Fault Process Modeling and Transient Stability Analysis of Grid-Following Photovoltaic Converter Grid-Connected System

Abstract

1. Introduction

- (1)

- The lack of transient stability analysis models in previous research for the whole fault process makes it difficult to characterize the transient characteristics of the system during the fault recovery period.

- (2)

- The impact mechanism of active power recovery control on system transient stability remains unclear, which may lead to misjudgment of stability analysis results and an overly conservative design of system fault clearance.

- (1)

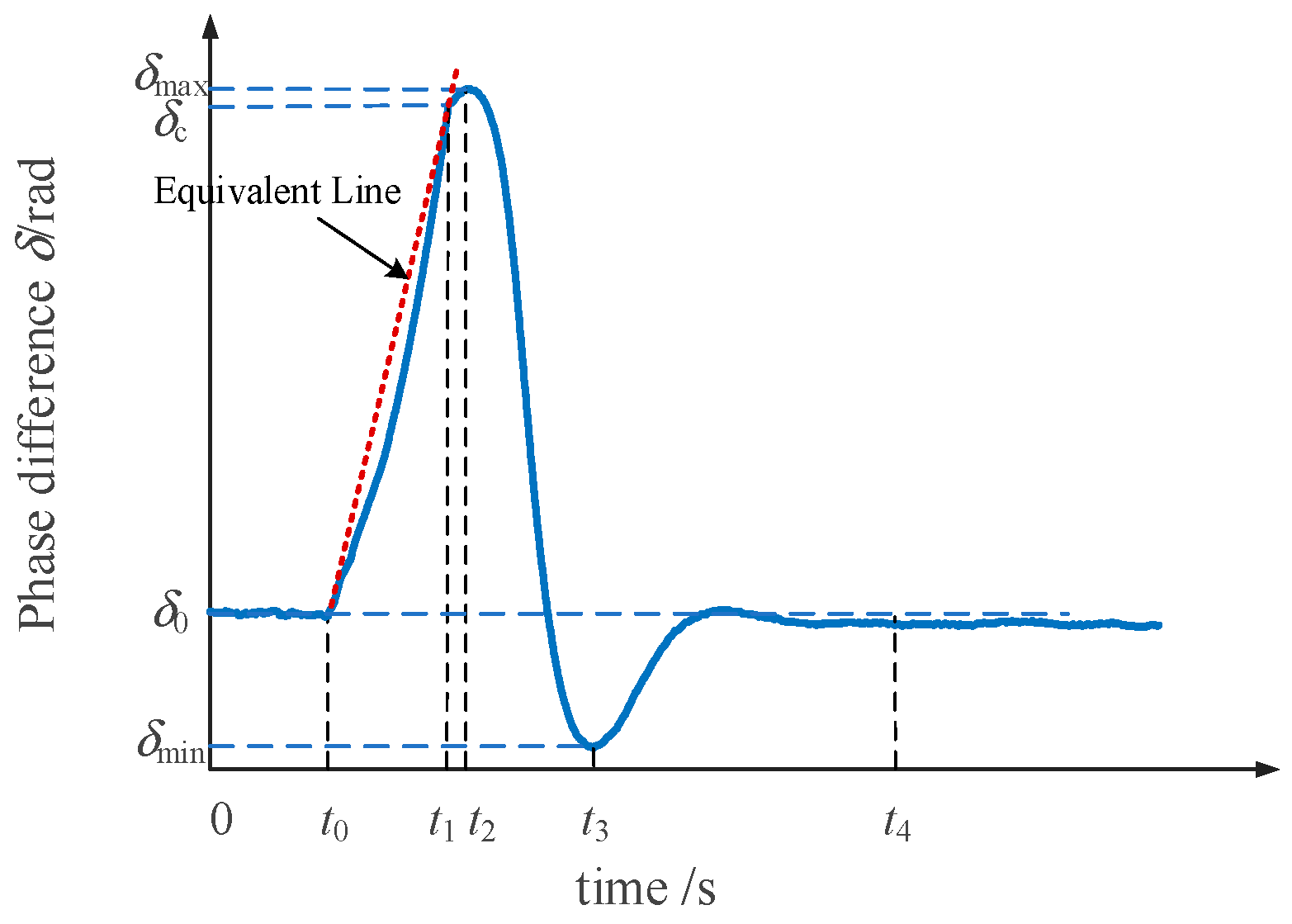

- A piecewise linear description method is utilized to approximate the dynamic characteristics of the phase difference between the PCC voltage and the grid voltage during the fault recovery process, thereby establishing a mapping relationship between the phase difference and time. A mathematical model capable of characterizing the system transient stability throughout the whole fault process is proposed.

- (2)

- The influence mechanism of active power recovery control on the transient stability of the GFL-PV converter system is revealed. The influence of the active power recovery rate on the transient stability of the system is analyzed.

- (3)

- Based on the proposed model, the critical fault clearing time (CCT) of the system is calculated, which reduces the conservatism in previous methods.

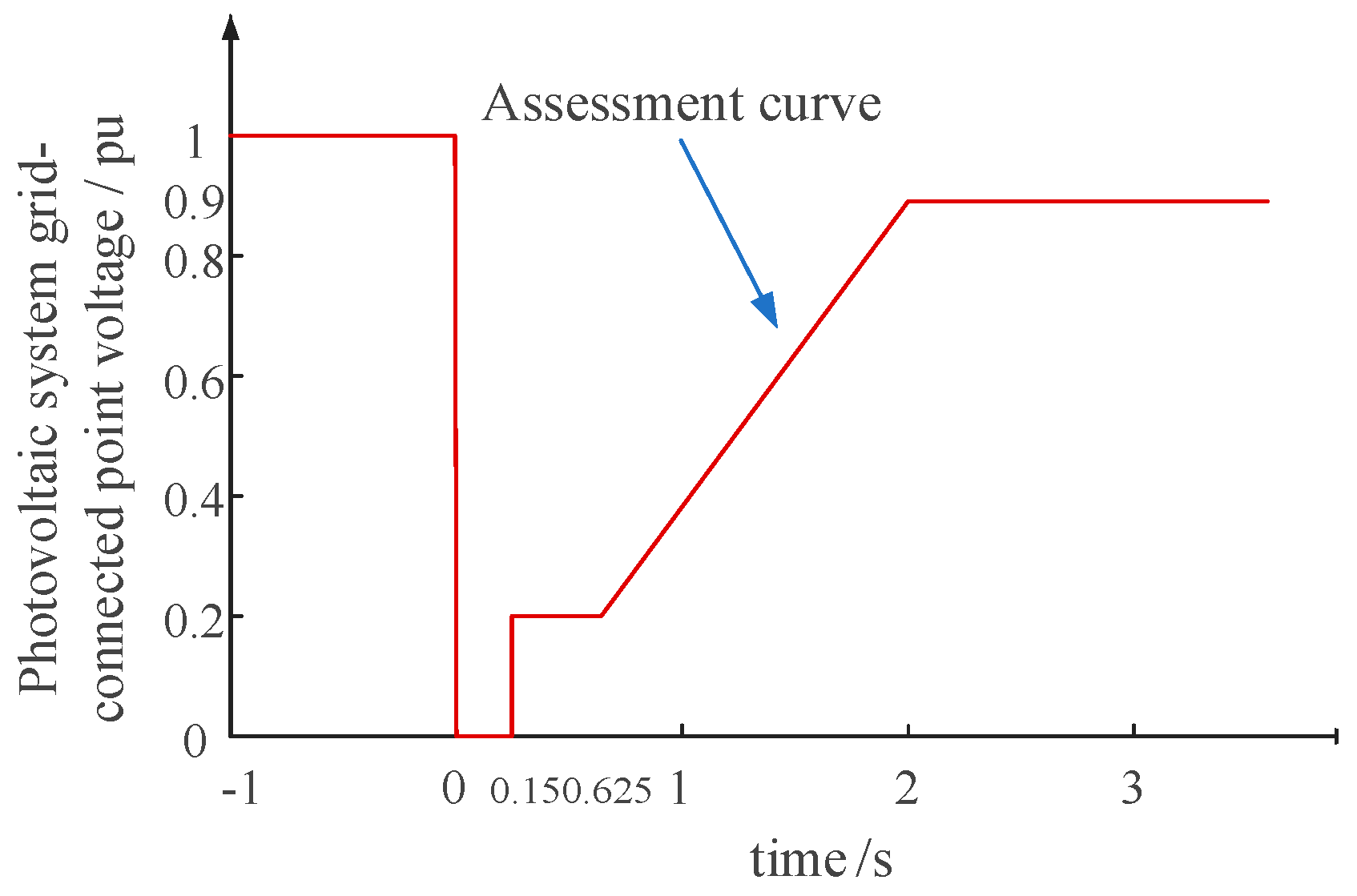

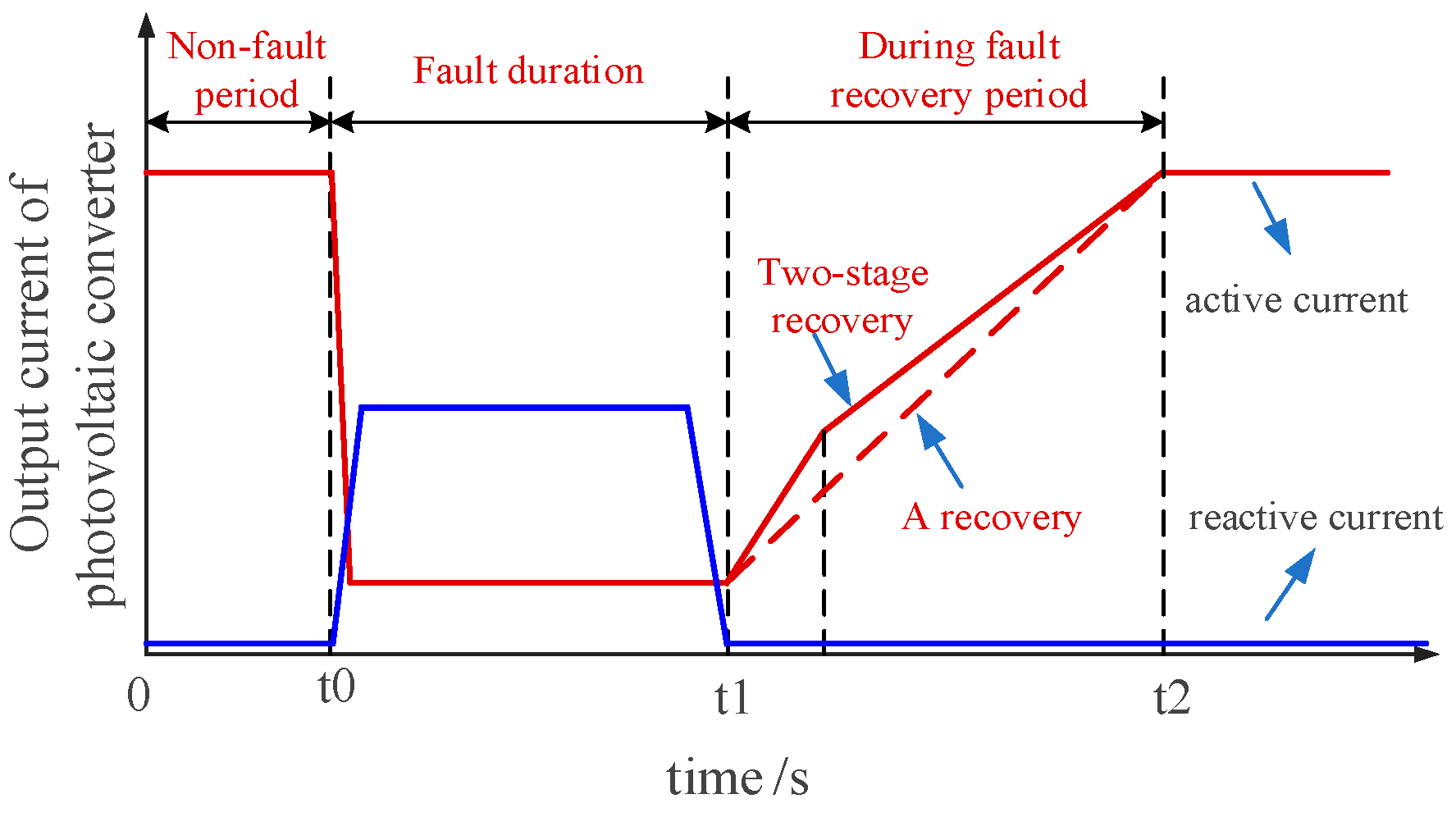

2. Control Strategy of GFL-PV Converter Grid-Connected System in the Whole Process of Fault

2.1. The Main Circuit Structure and Control Strategy of GFL-PV Converter

- (1)

- Control strategy during non-fault period

- (2)

- Control strategy during fault duration period

- (3)

- Control strategy during fault recovery period

2.2. Impact of Active Power Recovery Control on Transient Stability of the System

3. Transient Modeling of a GFL-PV Converter Grid-Connected System in the Whole Fault Process

- (1)

- The time difference between the fault clearing instant t1 and instant t2 when the phase difference reaches its maximum is sufficiently small, allowing higher-order residual terms in the Taylor expansion to be neglected.

- (2)

- The current loop exhibits high bandwidth, thereby enabling the neglect of its dynamic characteristics.

3.1. Transient Modeling During Non-Fault Period

3.2. Transient Modeling During Fault Duration

3.3. Transient Modeling During Fault Recovery Period

4. Transient Stability Analysis of GFL-PV Converter Grid-Connected System

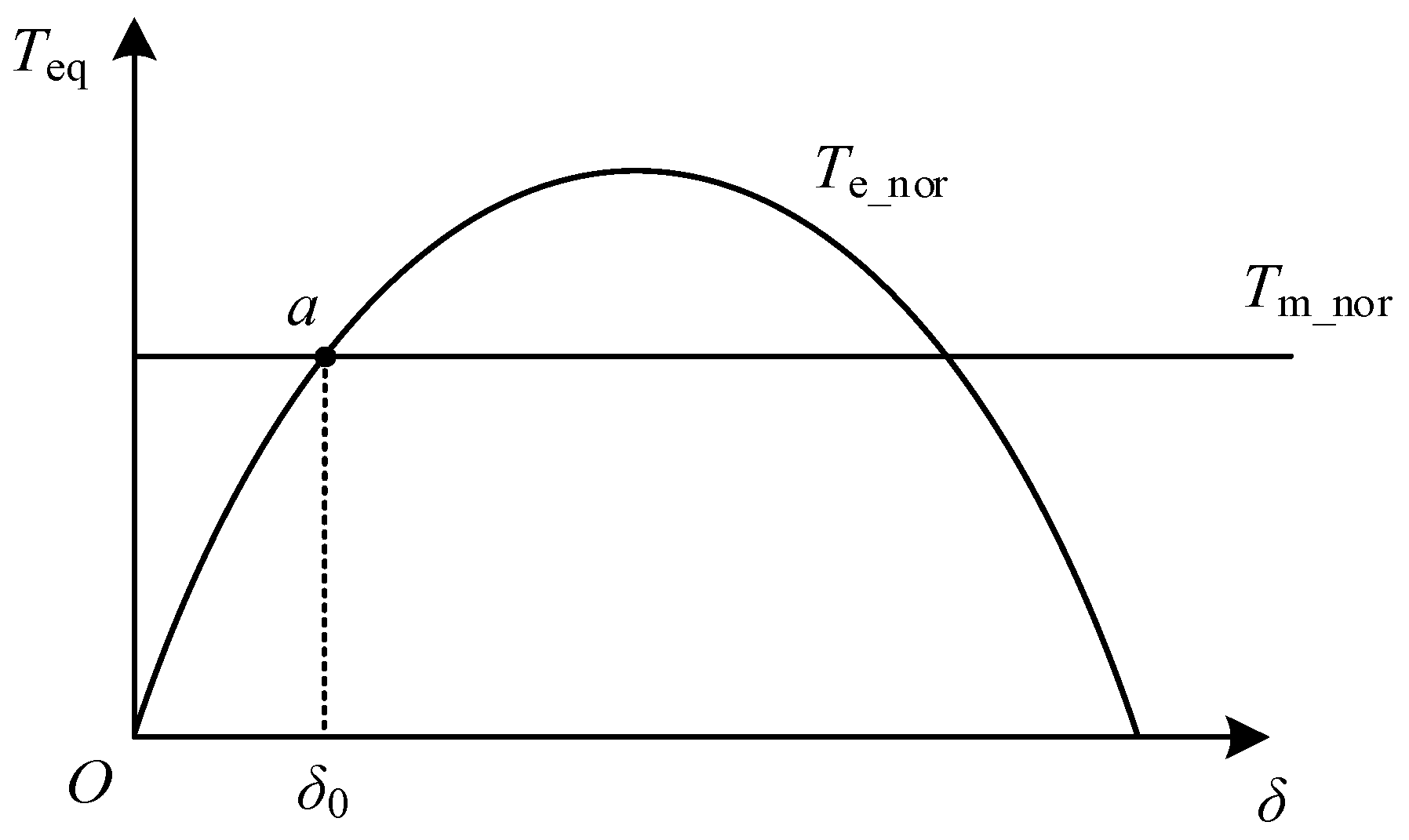

4.1. Transient Stability Analysis During Non-Fault Period

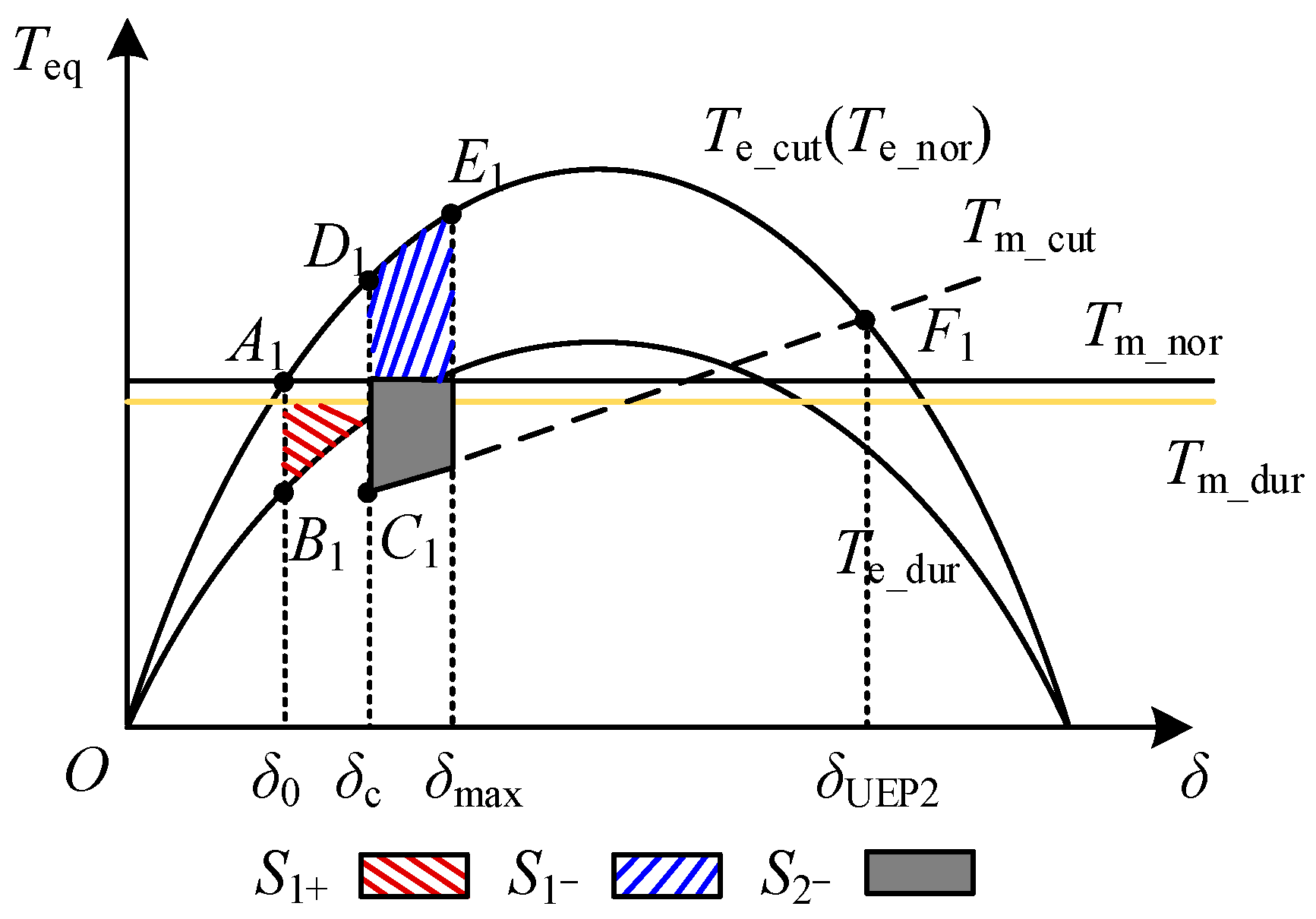

4.2. Transient Stability Analysis During Fault Duration Period

4.3. Transient Stability Analysis During Fault Recovery Period

4.4. Impact of Active Power Recovery Rate k on System Transient Stability

5. Quantitative Calculation of CCT

6. Simulation Verification

6.1. Validity Assessment of Transient Model

6.2. Transient Stability Analysis Considering Active Power Recovery Control Strategy

6.3. Impact of Active Power Recovery Rate k on System Transient Stability

7. Conclusions

- (1)

- A transient stability analysis model considering the whole fault process is proposed based on the piecewise linear description method. This model addresses the existing gap in characterizing transient behavior throughout the whole fault duration.

- (2)

- The active power recovery control reduces the equivalent mechanical power during the fault recovery period, thereby increasing the decelerating area and enhancing the system’s transient stability.

- (3)

- The faster the active power recovery rate, the worse the system’s transient stability; conversely, the slower the recovery rate, the better the transient stability.

- (4)

- Based on the proposed model, the CCT exhibits lower conservatism, which enhances the accuracy of system transient stability assessment.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xiao, X.; Zheng, Z. New power systems dominated by renewable energy towards the goal of emission peak and carbon neutrality: Contribution, key techniques, and challenges. Adv. Eng. Sci. 2022, 54, 47–59. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, B.; Xie, K.; Shao, C.; Pan, C.; Lin, C.; Zhao, Y. Review and prospect of frequency stability analysis and control of low-inertia power systems. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2023, 47, 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Wen, Y.; Yang, W.; Lin, X. Review and prospect of frequency stability analysis and control of low inertia power systems. Electr. Power Autom. Equip. 2020, 40, 211–222. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.; Liu, F.; Jiang, Q.; Mao, H. Large-disturbance stability of power systems with high penetration of renewables and inverters: Phenomena, challenges, and perspectives. J. Tsinghua Univ. (Sci. Technol.) 2021, 61, 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Chen, X. Overview of Broadband Oscillation Mitigation of New Energy Generation Power System Based on Impedance Perspective. Proc. CSEE 2024, 44, 9672–9691. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Du, X.; Guan, B.; Zhang, B. Impedance Modeling and Stability Analysis for Grid-connected Inverter Containing Operating Point Variables. Power Syst. Technol. 2022, 46, 3642–3650. [Google Scholar]

- Song, S.; Wei, Z.; Lin, Y.; Liu, B.; Liu, H. Impedance modeling and stability analysis of PV grid-connected inverter systems considering frequency coupling. CSEE J. Power Energy Syst. 2020, 6, 279–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, H.; He, C.; Liu, Y.; He, X.; Li, M. Overview on Transient Synchronization Stability of Renewable-rich Power Systems. High Volt. Technol. 2022, 48, 3367–3383. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhan, M. Dominant Transient Unstable Characteristics of PLL-based Grid-connected Converters. Proc. CSEE 2023, 43, 9285–9297. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Liu, D. Transient stability enhancement strategy for grid-following inverter based on improved phase-locked loop and energy dissipation. Electronics 2025, 14, 3520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, Y.; Yao, J.; Chen, Y.; Liu, Y.; Li, X.; Yang, D.; Jin, R.; Zhao, L. Transient stability analysis for Grid-Connected PLL Based VSC during Asymmetric Grid Faults. In Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Energy, Power and Electrical Engineering (EPEE), Wuhan, China, 20–22 September 2024; pp. 877–880. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, C.; Lyu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Blaabjerg, F. Transient Synchronization Stability Analysis of Grid-Following Converter Considering the Coupling Effect of Current Loop and Phase Locked Loop. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2024, 39, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Xie, X.; He, J.; Jiang, Q. Synchronization Stability Issues of Grid-tied Converters with Saturation Nonlinearities. Proc. CSEE 2025, 45, 6886–6896. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, C.; Chen, J.; Si, W. Analysis of Phase-Locked Loop Filter Delay on Transient Stability of Grid-Following Converters. Electronics 2024, 13, 986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Yao, J.; Liu, Y.; Chen, S.; Sun, P.; Huang, S. Modeling and transient synchronization stability analysis for PLL-based renewable energy generator considering sequential switching schemes. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2022, 37, 2165–2179. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, D.; Ma, Y.; Hu, J. Multi-timescale Transient Stability Issues and Research Status of Renewable Energy Grid-connected Systems During Grid Faults. Proc. CSEE 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 19964-2012; Technical Specifications for the Integration of Photovoltaic Power Stations into Power Systems. Quality Inspection Press: Beijing, China, 2012.

- Hu, Q.; Fu, L.; Ma, F.; Wang, G.; Liu, C.; Ma, Y. Impact of LVRT control on transient synchronizing stability of PLL-based wind turbine converter connected to high impedance AC grid. IEEE Trans. Power Syst. 2023, 38, 5445–5458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Han, T.; Wang, L.; Zhu, Z.; Huang, H.; Ding, J.; Wu, Z. Pipeline deformation prediction based on multi-source monitoring information and novel data-driven model. Eng. Struct. 2025, 337, 120461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Dong, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, S.; Shen, J. Characteristic Description and Transient Overvoltage Suppression of Doubly-fed Wind Turbines with LCC-HVDC Commutation Failure. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 29–38. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Tang, Y.; Tian, Z.; Zha, X.; Sun, J.; Li, Y. Synchronization stability analysis of grid-connected inverter based on improved equal area criterion. Autom. Electr. Power Syst. 2022, 46, 208–215. [Google Scholar]

| Parameter Name | Sign | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Nominal power | S | 0.1 MW |

| Rated AC side voltage | U | 0.4 kV |

| Rated angular frequency | ωg | 100π rad/s |

| Filter inductance | Lf | 2.5 mH |

| Grid inductance | Lg | 2 mH |

| Grid resistance | Rg | 0.2 Ω |

| Active current recovery slope | k | 3 |

| Phase-locked loop proportional gain | KpPLL | 0.2221 |

| Phase-locked loop integral gain | KiPLL | 9.9 |

| CCT | Fault Clearing Time | Acceleration/Deceleration Area | Stability Analysis Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| within CCT | 99 ms | S+ = S− | transient stability |

| without CCT | 103 ms | S+ > S− | transient instability |

| Calculation Model | CCT | CCT in Simulation | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proposed model | 99.9 ms | 102.9 ms | 2.92% |

| Previous model | 90.4 ms | 102.9 ms | 12.14% |

| Active Power Recovery Rate | CCT Using Proposed Model | CCT in Simulation | Error |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 99.9 ms | 102.9 ms | 2.92% |

| 30 | 96.5 ms | 100.5 ms | 3.98% |

| 300 | 90.4 ms | 98.4 ms | 8.13% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wei, Z.; Xu, T.; Wang, Y.; Mu, J.; Cheng, L.; Chen, N.; Ge, L.; Du, X. Fault Process Modeling and Transient Stability Analysis of Grid-Following Photovoltaic Converter Grid-Connected System. Electronics 2025, 14, 4827. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244827

Wei Z, Xu T, Wang Y, Mu J, Cheng L, Chen N, Ge L, Du X. Fault Process Modeling and Transient Stability Analysis of Grid-Following Photovoltaic Converter Grid-Connected System. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4827. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244827

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Ze, Tao Xu, Yan Wang, Jianan Mu, Lin Cheng, Ning Chen, Luming Ge, and Xiong Du. 2025. "Fault Process Modeling and Transient Stability Analysis of Grid-Following Photovoltaic Converter Grid-Connected System" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4827. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244827

APA StyleWei, Z., Xu, T., Wang, Y., Mu, J., Cheng, L., Chen, N., Ge, L., & Du, X. (2025). Fault Process Modeling and Transient Stability Analysis of Grid-Following Photovoltaic Converter Grid-Connected System. Electronics, 14(24), 4827. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244827