Mental Health Trajectories in Medical Students: The Impact of Academic Repetition on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Methods

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Study Design

2.3. Data Collection

- 1.

- Demographic data: Items included age, gender, and the year in which participants’ medical studies were initiated. The mean age of respondents increased from 19.5 to 23.3 years over the four-year study period. Female students consistently comprised the majority, ranging from 58.7% to 60.4%. The proportion of students following the standard curriculum (i.e., the original-entry cohort) declined steadily from 100% in the first year to 56% by the fourth year (Table 1).

- 2.

- Health-related lifestyle factors:

- Living arrangements: “Who do you live with during the academic term?” with options including alone, with parents, in a dormitory with others, in a shared rented apartment, or other.

- Financial situation: “How would you rate your financial situation?” (very good, good, adequate, poor, very poor). For analysis, the categories very good, good, and adequate were grouped separately from the poor and very poor categories.

- Physical activity: “In an average week, how many times do you engage in physical activity (sports or physical work) lasting more than 20 min, during which your breathing and heart rate increase?” (never, 1–2 times, 3–4 times, ≥5 times), based on Craig et al. (2003) [30]. For analysis, the response options ‘never’ and ‘1–2 times per week’ were combined to form a single category.

- 3.

- 4.

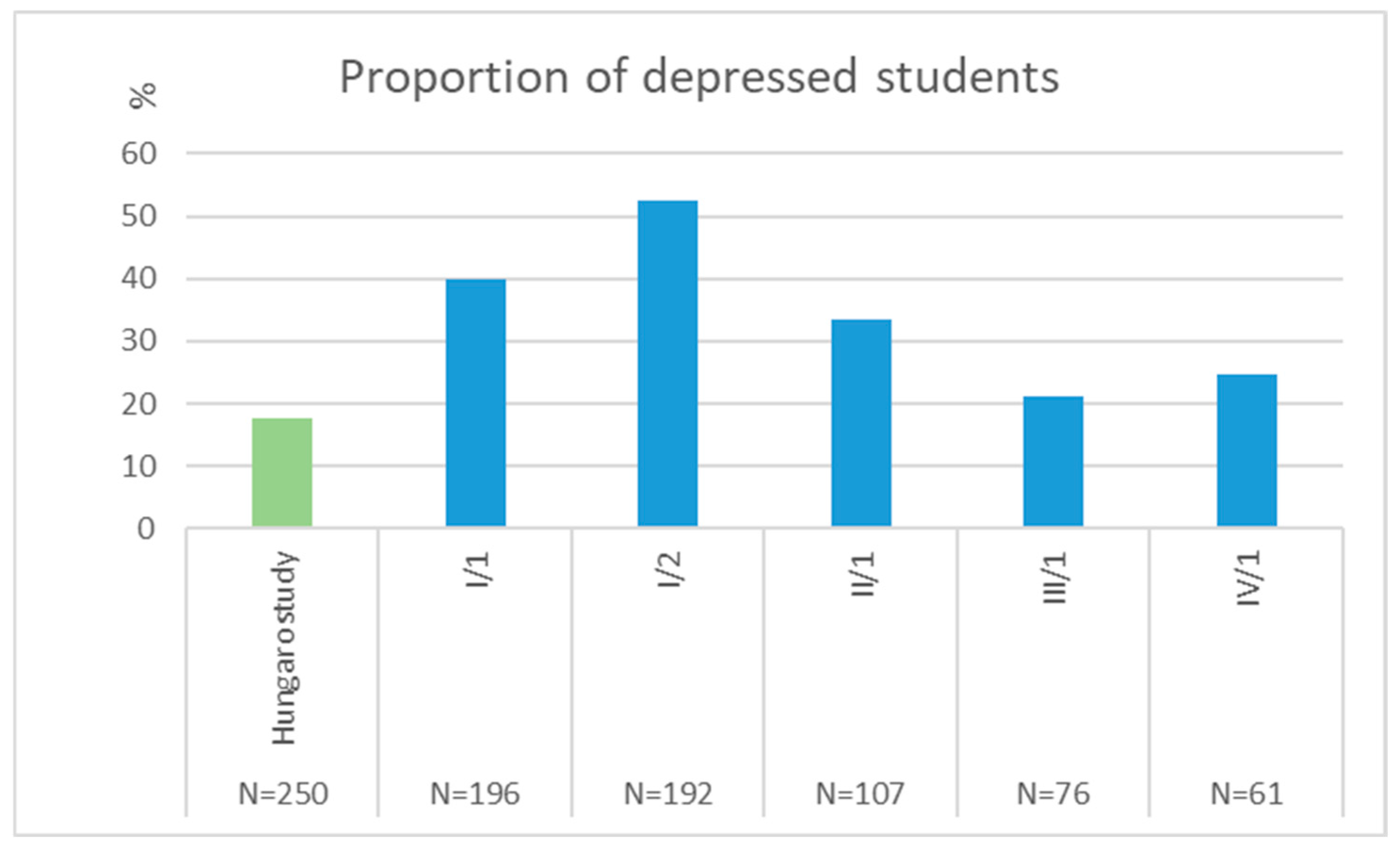

- Depressive symptoms: Measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI; Beck et al., 1988 [32]; Hungarian version: Perczel-Forintos, 2012 [33]), which assesses symptoms over the past week on a 0–3 scale. Total scores were categorized as minimal (0–9), mild (10–18), moderate (19–29), or severe (30–63). Scores ≥10 were considered indicative of clinically relevant depressive symptoms. As a reference population, data from the Hungarostudy 2013 survey were used (Susánszky & Székely, 2013), selecting a subsample matched by age group [33,34]. In our study, the BDI exhibited good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s α values of 0.769 in Wave 1, 0.818 in Wave 2, 0.880 in Wave 3, 0.905 in Wave 4, and 0.924 in Wave 5.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

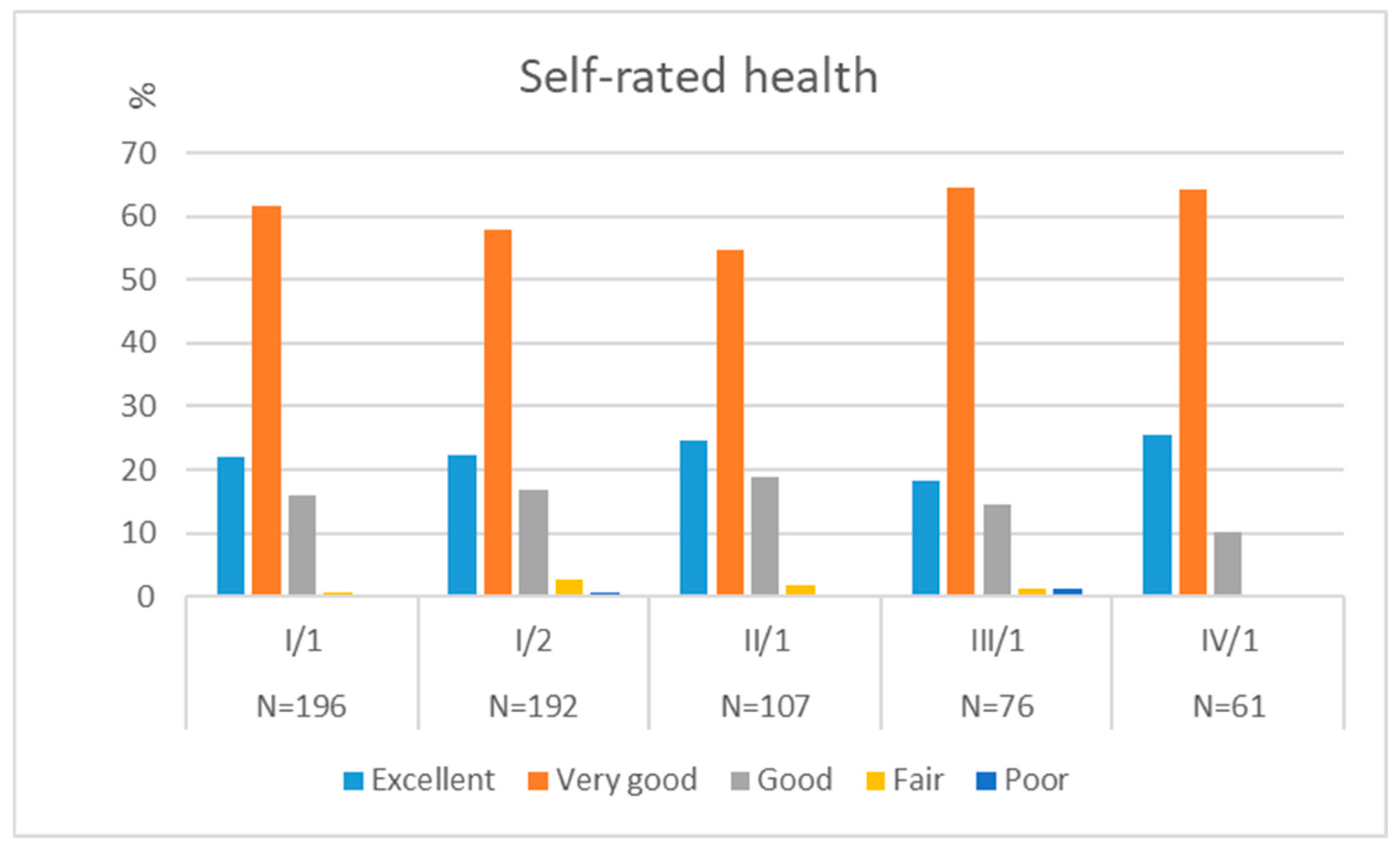

3.1. Temporal Changes of Health-Related Lifestyle Factors and Self-Rated Health in the Original-Entry Cohort

3.2. Temporal Changes in the BDI Results in the Original-Entry Cohort

3.3. Factors Influencing Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health in the Original-Entry Cohort

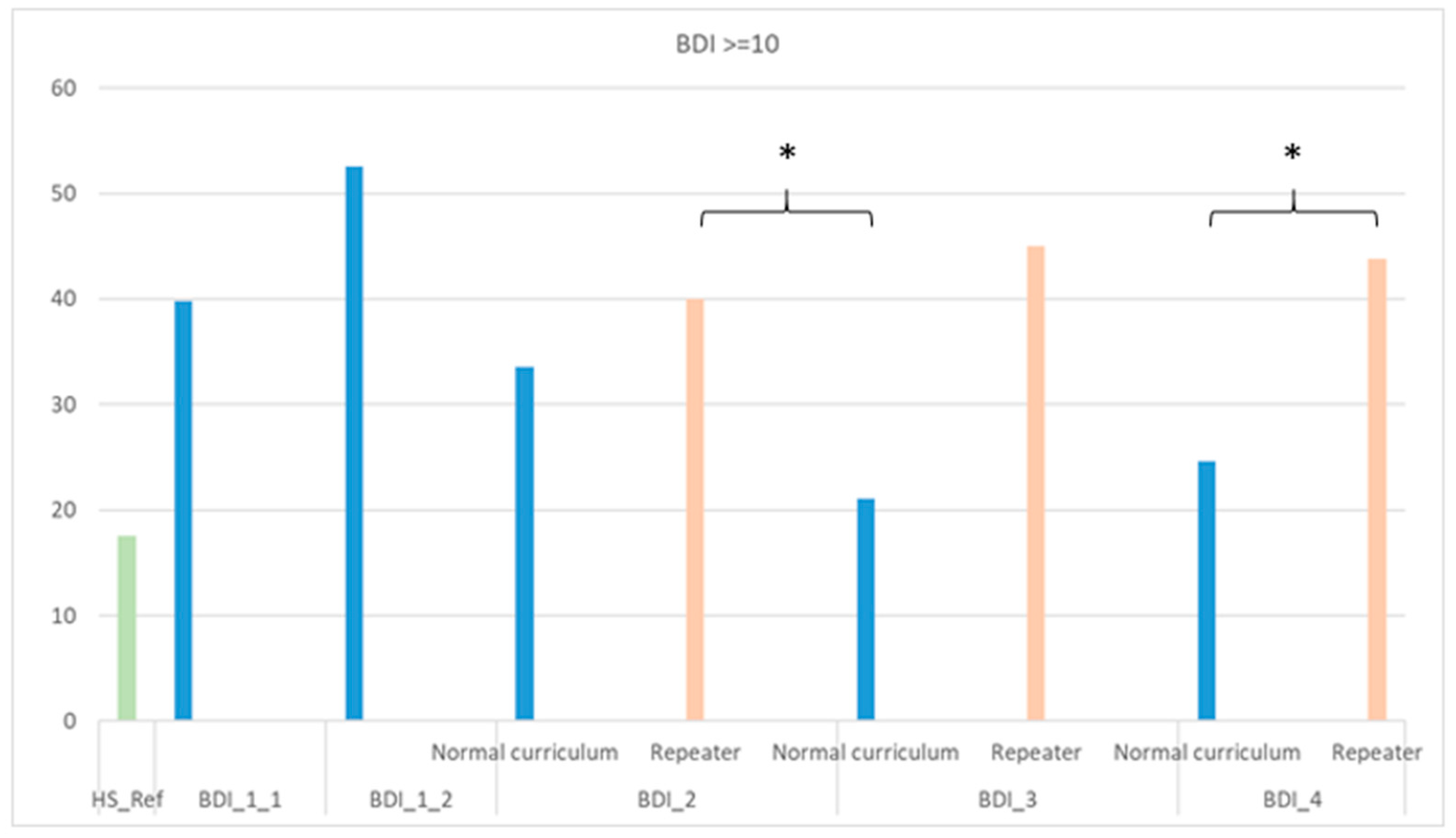

3.4. Effect of Year Repetition on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health Among Repeater Students

4. Discussion

- Implications

- Limitations

- Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| BDI | Beck Depression Inventory |

| CI | 95% Confidence Interval |

| EHIS | European Health Interview Survey |

| GHQ | General Health Questionnaire |

| OR | Odds Ratio |

| SRH | Self-Rated Health |

References

- Dyrbye, L.N.; Thomas, M.R.; Shanafelt, T.D. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad. Med. 2006, 81, 354–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, E.A.; Black, D.; Shaw, C.M.; Hamilton, J.; Creed, F.H.; Tomenson, B. Embarking upon a medical career: Psychological morbidity in first year medical students. Med. Educ. 1995, 29, 337–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosal, M.C.; Ockene, I.S.; Ockene, J.K.; Barrett, S.V.; Ma, Y.; Hebert, J.R. A longitudinal study of students’ depression at one medical school. Acad. Med. 1997, 72, 542–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyssen, R.; Vaglum, P.; Grønvold, N.T.; Ekeberg, O. Suicidal ideation among medical students and young physicians: A nationwide and prospective study of prevalence and predictors. J. Affect. Disord. 2001, 64, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Palička, M.; Rybář, M.; Mechúrová, B.; Paličková, N.; Sobelová, T.; Pokorná, K.; Cvek, J. The influence of excessive stress on medical students in the Czech Republic-national sample. BMC Med. Educ. 2023, 23, 168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherry, S.; Notman, M.T.; Nadelson, C.C.; Kanter, F.; Salt, P. Anxiety, depression, and menstrual symptoms among freshman medical students. J. Clin. Psychiatry 1988, 49, 490–493. [Google Scholar]

- Zoccolillo, M.; Murphy, G.E.; Wetzel, R.D. Depression among medical students. J. Affect. Disord. 1986, 11, 91–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moffat, K.J.; McConnachie, A.; Ross, S.; Morrison, J.M. First year medical student stress and coping in a problem-based learning medical curriculum. Med. Educ. 2004, 38, 482–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aktekin, M.; Karaman, T.; Senol, Y.Y.; Erdem, S.; Erengin, H.; Akaydin, M. Anxiety, depression and stressful life events among medical students: A prospective study in Antalya, Turkey. Med. Educ. 2001, 35, 12–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guthrie, E.; Black, D.; Bagalkote, H.; Shaw, C.; Campbell, M.; Creed, F. Psychological stress and burnout in medical students: A five-year prospective longitudinal study. J. R. Soc. Med. 1998, 91, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pokhrel, N.B.; Khadayat, R.; Tulachan, P. Depression, anxiety, and burnout among medical students and residents of a medical school in Nepal: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rotenstein, L.S.; Ramos, M.A.; Torre, M.; Segal, J.B.; Peluso, M.J.; Guille, C.; Sen, S.; Mata, D.A. Prevalence of Depression, Depressive Symptoms, and Suicidal Ideation Among Medical Students: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. JAMA 2016, 316, 2214–2236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puthran, R.; Zhang, M.W.; Tam, W.W.; Ho, R.C. Prevalence of depression amongst medical students: A meta-analysis. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 456–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bíró, E.; Balajti, I.; Adány, R.; Kósa, K. Determinants of mental well-being in medical students. Soc. Psychiatry Psychiatr. Epidemiol. 2010, 45, 253–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terebessy, A.; Czeglédi, E.; Balla, B.C.; Horváth, F.; Balázs, P. Medical students’ health behaviour and self-reported mental health status by their country of origin: A cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry 2016, 16, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molodynski, A.; Lewis, T.; Kadhum, M.; Farrell, S.M.; Lemtiri Chelieh, M.; Falcão De Almeida, T.; Masri, R.; Kar, A.; Volpe, U.; Moir, F.; et al. Cultural variations in wellbeing, burnout and substance use amongst medical students in twelve countries. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2021, 33, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hashim, S.B.; Huang, D.; Zhang, B. The effect of physical exercise on depression among college students: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PeerJ 2024, 12, e18111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Firth, J.; Rosenbaum, S.; Ward, P.B.; Silva, E.S.; Hallgren, M.; De Leon, A.P.; Dunn, A.L.; Deslandes, A.C.; et al. Physical Activity and Incident Depression: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies. Am. J. Psychiatry 2018, 175, 631–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pisaniello, M.S.; Asahina, A.T.; Bacchi, S.; Wagner, M.; Perry, S.W.; Wong, M.L.; Licinio, J. Effect of medical student debt on mental health, academic performance and specialty choice: A systematic review. BMJ Open 2019, 9, e029980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umami, A.; Zsiros, V.; Maróti-Nagy, Á.; Máté, Z.; Sudalhar, S.; Molnár, R.; Paulik, E. Healthcare-seeking of medical students: The effect of socio-demographic factors, health behaviour and health status-a cross-sectional study in Hungary. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medisauskaite, A.; Silkens, M.; Lagisetty, N.; Rich, A. UK medical students’ mental health and their intention to drop out: A longitudinal study. BMJ Open 2025, 15, e094058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silva, V.; Costa, P.; Pereira, I.; Faria, R.; Salgueira, A.P.; Costa, M.J.; Sousa, N.; Cerqueira, J.J.; Morgado, P. Depression in medical students: Insights from a longitudinal study. BMC Med. Educ. 2017, 17, 184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vankar, J.R.; Prabhakaran, A.; Sharma, H. Depression and stigma in medical students at a private medical college. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2014, 36, 246–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Östberg, D.; Nordin, S. Three-year prediction of depression and anxiety with a single self-rated health item. J. Ment. Health 2022, 31, 402–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambresin, G.; Chondros, P.; Dowrick, C.; Herrman, H.; Gunn, J.M. Self-rated health and long-term prognosis of depression. Ann. Fam. Med. 2014, 12, 57–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ishida, M.; Montagni, I.; Matsuzaki, K.; Shimamoto, T.; Cariou, T.; Kawamura, T.; Tzourio, C.; Iwami, T. The association between depressive symptoms and self-rated health among university students: A cross-sectional study in France and Japan. BMC Psychiatry 2020, 20, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seweryn, M.; Tyrała, K.; Kolarczyk-Haczyk, A.; Bonk, M.; Bulska, W.; Krysta, K. Evaluation of the level of depression among medical students from Poland, Portugal and Germany. Psychiatr. Danub. 2015, 27 (Suppl. S1), S216–S222. [Google Scholar]

- Sheldon, E.; Simmonds-Buckley, M.; Bone, C.; Mascarenhas, T.; Chan, N.; Wincott, M.; Gleeson, H.; Sow, K.; Hind, D.; Barkham, M. Prevalence and risk factors for mental health problems in university undergraduate students: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 287, 282–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schulte-Körne, G. Mental Health Problems in a School Setting in Children and Adolescents. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2016, 113, 183–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, C.L.; Marshall, A.L.; Sjöström, M.; Bauman, A.E.; Booth, M.L.; Ainsworth, B.E.; Pratt, M.; Ekelund, U.L.; Yngve, A.; Sallis, J.F.; et al. International physical activity questionnaire: 12-country reliability and validity. Med. Sci. Sports Exerc. 2003, 35, 1381–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjeldsberg, M.; Tschudi-Madsen, H.; Bruusgaard, D.; Natvig, B. Factors related to self-rated health: A survey among patients and their general practitioners. Scand. J. Prim. Health Care 2022, 40, 320–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Carbin, M.G. Psychometric properties of the Beck Depression Inventory: Twenty-five years of evaluation. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 1988, 8, 77–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perczel-Forintos, D. Kérdőívek, Becslőskálák a Klinikai Pszichológiában; Semmelweis Kiadó: Budapest, Hungary, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Susánszky, É.; Szántó, Z. A Hungarostudy 2013 felmérés módszertana. In Magyar Lelkiállapot 2013; Semmelweis Kiadó és Multimédia Stúdió: Budapest, Hungary, 2013; pp. 3–21. [Google Scholar]

- Hivatal, K.S. Európai Lakossági Egészségfelmérés, 2014: Központi Statisztikai Hivatal. 2015. Available online: https://www.ksh.hu/apps/shop.kiadvany?p_kiadvany_id=79467&p_lang=HU (accessed on 19 May 2025).

- Castaldelli-Maia, J.M.; Martins, S.S.; Bhugra, D.; Machado, M.P.; Andrade, A.G.; Alexandrino-Silva, C.; Baldassin, S.; Alves, T.C.d.T.F. Does ragging play a role in medical student depression-cause or effect? J. Affect. Disord. 2012, 139, 291–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roh, M.S.; Jeon, H.J.; Kim, H.; Cho, H.J.; Han, S.K.; Hahm, B.J. Factors influencing treatment for depression among medical students: A nationwide sample in South Korea. Med. Educ. 2009, 43, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shean, G.; Baldwin, G. Sensitivity and specificity of depression questionnaires in a college-age sample. J. Genet. Psychol. 2008, 169, 281–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rózsa, S.; Szádóczky, E.; Füredi, J. A Beck depresszió kérdőív rövidített változatának jellemzői hazai mintán. Psychiatria Hungarica 2001, 16, 384–402. [Google Scholar]

- Pukas, L.; Rabkow, N.; Keuch, L.; Ehring, E.; Fuchs, S.; Stoevesandt, D.; Sapalidis, A.; Pelzer, A.; Rehnisch, C.; Watzke, S. Prevalence and predictive factors for depressive symptoms among medical students in Germany-a cross-sectional study. GMS J. Med. Educ. 2022, 39, Doc13. [Google Scholar]

- Győrffy, Z.; Dweik, D.; Girasek, E. Workload, mental health and burnout indicators among female physicians. Hum. Resour. Health 2016, 14, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kötter, T.; Tautphäus, Y.; Obst, K.U.; Voltmer, E.; Scherer, M. Health-promoting factors in the freshman year of medical school: A longitudinal study. Med. Educ. 2016, 50, 646–656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moir, F.; Patten, B.; Yielder, J.; Sohn, C.S.; Maser, B.; Frank, E. Trends in medical students’ health over 5 years: Does a wellbeing curriculum make a difference? Int. J. Soc. Psychiatry 2023, 69, 675–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Olds, T.; Curtis, R.; Dumuid, D.; Virgara, R.; Watson, A.; Szeto, K.; O’COnnor, E.; Ferguson, T.; Eglitis, E.; et al. Effectiveness of physical activity interventions for improving depression, anxiety and distress: An overview of systematic reviews. Br. J. Sports Med. 2023, 57, 1203–1209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Mello, M.T.; Lemos, V.e.A.; Antunes, H.K.; Bittencourt, L.; Santos-Silva, R.; Tufik, S. Relationship between physical activity and depression and anxiety symptoms: A population study. J. Affect. Disord. 2013, 149, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour: At a Glance; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2020; Available online: https://www.who.int/southeastasia/publications/i/item/9789240014886 (accessed on 5 June 2025).

- La Rosa, V.L.; Ching, B.H.; Commodari, E. The Impact of Helicopter Parenting on Emerging Adults in Higher Education: A Scoping Review of Psychological Adjustment in University Students. J. Genet. Psychol. 2025, 186, 162–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, C.; Shi, H.; Li, G. Helicopter parenting and college student depression: The mediating effect of physical self-esteem. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1329248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, W.; Jung, E.; Hadi, N.; Kim, S. Parental control and college students’ depressive symptoms: A latent class analysis. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0287142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teychenne, M.; White, R.L.; Richards, J.; Schuch, F.B.; Rosenbaum, S.; Bennie, J.A. Do we need physical activity guidelines for mental health: What does the evidence tell us? Ment. Health Phys. Act. 2020, 18, 100315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lesesne, C.A.; Visser, S.N.; White, C.P. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and self-reported health and lifestyle behaviors in the United States. J. Adolesc. Health 2011, 49, 113–119. [Google Scholar]

- Schuch, F.B.; Vancampfort, D.; Rosenbaum, S.; Richards, J.; Ward, P.B.; Stubbs, B. Exercise for depression in adults: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 77, 197–207. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, M.C.; Bazargan, M.; Cobb, S.; Assari, S. Mental and Physical Health Correlates of Financial Difficulties Among African-American Older Adults in Low-Income Areas of Los Angeles. Front. Public Health 2020, 8, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, T.; Elliott, P.; Roberts, R.; Jansen, M. A Longitudinal Study of Financial Difficulties and Mental Health in a National Sample of British Undergraduate Students. Community Ment. Health J. 2017, 53, 344–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erhun, W.O.; Jegede, A.O.; Ojelabi, J.A. Implications of failure on students who have repeated a class in a faculty of pharmacy. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 166–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zając, T.; Perales, F.; Tomaszewski, W.; Xiang, N.; Zubrick, S.R. Student mental health and dropout from higher education: An analysis of Australian administrative data. High. Educ. 2024, 87, 325–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leow, T.; Li, W.W.; Miller, D.J.; McDermott, B. Prevalence of university non-continuation and mental health conditions, and effect of mental health conditions on non-continuation: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Ment. Health 2025, 34, 222–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramsdal, G.H.; Bergvik, S.; Wynn, R. Long-term dropout from school and work and mental health in young adults in Norway: A qualitative interview-based study. Cogent Psychol. 2018, 5, 1455365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A. Self-Efficacy: The Exercise of Control; Macmillan: London, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Chemers, M.M.; Hu, L.T.; Garcia, B.F. Academic self-efficacy and first year college student performance and adjustment. J. Educ. Psychol. 2001, 93, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tangney, J.P.; Dearing, R.L. Shame and Guilt; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Pekrun, R. The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educ. Psychol. Rev. 2006, 18, 315–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buunk, A.P.; Gibbons, F.X. Social comparison: The end of a theory and the emergence of a field. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 2007, 102, 3–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fazia, T.; Bubbico, F.; Nova, A.; Buizza, C.; Cela, H.; Iozzi, D.; Calgan, B.; Maggi, F.; Floris, V.; Sutti, I.; et al. Improving stress management, anxiety, and mental well-being in medical students through an online Mindfulness-Based Intervention: A randomized study. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 8214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frajerman, A. Which interventions improve the well-being of medical students? A review of the literature. Encephale 2020, 46, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohmand, S.; Monteiro, S.; Solomonian, L. How are Medical Institutions Supporting the Well-being of Undergraduate Students? A Scoping Review. Med. Educ. Online 2022, 27, 2133986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Data Collection (Year/Semester) | Age (Mean, SD) | Gender (%) | Students Ratio (%) | Respondents (n) | All Students per Year (n) | Response Rate (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Original-Entry Cohort | Repeater | |||||

| I/1. | 19.48 (1.28) | 39.80 | 59.70 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 196 | 203 | 96.6% |

| I/2. | 19.81 (1.41) | 38.50 | 60.40 | 100.00 | 0.00 | 192 | 193 | 99.5% |

| II/1. | 20.70 (1.34) | 36.30 | 59.90 | 68.20 | 31.80 | 157 | 182 | 86.3% |

| III/1. | 22.35 (1.73) | 39.70 | 59.60 | 55.90 | 44.10 | 136 | 147 | 92.5% |

| IV/1. | 23.29 (1.81) | 38.50 | 58.70 | 56.00 | 44.00 | 109 | 155 | 70.3% |

| Hungarostudy Versus… | I/1. Versus… | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | CI | Χ2 | p | OR | CI | Χ2 | p | ||

| I/1. | 3.095 ** | 2.007–4.773 | 27.238 | <0.001 | - | - | - | - | - |

| I/2. | 5.196 ** | 3.375–8.000 | 60.364 | <0.001 | I/2. | 1.679 * | 1.123–2.511 | 6.403 | 0.011 |

| II/1. | 2.374 ** | 1.416–3.979 | 11.094 | <0.001 | II/1. | 0.767 | 0.469–1.255 | 1.116 | 0.291 |

| III/1. | 1.248 | 0.658–2.369 | 0.463 | 0.496 | III/1. | 0.403 * | 0.217–0.751 | 8.507 | 0.004 |

| IV/1. | 1.527 | 0.783–2.976 | 1.559 | 0.212 | IV/1. | 0.493 * | 0.258–0.944 | 4.658 | 0.031 |

| Altogether | Original-Entry Cohort | Repeater | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference | Data Collection | OR (CI) | Χ2 | p | OR (CI) | Χ2 | p | OR (CI) | Χ2 | p |

| Hungarostudy | I/1. | 3.095 ** (2.007–4.773) | 27.238 | <0.001 | 3.095 * (2.007–4.773) | 27.238 | <0.001 | no repeater participated | ||

| I/2. | 5.196 ** (3.375–8.000) | 60.364 | <0.001 | 5.196 * (3.375–8.000) | 60.364 | <0.001 | no repeater participated | |||

| II/1. | 2.596 ** (1.637–4.116) | 16.988 | <0.001 | 2.374 * (1.416–3.979) | 11.094 | <0.001 | 3.121 ** (1.625–5.995) | 12.458 | <0.001 | |

| III/1. | 2.165 * (1.331–3.521) | 9.913 | 0.002 | 1.248 (0.658–2.369) | 0.463 | 0.496 | 3.831 ** (2.094–7.007) | 20.573 | <0.001 | |

| IV/1. | 2.309 * (1.379–3.864) | 10.432 | 0.001 | 1.527 (0.783–2.976) | 1.559 | 0.212 | 3.641 ** (1.888–7.022) | 16.146 | <0.001 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Horváth-Sarródi, A.; Berényi, K.; Gács, B.; Gerencsér, G.; Tisza, B.B.; Pozsgai, É.; Kiss, I. Mental Health Trajectories in Medical Students: The Impact of Academic Repetition on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health. J. Clin. Med. 2025, 14, 8447. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238447

Horváth-Sarródi A, Berényi K, Gács B, Gerencsér G, Tisza BB, Pozsgai É, Kiss I. Mental Health Trajectories in Medical Students: The Impact of Academic Repetition on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2025; 14(23):8447. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238447

Chicago/Turabian StyleHorváth-Sarródi, Andrea, Károly Berényi, Boróka Gács, Gellért Gerencsér, Boglárka Bernadett Tisza, Éva Pozsgai, and István Kiss. 2025. "Mental Health Trajectories in Medical Students: The Impact of Academic Repetition on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health" Journal of Clinical Medicine 14, no. 23: 8447. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238447

APA StyleHorváth-Sarródi, A., Berényi, K., Gács, B., Gerencsér, G., Tisza, B. B., Pozsgai, É., & Kiss, I. (2025). Mental Health Trajectories in Medical Students: The Impact of Academic Repetition on Depressive Symptoms and Self-Rated Health. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 14(23), 8447. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm14238447