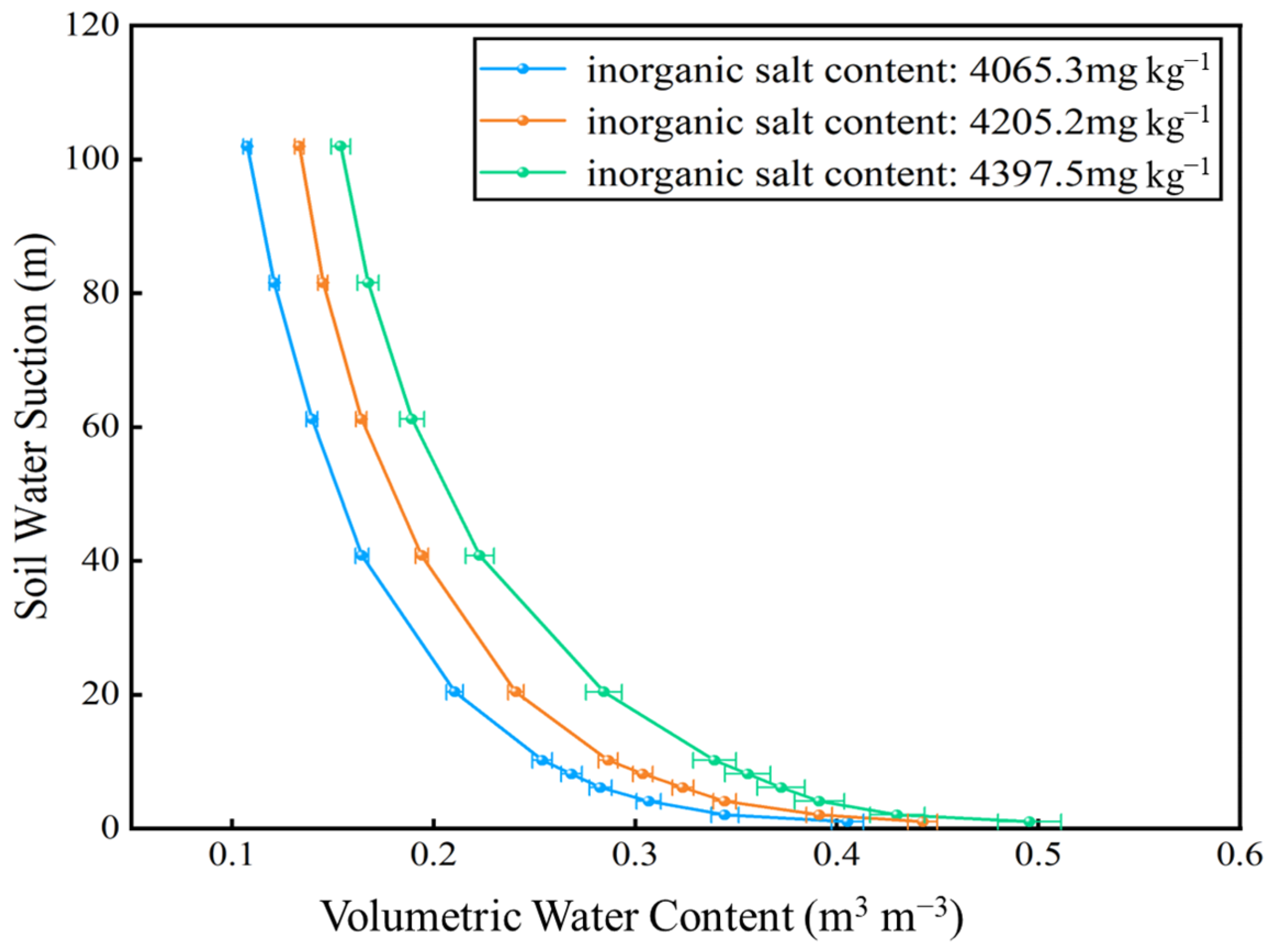

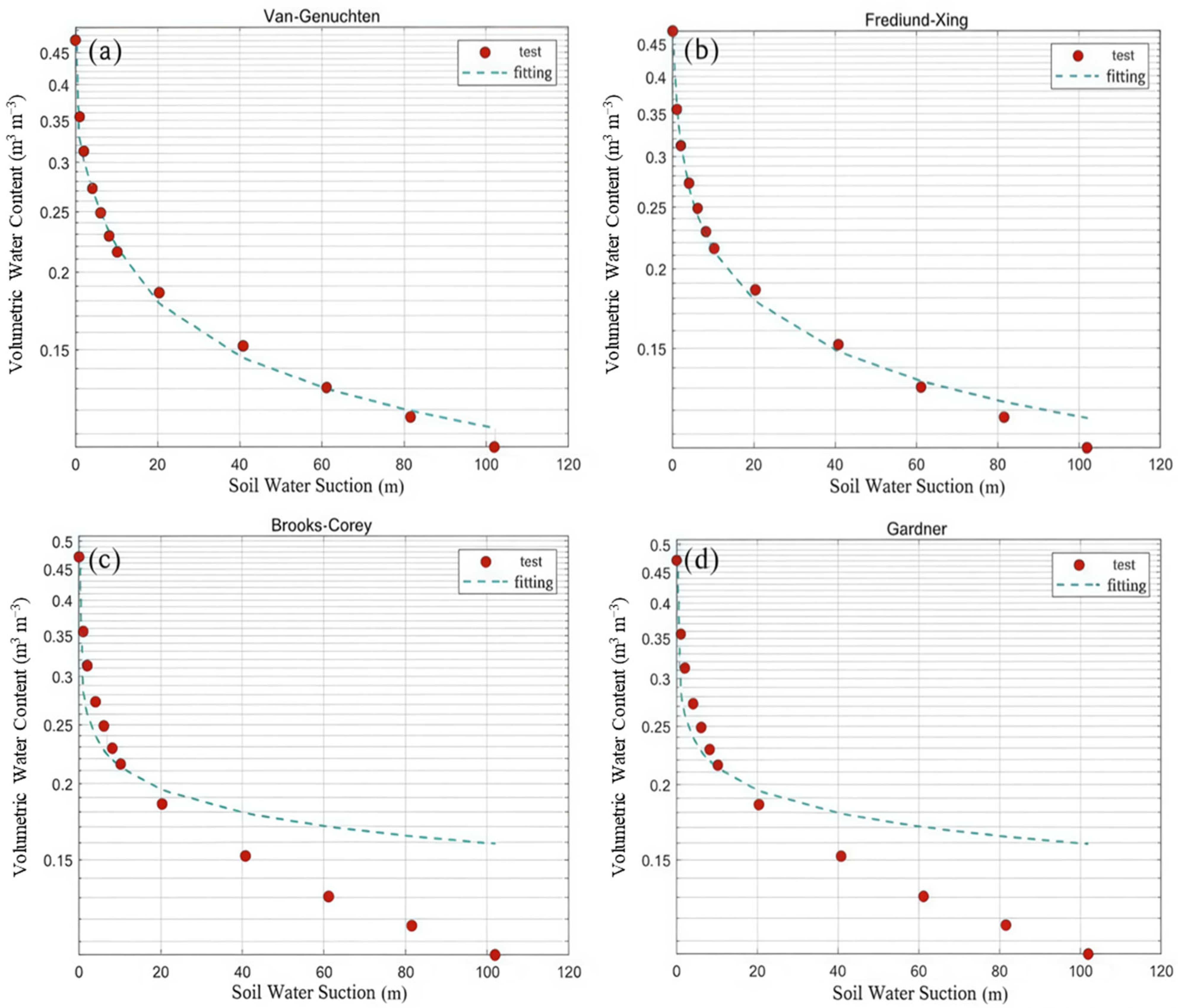

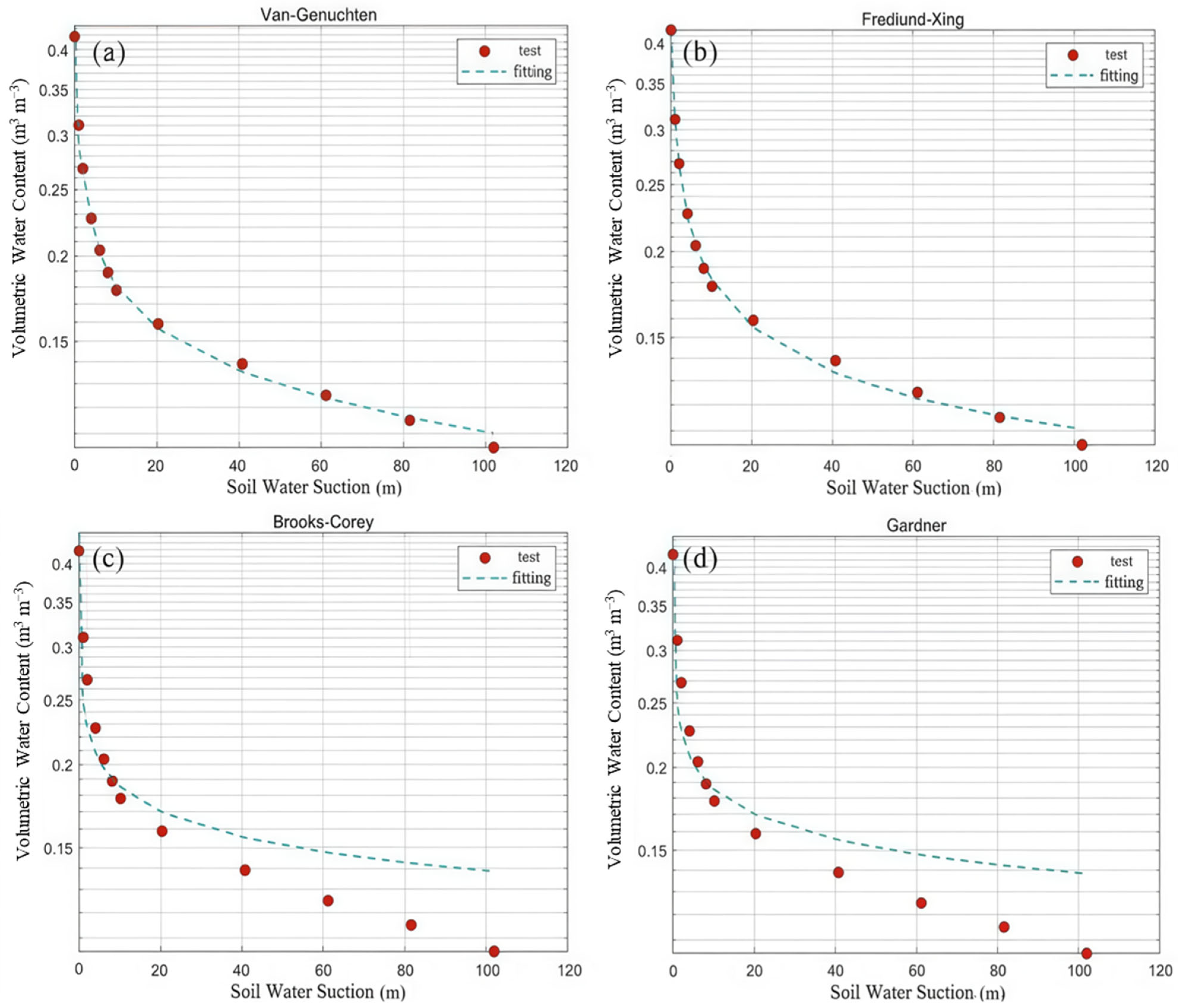

3.2.1. Optimal Model Selection

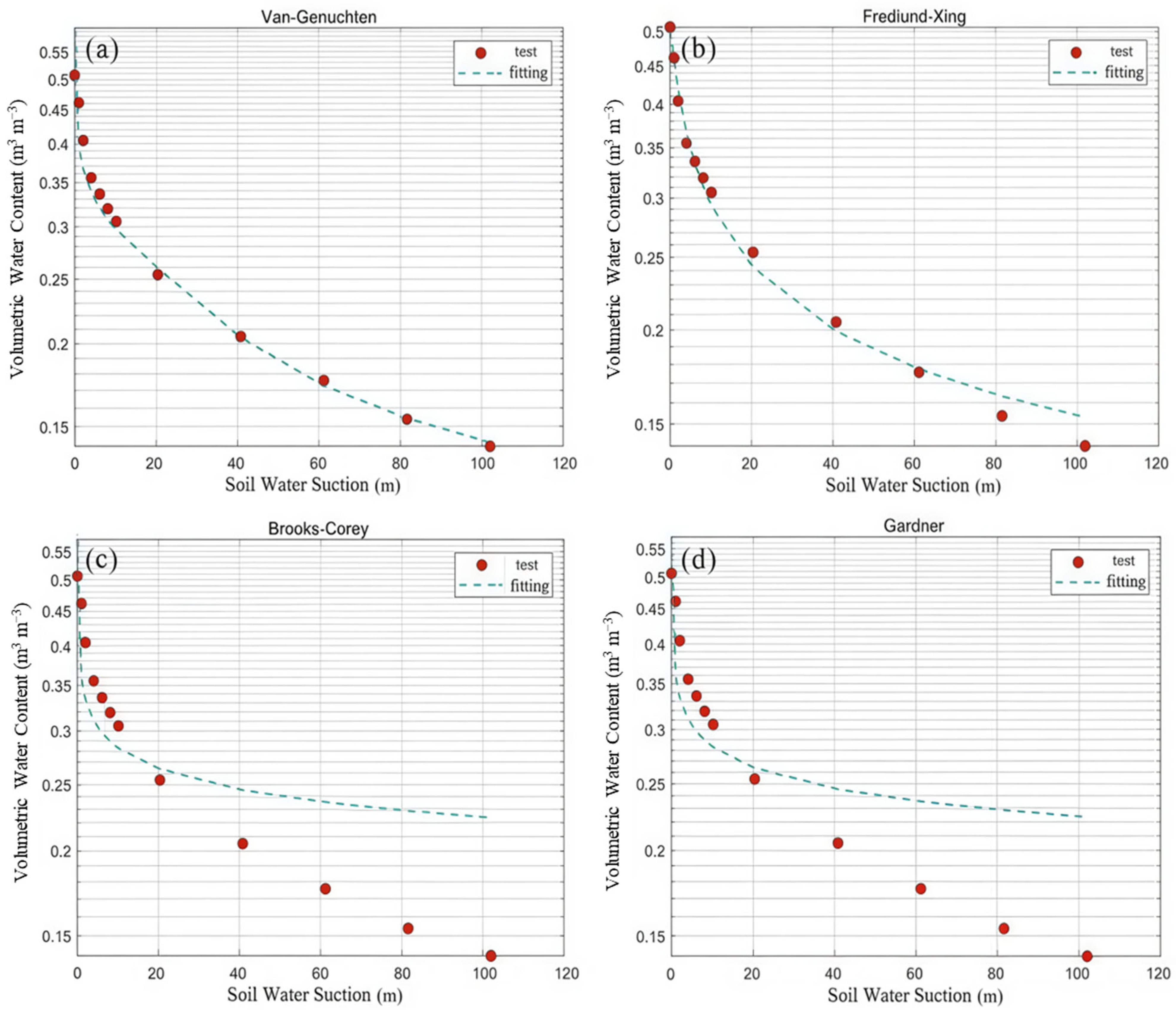

The applicability of four prediction models was evaluated using 18 soil texture samples collected from the Yingjisha study area. Based on the MATLAB platform, the centrifugation test data were fitted with the four models employing the nonlinear least squares method (via the lsqnonlin function) [

43]. The optimal mathematical model, which best matches the three soil textures, was identified by calculating the fitting parameters and the coefficient of determination (R

2) for each model. The results are presented in the figure below.

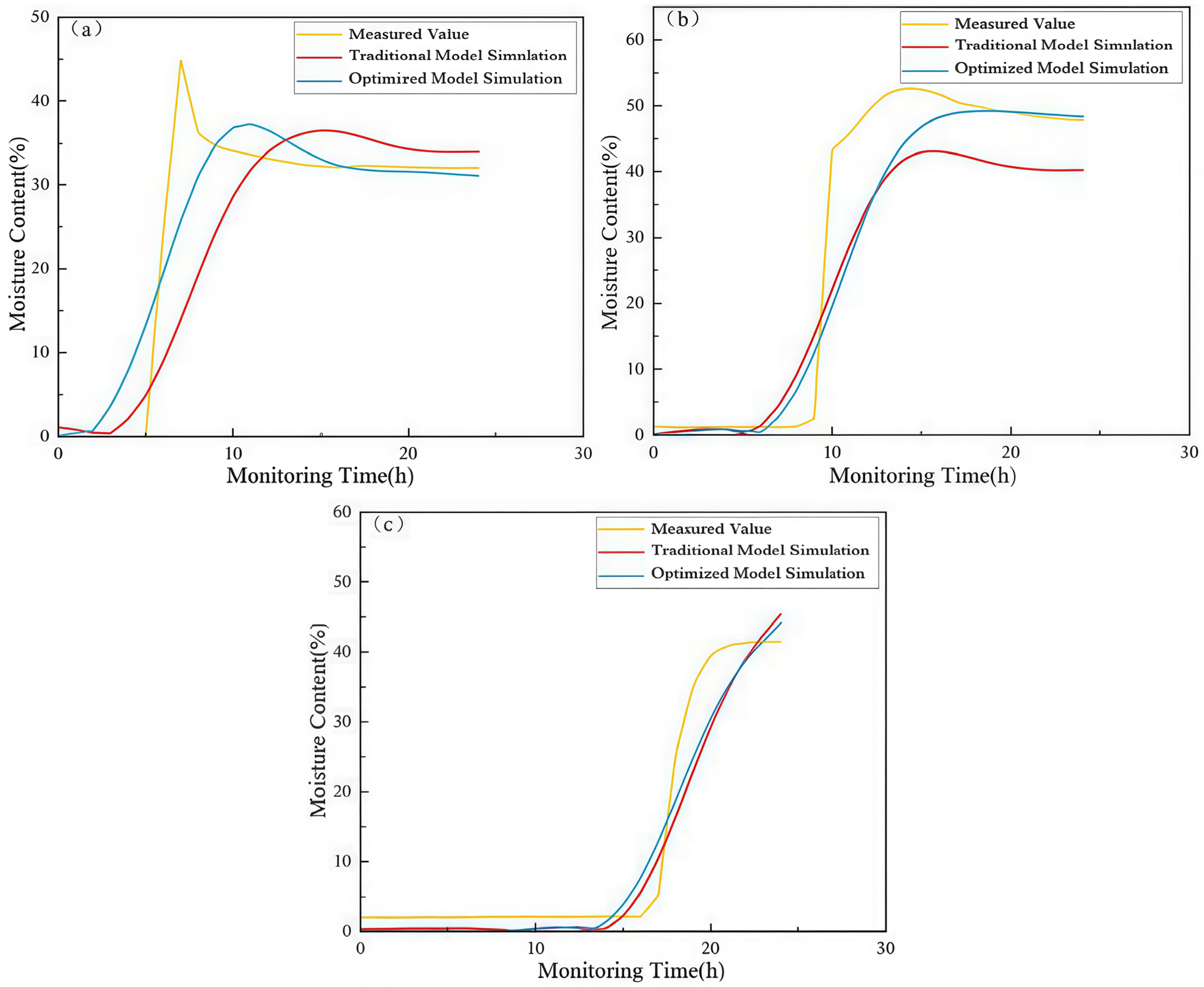

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 compare the fitting performance of four SWCC models for soil samples M1, M2, and M3 saturated with water at a salinity level of 5 g L

−1. Significant differences in model accuracy are observed. The Brooks-Corey and Gardner models show considerable deviations from the experimentally measured data, indicating suboptimal performance under these conditions. These discrepancies may be attributed to oversimplified theoretical assumptions regarding soil structure and water transport mechanisms in these models, which limit their ability to accurately represent complex soil textures.

In comparison, both the VG and FX models achieved satisfactory fitting performance for the SWCCs. Their high adaptability enabled accurate fitting of SWCC data across three distinct soil textures. The fitted curves exhibited strong agreement with experimental measurements, providing a precise description of soil water adsorption and release dynamics under varying pressure conditions. This outcome underscores the flexibility of the VG and FX models in parameterization and theoretical robustness, allowing them to effectively capture the complexities imposed by soil textural variations. However, while the FX model incorporates particle–particle interactions, thereby offering a more accurate representation of complex soil structures, it entails greater computational complexity. Parameter estimation and numerical implementation are more arduous, limiting its practicality for routine applications but rendering it particularly suitable for specialized soils such as expansive or frozen soils [

44].

The fitting accuracy of each model was evaluated based on the parameters derived from the fitting process, which are summarized in

Table 7 and

Table 8. A comparative analysis of these parameters elucidates the divergence in model performance during the fitting procedure and their respective capacities to characterize the SWCC. This assessment provides critical insights for subsequent model selection.

The fitting performance of the four models was quantitatively assessed by comparing the key evaluation metrics—the coefficient of determination (R

2), root mean square error (RMSE), and sum of squared errors (SSE)—derived from the model calibrations. As summarized in

Table 8, the VG and FX models, both three-parameter formulations, demonstrated excellent capability in fitting the SWCCs of Yingjisha soil samples under varying salinity conditions. Calibration results indicated that the R

2 values for both models exceeded 0.85, confirming their ability to accurately capture the variation trends of the SWCCs. Among all models, the VG model yielded the smallest SSE, indicating the smallest discrepancy between the fitted and observed values and thus representing the best overall fit. Furthermore, the VG model achieved the highest fitting accuracy across all three soil samples (M1, M2, M3), whereas the Gardner, FX, and Brooks-Corey models exhibited slightly inferior applicability and stability. In conclusion, the VG model provided the most accurate representation of the soil water characteristics for the investigated samples under different solution mineralization levels, establishing it as the most suitable candidate for subsequent parameter optimization studies. Therefore, the VG model was selected for further optimization work in this research.

A targeted analysis of the fitting evaluation results for the four models presented in

Table 8 indicates that all models exhibited superior performance when fitting the M2 (silt soil) samples compared to the M1 (silty sand) and M3 (sandy loam) samples. For the M2 samples, the fitting accuracy, as reflected by the R

2 values of all four models, was notably high, with each exceeding 0.9. Specifically, samples M2-3 and M2-4 demonstrated the best fit, whereas sample M3-7 showed the poorest performance. This performance discrepancy can be attributed to the finer sand particle size of the M2 soil relative to the M1 and M3 soils, resulting in distinct soil structures and hydrological characteristics. The textural and structural properties of the silt soil promote more regular patterns during water adsorption and release processes. Finer particles generally enhance soil water-holding capacity, and during desorption, capillary suction is more pronounced, leading to a stronger agreement between the fitted SWCC and measured data, thereby facilitating model calibration. In contrast, the M1 and M3 samples contain coarser sand particles. Additionally, the M3 sample exhibits a higher soluble salt content, which can cause soil compaction and alter interparticle pore structure. These changes diminish the effect of capillary suction during desorption, resulting in a less accurate model fit. Furthermore, the overall fitting performance for the M1 samples was generally better than that for the M3 samples, suggesting that the properties of silty sand are more consistent with the assumptions underlying the models, and the variation pattern of the M1 SWCC is more amenable to representation by these models. The complex characteristics of sandy loam soil, however, introduce considerable errors during the fitting process. In summary, the performance of traditional SWCC models is less ideal for sandy loam soils, underscoring the need to optimize existing models or develop alternative approaches tailored to the specific properties of this soil texture.

3.2.2. Development of a SWCC Model Under Various Mineralization Conditions

- 1.

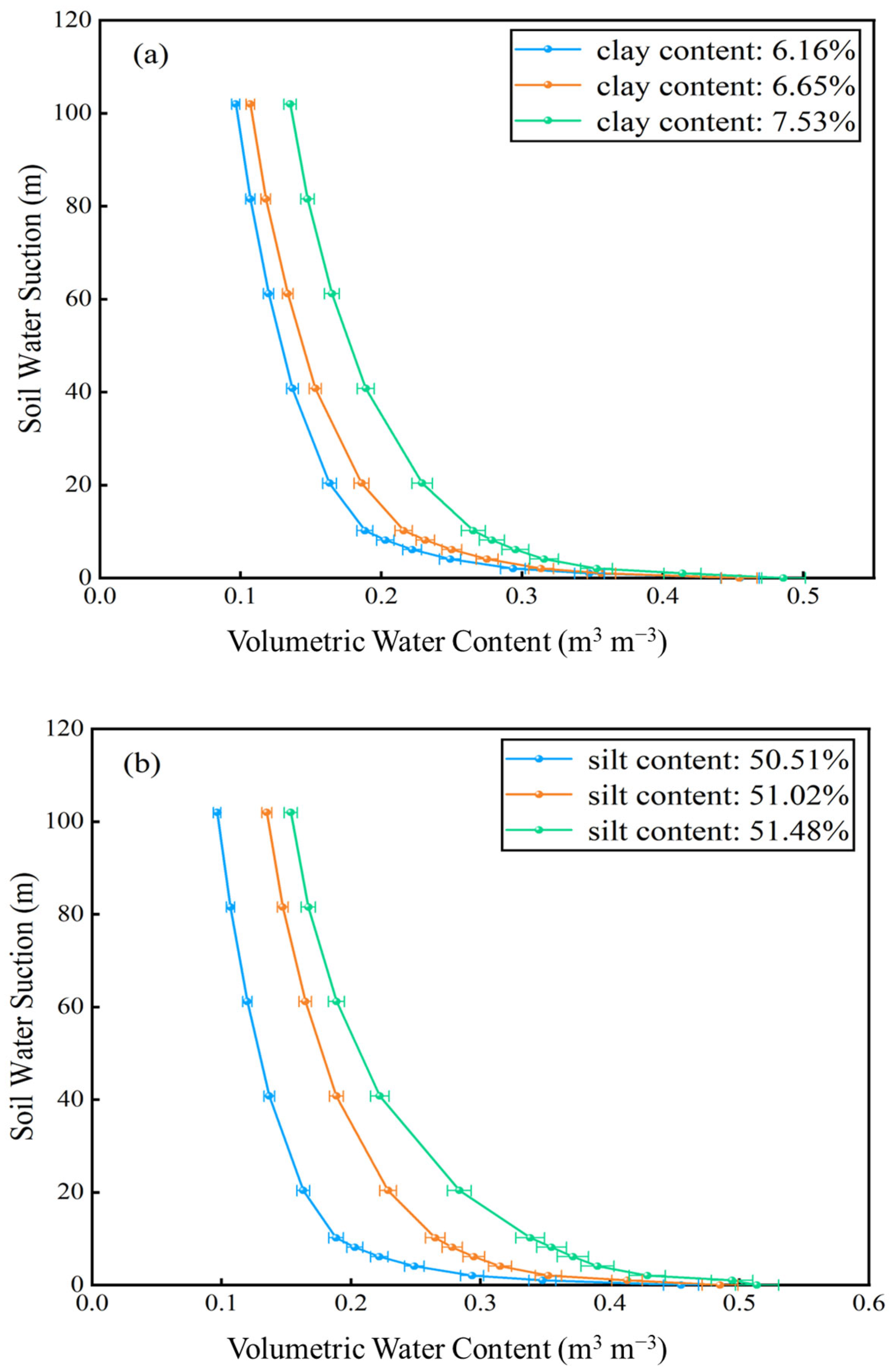

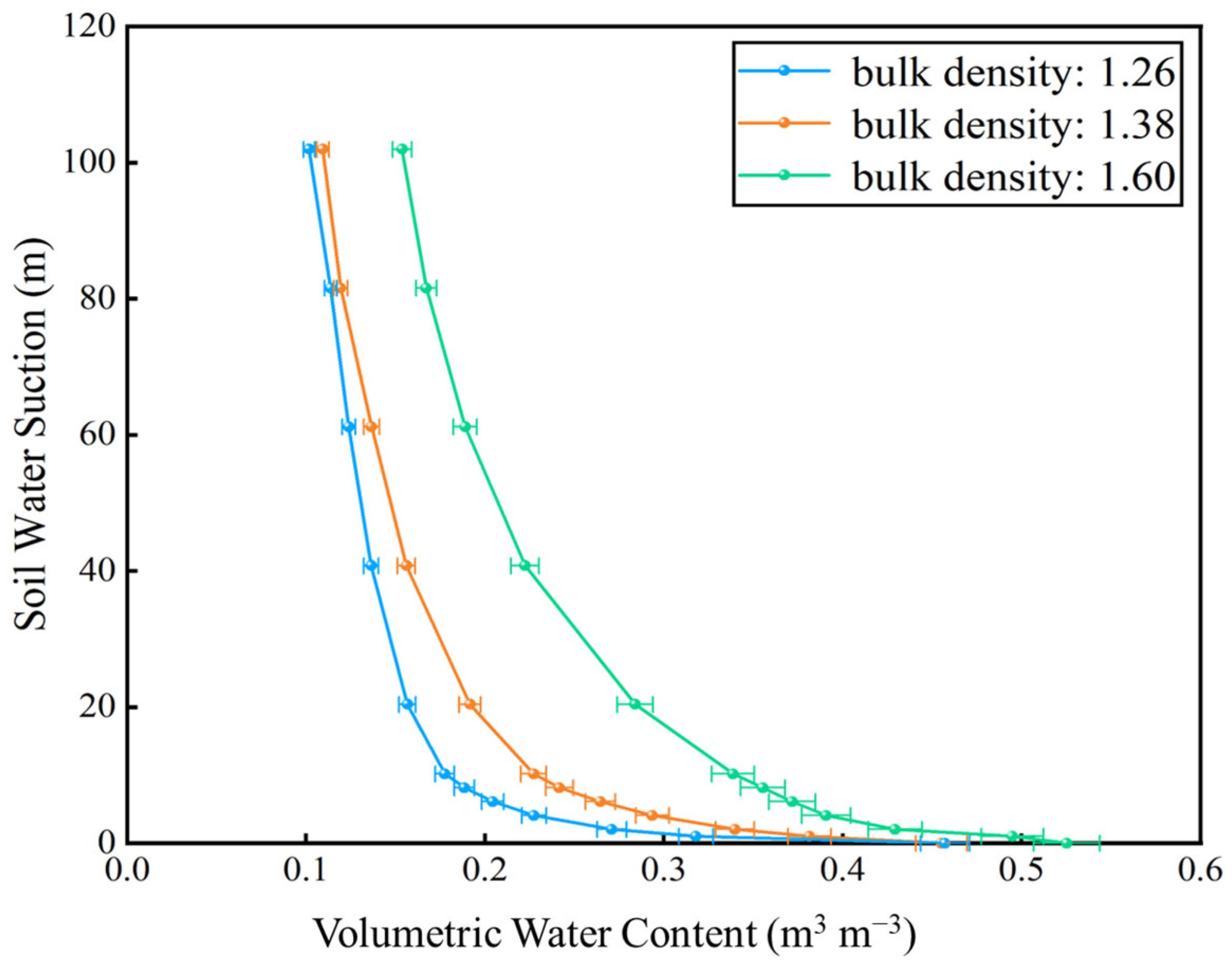

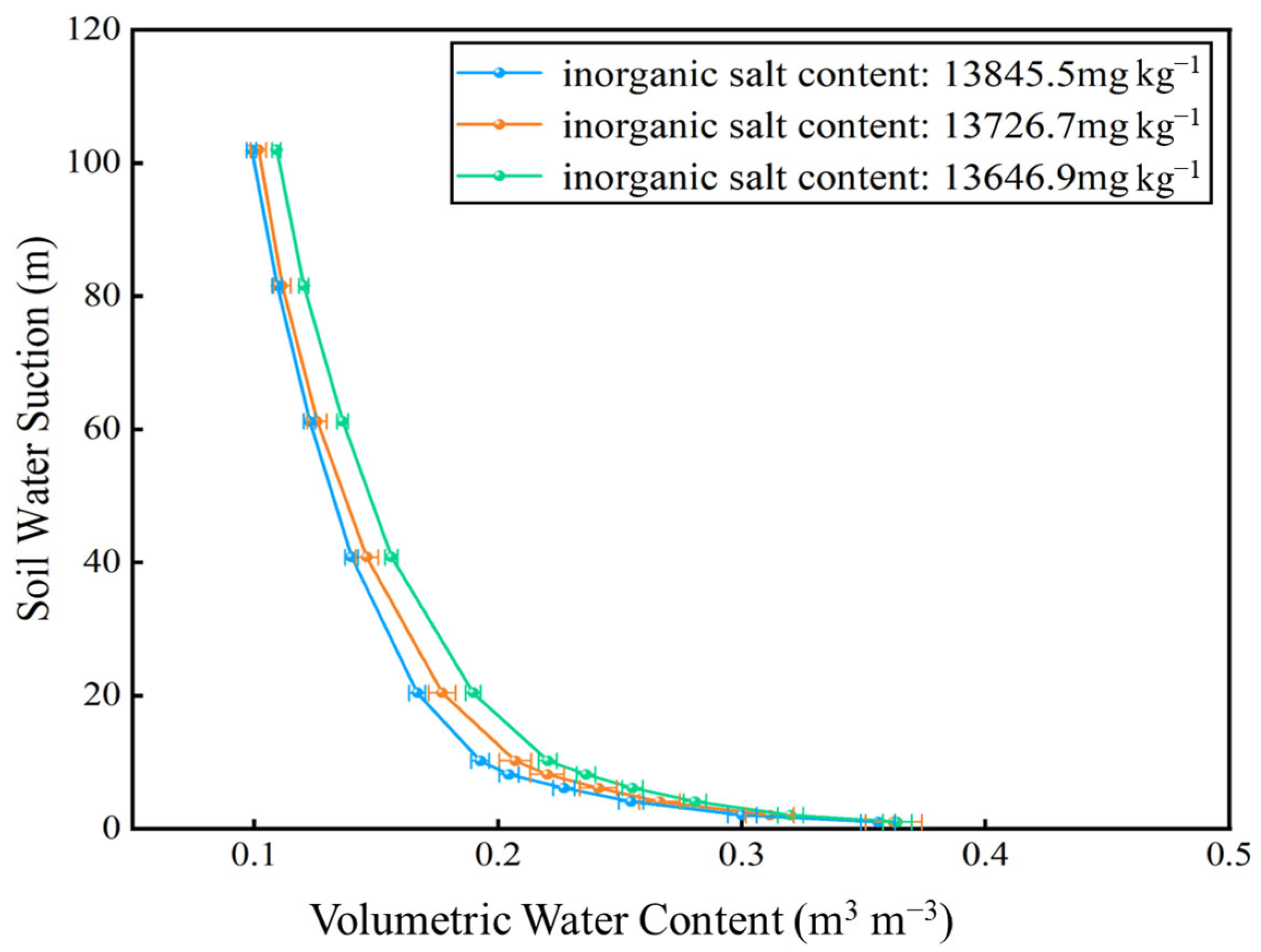

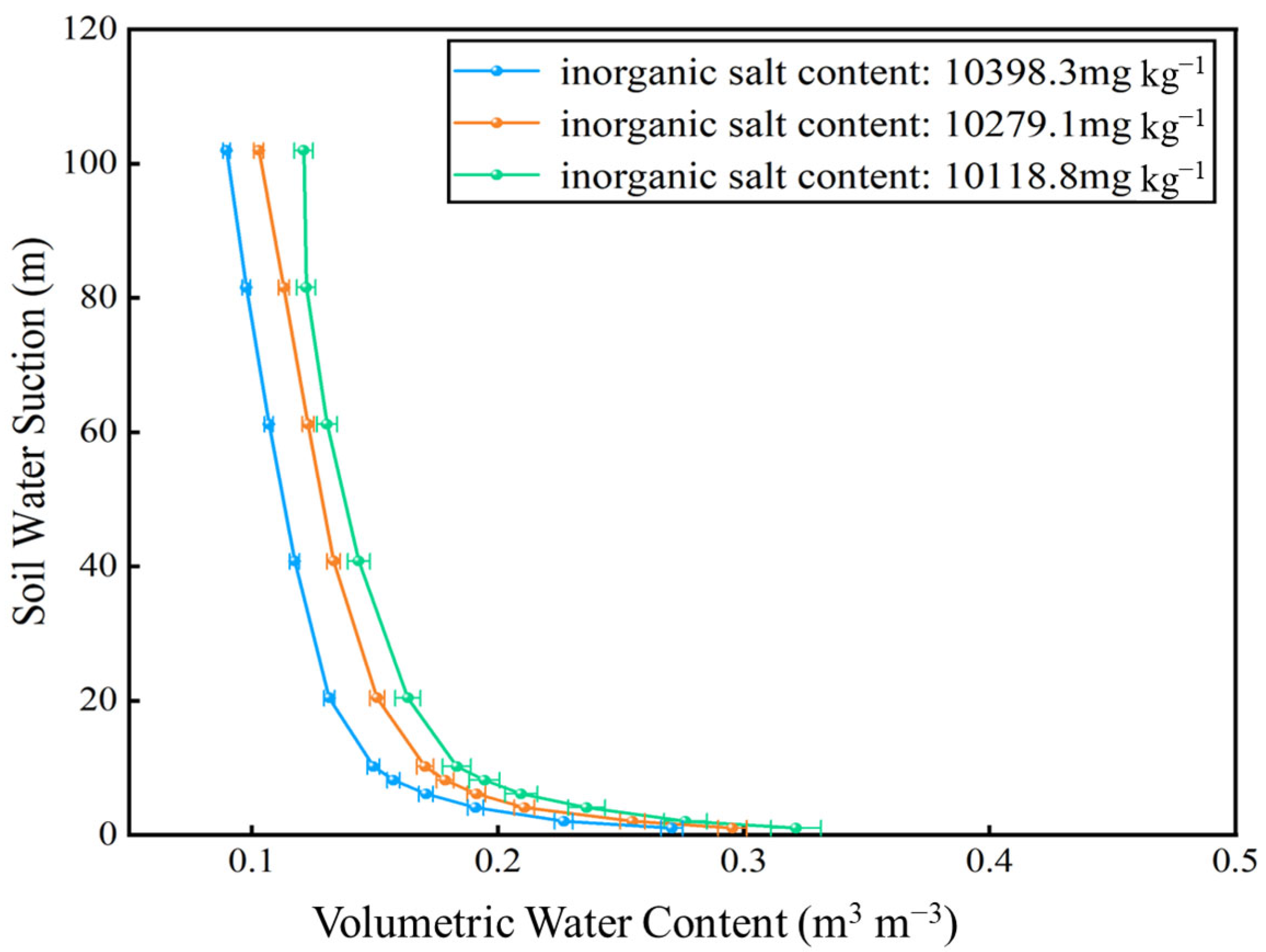

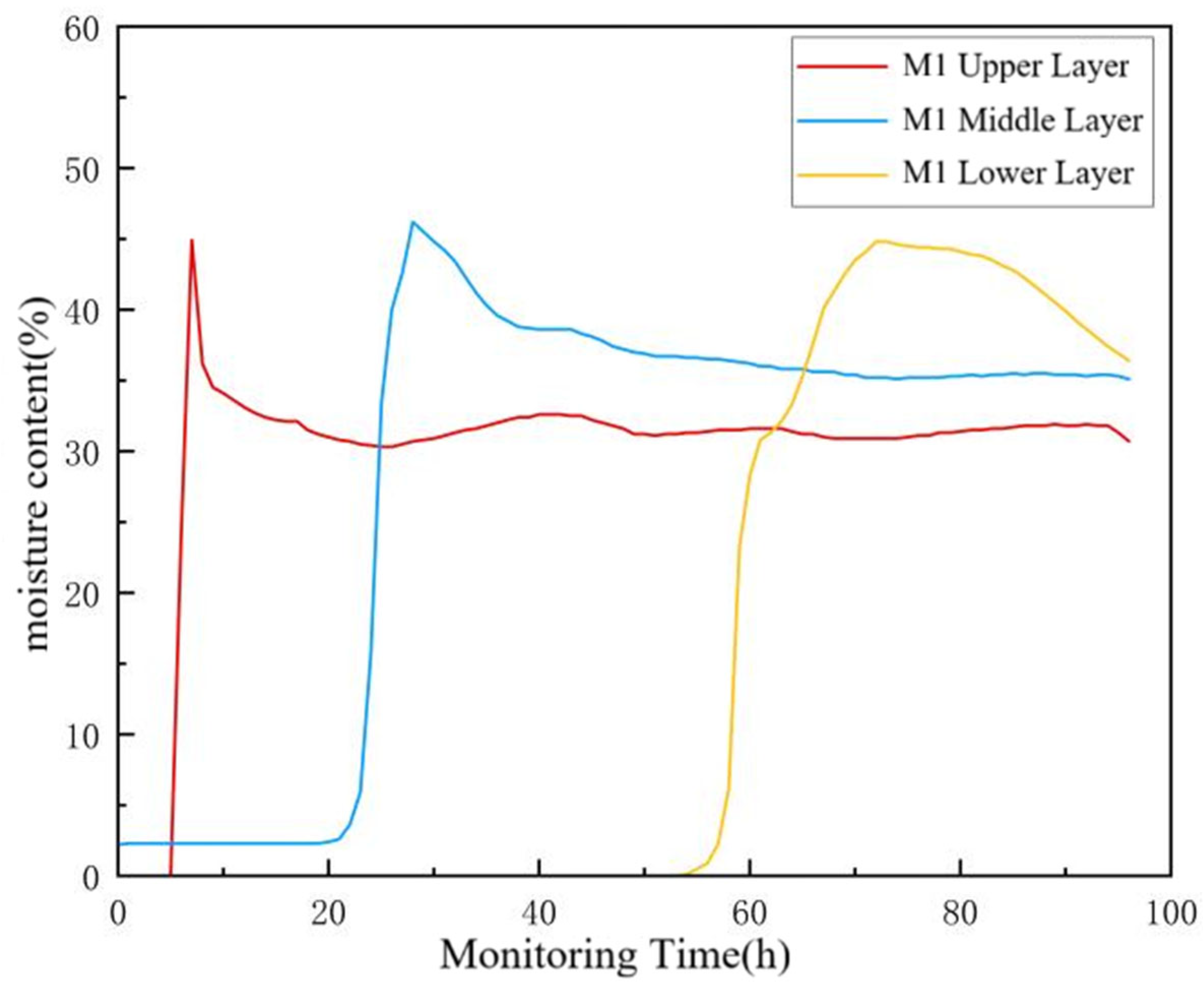

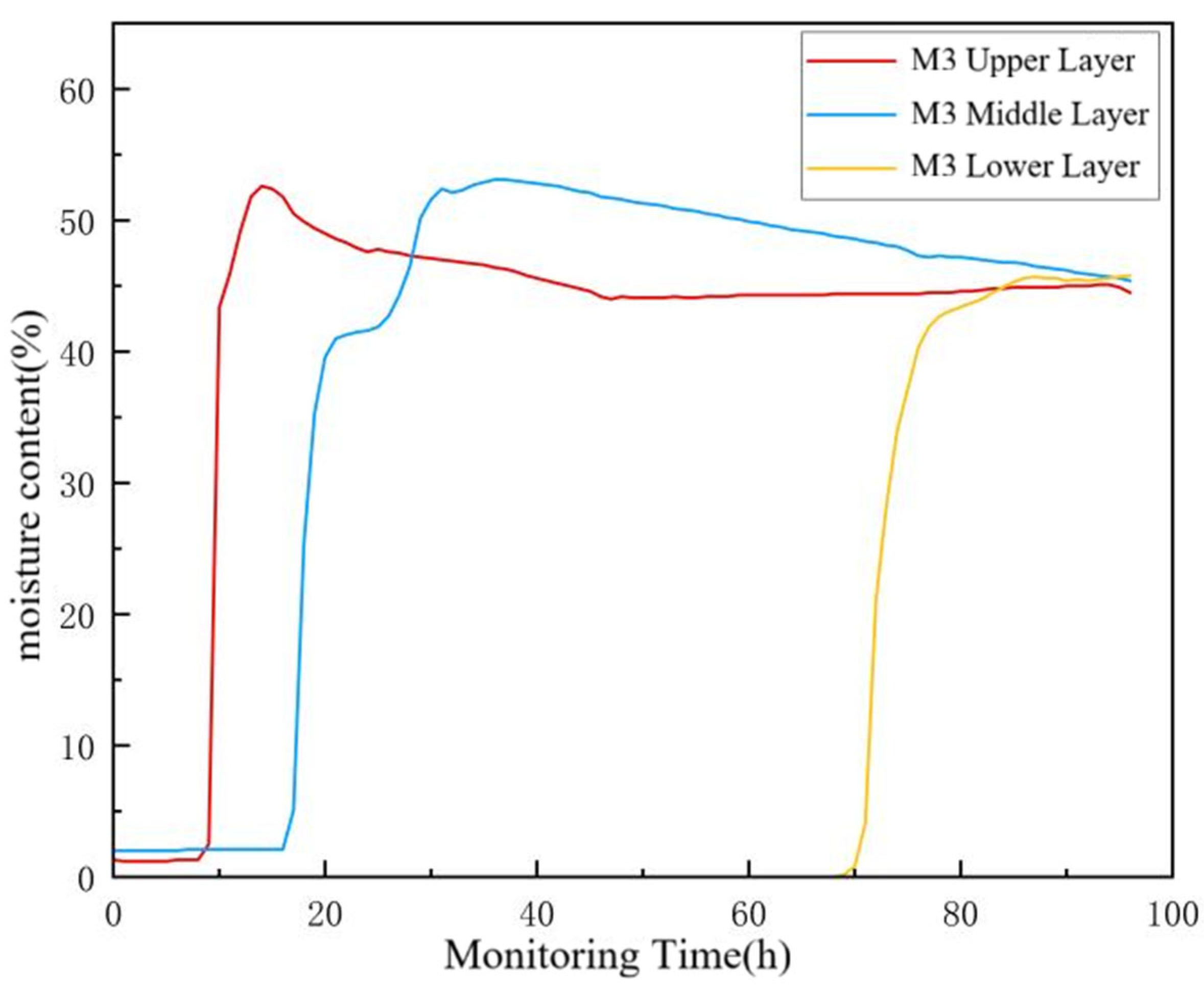

Effect of different mineralization degrees on the SWCC

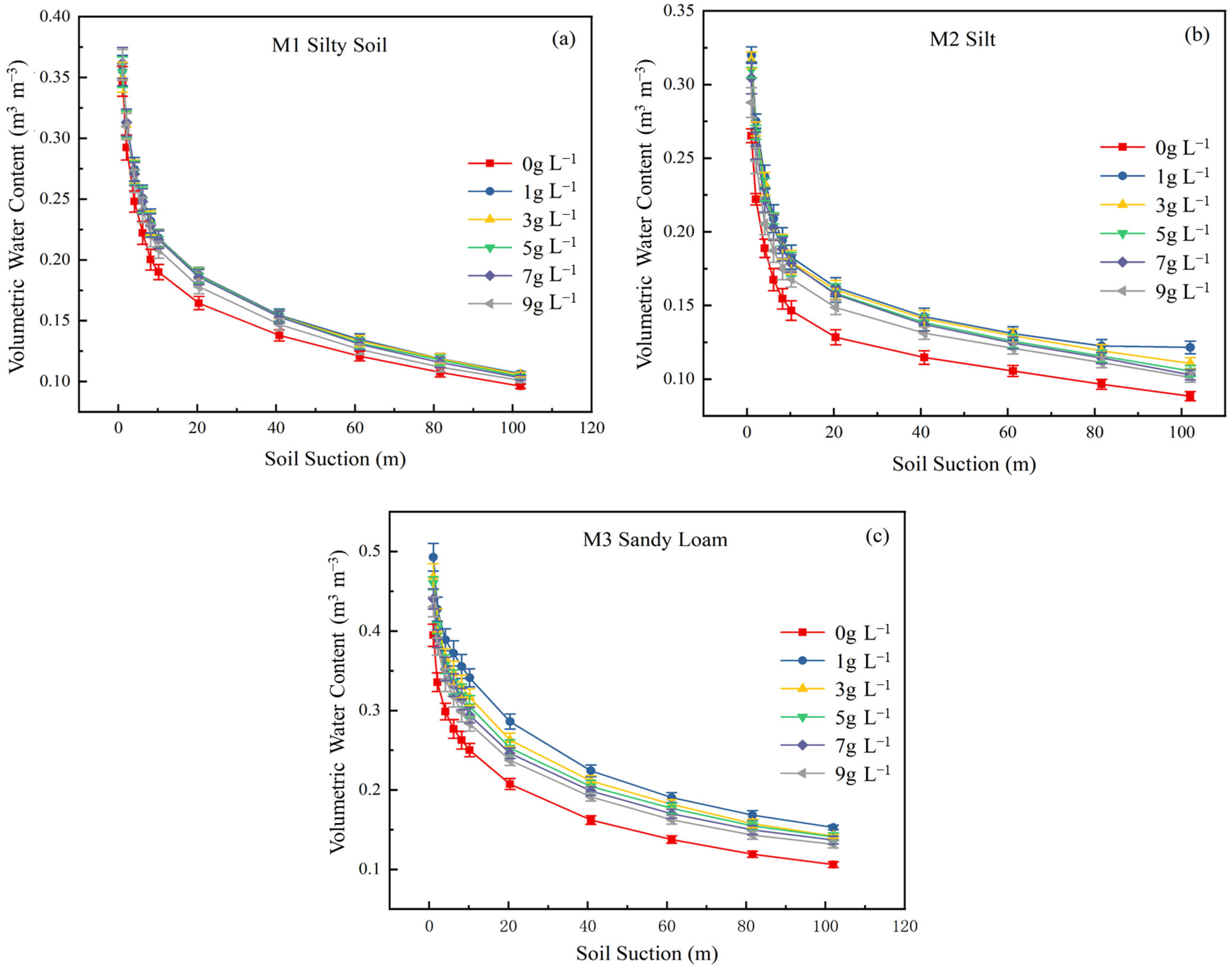

This study employed NaCl solutions with salinity levels of 1, 3, 5, 7, and 9 g L

−1 to treat three soil texture samples (M1, M2, M3). The SWCCs for these samples under different salinity conditions are presented in

Figure 11. The results indicate that the volumetric water content of all soil samples decreased as soil suction increased. Treatment with saline solutions enhanced the soil water retention capacity to some extent during specific stages. However, the water retention capacity did not increase monotonically with rising salinity levels; instead, it initially increased and then decreased, a trend particularly pronounced under high suction conditions. This phenomenon can be attributed to the following mechanisms: compared to pure water, low-salinity solutions contain a considerable number of ions. Since soil particle surfaces are charged, they can adsorb a significant amount of ions from the solution—typically up to three layers. This adsorption process increases the specific surface area of the soil particles, thereby facilitating the retention of more water molecules. Furthermore, during the desorption process, a portion of the salts originally dissolved in the soil solution precipitates and forms crystals. This precipitation alters the soil microstructure, increases the proportion of small pores, and consequently enhances the water-holding capacity of the soil [

45]. However, an excessive accumulation of salt ions increases soil dispersibility. Excessively high salinity accelerates soil salinization, which disrupts soil structure by promoting the dispersion of soil particles and consequently diminishes the water-holding capacity. This explains the observed decline in water-holding capacity of soil samples treated with solutions having a salinity exceeding 1 g/L [

46].

Furthermore, the slope of the soil water characteristic curve decreases with increasing soil suction. This occurs because, as soil suction rises, the drainage process within the soil shifts from being dominated by the emptying of large pores to being controlled by the drainage of small and medium-sized pores [

47]. The large pore system significantly regulates water movement in the low suction range. With increasing suction, water is progressively retained in smaller pores, making the dewatering process more difficult. Treatments involving water of varying mineralization levels further result in only small pores being able to retain some moisture during the low suction stage. This leads to a significant enhancement of the soil’s water retention capacity, causing the water retention curve to exhibit a steeper shape.

The shift magnitude observed in the SWCCs of the three soil samples (M3, M2, M1) diminished progressively with increasing solution salinity. This pattern suggests that the M1 saline soil, having a high inherent background salt content, responded relatively weakly to variations in solution salinity; consequently, the effect of salinity on its SWCC was minimal. In contrast, the M2 soil, with a lower initial salt content, exhibited a more pronounced response, wherein changes in solution salinity markedly influenced its water characteristic curve. Research indicates that the water-holding capacity of saline soil initially increases with salt content but declines as salinization intensifies beyond a certain threshold. Variations in solution salinity significantly altered the SWCCs of the samples, an effect strongly correlated with their initial salinization degree. Across the examined matrix suction gradients, the SWCCs for different treatments demonstrated notably parallel characteristics. This parallelism implies a consistent influence of matrix potential on the trend of water content change across treatments, whereas localized slope differences are mainly attributed to the differential impact of the salt concentration gradient on pore structure parameters.

- 2.

Effect of different mineralization degrees on key model parameters

The parameter α in the VG model governs the soil pore-size distribution, primarily influencing the horizontal position of the SWCC. The parameter n characterizes the pore-size distribution uniformity, which dictates the steepness of the curve’s inflection point. The saturated water content [

48,

49], θs defines the upper limit of the model’s predictive range by representing the maximum volumetric water content under saturated conditions.

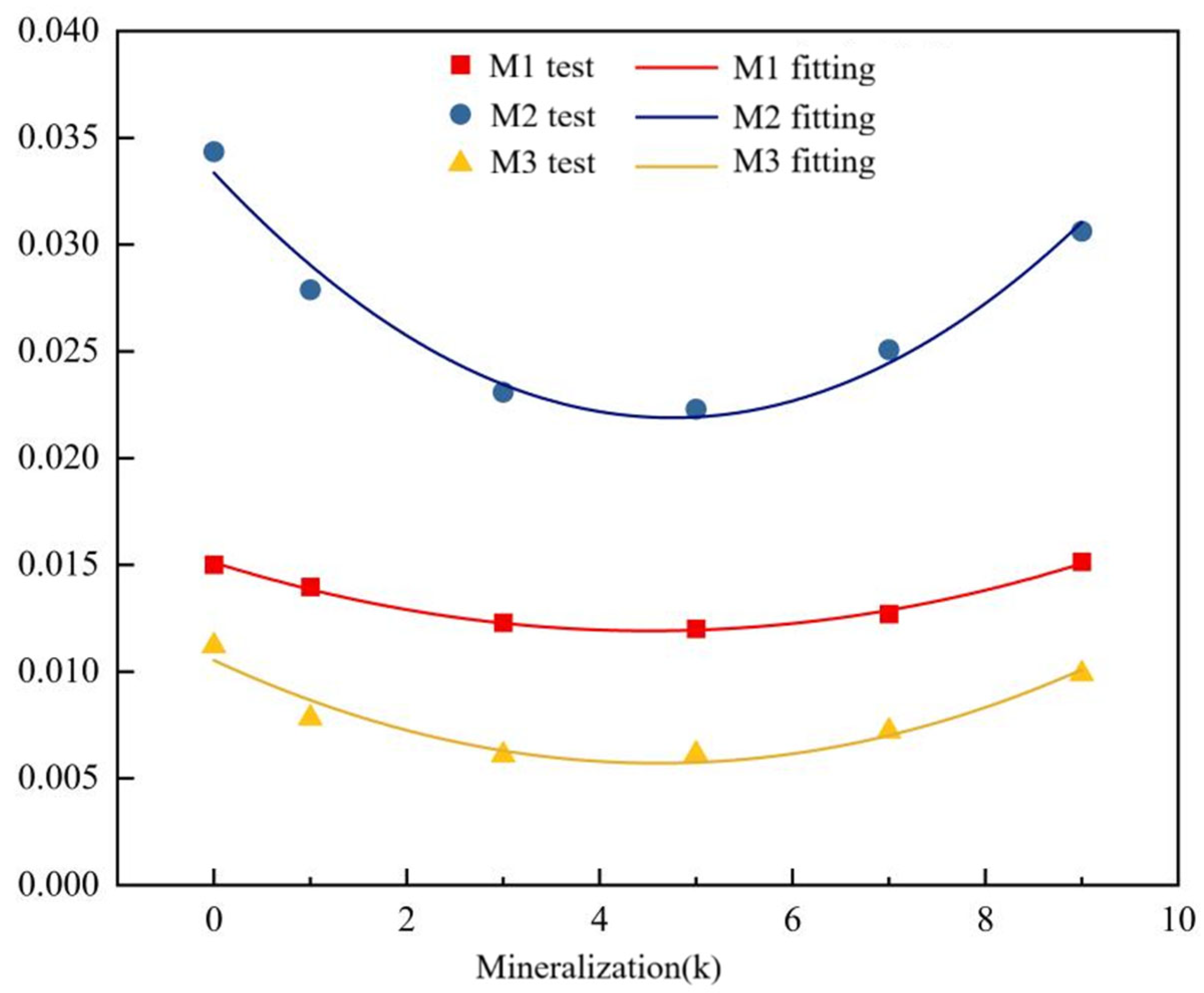

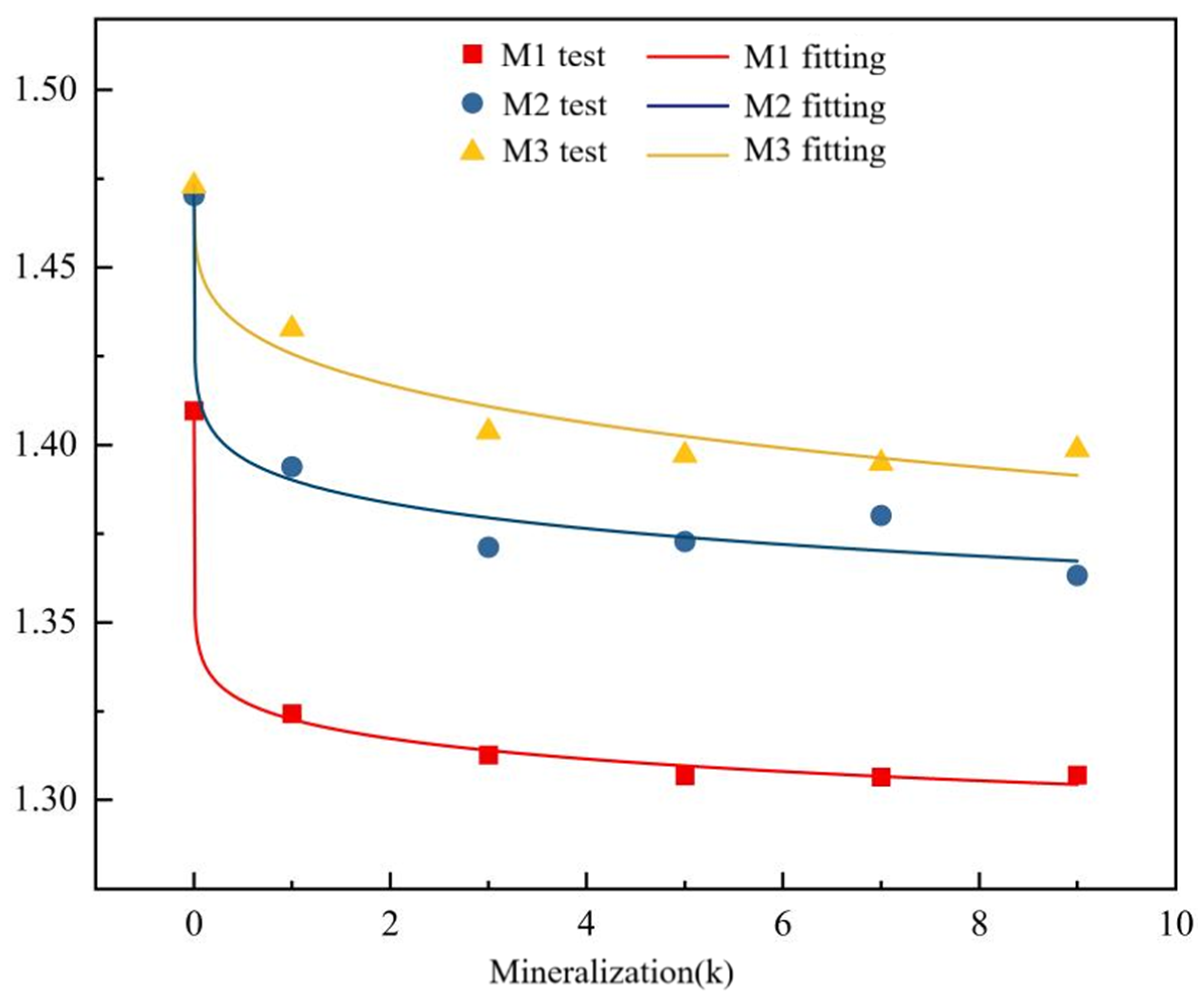

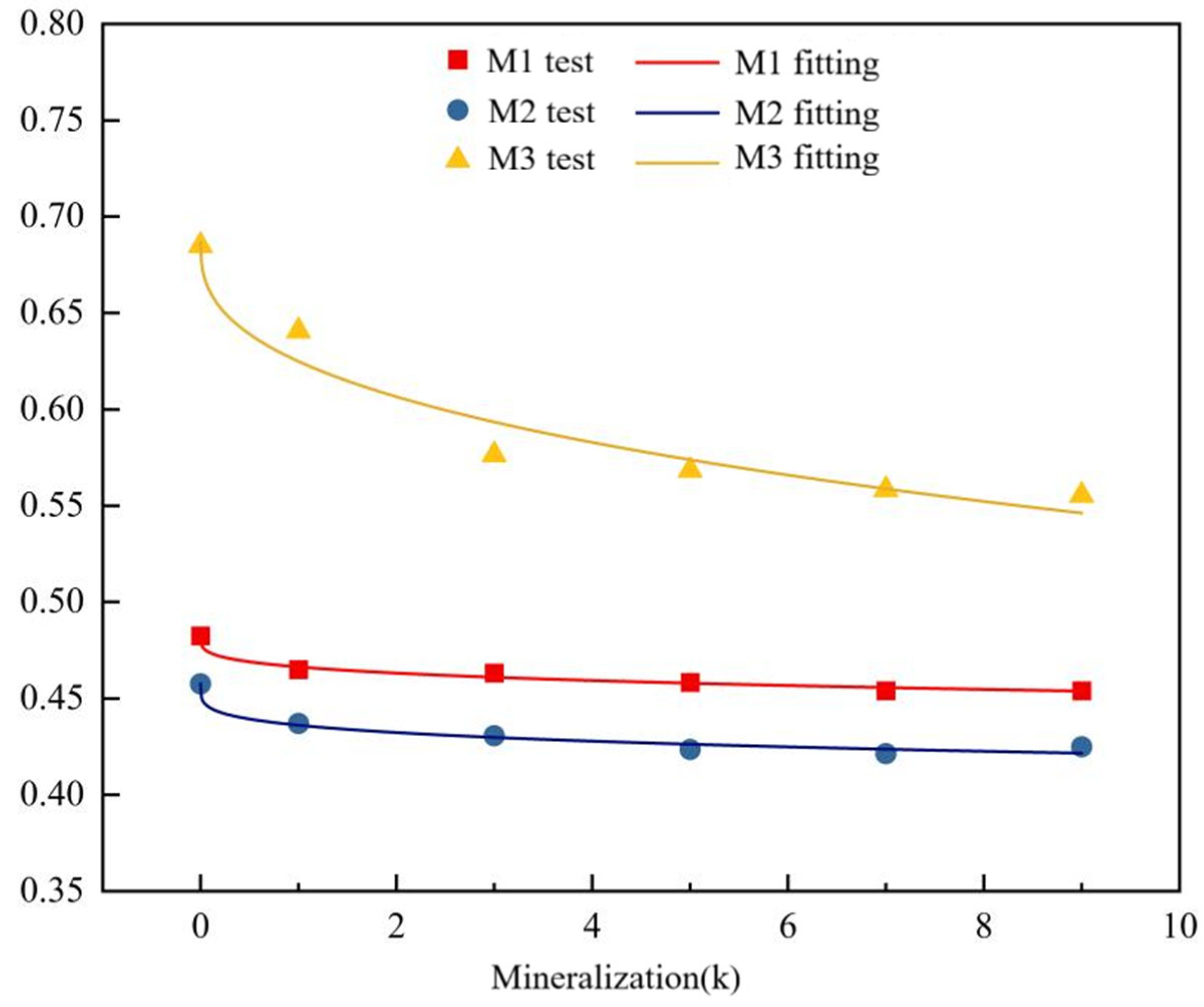

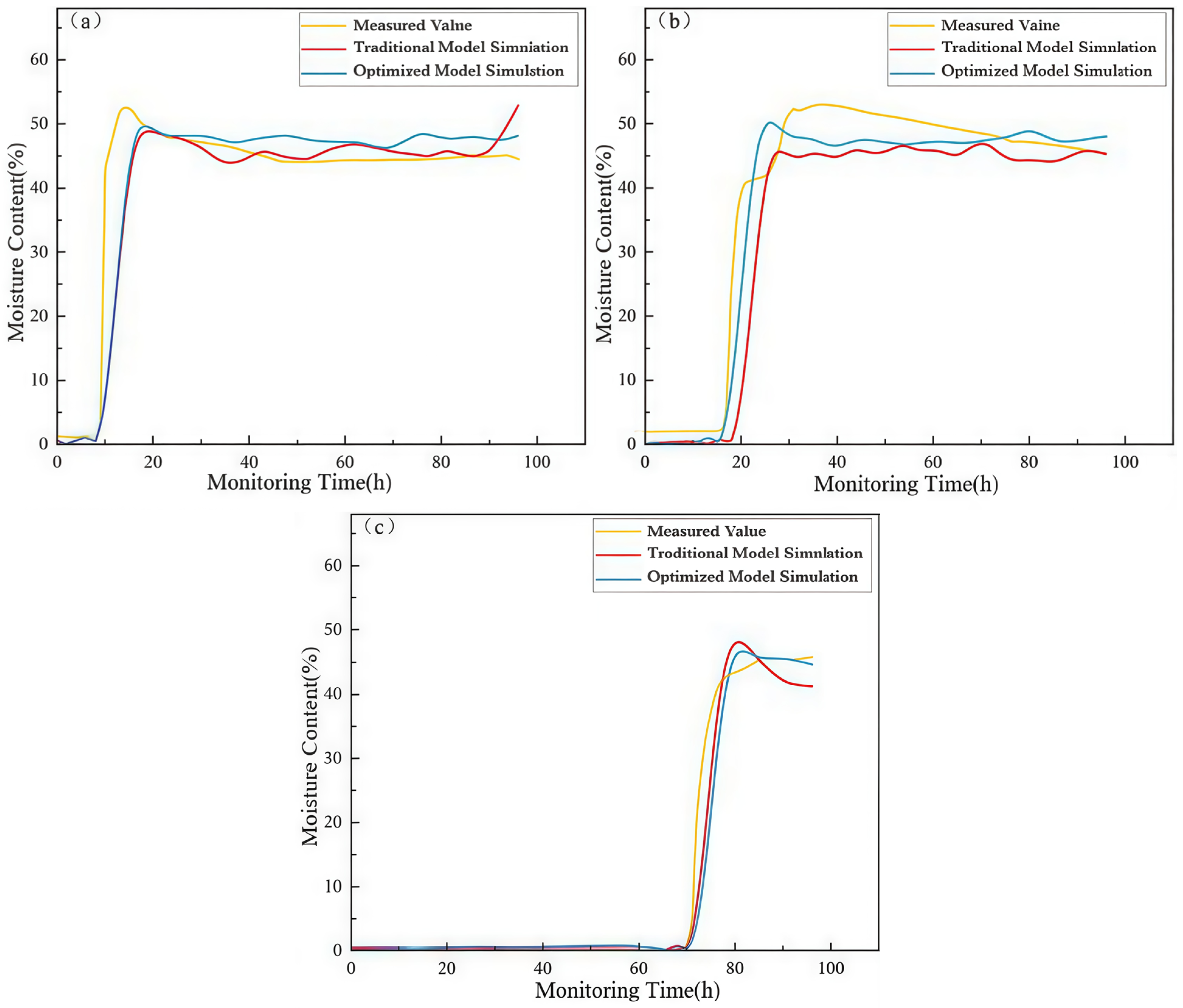

Using MATLAB, we simulated and quantitatively analyzed the response of the VG model parameters (α, n, θs) to varying solution mineralization levels (k) for three soil samples. The analysis established explicit functional relationships between the model parameters and k, thereby quantifying the influence of salinity on the soil hydraulic properties. As shown in

Figure 12,

Figure 13 and

Figure 14.

As illustrated in

Figure 12, the VG model parameter α for the three soil samples varies non-monotonically with increasing solution mineralization, following a quadratic polynomial trend [

50]. Specifically, α initially decreases as mineralization rises, then increases after reaching a minimum, with the symmetry axis of all curves located near approximately 4.3 g/L. The slope change of the curve for sample M3 is markedly steeper than those for M1 and M2, indicating a greater sensitivity of M3 to variations in mineralization. Since α is defined as the reciprocal of the air-entry pressure, it reflects the soil’s hydraulic behavior during initial drying; a higher α value corresponds to more efficient drainage performance.

Figure 13 reveals a gradual decline in the parameter n with increasing mineralization, a trend well captured by a power function [

50]. The parameter n characterizes the nonlinearity of the soil water retention curve, and its value is indicative of the soil’s water-holding capacity. The slopes of the relationship between n and mineralization decrease consistently across the three soil samples. The inflection point follows the order M3 > M2 > M1. This progression is attributed to increased mineralization promoting soil particle flocculation and altering pore geometry, which in turn influences the shape parameter n of the retention curve.

As shown in

Figure 14, the saturated water content θs decreases progressively with rising mineralization, demonstrating a reduction in water retention under high salinity conditions. This inverse correlation is effectively modeled by a power function. The slope of the θs-mineralization curve is significantly steeper for M3 than for M1 and M2, and the overall θs values adhere to the ranking M3 > M1 > M2. The more retentive pore structure of M3 allows it to maintain a higher θs even at elevated mineralization levels. The diminishing effect of further increases in mineralization on θs underscores the importance of the soil’s innate salinity level in modulating its response.

- 3.

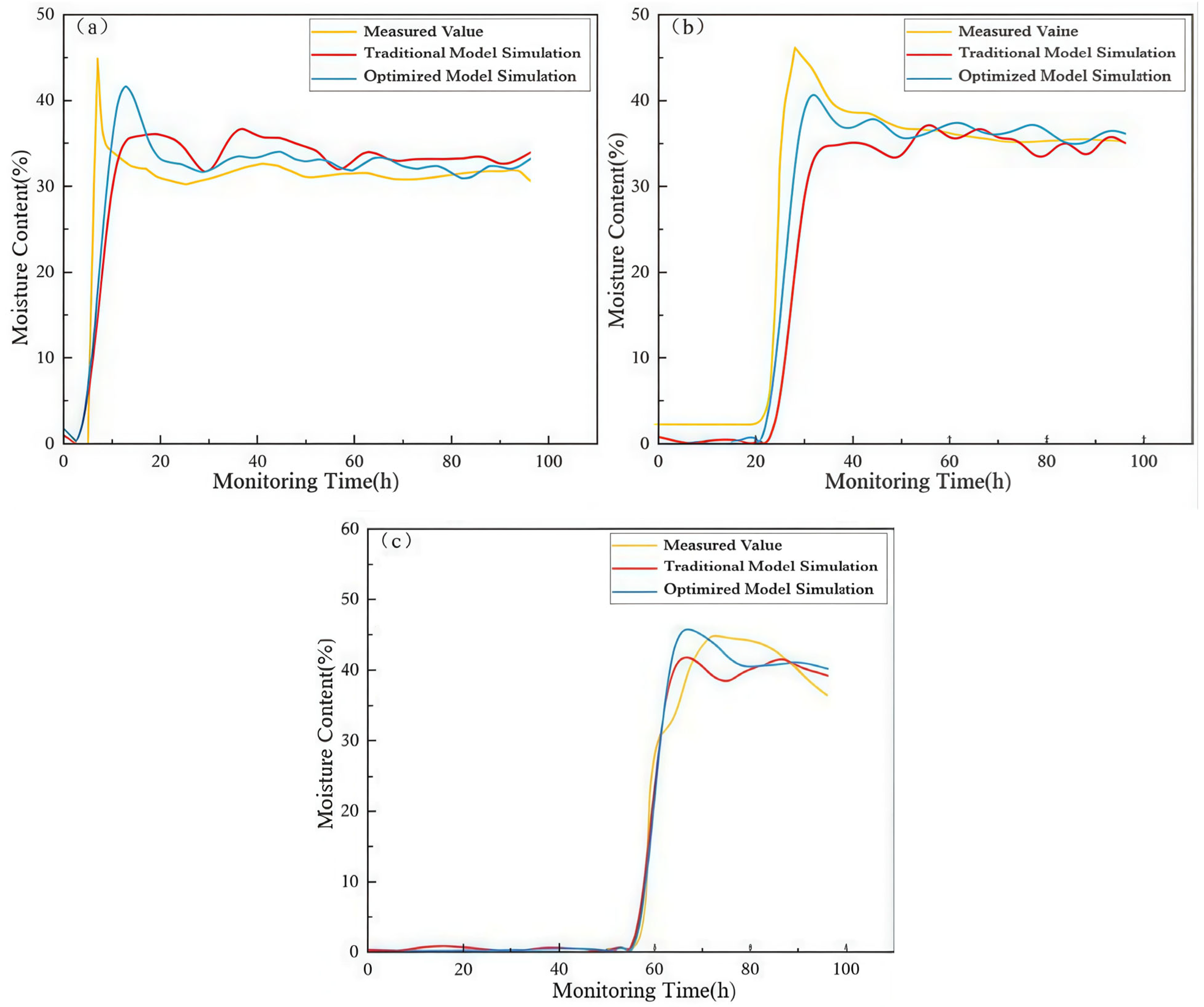

Model establishment under different mineralization conditions

For soil samples M1, M2, and M3, the symmetry axes of the fitted function curves were nearly identical, clustering around a mineralization level of approximately 4.3 g L

−1. Based on these patterns, the functional relationships for θs(k), n(k), and α(k) were formulated as Equations (14)–(16), respectively. The optimized VG model, incorporating the influence of mineralization level, is presented as Equation (17). This study establishes, for the first time, a quadratic function for α (k) and power functions for n(k) and θs(k), overcoming the limitations of traditional model assumptions and thereby constructing a mineralization-responsive VG model framework. In these equations, (k) represents the solution mineralization level in g/L.

The functional relationships between the key VG model parameters (α, n, θs) and the mineralization level (k), as defined by Equations (14)–(16), were incorporated into the fundamental model equation (Equation (5)). This integration yielded an optimized VG model that explicitly accounts for salinity effects (Equation (17)). The fitting parameters (d, e, f, g, i, p, q, r, s) associated with these functions are provided in

Table 9.

The quadratic/power-law function was selected as an empirical model in this study, guided by the observed patterns in our experimental data. Its validity was confirmed through systematic comparative experiments. Moreover, subsequent results from soil column infiltration tests demonstrate that this model robustly captures the intrinsic relationships between key variables, showing strong explanatory power and reliability.