Spatial Optimization of Primary School Campuses from the Perspective of Children’s Emotional Behavior: A Deep Learning and Machine Learning Approach

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Campus and Students’ Mental Health

1.2. Campus Basic Theory

1.3. Research on School Space in Primary Schools

- (i)

- Study areas: library, study classroom, art classroom, multifunctional classroom, and lecture hall.

- (ii)

- Living and leisure areas: restroom, cafeteria, atrium, auxiliary area.

- (iii)

- Activity areas: sports field, gallery space, planting garden, stairwell, and shared activity space.

- (iv)

- External spaces include building facades (inner courtyards, activity areas, athletic areas, elevated areas, outdoor character areas), enclosure components, utilities, exercise paths, and temporary features [93].

- (i)

- Perspective: This study adopts a user-centered approach, emphasizing children’s emotional development and behavioral performance within the school environment. This perspective addresses the paucity of systematic research on elementary school campuses that explicitly considers children’s experiences [94]. By integrating spatial elements, spatial types, and color characteristics from the objective physical environment with students’ subjective emotional perceptions and behavioral patterns, the study constructs a comprehensive influence mechanism model [95]. This approach overcomes the limitations of prior studies that examined these factors in isolation.

- (ii)

- Methodology: The study employs deep learning and machine learning techniques [96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103] to establish relational models linking emotion and behavior. This approach provides empirical support and practical guidance for campus space design, enhancing the accuracy and applicability of the findings.

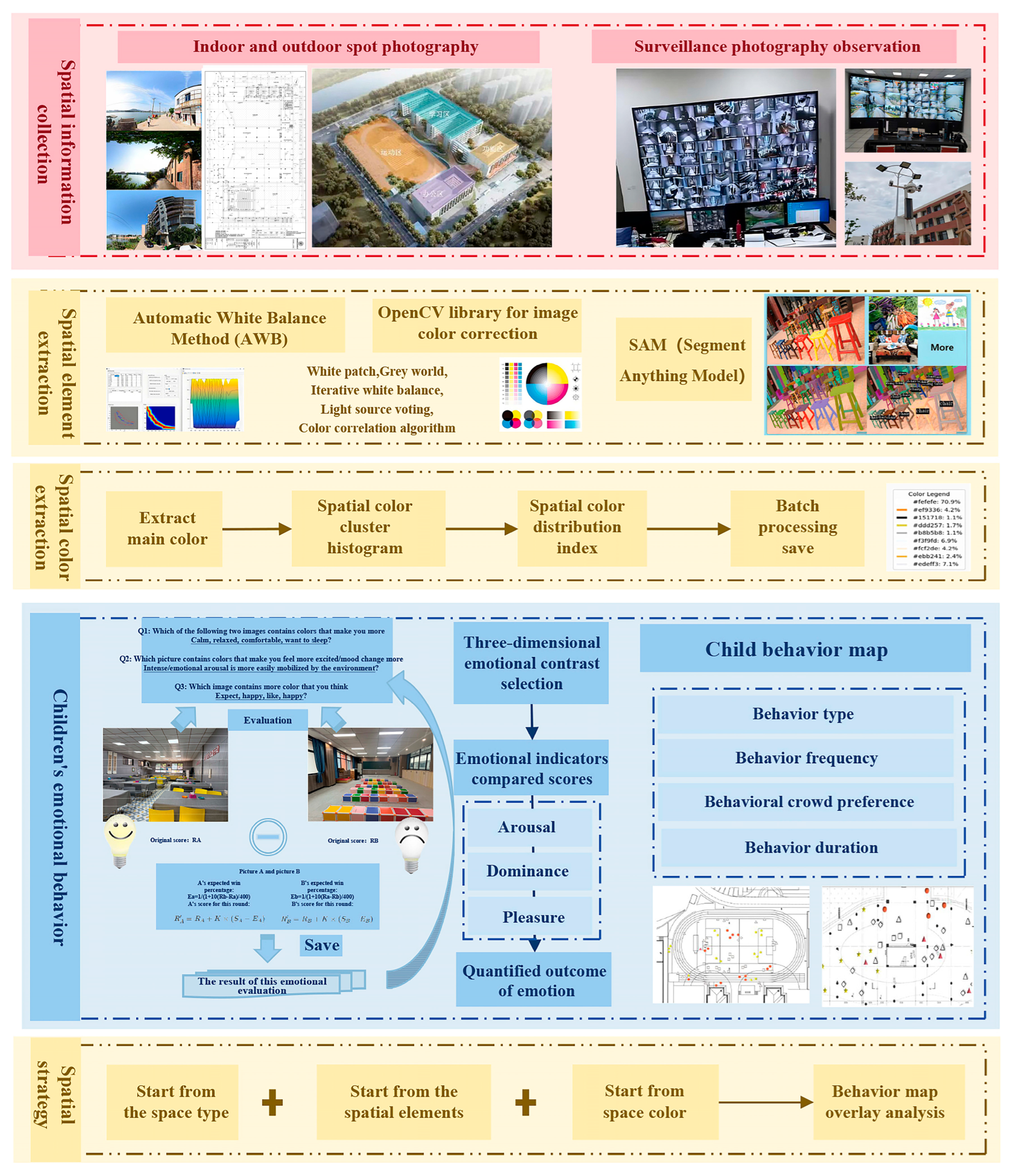

2. Methods

2.1. Date

2.2. Framework

2.3. Methodology

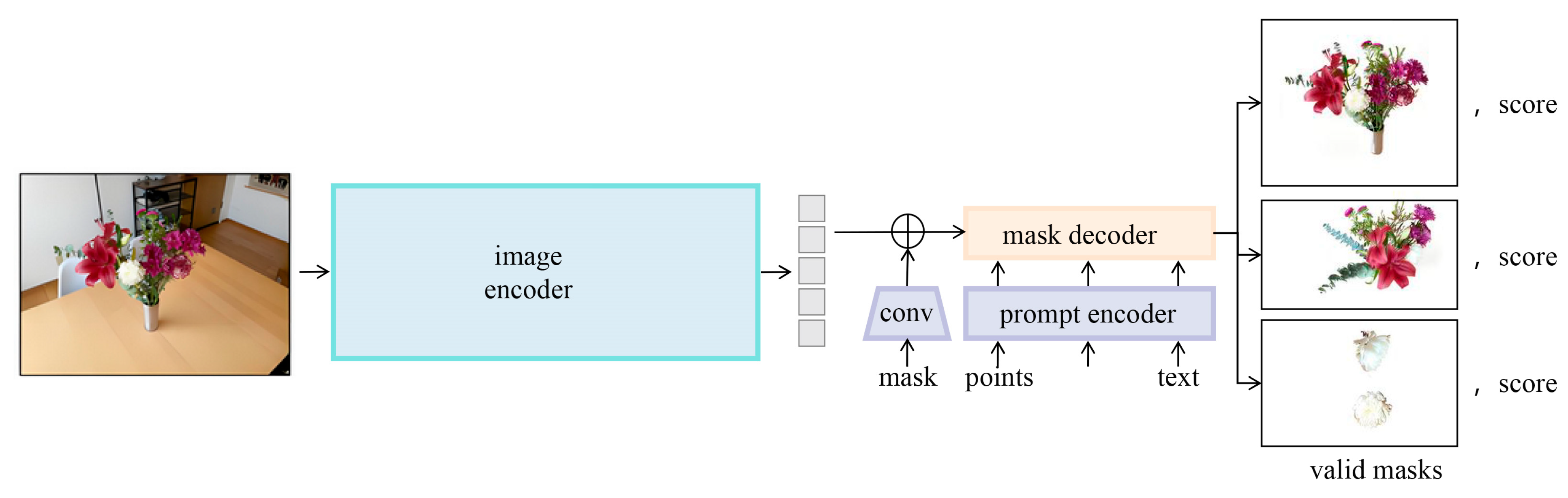

- (1)

- Semantic segmentation based on deep learning

- (2)

- Machine Learning-Based Modeling of Influence Mechanisms

- (3)

- Behavioral map observation based on video images

3. Results

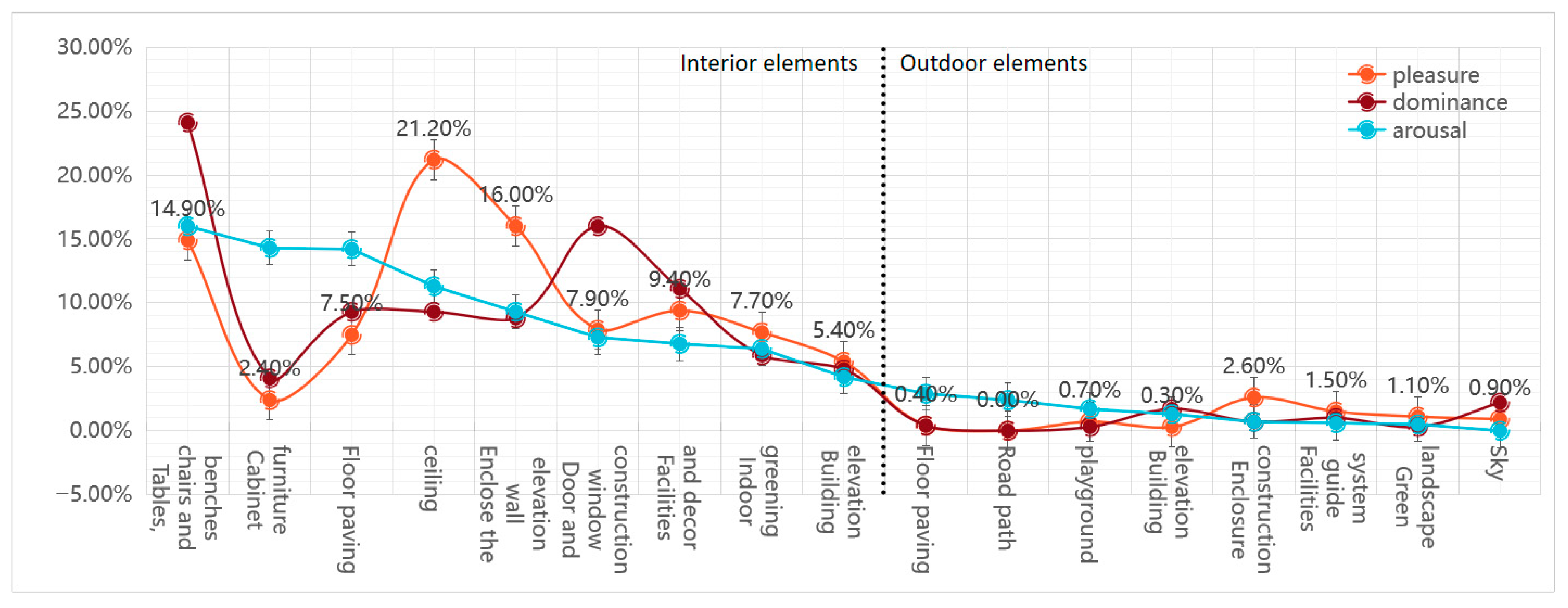

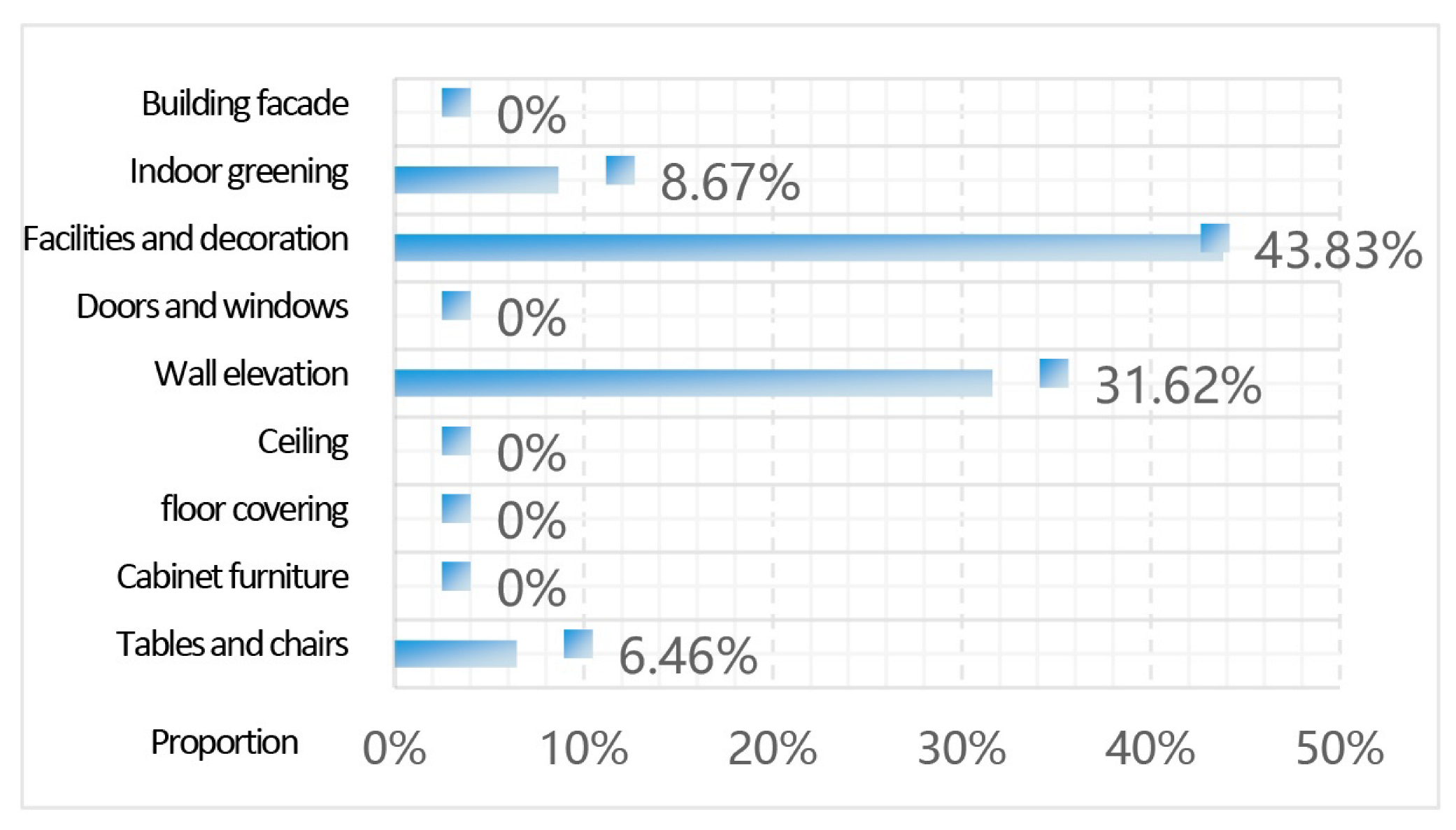

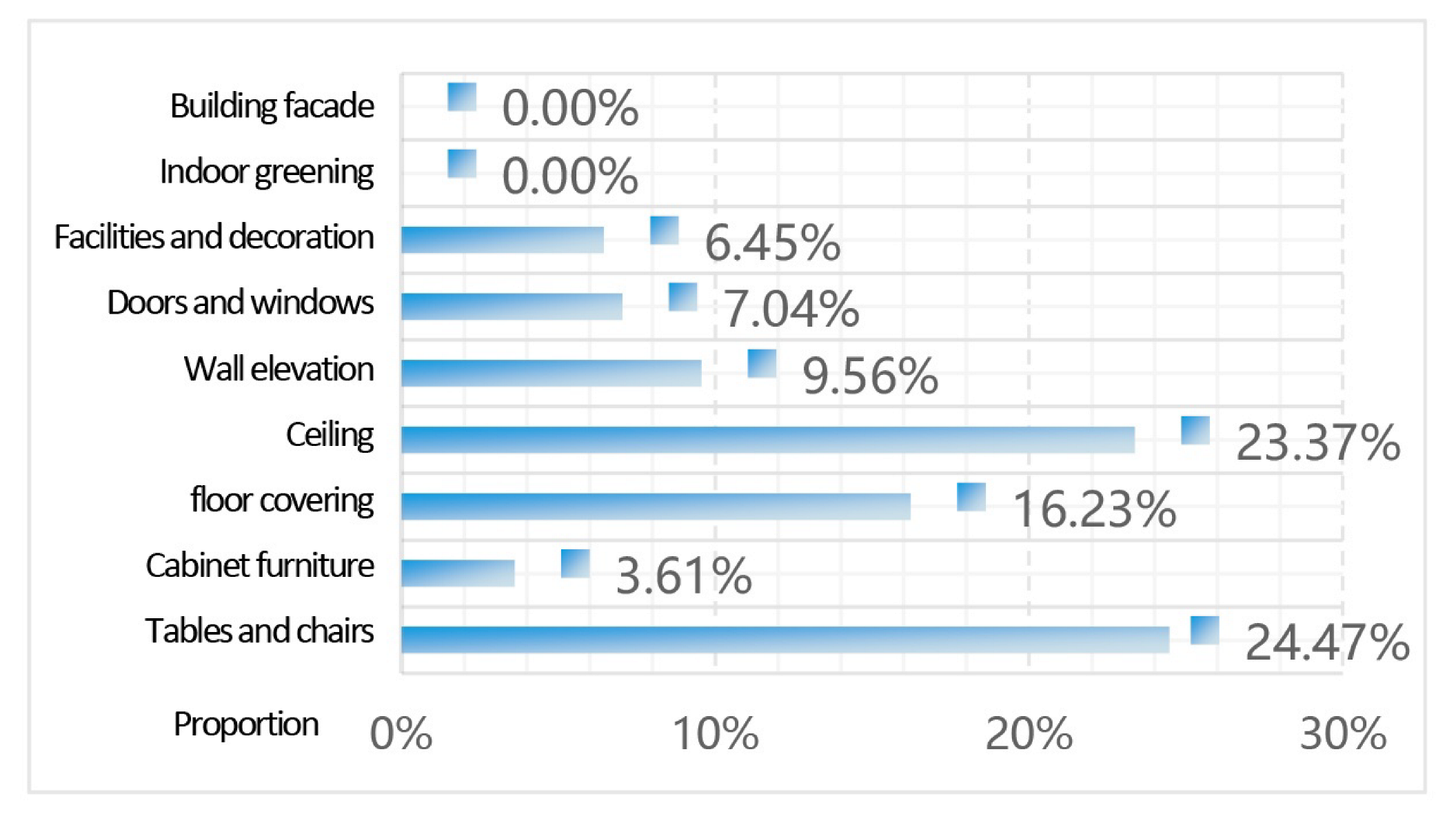

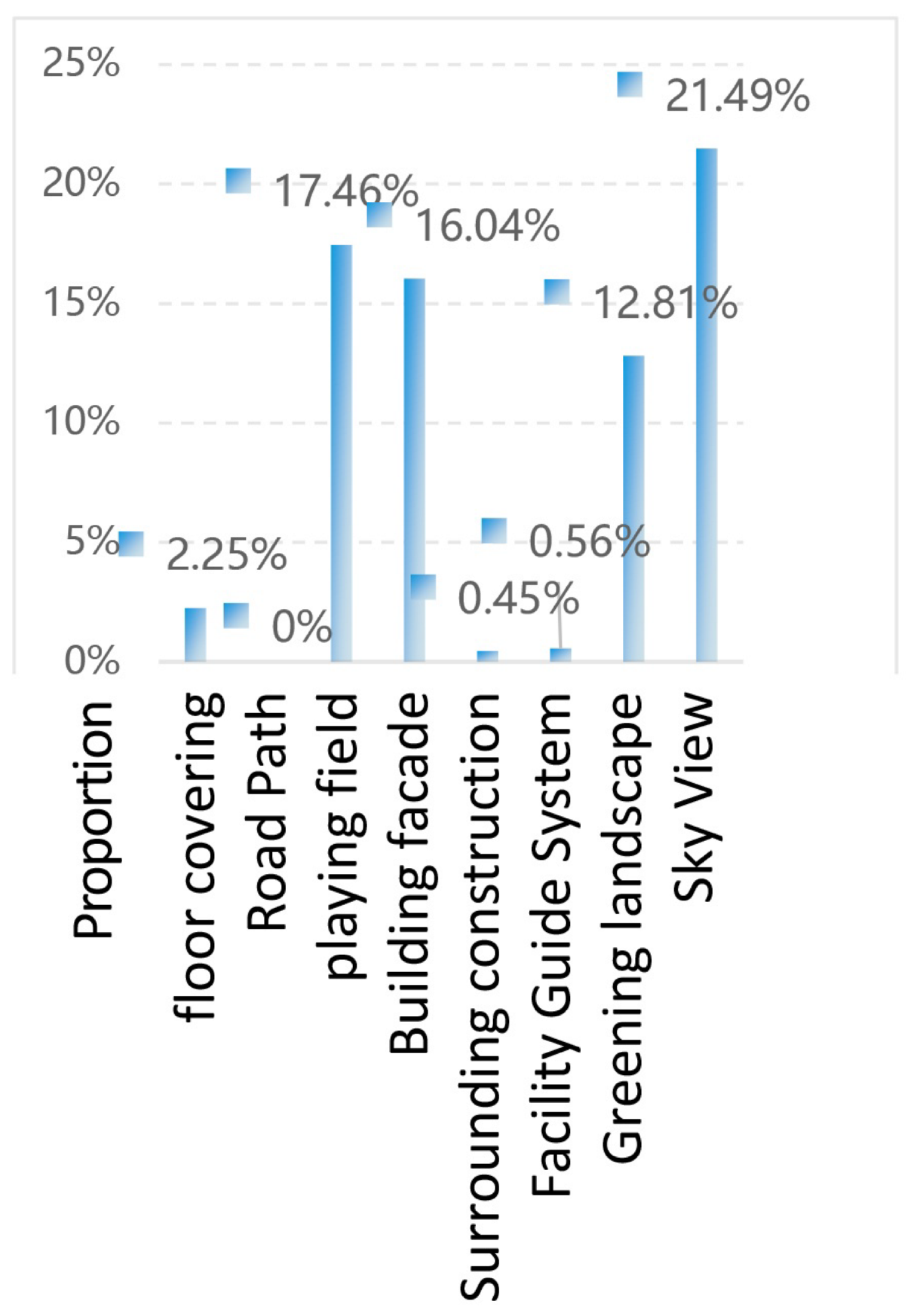

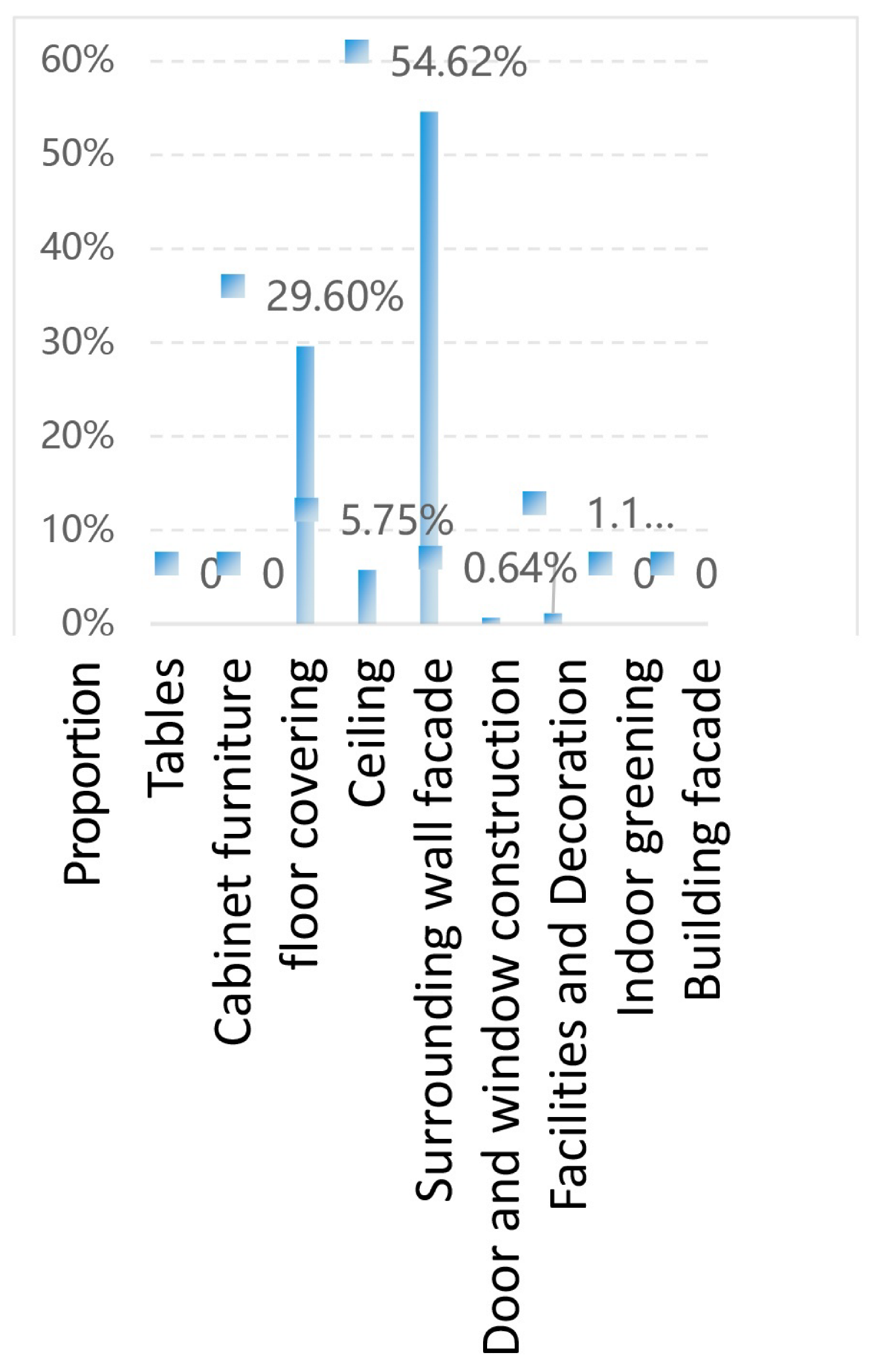

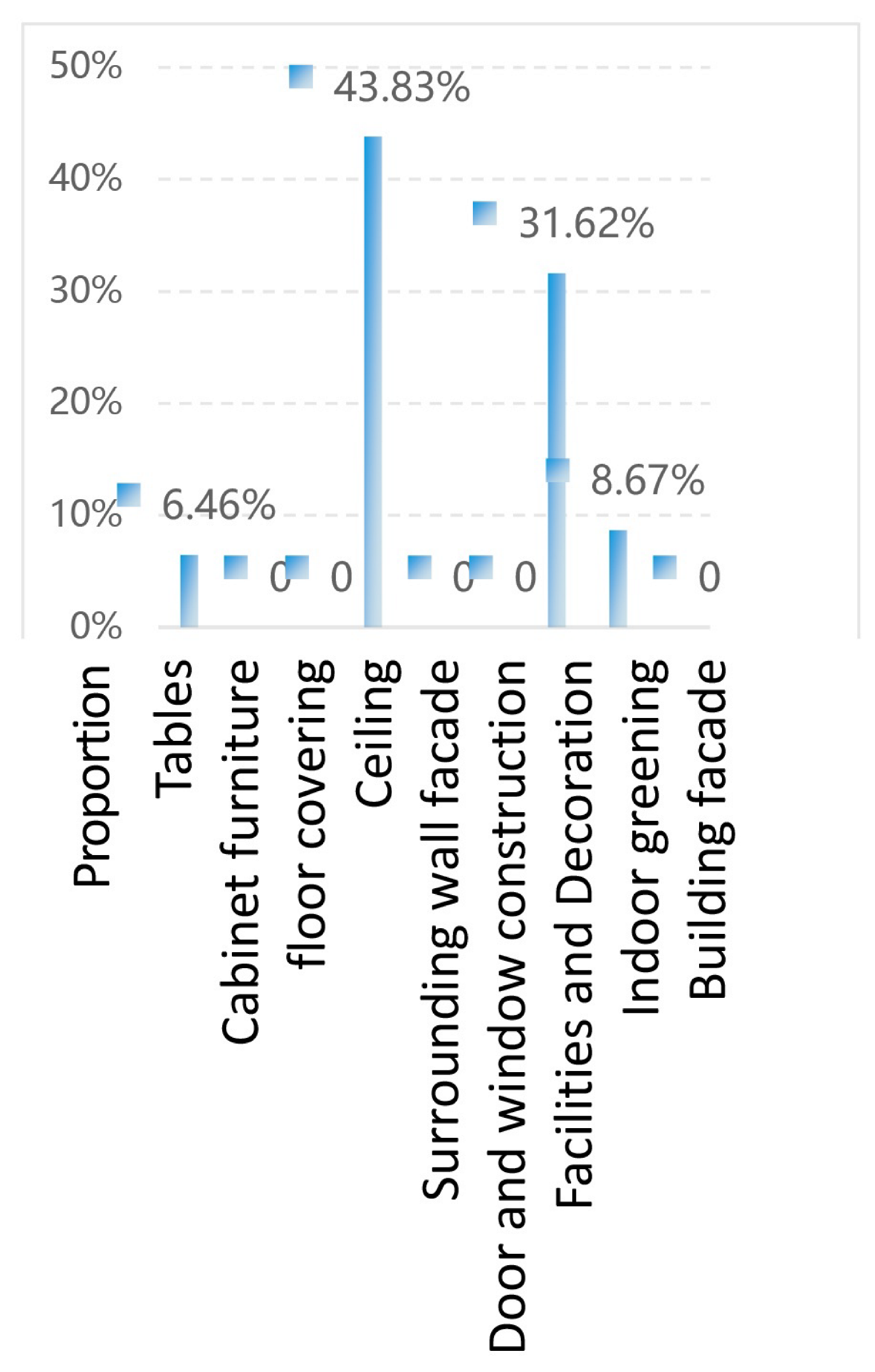

3.1. Influence of Spatial Elements on Children’s Emotions

- (i)

- Prioritize high-impact elements: Treat components that influence multiple emotional dimensions as primary design targets.

- (ii)

- Layer functions of spatial elements: Because elements contribute differently to emotional responses, define their functional hierarchy and coordinate design according to their roles within each dimension.

- (iii)

- Integrated across factors: No single element can meet children’s emotional needs; therefore, employ multi-factor, synergistic strategies to optimize the overall emotional experience.

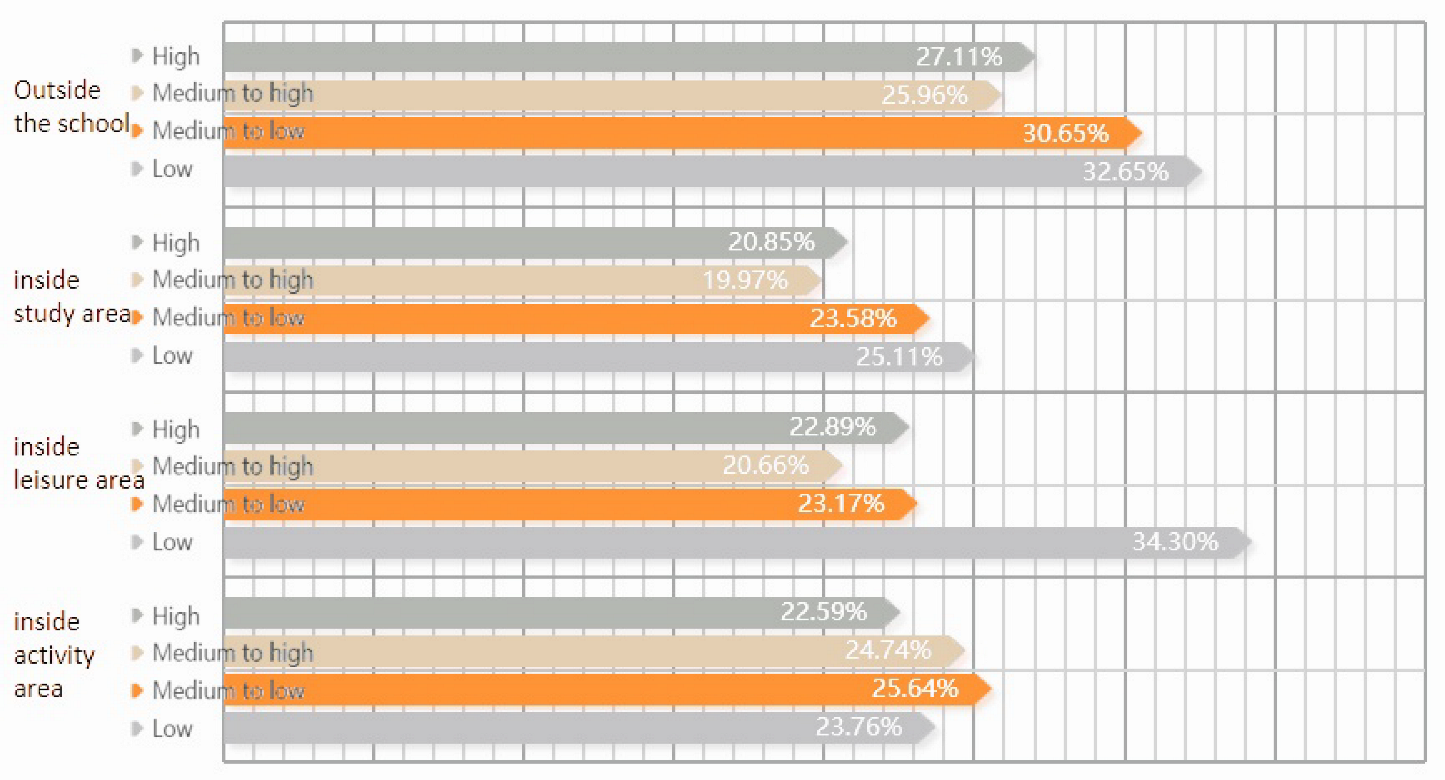

3.2. Influence of Space Type on Children’s Emotions

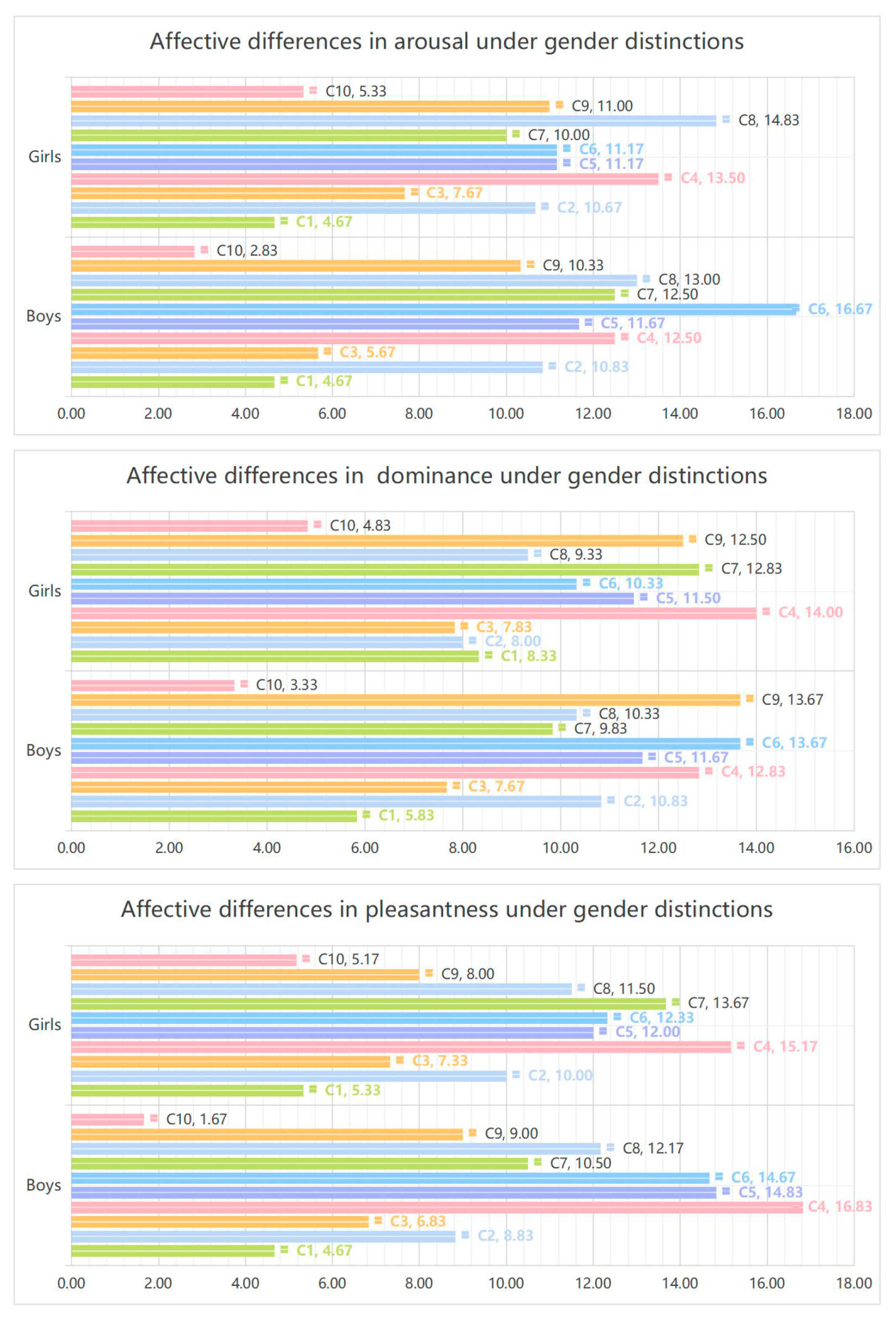

3.3. Influence of Spatial Color on Children’s Emotions

- (1)

- Gender-Based Characteristics of Children’s Emotional Responses

- (2)

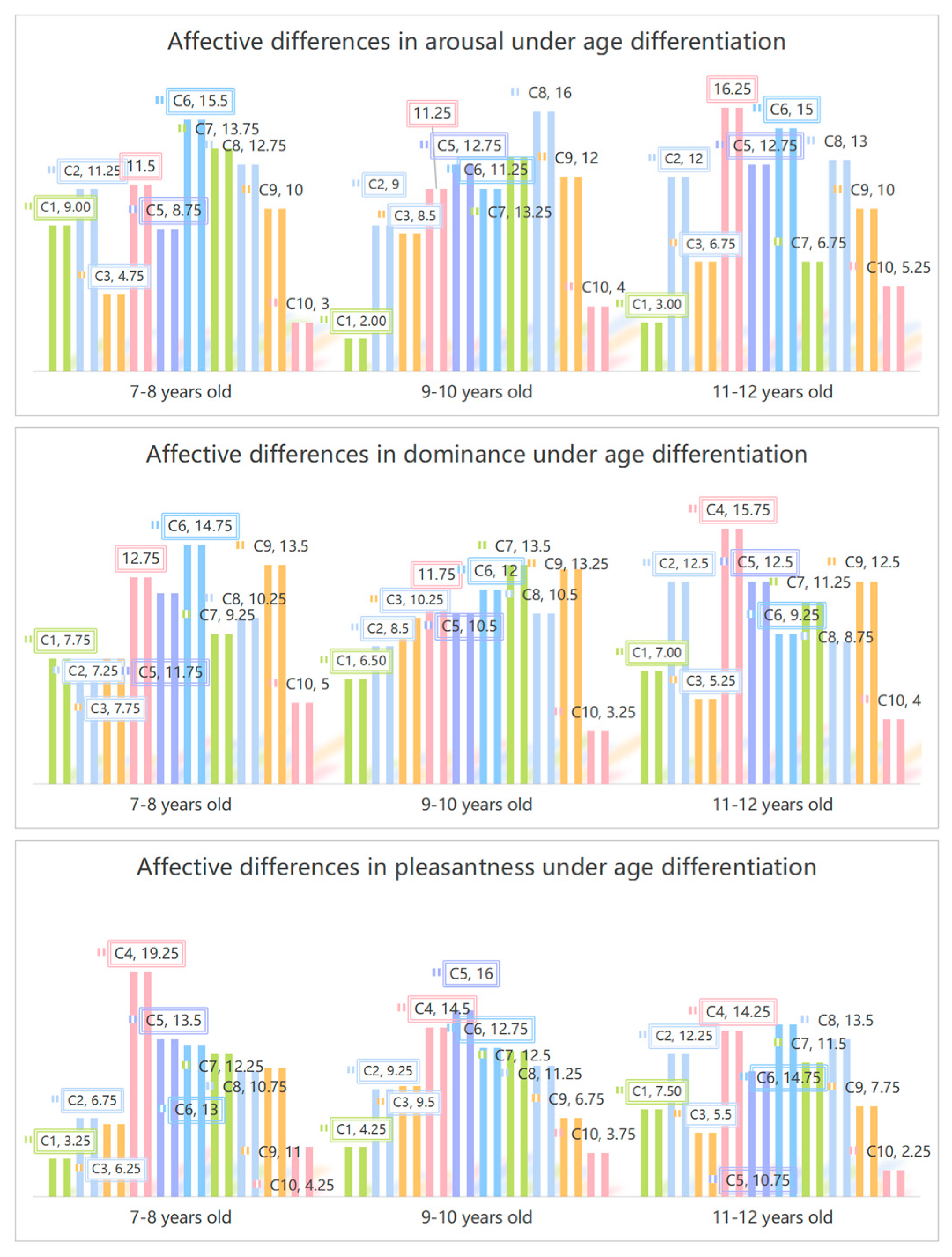

- Children’s Emotional Characteristics by Age

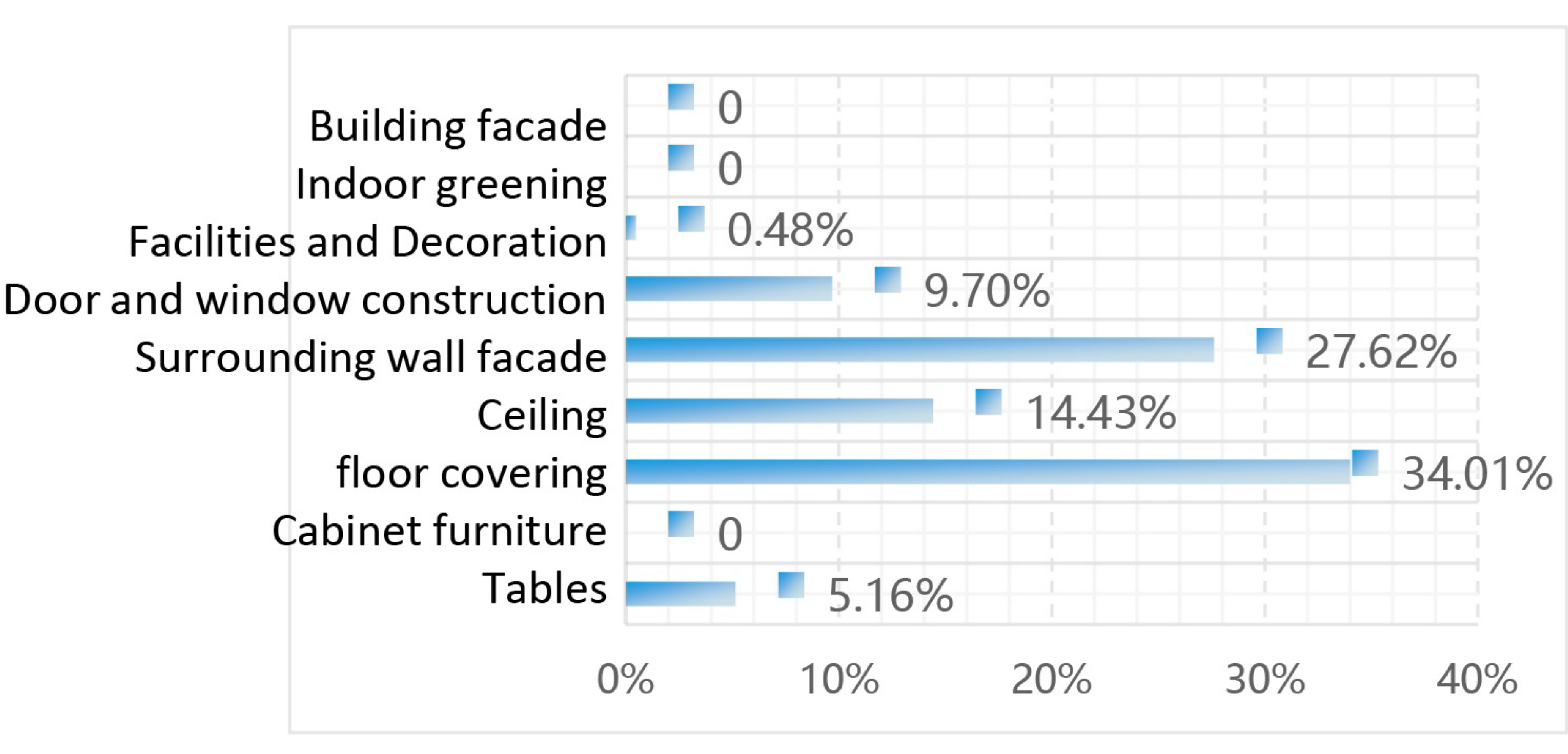

3.4. Correlation Between Spatial Elements and Spatial Color

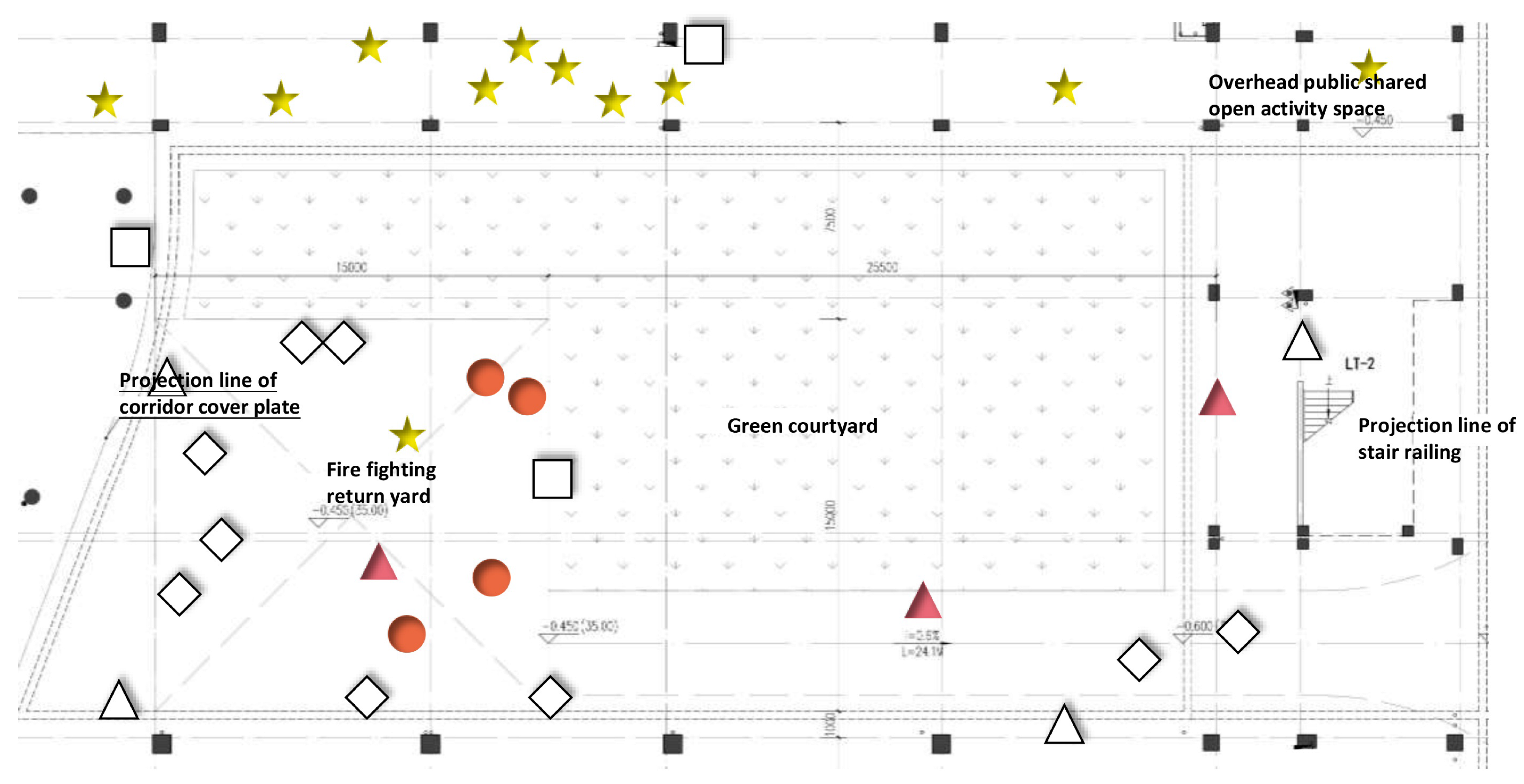

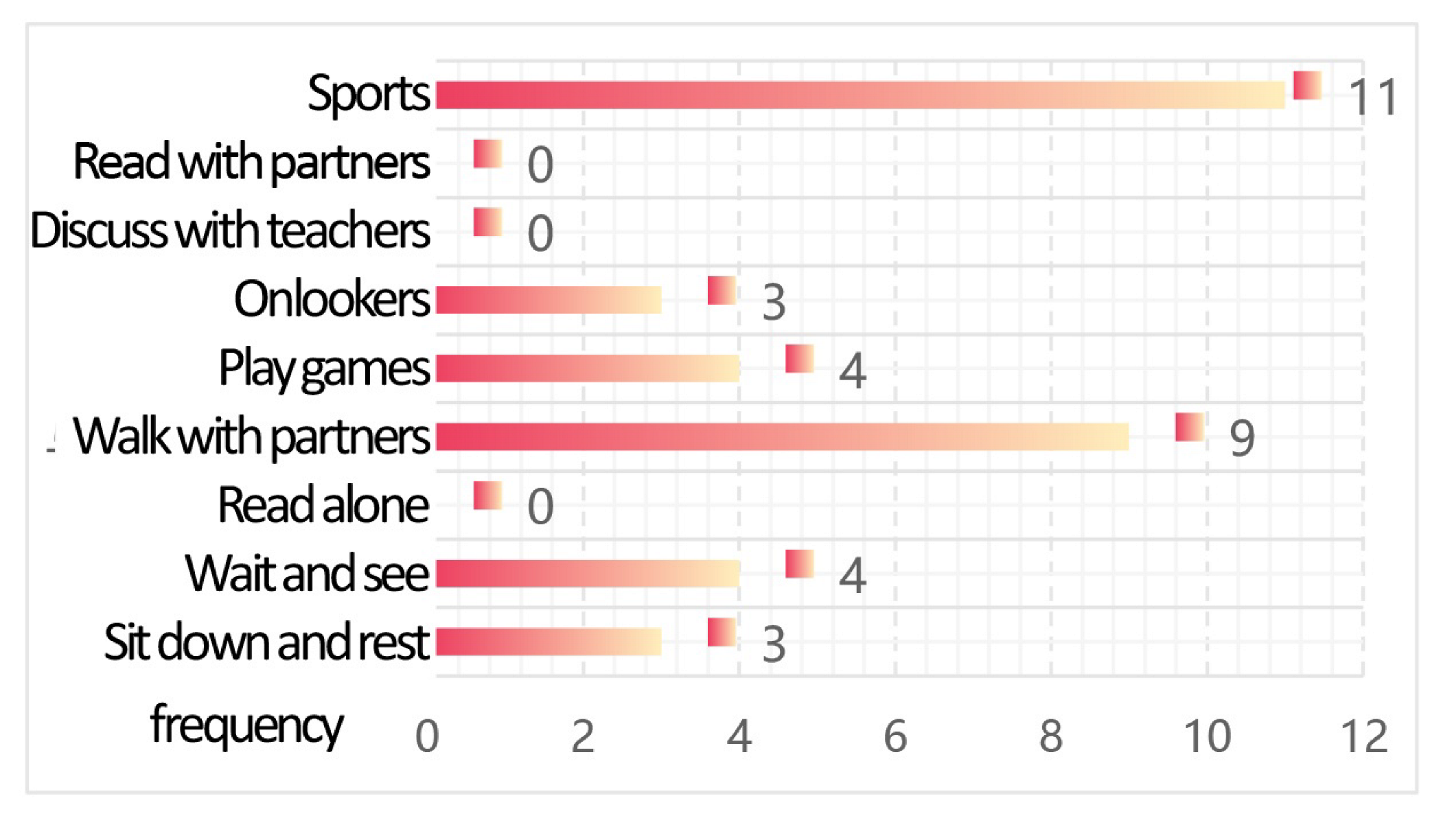

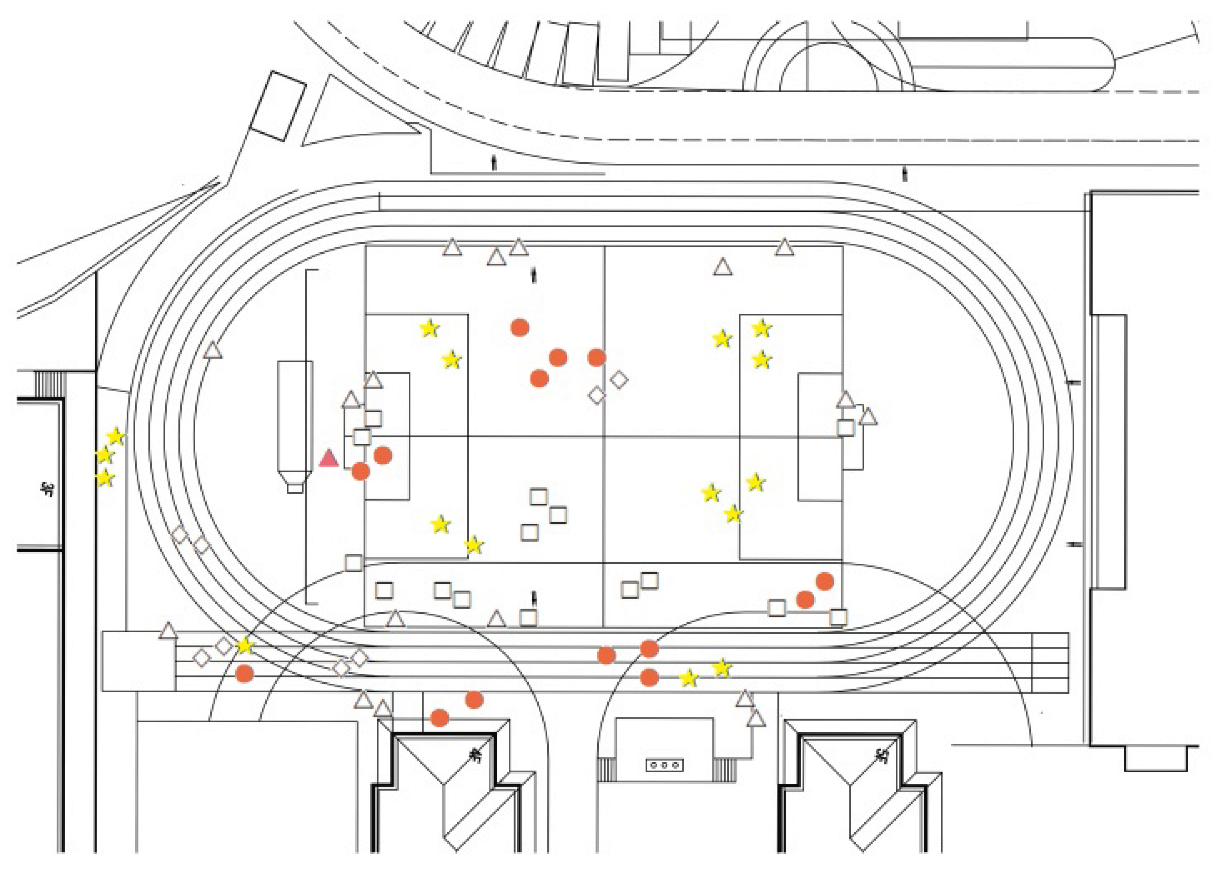

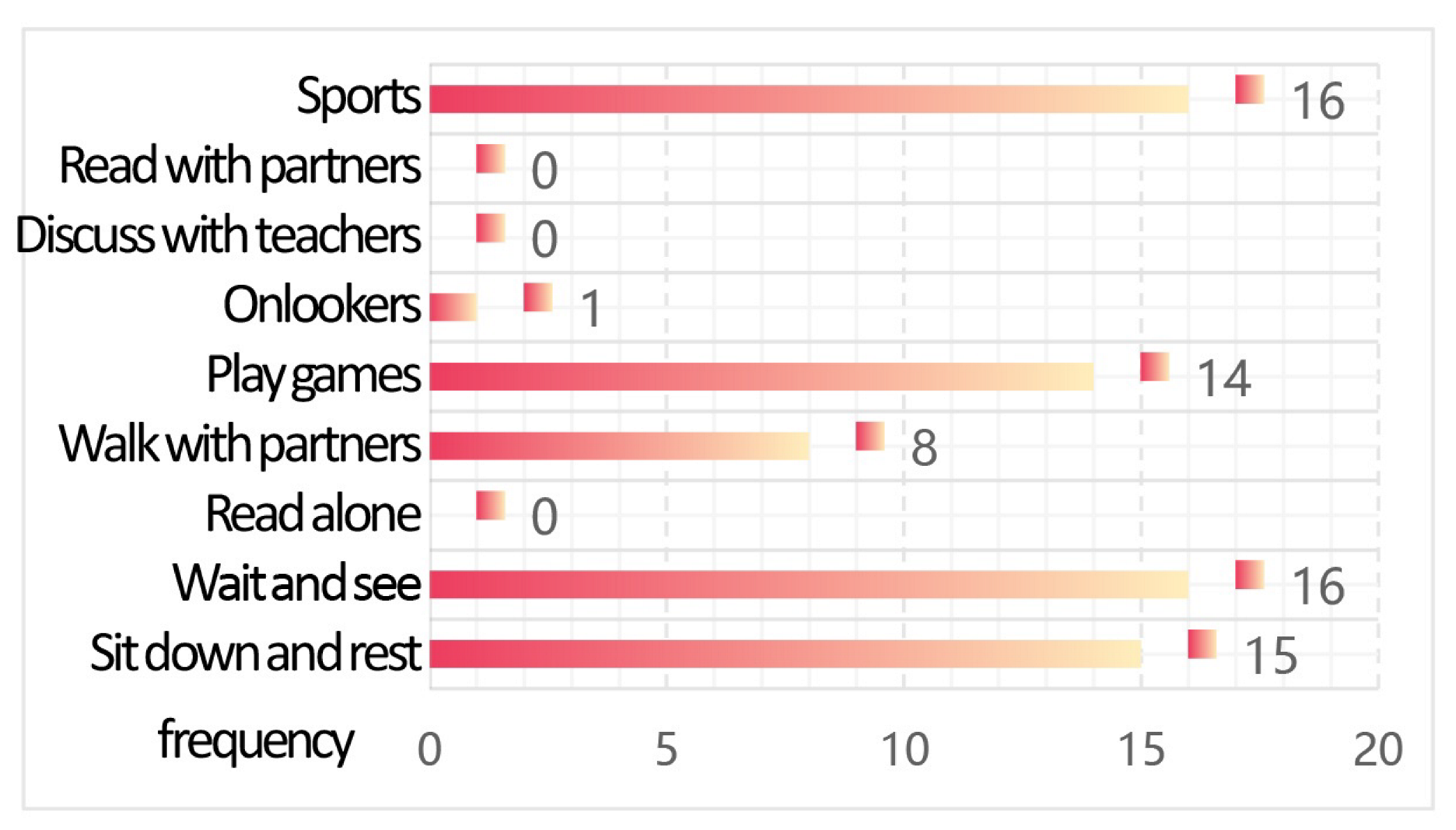

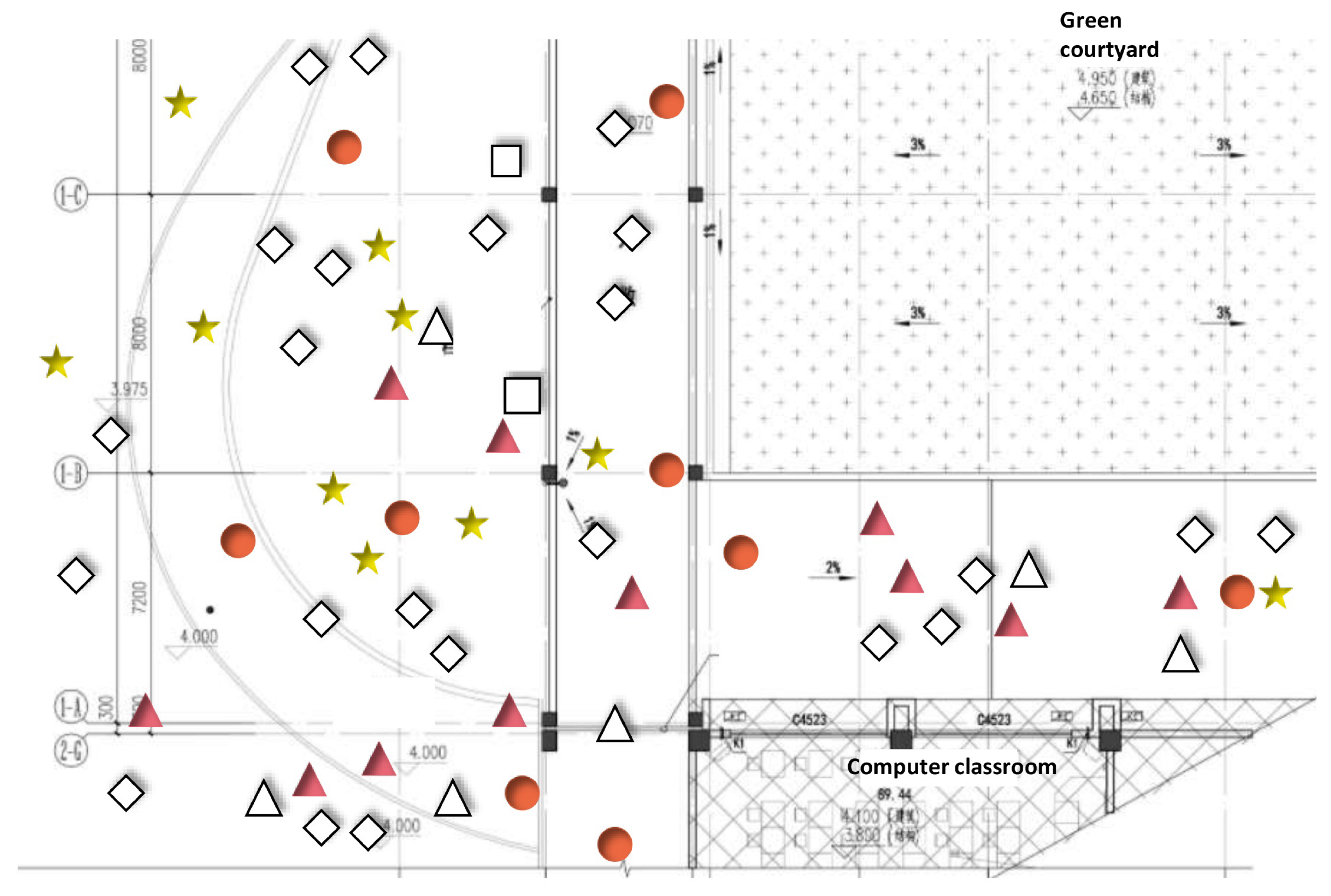

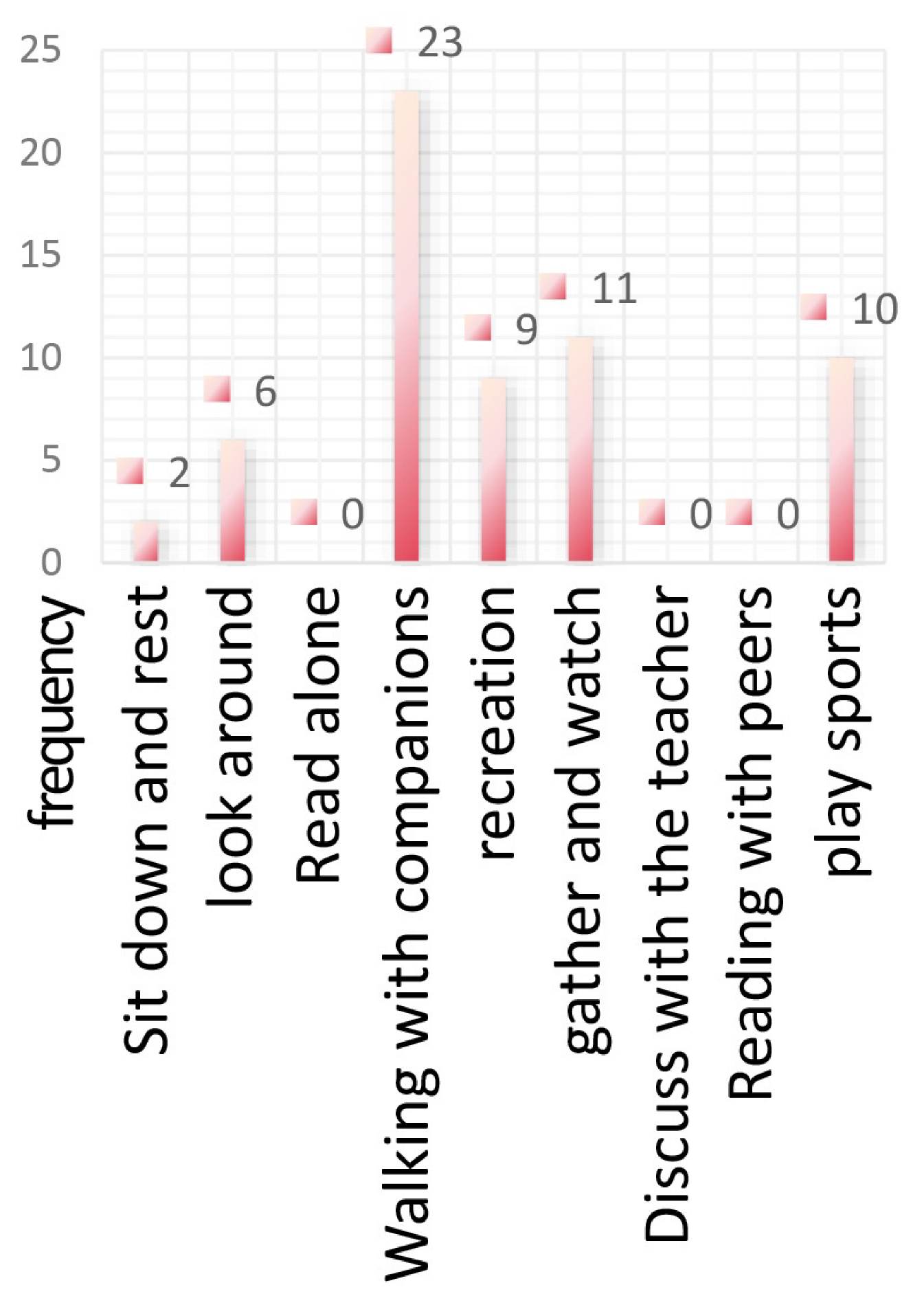

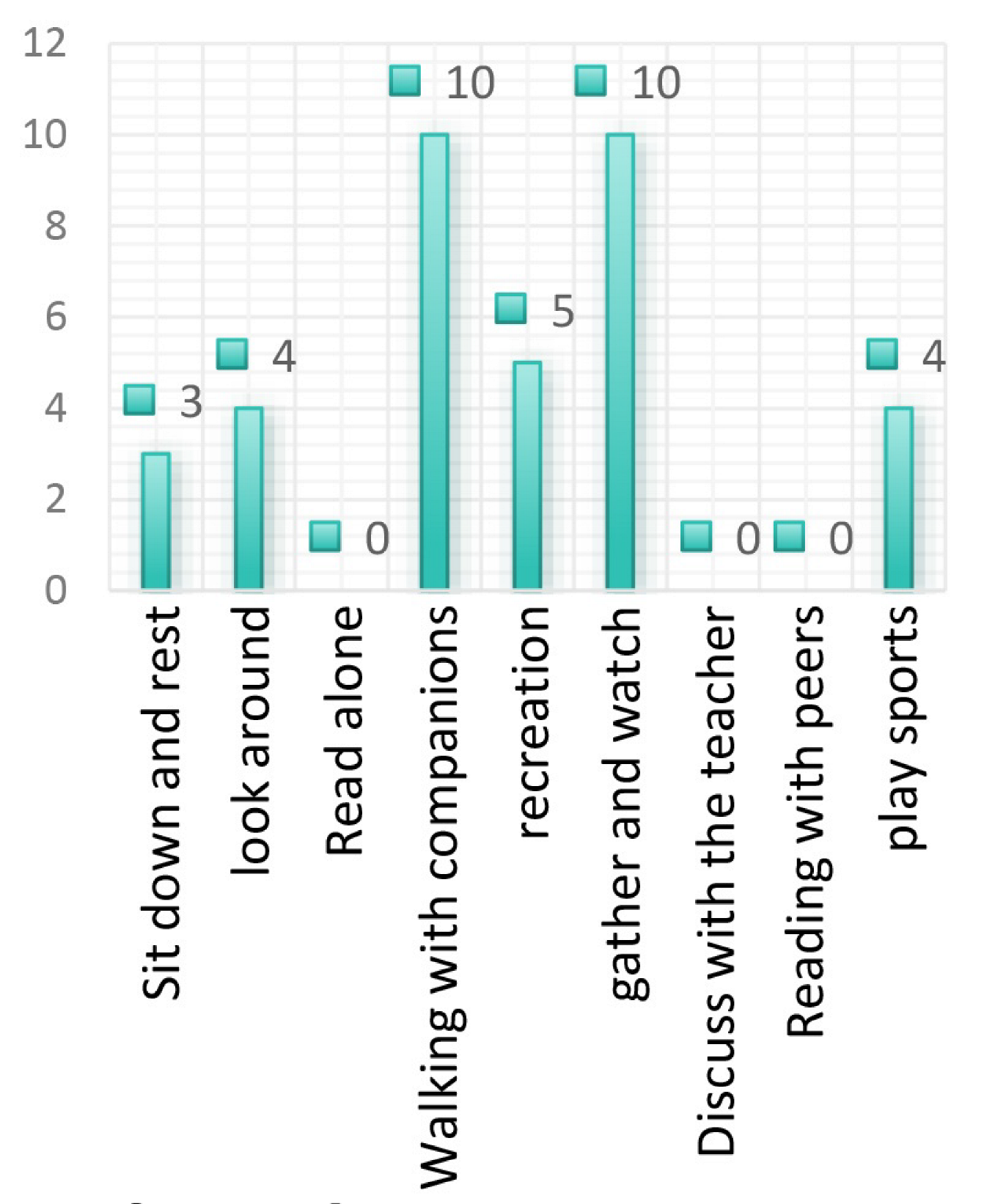

3.5. Overlay Analysis of Children’s Behavioral Maps

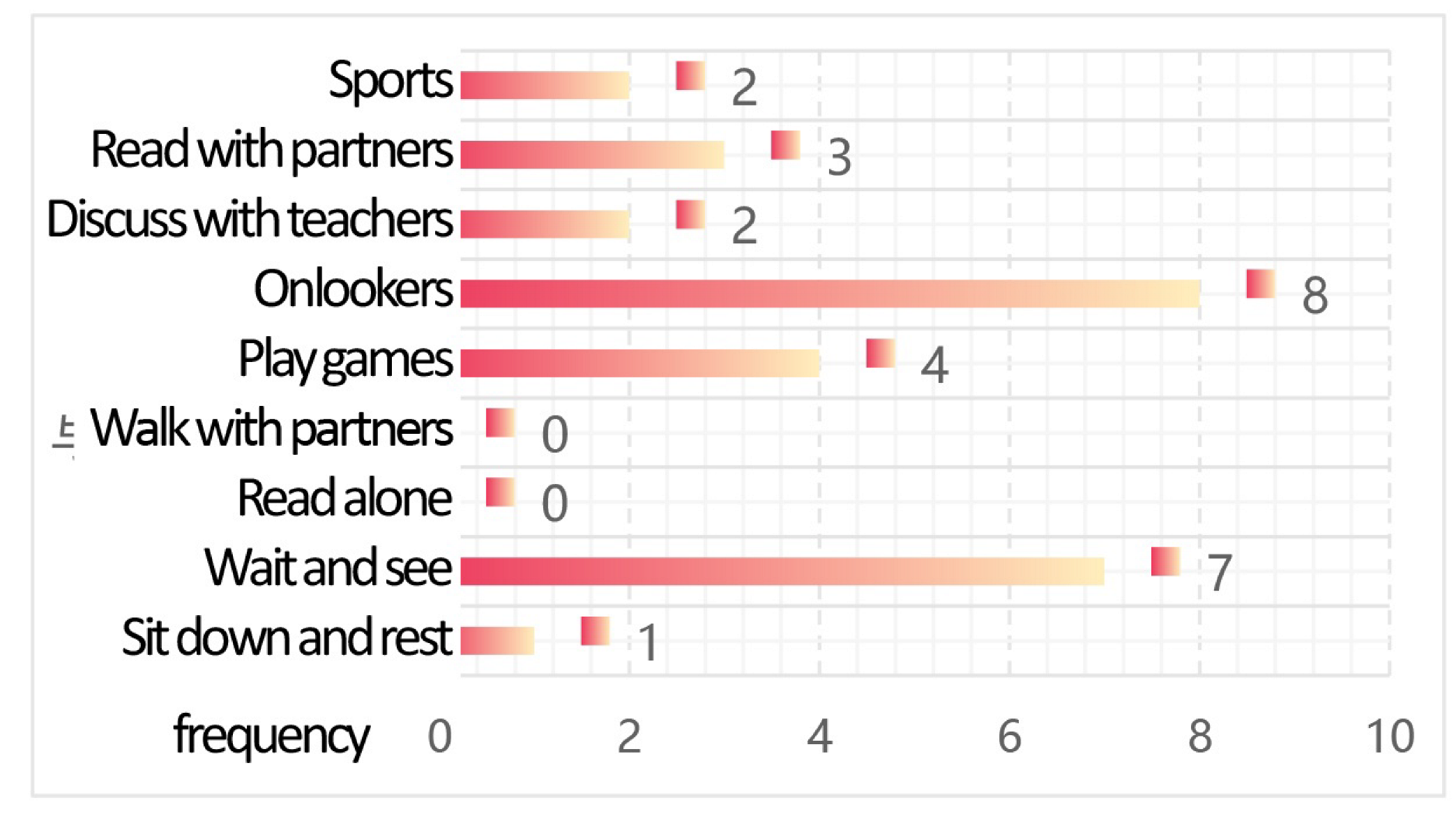

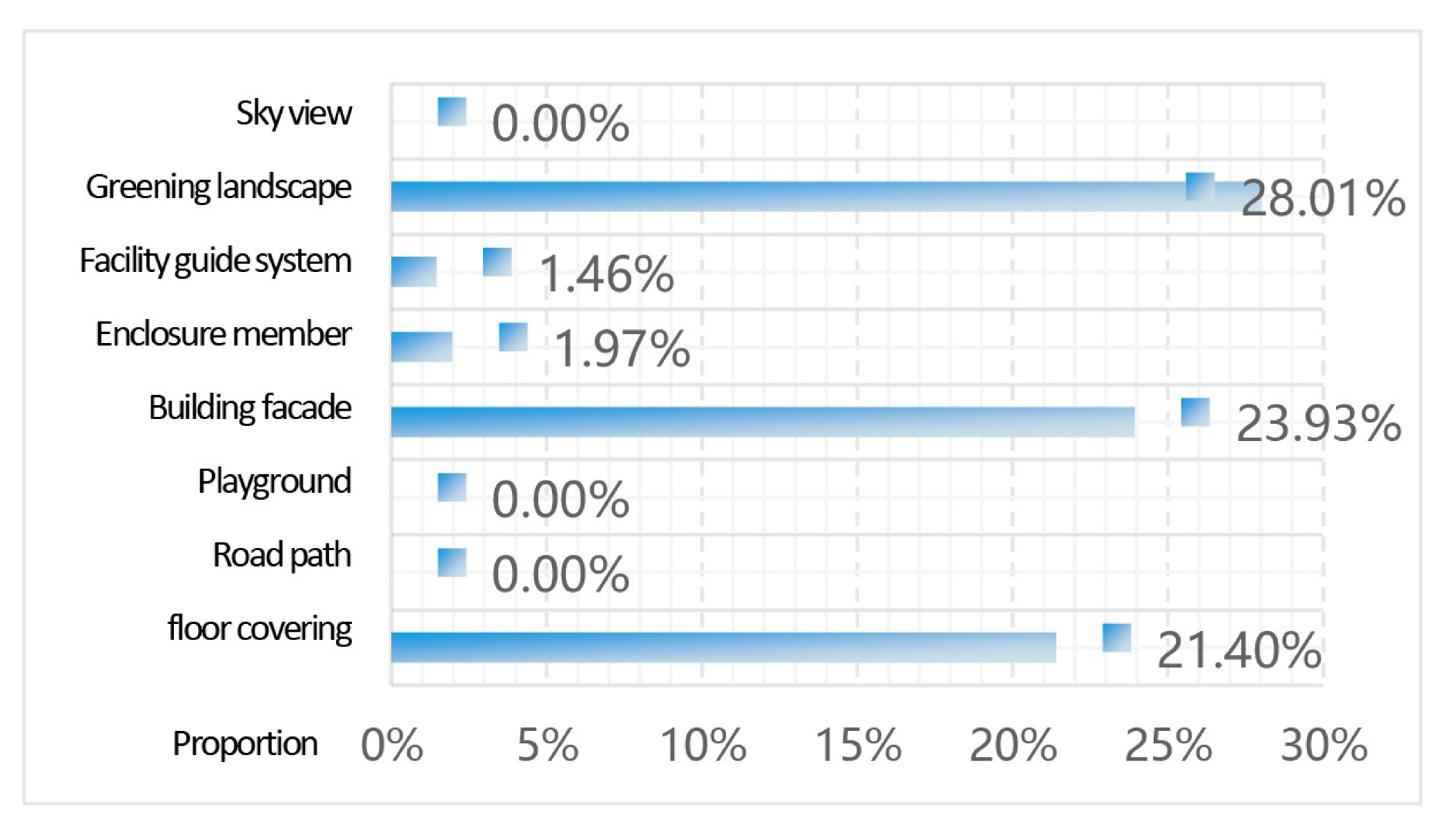

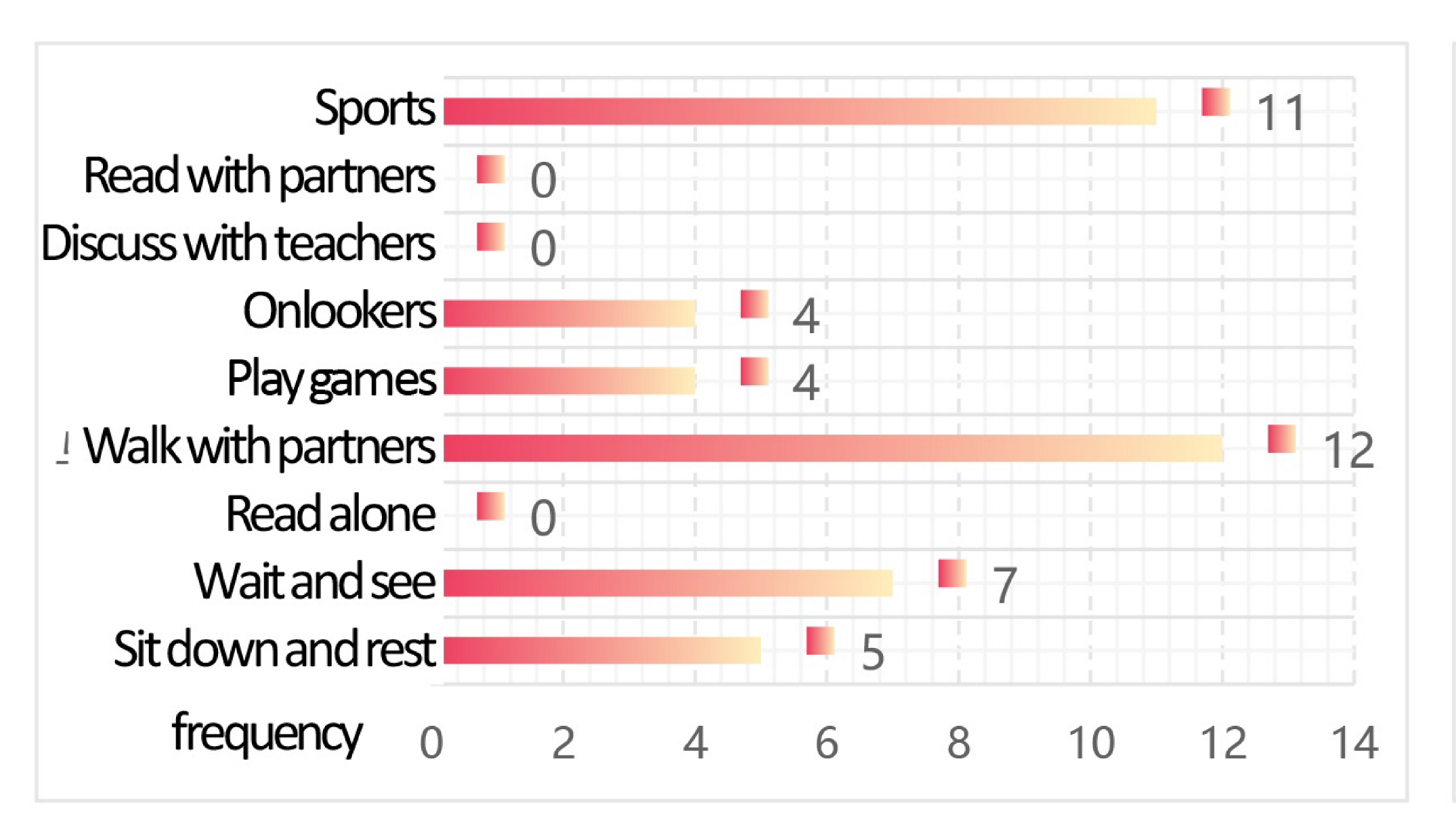

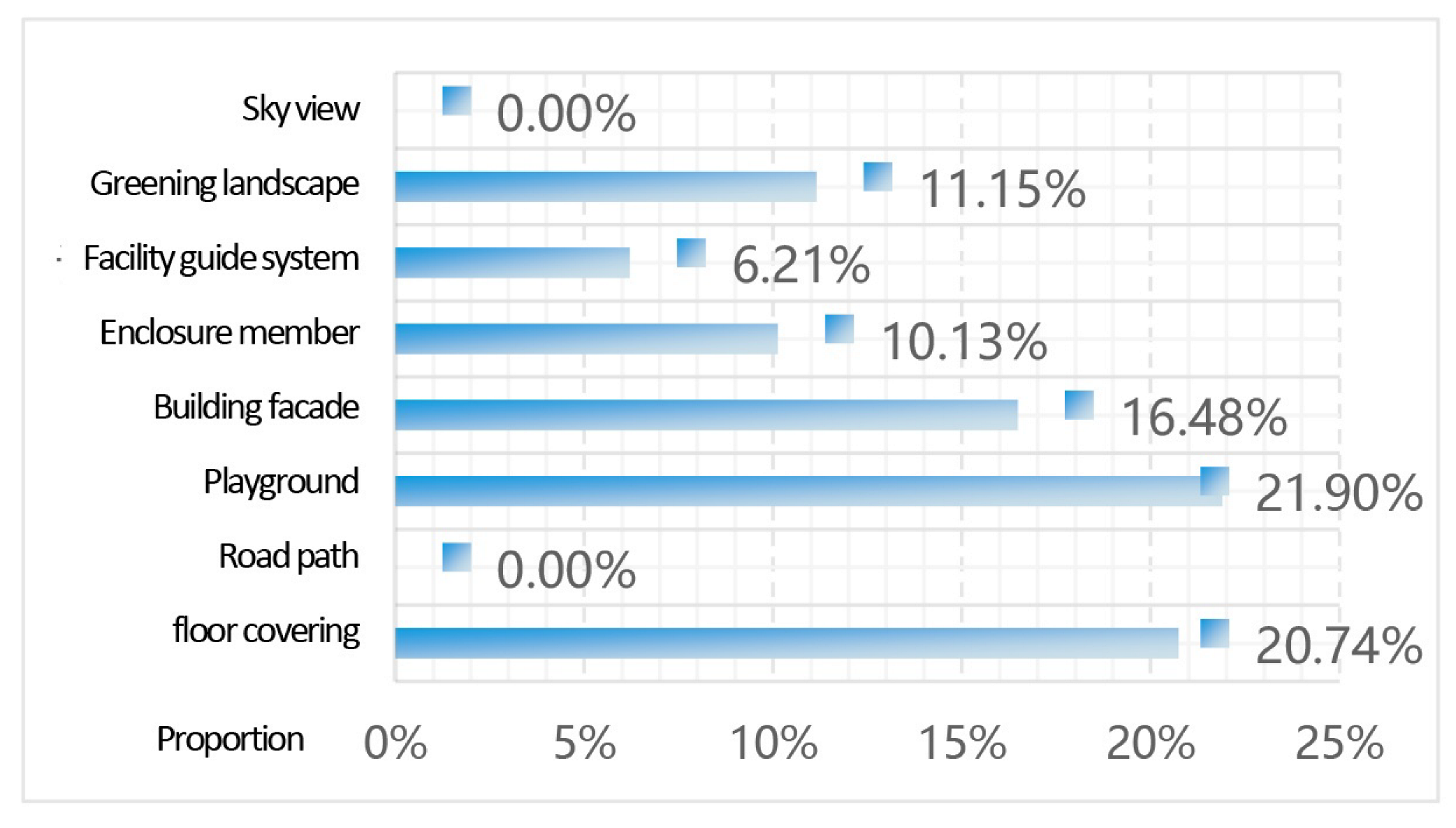

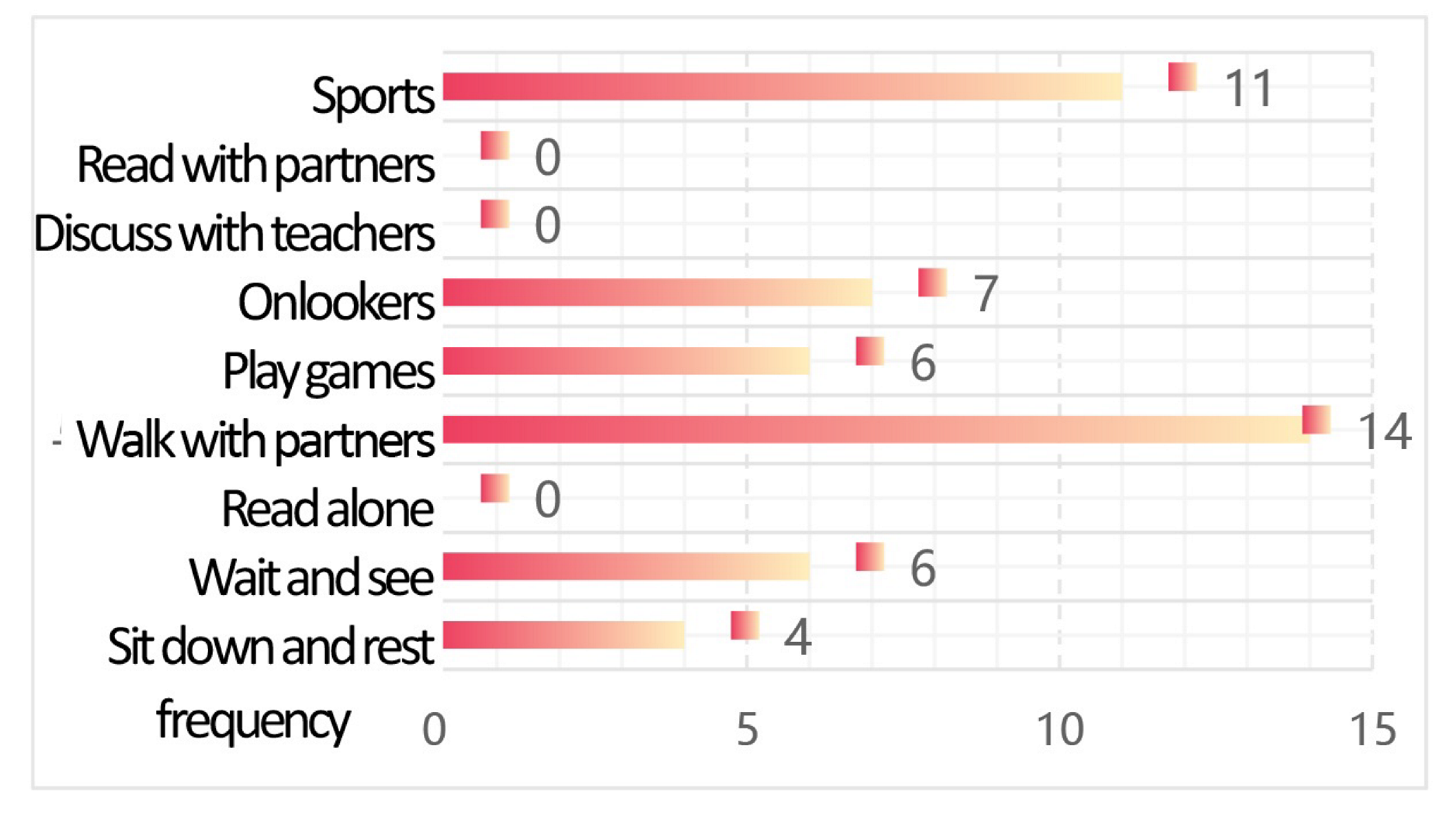

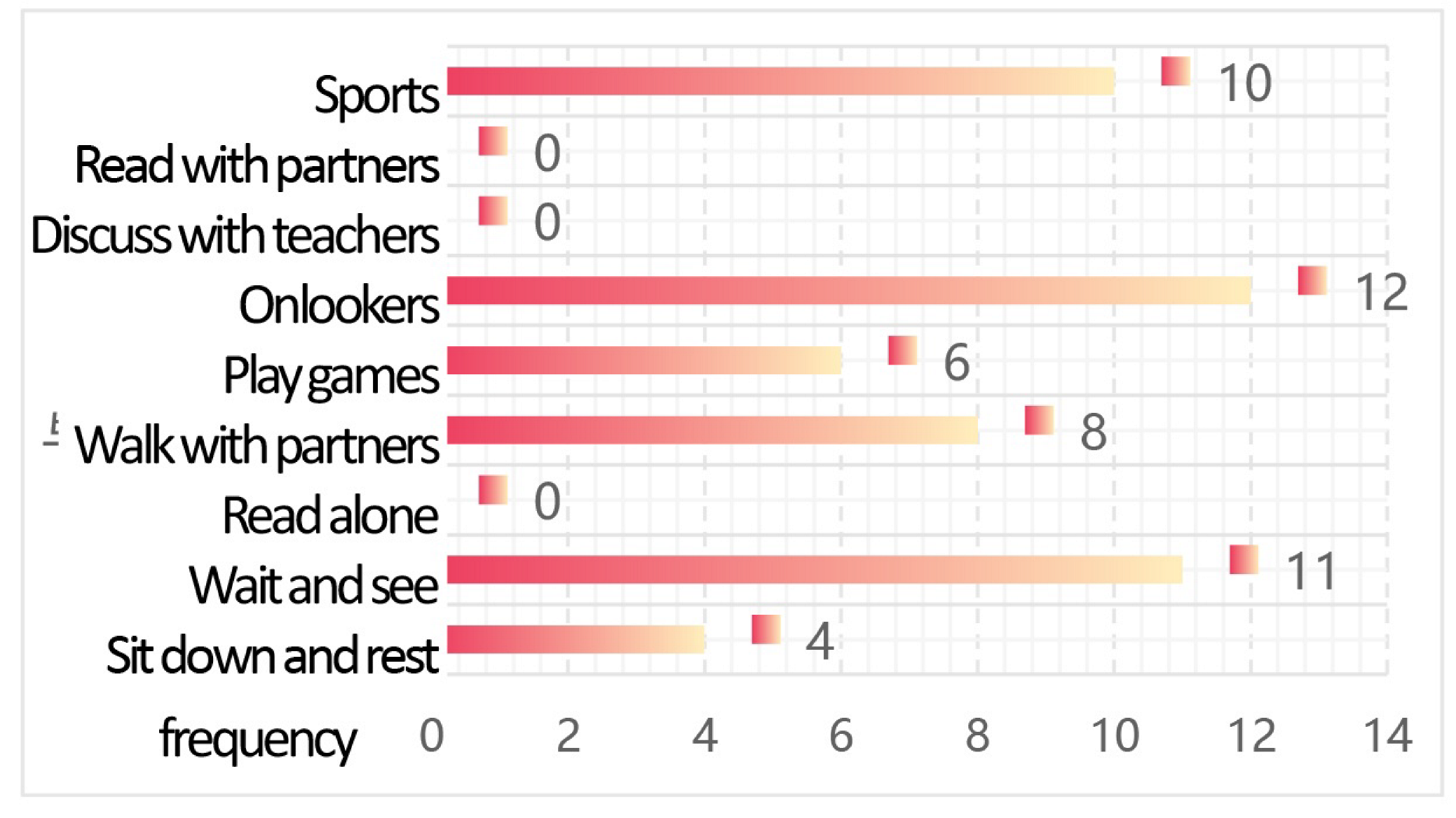

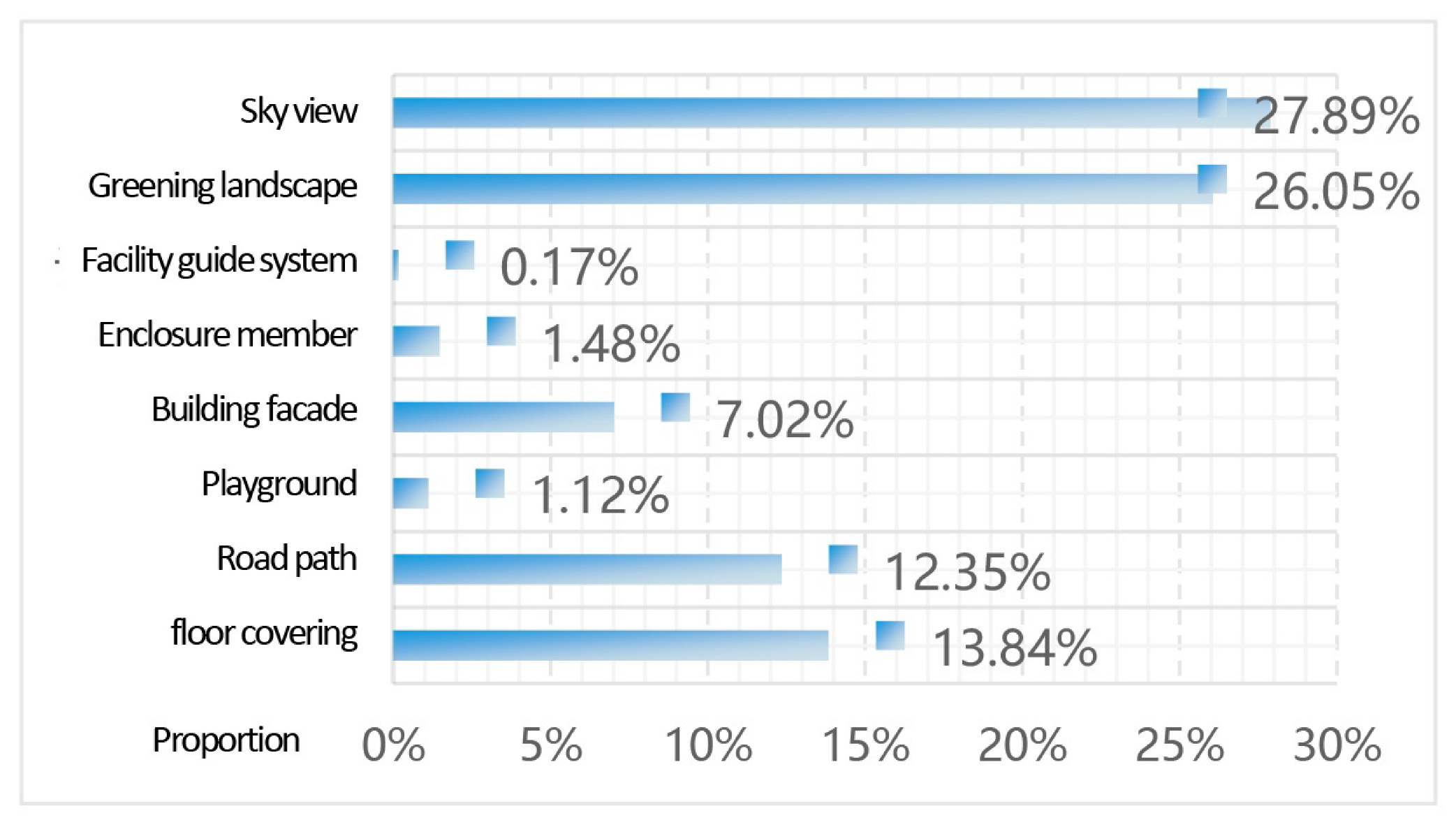

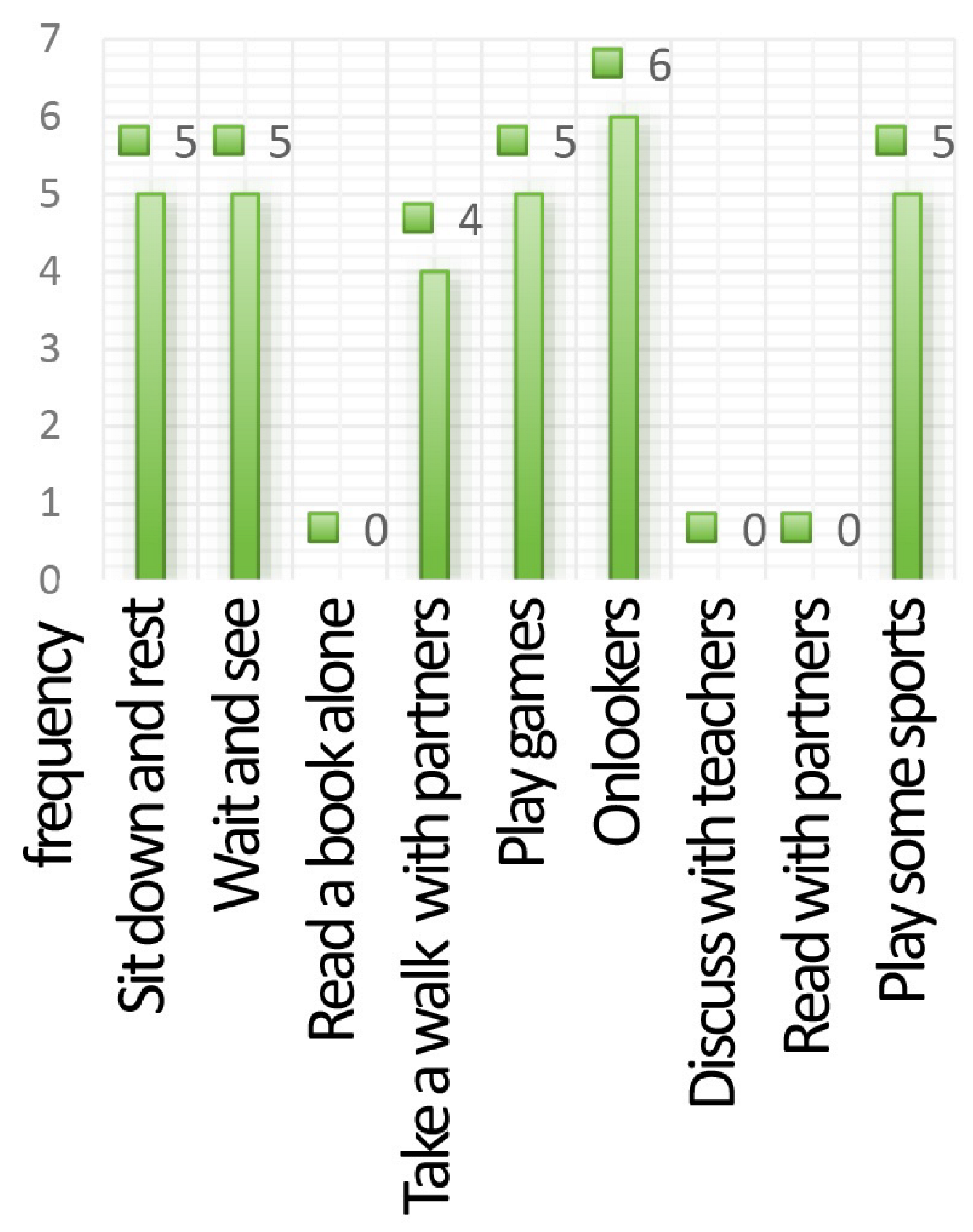

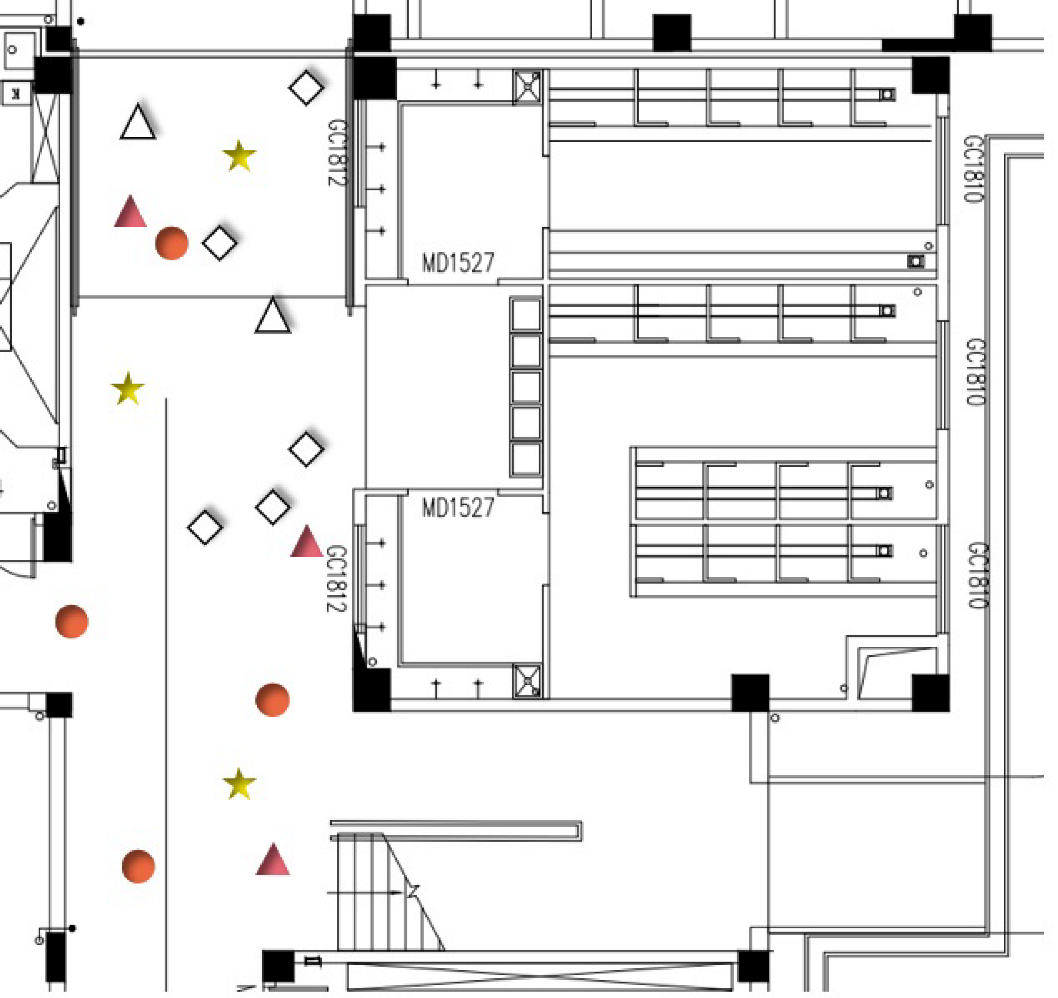

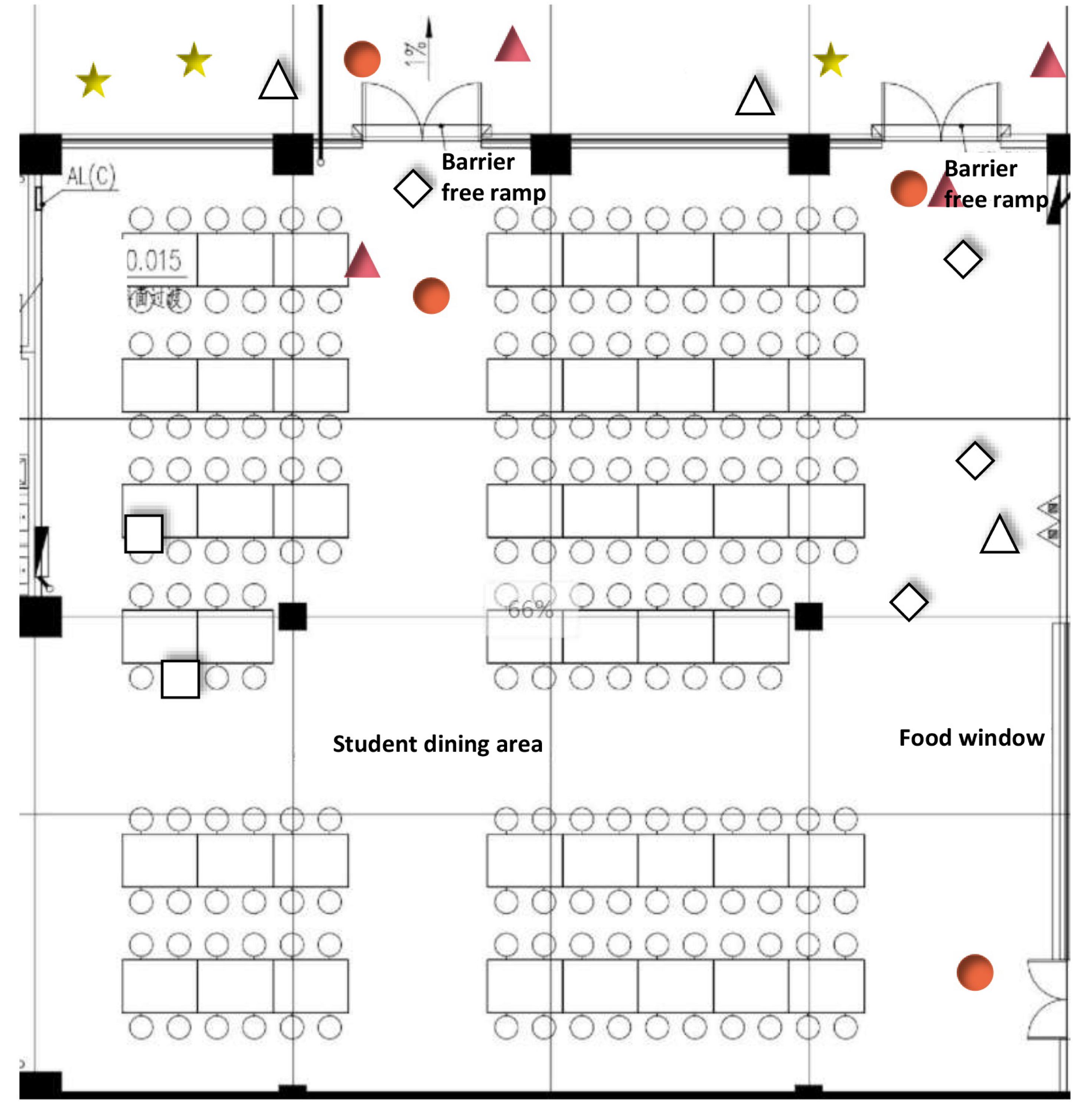

- (1)

- Campus external space

- (2)

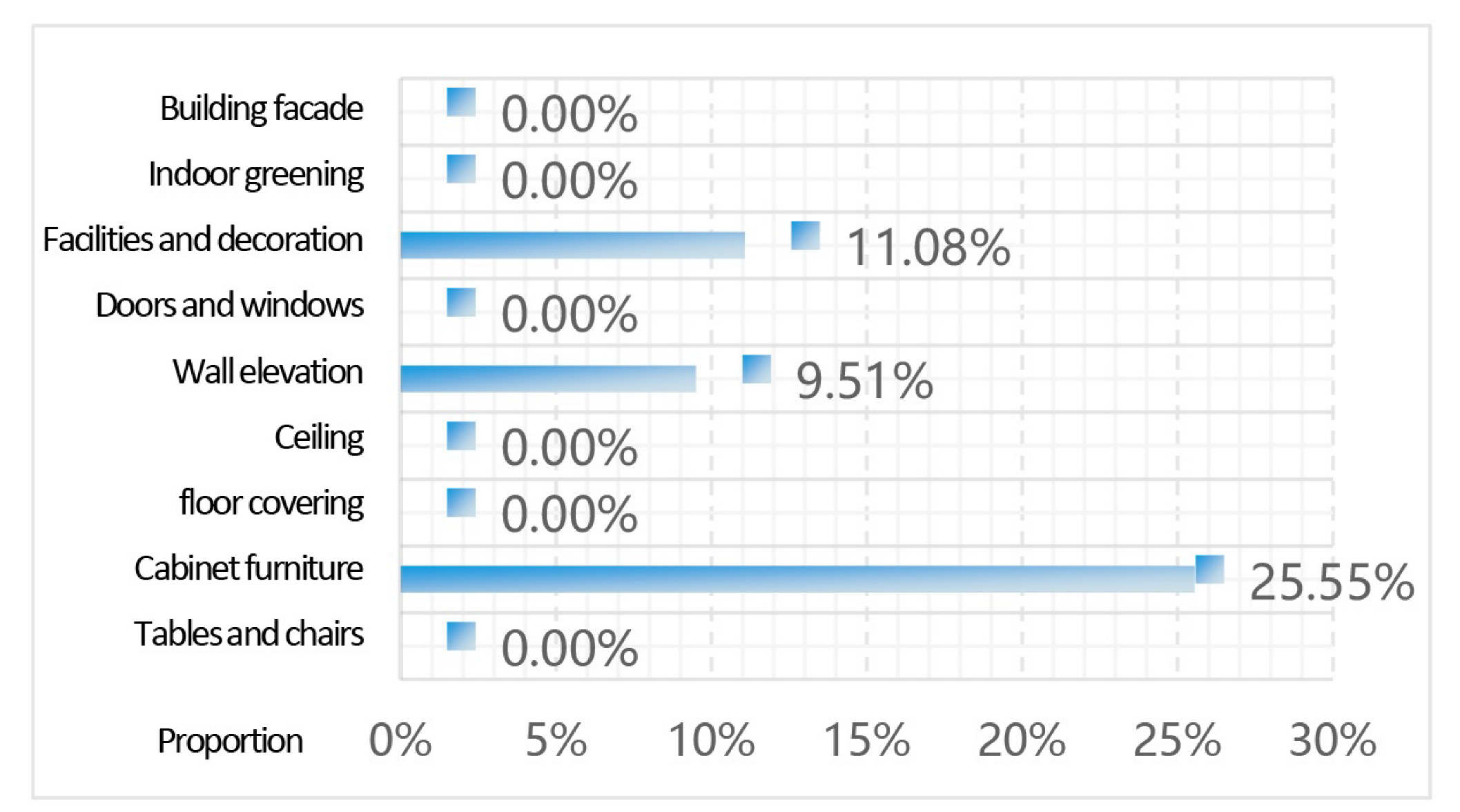

- Campus internal learning space

- (3)

- Living and leisure space inside campus

- (4)

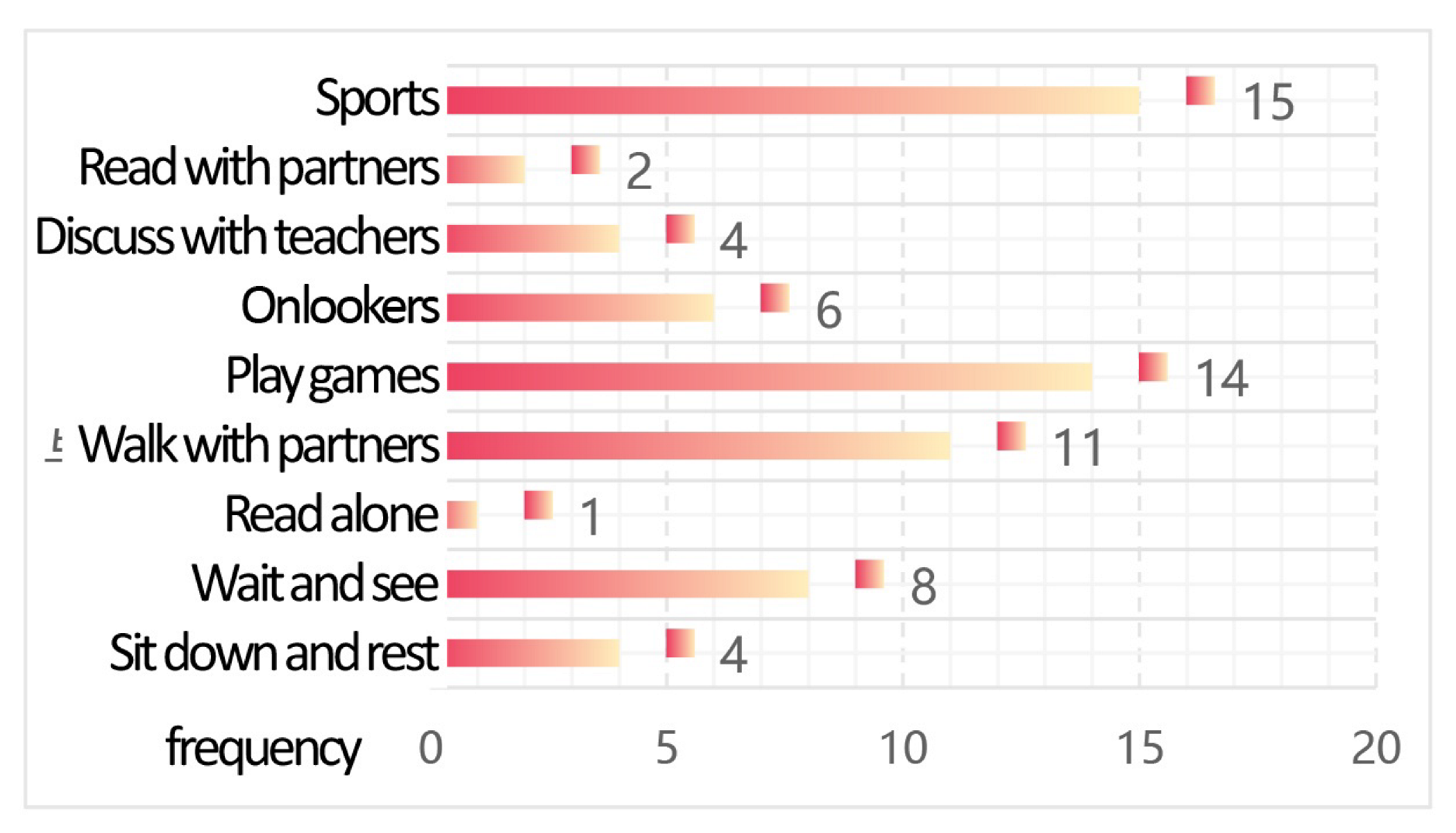

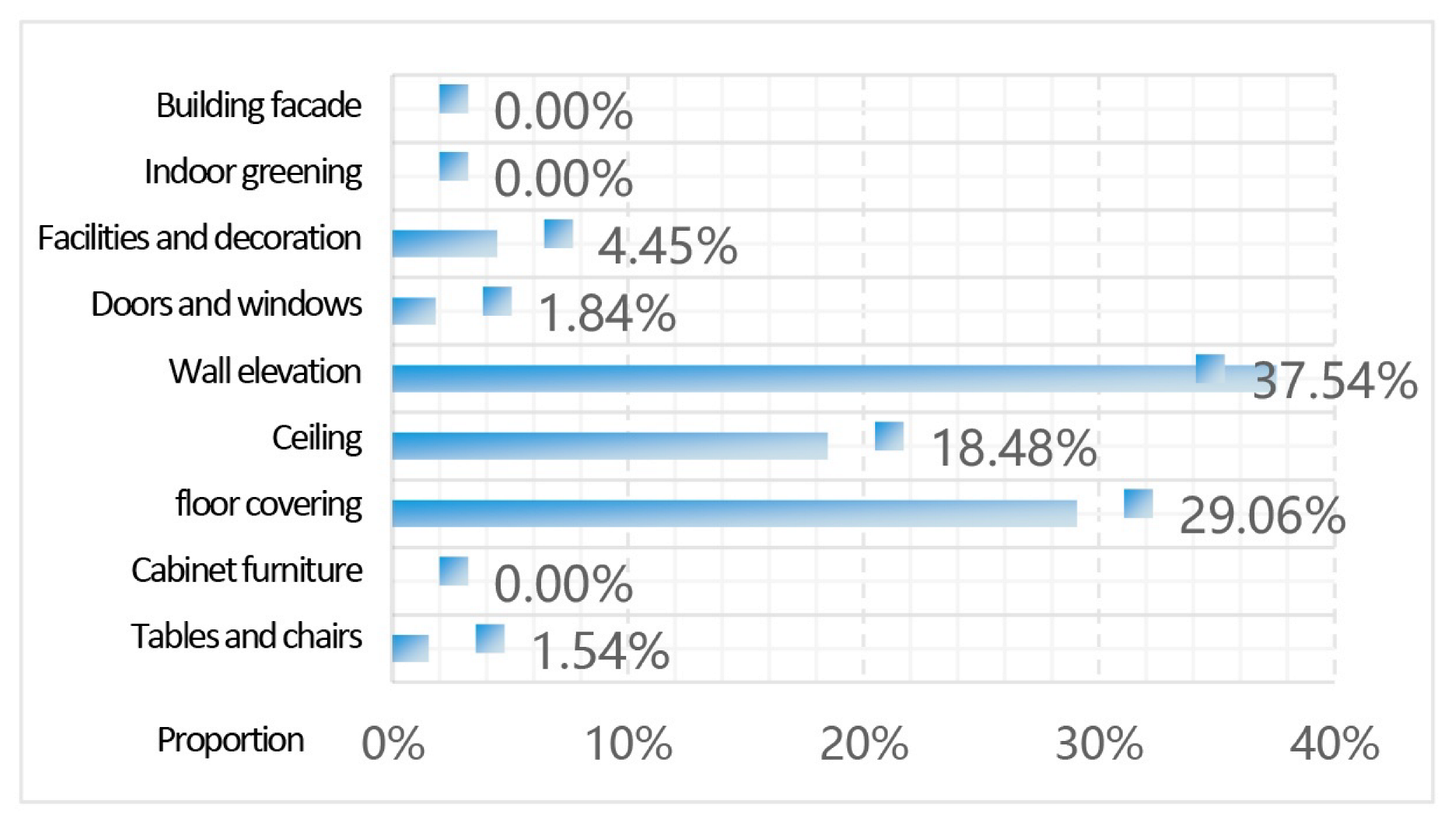

- Internal Activity Spaces

4. Discussion

4.1. Recommendations from Spatial Elements

- (1)

- Affective calibration and load management of key spatial elements.

- (2)

- Functional stratification and coordinated configuration of spatial elements.

- (3)

- Adopting a Comprehensive Strategy of Multi-Scale and Multi-Scene Design

4.2. Suggestions from Space Type

- (1)

- Learning zones: coordinating sustained focus and controllability

- (2)

- Leisure and living zones: social activation with low-load pleasure

- (3)

- Activity zones: order and safety within high arousal

- (4)

- Outdoor spaces: enhancing participation and perceived controllability

4.3. Suggestions from Space Color

- (1)

- Matching Space Function with Color Characteristics

- (2)

- Coupling Spatial Elements with Color Design

4.4. Suggestions from the Behavior Map

- (1)

- Emotive renewal of high-frequency nodes.

- (2)

- Enhancing Functional Layers and Decorative Elements in Living and Leisure Spaces

- (3)

- Strengthening Spatial Flexibility and Visual Guidance in Activity Areas

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pallasmaa, J. Space, place, and atmosphere: Peripheral perception in existential experience. In Architectural Atmospheres: On the Experience and Politics of Architecture; Borch, C., Ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 18–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semsioglu, S.; Gokce, Y.; Yantac, A.E. Emotionscape: Mediating spatial experience for emotion awareness and sharing. In Proceedings of the Extended Abstracts of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Montreal, QC, Canada, 21–26 April 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Feng, W.; Xiang, J. Color expression of architectural emotion language from the perspective of public art. J. Landsc. Res. 2016, 8, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bower, I.; Tucker, R.; Enticott, P.G. Impact of built environment design on emotion measured via neurophysiological correlates and subjective indicators: A systematic review. J. Environ. Psychol. 2019, 66, 101344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, B.; Kang, J.; Kim, C.; Kim, S.; Song, Y.; Yeon, J. The effect of personal characteristics on spatial perception in BIM-based virtual environments: Age, gender, education, and gaming experience. Buildings 2023, 13, 2103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosco, F.J.; Joassart-Marcelli, P. Participatory planning and children’s emotional labor in the production of urban nature. Emot. Space Soc. 2015, 16, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gifford, R. Environmental psychology matters. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 2014, 65, 541–579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, M.; Wang, M. Effects of school indoor visual environment on children’s health outcomes: A systematic review. Health Place 2023, 83, 103021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzhambov, A.M.; Lercher, P.; Vincens, N.; Waye, K.P.; Klatte, M.; Leist, L.; Lachmann, T.; Schreckenberg, D.; Belke, C.; Ristovska, G.; et al. Protective effect of restorative possibilities on cognitive function and mental health in children and adolescents: A scoping review including the role of physical activity. Environ. Res. 2023, 233, 116452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wells, N.M. At home with nature: Effects of “greenness” on children’s cognitive functioning. Environ. Behav. 2000, 32, 775–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lau, S.S.Y.; Gou, Z.; Liu, Y. Healthy campus by open space design: Approaches and guidelines. Front. Archit. Res. 2014, 3, 452–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amicone, G.; Petruccelli, I.; De Dominicis, S.; Gherardini, A.; Costantino, V.; Perucchini, P.; Bonaiuto, M. Green breaks: The restorative effect of the school environment’s green areas on children’s cognitive performance. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 1579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, S. The restorative benefits of nature: Toward an integrative framework. J. Environ. Psychol. 1995, 15, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finnigan, K.A. Sensory responsive environments: A qualitative study on perceived relationships between outdoor built environments and sensory sensitivities. Land 2024, 13, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, H.; Sulaiman, R.; Ismail, M.A. Enhancing children’s health and well-being through biophilic design in Chinese kindergartens: A systematic literature review. Soc. Sci. Humanit. Open 2024, 10, 100939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Tu, X.; Huang, G.; Fang, X.; Kong, L.; Wu, J. Urban greenspace helps ameliorate people’s negative sentiments during the COVID-19 pandemic: The case of Beijing. Build. Environ. 2022, 223, 109449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Xu, S.; Shi, R.; Chen, Z.; Lin, Y.; Chen, J. Exploring the impact of university green spaces on students’ perceived restoration and emotional states through audio-visual perception. Ecol. Inform. 2024, 82, 102766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, F.; Munakata, J. Assessing effects of facade characteristics and visual elements on perceived oppressiveness in high-rise window views via virtual reality. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, H.; Barrett, S.; Duff, M.; Barnhardt, J.; Ritter, W. The effects of interstimulus interval on event-related indices of attention: An auditory selective attention test of perceptual load theory. Clin. Neurophysiol. 2008, 119, 542–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, B.; Yang, Y.; Mou, N.; Zheng, Y.; Zhang, L.; Yang, T. Cluster analysis of microscopic spatio-temporal patterns of tourists’ movement behaviors in mountainous scenic areas using open GPS-trajectory data. Tour. Manag. 2022, 93, 104614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Han, P.; Li, X.; Bao, X.; Huang, J. Continuation and evolution of collective memory manifested in rural public space: Revealed by semi-structured interviews and emotional maps in three migrant villages in Chaihu town. Habitat Int. 2024, 154, 103213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le, Q.H.; Kwon, N.; Nguyen, T.H.; Kim, B.; Ahn, Y. Sensing perceived urban stress using space syntactical and urban building density data: A machine learning-based approach. Build. Environ. 2024, 266, 112054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Göçer, Ö.; Göçer, K.; Başol, A.M.; Kıraç, M.F.; Özbil, A.; Bakovic, M.; Siddiqui, F.P.; Özcan, B. Introduction of a spatio-temporal mapping based POE method for outdoor spaces: Suburban university campus as a case study. Build. Environ. 2018, 145, 125–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- No, W.; Choi, J.; Kim, Y. How do children move and behave on streets? Vision-based movement behavior analysis using children’s trajectories in urban surveillance systems. Appl. Geogr. 2024, 162, 103170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damatac, C.G.; ter Avest, M.J.; Wilderjans, T.F.; De Gucht, V.; Woestenburg, D.H.A.; Landeweerd, L.; Galesloot, T.E.; Geerligs, L.; Homberg, J.R.; Greven, C.U. Exploring sensory processing sensitivity: Relationships with mental and somatic health, interactions with positive and negative environments, and evidence for differential susceptibility. Curr. Res. Behav. Sci. 2025, 8, 100165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manahasa, O.; Özsoy, A.; Manahasa, E. Evaluative, inclusive, participatory: Developing a new language with children for school building design. Build. Environ. 2021, 188, 107374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Kang, J.; Ma, H.; Wang, C. The effects of environmental sensitivity and noise sensitivity on soundscape evaluation. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramkissoon, H.; Van Der Veen, R.; Salaripour, A.; Reihani, Z.S.; Aflaki, A. The impact of sensory experiences on place attachment, place loyalty and civic participation: Evidence from Rasht, Iran. City Cult. Soc. 2024, 38, 100592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltenborn, B.P.; Bjerke, T. Associations between environmental value orientations and landscape preferences. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2002, 59, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Liu, J.; Albert, C.; Guo, X. Exploring the effects of soundscape perception on place attachment: A comparative study of residents and tourists. Appl. Acoust. 2024, 222, 110048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Wu, Y.; Xiao, Y.; Fu, W.; Zhuo, Z.; Konijnendijk van den Bosch, C.C.; Huang, Q.; Lan, S. More meaningful, more restorative? Linking local landscape characteristics and place attachment to restorative perceptions of urban park visitors. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2020, 197, 103763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, G.H.; Chipuer, H.M.; Bramston, P. Sense of place amongst adolescents and adults in two rural Australian towns: The discriminating features of place attachment, sense of community and place dependence in relation to place identity. J. Environ. Psychol. 2003, 23, 273–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheller, D.A.; Sterr, K.; Humpe, A.; Mess, F.; Bachner, J. Physical activity through place attachment: Understanding perceptions of children and adolescents on urban places by using photovoice and walking interviews. Health Place 2024, 90, 103361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fung, W.K.; Chung, K.K.H. Longitudinal association between children’s mastery motivation and cognitive school readiness: Executive functioning and social-emotional competence as potential mediators. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2023, 234, 105712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, F.; Xia, Z. Perceived discrimination and academic self-concept among left-behind children in China: The role of school belonging and classroom composition. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2023, 155, 107294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khotbehsara, E.M.; Somasundaraswaran, K.; Kolbe-Alexander, T.; Yu, R. The influence of spatial configuration on pedestrian movement behaviour in commercial streets of low-density cities. Ain Shams Eng. J. 2025, 16, 103184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liu, S.; Liu, K.; Bian, F. How does campus-scape influence university students’ restorative experiences: Evidences from simultaneously collected physiological and psychological data. Urban For. Urban Green. 2025, 107, 128779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Luo, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhu, Z.; Yao, X.; Li, Q.; Tarin, M.W.K.; Zheng, J.; Zhuo, Z. Relationships between students’ demographic characteristics, perceived naturalness and patterns of use associated with campus green space, and self-rated restoration and health. Urban For. Urban Green. 2022, 68, 127474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Du, J.; Chow, D. Perceived environmental factors and students’ mental wellbeing in outdoor public spaces of university campuses: A systematic scoping review. Build. Environ. 2024, 265, 112023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bianchi, E.; Bencharit, L.Z.; Murnane, E.L.; Altaf, B.; Douglas, I.P.; Landay, J.A.; Billington, S.L. Effects of architectural interventions on psychological, cognitive, social, and pro-environmental aspects of occupant well-being: Results from an immersive online study. Build. Environ. 2024, 253, 111293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, K.; Li, Z.; Zheng, S.; Qu, H. Quantifying environmental characteristics on psychophysiological restorative benefits of campus window views. Build. Environ. 2024, 262, 111822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, M.; Lu, W.; Li, N.; Geng, W. Exploring the relationship between library reading space height and user perception: A physiological and subjective analysis. Build. Environ. 2024, 253, 111307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, P.; Davies, F.; Zhang, Y.; Barrett, L. The impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning: Final results of a holistic, multi-level analysis. Build. Environ. 2015, 89, 118–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vivion, M.; Ftaïta, M.; Guida, A.; Mathy, F. Processing order in short-term memory is spatially biased in children. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2025, 252, 106171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barrett, P.; Zhang, Y.; Moffat, J.; Kobbacy, K. A holistic, multi-level analysis identifying the impact of classroom design on pupils’ learning. Build. Environ. 2013, 59, 678–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, D.J. A quantitative approach to the assessment of the environmental impact of building materials. Build. Environ. 1999, 34, 751–758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Severcan, Y.C.; Torun, A.O.; Defeyter, M.A.; Bingol, H.; Akin, I.Z. Associations of children’s mental wellbeing and the urban form characteristics of their everyday places. Cities 2025, 160, 105832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Den Bogerd, N.; Dijkstra, S.C.; Seidell, J.C.; Maas, J. Greenery in the university environment: Students’ preferences and perceived restoration likelihood. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0192429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Liu, C.; Yang, Y. A review of attention restoration theory: Implications for designing restorative environments. Sustainability 2024, 16, 3639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLenon, J.; Rogers, M.A. The fear of needles: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Adv. Nurs. 2019, 75, 30–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allah Yar, M.; Kazemi, F. The role of dish gardens on the physical and neuropsychological improvement of hospitalized children. Urban For. Urban Green. 2020, 53, 126713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, G.; Xiao, L.-R.; Chen, Y.-H.; Zhang, M.; Peng, K.-W.; Wu, H.-M. Association between physical activity and mental health problems among children and adolescents: A moderated mediation model of emotion regulation and gender. J. Affect. Disord. 2025, 369, 489–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jansson, M. Children’s perspectives on public playgrounds in two Swedish communities. Child. Youth Environ. 2008, 18, 88–109. Available online: https://pub.epsilon.slu.se/9410/7/Jansson_M_130201.pdf (accessed on 3 March 2023).

- Cui, J.; Meng, X.; Qi, S.; Fan, J.; Yu, W.; Liu, H.; Wang, X.; Zhang, Y. The impact of school activity space layout on children’s physical activity levels during recess: An agent-based model computational approach. Build. Environ. 2025, 271, 112585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, P.; Carstensen, T.A.; Jørgensen, G. Exploring the inclusion of children from a spatial perspective: An analytical framework of the correlation between physical environment and children’s inclusion in urban public spaces. Cities 2024, 153, 105293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulrich, R.S. View through a window may influence recovery from surgery. Science 1984, 224, 420–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopez, R.P.; Hynes, H.P. Obesity, physical activity, and the urban environment: Public health research needs. Environ. Health 2006, 5, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Huang, C. Using convolutional neural networks for image semantic segmentation and object detection. Syst. Soft Comput. 2024, 6, 200172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Wu, H.; Ma, X. Semantic-guided modeling of spatial relation and object co-occurrence for indoor scene recognition. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 270, 126415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B.; Wang, L.; Chen, T.; Kong, G.; Shuai, R.; Chen, P. The influence of interface proportions on visual guidance perception in node spaces. Build. Environ. 2025, 272, 112661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Heezik, Y.; Freeman, C.; Falloon, A.; Buttery, Y.; Heyzer, A. Relationships between childhood experience of nature and green/blue space use, landscape preferences, connection with nature and pro-environmental behavior. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2021, 213, 104135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diachenko, I.; Kalishchuk, S.; Zhylin, M.; Kyyko, A.; Volkova, Y. Color education: A study on methods of influence on memory. Heliyon 2022, 8, e11607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yuan, L. Analysis of the campus design based on the color idea of landscape space. In Civil Engineering and Urban Planning III; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014; pp. 59–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yildirim, K.; Akalin-Baskaya, A.; Hidayetoglu, M.L. Effects of indoor color on mood and cognitive performance. Build. Environ. 2007, 42, 3233–3240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimatani, K.; Nakayama, Y.; Takaguchi, K.; Iwayama, R.; Yoda-Tsumura, K.; Nakaoka, H.; Mori, C.; Suzuki, N. Relationship between living rooms with void spaces or partially high ceilings and psychological well-being: A cross-sectional study in Japan. Build. Environ. 2024, 258, 111596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehta, R.; Zhu, R. Creating when you have less: The impact of resource scarcity on product use creativity. J. Consum. Res. 2016, 42, 767–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Sirvent, J.L.; Fernández-Sotos, D.; Sánchez-Reolid, R.; de la Rosa López, F.; Fernández-Sotos, A.; Fernández-Caballero, A. Pre-occupancy evaluation of a virtual music school classroom: Influence of color and type of lighting on music performers. Build. Environ. 2023, 246, 110989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Chen, S.; Xu, H.; Kang, J. Effects of implanted wood components on environmental restorative quality of indoor informal learning spaces in college. Build. Environ. 2023, 245, 110890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, T.; Tang, X.; Li, K. Image clustering algorithm and psychological perception in historical building colour rating research: A case study of Guangzhou, China. Front. Archit. Res. 2025, 14, 1415–1435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Huang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shang, L.; Yang, C. Evaluating the impact of elementary school urban neighborhood color on children’s mentalization of emotions through multi-source data. Buildings 2024, 14, 3128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.; Wu, J. Sport tourist perceptions of destination image and revisit intentions: An adaption of Mehrabian-Russell’s environmental psychology model. Heliyon 2024, 10, e31810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, S. Emotional analysis of broadcasting and hosting speech by integrating grid PSO-SVR and PAD models. Int. J. Cogn. Comput. Eng. 2025, 6, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hideg, É.; Mihók, B.; Gáspár, J.; Schmidt, P.; Márton, A.; Báldi, A. Assessment in horizon scanning by various stakeholder groups using Osgood’s semantic differential scale—A methodological development. Futures 2021, 126, 102677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, O.C.S.; Landis, D.; Tzeng, D.Y.; Charles, E. Osgood’s continuing contributions to intercultural communication and far beyond! Int. J. Intercult. Relat. 2012, 36, 832–842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osgood, C.E. Dimensionality of the semantic space for communication via facial expressions. Scand. J. Psychol. 1966, 7, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taverner, J.; Vivancos, E.; Botti, V. A fuzzy appraisal model for affective agents adapted to cultural environments using the pleasure and arousal dimensions. Inf. Sci. 2021, 546, 74–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehrabian, A. Framework for a comprehensive description and measurement of emotional states. Genet. Soc. Gen. Psychol. Monogr. 1995, 121, 339–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehrabian, A. Pleasure-arousal-dominance: A general framework for describing and measuring individual differences in temperament. Curr. Psychol. 1996, 14, 261–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floyd, M.F. Pleasure, arousal, and dominance: Exploring affective determinants of recreation satisfaction. Leis. Sci. 1997, 19, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preißler, L.; Keck, J.; Krüger, B.; Munzert, J.; Schwarzer, G. Recognition of emotional body language from dyadic and monadic point-light displays in 5-year-old children and adults. J. Exp. Child Psychol. 2023, 235, 105713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, T.N.; Mazefsky, C.A.; Yu, L.; Zeglen, K.N.; Neece, C.L.; Pilkonis, P.A. The Emotion Dysregulation Inventory−Young Child: Psychometric properties and item response theory calibration in 2- to 5-year-olds. J. Am. Acad. Child Adolesc. Psychiatry 2024, 63, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, L.; Martins, M.; Correia, A.I.; Castro, S.L.; Schellenberg, E.G.; Lima, C.F. Does music training improve emotion recognition and cognitive abilities? Longitudinal and correlational evidence from children. Cognition 2025, 259, 106102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- England-Mason, G.; Andrews, K.; Atkinson, L.; Gonzalez, A. Emotion socialization parenting interventions targeting emotional competence in young children: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 100, 102252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacso, S.A.; Nilsen, E.S. Children’s use of verbal and nonverbal feedback during communicative repair: Associations with executive functioning and emotion knowledge. Cogn. Dev. 2022, 63, 101199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galler, M.; Grendstad, Å.R.; Ares, G.; Varela, P. Capturing food-elicited emotions: Facial decoding of children’s implicit and explicit responses to tasted samples. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 99, 104551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lercher, P.; Dzhambov, A.M.; Waye, K.P. Environmental perceptions, self-regulation, and coping with noise mediate the associations between children’s physical environment and sleep and mental health problems. Environ. Res. 2025, 264 Pt 2, 120414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gitelman, V.; Levi, S.; Carmel, R.; Korchatov, A.; Hakkert, S. Exploring patterns of child pedestrian behaviors at urban intersections. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2019, 122, 36–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibes, D.C.; Forestell, C.A. The role of campus greenspace and meditation on college students’ mood disturbance. J. Am. Coll. Health 2022, 70, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Günaydın, A.S.; Yücekaya, M. An investigation of sustainable transportation model in campus areas with space syntax method. ICONARP Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2020, 8, 262–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Zhang, M. Effects of classroom design characteristics on children’s physiological and psychological responses: A virtual reality experiment. Build. Environ. 2025, 267 Pt B, 112274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, D.; Rueda-Plata, D.; Acevedo, A.B.; Duque, J.C.; Ramos-Pollán, R.; Betancourt, A.; García, S. Automatic detection of building typology using deep learning methods on street level images. Build. Environ. 2020, 177, 106805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, F.; Kang, J. Spatial adaptation in children with autism—A study based on behavioural dynamic video data. J. Build. Eng. 2024, 98, 111228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, B.; Yu, Z.J.; Zhou, P.; Huang, G. Optimal zoning for building zonal model of large-scale indoor space. Build. Environ. 2022, 225, 109669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Y.; Wang, J.; Xi, C.; Han, L.; Feng, Z.; Cao, S.-J. Investigation of heat stress on urban roadways for commuting children and mitigation strategies from the perspective of urban design. Urban Clim. 2023, 49, 101564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffith, Z.M.; Polet, J.; Lintunen, T.; Hamilton, K.; Hagger, M.S. Social cognition, personality and social-political correlates of health behaviors: Application of an integrated theoretical model. Soc. Sci. Med. 2024, 347, 116779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Black, J.T.; Shakir, M.Z. Emotion on the edge: An evaluation of feature representations and machine learning models. Nat. Lang. Process. J. 2025, 10, 100127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon-Uribe, S.; Morales-Hernandez, L.A.; Guzman-Sandoval, V.M.; Dominguez-Trejo, B.; Cruz-Albarran, I.A. Emotion detection based on infrared thermography: A review of machine learning and deep learning algorithms. Infrared Phys. Technol. 2025, 145, 105669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A.; Poulose, A. Electroencephalogram-based emotion recognition: A comparative analysis of supervised machine learning algorithms. Data Sci. Manag. 2025, 8, 342–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esfahani, S.H.N.; Adda, M. Classical machine learning and large models for text-based emotion recognition. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2024, 241, 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y. Research on implicit emotion recognition and classification in literary works in the context of machine learning. Alex. Eng. J. 2025, 115, 577–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subasi, A.; Qaisar, S.M. EEG-based emotion recognition using AR burg and ensemble machine learning models. In Artificial Intelligence Applications in Healthcare and Medicine; Subasi, A., Qaisar, S.M., Nisar, H., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2025; pp. 303–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bisogni, C.; Cimmino, L.; De Marsico, M.; Hao, F.; Narducci, F. Emotion recognition at a distance: The robustness of machine learning based on hand-crafted facial features vs deep learning models. Image Vis. Comput. 2023, 136, 104724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garg, M.; Saxena, C. Emotion detection from text data using machine learning for human behavior analysis. In Computational Intelligence Methods for Sentiment Analysis in Natural Language Processing Applications; Hemanth, D.J., Ed.; Morgan Kaufmann: Burlington, MA, USA, 2024; pp. 129–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target Layer | Guideline Layer | Factor Layer |

|---|---|---|

| Elementary school campus space | Color richness B1 | Number of colors C1 |

| Primary color ratio C2 | ||

| Color Harmony Type C3 | ||

| Visual Impact B2 | Hue Contrast C4 | |

| Saturation Contrast C5 | ||

| Brightness Contrast C6 | ||

| Color Performance B3 | Hue Index C7 | |

| Saturation Index C8 | ||

| Brightness Index C9 | ||

| Color warmth and coolness C10 |

| Static Behavior | Dynamic Behavior | Individual Behavior | Group Behavior | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Percentage | Total | Percentage | Total | Percentage | Total | Percentage | |||

| Outside space | 173 | 41% | 239 | 51% | 203 | 49% | 209 | 44% | 412 | |

| Internal space | Learning Zone | 123 | 29% | 36 | 8% | 70 | 17% | 89 | 19% | 159 |

| Recreational areas | 33 | 8% | 64 | 14% | 31 | 8% | 66 | 14% | 97 | |

| Active Area | 90 | 21% | 126 | 27% | 108 | 26% | 108 | 23% | 216 | |

| Total | 419 | 465 | 412 | 472 | 884 | |||||

| Distribution of Space | |

|---|---|

| Arousal |  |

| Dominance |  |

| Pleasure |  |

| Number of Colors C1 | Main Color Proportion C2 | Color Harmony Type C3 | Hue Contrast C4 | Saturation Contrast C5 | Luminance Contrast C6 | Hue Index C7 | Saturation Index C8 | Brightness Index C9 | Color Warmth and Coolness C10 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Table and chair appliance | 0.164 (0.000 ***) | −0.035 (0.002 ***) | −0.049 (0.000 ***) | −0.233 (0.000 ***) | −0.021 (0.071 *) | −0.08 (0.000 ***) | −0.238 (0.000 ***) | −0.056 (0.000 ***) | 0.219 (0.000 ***) | −0.077 (0.000 ***) |

| Cabinet furniture | −0.128 (0.000 ***) | −0.075 (0.000 ***) | 0.039 (0.001 ***) | −0.115 (0.000 ***) | −0.046 (0.000 ***) | −0.178 (0.000 ***) | −0.186 (0.000 ***) | 0.207 (0.000 ***) | 0.258 (0.000 ***) | 0.244 (0.000 ***) |

| Floor paving | −0.264 (0.000 ***) | −0.125 (0.000 ***) | −0.414 (0.000 ***) | −0.286 (0.000 ***) | −0.366 (0.000 ***) | −0.227 (0.000 ***) | −0.407 (0.000 ***) | −0.385 (0.000 ***) | 0.04 (0.000 ***) | 0.106 (0.000 ***) |

| ceiling | −0.02 (0.080 *) | 0.344 (0.000 ***) | −0.177 (0.000 ***) | −0.248 (0.000 ***) | −0.192 (0.000 ***) | −0.072 (0.000 ***) | −0.293 (0.000 ***) | −0.234 (0.000 ***) | −0.019 (0.100 *) | 0.119 (0.000 ***) |

| Enclose the wall elevation | −0.122 (0.000 ***) | −0.119 (0.000 ***) | −0.419 (0.000 ***) | −0.377 (0.000 ***) | −0.14 (0.000 ***) | −0.258 (0.000 ***) | −0.449 (0.000 ***) | −0.051 (0.000 ***) | 0.261 (0.000 ***) | 0.018 (0.114) |

| Door and window construction | −0.201 (0.000 ***) | −0.02 (0.076 *) | −0.338 (0.000 ***) | −0.239 (0.000 ***) | −0.271 (0.000 ***) | −0.203 (0.000 ***) | −0.297 (0.000 ***) | −0.228 (0.000 ***) | 0.179 (0.000 ***) | 0.025 (0.027 **) |

| Facilities and decor | −0.017 (0.141) | 0.318 (0.000 ***) | −0.052 (0.000 ***) | −0.209 (0.000 ***) | 0.149 (0.000 ***) | 0.122 (0.000 ***) | −0.225 (0.000 ***) | 0.362 (0.000 ***) | 0.011 (0.334) | 0.306 (0.000 ***) |

| Indoor greening | 0.524 (0.000 ***) | 0.167 (0.000 ***) | 0.324 (0.000 ***) | −0.079 (0.000 ***) | 0.463 (0.000 ***) | −0.025 (0.025 **) | 0.061 (0.000 ***) | −0.002 (0.891) | 0.091 (0.000 ***) | 0.064 (0.000 ***) |

| Building elevation | −0.09 (0.000 ***) | 0.091 (0.000 ***) | 0.009 (0.426) | −0.016 (0.157) | 0.005 (0.661) | −0.12 (0.000 ***) | −0.003 (0.784) | −0.054 (0.000 ***) | 0.038 (0.001 ***) | 0.204 (0.000 ***) |

| Floor paving | −0.12 (0.000 ***) | −0.145 (0.000 ***) | 0.253 (0.000 ***) | 0.166 (0.000 ***) | 0.208 (0.000 ***) | 0.08 (0.000 ***) | 0.168 (0.000 ***) | −0.023 (0.041 **) | −0.046 (0.000 ***) | 0.047 (0.000 ***) |

| Road path | 0.133 (0.000 ***) | 0.112 (0.000 ***) | 0.255 (0.000 ***) | 0.11 (0.000 ***) | −0.066 (0.000 ***) | 0.025 (0.030 **) | 0.49 (0.000 ***) | −0.081 (0.000 ***) | −0.24 (0.000 ***) | −0.17 (0.000 ***) |

| playground | 0.049 (0.000 ***) | −0.129 (0.000 ***) | 0.218 (0.000 ***) | 0.237 (0.000 ***) | 0.32 (0.000 ***) | 0.026 (0.023 **) | 0.169 (0.000 ***) | 0.011 (0.336) | −0.094 (0.000 ***) | 0.025 (0.026 **) |

| Building elevation | 0.34 (0.000 ***) | 0.094 (0.000 ***) | −0.025 (0.031 **) | 0.29 (0.000 ***) | 0.063 (0.000 ***) | 0.407 (0.000 ***) | 0.311 (0.000 ***) | 0.085 (0.000 ***) | −0.115 (0.000 ***) | −0.27 (0.000 ***) |

| Enclosure construction | −0.084 (0.000 ***) | −0.165 (0.000 ***) | 0.362 (0.000 ***) | 0.357 (0.000 ***) | 0.063 (0.000 ***) | −0.033 (0.003 ***) | 0.406 (0.000 ***) | −0.005 (0.664) | −0.188 (0.000 ***) | −0.037 (0.001 ***) |

| Facilities guide system | −0.019 (0.102) | −0.083 (0.000 ***) | −0.132 (0.000 ***) | 0.075 (0.000 ***) | −0.028 (0.013 **) | 0.511 (0.000 ***) | 0.051 (0.000 ***) | 0.058 (0.000 ***) | 0.046 (0.000 ***) | −0.148 (0.000 ***) |

| Green landscape | −0.05 (0.000 ***) | −0.08 (0.000 ***) | 0.301 (0.000 ***) | 0.334 (0.000 ***) | −0.062 (0.000 ***) | 0.296 (0.000 ***) | 0.523 (0.000 ***) | 0.058 (0.000 ***) | −0.267 (0.000 ***) | −0.289 (0.000 ***) |

| Sky view | 0.158 (0.000 ***) | −0.074 (0.000 ***) | 0.523 (0.000 ***) | 0.566 (0.000 ***) | 0.329 (0.000 ***) | 0.196 (0.000 ***) | 0.49 (0.000 ***) | 0.006 (0.600) | −0.087 (0.000 ***) | −0.225 (0.000 ***) |

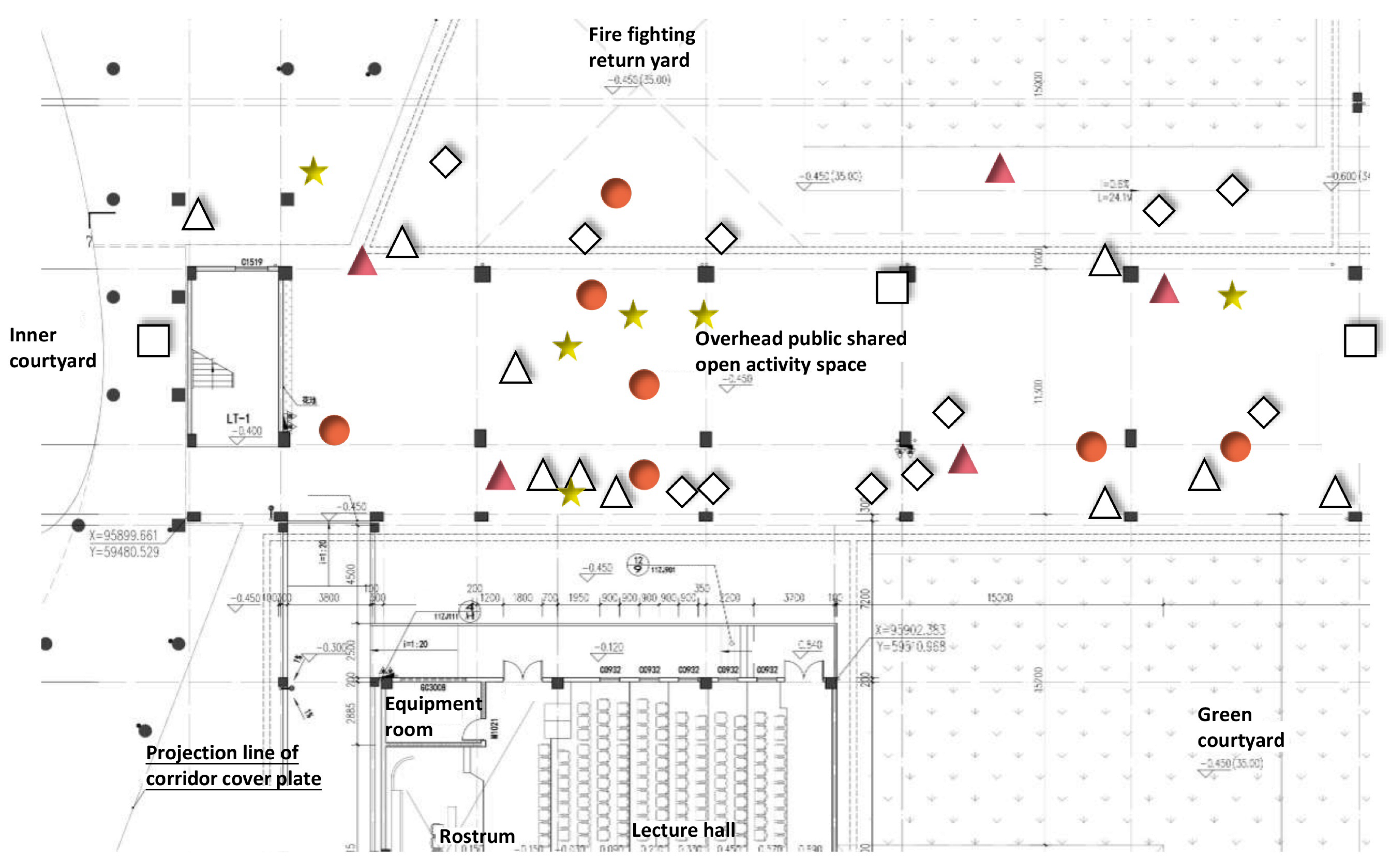

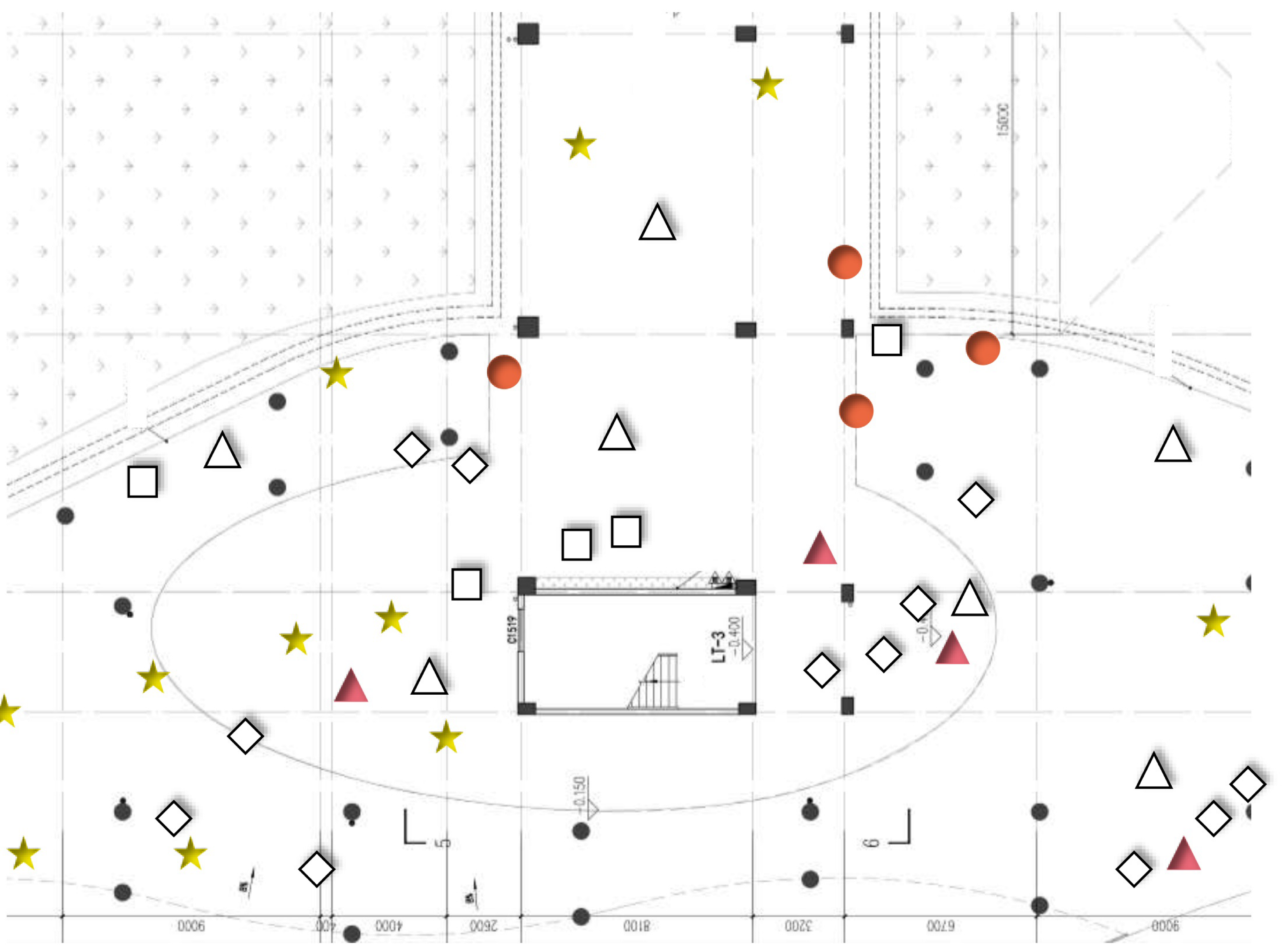

| Space | Behavioral Mapping | Activity Frequency/Spatial Elements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Building facade | Inner court area |  |  |

|  | ||

| Motor area |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Activity area |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Overhead area |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Outdoor characteristics district |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Enclosed member |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Motion path |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Public sports facilities |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Unsteady embellishment |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Space | Behavioral Maps | Activity Frequency/Spatial Features | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Learning area | Library |  |  |

|  | ||

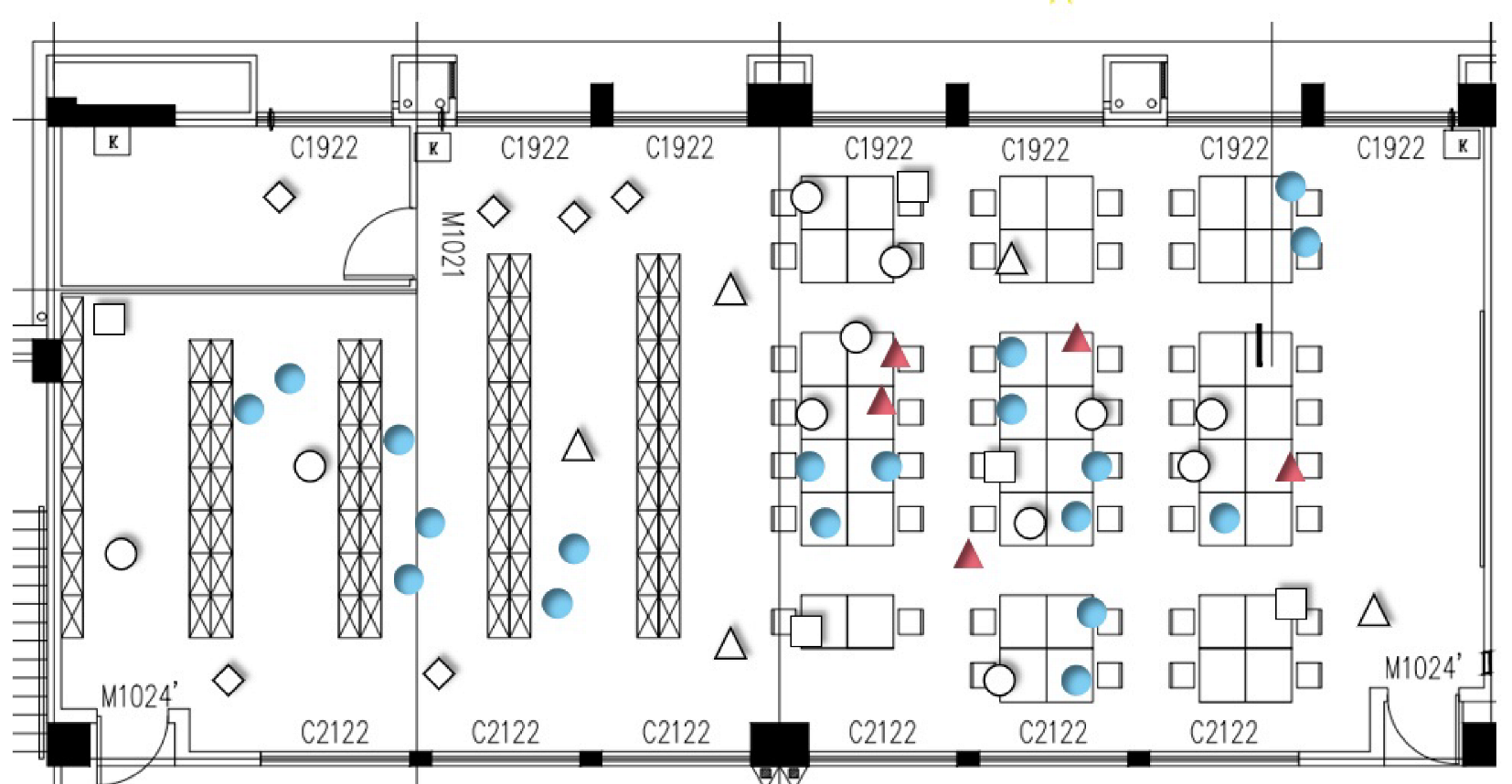

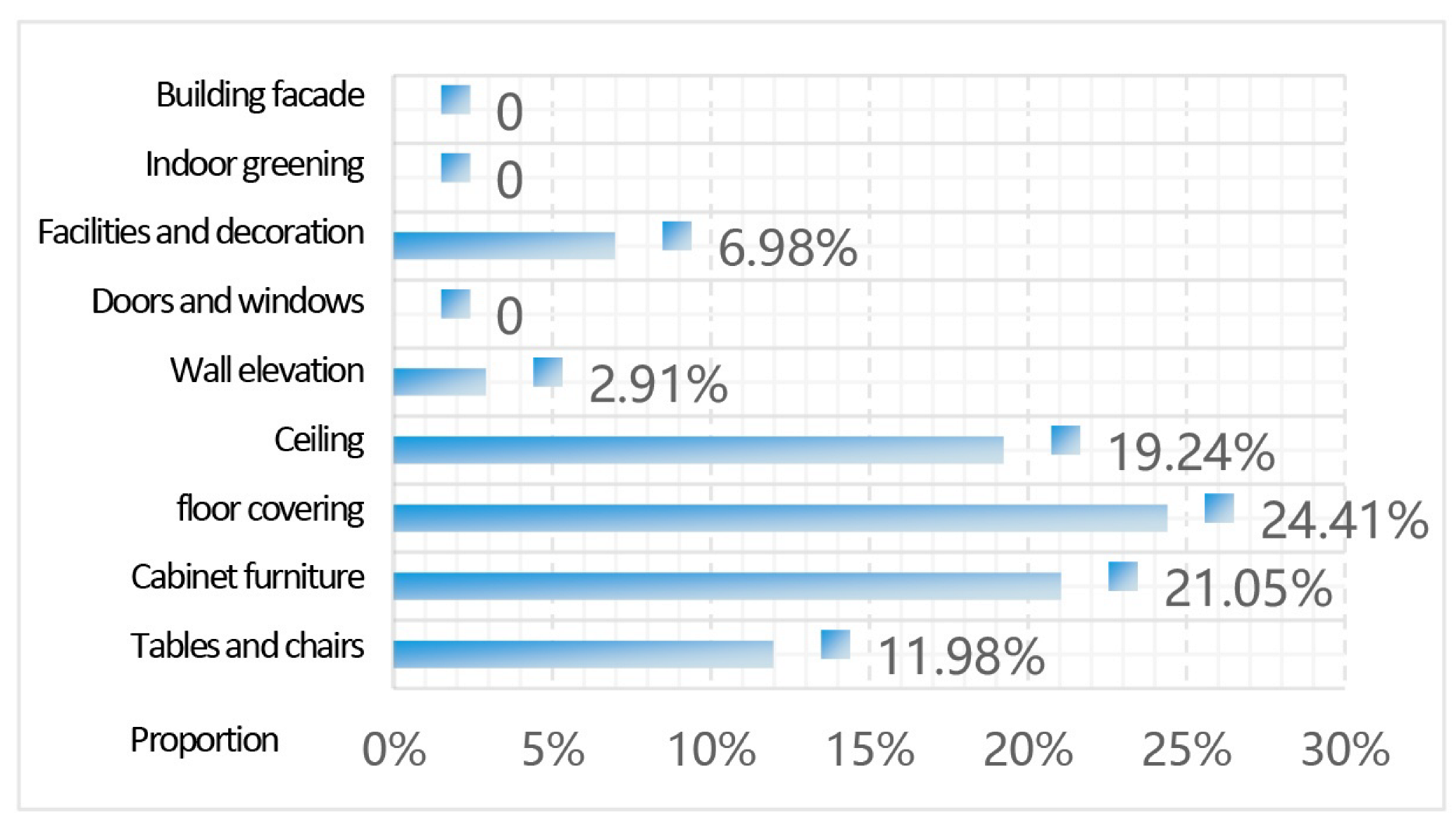

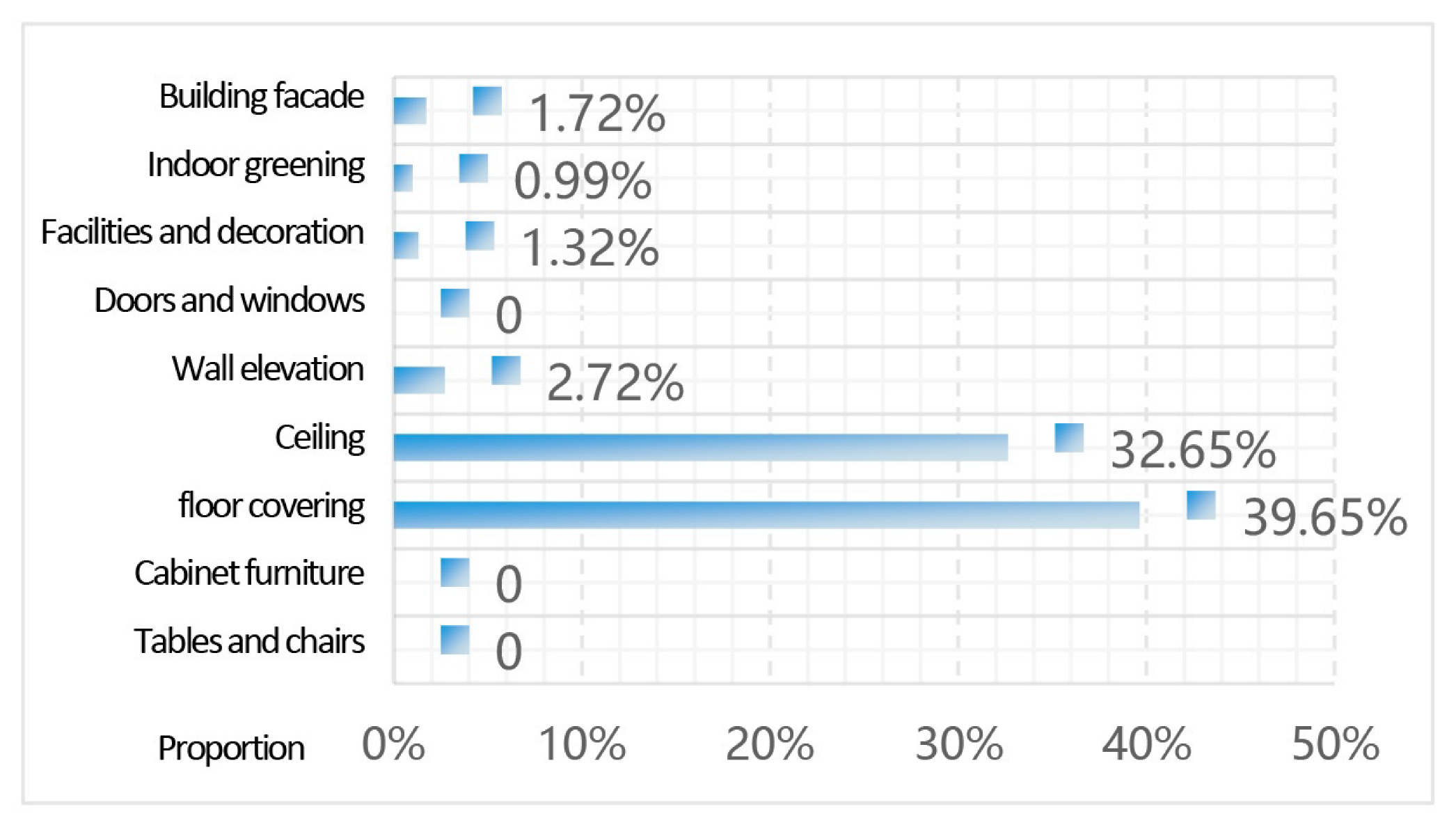

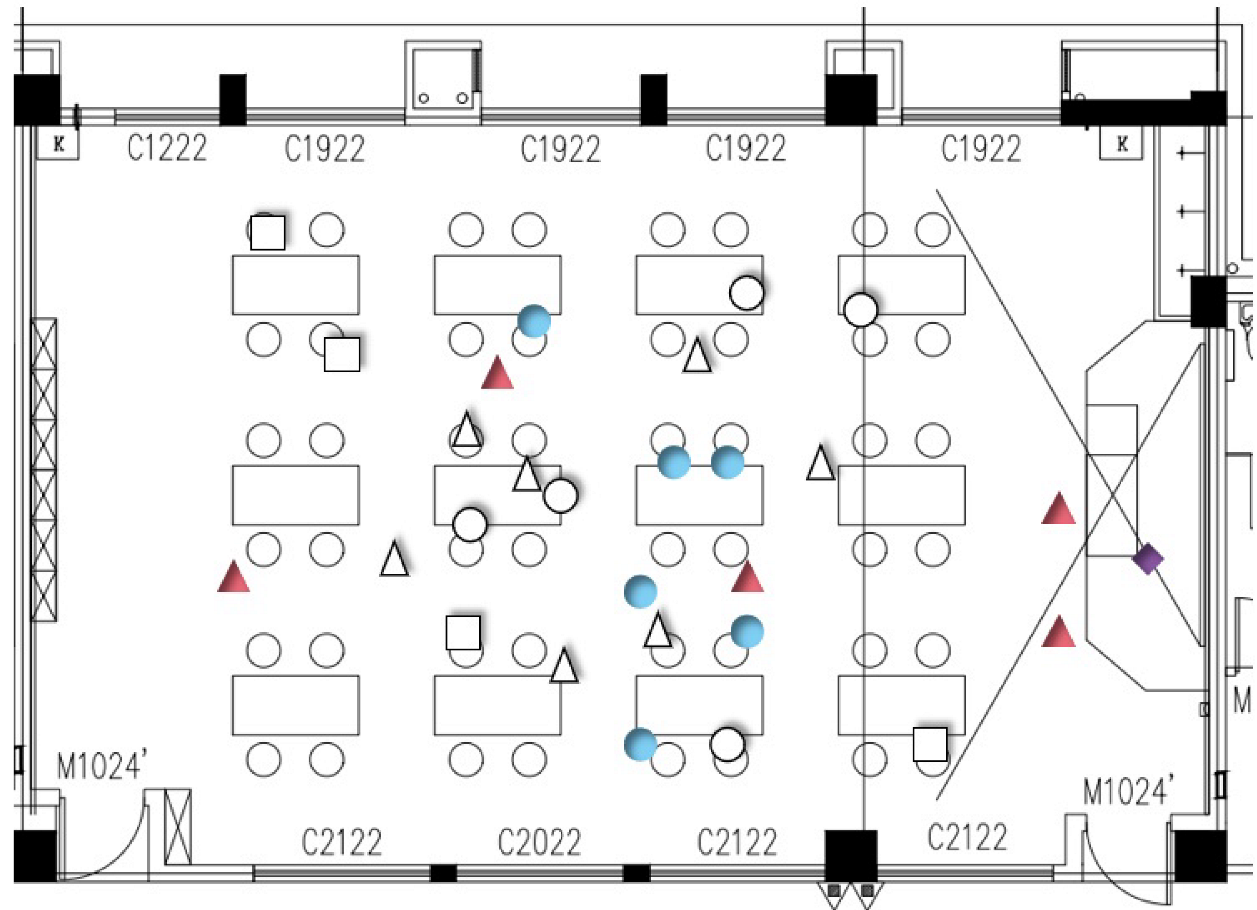

| Study classroom |  |  | |

|  | ||

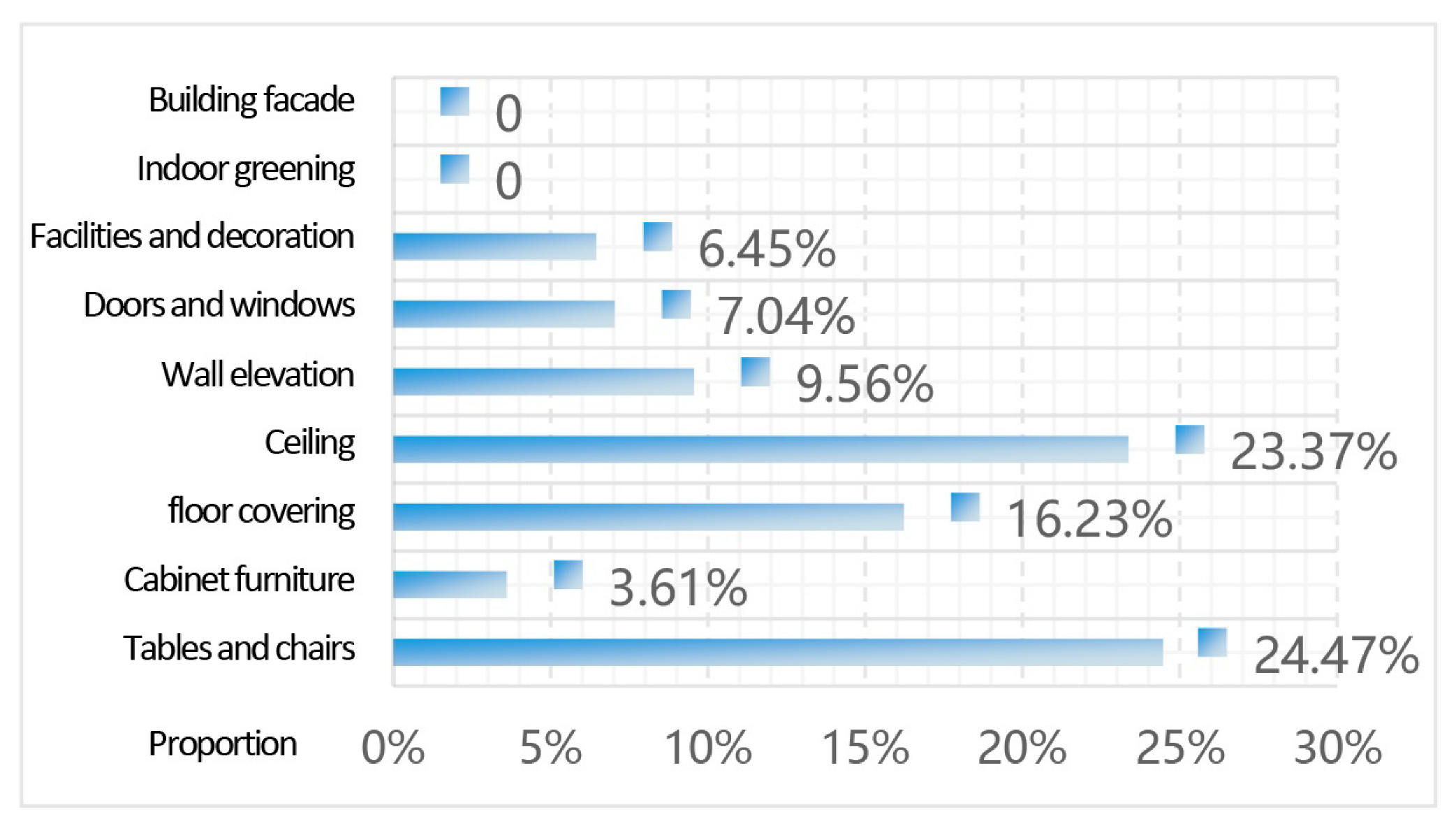

| Multifunctional classroom |  |  | |

|  | ||

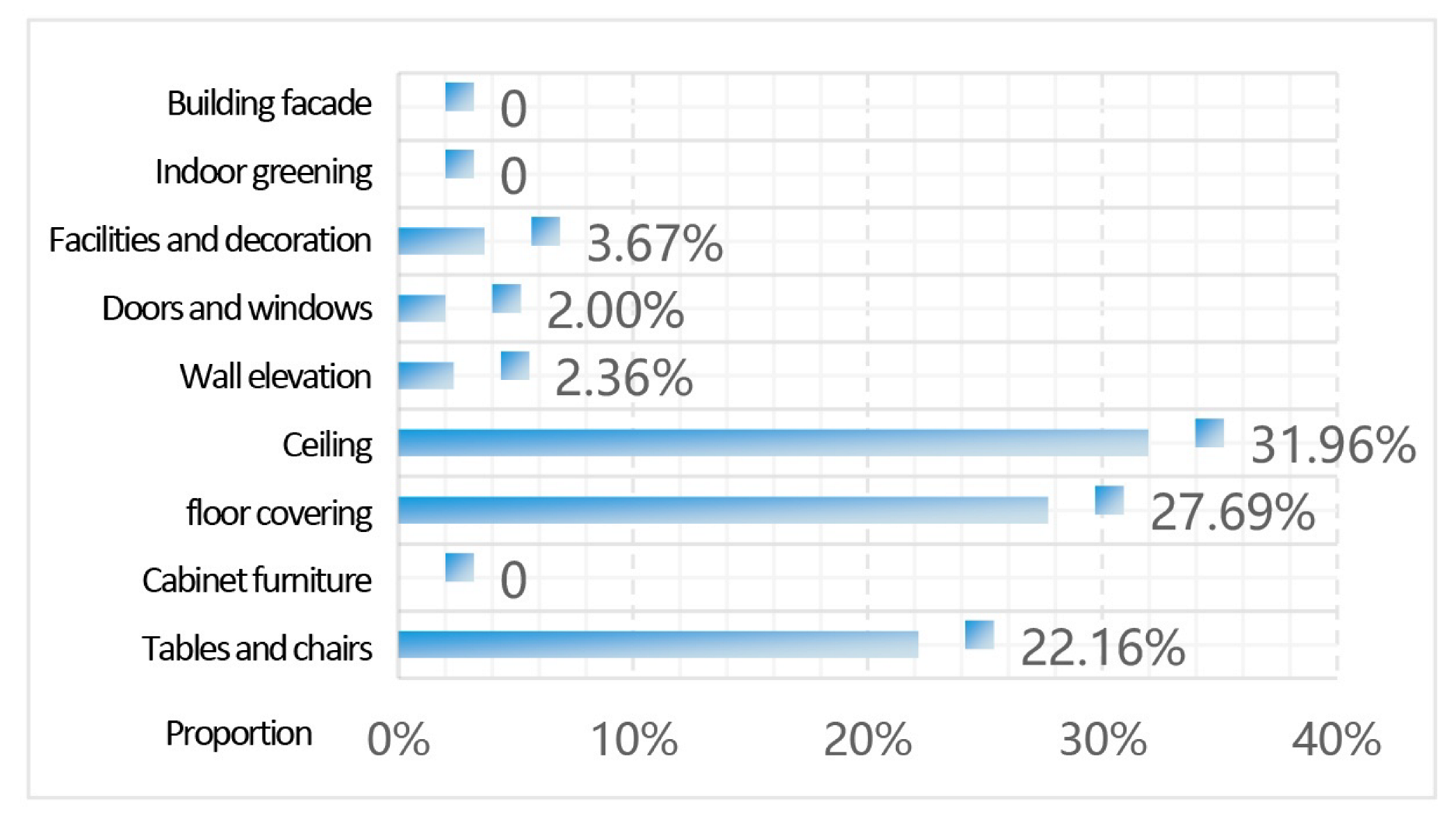

| Lecture hall |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Behavioral Map | Behavior Map | Activity Frequency | Spatial Elements | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Leisure area | Restrooms |  |  |  |

| ||||

| Cafeteria |  |  |  | |

| ||||

| Atrium space |  |  |  | |

| ||||

| Behavioral Map | Behavior Map | Activity Frequency/Spatial Elements | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Activity area | Plantation |  |  |

|  | ||

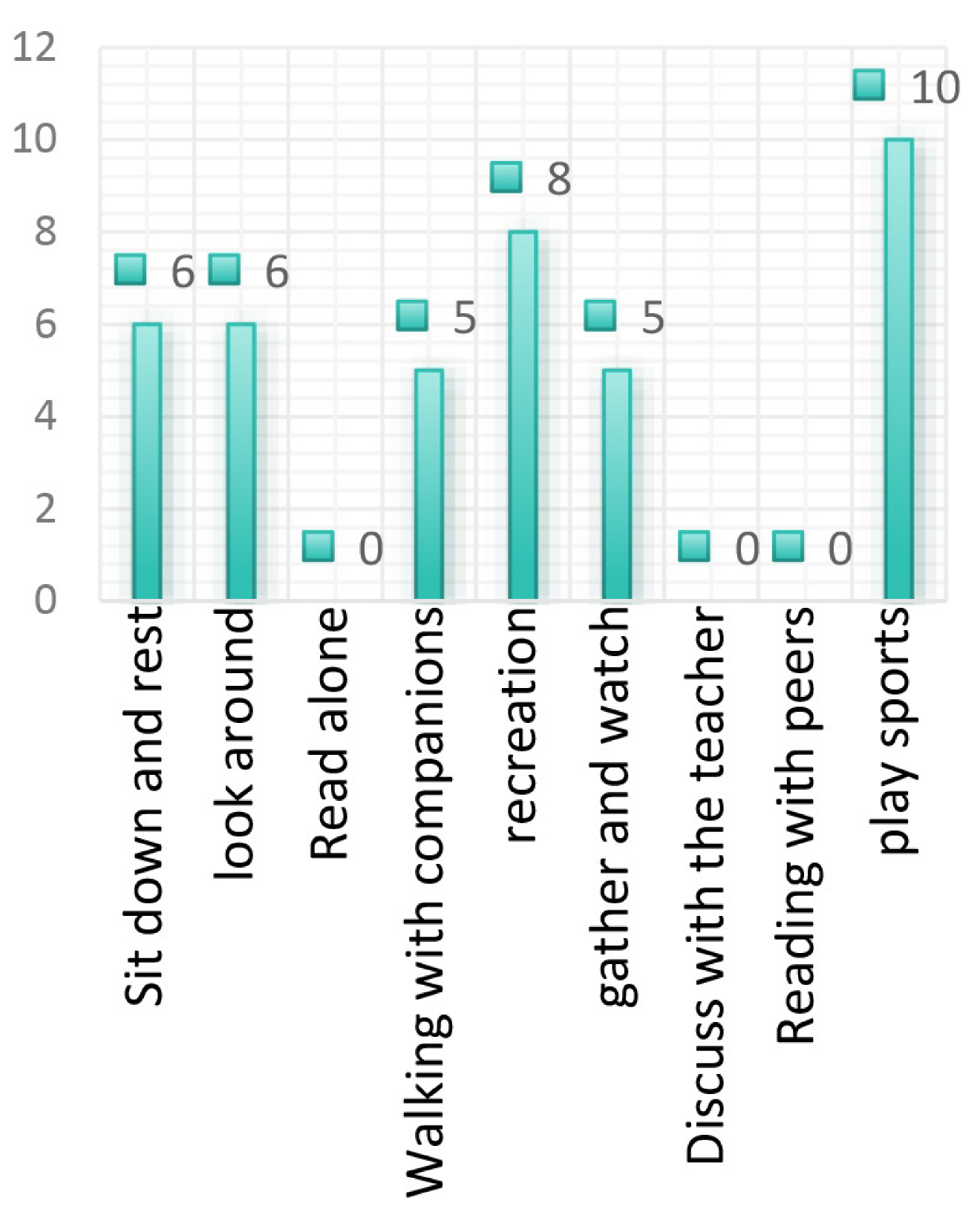

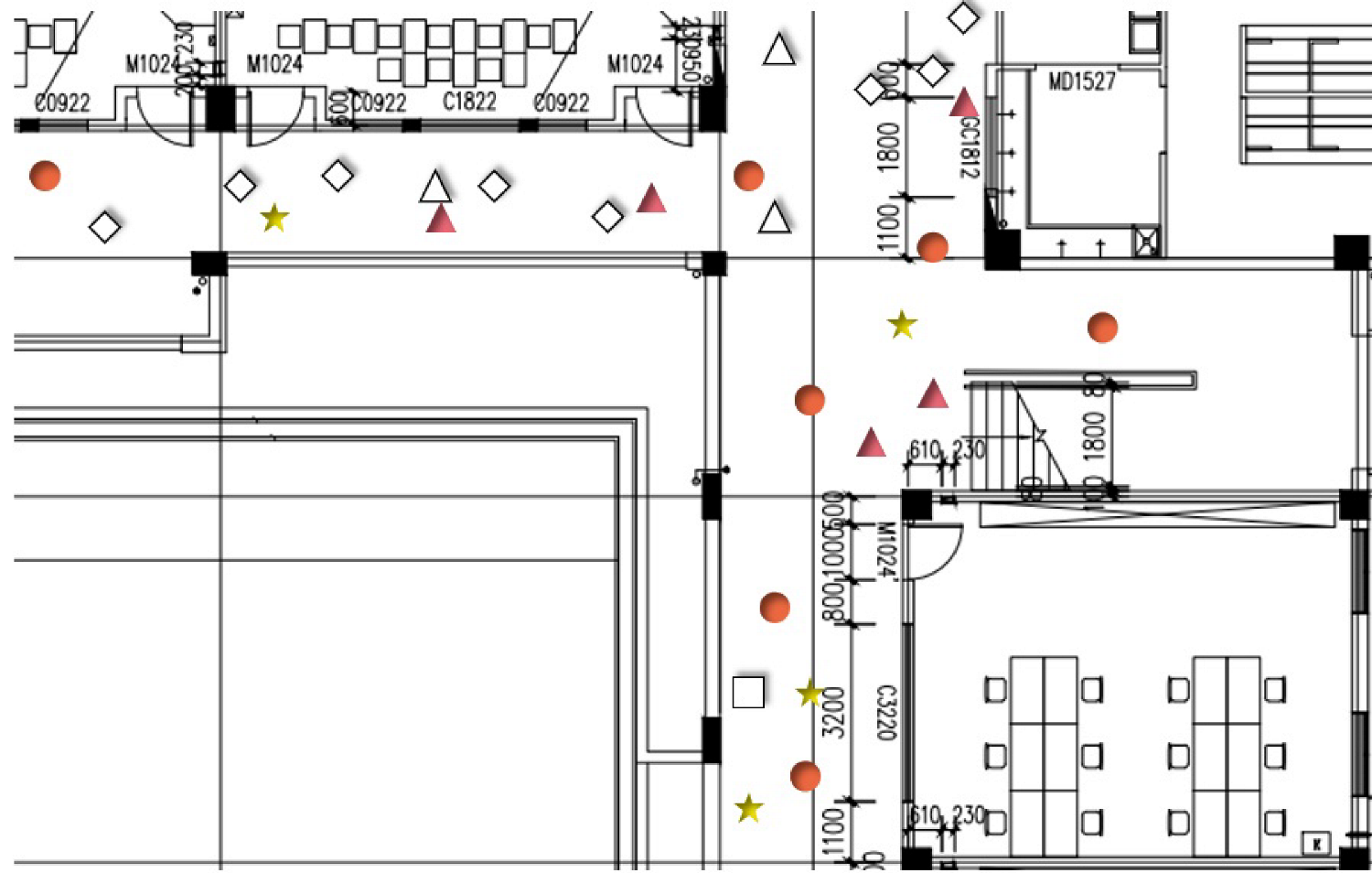

| Playground |  |  | |

|  | ||

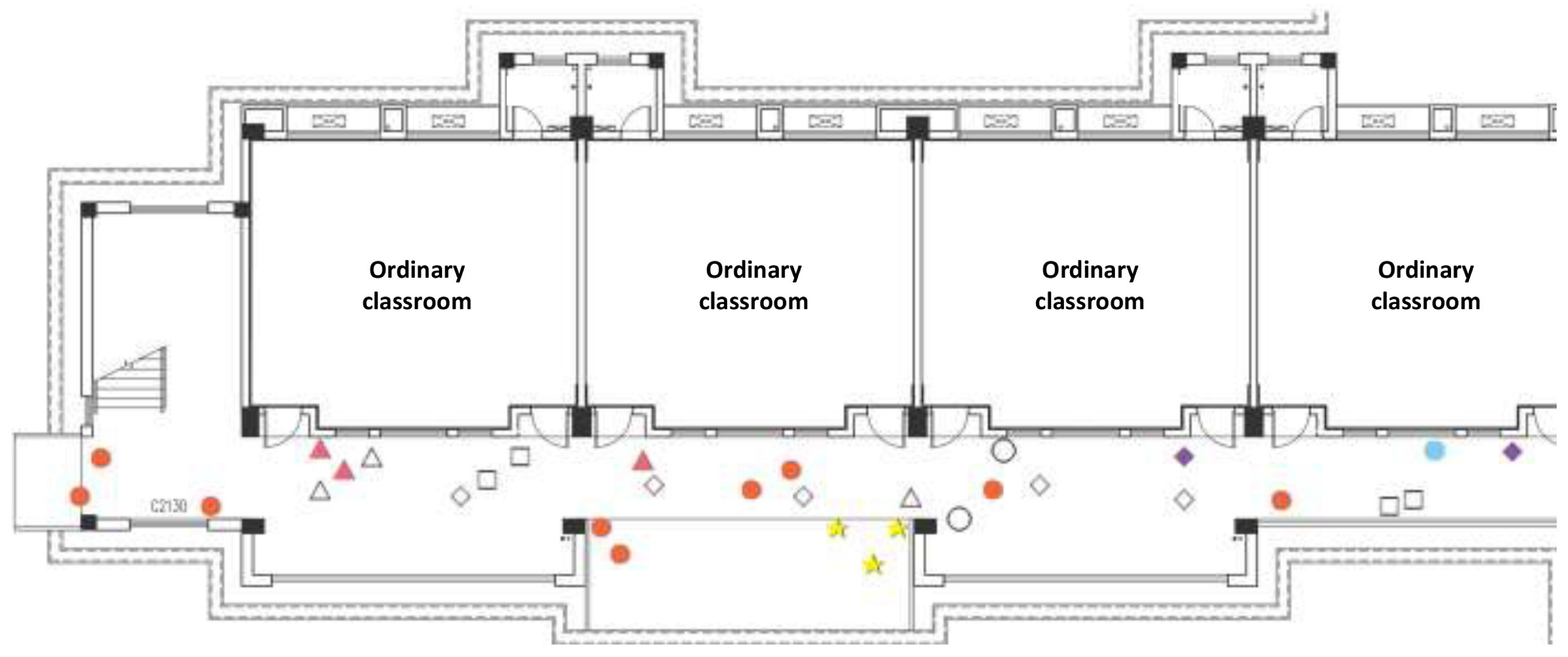

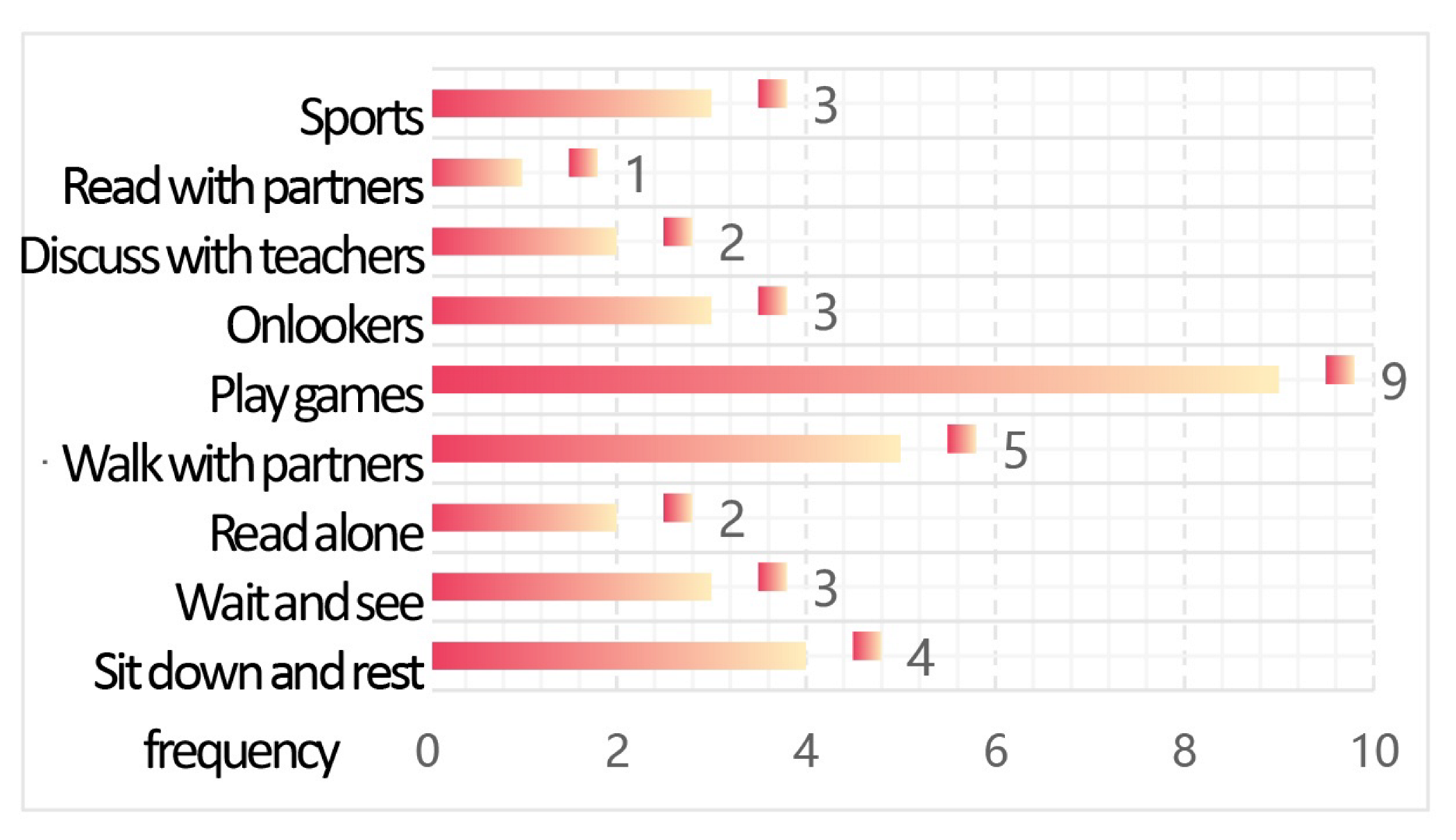

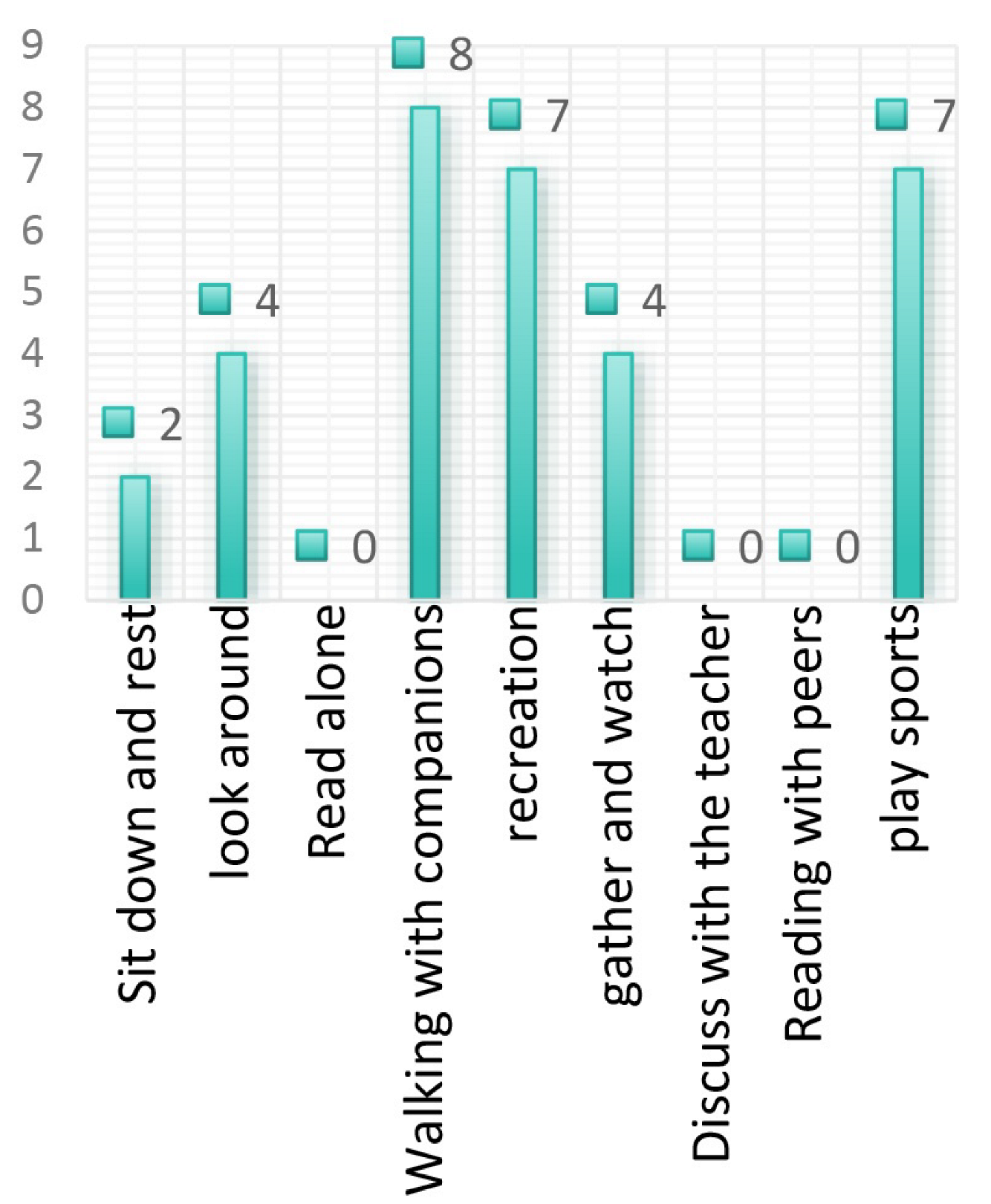

| Corridor space |  |  | |

|  | ||

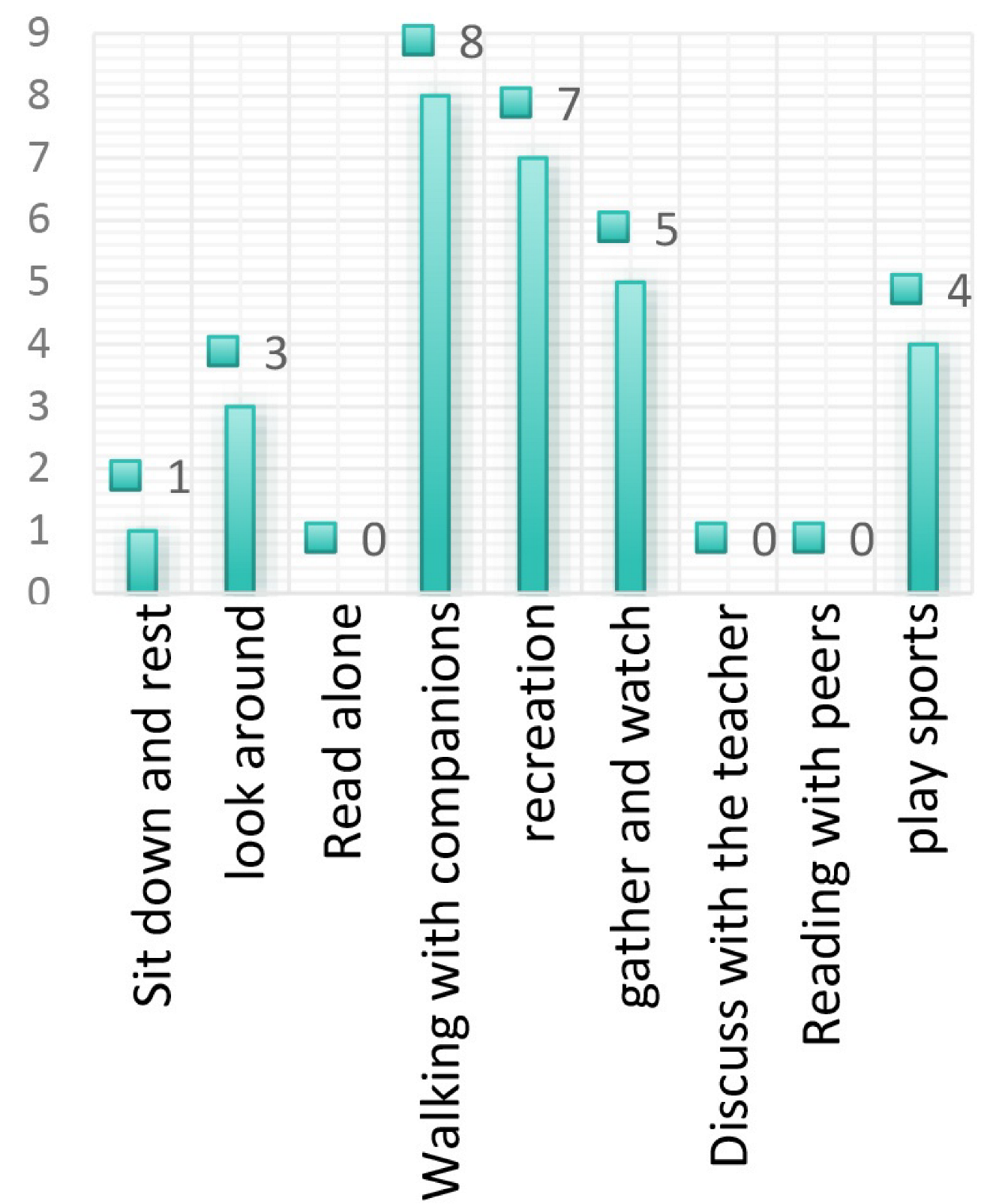

| Stairwells |  |  | |

|  | ||

| Shared Activity Space |  |  | |

|  | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, R.; Li, B.; Huang, Q.; Peng, Z.; Xu, Y.; Tang, L.; Ouyang, Z.; Zhang, X.; Shang, L. Spatial Optimization of Primary School Campuses from the Perspective of Children’s Emotional Behavior: A Deep Learning and Machine Learning Approach. Buildings 2025, 15, 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234281

Zhang R, Li B, Huang Q, Peng Z, Xu Y, Tang L, Ouyang Z, Zhang X, Shang L. Spatial Optimization of Primary School Campuses from the Perspective of Children’s Emotional Behavior: A Deep Learning and Machine Learning Approach. Buildings. 2025; 15(23):4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234281

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Ruiying, Binghuan Li, Qian Huang, Zhimou Peng, Yixun Xu, Li Tang, Zhiyue Ouyang, Xinyue Zhang, and Lan Shang. 2025. "Spatial Optimization of Primary School Campuses from the Perspective of Children’s Emotional Behavior: A Deep Learning and Machine Learning Approach" Buildings 15, no. 23: 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234281

APA StyleZhang, R., Li, B., Huang, Q., Peng, Z., Xu, Y., Tang, L., Ouyang, Z., Zhang, X., & Shang, L. (2025). Spatial Optimization of Primary School Campuses from the Perspective of Children’s Emotional Behavior: A Deep Learning and Machine Learning Approach. Buildings, 15(23), 4281. https://doi.org/10.3390/buildings15234281