Abstract

Background/Objectives: The global emergence of carbapenem resistance is a major public health concern. Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli, key zoonotic agents causing human campylobacteriosis, are mainly isolated from poultry, their primary host. Their increasing resistance in animals and humans highlights the risk of gene transfer. This study investigates the molecular mechanisms of carbapenem resistance in 287 avian Campylobacter spp. isolates from Tunisia within a One Health approach. Methods: Antibiotic susceptibility of 287 carbapenem-resistant isolates, including 147 C. jejuni and 140 C. coli, was determined according to CLSI. All isolates were screened by PCR for genes encoding the most reported carbapenemases, including VIM, IMP, NDM and OXA-48. Eleven multidrug-resistant (MDR)/carbapenem-resistant C. coli isolates were selected to determine their clonal lineage by Multilocus sequence typing (MLST). Results: All isolates were susceptible to imipenem, but resistance to meropenem and ertapenem were observed in 60.71% and 35.71% of C. coli isolates, respectively, versus 13.6% in C. jejuni for each antibiotic. The blaVIM, blaNDM and blaOXA-48 genes were detected in 15, 8, and 19 of the 20 C. jejuni isolates, respectively. However, for C. coli, 53, 12, and 15 isolates harbored blaVIM, blaNDM and blaOXA-48 genes, respectively. The eleven (MDR)/carbapenem-resistant C. coli isolates belonged to a unique ST sequence type ST13450. Conclusions: We report for the first time the emergence of blaVIM, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48 genes in Campylobacter spp. isolates of poultry origin highlighting possible horizontal transfer of these genes to pathogenic Gram-negative bacteria of the poultry’s microbiota.

1. Introduction

Antibiotic resistance (AR) has emerged as a major public health threat over the past two decades [1,2]. The spread of AR is driven by both antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB) and mobile genetic elements carrying antibiotic resistance genes (ARGs) [3,4]. The overuse and misuse of antibiotics in human medicine and livestock production are key factors selecting for and disseminating ARB and ARGs, not only in clinical and agricultural settings but also in wildlife and environmental compartments such as soil and water [5]. Commensal bacteria colonizing livestock have been shown to act as important reservoirs of ARB and ARGs, which can spread to humans through direct contact, the food chain, or the surrounding environment [6]. These bacteria include zoonotic Enterobacterales (e.g., Escherichia coli, Salmonella spp.), Staphylococcus spp. (e.g., Staphylococcus aureus), Enterococcus spp., and Campylobacter spp. [6,7].

Campylobacter species are a leading cause of neonatal enteric disease in developing countries and a major contributor to foodborne diarrheal illness worldwide. Campylobacteriosis is an important zoonosis, with infection primarily acquired through the consumption of contaminated food, particularly poultry, or water, as well as through direct contact with infected food-producing animals or their carcasses [8]. More than 90% of human Campylobacter infections are attributed to C. jejuni and C. coli. Campylobacteriosis is typically a self-limiting illness characterized by diarrhea, fever, and abdominal pain. However, in severe cases, Campylobacter infections can lead to serious complications such as bloodstream infections (BSI), reactive arthritis, and Guillain–Barré syndrome (GBS) [9]. For severe infections, fluoroquinolones (e.g., ciprofloxacin) and macrolides (erythromycin, azithromycin) are the most commonly prescribed treatments for human campylobacteriosis; additionally, tetracycline and gentamicin remain effective options for systemic Campylobacter infections [10]. However, due to the excessive use of antibiotics in livestock, particularly in the poultry industry, high rates of antibiotic resistance have been reported in Campylobacter isolates [10,11]. This escalation has contributed to a growing pool of multidrug-resistant (MDR) isolates, particularly among strains associated with poultry production and contaminated food sources. The emergence of MDR Campylobacter poses a growing public health challenge, as it limits treatment options and increases the risk of severe or persistent infections [10,11].

Carbapenems (imipenem, meropenem, ertapenem) are considered a valuable antimicrobial class for managing complicated cases of campylobacteriosis that do not respond to first-line therapy [12]. Although carbapenem resistance in Campylobacter has historically been considered rare, recent reports from Europe and Asia indicate the emergence of carbapenem-resistant Campylobacter species, most frequently C. coli, often linked to prolonged selective antibiotic pressure, even though the underlying molecular mechanisms remain poorly defined [13,14]. Clinical and experimental studies have increasingly documented carbapenem non-susceptible C. coli and C. jejuni strains, particularly in immunocompromised patients and in poultry-associated isolates [14,15]. Evidence from several investigations shows that carbapenem non-susceptibility can develop in vivo following extended meropenem or ertapenem therapy, associated with mutations in porA and overexpression of β-lactamases such as blaOXA-489, pointing to adaptive resistance mechanisms under antibiotic pressure [16]. Recent systematic reviews on antibiotic resistance in Campylobacter species from humans, animals, and water sources in South Africa reported moderate levels of resistance to carbapenems. In human isolates, resistance rates reached 15.3% for imipenem and 19.3% for meropenem [17]. Similar trends were observed in isolates from meat products (imipenem: 23%), cattle (imipenem: 21.47%), and drinking water (meropenem: 15.0%). In Europe, surveillance data from 2021 to 2022 revealed notably high rates of ertapenem resistance in C. coli from animal sources: 42.1% in broilers (2022), 58.1% in fattening turkeys (2022), and 29.1% in cattle under one year of age (2021), while resistance remained low in fattening pigs (1.1% in 2021). In contrast, C. jejuni showed much lower ertapenem resistance, with rates of 9.2%, 15.1%, 0.0%, and 1.2% in broilers, fattening turkeys, cattle under one year, and fattening pigs, respectively [18]. Taken together, although the global prevalence of carbapenem-resistant Campylobacter remains low, this phenomenon is concerning and underscore the need for reinforced surveillance in both clinical and food-chain settings. Several molecular mechanisms contributing to multidrug resistance in Campylobacter isolates have been described, including active efflux pumps, chromosomal mutations, and enzymatic antibiotic modification [11,15]. Of particular concern are the acquired resistance mechanisms involving antibiotics considered critical for treating infections caused by other major pathogens such as Enterobacterales, enterococci, and staphylococci. These include carbapenem and linezolid resistance, which position Campylobacter species as potential reservoirs and vectors of mobile genetic elements within the intestinal microbiota, affecting both commensal and pathogenic bacteria [19,20,21].

The present study aimed to determine the prevalence of carbapenem resistance among previously characterized C. jejuni and C. coli isolates recovered from poultry feces and environmental samples, and to identify the molecular mechanisms associated with this resistance. Additionally, clonal relatedness among carbapenem-resistant isolates was assessed using multilocus sequence typing (MLST) in eleven multidrug-resistant C. coli isolates.

2. Results

2.1. Antimicrobial Susceptibility

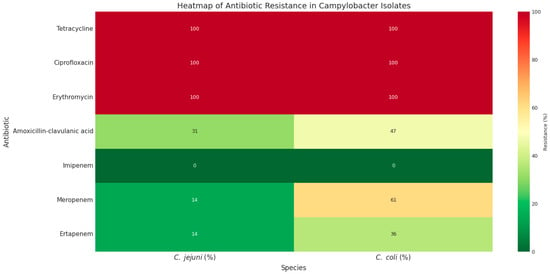

High rates of antibiotic resistance were observed among the 147 C. jejuni and 140 C. coli isolates (Table 1, Figure 1). All isolates were resistant to tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and erythromycin. Resistance to amoxicillin–clavulanic acid was detected in 47.14% of C. coli and 31.19% of C. jejuni isolates.

Table 1.

Frequencies of detected genes in the C. coli and C. jejuni isolates.

Figure 1.

The heatmap of phenotypic antibiotic resistance patterns of C. jejuni and C. coli isolates. Green to red colors represent low to high resistance rates.

Regarding carbapenem antibiotics, all isolates were susceptible to imipenem; however, resistance to meropenem and ertapenem was observed in 60.71% (n = 84) and 35.71% (n = 50) of C. coli isolates, respectively, compared with 13.6% (n = 20) of C. jejuni isolates for each antibiotic (Table 1). Notably, all 20 C. jejuni isolates were co-resistant to both meropenem and ertapenem. In contrast, among C. coli isolates, 15 (10.71%) were resistant only to ertapenem, 32 (22.85%) only to meropenem, and 93 (66.42%) were resistant to both ertapenem and meropenem (Figure 1).

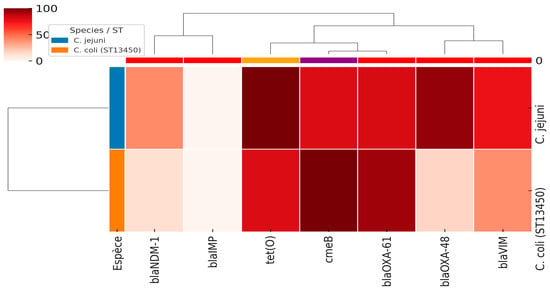

2.2. Genes Encoding Carbapenem Resistance and Other Resistance Genes

Among the four investigated genes encoding carbapenem resistance, the blaVIM, blaNDM-1, and blaOXA-48 genes were detected in 15/20, 8/20, and 19/20 of carbapenem-resistant C. jejuni isolates, respectively. However, for C. coli, 53, 12, and 15 isolates harbored blaVIM, blaNDM and blaOXA-48 genes, respectively (Table 1, Figure 2). Notably, blaIMP was absent in both species. Taken together, among the two species, blaVIM, blaNDM-1, and blaOXA-48 genes were detected in 68 (23.6%), 20 (6.9%), and 34 (13.9%) isolates, respectively.

Figure 2.

The heatmap of antimicrobial resistance genes in C. jejuni and C. coli (ST13450) isolates. The intensity of colors corresponds to the percentages of the detected genes (from 0 to 100%).

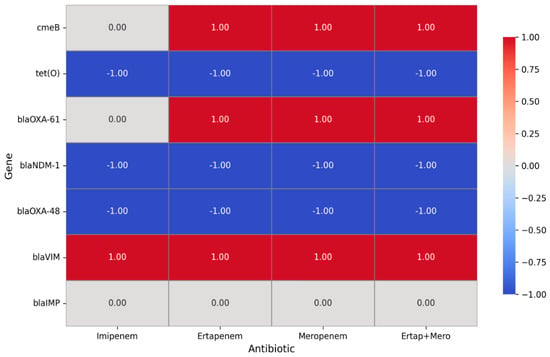

We performed chi-square and Fisher’s exact tests to evaluate the association between carbapenemase genes and carbapenem resistance phenotypes in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates. The presence of blaVIM, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48 genes was significantly associated with carbapenem resistance (p < 0.01). Furthermore, a logistic regression model including these three genes confirmed that blaVIM (OR = 16.5, p < 0.001), blaOXA-48 (OR = 6.7, p = 0.003), and blaNDM (OR = 4.0, p = 0.012) independently contribute to resistance (Figure 3). These results support a strong genotypic–phenotypic correlation, strengthening the causal link between carbapenemase genes and resistance phenotypes in Campylobacter spp. isolates.

Figure 3.

Correlation between carbapenem phenotypic resistance and carbapenemase resistance genes of Campylobacter isolates. A value of 1 represents a positive association, indicating that the presence of the gene is linked to increased resistance to the corresponding antibiotic. A value of −1 denotes a negative association, meaning that the gene is associated with increased sensitivity. A value of 0 reflects a neutral or inconclusive effect, suggesting that no clear relationship between the gene and the antibiotic was identified.

As investigated in our previous reports, Table 1 and Figure 2 illustrate the prevalence of major antimicrobial resistance genes among C. jejuni and C. coli isolates. In C. jejuni, tet(O) (100%) (Tetracycline resistance) and blaOXA-61 (81%) (bata-lactam resistance) were the most frequent resistance determinants, followed by cmeB (multi-drug efflux pump) (80%). In contrast, C. coli isolates exhibited 100% carriage of cmeB, together with high frequencies of blaOXA-61 (93%) and tet(O) (80%). These findings suggest that while both species share a high burden of efflux pump- and tetracycline-related resistance, there are interspecies differences in the distribution of β-lactamase and carbapenemase genes, which may reflect distinct evolutionary trajectories and selective pressures.

2.3. Clonality of Eleven C. coli Isolates

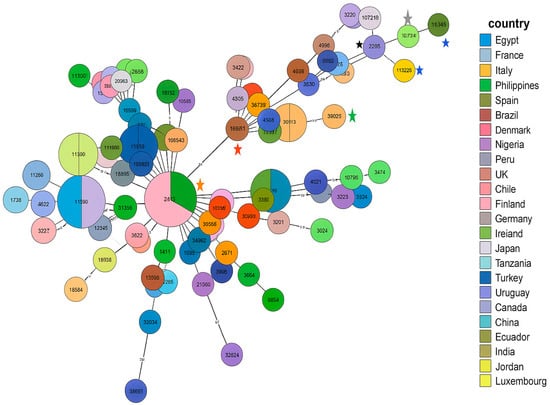

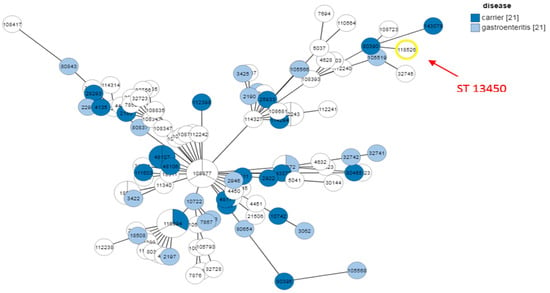

All isolates belonged to the same sequence type, ST13450, which represents a newly identified ST. The eleven selected isolates reflect the different profiles of our multidrug-resistant C. coli isolates and were compared with other international multidrug-resistant strains, first according to the country of origin and then according to the type of disease, as shown in Figure 4. Each node represents a sequence type (ST), with node size proportional to the number of isolates. Colors indicate the country of origin.

Figure 4.

MLST analysis of the MDR C. coli ST13450 isolates compared with international MDR strains. Blue asterisk (ID118526): our strain; black asterisk: C. coli npCAMYO (ST8168); gray asterisk: C. coli Campy469 (ST7718); green asterisk: C. coli J19 (ST11913); red asterisk: C. coli FR1p365B (ST832); water green asterisk: C. coli FSIS32309315 (ST7818); orange asterisk: strains from Spain and Ireland belonging to ST827 (CC828).

The ST13450 clone detected in our eleven meropenem/ertapenem-resistant C. coli isolates is genetically related to strains from multiple regions worldwide (Europe, North Africa, South America, Asia), illustrating their integration within a global clonal network. The most closely related strain (ID: 80390) belongs to the ST8168 (CC828), presented by a strain (named as C. coli npCAMYO) from Peru, isolated in 2012 from human stool (carrier) (https://pubmlst.org/bigsdb?db=pubmlst_campylobacter_isolates&page=query, accessed on 25 November 2025). It was also closely related to an environmental Brazilian C. coli isolate (ID:32745, named Campy469) isolated in 2004 and belonging to the singleton ST7718. Additional examples illustrating the diversity of origins and isolation times within the cluster containing the Tunisian-related isolates include C. coli J19 (ID:112241), isolated in 2011 from chicken offal or meat in the Philippines and classified as the singleton ST11913; and C. coli FSIS32309315 (ID:143078), isolated in 2023 from chicken in the USA and assigned to ST7818 (CC828).

As shown in Figure 4, the first strain in this cluster is C. coli FR1p365B (ID:114327), isolated in 2022 from chicken offal or meat in Chile and assigned to ST832 (CC828). This strain, along with the rest of the cluster, appears to have evolved from a lineage predominantly composed of strains from Ireland and Spain, most of which belong to ST827 (CC828), indicating a close genetic relationship and a potential shared evolutionary origin.

The disease-based MLST analysis in Figure 5 reveals that ST13450 isolates are found in both gastroenteritis cases and asymptomatic carriers. This dual distribution suggests that the clone has a pathogenic potential capable of causing clinical disease, while also persisting in a carrier state, which may facilitate its silent spread in human populations. Furthermore, the detection of related isolates in both animal sources (particularly chicken and chicken meat) and human samples supports the hypothesis of a zoonotic transmission cycle between animals and humans. These findings highlight the emerging and versatile nature of ST13450, demonstrating its ability to adapt to different hosts and clinical contexts. Therefore, this sequence type should be considered a potential zoonotic pathogen of public health concern.

Figure 5.

MLST analysis of ST13450 isolates according to clinical outcome and sources. The number 21 displayed next to ‘carrier’ and ‘gastroenteritis’ indicates the total number of strains included in each category, which were compared to our strain.

3. Discussion

Globally, antibiotic resistance has emerged as important problem for human and animal health. According to the One Health approach, the dissemination of antibiotic-resistant bacteria (ARB), as well as genes encoding antibiotic resistance (ARGs), occurs in the human/animal/environment interface. In addition, several studies have reported the intra-and interspecies spread of mobile genetic elements encoding ARGs, mainly plasmids, transposons, and integrons, among isolates belonging to the same species and genera as well as between different bacterial families. This phenomenon is specifically enhanced in environments containing multiple phyla of bacteria such as the animal and human microbiome of gastrointestinal tract as well as aquatic environments and polluted soils [5,22].

Recent studies highlight the widespread prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in poultry and their environments, with contamination rates up to 36.7% in certain meat samples and frequent multidrug resistance, particularly to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline, though erythromycin remains largely effective. Intensive poultry farming contributes significantly to environmental pollution and the dissemination of antibiotics, pathogens, and antimicrobial resistance through manure, aerosols, and contaminated water, posing risks to both farm workers and surrounding communities [23]. Farm-level factors, especially drinking water supply systems and rural suppliers, were identified as significant risk factors for Campylobacter colonization in broiler flocks, underscoring the importance of biosecurity and environmental management to control pathogen spread [24].

Carbapenem resistance in Gram-negative bacteria has become a global concern. Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Acinetobacter baumannii resistant to carbapenems are classified as “critical” priority pathogens in the 2017 World Health Organization (WHO) global priority list [25]. Recently, several studies have reported carbapenem-resistant Campylobacter spp. isolates. In Tunisia, our previous work characterized the antimicrobial susceptibility and identified genes associated with resistance in C. jejuni and C. coli isolates from avian feces and related environments [25,26]. However, these isolates were not previously tested for carbapenem susceptibility, as carbapenems are not a first-line treatment for Campylobacter infections and the bacteria were presumed to be susceptible to this class of antibiotics. In light of emerging carbapenem resistance reported in other countries, we have now evaluated these isolates for carbapenem susceptibility and investigated the genetic determinants underlying this resistance.

High rates of resistance were observed toward several antibiotics including tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, erythromycin, and amoxicillin–clavulanic acid. Interestingly, despite full susceptibility to imipenem, resistance to meropenem and ertapenem were observed in 60.71% and 35.71% of C. coli isolates, respectively, and in 13.6% (for each antibiotic) of C. jejuni isolates. In addition, it is worth noting that all the 20 carbapenem-resistant C. jejuni isolates were co-resistant to meropenem and ertapenem; however, for C. coli isolates, 10.71%, 22.85%, and 66.42%, were resistant to ertapenem only, meropenem only, and to both ertapenem and meropenem, respectively. Zhuo et al. (2024) [14] have recently reported a case of recurrent multi-drug resistant C. jejuni bloodstream infections in a Bruton’s X-linked agammaglobulinemia patient receiving prolonged ertapenem therapy. The genetic basis of this resistance was associated with nonsynonymous mutations in the porA gene, which encodes the major outer membrane protein (MOMP). Mutations in porA may decrease the permeability of carbapenem on the basis of charge or size [14,15,27]. Similarly, Maurille et al. (2024) [16] have reported the occurrence of in vivo resistant C. coli isolated from a patient with Good’s syndrome under meropenem treatment. Resistance was mediated by porA point mutation and overexpression of blaOXA-489 under meropenem treatment. Taken together, mutations in PorA protein are the main mechanism of in vivo selection for carbapenem resistance in Campylobacter spp. [20,28]. However, a few studies have recently reported the emergence of carbapenemases enzymes in Campylobacter. The blaOXA-185 gene was recently reported in one ertapenem-resistant C. jejuni isolate recovered from chicken liver (healthy chicken from Catalonia, Spain) [28]. This gene has also been identified in 49 C. jejuni isolates from various sources (human, food, retail chicken, and environment) in USA and UK (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pathogens/isolates/#AMR_genotypes:blaOXA-185; accessed 10 August 2025).

In Gram-negative bacteria, the common carbapenemase enzymes belong to the Ambler class A (e.g., KPC types), class B (e.g., VIM, IMP, and NDM types), and the class D OXA β-lactamases [29,30]. NDM (New Delhi metallo-β-lactamase) and VIM (Verona integron-encoded metallo-β-lactamase) are metallo-β-lactamases that bind zinc ions to hydrolyze a broad spectrum of β-lactam antibiotics, including carbapenems. These enzymes are often encoded on mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids or integrons, which facilitate horizontal gene transfer. In contrast, OXA-48 is a class D β-lactamase (oxacillinase) that hydrolyzes carbapenems and penicillins, and is also frequently plasmid-borne, enabling its rapid dissemination [31]. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae have been detected in livestock, companion animals, and wildlife worldwide, although prevalence is generally low. Multiple carbapenemase genes, including NDM, VIM, KPC, OXA, and IMP, have been identified, mainly in Escherichia and Klebsiella species [32]. Global surveillance confirms the widespread dissemination of these carbapenemases beyond Enterobacterales. For instance, in Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates from Egypt, high rates of blaVIM and blaOXA-48 have been reported in carbapenem-resistant strains [33]. Moreover, a study in Iran documented the co-existence of blaNDM, blaVIM, and other carbapenemase genes in multidrug-resistant P. aeruginosa isolates, along with intrinsic resistance mechanisms such as porin loss (OprD) and efflux-pump overexpression [34]. In Acinetobacter baumannii, molecular genotyping of clinical isolates in the Philippines revealed the presence of multiple carbapenemase genes, including blaNDM, blaVIM, and blaOXA-48, often concurrently in the same strain [35].

In our collection, among the 20 carbapenem-resistant C. jejuni isolates, the carbapenemase-encoding genes blaVIM, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48 were detected in 15, 8, and 19 isolates, respectively. For C. coli, 53, 12, and 15 isolates carried the, blaVIM, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48 genes, respectively. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first report documenting the occurrence of carbapenemase-encoding genes in Campylobacter spp. isolates. This finding is alarming for two main reasons: (i) the potential for treatment failure when carbapenems are used as last-resort antibiotics, and (ii) the risk of horizontal transfer of these genes to commensal Gram-negative bacteria within the avian microbiome. In Tunisia, these genes have been frequently reported in clinical Gram-negative bacteria [36,37] but are rarely detected in isolates of animal origin [38], a situation likely related to the absence or scarcity of studies targeting carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria in animals. Most livestock-related research has instead focused on extended-spectrum β-lactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae [39]. A recent study examining ESBL-producing Escherichia coli from calf feces, using cefotaxime-supplemented selective media, reported one ESBL-E. coli isolate co-harboring blaOXA-48 and blaIMP, and another isolate carrying only blaIMP [40].Taken together, the detection of carbapenemase-encoding genes in Campylobacter of avian origin suggests the presence of a hidden reservoir of these genes and indicates that their prevalence in avian Gram-negative bacteria may be underestimated. Therefore, further studies on this issue are urgently needed.

The eleven C. coli isolates collected from the same farm and analyzed by MLST all belonged to the same sequence type, ST13450, which represents a newly identified ST. The clonal spread of MDR C. coli has been widely documented worldwide [41]. MLST analysis positioned the ST13450 isolates within an international genomic context, showing that this ST and its closely related clones are not confined to a specific region. Instead, they exhibit genetic relatedness to isolates reported across Europe, Africa, South America, and Asia. Such broad geographic distribution suggests cross-border dissemination, likely facilitated by international trade and human travel. Recent studies have shown that certain Campylobacter sequence types occur concurrently in both humans and poultry across different continents, reinforcing the hypothesis of globally circulating clones [42,43,44]. Consequently, the integration of ST13450 into this global clonal network highlights its dissemination potential and underscores the urgent need for coordinated worldwide genomic surveillance.

The analysis based on clinical outcome and source of isolation provides additional insight into the epidemiological behavior of ST13450. This sequence type was identified in both patients with gastroenteritis and asymptomatic carriers, demonstrating its capacity to cause disease while also circulating silently within the population. This dual behavior is particularly concerning because it enables hidden transmission pathways that are difficult to detect and control. Similar observations have been reported in Poland and South Korea, where C. jejuni and C. coli sequence types were found in both symptomatic cases and healthy carriers, reinforcing the major role of this genus in foodborne infections [45,46].

Another major finding is the close genetic relatedness between human isolates and those of animal origin (chicken and chicken meat), reinforcing the hypothesis of zoonotic transmission. This observation is consistent with previous reports from Tunisia, which have documented multidrug-resistant Campylobacter strains in poultry farms and carcasses carrying virulence genes and resistance determinants similar to those detected in human isolates [25,41]. The ability of ST13450 to persist and adapt across different hosts and environments highlights its emerging and versatile nature. This underscores the need for strengthened surveillance using a One Health approach that integrates human, animal, and food sectors to effectively monitor and control its spread.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Campylobacter Strain Collection

A total of 287 Campylobacter isolates, comprising 147 C. jejuni and 140 C. coli, were recovered from 590 broiler chicken fecal samples and 143 environmental samples collected from 23 poultry farms in three governorates in northeastern Tunisia (Ariana, Ben Arous, and Nabeul), which together account for 29% of national broiler production, between December 2016 and May 2018. All farms followed similar breeding practices, biosecurity/biosafety protocols, and bird numbers ranging from 2000 to 18,000 hens per house. Samples included cloacal swabs from chickens aged 15–40 days, as well as feces and water from the environment. The farms represented both intensive and semi-extensive production the farm systems, ensuring representative coverage of the Tunisian poultry sector. Chickens had not received antibiotics prior to sampling, and all collections were conducted using standard aseptic procedures.

4.2. Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests

Campylobacter isolates were tested for susceptibility to antimicrobial drugs using the Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion method on Mueller–Hinton agar (Oxoid, Ltd., Basingstoke, UK) as recommended by the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing [47]. All isolates were tested with the following antibiotics (Oxoid Ltd., Hampshire, UK): ampicillin (AMP, 10 μg), amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (AMC, 10/20 μg), gentamicin (GEN, 10 μg), streptomycin (SMN, 10 μg), kanamycin (K, 30 μg), nalidixic acid (NAL, 30 μg), ciprofoxacin (CIP, 5 μg), tetracycline (TET, 30 μg), erythromycin (ERY, 15 μg), azithromycin (AZM, 15 μg), linezolid (LIN, 10 μg), and chloramphenicol (CHL, 30 μg) [47].

4.3. Investigation of Carbapenemase Genes by PCR

Template DNAs for the PCR tests were extracted using the boiling method [26]. All isolates were screened for genes encoding most reported carbapenemases including blaVIM, blaIMP, blaNDM, and blaOXA-48 as previously described [48,49,50,51].

4.4. Statistical Analysis

Quantitative data, including prevalence of phenotypic resistance and resistance genes, were analyzed using the Chi-square test to compare differences between species (C. jejuni vs. C. coli) and between sample types (fecal vs. environmental). For all prevalence estimates, 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, allowing robust assessment of differences in resistance profiles and gene distribution.

Associations between the presence of resistance genes (blaVIM, blaNDM-1, blaOXA-48) and carbapenem resistance phenotypes (ertapenem and/or meropenem) were evaluated using Chi-square (χ2) or Fisher’s exact tests, depending on data distribution. A binary logistic regression model was further applied to determine the independent effect of each gene on the likelihood of carbapenem resistance. For the logistic regression, resistance (1 = resistant to ertapenem and/or meropenem; 0 = susceptible) was used as the dependent variable, and the presence of the carbapenemase genes (blaVIM, blaNDM-1, blaOXA-48) as an independent predictor.

4.5. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST)

Eleven multidrug-resistant (MDR)/carbapenem-resistant C. coli isolates were selected to determine their clonal lineage by MLST. PCR amplicons identifying seven allele loci (aspA, glnA, gltA, glyA, pgm, tkt, and uncA) were obtained for each isolate by using the primers provided in PubMLSTdatabase (https://pubmlst.org/organisms/campylobacter-jejunicoli/primers, accessed on 25 November 2025). After sequencing of PCR products, ST profiles were assigned by submitting the sequences to the PubMLST database using the submission database [20].

4.6. Data Analysis

The heatmap analysis was conducted based on the antimicrobial susceptibility and the presence of genes encoding antibiotic resistance in the collected Campylobacter isolates. The results were visualized as heatmaps (Heatmaps 1 and 2) generated in Python (3.14.1) using the Seaborn (0.13.2) [52], Matplotlib (3.10.7) [53], and Pandas (2.3.3) [54] libraries, where phenotypic resistance values were represented by a color gradient ranging from green (low resistance) to red (high resistance). In parallel, the distribution of antimicrobial resistance genes blaNDM-1, blaIMP, tet(O), cmeB, blaOXA-61, blaOXA-48, and blaVIM, was compared between C. jejuni and C. coli (ST13450) and visualized as a clustered heatmap (Heatmap 2), in which color intensity reflects gene prevalence, and hierarchical clustering was applied to explore genetic similarity patterns.

Phylogenetic relationships of the eleven isolates studied by MLST were reconstructed with the GrapTree tool (version 1.1.0, available within BIGSdb), which generates minimum spanning trees based on allelic distances. In the resulting networks, each node corresponds to a sequence type (ST), node size is proportional to the number of isolates, edges indicate the number of allelic differences, and node colors represent either the country of origin or the clinical/animal source of isolation. This approach enabled the visualization of genetic relatedness among isolates and provided insights into their geographical distribution and epidemiological context.

5. Conclusions

The detection of carbapenemase-producing Campylobacter in poultry and their surrounding environments underscores the critical need for comprehensive surveillance programs. The presence of genes encoding VIM, OXA-48, and NDM enzymes, which are already widespread in clinically important human pathogens such as Enterobacterales, P. aeruginosa, and A. baumannii, raises concern about the potential dissemination of these resistance determinants from food animals to humans. Systematic monitoring of antimicrobial resistance in both animal and environmental samples can identify emerging resistance patterns and high-risk areas, enabling timely and targeted interventions. Promoting antimicrobial stewardship in poultry production, including rational antibiotic use, adoption of alternative therapies, and enhanced biosecurity, can help reduce selective pressures that drive resistance. From a regulatory perspective, these findings highlight the importance of farm-level guidelines, One Health-oriented policies, and risk-based strategies to limit the spread of carbapenem-resistant bacteria through the food chain. Collectively, these measures are essential for safeguarding public health and preserving the efficacy of critically important antibiotics. However, a key limitation of this study is the lack of data on Campylobacter from humans in Tunisia, which prevents direct assessment of zoonotic transmission or the establishment of clear links between poultry and human infections. Future investigations integrating human, animal, and environmental surveillance would be essential to clarify potential transmission pathways and to guide targeted public health interventions. Collectively, these measures are essential for safeguarding public health and preserving the efficacy of critically important antibiotics.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.G. and A.M. methodology, M.G.; S.H., M.A.S.A. and C.H.; validation, M.G. and A.M.; formal analysis, M.G.; investigation, M.G., S.H., M.A.S.A. and C.H.; data curation, M.G.; writing—original draft preparation, M.G.; writing—review and editing, M.G.; visualization, M.G., S.H., M.A.S.A., C.H. and A.M.; supervision, A.M.; project administration, M.G. and A.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was financed by funding provided to the Laboratory of Epidemiology and Veterinary Microbiology (LR16IPT03) by the Tunisian Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was approved by the Biomedical Ethics Committee of the Pasteur Institute of Tunis, with reference number: 2018/12/I/LR16IPT.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The statistical data used to support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Xiong, W.; Sun, Y.; Zeng, Z. Antimicrobial use and antimicrobial resistance in food animals. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2018, 25, 18377–18384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christaki, E.; Marcou, M.; Tofarides, A. Antimicrobial resistance in bacteria: Mechanisms, evolution, and persistence. J. Mol. Evol. 2020, 88, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathers, A.J.; Peirano, G.; Pitout, J.D. The role of epidemic resistance plasmids and international high-risk clones in the spread of multidrug-resistant Enterobacteriaceae. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rozwandowicz, M.; Brouwer, M.S.M.; Fischer, J.; Wagenaar, J.A.; Gonzalez-Zorn, B.; Guerra, B.; Mevius, D.J.; Hordijk, J. Plasmids carrying antimicrobial resistance genes in Enterobacteriaceae. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2018, 73, 1121–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassi, M.S.; Badi, S.; Lengliz, S.; Mansouri, R.; Salah, H.; Hynds, P. Hiding in plain sight: Wildlife as a neglected reservoir and pathway for the spread of antimicrobial resistance: A narrative review. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2022, 98, fiac045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woolhouse, M.; Ward, M.; van Bunnik, B.; Farrar, J. Antimicrobial resistance in humans, livestock and the wider environment. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci. 2015, 370, 20140083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vidovic, N.; Vidovic, S. Antimicrobial resistance and food animals: Influence of livestock environment on the emergence and dissemination of antimicrobial resistance. Antibiotics 2020, 9, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Igwaran, A.; Okoh, A.I. Human Campylobacteriosis: A public health concern of global importance. Heliyon 2019, 5, e0281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaakoush, N.O.; Castaño-Rodríguez, N.; Mitchell, H.M.; Man, S.M. Global epidemiology of Campylobacter infection. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2015, 28, 687–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aleksić, E.; Miljković-Selimović, B.; Tambur, Z.; Aleksić, N.; Biočanin, V.; Avramov, S. Resistance to antibiotics in thermophilic Campylobacters. Front. Med. 2021, 8, 763434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bukari, Z.; Emmanuel, T.; Woodward, J.; Ferguson, R.; Ezughara, M.; Darga, N.; Lopes, B.S. The global challenge of Campylobacter: Antimicrobial resistance and emerging intervention strategies. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2025, 10, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakanen, A.J.; Lehtopolku, M.; Siitonen, A.; Huovinen, P.; Kotilainen, P. Multidrug resistance in Campylobacter jejuni strains collected from Finnish patients during 1995–2000. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2003, 52, 1035–1039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagiya, H.; Kimura, K.; Nishi, I.; Yoshida, H.; Yamamoto, N.; Akeda, Y.; Tomono, K. Emergence of carbapenem non-susceptible Campylobacter coli after long-term treatment against recurrent bacteremia in a patient with X-linked agammaglobulinemia. Intern. Med. 2018, 57, 2077–2080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuo, R.; Younes, R.L.; Ward, K.; Yang, S. Carbapenem resistant Campylobacter jejuni bacteremia in a Bruton’s X-linked agammaglobulinemia patient. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2024, 43, 2459–2463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonilla-Moreno, M.; Torrecillas, M.; Laporte-Amargos, J.; Gonzalez-Diaz, A.; Mussetti, A.; Tubau, F.; Gudiol, C.; Dominguez, M.A.; Marti, S.; Rodriguez-Sevilla, G.; et al. Development of meropenem resistance in a multidrug-resistant Campylobacter coli strain causing recurrent bacteremia in a hematological malignancy patient. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2023, 67, e0027223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maurille, C.; Guérin, F.; Jehanne, Q.; Audemard-Verger, A.; Isnard, C.; Verdon, R.; Lehours, P.; Bonnet, R.; Giard, J.C.; Le Hello, S.; et al. Occurrence of in vivo carbapenem-resistant Campylobacter coli mediated by porA point mutation and overexpression of blaOXA-489 under meropenem treatment. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2024, 30, 1478–1480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chibwe, M.; Odume, O.N.; Nnadozie, C.F. A review of antibiotic resistance among Campylobacter species in human, animal, and water sources in South Africa: A One Health Approach. J. Water Health 2023, 21, 9–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Food Safety Authority (EFSA); European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). The European Union summary report on antimicrobial resistance in zoonotic and indicator bacteria from humans, animals and food in 2021–2022. EFSA J. 2024, 22, e8583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Yang, D.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Feßler, A.T.; Shen, Z.; Shen, J.; Schwarz, S.; Wang, Y. Detection of the enterococcal oxazolidinone/phenicol resistance gene optrA in Campylobacter coli. Vet. Microbiol. 2020, 246, 108731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes, A.; Oleastro, M.; Alves, F.; Liassine, N.; Lowe, D.M.; Benejat, L.; Ducounau, A.; Jehanne, Q.; Borges, V.; Gomes, J.P.; et al. Recurrent Campylobacter jejuni infections with in vivo selection of resistance to macrolides and carbapenems: Molecular characterization of resistance determinants. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e0107023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gharbi, M.; Tiss, R.; Hamdi, C.; Hamrouni, S.; Maaroufi, A. Occurrence of florfenicol and linezolid resistance and emergence of optrA gene in Campylobacter coli isolates from Tunisian avian farms. Int. J. Microbiol. 2024, 2024, 1694745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Yang, J.; Abbas, M.; Yang, Q.; Li, Q.; Liu, M.; Zhu, D.; Wang, M.; Tian, B.; Cheng, A. Threats across boundaries: The spread of ESBL-positive Enterobacteriaceae bacteria and its challenge to the “one health” concept. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1496716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gržinić, G.; Piotrowicz-Cieślak, A.; Klimkowicz-Pawlas, A.; Górny, R.L.; Ławniczek-Wałczyk, A.; Piechowicz, L.; Olkowska, E.; Potrykus, M.; Tankiewicz, M.; Krupka, M.; et al. Intensive poultry farming: A review of the impact on the environment and human health. Sci Total Environ. 2023, 858 Pt 3, 160014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Natsos, G.; Mouttotou, N.K.; Magiorkinis, E.; Ioannidis, A.; Rodi-Burriel, A.; Chatzipanagiotou, S.; Koutoulis, K.C. Prevalence of and risk factors for Campylobacter spp. colonization of broiler chicken flocks in Greece. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2020, 17, 679–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO. Prioritization of Pathogens to Guide Discovery, Research and Development of New Antibiotics for Drug-Resistant Bacterial Infections, Including Tuberculosis. 4 September 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/WHO-EMP-IAU-2017.12 (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Gharbi, M.; Béjaoui, A.; Ben Hamda, C.; Ghedira, K.; Ghram, A.; Maaroufi, A. Distribution of virulence and antibiotic resistance genes in Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli isolated from broiler chickens in Tunisia. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 2022, 55, 1273–1282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iovine, N.M. Resistance mechanisms in Campylobacter jejuni. Virulence 2016, 4, 230–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manzanares-Pedrosa, A.; Correa-Fiz, F.; Andrade, F.; Ayats, T.; Nofrarías, M.; Cerdà-Cuéllar, M. Phenotypic and whole genome-based characterization of antibiotic resistance of Campylobacter jejuni isolates from chicken livers. Poult. Sci. 2025, 104, 105302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jean, S.S.; Harnod, D.; Hsueh, P.R. Global threat of carbapenem-resistant Gram-negative bacteria. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 823684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peirano, G.; Pitout, J.D.D. Rapidly spreading Enterobacterales with OXA-48-like carbapenemases. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2025, 63, e0151524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatzisarantinos, T.; Mansour, E.; Du, J.J.; Fares, M.; Hibbs, D.E.; Groundwater, P.W. Structural insights into the activity of carbapenemases: Understanding the mechanism of action of current inhibitors and informing the design of new carbapenem adjuvants. RSC Med. Chem. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Köck, R.; Daniels-Haardt, I.; Becker, K.; Mellmann, A.; Friedrich, A.W.; Mevius, D.; Schwarz, S.; Jurke, A. Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in wildlife, food-producing, and companion animals: A systematic review. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2018, 24, 1241–1250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdelraheem, W.M.; Ismail, D.E.; Hammad, S.S. Prevalence of blaOXA-48 and other carbapenemase encoding genes among carbapenem-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clinical isolates in Egypt. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soltani, B.; Ahmadrajabi, R.; Kalantar-Neyestanaki, D. Critical resistance to carbapenem and aminoglycosides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: Spread of blaNDM/16S methylase armA harboring isolates with intrinsic resistance mechanisms in Kerman, Iran. BMC Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 1188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carascal, M.B.; Destura, R.V.; Rivera, W.L. Molecular genotyping reveals multiple carbapenemase genes and unique blaOXA-51-like (oxaAb) alleles among clinically isolated Acinetobacter baumannii from a Philippine tertiary hospital. Trop. Med. Health 2024, 52, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dziri, O.; Dziri, R.; Ali El Salabi, A.; Chouchani, C. Carbapenemase producing Gram-negative bacteria in Tunisia: History of thirteen years of challenge. Infect. Drug Resist. 2020, 13, 4177–4191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaidane, N.; Tilouche, L.; Oueslati, S.; Girlich, D.; Azaiez, S.; Jacquemin, A.; Dortet, L.; Naija, W.; Trabelsi, A.; Naas, T.; et al. Clonal dissemination of NDM-producing Proteus mirabilis in a teaching hospital in Sousse, Tunisia. Pathogens 2025, 14, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lengliz, S.; Benlabidi, S.; Raddaoui, A.; Cheriet, S.; Ben Chehida, N.; Najar, T.; Abbassi, M.S. High occurrence of carbapenem-resistant Escherichia coli isolates from healthy rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus): First report of blaIMI and blaVIM type genes from livestock in Tunisia. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 73, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassen, B.; Saloua, B.; Abbassi, M.S.; Ruiz-Ripa, L.; Mama, O.M.; Hassen, A.; Hammami, S.; Torres, C. mcr-1 encoding colistin resistance in CTX-M-1/CTX-M-15-producing Escherichia coli isolates of bovine and caprine origins in Tunisia. First report of CTX-M-15-ST394/D E. coli from goats. Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2019, 67, 101366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ben Haj Yahia, A.; Tayh, G.; Landolsi, S.; Maamar, E.; Galai, N.; Landoulsi, Z.; Messadi, L. First report of OXA-48 and IMP genes among extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli isolates from diarrheic calves in Tunisia. Microb. Drug Resist. 2023, 29, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montero, L.; Medina-Santana, J.L.; Ishida, M.; Sauders, B.; Trueba, G.; Vinueza-Burgos, C. Transmission of dominant strains of Campylobacter jejuni and Campylobacter coli between farms and retail stores in Ecuador: Genetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0308030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, M.; Tiss, R.; Chaouch, M.; Hamrouni, S.; Maaroufi, A. Emergence of Plasmid-Mediated Quinolone Resistance (PMQR) genes in Campylobacter coli in Tunisia and detection of new Sequence Type ST13450. Antibiotics 2024, 13, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuang, S.; Wang, Z.; Hu, X.; Dong, Z.; Wang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Li, Z.; Shi, D.; Li, S.; Zhou, Z. Prevalence and genetic characteristics of Campylobacter jejuni from laying-hens in Hubei Province, China. BMC Vet Res. 2025, 21, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, M.; Wang, X.; Zheng, L.; Zhu, Y. Genomic analysis and antimicrobial resistance in human- and poultry-derived Campylobacter jejuni isolates from Hangzhou, China. Front. Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1599555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieczorek, K.; Wołkowicz, T.; Osek, J. MLST-based genetic relatedness of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from chickens and humans in Poland. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0226238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, J.; Lee, J.Y.; Moon, J.S.; Kang, M.S.; Kang, S.I.; Lee, O.M.; Lee, S.H.; Kwon, Y.K.; Chae, M.; Cho, S. Virulence genes, antimicrobial resistance, and genotypes of Campylobacter jejuni isolated from chicken slaughterhouses in South Korea. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2023, 20, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The European Committeeon Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint Tables for Interpretation of MICs and Zone Diameters. Version 5.0. 2015. Available online: http://www.eucast.org (accessed on 25 November 2025).

- Ellington, M.J.; Kistler, J.; Livermore, D.M.; Woodford, N. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding acquired metallo-beta-lactamases. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2007, 59, 321–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poirel, L.; Dortet, L.; Bernabeu, S.; Nordmann, P. Genetic features of blaNDM-1-positive Enterobacteriaceae. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2011, 55, 5403–5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poirel, L.; Héritier, C.; Tolün, V.; Nordmann, P. Emergence of oxacillinase-mediated resistance to imipenem in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob. Agents. Chemother. 2004, 48, 15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.S.; Kim, K.; Huh, J.Y.; Jung, B.; Kang, M.S.; Hong, S.G. Multiplex PCR for rapid detection of genes encoding class A carbapenemases. Ann. Lab. Med. 2012, 32, 359–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waskom, M.L. Seaborn: Statistical data visualization. J. Open Source Softw. 2021, 6, 3021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D graphics environment. Comput. Sci. Eng. 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKinney, W. Data Structures for Statistical Computing in Python. In Proceedings of the 9th Python in Science Conference, Austin, TX, USA, 28–30 June 2010; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).