Among the technical challenges posed by wind farms, fault location stands out due to the complexity of their configurations, which include aerial and buried cables, as well as the distributed nature of the generation units. As wind farms grow in size and connect to increasingly complex grid structures, traditional fault location methods may become less effective or computationally impractical. These limitations have motivated the exploration of advanced techniques capable of handling complex circuit configurations and adapting to the dynamic behavior of such systems. In this context, there is a lack of methods capable of adequately locating faults in the collecting circuits of wind farms. Thus, the following section presents a review of the main contributions found in the literature regarding fault location methods in electrical grids.

1.1. Literature Review

The scientific literature proposes various methodologies to overcome the challenges inherent in locating faults, such as grid complexity, the variability of energy sources, and the presence of components such as wind turbines and long-distance transmission lines. Existing approaches have been primarily classified into artificial intelligence (AI)-based methods and traditional methods [

3,

4].

AI-based methods, such as ref. [

5], have proposed an optimized GWO-WELM (Grey Wolf Optimization—Weighted Extreme Learning Machine) model for fault diagnosis using simulated phasor measurement unit (PMU) data in a 9-bus IEEE system. The applied method has demonstrated high accuracy in fault classification (99.83%) and localization (95.48%). However, the specific application in wind power generation systems, which present specific dynamic and noise characteristics, has required additional adaptations and validations. By obtaining data from PMUs, the model has been analyzed with measurement data from real-life scenarios, improving the application of the proposal.

The method proposed in ref. [

6] for fault detection and classification utilizes convolutional neural networks (CNNs). The authors have demonstrated significant potential in their application. The execution of this method achieved a classification accuracy of 100% and an ideal response time of 0.047 s for a 9-bus IEEE test system. However, in larger and more complex wind power systems, which present different types of deficiencies and operating conditions, a more thorough evaluation of the model’s robustness and generalizability has been required.

Following the line of neural network–based approaches, the method presented in ref. [

7] employs artificial neural networks (ANNs) for short-circuit fault detection and classification. The technique achieved high accuracy in locating faults by analyzing phasor quantities measured at the transmission line’s terminals. Nevertheless, the implementation of ANNs required considerable computational resources, leading to relatively long processing times. This drawback becomes more pronounced in large-scale networks, where the volume of measurement data grows significantly [

8].

In ref. [

9], a method was proposed for applying AI algorithms, such as neural networks, ANN, and random forest, showing achieved good accuracy (90%) in classifying and locating faults in distribution networks with renewable generation. The authors applied the method to a 14-bus electrical distribution system adapted from the IEEE. This electrical model enabled the visualization of AI methods in wind energy systems.

The authors of ref. [

10] developed a method based on AI, including deep learning, to assist control center operators in fault location. However, the method’s effectiveness has depended on the quantity of the available training data, as well as the model’s ability to handle the diversity of faults and network configurations in wind power generation systems.

In ref. [

11], the authors introduced a fault detection and location scheme that leverages travelling-wave (TW) phenomena for multi-sectional cross-bonded export cables in offshore wind farms. The work developed detailed cable models and TW principles under realistic operating conditions, incorporating an impedance-aggregation technique that preserves the frequency characteristics of the offshore collecting circuit. Wavelet-based TW simulations were also performed to provide independent verification. The results confirmed that TW-based relays are suitable for offshore environments, supported by evidence from both simulation studies and hardware relay tests.

The authors of ref. [

12] proposed a phasor-based multi-method fault location strategy tailored to onshore wind farm collector circuits. The method uses measurements at the (CB) and selects the most accurate fault location technique depending on the fault type. It was validated through PSCAD simulations, considering diverse fault scenarios. Despite having good precision, a key limitation of the method is its difficulty in identifying the specific faulted section in collecting circuits with lateral derivations, which may result in multiple possible fault locations along different branches.

In ref. [

13], a two-stage fault-location scheme was introduced for offshore wind farm collector systems, where detection is difficult due to cables buried deep under the seabed. The first stage identifies the faulted zone using compressed sensing, enhanced through improved data measurement,

-NIM dictionary design, and an optimized CoSaMP algorithm. The second stage applies an equation to find asymmetric faults within the identified segment. Despite its accuracy gains, the method requires measurements at multiple nodes of the collector grid, rather than only at the circuit breaker (CB), which limits its practicality for wind farms instrumented solely at the CB. Additionally, its applicability to branched collector circuits is unclear, often resulting in multiple possible fault locations.

In ref. [

14], the authors developed a synthetic-image strategy for detecting defects in transmission lines. Using information collected by the Fault Patrol Transmission Line Inspection Robot (FPTLIR), they generated the Synthetic Defect Component Dataset (SDFC), which served as training data for an enhanced YOLOv5 model. This customized version, named CSH-YOLOv5, incorporates both the Convolutional Block Attention Module (CBAM) and the SimCSPSPPF module to enhance feature extraction and detection precision. The study demonstrates that this framework can significantly strengthen automated fault detection in transmission lines and provides useful insights for practical applications in the power transmission field.

In ref. [

15], a fault-classification approach was proposed using a Fault Identification Matrix (FIM) constructed from changes in the component current samples and the sign of their rates of change (

and

) measured at both terminals of a transmission line. The technique also relied on the second-order harmonic component of the line currents—recomputed via the Clarke transform—to distinguish among fault types. The authors evaluated the method through extensive PSCAD/EMTDC v5.0.2 simulations covering all short-circuit categories and several atypical operating scenarios. Across the full set of tests, the approach consistently identified and classified faults within a single cycle, demonstrating rapid response, robustness, and minimal dependence on network parameters.

The work ref. [

16] presents a fault location approach that relies on optimization techniques for application in series-compensated transmission lines. This algorithm estimates the position of the fault by minimizing the error between measured post-fault phasors and those computed from a grid model, utilizing a dynamic differential evolution strategy. One of the main strengths of this method is that its performance does not depend on the particular configuration, impedance values, or location of the series-compensation equipment. Its effectiveness was demonstrated using a 500-kV double-circuit transmission line modeled in ATP/EMTP [

17], where the approach proved robust under various compensation arrangements. However, although several studies have explored optimization-based methods in power systems, recent findings suggest that optimal placement and sizing of distributed renewable resources also play a significant role in improving network performance. In ref. [

18], for example, applied a Wild Horse Optimizer-based strategy and reported substantial reductions in active power losses and enhanced voltage regulation when photovoltaic and wind-based distributed generation were jointly optimized instead of being deployed independently. This further reinforces the relevance of optimization frameworks in modern power systems while also highlighting the shifting focus from traditional transmission protection toward challenges associated with renewable-dominated and inverter-based distribution architectures.

In ref. [

19], the authors presented a fault-location technique grounded in electromagnetic time-reversal (EMTR) theory, introducing a criterion based on the minimum reflected energy of the fault current signal. This method evaluates how the fault current signal energy is distributed in the frequency domain by considering different ground-fault impedance values in the forward-time simulation. The corresponding time-domain response was then validated through power system computer-aided design tools, confirming the feasibility of the proposed approach.

Time-of-arrival analysis methods have been based on traveling-wave (TW) techniques, which offer high accuracy and precision. However, their effectiveness may be compromised in systems with distributed generation and scenarios with low DC filter impedance, as mentioned in ref. [

20]. Application in networks with wind power injection may require consideration of more complex wave propagation phenomena due to the presence of different energy sources.

The method proposed in ref. [

21] used TW time difference and PSO to locate faults in active distribution networks with distributed generators. Studies such as refs. [

22,

23] applied TW analysis to multiple opposite terminals, calculating the fault distance by averaging the results. Ref. [

24] proposed a technique to identify the fault location using the correlation of the initial TW arrival times.

The work [

25] proposes a travelling–wave–based protection scheme for multi-terminal HVDC transmission lines, incorporating undecimated morphological wavelet decomposition for signal processing. Detecting a fault within the protected zone, the primary relay issues a trip command to the corresponding hybrid DC circuit breakers. The scheme also provides a backup mechanism for enhanced reliability.

In ref. [

26], the authors presented an improved fault-location scheme rooted in Electromagnetic Time Reversal (EMTR). The method exploits the characteristic frequency of the travelling wave reflected from the fault to determine its position. Its performance was assessed through PSCAD simulations and controlled laboratory experiments, enabling a direct comparison with traditional EMTR techniques. The results demonstrated that the proposed approach performs especially well in complex line configurations and exhibits strong robustness when dealing with high-impedance faults (HIFs).

In ref. [

27], the authors developed a method in which a high-resolution data acquisition system captures disturbances and transient events in a designated section of a medium-voltage network. The recorded signals are subsequently analyzed using a post-processing routine based on time-reversal principles, forming the foundation of the FasTR technique for pinpointing event locations. The study demonstrated that a compact, rooftop-mounted unit can reliably identify transient faults in real-time, even in networks with complex configurations.

In ref. [

28], the authors introduced a single-ended, phasor-based fault-location (SEPHFL) framework that combines multiple independent algorithms. Using actual digital fault recorder (DFR) measurements, the method aggregates the outputs of different SEPHFL techniques to derive both precise point estimates of the fault location and broader search regions. This hybrid strategy enhanced the accuracy of the estimated distances and, simultaneously, provided practical guidance for narrowing inspection areas along the transmission line.

High-impedance faults (HIFs) are challenging to detect and locate once they exhibit a nonlinear nature and unpredictable behavior. To address this issue, ref. [

29] proposed a two-stage data-driven method that combines line-impedance estimation with fault-location comparison, achieving high identification accuracy in tests on the IEEE 33-bus system. In turn, ref. [

30] developed an automated scheme for real-time detection, classification, and localization of HIFs in 13.8 kV delta-connected distribution networks, providing utilities with timely diagnostic information to support emergency maintenance.

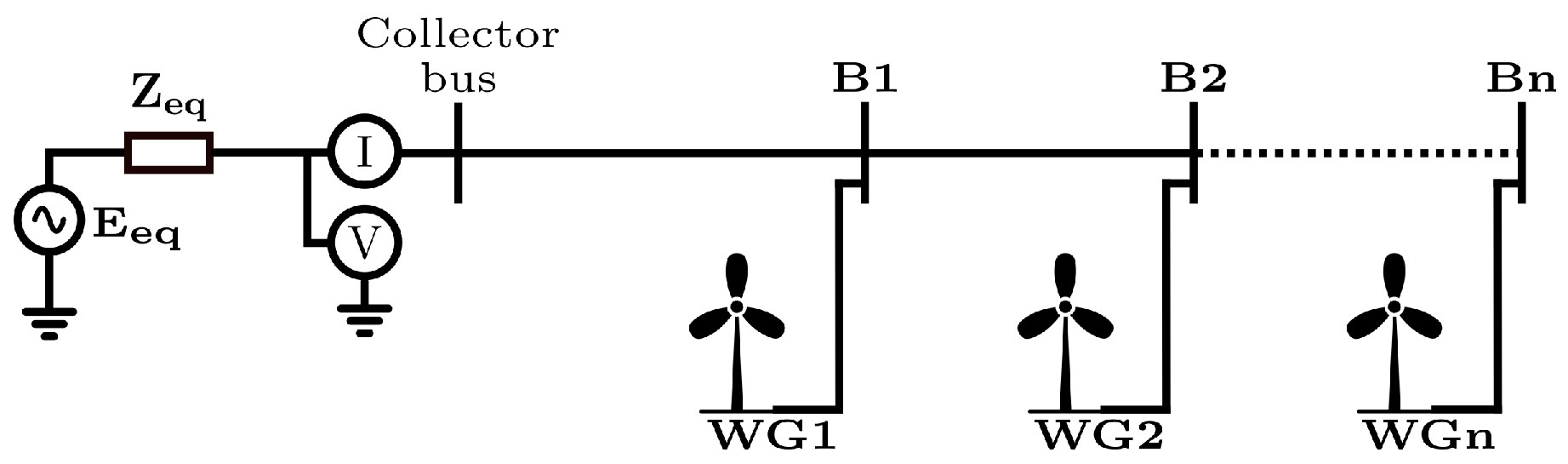

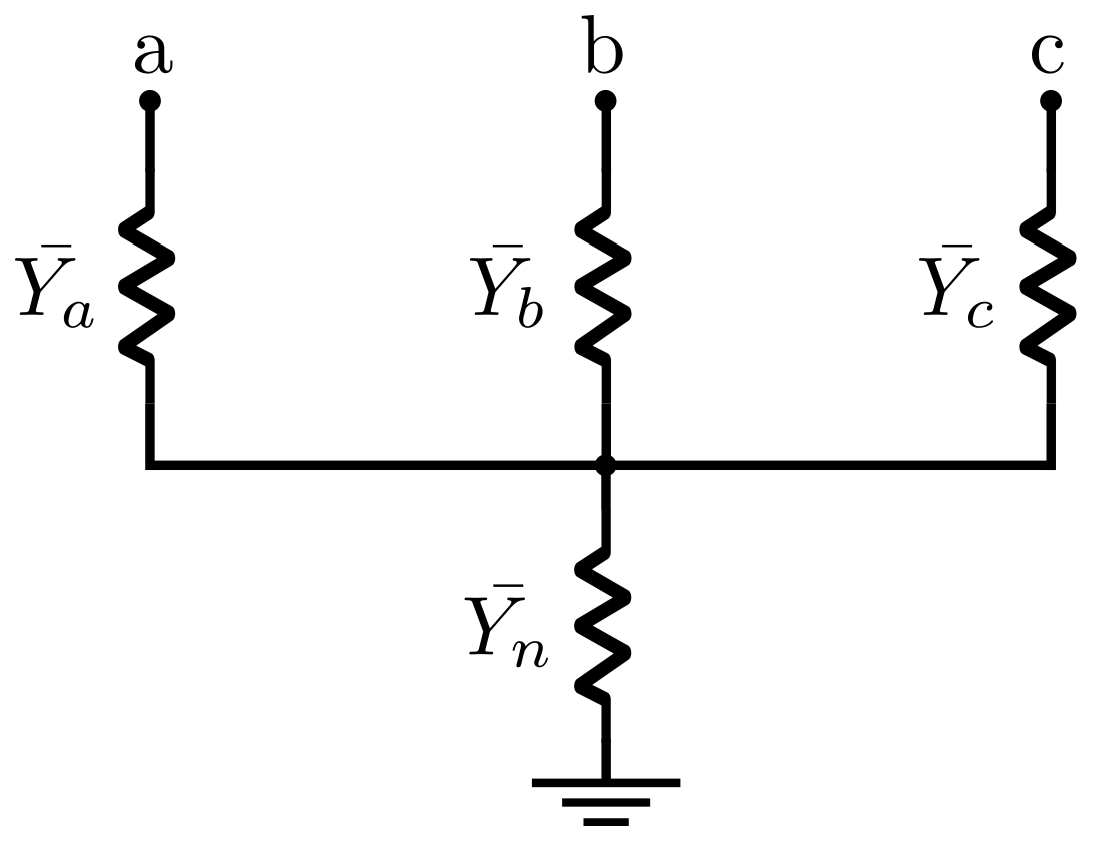

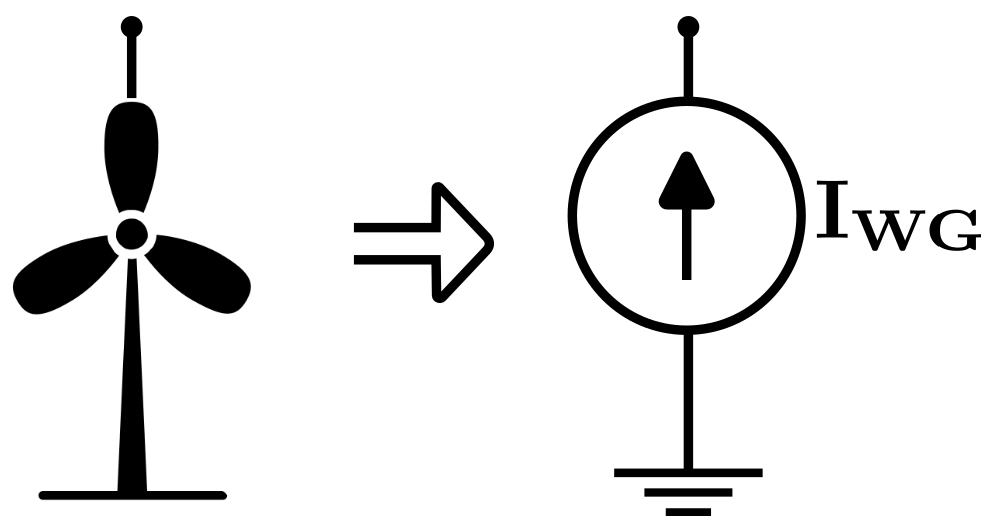

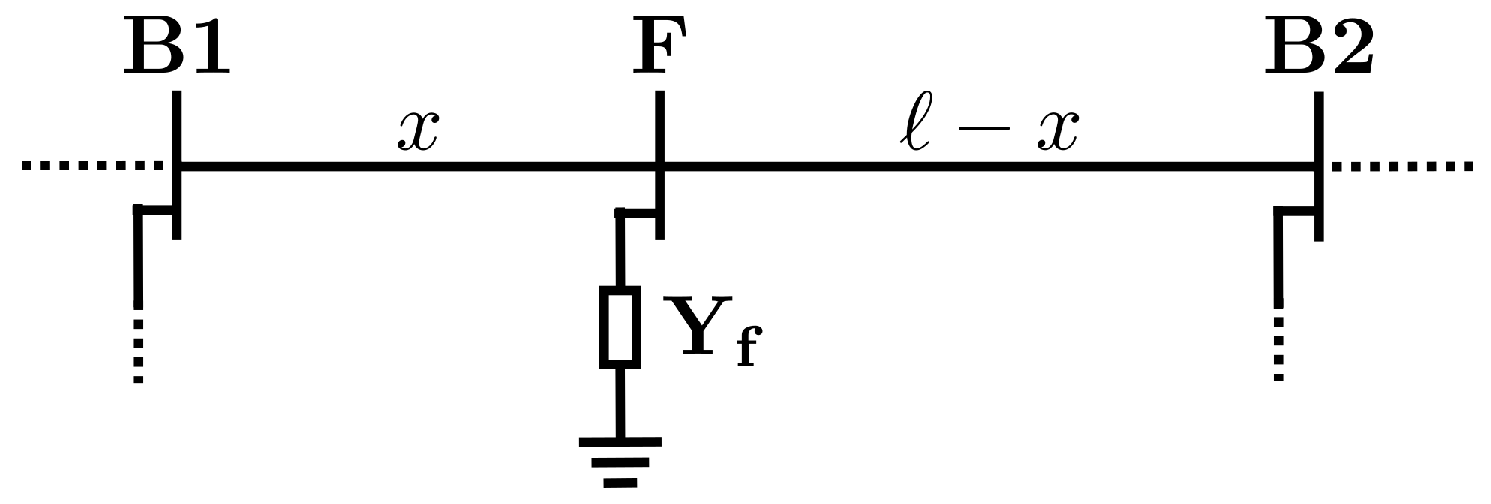

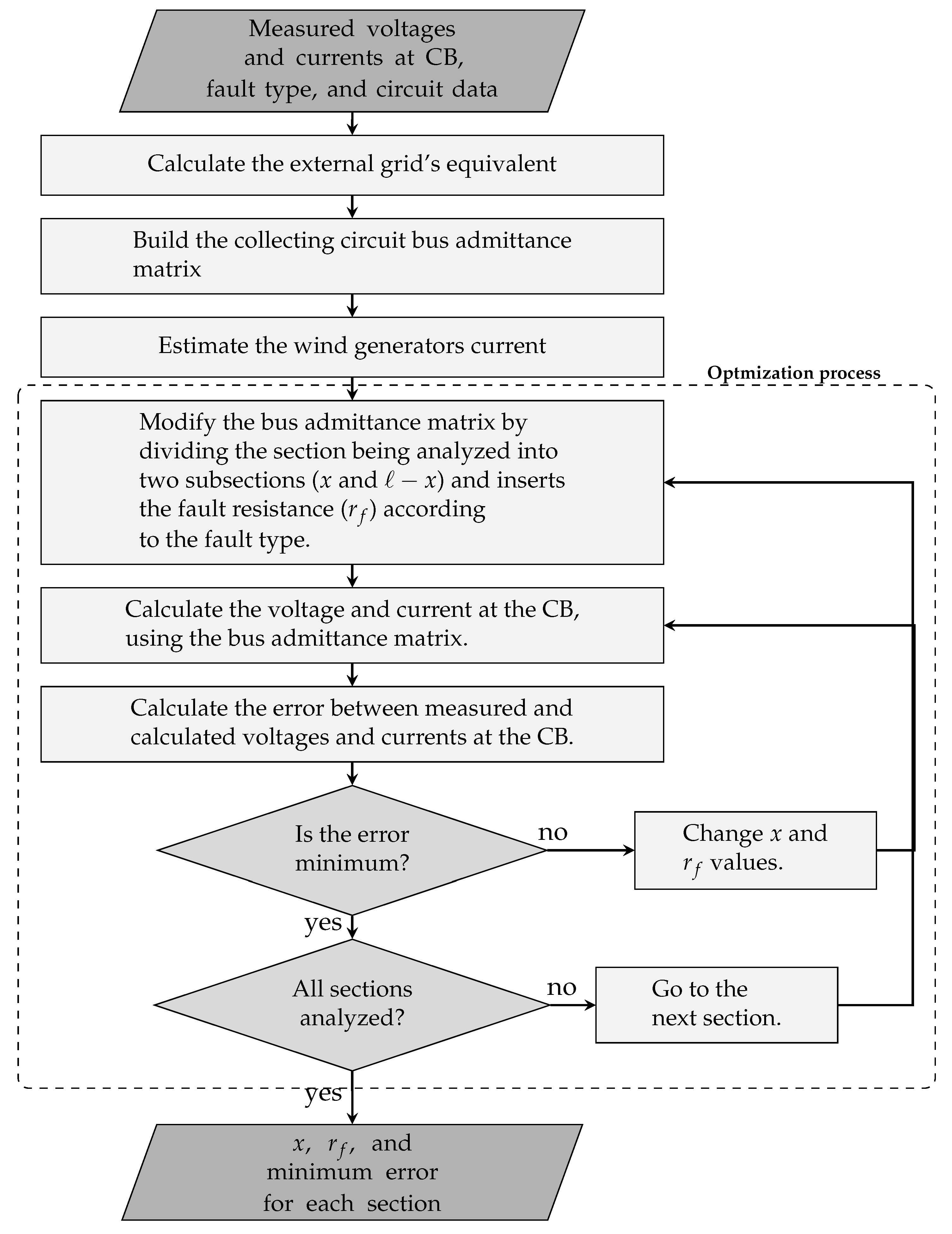

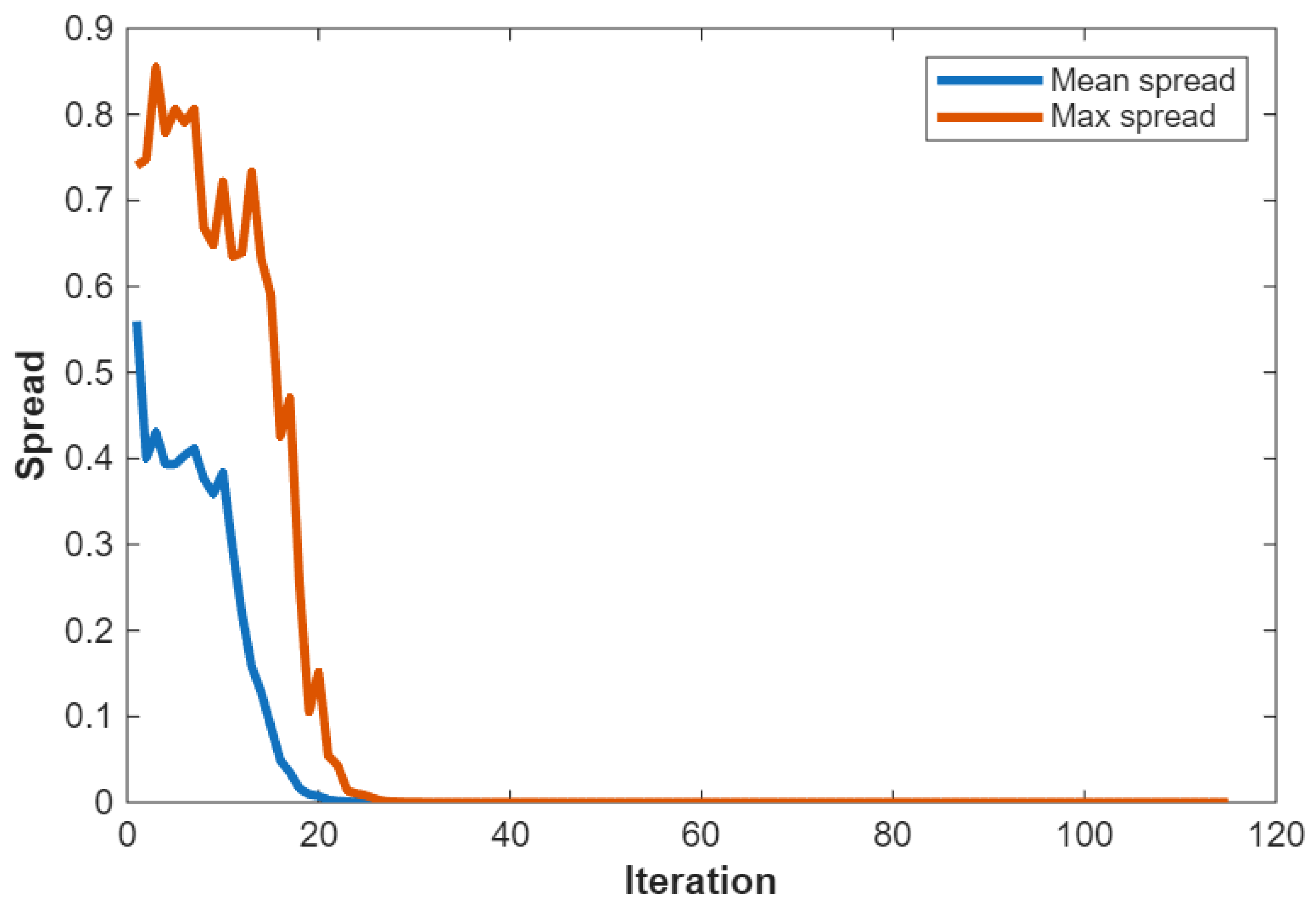

Therefore, this work proposed a fault location algorithm specifically designed for wind farms, addressing critical challenges that have not been thoroughly investigated in the existing literature. The proposed methodology uses current and voltage phasors measured only at the collecting bus (CB). These phasors were used as inputs to a PSO algorithm, which efficiently determined the faulted segment, avoiding multiple locations, and estimated the fault impedance. According to the literature surveyed, no previously published method has comprehensively addressed these fault location issues in such detail for onshore wind farms.

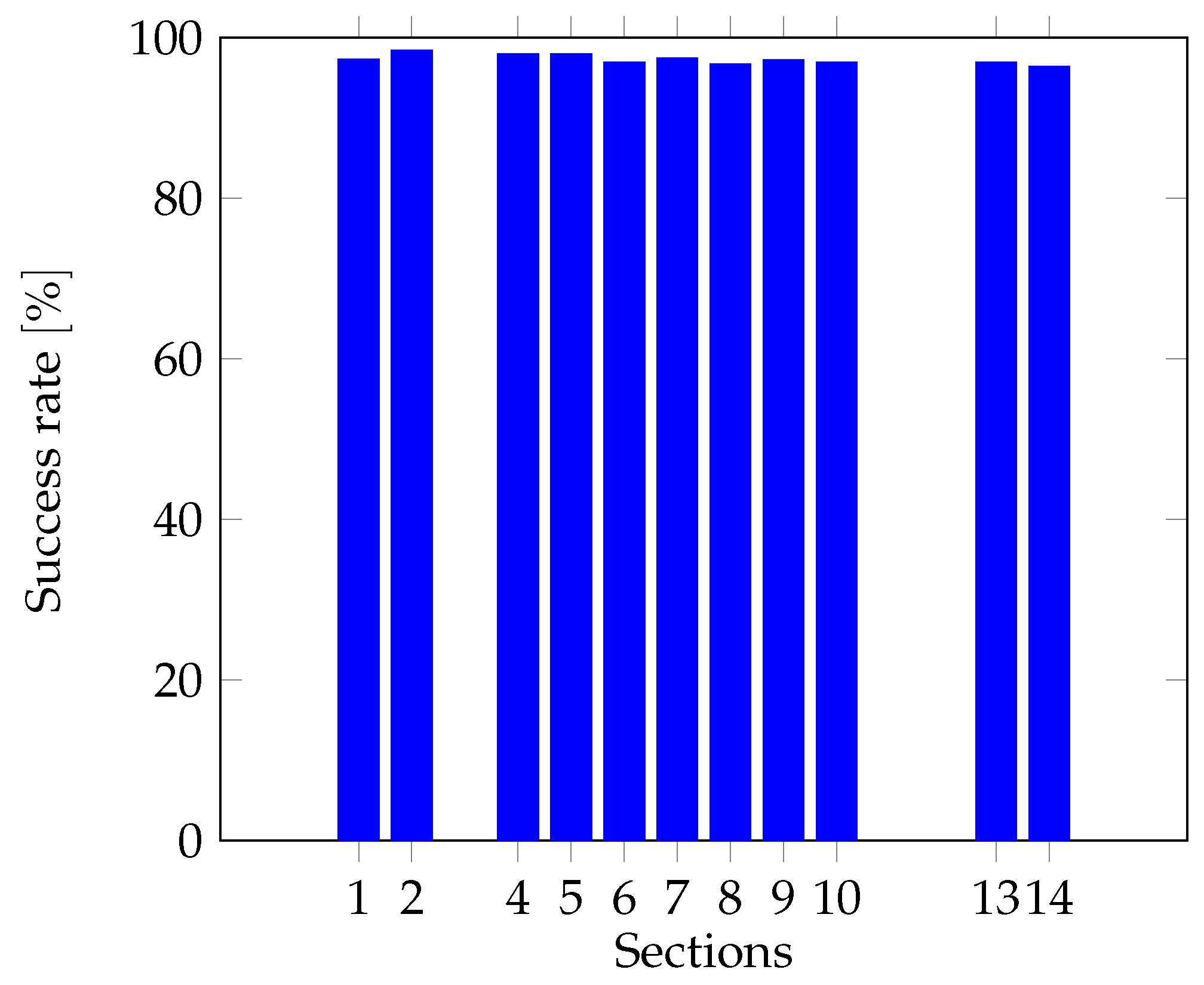

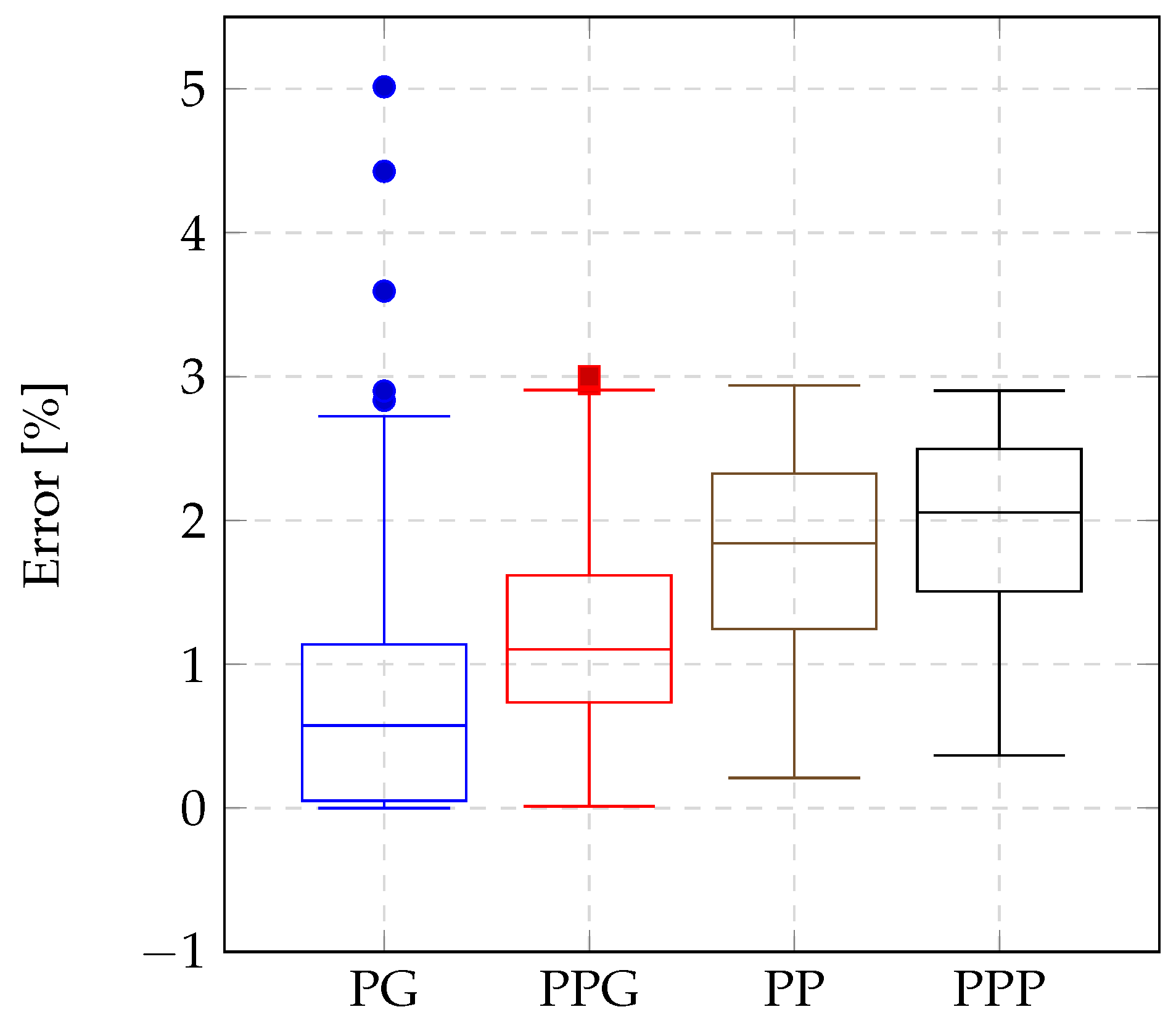

The authors validated the proposed method through 3456 fault simulations (1728 cases without errors in phasors and line section parameters and 1728 cases considering errors) conducted on a 34.5 kV wind farm circuit using the PSCAD/EMTDC v5.0.2 simulation software. The results showed that the algorithm consistently achieved high accuracy in pinpointing fault locations across all fault types, even under challenging conditions such as high-resistance faults, phasor estimation errors, and mismatches in overhead and underground line parameters.

Table 1 presents a summary of the main characteristics of the approaches reported in the literature alongside the method developed in this work.