Comparison of Mid-Term Clinical and Radiologic Outcomes Between Measured Resection Technique and Gap Balanced Technique After Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Medial Stabilizing Technique for Severe Varus Knee: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

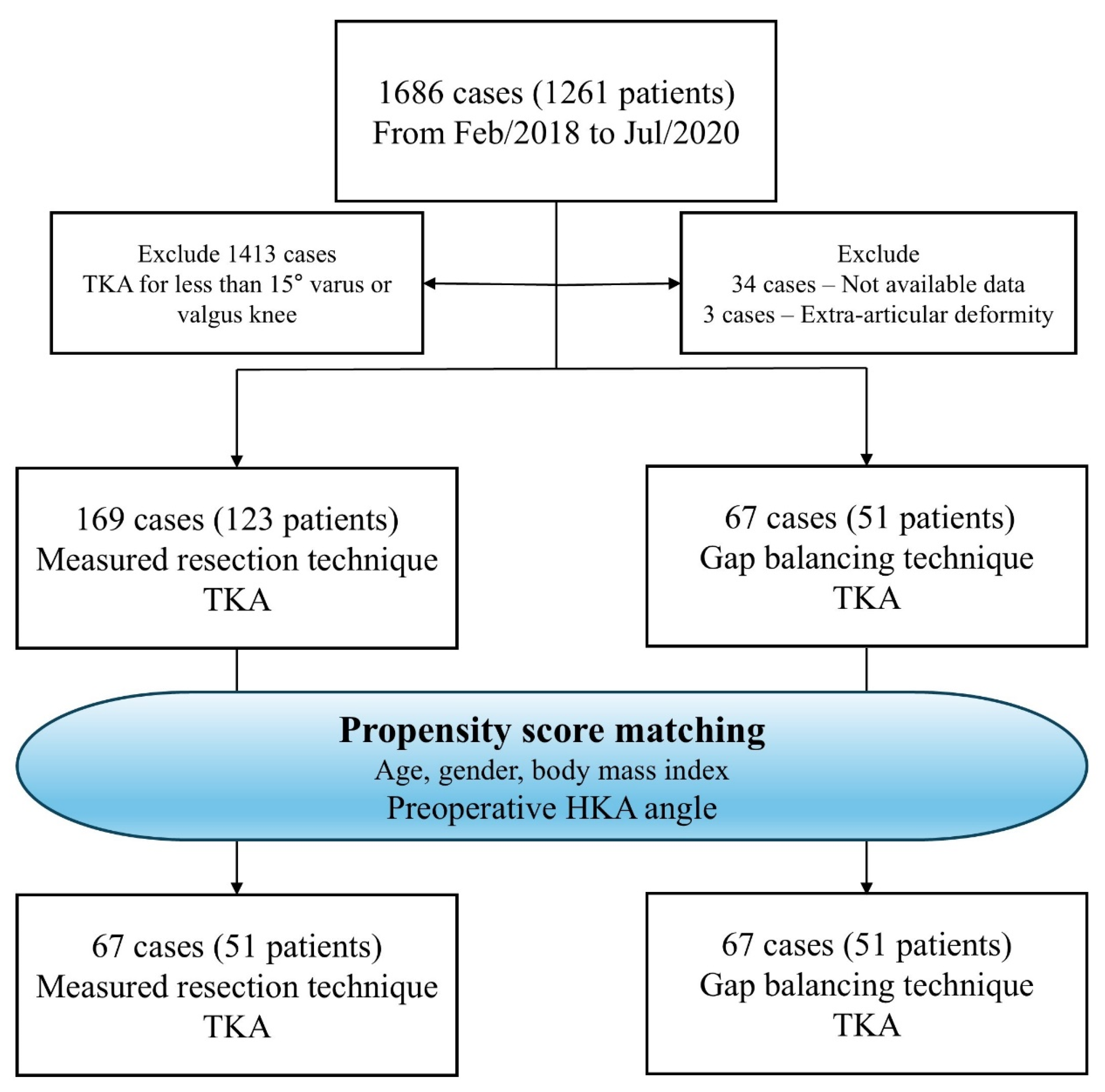

2.1. Study Design and Patients

2.2. Surgical Technique

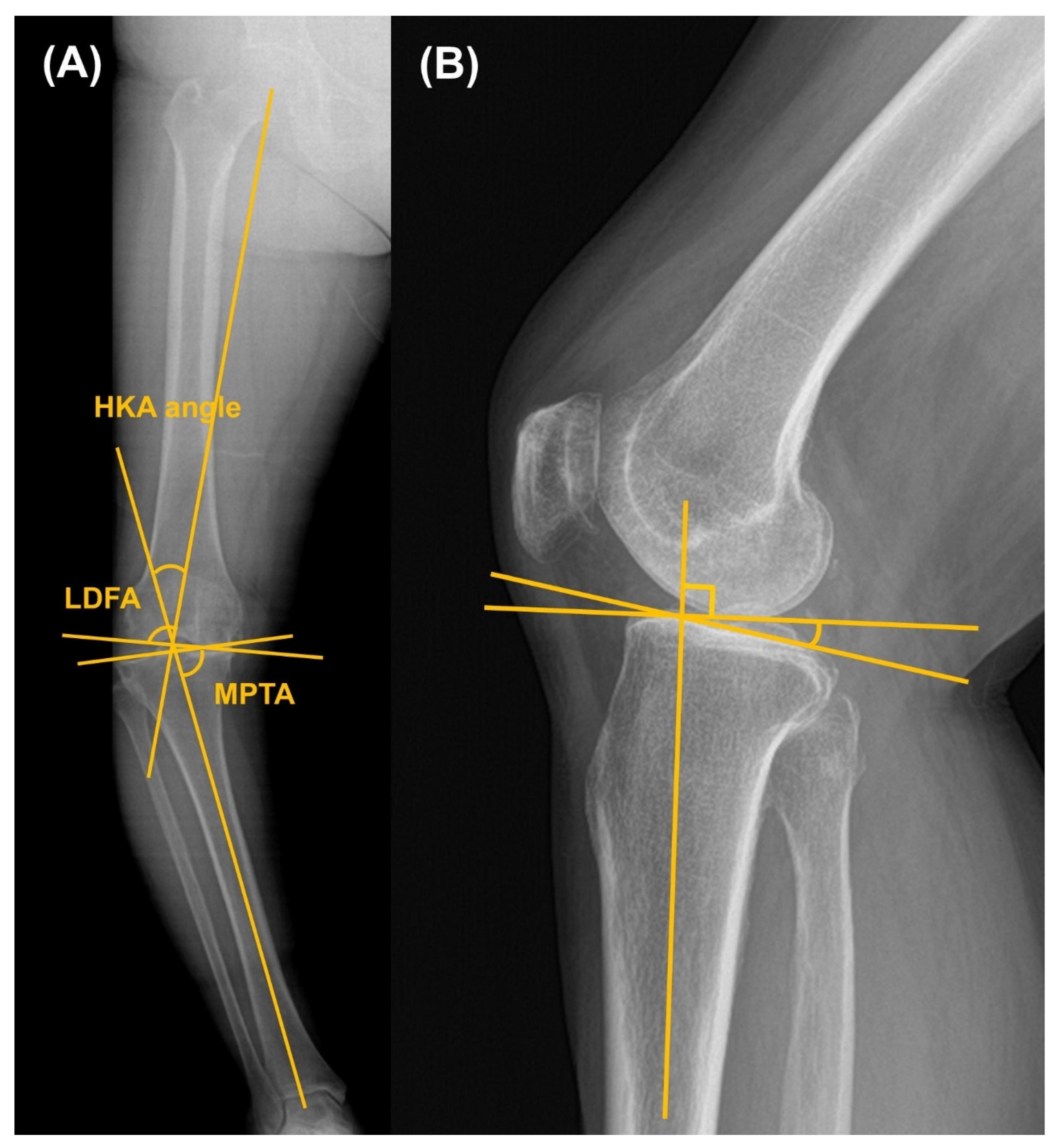

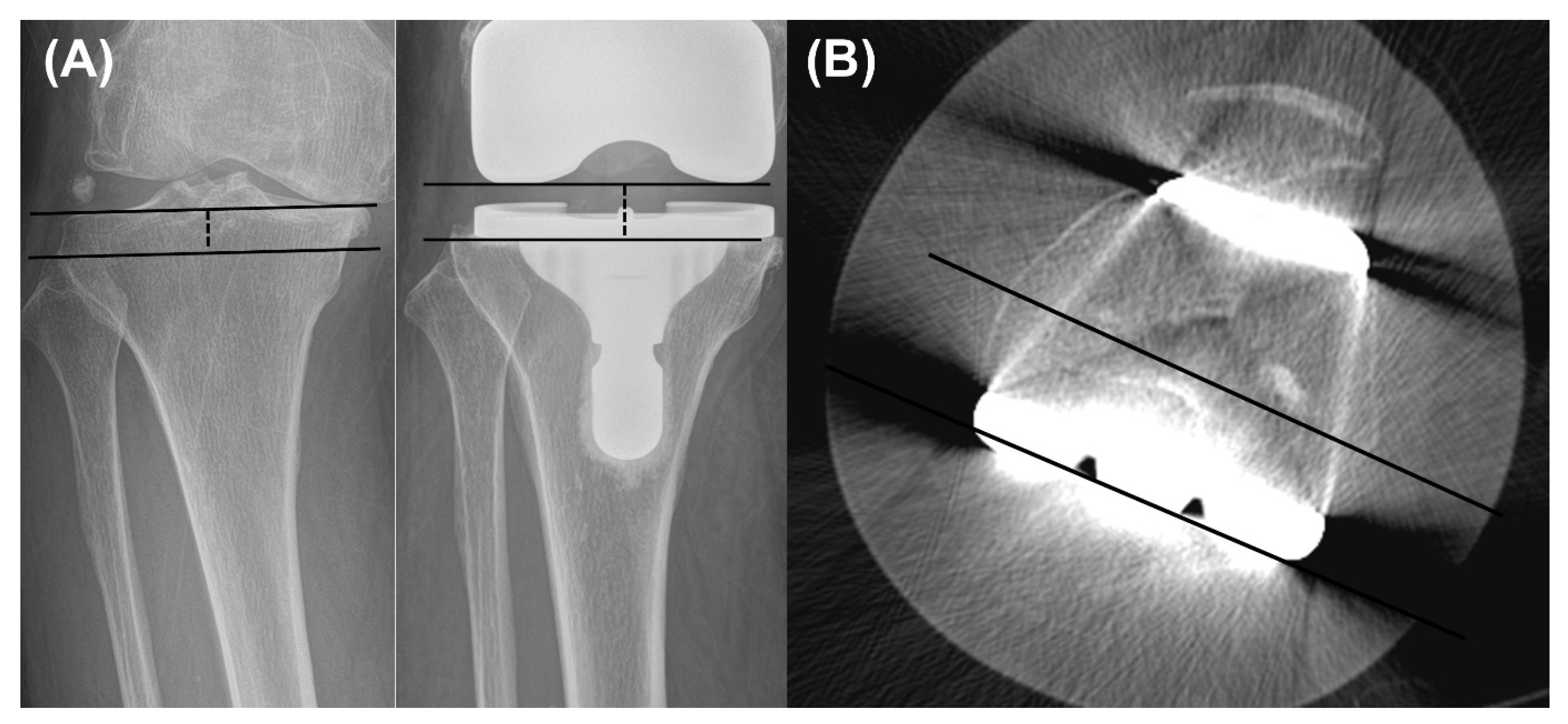

2.3. Clinical and Radiographic Assessments

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Kawata, M.; Sasabuchi, Y.; Inui, H.; Taketomi, S.; Matsui, H.; Fushimi, K.; Chikuda, H.; Yasunaga, H.; Tanaka, S. Annual trends in knee arthroplasty and tibial osteotomy: Analysis of a national database in Japan. Knee 2017, 24, 1198–1205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, T.W.; Kang, S.B.; Chang, C.B.; Moon, S.Y.; Lee, Y.K.; Koo, K.H. Current Trends and Projected Burden of Primary and Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty in Korea Between 2010 and 2030. J. Arthroplast. 2021, 36, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koh, I.J.; Kim, T.K.; Chang, C.B.; Cho, H.J.; In, Y. Trends in use of total knee arthroplasty in Korea from 2001 to 2010. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2013, 471, 1441–1450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckmann, N.D.; Mayfield, C.K.; Richardson, M.K.; Liu, K.C.; Wang, J.C.; Piple, A.S.; Stambough, J.B.; Oakes, D.A.; Christ, A.B.; Lieberman, J.R. An Updated Estimate of Total Hip and Total Knee Arthroplasty Inpatient Case Volume During the 2020 COVID-19 Pandemic in the United States. Arthroplast Today 2024, 26, 101336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moldovan, F.; Gligor, A.; Moldovan, L.; Bataga, T. An Investigation for Future Practice of Elective Hip and Knee Arthroplasties during COVID-19 in Romania. Medicina 2023, 59, 314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avci, O.; Ozturk, A.; Akalin, Y.; Cevik, N.; Cinar, A.; Sahin, H. Does the gap balance technique really elevate the joint line in total knee arthroplasty? A single-center, randomized study. Jt. Dis. Relat. Surg. 2025, 36, 350–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Migliorini, F.; Eschweiler, J.; Mansy, Y.E.; Quack, V.; Schenker, H.; Tingart, M.; Driessen, A. Gap balancing versus measured resection for primary total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis study. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2020, 140, 1245–1253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, T.; Long, Y.; George, D.; Wang, W. Meta-analysis of gap balancing versus measured resection techniques in total knee arthroplasty. Bone Jt. J. 2017, 99-B, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Luo, X.; Wang, P.; Sun, H.; Wang, K.; Sun, X. Clinical Outcomes of Gap Balancing vs Measured Resection in Total Knee Arthroplasty: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Involving 2259 Subjects. J. Arthroplast. 2018, 33, 2684–2693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Passaretti, A.; Colò, G.; Bulgheroni, A.; Vulcano, E.; Surace, M. Gonarthrosis and ACL lesion: An intraoperative analysis and correlations in patients who underwent total knee arthroplasty. Minerva Orthop. 2024, 75, 331–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, B.S.; Lee, S.J.; Kim, J.M.; Lee, D.H.; Cha, E.J.; Bin, S.I. No impact of severe varus deformity on clinical outcome after posterior stabilized total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2011, 19, 960–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueyama, H.; Kanemoto, N.; Minoda, Y.; Nakagawa, S.; Taniguchi, Y.; Nakamura, H. Association of a Wider Medial Gap (Medial Laxity) in Flexion with Self-Reported Knee Instability After Medial-Pivot Total Knee Arthroplasty. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Am. 2022, 104, 910–918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.W.; Martinez Martos, S.; Dai, Y.; Beller, E.M. The femoral intercondylar notch is an accurate landmark for the resection depth of the distal femur in total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2022, 34, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ishibashi, K.; Sasaki, E.; Sasaki, S.; Kimura, Y.; Yamamoto, Y.; Ishibashi, Y. Medial stabilizing technique preserves anatomical joint line and increases range of motion compared with the gap-balancing technique in navigated total knee arthroplasty. Knee 2020, 27, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okazaki, K.; Miura, H.; Matsuda, S.; Takeuchi, N.; Mawatari, T.; Hashizume, M.; Iwamoto, Y. Asymmetry of mediolateral laxity of the normal knee. J. Orthop. Sci. 2006, 11, 264–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsubosaka, M.; Muratsu, H.; Nakano, N.; Kamenaga, T.; Kuroda, Y.; Inokuchi, T.; Miya, H.; Kuroda, R.; Matsumoto, T. Knee Stability following Posterior-Stabilized Total Knee Arthroplasty: Comparison of Medial Preserving Gap Technique and Measured Resection Technique. J. Knee Surg. 2023, 36, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajasekaran, R.B.; Palanisami, D.R.; Natesan, R.; Rajasekaran, S. Minimal under-correction gives better outcomes following total knee arthroplasty in severe varus knees-myth or reality?-analysis of one hundred sixty two knees with varus greater than fifteen degrees. Int. Orthop. 2020, 44, 715–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.J.; Moon, J.Y.; Song, E.K.; Lim, H.A.; Seon, J.K. Minimum Two-year Results of Revision Total Knee Arthroplasty Following Infectious or Non-infectious Causes. Knee Surg. Relat. Res. 2012, 24, 227–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clement, N.D.; Bardgett, M.; Weir, D.; Holland, J.; Gerrand, C.; Deehan, D.J. What is the Minimum Clinically Important Difference for the WOMAC Index After TKA? Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2018, 476, 2005–2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, H.J.; Kim, S.H.; Park, Y.B. Selective medial release using multiple needle puncturing with a spacer block in situ for correcting severe varus deformity during total knee arthroplasty. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2020, 140, 1523–1531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gustke, K.A.; Simon, P. A Restricted Functional Balancing Technique for Total Knee Arthroplasty With a Varus Deformity: Does a Medial Soft-Tissue Release Result in a Worse Outcome? J. Arthroplast. 2024, 39, S212–S217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toyooka, S.; Masuda, H.; Nishihara, N.; Miyamoto, W.; Kobayashi, T.; Kawano, H.; Nakagawa, T. Assessing the Role of Minimal Medial Tissue Release during Navigation-Assisted Varus Total Knee Arthroplasty Based on the Degree of Preoperative Varus Deformity. J. Knee Surg. 2022, 35, 1236–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambianchi, F.; Giorgini, A.; Ensini, A.; Lombari, V.; Daffara, V.; Catani, F. Navigated, soft tissue-guided total knee arthroplasty restores the distal femoral joint line orientation in a modified mechanically aligned technique. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 966–974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zambianchi, F.; Bazzan, G.; Marcovigi, A.; Pavesi, M.; Illuminati, A.; Ensini, A.; Catani, F. Joint line is restored in robotic-arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty performed with a tibia-based functional alignment. Arch. Orthop. Trauma Surg. 2021, 141, 2175–2184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sekiya, H.; Takatoku, K.; Takada, H.; Sasanuma, H.; Sugimoto, N. Postoperative lateral ligamentous laxity diminishes with time after TKA in the varus knee. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2009, 467, 1582–1586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moorthy, V.; Lai, M.C.; Liow, M.H.L.; Chen, J.Y.; Pang, H.N.; Chia, S.L.; Lo, N.N.; Yeo, S.J. Similar postoperative outcomes after total knee arthroplasty with measured resection and gap balancing techniques using a contemporary knee system: A randomized controlled trial. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2021, 29, 3178–3185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, C.W.; Lee, C.R.; Gwak, H.C.; Kim, J.H.; Kwon, Y.U.; Kim, D.Y. The Effects of Surgical Technique in Total Knee Arthroplasty for Varus Osteoarthritic Knee on the Rotational Alignment of Femoral Component: Gap Balancing Technique versus Measured Resection Technique. J. Knee Surg. 2020, 33, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kessler, O.; Patil, S.; Colwell, C.W., Jr.; D’Lima, D.D. The effect of femoral component malrotation on patellar biomechanics. J. Biomech. 2008, 41, 3332–3339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattee, G.; Moonot, P.; Govindaswamy, R.; Pope, A.; Fiddian, N.; Harvey, A. Does malrotation of components correlate with patient dissatisfaction following secondary patellar resurfacing? Knee 2014, 21, 247–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boldt, J.G.; Stiehl, J.B.; Hodler, J.; Zanetti, M.; Munzinger, U. Femoral component rotation and arthrofibrosis following mobile-bearing total knee arthroplasty. Int. Orthop. 2006, 30, 420–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, L.; Liu, Y.; He, J.; Lian, Q.; Li, D.; Jin, Z. Effect of component mal-rotation on knee loading in total knee arthroplasty using multi-body dynamics modeling under a simulated walking gait. J. Orthop. Res. 2015, 33, 1287–1296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanbiervliet, J.; Bellemans, J.; Verlinden, C.; Luyckx, J.P.; Labey, L.; Innocenti, B.; Vandenneucker, H. The influence of malrotation and femoral component material on patellofemoral wear during gait. J. Bone Jt. Surg. Br. 2011, 93, 1348–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker, R.; Baker, K.; Hommel, H.; Bernard, M.; Kopf, S. No correlation between rotation of femoral components in the transverse plane and clinical outcome after total knee arthroplasty. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2019, 27, 1456–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, L.; Thorwachter, C.; Steinbruck, A.; Jansson, V.; Traxler, H.; Alic, Z.; Holzapfel, B.M.; Woiczinski, M. Does Posterior Tibial Slope Influence Knee Kinematics in Medial Stabilized TKA? J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedopil, A.J.; Delman, C.; Howell, S.M.; Hull, M.L. Restoring the Patient’s Pre-Arthritic Posterior Slope Is the Correct Target for Maximizing Internal Tibial Rotation When Implanting a PCL Retaining TKA with Calipered Kinematic Alignment. J. Pers. Med. 2021, 11, 516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, W.; Jiang, Y.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, H.; Wang, Y.; Li, T. The influence of posterior tibial slope on the mid-term clinical effect of medial-pivot knee prosthesis. J. Orthop. Surg. Res. 2021, 16, 563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhamdi, H.; Deroche, E.; Shatrov, J.; Batailler, C.; Lustig, S.; Servien, E. Does the change between the native and the prosthetic posterior tibial slope influence the clinical outcomes after posterior stabilized TKA? A review of 793 knees at a minimum of 5 years follow-up. SICOT J. 2025, 11, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Group M | Group G | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Before propensity score match | |||

| Number of patients | 169 | 67 | |

| Age, year | 70.6 ± 6.6 | 71.9 ± 6.3 | 0.591 |

| Sex, male:female | 17:152 | 0:67 | 0.009 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 28.0 ± 3.9 | 27.8 ± 4.0 | 0.71 |

| HKA angle, ° | 17.0 ± 2.8 | 18.1 ± 3.9 | 0.007 |

| After propensity score match | |||

| Number of patients | 67 | 67 | |

| Age, year | 70.2 ± 6.0 | 71.1 ± 6.3 | 0.346 |

| Sex, male:female | 0:67 | 0:67 | 1 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 27.6 ± 3.9 | 27.8 ± 4.0 | 0.702 |

| Follow up period, months | 76.2 ± 10.4 | 72.0 ± 11.3 | 0.029 |

| Range of motion, ° | 124.3 ± 22.0 | 127.4 ± 25.0 | 0.221 |

| WOMAC index | 58.0 ± 15.8 | 58.0 ± 15.5 | 0.988 |

| KSKS | 52.4 ± 7.7 | 53.2 ± 7.5 | 0.542 |

| KSFS | 46.5 ± 12.3 | 43.2 ± 10.9 | 0.102 |

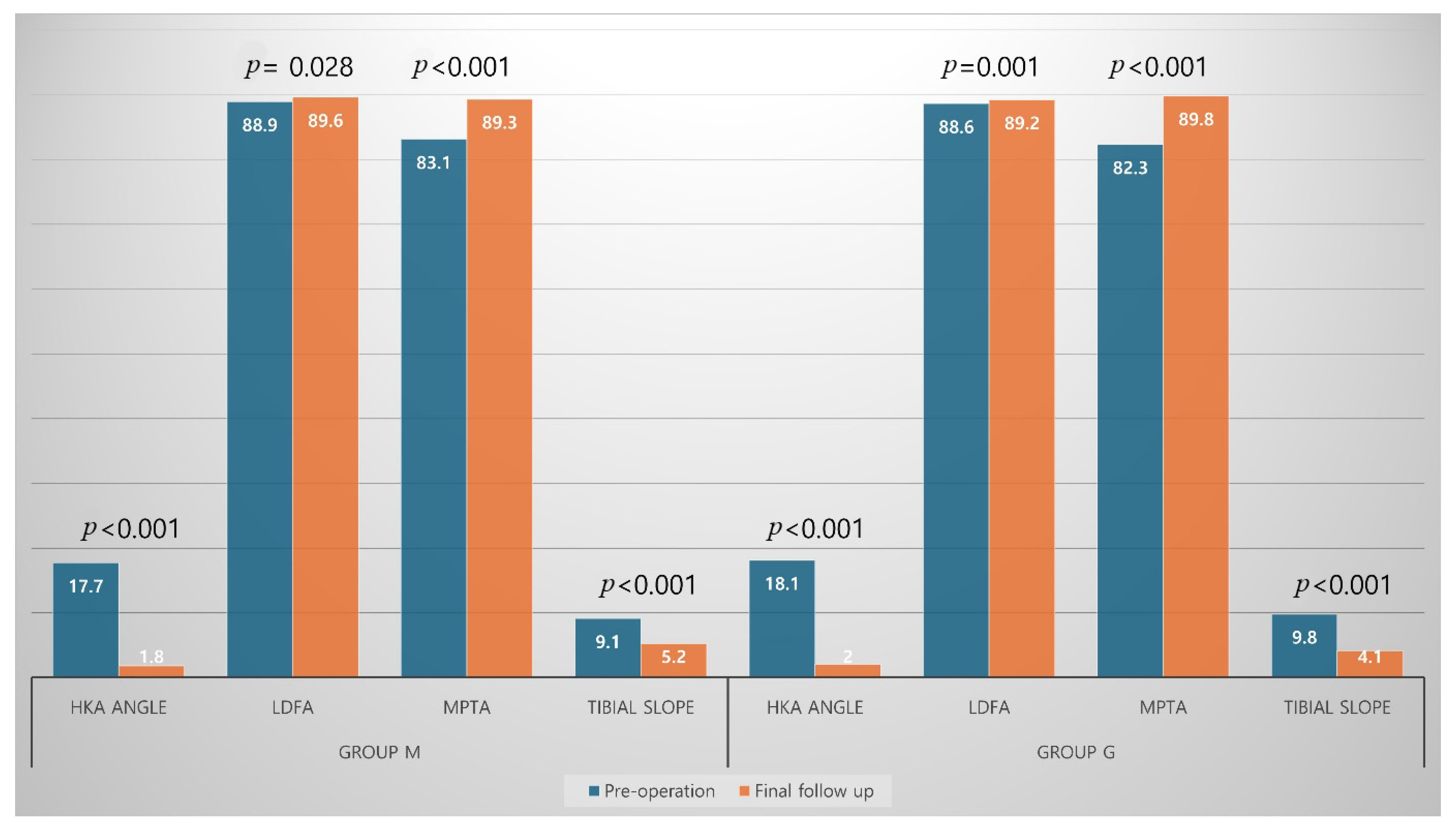

| HKA angle, ° | 17.7 ± 2.9 | 18.1 ± 3.9 | 0.465 |

| LDFA, ° | 88.9 ± 2.5 | 88.6 ± 2.4 | 0.477 |

| MPTA, ° | 83.1 ± 2.8 | 82.3 ± 3.2 | 0.148 |

| Tibial slope, ° | 9.1 ± 3.4 | 9.8 ± 3.2 | 0.176 |

| Joint line distance, mm | 17.6 ± 3.2 | 17.7 ± 3.5 | 0.909 |

| Group M | Group G | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

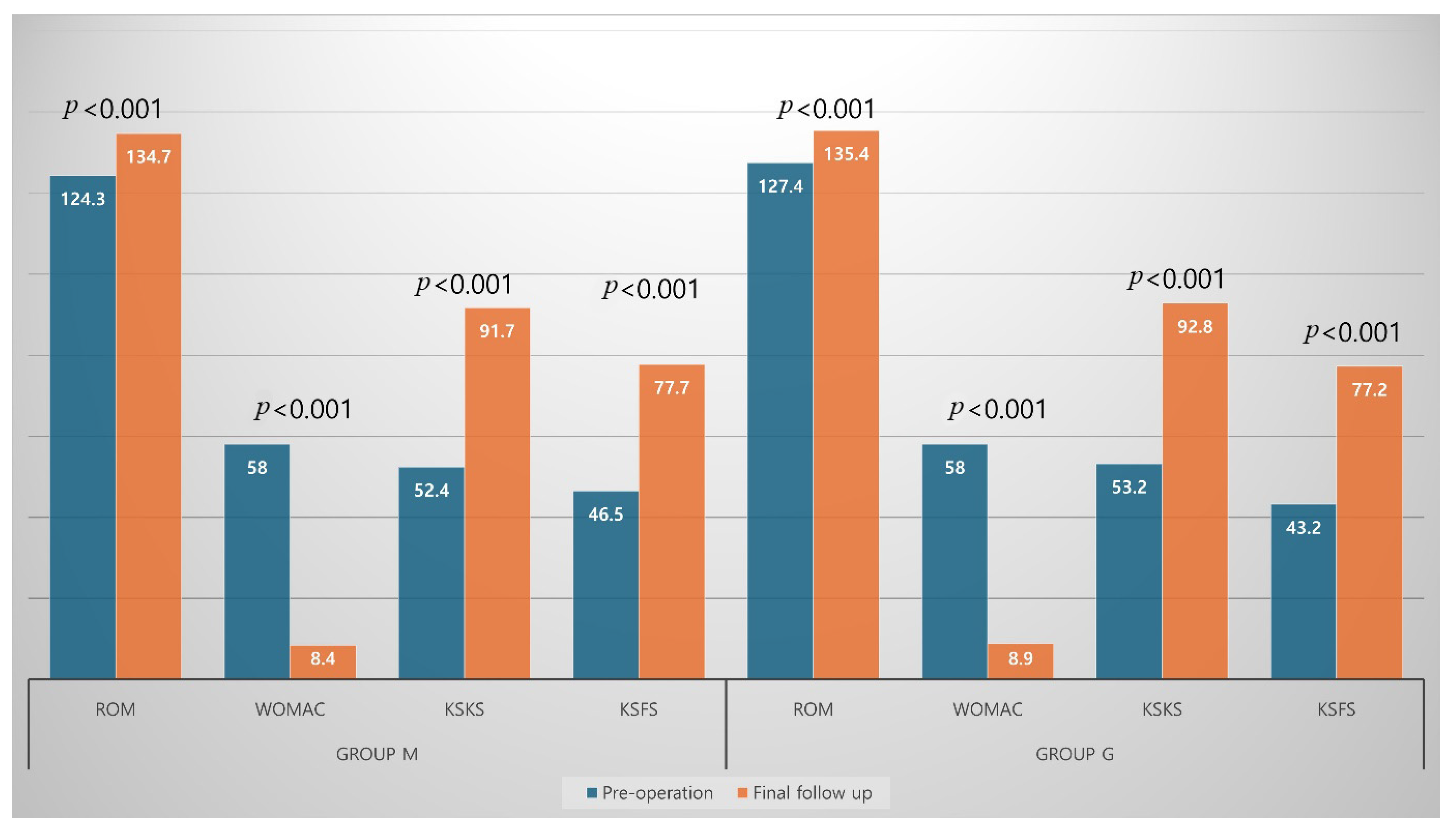

| Range of motion, ° | 134.7 ± 17.0 | 135.4 ± 19.4 | 0.415 |

| WOMAC index | 8.4 ± 5.1 | 8.9 ± 5.1 | 0.28 |

| KSKS | 91.7 ± 6.2 | 92.8 ± 6.5 | 0.155 |

| KSFS | 77.7 ± 16.7 | 77.2 ± 17.8 | 0.434 |

| HKA angle, ° | 1.8 ± 2.6 | 2.0 ± 2.9 | 0.701 |

| LDFA, ° | 89.6 ± 1.7 | 89.2 ± 1.3 | 0.501 |

| MPTA, ° | 89.3 ± 1.8 | 89.8 ± 1.6 | 0.063 |

| Tibial slope, ° | 5.2 ± 2.3 | 4.1 ± 2.3 | 0.006 |

| Joint line distance, mm | 18.1 ± 3.8 | 18.0 ± 3.9 | 0.802 |

| Femoral component rotation angle, ° | 1.6 ± 2.1 | 2.1 ± 2.0 | 0.134 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lee, S.-S.; Oh, J.; Moon, Y.-W. Comparison of Mid-Term Clinical and Radiologic Outcomes Between Measured Resection Technique and Gap Balanced Technique After Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Medial Stabilizing Technique for Severe Varus Knee: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238450

Lee S-S, Oh J, Moon Y-W. Comparison of Mid-Term Clinical and Radiologic Outcomes Between Measured Resection Technique and Gap Balanced Technique After Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Medial Stabilizing Technique for Severe Varus Knee: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238450

Chicago/Turabian StyleLee, Sung-Sahn, Juyong Oh, and Young-Wan Moon. 2025. "Comparison of Mid-Term Clinical and Radiologic Outcomes Between Measured Resection Technique and Gap Balanced Technique After Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Medial Stabilizing Technique for Severe Varus Knee: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238450

APA StyleLee, S.-S., Oh, J., & Moon, Y.-W. (2025). Comparison of Mid-Term Clinical and Radiologic Outcomes Between Measured Resection Technique and Gap Balanced Technique After Total Knee Arthroplasty Using Medial Stabilizing Technique for Severe Varus Knee: A Propensity Score-Matched Analysis. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8450. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238450