A 2.4 GHz CMOS Pulse-Mode Transmitter for RF Body-Contouring Device Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

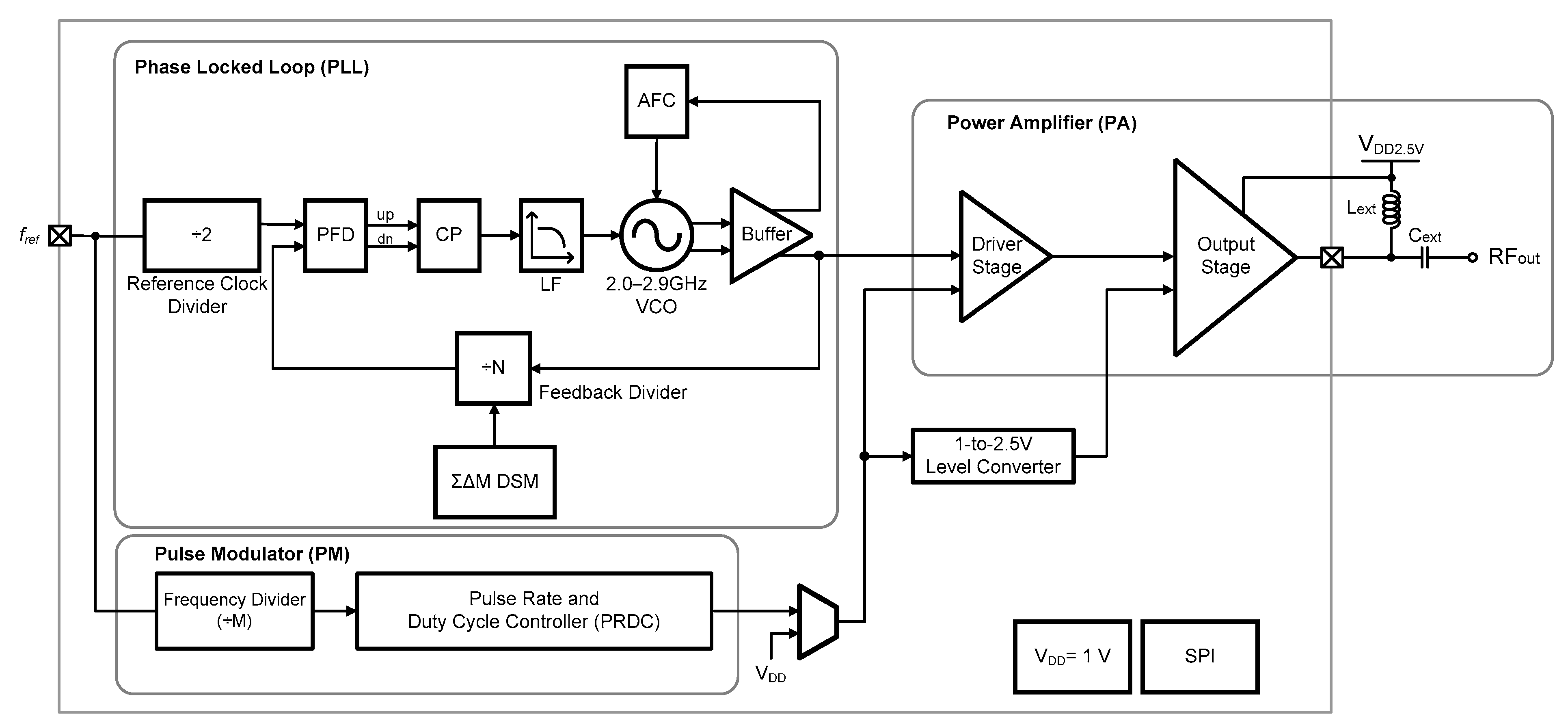

2. CMOS Pulse-Mode RF Transmitter Architecture

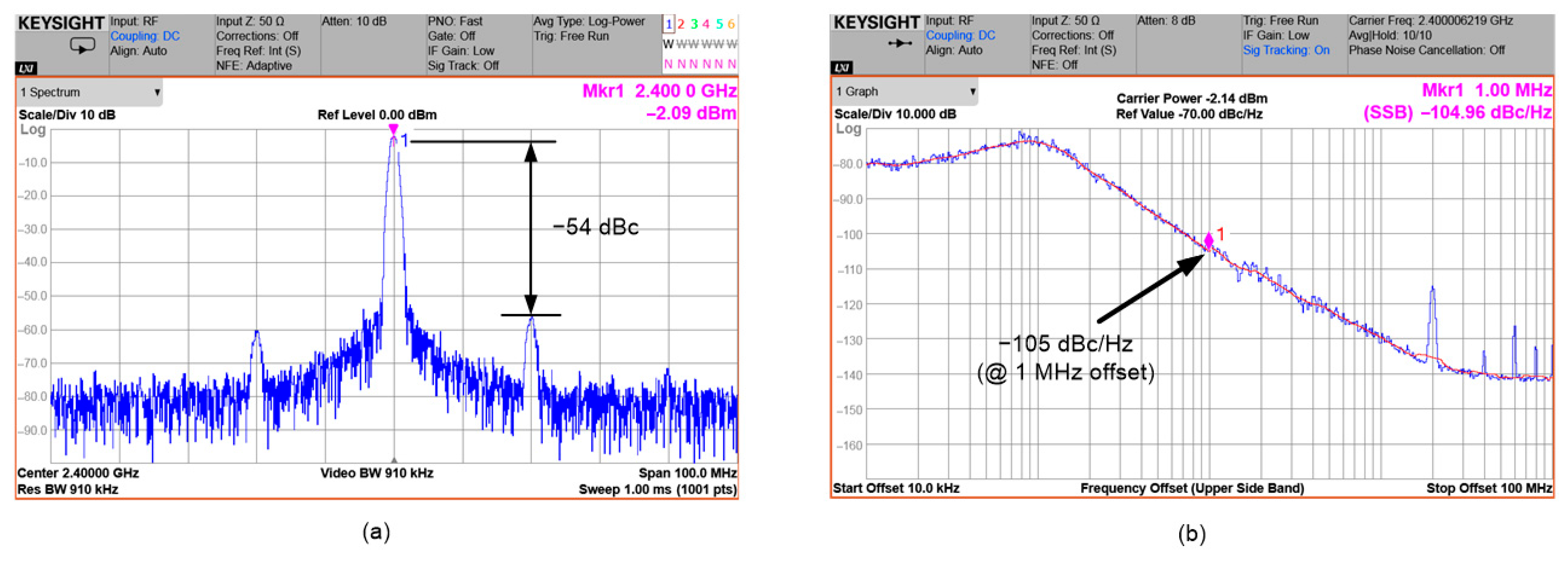

3. Circuit Implementation

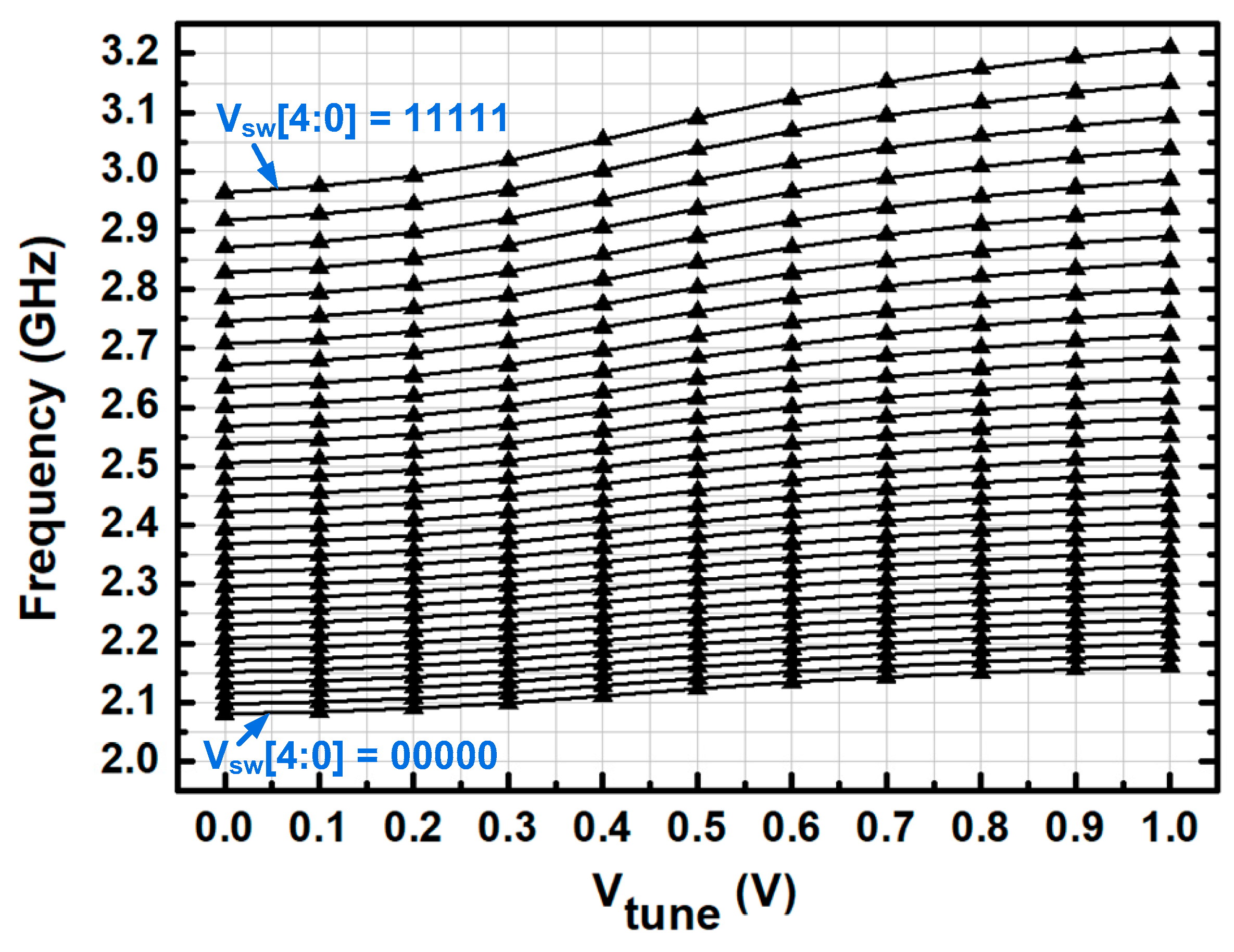

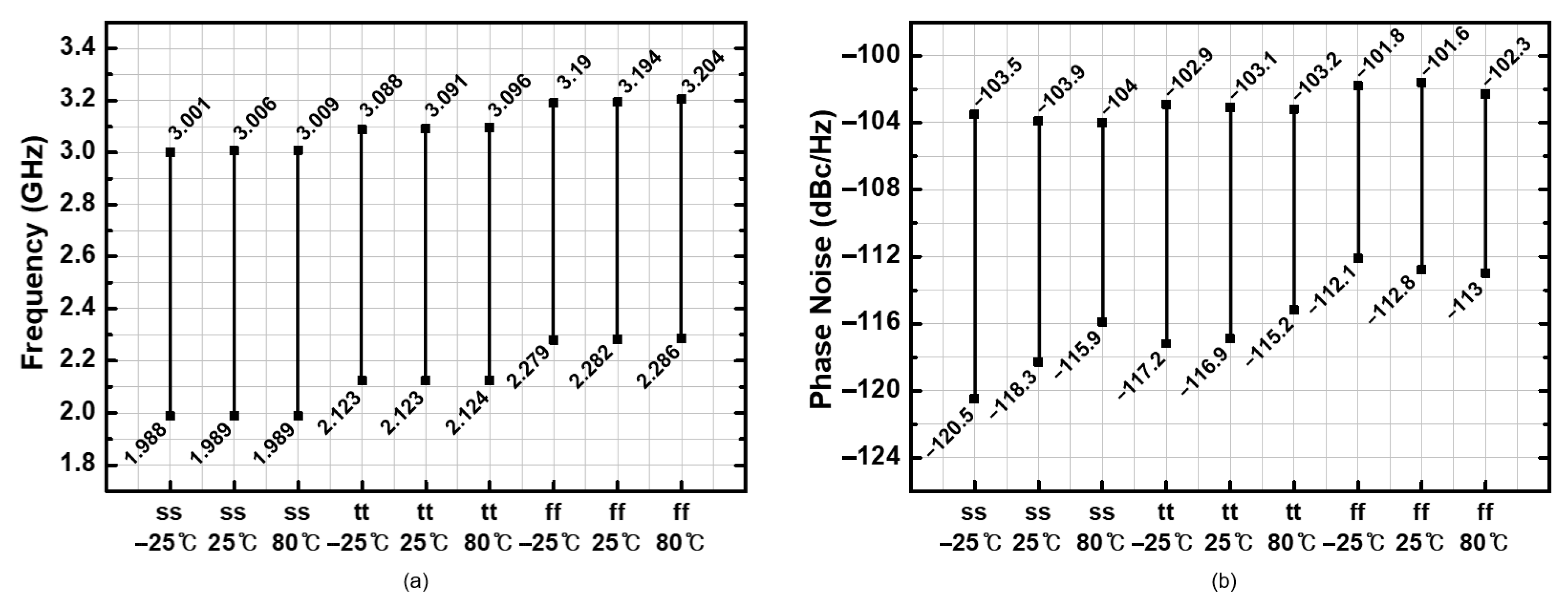

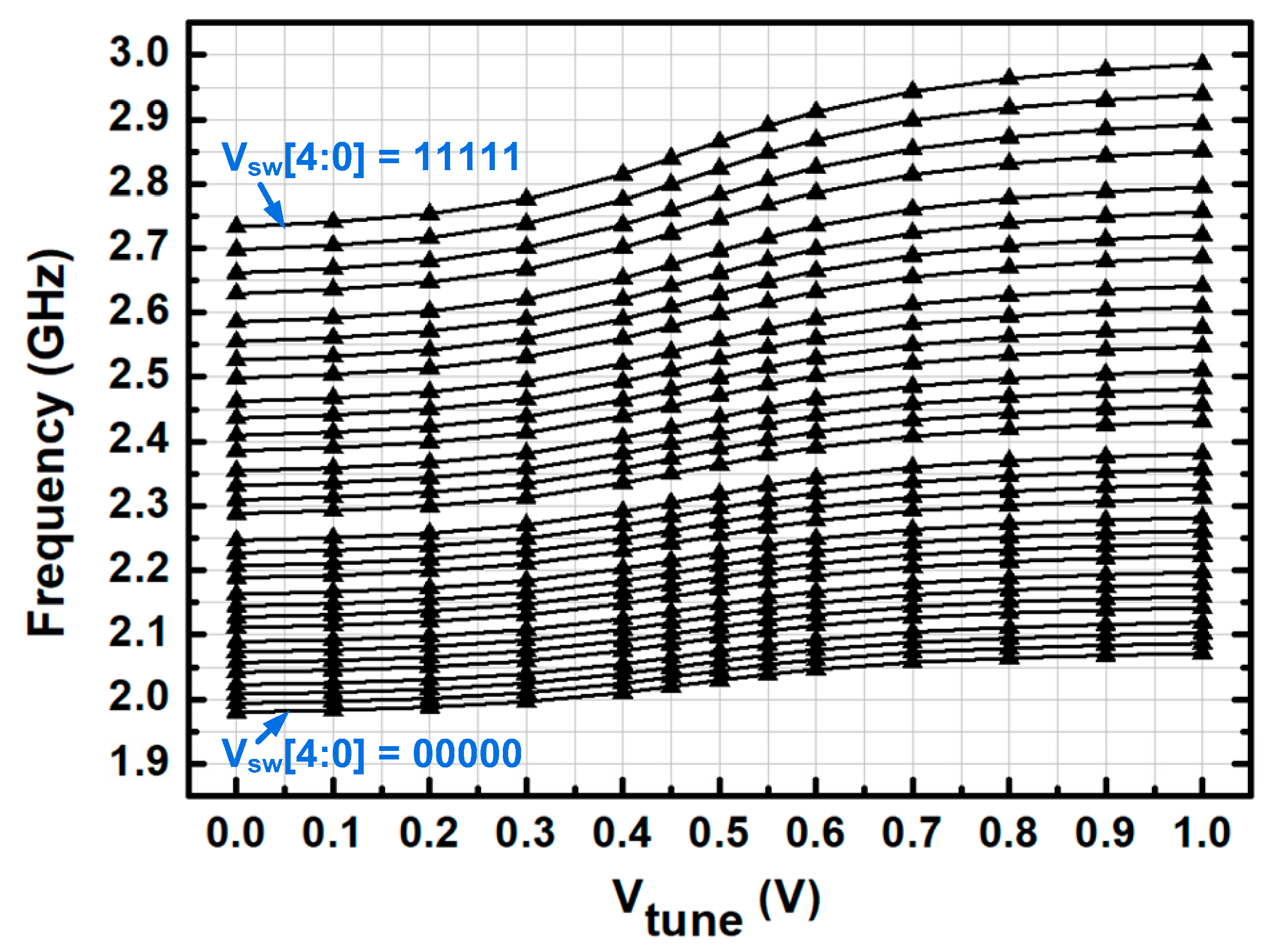

3.1. Voltage-Controlled Oscillator (VCO)

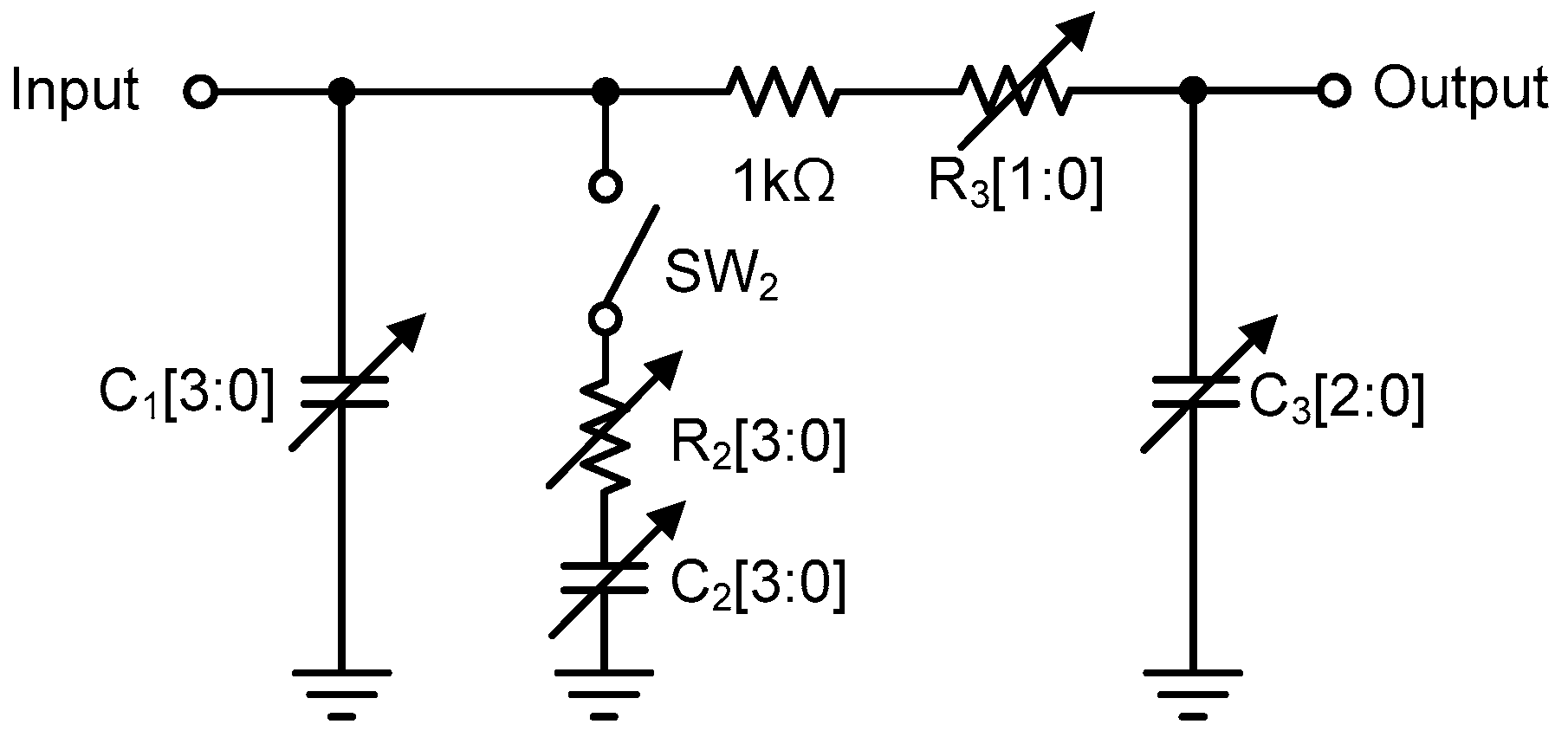

3.2. PLL and On-Chip Loop Filter

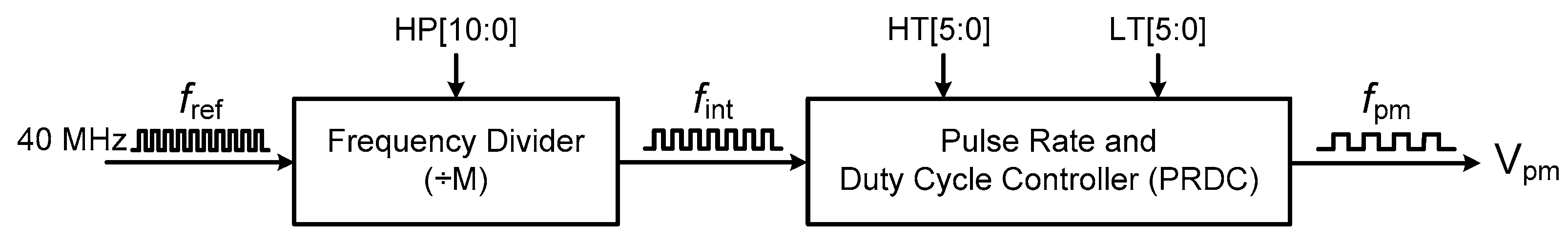

3.3. Pulse Modulator (PM)

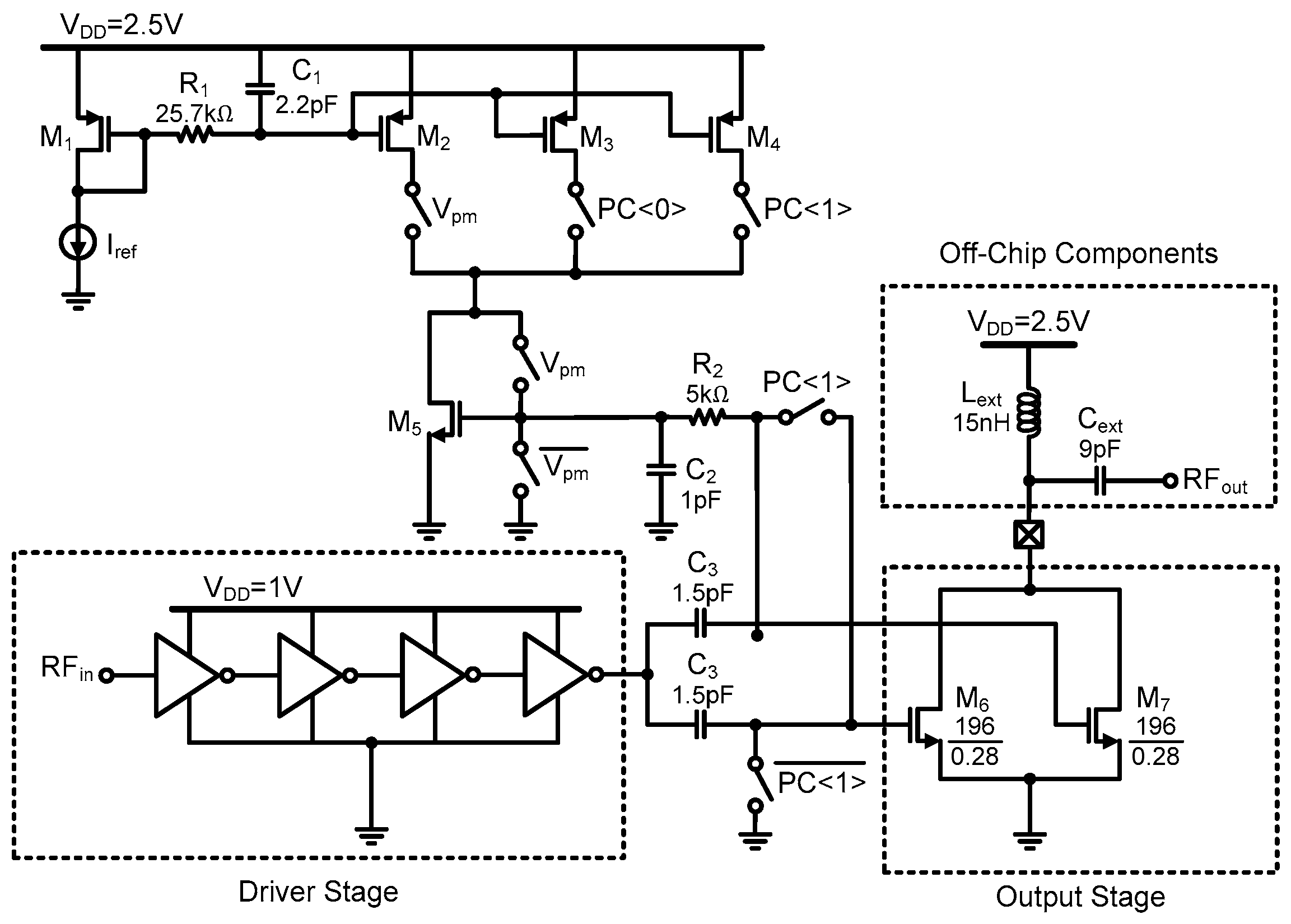

3.4. Power Amplifier (PA)

4. Measurement Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Friedmann, D.P.; Avram, M.M.; Cohen, S.R.; Duncan, D.I.; Goldman, M.P.; Weiss, E.T.; Young, V.L. An evaluation of the patient population for aesthetic treatments targeting abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2014, 13, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazzoni, D.; Lin, M.J.; Dubin, D.P.; Khorasani, H. Review of non-invasive body contouring devices for fat reduction, skin tightening and muscle definition. Australas. J. Dermatol. 2019, 60, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukal, S.A.; Geronemus, R.G. Thermage: The nonablative radiofrequency for rejuvenation. Clin. Dermatol. 2008, 26, 602–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wanitphakdeedecha, R.; Yogya, Y.; Yan, C.; Phumariyapong, P.; Nanchaipruek, Y.; Thongjaroensirikul, P.; Maneeprasopchoke, P.; Techapichetvanich, T.; Eimpunth, S.; Manuskiatti, W. Efficacy and Safety of Monopolar Radiofrequency for Treatment of Lower Facial Laxity in Asians. Dermatol. Ther. 2022, 12, 2563–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salsi, B.; Fusco, I. Non-invasive system delivering microwaves energy for unwanted fat reduction and submental skin tightening: Clinical evidence. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2022, 21, 5657–5664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennardo, L.; Fusco, I.; Cuciti, C.; Sicilia, C.; Salsi, B.; Cannarozzo, G.; Hoffmann, K.; Nisticò, S.P. Microwave therapy for cellulite: An effective non-invasive treatment. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zappia, E.; Bennardo, S.; Fasano, G.; Raffaele, V.; Zingoni, T.; Pieri, L.; Ronconi, L.; Bonan, P.; Bennardo, L.; Tammaro, A.; et al. Efficacy of a new non-invasive system delivering microwave energy for the treatment of abdominal adipose tissue: Results of an immunohistochemical study. Cosmetics 2025, 12, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zappia, E.; Bonan, P.; Coli, F.; Del Re, C.; Cassalia, F.; Tolone, M.; Bennardo, L.; Nisticò, S.P.; Cannarozzo, G. An innovative microwave technology for the treatment of submental skin laxity. Lasers Med. Sci. 2025, 40, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, I.; Lee, D.-M.; Shin, J.-W.; Lee, G.-J.; Kim, E.-S.; Kim, N.-Y. Radio frequency hyperthermia system for skin tightening effect by filled waveguide aperture antenna with compact metamaterials. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2024, 12, 1378084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.; Woo, T.H.; Park, S.; Cheon, C. Microwave Hyperthermic Lipolysis Using External RF Antenna. J. Electr. Eng. Technol. 2012, 7, 759–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golpaygani, T.A.; Movahedi, M.M.; Reza, M. A Study on Performance and Safety Tests of Electrosurgical Equipment. J. Biomed. Phys. Eng. 2016, 6, 175–182. [Google Scholar]

- Naqvi, S.A.R.; Manoufali, M.; Beadaa, M.; Foong, D.; Mobashsher, A.T.; Abbosh, A.M. In Vivo Human Skin Dielectric Properties Characterization and Statistical Analysis at Frequencies From 1 to 30 GHz. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2021, 70, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Kubat, N.J.; Isenberg, R.A. Pulsed radio frequency energy (PRFE) use in human medical applications. Electromagn. Biol. Med. 2011, 30, 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gazelka, H.M.; Knievel, S.; Mauck, W.D.; Moeschler, S.M.; Pingree, M.J.; Rho, R.H.; Lamer, T.J. Incidence of neuropathic pain after radiofrequency denervation of the third occipital nerve. J. Pain Res. 2014, 7, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, M.C. Efficacy of Pulsed Radiofrequency Stimulation in Patients with Peripheral Neuropathic Pain: A Narrative Review. Pain Physician 2018, 21, E225–E234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, Y.; Hur, Y.; Kwak, S.; Shin, D. Body contouring effects of at-home beauty device equipped with suction, radiofrequency, and electrical muscle stimulation functions. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2024, 23, 2581–2591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.; Austin, E.; Masub, N.; Kurtti, A.; George, C.; Jagdeo, J. Home-based devices in dermatology: A systematic review of safety and efficacy. Arch. Dermatol. Res. 2022, 314, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bu, P.; Duan, R.; Luo, J.; Yang, T.; Liu, N.; Wen, C. Development of Home Beauty Devices for Facial Rejuvenation: Establishment of Efficacy Evaluation System. Clin. Cosmet. Investig. Dermatol. 2024, 17, 553–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhou, R.; Liu, S.; Zhu, Z. A 2.4 GHz Ultra-Low-Power Low-Voltage Temperature-Stable Transmitter for Biosensing Applications. In Proceedings of the IEEE Biomedical Circuits and Systems Conference (BioCAS), Xi’an, China, 24–26 October 2024; pp. 342–346. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, C.S.; Lee, S.-G. A 2.4-GHz Ternary Sequence Spread Spectrum OOK Transceiver for Reliable and Ultra-Low Power Sensor Network Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2017, 64, 2976–2987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Cheng, P.-H.; Tsou, C.-F.; Lin, C.-C.; Shieh, G.-S. A 2.4 GHz ISM Band OOK Transceiver with High Energy Efficiency for Biomedical Implantable Applications. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2020, 14, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bhamra, H.; Huang, Y.-W.; Yuan, Q.; Irazoqui, P. An Ultra-Low Power 2.4 GHz Transmitter for Energy Harvested Wireless Sensor Nodes and Biomedical Devices. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Exp. Briefs 2021, 68, 206–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mercier, P.P.; Bandyopadhyay, S.; Lysaght, A.C.; Stankovic, K.M.; Chandrakasan, A.P. A Sub-nW 2.4 GHz Transmitter for Low Data-Rate Sensing Applications. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2014, 49, 1463–1474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, K.; Zappia, E.; Bonan, P.; Coli, F.; Bennardo, L.; Clementoni, M.T.; Pedrelli, V.; Piccolo, D.; Poleva, I.; Salsi, B.; et al. Microwave-Energy-Based Device for the Treatment of Cellulite and Localized Adiposity: Recommendations of the “Onda Coolwaves” International Advisory Board. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 1249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Costantini, E.; Aielli, L.; Reale, M.; Gualdi, G.; Baronio, M.; Monari, P.; Amerio, P. Pulsed Radiofrequency Electromagnetic Fields as Modulators of Inflammation and Wound Healing in Primary Dermal Fibroblasts of Ulcers. Bioengineering 2024, 11, 357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.; Kim, S.; Shin, H. A 1-V 3.8-mW Fractional-N PLL Synthesizer with 25% Duty-Cycle LO Generator in 65 nm CMOS for Bluetooth Applications. J. Semicond. Technol. Sci. 2018, 18, 730–736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.; Shin, H. A 1.9–3.8 GHz Delta-Sigma Fractional-N PLL Frequency Synthesizer With Fast Auto-Calibration of Loop Bandwidth and VCO Frequency. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2012, 47, 665–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paliwal, P.; Laad, P.; Sattineni, M.; Gupta, S. Tradeoffs between Settling Time and Jitter in Phase Locked Loops. In Proceedings of the 56th International Midwest Symposium on Circuits and Systems (MWSCAS), Columbus, OH, USA, 4–7 June 2013; pp. 746–749. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Kim, B. A Low-Noise Fast-Lock Phase-Locked Loop with Adaptive Bandwidth Control. IEEE J. Solid-State Circuits 2000, 35, 1137–1145. [Google Scholar]

- Ba, A.; Chillara, V.K.; Liu, Y.-H.; Kato, H.; Philips, K.; Staszewski, R.B. A 2.4 GHz Class-D Power Amplifier with Conduction Angle Calibration for −50 dBc Harmonic Emissions. In Proceedings of the Radio Frequency Integrated Circuits Symposium (RFIC), Tampa, FL, USA, 1–3 June 2014; pp. 239–242. [Google Scholar]

| Loop Filter Component | Values |

|---|---|

| R2 | 1 kΩ–16 kΩ (1 kΩ step) |

| R3 | 1 kΩ–4 kΩ (1 kΩ step) |

| C1 | 30 pF–180 pF (10 pF step) |

| C2 | 150 pF–900 pF (50 pF step) |

| C3 | 10 pF–13.5 pF (0.5 pF step) |

| This Work | [19] | [20] | [21] | [22] | [23] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TX applications | RF body contouring | Wireless body area network | Wireless sensor network | Biomedical implantable | Wireless sensor network | Biomedical implantable |

| RF band | 2–2.9 GHz | 2.4 GHz | 2.36–2.5 GHz | 2.45 GHz | 2.3–2.7 GHz | 2.1–2.54 GHz |

| Modulation scheme | Pulse mode | OOK | OOK | OOK | OOK/FSK | OOK/FSK |

| Modulation control | 0.5–3.3 kHz (pulse frequency) 2.5–97.5% (duty ratio) | 20 Mbps | 1 Mbps | 20 Mbps | 10 Mbps | 5 Mbps |

| TX output power (dBm) | +11.1 | −14.1 | 0 | −17 | −33.4 | −29 |

| TX efficiency (Pout/PDC) (%) | 14.9 | 18.2 | 27.3 | 3.3 | 0.65 | 0.66 |

| LO generation | Fractional-N PLL | Ring oscillator | Fractional-N PLL | VCO | VCO | VCO |

| Phase noise @ 1 MHz offset (dBc/Hz) | −105 | - | −110 | −115.4 * | −115.5 * | −105 |

| TX power consumption (mW) | 86 | 0.212 | 3.67 | 0.7 | 0.07 | 0.19 |

| Active area (mm2) | 2.16 | 0.0252 | 1.7 | 1.52 | 0.78 | 0.035 |

| Supply voltage | 1 V/2.5 V | 0.6 V | 1 V | 1.2 V | 1.2 V | 0.8 V |

| CMOS technology | 65 nm | 65 nm | 90 nm | 180 nm | 180 nm | 180 nm |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Jeong, G.; Jung, H.; Jang, S.; Jang, J.; Shin, H. A 2.4 GHz CMOS Pulse-Mode Transmitter for RF Body-Contouring Device Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 4826. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244826

Jeong G, Jung H, Jang S, Jang J, Shin H. A 2.4 GHz CMOS Pulse-Mode Transmitter for RF Body-Contouring Device Applications. Electronics. 2025; 14(24):4826. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244826

Chicago/Turabian StyleJeong, Geonwoo, Hwayoung Jung, Sijin Jang, Jaeeun Jang, and Hyunchol Shin. 2025. "A 2.4 GHz CMOS Pulse-Mode Transmitter for RF Body-Contouring Device Applications" Electronics 14, no. 24: 4826. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244826

APA StyleJeong, G., Jung, H., Jang, S., Jang, J., & Shin, H. (2025). A 2.4 GHz CMOS Pulse-Mode Transmitter for RF Body-Contouring Device Applications. Electronics, 14(24), 4826. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics14244826