Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Genetic Evolution of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Small Mammals from Southwestern Yunnan, China

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

2.2. Sample Collection and Viral RNA Extraction

2.3. Detection of HEV RNA

2.4. Statistical Analysis

2.5. High-Throughput Sequencing and Whole Genome Acquisition

2.6. Bioinformatics Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Sample Collection and HEV Detection

3.2. Analysis of Factors Influencing Rat HEV Infection in Small Mammals

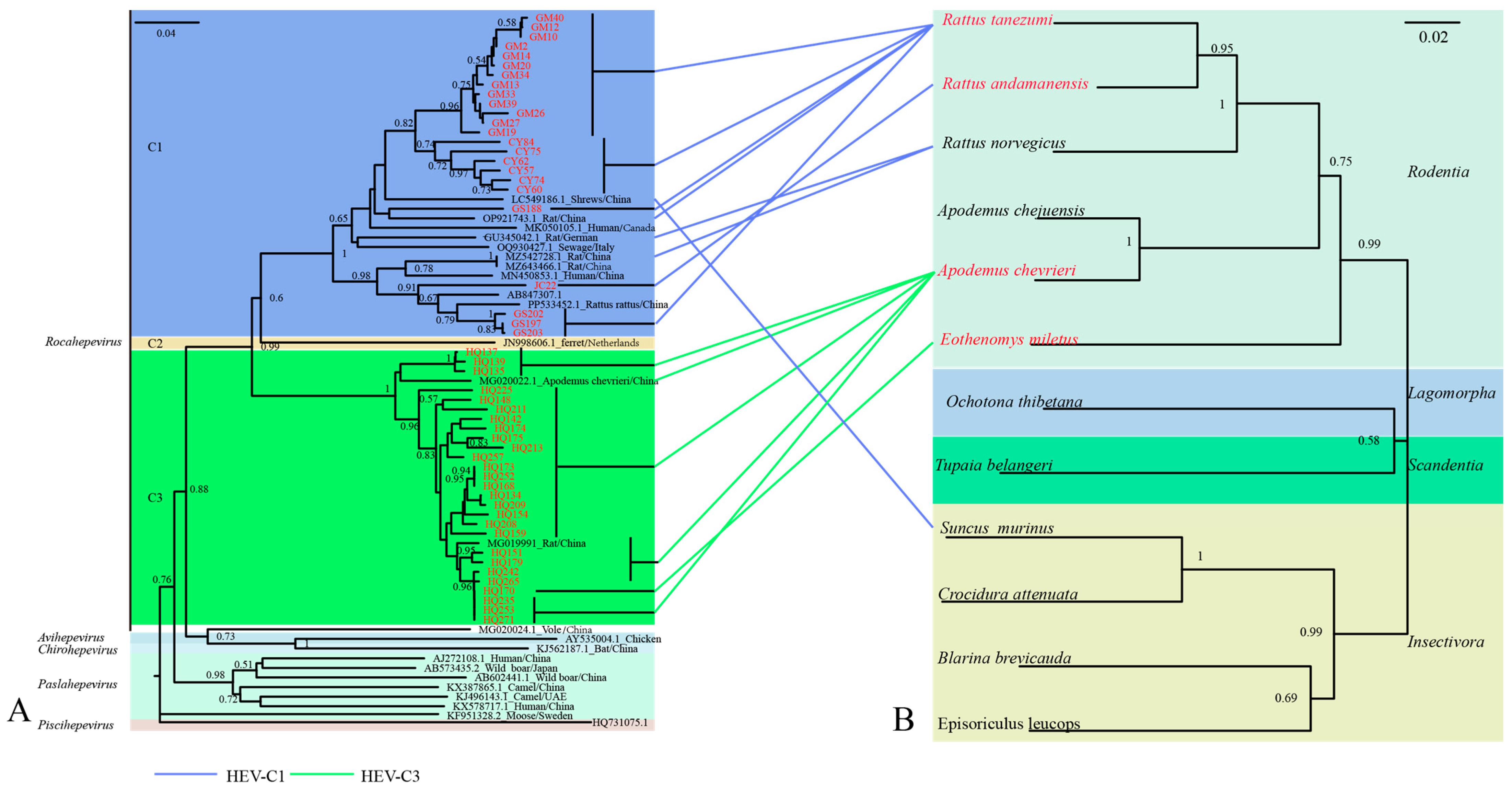

3.3. Phylogenetic Analysis and Co-Evolution with Hosts of Rat HEV

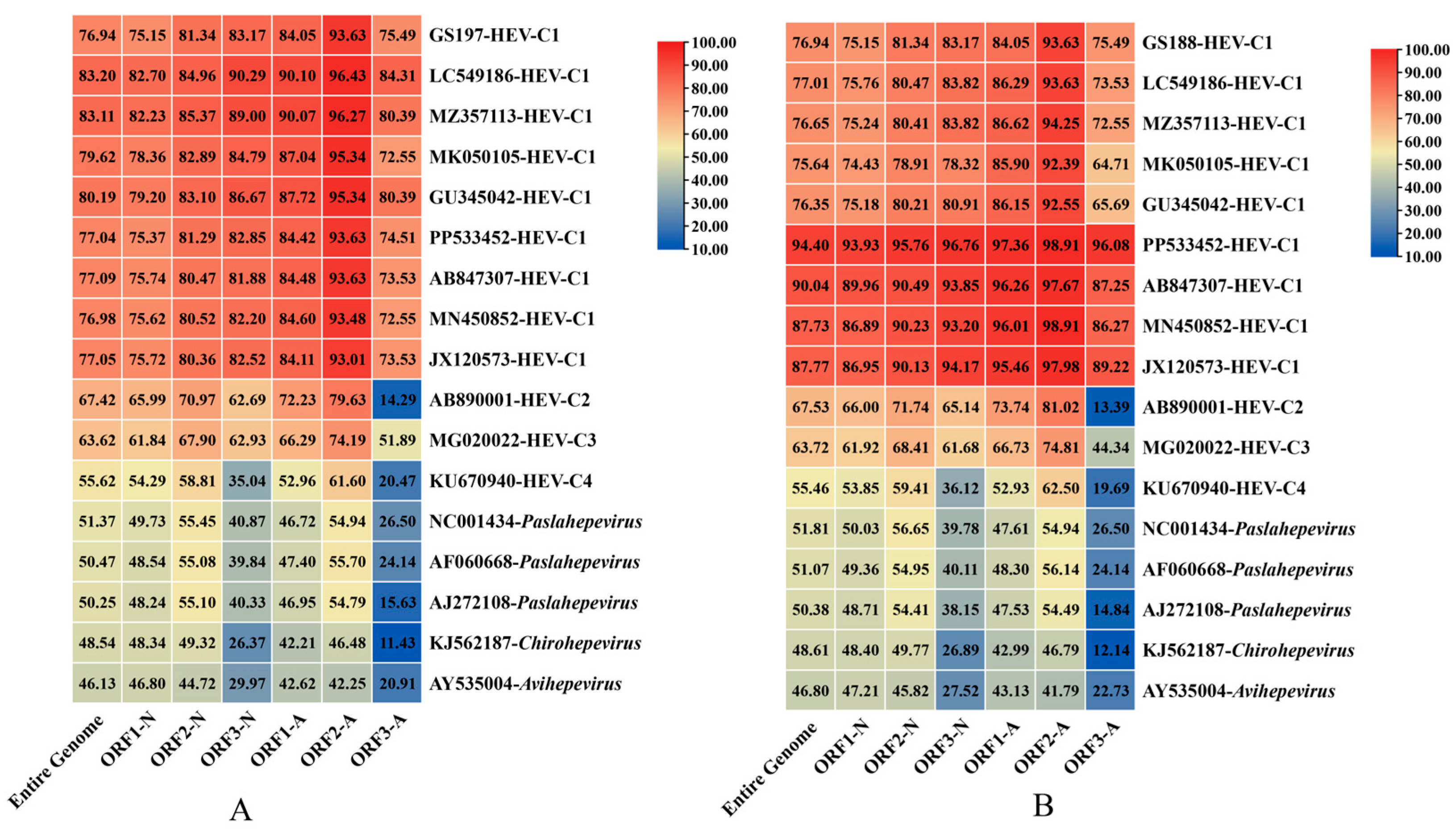

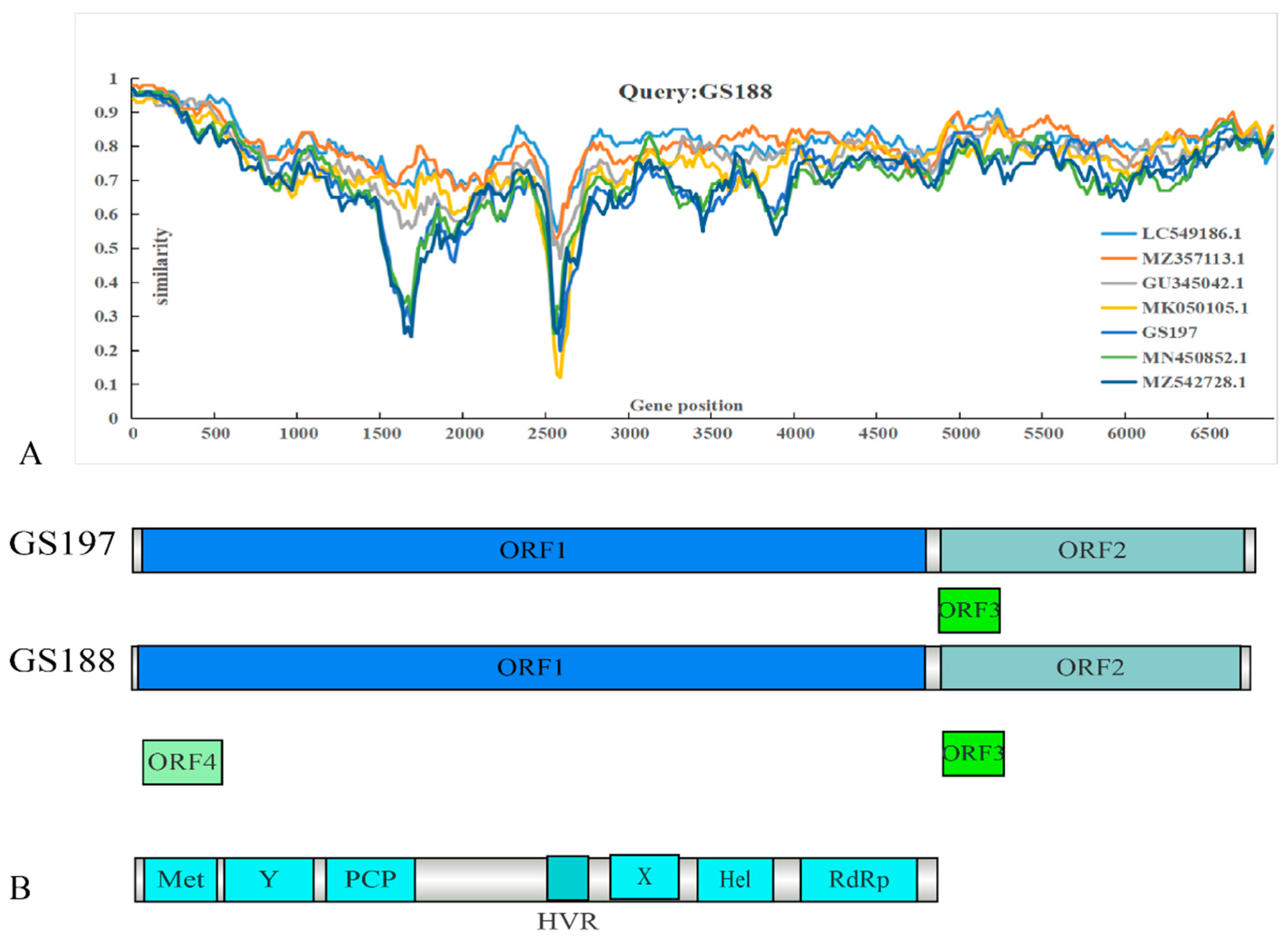

3.4. Genomic Structure and Similarity Comparison of Two Full-Length Rat HEV Sequences from Rattus tanezumi

3.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of Two Rat HEV Strains from R. tanezumi

3.6. Temporal Evolution of Two Rat HEV Strains from R. tanezumi

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, B.; Meng, X.J. Structural and molecular biology of hepatitis E virus. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1907–1916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nimgaonkar, I.; Ding, Q.; Schwartz, R.E.; Ploss, A. Hepatitis E virus: Advances and challenges. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2018, 15, 96–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Liu, J.; Li, Y.; Su, J.; Ma, Z.; Bramer, W.M.; Cao, W.; de Man, R.A.; Peppelenbosch, M.P.; Pan, Q. The global epidemiology of hepatitis E virus infection: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Liver Int. 2020, 40, 1516–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Velavan, T.P.; Pallerla, S.R.; Johne, R.; Todt, D.; Steinmann, E.; Schemmerer, M.; Wenzel, J.J.; Hofmann, J.; Shih, J.W.K.; Wedemeyer, H.; et al. Hepatitis E: An update on One Health and clinical medicine. Liver Int. 2021, 41, 1462–1473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamar, N.; Abravanel, F.; Lhomme, S.; Rostaing, L.; Izopet, J. Hepatitis E virus: Chronic infection, extra-hepatic manifestations, and treatment. Clin. Res. Hepatol. Gastroenterol. 2015, 39, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Li, W.; Heffron, C.L.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Wang, B.; LeRoith, T.; Meng, X.J. Antiviral resistance and barrier integrity at the maternal-fetal interface restrict hepatitis E virus from crossing the placental barrier. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2501128122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Tian, D.; Sooryanarain, H.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Heffron, C.L.; Hassebroek, A.M.; Meng, X.J. Two mutations in the ORF1 of genotype 1 hepatitis E virus enhance virus replication and may associate with fulminant hepatic failure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2207503119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, D.; Li, W.; Heffron, C.L.; Wang, B.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Sooryanarain, H.; Hassebroek, A.M.; Clark-Deener, S.; LeRoith, T.; Meng, X.J. Hepatitis E virus infects brain microvascular endothelial cells, crosses the blood-brain barrier, and invades the central nervous system. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2022, 119, e2201862119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, W.; Wen, Y.; Xiong, Y.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, M.; Chen, Q. The prevalence and genomic characteristics of hepatitis E virus in murine rodents and house shrews from several regions in China. BMC Vet. Res. 2018, 14, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Cai, C.L.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, W.H.; Zhuo, F.; Shi, Z.L.; Yang, X.L. Detection and characterization of three zoonotic viruses in wild rodents and shrews from Shenzhen city, China. Virol. Sin. 2017, 32, 290–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Li, W.; Zhou, J.-H.; Li, B.; Zhang, W.; Yang, W.-H.; Pan, H.; Wang, L.-X.; Bock, C.T.; Shi, Z.-L.; et al. Chevrier’s Field Mouse (Apodemus chevrieri) and Père David’s Vole (Eothenomys melanogaster) in China Carry Orthohepeviruses that form Two Putative Novel Genotypes Within the Species Orthohepevirus C. Virol. Sin. 2018, 33, 44–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.-L.; Ma, X.-H.; Nan, X.-W.; Wang, J.-L.; Zhao, J.; Sun, X.-M.; Li, J.-S.; Zheng, G.-S.; Duan, Z.-J. Diversity of hepatitis E viruses in rats in yunnan province and the inner mongolia autonomous region of China. Viruses 2025, 17, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.B.; Simmonds, P.; Members of the International Committee on the Taxonomy of Viruses Hepeviridae Study Group; Jameel, S.; Emerson, S.U.; Harrison, T.J.; Meng, X.-J.; Okamoto, H.; Van der Poel, W.H.M.; Purdy, M.A. Consensus proposals for classification of the family Hepeviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 2015, 96, 1191–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bai, H.; Li, W.; Guan, D.; Su, J.; Ke, C.; Ami, Y.; Suzaki, Y.; Takeda, N.; Muramatsu, M.; Li, T.-C. Characterization of a Novel Rat Hepatitis E Virus Isolated from an Asian Musk Shrew (Suncus murinus). Viruses 2020, 12, 715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, M.; Yue, C.; Yang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.; Yang, S.; Shen, Q.; Su, X.; Qi, D.; et al. Viral metagenomics unveiled extensive communications of viruses within giant pandas and their associated organisms in the same ecosystem. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 820, 153317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, B.; Harms, D.; Yang, X.L.; Bock, C.T. Orthohepevirus C: An Expanding Species of Emerging Hepatitis E Virus Variants. Pathogens 2020, 9, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johne, R.; Heckel, G.; Plenge-Bonig, A.; Kindler, E.; Maresch, C.; Reetz, J.; Schielke, A.; Ulrich, R.G. Novel hepatitis E virus genotype in Norway rats, Germany. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2010, 16, 1452–1455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Yip, C.C.Y.; Wu, S.; Cai, J.; Zhang, A.J.; Leung, K.H.; Chung, T.W.H.; Chan, J.F.W.; Chan, W.M.; Teng, J.L.L.; et al. Rat Hepatitis E Virus as Cause of Persistent Hepatitis after Liver Transplant. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2018, 24, 2241–2250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, S.; Yip, C.C.Y.; Lo, K.H.Y.; Wu, S.; Situ, J.; Chew, N.F.S.; Leung, K.H.; Chan, H.S.Y.; Wong, S.C.Y.; Leung, A.W.S.; et al. Hepatitis E Virus Species C Infection in Humans, Hong Kong. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2022, 75, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gomez, J.; Pereira, S.; Rivero-Calle, I.; Perez, A.B.; Viciana, I.; Casares-Jimenez, M.; Rios-Munoz, L.; Rivero-Juarez, A.; Aguilera, A.; Rivero, A. Acute Hepatitis in Children Due to Rat Hepatitis E Virus. J. Pediatr. 2024, 273, 114125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Casares-Jimenez, M.; Rivero-Juarez, A.; Lopez-Lopez, P.; Montes, M.L.; Navarro-Soler, R.; Peraire, J.; Espinosa, N.; Aleman-Valls, M.R.; Garcia-Garcia, T.; Caballero-Gomez, J.; et al. Rat hepatitis E virus (Rocahepevirus ratti) in people living with HIV. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2295389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mueller, L.J.; Schmidt, M.L.; Ciesek, S.; Corman, V.M.; Berlin/Frankfurt/Munich Group for the Study of Rat HEV. Presence but low detection rate of rat hepatitis E virus in patients in Germany 2022–2024. J. Hepatol. 2025, 83, e146–e148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Situ, J.; Tang, T.; Li, Z.; Chen, D.; Ho, S.S.-F.; Chung, H.-L.; Wong, T.-C.; Liang, Y.; Deng, C.; et al. Prevalence of rocahepevirus ratti (rat hepatitis E virus) in humans and rats in China. JHEP Rep. 2025, 7, 101370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamaguchi, J.; Orf, G.S.; Perez, L.J.; Phoompoung, P.; Chirakarnjanakorn, S.; Suputtamongkol, Y.; Cloherty, G.A.; Berg, M.G. First Evidence of Spillover of Rocahepevirus ratti Into Humans in Thailand. Transbound. Emerg. Dis. 2025, 2025, 9954682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Li, G.; Yin, J.; Fan, J.; Liu, T.; Wu, H.; Huang, Y.; Huang, W.; et al. Substantial spillover burden of rat hepatitis E virus in humans. Nat. Commun. 2025, 16, 4038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kane, Y.; Tendu, A.; Li, R.; Chen, Y.; Mastriani, E.; Lan, J.; Catherine Hughes, A.; Berthet, N.; Wong, G. Viral diversity in wild and urban rodents of Yunnan Province, China. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2024, 13, 2290842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morcatty, T.Q.; Pereyra, P.E.R.; Ardiansyah, A.; Imron, M.A.; Hedger, K.; Campera, M.; Nekaris, K.A.; Nijman, V. Risk of Viral Infectious Diseases from Live Bats, Primates, Rodents and Carnivores for Sale in Indonesian Wildlife Markets. Viruses 2022, 14, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, F.L.; Wang, B.; Han, P.Y.; Li, B.; Si, H.R.; Zhu, Y.; Yin, H.M.; Zong, L.D.; Tang, Y.; Shi, Z.L.; et al. Identification of novel rodent and shrew orthohepeviruses sheds light on hepatitis E virus evolution. Zool. Res. 2025, 46, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, W.; Yang, C.; Bi, Y.; Long, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Huang, F. Characterization of hepatitis E virus infection in tree shrew (Tupaia belangeri chinensis). BMC Infect. Dis. 2016, 16, 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Yang, X.L.; Li, W.; Zhu, Y.; Ge, X.Y.; Zhang, L.B.; Zhang, Y.Z.; Bock, C.T.; Shi, Z.L. Detection and genome characterization of four novel bat hepadnaviruses and a hepevirus in China. Virol. J. 2017, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Kong, Y.C.; Tian, J.W.; Han, P.Y.; Wu, S.; He, C.J.; Ren, T.L.; Wang, B.; Qin, L.; Zhang, Y.Z. Molecular Epidemiology and Genetic Diversity of Orientia tsutsugamushi From Patients and Small Mammals in Xiangyun County, Yunnan Province, China. Vet. Med. Sci. 2025, 11, e70573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, P.Y.; Xu, F.H.; Tian, J.W.; Zhao, J.Y.; Yang, Z.; Kong, W.; Wang, B.; Guo, L.J.; Zhang, Y.Z. Molecular Prevalence, Genetic Diversity, and Tissue Tropism of Bartonella Species in Small Mammals from Yunnan Province, China. Animals 2024, 14, 1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drexler, J.F.; Seelen, A.; Corman, V.M.; Fumie Tateno, A.; Cottontail, V.; Melim Zerbinati, R.; Gloza-Rausch, F.; Klose, S.M.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Oppong, S.K.; et al. Bats worldwide carry hepatitis E virus-related viruses that form a putative novel genus within the family Hepeviridae. J. Virol. 2012, 86, 9134–9147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, D.P.; Murrell, B.; Golden, M.; Khoosal, A.; Muhire, B. RDP4: Detection and analysis of recombination patterns in virus genomes. Virus Evol. 2015, 1, vev003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suchard, M.A.; Lemey, P.; Baele, G.; Ayres, D.L.; Drummond, A.J.; Rambaut, A. Bayesian phylogenetic and phylodynamic data integration using BEAST 1.10. Virus Evol. 2018, 4, vey016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, S.J.; Borlang, J.; Himsworth, C.G.; Pearl, D.L.; Weese, J.S.; Dibernardo, A.; Osiowy, C.; Nasheri, N.; Jardine, C.M. Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Norway Rats, Ontario, Canada, 2018–2021. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2023, 29, 1890–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Li, B.; Yu, B.; Hu, L.; Zhou, L.; Yin, J.; Lu, Y. Genomic characterization of Rocahepevirus ratti hepatitis E virus genotype C1 in Yunnan province of China. Virus Res. 2024, 341, 199321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Subramaniam, S.; Tian, D.; Mahsoub, H.M.; Heffron, C.L.; Meng, X.J. Phosphorylation of Ser711 residue in the hypervariable region of zoonotic genotype 3 hepatitis E virus is important for virus replication. mBio 2024, 15, e0263524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, Q.; Hu, B.; Yao, X.; Gan, M.; Chen, D.; Zhang, N.; Wei, J.; Cai, K.; Zheng, Z. Prevalence and molecular characterization of hepatitis E virus (HEV) from wild rodents in Hubei Province, China. Infect. Genet. Evol. J. Mol. Epidemiol. Evol. Genet. Infect. Dis. 2024, 121, 105602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gómez, J.; Fajardo-Alonso, T.; Rios-Muñoz, L.; Cuadrado-Matías, R.; Somoano, A.; Panadero, R.; Casares-Jiménez, M.; García-Bocanegra, I.; Ruiz, L.; Beato-Benítez, A.; et al. Occurrence and genetic diversity of the zoonotic rat hepatitis E virus in small mammal species, spain. Vet. Res. 2025, 56, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ryll, R.; Bernstein, S.; Heuser, E.; Schlegel, M.; Dremsek, P.; Zumpe, M.; Wolf, S.; Pépin, M.; Bajomi, D.; Müller, G.; et al. Detection of rat hepatitis E virus in wild Norway rats (Rattus norvegicus) and Black rats (Rattus rattus) from 11 European countries. Vet. Microbiol. 2017, 208, 58–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, K.E.; Patel, N.G.; Levy, M.A.; Storeygard, A.; Balk, D.; Gittleman, J.L.; Daszak, P. Global trends in emerging infectious diseases. Nature 2008, 451, 990–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meerburg, B.G.; Singleton, G.R.; Kijlstra, A. Rodent-borne diseases and their risks for public health. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 35, 221–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Sabato, L.; Monini, M.; Galuppi, R.; Dini, F.M.; Ianiro, G.; Vaccari, G.; Ostanello, F.; Di Bartolo, I. Investigating the Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) Diversity in Rat Reservoirs from Northern Italy. Pathogens 2024, 13, 633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panajotov, J.; Schilling-Loeffler, K.; Mehl, C.; Meneghini, D.; Fickel, J.; Beyer, J.; von Graffenried, T.; Heckel, G.; Ulrich, R.G.; Johne, R. Long-term circulation and molecular evolution of rat hepatitis E virus in wild Norway rat populations from Berlin, Germany. Infect. Genet. Evol. 2025, 135, 105841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yadav, K.K.; Boley, P.A.; Lee, C.M.; Khatiwada, S.; Jung, K.; Laocharoensuk, T.; Hofstetter, J.; Wood, R.; Hanson, J.; Kenney, S.P. Rat hepatitis E virus cross-species infection and transmission in pigs. PNAS Nexus 2024, 3, pgae259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rios-Munoz, L.; Gonzalvez, M.; Caballero-Gomez, J.; Castro-Scholten, S.; Casares-Jimenez, M.; Agullo-Ros, I.; Corona-Mata, D.; Garcia-Bocanegra, I.; Lopez-Lopez, P.; Fajardo, T.; et al. Detection of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Pigs, Spain, 2023. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 2024, 30, 823–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero-Gomez, J.; Garcia-Bocanegra, I.; Cano-Terriza, D.; Casares-Jimenez, M.; Jimenez-Ruiz, S.; Risalde, M.A.; Rios-Munoz, L.; Rivero-Juarez, A.; Rivero, A. Zoonotic rat hepatitis E virus infection in pigs: Farm prevalence and public health relevance. Porc. Health Manag. 2025, 11, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Luo, C.F.; Xiang, R.; Min, J.M.; Shao, Z.T.; Zhao, Y.L.; Chen, L.; Huang, L.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, S.S.; et al. Host taxonomy and environment shapes insectivore viromes and viral spillover risks in Southwestern China. Microbiome 2025, 13, 122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.M.; Hu, S.J.; Lin, X.D.; Tian, J.H.; Lv, J.X.; Wang, M.R.; Luo, X.Q.; Pei, Y.Y.; Hu, R.X.; Song, Z.G.; et al. Host traits shape virome composition and virus transmission in wild small mammals. Cell 2023, 186, 4662–4675.e12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allen, T.; Murray, K.A.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Morse, S.S.; Rondinini, C.; Di Marco, M.; Breit, N.; Olival, K.J.; Daszak, P. Global hotspots and correlates of emerging zoonotic diseases. Nat. Commun. 2017, 8, 1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, W.K.; Anzolini Cassiano, M.H.; de Oliveira-Filho, E.F.; Brunink, S.; Yansanjav, A.; Yihune, M.; Koshkina, A.I.; Lukashev, A.N.; Lavrenchenko, L.A.; Lebedev, V.S.; et al. Ancient evolutionary origins of hepatitis E virus in rodents. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2024, 121, e2413665121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Order | Family | Species | Composition Ratio (%) | Infection Rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rodentia | Muridae | Rattus tanezumi | 35.45 (290/818) | 7.93 (23/290) |

| Apodemus chevrieri | 24.69 (202/818) | 12.87 (26/202) | ||

| Apodemus draco | 1.83 (15/818) | 0.00 (0/15) | ||

| Niviventer andersoni | 1.71 (14/818) | 0.00 (0/14) | ||

| Rattus norvegicus | 1.71 (14/818) | 0.00 (0/14) | ||

| Rattus rattus | 0.86 (7/818) | 0.00 (0/7) | ||

| Rattus andanmanensis | 0.61 (5/818) | 20.00 (1/5) | ||

| Rattus sikkimensis | 0.61 (5/818) | 0.00 (0/5) | ||

| Cricetidae | Eothenomys miletus | 14.67 (120/818) | 0.83 (1/120) | |

| Sciuridae | Callosciurus erythraeus | 0.37 (3/818) | 0.00 (0/3) | |

| Insectivora | Soricidae | Suncus murinus | 4.89 (40/818) | 0.00 (0/40) |

| Anourosorex squamipes | 4.16 (34/818) | 0.00 (0/34) | ||

| Crocidura attenuata | 2.69 (22/818) | 0.00 (0/22) | ||

| Episoriculus leucops | 1.71 (14/818) | 0.00 (0/14) | ||

| Erinaceidae | Hylomys suillus | 2.08 (17/818) | 0.00 (0/17) | |

| Scandentia | Tupaiidae | Tupaia belangeri | 0.86 (7/818) | 0.00 (0/7) |

| Lagomorpha | Ochotonidae | Ochotona thibetana | 1.10 (9/818) | 0.00 (0/9) |

| Total | 100 (818/818) | 6.23 (51/818) | ||

| Variable | Category | Composition Ratio (%) | Infection Rate (%) | χ2 | p (Uni.) a | OR (95%CI) | p (Multi.) b |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Locations | Cangyuan | 17.73 | 4.14 | 90.29 | <0.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| Gengma | 6.11 | 26 | 8.14 (2.90–22.87) | <0.001 | |||

| Gongshan | 25.43 | 1.92 | 0.45 (0.13–1.64) | 0.228 | |||

| Heqing | 18.83 | 17.53 | 4.93 (1.97–12.32) | <0.001 | |||

| Jiangcheng | 6.36 | 1.92 | 0.45 (0.05–3.87) | 0.47 | |||

| Lushui | 6.36 | 0 | 0 | 0.991 | |||

| Maguan | 6.11 | 0 | 0 | 0.985 | |||

| Species | Others | 39.85 | 0.61 | 35.27 | <0.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| Rattus tanezumi | 35.45 | 7.93 | 14.00 (3.27–59.89) | <0.001 | |||

| Apodemus chevrieri | 24.69 | 12.87 | 24.14 (5.67–102.88) | <0.001 | |||

| Sex | Female | 48.78 | 6.78 | 0.36 | 0.55 | NA c | NA c |

| Male | 51.1 | 5.76 | |||||

| Age | Childhood | 1.71 | 14.29 | 2.75 | 0.25 | NA c | NA c |

| Subadult | 10.64 | 3.45 | |||||

| Adult | 87.65 | 6.42 | |||||

| Landscape | Shrubbery area | 26.04 | 20.99 | 58.3 | <0.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| Cultivated area | 31.42 | 10.51 | 4.36 (1.86–10.20) | <0.001 | |||

| Residential area | 9.9 | 2.62 | 9.87 (3.93–24.80) | <0.001 | |||

| Forest area | 26.04 | 0 | 0 | 0.983 | |||

| Altitude (m) | 0–1499 | 46.09 | 5.31 | 38.85 | <0.001 | 1.00 (Reference) | |

| 1500–2999 | 27.87 | 4.88 | 2.81 (1.56–5.06) | <0.001 | |||

| 3000- | 26.04 | 7.52 | 0 | 0.982 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yang, Z.; Han, P.-Y.; Zhao, J.-Y.; Kong, W.; Long, Y.; Wu, S.; Zong, L.-D.; He, C.-J.; Chen, Y.-H.; Cao, W.-C.; et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Genetic Evolution of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Small Mammals from Southwestern Yunnan, China. Biology 2025, 14, 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121685

Yang Z, Han P-Y, Zhao J-Y, Kong W, Long Y, Wu S, Zong L-D, He C-J, Chen Y-H, Cao W-C, et al. Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Genetic Evolution of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Small Mammals from Southwestern Yunnan, China. Biology. 2025; 14(12):1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121685

Chicago/Turabian StyleYang, Ze, Pei-Yu Han, Jun-Ying Zhao, Wei Kong, Yun Long, Song Wu, Li-Dong Zong, Chen-Jie He, Yu-Hong Chen, Wan-Chun Cao, and et al. 2025. "Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Genetic Evolution of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Small Mammals from Southwestern Yunnan, China" Biology 14, no. 12: 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121685

APA StyleYang, Z., Han, P.-Y., Zhao, J.-Y., Kong, W., Long, Y., Wu, S., Zong, L.-D., He, C.-J., Chen, Y.-H., Cao, W.-C., Wang, B., & Zhang, Y.-Z. (2025). Prevalence, Risk Factors, and Genetic Evolution of Rat Hepatitis E Virus in Small Mammals from Southwestern Yunnan, China. Biology, 14(12), 1685. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121685