Proposal for Zeolite Waste from Fluid Catalytic Cracking as a Pozzolanic Addition for Earth Mortars: Initial Characterisation

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. State of the Art

3. Objectives

4. Methodology

4.1. Material and Test Times

4.2. Execution Methodology

5. Test Plan

5.1. Test Programme

5.2. Prior Characterisation Tests

5.3. Physical–Mechanical Tests

5.4. Tests on Behaviour upon Contact with Water

6. Results

6.1. SEM Analytical Results

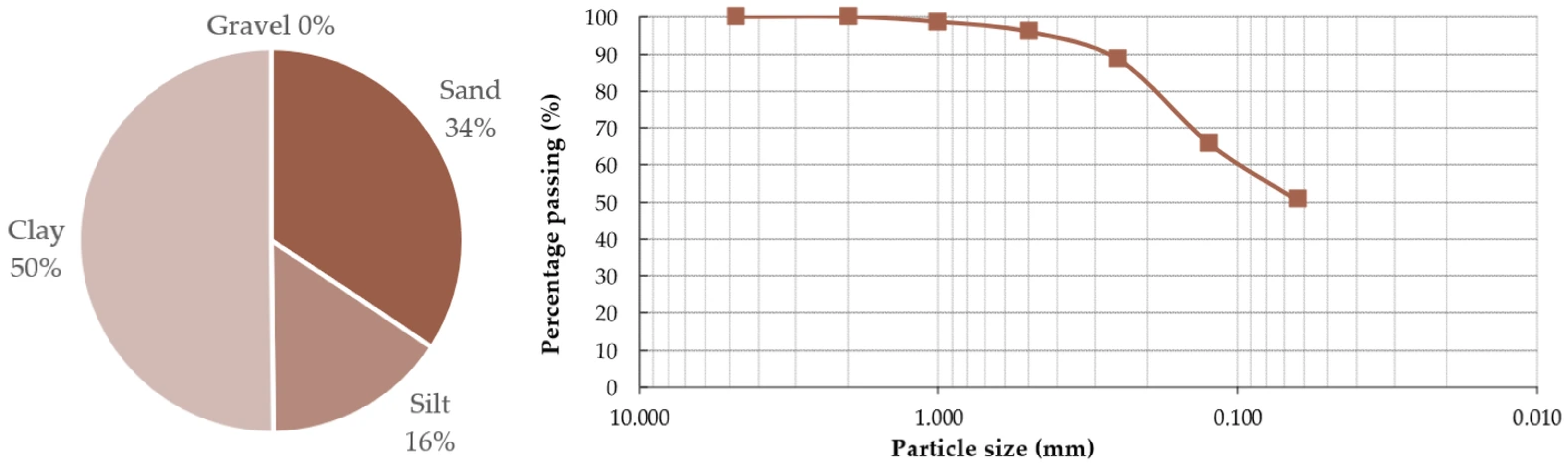

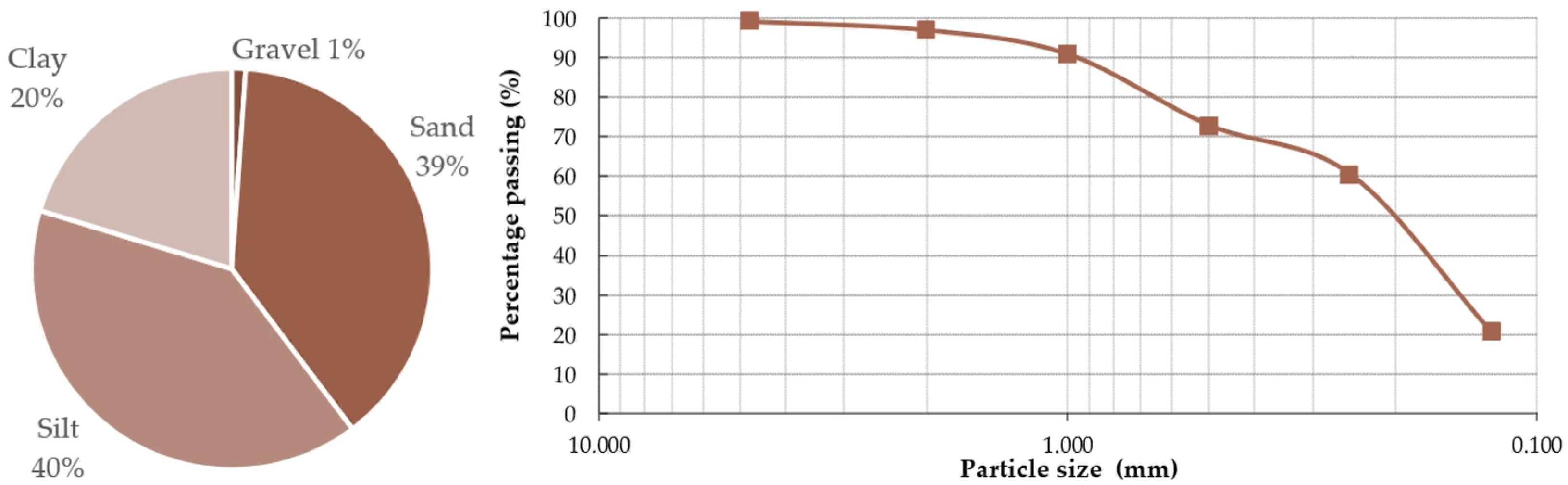

6.2. Particle Size Distribution

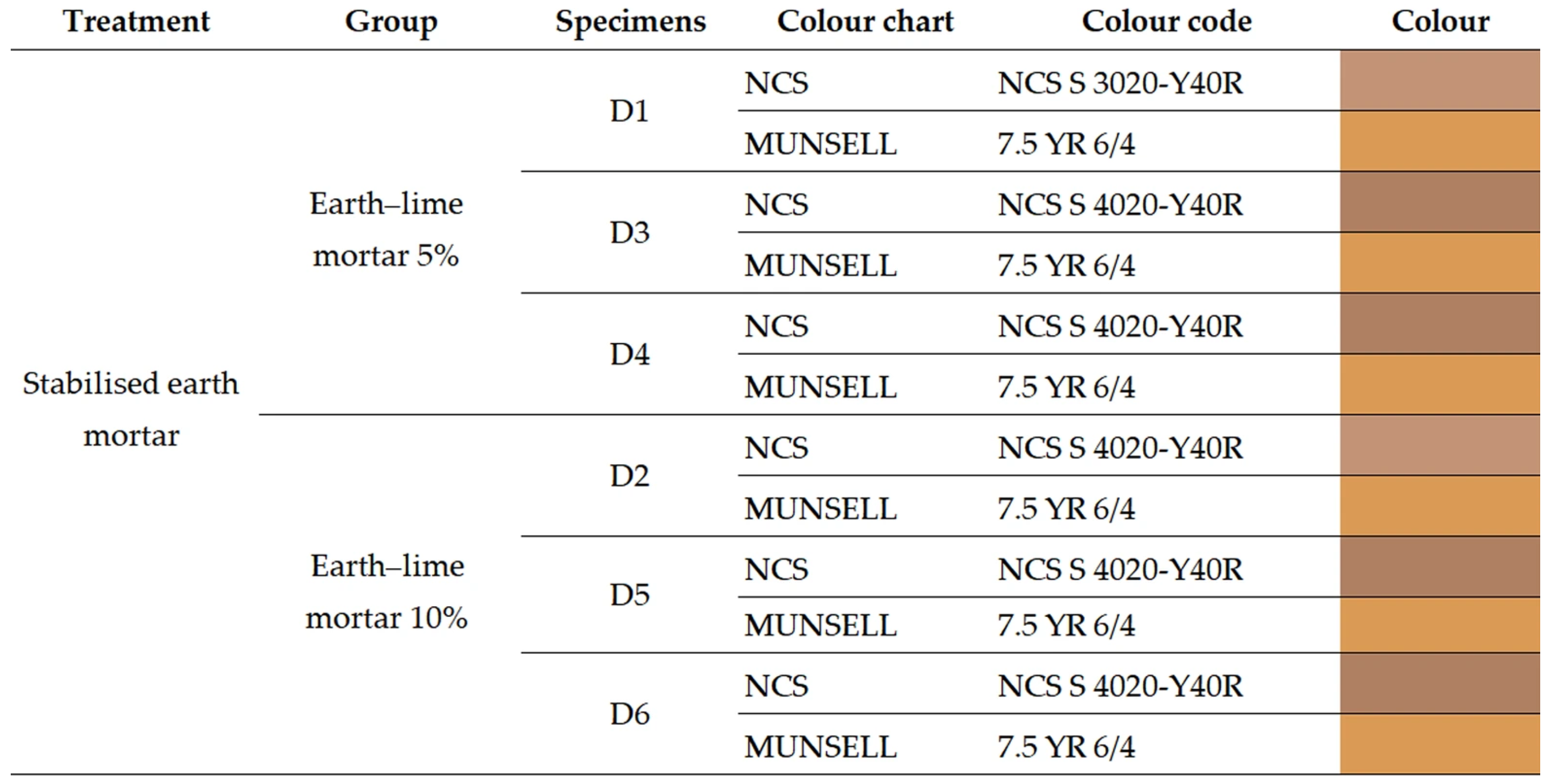

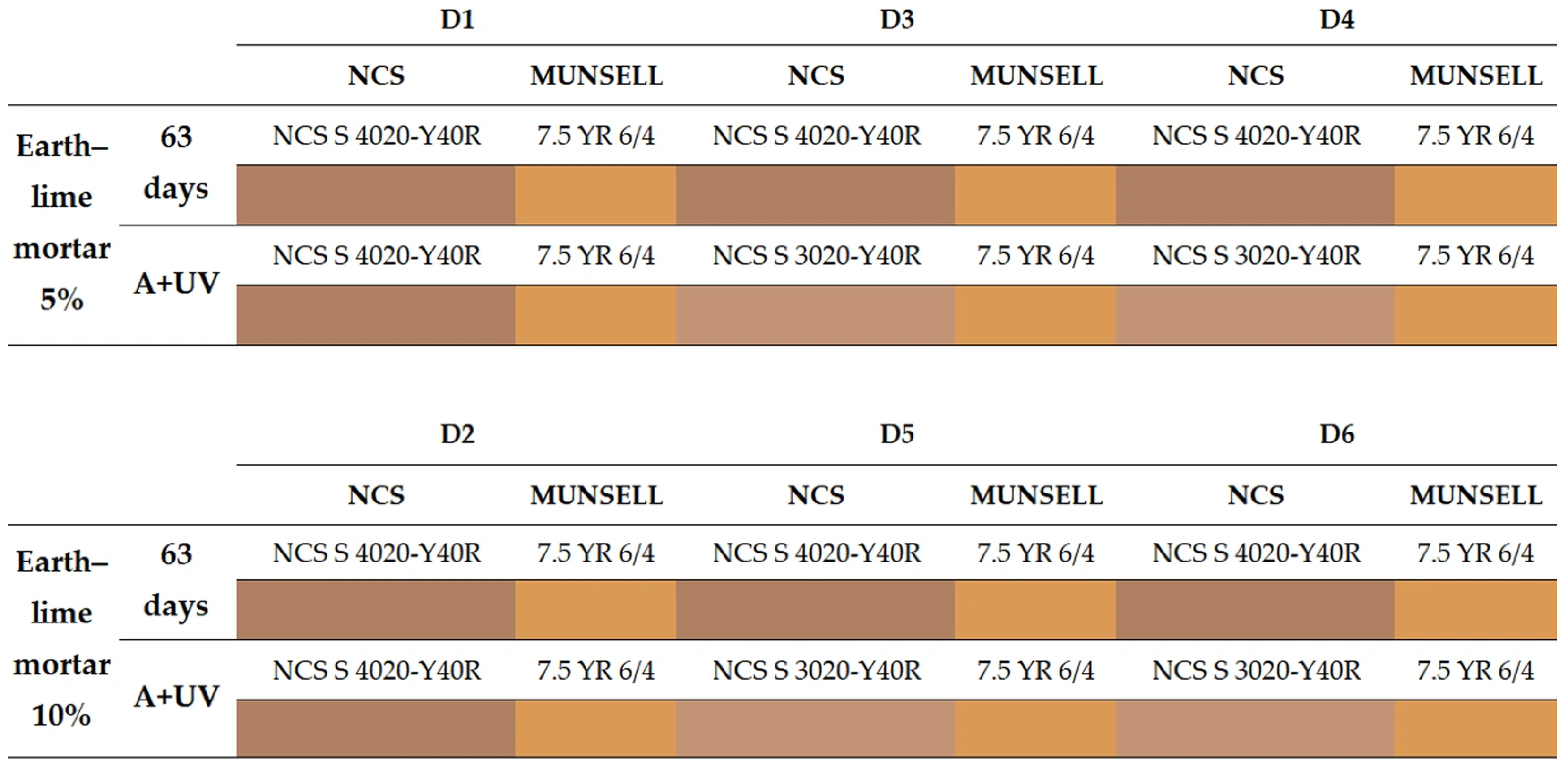

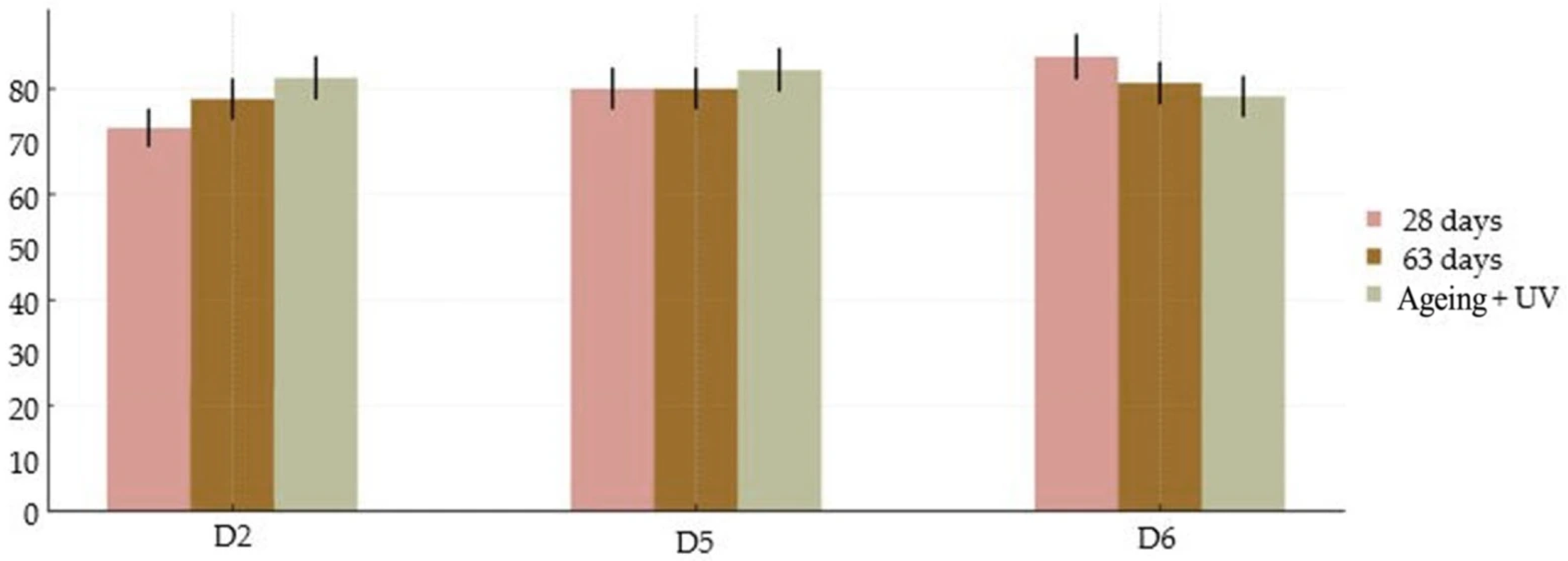

6.3. Colorimetry Results

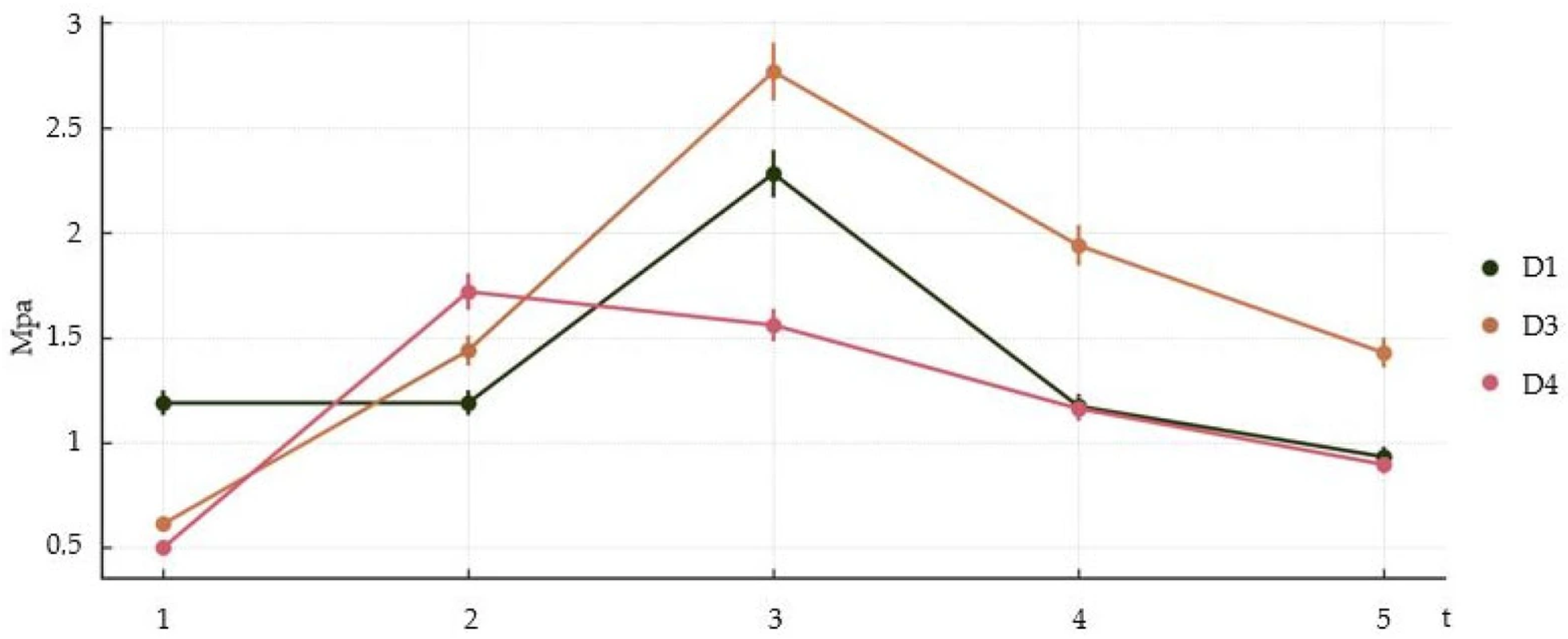

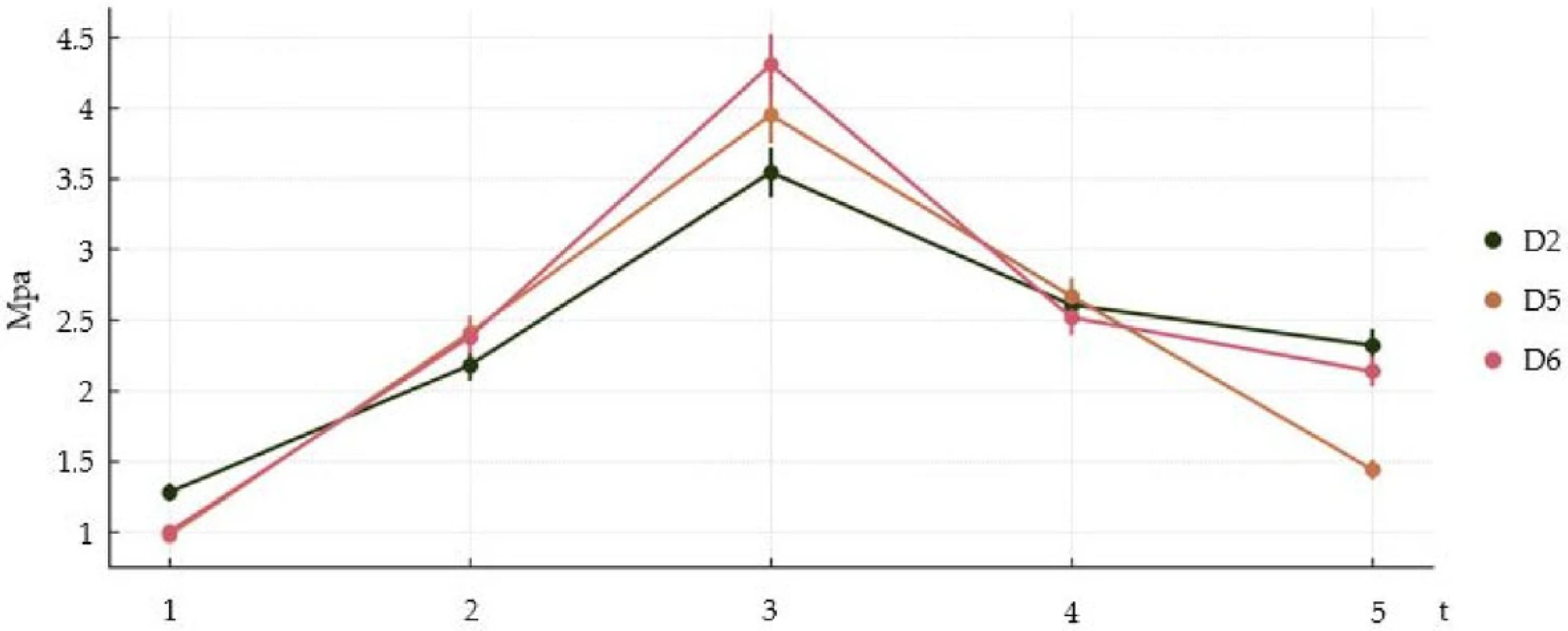

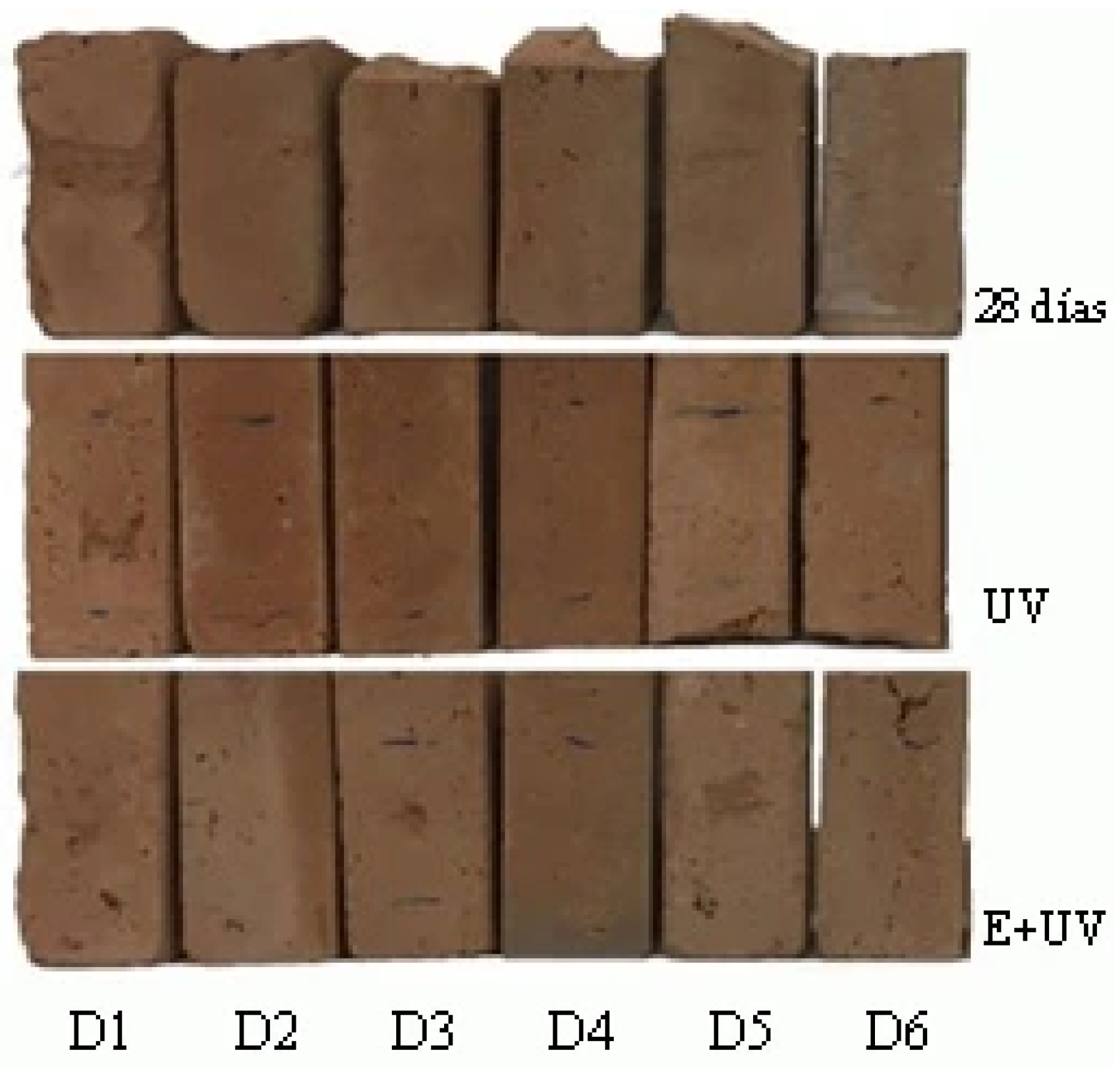

6.4. Results of Physical–Mechanical Tests

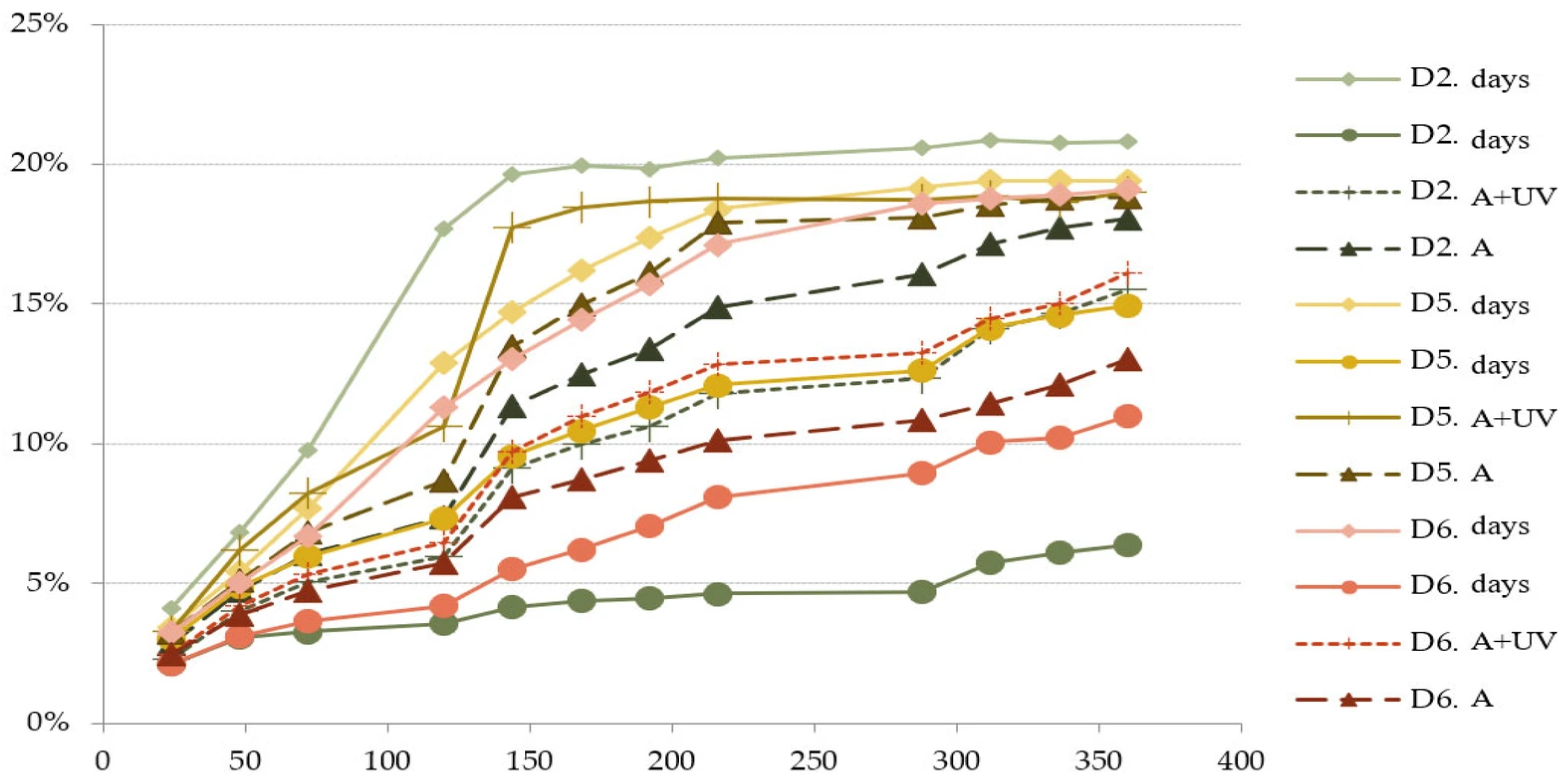

6.5. Results of Behaviour in Contact with Water

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Soriano Martínez, L. Nuevas Aportaciones en el Desarrollo de Materiales Cementantes con Residuo de Catalizador de Craqueo Catalítico (FCC). Ph.D. Thesis, Universitat Politècnica de València, Valencia, Spain, 2007. Available online: https://riunet.upv.es/handle/10251/2542 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Escandino, A.; Amorós, J.L.; Moreno, A.; Sánchez, E. Utilizing the used catalyst from refinery FCC units as a substitute for kaolin in formulating ceramic frits. Waste Manag. Res. 1995, 13, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García de Lomas Gómez, M. Viabilidad Científica, Técnica y Medioambiental del Catalizador Gastado de Craqueo Catalítico (FCC) como Material Puzolánico. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10486/671799 (accessed on 15 July 2024).

- Pacewska, B.; Wilinska, I.; Bukowska, M. Use of spent catalyst from catalytic cracking in fluidized bed as a new concrete additive. Thermochim. Acta 1988, 322, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payá, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Monzó, J.; Soriano, L. Estudio del comportamiento de diversos residuos de catalizadores de craqueo catalítico (FCC) en cemento Portland. Mater. Construcción 2009, 59, 37–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacewska, B.; Wilinska, I.; Bukowska, M. Hydration of cement slurry in the presence of spent cracking catalyst. J. Therm. Anal. Calorim. 2000, 60, 71–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, N.; Chen, Z.H.; Fang, H.Y. Reuse of spent catalyst as fine aggregate in cement mortar. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2001, 23, 111–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omoniyi Odjo, A. Reciclado de Polímeros por Craqueo Catalítico; Estudio de la Viabilidad de Utilización de Reactores Convencionales de Craqueo Catalítico en Lecho Fluidificado. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Alicante, San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain, 2016. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10045/68368 (accessed on 1 December 2024).

- Elert, K. Alkaline Activation of Clays for the Consolidation of Earthen Architecture. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Granada, Granada, Spain, 2014; p. 317. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/10481/34114 (accessed on 1 March 2024).

- Chen, H.L.; Tseng, Y.S.; Hsu, K.C. Spent FCC catalyst as a pozzolanic material for high-performance mortars. Cem. Concr. Compos. 2005, 26, 657–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Payá, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Monzó, J.; Gonzalez Lopez, E. Propiedades de morteros y hormigones fabricados con cementos tipo CEM II/A-Q a base de catalizador gastado de craqueo catalítico (FCC). In Proceedings of the III Congreso Nacional de Materiales Compuestos (MATCOMP99) (AEMAC), Gijón, Spain, 5–7 May 1999; pp. 493–500, ISBN 84-607-0078-X. [Google Scholar]

- Payá, J.; Monzó, J.; Borrachero, M.V.; Velázquez, S. The chemical activation of pozzolanic reaction of fluid cracking catalyst residue (FC3R) in lime pastes. Adv. Cem. Res. 2007, 19, 9–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piles, V.; Borrachero, M.V.; Payá, J.; Monzó, J.; García-Codoñer, Á. Ensayos de envejecimiento acelerado sobre materiales compuestos con base de cal o con base mixta de cal y yeso. In Proceedings of the Actas del VI Congreso Nacional de Materiales Compuestos (MATCOMP05) (AEMAC), Zaragoza, Spain, 28–30 June 2005; pp. 947–954, ISBN 84-9705-821-6. [Google Scholar]

- Nan, S.; Hung-Yuan, F.; Zong-Huei, C.; Fu-Sung, L. Reuse of waste catalysts from petrochemical industries for cement substitution. Cem. Concr. Res. 2000, 30, 1773–1783. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Jabri, K.; Baawain, M.; Taha, R.; Al-Kamyani, Z.S.; Al-Shamsi, K.; Ishtieh, A. Potential use of FCC spent catalyst as partial replacement of cement or sand in cement mortars. Constr. Build. Mater. 2013, 39, 77–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez-López, C.; Torres-Agredo, J.; Mejía- De Gutiéerrez, R.; Mellado-Romero, A.M.; PayáBernabeu, J.; Monzó-Balbuena, J.M. Uso de test de lixiviación para determinar la migración de contaminantes en morteros de sustitución con residuos de Catalizador de craqueo catalítico (FCC). Rev. Fac. Minas Univ. Nac. Colomb. 2013, 80, 163–170. [Google Scholar]

- Houben, H.; Guillaud, H. Earth Construction: A Comprehensive Guide; Practical Action Publishing: London, UK, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- UNE 103101:1995; Particle Size Analysis of a Soil by Screening. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 1995.

- UNE-EN ISO 17892-4:2019; Geotechnical Investigation and Testing—Laboratory Testing of Soil—Part 4: Determination of Particle Size Distribution. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2019.

- Mileto, C.; Vegas, F.; López, J.M. Criterios y técnicas de intervención en tapia. La restauración de la torre Bofilla de Bétera (Valencia). Inf. Construcción 2011, 63, 81–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schroeder, H. Transferencia de humedad y el cambio en la resistencia durante la construcción de edificios de tierra. Inf. Construcción 2011, 63, 107–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNE-EN 772-1:2011; Methods of Test for Masonry Units—Part 1: Determination of Compressive Strength. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- UNE-EN 1097-3:1999; Tests for Mechanical and Physical Properties of Aggregates—Part 3: Determination of Loose Bulk Density and Voids. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 1999.

- UNE 102042:2023; Gypsum Plasters. Other Test Methods. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- UNE-EN 13286-2:2010; Unbound and Hydraulically Bound Mixtures—Part 2: Test Methods for Laboratory Reference Density and Water Content—Proctor Compaction. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- UNE-EN 13279-2:2014; Gypsum Binders and Gypsum Plasters—Part 2: Test Methods. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2014.

- UNE-EN 41410:2023; Compressed Earth Blocs for Walls and Partitions. Definitions, Specifications and Test Methods. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2023.

- UNE-EN 15886:2011; Conservation of Cultural Property—Test Methods—Colour Measurement of Surfaces. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2011.

- UNE-EN 15801:2010; Conservation of Cultural Property—Test Methods—Determination of Water Absorption by Capillarity. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- UNE-EN 15803:2010; Conservation of Cultural Property—Test Methods—Determination of Water Vapour Permeability (dp). AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2010.

- UNE-EN 17036:2019; Conservation of Cultural Heritage—Artificial Ageing by Simulated Solar Radiation of the Surface of Untreated or Treated Porous Inorganic Materials. AENOR: Madrid, Spain, 2019.

| Reference Group | Reference Samples | |

| D1 | 1500 g soil + sand, 75 g lime, 316.5 mL water | |

| D2 | 1500 g soil + sand, 150 g lime, 7.5 g FCC, 316.5 mL water | |

| Test Group | Test Samples | Reference |

| D3 | 1500 g soil + sand, 75 g lime, 7.5 g FCC, 316.5 mL w | D1 |

| D4 | 1500 g soil + sand, 75 g lime, 11.25 g FCC, 316.5 mL w | D1 |

| D5 | 1500 g soil + sand, 150 g lime, 15 g FCC, 316.5 mL w | D2 |

| D6 | 1500 g soil + sand, 150 g lime, 22.5 g FCC, 316.5 mL w | D2 |

| Reference Group | Reference Samples | |||

| D1 | Earth–Lime 5% | 9:0.5 | ||

| D2 | Earth–Lime 10% | 9:1 | ||

| Test Group | Test Samples | % Zeolite | Reference Test Sample | |

| D3 | Lime 5% + Zeolite 10% | 9:0.5:1 | 0.5% | D1 |

| D4 | Lime 5% + Zeolite 15% | 9:0.33:1 | 0.75% | D1 |

| D5 | Lime 10% + Zeolite 10% | 9:1:1 | 1% | D2 |

| D6 | Lime 10% + Zeolite 15% | 9:0.66:1 | 1.5% | D2 |

| Duration | Temperature | Humidity | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle 1 | 24 h | 20 °C | 85% |

| 24 h | 60 °C | 85% | |

| Cycle 2 | 24 h | 5 °C | 40%–45% |

| 24 h | −20 °C | 55% |

| 63 Days | Ageing | |

|---|---|---|

| D3 | −6.54% | 14.46% |

| D4 | 8.07% | 28.77% |

| 28 Days | 63 Days | UV Ageing | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dimensions | Footprint | Dimensions | Footprint | Dimensions | Footprint | ||||

| D1 | 3.9 cm | 1.9 cm | 3 mm | 1.6 cm | 1.2 cm | 2 mm | 1.3 cm | 1 cm | 1.5 mm |

| D2 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| D3 | - | - | - | 7 mm | 5 mm | <1 mm | 0.9 mm | 0.7 mm | 1.5 mm |

| D4 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| D5 | 2.3 cm | 1.2 cm | 1 mm | - | - | - | 1.6 cm | 1.4 cm | 2 mm |

| D6 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Barros Magdalena, M.; García-Soriano, L.; Hueto-Escobar, A.; Mileto, C.; Vegas, F. Proposal for Zeolite Waste from Fluid Catalytic Cracking as a Pozzolanic Addition for Earth Mortars: Initial Characterisation. Coatings 2025, 15, 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121408

Barros Magdalena M, García-Soriano L, Hueto-Escobar A, Mileto C, Vegas F. Proposal for Zeolite Waste from Fluid Catalytic Cracking as a Pozzolanic Addition for Earth Mortars: Initial Characterisation. Coatings. 2025; 15(12):1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121408

Chicago/Turabian StyleBarros Magdalena, María, Lidia García-Soriano, Alicia Hueto-Escobar, Camilla Mileto, and Fernando Vegas. 2025. "Proposal for Zeolite Waste from Fluid Catalytic Cracking as a Pozzolanic Addition for Earth Mortars: Initial Characterisation" Coatings 15, no. 12: 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121408

APA StyleBarros Magdalena, M., García-Soriano, L., Hueto-Escobar, A., Mileto, C., & Vegas, F. (2025). Proposal for Zeolite Waste from Fluid Catalytic Cracking as a Pozzolanic Addition for Earth Mortars: Initial Characterisation. Coatings, 15(12), 1408. https://doi.org/10.3390/coatings15121408