Analysis of Specific Habitat Conditions for Fish Bioindicator Species Under Climate Change with Machine Learning—Case of Sutla River

Abstract

1. Introduction

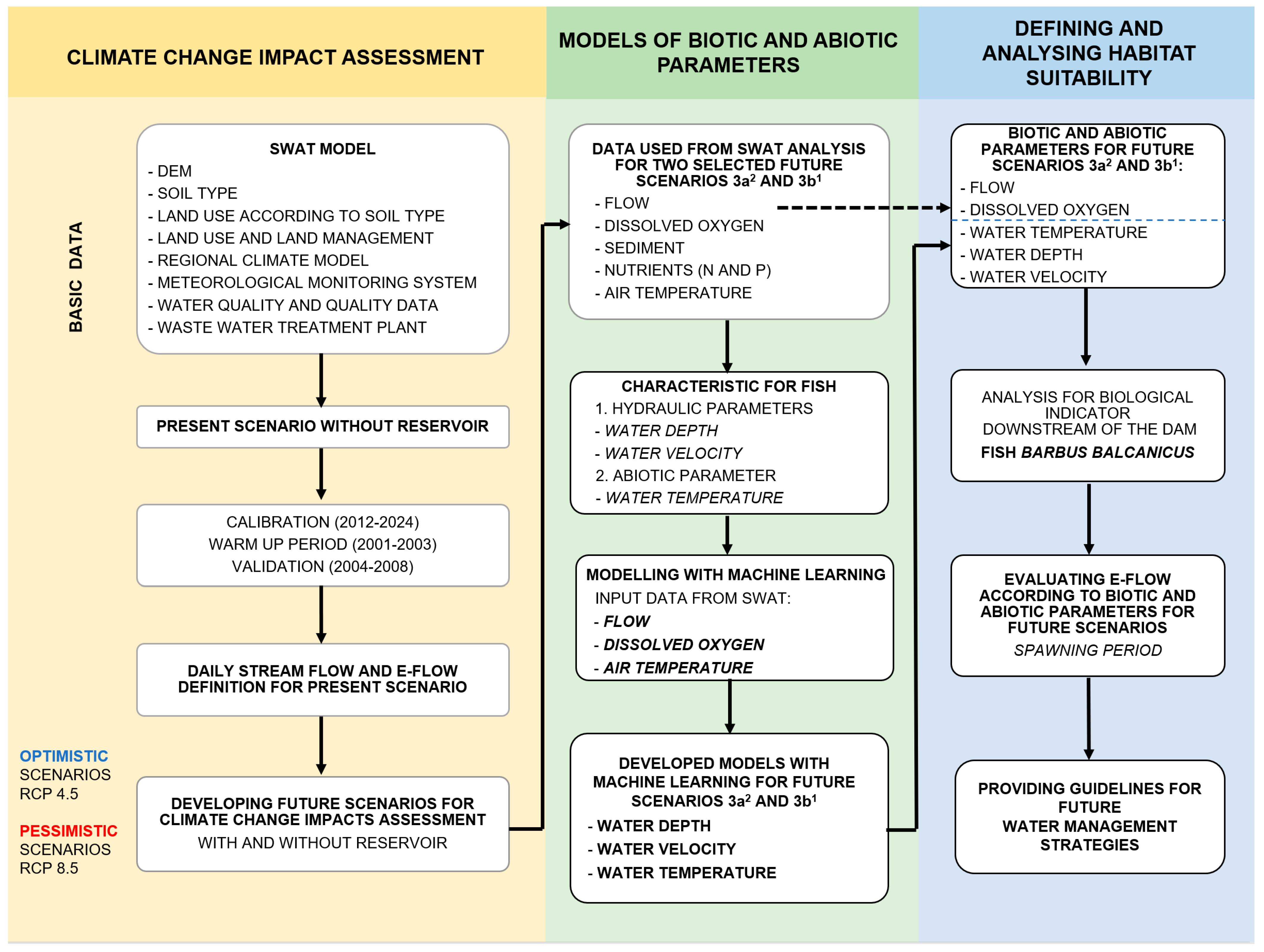

2. Materials and Methods

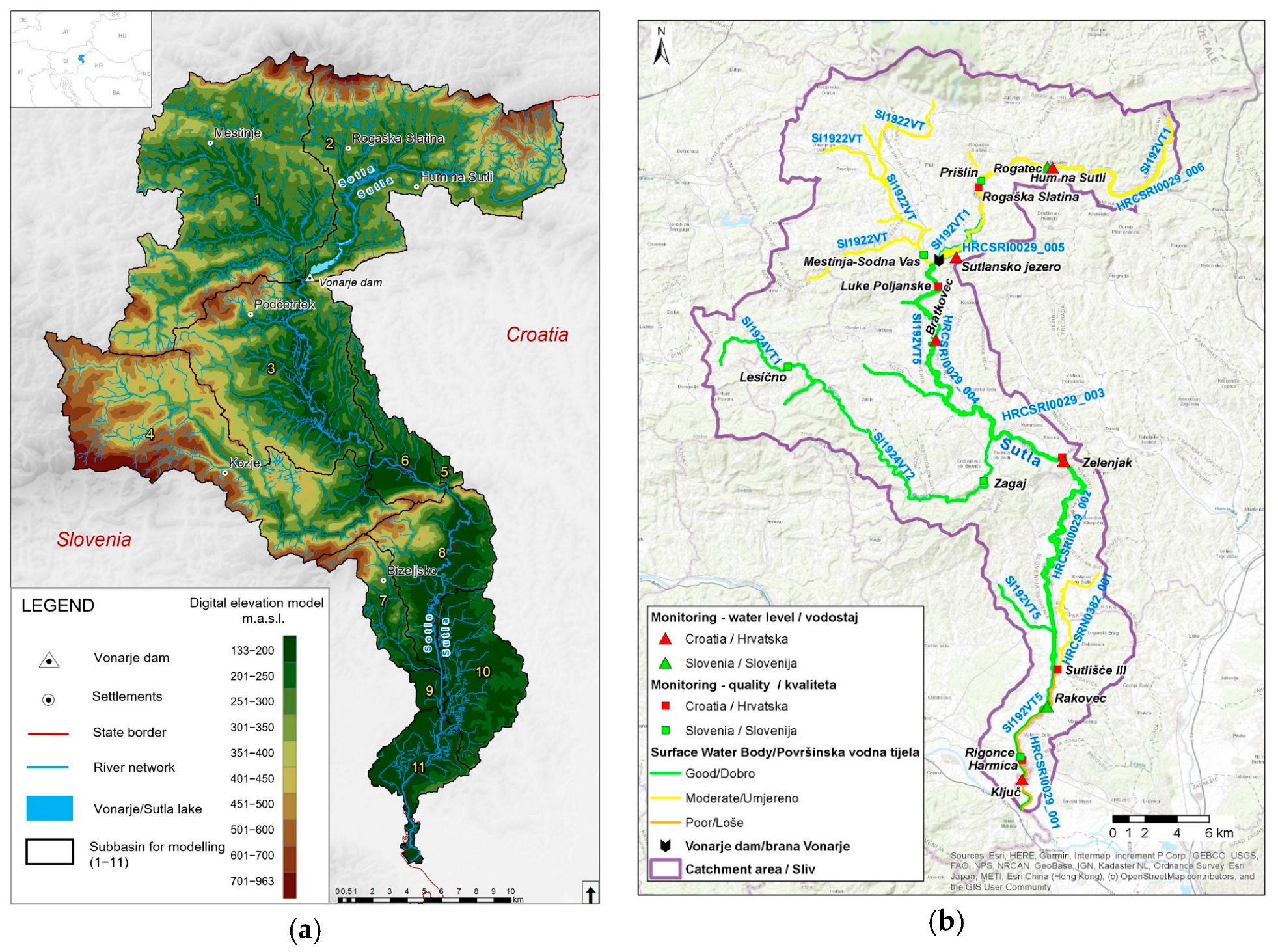

2.1. Sutla River Basin

2.2. Biological Indicators

2.3. Methodology

- Analyses of river basin pressures under CC impact by the SWAT model;

- Programme of basic and supplementary measures;

- Hydrological analysis and abiotic factors;

- Biological research.

- (a) With reservoir: 3a1, 3a2, 3a3 and 3a4,

- (b) Without reservoir: 3b1, 3b2, 3b3 and 3b4,

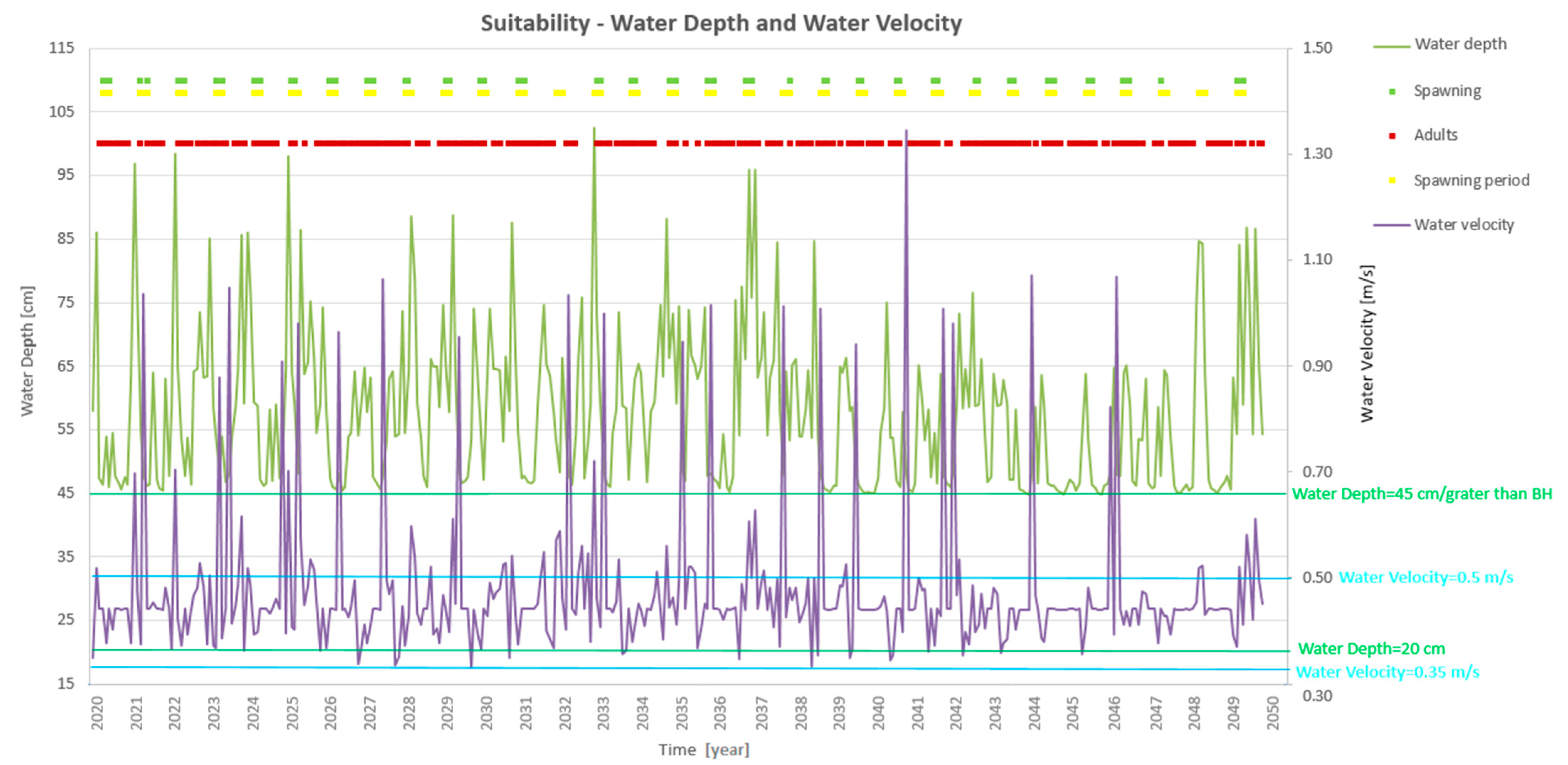

3. Results

- 64.78% of the flow for the FUTURE 3a2 scenario and 60.48% for the FUTURE 3b1 scenario are higher than the defined E-flow, 0.98 m3/s;

- 68.8% of spawning conditions were individually met for the indicator species used in defining E-flow and specific habitat conditions for the FUTURE 3a2 scenario;

- 66.7% of spawning conditions were individually met for the indicator species used in defining E-flow and specific habitat conditions for the FUTURE 3b1 scenario.

4. Discussion

- All available monitoring data have been checked, and a continuous series of at least 20 years has been used. Existing data, which are requested by WFD, are not fully implemented in the monitoring programme and are insufficient for detailed analysis and modelling of specific habitat conditions for fish bioindicator species, since hydrological monitoring and surface water quality monitoring are not always well coordinated. The assessment of key abiotic factors for fish/specific habitat conditions requires an interdisciplinary approach and investigative monitoring.

- It is important to emphasise that the profiles for hydrological measurements are not exactly located at the same microlocality as the water quality measuring stations, where samples for monitoring the water state are taken. This may explain why unfavourable hydrological conditions for the stream brook barbel occur even in the current state, or it could be that the profile is not the most representative, while the rest of the riverbed provides favourable hydrological and hydraulic conditions for brook barbel settlement.

- The Zelenjak monitoring station is the most suitable monitoring station because it is a hydrological and water quality station. Daily flow values were converted into monthly flow values because water quality at the same measuring station is measured once a month. It is also a station with a very long working period, established in mid-1957, and in 1979, the limnigraph was replaced by an automatic measuring station that measures water levels and flows. During this long measurement period, the water quality measuring station was the same on the left bank (the Croatian side of the Sutla River). At the Zelenjak hydrographic measuring station during the analysed period, where both water level and flow are measured, the flow curve was changed 9 times to calibrate the “0” level, the cross-section was recorded 9 times, and the instruments of the automatic water level measuring station were used.

- Across all scenarios, the limited availability of high-quality data for habitat modelling presents a major challenge in defining E-flow parameters, such as water temperature, water depth, and water velocity.

- When talking about a small number of brook barbel specimens, it should always be emphasised that along with brook barbel, there are also accompanying species that are characteristic of inhabiting medium-sized streams [21]. For biology, it is important to state that the results of the analysis of the biological elements of water quality are collected once every three years. For a complete and detailed analysis, biological material should be collected for at least one full year (spring, summer, autumn, and winter) and at least seasonally (spring, summer), because in this way, the actual dynamics, composition, and structure of the ichthyofauna would be seen, and it could be known whether all hydrological and hydraulic conditions for brook barbel settlement are met.

- It is also important to emphasise that the sediment was not analysed in the ML analyses, of course, because there are not enough measurements. Therefore, in future analysis research, this should be considered. During interpretation, we should bear in mind that the results of the analysis would certainly be different if the transport of sediment were also considered; that is, we are missing the sediment part in the future scenarios.

- E-flow, and specific habitat conditions for bioindicator species, are the quantity of water that provides for an ecological balance and preserves the natural stability of an aquatic ecosystem.

- Any water abstraction from any part of a watercourse requires an investigation into the consequences that such activity could cause to an aquatic ecosystem.

- Special attention should be paid to protecting rare and endangered flora and fauna, which is important for ecological balance, while taking care of flora and fauna as a basic link in the food chain.

- Regarding the quantity and quality of water, all changes in the watercourse must be analysed to define/check the E-flow and specific habitat conditions for fish bioindicator species.

- Since every watercourse is specific for its natural characteristics and hydraulic engineering facilities—already built or planned to be built—it is important to have all the related data.

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Poff, N.L.R.; Matthews, J.H. Environmental flows in the Anthropocene: Past progress and future prospects. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 667–675. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćosić-Flajsig, G.; Vučković, I.; Karleuša, B. An Innovative Holistic Approach to an E-flow Assessment Model. Civ. Eng. J. 2020, 6, 2188–2202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Climate Change 2022—Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2023; p. 3056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acreman, M.C.; Ferguson, A.J.D. Environmental flows and the European Water Framework Directive. Freshw. Biol. 2010, 55, 32–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Escribano Francés, G.; Quevaviller, P.; San Martín González, E.; Vargas Amelin, E. Climate change policy and water resources in the EU and Spain. A closer look into the Water Framework Directive. Environ. Sci. Pol. 2017, 69, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cowx, I.G.; Welcomme, L.R. Rehabilitation of Rivers for Fish; Fishing News Books: London, UK, 1998; 260p. [Google Scholar]

- Schneider, C.; Laize, C.L.R.; Acreman, M.C.; Flörke, M. How will climate change modify river flow regimes in Europe? Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2013, 17, 325–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korkmaz, M.; Mangıt, F.; Dumlupınar, İ.; Çolak, M.A.; Akpınar, M.B.; Koru, M.; Pacheco, J.P.; Ramírez-García, A.; Yılmaz, G.; Amorim, C.A.; et al. Effects of Climate Change on the Habitat Suitability and Distribution of Endemic Freshwater Fish Species in Semi-Arid Central Anatolian Ecoregion in Türkiye. Water 2023, 15, 1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gizinska, J.; Sojka, M. How Climate Change Affects River and Lake Water Temperature in Central-West Poland-A Case Study of the Warta River Catchment. Atmosphere 2023, 14, 330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morrill, J.C.; Bales, R.C.; Conklin, M.H. Estimating stream temperature from air temperature: Implications for future water quality. J. Environ. Eng. 2005, 131, 139–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, R. A multifaceted analysis of the relationship between daily temperature of river water and air. Acta Geophys. 2019, 67, 905–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabi, A.; Hadzima-Nyarko, M.; Šperac, M. Modelling River temperature from air temperature: Case of the River Drava (Croatia). Hydrol. Sci. J. 2014, 60, 1490–1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ćosić-Flajsig, G.; Karleuša, B.; Glavan, M. Integrated Water Quality Management Model for the Rural Transboundary River Basin—A Case Study of the Sutla/Sotla River. Water 2021, 13, 2569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leone, M.; Gentile, F.; Lo Porto, A.; Ricci, G.F.; Schürz, C.; Strauch, M.; Volk, M.; De Girolamo, A.M. Setting an environmental flow regime under climate change in a data-limited Mediterranean basin with temporary river. J. Hydrol. Reg. Stud. 2024, 52, 101698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghobadi, F.; Kang, D. Application of Machine Learning in Water Resources Management: A Systematic Literature Review. Water 2023, 15, 620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozcan, G.E.; Ünel, E.; Sivrikaya, F. A Machine Learning Algorithm-Based Approach (MaxEnt) for Predicting Habitat Suitability of Formica rufa. J. Appl. Entomol. 2025, 149, 558–572. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edrisnia, S.; Etemadi, M.; Pourghasemi, H.R. Machine learning-driven habitat suitability modeling of Suaeda aegyptiaca for sustainable industrial cultivation in saline regions. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120427. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Croatian Ministry of Health. Regulation on Water Quality Standards. In Official Gazette 2023, 20/23; Croatian Ministry of Health: Zagreb, Croatia, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Mrakovčić, M.; Brigić, A.; Buj, I.; Ćaleta, M.; Mustafić, P.; Zanella, D. Red Book of Freshwater Fish of Croatia; Ministry of Culture, State Institute for Nature Protection, Republic of Croatia: Zagreb, Croatia, 2006. Available online: https://www.haop.hr/sites/default/files/uploads/dokumenti/03_prirodne/crvene_knjige_popisi/Crvena_knjiga_slatkovodnih_riba-web.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- The IUCN Red List. Available online: https://www.iucnredlist.org/ (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Mrakovčić, M. Criteria for determining sustainable flow based on fish communities. In Documentation Elektroprojekt d.d.; Elektroprojekt: Zagreb, Croatia, 2000; p. 41. [Google Scholar]

- Ćosić-Flajsig, G.; Karleuša, B.; Vučković, I.; Glavan, M. E-flow Holistic Assessment in Data-limited River Basin under Climate Change Impact. In Proceedings of the WMHE 2024, Štrbské Pleso, High Tatras, Slovakia, 10–14 September 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Witten, I.H.; Frank, E. Data Mining: Practical Machine Learning Tools and Techniques, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Witten, I.H. Inducing model trees for continuous classes. In Proceedings of the 9th European Conference on Machine Learning, Prague, Czech Republic, 23–25 April 1997. [Google Scholar]

| Key Abiotic Factors Important for Fish Communities | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biogeographical Area | Life Stage | Water Depth cm | Water Velocity m/s | Water Temperature °C | Dissolved Oxygen mg/L |

| Barbus balcanicus brook barbel | Spawning | Greater than body height 20–45 | 0.35–0.5 | 4–17 (14) * | Above 6 |

| <Fry | About 30 | 0.06–0.2 | (15) * | Above 6 | |

| Adults | Greater than body height 20–45 | 0.35–0.5 | 4–20 | Above 6 | |

| Scenario | Qav,year (m3/s) | Sediment (t) | TN (t) | TP (t) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESENT 1 | 1.67 (m3/s) | 2409 (t) | 298,275 (t) | 19,957 (t) |

| PAST 2a | 2% | 62% | 42% | 59% |

| PAST 2b | 0% | 62% | 42% | 39% |

| FUTURE 3a1 | 6% (−9; 17) | 7% (−15; 18) | 0% (−10; 7) | 0% (−5; 4) |

| FUTURE 3a2 | 21% (−4; 49) | 14% (−18; 44) | 7% (−17; 26) | 0% (−9; 7) |

| FUTURE 3a3 | 14% (3; 33) | 14% (−5; 29) | 4% (−8; 17) | 1% (−3; 5) |

| FUTURE 3a4 | 28% (5; 91) | 20% (−13; 105) | 8% (−10; 50) | 0% (−8; 15) |

| FUTURE 3b1 | 4% (−12; 15) | 10% (−16; 23) | 2% (−10; 13) | 0% (−5; 4) |

| FUTURE 3b2 | 18% (−6; 44) | 14% (−18; 44) | 7% (−12; 26) | 0% (−9; 7) |

| FUTURE 3b3 | 11% (1; 30) | 14% (−5; 29) | 4% (−8; 17) | 1% (−3; 5) |

| FUTURE 3b4 | 25% (3; 86) | 20% (−13; 104) | 8% (−10; 51) | 0% (−8; 15) |

| Scenario | Qav, month (m3/s) av. (Min, Max) | Qav, month (m3/s) Dry Period (April–September) av. (Min, Max) | Qav, month (m3/s) Wet Period (October–March) av. (Min, Max) | DOav, month (mg/L) av. (Min, Max) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PRESENT 1 | 4.88 (0.39; 58.3) | 4.43 (0.39; 58.3) | 5.66 (0.69; 58) | 10.63 (6.1; 17.6) |

| FUTURE 3a2 | 1.68 (0.14;7.27) | 2.36 (0.13; 6.97) | 1.94 (0.19; 6.26) | 7.14 (1.46; 12.43) |

| FUTURE 3b1 | 1.46 (0.08; 7.40) | 1.31 (0.09; 5.99) | 1.69 (1.10; 6.00) | 7.02 (1.55; 14.35) |

| Equation No. | Equation |

|---|---|

| LM 1. | Water Temp = 0.1322 × Air Temp − 0.3111 × Dis. Oxygen + 12.5546 |

| LM 2. | Water Temp = 0.1417 × Air Temp − 0.1885 × Dis. Oxygen + 6.0976 |

| LM 3. | Water Temp = 0.1538 × Air Temp − 0.1885 × Dis. Oxygen + 8.11 |

| LM 4. | Water Temp = 0.138 × Air Temp − 0.5352 × Dis. Oxygen + 18.8255 |

| LM 5. | Water Temp = 0.138 × Air Temp − 0.3897 × Dis. Oxygen + 15.7557 |

| LM 6. | Water Temp = 0.1912 × Air Temp − 0.429 × Dis. Oxygen + 19.3492 |

| LM 7. | Water Temp = 0.1912 × Air Temp − 0.6061 × Dis. Oxygen + 19.5212 |

| LM 8. | Water Temp = 0.303 × Air Temp − 0.4584 × Dis. Oxygen + 17.9846 |

| Equation No. | Equation |

|---|---|

| LM 1. | Water Depth = 3.5252 × Flow + 44.5565 |

| LM 2. | Water Depth = 3.8616 × Flow + 49.0192 |

| LM 3. | Water Depth = 3.9451 × Flow + 51.8193 |

| LM 4. | Water Depth = 3.4175 × Flow + 56.2257 |

| LM 5. | Water Depth = 4.3769 × Flow + 59.4978 |

| LM 6. | Water Depth = 3.0882 × Flow + 70.4646 |

| LM 7. | Water Depth = 2.7699 × Flow + 78.3939 |

| LM 8. | Water Depth = 1.7687 × Flow + 127.308 |

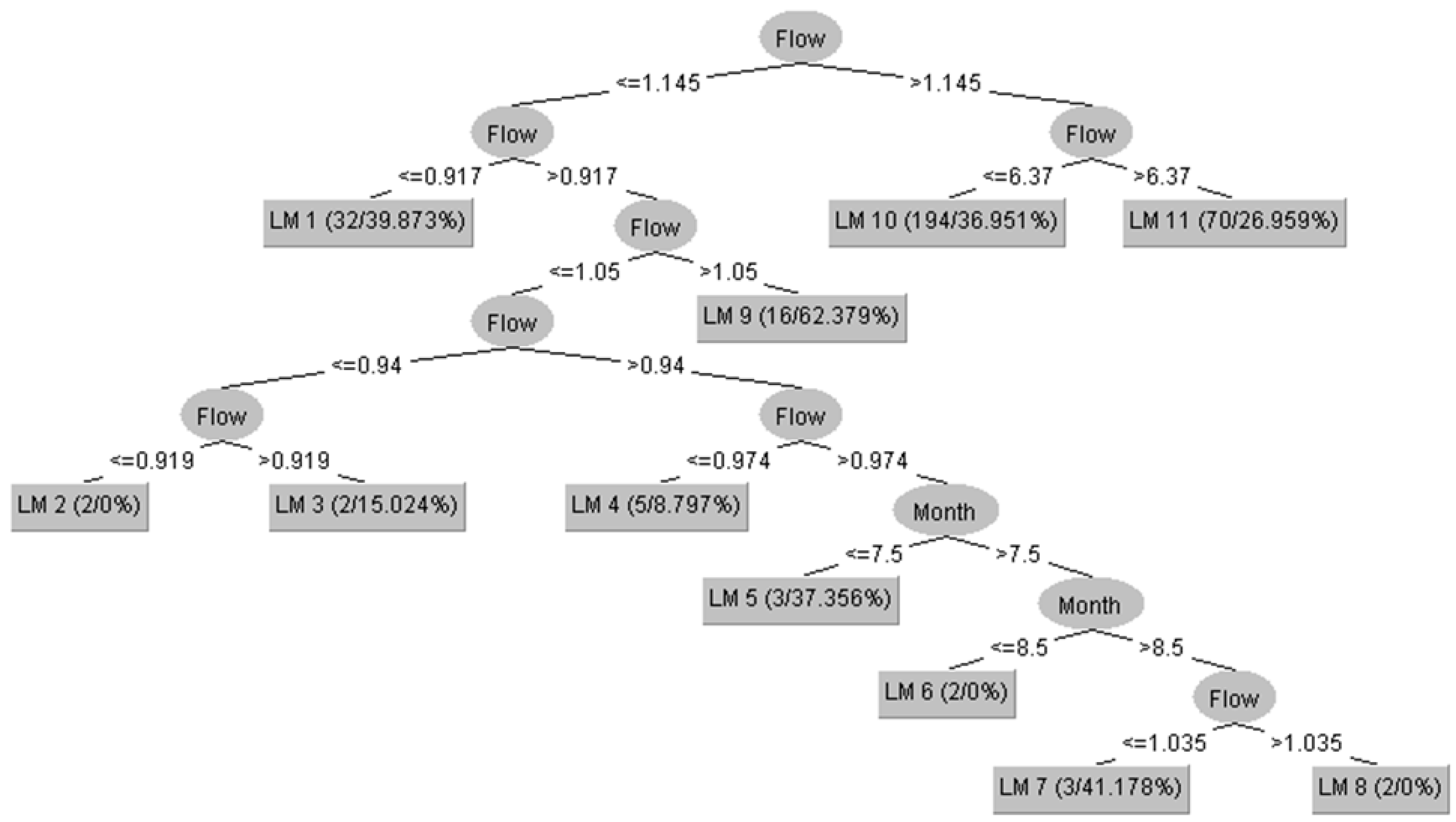

| Equation No. | Equation |

|---|---|

| LM 1. | Water Velocity = 0.003 × Flow + 0.4397 |

| LM 2. | Water Velocity = −24.6558 × Flow + 24.1276 |

| LM 3. | Water Velocity = −24.6558 × Flow + 24.0777 |

| LM 4. | Water Velocity = −2.2376 × Flow + 3.1806 |

| LM 5. | Water Velocity = −2.2376 × Flow + 3.2286 |

| LM 6. | Water Velocity = −0.0394 × Month − 2.2376 × Flow + 3.5946 |

| LM 7. | Water Velocity = −0.0335 × Month − 2.2376 × Flow + 3.5355 |

| LM 8. | Water Velocity = −0.0335 × Month − 2.2376 × Flow + 3.5369 |

| LM 9. | Water Velocity = −2.4544 × Flow + 3.1987 |

| LM 10. | Water Velocity = 0.0103 × Month + 0.0461 × Flow + 0.2659 |

| LM 11. | Water Velocity = 0.0114 × Flow + 0.6208 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ćosić-Flajsig, G.; Volf, G.; Vučković, I.; Karleuša, B. Analysis of Specific Habitat Conditions for Fish Bioindicator Species Under Climate Change with Machine Learning—Case of Sutla River. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310803

Ćosić-Flajsig G, Volf G, Vučković I, Karleuša B. Analysis of Specific Habitat Conditions for Fish Bioindicator Species Under Climate Change with Machine Learning—Case of Sutla River. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310803

Chicago/Turabian StyleĆosić-Flajsig, Gorana, Goran Volf, Ivan Vučković, and Barbara Karleuša. 2025. "Analysis of Specific Habitat Conditions for Fish Bioindicator Species Under Climate Change with Machine Learning—Case of Sutla River" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310803

APA StyleĆosić-Flajsig, G., Volf, G., Vučković, I., & Karleuša, B. (2025). Analysis of Specific Habitat Conditions for Fish Bioindicator Species Under Climate Change with Machine Learning—Case of Sutla River. Sustainability, 17(23), 10803. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310803