Optimal Dietary α-Starch Requirement and Its Effects on Growth and Metabolic Regulation in Chinese Hook Snout Carp (Opsariichthys bidens)

Simple Summary

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethical Approval

2.2. Experimental Diets

2.3. Fish and Feeding Trial

2.4. Sampling

2.5. Sample Analysis

2.6. RNA Extraction and cDNA Synthesis

2.7. Real-Time PCR Assays (qRT-PCR)

2.8. Statistical Analysis

- WGR = 100 × (final weight − initial weight)/initial weight;

- SGR = 100 × (ln (final weight) − ln (initial weight))/days;

- FI = Total food intake/(initial fish number × survival rate × culture days)

- FCR = 100 × total food intake/weight gain;

- VSI = 100 × (viscera weight/whole body weight);

- HSI = 100 × (liver weight/whole body weight);

- ISI = 100 × (gut weight/whole body weight);

- IPF = 100 × (intraperitoneal fat weight/body weight).

3. Results

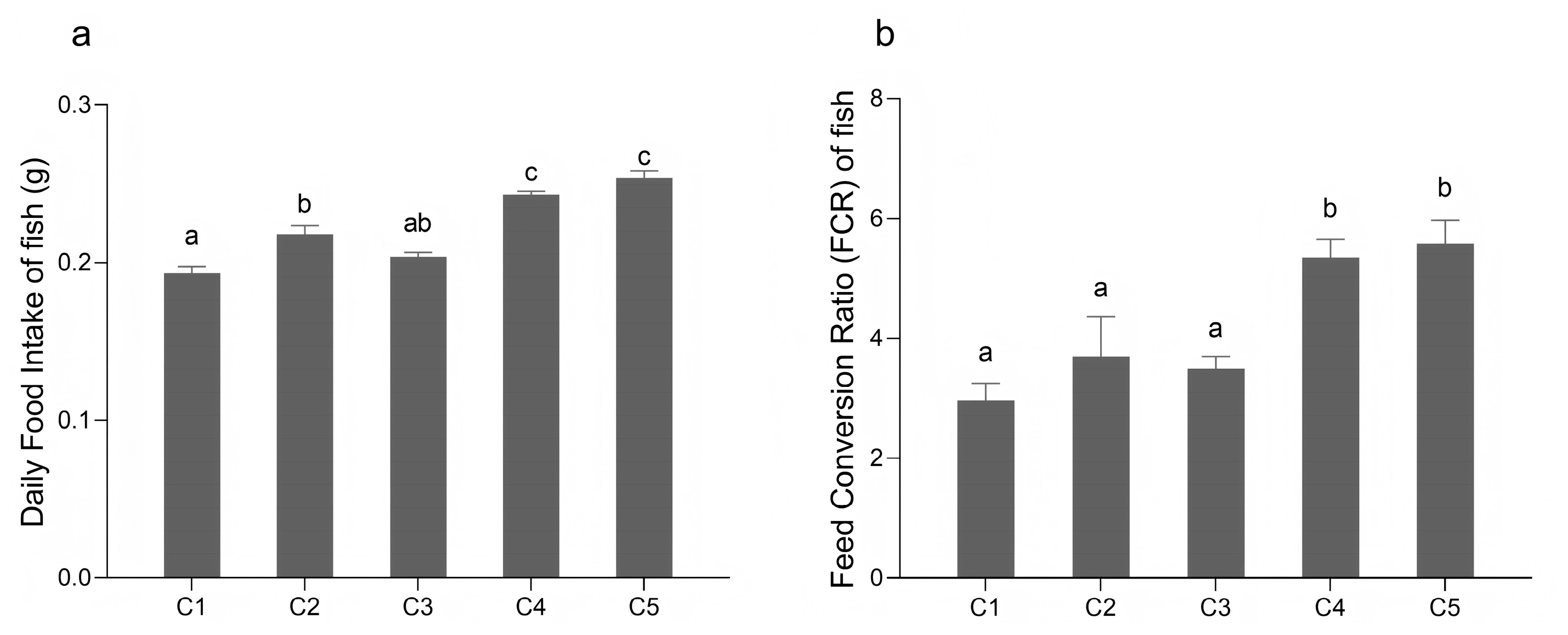

3.1. Growth Performance and Food Intake

3.2. Whole Body and Tissue Composition

3.3. Internal Organ Indices

3.4. Serum Biochemistry Parameters

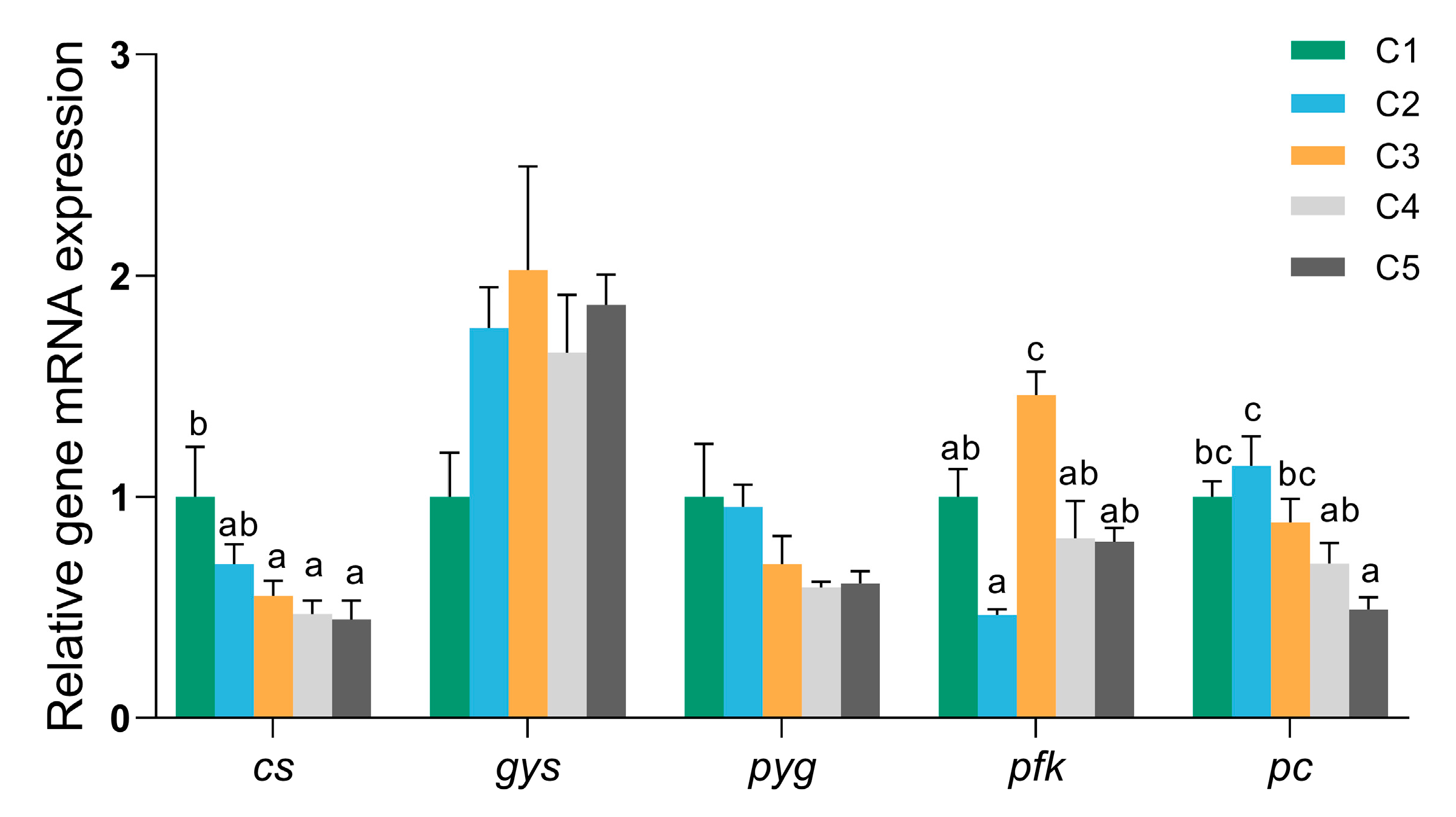

3.5. mRNA Expression Levels of Glucose Metabolism-Related Genes

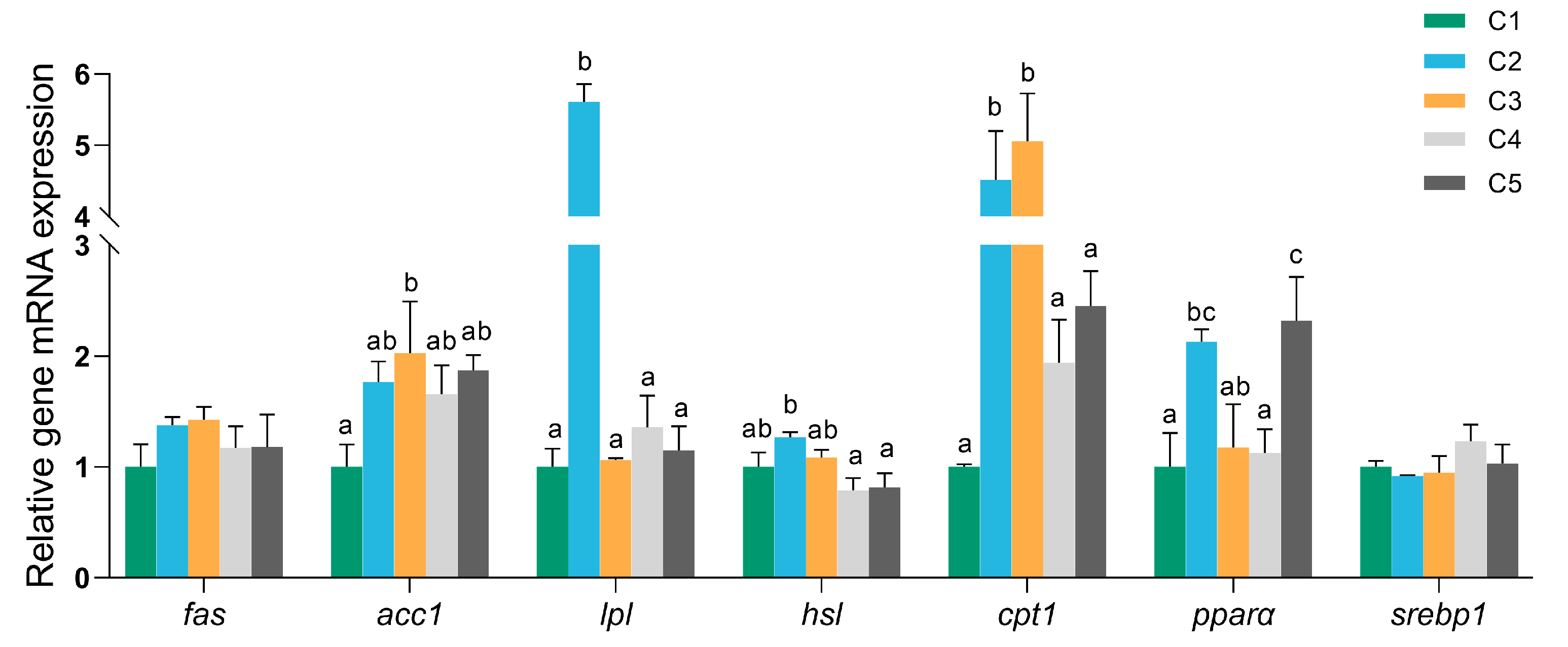

3.6. mRNA Expression Levels of Lipid Metabolism-Related Genes

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Li, G.-Y.; Wang, X.-Z.; Zhao, Y.-H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, C.-G.; He, S.-P. Speciation and phylogeography of Opsariichthys bidens (Pisces: Cypriniformes: Cyprinidae) in China: Analysis of the cytochrome b gene of mtDNA from diverse populations. Zool. Stud. 2009, 48, 569–583. [Google Scholar]

- Johansson, F.; Rådman, P.; Andersson, J. The relationship between ontogeny, morphology, and diet in the Chinese hook snout carp (Opsariichthys bidens). Ichthyol. Res. 2006, 53, 63–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Wang, X.; Liu, J.; Yang, S.; Zhao, D. The food habit of Opsariichthys bidens in Biliuhe Reservoir and fishery countermea sure. Fish. Sci 1995, 3, 35–38. [Google Scholar]

- Bei, Y.; He, L.; Jing, J.; Chen, X.; Yuan, F.; Yao, G.; Ding, X.; Wang, L.; Zhou, F. Dietary protein requirement of Chinese hook snout carp (Opsariichthys bidens) and transcriptomic analysis of the liver in response to different protein diets. Aquac. Rep. 2025, 40, 102637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamalam, B.S.; Medale, F.; Panserat, S. Utilisation of dietary carbohydrates in farmed fishes: New insights on influencing factors, biological limitations and future strategies. Aquaculture 2017, 467, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- National Research Council, Division on Earth; Committee on the Nutrient Requirements of Fish, Shrimp. Nutrient Requirements of Fish and Shrimp; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen, M.; Nguyen, G.; Storebakken, T.; Øverland, M. Starch source, screw configuration and injection of steam into the barrel affect the physical quality of extruded fish feed. Aquac. Res. 2010, 41, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polakof, S.; Panserat, S.; Soengas, J.L.; Moon, T.W. Glucose metabolism in fish: A review. J. Comp. Physiol. B 2012, 182, 1015–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kostyniuk, D.J.; Marandel, L.; Jubouri, M.; Dias, K.; de Souza, R.F.; Zhang, D.; Martyniuk, C.J.; Panserat, S.; Mennigen, J.A. Profiling the rainbow trout hepatic miRNAome under diet-induced hyperglycemia. Physiol. Genom. 2019, 51, 411–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, H.; Wang, Z.; Wang, J.; Wang, T.; Li, Y.; Guan, D.; Sun, H. Impact of high dietary cornstarch level on growth, antioxidant response, and immune status in GIFT tilapia Oreochromis niloticus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 6678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Xie, S.; Wei, H.; Zheng, L.; Liu, Z.; Fang, H.; Xie, J.; Liao, S.; Tian, L.; Liu, Y. High dietary starch impaired growth performance, liver histology and hepatic glucose metabolism of juvenile largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Aquac. Nutr. 2020, 26, 1083–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somsueb, P. Protein and energy requirement and feeding of fish. Animals 2017, 11, 77. [Google Scholar]

- Manam, V.K. Fish feed nutrition and its management in aquaculture. Int. J. Fish. Aquat. Stud. 2023, 11, 58–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.-J.; Mou, M.-M.; Pu, D.-C.; Lin, S.-M.; Chen, Y.-J.; Luo, L. Effect of dietary starch level on growth, metabolism enzyme and oxidative status of juvenile largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Aquaculture 2019, 498, 482–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Duy, A.; Smit, B.; van Dam, A.A.; Schrama, J.W. Effects of dietary starch and energy levels on maximum feed intake, growth and metabolism of Nile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 2008, 277, 213–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, L.X.; Liu, Y.J.; Yang, H.J.; Liang, G.Y.; Niu, J. Effects of different dietary wheat starch levels on growth, feed efficiency and digestibility in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella). Aquac. Int. 2012, 20, 283–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2−ΔΔCT method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiau, S.; Lin, Y. Carbohydrate utilization and its protein-sparing effect in diets for grouper (Epinephelus malabaricus). Anim. Sci. 2001, 73, 299–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Lei, J.; Ai, C.; Hong, W.; Liu, B. Protein-sparing effect of carbohydrate in diets for juvenile turbot Scophthalmus maximus reared at different salinities. Chin. J. Oceanol. Limnol. 2015, 33, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Meilán, I.; Ordóñez-Grande, B.; Gallardo, M. Meal timing affects protein-sparing effect by carbohydrates in sea bream: Effects on digestive and absorptive processes. Aquaculture 2014, 434, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Q.; Wang, F.; Xie, S.; Zhu, X.; Lei, W.; Shen, J. Effect of high dietary starch levels on the growth performance, blood chemistry and body composition of gibel carp (Carassius auratus var. gibelio). Aquac. Res. 2009, 40, 1011–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, M.; Ai, Q.; Mai, K.; Ma, H.; Wang, X. Effect of dietary carbohydrate level on growth performance, body composition, apparent digestibility coefficient and digestive enzyme activities of juvenile cobia, Rachycentron canadum L. Aquac. Res. 2011, 42, 1467–1475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amoah, A.; Coyle, S.D.; Webster, C.D.; Durborow, R.M.; Bright, L.A.; Tidwell, J.H. Effects of graded levels of carbohydrate on growth and survival of largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2008, 39, 397–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, X.; Li, J. Nutritional requirements and feed development technology of Siniperca chuatsi. Sci. Fish Farming 2020, 7, 66–67. [Google Scholar]

- Enes, P.; Peres, H.; Couto, A.; Oliva-Teles, A. Growth performance and metabolic utilization of diets including starch, dextrin, maltose or glucose as carbohydrate source by gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) juveniles. Fish Physiol. Biochem. 2010, 36, 903–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen, J.Ø.; Storebakken, T. Effects of dietary cellulose level on pellet quality and nutrient digestibilities in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss). Aquaculture 2007, 272, 458–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.; Jiang, H.; Wang, S.; Shi, G.; Li, M. Effects of dietary cellulose supplementation on the intestinal health and ammonia tolerance in juvenile yellow catfish Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 28, 101429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Cai, C.; Cui, G.; Ni, Q.; Jiang, R.; Su, X.; Wang, Q.; Chen, W.; Zhang, J.; Wu, P. High dosages of pectin and cellulose cause different degrees of damage to the livers and intestines of Pelteobagrus fulvidraco. Aquaculture 2020, 514, 734445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Sharma, J.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, A.; Krishna, V.H.; Chakrabarti, R. Validation of growth enhancing, immunostimulatory and disease resistance properties of Achyranthes aspera in Labeo rohita fry in pond conditions. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, J.; Kumar, N.; Singh, S.P.; Singh, A.; HariKrishna, V.; Chakrabarti, R. Evaluation of immunostimulatory properties of prickly chaff flower Achyranthes aspera in rohu Labeo rohita fry in pond conditions. Aquaculture 2019, 505, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Tian, L.X.; Du, Z.Y.; Wang, J.T.; Wang, S.; Xiao, W.P. Effects of dietary carbohydrate level on growth and body composition of juvenile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus × O. aureus. Aquac. Res. 2005, 36, 1408–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, C.; Ge, X.; Niu, J.; Lin, H.; Huang, Z.; Tan, X. Effect of dietary carbohydrate levels on growth performance, body composition, intestinal and hepatic enzyme activities, and growth hormone gene expression of juvenile golden pompano, Trachinotus ovatus. Aquaculture 2015, 437, 390–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.Y.; Wang, J.T.; Han, T.; Hu, S.X.; Jiang, Y.D. Effects of dietary carbohydrate level on growth and body composition of juvenile giant croaker Nibea japonica. Aquac. Res. 2015, 46, 2851–2858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, D.; Yang, L.; Yu, R.; Chen, F.; Lu, R.; Qin, C.; Nie, G. Effects of dietary carbohydrate and lipid levels on growth and hepatic lipid deposition of juvenile tilapia, Oreochromis niloticus. Aquaculture 2017, 479, 696–703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjøen, T.; Berg, T. Hepatic uptake and intracellular processing of LDL in rainbow trout. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Lipids Lipid Metab. 1993, 1169, 225–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjoumani, J.-J.Y.; Abasubong, K.P.; Zhang, L.; Ge, Y.-P.; Liu, W.-B.; Li, X.-F. A time-course study of the effects of a high-carbohydrate diet on the growth performance, glycolipid metabolism and mitochondrial biogenesis and function of blunt snout bream (Megalobrama amblycephala). Aquaculture 2022, 552, 738011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, B.; Yan, L.; Wang, P.; Zhao, C.; Lin, H.; Qiu, L.; Zhou, C. Effects of high dietary carbohydrate levels on growth performance, enzyme activities, expression of genes related to liver glucose metabolism, and the intestinal microbiota of Lateolabrax maculatus Juveniles. Fishes 2023, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panserat, S.; Médale, F.; Blin, C.; Breque, J.; Vachot, C.; Plagnes-Juan, E.; Gomes, E.; Krishnamoorthy, R.; Kaushik, S. Hepatic glucokinase is induced by dietary carbohydrates in rainbow trout, gilthead seabream, and common carp. Am. J. Physiol.-Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2000, 278, R1164–R1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Xu, W.; Jin, J.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Y.; Han, D.; Liu, H.; Xie, S. Effects of dietary carbohydrate and lipid concentrations on growth performance, feed utilization, glucose, and lipid metabolism in two strains of gibel carp. Front. Vet. Sci. 2019, 6, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, J.; Mei, L.; Xi, L.; Gong, Y.; Yang, Y.; Jin, J.; Liu, H.; Zhu, X.; Xie, S.; Han, D. Responses of glycolysis, glycogen accumulation and glucose-induced lipogenesis in grass carp and Chinese longsnout catfish fed high-carbohydrate diet. Aquaculture 2021, 533, 736146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, P.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, P.; Xie, Y.; Wu, C. Effects of Five Dietary Carbohydrate Sources on Growth, Glucose Metabolism, Antioxidant Capacity and Immunity of Largemouth Bass (Micropterus salmoides). Animals 2024, 14, 1492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.-F.; Wang, B.-K.; Xu, C.; Shi, H.-J.; Zhang, L.; Liu, J.-D.; Tian, H.-Y.; Liu, W.-B. Regulation of mitochondrial biosynthesis and function by dietary carbohydrate levels and lipid sources in juvenile blunt snout bream Megalobrama amblycephala. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2019, 227, 14–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, C.; Ge, X.; Liu, B.; Xie, J.; Miao, L. Effect of high dietary carbohydrate on the growth performance and physiological responses of juvenile Wuchang bream, Megalobrama amblycephala. Asian-Australas. J. Anim. Sci. 2013, 26, 1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, C.; Corraze, G.; Basto, A.; Larroquet, L.; Panserat, S.; Oliva-Teles, A. Dietary lipid and carbohydrate interactions: Implications on lipid and glucose absorption, transport in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) juveniles. Lipids 2016, 51, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Deng, K.; Pan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Sampath, W.W.H.A.; Zhang, W.; Mai, K. Molecular adaptations of glucose and lipid metabolism to different levels of dietary carbohydrates in juvenile Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus. Aquac. Nutr. 2020, 26, 516–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viegas, I.; Jarak, I.; Rito, J.; Carvalho, R.A.; Metón, I.; Pardal, M.A.; Baanante, I.V.; Jones, J.G. Effects of dietary carbohydrate on hepatic de novo lipogenesis in European seabass (Dicentrarchus labrax L.). J. Lipid Res. 2016, 57, 1264–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.-M.; Kim, K.-D.; Lall, S.P. Utilization of glucose, maltose, dextrin and cellulose by juvenile flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus). Aquaculture 2003, 221, 427–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.-J.; Liang, X.-F.; Yuan, X.-C.; Li, A.-X.; He, S. Changes of DNA methylation pattern in metabolic pathways induced by high-carbohydrate diet contribute to hyperglycemia and fat deposition in grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idellus). Front. Endocrinol. 2020, 11, 398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Pan, J.; Wang, X.; Huang, Y.; Qin, C.; Qiao, F.; Qin, J.; Chen, L. Alleviation of the adverse effect of dietary carbohydrate by supplementation of myo-inositol to the diet of Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Animals 2020, 10, 2190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.J.; Tian, L.X.; Yang, H.J.; Chen, P.F.; Yuan, Y.; Liu, Y.J.; Liang, G.Y. Effect of protein and starch level in practical extruded diets on growth, feed utilization, body composition, and hepatic transaminases of juvenile grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella. J. World Aquac. Soc. 2012, 43, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skiba-Cassy, S.; Lansard, M.; Panserat, S.; Médale, F. Rainbow trout genetically selected for greater muscle fat content display increased activation of liver TOR signaling and lipogenic gene expression. Am. J. Physiol. Regul. Integr. Comp. Physiol. 2009, 297, R1421–R1429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bou, M.; Todorčević, M.; Fontanillas, R.; Capilla, E.; Gutierrez, J.; Navarro, I. Adipose tissue and liver metabolic responses to different levels of dietary carbohydrates in gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata). Comp. Biochem. Physiol. Part A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2014, 175, 72–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, X.; Marandel, L.; Skiba-Cassy, S.; Corraze, G.; Dupont-Nivet, M.; Quillet, E.; Geurden, I.; Panserat, S. Regulation by dietary carbohydrates of intermediary metabolism in liver and muscle of two isogenic lines of rainbow trout. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Liang, X.-f.; Yuan, X.; Liu, L.; He, S.; Li, J.; Li, B.; Xue, M. Different strategies of grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella) responding to insufficient or excessive dietary carbohydrate. Aquaculture 2018, 497, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Fu, Y.; Wu, Z.; Yu, X.; Guo, Y.; Liu, J.; Zhang, W.; Mai, K. Effects of dietary carbohydrate levels on growth performance, body composition, glucose/lipid metabolism and insulin signaling pathway in abalone Haliotis discus hannai. Aquaculture 2022, 557, 738284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Item | C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ingredients % | |||||

| Fish meal | 26.00 | 26.00 | 26.00 | 26.00 | 26.00 |

| Casein (1) | 28.50 | 28.50 | 28.50 | 28.50 | 28.50 |

| Fish oil | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 |

| Soybean oil | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 | 2.75 |

| α-starch (2) | 8.00 | 14.00 | 20.00 | 26.00 | 32.00 |

| Vitamin and mineral mix (3) | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 | 4.00 |

| Cellulose | 24.00 | 18.00 | 12.00 | 6.00 | 0.00 |

| Ca(H2PO4)2 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 | 1.50 |

| Choline chloride | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 | 0.50 |

| Sodium carboxymethylcellulose | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 | 2.00 |

| Compositions | |||||

| Dry matter (DM) (%) | 95.22 | 94.35 | 94.86 | 95.61 | 94.12 |

| Crude protein (% DM) | 42.05 | 42.05 | 42.05 | 42.05 | 42.05 |

| Crude lipid (% DM) | 7.85 | 7.85 | 7.85 | 7.85 | 7.85 |

| Ash (% DM) | 14.22 | 15.47 | 13.64 | 14.65 | 14.33 |

| Nitrogen-free extract (% DM) | 10.68 | 15.55 | 23.81 | 29.17 | 35.77 |

| Gross energy (Mcal/kg) | 274.69 | 298.69 | 322.69 | 346.69 | 370.69 |

| Gene | Primer Sequences (5′ to 3′) | Tm (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| fas | F: GGCATCTGGAGGCAGTTTG | 55.0 |

| R: GTGAATGTCCTGACCCGTG | ||

| acc1 | F: TGTTGTTGTTTGTCCCTCCTG | 55.0 |

| R: TACTGTCGCTTCCCCCG | ||

| lpl | F: GGATAATAAGGAAGGTTTGGGAA | 55.0 |

| R: AGCAGACAGTGGACTACAGTGACA | ||

| hsl | F: TTGTTCACAGTCGTGTCGTCT | 55.0 |

| R: GATTTCATTGGCTCAAGGTT | ||

| cpt1 | F: GCAGAAACCGCACGAATC | 55.0 |

| R: GTGGCAGCGAACAACAGTC | ||

| pparα | F: GTGACCTCGCACTGTTTGT | 55.0 |

| R: CTGGGTGGTTGCTCTTTAG | ||

| srebp1 | F: GAGTATTCCCCGTCCCC | 55.0 |

| R: CCTGTCTCTCGCCAAGC | ||

| cs | F: TCTCACTGTTCAGAGCCGT | 55.0 |

| R: ATCCGTTTCCGTGGTTAC | ||

| gys | F: GGCGGGAGCGGCACAG | 55.0 |

| R: ACGACAGGGAGGCGAACGA | ||

| pc | F: TTCACAGAGTCAGCAGTCAGTC | 55.0 |

| R: GGCGATAAATACGGCAAC | ||

| pfk | F: TGTGACCGAATCAAGCAATC | 55.0 |

| R: GCCCCAGCCGCTAAACC | ||

| pyg | F: GGAGGGGAAGGAGCCG | 55.0 |

| R: GGAGATTGAAGTCGTTGGGA | ||

| β-actin | F: CAAACCCCCCCAAACCTA | 55.0 |

| R: GAGCATCATCTCCAGCGAAT |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body composition (%) | ||||||

| Moisture | 73.42 ± 1.26 | 72.75 ± 0.56 | 72.55 ± 0.35 | 72.73 ± 0.65 | 71.76 ± 0.94 | 0.772 |

| Crude Protein | 15.90 ± 0.06 ab | 16.30 ± 0.11 ab | 16.67 ± 0.05 b | 15.61 ± 0.20 a | 18.17 ± 0.60 c | 1.2 × 10−5 |

| Crude Lipid | 8.30 ± 0.16 a | 12.85 ± 0.01 b | 10.62 ± 0.01 ab | 12.98 ± 0.01 b | 32.5 ± 0.14 c | 1.782 × 10−10 |

| Ash | 2.38 ± 0.04 | 2.43 ± 0.12 | 2.36 ± 0.03 | 2.41 ± 0.16 | 2.40 ± 0.04 | 0.528 |

| Muscle composition (%) | ||||||

| Moisture | 77.42 ± 0.25 ab | 78.14 ± 0.14 ab | 77.21 ± 0.64 a | 77.44 ± 0.18 ab | 78.38 ± 0.22 b | 0.048 |

| Crude Protein | 17.80 ± 0.01 a | 18.20 ± 0.20 b | 17.68 ± 0.15 a | 18.18 ± 0.06 b | 17.73 ± 0.02 a | 0.011 |

| Crude Lipid | 7.23 ± 0.2 c | 6.64 ± 0.2 bc | 4.36 ± 0.2 ab | 4.63 ± 0.2 ab | 3.74 ± 0.2 a | 0.037 |

| Ash | 1.35 ± 0.24 | 1.36 ± 0.26 | 1.41 ± 0.23 | 1.34 ± 0.04 | 1.38 ± 0.05 | 0.414 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VSI | 9.27 ± 0.32 b | 7.82 ± 0.29 a | 8.87 ± 0.30 ab | 9.71 ± 0.70 b | 8.61 ± 0.41 ab | 0.049 |

| ISI | 2.71 ± 0.12 b | 1.76 ± 0.08 a | 2.00 ± 0.11 a | 2.49 ± 0.14 b | 2.60 ± 0.13 b | 7.0 × 10−5 |

| HSI | 0.82 ± 0.10 a | 0.70 ± 0.01 a | 0.58 ± 0.12 a | 0.77 ± 0.13 ab | 1.18 ± 0.23 b | 0.031 |

| IPF | 2.48 ± 0.45 a | 2.30 ± 0.27 a | 3.35 ± 0.35 b | 2.89 ± 0.83 ab | 3.33 ± 0.46 b | 0.043 |

| C1 | C2 | C3 | C4 | C5 | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GLU (mmol/L) | 2.12 ± 0.21 a | 2.52 ± 0.34 a | 3.78 ± 0.28 b | 6.10 ± 0.11 c | 7.49 ± 0.09 d | 4.21 × 10−8 |

| TG (mmol/L) | 0.97 ± 0.15 a | 0.97 ± 0.05 a | 1.15 ± 0.06 ab | 1.28 ± 0.04 bc | 1.46 ± 0.09 c | 0.011 |

| CHO (mmol/L) | 3.09 ± 0.41 a | 3.57 ± 0.66 a | 3.62 ± 0.12 a | 8.42 ± 0.43 b | 8.62 ± 0.14 b | 1.07 × 10−5 |

| LDL (mmol/L) | 1.63 ± 0.38 b | 0.36 ± 0.08 a | 0.95 ± 0.14 a | 0.44 ± 0.10 a | 0.65 ± 0.15 a | 0.007 |

| HDL (mmol/L) | 1.88 ± 0.58 a | 3.59 ± 0.38 ab | 2.82 ± 0.16 a | 5.43 ± 0.36 c | 5.03 ± 0.88 bc | 0.004 |

| LDL/HDL | 0.99 ± 0.28 b | 0.10 ± 0.01 a | 0.35 ± 0.07 a | 0.08 ± 0.03 a | 0.15 ± 0.06 a | 0.003 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cai, W.; Luo, X.; Li, J.; Duan, Y.; Wei, Y.; Xing, Y.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, C. Optimal Dietary α-Starch Requirement and Its Effects on Growth and Metabolic Regulation in Chinese Hook Snout Carp (Opsariichthys bidens). Biology 2025, 14, 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121687

Cai W, Luo X, Li J, Duan Y, Wei Y, Xing Y, Hu Z, Zhu C. Optimal Dietary α-Starch Requirement and Its Effects on Growth and Metabolic Regulation in Chinese Hook Snout Carp (Opsariichthys bidens). Biology. 2025; 14(12):1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121687

Chicago/Turabian StyleCai, Wenjing, Xiaonian Luo, Jiao Li, Youjian Duan, Yong Wei, Yuxin Xing, Zongyun Hu, and Chunyue Zhu. 2025. "Optimal Dietary α-Starch Requirement and Its Effects on Growth and Metabolic Regulation in Chinese Hook Snout Carp (Opsariichthys bidens)" Biology 14, no. 12: 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121687

APA StyleCai, W., Luo, X., Li, J., Duan, Y., Wei, Y., Xing, Y., Hu, Z., & Zhu, C. (2025). Optimal Dietary α-Starch Requirement and Its Effects on Growth and Metabolic Regulation in Chinese Hook Snout Carp (Opsariichthys bidens). Biology, 14(12), 1687. https://doi.org/10.3390/biology14121687