Genome-Wide Identification of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family and Expression Analysis Under Selenium Stress in Cardamine hupingshanensis

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Genome-Wide Identification of ChAP2/ERF Genes

2.2. Chromosomal Distribution and Phylogenetic Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Genes

2.3. Structure and Functional Characteristics Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Genes

2.4. Analysis of Cis-Acting Elements in the ChAP2/ERF Family

2.5. Collinearity Relationship and Identification of Gene Duplication Events

2.6. Plant Material and Sample Preparation

2.7. Gene Expression Analysis

2.8. GO/KEGG Enrichment Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Targets

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

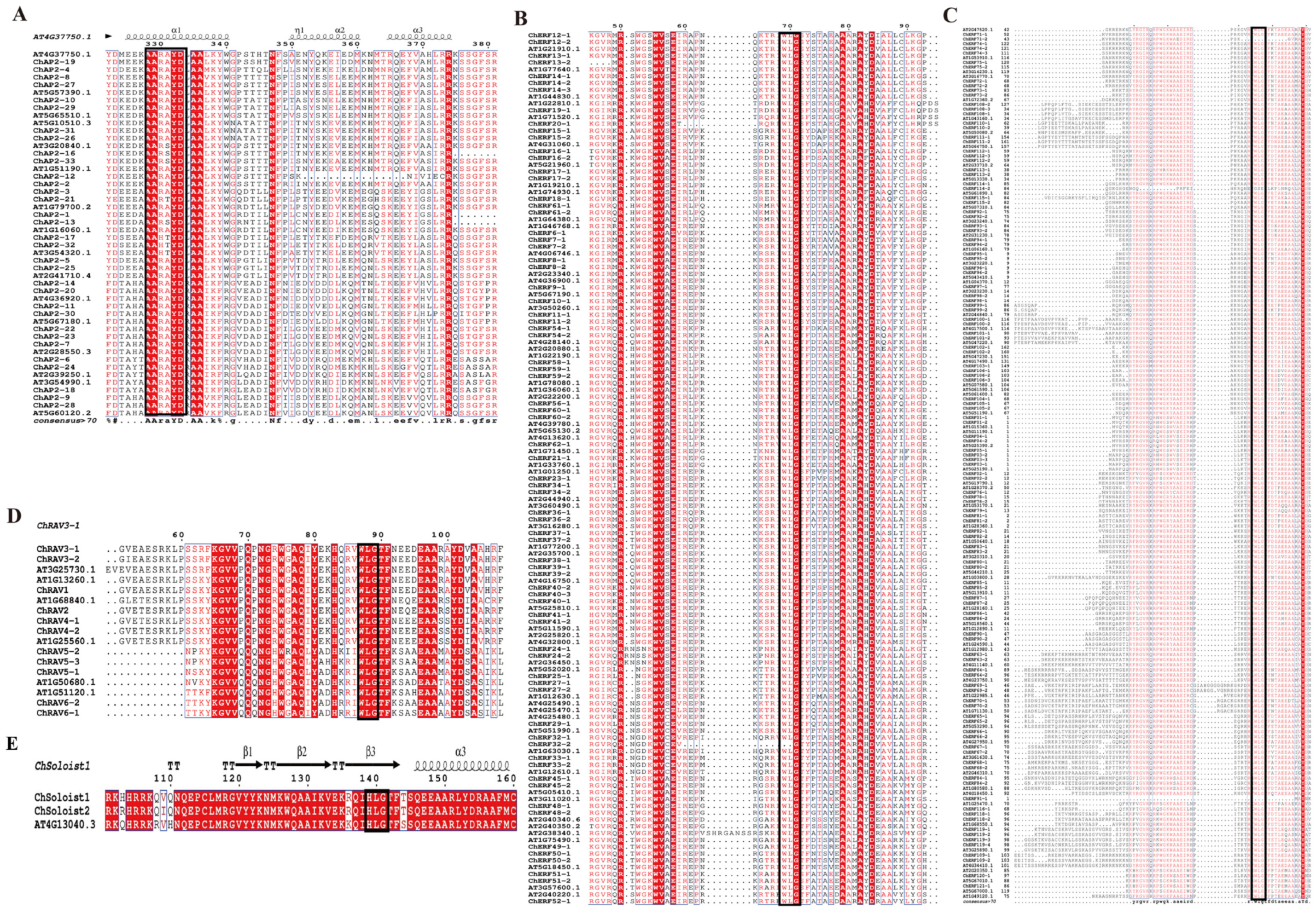

3.1. Identification and Characteristic Analysis of ChAP2/ERF in C. hupingshanensis

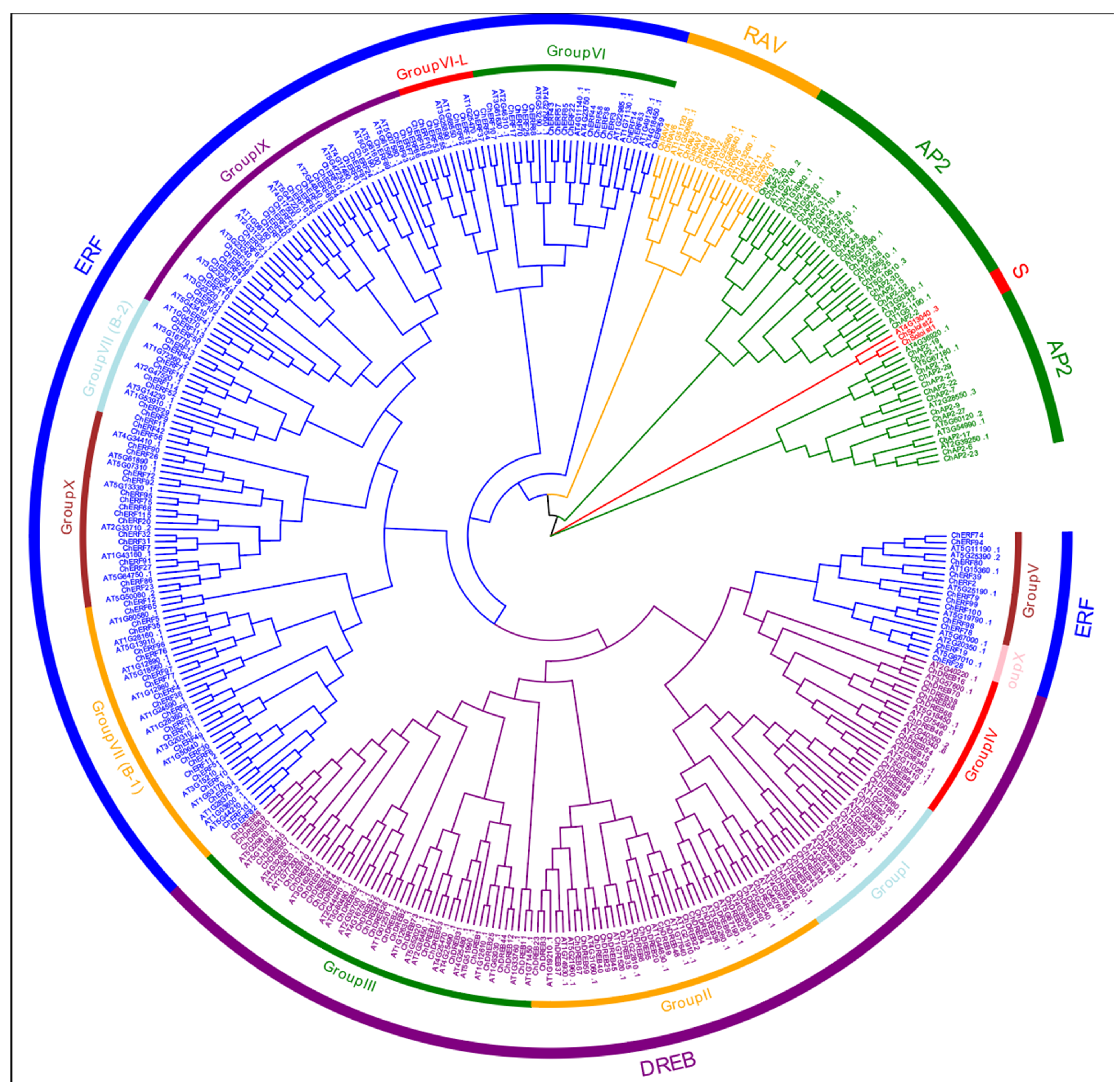

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis of ChAP2/ERF in C. hupingshanensis

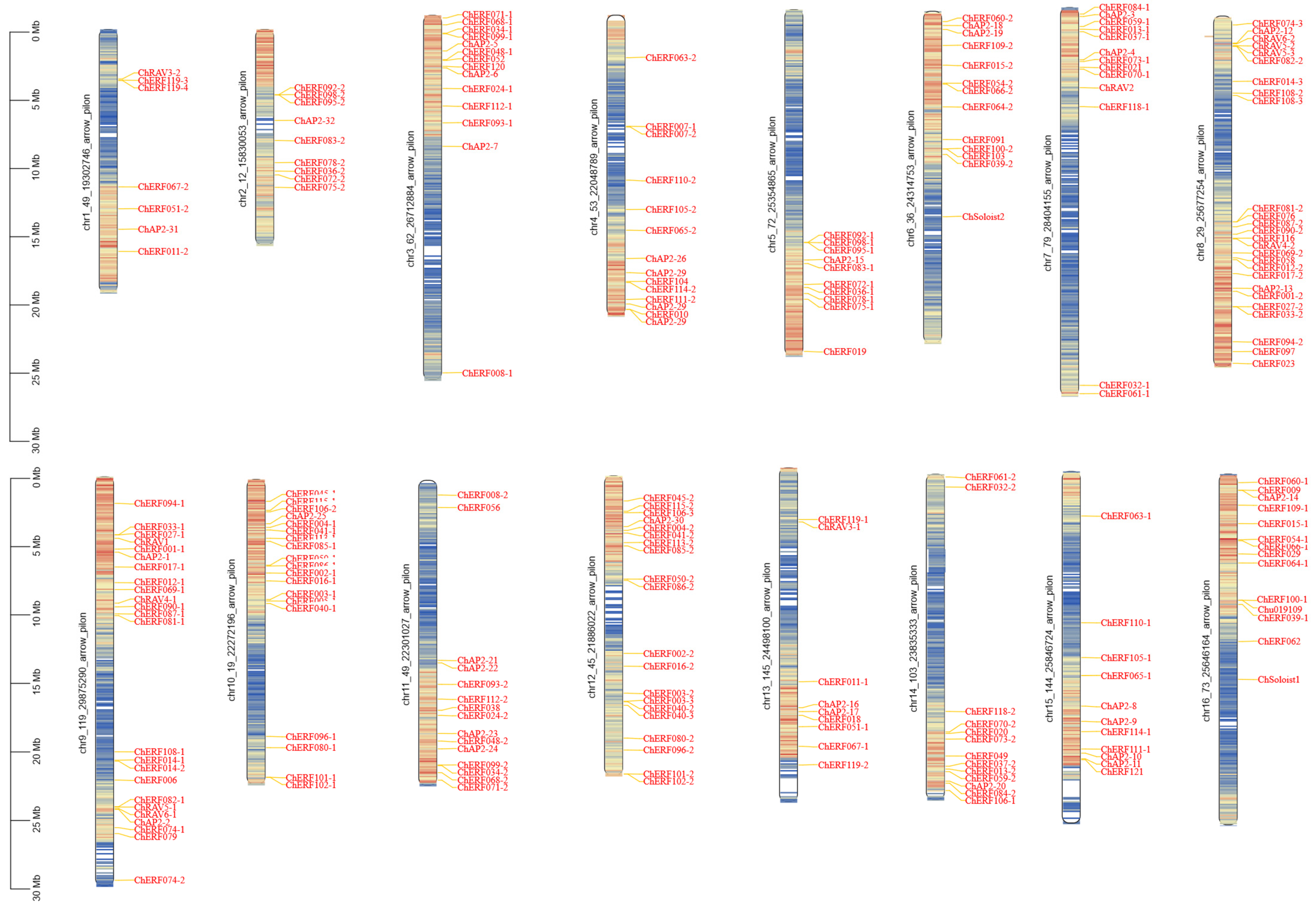

3.3. Chromosomal Distribution and Gene Duplication and Synteny Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Family

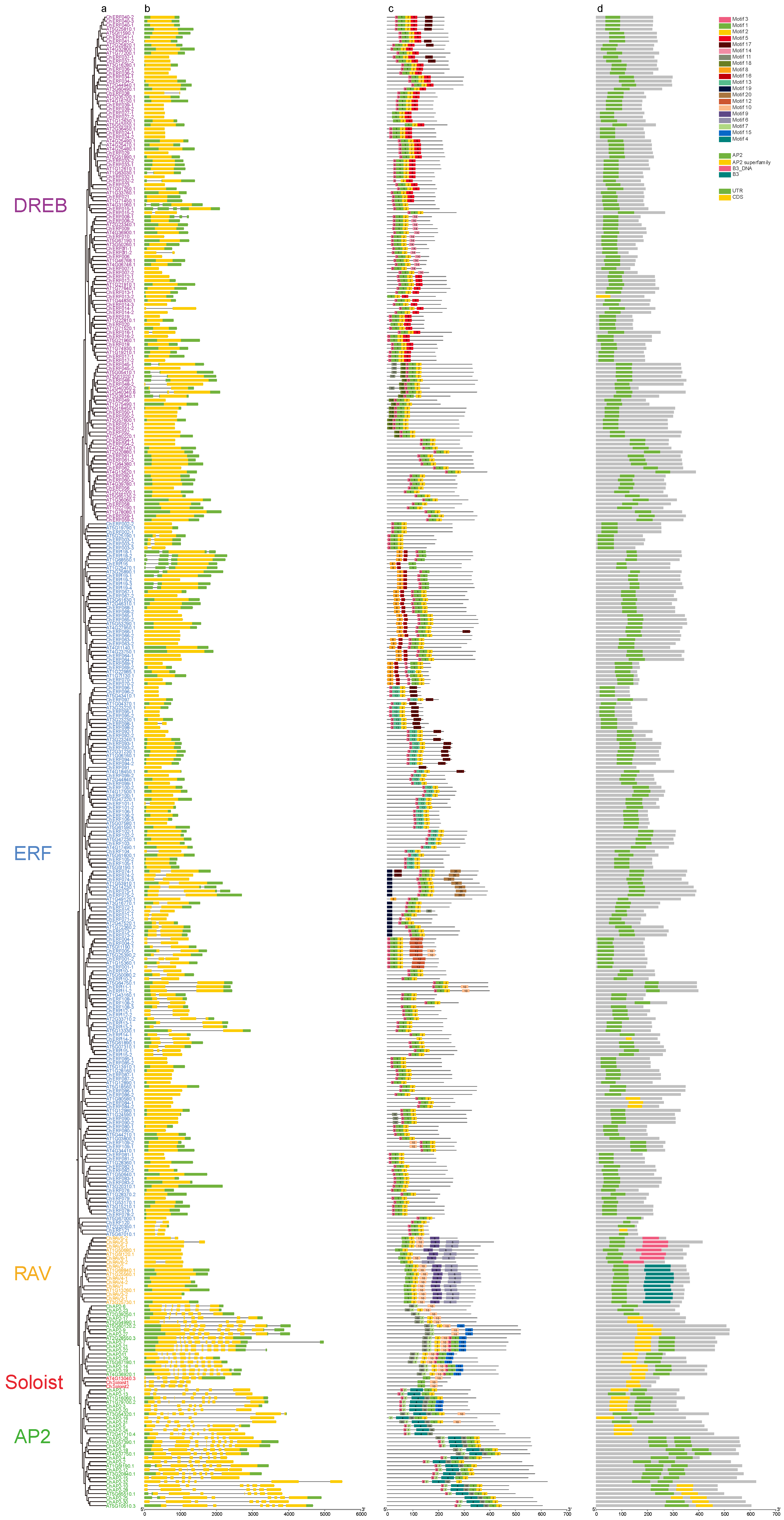

3.4. Structure and Functional Characteristics Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Family

3.5. Putative Promoter Regions Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Family

3.6. Expressions Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Family in Different Tissues Under Se Stress

3.7. Prediction and Analysis of ChAP2/ERF Target Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Xie, Z.; Nolan, T.M.; Jiang, H.; Yin, Y. AP2/ERF transcription factor regulatory networks in hormone and abiotic stress responses in Arabidopsis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, K.; Hou, X.-L.; Xing, G.-M.; Liu, J.-X.; Duan, A.-Q.; Xu, Z.-S.; Li, M.-Y.; Zhuang, J.; Xiong, A.-S. Advances in AP2/ERF super-family transcription factors in plant. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2020, 40, 750–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yue, M.; Zhang, C.; Wu, Z. Research progress in the structural and functional analysis of plant transcription factor AP2/ERF protein family. Biotechnol. Bull. 2022, 38, 11–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Chen, J.; Li, L.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, Y. Research progress on plant AP2/ERF transcription factor family. Transgen. Res. 2018, 34, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Feng, G.; Yang, Z.; Xu, X.; Huang, L.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, X. Genome-wide AP2/ERF gene family analysis reveals the classification, structure, expression profiles and potential function in orchardgrass (Dactylis glomerata). Mol. Biol. Rep. 2020, 47, 5225–5241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Lan, Y.; Lin, M.; Zhou, H.; Ying, S.; Chen, M. Genome-wide identification and transcriptional analysis of AP2/ERF Gene Family in Pearl Millet (Pennisetum glaucum). Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakano, T.; Suzuki, K.; Fujimura, T.; Shinshi, H. Genome-wide analysis of the ERF gene family in Arabidopsis and rice. Plant Physiol. 2006, 140, 411–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghorbani, R.; Zakipour, Z.; Alemzadeh, A.; Razi, H. Genome-wide analysis of AP2/ERF transcription factors family in Brassica napus. Physiol. Mol. Biol. Plants 2020, 26, 1463–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kagaya, Y.; Ohmiya, K.; Hattori, T. RAV1, a novel DNA-binding protein, binds to bipartite recognition sequence through two distinct DNA-binding domains uniquely found in higher plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 470–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakuma, Y.; Liu, Q.; Dubouzet, J.G.; Abe, H.; Shinozaki, K.; Yamaguchi-Shinozaki, K. DNA-binding specificity of the ERF/AP2 domain of Arabidopsis DREBs, transcription factors involved in dehydration-and cold-inducible gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2002, 290, 998–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohme-Takagi, M.; Shinshi, H. Ethylene-inducible DNA binding proteins that interact with an ethylene-responsive element. Plant Cell 1995, 7, 173–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Zhou, G.; Chen, S.; Jia, Z.; Zhang, S.; Ren, M.; He, F. Genome-wide analysis of the AP2/ERF gene family in Tritipyrum and the response of TtERF_B2-50 in salt-tolerance. BMC Genom. 2023, 24, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, P.J.; Broadley, M.R. Biofortification of crops with seven mineral elements often lacking in human diets–iron, zinc, copper, calcium, magnesium, selenium and iodine. New Phytol. 2009, 182, 49–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Xiao, C.; Qiu, T.; Deng, J.; Cheng, H.; Cong, X.; Cheng, S.; Rao, S.; Zhang, Y. Selenium regulates antioxidant, photosynthesis, and cell permeability in plants under various abiotic stresses: A review. Plants 2022, 12, 44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montanari, S.; Salinitro, M.; Simoni, A.; Ciavatta, C.; Tassoni, A. Foraging for selenium: A comparison between hyperaccumulator and non-accumulator plant species. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Gupta, S. An overview of selenium uptake, metabolism, and toxicity in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 7, 2074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, L.; Zhu, Y.; Lin, Z.-Q.; Banuelos, G.; Li, W.; Yin, X. A novel selenocystine-accumulating plant in selenium-mine drainage area in Enshi, China. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e65615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, L.; Zhao, J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, Y.; Li, B.; Li, Y.-F. Translocation and transformation of selenium in hyperaccumulator plant Cardamine enshiensis from Enshi, Hubei, China. Plant Soil 2018, 425, 577–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Tang, Q.; Wu, M.; Mou, D.; Liu, H.; Wang, S.; Zhang, C.; Ding, L.; Luo, J. Comparative transcriptomics provides novel insights into the mechanisms of selenium tolerance in the hyperaccumulator plant Cardamine hupingshanensis. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 2789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Luo, G.; Fan, Z.; Xiao, Z.; Lu, Y.; Xiao, Q.; Hou, Z.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Whole genome identification, molecular docking and expression analysis of enzymes involved in the selenomethionine cycle in Cardamine hupingshanensis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.K.; Agarwal, P.; Reddy, M.; Sopory, S.K. Role of DREB transcription factors in abiotic and biotic stress tolerance in plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2006, 25, 1263–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An Integrative Toolkit Developed for Interactive Analyses of Big Biological Data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gasteiger, E.; Gattiker, A.; Hoogland, C.; Ivanyi, I.; Appel, R.D.; Bairoch, A. ExPASy: The proteomics server for in-depth protein knowledge and analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, X.; Gouet, P. Deciphering key features in protein structures with the new ENDscript server. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014, 42, W320–W324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of Relative Gene Expression Data Using Real-Time Quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swift, M.L. GraphPad prism, data analysis, and scientific graphing. J. Chem. Inf. Comput. Sci. 1997, 37, 411–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wood, B. Adobe Illustrator Classroom in a Book (2021 Release); Adobe Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, W.; Li, F.; Ling, L.; Liu, A. Genome-wide survey and expression profiles of the AP2/ERF family in castor bean (Ricinus communis L.). BMC Genom. 2013, 14, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, S.; Wang, D. AP2/ERF transcription factors for tolerance to both biotic and abiotic stress factors in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 2023, 16, 105–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, C.H.; Yeo, H.J.; Park, Y.E.; Baek, S.-A.; Kim, J.K.; Park, S.U. Transcriptome Analysis and Metabolic Profiling of Lycoris radiata. Biology 2019, 8, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Hu, L.; Jiang, W. Understanding AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Responses and Tolerance to Various Abiotic Stresses in Plants: A Comprehensive Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Yan, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, M.; Leng, J.; Yu, Q.; Liu, L.; Xue, D.; Zhang, D.; Ding, Z. GmERF13 mediates salt inhibition of nodulation through interacting with GmLBD16a in soybean. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Licausi, F.; Giorgi, F.M.; Zenoni, S.; Osti, F.; Pezzotti, M.; Perata, P. Genomic and transcriptomic analysis of the AP2/ERF superfamily in Vitis vinifera. BMC Genom. 2010, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.S.; Chen, M.; Li, L.C.; Ma, Y.Z. Functions and application of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in crop improvement F. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2011, 53, 570–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, L.; Yang, J.; Liu, C.; Chen, Z.; Yao, Z.; Cao, S. Overexpression of ethylene response factor ERF96 gene enhances selenium tolerance in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 149, 294–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, Y.-G.; Pilon-Smits, E.A.; Zhao, F.-J.; Williams, P.N.; Meharg, A.A. Selenium in higher plants: Understanding mechanisms for biofortification and phytoremediation. Trends Plant Sci. 2009, 14, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, Z.; Rao, X.; Zhang, R.; Gu, S.; Shen, Q.; Wu, H.; Lv, S.; Xie, L.; Li, X.; Wang, X. Genome-wide identification, evolution, and expression analyses of AP2/ERF family transcription factors in Erianthus fulvus. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 7102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Srivastava, R.; Kumar, R. The expanding roles of APETALA2/Ethylene Responsive Factors and their potential applications in crop improvement. Brief. Funct. Genom. 2019, 18, 240–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jofuku, K.D.; Den Boer, B.; Van Montagu, M.; Okamuro, J.K. Control of Arabidopsis flower and seed development by the homeotic gene APETALA2. Plant Cell 1994, 6, 1211–1225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jisha, V.; Dampanaboina, L.; Vadassery, J.; Mithöfer, A.; Kappara, S.; Ramanan, R. Overexpression of an AP2/ERF type transcription factor OsEREBP1 confers biotic and abiotic stress tolerance in rice. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0127831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, X.; Li, J.-J.; Chen, Y.; Yang, J.-Q.; Chen, X.-Y. Genome-wide analysis of the WRKY gene family and its response to abiotic stress in buckwheat (Fagopyrum tataricum). Open Life Sci. 2019, 14, 80–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, S.; Nie, Y.; Shen, Y.; Ye, X.; Wu, W. Convergent evolution of AP2/ERF III and IX subfamilies through recurrent polyploidization and tandem duplication during eudicot adaptation to paleoenvironmental changes. Plant Commun. 2022, 3, 100420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Lu, W.; Zhao, Z.; Hao, W.; Du, R.; Li, Z.; Wang, Z.; Lv, X.; Wang, J.; Liang, D.; et al. Abscisic acid promotes selenium absorption, metabolism and toxicity via stress-related phytohormones regulation in Cyphomandra betacea Sendt. (Solanum betaceum Cav.). J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 461, 132642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.-H.; Wang, M.; Zhang, H.-X.; Khan, A.; Wei, A.-M.; Luo, D.-X.; Gong, Z.-H. Genome-wide identification of the AP2/ERF transcription factor family in pepper (Capsicum annuum L.). Genome 2018, 61, 663–674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Cappa, J.J.; Harris, J.P.; Edger, P.P.; Zhou, W.; Pires, J.C.; Adair, M.; Unruh, S.A.; Simmons, M.P.; Schiavon, M. Transcriptome-wide comparison of selenium hyperaccumulator and nonaccumulator Stanleya species provides new insight into key processes mediating the hyperaccumulation syndrome. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2018, 16, 1582–1594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.; Jin, Y.-M.; Wu, T.; Hu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jiang, W.; Du, X. OsDREB2B, an AP2/ERF transcription factor, negatively regulates plant height by conferring GA metabolism in rice. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 1007811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Wang, Q.-Y.; Cheng, X.-G.; Xu, Z.-S.; Li, L.-C.; Ye, X.-G.; Xia, L.-Q.; Ma, Y.-Z. GmDREB2, a soybean DRE-binding transcription factor, conferred drought and high-salt tolerance in transgenic plants. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2007, 353, 299–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gilmour, S.J.; Sebolt, A.M.; Salazar, M.P.; Everard, J.D.; Thomashow, M.F. Overexpression of the Arabidopsis CBF3Transcriptional Activator Mimics Multiple Biochemical Changes Associated with Cold Acclimation1. Plant Physiol. 2000, 124, 1854–1865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Liu, W.; Wan, L.; Li, F.; Dai, L.; Li, D.; Zhang, Z.; Huang, R. Functional analyses of ethylene response factor JERF3 with the aim of improving tolerance to drought and osmotic stress in transgenic rice. Transgen. Res. 2010, 19, 809–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Deng, Z.; Liang, C.; Sun, H.; Li, D.; Song, J.; Zhang, S.; Wang, R. Genome-wide analysis of RAV transcription factors and functional characterization of anthocyanin-biosynthesis-related RAV genes in pear. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terry, N.; Zayed, A.; De Souza, M.; Tarun, A. Selenium in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2000, 51, 401–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bathe, U.; Tissier, A. Cytochrome P450 enzymes: A driving force of plant diterpene diversity. Phytochemistry 2019, 161, 149–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, H.; Lin, W.; Jiao, H.; Liu, J.; Chan, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Chen, T. Uptake, transport, and metabolism of selenium and its protective effects against toxic metals in plants: A review. Metallomics 2021, 13, mfab040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batista-Silva, W.; Heinemann, B.; Rugen, N.; Nunes-Nesi, A.; Araújo, W.L.; Braun, H.P.; Hildebrandt, T.M. The role of amino acid metabolism during abiotic stress release. Plant Cell Environ. 2019, 42, 1630–1644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinemann, B.; Hildebrandt, T.M. The role of amino acid metabolism in signaling and metabolic adaptation to stress-induced energy deficiency in plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2021, 72, 4634–4645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene ID | Gene Name | DNA Length (bp) | Mature Protein (aa) | pI | MW (kDa) | Grand Average of Hydropathicity (GRAVY) | Subcellular Localization |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chu001362 | ChAP2-1 | 972 | 323 | 5.27 | 36.89 | −0.887 | nucleus |

| Chu003566 | ChAP2-2 | 1575 | 524 | 6.4 | 57.31 | −0.685 | nucleus |

| Chu004239 | ChAP2-3 | 939 | 312 | 6.28 | 35.53 | −1.022 | nucleus |

| Chu004905 | ChAP2-4 | 1209 | 402 | 5.73 | 45.90 | −0.972 | nucleus |

| Chu007518 | ChAP2-5 | 1266 | 421 | 8.36 | 46.55 | −0.809 | nucleus |

| Chu007782 | ChAP2-6 | 975 | 324 | 9.23 | 36.69 | −0.719 | nucleus |

| Chu008869 | ChAP2-7 | 1413 | 470 | 5.81 | 51.93 | −0.785 | nucleus |

| Chu011886 | ChAP2-8 | 1689 | 562 | 6.83 | 61.12 | −0.646 | nucleus |

| Chu012136 | ChAP2-9 | 1560 | 519 | 6.58 | 56.74 | −0.515 | chloroplast |

| Chu012654 | ChAP2-10 | 1422 | 473 | 5.95 | 52.63 | −0.685 | nucleus |

| Chu012750 | ChAP2-11 | 813 | 270 | 8.58 | 30.62 | −0.728 | nucleus |

| Chu013398 | ChAP2-12 | 1653 | 550 | 6.28 | 60.20 | −0.676 | nucleus |

| Chu015708 | ChAP2-13 | 942 | 313 | 5.43 | 35.82 | −0.993 | nucleus |

| Chu017361 | ChAP2-14 | 1299 | 432 | 6.6 | 47.55 | −0.728 | nucleus |

| Chu022107 | ChAP2-15 | 1647 | 548 | 5.83 | 59.90 | −0.732 | nucleus |

| Chu025581 | ChAP2-16 | 1050 | 349 | 4.87 | 40.00 | −0.667 | nucleus |

| Chu025647 | ChAP2-17 | 1050 | 349 | 9.39 | 39.10 | −0.566 | nucleus |

| Chu026752 | ChAP2-18 | 1635 | 544 | 7.14 | 60.55 | −0.694 | nucleus |

| Chu026813 | ChAP2-19 | 1269 | 422 | 7.75 | 46.56 | −0.788 | nucleus |

| Chu032490 | ChAP2-20 | 963 | 320 | 7.78 | 36.56 | −0.981 | nucleus |

| Chu033656 | ChAP2-21 | 1389 | 462 | 6.05 | 50.98 | −0.705 | nucleus |

| Chu033670 | ChAP2-22 | 1389 | 462 | 6.05 | 51.01 | −0.71 | nucleus |

| Chu034677 | ChAP2-23 | 924 | 307 | 9.86 | 34.71 | −0.59 | nucleus |

| Chu034915 | ChAP2-24 | 1305 | 434 | 8.35 | 48.02 | −0.76 | nucleus |

| Chu036333 | ChAP2-25 | 1704 | 567 | 9.35 | 63.89 | −0.22 | extracellular |

| Chu040760 | ChAP2-26 | 1671 | 556 | 6.86 | 60.28 | −0.615 | nucleus |

| Chu041002 | ChAP2-27 | 1557 | 518 | 6.71 | 56.63 | −0.525 | chloroplast |

| Chu041501 | ChAP2-28 | 1419 | 472 | 5.99 | 52.57 | −0.651 | nucleus |

| Chu041593 | ChAP2-29 | 1053 | 350 | 6.96 | 39.43 | −0.797 | nucleus |

| Chu042594 | ChAP2-30 | 1749 | 582 | 6.13 | 65.10 | −0.832 | nucleus |

| Chu046603 | ChAP2-31 | 1236 | 411 | 5.36 | 46.22 | −0.788 | chloroplast |

| Chu048859 | ChAP2-32 | 1872 | 623 | 6.86 | 68.11 | −0.738 | nucleus |

| Chu001298 | ChERF001-1 | 585 | 194 | 6.44 | 21.08 | −0.521 | nucleus |

| Chu015769 | ChERF001-2 | 600 | 199 | 6.34 | 21.69 | −0.607 | nucleus |

| Chu037160 | ChERF002-1 | 762 | 253 | 6.75 | 28.62 | −0.861 | nucleus |

| Chu043609 | ChERF002-2 | 759 | 252 | 6.75 | 28.62 | −0.861 | nucleus |

| Chu037560 | ChERF003-1 | 573 | 190 | 6.59 | 21.63 | −0.607 | mitochondrion |

| Chu044073 | ChERF003-2 | 558 | 185 | 7.71 | 21.01 | −0.555 | mitochondrion |

| Chu044144 | ChERF003-3 | 459 | 152 | 9.58 | 17.13 | −0.632 | chloroplast |

| Chu036394 | ChERF004-1 | 570 | 189 | 5.89 | 21.49 | −0.636 | nucleus |

| Chu042653 | ChERF004-2 | 552 | 183 | 9.12 | 20.74 | −0.531 | chloroplast |

| Chu037575 | ChERF005-1 | 567 | 188 | 9.32 | 21.21 | −0.637 | nucleus |

| Chu003246 | ChERF006 | 486 | 161 | 9.6 | 17.96 | −0.671 | nucleus |

| Chu039895 | ChERF007-1 | 399 | 132 | 10.22 | 14.80 | −0.57 | peroxisome |

| Chu039897 | ChERF007-2 | 486 | 161 | 9.9 | 18.26 | −0.485 | peroxisome |

| Chu009972 | ChERF008-1 | 519 | 172 | 9.42 | 18.75 | −0.534 | chloroplast |

| Chu032769 | ChERF008-2 | 498 | 165 | 9.21 | 17.93 | −0.515 | chloroplast |

| Chu017359 | ChERF009 | 585 | 194 | 7.77 | 21.23 | −0.83 | chloroplast |

| Chu041592 | ChERF010 | 546 | 181 | 5.87 | 20.67 | −1.103 | nucleus |

| Chu025179 | ChERF011-1 | 486 | 161 | 9.35 | 17.99 | −0.672 | chloroplast |

| Chu046959 | ChERF011-2 | 381 | 126 | 10.12 | 13.93 | −0.544 | chloroplast |

| Chu001878 | ChERF012-1 | 687 | 228 | 6.44 | 25.58 | −0.709 | nucleus |

| Chu015209 | ChERF012-2 | 693 | 230 | 6.29 | 25.61 | −0.636 | nucleus |

| Chu004423 | ChERF013-1 | 690 | 229 | 6.18 | 25.52 | −0.498 | mitochondrion |

| Chu032317 | ChERF013-2 | 564 | 187 | 4.9 | 20.58 | −0.326 | mitochondrion |

| Chu003149 | ChERF014-1 | 693 | 230 | 7.64 | 25.19 | −0.304 | chloroplast |

| Chu003152 | ChERF014-2 | 642 | 213 | 6.27 | 23.16 | −0.365 | chloroplast |

| Chu013827 | ChERF014-3 | 624 | 207 | 5.18 | 22.75 | −0.385 | chloroplast |

| Chu017917 | ChERF015-1 | 609 | 202 | 5.29 | 22.52 | −0.276 | chloroplast |

| Chu027412 | ChERF015-2 | 807 | 268 | 8.48 | 29.87 | −0.171 | chloroplast |

| Chu037292 | ChERF016-1 | 753 | 250 | 4.86 | 28.28 | −0.68 | chloroplast |

| Chu043768 | ChERF016-2 | 651 | 216 | 4.48 | 24.54 | −0.88 | cytosol |

| Chu001638 | ChERF017-1 | 570 | 189 | 4.97 | 21.45 | −0.752 | cytosol |

| Chu015431 | ChERF017-2 | 573 | 190 | 4.89 | 21.59 | −0.764 | cytosol |

| Chu025699 | ChERF018 | 576 | 191 | 4.61 | 21.67 | −0.517 | nucleus |

| Chu023666 | ChERF019 | 423 | 140 | 6.03 | 15.41 | −0.549 | nucleus |

| Chu031751 | ChERF020 | 426 | 141 | 4.94 | 15.34 | −0.579 | nucleus |

| Chu005013 | ChERF021 | 564 | 187 | 5.22 | 20.69 | −0.543 | nucleus |

| Chu017022 | ChERF023 | 561 | 186 | 5.49 | 20.54 | −0.458 | nucleus |

| Chu008081 | ChERF024-1 | 570 | 189 | 4.83 | 20.40 | −0.358 | nucleus |

| Chu034416 | ChERF024-2 | 570 | 189 | 4.83 | 20.34 | −0.381 | chloroplast |

| Chu001044 | ChERF027-1 | 564 | 187 | 5.11 | 20.31 | −0.563 | nucleus |

| Chu016014 | ChERF027-2 | 546 | 181 | 5.07 | 19.75 | −0.598 | nucleus |

| Chu018445 | ChERF029 | 663 | 220 | 4.73 | 24.69 | −0.422 | nucleus |

| Chu006742 | ChERF032-1 | 555 | 184 | 5.25 | 21.05 | −0.654 | nucleus |

| Chu030151 | ChERF032-2 | 522 | 173 | 4.99 | 19.53 | −0.472 | nucleus |

| Chu001043 | ChERF033-1 | 618 | 205 | 5.25 | 23.38 | −0.632 | nucleus |

| Chu016015 | ChERF033-2 | 612 | 203 | 5.4 | 23.23 | −0.653 | nucleus |

| Chu007208 | ChERF034-1 | 894 | 297 | 5 | 32.18 | −0.557 | chloroplast |

| Chu035202 | ChERF034-2 | 882 | 293 | 5.38 | 31.59 | −0.541 | chloroplast |

| Chu022529 | ChERF036-1 | 726 | 241 | 4.66 | 26.66 | −0.592 | nucleus |

| Chu049311 | ChERF036-2 | 666 | 221 | 4.96 | 24.62 | −0.556 | nucleus |

| Chu004460 | ChERF037-1 | 681 | 226 | 5.05 | 24.89 | −0.581 | nucleus |

| Chu032276 | ChERF037-2 | 714 | 237 | 4.86 | 25.97 | −0.573 | nucleus |

| Chu034335 | ChERF038 | 561 | 186 | 5.75 | 20.75 | −0.571 | nucleus |

| Chu019175 | ChERF039-1 | 534 | 177 | 7.88 | 19.63 | −0.65 | nucleus |

| Chu028753 | ChERF039-2 | 534 | 177 | 6.97 | 19.61 | −0.655 | nucleus |

| Chu037610 | ChERF040-1 | 663 | 220 | 5.46 | 24.05 | −0.533 | nucleus |

| Chu044149 | ChERF040-2 | 666 | 221 | 5.3 | 24.12 | −0.552 | nucleus |

| Chu044192 | ChERF040-3 | 666 | 221 | 5.3 | 24.12 | −0.552 | nucleus |

| Chu036436 | ChERF041-1 | 711 | 236 | 5.29 | 26.09 | −0.531 | nucleus |

| Chu042692 | ChERF041-2 | 720 | 239 | 5.17 | 26.38 | −0.464 | nucleus |

| Chu035916 | ChERF045-1 | 990 | 329 | 5.12 | 37.10 | −0.885 | nucleus |

| Chu042145 | ChERF045-2 | 996 | 331 | 4.87 | 37.43 | −0.901 | nucleus |

| Chu007652 | ChERF048-1 | 1056 | 351 | 4.63 | 38.96 | −0.79 | nucleus |

| Chu034792 | ChERF048-2 | 1023 | 340 | 4.65 | 37.74 | −0.81 | nucleus |

| Chu032111 | ChERF049 | 582 | 193 | 5.69 | 21.32 | −0.736 | nucleus |

| Chu037031 | ChERF050-1 | 909 | 302 | 7.04 | 33.06 | −0.83 | nucleus |

| Chu043367 | ChERF050-2 | 900 | 299 | 8.55 | 33.20 | −0.816 | nucleus |

| Chu025902 | ChERF051-1 | 840 | 279 | 5.43 | 31.67 | −0.784 | nucleus |

| Chu046288 | ChERF051-2 | 840 | 279 | 5.44 | 31.75 | −0.804 | nucleus |

| Chu007663 | ChERF052 | 999 | 332 | 6.75 | 36.23 | −0.756 | nucleus |

| Chu018190 | ChERF054-1 | 849 | 282 | 7.1 | 32.35 | −0.994 | nucleus |

| Chu027704 | ChERF054-2 | 846 | 281 | 5.57 | 32.33 | −0.962 | nucleus |

| Chu032874 | ChERF056 | 813 | 270 | 5.3 | 30.47 | −0.65 | nucleus |

| Chu015183 | ChERF058 | 873 | 290 | 5.89 | 31.87 | −0.614 | nucleus |

| Chu004386 | ChERF059-1 | 1050 | 349 | 6.46 | 38.19 | −0.568 | nucleus |

| Chu032351 | ChERF059-2 | 1020 | 339 | 6.51 | 37.20 | −0.529 | nucleus |

| Chu017239 | ChERF060-1 | 813 | 270 | 4.98 | 30.55 | −0.725 | nucleus |

| Chu026680 | ChERF060-2 | 795 | 264 | 5.25 | 30.04 | −0.763 | nucleus |

| Chu006861 | ChERF061-1 | 987 | 328 | 8.94 | 35.99 | −0.389 | nucleus |

| Chu030039 | ChERF061-2 | 1002 | 333 | 7.72 | 36.56 | −0.377 | nucleus |

| Chu019578 | ChERF062 | 1017 | 338 | 9.36 | 38.24 | −0.513 | nucleus |

| Chu010616 | ChERF063-1 | 981 | 326 | 4.63 | 35.95 | −0.378 | cytosol |

| Chu039513 | ChERF063-2 | 930 | 309 | 4.59 | 33.97 | −0.397 | nucleus |

| Chu018603 | ChERF064-1 | 999 | 332 | 5.17 | 36.78 | −0.527 | nucleus |

| Chu028120 | ChERF064-2 | 1029 | 342 | 5.25 | 37.66 | −0.475 | nucleus |

| Chu011482 | ChERF065-1 | 1038 | 345 | 4.59 | 39.52 | −0.723 | nucleus |

| Chu040384 | ChERF065-2 | 1059 | 352 | 4.61 | 40.24 | −0.759 | nucleus |

| Chu018210 | ChERF066-1 | 978 | 325 | 4.64 | 37.19 | −0.666 | nucleus |

| Chu027724 | ChERF066-2 | 993 | 330 | 4.81 | 37.73 | −0.737 | nucleus |

| Chu026223 | ChERF067-1 | 933 | 310 | 4.8 | 35.00 | −0.725 | nucleus |

| Chu045962 | ChERF067-2 | 909 | 302 | 4.97 | 34.39 | −0.648 | nucleus |

| Chu007083 | ChERF068-1 | 924 | 307 | 5.22 | 34.72 | −0.682 | nucleus |

| Chu035331 | ChERF068-2 | 924 | 307 | 5.21 | 34.78 | −0.7 | nucleus |

| Chu001977 | ChERF069-1 | 501 | 166 | 9.8 | 18.23 | −0.671 | nucleus |

| Chu015113 | ChERF069-2 | 510 | 169 | 9.77 | 18.73 | −0.733 | mitochondrion |

| Chu005043 | ChERF070-1 | 504 | 167 | 9.45 | 18.63 | −0.729 | cytosol |

| Chu031722 | ChERF070-2 | 492 | 163 | 9.57 | 18.08 | −0.634 | chloroplast |

| Chu006952 | ChERF071-1 | 585 | 194 | 8.77 | 21.93 | −0.668 | cytosol |

| Chu035447 | ChERF071-2 | 525 | 174 | 10.23 | 20.01 | −0.498 | chloroplast |

| Chu022480 | ChERF072-1 | 726 | 241 | 5.25 | 26.70 | −0.568 | nucleus |

| Chu049363 | ChERF072-2 | 558 | 185 | 10.31 | 21.22 | −0.297 | chloroplast |

| Chu004926 | ChERF073-1 | 846 | 281 | 5.55 | 31.66 | −0.705 | nucleus |

| Chu031831 | ChERF073-2 | 828 | 277 | 5.26 | 31.21 | −0.801 | nucleus |

| Chu003796 | ChERF074-1 | 1065 | 354 | 4.99 | 39.60 | −0.716 | nucleus |

| Chu004086 | ChERF074-2 | 1050 | 349 | 4.99 | 39.07 | −0.691 | nucleus |

| Chu013182 | ChERF074-3 | 999 | 332 | 5.31 | 37.43 | −0.747 | nucleus |

| Chu022738 | ChERF075-1 | 1173 | 390 | 4.97 | 43.71 | −0.878 | nucleus |

| Chu049533 | ChERF075-2 | 1158 | 385 | 5.01 | 43.12 | −0.864 | nucleus |

| Chu014670 | ChERF076 | 498 | 165 | 5.55 | 18.31 | −0.388 | chloroplast |

| Chu022641 | ChERF078-1 | 663 | 220 | 8.99 | 23.38 | −0.499 | nucleus |

| Chu049188 | ChERF078-2 | 669 | 222 | 9.19 | 23.53 | −0.449 | nucleus |

| Chu003875 | ChERF079 | 588 | 195 | 9.77 | 21.30 | −0.597 | nucleus |

| Chu038484 | ChERF080-1 | 597 | 198 | 9.75 | 21.58 | −0.387 | nucleus |

| Chu044580 | ChERF080-2 | 588 | 195 | 10.04 | 21.27 | −0.313 | nucleus |

| Chu002356 | ChERF081-1 | 543 | 180 | 9.83 | 19.80 | −0.377 | nucleus |

| Chu014669 | ChERF081-2 | 570 | 189 | 9.83 | 20.82 | −0.554 | nucleus |

| Chu003526 | ChERF082-1 | 693 | 230 | 8.86 | 25.64 | −0.748 | chloroplast |

| Chu013438 | ChERF082-2 | 705 | 234 | 9.05 | 26.25 | −0.651 | chloroplast |

| Chu022161 | ChERF083-1 | 768 | 255 | 8.83 | 27.59 | −0.691 | chloroplast |

| Chu048935 | ChERF083-2 | 765 | 254 | 8.93 | 27.53 | −0.728 | chloroplast |

| Chu004193 | ChERF084-1 | 792 | 263 | 7.75 | 28.83 | −0.476 | nucleus |

| Chu032529 | ChERF084-2 | 735 | 244 | 9.22 | 27.16 | −0.51 | nucleus |

| Chu036620 | ChERF085-1 | 627 | 208 | 5.17 | 23.27 | −0.855 | nucleus |

| Chu042903 | ChERF085-2 | 636 | 211 | 5.2 | 23.69 | −0.838 | nucleus |

| Chu037042 | ChERF086-1 | 1044 | 347 | 6.03 | 38.24 | −0.62 | nucleus |

| Chu043382 | ChERF086-2 | 990 | 329 | 6.08 | 36.15 | −0.578 | nucleus |

| Chu002336 | ChERF087-1 | 756 | 251 | 5.08 | 28.64 | −0.99 | nucleus |

| Chu014738 | ChERF087-2 | 756 | 251 | 5.07 | 28.56 | 1.057 | nucleus |

| Chu002223 | ChERF090-1 | 930 | 309 | 6.84 | 34.20 | −0.577 | nucleus |

| Chu014844 | ChERF090-2 | 930 | 309 | 6.31 | 34.01 | −0.588 | nucleus |

| Chu028561 | ChERF091 | 471 | 156 | 4.94 | 17.79 | −0.484 | nucleus |

| Chu021871 | ChERF092-1 | 660 | 219 | 5.09 | 24.82 | −0.653 | nucleus |

| Chu048632 | ChERF092-2 | 579 | 192 | 6.01 | 22.03 | −0.804 | nucleus |

| Chu008600 | ChERF093-1 | 762 | 253 | 5.42 | 28.24 | −0.719 | nucleus |

| Chu033935 | ChERF093-2 | 756 | 251 | 6.02 | 27.93 | −0.72 | nucleus |

| Chu000495 | ChERF094-1 | 753 | 250 | 4.82 | 28.01 | −0.641 | nucleus |

| Chu016638 | ChERF094-2 | 699 | 232 | 5.29 | 26.26 | −0.684 | nucleus |

| Chu021873 | ChERF095-1 | 417 | 138 | 5.3 | 15.66 | −0.925 | nucleus |

| Chu048634 | ChERF095-2 | 420 | 139 | 5.13 | 15.69 | −0.949 | nucleus |

| Chu038373 | ChERF096-1 | 390 | 129 | 6.42 | 14.08 | −0.961 | nucleus |

| Chu044712 | ChERF096-2 | 660 | 129 | 6.43 | 14.16 | −0.982 | nucleus |

| Chu016812 | ChERF097 | 600 | 199 | 9.89 | 22.84 | −0.808 | nucleus |

| Chu021872 | ChERF098-1 | 483 | 160 | 9.39 | 18.63 | −0.617 | nucleus |

| Chu048633 | ChERF098-2 | 435 | 144 | 8.85 | 16.58 | −1.102 | nucleus |

| Chu007217 | ChERF099-1 | 705 | 234 | 5.62 | 26.23 | −0.669 | nucleus |

| Chu035193 | ChERF099-2 | 672 | 223 | 5.62 | 25.05 | −0.728 | nucleus |

| Chu019108 | ChERF100-1 | 792 | 263 | 8.98 | 28.91 | −0.523 | nucleus |

| Chu028675 | ChERF100-2 | 762 | 253 | 9.02 | 27.87 | −0.601 | nucleus |

| Chu038804 | ChERF101-1 | 702 | 233 | 8.68 | 25.86 | −0.598 | nucleus |

| Chu045021 | ChERF101-2 | 741 | 246 | 5.88 | 26.68 | −0.473 | nucleus |

| Chu038805 | ChERF102-1 | 933 | 310 | 5.28 | 35.04 | −0.618 | nucleus |

| Chu045022 | ChERF102-2 | 927 | 308 | 5.27 | 34.70 | −0.568 | nucleus |

| Chu028676 | ChERF103 | 912 | 303 | 5.06 | 34.31 | −0.611 | nucleus |

| Chu041142 | ChERF104 | 687 | 228 | 8.57 | 25.67 | −0.878 | nucleus |

| Chu011284 | ChERF105-1 | 654 | 217 | 8.93 | 24.14 | −0.659 | nucleus |

| Chu040176 | ChERF105-2 | 654 | 217 | 8.91 | 24.35 | −0.675 | nucleus |

| Chu032637 | ChERF106-1 | 606 | 201 | 4.89 | 22.64 | −0.692 | nucleus |

| Chu036108 | ChERF106-2 | 606 | 201 | 4.89 | 22.70 | −0.674 | nucleus |

| Chu042345 | ChERF106-3 | 612 | 203 | 4.84 | 22.82 | −0.67 | nucleus |

| Chu003113 | ChERF108-1 | 552 | 183 | 6.08 | 20.77 | −0.721 | nucleus |

| Chu013905 | ChERF108-2 | 831 | 276 | 6.24 | 31.53 | −0.603 | plasma membrane |

| Chu013923 | ChERF108-3 | 522 | 183 | 8.65 | 20.79 | −0.633 | nucleus |

| Chu017615 | ChERF109-1 | 783 | 260 | 5.19 | 28.89 | −0.695 | nucleus |

| Chu027078 | ChERF109-2 | 810 | 269 | 5.44 | 29.75 | −0.752 | nucleus |

| Chu011080 | ChERF110-1 | 684 | 227 | 5.61 | 24.64 | −0.529 | nucleus |

| Chu040012 | ChERF110-2 | 612 | 203 | 6.21 | 22.27 | −0.567 | nucleus |

| Chu012581 | ChERF111-1 | 1176 | 391 | 6.81 | 43.23 | −0.915 | nucleus |

| Chu041424 | ChERF111-2 | 1194 | 397 | 7.89 | 43.57 | −0.84 | nucleus |

| Chu008354 | ChERF112-1 | 631 | 209 | 7.74 | 23.34 | −0.812 | nucleus |

| Chu034160 | ChERF112-2 | 597 | 198 | 6.59 | 22.23 | −0.622 | nucleus |

| Chu036565 | ChERF113-1 | 648 | 215 | 9.22 | 24.68 | −1.175 | nucleus |

| Chu042845 | ChERF113-2 | 654 | 217 | 6.85 | 24.54 | −1.072 | nucleus |

| Chu012300 | ChERF114-1 | 747 | 248 | 5.25 | 27.77 | −1.081 | nucleus |

| Chu041160 | ChERF114-2 | 720 | 239 | 5.19 | 26.54 | −1.139 | nucleus |

| Chu036082 | ChERF115-1 | 816 | 271 | 7.75 | 30.40 | −0.921 | nucleus |

| Chu042319 | ChERF115-2 | 780 | 259 | 6.52 | 29.16 | −1.062 | nucleus |

| Chu014898 | ChERF116 | 867 | 288 | 4.76 | 31.90 | −0.408 | nucleus |

| Chu005439 | ChERF118-1 | 996 | 331 | 4.74 | 36.72 | −0.507 | nucleus |

| Chu031489 | ChERF118-2 | 1002 | 333 | 4.62 | 36.91 | −0.555 | nucleus |

| Chu024224 | ChERF119-1 | 984 | 327 | 5.04 | 35.97 | −0.427 | nucleus |

| Chu026442 | ChERF119-2 | 584 | 327 | 5.04 | 36.06 | −0.443 | nucleus |

| Chu045481 | ChERF119-3 | 1005 | 334 | 5.05 | 37.12 | −0.485 | nucleus |

| Chu045483 | ChERF119-4 | 1020 | 339 | 4.99 | 37.34 | −0.432 | nucleus |

| Chu007757 | ChERF120 | 492 | 163 | 9.13 | 18.09 | −0.891 | nucleus |

| Chu012767 | ChERF121 | 483 | 160 | 7.72 | 17.39 | −0.811 | nucleus |

| Chu001099 | ChRAV1 | 1020 | 339 | 9.19 | 37.97 | −0.666 | nucleus |

| Chu005275 | ChRAV2 | 1053 | 350 | 9.5 | 39.44 | −0.543 | nucleus |

| Chu024242 | ChRAV3-1 | 1026 | 341 | 9.14 | 38.58 | −0.681 | nucleus |

| Chu045469 | ChRAV3-2 | 1029 | 342 | 8.64 | 38.58 | −0.635 | nucleus |

| Chu002169 | ChRAV4-1 | 1092 | 363 | 9.29 | 40.44 | −0.656 | nucleus |

| Chu014907 | ChRAV4-2 | 1095 | 364 | 9.1 | 40.82 | −0.673 | nucleus |

| Chu003530 | ChRAV5-1 | 1089 | 362 | 7.03 | 41.50 | −0.642 | nucleus |

| Chu013433 | ChRAV5-2 | 819 | 272 | 9.08 | 31.33 | −0.713 | nucleus |

| Chu013434 | ChRAV5-3 | 1245 | 414 | 8.47 | 47.80 | −0.583 | nucleus |

| Chu003556 | ChRAV6-1 | 1020 | 339 | 6.57 | 38.99 | −0.738 | nucleus |

| Chu013407 | ChRAV6-2 | 804 | 267 | 7.69 | 30.76 | −0.596 | cytoskeleton |

| Chu019716 | ChSoloist1 | 702 | 233 | 9.36 | 27.49 | −1.118 | nucleus |

| Chu029199 | ChSoloist2 | 645 | 214 | 9.82 | 25.14 | −1.038 | chloroplast |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Deng, N.; Zeng, X.; Liu, J.; Chen, S.; Lu, Y.; Xiang, Z.; Hou, Z.; Tang, Q.; Zhou, Y. Genome-Wide Identification of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family and Expression Analysis Under Selenium Stress in Cardamine hupingshanensis. Biology 2025, 14, 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121686

Deng N, Zeng X, Liu J, Chen S, Lu Y, Xiang Z, Hou Z, Tang Q, Zhou Y. Genome-Wide Identification of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family and Expression Analysis Under Selenium Stress in Cardamine hupingshanensis. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121686

Chicago/Turabian StyleDeng, Nanrong, Xixi Zeng, Jialin Liu, Shengcai Chen, Yanke Lu, Zhixin Xiang, Zhi Hou, Qiaoyu Tang, and Yifeng Zhou. 2025. "Genome-Wide Identification of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family and Expression Analysis Under Selenium Stress in Cardamine hupingshanensis" Biology 14, no. 12: 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121686

APA StyleDeng, N., Zeng, X., Liu, J., Chen, S., Lu, Y., Xiang, Z., Hou, Z., Tang, Q., & Zhou, Y. (2025). Genome-Wide Identification of the AP2/ERF Transcription Factor Family and Expression Analysis Under Selenium Stress in Cardamine hupingshanensis. Biology, 14(12), 1686. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121686