1. Introduction

Fossil fuels are a primary driver of global climate change, accounting for over 75% of annual global greenhouse gas emissions [

1]. These emissions have accelerated global warming and induced drastic climatic changes, posing substantial risks to human survival and development [

2]. Reducing reliance on fossil fuels has thus become a critical global priority [

3]. As a clean, sustainable energy carrier, hydrogen energy has garnered increasing attention, and its large-scale development and utilization are spearheading a profound energy revolution [

4].

Among various hydrogen production technologies, water electrolysis via the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) is a promising industrial route due to its sustainability and immense application potential [

5]. Conventional HER catalysts, such as platinum-based materials, exhibit high catalytic efficiency but are restricted from large-scale deployment by their high cost and scarce reserves [

6,

7,

8]. Consequently, the development of non-noble metal HER catalysts has emerged as a key research focus. Traditional binary alloys struggle to achieve flexible regulation of hydrogen adsorption free energy due to their fixed compositions and chemical stoichiometries. In contrast, the synergistic catalysis of multiple principal metals in high-entropy alloys (HEAs) offers a novel solution to this challenge.

In recent years, HEAs have been extensively investigated for electrocatalytic water splitting [

9,

10]. Guo et al. [

11] developed a core–shell FeCoNiMoW@FeCoNiOOH electrocatalyst via in situ self-reconstruction, which exhibited long-term stability, with an overpotential of 246 mV at a current density of 10 mA·cm

−2. Liu et al. [

12] synthesized nitrogen-doped carbon nanofiber-supported boron-doped dendritic HEAs, which exhibited superior HER activity and durability: nitrogen-doped carbon nanofibers enhanced electrical conductivity, boron-doped dendritic structures increased the number of active sites, and the integration of carbon fibers with HEAs accelerated electron/ion transport and lowered kinetic barriers. He et al. [

13] synthesized a body-centered cubic (BCC) FeCoNiWMo HEA through powder sintering (featuring random atomic occupancy), which displayed outstanding HER performance: overpotentials of 35 mV (alkaline electrolyte) and 81 mV (acidic electrolyte) at 10 mA·cm

−2, with sustained stability for 48 h (no detectable changes in morphology, crystal structure, or composition). Zhang et al. [

14] fabricated small-sized (~34 nm) PdFeCoNiCu HEA nanoparticles via an oil-phase method (≤250 °C). In alkaline HER, this catalyst achieved an overpotential of 18 mV at 10 mA·cm

−2, a Tafel slope of 39 mV·dec

−2, and a mass activity of 6.51 A·mg

−1 Pd, which is the highest among reported non-Pt-based catalysts. However, existing research still suffers from critical limitations: first, most non-noble metal HEA catalysts are either powder-based (requiring binders that cause particle detachment during long-term operation) or rely on noble metal components to enhance catalytic activity; second, few studies have explored fully non-noble metal HEA thin films, and their HER performance in complex electrolytes (e.g., mixed alkaline-saline or sulfide-containing systems) and under variable temperature conditions remains largely uncharacterized.

Traditional nanoscale powder catalysts typically require loading onto glassy carbon electrodes (GCEs) via binders. During long-term operation, binders undergo swelling, resulting in poor adhesion of nanoscale particles. Additionally, gas bubbling during HER causes detachment of catalyst nanoparticles, which degrades catalytic efficiency or even leads to complete catalyst failure. As a self-supported thin-film electrode, the FeCoNiMoCu HEA offers distinct advantages for HER applications: it eliminates the issue of nanoparticle detachment caused by binder degradation, as no binders are required. Meanwhile, its porous structure endows the thin-film catalyst with a large specific surface area, significantly enhancing electrochemical reaction efficiency [

15].

In this study, equiatomic Fe, Co, Ni, Mo, and Cu powders were used to prepare FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin-film electrodes. The HER performance of the electrode was evaluated in four electrolyte systems: 0.5 M H2SO4 (acidic), 1.0 M KOH (alkaline), simulated seawater (0.5 M NaCl), and a mixed solution of 0.5 M Na2S + 1.0 M KOH. Additionally, the influence of electrolyte temperature on HER activity was investigated, and the activation energy (Ea) of the electrode in each electrolyte system was calculated to elucidate the reaction kinetics.

2. Experimental Procedures

2.1. Preparation of Thin Film Electrodes and Electrochemical Testing

Equiatomic Fe, Co, Ni, Mo, and Cu powders (purity ≥ 99.5%, particle size: 5–10 μm) were homogenized by planetary ball milling at 400 r·min−1 (ball-to-powder ratio = 10:1, cemented carbide balls) for 48 h to yield a homogeneous powder mixture. Subsequently, 8 g of the mixed powder and 2 g of polyvinyl butyral (PVB) were dispersed in 30 mL of ethanol, followed by heating at 50 °C with sustained agitation to yield a homogeneous slurry. The slurry was uniformly cast onto a pre-cleaned quartz glass plate (10 cm × 10 cm) using a doctor blade with a controlled gap of 200 μm, resulting in a wet film thickness of 180 ± 10 μm. After being left at room temperature for 2 h to facilitate solvent evaporation, the dried coating was carefully peeled from the quartz substrate. The thickness of the dried pre-sintered film was measured as 45 ± 5 μm using a digital micrometer at 5 randomly selected points. The peeled pre-sintered coating was placed in a vacuum sintering furnace (Model: ST-VF-S-2/65, Shintek, Beijing, China) for densification. The optimized sintering process was conducted as follows:

Evacuate to a base pressure of 5 × 10−3 Pa before heating;

Raised to 300 °C at 10 °C·min−1 (30 min), held for 60 min;

Continue heating to 600 °C at a rate of 10°C·min−1, and held for 120 min;

Further increased to 900 °C over 60 min, held for 120 min;

Cooled naturally to room temperature to obtain the FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin-film electrode.

The thickness of the final FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin film was 20 ± 3 μm. A 1 cm × 1 cm square was cut from the central region of the thin film as the working electrode, and its active area was verified using an optical microscope. A platinum (Pt) sheet was used as the counter electrode, and a reference electrode matching the electrolyte system (a reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) for 0.5 M H

2SO

4, a silver/silver chloride (Ag/AgCl) electrode for 1.0 M KOH and simulated seawater, and a mercury/mercury oxide (Hg/HgO) electrode for the mixed Na

2S-KOH electrolyte). All measured potentials were converted to the RHE scale using the corresponding conversion equations:

Before electrochemical testing, the working electrode surface was cleaned to remove surface impurities, and the electrolyte was degassed with high-purity nitrogen for 30 min. Cyclic voltammetry (CV) tests were conducted using an electrochemical workstation in the four aforementioned electrolyte systems. For CV tests, the open-circuit potential (OCP) of the thin-film electrode in each electrolyte was used as the reference potential, with a scanning range of OCP ± 0.05 V and scanning rates varying from 5 mV·s−1 to 60 mV·s−1. The double-layer capacitance (Cdl) of the catalyst was calculated from the non-faradaic region of the CV curves. For linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) tests, a scanning rate of 3 mV·s−1 was adopted. For electrode stability evaluation, after the initial LSV test, the electrode was subjected to 1000 CV cycles at a scanning rate of 50 mV·s−1 in the same electrolyte; LSV was then retested, and the curves before and after cycling were compared to assess stability. Each set of experiments was repeated three times to ensure data reliability.

2.2. Characterization

The crystal structure of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode was analyzed using an X-ray diffractometer (Model: Dmax 2500VB, Rigaku Corporation: Tokyo, Japan) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.541 Å). The microstructure and elemental distribution of the electrode were observed using a scanning electron microscope (Model: JSM-5600LV, JEOL Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) coupled with an energy-dispersive X-ray spectrometer (Model: Octane SDD, EDAX Inc., Mahwah, NJ, USA). The chemical states of the constituent elements in the electrode were characterized using an X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Model: AMICUS, ORTEC, Oak Ridge, TN, USA).

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterization of Thin Film Electrodes

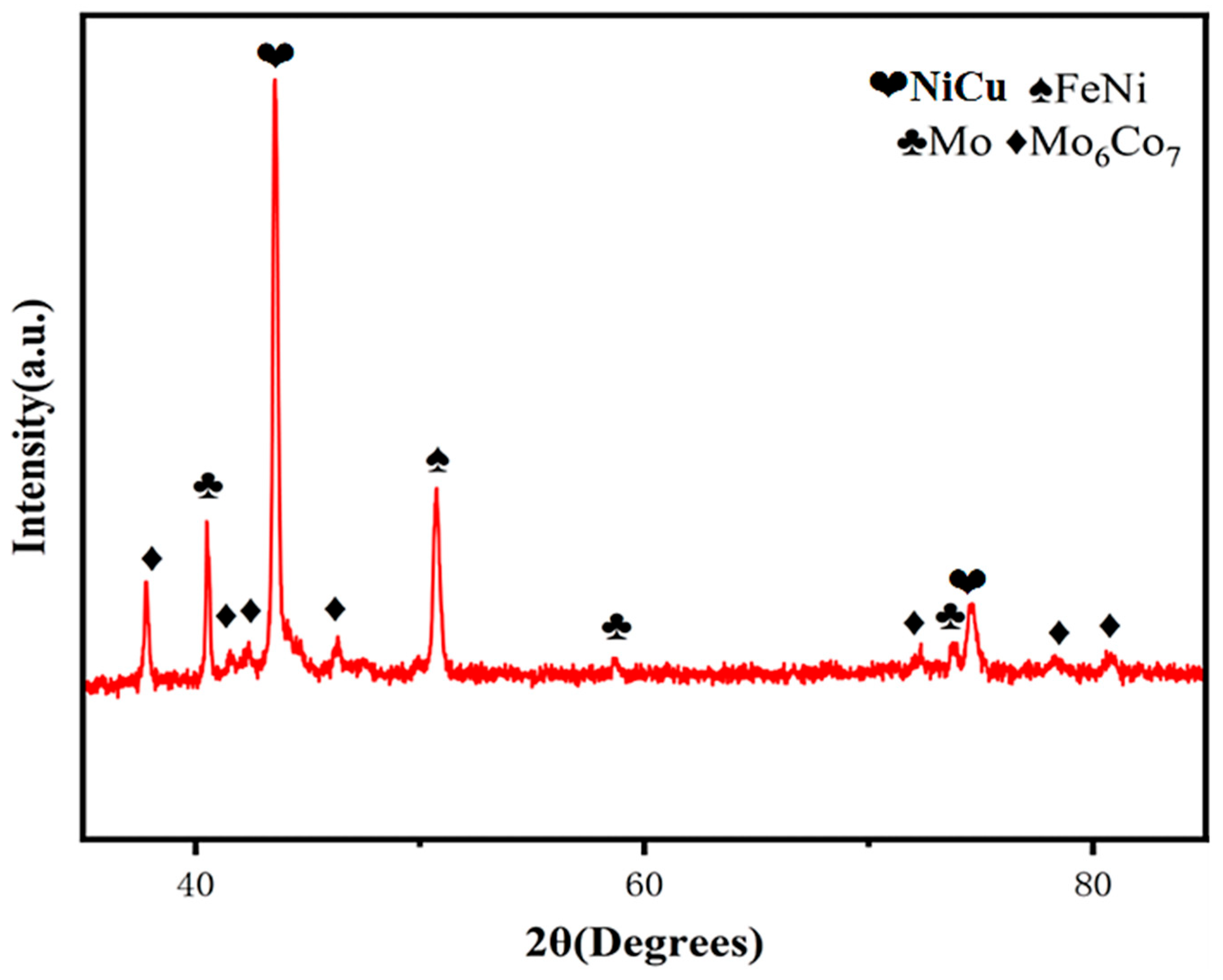

Figure 1 presents the XRD pattern of the FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin-film electrode. As shown in the pattern, Ni and Fe form a solid solution, resulting in the formation of the NiFe intermetallic compound, while Mo exhibits limited solid solubility in Co, leading to the formation of Mo

6Co

7 [

16]. Due to the limited solubility of Mo in Fe, Ni, and Cu (attributed to large differences in atomic size and electronegativity), the unincorporated Mo atoms exist as an independent elemental Mo phase in the system. Additionally, Ni and Cu form an infinite solid solution to generate NiCu.

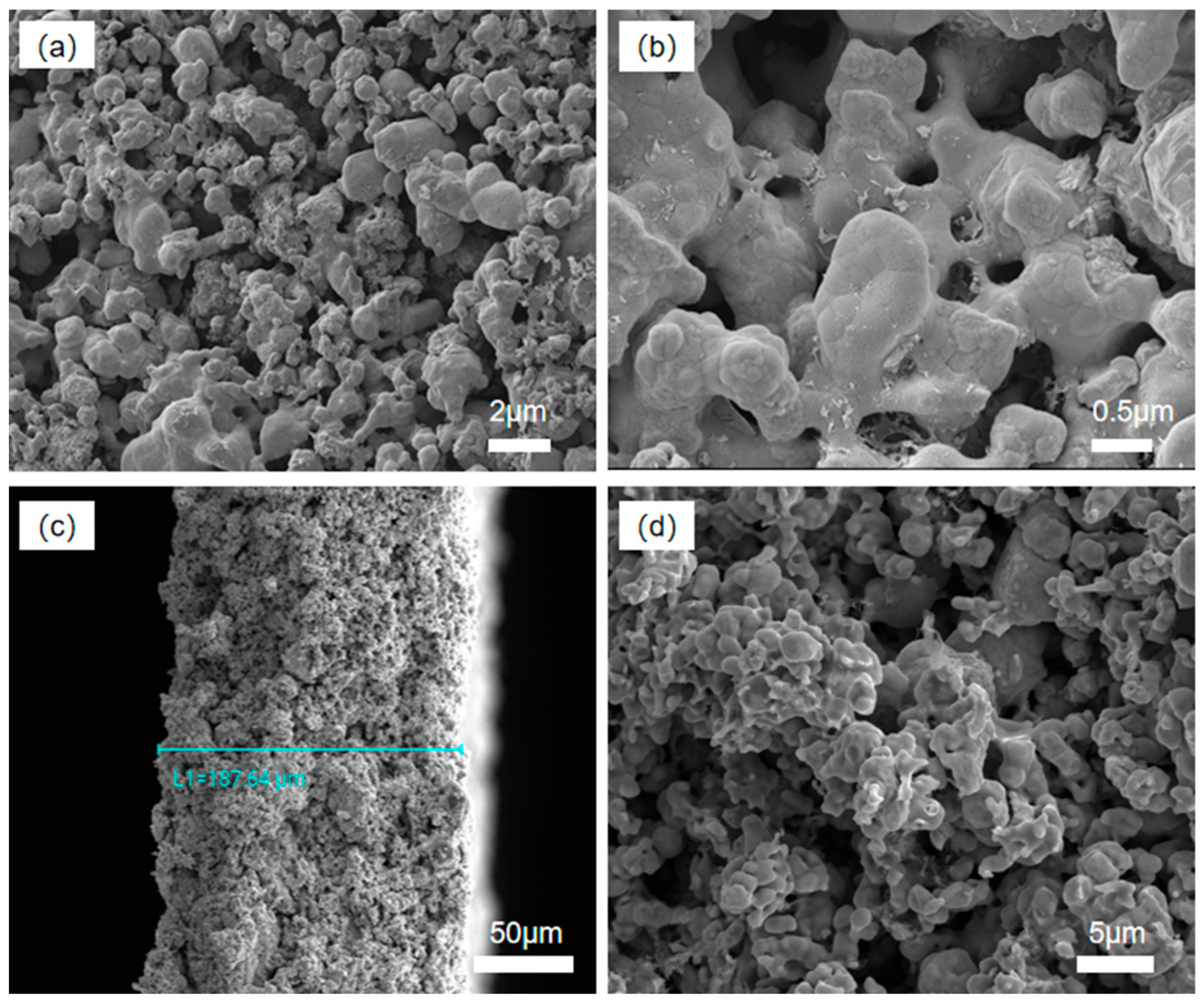

Figure 2 presents SEM images of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode at different magnifications and viewing angles. These images clearly show a complete three-dimensional porous structure, with partial melting at particle connections forming stable sintering necks and abundant pores. As shown in

Figure 2a, at low magnification, the overall morphology of the sample exhibits a continuous porous network with uniform pore distribution and no obvious defects.

Figure 2b reveals that at high magnification, the microscopic details show tight particle connections, with pore sizes ranging from nanometers to micrometers and diverse shapes with complex geometric features.

Figure 2c shows that the average thickness of the electrode material is about 187.64 μm, and abundant irregular and interconnected pores are observed throughout the layer.

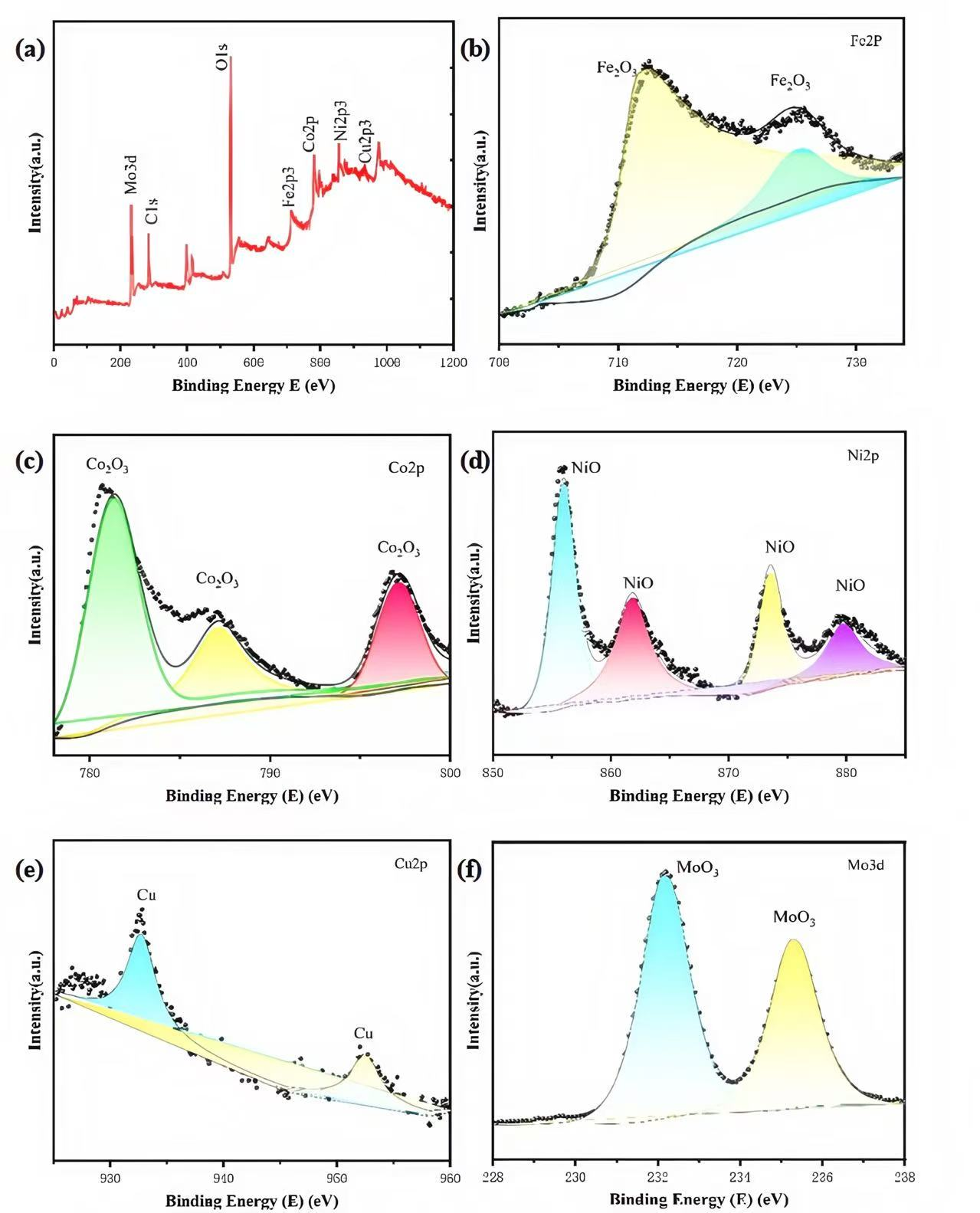

Figure 3 presents the XPS spectra of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode. It can be seen that the sample contains metallic elements and their corresponding oxides. As shown in

Figure 3b, the Fe 2p spectrum can be deconvoluted into two peaks at 711.6 eV (Fe 2p

3/2) and 724 eV (Fe 2p

1/2), both corresponding to Fe

2O

3.

Figure 3c,d present the Co 2p and Ni 2p spectra, respectively, indicating the formation of corresponding oxides for both elements. As illustrated in

Figure 3e, the Cu 2p XPS spectrum displays two distinct peaks at 952.5 eV (Cu 2p

1/

2) and 932.5 eV (Cu 2p

3/

2), which are both assigned to metallic copper. For the Mo 3d spectrum presented in

Figure 3f, the two characteristic peaks located at 232.2 eV and 235.6 eV are attributed to molybdenum oxides (MoO

x). This observation indicates the presence of partial oxide species on the sample surface, potentially arising from exposure to the ambient atmosphere during sample handling.

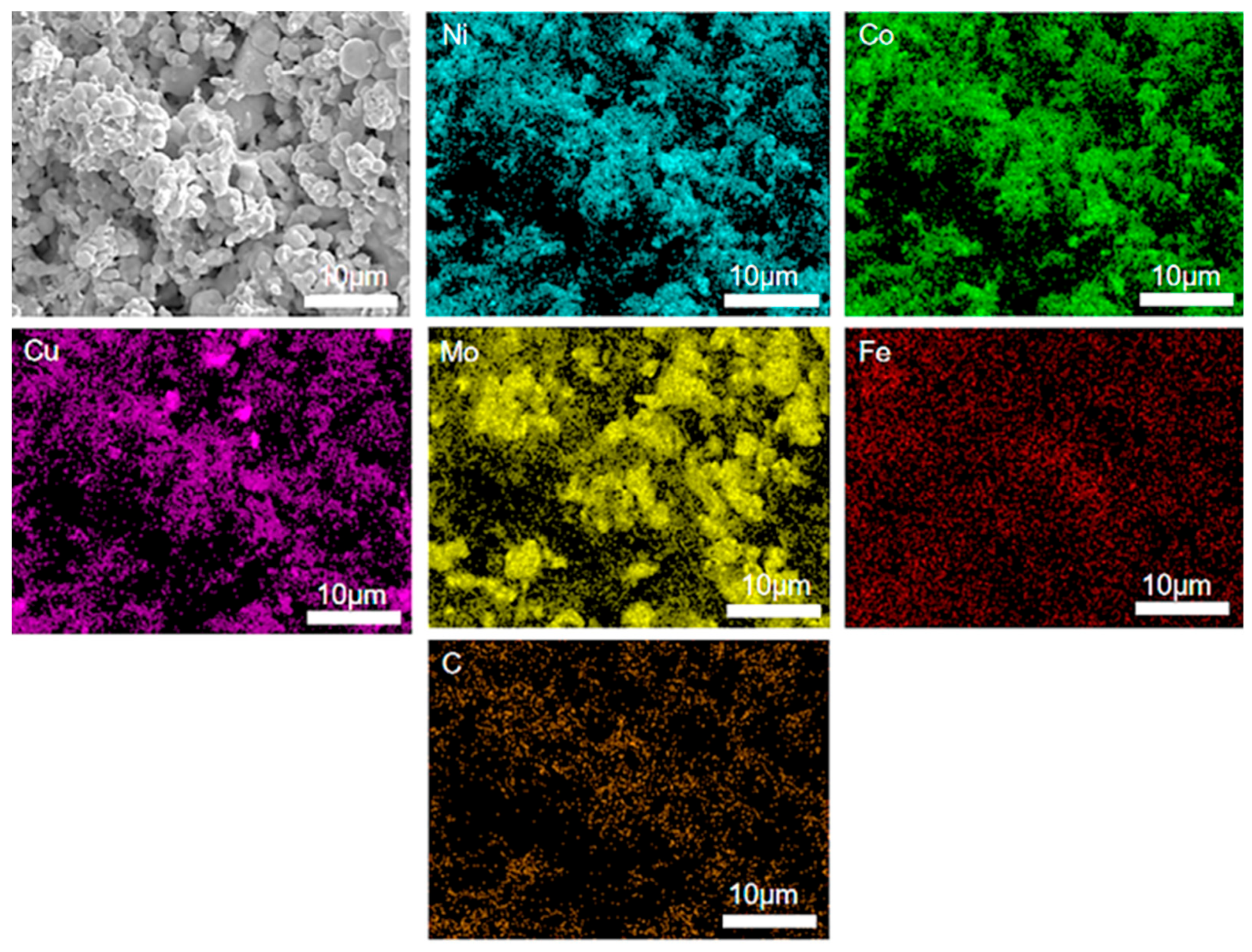

Figure 4 shows the EDS pattern of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode. It can be observed that the outer layer of the electrode film mainly comprises Mo, Ni, Co, Cu, Fe, and C. The elemental distribution within the film is relatively uniform, with no detectable segregation of any element. The carbon present in the film originates from the incomplete decomposition of PVB during the sintering process.

3.2. Hydrogen Evolution Performance in Acidic Solution

In an acidic environment, the high hydrogen ion (H

+) concentration facilitates proton reduction at the cathodic region, promoting their conversion to hydrogen gas and enhancing the electrochemical HER rate. HER in acidic media not only improves reaction efficiency but also enhances overall energy conversion efficiency and catalyst stability, all of which are critical for industrial applications [

17].

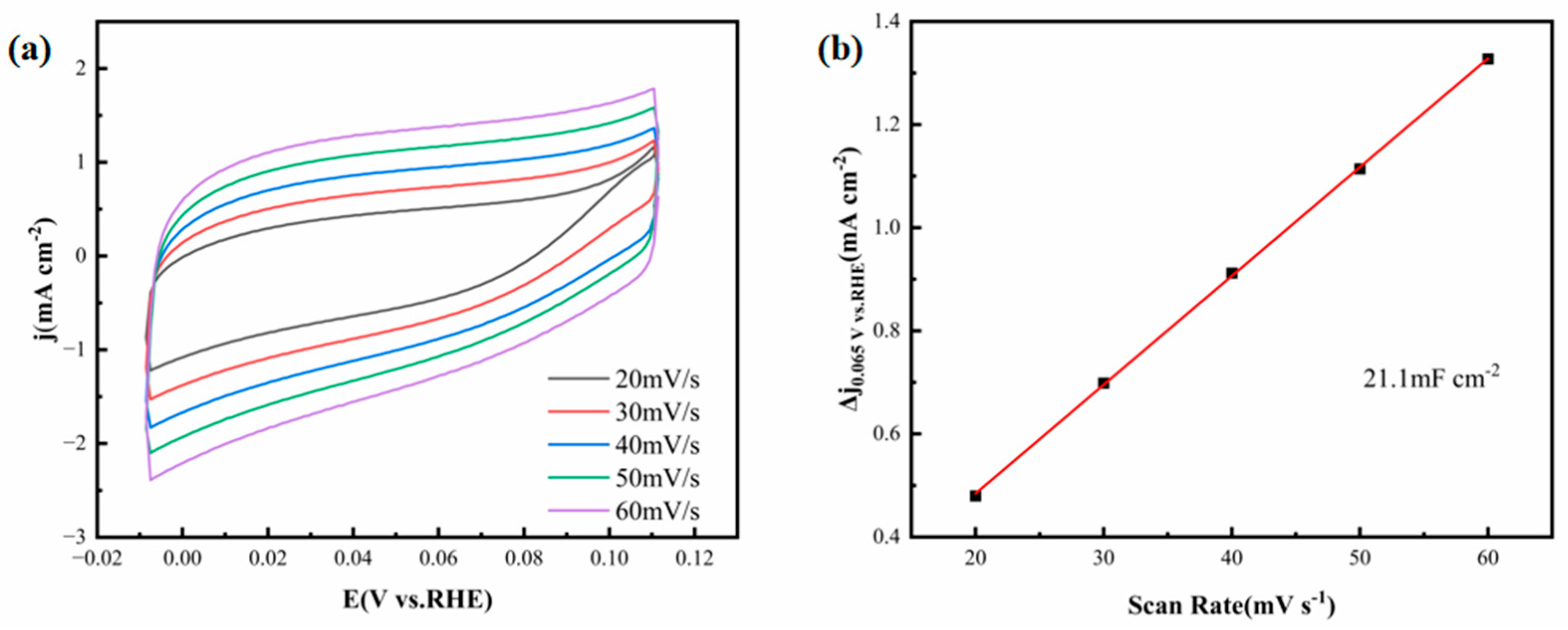

Figure 5a presents CV curves recorded under different scan rates in a 0.5 M H

2SO

4 electrolyte solution. These curves reflect the electrochemical behavior of the catalyst when subjected to varying scan rate conditions, and the smooth cyclic curves in each region indicate stable double-layer capacitive currents. The electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) of the electrode is a critical performance indicator for evaluating the catalytic performance of the electrode. Since the C

dl is proportional to ECSA [

18], the linear fitting slope in

Figure 5b is indicative of the C

dl of the thin-film electrode, which can be employed to estimate ECSA. As shown in

Figure 5b, the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode exhibits a C

dl of 21.1 mF·cm

−2, a value comparable to that of commercial Pt/C catalysts (31.8 mF·cm

−2) under the same experimental parameters [

19]. This result confirms that the FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin film possesses a relatively large electrochemically active surface area, providing abundant active sites for the HER process [

18].

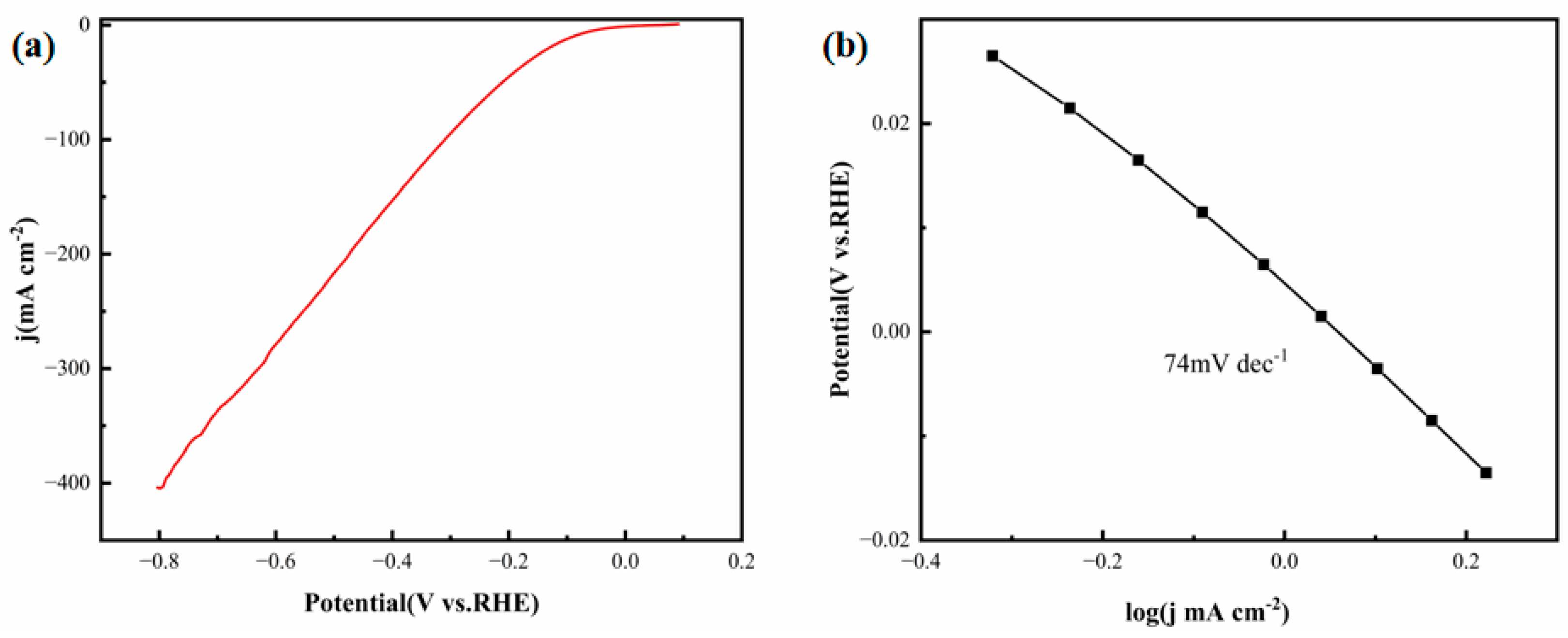

To further evaluate the HER activity of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in acidic media, LSV measurements were performed.

Figure 6a,b show the LSV polarization curves and corresponding Tafel plots of the electrode in 0.5 M H

2SO

4, respectively. The FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode achieves a current density of 10 mA·cm

−2 at an overpotential of 93 mV, which is significantly superior to most reported non-noble metal HER catalysts. Notably, Yang et al. [

19] developed a TiVCT@NF hybrid electrode that necessitates an overpotential of 151 mV to reach the same current density (10 mA·cm

−2), the acidic electrolyte—representing a 62% increase compared to that of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode. As a critical indicator of HER kinetics, the Tafel slope reflects the rate-determining step (RDS) of the reaction. Typically, Tafel slopes below 30 mV·dec

−1 correspond to the Tafel reaction (RDS: H* + H* → H

2); slopes ranging from 30 to 40 mV·dec

−1 are indicative of the Heyrovsky-Tafel mechanism (RDS: H* + H

+ + e

− → H

2); and slopes between 40 and 120 mV·dec

−1 are characteristic of the Heyrovsky-Volmer mechanism (RDS: H

+ + e

− → H*) [

20]. The FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode demonstrates a Tafel slope of 74 mV·dec

−1 (

Figure 6b), suggesting that its HER process in acidic media follows the Heyrovsky-Volmer mechanism. By contrast, the TiVCT

x@NF material reported by Yang et al. features a Tafel slope of 116 mV·dec

−1, which is 57% higher than that of the FeCoNiMoCu thin film. This difference confirms that the FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin film possesses faster HER kinetics under the same overpotential conditions, which is attributed to the synergistic electronic modulation of its multi-element components.

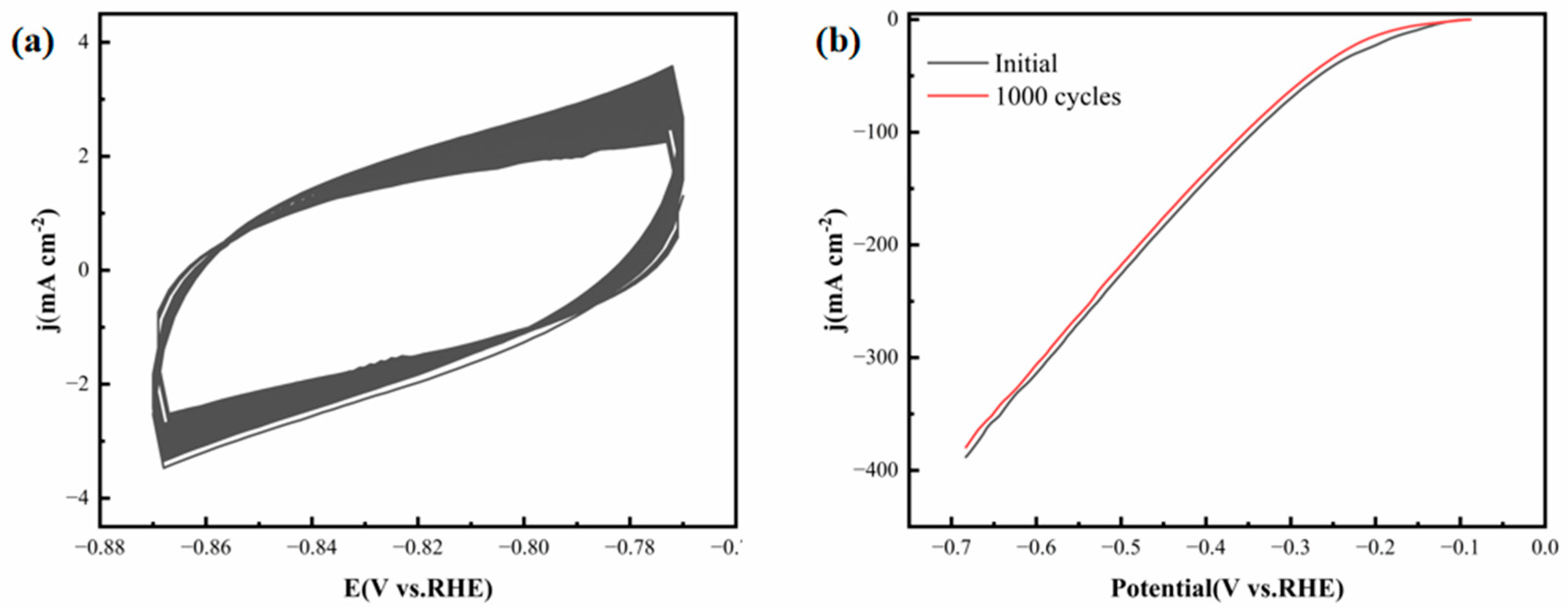

Catalyst stability is a decisive factor for practical applications, as it directly affects the service life and economic feasibility of electrochemical systems. To evaluate the stability of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode, an accelerated aging test was carried out via 1000 consecutive CV cycles (scan rate: 50 mV·s

−1) in 0.5 M H

2SO

4 electrolyte.

Figure 7a shows the CV curves recorded during the cycling process, and

Figure 7b provides a comparison of the LSV polarization curves prior to and following the 1000-cycle test. The CV curves maintain a consistent shape and capacitive current throughout the cycling test, and the post-cycling LSV curve exhibits negligible degradation. Notably, the overpotential required to attain a current density of 10 mA·cm

−2 shifts by less than 3 mV after 1000 cycles. These findings collectively verify the outstanding long-term stability of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in acidic electrolyte systems, which can be attributed to its robust alloy structure and strong adhesion of the thin film (eliminating particle detachment issues associated with powder catalysts).

3.3. Hydrogen Evolution Performance in Alkaline Solution

Compared to acidic conditions, alkaline conditions are less corrosive to electrolytes and their internal electrodes. This characteristic contributes to lower costs and easier maintenance for the relevant equipment [

21,

22].

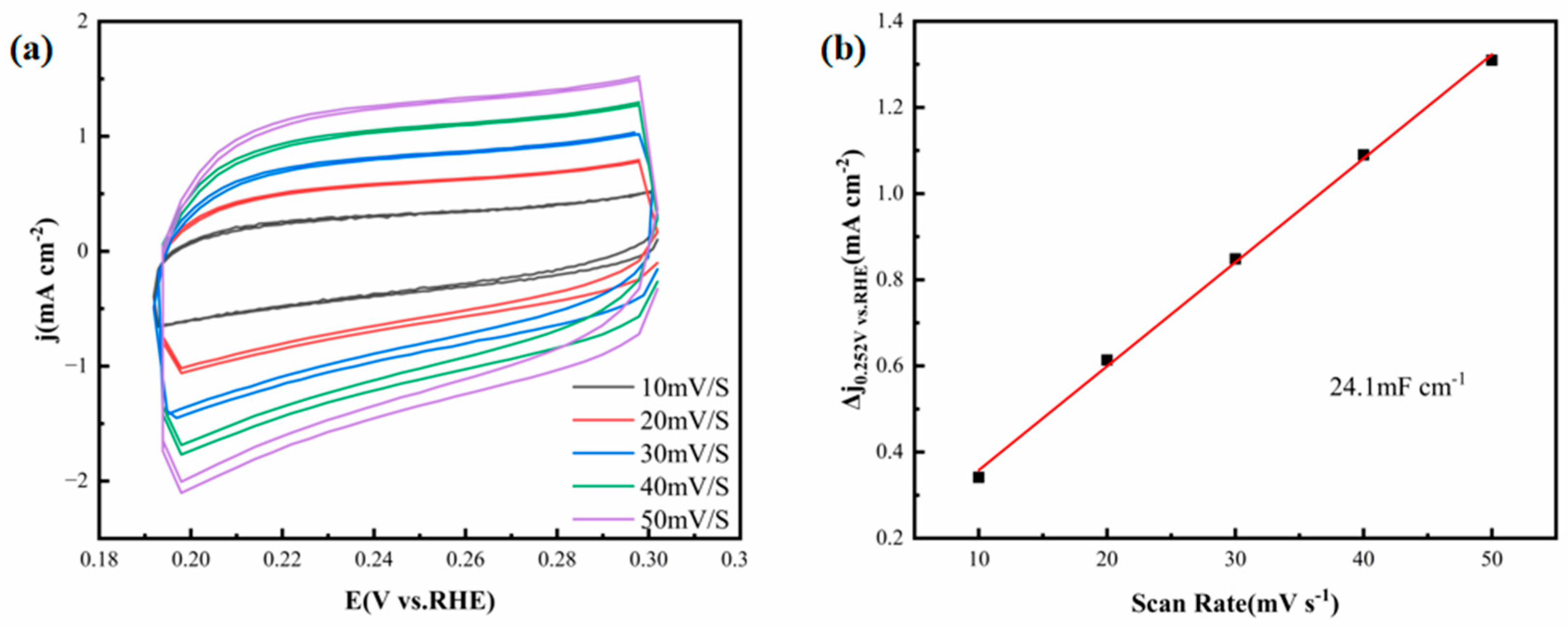

Figure 8a depicts the CV curves of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode acquired in 1.0 M KOH solution, with scan rates varying between 10 and 50 mV·s

−1. The smooth and symmetric cyclic curves across all scan rates indicate stable double-layer capacitive behavior without significant faradaic side reactions, which reflects the excellent electrochemical reversibility of the electrode in alkaline media.

As illustrated in

Figure 8b, the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode possesses a C

dl of 24.1 mF·cm

−2, a value notably higher than that of most documented HEA-based HER catalysts. For instance, Alamdari et al. [

23] prepared a CoCuFeNiMnMo HEA thin film with a C

dl of only 6.99 mF·cm

−2—approximately 71% lower than that of the FeCoNiMoCu thin film. This superior C

dl value confirms that the FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin film possesses a larger electrochemically active surface area in alkaline media, providing more abundant active sites for the HER process.

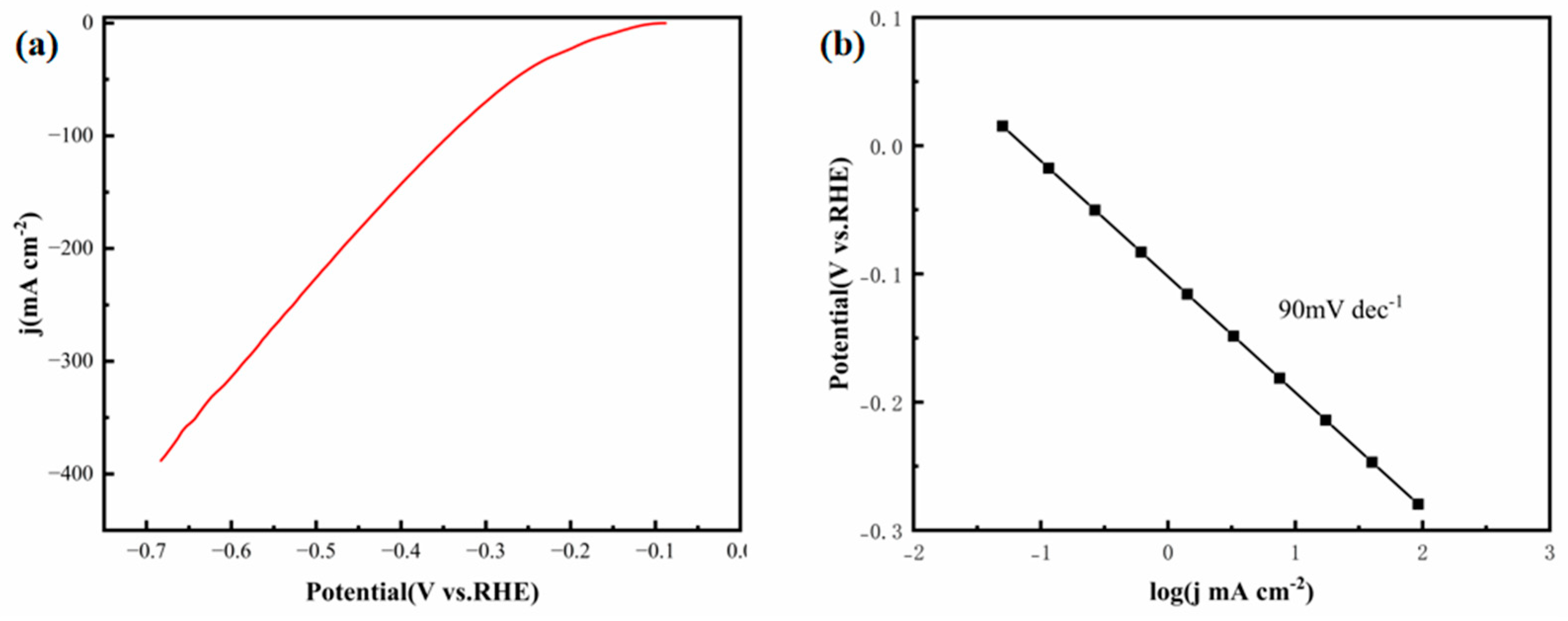

Figure 9a,b show the LSV polarization curves and corresponding Tafel plots of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in 1.0 M KOH, respectively. The electrode achieves a current density of 10 mA·cm

−2 at an overpotential of 158 mV, a performance that is significantly superior to that of most reported non-noble metal and HEA HER catalysts. For instance, the CoCuFeNiMo HEA thin-film electrode reported by Alamdari et al. [

23] requires an overpotential of 286 mV to reach 10 mA·cm

−2 (79% higher than that of the FeCoNiMoCu thin film), while the CuCrFeNiCoP HEA thin-film electrode demonstrates an overpotential of 195 mV at the same current density, corresponding to a 23% increase [

24]. Although the overpotential of the FeCoNiMoCu thin film (158 mV) is marginally higher than that of commercial Pt/C catalysts (~35 mV), it outperforms most non-noble metal-based catalysts, demonstrating remarkable performance advantages in alkaline HER [

25]. The Tafel slope of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in 1.0 M KOH is 90 mV·dec

−1 (

Figure 9b), indicating that its alkaline HER follows the Heyrovsky-Volmer mechanism. Compared with similar HEA catalysts, the CuCrFeNiCoP and CoCuFeNiMo HEA thin films exhibit Tafel slopes of 118 mV·dec

−1 and 125 mV·dec

−1, respectively, corresponding to respective increases of 31% and 39% relative to the FeCoNiMoCu thin film.

As illustrated in

Figure 10a, the figure presents CV curves of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode recorded during 1000 cycles in 1.0 M KOH solution.

Figure 10b presents the polarization curves of the electrode before and after 1000 CV cycles in the aforementioned alkaline solution. As shown in the figures, the hydrogen evolution polarization curve after 1000 cycles exhibits negligible deviation from the initial curve. Moreover, the overpotential required to achieve a current density of 10 mA·cm

−2 shows minimal change after cycling, indicating that the FeCoNiMoCu high-entropy thin-film electrode possesses excellent stability in the alkaline electrolyte.

3.4. Hydrogen Evolution Performance in Simulated Seawater

The ocean covers 71% of the surface of the Earth, rendering seawater a renewable and copious resource [

26]. Employing clean energy sources like offshore wind power to directly produce hydrogen from seawater can obviate procedures such as seawater desalination, catalyst addition, transportation, and pollution treatment. The 0.5 mol·L

−1 sodium chloride in seawater contributes to enhanced electrolytic hydrogen production efficiency by providing conductivity [

27]. Based on these advantages, seawater hydrogen production technology exhibits significant application potential and development prospects in the energy field. In this study, a mixed solution of 1.0 M KOH and 0.5 M NaCl was used to simulate seawater for investigating the hydrogen evolution performance of the prepared thin-film electrode in seawater.

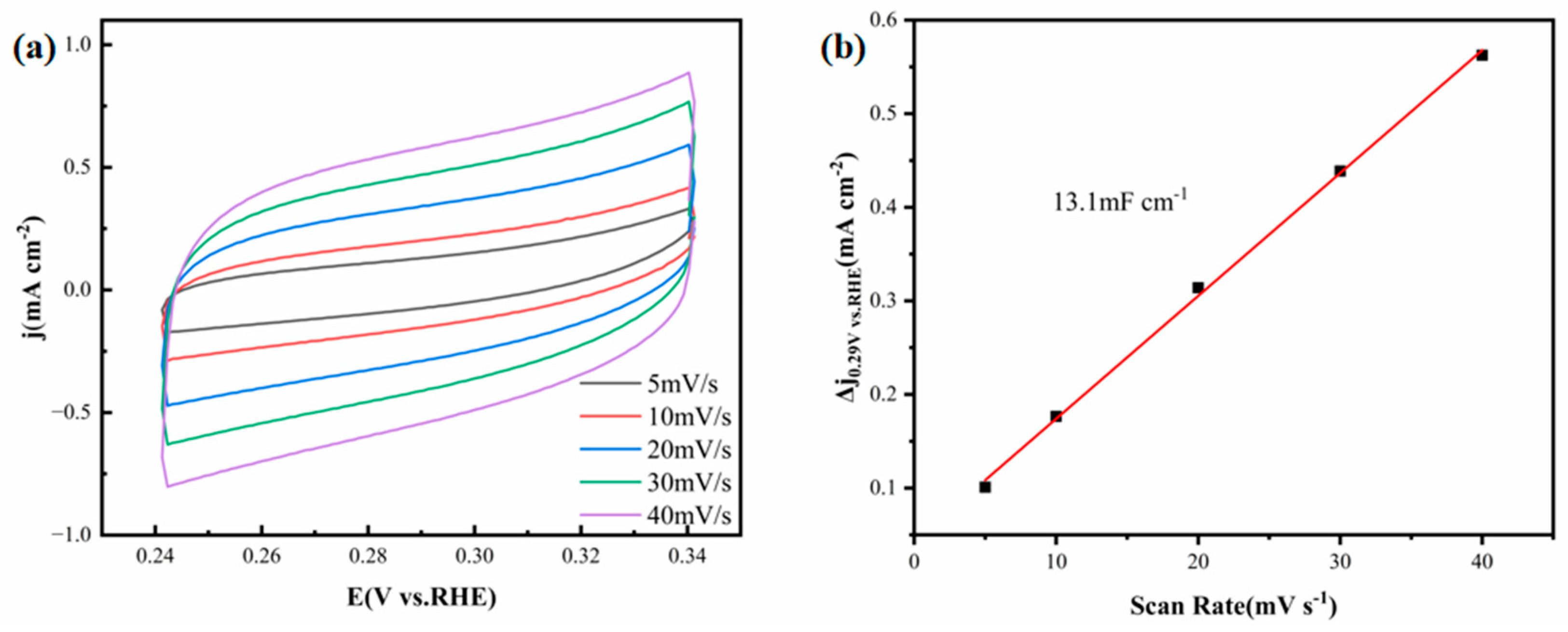

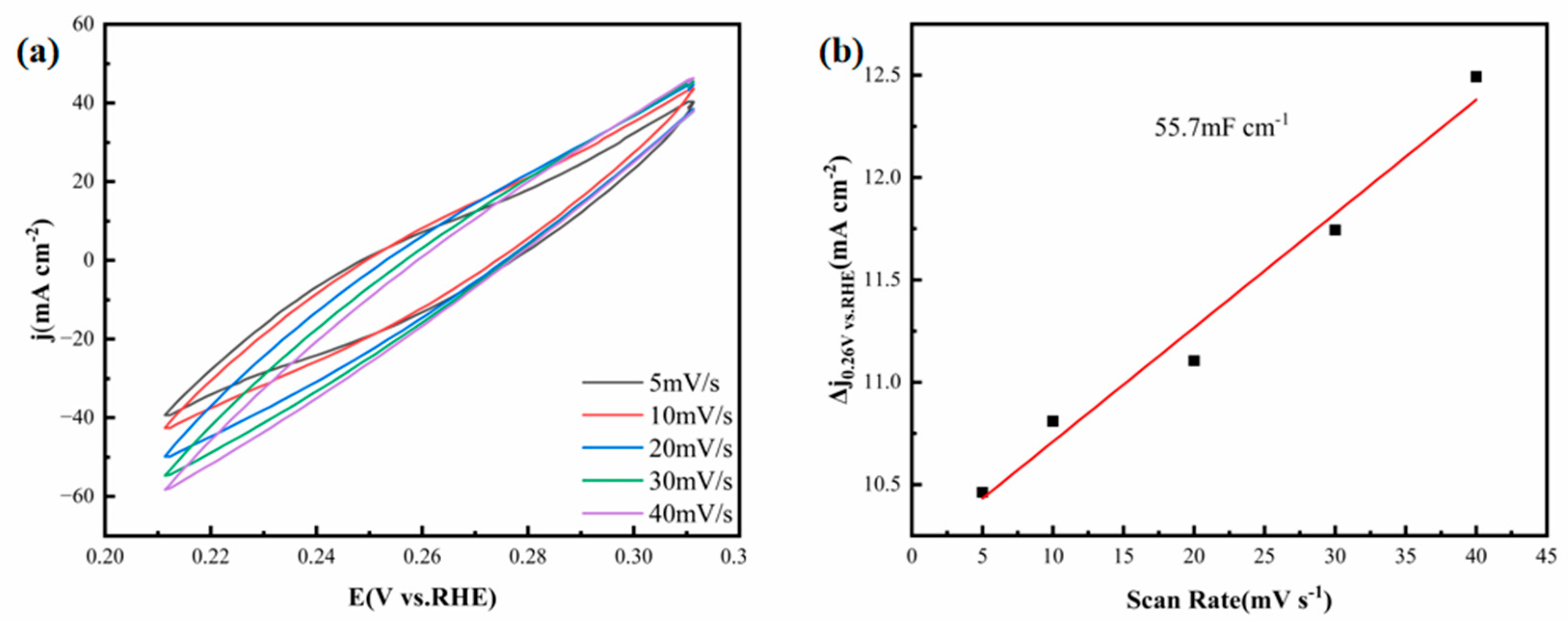

Figure 11a presents the CV curves of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in simulated seawater at scan rates varying from 5 to 40 mV·s

−1. These curves maintain good smoothness and symmetry across all scan rates, indicating stable double-layer capacitive behavior without obvious faradaic side reactions. This reflects the excellent electrochemical reversibility of the electrode in high-salinity alkaline media.

Figure 11b is a plot of current density versus scan rate, from which the C

dl of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode is 13.1 mF·cm

−2. Compared with reported HER catalysts, this C

dl value is remarkable. For example, a unique porous CoP/Co

2P heterostructured electrode prepared by Liu et al. [

28] exhibits a C

dl of 10.02 mF·cm

−2 in seawater medium, which is lower than that of the FeCoNiMoCu thin film electrode.

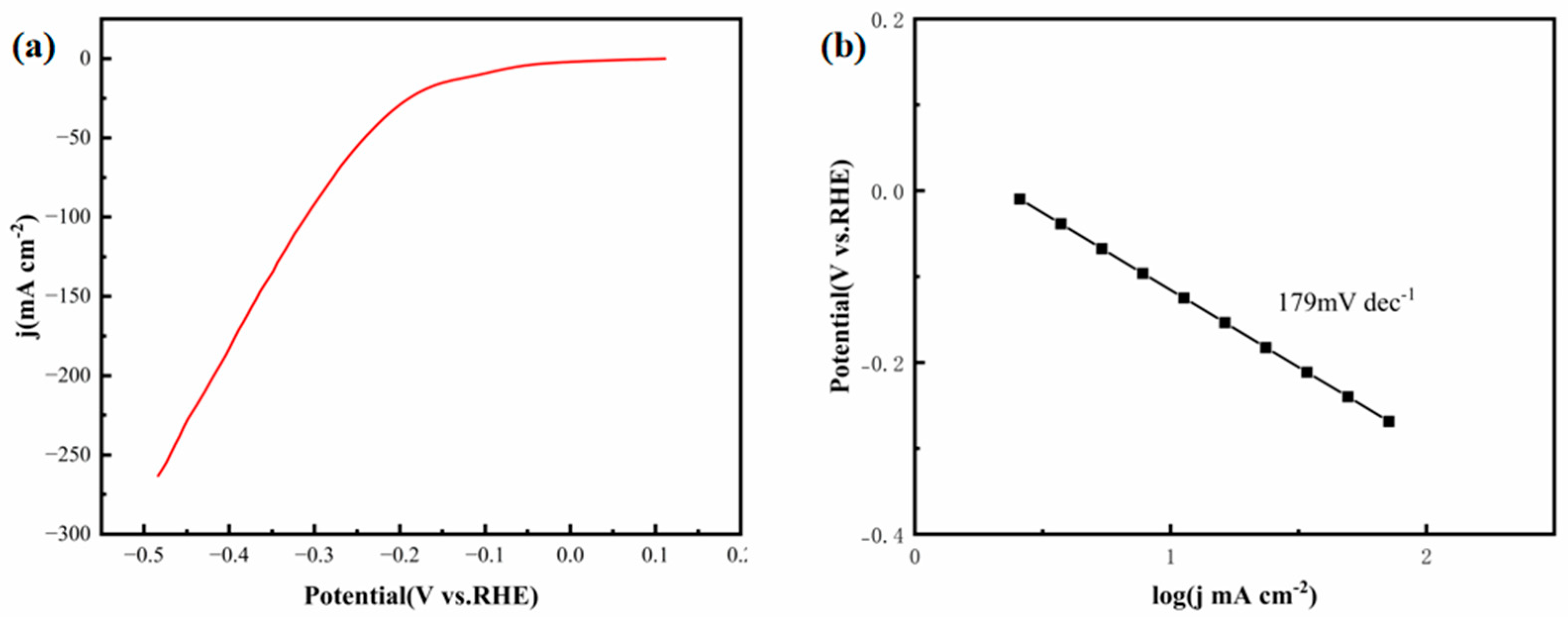

Figure 12a,b show the LSV polarization curves and corresponding Tafel plots of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in simulated seawater, respectively. The FeCoNiMoCu electrode achieves a current density of 10 mA·cm

−2 at an overpotential of 108 mV, a performance that is remarkably superior to most documented non-noble metal catalysts for seawater HER. For instance, Liu et al. [

28] reported a porous CoP/Co

2P heterostructured electrode that requires an overpotential of 454 mV to reach the same current density (10 mA·cm

−2) in simulated seawater—representing a 321% increase compared to that of the FeCoNiMoCu thin film. This notable performance advantage stems from the synergistic effects of the HEA multi-element composition: Mo and Ni enhance water dissociation capacity, while the corrosion resistance of Cu and the optimized electronic structure of Co/Fe alleviate the adverse impacts of high chloride ion concentrations. As presented in

Figure 12b, the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode exhibits a Tafel slope of 179 mV·dec

−1 in simulated seawater. Although this value is marginally higher than that of the CoP/Co

2P electrode (104 mV·dec

−1), it is crucial to emphasize that the FeCoNiMoCu thin film achieves a substantially lower overpotential under practical current density conditions (10 mA·cm

−2) [

29].

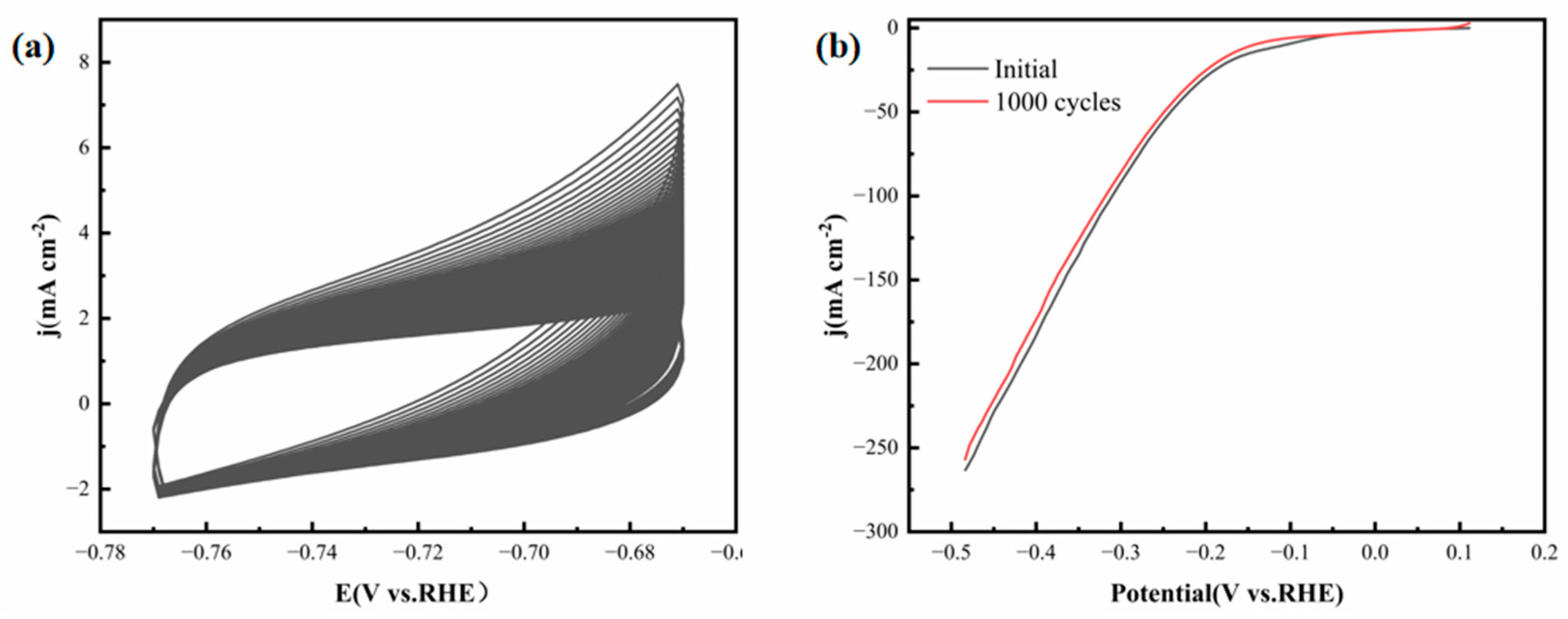

Figure 13a illustrates the CV curves of 1000 CV cycles carried out in seawater.

Figure 13b presents the polarization curves of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in seawater before and after 1000 CV cycles. As depicted in the figures, after 1000 CV cycles, the measured hydrogen evolution polarization curve is almost identical to the initial state, and there is no significant difference in the overpotential required for the electrode to reach 10 mA·cm

−2 before and after cycling. This clearly demonstrates that the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode exhibits excellent structural and electrochemical stability in simulated seawater environments.

3.5. Hydrogen Evolution Performance in Sodium Sulfide Solution

Hydrogen production from sodium sulfide solutions is characterized by its scalability and ease of continuous operation. This not only yields a favorable economies of scale but also eliminates the need for noble-metal catalysts, thereby significantly reducing the cost of hydrogen production [

30]. Within the scope of this research, the HER performance of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode was investigated in a mixed electrolyte consisting of 1.0 M Na

2S and 1.0 M KOH.

Figure 14a presents the CV curves of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in the aforementioned sodium sulfide-based mixed electrolyte, with scan rates spanning from 5 mV·s

−1 to 40 mV·s

−1. The cyclic curves within each scan interval are relatively smooth, suggesting that the thin film electrode demonstrates stable double-layer capacitive current behavior.

Figure 14b is a graph depicting the relationship between current density and scan rate. As can be seen from this graph, the C

dl of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode is found to be 55.7 mF·cm

−2.

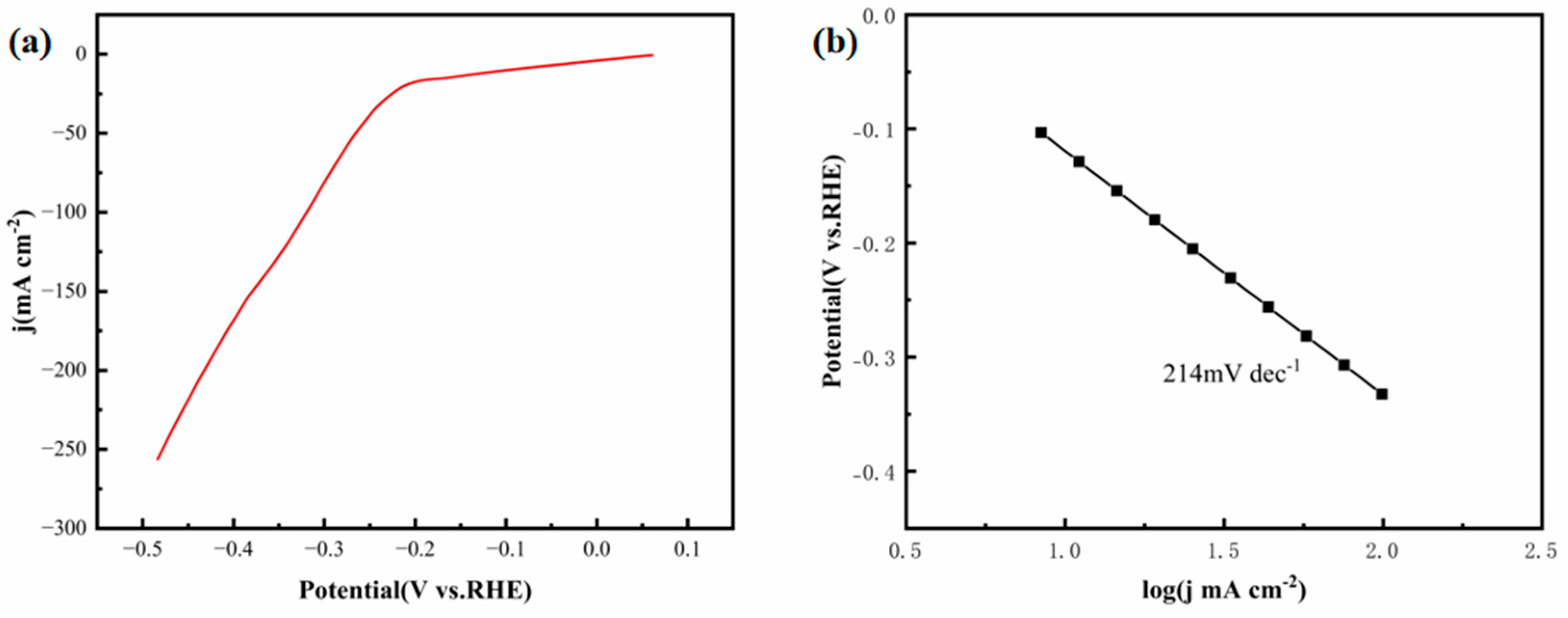

Figure 15a depicts the LSV curve of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in the aforementioned sodium sulfide-based mixed electrolyte. As indicated in the figure, when the hydrogen evolution current density reaches 10 mA·cm

−2, the overpotential of the electrode is 99 mV.

Figure 15b represents the Tafel slope plot, from which the Tafel slope of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode is determined to be 214 mV·dec

−1.

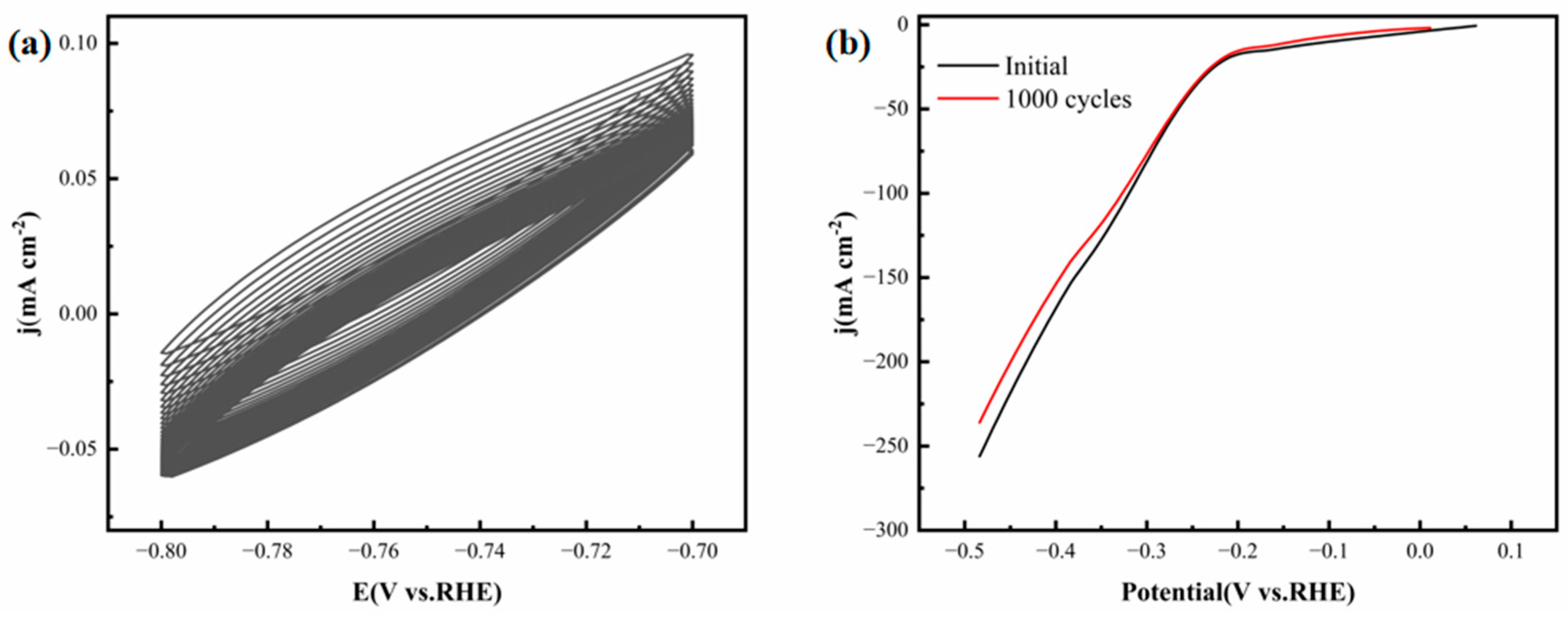

Figure 16a displays the scan curves of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode during 1000 CV tests conducted in the sodium sulfide solution. In contrast,

Figure 16b presents a comparison of the hydrogen evolution polarization curves of the electrode prior to and following the cycling process. The test results reveal that after 1000 CV cycles, the measured hydrogen evolution polarization curve closely resembles its initial form. Moreover, the overpotential necessary for the electrode to achieve 10 mA·cm

−2 demonstrates no substantial alteration before and after cycling. These observations signify that the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode exhibits outstanding structural and electrochemical stability within the sodium sulfide solution environment.

3.6. Hydrogen Evolution Performance in Different Temperatures

The effect of temperature on HER performance in electrolytes is primarily manifested in the following aspects: At low temperatures, the increased electrolyte viscosity impedes ion migration and decreases mass transfer efficiency. Concurrently, it exacerbates charge transfer resistance, requiring higher overpotential to maintain the reaction [

31,

32]. Conversely, a moderate increase in temperature can lower the reaction energy barrier and boost the kinetic rate by activating the active sites of the catalyst [

33]. Nevertheless, prolonged exposure to high temperatures readily induces electrolyte decomposition, degradation of the catalyst structure, or corrosion of the support, which significantly impairs the stability of the material [

34].

Consequently, optimizing the electrolyte system requires a comprehensive assessment of the coupling effects between temperature and mass transfer, reaction, and decay. By establishing a quantitative correlation between temperature, performance, and lifetime, it becomes feasible to guide the design of electrode materials adapted to specific working conditions.

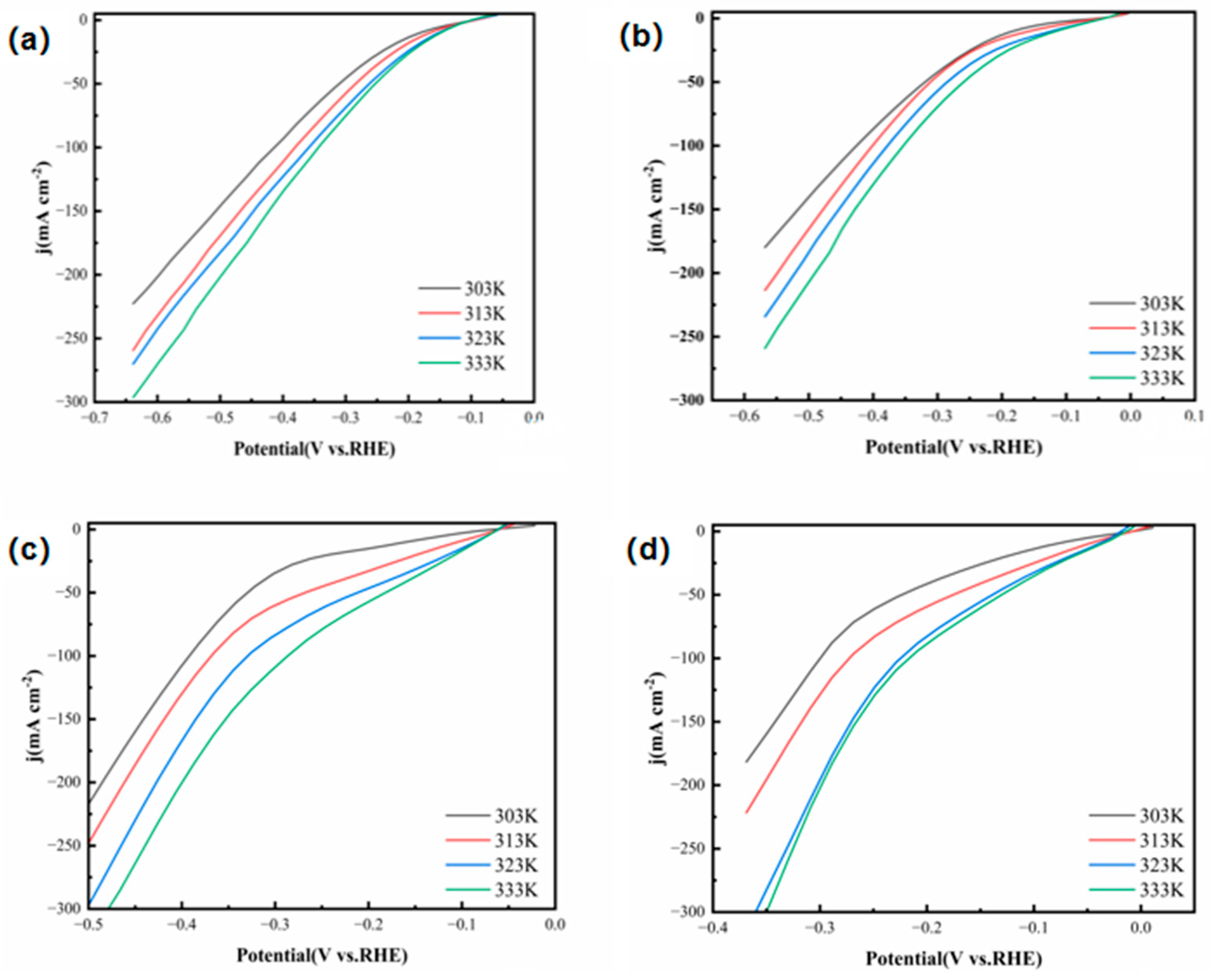

In this work, an in-depth investigation was conducted into the effects of different electrolyte temperatures on the hydrogen evolution performance of the prepared FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode in four types of electrolytes.

Figure 17 shows the LSV test results of the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode at different temperatures. The results reveal a consistent hydrogen evolution trend across all four electrolyte solutions: as the electrolyte temperature increases, the hydrogen evolution catalytic performance of the electrode significantly improves, specifically manifested as a sharp increase in the hydrogen evolution current density with rising temperature, accompanied by a notable reduction in the hydrogen evolution overpotential. Therefore, moderate elevation of the electrolyte temperature can effectively enhance the hydrogen evolution catalytic activity.

3.7. Comparison of Activation Energy in Different Electrolytes

To further investigate the electrode process kinetics, the

Ea of the FeCoNiMoCu high-entropy thin-film electrode in the four aforementioned electrolyte solutions was calculated using the Arrhenius equation (the results are shown in

Table 1):

In the equation,

is the exchange current density;

denotes the frequency factor; Ea represents the activation energy; R corresponds to the molar gas constant; while T stands for the absolute temperature.

The data in

Table 1 summarizes the C

dl, Tafel slope, potential at 10 mA·cm

−2 (E

-10mA·cm−2), and

Ea of the FeCoNiMoCu electrode in different solutions. In the acidic system (0.5 M H

2SO

4), the C

dl is 21.1 mF·cm

−2, the Tafel slope is 74 mV·dec

−1, E

-10mA cm−2 is 93 mV, and the

Ea is only 8.46 kJ·mol

−1. In the alkaline system (1.0 M KOH), the C

dl slightly increases to 24.1 mF·cm

−2, while the Tafel slope increases to 90 mV·dec

−1, E

-10mA cm−2 positively shifts to 158 mV, and the activation energy rises to 10.59 kJ·mol

−1. When 0.5 M NaCl or 1.0 M Na

2S is added to the 1.0 M KOH solution, the C

dl exhibits a trend of “first decreasing and then increasing” (13.1 mF·cm

−2 and 55.7 mF·cm

−2), but both the Tafel slope (179 mV·dec

−1 and 214 mV·dec

−1) and

Ea (18.23 kJ·mol

−1 and 20.74 kJ·mol

−1) increase significantly. This indicates a notable slowdown in reaction kinetics, accompanied by a substantial increase in charge transfer resistance and reaction energy barrier.

The performance of the HER is primarily determined by the Tafel slope and Ea: a smaller Tafel slope indicates more rapid reaction kinetics, whereas a lower Ea signifies a smaller energy barrier required for the reaction. The acidic H2SO4 electrolyte exhibits the lowest Tafel slope and Ea, indicating low charge transfer resistance and significant kinetic advantages. Although the alkaline KOH electrolyte has a slightly higher Cdl, its Tafel slope and Ea are both higher than those of the acidic system, and E-10mA cm−2 shows a positive shift (requiring higher overpotential to drive the reaction). Although the alkaline mixed electrolytes with added NaCl or Na2S alter the double-layer structure (e.g., a significant increase in Cdl is observed in the Na2S + KOH mixture), their kinetic parameters (Tafel slope and Ea) significantly degrade compared to the pre-mixed state. In summary, the 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte demonstrates the best hydrogen evolution performance, with its superior kinetic characteristics (low Tafel slope and low Ea) providing significant advantages in the HER.

4. Conclusions

The FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin-film electrode was successfully prepared via coating and vacuum sintering techniques. The phase composition, surface morphology, and other key characteristics of the electrode were analyzed by characterization techniques such as XRD, SEM, EDS, and XPS. Meanwhile, the hydrogen evolution performance of the high-entropy alloy thin film electrode was systematically investigated in four distinct electrolyte systems (0.5 M H2SO4, 1.0 M KOH, a mixed electrolyte of 0.5 M NaCl and 1.0 M KOH, and a mixed solution of 1.0 M Na2S and 1.0 M KOH). Additionally, the hydrogen evolution behavior of the electrode was evaluated under different test temperatures.

(1) XRD analysis reveals the presence of NiFe and Mo6Co7 intermetallic compounds in the electrode system, in addition to elemental Cu and Mo. SEM images clearly show a complete three-dimensional porous structure with partially melted particle junctions forming stable sintering necks and abundant pores distributed throughout the structure. XPS spectra confirm the coexistence of metallic elements and their corresponding oxides in the sample. EDS mapping reveals that the outer layer of the electrode film is mainly composed of Mo, Ni, Co, Cu, Fe, and C, with relatively uniform elemental distribution and no significant segregation.

(2) HER performance and practical value: Comparative analysis with reported HER catalysts and reproducibility validation (each test was repeated three times;

Table 1) demonstrates that the FeCoNiMoCu HEA thin-film electrode exhibits outstanding HER performance across all four electrolyte systems. It achieves a remarkable balance between high catalytic activity and broad electrolyte adaptability, filling the research gap in HEA thin-film catalysts with superior performance in diverse complex electrolyte environments. This work provides a new insight for the design of low-cost, high-stability HER electrodes for practical applications. Notably, the FeCoNiMoCu thin-film electrode delivers the optimal HER performance in acidic solution compared to other electrolytes: it exhibits the lowest Tafel slope (74 mV·dec

−1), the smallest

Ea (8.46 kJ·mol

−1), and low charge transfer resistance, demonstrating significant advantages in reaction kinetics.

(3) Regarding limitations, although the Cdl is slightly higher in the alkaline system, the Tafel slope, activation energy, and driving overpotential are all higher than those in the acidic system. In seawater and sodium sulfide solutions, despite the altered double-layer structure, the Tafel slope and the Ea increase significantly, leading to a noticeable decline in hydrogen evolution performance.