Comparative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Ovaries from Two Pig Breeds with Contrasting Reproductive Phenotype

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Animals and Sample Collection

2.2. Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) Staining

2.3. Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA)

2.4. The Process of RNA Extraction

2.5. Analysis of Sequencing Data

2.6. Non-Targeted Metabolic Profiling of Ovary Samples

2.7. Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR) Validation

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Differences in Reproduction Performance and Overview of Transcriptomic Data

3.2. Identification and Functional Analysis of DEGs in the Ovary Between Two Pig Breeds

3.3. Identification and Functional Analysis of SDMs in the Ovary Between Two Pig Breeds

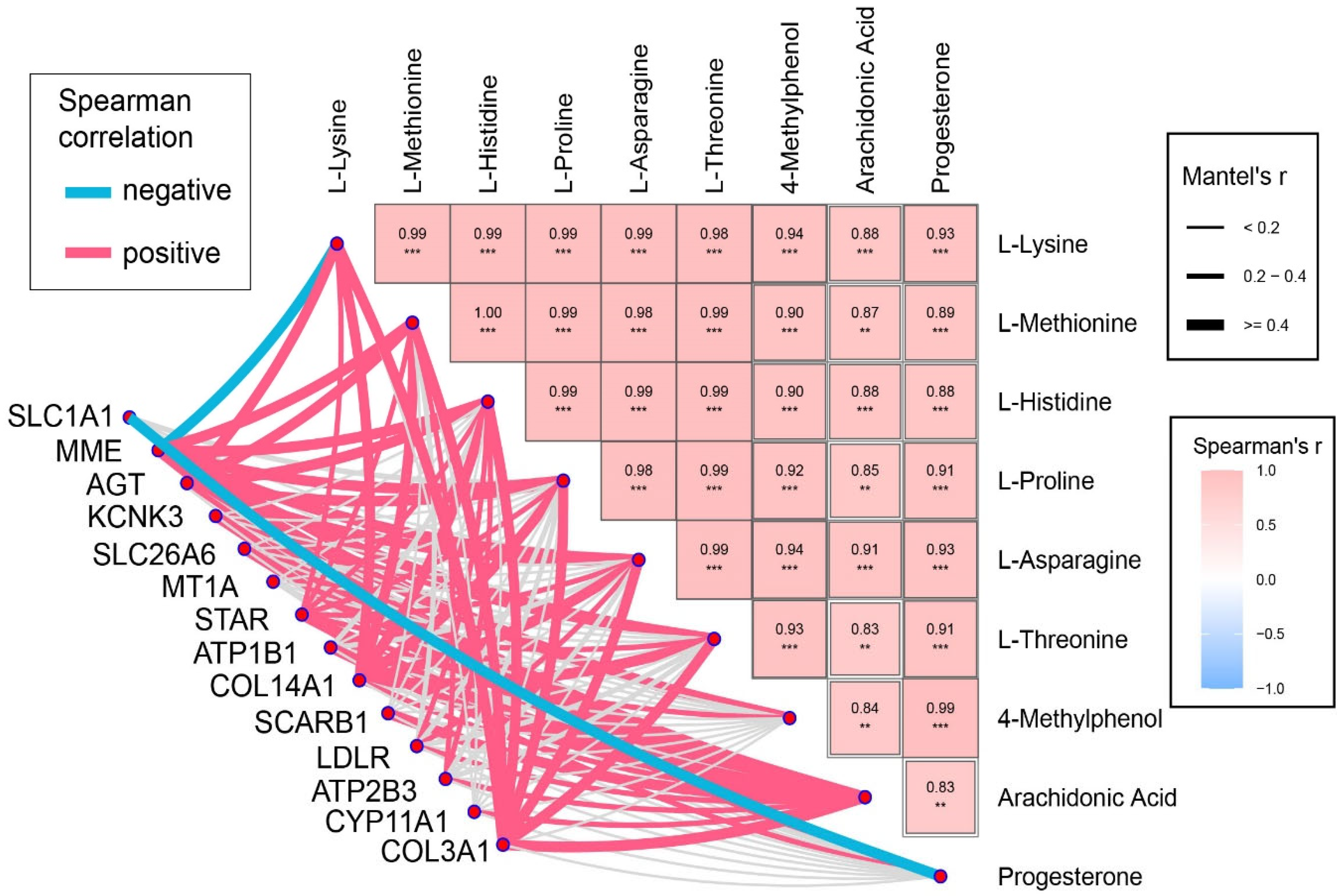

3.4. Correlation Analysis Between DEGs and SDMs Enriched in the Same Pathway

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wang, L.; Li, D. Invited Review—Current status, challenges and prospects for pig production in Asia. Anim. Biosci. 2024, 37, 742–754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Southwood, O.I.; Kennedy, B.W. Genetic and environmental trends for litter size in swine. J. Anim. Sci. 1991, 69, 3177–3182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buske, B.; Sternstein, I.; Brockmann, G. QTL and candidate genes for fecundity in sows. Anim. Reprod. Sci. 2006, 95, 167–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oktem, O.; Oktay, K. The ovary: Anatomy and function throughout human life. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2008, 1127, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, L.; Shen, W.; Zhang, J.; Ma, L.; Shen, W.; Shen, W.; Ma, L.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, J. The life cycle of the ovary. In Ovarian Aging; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp. 7–33. [Google Scholar]

- He, Y.; Gan, M.; Ma, J.; Liang, S.; Chen, L.; Niu, L.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Shen, L. TGF-beta signaling in the ovary: Emerging roles in development and disease. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 306, 141455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Z.C.; Wang, Y.; Huang, X.; Wu, S.; Bao, W. A genome-wide association study of important reproduction traits in large white pigs. Gene 2022, 838, 146702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, T.F.; Braga Magalhaes, A.F.; Verardo, L.L.; Santos, G.C.; Silva Fernandes, A.A.; Gomes Vieira, J.I.; Irano, N.; Dos Santos, D.B. Functional analysis of litter size and number of teats in pigs: From GWAS to post-GWAS. Theriogenology 2022, 193, 157–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Zhang, S.; Yuan, M.; Zhan, F.; Song, M.; Shang, P.; Yang, F.; Li, X.; Qiao, R.; Han, X.; et al. Genome-Wide Association Studies and Runs of Homozygosity to Identify Reproduction-Related Genes in Yorkshire Pig Population. Genes 2023, 14, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, Y.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Duan, M.; Zhao, M.; Zhang, F.; Chamba, Y.; Shang, P. Application of RNA-Seq Technology for Screening Reproduction-Related Differentially Expressed Genes in Tibetan and Yorkshire Pig Ovarian Tissue. Vet. Sci. 2024, 11, 283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, X.; Hu, F.; Mao, N.; Ruan, Y.; Yi, F.; Niu, X.; Huang, S.; Li, S.; You, L.; Zhang, F.; et al. Differences in gene expression and variable splicing events of ovaries between large and small litter size in Chinese Xiang pigs. Porc. Health Manag. 2021, 7, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, B.; Chai, J.; Fei, K.; Zheng, T.; Jiang, Y. Dynamic changes in the transcriptome and metabolome of pig ovaries across developmental stages and gestation. BMC Genom. 2024, 25, 1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Lian, Y.; Peng, P.; Yang, L.; Zhao, H.; Huang, P.; Ma, H.; Wei, H.; Yin, Y.; Liu, M. Association of gut microbiota and SCFAs with finishing weight of Diannan small ear pigs. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1117965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, W.; Yan, J.; Jamal, M.A.; Zhao, H.; Xu, K.; Jiao, D.; Lv, M.; Zhao, H.Y.; Wei, H.J. Biological characteristics of Banna miniature inbred pigs. Eur. Surg. Res. 2025, 66, 88–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alam, M.; Chang, H.K.; Lee, S.S.; Choi, T.J. Genetic Analysis of Major Production and Reproduction Traits of Korean Duroc, Landrace and Yorkshire Pigs. Animals 2021, 11, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qin, Y.; Tang, T.; Li, W.; Liu, Z.; Yang, X.; Shi, X.; Sun, G.; Liu, X.; Wang, M.; Liang, X.; et al. Bone Morphogenetic Protein 15 Knockdown Inhibits Porcine Ovarian Follicular Development and Ovulation. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2019, 7, 286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krueger, F.; James, F.; Ewels, P.; Afyounian, E.; Schuster-Boeckler, B.T. A wrapper around Cutadapt and FastQC to consistently apply adapter and quality trimming to FastQ files, with extra functionality for RRBS data. TrimGalore 2016. Available online: https://github.com/FelixKrueger/TrimGalore (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Chen, S.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, Y.; Gu, J. fastp: An ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 2018, 34, i884–i890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, D.; Paggi, J.M.; Park, C.; Bennett, C.; Salzberg, S.L. Graph-based genome alignment and genotyping with HISAT2 and HISAT-genotype. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 907–915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Smyth, G.K.; Shi, W. featureCounts: An efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 923–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Q.; Liufu, S.; Chen, B.; Wang, K.; Chen, W.; Xiao, L.; Liu, X.; Yi, L.; Liu, J.; Xu, X.; et al. Gut-resident Phascolarctobacterium succinatutens decreases fat accumulation via MYC-driven epigenetic regulation of arginine biosynthesis. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes 2025, 11, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liufu, S.; Wang, K.; Chen, B.; Chen, W.; Liu, X.; Wen, S.; Li, X.; Xu, D.; Ma, H. Effect of host breeds on gut microbiome and fecal metabolome in commercial pigs. BMC Vet. Res. 2024, 20, 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, F.; Moore, R.K.; Wang, X.; Sharma, S.; Miyoshi, T.; Shimasaki, S. Essential role of the oocyte in estrogen amplification of follicle-stimulating hormone signaling in granulosa cells. Endocrinology 2005, 146, 3362–3367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- le Nestour, E.; Marraoui, J.; Lahlou, N.; Roger, M.; de Ziegler, D.; Bouchard, P. Role of estradiol in the rise in follicle-stimulating hormone levels during the luteal-follicular transition. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1993, 77, 439–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garmey, J.C.; Guthrie, H.D.; Garrett, W.M.; Stoler, M.H.; Veldhuis, J.D. Localization and expression of low-density lipoprotein receptor, steroidogenic acute regulatory protein, cytochrome P450 side-chain cleavage and P450 17-alpha-hydroxylase/C17-20 lyase in developing swine follicles: In situ molecular hybridization and immunocytochemical studies. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2000, 170, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Garmey, J.C.; Veldhuis, J.D. Interactive stimulation by luteinizing hormone and insulin of the steroidogenic acute regulatory (StAR) protein and 17alpha-hydroxylase/17,20-lyase (CYP17) genes in porcine theca cells. Endocrinology 2000, 141, 2735–2742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Sun, Y.; Jiang, Y.; Qian, Y.; Chen, S.; Gao, S.; Chen, L.; Li, C.; Zhou, X. Follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) promotes retinol uptake and metabolism in the mouse ovary. Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 2018, 16, 52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaroufi, K.; Chekir, L.; Creppy, E.E.; Ellouz, F.; Bacha, H. Zearalenone induces modifications of haematological and biochemical parameters in rats. Toxicon 1996, 34, 535–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, J.; Chen, X.; Wang, H.; Mi, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, H. Porcine granulosa cell transcriptomic analyses reveal the differential regulation of lncRNAs and mRNAs in response to all-trans retinoic acid in vitro. Anim. Biosci. 2025, 38, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, T.; Yanaka, N.; Richards, J.S.; Shimada, M. De Novo-Synthesized Retinoic Acid in Ovarian Antral Follicles Enhances FSH-Mediated Ovarian Follicular Cell Differentiation and Female Fertility. Endocrinology 2016, 157, 2160–2172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, E.S.; Seo, J.S.; Eum, J.H.; Lim, J.E.; Kim, D.H.; Yoon, T.K.; Lee, D.R. The effect of folic acid on in vitro maturation and subsequent embryonic development of porcine immature oocytes. Mol. Reprod. Dev. 2009, 76, 120–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, D.; Sakurai, K.; Monji, Y.; Kuwayama, T.; Iwata, H. Supplementation of maturation medium with folic acid affects DNA methylation of porcine oocytes and histone acetylation of early developmental stage embryos. J. Mamm. Ova Res. 2013, 30, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, F.; Lan, J.; Xia, W.; Tu, C.; Chen, B.; Li, S.; Pan, W. Folic Acid Attenuates Vascular Endothelial Cell Injury Caused by Hypoxia via the Inhibition of ERK1/2/NOX4/ROS Pathway. Cell Biochem. Biophys. 2016, 74, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saini, S.; Sharma, V.; Ansari, S.; Kumar, A.; Thakur, A.; Malik, H.; Kumar, S.; Malakar, D. Folate supplementation during oocyte maturation positively impacts the folate-methionine metabolism in pre-implantation embryos. Theriogenology 2022, 182, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebisch, I.M.; Thomas, C.M.; Peters, W.H.; Braat, D.D.; Steegers-Theunissen, R.P. The importance of folate, zinc and antioxidants in the pathogenesis and prevention of subfertility. Hum. Reprod. Update 2007, 13, 163–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Y.; Song, J.; Cao, X.; Sun, Z. Mechanism of Guilu Erxian ointment based on targeted metabolomics in intervening in vitro fertilization and embryo transfer outcome in older patients with poor ovarian response of kidney-qi deficiency type. Front. Endocrinol. 2023, 14, 1045384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, N.; Vijayan, N.; Kumar, R.; Gupta, N. Overview on L-asparagine monohydrate single crystal: A non-essential amino acid. J. Nonlinear Opt. Phys. Mater. 2023, 32, 2330001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Shang, J.; Jia, X.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, J.; Huan, Y.; Tan, J.; Sun, M. Proline improves the developmental competence of in vitro matured porcine oocytes by enhancing mitochondrial function. Theriogenology 2025, 238, 117362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, K.-R.; Zhang, Q.; Jin, E.-H.; Hu, Q.-Q.; Gu, Y.-F.; Ren, M.; Li, S.-H. Effect of Threonine on the Proliferation and Viability of Porcine Granulosa Cells. Curr. Top. Nutraceutical Res. 2019, 17, 1. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, G.; Li, S.; Cai, S.; Zhou, J.; Ye, Q.; Zhang, S.; Chen, F.; Wang, F.; Zeng, X. Dietary methionine supplementation during the estrous cycle improves follicular development and estrogen synthesis in rats. Food Funct. 2024, 15, 704–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, N.; Wang, L.; Luo, G.; Tang, X.; Ma, L.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, S.; Price, C.A.; Jiang, Z. Arachidonic Acid Regulation of Intracellular Signaling Pathways and Target Gene Expression in Bovine Ovarian Granulosa Cells. Animals 2019, 9, 374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, Y.M.; Yanase, T.; Nishi, Y.; Tanaka, A.; Saito, M.; Jin, C.H.; Mukasa, C.; Okabe, T.; Nomura, M.; Goto, K.; et al. Saturated FFAs, palmitic acid and stearic acid, induce apoptosis in human granulosa cells. Endocrinology 2001, 142, 3590–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Luan, S.; Xiao, X.; Li, X.; Fang, P.; Shang, Q.; Chen, L.; Zeng, X.; et al. Overexpressed COL3A1 has prognostic value in human esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and promotes the aggressiveness of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma by activating the NF-kappaB pathway. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2022, 613, 193–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Lin, L.; Li, X.; Wen, R.; Zhang, X. Silencing of COL3A1 represses proliferation, migration, invasion, and immune escape of triple negative breast cancer cells via down-regulating PD-L1 expression. Cell Biol. Int. 2022, 46, 1959–1969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilic, A.; Sonar, S.S.; Yildirim, A.O.; Fehrenbach, H.; Nockher, W.A.; Renz, H. Nerve growth factor induces type III collagen production in chronic allergic airway inflammation. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2011, 128, 1058–1066.e4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shaikh, G.; Zhang, J.; Perez-Aso, M.; Mediero, A.; Cronstein, B. Adenosine A(2A) receptor promotes collagen type III synthesis via beta-catenin activation in human dermal fibroblasts. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 173, 3279–3291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, G.; Kong, Y.; Yang, G.; Kong, D.; Xu, Y.; He, J.; Xu, Z.; Bai, Y.; Fan, H.; He, Q.; et al. Lnc-GULP1-2:1 affects granulosa cell proliferation by regulating COL3A1 expression and localization. J. Ovarian Res. 2021, 14, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Liufu, S.; Ouyang, J.; Jiang, Y.; Xiao, L.; Chen, B.; Wang, K.; Chen, W.; Xu, X.; Liu, C.; Ma, H. Comparative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Ovaries from Two Pig Breeds with Contrasting Reproductive Phenotype. Agriculture 2025, 15, 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232471

Liufu S, Ouyang J, Jiang Y, Xiao L, Chen B, Wang K, Chen W, Xu X, Liu C, Ma H. Comparative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Ovaries from Two Pig Breeds with Contrasting Reproductive Phenotype. Agriculture. 2025; 15(23):2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232471

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiufu, Sui, Jun Ouyang, Yi Jiang, Lanlin Xiao, Bohe Chen, Kaiming Wang, Wenwu Chen, Xin Xu, Caihong Liu, and Haiming Ma. 2025. "Comparative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Ovaries from Two Pig Breeds with Contrasting Reproductive Phenotype" Agriculture 15, no. 23: 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232471

APA StyleLiufu, S., Ouyang, J., Jiang, Y., Xiao, L., Chen, B., Wang, K., Chen, W., Xu, X., Liu, C., & Ma, H. (2025). Comparative Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Profiling of Ovaries from Two Pig Breeds with Contrasting Reproductive Phenotype. Agriculture, 15(23), 2471. https://doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15232471