Impact of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency on Contract Farming Coverage and Regional Differences: Evidence from China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Contract Farming

2.2. Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency

2.3. The Relationship Between Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency and Contract Farming

3. Theoretical Analysis and Hypotheses

3.1. Theoretical Basis: Transaction Cost Theory in Agriculture

3.2. Hypotheses

4. Research Design

4.1. Construction and Calculation of Comprehensive Index System of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency

4.2. The Economic Model

4.3. Variable Selection and Description

4.3.1. Explained Variable

4.3.2. Core Explanatory Variables

4.3.3. Control Variables

4.3.4. Data Source

4.3.5. Data Description

- (1)

- Descriptive analysis of variables

- (2)

- Correlation analysis of variables

- (3)

- Multicollinearity analysis of variables

5. Empirical Analysis Results

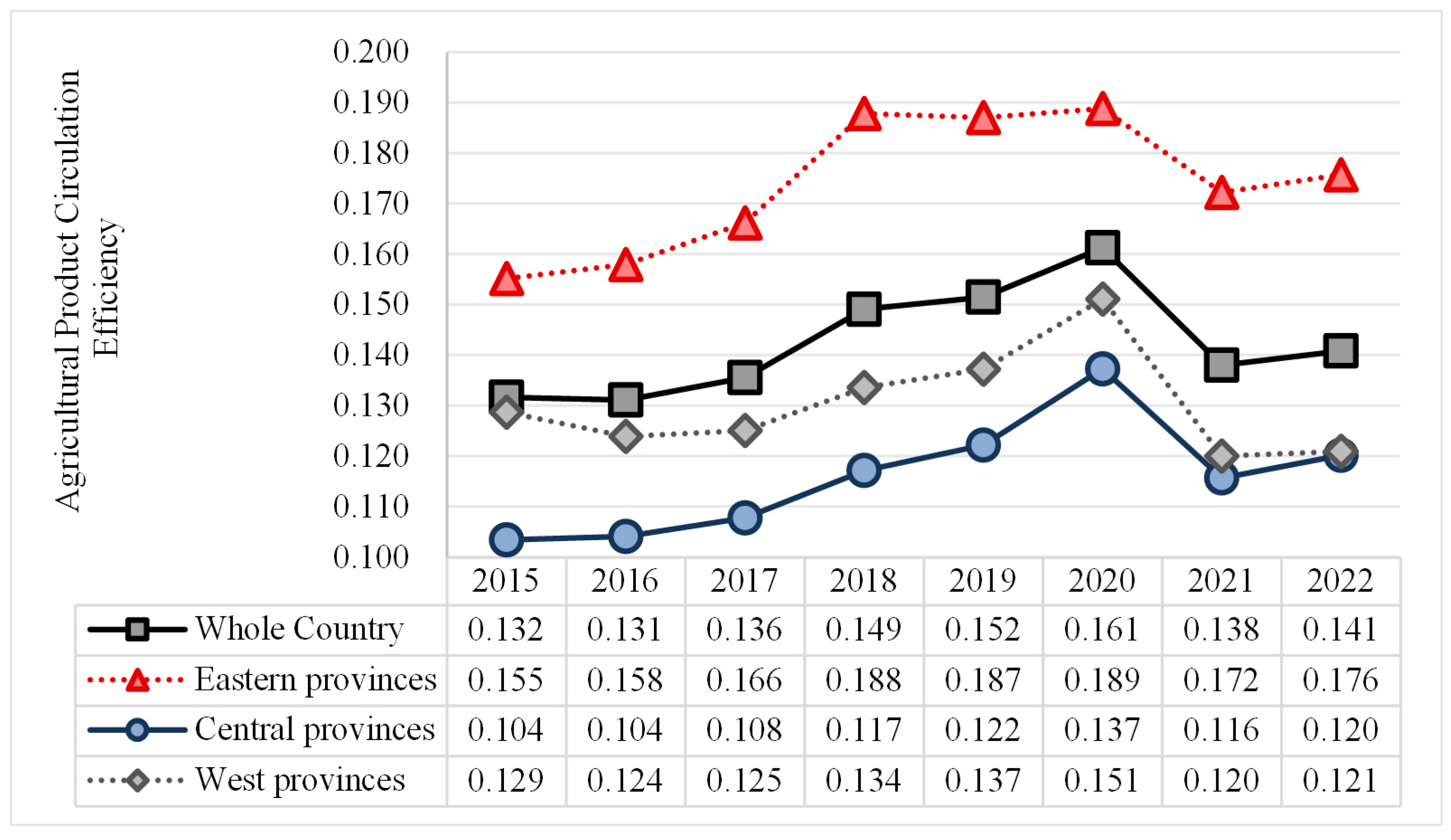

5.1. Descriptive Analysis: Measurement Results of Comprehensive Index of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency

5.2. Baseline Regression Results

5.3. Robustness Tests

5.4. Mechanism Tests

5.5. Heterogeneity Analysis

5.5.1. Spatial Gini Index

5.5.2. Regression in Different Regions

5.5.3. Discussion

6. Conclusions and Implications

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Han, C.F. Actively Promote the Organic Connection Between Small Farmers and Modern Agriculture Development. Rural Pract. Technol. 2018, 3, 22–24. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, H.H.; Wang, Y.; Delgado, M.S. The Transition to Modern Agriculture: Contract Farming in Developing Countries. Am. J. Agric. Econ. 2014, 5, 1257–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otsuka, K.; Nakano, Y.; Takahashi, K. Contract Farming in Developed and Developing Countries. Annu. Rev. Resour. Econ. 2016, 8, 353–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maertens, M.; Velde, K.V. Contract-farming in Staple Food Chains: The Case of Rice in Benin. World Dev. 2017, 95, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ton, G.; Vellema, W.; Desiere, S.; Weituschat, S.; D’Haese, M. Contract farming for improving smallholder incomes: What can we learn from effectiveness studies? World Dev. 2018, 104, 46–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanal, A.; Mishra, A.; Joaquín, M.; Stefan, H. Choice of Contract Farming Strategies, Productivity, and Profits: Evidence from High-Value Crop Production. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2020, 45, 589–602. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Chen, Y. The Impact of Contract Farming on Agricultural Product Supply in Developing Economies. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2021, 30, 2395–2419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiringo, L.; Chundu, M.; Sithole, P. Contribution of Smallholder Tobacco Contract Farming to Economic and Human Development of Rural Communities in Zimbabwe: A Case of Igava Community, Marondera District. Open J. Soc. Sci. 2022, 10, 36–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndip, F.; Sakurai, T. Enhancing Agricultural Intensification through Contract Farming: Evidence from Rice Production in Senegal. Agric. Food Secur. 2025, 14, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Research Group of the Rural Department of the State Council Research Office. Forms, Functions, and Suggestions for the Development of Contract Agriculture. Issues Agric. Econ. 2001, 3, 43–46. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, Q. Research on the Efficiency and Improvement Path of Agricultural Product Circulation in China. Doctoral Dissertation, Beijing Jiaotong University, Beijing, China, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Xia, C. Research on Mechanism Innovation and Policy System of Agricultural Product Circulation System Construction; Economic Science Press: Beijing, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.Q.; Qi, C.J.; Tang, L.Y. Evaluation and Spatio-temporal Analysis of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency in the Context of Unified Domestic Market: From the “Three Dimensional” Perspective of Modern Circulation Theory. Issues Agric. Econ. 2023, 8, 127–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, F.M.; Zhu, R.; Yuan, B.F.; Fan, X.M.; Zhang, Y.D. Configuration Analysis of Factors Ineluencing Demand for Agricultural Cold Chain Logistics: A Toe Framework Perspective. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2025, 8, 217–227. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.H.; Wu, L.Q. The Spatiotemporal Evolution Characteristics of Cold Chain Logistics Efficiency for Agricultural Products in China. J. Jishou Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2025, 46, 1–11. Available online: https://link.cnki.net/urlid/43.1069.c.20241225.1701.004 (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Huang, F.H.; Jiang, X.L. Research on the Influencing Factors and Improvement Modes of Logistics Efficiency of Fresh Agricultural Products. J. Beijing Technol. Bus. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2017, 2, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.H.; Wen, J.Y. The Logistics Efficiency of Agricultural Products in China and Its Regional Differences: SFA Analysis Based on Inter Provincial Panel Data. Contemp. Econ. Manag. 2015, 37, 26–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.F. Research on the Measurement and Influencing Factors of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency in China. Master’s Thesis, Northeast Agricultural University, Harbin, China, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, F.Q. Incomplete Contract and the Barrier to Performance: A Case Research on the Farm Produce for Oder. Econ. Res. J. 2003, 4, 22–30+92. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L.R. The Path, Mechanism, and Conditions for Connecting Small and Medium sized Farmers with Modern Agriculture in Industrial Revitalization: A Case Study of Contract Farming. Guizhou Soc. Sci. 2021, 2, 156–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.H. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Contract Farming and Its Organizational Model on Farmers’ income. Chin. Rural Econ. 2009, 4, 39–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, K.; Ma, J.J. Empirical Study on the Behavioral Choices and Determining Factors of Farmers’ Participation in Contract Farming. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2010, 9, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Hou, B. Farmers’ Participation Behavior in Contract Farming and its Influencing Factors: Based on the Theory of Planned Behavior. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2018, 19, 17–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoang, V.; Nguyen, V. Determinants of Small Farmers’ Participation in Contract Farming in Developing Countries: A Study in Vietnam. Agribusiness 2023, 39, 836–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nazif, B.; Hussaini, Y. Determinants of Participation in Contract Farming among Smallholder maize Farmers in North-Western Nigeria. Acta Sci. Pol. Agric. 2022, 20, 147–160. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.H.; Zhang, Y.L. Analysis of Vertical Collaboration Selection Behavior of Subjects in the Conrtract Farming Model. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2017, 11, 104–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.F.; Huang, Y.; Tang, S. Exploring the Efficiency and Motivation of Contract Fulfillment between Leading Enterprises and Farmers: Survey Data from 91 Agricultural Enterprises. Issues Agric. Econ. 2014, 11, 16–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakostas, A.; De Souza Monteiro, D.M.; Adjei, C. Double Moral Hazard in Contract Farming: An Experimental Analysis. J. Agric. Econ. 2025, 76, 640–650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, X.D. The Contractual Dilemma of Contract Farming and the Evolution of Organizational Forms. Chin. Rural Econ. 2007, 12, 35–39+46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, L.G.; Chen, W.D. Green Technology Adoption Strategies of Contract Farming Supply Chain under Agricultural Insurance. Chin. J. Manag. Sci. 2024, 9, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, H.J.; Pang, T. Financing and Operational Strategies for the Contract-Farming Supply Chain under Agricultural Subsidy Policy. J. Ind. Eng. Eng. Manag. 2020, 34, 155–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, T.; Liu, T.T. Innovations and Future Breakthroughs of Financial Services in Contract Farming: A Multi-Case Study of Rural Financial Reform Pilot Zones. Rural Econ. 2025, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Zhong, Y.; Zhang, G.; Zhai, T.; Li, Z.; Lin, S. Individual Action or Collaborative Scientific Research Institutions? Agricultural Support from Enterprises from the Perspective of Subsidies. Sustainability 2025, 17, 6873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Qiu, Y. The Impact of Contract Farming on Farmers’ Agricultural Production: Analysis Based on Survey Data of 1041 Farmers in Three Provinces (Regions). Chin. Rural Econ. 2013, 4, 48–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, Y.; Bi, W.; Zhang, Y. Can Contract Farming Improve Farmers’ Technical Efficiency and Income? Evidence from Beef Cattle Farmers in China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2023, 7, 1179423. [Google Scholar]

- Hou, J.; Ying, R.Y.; Zhou, L. Does Contract Farming Effectively Improve Farmers’ income? An Empirical Research Based on Quantile Regression. J. Nanjing Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2018, 18, 122–132+156. [Google Scholar]

- Barik, P.; Bedamatta, R. Is Contract Farming Fair For Smallholder Farmers? A Case Study From India. J. Contemp. Asia 2025, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, J. The Measurement and Evolution Trends of the Circulation Efficiency of Agricultural Products in China: An Empirical Analysis Based on the Panel Data from 1998 to 2009. China Bus. Mark. 2011, 25, 21–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, X.X.; Huang, F.H. Measurement and Determining Factors of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency in China: 2000–2009. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2011, 2, 76–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, M.; Qi, C.J. Constraints and Breakthrough Points of the Efficiency of Agricultural Products Circulation in China. China Bus. Mark. 2012, 26, 43–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Qi, C.; Jiang, P.; Xiang, S. The Impact of Blockchain Application on the Qualification Rate and Circulation Efficiency of Agricultural Products: A Simulation Analysis with Agent-Based Modelling. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 7686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Zhang, Y.D.; Xue, J.H.; Cao, Y.Y. Exploring the Path to the Sustainable Development of Cold Chain Logistics for Fresh Agricultural Products in China. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 2024, 108, 107610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Guo, G. The Influence of Large-Scale Agricultural Land Management on the Modernization of Agricultural Product Circulation: Based on Field Investigation and Empirical Study. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13967. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruml, A.; Ragasa, C.; Qaim, M. Contract Farming, Contract Design and Smallholder Livelihoods. Aust. J. Agric. Resour. Econ. 2022, 66, 24–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xu, L. The Integration and Cultivation of the Fruit Industry Chain under the Leadership of the Leading Enterprise of Circulation Type: Based on the Theory and Practice of Peach Industry. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 8, 77–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xie, G.Y. Transportation Infrastructure, Scale of Circulation Organization and Market Segmentation of Agricultural Products Circulation. J. Beijing Technol. Bus. Univ. (Soc. Sci.) 2019, 34, 28–40. [Google Scholar]

- Qou, R.; Tan, X.Y. On the Analysis Framework of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency. China Bus. Mark. 2008, 5, 12–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Z.L. Study on the Circulation Efficiency and Influencing Factors of Chinese Sweet Melon. Doctoral Dissertation, Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences, Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.F.; Xu, S.H.; Qian, J.F. International Experience in Building a Modern Circulation System for Agricultural Products and Its Implications for China. China Bus. Mark. 2025, 39, 22–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lou, J.C.; Liu, Z. Empirical Analysis of the Impact of Human Capital on Agricultural Economy. Stat. Decis. 2020, 36, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.B. Research on Human Capital, Social Capital, and Farmers’ Order Fulfillment Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Guo, H.D. Research on Order Arrangement and Fulfillment Mechanism between Agricultural Leading Enterprises and Farmers: An Analysis Based on the Behavior of Enterprises and Farmers. Doctoral Dissertation, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, J. Research on the Development of Farmers’ Professional Cooperative Organizations in the Circulation Field. Issues Agric. Econ. 2001, 11, 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, D.K. Causes for the Irrational Prosperity in the Real Estate Market and the Influence of That. China Bus. Mark. 2010, 24, 31–34+80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.Q.; Chen, Y.; Zhou, Q.L.; Ying, H.D. Impacts of COVID-19 on Rural and Agricultural Development in 2020 and Its Countermeasures. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 3, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Si, W.; Zhang, Y.M.; Fan, S.G. How to Ensure Food and Nutrition Security under the COVID-19 Epidemic: A Global Perspective. Issues Agric. Econ. 2020, 3, 11–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Shi, X.Y.; Zhou, H. Influence Path of Agricultural Mechanization on Total Factor Productivity Growth in Planting Industry. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2020, 10, 87–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, J.; Wang, X.D. Research on the Discrimination against Weak Farmers in Contract Farming. Soc. Sci. J. 2011, 3, 103–106. [Google Scholar]

- Peng, J.Q.; Wu, H.T.; Wang, W. The Influence of Agricultural Mechaniztion Level on Farmers’ Production of Staple Food. Chin. J. Agric. Resour. Reg. Plan. 2021, 42, 51–59. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, L.S.; Huang, S.; Li, X.B. Research on the Impact of Agricultural Mechanization on Farmers’ Income: An Empirical Analysis Based on System GMM Model and Mediation Effect Model. Rural Econ. 2021, 6, 41–49. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. Risk Management of Contract Farming from the Perspective of Farmers’ Professional Cooperatives. Hubei Soc. Sci. 2011, 9, 93–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J.; Qi, C.J. Game Analysis of Leading Enterprises and Farmers in Contract Agriculture in China. J. Agrotech. Econ. 2007, 5, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, J.J.; Xu, X.G. Market Structure and Performance Analysis of Contract Farming. Issues Agric. Econ. 2008, 3, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Q. Capital Endowment, Risk Perception, and Farmers’ Performance Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- He, Q.J. Market Distance, Rransaction Prices, and Farmers’ Performance Behavior. Master’s Thesis, Anhui Agricultural University, Hefei, China, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, T.Q.; Li, B.; Deng, H. The Reform of Three Rights Division of Farm Land and the Growth of County Agricultural Economy. J. Huazhong Agric. Univ. (Soc. Sci. Ed.) 2021, 5, 147–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Z.X.; Liang, B. Research on the Driving Effect of Agricultural Leading Enterprises on Farmers in Guangdong Province: Empirical Analysis Based on Cross Sectional Data from 21 Cities. Spec. Zone Econ. 2009, 6, 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, H.; Liu, B.; Yu, Y.Q.; Peng, L.L.; Chi, Z.X. Can the enterprise-farmer interest linkage improve the leading behavior performance of agricultural leading enterprises? Theoretical logic and empirical evidence. J. China Agric. Univ. 2025, 30, 347–362. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, W.H.; Hu, Y.K. The Temporal Changes and Regional Differences in the Competitiveness of China’s Agricultural Product Circulation System. Res. Financ. Econ. Issues 2016, 11, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, Y.L.; He, W.L.; Huang, Y.M.; Zhu, H.L. Study on Regional Differences of Agriculture Mechanization Development in China. J. Northwest A F Univ. (Nat. Sci. Ed.) 2011, 39, 210–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.J. Empirical Study on Regional Differences in Agricultural Modernization in China. Master’s Thesis, Liaoning University, Shenyang, China, 2021. [Google Scholar]

| Primary Indicator | Secondary Index | Weight | Tertiary Indicators | Weight |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business flow efficiency of agricultural products | Trading speed index | 0.0428 | Inventory turnover rate of agricultural products circulation industry | 0.0023 |

| Inventory rate of agricultural products circulation industry | 0.0209 | |||

| Total asset turnover rate of agricultural products circulation industry | 0.0196 | |||

| Business flow scale index | 0.095 | Concentration of agricultural products retail industry | 0.0186 | |

| Concentration of wholesale and retail agricultural products | 0.0250 | |||

| Wholesale and retail coefficient of agricultural products | 0.0514 | |||

| Business flow model reform index | 0.1357 | Proportion of e-commerce transactions of agricultural products | 0.0522 | |

| Development level of chain operation of agricultural products circulation industry | 0.0667 | |||

| Development level of digital payment for agricultural products | 0.0168 | |||

| Business flow benefit index | 0.067 | Profit margin of wholesale and retail agricultural products | 0.0244 | |

| Sales of agricultural products per unit business area | 0.0345 | |||

| Purchase and sales rate of agricultural products retail industry | 0.0081 | |||

| Information flow efficiency of agricultural products | Information source index (information flow infrastructure) | 0.1515 | Number of computers per rural household | 0.0160 |

| Development level of information flow facilities for agricultural products | 0.1066 | |||

| Rural per capita information access level | 0.0289 | |||

| Information channel index (information resource development) | 0.1809 | Contribution of information industry to national economy | 0.0719 | |

| Human resource level of agricultural product information flow | 0.0857 | |||

| Information industry drives the flexibility of circulation industry | 0.0233 | |||

| Information accommodation index (utilization of information resources) | 0.0746 | Development level of rural information service | 0.0102 | |

| Per capita telecom business volume of rural residents | 0.0516 | |||

| Per capita transportation and communication expenditure of rural residents | 0.0128 | |||

| Logistics efficiency of agricultural products | Logistics labor level | 0.0998 | Professional employees of agricultural products logistics (10,000 people) | 0.0207 |

| Local transportation infrastructure investment (100 million CNY) | 0.0791 | |||

| Logistics infrastructure level | 0.1275 | Fixed asset investment in agricultural products logistics (100 million CNY) | 0.0298 | |

| Density of grade highway network (km/km2) | 0.0977 | |||

| Logistics development level | 0.0251 | Added value of agricultural products logistics (100 million CNY) | 0.0251 |

| Type | Symbol | Definition | Data Source (2015–2022) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Explained variable | Contract farming coverage rate (cfc) | Proportion of contracted agricultural output value to total agricultural output value | China Rural Statistical Yearbook, Bloomberg database |

| Core explanatory variables | Comprehensive index of agricultural product circulation efficiency (apce) | Calculate through entropy method | Refer to Table 1 for entropy method calculation |

| Information flow efficiency index (info) | |||

| Business flow efficiency index (com) | |||

| Logistics efficiency index (logi) | |||

| Control variables | Agricultural mechanization level (tec) | Total power of agricultural machinery | China Statistical Yearbook |

| Human capital level (edu) | Average education years of rural labor force | China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook | |

| Scale of cultivation (lead) | Number of leading national agricultural enterprises | CCAD | |

| Level of mechanization (org) | Number of farmer professional cooperatives | Annual Report on China’s Business Management Statistics; Annual Report on China’s Rural Cooperative Economy Statistics; Annual Report on China’s Rural Policy and Reform Statistics |

| Variable | Average | Standard Deviation | Minimum Value | Maximum Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| lncfc | 2.972 | 0.295 | 2.079 | 3.555 |

| lnapce | −2.001 | 0.316 | −2.659 | −0.906 |

| lntec | 7.688 | 1.147 | 4.543 | 9.499 |

| edu | 7.91 | 0.637 | 5.878 | 10.115 |

| lead | 37.567 | 15.399 | 12 | 89 |

| lnorg | 10.655 | 1.006 | 7.795 | 12.34 |

| Variables | lncfc | lnapce | lntec | edu | lead | lnorg |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| lncfc | 1.000 | |||||

| lnapce | 0.433 *** | 1.000 | ||||

| (0.000) | ||||||

| lntec | −0.296 *** | −0.290 *** | 1.000 | |||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | |||||

| edu | 0.489 *** | 0.434 *** | −0.315 *** | 1.000 | ||

| (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.000) | ||||

| lead | 0.072 | 0.160 ** | 0.636 *** | 0.041 | 1.000 | |

| (0.269) | (0.013) | (0.000) | (0.527) | |||

| lnorg | −0.149 ** | −0.268 *** | 0.915 *** | −0.207 *** | 0.623 *** | 1.000 |

| (0.021) | (0.000) | (0.000) | (0.001) | (0.000) |

| Variables | VIF | 1/VIF |

|---|---|---|

| lntec | 7.641 | 0.131 |

| lnorg | 6.594 | 0.152 |

| lead | 2.255 | 0.443 |

| lnapce | 1.53 | 0.654 |

| edu | 1.402 | 0.713 |

| Mean VIF | 3.884 |

| Variables | Mixed Effect Model (OLS) | Random Effect Model (RE) | Fixed Effect Model (FE) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model (1) | Model (2) | Model (3) | Model (4) | |

| lnapce | 0.210 *** | 0.379 *** | 0.281 *** | 0.196 ** |

| (3.496) | (4.948) | (4.073) | (2.17) | |

| lntec | −0.200 *** | −0.234 *** | 0.517 *** | 0.398 *** |

| (−5.515) | (−4.009) | (6.421) | (3.52) | |

| edu | 0.122 *** | 0.239 *** | 0.236 *** | 0.001 |

| (4.255) | (5.610) | (5.880) | (0.02) | |

| lead | 0.003 ** | −0.009 *** | −0.007 * | −0.002 |

| (2.101) | (−3.368) | (−1.776) | (−0.48) | |

| lnorg | 0.169 *** | 0.438 *** | 0.802 *** | 0.579 *** |

| (4.396) | (8.320) | (15.268) | (9.14) | |

| _cons | 2.052 *** | −0.696 | −10.568 *** | −5.941 *** |

| (6.168) | (−1.373) | (−12.381) | (−4.58) | |

| N | 240 | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| R2 | 0.380 | - | 0.747 | 0.847 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.367 | - | 0.705 | 0.839 |

| F | 28.697 | - | 121.175 | 120.029 |

| Individual effect | NO | NO | YES | YES |

| Time effect | NO | YES | NO | YES |

| Number of id | 30 | 30 | 30 | 30 |

| Variables | Benchmark Regression | Regression with Lag Variables | SDM-LR-Direct |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnapce | 0.196 ** | 0.246 ** | 0.222 *** |

| (2.17) | (2.457) | (3.44) | |

| lntec | 0.398 *** | 0.608 *** | 0.358 *** |

| (3.52) | (3.080) | (5.03) | |

| edu | 0.001 | 0.024 | 0.018 |

| (0.02) | (0.405) | (0.46) | |

| lead | −0.002 | −0.001 | −0.004 |

| (−0.48) | (−0.156) | (−1.72) | |

| lnorg | 0.579 *** | 0.567 *** | 0.563 *** |

| (9.14) | (6.775) | (11.68) | |

| _cons | −5.941 *** | −7.604 *** | - |

| (−4.58) | (−4.923) | - | |

| N | 240 | 210 | 240 |

| R2 | 0.847 | 0.834 | - |

| Adj. R2 | 0.839 | 0.825 | - |

| F | 120.029 | 15.582 | - |

| Logistics Efficiency Indicator 1 | Logistics Efficiency Indicator 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Total Amount of Local Postal Services (Ten Thousand CNY) | Local Transportation Expenditure (Ten Thousand CNY) | |

| Regions with low leading agricultural enterprise coverage | 10.905 | 11.642 |

| Regions with high leading agricultural enterprise coverage | 11.469 | 11.935 |

| Diff Value | −0.564 *** | −0.294 *** |

| T statistic | −8.922 | −7.343 |

| Sample size of regions with low stock of leading agricultural enterprises | 1212 | 1591 |

| Total sample size | 2018 | 2507 |

| Variables | lncfc | lncfc | lncfc |

|---|---|---|---|

| lncom | 0.116 * | ||

| (0.068) | |||

| lninfo | 0.079 * | ||

| (0.043) | |||

| lnlogi | 0.623 *** | ||

| (0.136) | |||

| lntec | 0.508 *** | 0.479 *** | 0.360 *** |

| (0.148) | (0.143) | (0.130) | |

| edu | 0.201 *** | 0.249 *** | 0.163 *** |

| (0.050) | (0.059) | (0.044) | |

| lead | −0.010 * | −0.009 | −0.008 |

| (0.005) | (0.006) | (0.005) | |

| lnorg | 0.857 *** | 0.811 *** | 0.706 *** |

| (0.076) | (0.073) | (0.083) | |

| _cons | −11.055 *** | −10.811 *** | −7.188 *** |

| (1.476) | (1.497) | (1.549) | |

| N | 240 | 240 | 240 |

| adj. R2 | 0.726 | 0.727 | 0.799 |

| Year | Overall Gini Coefficient | Within the Region | Between Regions | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| East | Central | West | East–Central | East–West | Central–West | ||

| 2015 | 0.185 | 0.163 | 0.096 | 0.194 | 0.176 | 0.189 | 0.167 |

| 2016 | 0.184 | 0.165 | 0.104 | 0.181 | 0.181 | 0.188 | 0.159 |

| 2017 | 0.179 | 0.163 | 0.082 | 0.170 | 0.178 | 0.183 | 0.146 |

| 2018 | 0.179 | 0.189 | 0.083 | 0.128 | 0.198 | 0.185 | 0.117 |

| 2019 | 0.164 | 0.171 | 0.089 | 0.114 | 0.182 | 0.168 | 0.110 |

| 2020 | 0.136 | 0.126 | 0.075 | 0.120 | 0.138 | 0.139 | 0.108 |

| 2021 | 0.188 | 0.184 | 0.103 | 0.159 | 0.190 | 0.198 | 0.141 |

| 2022 | 0.187 | 0.182 | 0.104 | 0.158 | 0.188 | 0.199 | 0.139 |

| Overall | Eastern Region | Central and Western Regions | |

|---|---|---|---|

| lnapce | 0.196 ** | 0.047 | 0.246 ** |

| (2.168) | (0.425) | (2.737) | |

| lntec | 0.398 *** | 0.143 | 0.303 *** |

| (3.524) | (1.089) | (3.055) | |

| edu | 0.001 | −0.107 | −0.002 |

| (0.021) | (−1.558) | (−0.027) | |

| lead | −0.002 | −0.011 | −0.008 |

| (−0.476) | (−1.191) | (−1.480) | |

| lnorg | 0.579 *** | 0.068 | 0.555 *** |

| (9.142) | (0.582) | (4.803) | |

| _cons | −5.941 *** | 2.745 | −4.943 *** |

| (−4.575) | (1.388) | (−3.642) | |

| N | 240 | 88 | 152 |

| R2 | 0.847 | 0.638 | 0.914 |

| Adj. R2 | 0.839 | 0.580 | 0.907 |

| F | 19.618 | 34.479 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Shen, Z.; Liu, T. Impact of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency on Contract Farming Coverage and Regional Differences: Evidence from China. Sustainability 2025, 17, 10792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310792

Shen Z, Liu T. Impact of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency on Contract Farming Coverage and Regional Differences: Evidence from China. Sustainability. 2025; 17(23):10792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310792

Chicago/Turabian StyleShen, Zhengyue, and Tingting Liu. 2025. "Impact of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency on Contract Farming Coverage and Regional Differences: Evidence from China" Sustainability 17, no. 23: 10792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310792

APA StyleShen, Z., & Liu, T. (2025). Impact of Agricultural Product Circulation Efficiency on Contract Farming Coverage and Regional Differences: Evidence from China. Sustainability, 17(23), 10792. https://doi.org/10.3390/su172310792