1. Introduction

Flavor-changing neutral current (FCNC) processes play a central role in the search for physics beyond the Standard Model (SM) [

1]. Meson–antimeson transitions such as

and

[

2], along with rare meson decays, provide stringent probes of new physics at the TeV scale

1. These processes are being intensively studied at the LHCb [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7] and Belle II [

8,

9] experiments, building upon pioneering work at CLEO [

10], Belle [

11,

12], and BABAR [

13,

14]. The sensitivity of FCNC observables to beyond-the-SM (BSM) physics arises from a fundamental feature of the SM: the Glashow–Iliopoulos–Maiani (GIM) mechanism [

15] forbids FCNC at tree level, relegating them to highly suppressed loop-induced effects through penguin and box diagrams. Any tree-level contribution from new physics can therefore leave detectable imprints [

16], even if the associated energy scale lies well beyond direct collider reach.

Among BSM frameworks, models based on the

gauge group—collectively known as 3-3-1 models [

17,

18,

19,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35,

36,

37,

38,

39]—offer a particularly compelling structure for flavor physics. In these models, anomaly cancellation combined with asymptotic freedom naturally explains the existence of exactly three fermion families. Crucially, anomaly cancellation requires that one quark family transforms as a triplet under

while the other two transform as anti-triplets [

36,

40,

41]. This non-universal quark assignment inevitably generates tree-level FCNC mediated by both the

gauge boson and neutral scalars, including the SM-like Higgs boson. Among the various realizations of 3-3-1 models, we focus on the version incorporating right-handed neutrinos (331RHNs) [

37,

38], which avoids the Landau pole problem that afflicts the minimal 3-3-1 model below the symmetry-breaking scale [

42,

43,

44].

The phenomenology of FCNC in 331RHN models has evolved considerably over three decades of investigation. Early studies in the late 1990s and 2000s focused predominantly on

-mediated contributions [

45,

46,

47,

48], typically adopting quark mixing parameterizations inspired by, e.g., the Fritzsch ansatz. These analyses obtained lower bounds on the

mass ranging from a few TeV to tens of TeV, depending on the assumed flavor structure. However, a critical limitation of this early work was the systematic neglect of scalar contributions to FCNC—an oversimplification that, as recent work has shown, can lead to misleading conclusions about the viable parameter space.

The recognition that neutral scalars play an important role began in the 2010s [

49,

50], but most studies continued to treat scalar and gauge contributions separately. A major conceptual advance came with the realization that the SM-like Higgs boson, being the lightest neutral scalar at

GeV, generically provides the dominant contribution to meson transitions [

51]. Unlike

contributions, which can be suppressed by increasing the gauge boson mass, scalar-mediated FCNCs scale as

and are tied to quark masses and Cabibbo–Kobayashi–Maskawa parameters. This poses a fundamental challenge: any proposed parameterization of the quark mixing matrices must be tested against the SM-like Higgs contribution to ensure consistency with experimental limits on

, the mass difference between a meson

and its antiparticle, which characterizes the transition frequency.

The most recent and impactful development is the identification of the alignment limit [

52]—a specific configuration of scalar mixing angles that naturally suppresses FCNC mediated by the SM-like Higgs. Within this limit, two different scenarios emerge depending on whether FCNC arises in the up-quark sector (allowing

masses as low as a few hundred GeV) or the down-quark sector (requiring

masses in the hundreds of TeV range). This discovery fundamentally changes our understanding of the 331RHN parameter space and clarifies the relationship between scalar alignment, quark mixing patterns, and experimental constraints from neutral meson systems.

This review provides a comprehensive overview of FCNC phenomenology in the 331RHN model, synthesizing three decades of theoretical progress. We emphasize throughout that any meaningful analysis of FCNC in 3-3-1 models must account for contributions from all neutral mediators—gauge bosons and scalars alike—with particular attention to the role of the SM-like Higgs. The review is organized as follows.

Section 2 introduces the 331RHN model, detailing the scalar and gauge sectors.

Section 3 discusses the general structure of tree-level FCNC and explains how different choices of which quark family transforms as a triplet lead to distinct model variants.

Section 4 presents explicit FCNC interactions and meson transition formulae for each variant.

Section 5 traces the historical development of FCNC studies in 331RHN, from early

-dominated analyses through the gradual incorporation of scalar effects up to the recent alignment limit framework, while also covering family discrimination,

Z-

mixing constraints, and updated bounds on new physics masses. Finally,

Section 6 synthesizes the main lessons learned over three decades, discusses open theoretical questions including the physical origin of the alignment limit and the role of right-handed quark mixing, and outlines experimental prospects across different mass scales—from direct

searches at the HL-LHC to ultra-precision flavor measurements at Belle II and future kaon experiments. We conclude by emphasizing that the interplay between collider searches and precision flavor physics will be decisive in testing the 331RHN framework in the coming decade.

2. The Essence of the 331RHN

The 331RHN addresses fundamental questions left unanswered by the SM, such as the origin of fermion families, electric charge quantization, and neutrino masses. In this section, we review the essential features of the 331RHN model.

In

models, the electric charge operator takes the form

where

e is the electron electric charge,

and

are the diagonal Gell-Mann matrices,

is an embedding parameter,

N is a free quantum number, and

I is the identity operator. The value of

determines the specific version of the 3-3-1 model. For example,

corresponds to the minimal 3-3-1 model, whereas the 331RHN requires

.

Once

is fixed, the electric charge operator

becomes a function of the quantum number

N. For the 331RHN model, the relation between the electric charge operator and the group generators is

which implies the following electric charges for the fermionic multiplets:

Thus, by fixing the values of

N, we automatically determine the electric charge pattern of the model’s particles.

It was shown in Refs. [

53,

54] that, in any 3-3-1 model, the invariance of Yukawa interactions, combined with anomaly cancellation, provides the constraints needed to fix all

N values. Consequently, 3-3-1 models offer an explanation for the pattern of electric charge quantization. For example, for the lepton triplet, the approach discussed above provides

, while for the lepton singlet,

, which implies the following electric charges for the leptons:

with

labeling the three lepton families.

Following the same approach for the quark sector (which we will discuss in more detail in

Section 3 and

Section 4), the quantum number

N acquires the value

for the quark triplet, giving the following charge distribution:

while for the anti-triplet of quarks, we have

, giving the following electric charges:

For the singlet of quarks, invariance of the Yukawa terms and anomaly cancellation provide and . Observe that, in the 331RHN, the new quarks have standard electric charges. The same approaches apply to the scalar and gauge sectors.

We now turn to the scalar sector, crucial for symmetry breaking and mass generation. The model contains three scalar triplets [

37,

38],

where

and

transform as

and

as

.

The most economical pattern of spontaneous symmetry breaking occurs when only

,

, and

acquire non-zero vacuum expectation values (VEVs), namely

,

, and

, respectively. For simplicity, we will assume this configuration in what follows. Scenarios where all neutral scalars acquire VEVs are also interesting but more complex since the standard quarks mix with the new ones [

55].

The scalar spectrum is obtained from the potential

shifting the neutral scalar fields as

The above potential is the most economical one [

56], which conserves the lepton number. Moreover, it is invariant under a

discrete symmetry defined as

2Substituting the above shifts into the potential, we obtain the conditions ensuring a global minimum of the potential

3:

To reproduce the SM electroweak scale, we will take

, where

(see Equation (

25)), while

sets the

breaking scale. Moreover, current LHC constraints require

[

60,

61], implying that

. This hierarchy will play an important role in the discussion below.

The scalar mass matrices can be obtained only after solving the potential’s minimization condition. The mass matrix for the CP-even neutral scalars in the basis

is

In what follows, we adopt the decoupling limit

4, which amounts to decoupling

from

and

. This requires

In this limit, the mass matrix reduces to

in the basis

. After diagonalization, the CP-even eigenstates are

Here,

is a heavy CP-even scalar with mass set by

. The remaining CP-even scalars are

h (the SM-like Higgs) and

H, whose mass depends on

f and

. The angle

diagonalizes

via a

rotation. For the explicit diagonalization procedure, we refer the reader to Refs. [

62,

63].

Next, we consider the CP-odd scalars. Considering the basis

, the mass matrix is

This matrix can be diagonalized analytically. Assuming

, we obtain two zero eigenvalues, which correspond to the eigenstates

and

, and a massive eigenstate

with mass given by

. We define

and

. Note that if

, then

, meaning that

A is a pseudo-Goldstone boson associated with some U

global symmetry. In fact, it was shown in Ref. [

56] that U

is the Peccei–Quinn symmetry and

A is the Weinberg–Wilczek axion [

64,

65]. This axion must, of course, be avoided. The trilinear term

minimally breaks the Peccei–Quinn symmetry while preserving lepton number

5.

The 331RHN has two other neutral scalars,

and

. Both carry two units of lepton number [

67]. Assuming lepton number conservation, they do not mix with

,

, or

. In the basis

the mass matrix reads

After diagonalizing it, we obtain

, which is a Goldstone boson absorbed by the non-Hermitian gauge bosons

and

. The other neutral scalar is

, with mass

. This mass depends on

f and

, which means that

is a heavy particle regardless of the value of

f. Moreover, due to lepton number conservation, and because

is a bilepton, its interactions must involve another bilepton of the model such as the new quarks,

,

, or

. If

is the lightest bilepton, it is stable and can serve as a dark matter candidate [

67,

68].

We now discuss the charged scalars. In the basis

, the mass matrix is given by:

We note that

and

also carry two units of lepton number each [

67]. Thus, lepton number conservation prevents their mixing with

. After diagonalizing this matrix we obtain two Goldstone bosons:

and

, which are absorbed by

and

. The remaining two heavy charged scalars are

with mass

and

with mass

. The dependence of

on

f and

ensures that

remains heavy, similarly to

discussed above.

In summary, the scalar spectrum of the 331RHN model comprises nine physical states beyond the SM. Apart from the SM-like Higgs boson

h, the scalar spectrum contains four heavy scalars (

,

, and

) with masses set by the 3-3-1-breaking scale

, and four additional scalars (

H,

A, and

) whose masses are determined by the trilinear coupling

f. The role of this coupling in explicitly breaking the Peccei–Quinn symmetry makes the phenomenology of the model strongly dependent on its value [

69].

Two distinct regimes emerge: (i) When

, the scalars

h,

H,

A, and

form a light spectrum at the electroweak scale, effectively realizing a Two-Higgs-Doublet Model (2HDM) structure with additional heavy states decoupled at the TeV scale. This regime leads to rich phenomenology accessible at current colliders, including modified Higgs couplings, new decay channels, and potential signals in flavor physics. (ii) Conversely, when

, all new scalars become heavy and degenerate at the 3-3-1 scale. In this case, the low-energy theory reduces to the SM augmented by higher-dimensional operators suppressed by powers of

, making direct detection challenging and shifting the focus to precision measurements and indirect searches [

69].

This dichotomy in the scalar spectrum illustrates an important feature of the 331RHN model: depending on the symmetry-breaking pattern, it can manifest either as a multi-Higgs model with rich collider phenomenology or as an effective SM with small deviations observable only through precision tests. Determining which regime is realized requires dedicated experimental searches for both direct production of new scalars and precision measurements of SM processes.

We now review the 331RHN gauge sector. It contains the eight gluons, eight SU

bosons

, and a single U

boson

. The SU

U

sector mixes to yield the four SM electroweak bosons and five additional heavy states. To obtain the corresponding spectrum, we expand the scalar kinetic term,

where the covariant derivative is defined as

where

(

being the Gell-Mann matrices) with

,

g is the SU

gauge coupling, and

is the coupling associated with U

. The matrix

is given by

From this kinetic term, after the spontaneous symmetry breaking of

into the standard

, we obtain the following set of eigenstates:

where

and

, with

being the Weinberg angle. The neutral gauge boson

is associated with the hypercharge generator of the U

abelian group. Then, after the electroweak symmetry breaking of

into

, the

boson mixes with

to form the standard physical charged gauge bosons,

, and

combines with

to compose the photon and the standard massive neutral gauge boson,

and

, where

and

.

In summary, the 331RHN model contains the following spectrum of gauge bosons:

whose masses correspond to

From these expressions, we infer that

with

GeV. Also, to match the 331RHN model with the SM, it can be shown that

g and

are related by

where

denotes the weak mixing angle evaluated at the

scale.

A notable feature of the 331RHN model is that

. For a detailed discussion on the value of

in 3-3-1 models, see Ref. [

70]. Note also that

and

mix into two physical states,

and

, where

is given by [

70]

This mixing angle is strongly suppressed and can be neglected in the gauge boson mass spectrum [

67,

70,

71,

72], although it plays a role in flavor-changing neutral current processes, such as meson transitions, as discussed in

Section 5.

Moreover, for

, it follows that

implying that

is the heaviest gauge boson in the model.

3. The Structure of Flavor-Changing Neutral Interactions in the 331RHN

As mentioned previously, FCNC processes in 3-3-1 models are unavoidable and arise at tree level, a stark contrast to the SM, where such processes are forbidden by the GIM mechanism and appear only at loop level, suppressed by the smallness of CKM entries and loop factors. The tree-level emergence of FCNC in 3-3-1 models has a fundamental origin: anomaly cancellation requires that one quark family transforms as a triplet under SU

while the other two transform as anti-triplets. This non-universal transformation property breaks the flavor symmetry that protects the SM from tree-level FCNC. Consequently, the neutral gauge boson

and the neutral scalars (

h,

H,

A,

) couple non-diagonally to quarks in the mass basis, mediating FCNC processes such as

K–

transitions,

–

transitions, and rare decays, e.g.,

and

. Since the mass of

is proportional to

, it is one of the heaviest neutral scalars, and its contribution is usually neglected in FCNC analyses. The standard

Z boson contributes to these processes only through

Z-

mixing, which is suppressed by

and hence negligible for

a few TeV [

67,

71,

72]. This tree-level structure makes FCNC observables extraordinarily sensitive probes of the 3-3-1 scale, often providing constraints comparable to or stronger than direct searches at colliders.

Before discussing FCNC in detail, we establish the notation for quark mass eigenstates. The quark fields in the interaction (flavor) basis,

and

, are related to the physical mass eigenstates,

and

, by unitary transformations:

These mixing matrices generalize the CKM matrix of the SM and encode the non-trivial flavor structure induced by the extended gauge symmetry. The mismatch between left- and right-handed rotations,

and

, is precisely what generates tree-level flavor changing couplings to neutral currents, a phenomenon absent in the SM where

and

can be absorbed into field redefinitions without physical consequences.

Throughout this work, we use a basis where the right-handed quark fields are diagonal. In this convention, all flavor mixing is encoded in the left-handed rotation matrices

and

, which satisfy the relation

, where

is the CKM matrix [

73]:

We now focus on Yukawa interactions. The fact that one fermion family transforms as a triplet and the others as anti-triplets under SU requires fermion masses to arise from more than one VEV, leading to FCNC. Depending on which family transforms differently, three distinct sets of Yukawa interactions can be written, each defining a variant of the model. Thus, each 3-3-1 model has three variants. Below, we present these three variants of the 331RHN model in a general form.

Variant I corresponds to the scenario where the first two quark families transform as anti-triplets and the third family as a triplet under

. In this case, the quark content and its transformations under the gauge symmetry are

where the index

is restricted to only two generations. The negative sign in the anti-triplet

is used to standardize the signs in charged-current interactions with the gauge bosons. The primed quarks are new heavy quarks with the usual

electric charges. The simplest Yukawa interactions that generate the correct masses for all standard quarks and are invariant under the

symmetry are given by the terms

6

where

and the parameters

and

are Yukawa couplings that, for the sake of simplification, we assume to be real.

In what we call variant II, the second family transforms as a triplet, while the first and third transform as anti-triplets. The quark content transforms as

where

. The Yukawa interactions among the scalars and the standard quarks satisfying the

symmetry are

Finally, variant III is characterized by the first family transforming as a triplet and the second and third as anti-triplets, so the quark content is defined by

with

, and the respective Yukawa interactions are given by

The FCNC mediated by neutral gauge bosons arises from the fermionic kinetic terms

where

f represents a fermion of the model. The covariant derivative,

, acts differently in quark triplets or anti-triplets, so the interactions from these terms are variant-dependent.

For the case of variant I the covariant derivative acts as

with

.

For variant II the covariant derivative is defined as

with

.

Finally, the covariant derivative of variant III is

with

.

As mentioned, FCNC processes are an unavoidable feature of 3-3-1 models, arising from the requirement of anomaly cancellation. The flavor structure of the model depends critically on which quark family transforms differently under the

gauge group. Recent studies indicate that it is the third family that plays this distinct role [

45,

52,

74]. This choice is further motivated by phenomenological considerations: the top quark, being the heaviest and shortest-lived quark, decays before it can form mesonic bound states, so does not participate in neutral meson transitions. Then, the only relevant neutral bound state formed by up-like quarks is the

D meson—unlike down-type quarks which form

K,

, and

mesons. Consequently, variant I, where the third family transforms as a triplet, naturally suppresses the most stringent FCNC constraints while maintaining the rich phenomenology in all neutral meson systems. For these reasons, throughout the remainder of this work, we focus mainly on variant I.

4. FCNC and the Variants of the Model

Having established the general structure of flavor-changing interactions in

Section 3, we now present explicit formulae for the mass differences of the three variants of the 331RHN model. This section provides the complete set of FCNC interactions mediated by neutral scalars (

h,

H,

A) and gauge bosons (

), highlighting how the choice of variant—determined by which quark family transforms as a triplet under

—directly impacts the flavor structure of these couplings.

Using the scalar spectrum from

Section 2 and the Yukawa interactions from

Section 3, we derive the FCNC couplings of neutral scalars to quarks. The set of interactions mediated by the SM-like Higgs

h and the heavier CP-even scalar

H that lead to FCNC processes is given by

while the interactions involving the CP-odd pseudoscalar

A are given by

where

, with

and

, and

and

are the mixing angles of the CP-even and CP-odd low-energy scalars, respectively, as presented in

Section 2. The angle

satisfies

. Crucially, the relevant entries of the quark mixing matrices in these interactions are parametrized by the index

x, whose value depends on the variant choice as specified in

Table 1.

It can be seen in Equations (

41)–(

43) that the scalar-mediated FCNC amplitudes depend on the mixing angles

and

, as well as on the quark mixing matrices

. While the masses of

H and

A remain free parameters of the model, the SM-like Higgs mass is fixed at

GeV [

75,

76]. Being the lightest neutral scalar,

h generically provides the dominant contribution to FCNC observables, thereby imposing stringent constraints on the parameter space. These constraints can be significantly relaxed by imposing the alignment condition,

, which ensures that the SM-like Higgs couples to quarks in a flavor-diagonal manner at tree level. Under alignment, FCNC processes are mediated exclusively by the heavier scalars

H and

A, whose contributions are expected to be mass-suppressed.

In addition to the scalar contributions discussed above, the

gauge boson mediates FCNC at tree level through its non-diagonal couplings to quarks. From the fermionic kinetic terms presented in

Section 3, these flavor-violating interactions are given by

7 The flavor-changing interactions in Equations (

41)–(

45) imply the following contributions to the mass difference

, governing the transition frequency of the neutral meson

:

where

GeV is the SM-like

Z boson mass and

is the Fermi constant. The Wilson coefficients

are written in detail in

Appendix A, and their calculation follows the methodology of Ref. [

78]. The hadronic parameters entering these expressions are summarized in

Table 2. The factor

accounts for renormalization group (RG) evolution from the scale of new physics down to the meson mass scale; at leading order,

. For details on these factors see the

Appendix B. The contribution of the SM-like

Z boson, in case of non-negligible mixing with the

, can be computed by replacing

in Equation (

49).

The equations above highlight an important distinction between scalar- and gauge-mediated contributions: scalar contributions depend on both the quark mixing matrices and the scalar mixing angles and , while -mediated processes depend on alone. Additionally, the mixing angle, , introduces further FCNC sources, with the physical SM-like boson acquiring flavor-violating couplings proportional to the mixing angle and specific entries of . The constraints from the CKM factorization, , and unitarity, , are not sufficient to determine this quark mixing pattern. In the absence of experimental input, an infinite number of configurations remain possible.

Different phenomenological approaches have been developed to address this ambiguity. Some studies adopt specific parameterizations or textures for inspired by quark mass matrix ansätze, while others explore the full parameter space through numerical scans. A complementary strategy considers limiting cases such as (restricting FCNC to down-type quarks) or (restricting them to up-type quarks), or more general configurations where both matrices exhibit non-trivial flavor structure. The treatment of Z- mixing also varies: some analyses include it explicitly to constrain the mixing angle from FCNC data, whereas others work in the limit where this mixing is negligible. This diversity of approaches underscores both the richness of the 331RHN flavor structures and the complementary roles of different observables in probing the model’s parameter space.

Having established the theoretical framework for FCNC in the 331RHN model, we now review how these processes have been phenomenologically studied over the past three decades. In

Section 5, we survey the evolution of FCNC analyses in 3-3-1 models, highlighting the different strategies employed to constrain the parameter space, from early

-dominated studies using specific mixing matrix parameterizations to recent investigations incorporating family discrimination, mixing effects

and scalar alignment. This historical perspective contextualizes the evolution of FCNC phenomenology in 3-3-1 models, illustrating how successive strategies have progressively improved our understanding of the parameter space and clarified the role of the SM-like Higgs.

5. The State of the Art of FCNC Processes Within the 331RHN

The investigation of FCNCs in the 331RHN model has evolved considerably over the past three decades, developing from early -dominated analyses to a more comprehensive framework that acknowledges the interplay between the gauge and scalar sectors. This section briefly traces the historical development of FCNC phenomenology in 331RHN models, organizing the discussion chronologically to highlight how theoretical understanding has deepened—from the initial studies that entirely neglected scalar contributions, through the subsequent recognition of the heavy neutral scalars H and A, to the recent realization that the SM-like Higgs h plays a decisive role in constraining the model’s parameter space. A central theme has emerged: any parameterization of the quark mixing matrices must be validated not only against -mediated processes but also against scalar-mediated contributions, particularly those involving the lightest scalar state. The alignment limit—a configuration where the SM-like Higgs decouples from FCNC—marks a crucial development that profoundly reshapes our understanding of the viable parameter space in these models.

Early studies of FCNCs in the 331RHN model appeared in the late 1990s. The first, Ref. [

45], examined the variant I of the model. In that work, the authors—neglecting scalar contributions—examined the impact of

on the mass differences in neutral meson systems such as

,

and

. The analysis was carried out under the assumption of the Fritzsch ansatz for quark mixing, a pioneering framework proposed to explain the structure of the CKM matrix [

80]

where the index

, for

. As a result, the

mixing yielded a lower bound

TeV. Subsequently, these results were refined using the then-available experimental data on the rare kaon decay

, which raised the lower bound on

to

–

TeV [

46].

The constraints obtained under the Fritzsch parameterization, while offering valuable early benchmarks, must be interpreted with caution. As discussed below, any parameterization of the mixing matrices is experimentally viable only if the SM-like Higgs contribution to FCNC processes remains within experimental limits—a requirement not accounted for in these early analyses.

Several papers on FCNC in the 331RHN model appeared in the early 2000s. One of them was Ref. [

47], which focused exclusively on FCNC processes mediated by the

. In addition to neutral meson transitions, the authors studied

,

, and

decays. In all cases, the authors found that the contributions from rare

B decays are much smaller than those from

and

mass differences, and thus the model predicts no substantial contribution to these rare

B-decays. Moreover, lower bounds on

of order tens of TeV are obtained if a Fritzsch-like structure for the mixing angles is assumed.

A similar approach was adopted in Ref. [

48], this time employing textures for the quark mass matrices. Specifically, four different ansätze for these matrices were analyzed. By comparing the theoretical predictions with the measured mass difference of the

system, the authors derived lower bounds on

ranging from 1 to 30 TeV.

Towards the end of the 2000s, two notable works broadened the study of FCNC processes in the 331RHN model by introducing new tree-level contributions arising from mixing between exotic and standard quarks, as well as mixing between CP-even and CP-odd neutral gauge bosons [

81]. The authors analyzed additional effects on meson–antimeson transitions due to the presence of exotic quarks and found consistency with

values of order tens of TeV. Following this direction, the authors of Ref. [

82] derived bounds on

from neutral meson mixing and rare quark decay data, examining scenarios where standard quarks mix with exotic ones. A key result was that if the CKM matrix element

is significantly smaller than 1, the model predicts enhanced rates for rare top decays such as

,

, and

. However, to remain consistent with current experimental constraints,

must exceed 10 TeV provided that

.

Throughout the 1990s and the first decade of the 2000s, the theoretical landscape of FCNCs in 331RHN models shared a common feature: constraints were derived almost exclusively from

-mediated processes, with each study relying on specific parameterizations of the quark mixing matrices. While this approach yielded valuable early insights, it overlooked a crucial component of the model’s phenomenology—the scalar sector, and in particular, the role of the SM-like Higgs boson. Some works in the 2010s continued to examine only

-mediated FCNC processes. For instance, in Ref. [

83], the authors examined the complementarity between FCNC constraints and dilepton resonance searches at the LHC Run 2, conducted at

TeV with an integrated luminosity of

. The analysis concluded that a

with a mass in the few-TeV range remains consistent with FCNC bounds, depending on the chosen parameterization of the quark mixing matrices.

The first study investigating FCNC processes in the 331RHN model mediated by neutral scalars was presented in the early 2010s in Ref. [

49]. In this work, the authors concluded that the most stringent constraint on the model, based on a specific parameterization of the quark mixing matrices

, arises from the precise measurement of the

system. This analysis yielded the bounds

TeV and

TeV. The inclusion of heavy neutral scalars

H and

A represented a valuable step forward; however, neglecting the contribution from SM-like Higgs remains an oversimplification.

A subsequent work took an opposite approach, neglecting

contributions to

mixing and focusing exclusively on neutral scalar mediators, including the SM-like Higgs [

50]. The authors showed that, for a specific choice of the

parameterization, the heavy scalars

H and

A can have masses at the electroweak scale while remaining consistent with meson-mixing constraints.

Still in the 2010s, Buras and his collaborators initiated a series of investigations on flavor physics within the framework of 3-3-1 models. The first one we highlight here is Ref. [

84]

8. This paper explored a broad range of observables, including meson–antimeson transitions, rare semileptonic decays, and the top quark decay channel

. All processes were mediated exclusively by

and assumed a specific parameterization of

. Through a rigorous analysis of

and

processes, they demonstrated that a

boson with a mass at the TeV scale can still be consistent with existing flavor physics constraints.

The second paper we highlight is [

87]. In this paper the authors investigated how 3-3-1 models confronted new data on

and

taking into account constraints from

observables, low-energy precision measurements, LEP-II, and LHC data. For the particular case of the 331RHN model, and considering a specific parameterization for the

, the authors concluded that a

with mass of a few TeV could accommodate the flavor puzzle at that time.

Another important contribution came later with Ref. [

70], where the authors investigated the impact of the

mixing. They calculated the impact of this mixing on rare

K,

, and

decays. For the particular case of the 331RHN, they found that the mixing can indeed be neglected in

transitions and in decays such as

[

88,

89]. However, tree-level

exchanges can produce sizable corrections in decays sensitive to axial-vector couplings—such as

and

—and in channels involving neutrinos in the final state, like

,

, and

, which generally cannot be neglected. They also analyzed for the first time the ratio

in 3-3-1 models including both

Z and

contributions. Importantly, they also demonstrated that the choice of fermion representations under

has direct phenomenological consequences. As the main result, they concluded that the interplay of new physics effects in electroweak precision observables and flavor observables could help identify the favored 3-3-1 model.

Motivated by the findings that the ratio

in the SM appeared significantly below the experimental data, the paper [

90] investigated whether the necessary enhancement of

could be obtained in 3-3-1 models. The work took into account contributions from

and

. In a subsequent paper [

91], the authors addressed the tension in

processes in relation to

,

and

.

Similar methodologies were later adopted in the early 2020s. Notably, in Ref. [

92] the authors provided a detailed analysis of the charm sector within 3-3-1 models, while in Ref. [

93] the decay

was analyzed and correlated to the processes

and

. Collectively, all these studies reinforced that a

boson with mass in the TeV range remains compatible with the experimental bounds available at that time. More recently, in the paper [

94], the authors updated the predictions of 3-3-1 models for rare

B and

K decays, and

processes.

We highlight here that in all these works, the authors deliberately omitted the contributions from neutral scalar particles in

processes. Moreover, it is important to emphasize the strong dependence of

mass constraints from FCNC processes on the specific parameterizations of the quark mass matrices. This line of investigation persisted as the dominant approach until the early 2020s [

83,

95]. In these works, the authors employed ansätze for quark mixing matrix parameterizations inspired by texture-zero structures to examine FCNC effects mediated by the

boson.

To illustrate how different parameterizations of quark mixing, determined from specific configurations of

, can substantially affect predictions for meson transitions, consider a comparison between Refs. [

49,

95]. In the former, a particular parameterization of the

matrices led to the bound

TeV from the

transition. In contrast, the latter revisited the same process using updated experimental data and an alternative parameterization, obtaining instead

TeV. This two-order-of-magnitude discrepancy underscores the sensitivity of FCNC constraints to the assumed quark mixing structure.

This large variation in constraints—spanning two orders of magnitude—marks a fundamental challenge in FCNC phenomenology within 3-3-1 models: Which parameterizations, if any, are physically consistent once all mediators are included? Addressing this problem requires a systematic framework that incorporates all neutral mediators, both scalars and gauge bosons, while simultaneously considering all four neutral meson systems.

As mentioned in previous sections, a key feature of 3-3-1 models is the need to assign one quark family to transform as a triplet under SU

, while the other two transform as anti-triplets, a choice that directly impacts FCNC processes. In particular, Ref. [

74] analyzed the contribution of the pseudoscalar

A, which in principle can be even lighter than the SM-like Higgs, to the

transition. Their results demonstrated that different family assignments lead to distinct bounds on the pseudoscalar mass, with the case where the third family transforms as a triplet (variant I) being the most favored, highlighting the impact of the family assignment on FCNC processes

9. Results on the issue of family discrimination are presented in detail in

Section 5.1.

The role of the SM-like Higgs boson in FCNC processes was examined in detail in Ref. [

51]. The terms in Equation (

41) lead to top quark decays such as

and

, through Yukawa interactions,

The ATLAS bounds on these top decays are found in Ref. [

97] and impose

and

. In this case, it is necessary to verify if the Yukawa interactions in Equation (

41) satisfy such bounds. The authors found both

and

to be of order

.

In addition to the contributions from

h,

H,

A, and

, the 3-3-1 framework also features

Z-

mixing, which introduces additional sources of FCNC. This mixing, governed by the angle

, implies that the SM-like boson

Z can also mediate meson transitions. Ref. [

51] analyzed this effect by studying the combined contributions of

h,

, and

Z to

,

, and

. By exploring different scenarios for the relative weight of each mediator, they showed that meson transitions serve as a powerful indirect probe of the

Z–

mixing angle, while remaining consistent with collider bounds on flavor-changing top decays. Bounds on this mixing angle are further discussed in

Section 5.2.

These studies emphasized that any proposed parameterization of the quark mixing matrices must be validated against the SM-like Higgs contribution to meson–antimeson transition observables, ensuring that its effect remains within the experimental uncertainty of measurements. As an illustrative case, the previous paper proposed a parameterization for that yields a contribution from the SM-like Higgs to well within the experimental error margins. Once this parameterization was shown to be consistent with the SM-like Higgs contribution, the analysis proceeded to assess the impact of the on transition. The results revealed that, depending on how significantly the -mediated process contributes to the experimental uncertainty in relative to the scalar sector, the allowed mas range extends from a few hundred GeV up to several hundred TeV.

An important step toward a more realistic treatment of flavor physics in the 3-3-1 framework was achieved in Ref. [

51], where the authors carried out a detailed analysis of FCNC mediated by both scalar and gauge sectors. In that work, the scalar mass matrix was explicitly constructed and diagonalized, enabling the identification of the SM-like Higgs boson within the 3-3-1 scalar spectrum. To handle the complexity of the scalar potential, the authors adopted the so-called decoupling limit, a specific region of parameter space in which the SM-like Higgs reproduces the SM behavior, while the heavy neutral scalars naturally decouple from low-energy flavor observables. In that article, the quark mixing matrices were determined by assigning specific weights to the Higgs contributions, and the resulting impact on

-mediated transitions was subsequently evaluated.

Another important investigation into the role of the SM-like Higgs in flavor physics within the 331RHN model was recently presented in Ref. [

52]. Unlike

-mediated FCNCs, scalar-induced meson transitions cannot be suppressed by simply increasing the mediator mass [

49,

50,

74], since one particle must reproduce the 125 GeV boson of the SM. To quantitatively assess the impact of the SM-like Higgs boson on flavor observables, this work formally introduced the concept of the alignment limit, which specifies the conditions on scalar mixing that suppress the participation of this particle in FCNC interactions.

It was observed that three crucial features emerge from the Lagrangian in Equation (

41). First, for variant I, the FCNC interactions arise exclusively through combinations of the elements of the mixing matrix

and

. Index 3 reflects this family-specific transformation property. For alternative scenarios (variants II or III), the relevant indices shift accordingly while maintaining analogous matrix element dependencies. Any phenomenologically consistent FCNC study in this context must respect

factorization in

and

, which imposes non-trivial correlations between the four relevant mesons. On the other hand, note that neither this requirement nor the unitarity of individual matrices is sufficient to unambiguously define

and

. However, among the infinite possible quark mixing scenarios, two trivial cases stand out: either

or

can be set equal to the identity matrix, leaving the other as the CKM matrix. These cases represent two extreme, yet illustrative scenarios of quark mixing patterns.

Second, the FCNC interaction mediated by h depends on the amplification factor . This function reaches its minimum value when , which corresponds to the maximum mixing (). Any deviation from (either or ) enhances , thus amplifying the contributions of FCNC. This establishes as the optimal parameter choice for the suppression of FCNC.

Third, the critical dependence on

reveals a novel alignment mechanism. The condition

completely decouples the SM-like Higgs

h process from the FCNC, defining the alignment limit of the 3-3-1 model. This work presents the first systematic derivation of this alignment condition within the 3-3-1 framework, establishing

as the crucial relationship for Higgs-mediated FCNC suppression.

Note that SM predictions for are consistent with the experimental measurements within the range. Therefore, any new physics contribution must remain below the corresponding experimental uncertainty, namely . In the following, will denote the total contribution to that arises from the 3-3-1 model.

Having established the central role of the alignment limit and the importance of quark mixing parameterization, we now turn to specific phenomenological applications that have increased our understanding of the 331RHN parameter space. We organize these studies thematically, beginning with the question of family discrimination—which quark family transforms as a triplet under ?—followed by analyses of Z- mixing effects and detailed investigations of the scalar sector’s impact on meson transitions and its influence on lower bounds on .

5.1. Family Discrimination

A distinctive feature of 3-3-1 models is that anomaly cancellation requires one quark family to transform as a triplet under SU

, while the other two must transform as anti-triplets. Since theory does not predict which family should take this role, it becomes essential to explore physical processes that can discriminate among these possibilities. Such an arrangement necessarily leads to FCNC interactions at tree level, mediated by neutral scalars and gauge bosons. While early studies focused on the role of the

boson as the dominant mediator [

45,

98], Ref. [

74] revisited the problem by considering the pseudoscalar

A, which was argued to possibly be the lightest particle on the 3-3-1 spectrum [

99,

100]. This motivated an analysis of whether meson transitions, particularly the

system, are sensitive to the choice of family assignment, which suggested masses in the TeV range.

The authors derived the effective pseudoscalar interactions with quarks for the three possible variants of family assignment and studied their contributions to

. Since the theoretical prediction within the SM suffers from QCD uncertainties but remains consistent with experimental data [

101,

102,

103], they adopted a conservative approach and required that the new contribution from the 3-3-1 model should not exceed the experimental uncertainty,

MeV [

104,

105,

106,

107]. To implement this condition, the quark mixing matrices

and

were parameterized consistently with the CKM relation

and explored numerically through random sampling of their entries. This allowed for an exhaustive test of possible textures that respect both unitarity and CKM constraints. As an illustrative example, they present the following texture:

Note that in Ref. [

74], the authors neglected the CP phase:

.

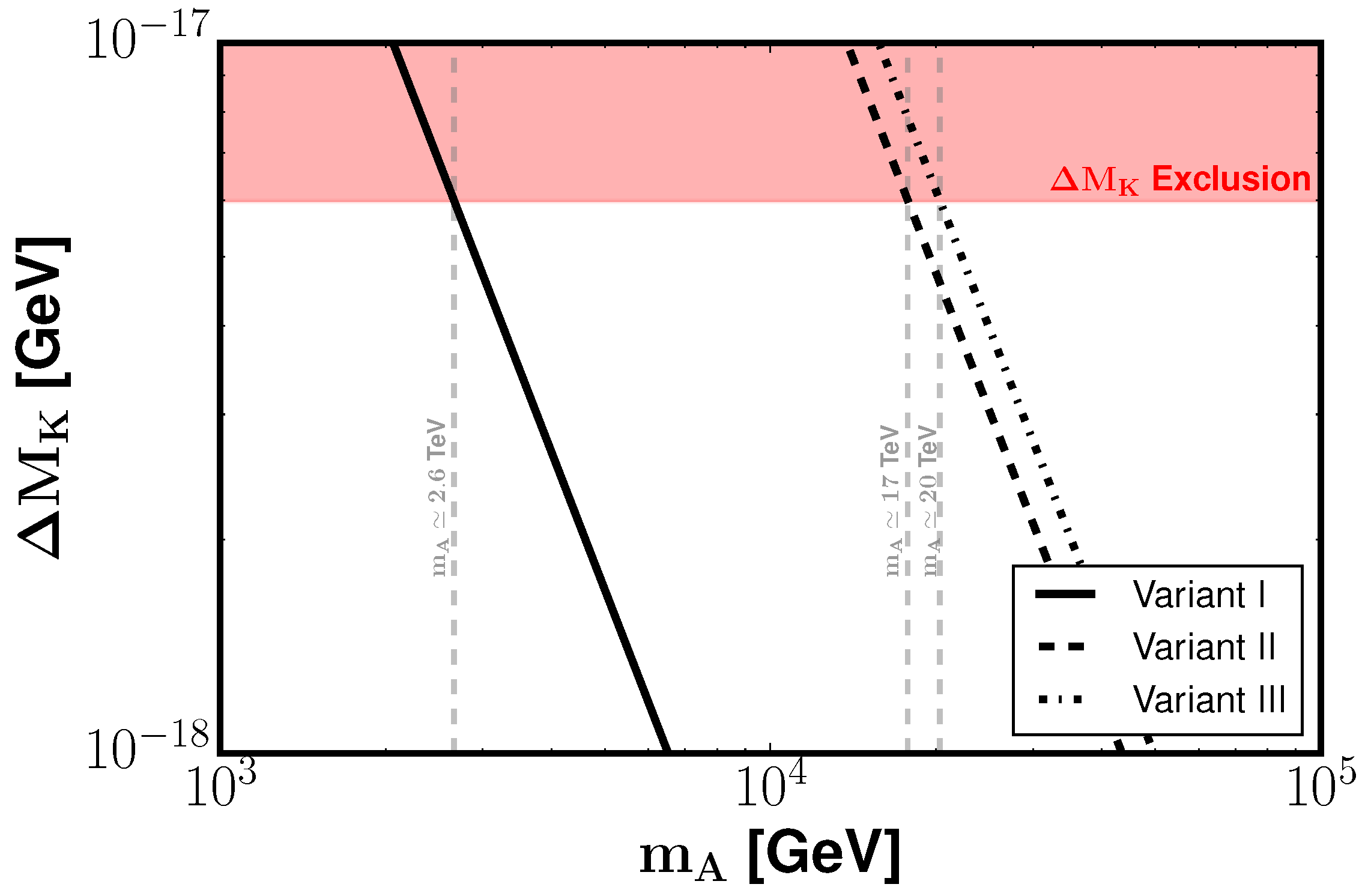

The numerical analysis revealed that FCNC processes are highly sensitive to family discrimination, as shown in

Figure 1, since the pseudoscalar contribution to

scales with the fourth power of the mixing elements of the matrix, as shown in Equation (

47). Each family assignment resulted in different lower bounds on the pseudoscalar mass. Variants II and III, where the first or second family transforms as a triplet, respectively, produced very stringent bounds, pushing

into the multi-TeV regime (

–20 TeV). In contrast, variant I, where the third family transforms as a triplet, led to a significantly weaker constraint (

TeV), making it the most energetically favorable configuration. These findings reinforce earlier conclusions that the third family plays a special role in 3-3-1 models [

45,

98], while also establishing the pseudoscalar as a powerful probe of family discrimination. The study thus provided both the most stringent bounds on the pseudoscalar mass in this framework and strong evidence favoring the assignment of the third family to the SU

triplet representation.

The sensitivity of FCNC processes to family assignment reveals a distinctive feature of 3-3-1 models: flavor observables measured at low energies can directly probe the structure of the gauge symmetry. The gauge sector, however, offers another way for testing the model. Mixing between the SM Z boson and the exotic introduces additional flavor-changing effects that complement the family discrimination studies.

Other works have also investigated how family discrimination affects FCNC in 3-3-1 models. In particular, Cárcamo, Martínez, and Ochoa [

108] performed one of the first systematic studies of this connection by analyzing the implications of different fermion embeddings for the neutral current structure. They showed that the choice of which quark family transforms as a triplet or anti-triplet under SU

leads to distinct patterns of non-universal

couplings, producing tree-level FCNCs whose size and sign depend sensitively on the family representation. In their analysis, the authors also investigated how family discrimination influences the FCNC effects in the decays of both

Z and

. By confronting the model predictions with precision electroweak data at the

Z pole, they demonstrated that

is strongly disfavored in the 331RHN, while configurations with heavier

remain viable. Among the three possible family assignments, they found that variant III leads to the strongest suppression of FCNC effects, making it the most phenomenologically favored configuration. These results, together with later studies such as Ref. [

74], established that FCNC observables can serve as a robust probe of family discrimination, tightly linking the gauge representation of quarks to measurable flavor phenomena.

5.2. Z- Mixing Effects

The mixing between

Z and

is a generic prediction of 3-3-1 models and gives rise to two physical neutral states,

and

. As a consequence, the SM-like boson

acquires flavor-changing couplings to quarks and contributes to neutral meson transitions. Following Ref. [

51], the effective Lagrangian was derived for

,

, and

transitions, considering the variant I of the model. The

Z contribution is proportional to

and depends on specific entries of the quark mixing matrices, as described in

Section 4. This makes the mixing angle

a directly testable parameter through FCNC observables.

In order to obtain quantitative bounds, the analysis required that the sum of contributions from h, , and Z respect the experimental uncertainty in the measured mass differences of neutral mesons. Since the relative size of each mediator’s contribution is not fixed by the model, two benchmark scenarios were considered. In the first case, h was assumed to account for of the allowed window, while in the second case only was attributed to h. For both scenarios, explicit solutions for the mixing matrices and were obtained, consistent with CKM unitarity. These textures were then used to evaluate the size of the effective couplings.

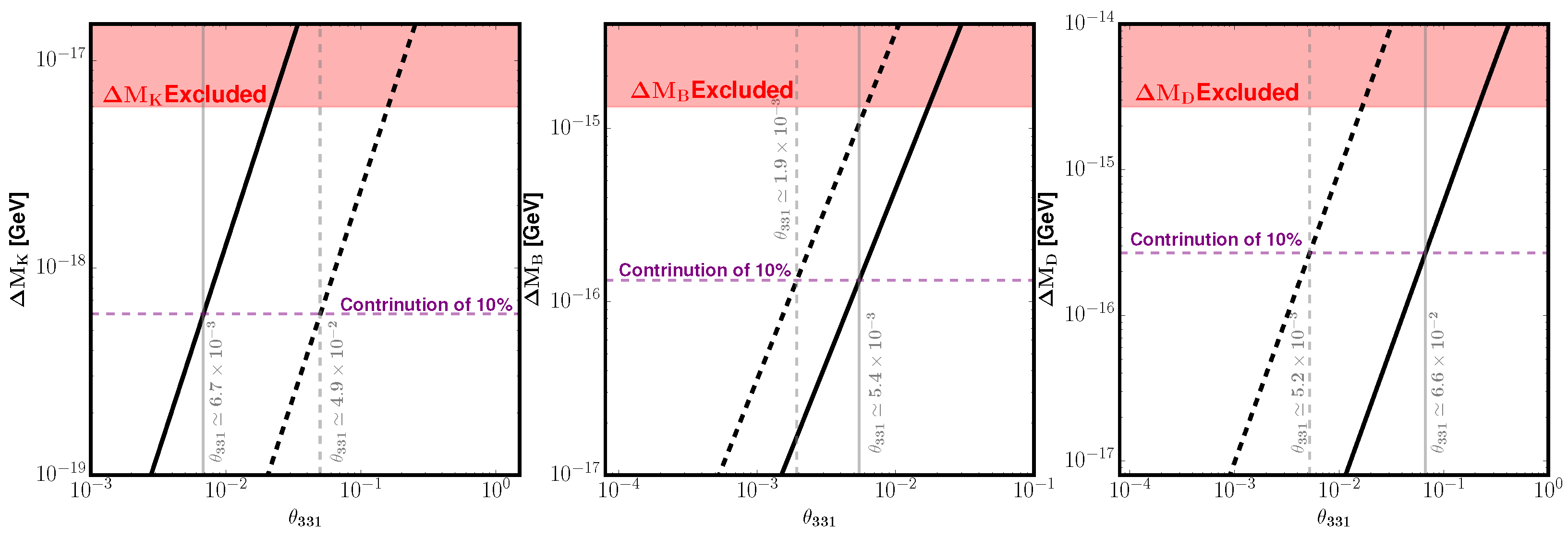

The

Figure 2 shows the result obtained in Ref. [

51]. The results show that the

K, and

meson transitions impose the most stringent bounds on

, requiring

. Such bounds are close to the previous ones found in the literature, see Refs. [

71,

72]. In both benchmark cases, the predicted contributions of

remain within experimental uncertainties, while they agree with the top quark decays constraint [

97].

A complementary study of

Z–

mixing effects in 3-3-1 models was carried out in Ref. [

70]. In that work, the authors revisited the general structure of the neutral gauge boson sector for arbitrary values of the

parameter and for different fermion representations. They demonstrated that, although

is typically of order

, the induced flavor-changing couplings of the SM-like boson

can produce non-negligible effects in flavor observables sensitive to axial-vector currents, such as

and

, while remaining negligible in

transitions. The analysis also clarified that the sign of

and the pattern of interference between

Z- and

-mediated amplitudes depend crucially on the choice of fermion representations and on the parameter

, highlighting the phenomenological differences of 3-3-1 variants. Furthermore, by correlating flavor-changing and electroweak precision observables, they showed that precision measurements of

and rare meson decays could together discriminate among the viable 3-3-1 constructions. This study established a solid theoretical framework to interpret

Z–

mixing as a key probe of the gauge and scalar sectors of 3-3-1 models.

The analyses discussed until now, family discrimination and Z- mixing, represent complementary probes of the gauge structure of 3-3-1 models. We now return to the scalar sector, examining in detail how the SM-like Higgs h, together with the heavier states H and A, contributes to neutral meson transitions. This discussion condenses the recent theoretical advances that culminated in the alignment limit framework.

5.3. FCNC and SM-like Higgs

The Yukawa interaction presented in Equation (

32) generates FCNC couplings involving neutral scalars once the scalar fields are rotated to their mass eigenstates. As discussed in

Section 2, the physical scalar spectrum consists of one massive pseudoscalar

A and three CP-even states:

,

H, and

h. The heaviest state,

, originates predominantly from the

component and effectively decouples from the low-energy theory when

. The remaining scalars—

A,

H, and

h—form a spectrum characteristic of the 2HDM, where their mixing is governed by the angles

and

introduced in

Section 2.

The contribution of these scalars to FCNC processes depends on both their masses and the scalar mixing configuration. To isolate the role of the SM-like Higgs

h and assess the validity of the alignment limit discussed in Ref. [

52], we adopt a benchmark scenario where the heavier scalars

A and

H are sufficiently massive to decouple from low-energy observables. Specifically, we set

ensuring that their contributions to meson transitions are negligible

10. The SM-like Higgs mass is fixed at its measured value,

Under these assumptions, the FCNC phenomenology is controlled by three ingredients: the Higgs mass , the scalar mixing angles and , and the quark mixing matrices . To systematically explore the relationship between these parameters, we examine three representative scenarios that span the range of possible quark mixing configurations consistent with the CKM factorization .

Each scenario represents a distinct limit of the quark mixing structure and probes different combinations of neutral meson systems:

Scenario (i) (, ): FCNC processes are confined to the up-quark sector, with only D- mixing providing constraints. This represents the least restrictive case.

Scenario (ii) (, ): FCNC processes occur exclusively in the down-quark sector, being constrained by K, , and transitions. The precision measurement of mixing makes this the most restrictive scenario.

Scenario (iii) (generic ): A mixed configuration where both up- and down-quark sectors contribute to FCNC, representing an arbitrary intermediate regime.

For each scenario, we analyze how the scalar mixing parameters

and

are constrained by requiring that the Higgs-mediated contribution

, Equation (

46), remains within experimental bounds. The alignment condition

emerges naturally as the parameter configuration that minimizes these contributions.

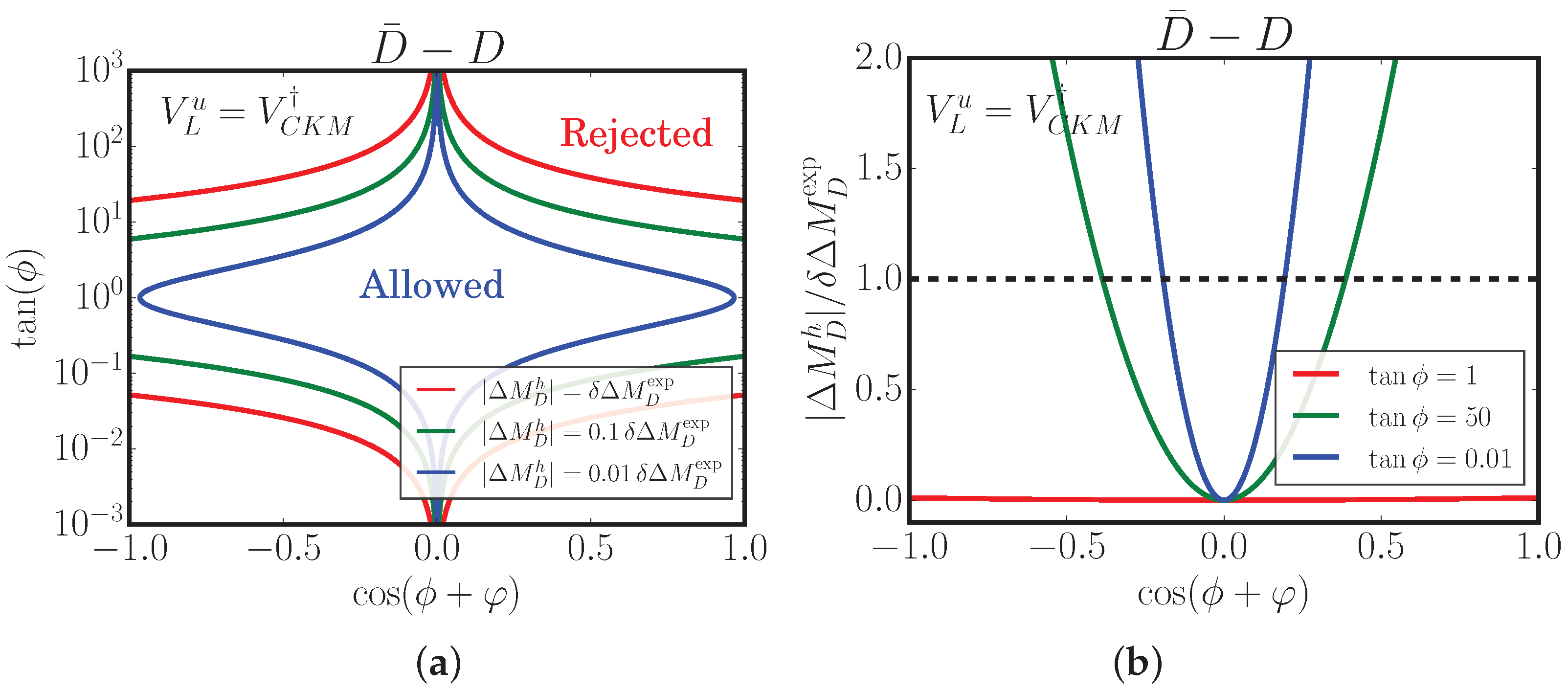

Scenario (i): Consider the scenario in which . For this choice of quark mixing, the contribution of h to the mass differences of K, , and mesons is exactly zero, so the mass difference becomes the only relevant quantity. On the other hand, the relative uncertainty of the measurement of the D- transition is the largest among mesons. This configuration consequently produces the weakest possible constraints over the scalar mixing parameters and , establishing it as the most phenomenologically flexible scenario for 3-3-1 model building.

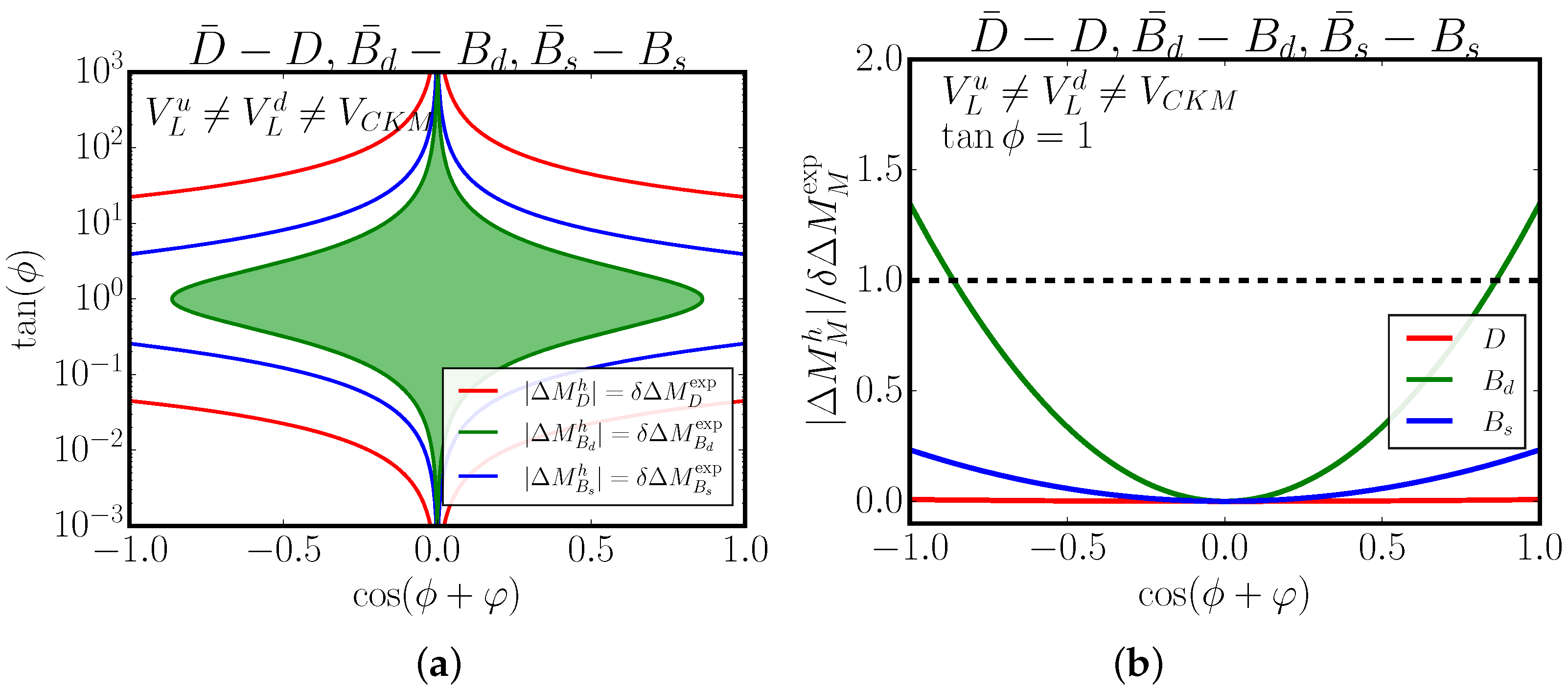

In

Figure 3a, we present the parameter space dependence of the Higgs-mediated contribution

in the

–

plane. The exclusion regions are demarcated by three contours: red (for

), green (for

), and blue (for

). Regions interior to the curves are experimentally allowed, while exterior regions are excluded. Notably, for

(red curve), no alignment limit constraints arise for

or

. Tightened bounds emerge when restricting the Higgs contribution to

or

of the total experimental uncertainty (green and blue curves, respectively).

In

Figure 3b, we analyze the

dependence across the

–

parameter space. Three benchmark scenarios are shown:

(red),

(green), and

(blue). The distinct trajectories of these curves illustrate how variations in

reshape the allowed regions, particularly at extreme values of

. This behavior reveals the interplay between quark rotation parameterizations (

) and scalar alignment conditions in determining viable 3-3-1 model parameter spaces.

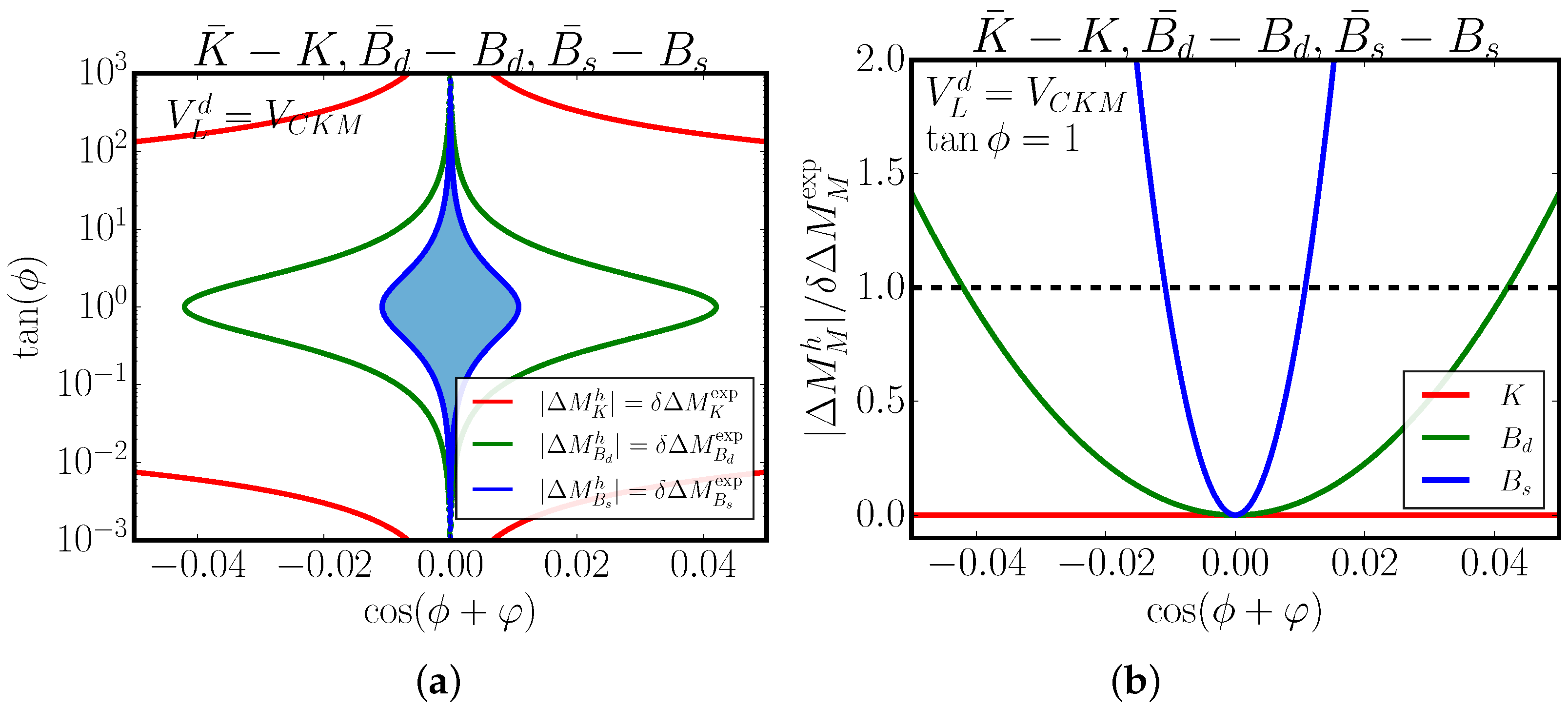

Scenario (ii): Consider the scenario in which . For this choice of quark mixing, the contribution of h to the mass differences of D mesons is exactly zero; then, there are FCNC contributions to K, , and meson transitions. In opposition to Scenario (i), the relative uncertainty of the measurement of the - transition is the smallest among mesons. This configuration consequently produces another possible constraint over the scalar mixing parameters and , establishing it as a more phenomenologically restrictive scenario for 3-3-1 model building.

In

Figure 4a, we analyze the parameter space dependence of the Higgs-mediated contribution

in the

–

plane. Exclusion regions are derived for three meson systems:

K (red curve,

),

(green curve,

), and

(blue curve,

). The combined constraints from all three systems yield the final allowed region (blue contour), dominated by the stringent

transition bounds, which restrict

. In contrast,

K and

systems permit significantly broader ranges of

.

In

Figure 4b, we fix

to isolate the

–

parameter space for individual meson systems. Contribution profiles are shown for

K (red),

(green), and

(blue) mesons, with curves representing their respective relative contributions to meson transitions experimental bounds.

Scenario (iii): Now, we turn our attention to an intermediate case, with a less trivial factorization of the CKM matrix. This scenario has non-negligible contributions to three neutral meson–antimeson transitions,

D,

, and

. However, this choice of parameterization suppresses the

K-

transition. We propose the following quark mixing matrices:

and

and this configuration produces intermediate constraints over the scalar mixing parameters

and

.

In

Figure 5a, we analyze the parameter space dependence of the Higgs-mediated contribution

in the

–

plane. Exclusion regions are derived for three meson systems:

D (red curve,

),

(green curve,

), and

(blue curve,

). The combined constraints from all three systems yield the final allowed region (green contour), dominated by the stringent

transition bounds, which restrict

. In contrast,

D and

systems permit significantly broader ranges of

.

In

Figure 5b, we fix

to isolate the

–

parameter space for individual meson systems. Contribution profiles are shown for

D (red),

(green), and

(blue) mesons, with curves representing their respective relative contributions to meson transitions’ experimental bounds.

The three scenarios analyzed above reveal how the alignment condition and the choice of quark mixing parameterization jointly determine the parameter space allowed by the scalar-mediated FCNC. The constraints range from remarkably weak (Scenario i) to extremely stringent (Scenario ii), with intermediate cases (Scenario iii) exhibiting sensitivity to multiple meson systems simultaneously.

Having established the scalar sector constraints, we now examine how these same quark mixing configurations affect the bounds on the gauge boson mass. As we will see, the pattern observed in the scalar analysis—with Scenario (i) yielding the weakest bounds and Scenario (ii) the strongest—persists in the gauge sector, though the relative magnitudes of the constraints differ significantly.

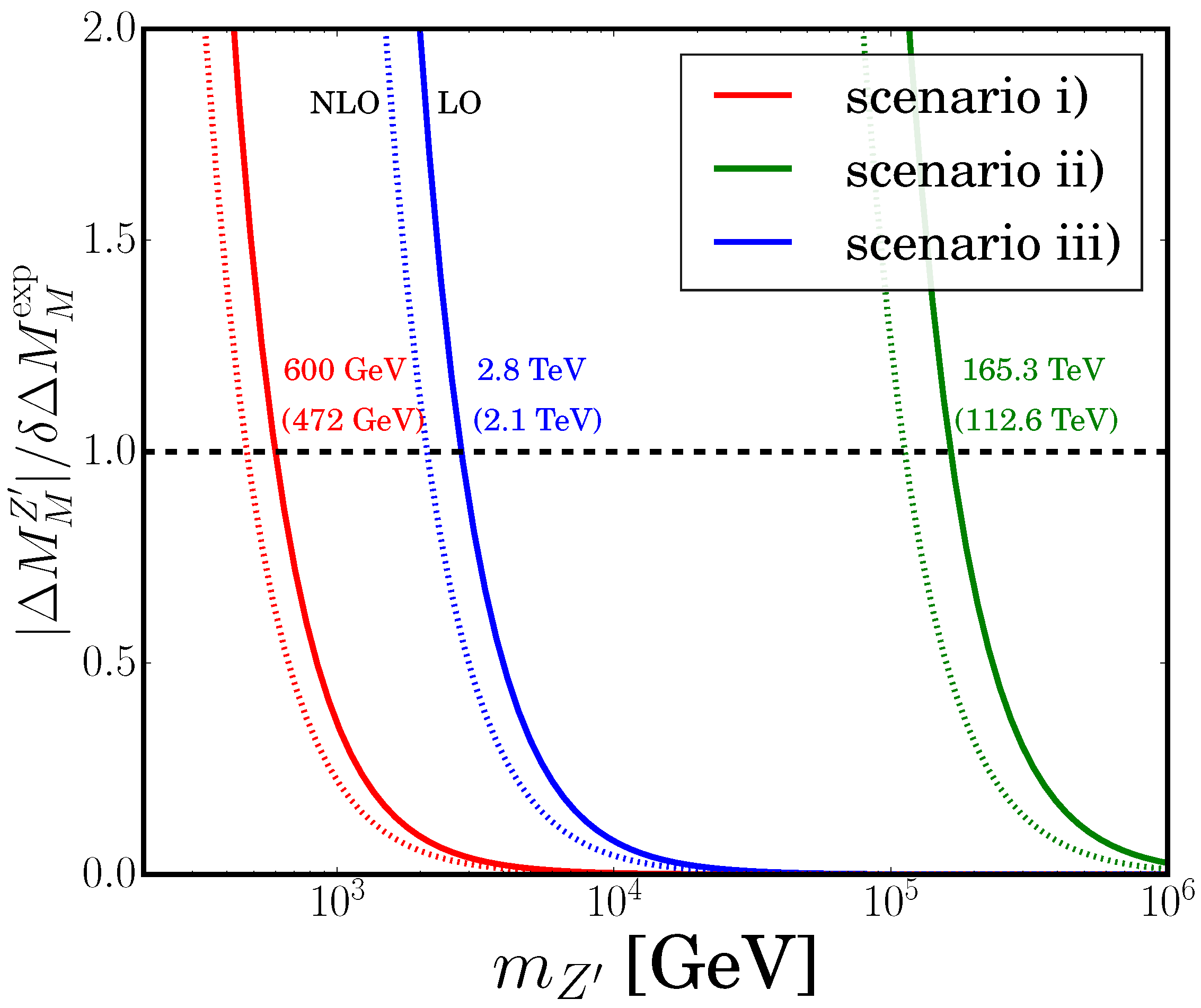

5.4. Mass Estimation Using Meson Transition Bounds

After describing the scalar sector contribution to meson transition parameters, it is time for the

boson. The gauge sector of the model is composed of the standard gauge bosons plus

, two new charged gauge bosons

, and two non-Hermitian neutral gauge bosons

and

. For the development of this sector, we refer the reader to Ref. [

77]. Neglecting mixing among the standard neutral gauge bosons,

Z and

, the FCNC processes get mediated by the neutral scalars and

. The interactions of

with the quarks that provide FCNC are given by Equations (

44) and (

45), and the induced mass differences are given by Equation (

49). We work in the variant I, setting

, to analyze the three mixing scenarios (i), (ii), and (iii) defined in

Section 4. Our results, displayed in

Figure 6, map the experimental bounds on the

mass (

) derived from meson transition data in

Table 2 for leading order (LO) represented as full lines and next-to-leading order (NLO) represented as dotted lines.

Table 3 summarizes these results. They highlight how CKM parameterization choices in 3-3-1 models critically modulate FCNC visibility, thereby reshaping

mass limits.