Abstract

Fairness reputation refers to the perception of others’ adherence to fair norms based on their behaviors. However, previous studies often rely on simple correlation and regression analyses without comparing cognition across roles in the ultimatum game (UG) and the dictator game (DG). Our study measured the categorical and two-dimensional cognitions (warmth-competence) of participants with different social value orientations toward proposers, responders, and dictators with varying fairness reputations. We found that proposers and dictators with fairness reputations were perceived more positively, and individualists could better distinguish between them. Regarding responders with fairness reputations, they were perceived as more fair, trustworthy, and competent, but less altruistic, cooperative, and warm. The social cognitive network of responders differed from those of proposers and dictators, with warmth cognition being central to three roles, supporting the warmth–competence model. This study highlighted the differential impact of fairness reputation in shaping social cognitions, providing insights into understanding social interactions.

1. Introduction

Fairness is a core social norm that underpins honesty, trust, and reciprocity, and is crucial for stable cooperation (; ). Individuals prefer cooperating with fair individuals to maintain stable collaborations (; ). Thus, understanding whether someone has enforced fairness norms in their past behavior (i.e., fairness reputation) is crucial in social interactions. The Ultimatum Game (UG) and Dictator Game (DG) assess fairness in decision-making (; ). In the UG, a proposer offers a split, and a responder can accept or reject it; a rejection results in no earnings (). Fair proposers typically offer 40–60%, while unfair ones offer less than 20–30% (; ; ). Fair responders reject unfair offers, while unfair responders accept them (). The DG simplifies this by giving the dictator full control, with fairness measured by whether they distribute at least 30% ().

Research has demonstrated that fair proposers and dictators were perceived positively, while unfair ones elicit negative social cognition (). Fair proposers were seen as more trustworthy and likable, whereas unfair ones elicit moral aversion (). Similarly, fair dictators are perceived as more credible and warm (; ). However, the underlying motives of fair proposers and dictators may differ (). Proposers offered fair allocations by suppressing self-interest to adhere to fairness rules (altruistic fairness) or strategic considerations to minimize monetary losses from rejection (strategic fairness) (). In contrast, dictators did not fear rejection, so their equitable distributions were usually viewed as acts of pure selfless fairness (). Thus, there may have been differences in the social cognition of proposers and dictators, with or without fairness reputations that remain to be clarified.

Research on how responders’ fairness reputations affect social cognition has yielded mixed results. Some argue that rejecting unfair offers enforces fairness norms and earns moral approval, while acceptance reflects self-interest (; ). Others suggest that rejection is an intuitive but disruptive act, whereas acceptance is seen as a rational choice that maintains cooperation, leading to perceptions of warmth and likability (; ; ). These inconsistencies highlight the need for more advanced methods to assess social cognition.

Most research has used categorical ratings to measure social cognition, but the warmth–competence model could be a more integrative approach. Categorical ratings like trustworthiness and likability failed to capture the nuances across fairness reputation roles (; ). Researchers have suggested that warmth and competence are two universal dimensions of social cognition (; ). Warmth referred to the perceived intentions, and competence referred to the perceived ability to execute those intentions (). Studies show that unfair responders appeared warmer, while fair dictators were warmer than those who were unfair (; ; ). However, the relationship between warmth, competence, and categorical social cognition remains unclear (). Warmth is widely recognized as a primary dimension in social judgment, providing a basis for evaluating potential threats or benefits in social interactions and for inferring others’ intentions and moral motives (). Compared with warmth, competence is often considered secondary, as it is related more to ability than to social intention. Observers have inferred moral character from others’ behaviors, and such inferences critically shaped subsequent moral evaluations (). In fairness-related contexts, fairness behavior conveys moral intention and adherence to social norms (; ), suggesting that one’s fairness reputation is primarily processed through the warmth dimension.

Network analysis maps relationships between multiple variables and can reveal links between categorical social cognition and warmth–competence dimensions (). Compared to traditional statistical methods (e.g., regression analysis), network analysis allows for controlled variable comparisons, identifies central cognition via node attributes, and mitigates overfitting using LASSO (Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator) regularization (; ). Thus, we used network analysis to compare the structure of social cognitive networks ().

In addition, social value orientations (SVO) reflect individuals’ preferences for balancing self-interest and others’ welfare (). Prosocial individuals favored cooperation for mutual benefit, while individualists prioritized personal gains (). This may stem from prosocials integrating moral principles into their identity, whereas individualists associate positive emotions with self-serving actions (). Since people tend to project their own motives onto others (), we assessed SVOs, predicting that they would shape observers’ cognition of fairness reputation.

To resolve the above issue, we recruited participants with different SVOs (prosocial and individualistic) and asked them to observe the decision-making behaviors of three roles (UG proposer, UG responder, and DG dictator) as well as to evaluate the categorical social cognition of each role (fairness, trustworthiness, altruism, and cooperation) and the warmth–competence dimensions. We employed network analysis to identify the differences in social cognition across roles under different fairness reputations. The hypotheses were as follows: (1) Roles with a fairness reputation were perceived more positively than those without; (2) dictators with versus without fairness reputations would exhibit a greater divergence in social cognition than would proposers, as their fair behavior is attributed to altruistic rather than strategic motives; (3) the social cognition of responders would be ambivalent, with both positive and negative cognitions held toward fair responders; (4) individualistic individuals would better distinguish fairness reputations across roles than prosocial individuals; and (5) warmth would function as a central node in the social cognitive network, which is closely linked to other categorical cognitions.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

Non-psychology and non-economics majors at a university in Hangzhou were recruited as participants through the university’s bulletin board system. All the participants reported that they had not participated in a similar experiment before. The optimal sample size was estimated using G*Power 3.1 in F-tests (ANOVA, repeated measures) covering between-subject factors, within-subject factors, and within–between interactions. Assuming α = 0.05, power (1 − β) = 0.90, and a medium effect size f = 0.20, the sample size was determined to be 108, which was the largest among all F-tests to detect both the main effects and interaction. The effect size of f = 0.25 was chosen because it represents a medium effect according to () and has been reported in previous studies examining fairness and social value orientation effects in economic decision-making tasks (). Details of the sample size calculation are attached to the Supplementary Material. A total of 170 participants took part in this experiment. After examining the data and balancing the number of participants with different SVOs (see Supplementary Materials for details), 122 valid participants were included in the data analyses (61 males ranging from 18 to 29 years; Mage = 20.68 years, SE = 1.94). All participants were right-handed, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision, and reported no prior history of neurological or psychiatric disorders. They voluntarily participated in the experiment and signed an informed consent form before the experiment began. After the experiment, they were given a reward of 20 yuan. This study received ethical approval from an institutional research ethics committee prior to data collection.

2.2. Stimuli and Procedures

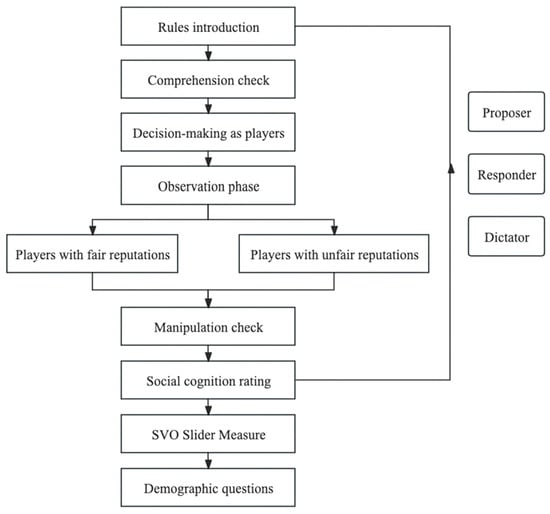

This study utilized a structured survey method (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The survey processes.

After introducing the rules of the decision-making task, a comprehension check was conducted to ensure participants correctly understood the rules. Then, the participants engaged in decision-making processes as players in the corresponding roles, with the aim of enhancing their comprehension of the established rules.

During the observation phase, the participants were asked to observe the decision-making behaviors of other players to learn about their fairness reputations. A player was classified as “fair” if ≥80% of their observed actions met the fairness rule, and they were classified as “unfair” if ≥80% of their observed actions met the unfairness rule. Based on the roles and reputation types, the players were categorized into six types: fair proposer in UG (FP), unfair proposer in UG (UP), fair responder in UG (FR), unfair responder in UG (UR), fair dictator in DG (FD), and unfair dictator in DG (UD). Each identity participated in ten rounds of decision-making.

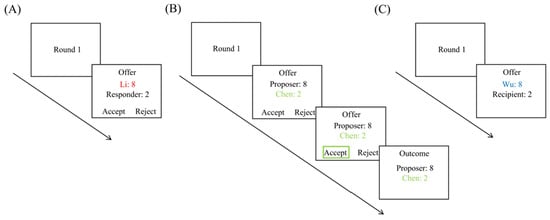

The proposer’s decision-making procedure is shown in Figure 2A. At the beginning of each trial, the serial number of the current trial was presented for 500 ms. Next, an offer of the proposer for the current trial was displayed on the screen, with “Accept” and “Reject” buttons at the bottom to indicate that the responder’s decision was awaited, lasting 1500 ms. To enhance the sense of reality, two of the ten rounds of decision-making were set to be opposite to the reputation type, serving as fillers. Fair proposers often proposed fair offers as follows (proposer/responder): 5:5, 6:4, 6:4, 5:5, 9:1, 5:5, 8:2, 6:4, 5:5, and 6:4. In contrast, unfair proposers often proposed unfair offers as follows (proposer/responder): 8:2, 5:5, 8:2, 9:1, 9:1, 8:2, 6:4, 9:1, 8:2, and 9:1.

Figure 2.

Illustration of the observation phase: (A) proposer, (B) responder, and (C) dictator.

The responder’s decision-making procedure is shown in Figure 2B. At the beginning of each trial, the serial number of the current trial was presented for 500 ms. Next, an offer from the proposer for the current trial was displayed on the screen, with the “Accept” and “Reject” buttons at the bottom to indicate that the responder’s decision was awaited, lasting 1500 ms. Then, the “Accept” or “Reject” button was framed by a green square, indicating the responder’s decision in this trial, lasting 2000 ms. Finally, the outcome of both players in this trial was displayed for 1000 ms. To enhance the sense of reality, two of the ten rounds of decision-making were set to be opposite to the reputation type. Responders with fair reputations often rejected unfair offers as follows (proposer/responder, decision behavior): 8:2 (reject), 6:4 (accept), 9:1 (reject), 8:2 (reject), 9:1 (reject), 9:1 (reject), 8:2 (accept), 8:2 (reject), 5:5 (accept), and 9:1 (reject). In contrast, responders with unfair reputations often accepted unfair offers as follows (proposer/responder, decision behavior): 8:2 (accept), 9:1 (accept), 6:4 (accept), 8:2 (accept), 9:1 (accept), 9:1 (accept), 8:2 (accept), 9:1 (reject), 5:5 (accept), and 8:2 (accept).

The dictator’s decision-making procedure is shown in Figure 2C. The process was similar to the proposer’s except that there was no button at the bottom.

After the observation phase, the participants were required to answer manipulation check questions to assess whether they had learned about the players’ fairness reputations. Afterward, the participants were asked to evaluate their social perceptions of the players’ behavior on a seven-point Likert scale that ranged from 1 (totally disagree) to 7 (totally agree). The evaluations included both categorical social cognition (fairness, trustworthiness, altruism, and cooperation); two dimensions of social cognition, such as warmth (sincere, good natured, warm, tolerant, and friendly); and competence (competent, confident, independent, intelligent, and competitive) (; ; ). Finally, the participants completed the SVO Slider Measure and demographic questions.

The trial order within each role was fixed rather than randomized to ensure that the participants could form a stable impression of each role’s behavioral pattern across the trials. However, the reputation conditions were counterbalanced between participants: half of the participants first observed roles without a fairness reputation and then those with a fairness reputation, while the other half experienced the opposite order.

The details of comprehension check questions are provided in the Supplementary Material.

2.3. Data Analyses

Firstly, we conducted fairness reputation manipulation checks separately for roles to ensure that participants learned about the fairness reputation of the different players. Paired-samples t-tests were conducted on the estimated means of the offers per trial proposed by proposers and dictators under different fairness reputation conditions. A chi-square test was conducted on the predictions of responders’ subsequent choices under different fairness reputation conditions.

Secondly, we compared the categorical social cognition and the two dimensions of the social cognition of prosocial and individualistic participants towards different roles under different fairness reputation conditions. For the proposers and dictators, a series of 2 (fairness reputation: fair vs. unfair) × 2 (SVO: prosocial vs. individualistic) × 2 (role: proposer vs. dictator) mixed-design ANOVAs was conducted. For the responders, a series of 2 (fairness reputation: fair vs. unfair) × 2 (social value orientation: prosocial vs. individualistic) mixed-design ANOVAs was conducted. For the sensitivity power analysis, N = 122, α = 0.05, power (1 − β) = 0.90, detected minimum effect sizes of f = 0.13 for the 2 × 2 × 2 mixed ANOVAs, and f = 0.16 for the 2 × 2 mixed ANOVAs. The above details of the sensitivity power analysis are explicitly reported in the Supplementary Material. All reported significant effects exceeded this threshold, suggesting they were sufficiently powered. However, we acknowledge that this study may be underpowered to detect very small interaction effects. Where applicable, we used the Welch/Kenward–Roger corrections via the afex package (version 1.3-1) in R to ensure robust inference in the presence of potential heteroskedasticity. To control for type I error inflation due to multiple correlated dependent variables, we applied Holm–Bonferroni corrections within the logical hypothesis families. For each experimental hypothesis (e.g., the main effects of fairness reputation, SVO, role, and their interactions), corrections were applied across the six dependent variables (fairness, trustworthiness, altruism, cooperation, warmth, and competence). All reported p-values reflect these conservative corrections.

Finally, we examined the relationship between categorical and two-dimensional social cognitions within and between roles. (1) We estimated the structure of the social cognitive networks of proposers, responders, and dictators using the six cognitions as nodes. After applying a nonparanormal (npn) transformation to reduce non-normality, we computed Pearson correlations on the transformed data and estimated the regularized partial-correlation networks separately for each role using the GLASSO (Graphical LASSO) model based on the Extended Bayesian Information Criterion (EBIC) with the default tuning parameter γ = 0.5. Node positions were then optimized for visualization. To assess robustness, we conducted supplementary analyses comparing Pearson (on npn-transformed data) versus polychoric correlations and EBIC γ values of 0.25 and 0.75; these robustness checks are reported in Supplementary Material. (; ). (2) We calculated the centrality indices of the networks, including strength, betweenness, closeness, and expected influence (EI) (; ; ). (3) We utilized the Network Comparison Test (NCT) version 2.2.2 to compare the social cognitive networks across roles ().

We conducted data analyses using SPSS version 26.0, R version 4.3.2, qgraph (version 1.9.8), and bootnet (version 1.6), with a statistical significance of α = 0.05 (two-tailed). To assess the assumption of homogeneity of variances in ANOVA analyses, we conducted Levene’s tests. In cases where this assumption was violated, we applied the Greenhouse–Geisser correction and reported the adjusted results. All the results were corrected using Bonferroni tests if there were more than three groups in the post hoc and simple effects analyses. All results of the Network Comparison Test (NCT) were adjusted using the Holm–Bonferroni correction to control for multiple comparison errors, with the significance level set at p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Fairness Reputations Manipulation Check

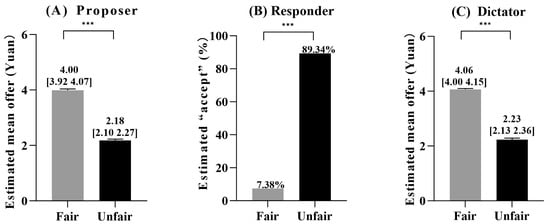

Manipulation checks confirmed successful fairness reputation assignments for proposers, responders, and dictators. The participants’ estimated offers closely matched the predefined values for proposers and dictators, and responders’ expectations aligned with the intended fairness conditions (Figure 3). The specific statistical values, including t, χ2, means, and standard errors, are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 3.

The results of the fairness reputation manipulation checks: (A) proposer role, (B) responder role, and (C) dictator role. Significance level: *** p < 0.001. Error bars indicate standard errors.

3.2. Social Cognition of Roles Under Varying Fairness Reputation Conditions

3.2.1. Homogeneity Test of Variance on Social Cognition of Proposers and Dictators

A homogeneity test of variance was conducted on the warmth ratings for proposers and dictators. The results indicated significant differences in variance between fair and unfair roles across both prosocial and individualistic participants, with a greater variability observed for fair proposers and dictators. However, no significant differences in group covariance matrices were found for other social cognitions (Supplementary Materials Figure S2 for details).

3.2.2. ANOVA Results on Social Cognition of Proposers and Dictators

The means and standard errors (SE) on social cognitions of “fair” vs. “unfair” proposers/dictators are shown in Table 1. The specific statistical values for all ANOVAs, including the F, ηp2, and Confidence Interval (CI), are shown in Table 2.

Table 1.

The means and standard errors (SE) on social cognitions of “fair” vs. “unfair” proposers/dictators.

Table 2.

The summary of mixed ANOVA results on social cognitions of “fair” vs. “unfair” proposers/dictators.

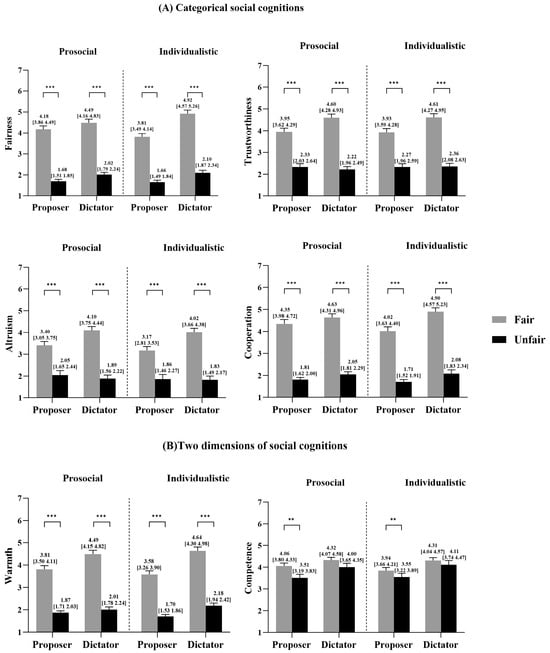

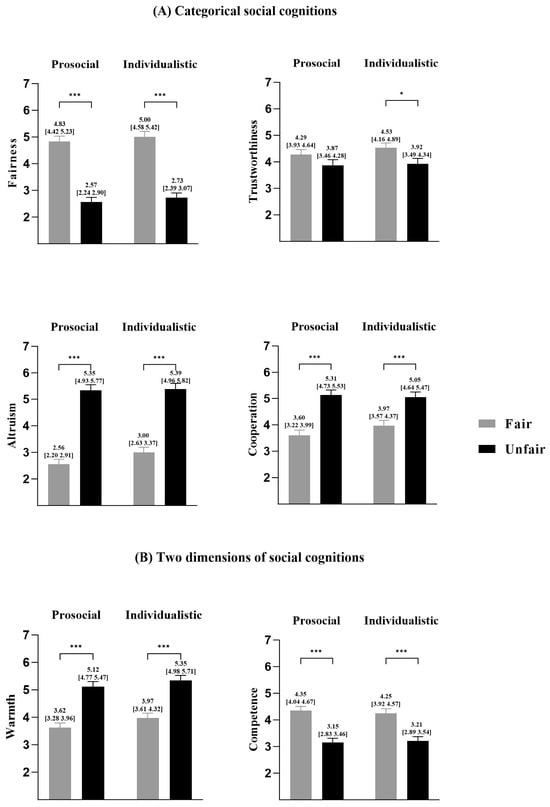

Regarding the main effects, we found significant effects of the fairness reputation, indicating that fair players were perceived as fairer, more trustworthy, altruistic, cooperative, warm, and competent than unfair players. Similarly, we found significant main effects of the role, indicating that proposers were perceived as less fair, trustworthy, altruistic, cooperative, warm, and competent than dictators (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Social cognition of proposers and dictators under different fairness reputation conditions. (A) Categorical social cognition ratings: fairness, trustworthiness, altruism, and cooperation; (B) two dimensions of social cognition ratings: warmth and competence. Significance level: ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001. Error lines indicate standard errors. Note. FP = fair proposer; UP = unfair proposer; FD = fair dictator; UD = unfair dictator.

Regarding the two-way interactions, we found significant interactions between fairness reputation and role. The simple effect analysis revealed that fair proposers were perceived as more trustworthy, altruistic, cooperative, warm, and competent than unfair proposers; fair dictators were also perceived as more trustworthy, altruistic, cooperative, and warm than unfair dictators, with a larger difference compared to proposers. Additionally, the interactions between role and SVO were also significant. The simple effect analysis indicated that for prosocial participants, proposers were perceived as less fair than dictators; and for individualistic participants, proposers were also perceived as less fair than dictators, with a larger difference than that for prosocial participants (Figure 4).

The specific statistical values for all ANOVAs, including F, ηp2, means, and standard errors, are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

3.2.3. Homogeneity Test of Variance on Social Cognition of Responders

A homogeneity test of variance was conducted on fairness and competence ratings for responders. The variance in fairness ratings differed by responder fairness among prosocial participants, while no significant variance differences were found for competence ratings or other social cognition dimensions (Figure S3).

3.2.4. ANOVA on Social Cognition of Responders’ Fairness Reputations

The means and standard errors (SE) of the social cognitions of “fair” vs. “unfair” responders are shown in Table 3. The specific statistical values for all ANOVAs, including the F, ηp2, and Confidence Interval (CI), are shown in Table 4.

Table 3.

The means and standard errors (SE) on social cognitions of “fair” vs. “unfair” responders.

Table 4.

The summary of mixed ANOVA results on social cognitions of “fair” vs. “unfair” responders.

We found significant effects of the fairness reputation, indicating that fair responders were perceived as fairer, more trustworthy, and competent than unfair players, but were considered less altruistic, cooperative, and warm than unfair players (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Social cognition of responders under different fairness reputation conditions. (A) Categorical social cognition ratings: fairness, trustworthiness, altruism, and cooperation; (B) two dimensions of social cognition ratings: warmth and competence. Significance level: * p < 0.05; *** p < 0.001. Error lines indicate standard errors. Note. FR = fair responder; UR = unfair responder.

The specific statistical values for all ANOVAs, including the F, ηp2, means, and standard errors, are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

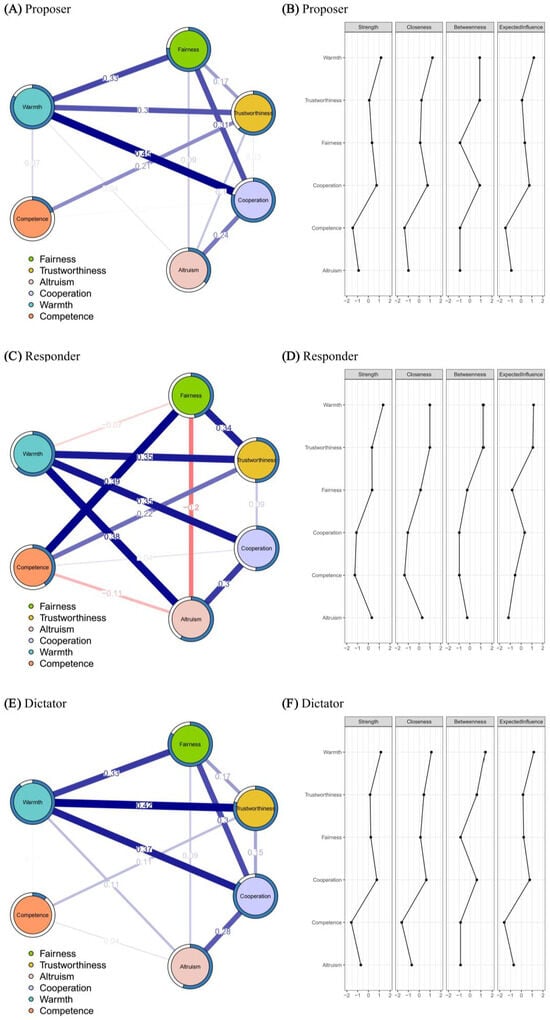

3.3. Relationships Between Categorical and Two Dimensions of Social Cognition

We investigated the relationship between social cognition within and between roles using a regularized partial-correlation network, where the nodes representing warmth, competence, and categorical social cognition were generally interconnected. For the proposer role, warmth was positively correlated with fairness (edge value = 0.33), with trustworthiness (edge value = 0.30), and with cooperation (edge value = 0.45), while competence was positively correlated with trustworthiness (edge value = 0.21) (Figure 6A). For the responder role, warmth was positively correlated with trustworthiness (edge value = 0.35), with cooperation (edge value = 0.35), and with altruism (edge value = 0.38), while competence was positively correlated with fairness (edge value = 0.39) and with trustworthiness (edge value = 0.22). Additionally, there were negative correlations between warmth and fairness (edge value = −0.07), and between competence and altruism (edge value = −0.11) (Figure 6C). For the dictator role, warmth was positively correlated with fairness (edge value = 0.33), with trustworthiness (edge value = 0.42), and with cooperation (edge value = 0.37), while competence was positively correlated with trustworthiness (edge value = 0.11) (Figure 6E).

Figure 6.

Social cognitive network of (A) the proposers and their (B) standardized centrality estimates; (C) the responders and their (D) standardized centrality estimates; and (E) the dictators and their (F) standardized centrality estimates. The nodes denote categorical and two dimensions of social cognition. Regularized partial correlations were estimated using the EBIC-GLASSO model based on Pearson correlations after nonparanormal (npn) transformation. The pie chart surrounding each node represents its predictability (R2), with a larger proportion of blue indicating a higher explained variance. The pie chart surrounding a node illustrates that node’s predictability within the network, with a larger proportion of blue indicating higher predictability. The edges indicate regularized partial correlations between two nodes. The edge values represent the strength of partial correlations; a larger value indicates a stronger association between two nodes and a thicker edge. The color of the edge represents the direction of the correlation, with blue edges indicating positive associations and red edges indicating negative associations.

The results of centrality indices revealed that warmth emerged as the most central node in the networks for the proposer, responder, and dictator, as indicated by high values in strength, closeness, betweenness, and EI, followed by trustworthiness (Figure 6B,D,F). Additionally, cooperation exhibited high centrality within the social cognitive networks for the proposer and dictator roles (Figure 6B,F). The centrality indices metrics for each node within each network are detailed in Table S1 of the Supplementary Materials.

The network stability analysis showed adequate to good centrality stability (CS) across all networks (Proposer: Strength = 0.75, Expected Influence = 0.75, Closeness = 0.516; Responder: Strength = 0.283, Expected Influence = 0.594, Closeness = 0.439; Dictator: Strength = 0.75, Expected Influence = 0.75, Closeness = 0.672; all > 0.25; ). Detailed bootstrapped difference plots for nodes and edges are provided in Figures S3–S5 of the Supplementary Materials.

Next, we conducted pairwise comparisons of the social cognitive networks between the proposer, responder, and dictator using the Network Comparison Test (NCT).

For the social cognitive networks of the proposer and responder, there was no significant difference in the global strength of the networks (strength difference = 0.46; p = 0.149); however, there was a significant difference in the overall structure of the networks (maximum edge weight difference = 0.39; p = 0.002). An examination of individual edges revealed that five edges showed a statistical difference between these two networks (ps < 0.05). Compared to the proposer’s network, the responder’s network exhibited weaker associations between warmth and fairness, and between fairness and cooperation. It also showed stronger associations between warmth and altruism, and between competence and fairness, along with an inverse negative association between fairness and altruism.

For the social cognitive networks of the responder and dictator, there was no significant difference in the network global strength of the networks (strength difference = 0.46; p = 0.225); however, there was a significant difference in the overall network structure (maximum difference in edge weights = 0.39; p = 0.002). Examination of individual edges revealed that four edges showed a statistical difference between these two networks (ps < 0.05). Compared to the proposer’s network, the responder’s network exhibited weaker associations between warmth and fairness, and between fairness and cooperation. It also showed stronger associations between competence and fairness, along with an inverse negative association between fairness and altruism.

Regarding the social cognitive networks of the proposer and dictator, no significant differences were found in the network global strength (strength difference < 0.001; p = 0.997) or overall network structure (maximum difference in edge weights = 0.12; p = 0.916). Details of the edge weights in the social cognitive networks between the three roles are presented in Table S2 of the Supplementary Materials.

Furthermore, we compared the social cognitive networks between prosocial and individualistic participants to examine whether different SVO orientations influenced the structure of fairness-related social cognition. The two groups showed generally consistent overall structures and global strengths across the proposer, responder, and dictator networks, with no significant group differences observed, as shown in Figure S6 of the Supplementary Material.

4. Discussion

This study examined the influence of the fairness reputations of the UG proposer, UG responder, and DG dictator on the social cognition of observers with different SVOs. First, proposers and dictators with fairness reputations were perceived more positively than those without, and the differences in social cognition between dictators with varying fairness reputations were more pronounced than between proposers. Moreover, individualists exhibited greater differences in social cognition of the proposers and dictators, with varying fairness reputations compared to the prosocials. Second, responders with fairness reputations were perceived as more fair, trustworthy, and competent, but less altruistic, cooperative, and warm. Finally, warmth functioned as a central node in the social cognitive network of the proposer, responder, and dictator, though the social cognitive network of the responder was significantly different from the other two roles. Our findings elucidated the different impact of fairness reputation on social cognition across roles, expanded the warmth–competence model, and highlighted the significance of fairness in social interactions.

4.1. The Influence of Fairness Reputation on Social Cognition to Proposers and Dictators

We found that proposers and dictators with fairness reputations tended to be perceived as more fair, trustworthy, altruistic, cooperative, warm, and competent. Their fair offers may have reflected adherence to the fairness norm () and aligned with the cooperation norm of maximizing public benefits (; ). The consistent and predictable behavioral patterns served as reliable signals and enhanced trustworthiness (; ). Moreover, their ability to process moral information and self-regulate may have been interpreted as being aligned with moral intelligence theory, which could partly explain their perceived competence (). Notably, warmth perceptions exhibited greater heterogeneity, being higher when fair behavior was attributed to prosocial motivations such as fairness or altruism, and being lower when attributed to strategic considerations or self-interest (; ).

In addition, the difference in social cognition between dictators with and without fairness reputations was more pronounced than between proposers, possibly due to the differing motivations of these two roles. The fairness behavior of the proposer in the UG may be driven by strategic motivation to avoid rejection and maximize self-interest rather than pure altruism (; ). In contrast, dictators in the DG may be perceived as driven by fairness norms or altruistic motivations, given their absolute power in determining outcomes for both participants (). Therefore, the social cognition between dictators with and without fairness reputations was more polarized than between proposers.

4.2. The Influence of Fairness Reputation on Social Cognition of Responders

On the one hand, responders with fairness reputations tended to be perceived more positively, being seen as somewhat fairer, more trustworthy, and more competent compared to those without fairness reputations. By consistently rejecting unfair offers and sacrificing self-interest to enforce fairness norms, these responders may have strengthened observers’ fairness perceptions (). Moreover, the behavioral consistency of responders with fairness reputations appeared to be interpreted as a stable and reliable signal, associated with higher perceived trustworthiness, which is consistent with proposers and dictators with fairness reputations (; ). This result aligned with previous research, which also found a trend of higher competence perceptions toward responders with fair reputations (). In our study, participants observed both responders with and without fairness reputations, leading to a comparison between the two responders, which made the differences more pronounced ().

On the other hand, responders with fairness reputations may also be perceived more negatively, being seen as less altruistic, cooperative, and warm. Their rejections harmed the proposer’s interests and minimized the total earnings (), violating the cooperation norm of maximizing collective benefits and contradicting the essence of altruism, which aims to increase the welfare of others (; ). Moreover, rejection behaviors were attributed to aroused anger and seen as spiteful actions, which were contrary to the definition of warmth, leading to them being perceived as lacking warmth (; ; ).

4.3. Relationship Between Categorical and Two Dimensions of Social Cognition

Warmth emerged as the central node across all roles’ social cognitive networks, validating its primacy in the warmth–competence model (; ). The prioritization of warmth judgments is rooted in the evolutionary necessity of rapidly discerning others’ intentions as friendly or hostile, thereby providing a basis for decisions regarding potential threats (). For proposers and dictators, warmth was more closely linked to fairness, trustworthiness, and cooperation, as their fair behaviors directly reflected the connection between reputation and benefits (; ; ). However, the weak association between warmth and altruism suggested the motive attributions were strategic (e.g., reputation maintenance) rather than altruistic (). For responders, warmth was more closely linked to trustworthiness, cooperation, and altruism, as rejection behaviors served as altruistic punishments but undermined cooperation, preventing partners from gaining benefits ().

Competence showed only a weak correlation with trustworthiness across all roles’ social cognitive networks, as it is regarded as an “instrumental trait” that only concerns task efficiency. Low competence may undermine the joint goal and reduce trustworthiness, while high competence may increase the perception of “strategic exploitation,” thereby diminishing trust. Therefore, although competence can predict trustworthiness to some extent, warmth is still needed to help judge intentions (; ). In addition, the competence perceptions of responders were correlated with fairness. This may be because the rejection behavior of responders is a costly punishment, where they sacrifice their own interests to enforce fairness norms and achieve moral goals (; ).

4.4. The Influence of Observer Social Value Orientation on Social Cognition of Fairness Reputation

Our study found some evidence that individualists and prosocials may differ in their perception of fairness between proposers and dictators; however, this pattern was observed specifically for fairness ratings after applying rigorous statistical corrections. One possible explanation for this pattern is that observers tend to assume that others share similar motivations, which may lead to differences in their perception and evaluation of others’ behaviors (). Under this account, prosocials may be more inclined to assume that others also have prosocial motivations, while individualists may tend to assume that others are motivated by self-interest (; ). This could lead individualists to infer that proposers’ fair distributions represent strategic behaviors to avoid rejection, while perceiving dictators’ fair distributions as potentially driven by genuine altruism. However, we stress that this interpretation remains speculative, as motive attributions were not directly measured in the present study. Future research should therefore incorporate explicit assessments of motive attributions or use modeling approaches to test whether reputation evaluations are indeed mediated by perceived intentions.

Notably, prosocials showed lower consistency in their fairness perceptions of responders with fairness reputations, as prosocials have distinct motivations of inequity aversion and joint gain maximization (). Individuals with inequity aversion were sensitive to the equality between payoffs, and the rejection behaviors made the outcomes more equal, increasing observers’ fairness perceptions. In contrast, those focused on joint gain maximization perceived rejection as undermining overall gains, reducing observers’ perceptions of fairness.

4.5. Limitations and Future Perspectives

First, the experimental design restricted fairness reputation learning to observing distributional behaviors in classic UG/DG paradigms, excluding multimodal cues like verbal/prosodic signals (; ), potentially compromising its ecological validity. Future studies could utilize virtual reality to integrate visual–semantic–prosodic information () and adopt real-world scenarios () to improve the design’s ecological and external validity. Additionally, our sample consisted solely of Chinese university students, which limits the generalizability of the findings across cultural contexts. Notably, the competent-cold pattern observed in fair responders in our study has also been documented in international and cross-cultural data, as well as in research on individual stereotypes (). Future research could examine whether this competent-cold pattern for fair responders is observed across different cultural contexts.

Second, although we found differences in social cognition toward proposers and dictators from the perspective of group means, there may be individual differences in motive attribution (strategic vs. altruistic fairness) (). Future research should directly measure motive inferences per trial and employ neurophysiological methods to examine neural correlates of these differences—particularly the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in negative reputation processing and medial prefrontal cortex in context-dependent valuation when choosing partners (; ). Moreover, although the deterministic behavioral sequences and filler trials followed established paradigms in social decision-making research to ensure consistent reputation cues, such fixed patterns may have increased the salience of fairness cues and reduced ecological validity. Future studies should employ more dynamic, probabilistic, and interactive designs to better approximate real-world reputation formation.

Third, a potential limitation of the present study concerns the post hoc balancing of SVO groups. To achieve equal group sizes and enhance the internal validity of between-group comparisons, we included only prosocial participants with relatively larger SVO angles. Although this procedure helped establish clearer group boundaries and improved the interpretability of the SVO-based contrasts, it also reduced the external validity of the findings. The final balanced sample no longer reflects the natural distribution of SVO types in the broader population, where prosocial orientations are typically more prevalent. Therefore, the generalization of the present results to populations with different SVO compositions should be made with caution.

Fourth, we included a small number of inconsistent trials to enhance the ecological validity of the task and to prevent participants from perceiving the fairness reputation manipulation as overly artificial or deterministic. However, because these fillers intentionally deviated from the assigned fairness reputation, they may have introduced ambiguity regarding the strength or consistency of each identity’s reputation. Although the presentation order was fixed within each role and the assignment of fair and unfair reputations was counterbalanced across participants, the present design does not allow us to determine whether the inclusion of fillers attenuated or polarized participants’ fairness judgments. Future studies could employ stimulus materials without such fillers to establish a more distinct and uncontaminated manipulation of fairness reputation and to assess the potential impact of inconsistent behavioral cues on reputation perception.

Finally, this study primarily focused on the impact of fairness reputation on social cognition; however, reputation may also influence decision-making in real situations. For example, individuals were more likely to engage in proactive behaviors when they perceived others as high in warmth, such as actively helping, and reactive behaviors when they perceived others as high in competence, such as accepting advice (). Future research could use behavioral economic tasks (e.g., trust games or the prisoner’s dilemma) to examine whether observers engage in more trusting and cooperative behaviors with fair proposers and dictators. Furthermore, conflicting social cognition of responders may predict increased investment but less cooperation. Given that the present paradigms (the UG and DG) inherently involve fairness, altruism, and reciprocal cooperation, participants’ perceptions and evaluations may have been influenced by multiple overlapping social norms. Future studies could further disentangle these constructs by employing paradigms that isolate fairness from other cooperative motives and by testing whether similar cognitive patterns of fairness reputation emerge.

5. Conclusions

To conclude, this study systematically revealed the influence of fairness reputation on social cognition of different roles (proposers, responders, and dictators). First, fairness reputation reinforced positive trait inferences for proposers and dictators, but it induced contradictory cognition of ‘high competence/low warmth’ for responders. Secondly, individualists were better able than prosocial individuals to differentiate fairness reputation between proposers and dictators, which may stem from motivational differences in attributions between the two. Additionally, the results of the network analyses showed that the social cognitive networks of responders were significantly different from those of the proposers and dictators; however, warmth perception served as the central hub of the social cognitive networks in all three networks, highlighting that warmth cognition occupies an important position in the cognition of fairness reputation. Based on these findings, this study not only shed light on the important role of fairness reputation in social cognition, but it also supported the warmth–competence model and explored its relationship with categorical social cognition.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/bs15111537/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Z.Y.; methodology, Y.Z. and Z.Y.; software, Y.Z. and Y.L.; validation, Y.L. and T.X.; formal analysis, Y.Z. and Y.L.; investigation, Y.Z.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, B.L. and Z.Y.; supervision, B.L.; project administration, Z.Y.; funding acquisition, B.L. and Z.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by grants from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32300857; to Z.Y.), the Starting Research Fund from Hangzhou Normal University (to Z.Y.), the Ministry of Science and Technology of China (STI 2030-Major Projects 2021ZD0201705; to B.L.), the Hangzhou Normal University Discipline and Talent Cultivation Fund (4045C5021920465; to B.L.), and the Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department (Y202353584; to Y.Z.).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and it was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee of Hangzhou Normal University (approval no. 2023-1021, approval date 2 March 2023).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data and code that support the findings of this study are openly available in Open Science Framework (OSF) at https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/G96AQ.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| UG | Ultimatum Game |

| DG | Dictator Game |

| LASSO | Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| SVO | Social Value Orientations |

| SE | Standard Error |

| FP | Fair Proposer |

| UP | Unfair Proposer |

| FR | Fair Responder |

| UR | Unfair Responder |

| FD | Fair Dictator |

| UD | Unfair Dictator |

| ANOVA | Analysis of Variance |

| GLASSO | Graphical Least Absolute Shrinkage and Selection Operator |

| EBIC | Extended Bayesian Information Criterion |

| NCT | Network Comparison Test |

| EI | Expected Influence |

| CS | Centrality Stability |

| CI | Confidence Interval |

| M | Mean |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

References

- Abele, A. E., Cuddy, A. J. C., Judd, C. M., & Yzerbyt, V. Y. (2008). Fundamental dimensions of social judgment. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(7), 1063–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, S., Boone, C., & Declerck, C. (2008). Social value orientation and cooperation in social dilemmas: A review and conceptual model. British Journal of Social Psychology, 47(3), 453–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 91–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, R., Gintis, H., Bowles, S., & Richerson, P. J. (2003). The evolution of altruistic punishment. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 100(6), 3531–3535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bratanova, B., Kervyn, N., & Klein, O. (2015). Tasteful brands: Products of brands perceived to be warm and competent taste subjectively better. Psychologica Belgica, 55(2), 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brosnan, S. F. (2023). A comparative perspective on the human sense of justice. Evolution and Human Behavior, 44(3), 242–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Y., Dong, S., Yuan, S., & Hu, C.-P. (2020). Network analysis and its applications in psychology. Advances in Psychological Science, 28(1), 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camerer, C., & Thaler, R. H. (1995). Anomalies: Ultimatums, dictators and manners. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 9(2), 209–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. (1998). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Colquitt, J. A., & Rodell, J. B. (2011). Justice, trust, and trustworthiness: A longitudinal analysis integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 54(6), 1183–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuddy, A. J., Glick, P., & Beninger, A. (2011). The dynamics of warmth and competence judgments, and their outcomes in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior, 31, 73–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Declerck, C. H., & Bogaert, S. (2008). Social value orientation: Related to empathy and the ability to read the mind in the eyes. The Journal of Social Psychology, 148(6), 711–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durante, F., Tablante, C. B., & Fiske, S. T. (2017). Poor but warm, rich but cold (and competent): Social classes in the stereotype content model. Journal of Social Issues, 73(1), 138–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eisenbruch, A. B., & Roney, J. R. (2017). The skillful and the stingy: Partner choice decisions and fairness intuitions suggest human adaptation for a biological market of cooperators. Evolutionary Psychological Science, 3, 364–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Engel, C. (2011). Dictator games: A meta study. Experimental Economics, 14, 583–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epley, N., Keysar, B., Van Boven, L., & Gilovich, T. (2004). Perspective taking as egocentric anchoring and adjustment. Journal of Personality Social Psychology, 87(3), 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. I. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 195–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Exley, C. (2018). Incentives for prosocial behavior: The role of reputations. Management Science, 64(5), 2460–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farmer, H., Apps, M., & Tsakiris, M. (2016). Reputation in an economic game modulates premotor cortex activity during action observation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 44(5), 2191–2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Fischbacher, U. (2004). Third-party punishment and social norms. Evolution and Human Behavior, 25(2), 63–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Gintis, H. (2007). Human motivation and social cooperation: Experimental and analytical foundations. Annual Review of Sociology, 33(1), 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehr, E., & Schmidt, K. M. (1999). A theory of fairness, competition, and cooperation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 114(3), 817–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fehrler, S., & Przepiorka, W. (2013). Charitable giving as a signal of trustworthiness: Disentangling the signaling benefits of altruistic acts. Evolution Human Behavior, 34(2), 139–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feldman, H., & Friston, K. J. (2010). Attention, uncertainty, and free-energy. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 4, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J., & Glick, P. (2007). Universal dimensions of social cognition: Warmth and competence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 11(2), 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J. L., Savin, N. E., & Sefton, M. (1994). Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior, 6(3), 347–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foygel, R., & Drton, M. (2010). Extended Bayesian information criteria for Gaussian graphical models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 23, 2020–2028. [Google Scholar]

- Gomaa, M. I., Mestelman, S., Nainar, S. K., & Shehata, M. (2017). Endogenous versus exogenous fairness indices in repeated ultimatum games. Theoretical Economics Letters, 7(06), 1568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., & Schwarze, B. (1982). An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 3(4), 367–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harlé, K. M., & Sanfey, A. G. (2010). Effects of approach and withdrawal motivation on interactive economic decisions. Cognition Emotion, 24(8), 1456–1465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J., Boyd, R., Bowles, S., Camerer, C., Fehr, E., Gintis, H., McElreath, R., Alvard, M., Barr, A., Ensminger, J., & Henrich, N. S. (2005). “Economic man” in cross-cultural perspective: Behavioral experiments in 15 small-scale societies. Behavioral Brain Sciences, 28(6), 795–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, X., & Mai, X. (2021). Social value orientation modulates fairness processing during social decision-making: Evidence from behavior and brain potentials. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 16(7), 670–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N., & Epley, N. (2014). The topography of generosity: Asymmetric evaluations of prosocial actions. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 143(6), 2366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, N., Grossmann, I., Uskul, A. K., Kraus, A. A., & Epley, N. (2015). It pays to be nice, but not really nice: Asymmetric reputations from prosociality across 7 countries. Judgment Decision Making, 10(4), 355–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulms, P., & Kopp, S. (2018). A social cognition perspective on human–computer trust: The effect of perceived warmth and competence on trust in decision-making with computers. Frontiers in Digital Humanities, 5, 352444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M., Lucas, G., & Gratch, J. (2021). Comparing mind perception in strategic exchanges: Human-agent negotiation, dictator and ultimatum games. Journal on Multimodal User Interfaces, 15, 201–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z., Dong, D., & Qiao, J. (2022). The role of social value orientation in Chinese adolescents’ moral emotion attribution. Behavioral Sciences, 13(1), 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lim, G., & Kim, H. (2022). Distinctive roles of mPFC subregions in forming impressions and guiding social interaction based on others’ social behaviour. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 17(12), 1118–1130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marchetti, A., Castelli, I., Harlé, K. M., & Sanfey, A. G. (2011). Expectations and outcome: The role of proposer features in the ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Psychology, 32(3), 446–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mellers, B. A., Haselhuhn, M. P., Tetlock, P. E., Silva, J. C., & Isen, A. M. (2010). Predicting behavior in economic games by looking through the eyes of the players. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 139(4), 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R. O., & Ackermann, K. A. (2014). Social value orientation: Theoretical and measurement issues in the study of social preferences. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 18(1), 13–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, R. O., Ackermann, K. A., & Handgraaf, M. J. (2011). Measuring social value orientation. Judgment and Decision making, 6(8), 771–781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A., Page, K. M., & Sigmund, K. (2000). Fairness versus reason in the ultimatum game. Science, 289(5485), 1773–1775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (1998). The dynamics of indirect reciprocity. Journal of theoretical Biology, 194(4), 561–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowak, M. A., & Sigmund, K. (2005). Evolution of indirect reciprocity. Nature, 437(7063), 1291–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parsons, T. D. (2015). Virtual reality for enhanced ecological validity and experimental control in the clinical, affective and social neurosciences. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 9, 660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, Y., Wu, H., & Liu, X. (2017). The influences of social value orientation on prosocial behaviors: The evidences from behavioral and neuroimaging studies. Chinese Science Bulletin, 62(11), 1136–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rilling, J. K., & Sanfey, A. G. (2011). The neuroscience of social decision-making. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 23–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinaugh, D. J., Millner, A. J., & McNally, R. J. (2016). Identifying highly influential nodes in the complicated grief network. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 125(6), 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, A., & Adolphs, R. (2017). Emotion perception from face, voice, and touch: Comparisons and convergence. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 21(3), 216–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siegel, J. Z., Crockett, M. J., & Dolan, R. J. (2017). Inferences about moral character moderate the impact of consequences on blame and praise. Cognition, 167, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simon, J. C., Styczynski, N., & Gutsell, J. N. (2020). Social perceptions of warmth and competence influence behavioral intentions and neural processing. Cognitive, Affective, Behavioral Neuroscience, 20, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strang, S., & Park, S. Q. (2017). Human cooperation and its underlying mechanisms. In Social behavior from rodents to humans: Neural foundations clinical implications (pp. 223–239). Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A., Ito, Y., Kiyama, S., Kunimi, M., Ohira, H., Kawaguchi, J., Tanabe, H. C., & Nakai, T. (2016). Involvement of the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex in learning others’ bad reputations and indelible distrust. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabibnia, G., & Lieberman, M. D. (2007). Fairness and cooperation are rewarding: Evidence from social cognitive neuroscience. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1118(1), 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanner, C., & Christen, M. (2014). Moral intelligence—A framework for understanding moral competences. In M. Christen, C. van Schaik, J. Fischer, M. Huppenbauer, & C. Tanner (Eds.), Empirically informed ethics: Morality between facts and norms (pp. 119–136). Springer International Publishing. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaler, R. H. (1988). Anomalies: The ultimatum game. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 2(4), 195–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thielmann, I., Spadaro, G., & Balliet, D. (2020). Personality and prosocial behavior: A theoretical framework and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(1), 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tracy, J. L., Randles, D., & Steckler, C. M. (2015). The nonverbal communication of emotions. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 3, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, T. W. (2012). Network interventions. Science, 337(6090), 49–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Borkulo, C., Epskamp, S., Jones, P., Haslbeck, J., & Millner, A. (2019). Network comparison test: Statistical comparison of two networks based on three invariance measures. (R package version 2.2.2). CRAN. Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/package=NetworkComparisonTest (accessed on 7 November 2025).

- Van Dijk, E., De Dreu, C. K., & Gross, J. (2020). Power in economic games. Current Opinion in Psychology, 33, 100–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y., Yang, L.-Q., Li, S., & Zhou, Y. (2015). Game theory paradigm: A new tool for investigating social dysfunction in major depressive disorders. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 6, 149463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, Z.-H., Li, Q.-Y., Liang, C.-J., & Liu, H.-Z. (2022). Cognitive process underlying ultimatum game: An eye-tracking study from a dual-system perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 937366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiland, S., Hewig, J., Hecht, H., Mussel, P., & Miltner, W. H. (2012). Neural correlates of fair behavior in interpersonal bargaining. Social Neuroscience, 7(5), 537–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciszke, B., Abele, A. E., & Baryla, W. (2009). Two dimensions of interpersonal attitudes: Liking depends on communion, respect depends on agency. European Journal of Social Psychology, 39(6), 973–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z., Zheng, Y., Yang, G., Li, Q., & Liu, X. (2019). Neural signatures of cooperation enforcement and violation: A coordinate-based meta-analysis. Social Cognitive Affective Neuroscience, 14(9), 919–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y., Yang, S., Chen, X., Bai, Y., & Xie, G. (2023). Reputation update of responders efficiently promotes the evolution of fairness in the ultimatum game. Chaos, Solitons Fractals, 169, 113218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).