Abstract

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are widely recognized to exhibit jet-like emission structures, though previous studies often assumed isotropic emission due to observational constraints. This assumption limited our understanding of the intrinsic properties of GRBs. Here, we analyze 40 GRBs with observed X-ray plateaus and jet features, all with measured redshifts. By applying jet corrections to prompt and plateau-phase quantities, we probe their intrinsic behavior. We find that the jet-corrected prompt emission energy () depends less strongly on the jet-corrected X-ray luminosity at the end of the plateau (). An anti-correlation is also observed between the jet opening angle () and the rest frame peak energy (): for ISM and for wind environments, indicating that more collimated jets yield higher peak energies. After jet correction, the - correlation and the three-parameter --, -- and -- relations are generally weakened. Among these, the first three remain relatively stable, suggesting they reflect intrinsic GRB physics, whereas the -- relation weakens significantly, implying it may be an artifact of the isotropic assumption. We also identify a new three-parameter correlation: , .

1. Introduction

Gamma-ray bursts (GRBs) are high-energy explosive phenomena in the Universe [1,2]. The isotropic energy () of the prompt emission of GRBs is between and erg [3]. The spectra of GRBs are typically nonthermal and can usually be fitted by an empirical smoothly jointed broken power-law function, namely the so-called Band functio [1]. Traditionally, GRBs are directly classified as long-duration bursts (LGRBs, with s, typically 20–30 s) and short-duration bursts (SGRBs, with s, typically s) on the basis of the bimodal distribution of durations observed by the BATSE instrument [4,5]. A large number of observational evidences of the association between some LGRBs and broad-line Ic supernovae (Ic-BL) support that some LGRBs originated from the core collapse of massive stars [6,7,8,9,10]. However, the association between the gravitational wave GW 170817 and GRB 170817A confirmed that at least some of the SGRBs originated from the merging of binary neutron stars [11]. Recent observations have revealed that several LGRBs, including GRB 211211A and GRB 230307A, are associated with kilonovae from compact object mergers [12,13,14,15,16], while SGRB 200826A is associated with supernovae [17,18,19,20]. Meanwhile, observations also show that some LGRBs lack associated supernova detections [21]. This suggests that the alone is insufficient to distinguish GRBs based on their progenitor systems.

Observationally, it is recognized that GRBs contain two phenomenological emission phases, namely the prompt gamma-ray emission and the long-duration, multi-band afterglow emission. The widely accepted theoretical model explaining GRB emission is the fireball shock model [22,23]. This model posits that the prompt emission arises from internal shocks caused by collisions within the fireball’s ejecta. Conversely, the afterglow emission is thought to be produced by external shocks resulting from the interaction of the fireball’s ejecta with the interstellar medium [24,25,26,27]. Zhang et al. [28] proposed a canonical X-ray afterglow light curve with five phases, including a steep decay component, a shallow decay component (so-called plateau phase), a normal decay component, a post-jet break component, and X-ray flares. The shallow decay phase is commonly regarded as involving some extra energy injection that might result from the continuous energy release of a long-lasting central engine [29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37]. Surprisingly, it was found that there exists a specific kind of shallow decay, namely the so-called “internal plateau”, which is followed by a period of extremely steep decay (the decay index is usually less than −3) after the shallow decay phase ends. One commonly accepted explanation is that the “internal plateau” results from the continuous energy supply by a “super-massive” neutron star (NS). Eventually, under the action of spinning down or the fall-back accretion, the NS will collapse into a black hole (BH), causing the sudden shutdown of the central engine [38,39,40].

Several significant correlations have been found for GRBs with the X-ray afterglow plateau phase features. Dainotti et al. [41] firstly found an anti-correlation between the end time of the X-ray plateau phase in the rest frame () and the corresponding luminosity at the moment (), i.e., (L-T relation) [42]. Subsequently, they linked the plateau phase emission to the prompt emission and discovered a tight correlation between and the mean luminosity of the prompt emission (), given by [43]. Xu & Huang [44] further studied the correlations among multiple parameters, including , and , and found a very tighter three-parameter correlation, i.e., (L-T-E relation). By replacing in the L-T-E relation with the peak luminosity () of the prompt emission, Dainotti et al. [45] similarly discovered a tight three-parameter correlation, i.e., (L-T-L relation) [46]. Recently, these two three-parameter correlations have been increasingly confirmed by the large GRB samples [35,36,37,47,48,49]. Furthermore, considering the close relation between and the rest frame peak energy , Xu et al. [50] proposed a tight three-parameter correlation, i.e., (L-T-Ep relation) and demonstrated that the de-evolved L-T-Ep relation can be used as a standard candle to constrain cosmological parameters. Meanwhile, similar three-parameter L–T–E, L–T–L, and L-T-Ep correlations in the optical afterglow plateau phase have also been found, indicating that the X-ray and optical plateau phases may be dominated by the prompt emission, and they have the same physical origin [51,52].

It is generally assumed that the GRB emission is isotropic. However, some achromatic temporal break features observed in the multi-band afterglows indicate that GRBs might be collimated into a narrow jet [53,54]. Theoretical studies have shown that in the fireball shock model, the burst ejecta moves at relativistic speed and forms a conical jet with a half-opening angle . As the Lorentz factor () of the ejecta decreases below the inverse of (), a steepening break—known as the jet break—is predicted in the afterglow light curve. The time corresponding to the break is referred to as the jet break time () [55]. Consequently, more and more break features observed in the late-time afterglow light curves confirms this scenario, supporting the view that at least some GRBs are collimated into the narrow jets rather than isotropic [53,54].

Previous statistical studies of GRBs have largely relied on the isotropic assumption, owing to the limited number of jet opening angle measurements. However, with the growing detection of GRB jet breaks, the number of GRBs with known jet opening angles has increased substantially. This progress allows for a more thorough investigation of the intrinsic statistical properties of GRBs and a deeper exploration of jet-related effects. In this work, we compile a sample of GRBs that exhibit both X-ray plateau phases and jet features, where a jet feature is defined as an achromatic temporal break in the afterglow, utilized to infer the jet opening angle. Using this sample, we re-examine the properties and correlations between the prompt emission and the X-ray afterglow plateau emission, taking jet effects into account. In Section 2, we describe the sample selection and data analysis. In Section 3, we outline the statistical analysis methods. In Section 4, we present the results. The discussions and conclusions are shown in Section 5. The cosmological constants in this paper are km s−1 Mpc−1, , and . The symbolic notation of is adopted.

2. Sample Selection and Analysis

In order to investigate the relationship between prompt emission and X-ray afterglow plateau emission of GRBs with jet structures, and to understand the intrinsic physical mechanisms of GRBs, we compile a GRB sample showing both X-ray plateau and jet break features. The sample consists of a total of 40 GRBs, where two SGRBs 090426 and 051221A are included. The datasets are mainly taken from Deng et al. [37] and Zhao et al. [56]. We obtain the parameters , rest frame jet break time , the opening angles in homogeneous interstellar medium (ISM), as well as Wind medium (Wind) ( and ), , , and , after which we show the values in Table 1. In addition, we also collect the values of these GRBs from the published literature.

Table 1.

The rest frame parameters of GRBs without jet correction.

However, the values of two bursts (GRB 070721B and GRB 180115A) are not collected; we use the spectral parameters to derive their values. The can be derived by [59]

where is the luminosity distance, is the peak flux, and k is the k-correction factor. The is defined as

where is the matter density, is the dark energy density, = 1 , z is the redshift, c is the speed of light, and is the current Hubble constant. The k is defined as [60]

where and are the energy bands observed by the detector, while is the photon spectrum [61] and is modeled using a CPL spectrum. The CPL function is defined as

where is the low-energy photon index, and is fixed at 100 keV. The errors for the values are calculated using error propagation formulas.

Using the opening angles of GRBs in our sample, we calculate the jet-corrected prompt emission energy (), peak luminosity (), and X-ray luminosity () at the plateau end time, where , and . It should be noted that this formula relies on the assumption of uniform top-hat jets and employs the small-angle approximation. These jet-corrected parameters are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

Jet-corrected parameters of GRBs in the rest frame.

3. Methodology

We mainly focus on the statistical correlations of the physical parameters of the prompt emission and X-ray afterglow plateau emission. Here, we adopt the general form previously used by many authors to extensively explore the two-parameter and three-parameter correlations, namely

where y is the target variable, and are the input variables, and are the best-fit parameters to be determined in the model, with a being the intercept and b, c being the power-law indices of and , respectively. During the process of determining the parameters, we use a joint likelihood function widely employed in multi-parameter fitting processes (taking the three-parameter problem as an example), given by [62]

where n represents the index corresponding to each GRB, , , and are the errors associated with , , and y, respectively, and represents the intrinsic scattering parameter caused by some hidden variables. For the joint likelihood function of the two-parameter, one simply removes the term related to in Equation (6). Subsequently, we employ the Markov Chain–Monte Carlo (MCMC) method to estimate the best-fit values of parameters a, b, and c. On each Markov Chain, we generate samples based on Equation (6). All statistical analysis methods mentioned above are implemented using the Python 3.9 software tools [63].

4. Results

4.1. Distributions of Physical Parameters for Both Prompt Emission and X-Ray Plateau Emission

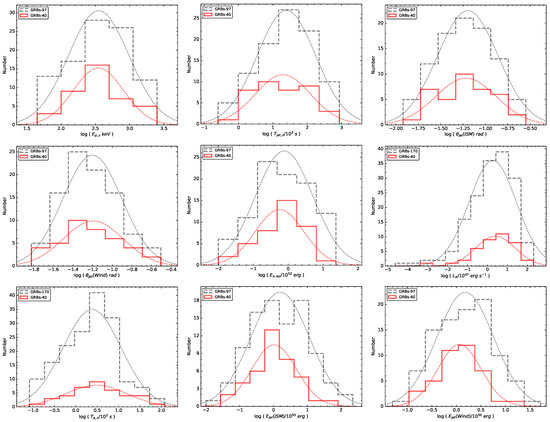

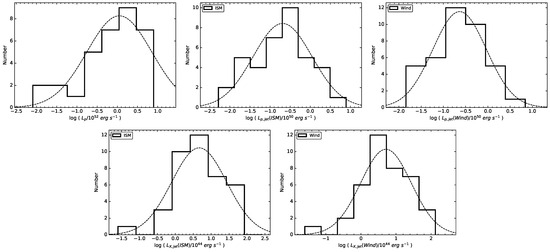

We first analyze the distributions of , , , , , , , and . The results are shown in Figure 1. From this figure, we can find that these parameters are basically log-normal distributions. To give a quantitative result, we make a Gaussian fitting. From the best fitting, we obtain the median values and the dispersions of these parameters in our sample are keV, s, rad, rad, erg, s, erg s−1, erg, and erg, respectively. The results are shown in Table 3.

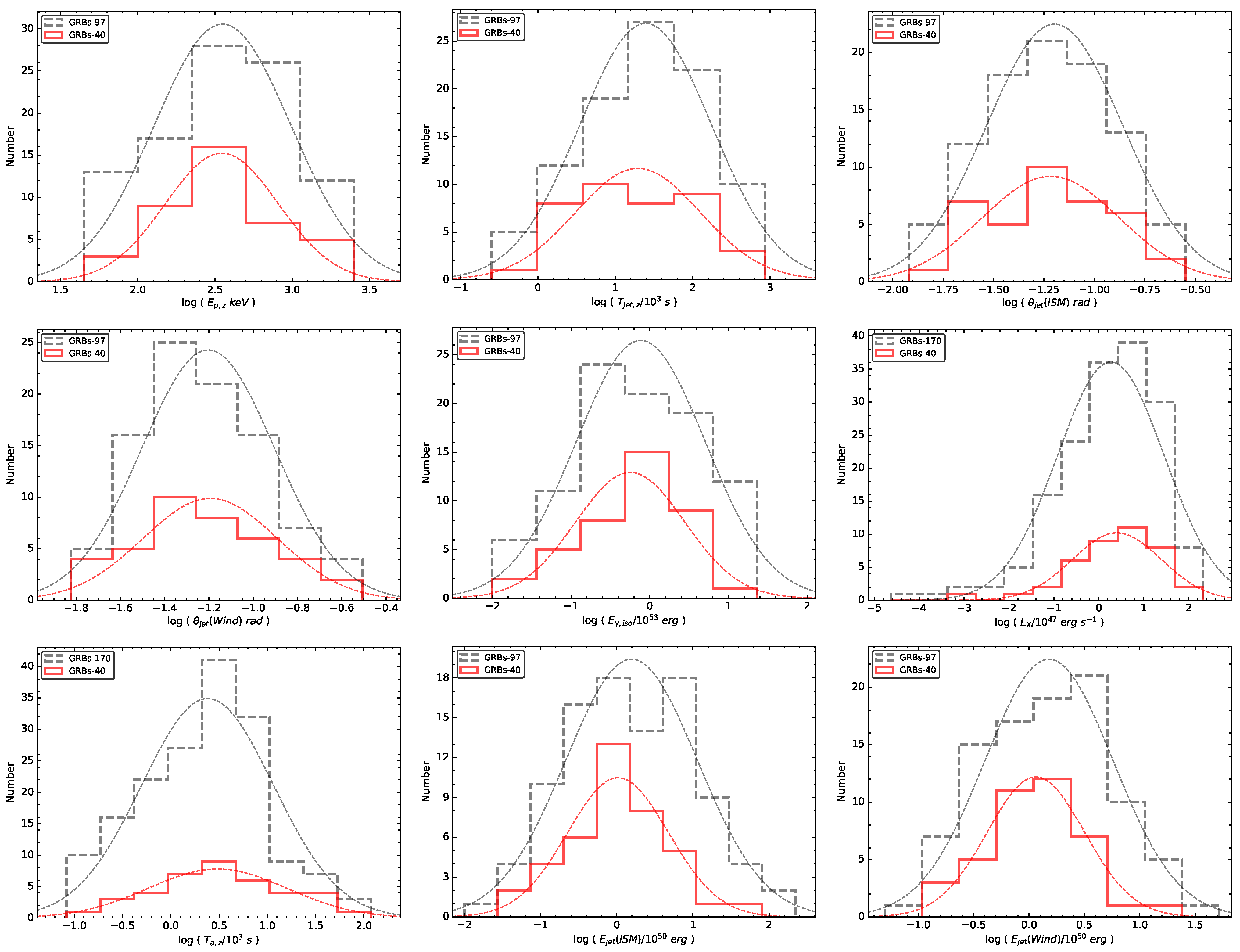

Figure 1.

Distributions of , and . The red solid lines represent 40 GRBs in our sample, and the dashed lines represent 97 GRBs in Zhao et al. [56] and 170 GRBs in Deng et al. [37]. The dotted lines represent the best fitting.

Table 3.

Parameter distributions of GRBs with X-ray plateau emission and jet break features.

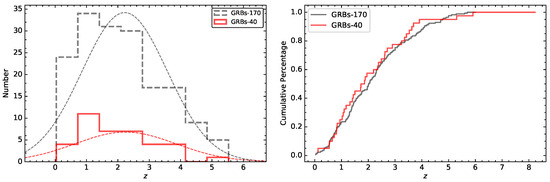

Due to the fact that our samples are mainly from Zhao et al. [56] and Deng et al. [37], it is necessary to determine whether there is a selection effect. We also analyze the same parameter distributions in Zhao et al. [56] and Deng et al. [37] and show in Figure 1. The median values and the dispersions of the corresponding parameters are keV, s, rad, rad, erg, s, erg s−1, erg, and erg, respectively, showing a high degree of similarity with our selected sample. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov (K-S) test is a powerful tool for determining whether there are significant differences in the two distributions. We perform the K-S tests for all parameters and present the results in Table 4. We can find that the distributions of our sample are similar to those from Zhao et al. [56] and Deng et al. [37], which indicate our sample have no significant selection effect. We further compare the redshift distribution of our sample with those of Deng et al. [37] and show them in Figure 2. We find that the median values of z for the two samples are 2.22 and 2.24, respectively, and the p-value of the K-S test is 0.89, indicating that there is basically no difference in the redshift distributions of the two samples.

Table 4.

K-S test results for our sample (40 GRBs) compared to the sample (170 GRBs) a in Deng et al. [37] and the sample (97 GRBs) b in Zhao et al. [56]. The superscripts a and b refer to the samples from Deng et al. and Zhao et al., respectively. The second column represents the test statistic for the K-S test, the third column represents the p-value of the K-S test, and the last column indicates whether the two samples originate from the same parent population.

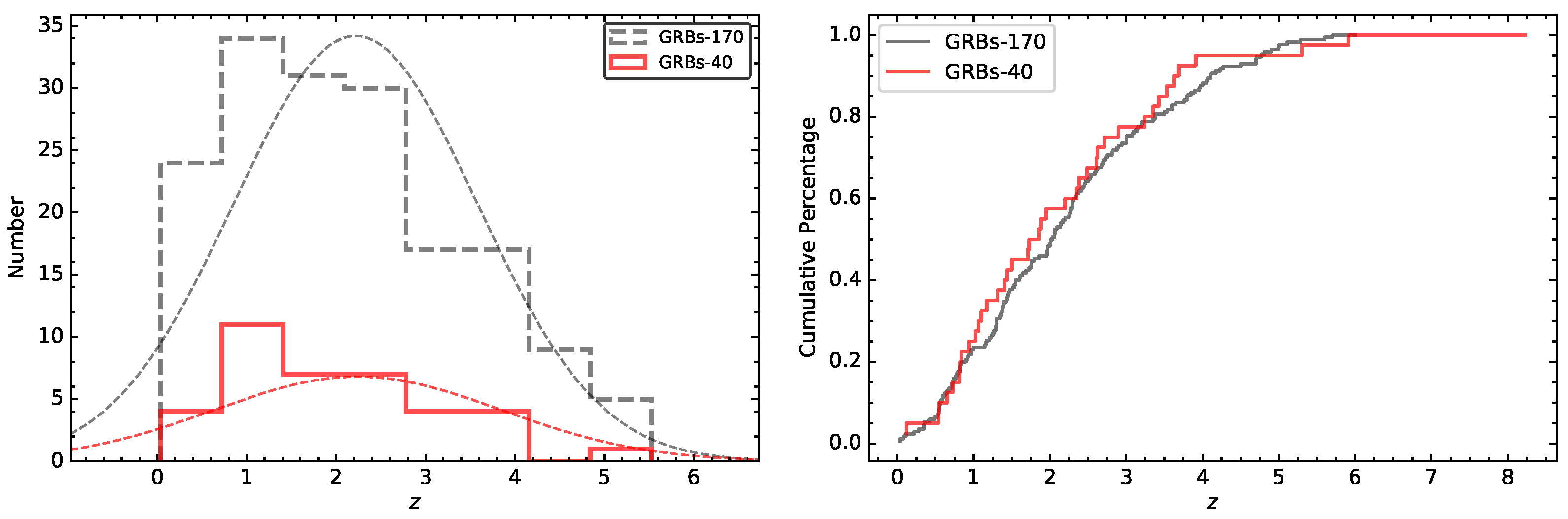

Figure 2.

Left panel: The redshift distributions of GRBs in Deng et al. [37] (dashed line) and in our sample (red line), where the mean values of two distributions are 2.22 and 2.24, respectively. Right panel: The cumulative redshift distribution curves obtained from the K-S test.

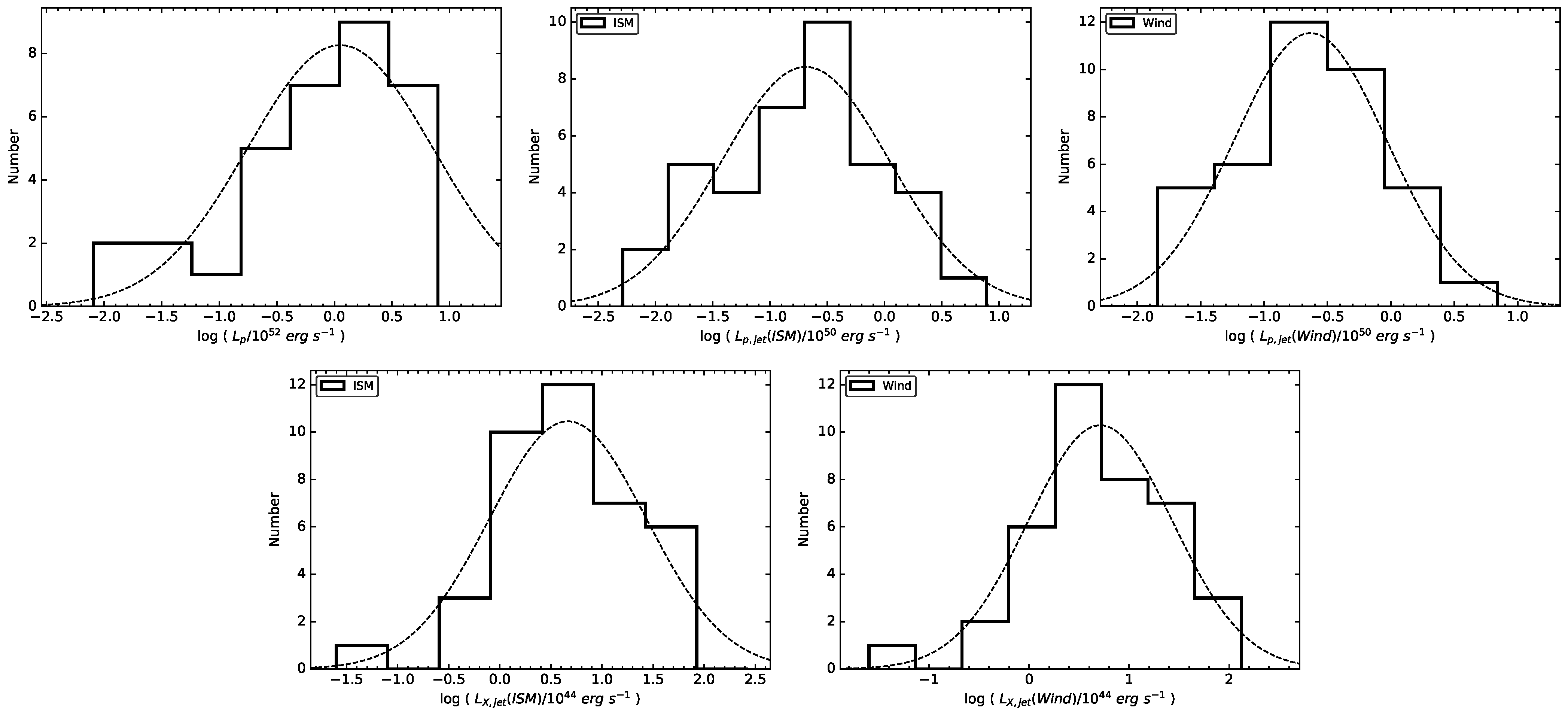

In addition, we also analyze the distributions of , , and , and present the results in Figure 3. Similarly, we fit the distributions using the logarithmic Gaussian function. The results show that the median values and the dispersions of , , , , and , are erg s−1, erg s−1, erg s−1, erg s−1, and erg s−1, respectively. The detailed results of all parameters are also listed in Table 3. We find that the jet-corrected emission energy and luminosity are more concentrated.

Figure 3.

Distributions of and . The dotted lines represent the best fitting.

4.2. Two-Parameter Correlations

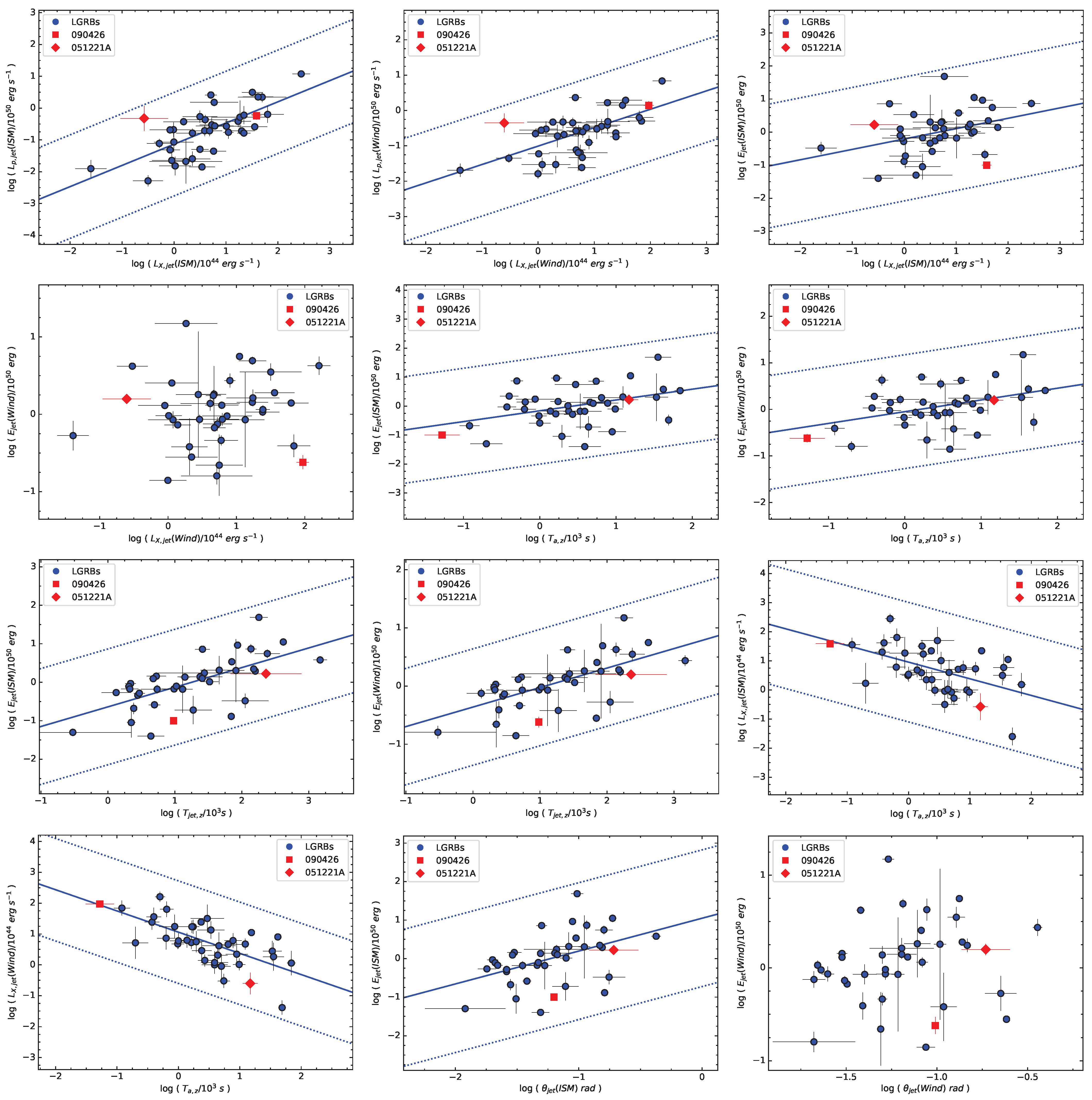

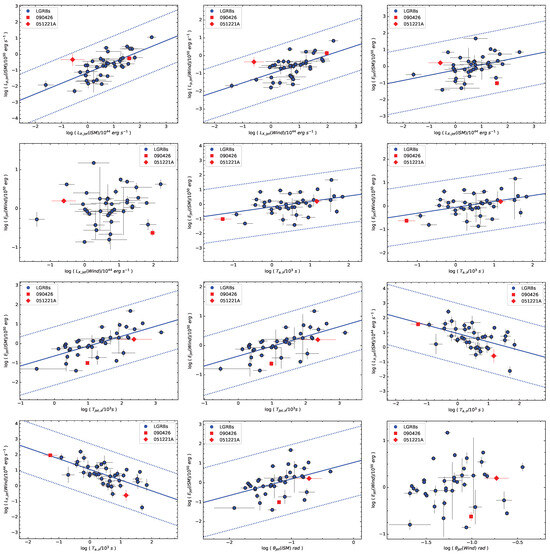

Using the MCMC method, we analyze the correlations among , , , , , , and . The results are shown in Figure 4 and Table 5. For comparison, we also analyze the relationships among various quantities without jet correction. The results are shown in Figure 5 and Table 6. It can be seen from the figures that still has a close dependence with . The best fit of the correlations in two different medium are and , where the Pearson correlation coefficients are and , respectively. This means that the greater the prompt emission energy of GRBs, the greater the peak luminosity, which is consistent with previous studies. Furthermore, we find that the relationship between and still exists. The best fits of correlations are and , with and , respectively. However, unexpectedly, the dependence between and is significantly weakened, which is inconsistent with the previous research results and might imply that the X-ray afterglow plateau emission of GRBs is mainly dominated by the prompt emission luminosity rather than the total emission energy.

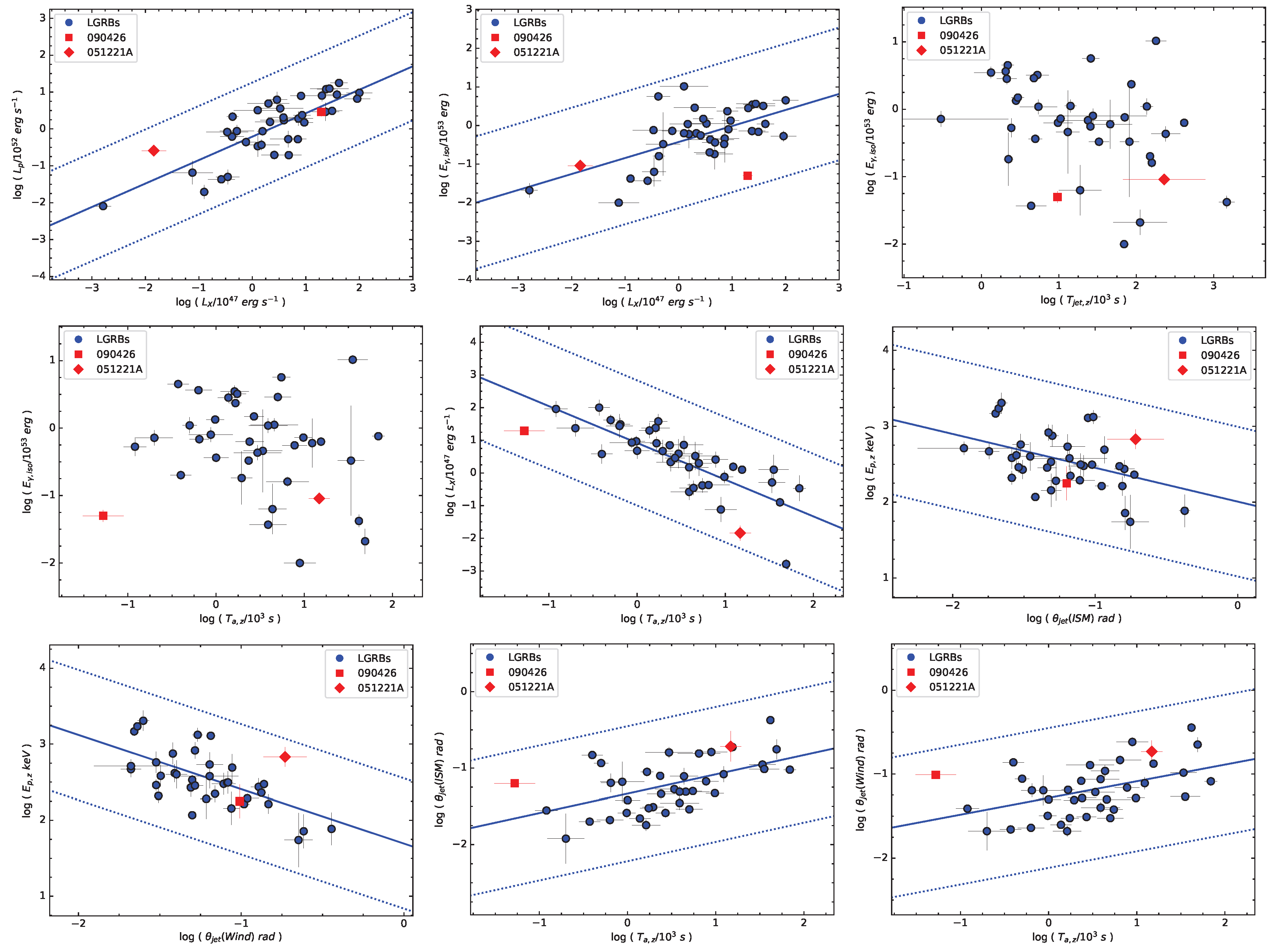

Figure 4.

Relationships between , , , , , , , , , and . The blue dots represent LGRBs, the blue solid lines represent the best-fit lines, and the blue dashed lines indicate confidence intervals. The red squares and diamonds indicate the positions of two SGRBs (GRB 090426 and GRB 051221A).

Table 5.

Two-parameter regression analysis results of jet-corrected GRBs in the rest frame, where r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, p denotes the chance probability, and denotes intrinsic scatter.

Figure 5.

Relationships between , and . The other symbols are the same as in Figure 4.

Table 6.

Two-parameter regression analysis results of GRBs without jet correction, where r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, p denotes the chance probability, and denotes intrinsic scatter.

It is known that there is a tight anti-correlation between and [42]. After considering the jet effect, we find that the L-T relation ( ) still exists, indicating that it is a real physical relation of GRBs. In addition, we explore the effect of opening angle and find that affects and , i.e., , and . These results suggest that the more collimated the GRB, the higher the detected peak energy, and this phenomenon is particularly obvious in the Wind case. We also find all the correlations have generally weakened after the jet correction. The two short bursts show no significant differences with the long bursts, indicating that they have the same radiation process.

4.3. Three-Parameter Correlations

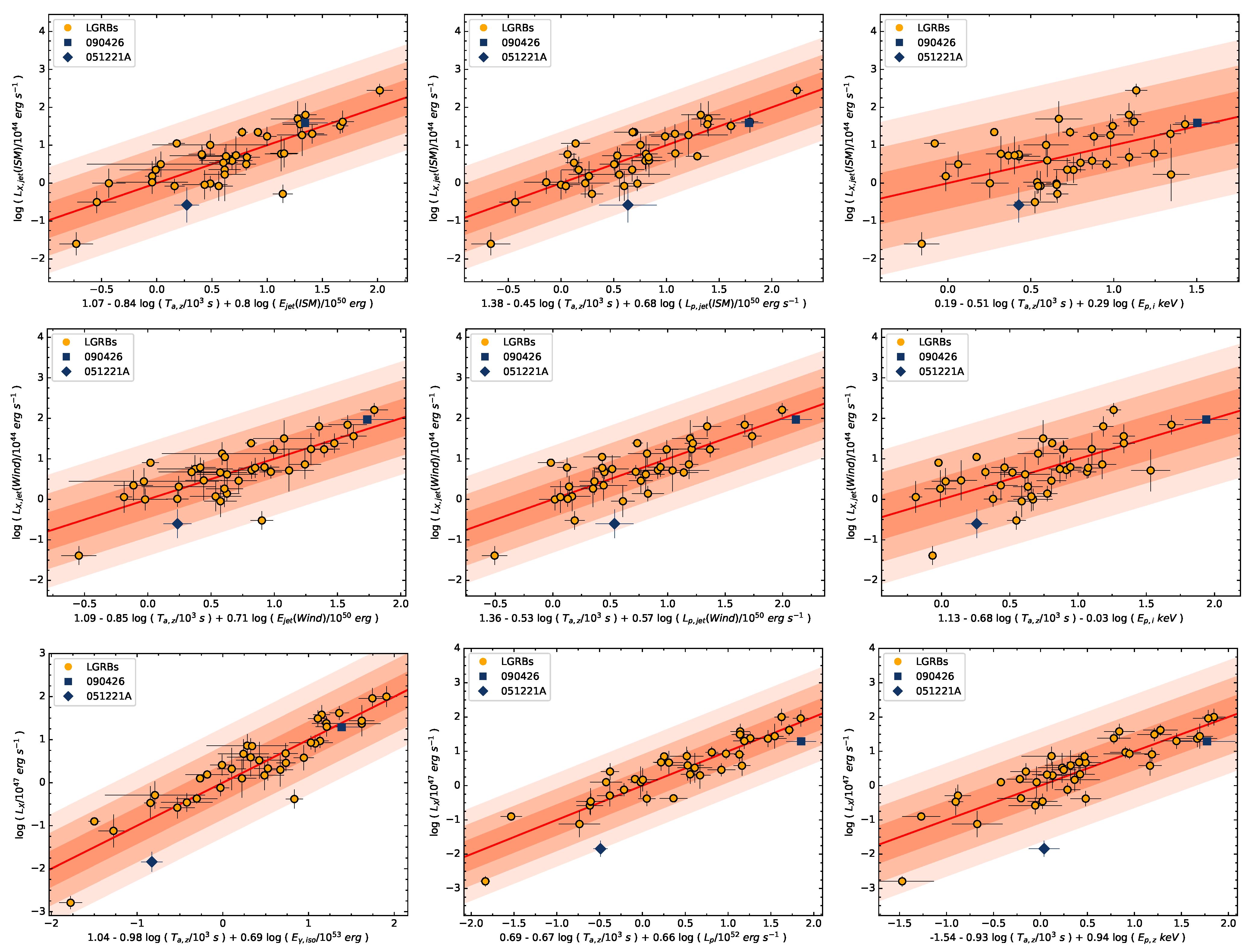

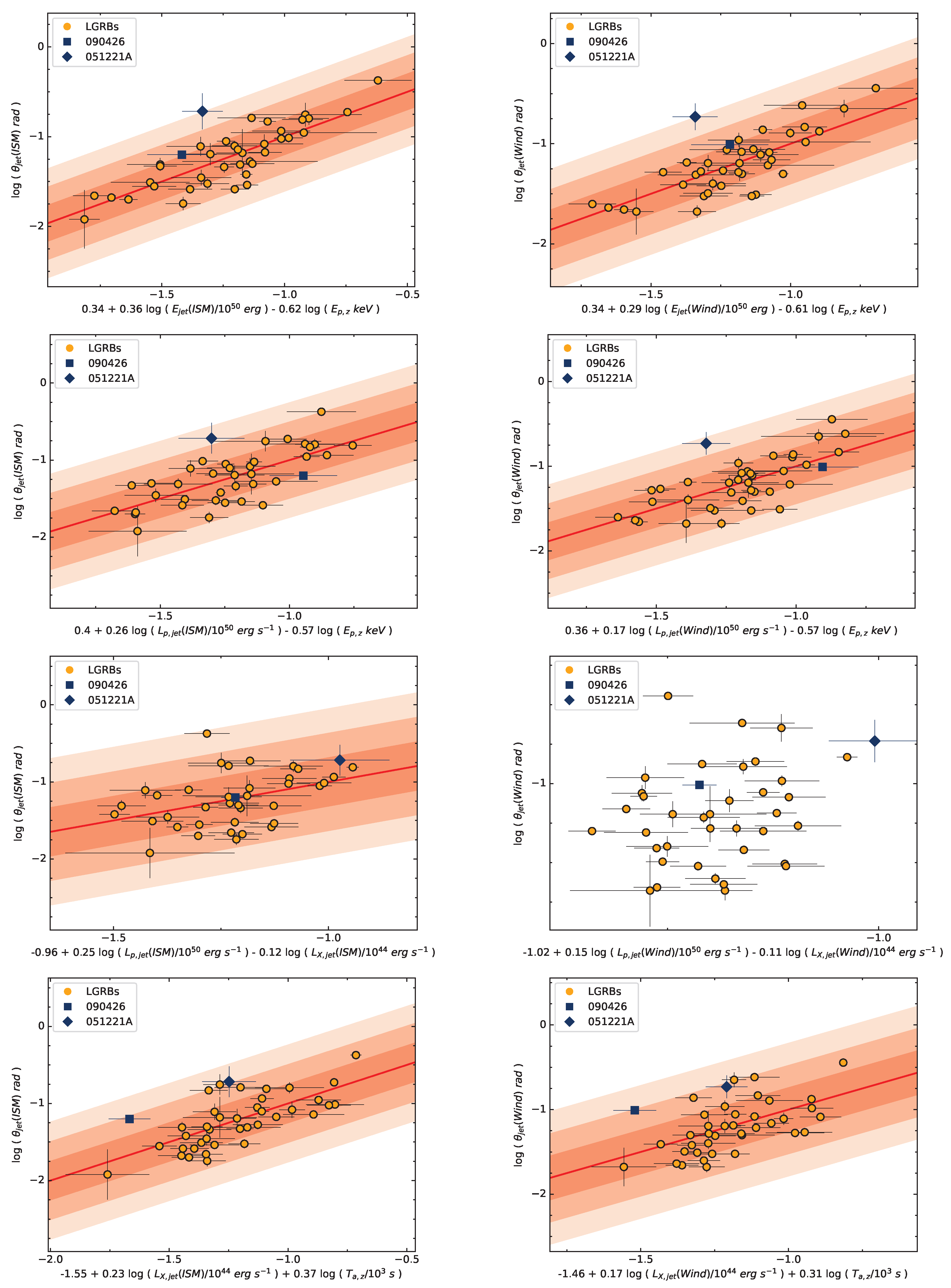

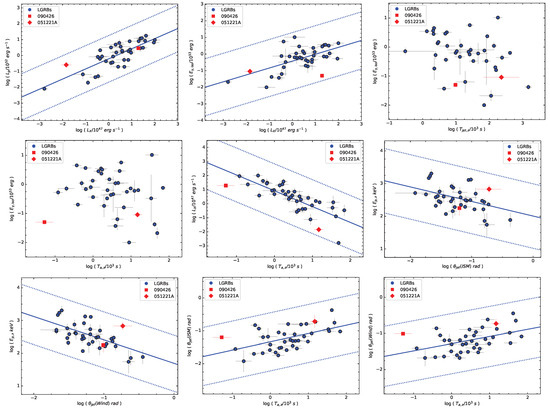

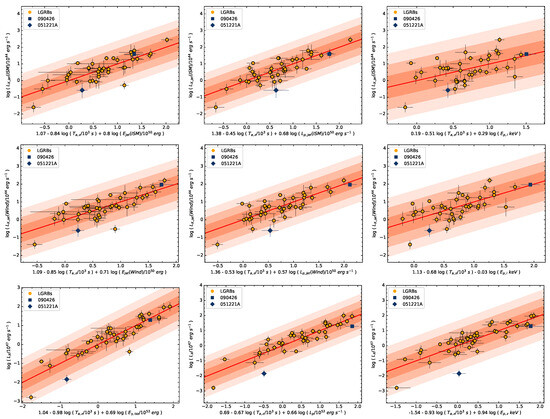

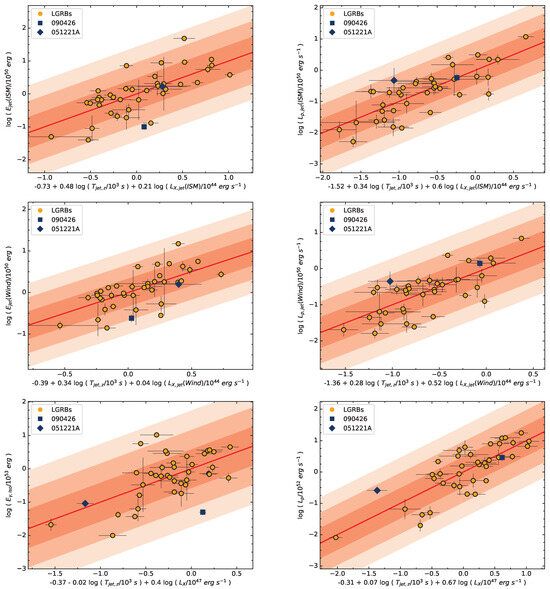

Previous studies have revealed that GRBs obey multiple three-parameter correlations linking X-ray afterglow plateaus to prompt emission, extending beyond the above known two-parameter relations. We further re-examine the jet-corrected L-T-E, L-T-L, and L-T-Ep relations and present the results in Figure 6. Similarly, the three-parameter correlations without jet correction are also shown in Figure 6 for comparison, with the MCMC fitting results for the L-T-E correlation provided in Supplementary Materials, Figure S1.

Figure 6.

Three-parameter correlations of GRBs. Left panel: The L-T-E relations with and without jet correction. Middle panel: The L-T-L relations with and without jet correction. Right panel: The L-T-Ep relations with and without jet correction. The yellow dots represent LGRBs, the red solid lines represent the best-fit lines, and the shaded regions indicate confidence intervals. The blue squares and diamonds indicate the positions of two SGRBs (GRB 090426 and GRB 051221A).

There is also a tight -- correlation. The best-fitting results in the ISM and Wind medium are

where and , the chance probabilities are both , and the intrinsic scatters are and , respectively.

The jet-corrected L-T-L correlation can be expressed as

with and , and , and .

The jet-corrected L-T-Ep relation in the ISM and Wind medium are

with and , and , and . These results are listed in Table 7.

Table 7.

Regression analysis results of the three-parameter L-T-L, L-T-Ep and L-T-E correlations of GRBs without and with jet correction, where r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, p denotes the chance probability, and denotes intrinsic scatter.

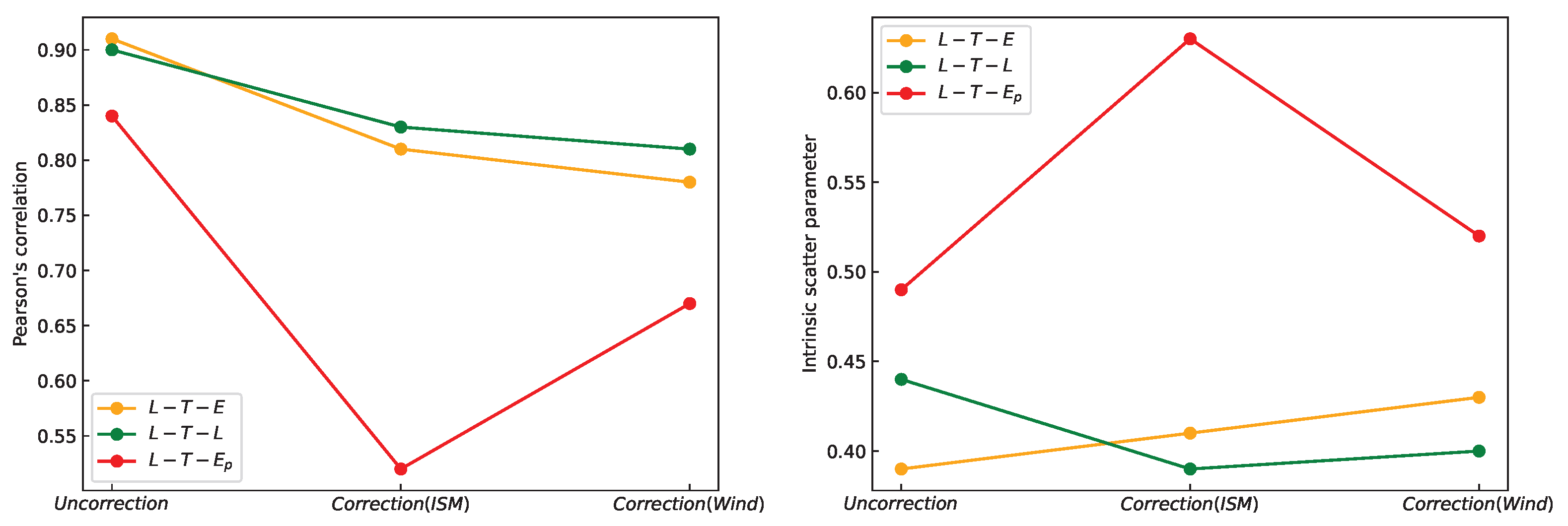

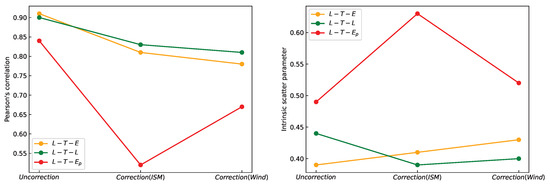

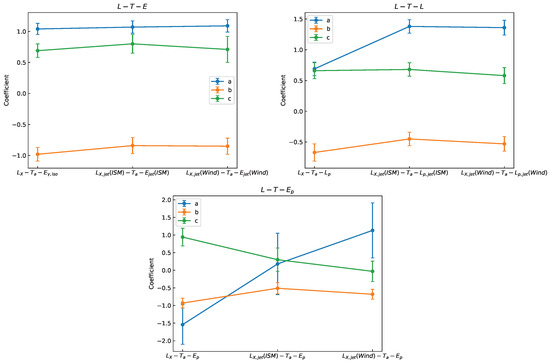

We find that the jet-corrected L-T-E and L-T-L relations are still very significant, and the results after the jet correction are basically consistent with those without jet correction, indicating these two three-parameter correlations are intrinsic and reflect the real physical process. However, the L-T-Ep relation has significantly weakened after jet correction. In order to intuitively display the changes in the L-T-E, L-T-L, and L-T-Ep relation before and after the jet correction, we present the changes in Pearson correlation coefficients, intrinsic scatters, and coefficients a, b, and c of these three-parameter relations in Figure 7 and Figure 8, respectively. It can be clearly seen from the figures that the L-T-Ep correlation after the jet correction has changed significantly and the correlation is significantly weakened.

Figure 7.

Changes in the Pearson correlation coefficients and intrinsic scatters of the L-T-E, L-T-L, and L-T-Ep correlations with and without jet correction.

Figure 8.

Changes in the coefficients a, b, and c in the L-T-E, L-T-L, and L-T-Ep correlations with and without jet correction.

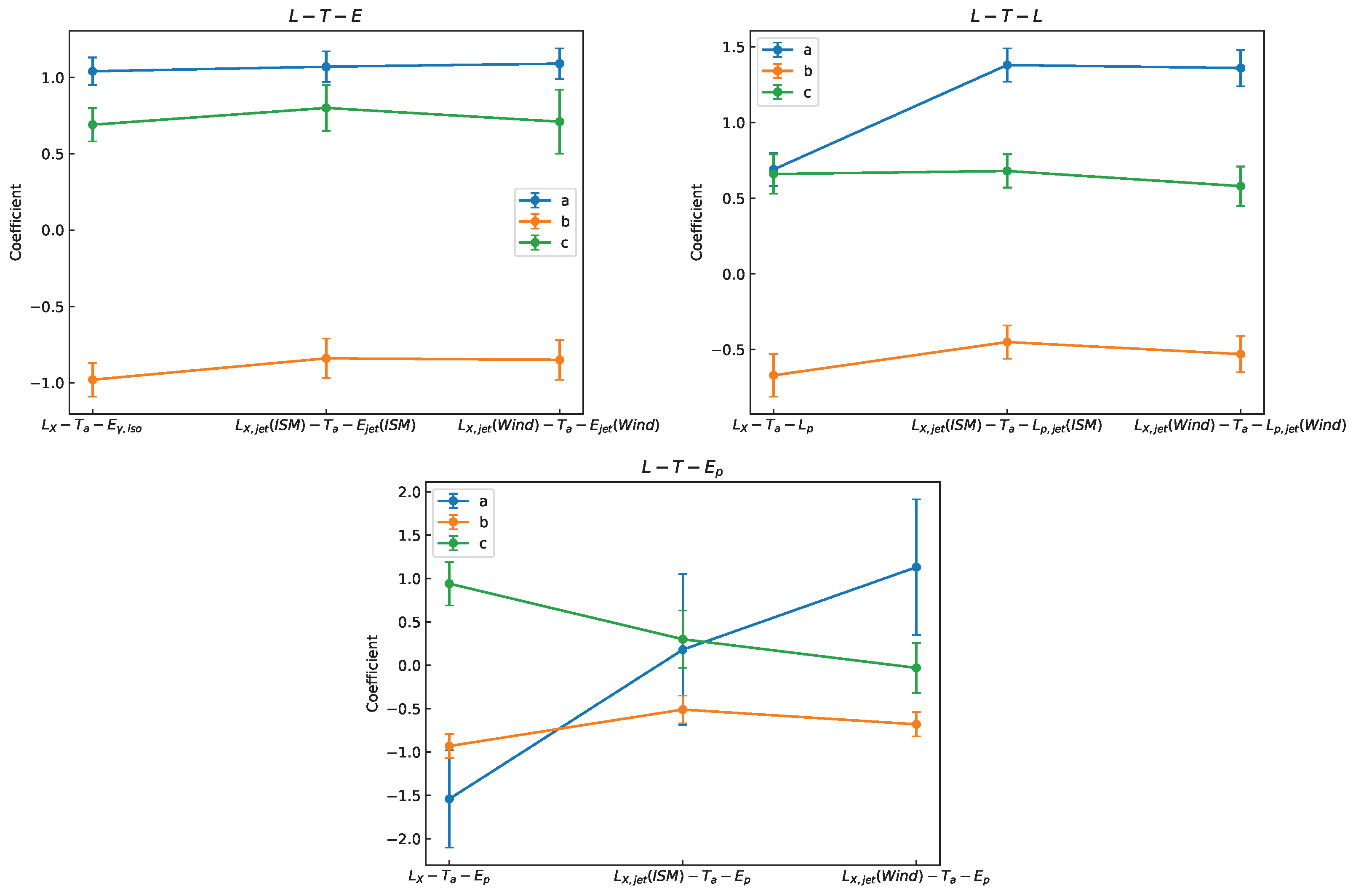

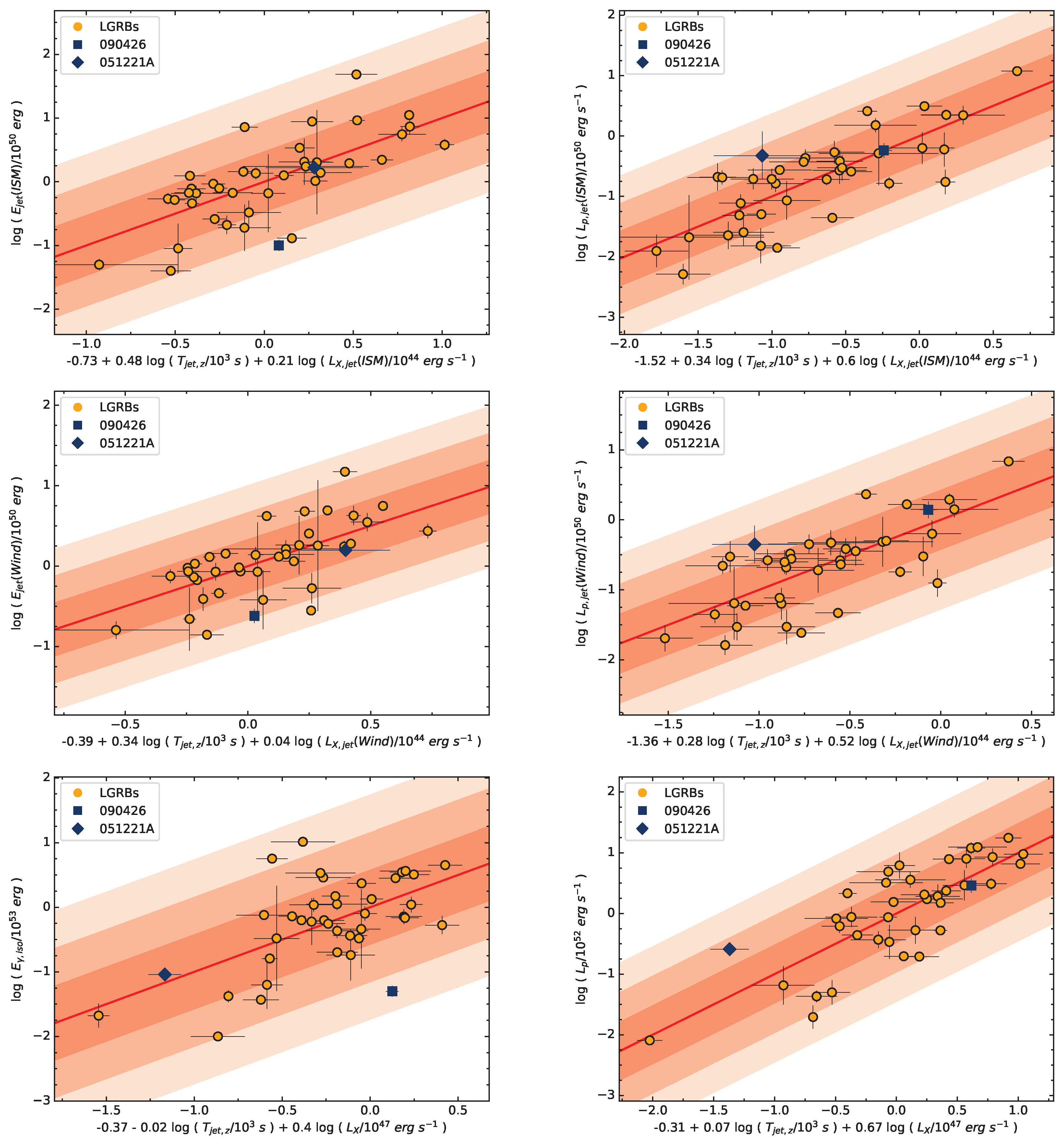

We replace in the three-parameter correlations above with , and we explore the and correlations as shown in Figure 9 and Table 8. The best-fitting results are

with and , and , and .

with and , and , and .

Figure 9.

Three-parameter correlations of GRBs. Left panel: and correlations. Right panel: and correlations. The symbols and notations are the same as in Figure 6.

Table 8.

Regression analysis results of the three-parameter E-Tjet-LX and L-Tjet-LX correlations of GRBs without and with jet correction, where r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, p denotes the chance probability, and denotes intrinsic scatter.

For comparison, we also present the and correlation (shown in Figure 9), which are not considered the jet effect, and express them as

with and , and , and . From the above results, we find that and correlations are significant, and after jet correction are more tight.

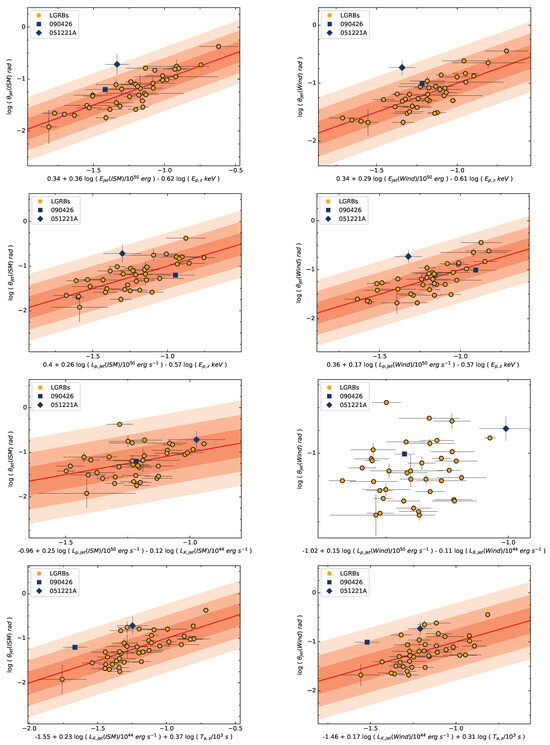

In addition, we also explore the other three-parameter correlations related to the jet opening angle and present the results in Figure 10 and Table 9. We find there are tight and correlations both in the ISM and Wind medium, i.e., with , with . with , with . This result indicate the jet opening angle strong depend on the prompt emission energy and intensity.

Figure 10.

Three-parameter correlations of GRBs associated with opening angle. These figures show --, --, --, and -- correlations. The symbols and notations are the same as in Figure 6.

Table 9.

Regression analysis results of three-parameter correlations with jet opening angle, where r denotes the Pearson correlation coefficient, p denotes the chance probability, and denotes intrinsic scatter.

5. Conclusions and Discussion

It is known that the X-ray afterglow plateau emission of GRBs are closely linked the prompt emission. However, due to the observational limitations of , the previous studies are based on a fundamental assumption that GRB emission are isotropic. In this work, we compile samples of 40 GRBs (38 LGRBs and 2 SGRBs) with both the X-ray plateau emission and jet break features, and analyze the statistical properties of the prompt emission and the X-ray plateau emission of GRBs after jet correction.

We firstly analyze the distributions of the jet-corrected prompt emission energy, peak luminosity, and X-ray plateau luminosity in the ISM and Wind interstellar medium, respectively, and find that these parameters are basically log-normal-distributed, and the median values of , , , , , and are erg, erg, erg s−1, erg s−1, erg s−1, and erg s−1, respectively. We also find that these quantities are more concentrated after jet correction.

After considering the jet effect, we find that is still correlated with , i.e., . However, the relation between and is significantly weakened, which is inconsistent with the previous results. This indicates that the X-ray plateau emission luminosity is dominated by the prompt emission luminosity rather than emission energy. We obtain the L-T correlation after jet correction, i.e., with , with , which means that this relation is indeed the physical relation of GRBs. We also find that strongly depends on , which reads , indicating that the more collimated the burst, the higher the detected peak energy. The observed disparity in the correlation exponents likely stems from how the distinct density profiles of the circumburst environments govern the jet’s dynamical evolution and emission geometry. In the Wind environment (), the jet decelerates rapidly, causing the observed emission to be dominated by the brighter, on-axis core. This results in a tighter, steeper correlation as the observed peak energy becomes more directly sensitive to the initial jet collimation. Conversely, in the constant-density ISM, the slower deceleration allows for a significant contribution from the dimmer, off-axis jet edges, which dilutes the correlation and leads to a shallower observed slope.

We conduct detailed analyses on the intrinsic three-parameter L-T-E, L-T-L, and L-T-Ep relations of GRBs after considering the jet effect, and we find that the tight L-T-E and L-T-L relation after jet correction still exists. The best-fitting results are , , and . This indicates that the L-T-E, L-T-L correlations reflect the physical nature. However, the L-T-Ep correlation is significantly weakened, which suggests that it was not an intrinsic physical relation, but rather a geometric artifact of the isotropic assumption. In this scenario, both the and the are subject to similar beaming-related selection effects. A narrower jet (smaller ) points more directly towards the observer, leading to higher detected peak energy due to relativistic beaming, while simultaneously increasing the apparent luminosity. This creates a spurious correlation that is significantly weakened when the true, jet-corrected energies and luminosities are considered. We also obtain the tight three parameter and correlations, which are ), , and ).

In addition, we explore the three-parameter correlations related to and find a tight three-parameter correlation, i.e., correlation, which reads , . The other three-parameter correlations , , and are also found. It is true that all these relations share the derived under consistent assumptions, which inherently links them. The tighter correlation ( for ISM), compared to the others, likely stems from a more direct physical connection rather than a mere algebraic coincidence. This particular relation directly links the jet geometry (), the total energy output (), and the intrinsic spectral property (), which are all fundamental properties of the prompt emission phase itself. In contrast, correlations involving the , such as , integrate a parameter from a later, distinct emission phase governed by the central engine’s late-time activity and the circumburst environment. The increased scatter in these relations is therefore expected, as they connect two potentially independent physical regimes. Consequently, the correlation points to an intrinsic physical relation between the key properties of the GRB jet at the prompt emission. Taken together, these results show that the GRB jet is not only related to the prompt emission but also to the X-ray plateau emission, affecting the energy released by the reactivation of the later central engine.

A key limitation of this study lies in the sample selection criteria. The requirement for simultaneous detection of both a clear X-ray plateau and a measurable jet break inevitably selects bright, well-studied GRBs, representing only a small and potentially non-representative subset of the overall GRB population. Nevertheless, we maintain that this bias does not fundamentally invalidate the intrinsic correlations we have identified. As shown by the parameter distributions in our figures, the physical quantities for our sample span several orders of magnitude. This suggests that the reported scaling relations likely hold across this dynamic range. Furthermore, our analysis of various luminosity-related relations indicates no significant impact on the best-fit slopes from the inclusion of fainter GRBs. Ultimately, a conclusive investigation of off-axis events exhibiting both plateaus and jet breaks will require larger, statistically complete samples from future missions.

Among the 40 GRBs in our sample, 2 are SGRBs, namely GRB 090426 and GRB 051221A. GRB 090426 is generally considered to be associated with the death of a massive star and is speculated to be a LGRB. Therefore, it is reasonable that this GRB conforms to all the correlations. However, GRB 051221A does not follow the and correlations. Due to the small amount of SGRBs, it cannot be determined whether SGRBs with both X-ray plateau emission and jet features conform to all the correlations. On the other hand, the sample does not include GRBs with "internal plateau" features, so it is not possible to determine whether GRBs with narrow jet structures have a physical mechanism that suddenly shuts off energy injection after the collapse of a super-massive neutron star into a black hole. These need to be further explored with a larger sample in the future. These open questions highlight the need for a larger and more complete sample. The superior detection capabilities of new missions like SVOM and the Einstein Probe will provide the necessary data to investigate these key issues. Their ability to expand the sample size will be crucial for verifying the universality of the correlations uncovered in this work, particularly the new three-parameter relations. Furthermore, by populating the high-redshift regime and capturing fainter events, these observatories will enable us to determine whether these fundamental planes evolve with cosmic time.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/universe11120397/s1, Figure S1: MCMC fitting results of L-T-E relation.

Author Contributions

Investigation, D.-L.M., S.-Y.Z. and W.-P.S.; Data curation, S.-Y.Z. and W.-P.S.; Writing—original draft, D.-L.M.; Writing—review and editing, D.-L.M. and F.-W.Z.; Supervision, F.-W.Z.; Project administration, F.-W.Z.; Funding acquisition, F.-W.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 12463008), and by the Guangxi Natural Science Foundation (No. 2022GXNSFDA035083).

Data Availability Statement

The public data are available from the GCN Circulars Archive.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Band, D.; Matteson, J.; Ford, L.; Schaefer, B.; Palmer, D.; Teegarden, B.; Cline, T.; Briggs, M.; Paciesas, W.; Pendleton, G.; et al. BATSE Observations of Gamma-Ray Burst Spectra. I. Spectral Diversity. Astrophys. J. 1993, 413, 281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mészáros, P. An Analysis of Gamma-Ray Burst Spectral Break Models. Astrophys. J. 2002, 581, 1236–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Zhang, B. The physics of gamma-ray bursts & relativistic jets. Phys. Rep. 2015, 561, 1–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kouveliotou, C.; Meegan, C.A.; Fishman, G.J.; Bhat, N.P.; Briggs, M.S.; Koshut, T.M.; Paciesas, W.S.; Pendleton, G.N. Identification of Two Classes of Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1993, 413, L101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bromberg, O.; Nakar, E.; Piran, T.; Sari, R. Short versus Long and Collapsars versus Non-collapsars: A Quantitative Classification of Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 2013, 764, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galama, T.J.; Vreeswijk, P.M.; van Paradijs, J.; Kouveliotou, C.; Augusteijn, T.; Böhnhardt, H.; Brewer, J.P.; Doublier, V.; Gonzalez, J.-F.; Leibundgut, B.; et al. An unusual supernova in the error box of the γ-ray burst of 25 April 1998. Nature 1998, 395, 670–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacFadyen, A.I.; Woosley, S.E. Collapsars: Gamma-Ray Bursts and Explosions in “Failed Supernovae”. Astrophys. J. 1999, 524, 262–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanek, K.; Matheson, T.; Garnavich, P.; Martini, P.; Berlind, P.; Caldwell, N.; Challis, P.; Brown, W.R.; Schild, R.; Krisciunas, K.; et al. Spectroscopic Discovery of the Supernova 2003dh Associated with GRB 030329. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2003, 591, L17–L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campana, S.; Mangano, V.; Blustin, A.J.; Brown, P.; Burrows, D.N.; Chincarini, G.; Cummings, J.R.; Cusumano, G.; Valle, M.D.; Malesani, D.; et al. The association of GRB 060218 with a supernova and the evolution of the shock wave. Nature 2006, 442, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Postigo, A.d.; Leloudas, G.; Kruhler, T.; Cano, Z.; Hjorth, J.; Malesani, D.; Fynbo, J.P.U.; Thoene, C.C.; Sanchez-Ramirez, R.; et al. Discovery of the Broad-lined Type Ic SN 2013cq Associated with the Very Energetic GRB 130427A. Astrophys. J. 2013, 776, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbott, B.P.; Abbott, R.; Abbott, T.D.; Acernese, F.; Ackley, K.; Adams, C.; Adams, T.; Addesso, P.; Adhikari, R.X.; Adya, V.B.; et al. Gravitational Waves and Gamma-Rays from a Binary Neutron Star Merger: GW170817 and GRB 170817A. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2017, 848, L13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troja, E.; Fryer, C.L.; O’Connor, B.; Ryan, G.; Dichiara, S.; Kumar, A.; Ito, N.; Gupta, R.; Wollaeger, R.T.; Norris, J.P.; et al. A nearby long gamma-ray burst from a merger of compact objects. Nature 2022, 612, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rastinejad, J.C.; Gompertz, B.P.; Levan, A.J.; Fong, W.; Nicholl, M.; Lamb, G.P.; Malesani, D.B.; Nugent, A.E.; Oates, S.R.; Tanvir, N.R.; et al. A kilonova following a long-duration gamma-ray burst at 350 Mpc. Nature 2022, 612, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Troja, E.; O’Connor, B.; Fryer, C.L.; Im, M.; Durbak, J.; Paek, G.S.H.; Ricci, R.; Bom, C.R.; Gillanders, J.H.; et al. A lanthanide-rich kilonova in the aftermath of a long gamma-ray burst. Nature 2024, 626, 742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Ai, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Wang, X.I.; Yang, Y.; Yin, Y.; Li, Y.; Lü, H.-J. A long-duration gamma-ray burst with a peculiar origin. Nature 2022, 612, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levan, A.J.; Gompertz, B.P.; Salafia, O.S.; Bulla, M.; Burns, E.; Hotokezaka, K.; Izzo, L.; Lamb, G.P.; Malesani, D.B.; Oates, S.R.; et al. Heavy-element production in a compact object merger observed by JWST. Nature 2024, 626, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahumada, T.; Singer, L.P.; Anand, S.; Coughlin, M.W.; Kasliwal, M.M.; Ryan, G.; Andreoni, I.; Cenko, S.B.; Fremling, C.; Kumar, H.; et al. Discovery and confirmation of the shortest gamma-ray burst from a collapsar. Nat. Astron. 2021, 5, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.-B.; Liu, Z.-K.; Peng, Z.-K.; Li, Y.; Lü, H.-J.; Yang, J.; Yang, Y.-S.; Yang, Y.-H.; Meng, Y.-Z.; Zhou, J.-H.; et al. A peculiarly short-duration gamma-ray burst from massive star core collapse. Nat. Astron. 2021, 5, 911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, A.; Rothberg, B.; Palazzi, E.; Kann, D.A.; D’Avanzo, P.; Amati, L.; Klose, S.; Perego, A.; Pian, E.; Guidorzi, C.; et al. The Peculiar Short-duration GRB 200826A and Its Supernova. Astrophys. J. 2022, 932, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Pandey, S.B.; Kumar, A.; Aryan, A.; Ror, A.K.; Sharma, S.; Misra, K.; Castro-Tirado, A.J.; Tiwari, S.N. Photometric studies on the host galaxies of gamma-ray bursts using 3.6 m Devasthal optical telescope. J. Astrophys. Astron. 2022, 43, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, R.; Racusin, J.L.; Sanchez-Ramirez, R.; Hu, Y.; Rossi, A.; Garcia, M.D.C.; Nuessle, P.; Castro-Tirado, A.J.; Oates, S.; Bordoloi, P.P.; et al. Deciphering the Physical Origin of GRB 240825A: A Long GRB Lacking a Bright Supernova. arXiv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wijers, R.A.M.J.; Rees, M.J.; Meszaros, P. Shocked by GRB 970228: The afterglow of a cosmological fireball. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 1997, 288, L51–L56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, P. Gamma-ray bursts. Rep. Prog. Phys. 2006, 69, 2259–2321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mészáros, P.; Rees, M.J. Optical and Long-Wavelength Afterglow from Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 1997, 476, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaitescu, A.; Mészáros, P.; Rees, M.J. Multiwavelength Afterglows in Gamma-Ray Bursts: Refreshed Shock and Jet Effects. Astrophys. J. 1998, 503, 314–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.F.; Gou, L.J.; Dai, Z.G.; Lu, T. Overall Evolution of Jetted Gamma-Ray Burst Ejecta. Astrophys. J. 2000, 543, 90–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, S.-X.; Wu, X.-F.; Zou, Y.-C.; Dai, Z.-G. The Bright Reverse Shock Emission in the Optical Afterglows of Gamma-Ray Bursts in a Stratified Medium. Astrophys. J. 2020, 895, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Fan, Y.Z.; Dyks, J.; Kobayashi, S.; Mészáros, P.; Burrows, D.N.; Nousek, J.A.; Gehrels, N. Physical Processes Shaping Gamma-Ray Burst X-Ray Afterglow Light Curves: Theoretical Implications from the Swift X-Ray Telescope Observations. Astrophys. J. 2006, 642, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Mészáros, P. Gamma-Ray Burst Afterglow with Continuous Energy Injection: Signature of a Highly Magnetized Millisecond Pulsar. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2001, 552, L35–L38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, A.; O’Brien, P.T.; Tanvir, N.R.; Zhang, B.; Evans, P.A.; Lyons, N.; Levan, A.J.; Willingale, R.; Page, K.L.; Onal, O.; et al. The unusual X-ray emission of the short Swift GRB 090515: Evidence for the formation of a magnetar? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2010, 409, 531–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowlinson, A.; O’Brien, P.T.; Metzger, B.D.; Tanvir, N.R.; Levan, A.J. Signatures of magnetar central engines in short GRB light curves. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 430, 1061–1087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bucciantini, N.; Metzger, B.D.; Thompson, T.A.; Quataert, E. Short gamma-ray bursts with extended emission from magnetar birth: Jet formation and collimation. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2012, 419, 1537–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompertz, B.P.; O’Brien, P.T.; Wynn, G.A.; Rowlinson, A. Can magnetar spin-down power extended emission in some short GRBs? Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2013, 431, 1745–1751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, J.-J.; Zhang, B.; Kuiper, R. Propagation of Relativistic, Hydrodynamic, Intermittent Jets in a Rotating, Collapsing GRB Progenitor Star. Astrophys. J. 2016, 833, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, C.-H.; Huang, Y.-F.; Geng, J.-J.; Zhang, Z.-B. Statistical Study of Gamma-Ray Bursts with a Plateau Phase in the X-Ray Afterglow. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2019, 245, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.-K.; Shi, Y.-R.; Zhu, S.-Y.; Sun, W.-P.; Zhang, F.-W. Statistical properties of the X-ray afterglow shallow decay phase and their relationships with the prompt gamma-ray emission of gamma-ray bursts. Astrophys. Space Sci. 2022, 367, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, C.; Huang, Y.-F.; Xu, F. Pseudo-redshifts of Gamma-Ray Bursts Derived from the L-T-E Correlation. Astrophys. J. 2023, 943, 126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gompertz, B.P.; O’Brien, P.T.; Wynn, G.A. Magnetar powered GRBs: Explaining the extended emission and X-ray plateau of short GRB light curves. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2014, 438, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Xie, W.; Lei, W.-H.; Zou, Y.-C.; Lü, H.-J.; Liang, E.-W.; Gao, H.; Wang, D.-X. Signature of a Newborn Black Hole from the Collapse of a Supra-massive Millisecond Magnetar. Astrophys. J. 2017, 849, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.-J.; Liu, T.; Xu, R.-X.; Mu, H.-J.; Song, C.-Y.; Lin, D.-B.; Gu, W.-M. The X-Ray Light Curve in GRB 170714A: Evidence for a Quark Star? Astrophys. J. 2018, 854, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Cardone, V.F.; Capozziello, S. A time-luminosity correlation for γ-ray bursts in the X-rays. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2008, 391, L79–L83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Willingale, R.; Capozziello, S.; Fabrizio Cardone, V.; Ostrowski, M. Discovery of a Tight Correlation for Gamma-ray Burst Afterglows with “Canonical" Light Curves. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2010, 722, L215–L219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Ostrowski, M.; Willingale, R. Towards a standard gamma-ray burst: Tight correlations between the prompt and the afterglow plateau phase emission. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2011, 418, 2202–2206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, M.; Huang, Y.F. New three-parameter correlation for gamma-ray bursts with a plateau phase in the afterglow. Astron. Astrophys. 2012, 538, A134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Postnikov, S.; Hernandez, X.; Ostrowski, M. A Fundamental Plane for Long Gamma-Ray Bursts with X-Ray Plateaus. Astrophys. J. Lett. 2016, 825, L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Hernandez, X.; Postnikov, S.; Nagataki, S.; O’brien, P.; Willingale, R.; Striegel, S. A Study of the Gamma-Ray Burst Fundamental Plane. Astrophys. J. 2017, 848, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Zhang, B.; Gao, H.; Lan, L.; Lü, H.; Zhang, B. The Shallow Decay Segment of GRB X-Ray Afterglow Revisited. Astrophys. J. 2019, 883, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Lenart, A.Ł.; Sarracino, G.; Nagataki, S.; Capozziello, S.; Fraija, N. The X-Ray Fundamental Plane of the Platinum Sample, the Kilonovae, and the SNe Ib/c Associated with GRBs. Astrophys. J. 2020, 904, 97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.; Nielson, V.; Sarracino, G.; Rinaldi, E.; Nagataki, S.; Capozziello, S.; Gnedin, O.; Bargiacchi, G. Optical and X-ray GRB Fundamental Planes as cosmological distance indicators. Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 2022, 514, 1828–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, F.; Tang, C.-H.; Geng, J.-J.; Wang, F.-Y.; Wang, Y.-Y.; Kuerban, A.; Huang, Y.-F. X-Ray Plateaus in Gamma-Ray Burst Afterglows and Their Application in Cosmology. Astrophys. J. 2021, 920, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, S.-K.; Qi, Y.-Q.; Xue, F.-X.; Liu, Y.-J.; Wu, X.; Yi, S.-X.; Tang, Q.-W.; Zou, Y.-C.; Wang, F.-F.; Wang, X.-G. The Three-parameter Correlations About the Optical Plateaus of Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 2018, 863, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dainotti, M.G.; Young, S.; Li, L.; Levine, D.; Kalinowski, K.K.; Kann, D.A.; Tran, B.; Zambrano-Tapia, L.; Zambrano-Tapia, A.; Cenko, S.B.; et al. The Optical Two- and Three-dimensional Fundamental Plane Correlations for Nearly 180 Gamma-Ray Burst Afterglows with Swift/UVOT, RATIR, and the Subaru Telescope. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2022, 261, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rhoads, J.E. How to Tell a Jet from a Balloon: A Proposed Test for Beaming in Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1997, 487, L1–L4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-J.; Zhang, Z.-B.; Zhang, C.-T.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Dong, X.-F. Properties of Short GRB Pulses in the Fourth BATSE Catalog: Implications for the Structure and Evolution of the Jetted Outflows. Astrophys. J. 2020, 892, 113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, R.; Piran, T.; Halpern, J.P. Jets in Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. Lett. 1999, 519, L17–L20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, W.; Zhang, J.-C.; Zhang, Q.-X.; Liang, J.-T.; Luan, X.-H.; Zhou, Q.-Q.; Yi, S.-X.; Wang, F.-F.; Zhang, S.-T. Statistical Study of Gamma-Ray Bursts with Jet Break Features in Multiwavelength Afterglow Emissions. Astrophys. J. 2020, 900, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Zou, Y.-C.; Liu, F.; Liao, B.; Liu, Y.; Chai, Y.; Xia, L. A Comprehensive Statistical Study of Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 2020, 893, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.B.; Zhang, C.T.; Zhao, Y.X.; Luo, J.J.; Jiang, L.Y.; Wang, X.L.; Han, X.L.; Terheide, R.K. Spectrum-energy Correlations in GRBs: Update, Reliability, and the Long/Short Dichotomy. Publ. Astrons. Soc. Pac. 2018, 130, 054202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, B.; Lü, H.-J. A Comparative Study of Long and Short GRBs. I. Overlapping Properties. Astrophys. J. Suppl. Ser. 2016, 227, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bloom, J.S.; Frail, D.A.; Sari, R. The Prompt Energy Release of Gamma-Ray Bursts using a Cosmological k-Correction. Astron. J. 2001, 121, 2879–2888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, B.E. The Hubble Diagram to Redshift >6 from 69 Gamma-Ray Bursts. Astrophys. J. 2007, 660, 16–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Agostini, G. Fits, and especially linear fits, with errors on both axes, extra variance of the data points and other complications. arXiv 2005, arXiv:physics/0511182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Hogg, D.W.; Lang, D.; Goodman, J. emcee: The MCMC Hammer. Publ. Astrons. Soc. Pac. 2013, 125, 306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).