Seasonal Evaluation and Effects of Poultry Litter-Based Organic Fertilization on Sustainable Production and Secondary Metabolism of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Chemical Characterization of the Soil

2.3. Spore Density and Colonization by Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (AMF)

2.4. Determination of Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon, Basal Respiration, and Metabolic Quotient

2.5. Determination of Plants’ Fresh and Dry Biomass

2.6. Determination of Phosphorus and Nitrogen Content in Plants

2.7. Preparation and Yield of Extracts

2.8. Identification of Constituents in the Aerial Parts of C. carthagenensis

2.9. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Chemical Characterization of the Soil

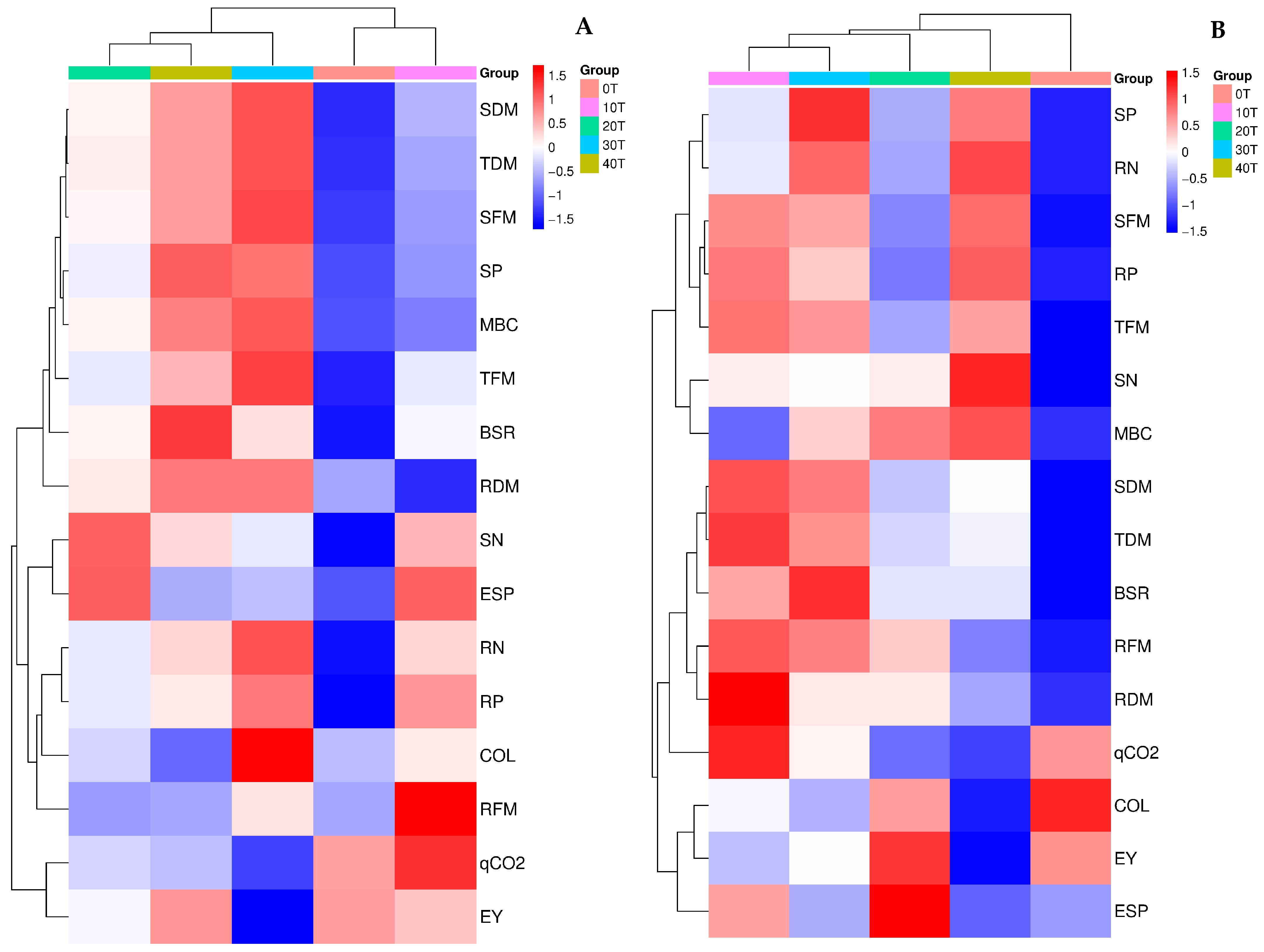

3.2. Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi and Soil Health (Quality)

3.3. Plants’ Biomass, Phosphorus, and Nitrogen Content

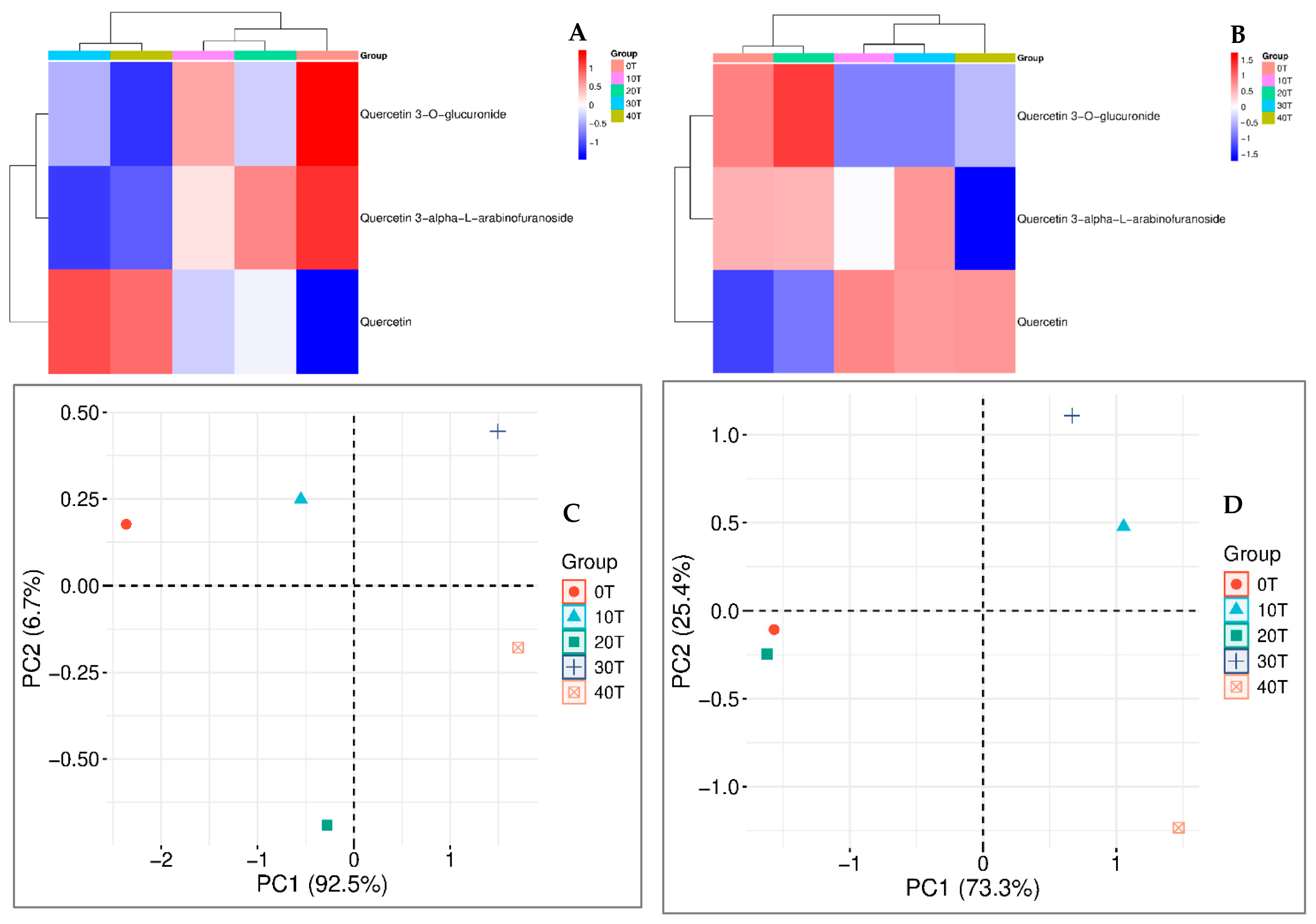

3.4. Yield of Extracts and Identification of Constituents in the Aerial Parts of C. carthagenensis

| Compound | MS | RT (min) | Summer–Poultry Litter Doses (t ha−1) | Autumn/Winter–Poultry Litter Doses (t ha−1) | Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | ||||

| Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | 479.082 | 5.56 | 37.49 * | 34.59 | 32.11 | 31.52 | 29.28 | 35.50 | 31.45 | 36.59 | 31.40 | 32.36 | [73] |

| Quercetin | 303.050 | 7.26 | 27.92 | 32.39 | 33.22 | 37.28 | 36.62 | 31.64 | 40.96 | 33.13 | 40.29 | 40.50 | [74] |

| Quercetin 3-α-L-arabinofuranoside | 435.092 | 5.69 | 9.11 | 8.45 | 8.80 | 7.64 | 7.74 | 8.14 | 7.98 | 8.13 | 8.20 | 7.46 | [75] |

| Quercetin 3-O-glucoside | 465.103 | 5.40 | 5.50 | 4.71 | 5.33 | 5.01 | 4.81 | 4.80 | 4.75 | 4.27 | 4.80 | 4.26 | [76] |

| Kaempferol 3-O-beta-sophoroside | 611.161 | 5.12 | 4.59 | 4.38 | 4.61 | 4.24 | 4.40 | 3.30 | 2.61 | 2.57 | 2.61 | 2.84 | [77] |

| Quercetin 3-O-galactoside | 465.103 | 5.06 | 4.50 | 3.51 | 4.22 | 3.30 | 3.82 | 3.02 | 2.92 | 3.27 | 2.86 | 2.48 | [78] |

| Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | 595.166 | 5.53 | 4.44 | 5.14 | 4.90 | 4.93 | 5.13 | 3.73 | 4.27 | 4.37 | 4.42 | 4.76 | [79] |

| Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | 449.108 | 5.76 | 2.07 | 2.04 | 2.11 | 2.26 | 2.20 | 2.29 | 2.35 | 2.19 | 2.68 | 2.71 | [79] |

| Vicenin 2 | 595.166 | 4.41 | 1.73 | 2.35 | 1.66 | 1.72 | 2.15 | 1.40 | 1.02 | 1.01 | 0.96 | 0.97 | [80] |

| Kaempferol 3-glucuronide | 463.087 | 5.90 | 1.16 | 0.94 | 1.02 | 0.97 | 0.94 | 1.07 | 1.04 | 1.16 | 1.11 | 1.13 | [81] |

| Myricetin 3-galactoside | 481.098 | 4.98 | 1.01 | 0.95 | 1.01 | 0.67 | 0.92 | 0.50 | - | 0.54 | - | - | [82] |

| 2′-O-galloylhyperin | 617.114 | 5.20 | 0.50 | 0.54 | 0.62 | 0.45 | 0.56 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.64 | 0.68 | 0.52 | [83] |

| Catechin | 291.086 | 4.16 | - | - | - | - | 1.04 | 1.34 | - | 1.31 | - | - | [84] |

| Epigallocatechin | 307.081 | 3.33 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.83 | - | 0.83 | - | - | [85] |

| Apigenin 7-glucuronide | 447.092 | 5.99 | - | - | - | - | - | 1.03 | - | - | - | - | [86] |

| Leucoside | 581.150 | 5.46 | - | - | 0.40 | - | 0.40 | - | - | - | - | - | [87] |

| Rosmarinic acid | 361.092 | 6.11 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | [88] |

| Glycosylated flavonoids: | 72.08 | 67.61 | 66.78 | 62.72 | 62.34 | 65.37 | 59.04 | 64.74 | 59.71 | 59.50 | |||

| Free flavonoids: | 27.92 | 32.39 | 33.22 | 37.28 | 37.66 | 33.81 | 40.96 | 35.26 | 40.29 | 40.50 | |||

| Phenolic acids: | - | - | - | - | - | 0.82 | - | - | - | - | |||

| Compound | MS | RT (min) | Summer–Poultry Litter Doses (t ha−1) | Autumn/Winter–Poultry Litter Doses (t ha−1) | Reference | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 0 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | ||||

| Quercetin 3-O-glucuronide | 477.066 | 5.60 | 28.01 * | 25.65 | 23.23 | 25.06 | 21.81 | 21.47 | 24.25 | 24.40 | 23.51 | 22.68 | [89] |

| Quercetin | 301.034 | 7.26 | 11.54 | 14.05 | 15.50 | 18.57 | 16.94 | 12.31 | 19.25 | 14.62 | 19.26 | 17.77 | [90] |

| Quercetin 3-α-L-arabinofuranoside | 433.077 | 5.71 | 10.79 | 10.71 | 10.18 | 9.16 | 9.30 | 8.57 | 10.36 | 10.25 | 11.01 | 9.31 | [89] |

| Gallic acid | 169.013 | 2.48 | 9.82 | 11.19 | 13.52 | 9.95 | 14.91 | 7.31 | 9.07 | 9.62 | 8.79 | 9.92 | [91] |

| Turanose | 341.108 | 1.00 | 9.43 | 9.67 | 7.34 | 9.03 | 6.51 | 7.38 | 9.14 | 9.22 | 7.92 | 7.77 | [92] |

| D-Mannitol | 227.076 | 1.01 | 6.23 | 7.93 | 4.99 | 6.93 | 6.33 | 5.08 | 7.55 | 8.94 | 7.48 | 8.35 | [91] |

| Quercetin 3-O-glucoside | 463.087 | 5.42 | 4.63 | 4.38 | 4.80 | 4.14 | 4.30 | 3.60 | 4.37 | 3.79 | 4.56 | 3.66 | [93] |

| Kaempferol 3-O-rutinoside | 593.150 | 5.51 | 3.85 | 4.54 | 4.37 | 4.54 | 4.73 | 2.73 | 3.94 | 3.98 | 4.41 | 4.52 | [94] |

| Quercetin 3-O-galactoside | 463.087 | 5.05 | 3.44 | 2.92 | 3.55 | 2.88 | 3.14 | 2.23 | 2.66 | 2.59 | 2.61 | 2.09 | [89] |

| Kaempferol 3-O-glucoside | 447.092 | 5.78 | 2.12 | 2.26 | 2.40 | 2.32 | 2.44 | 1.99 | 2.79 | 2.56 | 3.22 | 3.03 | [95] |

| Matairesinoside | 519.186 | 5.98 | 1.38 | - | 1.22 | 1.09 | 1.01 | 1.44 | 1.79 | 1.91 | 2.28 | 1.88 | [96] |

| Kaempferol 3-O-beta-sophoroside | 609.145 | 5.14 | 1.30 | 1.04 | 1.21 | 0.92 | 1.12 | 0.30 | 0.33 | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.39 | [77] |

| Kaempferol 3-glucuronide | 461.071 | 5.90 | 1.11 | 1.03 | 0.99 | 1.03 | 0.93 | 1.00 | 1.11 | 1.19 | 1.28 | 1.11 | [81] |

| Chebuloside II | 711.395 | 6.21 | 1.10 | 0.83 | 1.30 | 0.84 | 1.26 | 0.37 | 0.39 | - | 0.41 | 0.34 | [97] |

| Rosmarinic acid | 359.076 | 6.11 | 1.04 | - | - | - | - | 9.99 | 0.38 | 1.50 | - | 2.83 | [98] |

| Vicenin 2 | 593.150 | 4.39 | 0.95 | 1.62 | 0.65 | 1.29 | 0.77 | 0.91 | 0.83 | 1.05 | 0.76 | 0.82 | [99] |

| Myricetin 3-galactoside | 479.082 | 4.97 | 0.77 | 0.72 | 0.96 | 0.56 | 0.82 | 0.37 | - | 0.42 | - | 0.32 | [82] |

| Myricetin-3-O-xyloside | 449.071 | 5.27 | 0.73 | - | 0.87 | 0.49 | 0.81 | 0.43 | - | - | - | - | [100] |

| Chicoric acid | 473.071 | 6.59 | 0.64 | - | - | - | - | 6.59 | - | 0.53 | - | 0.92 | [101] |

| 1-O-Feruloylglucose | 355.102 | 4.09 | 0.63 | 0.27 | 0.60 | 0.74 | 0.43 | 0.43 | 0.53 | 0.61 | 0.84 | 0.77 | [102] |

| 2′-O-galloylhyperin | 615.098 | 5.22 | 0.52 | 0.55 | 0.65 | 0.48 | 0.60 | 0.56 | 0.66 | 0.66 | 0.71 | 0.56 | [103] |

| 3-methoxybenzoic acid | 465.103 | 6.04 | - | - | 0.46 | - | 0.40 | - | - | - | - | - | [104] |

| Apigenin 7-glucuronide | 445.077 | 6.03 | - | - | - | - | - | 0.37 | - | - | - | - | [105] |

| Catechin | 289.071 | 4.19 | - | 0.67 | 0.54 | - | 0.66 | 0.70 | - | 0.82 | - | - | [90] |

| Epigallocatechin | 305.066 | 3.35 | - | - | - | - | 0.34 | 0.75 | - | 0.96 | - | - | [90] |

| 1.6-Digalloyl-beta-D-glucopyranose | 483.077 | 3.89 | - | - | 0.41 | - | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.58 | - | 0.59 | - | [106] |

| Abscisic acid | 263.128 | 6.85 | - | - | 0.26 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | [107] |

| Carnosol | 329.175 | 10.74 | - | - | - | - | - | 2.64 | - | - | - | 0.97 | [108] |

| Glycosylated flavonoids: | 58.20 | 55.41 | 53.87 | 52.86 | 50.77 | 44.51 | 51.32 | 51.27 | 52.45 | 48.48 | |||

| Free flavonoids: | 11.54 | 14.71 | 16.04 | 18.57 | 17.94 | 13.76 | 19.25 | 16.40 | 19.26 | 17.77 | |||

| Carboxylic acids: | 9.82 | 11.19 | 13.51 | 9.95 | 14.91 | 7.31 | 9.07 | 9.62 | 8.78 | 9.92 | |||

| Glycosides: | 9.43 | 9.67 | 7.34 | 9.03 | 6.51 | 7.38 | 9.14 | 9.22 | 7.92 | 7.77 | |||

| Lignans: | 6.23 | 7.93 | 4.99 | 6.92 | 6.33 | 5.08 | 7.55 | 8.94 | 7.48 | 8.35 | |||

| Saccharides: | 2.01 | 0.27 | 1.81 | 1.83 | 1.44 | 1.86 | 2.32 | 2.52 | 3.11 | 2.65 | |||

| Terpenoids: | 1.10 | 0.83 | 1.56 | 0.84 | 1.26 | 3.01 | 0.39 | - | 0.40 | 1.30 | |||

| Cinnamic acids: | 1.04 | - | - | - | - | 9.99 | 0.38 | 1.50 | - | 2.83 | |||

| Phenolic acids: | 0.64 | - | 0.46 | - | 0.40 | 6.59 | - | 0.53 | - | 0.92 | |||

| Tannins: | - | 0.46 | 0.51 | 0.58 | - | 0.59 | - | - | 0.46 | 0.51 | |||

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Graham, S.A.; José, G.P.C.; Murad, A.M.; Rech, E.L.; Cavalcanti, T.B.; Inglis, P.W. Patterns of Fatty Acid Composition in Seed Oils of Cuphea, with New Records from Brazil and Mexico. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 87, 379–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Gesch, R.W. Macro and Microminerals of Four Cuphea Genotypes Grown Across the Upper Midwest USA. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 66, 38–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olness, A.; Gesch, R.; Forcella, F.; Archer, D.; Rinke, J. Importance of Vanadium and Nutrient Ionic Ratios on the Development of Hydroponically Grown cuphea. Ind. Crops Prod. 2005, 21, 165–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gesch, R.; Forcella, F.; Olness, A.; Archer, D.; Hebard, A. Agricultural Management of Cuphea and Potential for Commercial Production in the Northern Corn Belt. Ind. Crops Prod. 2006, 24, 300–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berti, M.T.; Johnson, B.L. Growth and Development of Cuphea. Ind. Crops Prod. 2008, 27, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corsino, A.L.; Alves-da-Silva, D.; Palhares-Melo, L.A.M.; Cavalcanti, T.B. Germination and Vegetative Propagation of the Wild Species Cuphea pulchra Moric. (Lythraceae), A Potential Ornamental. Crop. Int. J. Plant Biol. 2024, 15, 32–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Chaudary, S.K.; Bhat, H.R.; Shakya, A. Cuphea carthagenensis: A Review of Its Ethnobotany, Pharmacology and Phytochemistry. Bull. Arunachal For. Res. 2018, 33, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Schuldt, E.Z.; Ckless, K.; Simas, M.E.; Farias, M.R.; Ribeiro-Do-Valle, R.M. Butanolic Fraction from Cuphea carthagenensis Jacq McBride Relaxes Rat Thoracic Aorta Through Endothelium-Dependent and Endothelium-Independent Mechanisms. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2000, 35, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krepsky, P.B.; Isidório, R.G.; Souza, J.D.F.; Côrtes, S.F.; Braga, F.C. Chemical Composition and Vasodilatation Induced by Cuphea carthagenensis Preparations. Phytomedicine 2012, 19, 953–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braga, F.C.; Wagner, H.; Lombardi, J.A.; Oliveira, A.B. Screening the Brazilian Flora for Antihypertensive Plant Species For In Vitro Angiotensin-I-Converting Enzyme Inhibiting Activity. Phytomedicine 2000, 7, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Toson, N.S.; Pimentel, M.C.; Bordignon, S.A.; Mendez, A.S.; Henriques, A.T. Polyphenols Composition from Leaves of Cuphea Spp. and Inhibitor Potential, In Vitro, of Angiotensin I-Converting Enzyme (ACE). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 255, 112781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isla, K.K.Y.; Tanae, M.M.; de Lima-Landman, M.T.R.; de Magalhães, P.M.; Lapa, A.J.; Souccar, C. Vasorelaxant Effects of Ellagitannins Isolated from Cuphea carthagenensis. Planta Med. 2024, 90, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jacobucci, N.A.D.O.; Pinc, M.M.; Dalmagro, M.; Ribeiro, J.K.O.; Assunção, T.A.D.; Klein, E.J.; da Silva, E.A.; Macruz, P.D.; Jacomassi, E.; Alberton, O.; et al. Extractive Optimization of Bioactive Compounds in Aerial Parts of Cuphea carthagenensis Using Box-Behnken Experimental Design. Nat. Prod. Res. 2025, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avancini, C.; Wiest, J.M.; Dall’Agnol, R.; Haas, J.S.; Poser, G.L. Antimicrobial Activity of Plants Used in the Prevention and Control of Bovine Mastitis in Southern Brazil. Lat. Am. J. Pharm. 2008, 27, 894–899. [Google Scholar]

- Wiest, J.M.; Carvalho, H.H.; Avancini, C.A.M.; Gonçalves, A.R. Anti-staphylococci Activity in Extracts from Plants Presenting Medicinal and Spice Indicative. Rev. Bras. Plantas Med. 2009, 11, 209–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrighetti-Fröhner, C.; Sincero, T.C.M.; Silva, A.C.; Savi, L.A.; Gaido, C.M.; Bettega, J.M.R.; Simoes, C.M.O. Antiviral Evaluation of Plants from Brazilian Atlantic Tropical Forest. Fitoterapia 2005, 76, 374–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuldt, E.Z.; Farias, M.R.; Ribeiro-do-Valle, R.M.; Ckless, K. Comparative Study of Radical Scavenger Activities of Crude Extract and Fractions from Cuphea carthagenensis Leaves. Phytomedicine 2004, 11, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krepsky, P.B.; Farias, M.R.; Côrtes, S.F.; Braga, F.C. Quercetin-3-sulfate: A Chemical Marker for Cuphea carthagenensis. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2010, 38, 125–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergmeier, D.; Berres, P.H.D.; Filippi, D.; Bilibio, D.; Bettiol, V.R.; Priamo, W.L. Extraction of Total Polyphenols from Hibiscus (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) and Waxweed/‘sete-sangrias’ (Cuphea carthagenensis) and Evaluation of their Antioxidant Potential. Acta Sci. Technol. 2014, 36, 545–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prando, T.B.L.; Barboza, L.N.; Gasparotto, F.M.; Araújo, V.O.; Tirloni, C.A.S.; Souza, L.M.; Júnior, A.G. Ethnopharmacological Investigation of the Diuretic and Hemodynamic Properties of Native Species of the Brazilian Biodiversity. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 174, 369–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rather, M.A.; Deori, P.J.; Gupta, K.; Daimary, N.; Deka, D.; Qureshi, A.; Dutta, T.K.; Joardar, S.N.; Mandal, M. Ecofriendly Phytofabrication of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aqueous Extract of Cuphea carthagenensis and Their Antioxidant Potential and Antibacterial Activity Against Clinically Important Human Pathogens. Chemosphere 2022, 300, 134497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.C.; Soares, K.D.; Beltrame, B.M.; Bordignon, S.A.L.; Apel, M.A.; Mendez, A.S.L. Cuphea spp.: Antichemotactic Study for a Potential Anti-Inflammatory Drug. Nat. Prod. Res. 2020, 35, 6058–6061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barboza, L.N.; Lívero, F.A.R.; Prando, T.B.L.; Ribeiro, R.D.C.L.; Lourenço, E.L.B.; Budel, J.M.; Júnior, A.G. Atheroprotective Effects of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) JF Macbr. in New Zealand Rabbits Fed with Cholesterol-Rich Diet. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 187, 134–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biavatti, M.W.; Farias, C.; Curtius, F.; Brasil, L.M.; Hort, S.; Schuster, L.; Prado, S.R.T. Preliminary Studies on Campomanesia xanthocarpa (Berg.) and Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) JF Macbr. Aqueous Extract: Weight Control and Biochemical Parameters. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 93, 385–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaedler, M.I.; Palozi, R.A.C.; Tirloni, C.A.S.; Silva, A.O.; Araújo, V.O.; Lourenço, E.L.B.; Júnior, A.G. Redox Regulation and NO/cGMP Plus K+ channel Activation Contributes to Cardiorenal Protection Induced by Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) JF Macbr. in ovariectomized hypertensive rats. Phytomedicine 2018, 51, 7–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otênio, J.K.; Baisch, R.G.; Carneiro, V.P.P.; Lourenço, E.L.B.; Alberton, O.; Soares, A.A.; Jacomassi, E. Ethnopharmacology of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) JF Macbr: A Review. Braz. J. Dev. 2020, 6, 10206–10219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Lan, X.; Hou, H.; Ji, J.; Liu, X.; Lv, Z. Multifaceted Ability of Organic Fertilizers to Improve Crop Productivity and Abiotic Stress Tolerance: Review and Perspectives. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, V.; Bertolucci, S.K.V.; Carvalho, A.A.D.; Roza, H.L.H.; Figueiredo, F.C.; Pinto, J.E.B.P. Improvement of Cymbopogon flexuosus Biomass and Essential Oil Production with Organic Manures. J. Agric. Sci. 2019, 11, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, P.; Gao, Y.; Cui, Z.; Wu, B.; Yan, B.; Wang, Y.; Wen, M.; Wang, H.; Ma, X.; Wen, Z. Application of Organic Fertilizers Optimizes Water Consumption Characteristics and Improves Seed Yield of Oilseed Flax in Semi-Arid Areas of the Loess Plateau. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laftouhi, A.; Eloutassi, N.; Ech-Chihbi, E.; Rais, Z.; Abdellaoui, A.; Taleb, A.; Beniken, M.; Nafidi, H.-A.; Salamatullah, A.M.; Bourhia, M.; et al. The Impact of Environmental Stress on the Secondary Metabolites and the Chemical Compositions of the Essential Oils from Some Medicinal Plants Used as Food Supplements. Sustainability 2023, 15, 7842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture—USDA. Poultry and Products Annual—Brasilia/Brazil (BR2024-0028). October 2024. Available online: https://apps.fas.usda.gov/newgainapi/api/Report/DownloadReportByFileName?fileName=Poultry+and+Products+Annual_Brasilia_Brazil_BR2024-0028 (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Murtaza, G.; Ahmed, Z.; Usman, M.; Tariq, W.; Ullah, Z.; Shareef, M.; Iqbal, H.; Waqas, M.; Tariq, A.; Wu, Y.; et al. Biochar Induced Modifications in Soil Properties and Its Impacts on Crop Growth and Production. J. Plant Nutr. 2021, 44, 1677–1691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katuwal, S.; Rafsan, N.-A.-S.; Ashworth, A.J.; Kolar, P. Poultry Litter Physiochemical Characterization Based on Production Conditions for Circular Systems. BioResources 2023, 18, 3961–3977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Hamilton, D.W.; Payne, J. Using Poultry Litter as Fertilizer: Waste Nutrient Management Specialist. Oklahoma State University Extension. 2017. Available online: https://extension.okstate.edu/fact-sheets/using-poultry-litter-as-fertilizer.html (accessed on 10 October 2025).

- Thompson, D.K.; Thepsilvisut, O.; Imorachorn, P.; Boonkaen, S.; Chutimanukul, P.; Somyong, S.; Mhuantong, W.; Ehara, H. Nutrient Management Under Good Agricultural Practices for Sustainable Cassava Production in Northeastern Thailand. Resources 2025, 14, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerdemann, J.W.; Nicolson, T.H. Spores of Mycorrhizal Endogone Species Extracted from Soil by Wet Sieving and Decanting. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1963, 46, 235–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.M.; Hayman, D.S. Improved Procedures for Clearing Roots and Staining Parasitic and Vesicular-Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi for Rapid Assessment of Infection. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1970, 55, 158–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vance, E.D.; Brookes, P.C.; Jenkinson, D.S. An Extraction Method for Measuring Soil Microbial Biomass C. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1987, 19, 703–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tate, K.R.; Ross, D.J.; Feltham, C.W. A Direct Extraction Method to Estimate Soil Microbial C: Effects of Experimental Variables and Some Different Calibration Procedures. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1988, 20, 329–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lermen, C.; Cruz, R.M.S.; Gonçalves, C.H.S.; Cruz, G.L.S.; Silva, G.P.A.; Alberton, O. Growth of Lemongrass (Cymbopogon citratus (DC) Stapf) Inoculated with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi (Rhizophagus clarus and Claroideoglomus etunicatum) under contrasting phosphorus levels. Aust. J. Crop Sci. 2019, 13, 266–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenkinson, D.S.; Powlson, D.S. The Effects of Biocidal Treatments on Metabolism in Soil-V: A Method for Measuring Soil Biomass. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1976, 8, 209–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.E.; Azevedo, P.H.S.; De-Polli, H. Determination of Basal Respiration and Metabolic Quotient of Soil; Technical Communication 99; Embrapa Agrobiologia: Seropédica, Brazil, 2007; p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, T.; Domsch, K.H. The Metabolic Quotient for CO2 (qCO2) as a Specific Activity Parameter to Assess the Effects of Environmental Conditions, Such as pH, on the Microbial Biomass of Forest Soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 1993, 25, 393–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, E.E.; Azevedo, P.H.S.; De-Polli, H. Determination of Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon (SMB-C); Technical Communication 98; Embrapa Agrobiologia: Seropédica, Brazil, 2007; p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Silva, C.F. Manual of Chemical Analyses of Soils, Plants, and Fertilizers, 2nd ed.; Embrapa: Brasília, Brazil, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Tolouei, S.E.L.; Tirloni, C.A.S.; Palozi, R.A.C.; Schaedler, M.I.; Guarnier, L.P.; Silva, A.O.; de Almeida, V.P.; Budel, J.M.; Souza, R.I.C.; Dos Santos, A.C.; et al. Celosia argentea L. (Amaranthaceae), a Vasodilator Species from the Brazilian Cerrado–An Ethnopharmacological Report. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2019, 229, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, D.; Chen, M.; Huang, X.; Zhang, G.; Zeng, L.; Zhang, G.; Wu, S.; Wang, Y. SRplot: A Free Online Platform for Data Visualization and Graphing. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0294236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambatti, J.A.; Souza Junior, I.G.; Costa, A.C.S.; Tormena, C.A. Estimation of Potential Acidity by the pH SMP Method in Soils of the Caiuá Formation: Northwest of the State of Paraná. Rev. Bras. Ciênc. Solo 2003, 27, 257–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masocha, B.L.; Dikinya, O. The Role of Poultry Litter and Its Biochar on Soil Fertility and Jatropha curcas L. Growth Sandy-Loam. Soil. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 12294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duruigbo, C.I.; Obiefuna, J.C.; Onweremadu, E.U. Effect of Poultry Manure Rates on Soil Acidity in an Ultisol. Int. J. Soil Sci. 2007, 2, 154–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, D.; Prasad, R.; Feng, H.; Watts, D.B.; Torbert, H.A. Distribution of Phosphorus Forms in Soil Amended with Poultry Litter of Different Ages and Application Rates: Agronomic and Environmental Perspectives. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2025, 89, e20781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamennaya, N.A.; Geraki, K.; Scanlan, D.J.; Zubkov, M.V. Accumulation of Ambient Phosphate into the Periplasm of Marine Bacteria Is Proton Motive Force Dependent. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, J.; Xie, S.; Zhang, T. Influences of Hydrothermal Carbonization on Phosphorus Availability of Swine Manure-Derived Hydrochar: Insights into Reaction Time and Temperature. Mater. Sci. Energy Technol. 2022, 5, 416–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.D.; Morgan, K.; Hogue, B.; Li, Y.C.; Sui, D. Improving Phosphorus Use Efficiency for Snap Bean Production by Optimizing Application Rate. Hortic. Sci. 2015, 42, 94–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharya, A. Changing Environmental Condition and Phosphorus-Use Efficiency in Plants. In Changing Climate and Resource Use Efficiency in Plants; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2018; pp. 241–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira Junior, W.G.; Moura, J.B.D.; Souza, R.F.D.; Braga, A.P.M.; Matos, D.J.D.C.; Brito, G.H.M.; Santos, J.M.D.; Moreira, R.M.; Dutra e Silva, S. Seasonal Variation in Mycorrhizal Community of Different Cerrado Phytophysiomies. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 576764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, S.E.; Read, D.J. Mycorrhizal Symbiosis; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 2008; 603p. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, N.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Deng, L.; Deng, L.; Chachar, M.; Chachar, Z.; Chachar, S.; Hayat, F.; Raza, A.; et al. Symbiotic Synergy: How Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Enhance Nutrient Uptake, Stress Tolerance, and Soil Health Through Molecular Mechanisms and Hormonal Regulation. IMA Fungus 2025, 21, e144989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutjahr, C.; Parniske, M. Cell and Developmental Biology of Arbuscular Mycorrhiza Symbiosis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 2013, 29, 593–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaschuk, G.; Alberton, O.; Hungria, M. Three Decades of Soil Microbial Biomass Studies in Brazilian Ecosystems: Lessons Learned About Soil Quality and Indications for Improving Sustainability. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2010, 42, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Francaviglia, R.; Almagro, M.; Vicente-Vicente, J.L. Conservation Agriculture and Soil Organic Carbon: Principles, Processes, Practices and Policy Options. Soil Syst. 2023, 7, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomar, U.; Baishya, R. Seasonality and Moisture Regime Control Soil Respiration, Enzyme Activities, and Soil Microbial Biomass Carbon in a Semi-Arid Forest of Delhi, India. Ecol. Process. 2020, 9, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnecker, J.; Baldaszti, L.; Gündler, P.; Pleitner, M.; Richter, A.; Sandén, T.; Simon, E.; Spiegel, F.; Spiegel, H.; Urbina Malo, C.; et al. Seasonal Dynamics of Soil Microbial Growth, Respiration, Biomass, and Carbon Use Efficiency in Temperate Soils. Geoderma 2023, 440, 116693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, A.A.; Puissant, J.; Buckeridge, K.M. Land Use-Driven Change in Soil pH Affects Microbial Carbon Cycling Processes. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agbede, T.M. Poultry Manure Improves Soil Properties and Grain Mineral Composition, Maize Productivity and Economic Profitability. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 16501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, S.; Liu, W.; Shi, S.; Cao, W. Nitrogen Fertilizer Regulates Soil Respiration by Altering the Organic Carbon Storage in Root and Topsoil in Alpine Meadow of the North-Eastern Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 13735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Chen, C.; Wang, G. Inoculation with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Improves Plant Biomass and Nitrogen and Phosphorus Nutrients: A Meta-Analysis. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Watts, D.B.; Runion, G.B. Influence of Poultry Litter on Nutrient Availability and Fate in Plant-Soil Systems: A Meta-Analysis. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2022, 77, 230–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Geng, Q.; Zhang, H.; Bian, C.; Chen, H.Y.; Jiang, D.; Xu, X. Global Negative Effects of Nutrient Enrichment on Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi, Plant Diversity and Ecosystem Multifunctionality. New Phytol. 2021, 229, 2957–2969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urcoviche, R.C.; Gazim, Z.C.; Dragunski, D.C.; Barcellos, F.G.; Alberton, O. Plant Growth and Essential Oil Content of Mentha crispa Inoculated with Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi Under Different Levels of Phosphorus. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 67, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Y.; Liu, R.Y.; Li, X.; Zheng, X.Q.; Lu, J.L.; Liang, Y.R.; Wei, C.L.; Xu, Y.Q.; Ye, J.H. CsMYB67 Participates in the Flavonoid Biosynthesis of Summer Tea Leaves. Hort. Res. 2024, 11, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betty, B.; Aziz, S.A.; Suketi, K. The Effects of Different Rates of Chicken Manure and Harvest Intervals on the Bioactive Compounds of Bitter Leaf (Vernonia amygdalina Del.). J. Trop. Crop Sci. 2021, 8, 80–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0029212. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0029212 (accessed on 28 November 2025).

- Tsimogiannis, D.; Samiotaki, M.; Panayotou, G.; Oreopoulou, V. Characterization of Flavonoid Subgroups and Hydroxy Substitution by HPLC-MS/MS. Molecules 2007, 12, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00004678817. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00000213815. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0037534. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0037534 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0030775. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0030775 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Fridén, M.E.; Sjöberg, P.J.R. Strategies for differentiation of isobaric flavonoids using liquid chromatography coupled to electrospray ionization mass spectrometry. J. Mass Spectrom. 2014, 49, 646–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0030708. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0030708 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0029500. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0029500 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0034358. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0034358 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00000848143. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0002780. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0002780 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0038361. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0038361 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0240480. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0240480 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00004706610. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Sik, B.; Kapcsándi, V.; Székelyhidi, R.; Hanczné, E.L.; Ajtony, Z. Recent Advances in the Analysis of Rosmarinic Acid from Herbs in the Lamiaceae Family. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, X.-C.; Canellas, E.; Dreolin, N.; Nerín, C. Discovery and Characterization of Phenolic Compounds in Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) Leaves Using Liquid Chromatography–Ion Mobility–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 10856–10868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buzgaia, N.; Lee, S.Y.; Rukayadi, Y.; Abas, F.; Shaari, K. Antioxidant Activity, α-Glucosidase Inhibition and UHPLC–ESI–MS/MS Profile of Shmar (Arbutus pavarii Pamp). Plants 2021, 10, 1659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, G.; Liang, J.; Chen, X.; Lin, J.; Wei, J.; Huang, D.; Zhou, Y.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, L. Isolation and Identification of Chemical Constituents from Zhideke Granules by Ultra-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Mass Spectrometry. J. Anal. Methods Chem. 2020, 2020, 8889607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0011740. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0011740 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00005746673. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Wang, B.; Lv, D.; Huang, P.; Yan, F.; Liu, C.; Liu, H. Optimization, Evaluation and Identification of Flavonoids in Cirsium setosum (Willd.) MB by Using Response Surface Methodology. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2019, 13, 1175–1184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, X.; Xu, L.; Hu, H.; Yang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Peng, Y.; Xiao, P. DPPH Radical Scavenging and Postprandial Hyperglycemia Inhibition Activities and Flavonoid Composition Analysis of Hawk Tea by UPLC-DAD and UPLC-Q/TOF MSE. Molecules 2017, 22, 1622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cao, S.; Hu, M.; Yang, L.; Li, M.; Shi, Z.; Cheng, W.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, F.; Wang, S.; Zhang, Q. Chemical Constituent Analysis of Ranunculus sceleratus L. Using Ultra-High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled with Quadrupole-Orbitrap High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry. Molecules 2022, 27, 3299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00000850520. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Jang, A.K.; Rashid, M.M.; Lee, G.; Kim, D.Y.; Ryu, H.W.; Oh, S.R.; Park, J.; Lee, H.; Hong, J.; Jung, B.H. Metabolites identification for major active components of Agastache rugosa in rat by UPLC-Orbitrap-MS: Comparison of the difference between metabolism as a single component and as a component in a multi-component extract. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 2022, 25, 114976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, D.B.; Turatti, I.C.C.; Gouveia, D.R.; Ernst, M.; Teixeira, S.P.; Lopes, N.P. Mass Spectrometry of Flavonoid Vicenin-2, Based Sunlight Barriers in Lychnophora Species. Sci. Rep. 2014, 4, 4309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saldanha, L.L.; Vilegas, W.; Dokkedal, A.L. Characterization of Flavonoids and Phenolic Acids in Myrcia bella Cambess. Using FIA-ESI-IT-MSn and HPLC-PAD-ESI-IT-MS Combined with NMR. Molecules 2013, 18, 8402–8416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.-J.; Inbaraj, B.S.; Chen, B.-H. Determination of Phenolic Acids and Flavonoids in Taraxacum formosanum Kitam by Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry Coupled with a Post-Column Derivatization Technique. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 260–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0036938. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0036938 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- MoNA–MassBank of North America. Available online: https://mona.fiehnlab.ucdavis.edu/spectra/display/VF-NPL-QTOF005732. (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- GNPS. Metabolomics USI Resolver. USI: mzspec:GNPS:GNPS:GNPS-LIBRARY:accession:CCMSLIB00000845592. Available online: https://metabolomics-usi.gnps2.org/ (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Cho, K.; Choi, Y.-J.; Ahn, Y.H. Identification of Polyphenol Glucuronide Conjugates in Glechoma hederacea var. longituba Hot Water Extracts by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS). Molecules 2020, 25, 4713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Metabolome Database. MetaboCard for HMDB0039179. Available online: https://hmdb.ca/metabolites/HMDB0039179 (accessed on 10 March 2025).

- Xiong, D.-M.; Liu, Z.; Chen, H.; Xue, J.-T.; Yang, Y.; Chen, C.; Ye, L.-M. Profiling the dynamics of abscisic acid and ABA-glucose ester after using the glucosyltransferase UGT71C5 to mediate abscisic acid homeostasis in Arabidopsis thaliana by HPLC-ESI-MS/MS. J. Pharm. Anal. 2014, 4, 190–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel Ghani, A.E.; Al-Saleem, M.S.M.; Abdel-Mageed, W.M.; AbouZeid, E.M.; Mahmoud, M.Y.; Abdallah, R.H. UPLC-ESI-MS/MS Profiling and Cytotoxic, Antioxidant, Anti-Inflammatory, Antidiabetic, and Antiobesity Activities of the Non-Polar Fractions of Salvia hispanica L. Aerial Parts. Plants 2023, 12, 1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.C.; Andreas, S.L.; Mendez, A.S.; Henriques, A.T. Cuphea Genus: A Systematic Review on the Traditional Uses, Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicology. Curr. Tradit. Med. 2024, 10, 183–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, L.; Deng, Z.; Zhang, J.; Dong, H.; Wang, W.; Xing, B.; Liu, X. Comparison of Flavonoid O-Glycoside, C-Glycoside and Their Aglycones on Antioxidant Capacity and Metabolism During In Vitro Digestion and In Vivo. Foods 2022, 11, 882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and Biochemistry of Dietary Polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ulusoy, H.G.; Sanlier, N. From Its Metabolism to Possible Mechanisms of Its Biological Activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 60, 3290–3303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.; Wang, T.; Long, M.; Li, P. Quercetin: Its Main Pharmacological Activity and Potential Application in Clinical Medicine. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2020, 1, 8825387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, L.; Wang, H.; Du, X. The Therapeutic Use of Quercetin in Ophthalmology: Recent applications. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2021, 37, 111371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deepika, M.P.K. Health Benefits of Quercetin in Age-Related Diseases. Molecules 2022, 27, 2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrillo-Martinez, E.J.; Flores-Hernández, F.Y.; Salazar-Montes, A.M.; Nario-Chaidez, H.F.; Hernández-Ortega, L.D. Quercetin, a Flavonoid with Great Pharmacological Capacity. Molecules 2024, 29, 1000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyes-Farias, M.; Carrasco-Pozo, C. The Anti-Cancer Effect of Quercetin: Molecular Implications in Cancer Metabolism. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 3177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zu, G.; Sun, K.; Li, L.; Zu, X.; Han, T.; Huang, H. Mechanism of Quercetin Therapeutic Targets for Alzheimer Disease and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 22959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, I.; Sousa, A.; Vale, A.; Carvalho, F.; Fernandes, E.; Freitas, M. Protective Effects of Flavonoids Against Silver Nanoparticles-Induced Toxicity. Arch. Toxicol. 2025, 99, 3105–3132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Petrillo, A.; Orrù, G.; Fais, A.; Fantini, M.C. Quercetin and Its Derivates as Antiviral Potentials: A Comprehensive Review. Phytother. Res. 2022, 36, 266–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The Immunomodulatory and Anti-Inflammatory Role of Polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shamsi, A.; Shahwan, M.; Khan, M.S.; Husain, F.M.; Alhumaydhi, F.A.; Aljohani, A.S.M.; Rehman, M.T.; Hassan, M.I.; Islam, A. Elucidating the Interaction of Human Ferritin with Quercetin and Naringenin: Implication of Natural Products in Neurodegenerative Diseases: Molecular Docking and Dynamics Simulation Insight. ACS Omega 2021, 6, 7922–7930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Rates * | pH (CaCl2) | P | C | Al3+ | H+ + Al3+ | Ca2+ | Mg2+ | K+ | SB | CEC | V |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg dm−3 | g dm−3 | Cmol dm−3 | % | ||||||||

| Before the experiment | |||||||||||

| 0 | 5.12 | 13.02 | 6.43 | 0 | 2.74 | 2.50 | 1.25 | 0.26 | 4.01 | 6.75 | 59.39 |

| 10 | 5.26 | 29.54 | 7.40 | 0 | 2.95 | 2.88 | 1.75 | 0.36 | 4.98 | 7.93 | 62.82 |

| 20 | 5.21 | 11.48 | 6.23 | 0 | 2.54 | 2.50 | 1.50 | 0.23 | 4.23 | 6.77 | 62.49 |

| 30 | 5.33 | 39.90 | 7.01 | 0 | 2.54 | 2.88 | 1.75 | 0.38 | 5.01 | 7.55 | 66.36 |

| 40 | 5.44 | 33.18 | 7.60 | 0 | 2.74 | 3.00 | 1.75 | 0.41 | 5.16 | 7.90 | 65.32 |

| After summer cultivation | |||||||||||

| 0 | 6.04 | 16.45 | 6.23 | 0 | 2.03 | 2.63 | 1.50 | 0.36 | 4.48 | 6.51 | 68.84 |

| 10 | 6.13 | 24.74 | 8.38 | 0 | 2.19 | 3.25 | 1.75 | 0.38 | 5.38 | 7.57 | 71.09 |

| 20 | 6.16 | 64.89 | 5.65 | 0 | 2.03 | 3.00 | 1.50 | 0.33 | 4.83 | 6.86 | 70.42 |

| 30 | 5.94 | 58.59 | 6.43 | 0 | 2.19 | 2.75 | 1.63 | 0.21 | 4.58 | 6.77 | 67.65 |

| 40 | 6.17 | 33.48 | 7.21 | 0 | 2.03 | 3.50 | 2.00 | 0.26 | 5.76 | 7.79 | 73.93 |

| After autumn/winter cultivation | |||||||||||

| 0 | 6.07 | 17.50 | 6.23 | 0 | 2.03 | 2.75 | 1.50 | 0.38 | 4.63 | 6.66 | 69.54 |

| 10 | 6.34 | 27.54 | 6.82 | 0 | 1.89 | 3.25 | 1.75 | 0.51 | 5.51 | 7.40 | 74.47 |

| 20 | 6.57 | 30.78 | 7.01 | 0 | 1.75 | 3.13 | 1.75 | 0.38 | 5.26 | 7.01 | 75.03 |

| 30 | 6.58 | 35.28 | 7.99 | 0 | 1.75 | 3.75 | 2.00 | 0.36 | 6.11 | 7.86 | 77.73 |

| 40 | 6.80 | 85.68 | 10.52 | 0 | 1.62 | 4.63 | 2.75 | 0.44 | 7.81 | 9.43 | 82.82 |

| Ref 1 | 3.8–6.6 | 16–24 | 0.8–15.9 | - | 0.6–5.0 | 0.3–7.2 | 0.3–3.3 | 0.1–0.7 | - | 2.2–12.5 | - |

| Parameters | Poultry Litter (PL) | Season (S) | PL × S |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spores (number of spores g−1 of dry soil) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.010 |

| Root colonization by AMF (%) | 0.377 | <0.001 | 0.338 |

| Microbial biomass carbon (µg CO2 g−1) | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.005 |

| Soil basal respiration (µg C-CO2 g−1 h−1) | 0.130 | 0.146 | 0.479 |

| Metabolic quotient (qCO2, µg CO2 µg−1 microbial C h−1) | 0.017 | <0.001 | 0.564 |

| Shoot fresh mass (g) | 0.120 | 0.091 | 0.686 |

| Shoot dry mass (g) | 0.222 | 0.392 | 0.818 |

| Root fresh mass (g) | 0.025 | <0.001 | 0.602 |

| Root dry mass (g) | 0.031 | <0.001 | 0.001 |

| Total fresh mass (g) | 0.090 | 0.023 | 0.812 |

| Total dry mass (g) | 0.180 | 0.154 | 0.642 |

| Extract yield (%) in the shoot | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

| Shoot nitrogen content (mg kg−1) | 0.123 | 0.178 | 0.853 |

| Root nitrogen content (mg kg−1) | 0.003 | 0.616 | 0.764 |

| Shoot phosphorus content (mg kg−1) | 0.002 | 0.102 | 0.763 |

| Root phosphorus content (mg kg−1) | 0.044 | 0.174 | 0.427 |

| Rates | Spore | Colonization | MBC | BSR | qCO2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After summer cultivation | |||||

| 0 | 1.48 ± 0.18 b | 85.67 ± 6.23 | 132.15 ± 9.77 c | 1.01 ± 0.06 b | 7.69 ± 0.23 ab |

| 10 | 4.16 ± 0.29 a | 87.37 ± 2.28 | 146.36 ± 11.83 c | 1.27 ± 0.13 ab | 8.66 ± 0.54 a |

| 20 | 4,18 ± 0.41 a | 86.15 ± 3.69 | 202.27 ± 8.25 b | 1.30 ± 0.07 ab | 6.45 ± 0.30 bc |

| 30 | 2.33 ± 0.08 b | 91.30 ± 0.81 | 262.55 ± 28.00 a | 1.32 ± 0.01 a | 5.16 ± 0.58 c |

| 40 | 2.18 ± 0.77 b | 84.26 ± 2.07 | 246.91 ± 19.83 ab | 1.51 ± 0.12 a | 6.27 ± 1.01 bc |

| Sig. | 0.003 | 0.690 | 0.001 | 0.036 | 0.017 |

| After autumn/winter cultivation | |||||

| 0 | 1.10 ± 0.18 | 28.33 ± 1.67 | 113.73 ± 3.22 c | 1.29 ± 0.18 | 11.24 ± 1.39 |

| 10 | 1.70 ± 0.40 | 20.11 ± 4.91 | 119.44 ± 3.34 bc | 1.43 ± 0.14 | 12.03 ± 1.37 |

| 20 | 1.93 ± 0.22 | 24.11 ± 9.63 | 150.50 ± 12.59 a | 1.38 ± 0.12 | 9.27 ± 1.01 |

| 30 | 1.41 ± 0.11 | 17.56 ± 2.41 | 141.02 ± 11.58 ab | 1.48 ± 0.08 | 10.52 ± 0.27 |

| 40 | 1.31 ± 0.04 | 12.22 ± 2.42 | 154.96 ± 4.91 a | 1.38 ± 0.10 | 8.95 ± 0.92 |

| Sig. | 0.335 | 0.290 | 0.017 | 0.869 | 0.282 |

| Rates | SFM | RFM | TFM | SDM | RDM | TDM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| After summer cultivation | ||||||

| 0 | 1.42 ± 0.31 | 0.31 ± 0.04 | 1.73 ± 0.35 | 0.41 ± 0.09 | 0.06 ± 0.01 | 0.47± 0.10 |

| 10 | 1.66 ± 0.48 | 0.57 ± 0.20 | 2.22 ± 0.69 | 0.50 ± 0.12 | 0.05 ± 0.01 | 0.55 ± 0.12 |

| 20 | 1.93 ± 0.53 | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 2.23 ± 0.62 | 0.56 ± 0.16 | 0.07 ± 0.01 | 0.63 ± 0.16 |

| 30 | 2.37 ± 0.30 | 0.40 ± 0.02 | 2.77 ± 0.31 | 0.67 ± 0.11 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.74 ± 0.12 |

| 40 | 2.16 ± 0.49 | 0.31 ± 0.01 | 2.47 ± 0.49 | 0.62 ± 0.16 | 0.08 ± 0.01 | 0.69 ± 0.17 |

| Sig. | 0.572 | 0.370 | 0.702 | 0.670 | 0.373 | 0.662 |

| After autumn/winter cultivation | ||||||

| 0 | 1.60 ± 0.26 b | 0.42 ± 0.04 b | 2.02 ± 0.26 b | 0.43 ± 0.05 | 0.08 ± 0.01 b | 0.51 ± 0.05 b |

| 10 | 2.73 ± 0.43 ab | 0.79 ± 0.07 a | 3.52 ± 0.50 a | 0.74 ± 0.11 | 0.16 ± 0.02 a | 0.90 ± 0.13 a |

| 20 | 1.97 ± 0.28 ab | 0.68 ± 0.10 ab | 2.65 ± 0.36 ab | 0.57 ± 0.08 | 0.12 ± 0.01 b | 0.69 ± 0.08 ab |

| 30 | 2.64 ± 0.47 ab | 0.75 ± 0.09 a | 3.39 ± 0.44 a | 0.71 ± 0.12 | 0.12 ± 0.01 b | 0.83 ± 0.11 ab |

| 40 | 2.83 ± 0.25 a | 0.51 ± 0.10 ab | 3.34 ± 0.26 a | 0.61 ± 0.10 | 0.11 ± 0.01 b | 0.72 ± 0.09 ab |

| Sig. | 0.047 | 0.048 | 0.047 | 0.231 | 0.004 | 0.048 |

| Rates | SN | RN | SP | RP |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| After summer cultivation | ||||

| 0 | 22.17 ± 0.93 | 17.33 ± 0.44 b | 1.52 ±0.01 b | 1.15 ± 0.07 b |

| 10 | 26.50 ± 2.78 | 20.17 ± 1.17 ab | 1.56 ± 0.06 b | 1.58 ± 0.02 a |

| 20 | 27.67 ± 3.61 | 19.50 ± 1.04 ab | 1.61 ± 0.03 ab | 1.42 ± 0.15 ab |

| 30 | 25.17 ± 0.33 | 21.50 ± 0.76 a | 1.69 ± 0.03 a | 1.62 ± 0.05 a |

| 40 | 26.00 ± 1.00 | 20.17 ± 1.17 ab | 1.71 ± 0.03 a | 1.48 ± 0.07 a |

| Sig. | 0.478 | 0.041 | 0.014 | 0.022 |

| After autumn/winter cultivation | ||||

| 0 | 21.33 ± 1.45 b | 17.17 ± 0.73 b | 1.40 ± 0.04 b | 1.28 ± 0.06 |

| 10 | 24.17 ± 0.88 ab | 19.17 ± 0.33 ab | 1.54 ± 0.05 ab | 1.41 ± 0.11 |

| 20 | 24.17 ± 0.93 ab | 18.50 ± 1.00 ab | 1.50 ± 0.05 ab | 1.31 ± 0.07 |

| 30 | 24.00 ± 1.53 ab | 21.00 ± 1.00 a | 1.70 ± 0.10 a | 1.38 ± 0.06 |

| 40 | 26.17 ± 1.17 a | 21.33 ± 1.20 a | 1.65 ± 0.09 a | 1.42 ± 0.18 |

| Sig. | 0.047 | 0.042 | 0.048 | 0.844 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ribeiro, J.K.O.; Pinc, M.M.; Baisch, R.G.; Barbosa, M.P.d.S.B.; Hoscheid, J.; Rezende, M.K.A.; Macruz, P.D.; Pilau, E.J.; Jacomassi, E.; Alberton, O. Seasonal Evaluation and Effects of Poultry Litter-Based Organic Fertilization on Sustainable Production and Secondary Metabolism of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310801

Ribeiro JKO, Pinc MM, Baisch RG, Barbosa MPdSB, Hoscheid J, Rezende MKA, Macruz PD, Pilau EJ, Jacomassi E, Alberton O. Seasonal Evaluation and Effects of Poultry Litter-Based Organic Fertilization on Sustainable Production and Secondary Metabolism of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310801

Chicago/Turabian StyleRibeiro, Joice Karina Otênio, Mariana Moraes Pinc, Rosselyn Gimenes Baisch, Marina Pereira da Silva Bocchio Barbosa, Jaqueline Hoscheid, Maiara Kawana Aparecida Rezende, Paula Derksen Macruz, Eduardo Jorge Pilau, Ezilda Jacomassi, and Odair Alberton. 2025. "Seasonal Evaluation and Effects of Poultry Litter-Based Organic Fertilization on Sustainable Production and Secondary Metabolism of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310801

APA StyleRibeiro, J. K. O., Pinc, M. M., Baisch, R. G., Barbosa, M. P. d. S. B., Hoscheid, J., Rezende, M. K. A., Macruz, P. D., Pilau, E. J., Jacomassi, E., & Alberton, O. (2025). Seasonal Evaluation and Effects of Poultry Litter-Based Organic Fertilization on Sustainable Production and Secondary Metabolism of Cuphea carthagenensis (Jacq.) J. F. Macbr. Sustainability, 17(23), 10801. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310801