Assessment of Object-Level Flood Impact Considering Pump Station Operations in Coastal Urban Areas

Abstract

1. Introduction

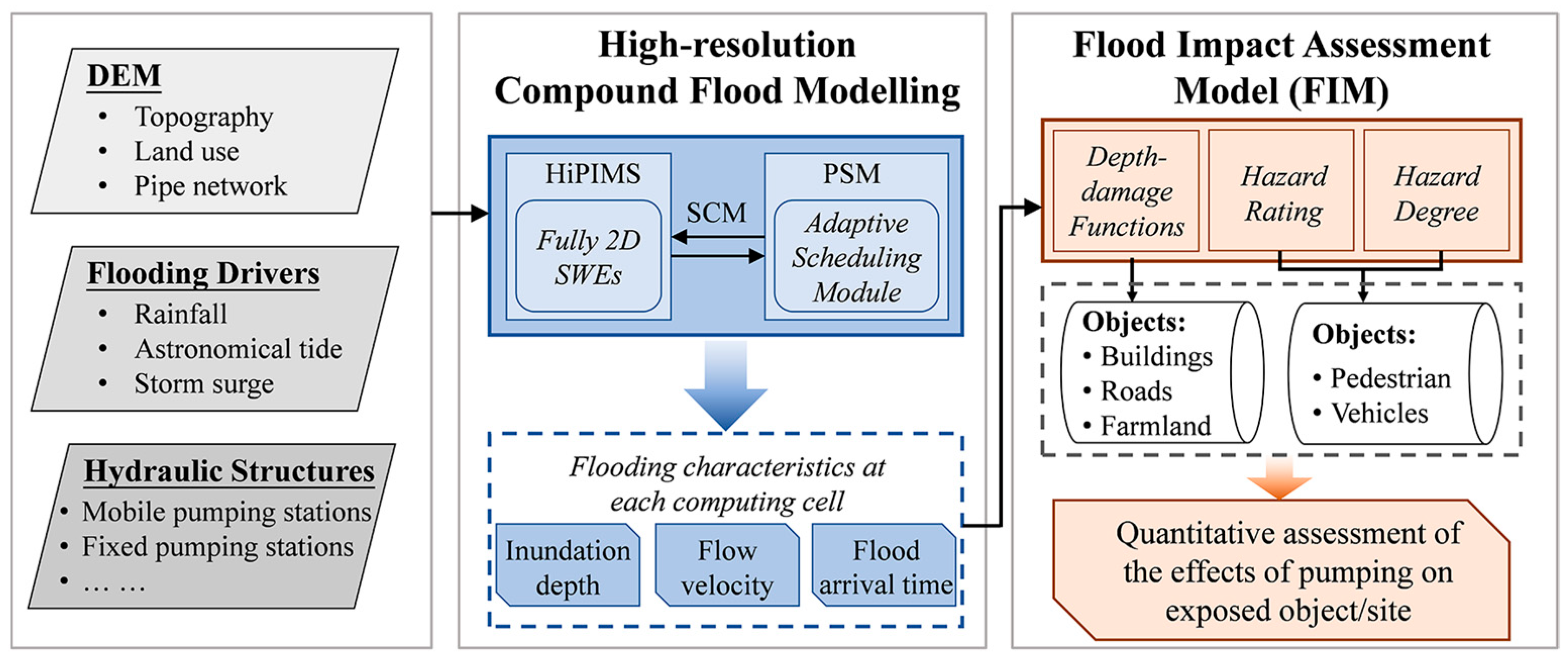

2. Materials and Methods

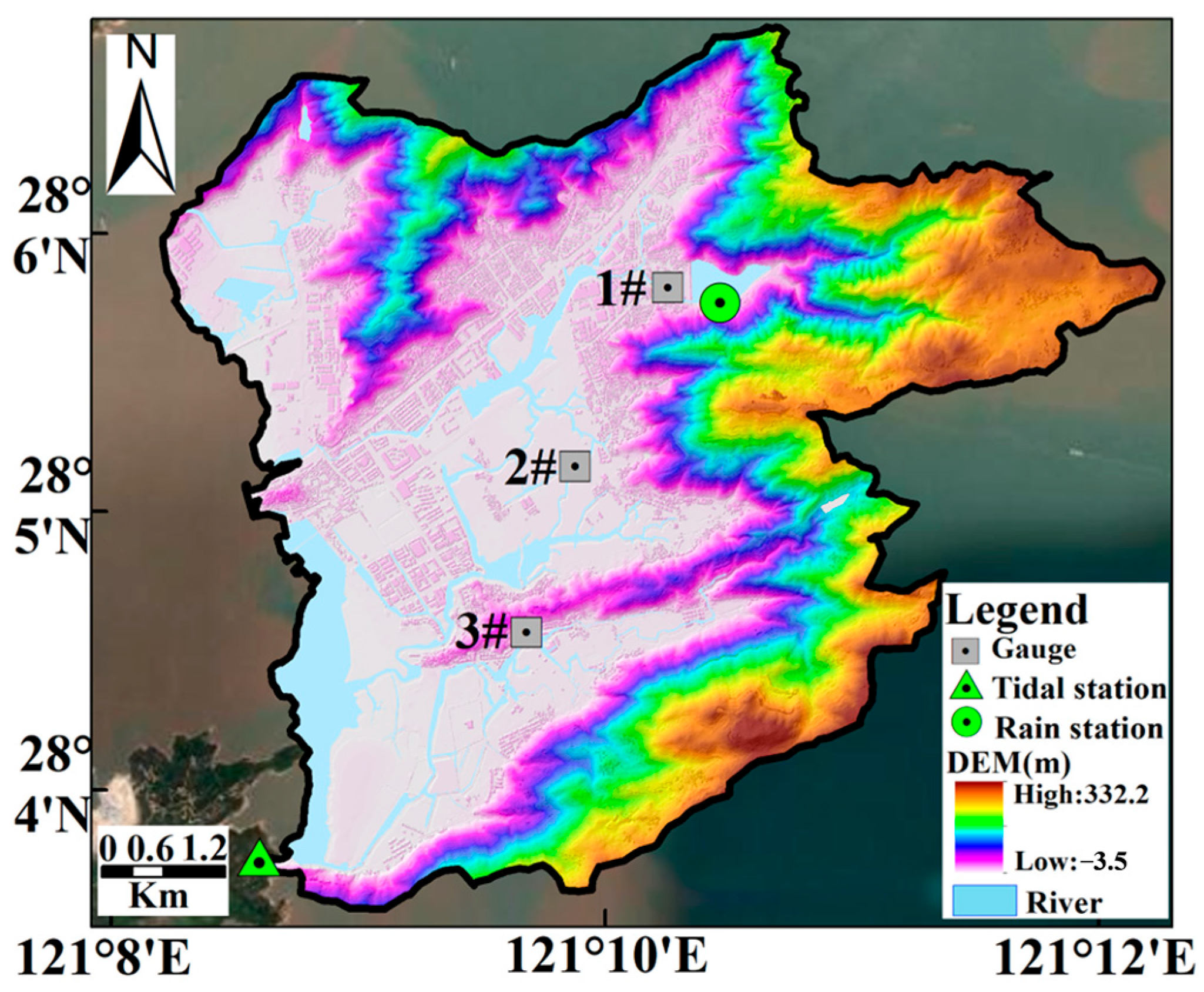

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Numerical Methods

2.2.1. Hydrodynamic Model

2.2.2. Pumping System Model (PSM)

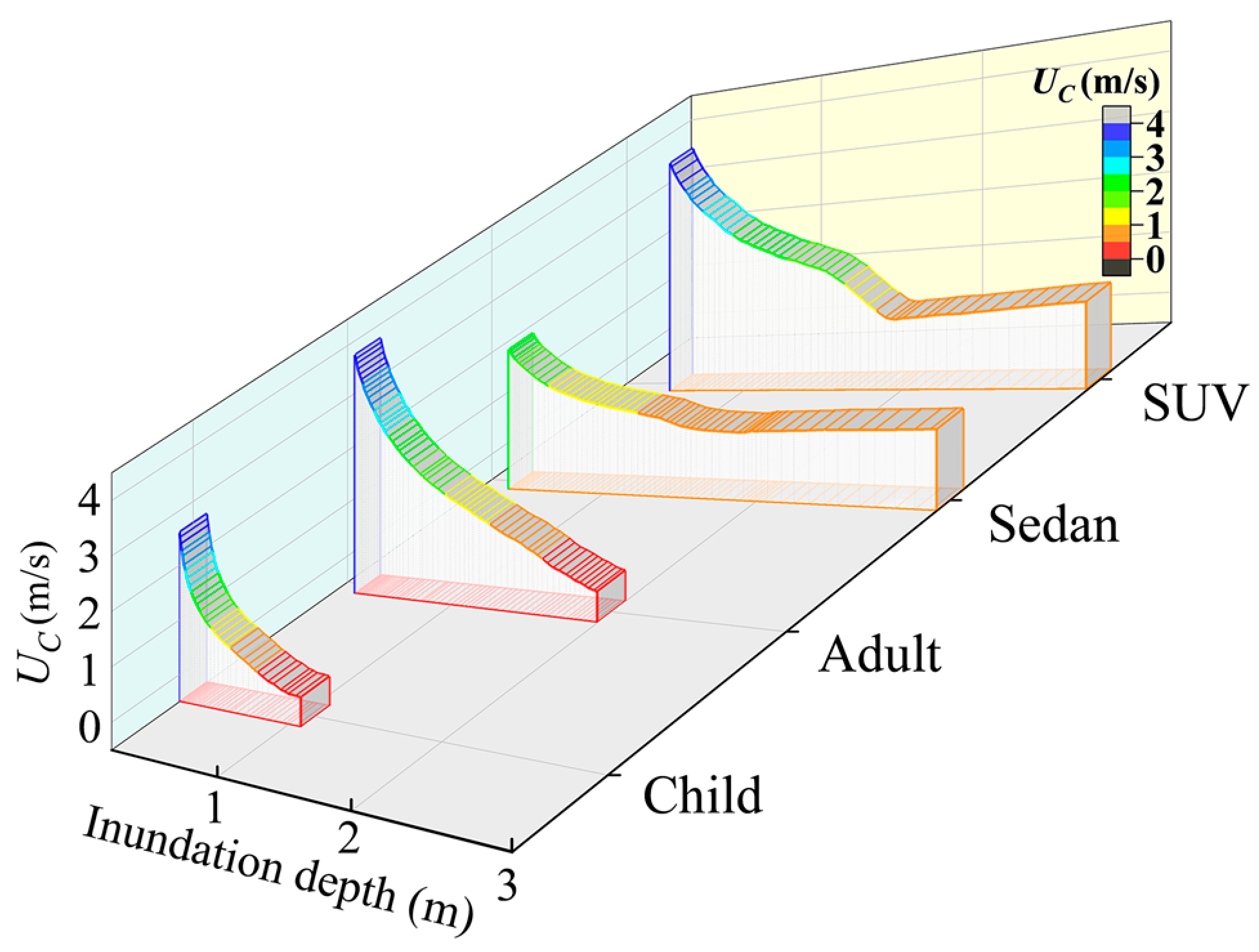

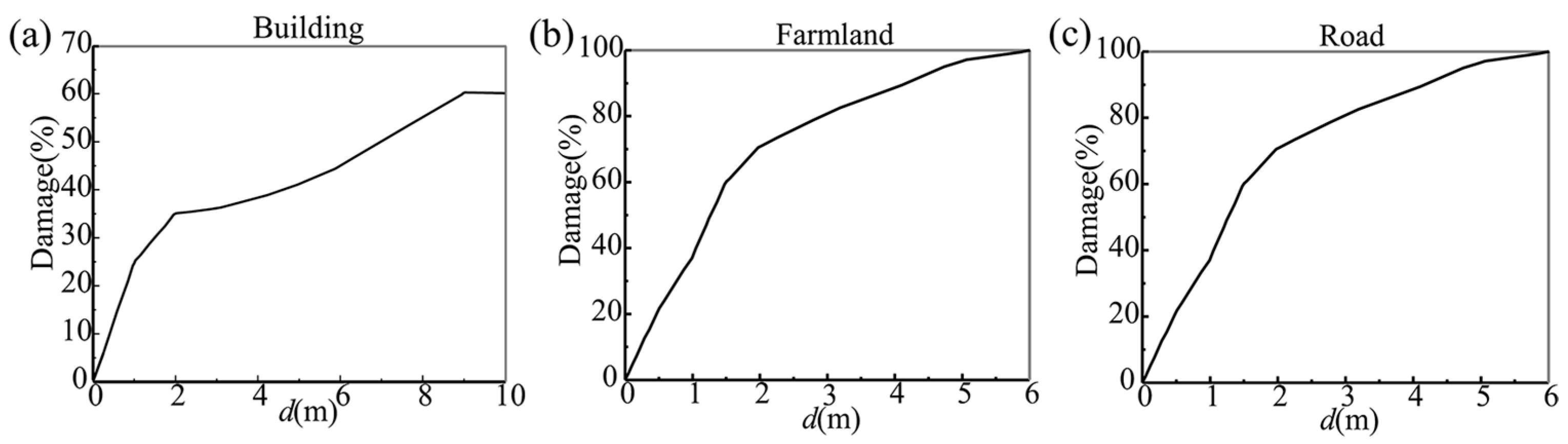

2.2.3. Flood Impact Assessment Model (FIM)

2.3. Experiment Design and Scenarios

2.4. Model Evaluation Metrics

3. Results

3.1. Hydrodynamic Performance and Validation

3.2. Object-Level Impact Assessment

3.2.1. Hazard-Exposure Assessment

3.2.2. Damage Assessment

3.3. Effectiveness of Mobile Pumping Stations

4. Discussion

4.1. Model Performance in Coastal Urban Areas

4.2. Sensitivity to Pumping Rates

4.3. Framework Advantages and Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hinkel, J.; Lincke, D.; Vafeidis, A.T.; Perrette, M.; Nicholls, R.J.; Tol, R.S.; Marzeion, B.; Fettweis, X.; Ionescu, C.; Levermann, A. Coastal flood damage and adaptation costs under 21st century sea-level rise. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2014, 111, 3292–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. In Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Core Writing Team, Lee, H., Romero, J., Eds.; IPCC: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallegatte, S.; Green, C.; Nicholls, R.J.; Corfee-Morlot, J. Future flood losses in major coastal cities. Nat. Clim. Change 2013, 3, 802–806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Luo, M.; Li, F.; Qi, X.; Huo, A.; Wang, Z.; He, B.; Takara, K.; Nover, D.; Wang, Y. Urban flood numerical simulation: Research, methods and future perspectives. Environ. Model. Softw. 2022, 156, 105478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teng, J.; Jakeman, A.J.; Vaze, J.; Croke, B.F.; Dutta, D.; Kim, S. Flood inundation modelling: A review of methods, recent advances and uncertainty analysis. Environ. Model. Softw. 2017, 90, 201–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cea, L.; Garrido, M.; Puertas, J. Experimental validation of two-dimensional depth-averaged models for forecasting rainfall–runoff from precipitation data in urban areas. J. Hydrol. 2010, 382, 88–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costabile, P.; Macchione, F.; Natale, L.; Petaccia, G. Flood mapping using LIDAR DEM. Limitations of the 1-D modeling highlighted by the 2-D approach. Nat. Hazards 2015, 77, 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Q.; Smith, L.S. A High-Performance Integrated hydrodynamic Modelling System for urban flood simulations. J. Hydroinform 2015, 17, 518–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, Y.; Liang, Q.; Zheng, J.; Wang, G.; Tong, X. Simulation of the full—Process dynamics of floating vehicles driven by flash floods. Water Resour. Res. 2024, 60, e2023WR036739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, J.; Yu, D.; Yin, Z.; Liu, M.; He, Q. Evaluating the impact and risk of pluvial flash flood on intra-urban road network: A case study in the city center of Shanghai, China. J. Hydrol. 2016, 537, 138–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angeloudis, A.; Falconer, R.A.; Bray, S.; Ahmadian, R. Representation and operation of tidal energy impoundments in a coastal hydrodynamic model. Renew. Energy 2016, 99, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, J.; Liang, Q.; Maharjan, S.B.; Joshi, S.P. Assessing the potential impact of glacial lake outburst floods on individual objects using a high-performance hydrodynamic model and open-source data. Sci. Total Environ. 2022, 806, 151289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, S.; Ramsbottom, D.; Floyd, P.; Penning-Rowsell, E.; Surendran, S. Risks to people: Developing New Approaches for Flood Hazard and Vulnerability Mapping. In Proceedings of the 40th Defra Flood and Coastal Management Conference, York, UK, 5–7 July 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, J.; Falconer, R.A.; Lin, B.; Tan, G. Numerical assessment of flood hazard risk to people and vehicles in flash floods. Environ. Model. Softw. 2011, 26, 987–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Xia, J.; Zhou, M.; Deng, S.; Li, Q. Assessment of the joint impact of rainfall and river water level on urban flooding in Wuhan City, China. J. Hydrol. 2022, 613, 128419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huizinga, J.; De Moel, H.; Szewczyk, W. Global Flood Depth-Damage Functions: Methodology and the Database with Guidelines; Joint Research Centre: Brussels, Belgium, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ming, X.; Liang, Q.; Xia, X.; Li, D.; Fowler, H.J. Rea-time flood forecasting based on a high-performance 2-D hydrodynamic model and numerical weather predictions. Water Resour. Res. 2020, 56, e2019WR025583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Liang, Q.; Wang, G.; Ming, X.; Xia, X. City-scale hydrodynamic modelling of urban flash floods: The issues of scale and resolution. Nat. Hazards 2019, 96, 473–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brakensiek, D.; Onstad, C. Parameter estimation of the Green and Ampt infiltration equation. Water Resour. Res. 1977, 13, 1009–1012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawls, W.J.; Brakensiek, D.L.; Miller, N. Green-Ampt infiltration parameters from soils data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 1983, 109, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB 50014-2021; Standard for Design of Outdoor Wastewater Engineering. Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development of the Pepole’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2021.

- Amouzgar, R.; Liang, Q.; Clarke, P.J.; Yasuda, T.; Mase, H. Computationally efficient tsunami modeling on graphics processing units (GPUs). Int. J. Offshore Polar Eng. 2016, 26, 154–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Liang, Q.; Xia, X.; Hou, J. Catchment-scale high-resolution flash flood simulation using the GPU-based technology. Procedia Eng. 2016, 154, 975–981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, R.; Mitsch, B. Stability of cars and children in flooded streets. In International Symposium on Urban Stormwater Management, Preprints of Papers; Institution of Engineers: Barton, Australia, 1992; pp. 264–268. [Google Scholar]

- Shand, T.; Cox, R.; Blacka, M.; Smith, G. Appropriate safety criteria for vehicles. In Australian Rainfall&Runoff Revision Projects Stage 2 Report; Engineers Australia: Barton, Australia, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- FEMA. Multi-Hazard Loss Estimation Methodology Earthquake Model: Earthquake Model, HAZUS-MH MR5 Technical Mannual; National Institute of Building Sciences (NlBS): Washington, DC, USA, 2009.

- Arcement, G.J.; Schneider, V.R. Guide for Selecting Manning’s Roughness Coefficients for Natural Channels and Flood Plains; US Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1989.

- FEMA. Guidelines and Specifications for Flood Hazard Mapping Partners; FEMA: Washington, DC, USA, 2003.

- Yuan, J.; Zheng, F.; Duan, H.-F.; Deng, Z.; Kapelan, Z.; Savic, D.; Shao, T.; Huang, W.-M.; Zhao, T.; Chen, X. Numerical modelling and quantification of coastal urban compound flooding. J. Hydrol. 2024, 630, 130716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreimer, A.; Arnold, M.; Carlin, A. Building Safer Cities: The Future of Disaster Risk; World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi, J.; Choi, H.; Kim, J. A methodology for optimal operation of pumping stations in urban drainage systems. J. Hydro-Environ. Res. 2016, 11, 101–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Hou, J.; Chai, J.; Du, Y.e.; Han, H.; Fan, C.; Qiao, M. Multisurrogate assisted evolutionary algorithm–based optimal operation of drainage facilities in urban storm drainage systems for flood mitigation. J. Hydrol. Eng. 2022, 27, 04022025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.-Y.; Shuai, Z.-J.; Yu, T.; Jian, J.; Guo, Y.-B.; Li, W.-Y. A multi-field coupling simulation model for the centrifugal pump system. Mech. Ind. 2023, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Specklin, M. On the Assessment of Immersed Boundary Methods for Fluid-Structure Interaction Modelling: Application to Waste Water Pumps Design and the Inherent Clogging Issues. Ph.D. Thesis, Dublin City University, London, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

| Gauge | η (m) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Filed Survey Data | Simulated Results | Relative Error | |

| 1# | 3.9 | 4.01 | 2.8% |

| 2# | 3.3 | 3.29 | 0.3% |

| 3# | 3.8 | 3.68 | 3.2% |

| Objects | Buildings | Roads | Agriculture Lands | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Evaluation Metrics | ||||

| RMSE (m) | 0.184 | 0.189 | 0.181 | |

| F-statistic (%) | 72.15 | 71.02 | 73.68 | |

| Gauge | Location | x (m) | y (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| G1 | Chenyu Middle School | 614,101.39 | 3,110,126.27 |

| G2 | Chenyu Kindergarten | 614,292.51 | 3,110,159.02 |

| G3 | Chenyu Primary School | 614,393.06 | 3,110,077.03 |

| G4 | Modern Educational School | 614,585.93 | 3,110,047.04 |

| G5 | Damaiyu Development Individual Tax Office | 614,319.29 | 3,109,739.01 |

| G6 | Damaiyu Development Urban Supervision Brigade | 614,055.52 | 3,109,948.37 |

| G7 | Yuhuan Lvbo New Energy Co., Ltd. | 614,184.76 | 3,109,703.61 |

| G8 | Chenyu Power Supply Bureau | 614,088.19 | 3,109,997.50 |

| G9 | Chenyu Power Supply Business Office | 614,170.39 | 3,110,020.58 |

| Object | P (m/s) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 0.01 | 0.1 | 1 | ||

| Population counts | 1952 | 856 | 253 | 36 | |

| Agricultural (km2) | 5.95 | 4.36 | 3.29 | 1.78 | |

| Road (km) | 39.01 | 26.22 | 7.57 | 5.91 | |

| Building | 587 | 393 | 79 | 16 | |

| Public facility | School | 8 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Police | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Park | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | |

| Community | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cultural Center | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Health facility | Hospital | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Pharmacy | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 | |

| Traffic facility | Bus station | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Gas station | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| Commercial facility | Convenience store | 15 | 13 | 5 | 2 |

| Bank | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | |

| Restaurant | 19 | 15 | 6 | 2 | |

| Hotel | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xiong, Y.; Jiang, J.; Cui, Y.; Ming, X.; Ji, X.; Zhang, H.; Jing, M. Assessment of Object-Level Flood Impact Considering Pump Station Operations in Coastal Urban Areas. Water 2025, 17, 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223195

Xiong Y, Jiang J, Cui Y, Ming X, Ji X, Zhang H, Jing M. Assessment of Object-Level Flood Impact Considering Pump Station Operations in Coastal Urban Areas. Water. 2025; 17(22):3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223195

Chicago/Turabian StyleXiong, Yan, Jinghua Jiang, Yunsong Cui, Xiaodong Ming, Xiaolei Ji, Hairong Zhang, and Mingzhou Jing. 2025. "Assessment of Object-Level Flood Impact Considering Pump Station Operations in Coastal Urban Areas" Water 17, no. 22: 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223195

APA StyleXiong, Y., Jiang, J., Cui, Y., Ming, X., Ji, X., Zhang, H., & Jing, M. (2025). Assessment of Object-Level Flood Impact Considering Pump Station Operations in Coastal Urban Areas. Water, 17(22), 3195. https://doi.org/10.3390/w17223195