sarfare, S.; Lloyd, M.B.; Esposito, N.J.; Samuel, W.; Jaworski, C.; Bok, D.; et al. Expression of ABCA4 in the retinal pigment epithelium and its implications for Stargardt macular degeneration. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2018, 115, E11120–E11127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, H.; Toms, M.; Moosajee, M. Involvement of Oxidative and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress in RDH12-Related Retinopathies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 8863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaylor, J.J.; Cook, J.D.; Makshanoff, J.; Bischoff, N.; Yong, J.; Travis, G.H. Identification of the 11-cis-specific retinyl-ester synthase in retinal Müller cells as multifunctional O-acyltransferase (MFAT). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 7302–7307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tu, D.C.; Owens, L.A.; Anderson, L.; Golczak, M.; Doyle, S.E.; McCall, M.; Menaker, M.; Palczewski, K.; Van Gelder, R.N. Inner retinal photoreception independent of the visual retinoid cycle. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2006, 103, 10426–10431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, P.D. Retinal pigment epithelium 65 kDa protein (RPE65): An update. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 88, 101013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cachafeiro, M.; Bemelmans, A.P.; Canola, K.; Pignat, V.; Crippa, S.V.; Kostic, C.; Arsenijevic, Y. Remaining rod activity mediates visual behavior in adult Rpe65−/− mice. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2010, 51, 6835–6842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Sun, W.; Perusek, L.; Parmar, V.; Le, Y.Z.; Griswold, M.D.; Palczewski, K.; Maeda, A. Conditional Ablation of Retinol Dehydrogenase 10 in the Retinal Pigmented Epithelium Causes Delayed Dark Adaption in Mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 27239–27247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, R.O.; Crouch, R.K. Retinol dehydrogenases (RDHs) in the visual cycle. Exp. Eye Res. 2010, 91, 788–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, S.; Kefalov, V.J. cis Retinol oxidation regulates photoreceptor access to the retina visual cycle and cone pigment regeneration. J. Physiol. 2016, 594, 6753–6765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köhn, L.; Burstedt, M.S.; Jonsson, F.; Kadzhaev, K.; Haamer, E.; Sandgren, O.; Golovleva, I. Carrier of R14W in carbonic anhydrase IV presents Bothnia dystrophy phenotype caused by two allelic mutations in RLBP1. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2008, 49, 3172–3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozawa, Y. Oxidative stress in the light-exposed retina and its implication in age-related macular degeneration. Redox Biol. 2020, 37, 101779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Daruwalla, A.; Choi, E.H.; Palczewski, K.; Kiser, P.D. Structural biology of 11-cis-retinaldehyde production in the classical visual cycle. Biochem. J. 2018, 475, 3171–3188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Yang, K.; He, D.; Yang, B.; Tao, L.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Induction of ferroptosis by HO-1 contributes to retinal degeneration in mice with defective clearance of all-trans-retinal. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2023, 194, 245–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, R.; Sundaramurthi, H.; Di Giacomo, V.; Kennedy, B.N. Enhancing Understanding of the Visual Cycle by Applying CRISPR/Cas9 Gene Editing in Zebrafish. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2018, 6, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkumar, S.; Moon, J.; Golczak, M.; von Lintig, J. LRAT coordinates the negative-feedback regulation of intestinal retinoid biosynthesis from β-carotene. J. Lipid Res. 2021, 62, 100055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, K.; Xi, R.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Quercetin Alleviates All-Trans-Retinal-Induced Photoreceptor Apoptosis and Retinal Degeneration by Inhibiting the ER Stress-Related PERK Signaling. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 13624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; Tao, L.; Cai, B.; Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, S.; Liao, C.; Chen, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, Z.; et al. eIF2α incites photoreceptor cell and retina damage by all-trans-retinal. J. Biol. Chem. 2023, 299, 104686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdolrahimzadeh, S.; Formisano, M.; Di Pippo, M.; Lodesani, M.; Lotery, A.J. The Role of the Choroid in Stargardt Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 7607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Yang, K.; Chen, Y.; Li, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, S.; Wu, Y. Exposure of A2E to blue light promotes ferroptosis in the retinal pigment epithelium. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett. 2025, 30, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Feng, Y.; Han, P.; Wang, F.; Luo, X.; Liang, J.; Sun, X.; Ye, J.; Lu, Y.; Sun, X. Photosensitization of A2E triggers telomere dysfunction and accelerates retinal pigment epithelium senescence. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sajovic, J.; Meglič, A.; Glavač, D.; Markelj, Š.; Hawlina, M.; Fakin, A. The Role of Vitamin A in Retinal Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 1014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Cai, X.; Xia, Q.; Chen, J.; Liao, Y.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y. All-trans-retinal dimer formation alleviates the cytotoxicity of all-trans-retinal in human retinal pigment epithelial cells. Toxicology 2016, 371, 41–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molday, R.S.; Garces, F.A.; Scortecci, J.F.; Molday, L.L. Structure and function of ABCA4 and its role in the visual cycle and Stargardt macular degeneration. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2022, 89, 101036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyer, N.P.; Thompson, D.A.; Koutalos, Y. Relative Contributions of All-Trans and 11-Cis Retinal to Formation of Lipofuscin and A2E Accumulating in Mouse Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2021, 62, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Maeda, T.; Imanishi, Y.; Kuksa, V.; Alekseev, A.; Bronson, J.D.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, L.; Sun, W.; Saperstein, D.A.; et al. Role of photoreceptor-specific retinol dehydrogenase in the retinoid cycle in vivo. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 18822–18832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbel Issa, P.; Barnard, A.R.; Singh, M.S.; Carter, E.; Jiang, Z.; Radu, R.A.; Schraermeyer, U.; MacLaren, R.E. Fundus autofluorescence in the Abca4(−/−) mouse model of Stargardt disease--correlation with accumulation of A2E, retinal function, and histology. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2013, 54, 5602–5612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, B.; Liao, C.; He, D.; Chen, J.; Han, J.; Lu, J.; Qin, K.; Liang, W.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; et al. Gasdermin E mediates photoreceptor damage by all-trans-retinal in the mouse retina. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, T.; Parmar, V.M.; Arai, E.; Sahu, B.; Perusek, L.; Maeda, A. Acute Stress Responses Are Early Molecular Events of Retinal Degeneration in Abca4-/-Rdh8-/- Mice After Light Exposure. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2016, 57, 3257–3267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, Y.; Moiseyev, G.; Petrukhin, K.; Cioffi, C.L.; Muthuraman, P.; Takahashi, Y.; Ma, J.X. A novel RPE65 inhibitor CU239 suppresses visual cycle and prevents retinal degeneration. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Basis Dis. 2018, 1864, 2420–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kiser, P.D.; Badiee, M.; Palczewska, G.; Dong, Z.; Golczak, M.; Tochtrop, G.P.; Palczewski, K. Molecular pharmacodynamics of emixustat in protection against retinal degeneration. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 2781–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blum, E.; Zhang, J.; Zaluski, J.; Einstein, D.E.; Korshin, E.E.; Kubas, A.; Gruzman, A.; Tochtrop, G.P.; Kiser, P.D.; Palczewski, K. Rational Alteration of Pharmacokinetics of Chiral Fluorinated and Deuterated Derivatives of Emixustat for Retinal Therapy. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 8287–8302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandal, M.N.; Moiseyev, G.P.; Elliott, M.H.; Kasus-Jacobi, A.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Zheng, L.; Nikolaeva, O.; Floyd, R.A.; Ma, J.X.; et al. Alpha-phenyl-N-tert-butylnitrone (PBN) prevents light-induced degeneration of the retina by inhibiting RPE65 protein isomerohydrolase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2011, 286, 32491–32501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piotter, E.; McClements, M.E.; MacLaren, R.E. Therapy Approaches for Stargardt Disease. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghenciu, L.A.; Hațegan, O.A.; Stoicescu, E.R.; Iacob, R.; Șișu, A.M. Emerging Therapeutic Approaches and Genetic Insights in Stargardt Disease: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeitz, C.; Robson, A.G.; Audo, I. Congenital stationary night blindness: An analysis and update of genotype-phenotype correlations and pathogenic mechanisms. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2015, 45, 58–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, M.A.; Erker, L.R.; Audo, I.; Choi, D.; Mohand-Said, S.; Sestakauskas, K.; Benoit, P.; Appelqvist, T.; Krahmer, M.; Ségaut-Prévost, C.; et al. Three-Year Safety Results of SAR422459 (EIAV-ABCA4) Gene Therapy in Patients With ABCA4-Associated Stargardt Disease: An Open-Label Dose-Escalation Phase I/IIa Clinical Trial, Cohorts 1–5. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2022, 240, 285–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennington, K.L.; DeAngelis, M.M. Epidemiology of age-related macular degeneration (AMD): Associations with cardiovascular disease phenotypes and lipid factors. Eye Vis. 2016, 3, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.Y.; Cipi, J.; Ma, S.; Hafler, B.P.; Kanadia, R.N.; Brush, R.S.; Agbaga, M.P.; Punzo, C. Altered photoreceptor metabolism in mouse causes late stage age-related macular degeneration-like pathologies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 13094–13104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, C.; Cai, B.; Feng, Y.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhuang, J.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y. Activation of JNK signaling promotes all-trans-retinal-induced photoreceptor apoptosis in mice. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 6958–6971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farnoodian, M.; Bose, D.; Barone, F.; Nelson, L.M.; Boyle, M.; Jun, B.; Do, K.; Gordon, W.; Guerin, M.K.; Perera, R.; et al. Retina and RPE lipid profile changes linked with ABCA4 associated Stargardt’s maculopathy. Pharmacol. Ther. 2023, 249, 108482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Liao, Y.; Chen, J.; Dong, X.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wu, X.; Liu, Z.; Wu, Y. Aberrant Buildup of All-Trans-Retinal Dimer, a Nonpyridinium Bisretinoid Lipofuscin Fluorophore, Contributes to the Degeneration of the Retinal Pigment Epithelium. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2017, 58, 1063–1075. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marie, M.; Bigot, K.; Angebault, C.; Barrau, C.; Gondouin, P.; Pagan, D.; Fouquet, S.; Villette, T.; Sahel, J.A.; Lenaers, G.; et al. Light action spectrum on oxidative stress and mitochondrial damage in A2E-loaded retinal pigment epithelium cells. Cell Death Dis. 2018, 9, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, B.; Yang, K.; Xi, R.; Li, S.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Inhibition of JNK signaling attenuates photoreceptor ferroptosis caused by all-trans-retinal. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2025, 227, 179–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.Y.; Bin, X.; Xu, Y.; Chen, S.; Zhou, S.; Chen, S.; Cao, Y.; Qiu, K.; Ng, T.K. The Profile of Retinal Ganglion Cell Death and Cellular Senescence in Mice with Aging. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Zhao, N.; Wei, D.; Pu, N.; Hao, X.N.; Huang, J.M.; Peng, G.H.; Tao, Y. Ferroptosis in the ageing retina: A malevolent fire of diabetic retinopathy. Ageing Res. Rev. 2024, 93, 102142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, V.; Monteiro, E.; Brazhnikova, E.; Lesage, L.; Balducci, C.; Guibout, L.; Feraille, L.; Elena, P.P.; Sahel, J.A.; Veillet, S.; et al. Norbixin Protects Retinal Pigmented Epithelium Cells and Photoreceptors against A2E-Mediated Phototoxicity In Vitro and In Vivo. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0167793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, V.; Monteiro, E.; Fournié, M.; Brazhnikova, E.; Boumedine, T.; Vidal, C.; Balducci, C.; Guibout, L.; Latil, M.; Dilda, P.J.; et al. Systemic administration of the di-apocarotenoid norbixin (BIO201) is neuroprotective, preserves photoreceptor function and inhibits A2E and lipofuscin accumulation in animal models of age-related macular degeneration and Stargardt disease. Aging 2020, 12, 6151–6171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fontaine, V.; Balducci, C.; Dinan, L.; Monteiro, E.; Boumedine, T.; Fournié, M.; Nguyen, V.; Guibout, L.; Clatot, J.; Latil, M.; et al. Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Photo- and Neuro-Protective Properties of BIO203, a New Amide Conjugate of Norbixin, in Development for the Treatment of Age-Related Macular Degeneration (AMD). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 5296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Li, X.; Lu, X. Regulation of toll-like receptor signaling pathways in age-related eye disease: From mechanisms to targeted therapeutics. Inflammopharmacology 2025, 33, 5257–5271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallenga, C.E.; Parmeggiani, F.; Costagliola, C.; Sebastiani, A.; Gallenga, P.E. Inflammaging: Should this term be suitable for age related macular degeneration too? Inflamm. Res. 2014, 63, 105–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, C.; Klejborowska, G.; Lanthier, C.; Hassannia, B.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Augustyns, K. Beyond ferrostatin-1: A comprehensive review of ferroptosis inhibitors. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2023, 44, 902–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Chen, Y.; He, B.; Xi, R.; Chen, J.; Wu, Y. Ferrostatin-1, a ferroptosis inhibitor, mitigates all-trans-retinal-induced retinal pigment epithelium degeneration in mice. J. Transl. Med. 2025, 23, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burton, B.; Parodi, M.B.; Jürgens, I.; Zanlonghi, X.; Hornan, D.; Roider, J.; Lorenz, K.; Munk, M.R.; Croissant, C.L.; Tedford, S.E.; et al. LIGHTSITE II Randomized Multicenter Trial: Evaluation of Multiwavelength Photobiomodulation in Non-exudative Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 953–968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.Y.; Lee, H.K.; Chan, H.C.; Chan, C.M. Is Multiwavelength Photobiomodulation Effective and Safe for Age-Related Macular Degeneration? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2025, 14, 969–987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borrelli, E.; Coco, G.; Pellegrini, M.; Mura, M.; Ciarmatori, N.; Scorcia, V.; Carnevali, A.; Lucisano, A.; Borselli, M.; Rossi, C.; et al. Safety, Tolerability, and Short-Term Efficacy of Low-Level Light Therapy for Dry Age-Related Macular Degeneration. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2024, 13, 2855–2868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vingolo, E.M.; Mascolo, S.; Miccichè, F.; Manco, G. Retinitis Pigmentosa: From Pathomolecular Mechanisms to Therapeutic Strategies. Medicina 2024, 60, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.H.; Yang, C.M.; Yang, C.H.; Hou, Y.C.; Chen, T.C. Leber’s Congenital Amaurosis: Current Concepts of Genotype-Phenotype Correlations. Genes 2021, 12, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Maeda, T.; Imanishi, Y.; Golczak, M.; Moise, A.R.; Palczewski, K. Aberrant metabolites in mouse models of congenital blinding diseases: Formation and storage of retinyl esters. Biochemistry 2006, 45, 4210–4219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hara, M.; Wu, W.; Malechka, V.V.; Takahashi, Y.; Ma, J.X.; Moiseyev, G. PNPLA2 mobilizes retinyl esters from retinosomes and promotes the generation of 11-cis-retinal in the visual cycle. Cell Rep. 2023, 42, 112091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sears, A.E.; Palczewski, K. Lecithin:Retinol Acyltransferase: A Key Enzyme Involved in the Retinoid (visual) Cycle. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 3082–3091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Montaser, A.B.; Gao, F.; Peters, D.; Vainionpää, K.; Zhibin, N.; Skowronska-Krawczyk, D.; Figeys, D.; Palczewski, K.; Leinonen, H. Retinal Proteome Profiling of Inherited Retinal Degeneration Across Three Different Mouse Models Suggests Common Drug Targets in Retinitis Pigmentosa. Mol. Cell. Proteom. 2024, 23, 100855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morshedian, A.; Kaylor, J.J.; Ng, S.Y.; Tsan, A.; Frederiksen, R.; Xu, T.; Yuan, L.; Sampath, A.P.; Radu, R.A.; Fain, G.L.; et al. Light-Driven Regeneration of Cone Visual Pigments through a Mechanism Involving RGR Opsin in Müller Glial Cells. Neuron 2019, 102, 1172–1183.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batten, M.L.; Imanishi, Y.; Maeda, T.; Tu, D.C.; Moise, A.R.; Bronson, D.; Possin, D.; Van Gelder, R.N.; Baehr, W.; Palczewski, K. Lecithin-retinol acyltransferase is essential for accumulation of all-trans-retinyl esters in the eye and in the liver. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 10422–10432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perusek, L.; Maeda, T. Vitamin A derivatives as treatment options for retinal degenerative diseases. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2646–2666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chelstowska, S.; Widjaja-Adhi, M.A.; Silvaroli, J.A.; Golczak, M. Molecular Basis for Vitamin A Uptake and Storage in Vertebrates. Nutrients 2016, 8, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiser, P.D.; Golczak, M.; Maeda, A.; Palczewski, K. Key enzymes of the retinoid (visual) cycle in vertebrate retina. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2012, 1821, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolesnikov, A.V.; Tang, P.H.; Kefalov, V.J. Examining the Role of Cone-expressed RPE65 in Mouse Cone Function. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 14201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadal-Nicolás, F.M.; Kunze, V.P.; Ball, J.M.; Peng, B.T.; Krishnan, A.; Zhou, G.; Dong, L.; Li, W. True S-cones are concentrated in the ventral mouse retina and wired for color detection in the upper visual field. eLife 2020, 9, e56840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Sun, X.; Wang, S.K.; Collin, G.B.; Kefalov, V.J.; Cepko, C.L. Chromophore supply modulates cone function and survival in retinitis pigmentosa mouse models. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2217885120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Gordon, W.C.; Bazan, N.G.; Jin, M. Inverse correlation between fatty acid transport protein 4 and vision in Leber congenital amaurosis associated with RPE65 mutation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 32114–32123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aoun, M.; Passerini, I.; Chiurazzi, P.; Karali, M.; De Rienzo, I.; Sartor, G.; Murro, V.; Filimonova, N.; Seri, M.; Banfi, S. Inherited Retinal Diseases Due to RPE65 Variants: From Genetic Diagnostic Management to Therapy. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sallum, J.M.F.; Kaur, V.P.; Shaikh, J.; Banhazi, J.; Spera, C.; Aouadj, C.; Viriato, D.; Fischer, M.D. Epidemiology of Mutations in the 65-kDa Retinal Pigment Epithelium (RPE65) Gene-Mediated Inherited Retinal Dystrophies: A Systematic Literature Review. Adv. Ther. 2022, 39, 1179–1198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, W.; Lin, T.Y.; Chang, Y.C.; Isahwan-Ahmad Mulyadi Lai, H.; Lin, S.C.; Ma, C.; Yarmishyn, A.A.; Lin, S.C.; Chang, K.J.; Chou, Y.B.; et al. An Update on Gene Therapy for Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: Experience in Leber Congenital Amaurosis Clinical Trials. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 4534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, N.; Michaelides, M.; Smith, A.J.; Ali, R.R.; Bainbridge, J.W.B. Retinal gene therapy. Br. Med. Bull. 2018, 126, 13–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, S.; Bennett, J.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; McCague, S.; et al. Efficacy and safety of voretigene neparvovec (AAV2-hRPE65v2) in patients with RPE65-mediated inherited retinal dystrophy: A randomised, controlled, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 2017, 390, 849–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, A.M.; Russell, S.; Wellman, J.A.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.F.; Tillman, A.; Wittes, J.; Pappas, J.; Elci, O.; Marshall, K.A.; et al. Efficacy, Safety, and Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec-rzyl in RPE65 Mutation-Associated Inherited Retinal Dystrophy: Results of Phase 1 and 3 Trials. Ophthalmology 2019, 126, 1273–1285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maguire, A.M.; Russell, S.; Chung, D.C.; Yu, Z.F.; Tillman, A.; Drack, A.V.; Simonelli, F.; Leroy, B.P.; Reape, K.Z.; High, K.A.; et al. Durability of Voretigene Neparvovec for Biallelic RPE65-Mediated Inherited Retinal Disease: Phase 3 Results at 3 and 4 Years. Ophthalmology 2021, 128, 1460–1468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, R.M.; Gregori, N.Z.; Ciulla, T.A.; Lam, B.L. Pharmacotherapy of retinal disease with visual cycle modulators. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2018, 19, 471–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azhar Baig, H.M.; Ansar, M.; Iqbal, A.; Naeem, M.A.; Quinodoz, M.; Calzetti, G.; Iqbal, M.; Rivolta, C. Genetic Analysis of Consanguineous Pakistani Families with Congenital Stationary Night Blindness. Ophthalmic Res. 2022, 65, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahu, B.; Maeda, A. Retinol Dehydrogenases Regulate Vitamin A Metabolism for Visual Function. Nutrients 2016, 8, 746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajmal, M.; Khan, M.I.; Neveling, K.; Khan, Y.M.; Ali, S.H.; Ahmed, W.; Iqbal, M.S.; Azam, M.; den Hollander, A.I.; Collin, R.W.; et al. Novel mutations in RDH5 cause fundus albipunctatus in two consanguineous Pakistani families. Mol. Vis. 2012, 18, 1558–1571. [Google Scholar]

- Bianco, L.; Antropoli, A.; Benadji, A.; Condroyer, C.; Antonio, A.; Navarro, J.; Sahel, J.A.; Zeitz, C.; Audo, I. RDH5 and RLBP1-Associated Inherited Retinal Diseases: Refining the Spectrum of Stationary and Progressive Phenotypes. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2024, 267, 160–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Hu, P.; Napoli, J.L. Elements in the N-terminal signaling sequence that determine cytosolic topology of short-chain dehydrogenases/reductases. Studies with retinol dehydrogenase type 1 and cis-retinol/androgen dehydrogenase type 1. J. Biol. Chem. 2004, 279, 51482–51489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hofmann, L.; Tsybovsky, Y.; Alexander, N.S.; Babino, D.; Leung, N.Y.; Montell, C.; Banerjee, S.; von Lintig, J.; Palczewski, K. Structural Insights into the Drosophila melanogaster Retinol Dehydrogenase, a Member of the Short-Chain Dehydrogenase/Reductase Family. Biochemistry 2016, 55, 6545–6557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saari, J.C.; Crabb, J.W. Focus on molecules: Cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein (CRALBP). Exp. Eye Res. 2005, 81, 245–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, J.C. Vitamin A and Vision. Sub-Cell. Biochem. 2016, 81, 231–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjo, K.M.; Moiseyev, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Crouch, R.K.; Ma, J.X. The 11-cis-retinol dehydrogenase activity of RDH10 and its interaction with visual cycle proteins. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 5089–5097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Shen, S.Q.; Jui, J.; Rupp, A.C.; Byrne, L.C.; Hattar, S.; Flannery, J.G.; Corbo, J.C.; Kefalov, V.J. CRALBP supports the mammalian retinal visual cycle and cone vision. J. Clin. Investig. 2015, 125, 727–738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolze, C.S.; Helbling, R.E.; Owen, R.L.; Pearson, A.R.; Pompidor, G.; Dworkowski, F.; Fuchs, M.R.; Furrer, J.; Golczak, M.; Palczewski, K.; et al. Human cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein has secondary thermal 9-cis-retinal isomerase activity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, J.C.; Nawrot, M.; Stenkamp, R.E.; Teller, D.C.; Garwin, G.G. Release of 11-cis-retinal from cellular retinaldehyde-binding protein by acidic lipids. Mol. Vis. 2009, 15, 844–854. [Google Scholar]

- Travis, G.H.; Golczak, M.; Moise, A.R.; Palczewski, K. Diseases caused by defects in the visual cycle: Retinoids as potential therapeutic agents. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 2007, 47, 469–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saari, J.C.; Nawrot, M.; Kennedy, B.N.; Garwin, G.G.; Hurley, J.B.; Huang, J.; Possin, D.E.; Crabb, J.W. Visual cycle impairment in cellular retinaldehyde binding protein (CRALBP) knockout mice results in delayed dark adaptation. Neuron 2001, 29, 739–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Peng, X.; Liu, Z. CRISPR/Cas9 systems: Delivery technologies and biomedical applications. Asian J. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 18, 100854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, V.W.; Bigelow, C.E.; McGee, T.L.; Gujar, A.N.; Li, H.; Hanks, S.M.; Vrouvlianis, J.; Maker, M.; Leehy, B.; Zhang, Y.; et al. AAV-mediated RLBP1 gene therapy improves the rate of dark adaptation in Rlbp1 knockout mice. Mol. Ther. Methods Clin. Dev. 2015, 2, 15022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Golovleva, I.; Bhattacharya, S.; Wu, Z.; Shaw, N.; Yang, Y.; Andrabi, K.; West, K.A.; Burstedt, M.S.; Forsman, K.; Holmgren, G.; et al. Disease-causing mutations in the cellular retinaldehyde binding protein tighten and abolish ligand interactions. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 12397–12402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, A.; Maeda, T.; Palczewski, K. Improvement in rod and cone function in mouse model of Fundus albipunctatus after pharmacologic treatment with 9-cis-retinal. Investig. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 4540–4546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramtohul, P.; Denis, D. RPE65-Mutation Associated Fundus Albipunctatus with Cone Dystrophy. Ophthalmol. Retin. 2019, 3, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetto, M.; Hu, Y.; Li, B.; Chen, X.; Saraswat, V.; Damacio, F.; Smidak, R.; Palczewski, K.; Tochtrop, G.P.; Kiser, P.D. Rationally Designed, Short-Acting RPE65 Inhibitors for Visual Cycle-Associated Retinopathies. J. Med. Chem. 2025, 68, 17638–17652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dayma, K.; Rajanala, K.; Upadhyay, A. Stargardt’s Disease: Molecular Pathogenesis and Current Therapeutic Landscape. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 7006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntam, S.; Cingaram, P.R. CRISPR-Cas9 in hiPSCs: A new era in personalized treatment for Stargardt disease. Mol. Ther. Nucleic Acids 2023, 32, 896–897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dias, M.F.; Joo, K.; Kemp, J.A.; Fialho, S.L.; da Silva Cunha, A., Jr.; Woo, S.J.; Kwon, Y.J. Molecular genetics and emerging therapies for retinitis pigmentosa: Basic research and clinical perspectives. Prog. Retin. Eye Res. 2018, 63, 107–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bassetto, M.; Zaluski, J.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Badiee, M.; Kiser, P.D.; Tochtrop, G.P. Tuning the Metabolic Stability of Visual Cycle Modulators through Modification of an RPE65 Recognition Motif. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 8140–8158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaydon, Y.A.; Tsang, S.H. The ABCs of Stargardt disease: The latest advances in precision medicine. Cell Biosci. 2024, 14, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charbel Issa, P.; Barnard, A.R.; Herrmann, P.; Washington, I.; MacLaren, R.E. Rescue of the Stargardt phenotype in Abca4 knockout mice through inhibition of vitamin A dimerization. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8415–8420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Shah, S.M.; Mangwani-Mordani, S.; Gregori, N.Z. Updates on Emerging Interventions for Autosomal Recessive ABCA4-Associated Stargardt Disease. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 6229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cioffi, C.L.; Racz, B.; Freeman, E.E.; Conlon, M.P.; Chen, P.; Stafford, D.G.; Schwarz, D.M.; Zhu, L.; Kitchen, D.B.; Barnes, K.D.; et al. Bicyclic [3.3.0]-Octahydrocyclopenta[c]pyrrolo Antagonists of Retinol Binding Protein 4: Potential Treatment of Atrophic Age-Related Macular Degeneration and Stargardt Disease. J. Med. Chem. 2015, 58, 5863–5888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Racz, B.; Varadi, A.; Kong, J.; Allikmets, R.; Pearson, P.G.; Johnson, G.; Cioffi, C.L.; Petrukhin, K. A non-retinoid antagonist of retinol-binding protein 4 rescues phenotype in a model of Stargardt disease without inhibiting the visual cycle. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 293, 11574–11588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batty, P.; Fong, S.; Franco, M.; Sihn, C.R.; Swystun, L.L.; Afzal, S.; Harpell, L.; Hurlbut, D.; Pender, A.; Su, C.; et al. Vector integration and fate in the hemophilia dog liver multiple years after AAV-FVIII gene transfer. Blood 2024, 143, 2373–2385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fantaguzzi, F.; Tombolini, B.; Servillo, A.; Zucchiatti, I.; Sacconi, R.; Bandello, F.; Querques, G. Shedding Light on Photobiomodulation Therapy for Age-Related Macular Degeneration: A Narrative Review. Ophthalmol. Ther. 2023, 12, 2903–2915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stigzelius, V.; Cavallo, A.L.; Chandode, R.K.; Nitsch, R. Peeling back the layers of immunogenicity in Cas9-based genomic medicine. Mol. Ther. 2025, 33, 4714–4730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sakai, D.; Mandai, M.; Hirami, Y.; Yamamoto, M.; Ito, S.I.; Igarashi, S.; Yokota, S.; Uyama, H.; Fujihara, M.; Maeda, A.; et al. Transplant of Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell-Derived Retinal Pigment Epithelium Strips for Macular Degeneration and Retinitis Pigmentosa. Ophthalmol. Sci. 2025, 5, 100770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme/Transporter | Location | Primary Substrate(s) | Typical Km (approx.) | Cofactors/Requirements | Key Functional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPE65 | RPE (ER membrane) | All-trans-retinyl esters | 0.8–3 μM (for atRE) | Fe2+-dependent; requires LRAT-generated esters; membrane-associated | Rate-limiting isomerohydrolase; produces 11cROL [27]. |

| LRAT | RPE (ER membrane) | atROL + phosphatidylcholine | 2–7 μM (atROL) | Requires phosphatidylcholine; membrane-associated | Generates atRE substrate for RPE65; essential for cycle initiation; loss causes LCA; highly efficient in retinyl ester formation even at low [27]. |

| RDH5 | RPE | 11cROL → 11cRAL | 1–3 μM | NAD+-dependent | Main RPE enzyme for 11cRAL; reduced function causes FA [29,30]. |

| RDH11 | RPE | 11cROL, atROL | 2–5 μM | NADPH/NAD+ (dual) | Compensates for RDH5; detoxifies atRAL [29,30]. |

| RDH8 | Photoreceptor outer segment | atRAL → atROL | 0.1–0.4 μM (very low) | NADPH-dependent | Rapid atRAL clearance in photoreceptors; prevents toxicity; loss ↑ A2E accumulation [20]. |

| RDH12 | Photoreceptor inner segment | atRAL → atROL | 0.2–1 μM | NADPH-dependent | Inner-segment atRAL detoxification; mutations → LCA12/RP [20]. |

| ABCA4 | Photoreceptor disc membranes | A2PE | 1–3 μM | Requires ATP hydrolysis | Clears NRPE/atRAL adducts; defects → A2E accumulation (STGD1) [38,39]. |

| RLBP1/CRALBP | RPE & Müller cells | 11cRAL, 11cROL | Kd < 20 nM | Requires binding pocket integrity; no enzymatic cofactors | Stabilizes and traffics 11-cis-retinoids; essential for efficient chromophore delivery; mutations → FA and delayed dark adaptation [31]. |

| Disease | Key Mutated Genes | Toxic Metabolites | Core Pathogenic Mechanism | Representative Models | Current/Potential Therapies | Clinical Trial Status/Translational Stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STGD1 | ABCA4, RDH8 | A2PE, A2E, atRAL | ABCA4 transport failure → bisretinoid accumulation → RPE apoptosis [45] | Abca4−/−, Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice [39] | Visual-cycle modulators (emixustat) [120]; vitamin A deuteration (ALK-001) [121]; antioxidants (quercetin) [38]; gene therapy (dual-AAV, lentiviral, CRISPR) [122]. | emixustat Phase 3; ALK-001 Phase 2; STG-001 Phase 2a; Tinlarebant Phase 3; quercetin Phase 3; Gene therapy preclinical. |

| dry AMD | RPE65, ABCA4 variants | A2E, lipofuscin, ROS | Age-dependent decline in visual cycle efficiency → A2E/atRAL buildup → RPE/Bruch’s dysfunction [63] | Light-induced, Abca4−/− models, Abca4−/−Rdh8−/− mice [41,70] | apocarotenoids (BIO203) [68,69], complement inhibitors (ongoing trials), PBM [75,76]. | BIO203 preclinical/early clinical. |

| RP | LRAT, RPE65, RDH12 (among others) | atRAL excess | Chromophore crisis → ROS and oxidative stress → photoreceptor apoptosis [83] | Lrat−/−, Rpe65−/−, Rdh12−/− mice [86,87] | RPE65 gene therapy (Luxturna) [123], chromophore replacement (9-cis-retinyl acetate), CRISPR-based editing [36]. | RPE65 gene therapy FDA-approved; 9-cis-retinoids Phase 1/2; CRISPR editing in preclinical or early clinical. |

| LCA | RPE65, LRAT, RDH12 | atRAL, retinyl ester imbalance | Block in chromophore regeneration → congenital blindness [91] | Rpe65−/−, Lrat−/− mice [88,89] | RPE65 gene therapy (Luxturna) [123], gene therapy (in trials), chromophore replacement [100]. | RPE65 therapy FDA-approved; LRAT/RDH12 gene therapies in early clinical or preclinical development. |

| FA | RDH5, RLBP1 | Abnormal retinyl esters, impaired 11cRAL | Block in 11-cis-retinal regeneration → delayed dark adaptation [107,108] | Rdh5−/−, Rlbp1−/− mice [109] | AAV8-RLBP1 gene therapy (preclinical) [116,117], chromophore replacement (9-cis-retinyl acetate) [118], iPSC-based RPE replacement [57]. | AAV8-RLBP1 in preclinical stage; chromophore replacement Phase 1/2; iPSC-RPE early preclinical. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, X.; Fan, H.; Zhang, H.; Li, X. Mechanisms and Functions of Chromophore Regeneration in the Classical Visual Cycle: Implications for Retinal Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121676

Yu X, Fan H, Zhang H, Li X. Mechanisms and Functions of Chromophore Regeneration in the Classical Visual Cycle: Implications for Retinal Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy. Biomolecules. 2025; 15(12):1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121676

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Xinyue, Hao Fan, Hui Zhang, and Xiaorong Li. 2025. "Mechanisms and Functions of Chromophore Regeneration in the Classical Visual Cycle: Implications for Retinal Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy" Biomolecules 15, no. 12: 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121676

APA StyleYu, X., Fan, H., Zhang, H., & Li, X. (2025). Mechanisms and Functions of Chromophore Regeneration in the Classical Visual Cycle: Implications for Retinal Disease Pathogenesis and Therapy. Biomolecules, 15(12), 1676. https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15121676