Multi-Objective Structural Optimization of a 10 kV/1 MVar Superconducting Toroidal Air-Core Reactor

Abstract

1. Introduction

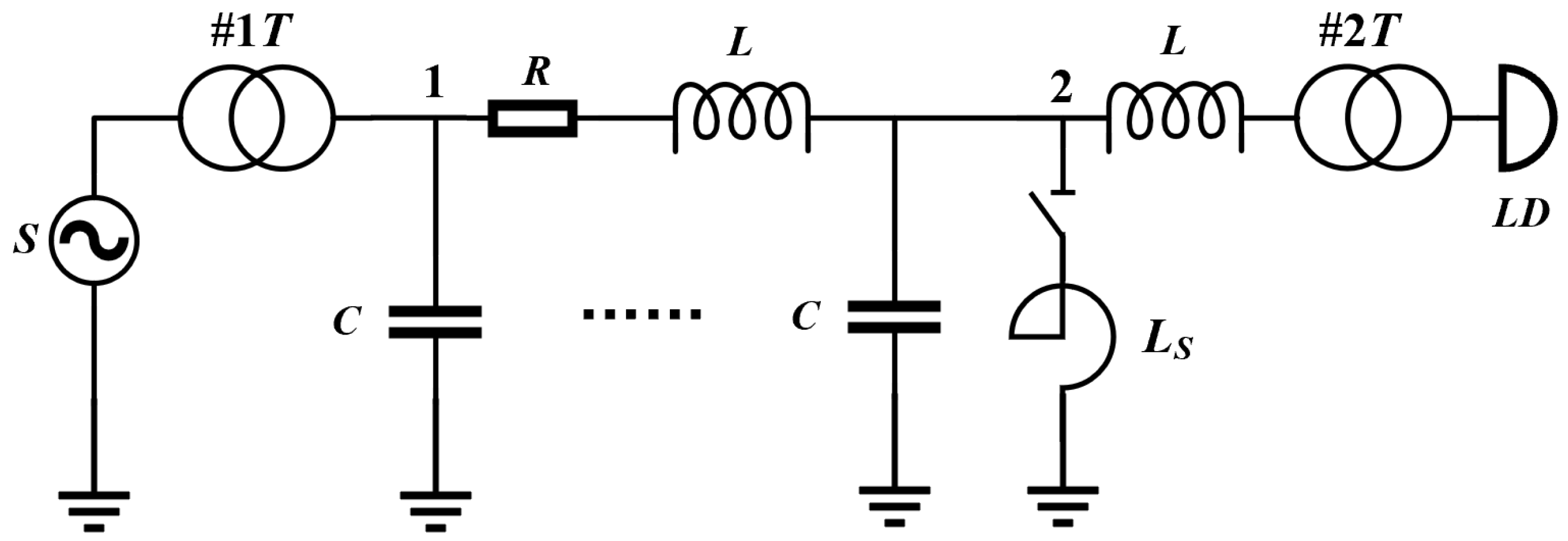

2. Operating Principle and Basic Parameter Index

2.1. Operating Principle of Shunt Reactor

2.2. Site Selection and Capacity Determination of Shunt Reactor

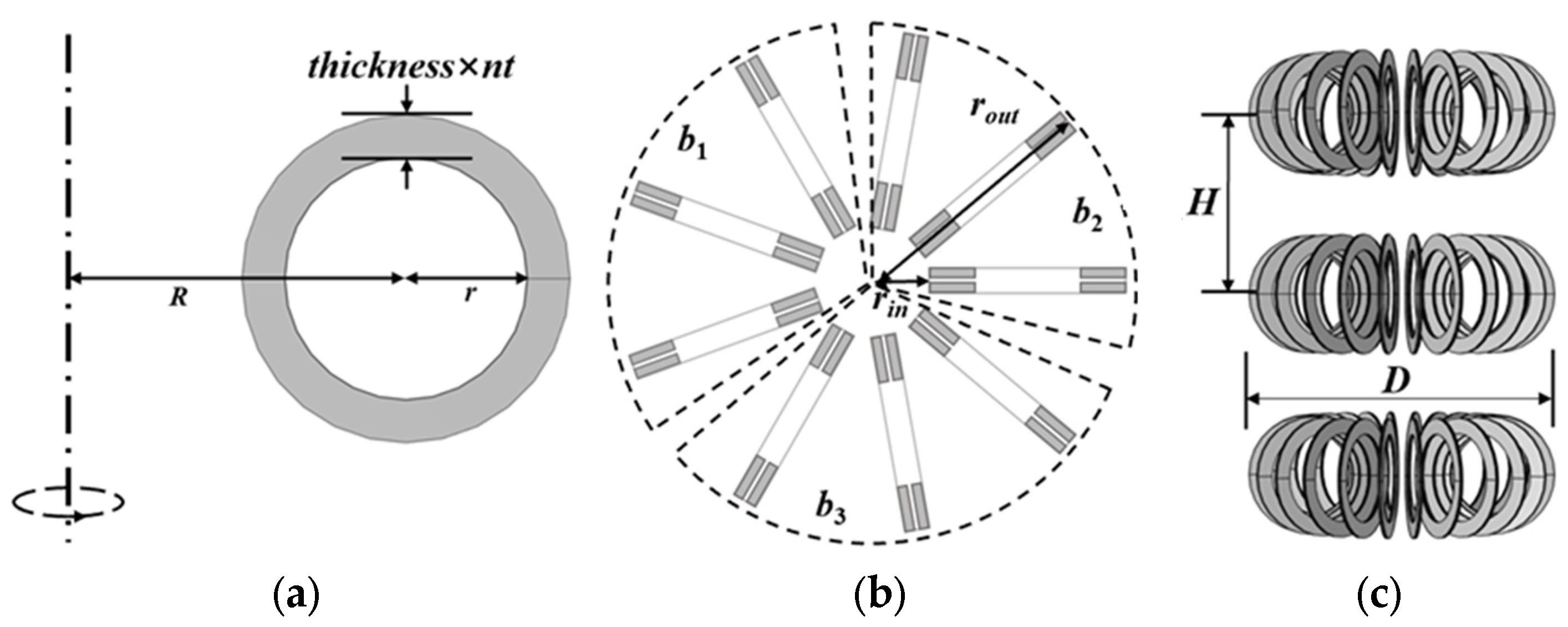

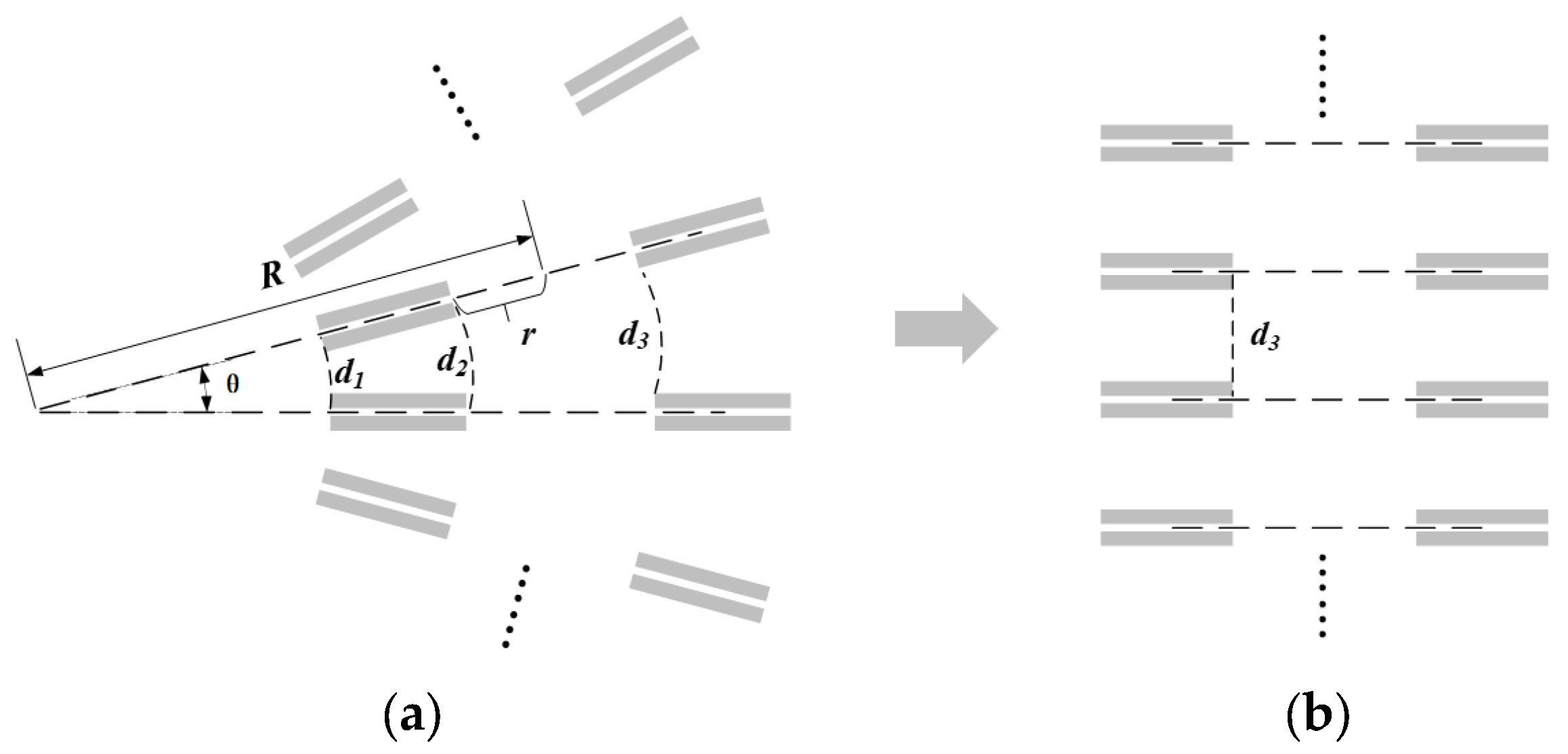

2.3. Basic Structure of the HTS Toroidal Air-Core Reactor

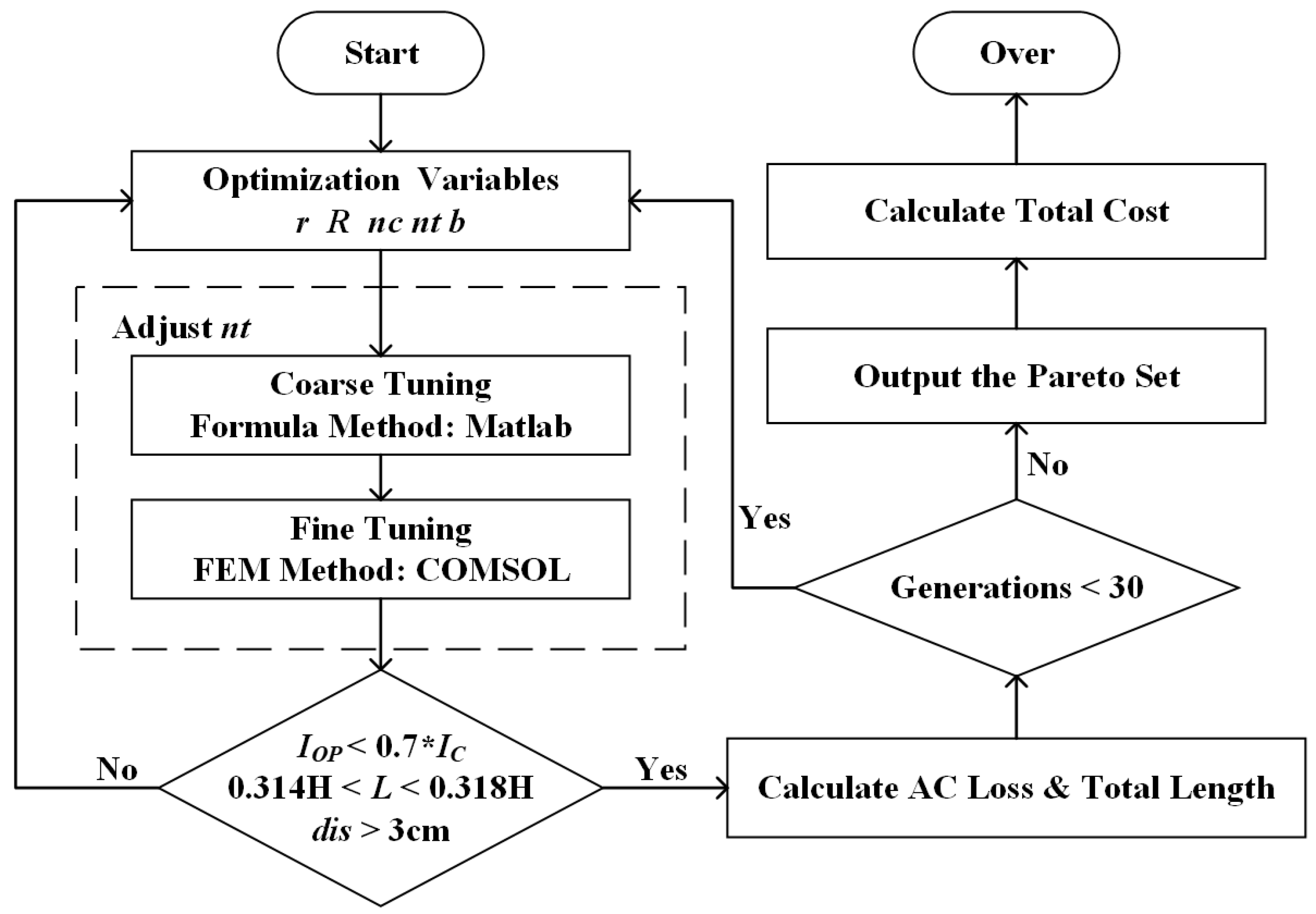

3. Optimization Method and Procedure

3.1. Objective Function and Optimization Constraint

3.2. Procedure of Design Optimization

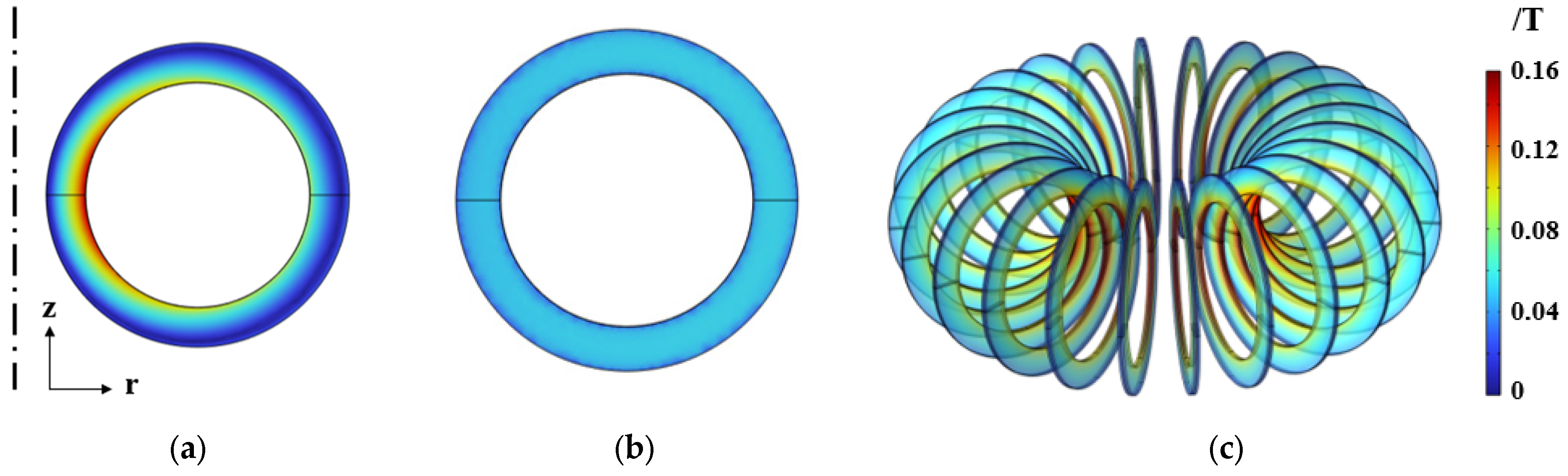

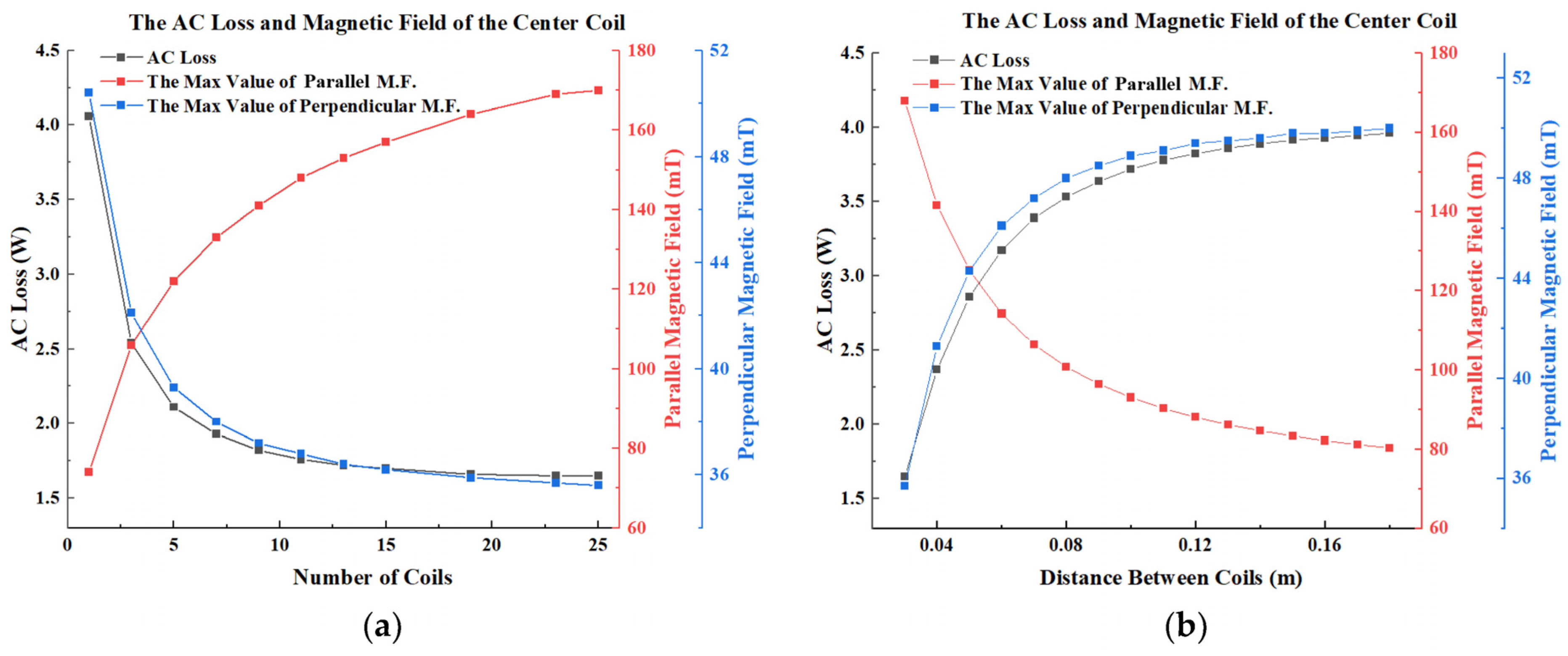

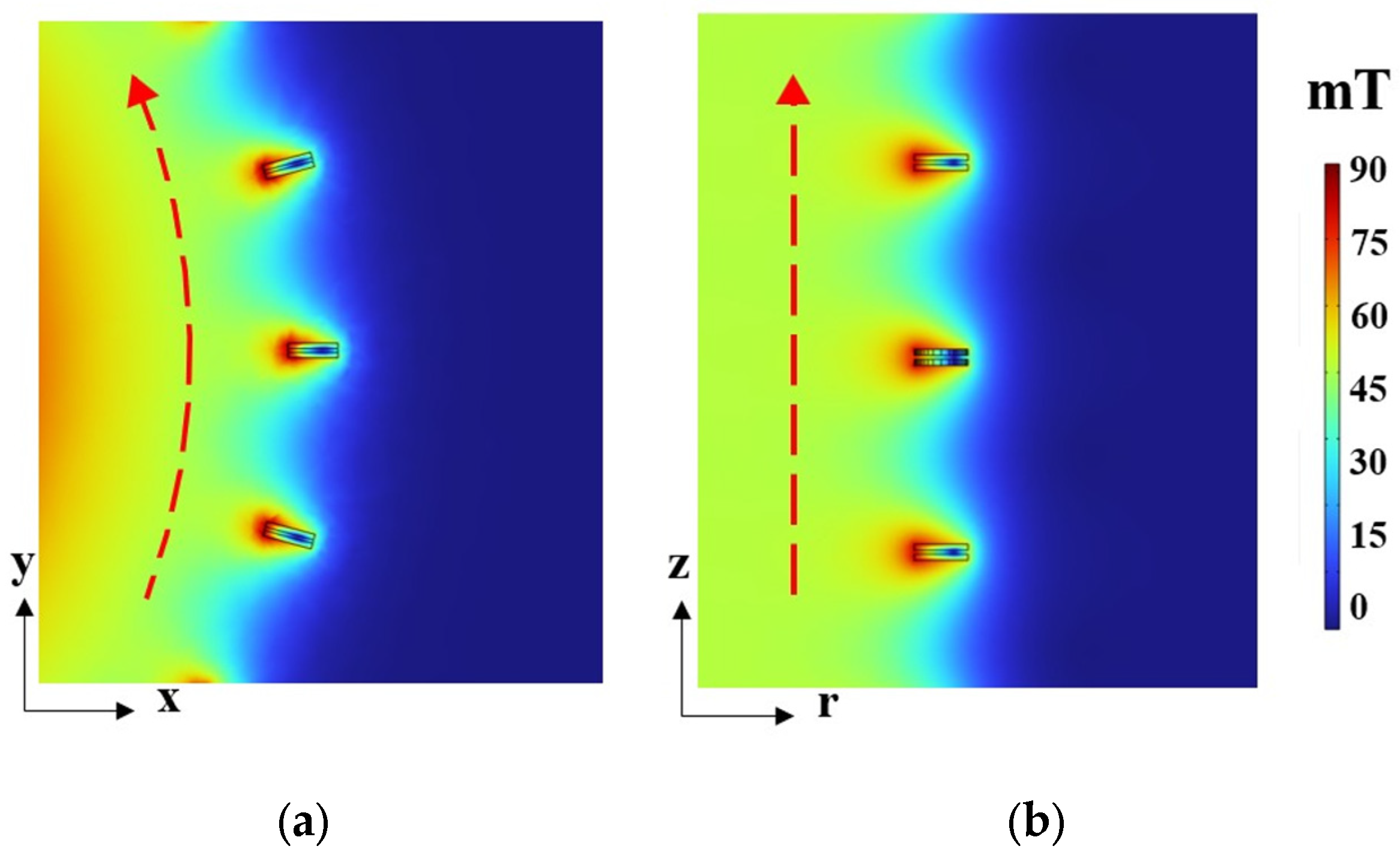

4. Electromagnetic Modeling and Analysis

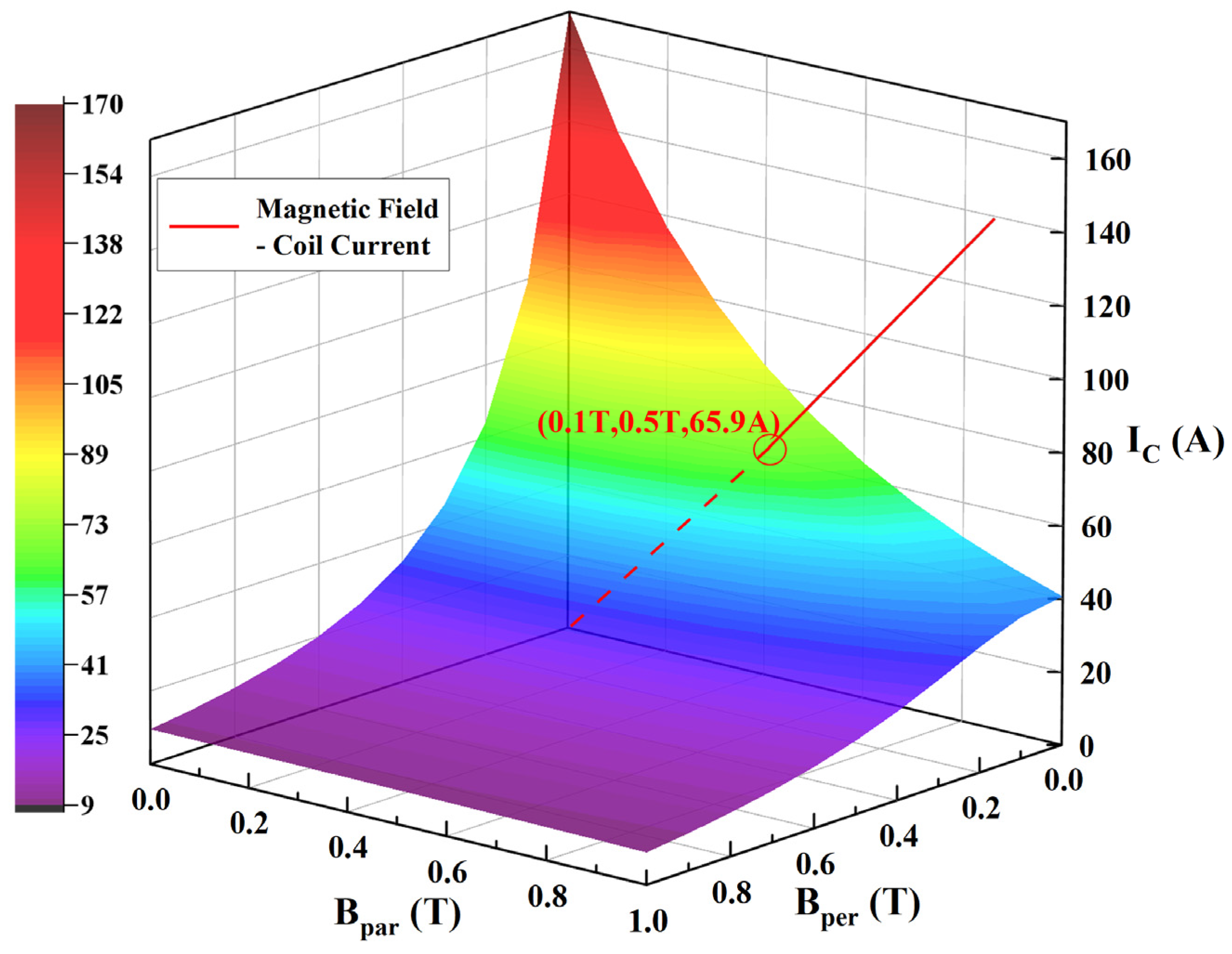

4.1. Inductance and Critical Current Evaluation

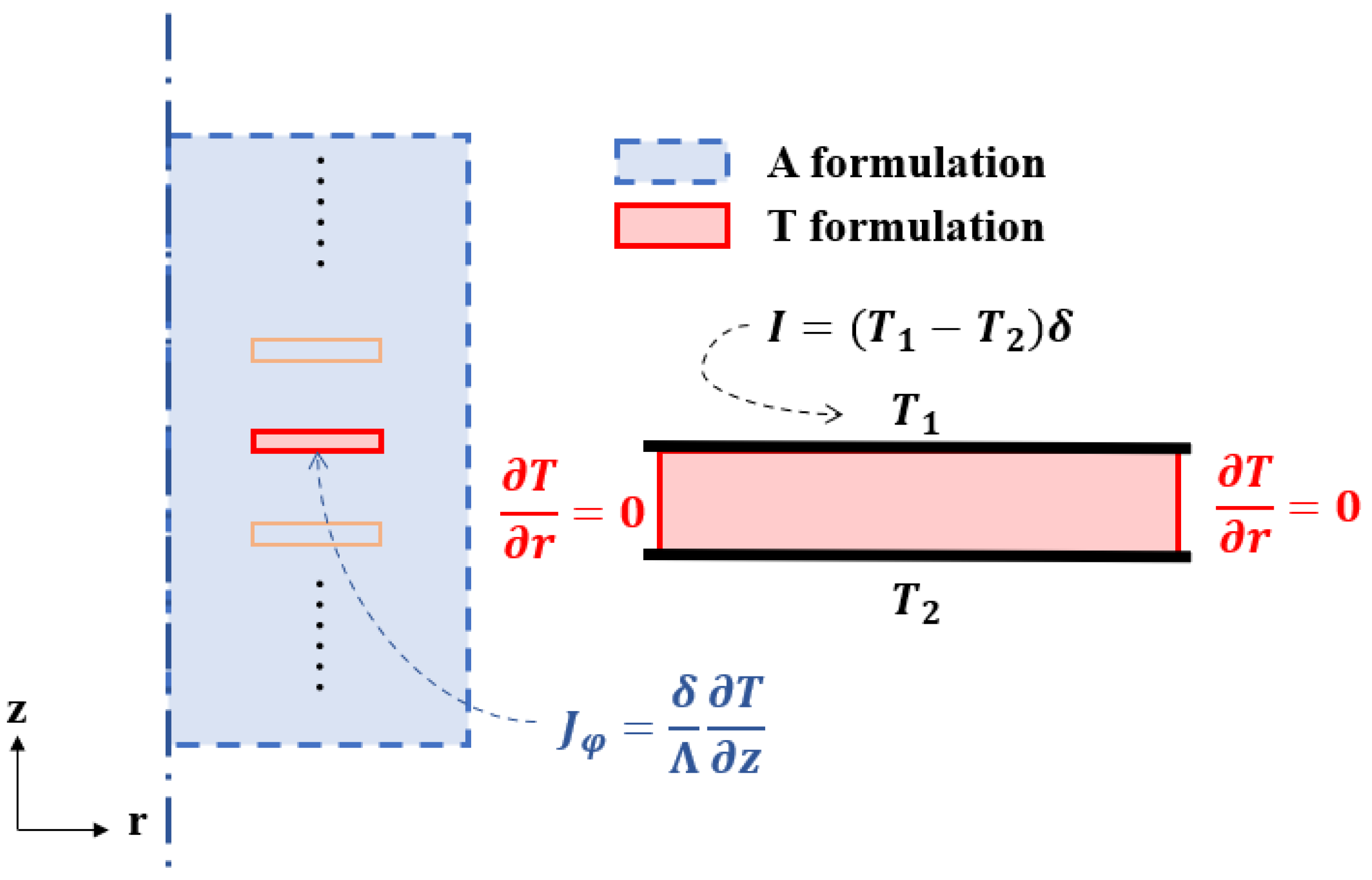

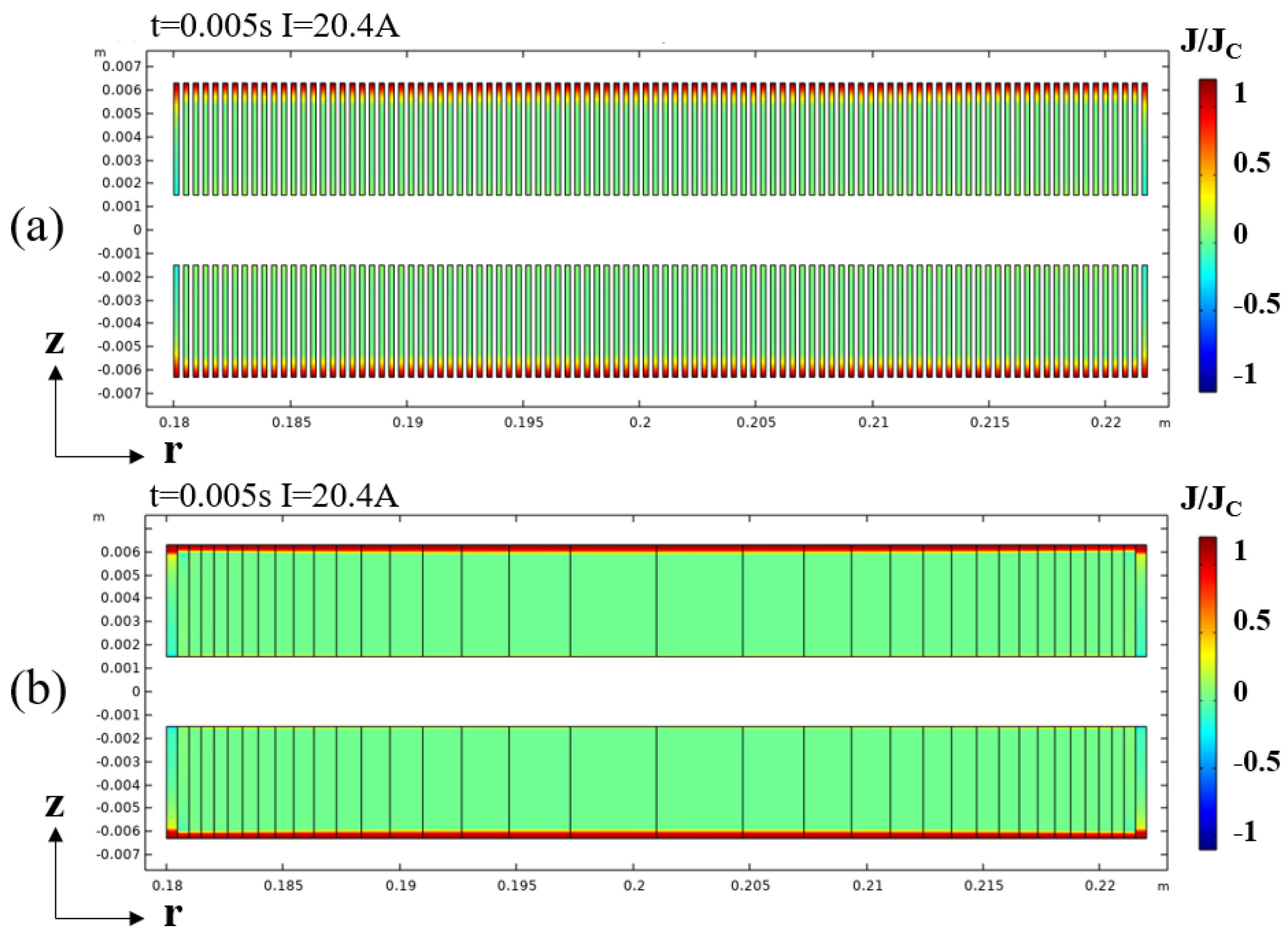

4.2. AC Loss Evaluation

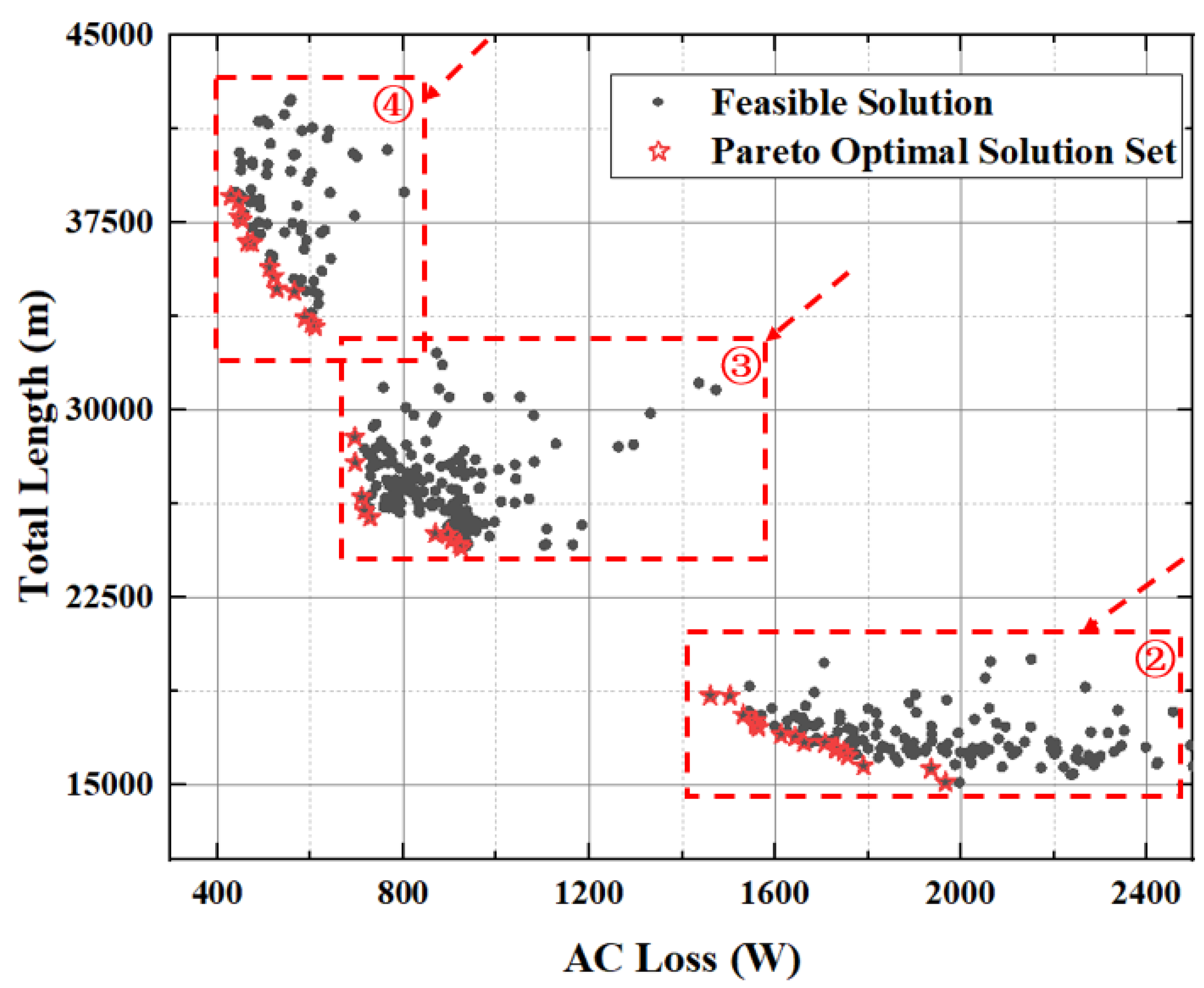

5. Analysis of Optimization Result

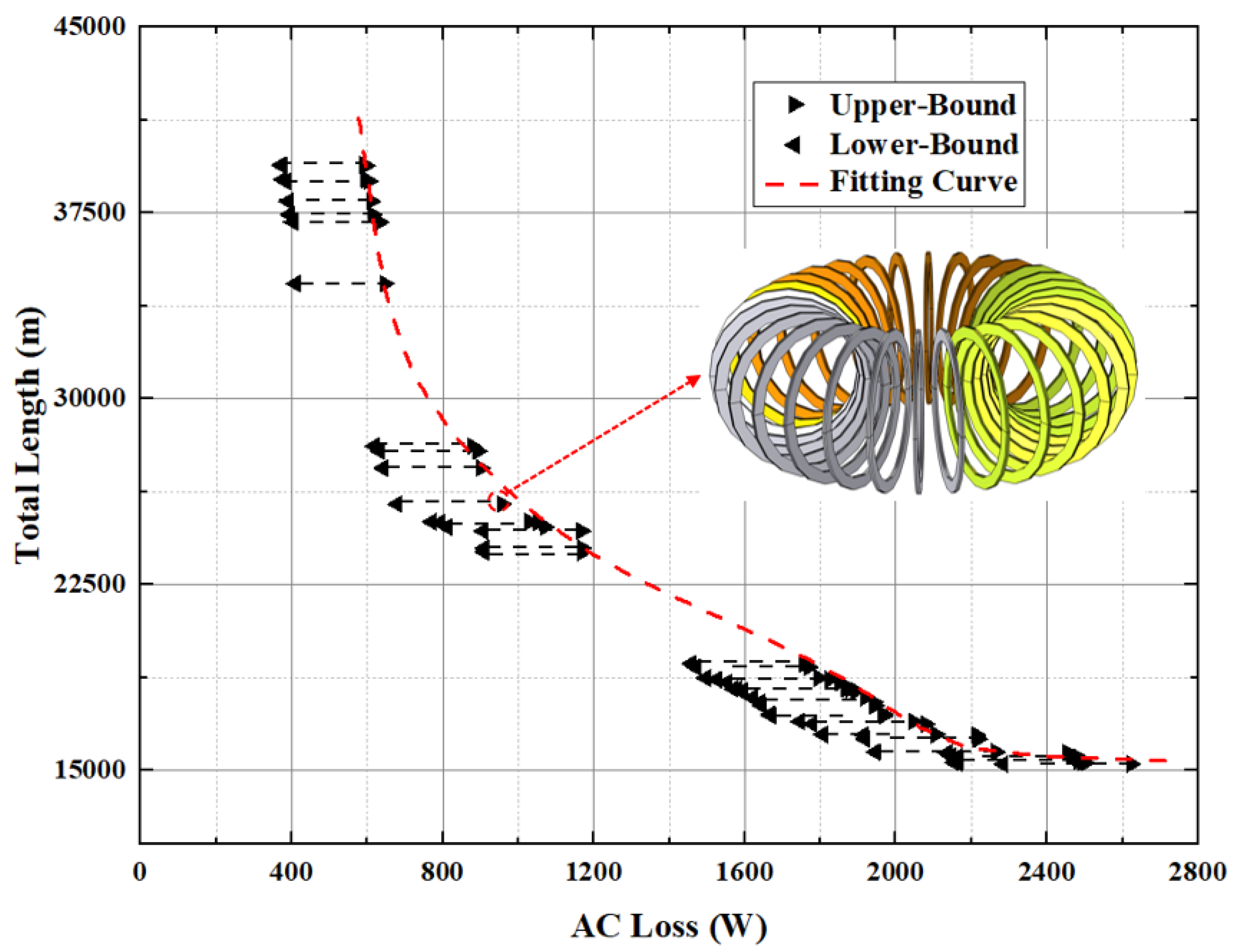

5.1. Optimization Result of MOGA

5.2. Economic Analysis of the Shunt Reactor

5.3. Performance Analysis of the Reactor with the Least Cost

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Amreiz, H.; Janbey, A.; Darwish, M. Emulation of Series and Shunt Reactor Compensation. In Proceedings of the 2020 55th International Universities Power Engineering Conference (UPEC), Turin, Italy, 1–4 September 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotfi, A.; Rahimpour, E. Optimum design of core blocks and analyzing the fringing effect in shunt reactors with distributed gapped-core. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2013, 101, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawood, K.; Komurgoz, G.; Isik, F. Modelling of the Shunt Reactor by using Finite Element Analysis. In Proceedings of the 2020 XI International Conference on Electrical Power Drive Systems (ICEPDS), St. Petersburg, Russia, 4–7 October 2020; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Li, L.; Cheng, Z.; Tian, C.; Han, Y. Study on Vibration of Iron Core of Transformer and Reactor Based on Maxwell Stress and Anisotropic Magnetostriction. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2019, 55, 9400205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, Z.; Qian, G.; Hao, C.; Liu, Y.; Yang, C.; Ou, Y. Development and test of distributed current monitoring device for dry type air core reactor. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on High Voltage Engineering and Application (ICHVE), Beijing, China, 6–10 September 2020; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mehmood, K.; Cheema, K.M.; Tahir, M.F.; Saleem, A.; Milyani, A.H. A comprehensive review on magnetically controllable reactor: Modelling, applications and future prospects. Energy Rep. 2021, 7, 2354–2378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; He, H.-W.; Dai, M.; Lou, Y. Application of controllable reactors to 1000 kV AC compact transmission line. High Voltage Eng. 2011, 37, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar]

- Shen, S.F.; Wu, X.; Yan, S.; Wang, X.; Ren, L.; Yi, X.; Liu, Y. Research on the characteristics of a high-temperature superconducting leakage flux-controlled reactor. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2022, 69, 10101–10111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, J.X.; Tang, Y.J.; Xiao, X.Y.; Du, B.X.; Wang, Q.L.; Wang, J.H.; Wang, S.H.; Bi, Y.F.; Zhu, J.G. HTS power devices and systems: Principles, characteristics, performance, and efficiency. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2016, 26, 3800526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Tang, Y.; Ren, L.; Yan, S.; Yang, Z.; Xu, Y.; Zhang, C. Development of a new type of HTS controllable reactor with orthogonally configured Core. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2017, 27, 5000205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, H.; Zhang, Q. Multiobjective Optimization Problems with Complicated Pareto Sets, MOEA/D and NSGA-II. IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput. 2009, 13, 284–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IEEE PC57.21/D5.3; IEEE Approved Draft Standard Requirements, Terminology, and Test Code for Shunt Reactors Rated Over 500 kVA. IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2021; pp. 1–133.

- Yang, Z.; Ren, L.; Xu, Y.; Shi, J.; Qiu, Y.; Duan, P.; Fang, J.; Wang, C.; Song, M.; Li, L. Optimized design and electromagnetic-thermal- mechanical analysis of a toroidal D-Shaped superconducting magnet in 5 MW LIQHY-SMES system. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 4904107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, Y.; Cheng, R.; Zhang, X.; Jin, Y. PlatEMO: A MATLAB platform for evolutionary multi-objective optimization [Educational Forum]. IEEE Comput. Intell. Mag. 2017, 12, 73–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chan, H.L.; Cheng, K.W.E.; Sutanto, D. A simplified Neumann’s formula for calculation of inductance of spiral coil. In Proceedings of the 2000 Eighth International Conference on Power Electronics and Variable Speed Drives, London, UK, 18–19 September 2000; pp. 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonntag, C.L.W.; Lomonova, E.A.; Duarte, J.L. Implementation of the Neumann formula for calculating the mutual inductance between planar PCB inductors. In Proceedings of the 2008 18th International Conference on Electrical Machines, Vilamoura, Portugal, 6–9 September 2008; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, H.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Xu, Q.; Jiao, T.; Wang, X.; Jin, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Sheng, J. Numerical study on transport ac loss characteristics of toroidal air-core superconducting shunt reactor. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2025, 35, 4701105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; You, S.; Fang, J.; Badcock, R.A.; Long, N.J.; Jiang, Z. AC loss study on a 3-phase HTS 1 MVA transformer coupled with a three-limb iron core. Superconductivity 2024, 10, 100095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Hempstead, C.; Strnad, A. Critical persistent currents in hard superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1962, 9, 306–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, F.; Venuturumilli, S.; Zhang, H.; Zhang, M.; Kvitkovic, J.; Pamidi, S.; Wang, Y.; Yuan, W. A finite element model for simulating second generation high temperature superconducting coils/stacks with large number of turns. J. Appl. Phys. 2017, 122, 043903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrospe-Juarez, E.; Trillaud, F.; Zermeño, V.; Grilli, F. Advanced electromagnetic modeling of large-scale high-temperature superconductor systems based on H and T-A formulations. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2021, 34, 044002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berrospe-Juarez, E.; Zermeño, V.; Trillaud, F.; Grilli, F. Real-time simulation of large-scale HTS systems: Multi-scale and homogeneous models using the T–A formulation. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2019, 32, 065003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zong, X.; Xie, W. Cooling system for China’s 35 kV/2.2kA/1.2 km high-temperature superconducting cable achieves two-year successful operation. Superconductivity 2024, 10, 100100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Dong, H.; Huang, D.; Shang, H.; Xie, B.; Zou, Q.; Zhang, L.; Feng, C.; Gu, H.; Ding, F. Advances in second-generation high-temperature superconducting tapes and their applications in high-field magnets. Soft Sci. 2022, 2, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GB/T 1094.3-2017; Power Transformers—Part 3: Insulation levels, Insulation Tests and External Insulation Air Gaps. National Standard of the People’s Republic of China: Beijing, China, 2017.

| Items | Value |

|---|---|

| Number of coils nc | 3 |

| Number of turns nt | 2 |

| Number of parallel branches b | 3 |

| Inner radius of coil r (m) | 0.228 |

| Surrounding radius R (m) | 0.452 |

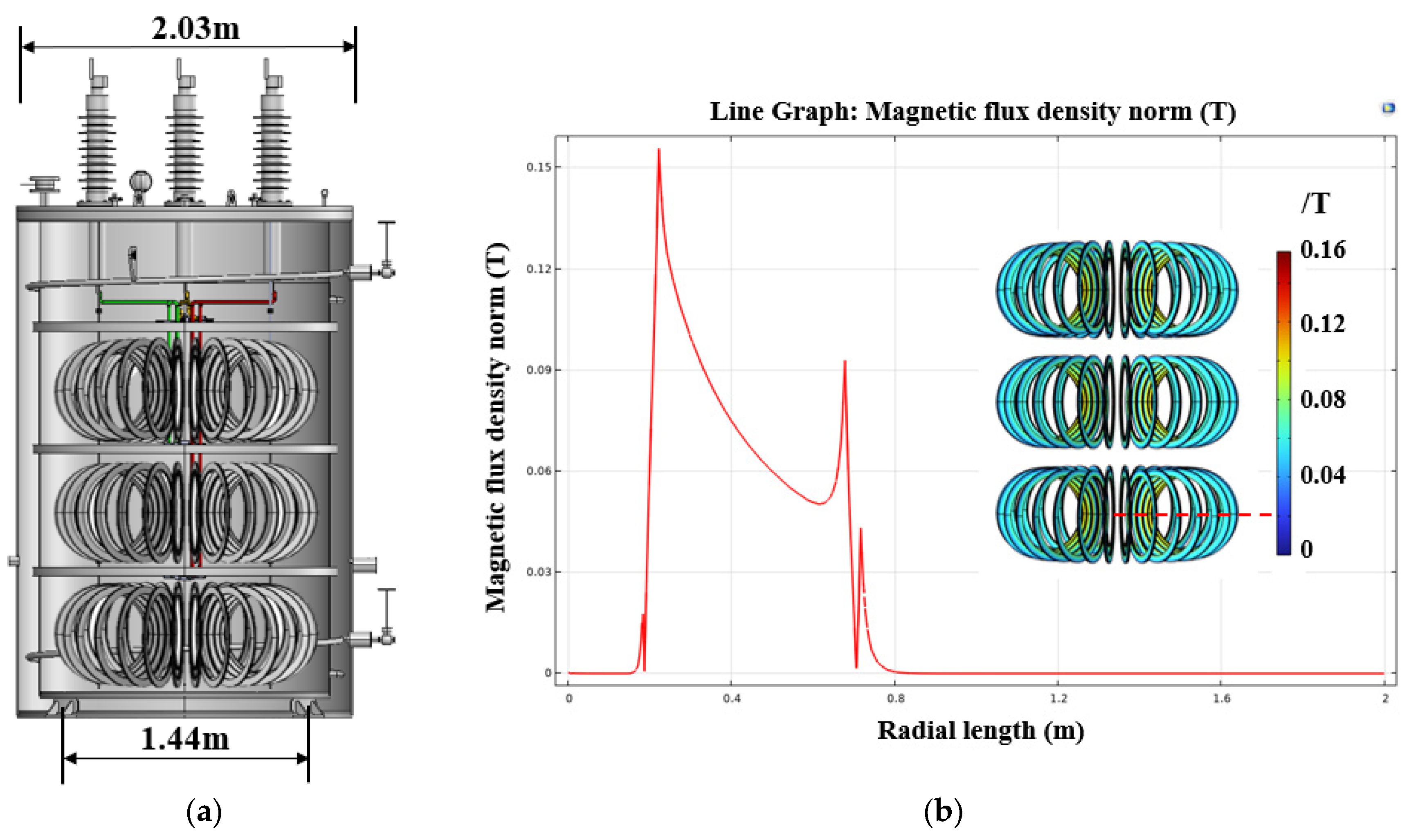

| Diameter D (m) | 1.44 |

| Total length TL (m) | 25,712 |

| (A) | 27.2 |

| (A) | 63.7 |

| Inductance L (H) | 0.3173 |

| Lower-bound of AC loss (W) | 681 |

| Upper-bound of AC loss (W) | 955 |

| Cost of HTS tapes (USD) | 582,493 |

| Cost of cooling system (USD) | 261,670 |

| Total cost (USD) | 844,163 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Xu, Q.; Tian, H.; Li, H.; Su, L.; Wei, B.; Peng, S.; Sheng, J.; Jin, Z. Multi-Objective Structural Optimization of a 10 kV/1 MVar Superconducting Toroidal Air-Core Reactor. Energies 2025, 18, 6261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236261

Xu Q, Tian H, Li H, Su L, Wei B, Peng S, Sheng J, Jin Z. Multi-Objective Structural Optimization of a 10 kV/1 MVar Superconducting Toroidal Air-Core Reactor. Energies. 2025; 18(23):6261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236261

Chicago/Turabian StyleXu, Qingchuan, Haoyang Tian, Honglei Li, Lei Su, Bengang Wei, Shuhao Peng, Jie Sheng, and Zhijian Jin. 2025. "Multi-Objective Structural Optimization of a 10 kV/1 MVar Superconducting Toroidal Air-Core Reactor" Energies 18, no. 23: 6261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236261

APA StyleXu, Q., Tian, H., Li, H., Su, L., Wei, B., Peng, S., Sheng, J., & Jin, Z. (2025). Multi-Objective Structural Optimization of a 10 kV/1 MVar Superconducting Toroidal Air-Core Reactor. Energies, 18(23), 6261. https://doi.org/10.3390/en18236261