1. Introduction

Art is one of the instruments of interaction between culture and space. Within a landscape, artistic creativity generates a multi-layered semiotic structure in which every artifact becomes a sign engaged in a process of constant reinterpretation. It not only documents, contemplates, and reformats landscape reality but also modifies it. Through art, the external appearance of the landscape is altered, its meanings are transformed, specific loci are generated, and a system of aesthetic preferences is formed. It acts as both a recorder and a transformer of the surrounding reality—not only reflecting upon it but also creating a new geocultural reality and shaping cultural landscapes. This encompasses not only artifacts and monuments placed within the landscape but also a way of seeing and perceiving dictated by works of art from archaic times or in any given historical period.

Art creates a cultural landscape that correlates with UNESCO definitions; however, in this context, we will define it

as a cultural phenomenon, with matrix system and cultural codes expressed in signs and symbols directly connected with a territory and/or manifested in some material expression; this system may be interpreted as a text in its wide cultural meaning.

Art manifests two layers of culture. The first is high culture, which subsequently transitions into cultural heritage. This heritage accumulates in the landscape over centuries, is sometimes lost, sometimes eroded, and sometimes revitalized. The second is mass culture, which levels out all previously accumulated meanings or constructs new ones that may or may not fit within the context of the existing heritage.

All of this is applicable to space in the context of artistic creativity, both as a reality and as a concept. A specific case is the interaction of art with landscape and space, and the construction of new metaphysical spaces based on this interaction, existing in both physical and informational geocultural reality.

Cultural heritage is fundamentally important because every genius work opens new cognitive possibilities for humanity as a whole. Therefore, art can be considered a way of apprehending existence. This hypothesis was developed by the renowned Russian philosopher and historian, a researcher of the Roerichs’ work,

Ludmila Shaposhnikova (

2001). According to her thought, the reality of spiritual spaces—of other, higher dimensions—cannot be fully comprehended by humans through scientific methods alone. For this, inspiration and spiritual insight are needed, which are characteristic of saints, ascetics, and genius creators. The works of Leonardo da Vinci, Dante, and other greats brought people sparks of spiritual fire and completely changed the worldview of entire epochs.

Inspiration, which connects the creator to a spiritual reality, is the primary creative force for talented artists, writers, and poets. Accordingly, art acts as an intermediary between three realities. The first is the reality of the spiritual spheres, the collective superconscious, and deep archetypes, which the artist apprehends through inspiration and carries a certain mission—to embody the noumenal in the phenomenal, an abstract idea into a text or image. The second is the reality of the physical world, especially if the artist is a landscapist. The third is the reality of the created artistic space. If we adopt post-structuralist semiotic theory as a working concept, this last reality enters into constant contact with all the others; the moment it is born, it immediately begins to be reinterpreted and rewritten—it is incorporated into the intertext of contemporary culture. A work of art functions as both a subject and an object of interpretation.

On the other hand, the natural landscape itself is an agent of spiritual reality, or at the very least, of its beauty.

Both art and nature make available a notion that ‘through the senses paradoxically one is in the presence of something supersensible.’ This sense of the ineffable, of the broad issue of whether the order of nature has room for humanity and its highest aspirations, underlies popular reverence for the countryside, and appears in philosophical and literary reflections.

This is an interdisciplinary field, and “if human geography had a cultural turn, considering art among a range of artifacts and probing its representational power, including its material effects, the humanities had a complementary spatial turn, charting fields of visual culture and sites of knowledge and power” (

Daniels 2004, p. 435). Within the humanities, a parallel argument suggests that natural landscapes possess a generative potential for culture and art, a phenomenon the art historian Inessa Sviridova termed

culture-genicity and

art-genicity (

Svirida 2007, p. 17)—an innate capacity to foster the development of culture and art. According to this view, the landscape itself “provokes” art into interaction and even influences the quality of that engagement.

Furthermore, both disciplines have investigated the ontological aspects of art’s creative force in space and the formation of a new qualitative and functional unity—that of cultural landscape.

2. Aim

This work does not aim to provide an exhaustive analysis; rather, it is a programmatic article intended to consolidate and outline the various forms of interaction between art and landscape. It seeks to identify the patterns through which art forms cultural codes for perceiving and transforming the landscape, and for creating new landscape images. This serves a dual purpose: to connect diverse, disparate studies and to chart a course for future research within a defined theoretical framework.

Undoubtedly, the theme of interaction between art and landscape is extremely broad, encompassing music, photography, cinema, performance, and more. It is impossible to cover the entire spectrum within a single article; therefore, we will limit our scope to the visual and plastic arts.

3. Materials and Methods

This interdisciplinary study draws on the discourses of the humanities, geography, anthropology, and social sciences. A review of the literature and various perspectives on the interaction between art and space opens new possibilities for classifying and typologizing the diverse modes of this interaction, which operates in both directions. The cultural landscape concept was used as a theoretical framework. The article employs a semiotic research method, which involves interpreting the cultural landscape as a sign system. Comparative-historical and interpretative methods of analysis were also applied.

This study provides a comprehensive analysis of the interaction between art and landscape, synthesizing a considerable volume of theoretical and applied research from classical to contemporary sources.

4. Related Works

The study of art and landscape interaction is inextricably linked to the theory of the cultural landscape and is rarely considered in isolation from the broader problematics of culture-space relations. At the dawn of the 20th century, the fields that would later be termed “cultural landscape” and “landscape history” were shaped by two related traditions: historical geography and art history.

In geography, the most influential figure was

Carl O. Sauer (

1925), who demonstrated the role of human culture in shaping landscapes, thereby laying the methodological foundation for studying landscape as a cultural construct. It is less widely known that several years before Sauer, in 1915, the Russian scholar

Lev Berg (

1915) expressed a strikingly similar idea. However, the Great October Socialist Revolution soon intervened, steering Soviet science onto a Marxist path, and this concept did not re-enter Russian academic discourse until after Perestroika.

The concept developed further after the Second World War. In the British tradition, “landscape history” flourished through the work of local historians and geographers. A seminal example is W. G. Hoskins’s classic monograph,

The Making of the English Landscape (

Hoskins 1955), which framed the landscape as an archive of human activity and social history—an approach that profoundly influenced local and national landscape studies.

The mid-20th century witnessed a strengthening humanistic turn, as scholars began to treat landscape as a phenomenon of perception and meaning. In Anglo-American humanistic geography, the works of Yi-Fu Tuan became central, shifting the focus from material configuration to the sensory and experiential dimension of place (

Tuan 1977;

Tuan 1990). This shift strongly influenced art historians studying the visual representation of space. Culture itself came to be seen as a geographical reality (

Spencer and Thomas 1969), coinciding with a practical turn that saw the rise of land art and site-specific art, movements accompanied by robust theoretical developments.

From the 1970s to the 1990s, the interaction of culture and space became a topic in the humanities.

Key influences were theories of the

production of space (Lefebvre), the

practice of everyday life (de Certeau), and

spatial semiotics.

Lefebvre (

1991) conceptualized space as a social product and process, while

de Certeau (

1984,

1988) highlighted the practices of “traveling” through and “using” space as a source of meaning. These frameworks enabled scholars to analyze how visual practices—from landscape painting to monumental art and photography—participate in constructing socio-spatial relations.

Within the art historical tradition, Denis Cosgrove made a pivotal contribution by positioning landscape as a

symbolic form reflective of social formations (

Cosgrove 1998;

Cosgrove and Daniels 1988). His classic work on the

symbolic landscape and the genesis of a

landscape way of seeing demonstrated how visual practices (perspective, panorama, painting) function in concert with politics, property, and power. Concurrently, in Anglo-American cultural history, Simon Schama proposed a

mnemonic and

narrative perspective, exploring the deep interconnections between memory, culture, and the terrestrial surface (

Schama 1996).

From the 1990s onward, “landscape” became the focus of a multi-field dialogue, integrating poststructuralist and postcolonial critiques, feminist readings (e.g.,

Doreen Massey (

1994) on space and gender), and investigations into the visual politics of landscape, exemplified by W. J. T. Mitchell’s seminal collection

Landscape and Power (

Mitchell 1994). These approaches accentuated the political, gendered, and colonial dimensions of landscape, revealing that the representation of “place” is invariably entangled with power and ideology.

Consequently, artistic practices—such as landscape painting, photography, cinema, landscape architecture, and site-specific projects—began to be analyzed not as passive reflections, but as active co-authors in the creation of a place’s meaning. Within the environmental humanities, interest has grown at the intersection of aesthetics, environmental perception, and historical-social practices. This has given rise to interdisciplinary research exploring how artistic practices shape the ecological imagination and inform political relationships to the landscape in the Anthropocene. A synthesis of visual culture, ecology, and critical spatial theory has coalesced in the 21st century and continues to evolve dynamically.

Thus, the historical trajectory of studying culture-landscape interaction in Western humanities can be summarized as a transition: (1) from empirical-descriptive and historical-geographical analyses; (2) to humanistic and phenomenological readings of place; (3) to cultural-theoretical and political analyses of spatial form; and finally, (4) to interdisciplinary studies integrating visual culture, ecology, and critical theory. This evolution mirrors a broader shift in the humanities from description to critique, from the local to the global, and from formal analysis to the incorporation of issues concerning power, identity, and ecology.

A more focused examination of the interaction between art and landscape specifically, however, reveals a smaller body of work. The most conceptual study in this vein is unfortunately little known in the Anglophone world, as it was published in Russian: geographer Yuri Vedenin’s

Essays on the Geography of Art (

Vedenin 1997). Vedenin’s work analyzed the influence of natural conditions on art and the spatial distribution of artistic trends and styles. Around the same time, Western scholarship also began to engage with the interpretation of landscape imagery in art (

Appleton 1990;

Bourassa 1991;

Fitter 1995;

Miles 1997) and the problem of visuality in this context (

Jakle 1987). This was further augmented by recent studies on the semantics of color in landscape (

Griber 2024;

Lavrenova 2023).

The contemporary paradigm involves a synthesis of methodologies—including visual analysis of artworks, archival landscape history, spatial theory, and environmental reflection—to understand fully how culture (specifically art) shapes, interprets, and transforms landscapes amid global social and ecological change. At the turn of the 21st century, a consolidation of theoretical tools (visual culture, politics of representation, ecology, digital practices) occurred, paving the way for current interdisciplinary research that integrates artistic analysis with concerns for landscape conservation and perception.

5. The Concept of Cultural Landscape in the Context of Art

A cultural landscape is simultaneously holistic and differentiated, organized on pragmatic, semantic, and symbolic levels. Indeed, even a relatively pristine landscape where certain features have been named (toponyms) can already be considered cultural. For instance, the summit of Mount Kanchenjunga, first summited in 1955, has for centuries been part of the cultural landscape of the Lepcha people, who believe it is the dwelling place of their gods.

Culture “animates” and “ensouls” the landscape. As Simon Schama argues in Landscape and Memory,

Landscapes are culture before they are nature <….> once a certain idea of landscape, a myth, a vision, establishes itself in an actual place, it has a peculiar way of muddling categories, of making metaphors more real than their referents; of becoming, in fact, part of the scenery.

The transformation of space by culture is rooted in socio-cultural practices. However, once structural and architectural elements become established and anchored in space, they begin to regulate those very practices (

Harvey 1996). Such localized, mastered, and structured cultural landscapes readily fit the definition of “place,” standing in contrast to abstract, undifferentiated “space” (

Relph 1976;

Tuan 1977). An ancient menhir in the Central Asian deserts, for example, persists through centuries and shifting religions as a meaningful landmark. Offerings are still made there, even though the meanings imbued in these practices are different from those intended by its original builders.

This demonstrates how meanings created by culture and art flow ceaselessly into the landscape and back again, creating an endless cycle—

a perpetual process of semiosis. While postmodern tradition commonly labels this phenomenon “intertext” (

Kristeva 1980), it seems time to adopt a new, more capacious metaphor to fully express the richness of this interaction.

The cultural landscape incorporates material and spiritual culture on equal footing, encompassing both contemporary (traditional and innovative) elements and cultural heritage. This includes toponyms, artifacts, and human-made landscape forms that act as markers of historical events. In other words, the landscape accumulates and transmits a potential of intellectual and spiritual energy. Within this process, art generates both tangible and intangible heritage—including symbols and signs—and participates in the ongoing process of cultural genesis, which is aimed at transforming, comprehending, and signifying the environment. As a result, some culturally transformed landscapes can themselves function as cultural codes (

Gruffudd et al. 1991). The Church of the Intercession on the Nerl, for example—not just the church itself, but the entire landscape—serves as a cultural code and an aesthetic standard for Russian Orthodox culture (

Figure 1).

The creative power of culture, which transforms a natural landscape into a cultural one, manifests in two types of activity: the pragmatic (farmland, industrial facilities, housing, infrastructure) and the symbolic (all forms of art, including artistic images of the landscape). It is this second, symbolic form that we will now explore in detail, aiming to encompass the full spectrum of interactions between landscape and the plastic arts.

6. Landscape and Artifacts

The space of a cultural landscape, its structure is constructed by art primarily through its direct modification—this includes architectural forms, gardens, monuments, installations, etc. It is hard to find a city or town without at least one sculptural form and/or a full-scale mural, or graffiti at the very least. The landscape changes visually, semantically, and structurally. As the contemporary semiotician

Leonid Tchertov (

2019) notes, a sequential organization of space into texts occurs, ones that are meaningful and structured according to specific cultural norms.

With the creation of new artifacts, new centers and points of attraction emerge, along with new pathways and main thoroughfares. This can be a temporary change—for example, an installation by a fashionable artist that, for the duration of its existence, alters the flow of human traffic in a given landscape, generating new meanings and phrases that integrate into the pre-existing spatial-semantic structure of the cultural landscape. That said, this can be a genuinely interesting work or a gaudy sculpture that sparks numerous debates; the removal of such an artifact from the landscape will likewise be influenced by public opinion. An example is the sculpture

Big Clay #4 (2013–2014) by Swiss artist Urs Fischer (

Figure 2), which, according to his intent, presents the act of creation, formation, and transformation. It was exhibited in New York (2015) and Florence (2017), and from 2021 to 2025 was located in the center of Moscow on Bolotnaya Embankment, in front of the entrance to a contemporary art center, before being moved to a less pretentious location. Situated in the city’s historic center, the sculpture spawned emotional tension through its incongruity with the architectural style of the surrounding landscape and provoked heated discussions.

- 2.

Art introduces the aesthetics of a landscape. With its centuries-old history, art shapes a particular optics that is embedded in the cultural background of a person admiring nature (

Daniels 1994;

Green 1999). Even in the Romantic era, it was said that all people possess an innate sense of the beautiful, but later this theory was amended to indicate the social nature of aesthetic experiences.

The understanding of nature and its beauty depends on our construction of order and purpose. At present, natural beauty is so riddled with conceptions derived from painting and poetry that landscape refers ambiguously to parts of nature and representations of nature in paintings, photographs, and film.

- 2.1.

Art has shaped numerous visual images of landscapes, which influence our perception by creating an effect of recognition, comparison, and interpretation within a context. On the one hand, this leads to the formation of certain standards; on the other hand, our color perception is shaped through painting.

Viewing a cathedral in a rural setting, do we see what is before us or, once having seen Constable’s painting of Salisbury Cathedral, is our view more like a transparency through which we dimly perceive the painted cathedral? How can we avoid the shadow of Monet’s haystacks when we observe the mounds of hay on a fall drive in the countryside or regard the Houses of Parliament across the Thames through the fog or at sunset without recalling his imagery? Is it possible to view a great, dramatic tree without the influence of van Ruysdael? We can easily mention an endless stream of paintings whose images, once seen, populate the actual landscapes we experience (

Berleant 2013) (

Figure 3).

Although a vast number of people in this world have never seen a Monet painting, or even its reproductions or photographs, this does not prevent them from admiring a sunset, perceiving it as it is, perhaps actualizing that very innate sense of the beautiful. Meanwhile, a person “corrupted” by culture will see blue or purple in the shadows, and this will depend on their preferences for painting styles or on what they were taught in art school. That is, our color perception is a function of our aesthetic education and cultural baggage. Interestingly, the latter applies specifically to landscape, as no one would, for example, look for or see the blue, green, and purple shades on a girl’s face that were introduced into portrait painting by the Impressionists.

- 2.2.

The geometry of a landscape also becomes a text. As

Leonid Tchertov (

1999, p. 93) argued, this process presupposes first the identification of the spatial elements and structures that transmit meanings, second the establishment of norms for their interpretation, and third the determination of the conditions for their use by interpreters. In this way, the syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic rules are established, collectively forming what can be termed a “language”—following one of the founders of semiotics

Charles Morris (

1983)—or a “spatial code.”

The aesthetic perception induced by works of painting ranks the elements of landscape morphology, allowing us to interpret the plastic forms of the landscape as visual codes available for reading. These forms, shaped by geology, water, or wind erosion, developed naturally, obeying immutable physical laws, but within a cultural context, they all acquire meanings that are very loosely connected to their genesis. Natural geometry is transformed into a semantic structure.

Lines, ubiquitous in the landscape, strongly structure space and evoke powerful emotions: the horizontal signifies calm, balance, serenity, melancholy, a sense of one’s own solitude, and longing; it is the plain, the steppe, the infinitely distant. The vertical conveys nobility, supersensibility, and pride, which can express solitude but also humility, as one feels so small beside it… It is religious Gothic, and also masculinity, symbolized by a tree. The oblique generates unease, tension, difficulty, but also search, and thus—dynamism. A curve, if gentle, evokes tenderness—a tenderness full of resilience—but if it is random, it signifies the unfinished, mystery, and dream.

Thus, the color and geometry of a landscape are perceived according to cultural codes created by art.

- 3.

Fashion, which is dictated by the aesthetic preferences of an era, also influences the transformation of space through art. Fashion, in turn, is shaped by the artistic styles and iconic works of its time, including those painted on canvas. A dominant style largely dictates the plastic and color solutions that are later implemented in the landscape, even to the point of repainting or reconstructing architectural structures. Throughout history, many buildings, churches, and cathedrals have undergone such changes and are now perceived in their most recent, altered form. Sometimes these modifications can take on grotesque expressions, as seen in Russia during the 1990s with the “new Russian style” renovations of 17th-century churches—for instance, painting a white-stone frieze in orange and black. The visual dominant that defines the landscape’s overall style is altered; the key color accent, which is simultaneously a semantic and spiritual center and a point of attraction for human flow, shifts from the concise color aesthetic of temple architecture to popular kitsch.

Fashion influences landscape design, for example, in the construction of gardens.

Dmitry Likhachev (

1998) conceptualizes a garden within the “aesthetic climate” of its era as an artificial micro-landscape, where natural components—topography, types of vegetation—are seen as filled with meanings and significance and used as construction materials to create a new, holistic picture. A garden established in this way, in turn, “educates” the visitor, shaping their system of aesthetic preferences. “Gardens can serve spiritual or practical ends, offer places for retreat or arenas for activity, stoke pride, yield profit, or serve the public good” (

Ross 1993, p. 159) (

Figure 4).

The late 20th-century fashion for ecological gardens with meaning led to a thoughtful combination of form and endemic plants. In the 21st century, this has been supplemented by the bird’s-eye view, popularized by aerial photography and drones. For instance, Alan Sonfist planted vegetation in Westphalia in the shape of a falcon (2004), mimicking a Celtic hillfort, in an attempt to revive the geoglyphs of the ancient world, but with an environmental slant—using native plants (

Figure 5).

Conversely, following fashion, abstraction and emptiness or absence can become tools for the landscape designer. “The strategy of absenting may in one situation be engaged to reduce nature’s complexity, but in another be aimed to support such complexity, by excluding cultural elements deemed detrimental. Both approaches have their place” (

Dee 2012, p. 169).

On a mass scale, fashion influences the design of private garden plots, including the use of small-form garden sculpture. In its contemporary variant, private landscape design predominantly employs kitsch sculpture, which, alas, shapes the stylistic preferences of the generation growing up on these parcels of land.

Concurrently, theorists are developing a framework to explain the new relationships between vision, materiality, and geological time. This has created a distinct scholarly challenge: how to analyze a work that is both a geographical entity and an artifact documented through photography, film, or catalogues. In his foundational text, land art theorist and practitioner Robert Smithson deconstructs the idea of “place” in this context.

[He] developed the Non-Site, which in a physical way contains the disruption of the site. The container is in a sense a fragment itself, something that could be called a three-dimensional map. Without appeal to “gestalts” or “anti-form,” it actually exists as a fragment of a greater fragmentation. It is a three-dimensional perspective that has broken away from the whole, while containing the lack of its own containment. There are no mysteries in these vestiges, no traces of an end or· a beginning.

- 4.

Another way art constructs space is by forming distinct loci within the landscape—places that seem detached from everyday life, possessing their own unique space-time. Nevertheless, it is precisely these places that are most often responsible for the formation of cultural identity (

Nora 1989). Museums and heritage sites, for example, are heterotopic spaces that attempt to document and represent the reality of other epochs and reconstruct a cultural landscape. Art museums gather the finest examples of art, which for centuries have influenced a culture’s mentality and its aesthetic dominants. These “reservations” of cultural heritage and high style have their own specific localization in space, forming iconic nodes in a city’s cultural landscape.

Memorial house-museums, even in the absence of authentic artifacts that belonged to a particular great figure, are filled with art objects and everyday items from the corresponding historical period to reconstruct the era’s spirit. In heritage museums, landscape architects collaborate with scholars; for example, at the Borodino Field, visual lines corresponding to the time of the famous 1812 battle between Napoleonic and Russian armies are being recreated, and historical land-use practices are being restored in several areas. In this way, fragments of historical time are generated within real space-time, shaped by the creative will of their reconstructors, curators, and artists—the authors of the exhibition.

Memorial spaces are connected to the memory of local or national historical events and are particularly “tempting” for artists and architects. Monuments and/or entire architectural complexes often emerge in places that need to be anchored in public memory and are linked to national identity. Such projects of national significance are typically curated and sponsored by the state. A striking example of such a landmark complex is the Mamayev Kurgan in Volgograd (Russia), where, through the means of art, a symbolic landscape emerged on the historic site of the Battle of Stalingrad (17 July 1942 to 2 February 1943), one that holds immense significance in Soviet and post-Soviet culture (

Figure 6).

Landscapes of memory, like all cultural landscapes, have a normative power. They are important conduits for not just giving voice to certain visions of history but casting legitimacy upon them—a way of ordering and controlling the public meaning of the past.

In memorial sites where sculptors and architects have created symbolic landscapes, the individual is, in theory, supposed to connect with a great or terrible past and experience spiritual catharsis. However, any text and any symbol can only be read if the reader knows and understands its language. A contemporary cultural shift has led to the meaning of historical and memorial landscapes being either eroded or distorted, and this misunderstanding is broadcast through photographs shared in internet and media spaces. This very discrepancy of meanings, in turn, becomes a subject for art, which produces a new intertext. Israeli artist Shahak Shapira’s project

Yolocaust (

Figure 7) used material from Instagram. He combined playful contemporary selfies taken at one of the most tragic sites in the world—the Holocaust Memorial—with documentary photographs from concentration camps. The original captions provided by the authors of the selfies in the comments reveal a catastrophic cultural gap between generations.

- 5.

Today, the interplay between art and landscape is characterized by its multidisciplinary nature. The analysis of artistic practices now extends beyond painting and sculpture to include installations, eco-art, and digital and performative projects. Current research explores artistic responses to climate change—both as a theme and a method, incorporating changing natural processes into the works themselves—as well as issues of access and tourism (visitors’ impact on land art objects) and the preservation of site-specific art (

Gaiger 2009;

Kaye 2000). Twenty-first-century scholarship has advanced both empirical methods, such as the archiving of visual material, and theoretical frameworks, including environmental aesthetics and the aesthetics of the Anthropocene. Contemporary studies frequently combine visual analysis with an examination of the works’ material and ecological impacts.

Concurrently, the creation and analysis of these objects give rise to new mythologies that inscribe themselves upon the landscape. A prime example is the metal monolith “discovered” in the Utah desert, which sparked debates about its potential extraterrestrial origin before being attributed to the artist John McCracken (

Figure 8). Subsequent refutations of this attribution only served to launch the mythology into a new chapter.

7. Pictural Landscape Images

Space is modified at the informational level through the generation, reproduction, and new reconstruction of landscape images and the formation of an “idea of the landscape,” which is shaped by different types and means of art, as well as by broader cultural and societal trends (

Cosgrove 1998). The interplay between locality, place, and artistic practice has been a subject of study since the late 19th century. For instance, the critic

Philip Gilbert Hamerton (

1871) was already contemplating landscape painting from life and from memory, the use of photography, and notions of transcendence in art. A century later, these same questions resurface within the framework of the cultural landscape (

Rees 1973;

Cosgrove 1998;

Howard 1984), examined both as an interactive medium (

Lippard 1997) and as a mirror of social issues (

Barrell 1980). The artistic space of a work is a kind of mnemonic and creative program that develops according to its own laws and influences the external world through its specific optics, meanings, and models.

Art perceives and represents the landscape primarily in three ways, employing narrative and symbolic interpretation and description of the world, as well as the creation of a spatial ontology based on landscape images.

The first way is narrative—a direct account where the artist or writer sees themselves as a documentarian, capturing what they see as closely as possible to reality, while striving to abstain from imposing additional meanings. In literature, narrative is usually augmented by emotional color, composed through the use of varied vocabulary. In painting, it is possible to eliminate the emotional element if artists work from photographs and strive to achieve maximum impartial accuracy. In the age of the internet and Instagram, such documentary landscapes are losing their significance, as high-quality artistic photography is capable of capturing a landscape more accurately and impressively. The ideal of the genre—the “landscape with a mood” (

Figure 9)—is now achieved through technical means in the skilled hands of photo artists, which is particularly evident in the works of nominees and winners of various international landscape photography competitions.

- 2.

The second method is the pictorial interpretation and/or imaginative elaboration of a landscape, depicting it in a symbolic key. Various artistic means can be used for this purpose.

One of the oldest sensibilities of an artist is the interpretation that nature is filled with meaning emanating from God, along with a corresponding eschatology.

Literary texts are among the richest in generating meaning; they become instruments for understanding the processes and phenomena occurring in geocultural space. “Besides their communicative function, texts also perform a meaning-generating function, acting not as a passive package for a pre-given meaning, but as

a generator of meanings” (

Lotman 2002, p. 189; author’s translation). The texts of artistic works fully act as generators of meanings for the cultural landscape. The existence of texts genetically linked to a particular place implies that the landscape, as a semiotic system, is also built on the principle of a “mosaic of citations,” as a product of the absorption of other texts into the landscape’s informational component; when this intertext is read, it generates new texts.

In painting, the meaning usually emerges indirectly, through an already established language of visual means. Some painters, while depicting a landscape in a realistic manner, use the shifted perspective method, presenting the landscape from an elevated viewpoint. Not only does this method alter its visual characteristics—it also changes its semantic dominants and content. The result is a spatial and semantic unfolding of the landscape, a revelation of meanings, and an enhancement of their visibility and significance. Furthermore, through the painter’s creative will, visual and semantic dominants can be highlighted or exposed—thereby granting the landscape a semantic integrity that is lacking in reality due to the fragmentation of visual planes and lines.

Color solutions can be used for the same purposes. This technique was employed, for example, by Nicholas and Svetoslav Roerichs and other Symbolist artists, with the result that even their sketch studies are perceived as symbolic. This is because the color palette, with its unreal combination of colors, transports the depicted landscape into a world of other dimensions, moving the real geographical space beyond the boundaries of the three-dimensional world.

- 3.

A crucial function of art is its participation in forming the ontology of sacred spaces.

Art represents holy sites, which by definition are key nodal points of meaning in the cultural landscape. They are part of a cultural and spiritual heritage that many wish to connect with. However, if a site is located far from well-trodden tourist paths, or if it is a natural landscape imbued with sacred meaning for local cultures, not everyone can have physical access to it. For example, Deni-Der, the Altai Lake of Spirits, captured in a painting by the renowned Altai artist Grigory Choros-Gurkin, transitioned from a local sacred site to become part of Russian and global artistic culture; this pictorial image contains both the mystery and sanctity inherent in the toponym, as well as the beauty of the landscape.

By depicting the holy places of the Himalayas (

McCannon 2000), Nicholas Roerich incorporated the spiritual culture of India and Tibet into the Russian context, making these places and their inherent meanings part of the Russian mentality and authenticity. Thus, loci situated in a different geographical and cultural space are adapted until they become familiar, almost “one’s own” (

Figure 10).

Sacred places, cultivated by culture, also find potent expression and symbolic resonance in art—exemplified by the recognizable spiritual image of the Russian North, where Orthodox believers traditionally sought solace in monasteries, as captured in the paintings of Mikhail Nesterov (

Gleason 2000).

When it engages in fantasy, art attempts to construct its own spatial ontology. Fantastic literary works and paintings might seem to lead away from reality. Yet, the fantastical opposition remains inextricably linked to reality. Artists build upon the real patterns of earthly existence, able to alter only a few things—such as the plasticity and weight of objects—but still within the same framework of the law of gravity and the laws of visual perception in a three-dimensional world. Imagined landscapes cannot transcend the bounds of earthly physical reality. No matter how virtual the works of M.C. Escher or some pieces by Salvador Dalí may seem, the same principle applies here as in the creation of mythological and fantastic animals (dragons, harpies, etc.): parts of the known world are used and arbitrarily combined, but nothing fundamentally new has been created throughout the entire history of world culture.

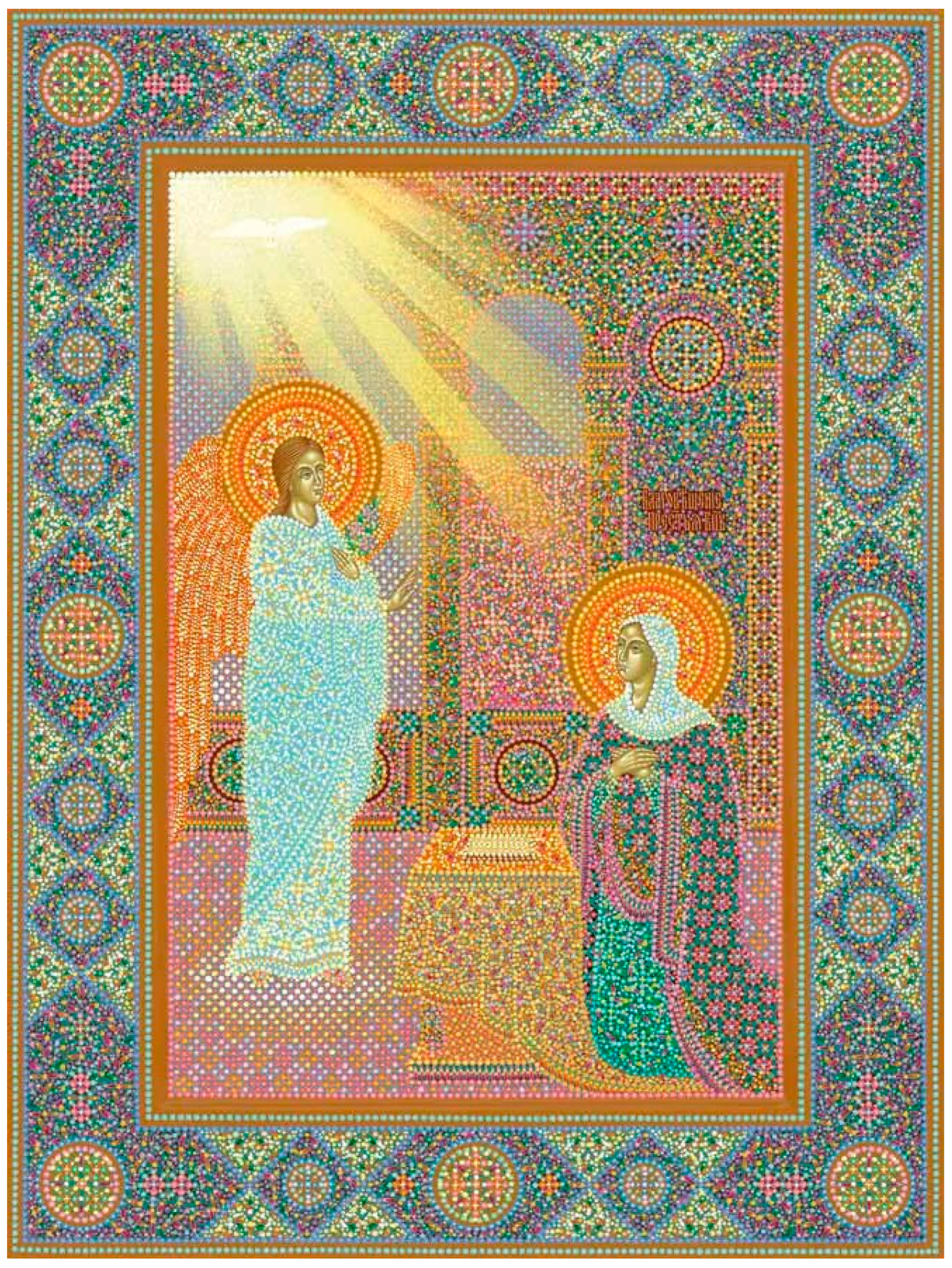

In painting, there are also works that are not fantastical but “testimonial,” where color becomes a means of “narratively” describing a spiritual space apprehended through inspiration. In the later stage of his career, Svetoslav Roerich used color to depict the light of other worlds, without delving into their geometry. The early 21st-century icon painter Yuri Kuznetsov, using his “pearl-like technique” (a combination of pinpoint dots of paint—sometimes of opposite color), represented the spiritual light corresponding to a particular iconographic image. In this approach, the special geometry of the icon’s artistic space (reverse perspective) is replaced by a color wave, which is also capable of shaping the perception of a landscape—for instance, interpreting the colors of a sunset as a glow of the spiritual world (

Figure 11 and

Figure 12).

Every new artistic image of space immediately enters the informational layer of world culture and contributes to the formation of stereotypes for perceiving landscapes and comprehending space as such.

8. Conclusions

In summary, this study aims not to exhaust the theme of art-landscape interaction but to systematically classify its methods, building upon existing scholarship. The vast diversity of art’s influence on the landscape can be distilled into two fundamental aspects: the material and the immaterial (

Figure 13).

Art provides the possibilities for the defragmentation of the world and its reassembly. The creative act, in most cases, is linked to inspiration—a holistic “flow” of consciousness transcending the three-dimensional world. In contemporary art, with its multitude of non-dominant styles, art historians may attempt to synthesize this diversity into a cohesive worldview, for instance, as a “virtual museum” project.

Consequently, in its relationship with space, art functions as its reconstructor. Through the artistic means, specific landscapes are transformed to varying degrees—with architectural structures, monuments, installations, and graffiti changing their structure and meaning. Museums and heritage sites become loci of a different temporality, sequestered from the mundane flow of daily life. On an informational level, art transforms the world by generating landscape imagery, reshaping perspectives in painted works, and forging new meanings via literary description. Furthermore, art establishes the codes for reading the landscape as a text, in which visual characteristics (verticals, horizontals, color accents) are deciphered through the semantic system created by art.

Art as a Mediator Between Realities. Art serves as an intermediary between the spiritual, material, and symbolic spheres, bridging the sensuously perceptible and the metaphysical. Through inspiration and the creative act, the artist translates intangible meanings into visual images, transforming the abstract into the tangible and the invisible into the visible. Thus, art constitutes a unique mode of apprehending existence—one that remains inaccessible to purely scientific methodologies.

The Construction of Space Through Artistic Means. Art does not merely reflect the landscape; it actively participates in its creation. Architecture, monumental sculpture, installations, and other artistic objects structure space, establishing new centers, routes, and visual dominants. Each artistic artifact becomes an element within a semiotic structure that alters the environment’s topology and semantic organization.

The Formation of Landscape Aesthetics. The aesthetic perception of both nature and the city is shaped under the influence of art. Pictorial and literary images define a specific “optics” of vision, generating culturally conditioned models of perception. As a result, the landscape is perceived not as a natural phenomenon, but as an intertext, saturated with artistic quotations and references.

Artistic Styles and Fashion as Factors of Visual Transformation. Historical shifts in spatial aesthetics depend on artistic movements and the dominant visual codes of an era. Fashion, which is itself rooted in art, dictates color and plastic solutions in architecture, landscape gardening, and urban design. This confirms the thesis of the interconnection between artistic taste and the morphology of the cultural landscape.

Art as Custodian and Constructor of Cultural Memory. Museums, heritage sites, memorial complexes, and monuments create “reservations of memory” where symbolic landscapes of national identity are formed. Art not only preserves memory but also continuously reinterprets it, transforming historical space into a sign system imbued with normative power.

The Informational Construction of Landscape. Art also transforms space at the level of representation—through painting, photography, cinema, and literature. Once integrated into cultural discourse, every artistic image alters the perception of the actual landscape, establishing new visual and semantic constants. Art shapes collective “mental maps” for perceiving space, influencing the collective imaginary.

The Duality of Art in the Context of Tradition and Innovation. Artistic space mediates the sacred and the profane, the elite and the popular. This duality generates a field for dialogue between different levels of culture, where tradition and contemporaneity coexist in a dynamic equilibrium.

Art as a Form of Semiotic Ordering of the World. Art creates a “language of space”—a system of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic rules through which the landscape becomes a text. In this sense, art functions as a mechanism for the cultural encoding of space and its perpetual reconstruction.

Art is not a passive reflection but an active agent in the transformation of space. It creates a system of meanings that forms the cultural landscape as a text, where every element—an artifact, a symbol, or a visual accent—participates in the generation of new meanings. Thus, artistic creativity operates not merely as an aesthetic endeavor but as a cognitive and ontological practice that facilitates a dialogue between humanity, nature, and culture. Culture, aided by art, produces a qualitatively distinct world, filled with meanings and symbols. The landscape, structured and textualized by culture, is read and rewritten by artists and writers and possesses the properties of an intertext.

13