Deep Learning-Assisted Cactus-Inspired Osmosis-Enrichment Patch for Biosafety-Isolative Wearable Sweat Metabolism Assessment

Abstract

1. Background and Originality Content

2. Results and Discussion

2.1. Patterned Janus Membranes for In Situ Sweat Collection and Detection and DL-Assisted Fluorescence Sensor Chips for Sweat Analysis

2.2. Janus Membrane Structure and Morphology Characterization

2.3. Spontaneous Droplet Sampling

2.4. The Chemical Sensing Mechanism of Sweat Biomarkers

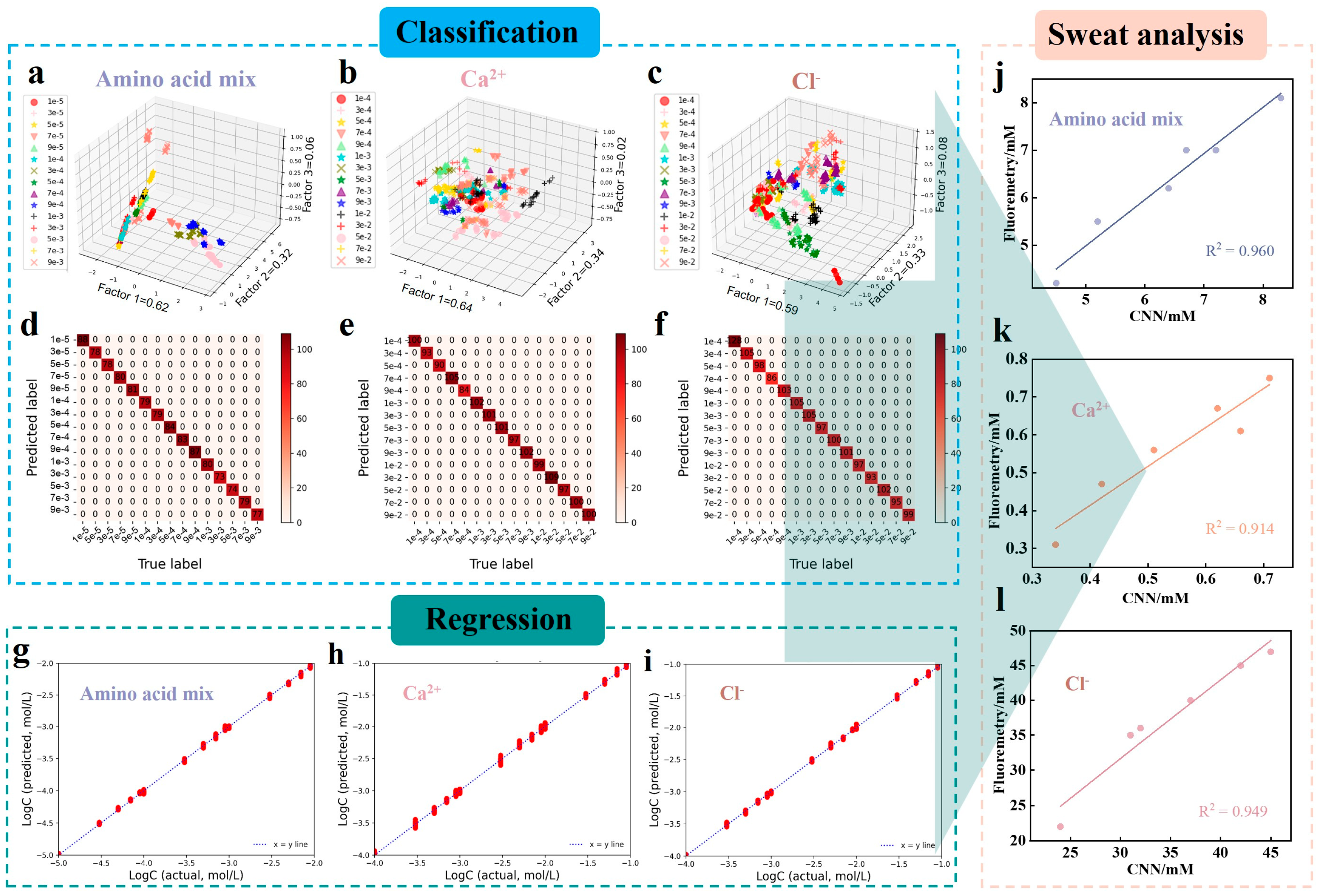

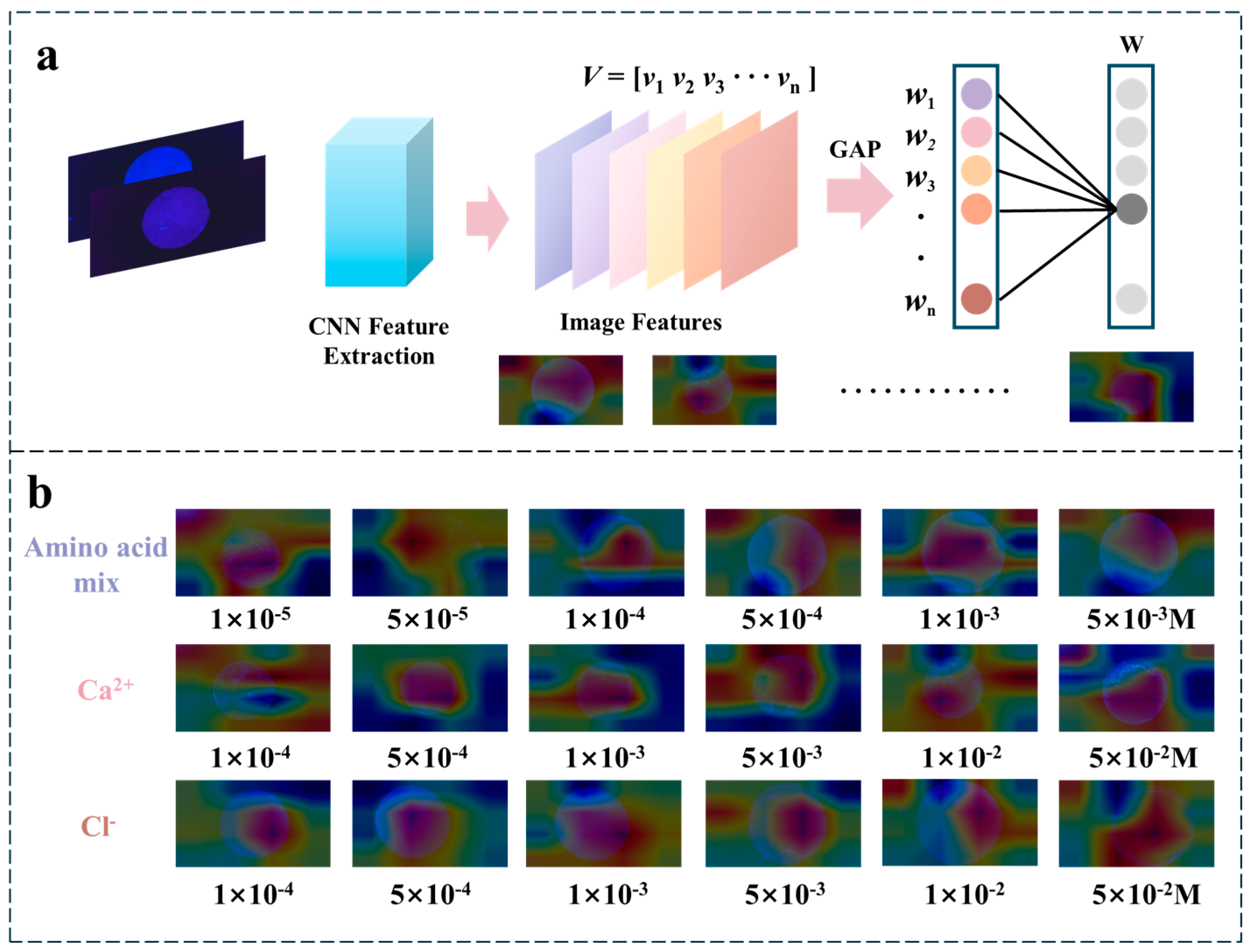

2.5. DL-Assisted Detection of Sweat Biomarkers Using Fluorescence Chips

2.6. The Interpretability of CNN for Fluorescent Patch

3. Conclusions

4. Experimental

4.1. Fabrication of the Patterned Janus Membrane

4.2. Preparation of Programmable Fluorescent Hydrogel Chips

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davis, N.; Heikenfeld, J.; Milla, C.; Javey, A. The Challenges and Promise of Sweat Sensing. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 860–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arwani, R.T.; Tan, S.C.L.; Sundarapandi, A.; Goh, W.P.; Liu, Y.; Leong, F.Y.; Yang, W.F.; Zheng, X.T.; Yu, Y.; Jiang, C.; et al. Stretchable Ionic–Electronic Bilayer Hydrogel Electronics Enable in Situ Detection of Solid-State Epidermal Biomarkers. Nat. Mater. 2024, 23, 1115–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, Y.; De la Paz, E.; Paul, A.; Mahato, K.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Tostado, N.; Lee, M.; Hota, G.; Lin, M.; Uppal, A.; et al. In-Ear Integrated Sensor Array for the Continuous Monitoring of Brain Activity and of Lactate in Sweat. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 1307–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, C.; Wang, M.; Min, J.; Tay, R.Y.; Lukas, H.; Sempionatto, J.R.; Li, J.; Xu, C.; Gao, W. A Wearable Aptamer Nanobiosensor for Non-Invasive Female Hormone Monitoring. Nat. Nanotechnol. 2024, 19, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Min, J.; Tu, J.; Xu, C.; Lukas, H.; Shin, S.; Yang, Y.; Solomon, S.A.; Mukasa, D.; Gao, W. Skin-Interfaced Wearable Sweat Sensors for Precision Medicine. Chem. Rev. 2023, 123, 5049–5138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, S.H.; Cho, S.; Lv, Z.; Sekine, Y.; Liu, S.; Zhou, M.; Nuxoll, R.F.; Kanatzidis, E.E.; Ghaffari, R.; Kim, D.; et al. Soft, Wearable, Microfluidic System for Fluorometric Analysis of Loss of Amino Acids through Eccrine Sweat. Lab Chip 2025, 25, 1647–1655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyein, H.Y.Y.; Gao, W.; Shahpar, Z.; Emaminejad, S.; Challa, S.; Chen, K.; Fahad, H.M.; Tai, L.-C.; Ota, H.; Davis, R.W.; et al. A Wearable Electrochemical Platform for Noninvasive Simultaneous Monitoring of Ca2+ and pH. ACS Nano 2016, 10, 7216–7224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bortolotti, C.; Ottomaniello, A.; Parlanti, P.; Mattoli, V.; Natali, D.; Aliverti, A.; Kyndiah, A.; Caironi, M. Sensing of Chloride Ions in Sweat by Means of Printed Extended-Gate Organic Electrochemical Transistors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2025, e11675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K.; Zhang, J.; Wang, F.; Kong, D. Stretchable and Superwettable Colorimetric Sensing Patch for Epidermal Collection and Analysis of Sweat. ACS Sens. 2021, 6, 2261–2269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Fang, X.; Li, H.; Zha, L.; Guo, J.; Zhang, X. Sweat Sensor Based on Wearable Janus Textiles for Sweat Collection and Microstructured Optical Fiber for Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Analysis. ACS Sens. 2023, 8, 4774–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Huang, J.; Liu, Y.; Peng, J.; Chen, S.; Song, K.; Ouyang, X.; Cheng, H.; Wang, X. Skin-Interfaced Microfluidic Devices with One-Opening Chambers and Hydrophobic Valves for Sweat Collection and Analysis. Lab Chip 2020, 20, 2635–2645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Yang, P.; Xie, X.; Cao, X.; Deng, Y.; Ding, X.; Zhang, Z. Bio-Inspired Hierarchical Wearable Patch for Fast Sweat Collection. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2024, 260, 116430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, J.; Huang, Y.; Liu, M.; Xie, N.; Shi, J.; Fan, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Kang, W. Construction of Electrospinning Janus Nanofiber Membranes for Efficient Solar-Driven Membrane Distillation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 305, 122348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, X.; Bai, L.; Li, J.; Huang, L.; Sun, H.; Gao, X. Robust Preparation of Flexibly Super-Hydrophobic Carbon Fiber Membrane by Electrospinning for Efficient Oil-Water Separation in Harsh Environments. Carbon 2021, 182, 11–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Gu, J.; Liu, Y.; Yang, L.; Wang, L.; Yu, J.; Qin, X. Reconfiguration and Self-Healing Integrated Janus Electrospinning Nanofiber Membranes for Durable Seawater Desalination. Nano Res. 2023, 16, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Dong, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Xue, W.; Li, F.; Hou, Z.; Li, X.; Zhang, K.; Ke, Y.; Fang, T.; et al. A patterned Janus textile patch for monitoring multiple biomarkers. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2025, 440, 137954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, X.; Wu, H.; Wang, C.; Zhang, X.; Wei, C.; Xu, Z.; Chen, D.; Huang, X. Hybrid Janus Membrane with Dual-Asymmetry Integration of Wettability and Conductivity for Ultra-Low-Volume Sweat Sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 9644–9654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, Q.; Yuan, R.; Zhan, H.; Jin, J.; Qiao, X. Janus Membrane-Based Wearable Dual-Channel SERS Sensor for Sweat Collection and Monitoring of Lactic Acid and pH Levels. Anal. Chem. 2025, 97, 6083–6091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Wei, G.; Liu, A.; Huo, F.; Zhang, Z. A Review of Sampling, Energy Supply and Intelligent Monitoring for Long-Term Sweat Sensors. Npj Flex. Electron. 2022, 6, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xi, P.; He, X.; Fan, C.; Zhu, Q.; Li, Z.; Yang, Y.; Du, X.; Xu, T. Smart Janus fabrics for one-way sweat sampling and skin-friendly colorimetric detection. Talanta 2023, 259, 124507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Son, J.; Bae, G.Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, G.; Kim, S.W.; Kim, D.; Chung, S.; Cho, K. Cactus-Spine-Inspired Sweat-Collecting Patch for Fast and Continuous Monitoring of Sweat. Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2102740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zhu, H.; He, S.; Guo, Z. Bioinspired Janus Mesh with Gradient Wettability for High-Efficiency Fog Harvesting via Synergistic Capillary Condensation and Directional Droplet Transport. Small Struct. 2025, 6, 2500436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, J.; Liu, Y.; Su, L.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, L.; Zhang, X. Microfluidic Chip-Based Wearable Colorimetric Sensor for Simple and Facile Detection of Sweat Glucose. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 14803–14807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Y.; Duan, W.; Jin, Y.; Wo, F.; Xi, F.; Wu, J. Ratiometric Fluorescent Nanohybrid for Noninvasive and Visual Monitoring of Sweat Glucose. ACS Sens. 2020, 5, 2096–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ardalan, S.; Hosseinifard, M.; Vosough, M.; Golmohammadi, H. Towards Smart Personalized Perspiration Analysis: An IoT-Integrated Cellulose-Based Microfluidic Wearable Patch for Smartphone Fluorimetric Multi-Sensing of Sweat Biomarkers. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2020, 168, 112450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Shin, J.; Park, J.-H.; Lee, H.; Kim, D.-H.; Liu, H. Engineering Materials for Electrochemical Sweat Sensing. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2008130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.; Li, J.; Zhou, J.; Luo, Q.; Wu, W.; Mao, Z.; Ma, W. Screen-Printed Carbon Black/Recycled Sericin @Fabrics for Wearable Sensors to Monitor Sweat Loss. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2022, 14, 11813–11819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Liu, M.; Yang, X.; Lu, Q.; Xiong, Z.; Li, L.; Zheng, H.; Feng, S.; Zhang, T. An Unconventional Vertical Fluidic-Controlled Wearable Platform for Synchronously Detecting Sweat Rate and Electrolyte Concentration. Brosens. Bioelectron. 2022, 210, 114351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.; Xu, G.; Zhang, X.; Gong, H.; Jiang, L.; Sun, G.; Li, Y.; Liu, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, S.; et al. Dual-Functional Ultrathin Wearable 3D Particle-in-Cavity SF-AAO-Au SERS Sensors for Effective Sweat Glucose and Lab-on-Glove Pesticide Detection. Sens. Actuators B Chem. 2022, 359, 131512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, M.; Skinner, W.H.; Robert, C.; Campbell, C.J.; Rossi, R.M.; Koutsos, V.; Radacsi, N. Fabrication of a Wearable Flexible Sweat pH Sensor Based on SERS-Active Au/TPU Electrospun Nanofibers. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2021, 13, 51504–51518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, K.; Yang, K.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, Z.; Qian, Z.; Li, N.; Li, L.; Jiang, G.; Wang, T.; Zong, S.; et al. Wearable SERS Sensor Based on Omnidirectional Plasmonic Nanovoids Array with Ultra-High Sensitivity and Stability. Small 2022, 18, 2201508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Qin, G.; Luo, F.; Wang, L.; Zhao, R.; Li, N.; Yuan, J.; Fang, X. Automated Stoichiometry Analysis of Single-Molecule Fluorescence Imaging Traces via Deep Learning. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141, 6976–6985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, S.R.; Bung, N.; Vangala, S.R.; Srinivasan, R.; Bulusu, G.; Roy, A. De Novo Structure-Based Drug Design Using Deep Learning. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2021, 62, 5100–5109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, X.; Wang, Y.; Byrne, R.; Schneider, G.; Yang, S. Concepts of Artificial Intelligence for Computer-Assisted Drug Discovery. Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 10520–10594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, L.; Lyu, A.; Hao, H.; Shen, W.; Cui, H. Deep Learning-Assisted Three-Dimensional Fluorescence Difference Spectroscopy for Identification and Semiquantification of Illicit Drugs in Biofluids. Anal. Chem. 2019, 91, 9343–9347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayres, L.B.; Gomez, F.J.V.; Linton, J.R.; Silva, M.F.; Garcia, C.D. Taking the Leap between Analytical Chemistry and Artificial Intelligence: A Tutorial Review. Anal. Chim. Acta 2021, 1161, 338403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, B.; Khosla, A.; Lapedriza, A.; Oliva, A.; Torralba, A. Learning Deep Features for Discriminative Localization. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 2921–2929. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Q.; Ye, M.; Wei, M.; Lian, G.; Li, Y. Deep Convolutional Neural Network Based Closed-Loop SOC Estimation for Lithium-Ion Batteries in Hierarchical Scenarios. Energy 2023, 263, 125718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.-T.; Cheah, C.C.; Toh, K.-A. An Analytic Layer-Wise Deep Learning Framework with Applications to Robotics. Automatica 2022, 135, 110007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.; Liang, Y.; Ye, Y.; Liu, Z.; Meng, J.; Li, F. Explainable Deep Learning-Assisted Fluorescence Discrimination for Aminoglycoside Antibiotic Identification. Anal. Chem. 2022, 94, 829–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, Z.; Tang, Y.; Wang, S.; Meng, J.; Li, F. Explainable Deep Learning-Assisted Self-Calibrating Colorimetric Patches for In Situ Sweat Analysis. Anal. Chem. 2024, 96, 1205–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Yang, T.; Yan, Y.; Tang, Y.; Meng, J.; Li, F. Self-calibrating colorimetric sensor assisted deep learning strategy for efficient and precise Fe (II) detection. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 51, 104389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yan, Y.; Xiao, T.; Lin, M.; Yue, W.; Qu, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, J.; Pan, D.; Li, F.; et al. Deep Learning-Assisted Cactus-Inspired Osmosis-Enrichment Patch for Biosafety-Isolative Wearable Sweat Metabolism Assessment. Biosensors 2025, 15, 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120790

Yan Y, Xiao T, Lin M, Yue W, Qu J, Chen Y, Zhang Z, Meng J, Pan D, Li F, et al. Deep Learning-Assisted Cactus-Inspired Osmosis-Enrichment Patch for Biosafety-Isolative Wearable Sweat Metabolism Assessment. Biosensors. 2025; 15(12):790. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120790

Chicago/Turabian StyleYan, Yuwen, Ting Xiao, Miaorong Lin, Wenyan Yue, Jihan Qu, Yonghuan Chen, Zhihao Zhang, Jianxin Meng, Dong Pan, Fengyu Li, and et al. 2025. "Deep Learning-Assisted Cactus-Inspired Osmosis-Enrichment Patch for Biosafety-Isolative Wearable Sweat Metabolism Assessment" Biosensors 15, no. 12: 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120790

APA StyleYan, Y., Xiao, T., Lin, M., Yue, W., Qu, J., Chen, Y., Zhang, Z., Meng, J., Pan, D., Li, F., & Su, B. (2025). Deep Learning-Assisted Cactus-Inspired Osmosis-Enrichment Patch for Biosafety-Isolative Wearable Sweat Metabolism Assessment. Biosensors, 15(12), 790. https://doi.org/10.3390/bios15120790