Pseudomonas syringae Population Recently Isolated from Winter Wheat in Serbia

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Symptoms, Sample Collections, and Pathogen Isolation

2.2. Phenotypic Characterization

2.3. Genetic Identification

2.3.1. Detection of Genes syrB (Syringomycin Synthesis) and syrD (Syringomycin Secretion)

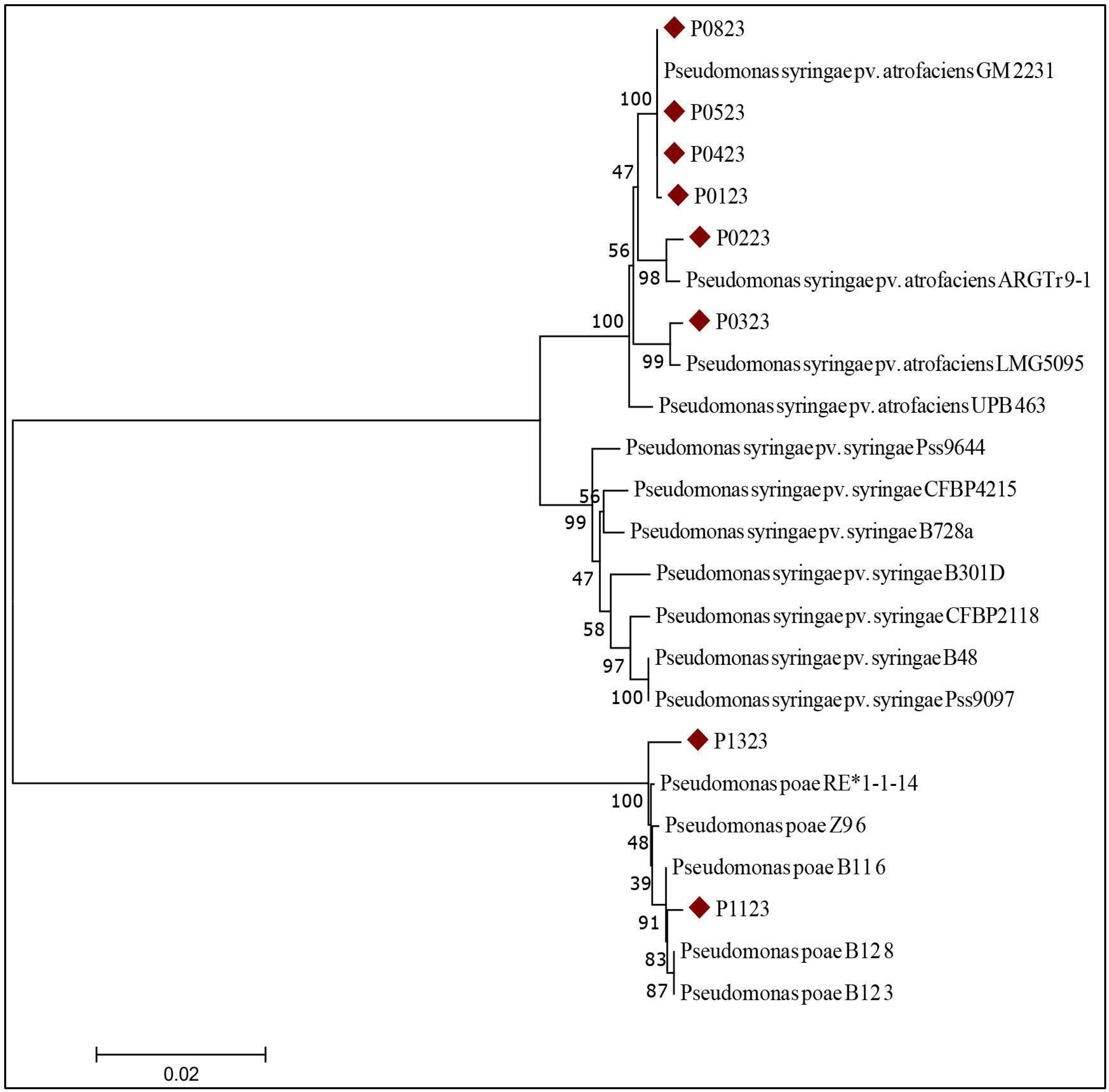

2.3.2. Multilocus Sequence Analysis (MLSA)

3. Results

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pandey, M.; Shrestha, J.; Subedi, S.; Shah, K.K. Role of Nutrients in Wheat: A Review. Trop. Agrobiodivers. 2020, 1, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shewry, P.R.; Hey, S.J. The Contribution of Wheat to Human Diet and Health. Food Energy Secur. 2015, 4, 178–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- FAOSTAT. FAO Statistics Database. 2023. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Mehmood, A.; Amin, A.; Ullah, S.; Fayyaz, M.; Fateh, F.S. A Comprehensive Review of Significant Bacterial Diseases Affecting Wheat. Pak. J. Phytopathol. 2023, 35, 191–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraite, H.; Bragard, C.; Duveiller, E. The Status of Resistance to Bacterial Diseases of Wheat. In Wheat Production in Stressed Environments: Proceedings of the 7th International Wheat Conference, Mar del Plata, Argentina, 27 November–2 December 2005; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 37–49. [Google Scholar]

- Kelpšienė, J.; Šneideris, D.; Burokienė, D.; Supronienė, S. The Presence of Pathogenic Bacteria Pseudomonas syringae in Cereals in Lithuania. Žemdirbystė 2021, 108, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambong, J.T. Bacterial Pathogens of Wheat: Symptoms, Distribution, Identification, and Taxonomy. In Wheat—Recent Advances; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Liu, L.; Wang, Y.; Yan, J.; Shah, S.M.A.; Chen, G. Comprehensive Genomic Insights into Unique TALEs of a Xanthomonas translucens pv. undulosa Strain from China. Plant Pathol. 2025, 74, 2455–2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abo Bakr, A.; Khatib, F.; Kassem, M.; Kumari, S.G.; Husien, N.; Asaad, N. Investigation of the Spread of Bacterial Wheat Leaf Blight Caused by Pathotypes of Pseudomonas syringaein Some Wheat Growing Areas in Syria. Arab. J. Plant Prot. 2024, 42, 291–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matveeva, I.E.V.; Pekhtereva, E.S.; Polityko, V.A.; Ignatov, A.N.; Nikolaeva, E.V.; Schaad, N.W. Distribution and Virulence of Pseudomonas syringae pv. atrofaciens, Causal Agent of Basal Glume Rot, in Russia. In Pseudomonas syringae and Related Pathogens; Iacobellis, N.S., Collmer, A., Hutcheson, S.W., Mansfield, J.W., Morris, C.E., Murillo, J., Schaad, N.W., Stead, D.E., Surico, G., Ullrich, M.S., et al., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2003; pp. 97–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slovareva, O.Y. Production, Export and Import of Cereals and Compilation of a List of Phytopathogenic Bacteria Associated with Them. Agrar. Bull. N. Cauc. 2023, 3, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tambong, J.T.; Xu, R.; Fleitas, M.C.; Kutcher, R. Taxonogenomic Analysis of the Xanthomonas translucens Complex Leads to the Descriptions of Xanthomonas cerealis sp. nov. and Xanthomonas graminis sp. nov. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2024, 74, 006523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPO. EPPO Global Database. 2022. Available online: https://gd.eppo.int (accessed on 23 September 2025).

- Fumero, M.V.; Garis, S.B.; Alberione, E.; Jofré, E.; Vanzetti, L.S. Genomic Analysis Identifies Five Pathogenic Bacterial Species in Argentinian Wheat. Trop. Plant Pathol. 2024, 49, 864–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockus, W.W.; Bowden, R.L.; Hunger, R.M.; Murray, T.D.; Smiley, R.W. Compendium of Wheat Diseases and Pests, 3rd ed.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2010; p. viii-171. [Google Scholar]

- Dobrovol’skaya, T.G.; Khusnetdinova, K.A.; Manucharova, N.A.; Golovchenko, A.V. Structure of Epiphytic Bacterial Communities of Weeds. Microbiology 2017, 86, 257–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butsenko, L.; Pasichnyk, L.; Kolomiiets, Y.; Kalinichenko, A.; Suszanowicz, D.; Sporek, M.; Patyka, V. Characteristic of Pseudomonas syringae pv. atrofaciens Isolated from Weeds of Wheat Field. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knežević, T.; Koprivica, M.; Jevtić, R.; Obradović, A. Bacterial Diseases of Small Grains. Plant Dr. 2016, 44, 478–486. [Google Scholar]

- Schaad, N.W.; Jones, J.B.; Chun, W. Laboratory Guide for Identification of Plant Pathogenic Bacteria, 3rd ed.; American Phytopathological Society: St. Paul, MN, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Republic Hydrometeorological Service of Serbia. 2022–2023. Available online: https://www.hidmet.gov.rs (accessed on 25 September 2025).

- Klement, Z.; Mavridis, A.; Rudolph, K.; Vidaver, A.; Perombelon, M.C.M.; Moore, L. Inoculation of Plant Tissues. In Methods in Phytobacteriology; Klement, Z., Rudolph, K., Sands, D.C., Eds.; Academia Kiado: Budapest, Hungary, 1990; pp. 95–124. [Google Scholar]

- Duveiller, E.; Fucikovsky, L.; Rudolph, K. (Eds.) The Bacterial Diseases of Wheat: Concepts and Methods of Disease Management; CIMMYT: Mexico D.F., Mexico, 1997; 78p. [Google Scholar]

- Iličić, R.; Balaž, J.; Stojšin, V.; Bagi, F.; Pivić, R.; Stanojković-Sebić, A.; Jošić, D. Molecular Characterization of Pseudomonas syringae pvs. from Different Host Plants by Repetitive Sequence-Based PCR and Multiplex-PCR. Žemdirbystė 2016, 103, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarkar, S.F.; Guttman, D.S. Evolution of the Core Genome of Pseudomonas syringae, a Highly Clonal, Endemic Plant Pathogen. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 1999–2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, M.S.; Morgan, R.L.; Sarkar, S.F.; Wang, P.W.; Guttman, D.S. Phylogenetic Characterization of Virulence and Resistance Phenotypes of Pseudomonas syringae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005, 71, 5182–5191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popović Milovanović, T.; Kosovac, A.; Jelušić, A.; Scortichini, M.; Trkulja, N.; Stanković, S.; Iličić, R. Genetic Diversity and Virulence Traits of Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae Isolated from Various Hosts in Serbia. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2025, 186, 334–348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimura, M. A Simple Method for Estimating Evolutionary Rates of Base Substitutions through Comparative Studies of Nucleotide Sequences. J. Mol. Evol. 1980, 16, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Botin, A.J.; Mendoza-Onofre, L.E.; Silva-Rojas, H.V.; Valadez-Moctezuma, E.; Cordova-Tellez, L.; Villaseñor-Mir, H.E. Effect of Pseudomonas syringae subsp. syringae on Yield and Biomass Distribution in Wheat. Span. J. Agric. Res. 2011, 9, 1287–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valencia-Botín, A.J.; Cisneros-López, M.E. A Review of the Studies and Interactions of Pseudomonas syringae Pathovars on Wheat. Int. J. Agron. 2012, 2012, 692350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirano, S.S.; Upper, C.D. Bacteria in the Leaf Ecosystem with Emphasis on Pseudomonas syringae—A Pathogen, Ice Nucleus, and Epiphyte. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2000, 64, 624–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iličić, R.; Balaž, J.; Ognjanov, V.; Popović, T. Epidemiology Studies of Pseudomonas syringae Pathovars Associated with Bacterial Canker on the Sweet Cherry in Serbia. Plant Prot. Sci. 2021, 57, 196–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strain | Host | Country | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. atrofaciens | |||

| GM 2231 | wheat | - | CP166624 |

| LMG5095 | wheat | New Zealand | CP028490 |

| UPB 463 | wheat | Canada | CP162520 |

| ARGTr 9-1 | wheat | Argentina | CP147770 |

| Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae | |||

| Pss9644 | sweet cherry | United Kingdom | CP066263 |

| B48 | peach | USA | CP125300 |

| CFBP4215 | - | France | LT962480 |

| CFBP2118 | - | France | LT962481 |

| B728a | - | - | CP000075 |

| B301D | pear | United Kingdom | CP005969 |

| Pseudomonas poae | |||

| B11_6 | wheat | Denmark | CP142194 |

| B12_8 | wheat | Denmark | CP142188 |

| RE*1-1-14 | endorhiza sugar beet | - | CP004045 |

| B12_3 | Wheat | Denmark | CP142191 |

| Z9_6 | Wheat | Denmark | CP142176 |

| Isolate | Species and Percent Identity | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| gapA | gltA | gyrB | rpoD | |

| P0123 | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens UPB 463, ARGTr 9-1/ P. syringae GAB0016, MUP17/ P. syringae pv. syringae IO 106 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens GM 2231/ P. syringae CC457, CC440, Psy33, GAB0016 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens GM 2231/P. syringae pv. syringae B37/09, IO109 (99.83%) | P. syringae pv. syringae EC100, EC24, EC229, LMG 5496, EC2, EC101, EC20 (99.81%) |

| P0223 | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens LMG5095/ P. syringae pv. syringae IO 110 (99.54%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens GM 2231/ P. syringae CC457, CC440, Ps02KZ, GAB0016 (100%) | P. syrinage GAB0016 (100%) | P. syringae pv. syringae EC100, EC24, EC229, LMG 5496, EC2, EC101, EC20 (99.81%) |

| P0323 | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens UPB 463, ARGTr 9-1, GM 2231/ P. syringae GAB0016, MUP17/ P. syringae pv. syringae IO 106 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens LMG5095 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens LMG5095/P. syringae pv. syringae IZB1A. IZB2K, IZB1S, IZB2S, ST151, StP26 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens W39.6, GN-In/P. syringae pv. syringae V-85, IZB200, P5-2, EC100, TRR15/P. syringae Susan762 (99.41%) |

| P0423 P0523 P0823 | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens UPB 463, ARGTr 9-1, GM 2231/ P. syringae GAB0016, MUP17/ P. syringae pv. syringae IO 106 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens GM 2231/ P. syringae CC457, CC440, Ps02KZ, GAB0016 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens GM 2231/P. syringae pv. syringae B37/09, IO109 (100%) | P. syringae pv. atrofaciens W39.6, GN-In/P. syringae pv. syringae V-85, IZB200, P5-2, EC100, TRR15 (99.80%) |

| P1123 | P. poae B11_6, B12_8, B12_3, RE*1-1-1, Z9_6 (99.70%) | P. poae B11_5, B11_6, B12_1, B12_3, B12_8, B05_3, W11_4, W12_7 (100%) | Pseudomonas sp. BR2-22, LG1_A6 (99.63%) | P. poae B11_6, RE*1-1-1, Z9_6, B05_3, Z9_2, W11_4 (99.22%) |

| P1323 | P. poae B11_6, B12_8, B12_3, RE*1-1-1, Z9_6 (99.70%) | P. poae Z9_2, Z9_4, Z9_5, Z9_6 (99.68%) | P. poae B11_5, B11_6, RE*1-1-1, B05_3, W11_2, W11_4 W11_9 (98.72%) | P. poae B11_6, RE*1-1-1, Z9_6, B05_3, Z9_2, W11_4 (99.03%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Iličić, R.; Scortichini, M.; Bagi, F.; Pavković, N.; Jelušić, A.; Đorđević, S.; Popović Milovanović, T. Pseudomonas syringae Population Recently Isolated from Winter Wheat in Serbia. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232473

Iličić R, Scortichini M, Bagi F, Pavković N, Jelušić A, Đorđević S, Popović Milovanović T. Pseudomonas syringae Population Recently Isolated from Winter Wheat in Serbia. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232473

Chicago/Turabian StyleIličić, Renata, Marco Scortichini, Ferenc Bagi, Nemanja Pavković, Aleksandra Jelušić, Snežana Đorđević, and Tatjana Popović Milovanović. 2025. "Pseudomonas syringae Population Recently Isolated from Winter Wheat in Serbia" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232473

APA StyleIličić, R., Scortichini, M., Bagi, F., Pavković, N., Jelušić, A., Đorđević, S., & Popović Milovanović, T. (2025). Pseudomonas syringae Population Recently Isolated from Winter Wheat in Serbia. Agriculture, 15(23), 2473. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232473