Navigating the Treatment Landscape of Odontogenic Sinusitis: Current Trends and Future Directions

Abstract

1. Introduction: Odontogenic Sinusitis—Incidence and Diagnosis

2. Methods

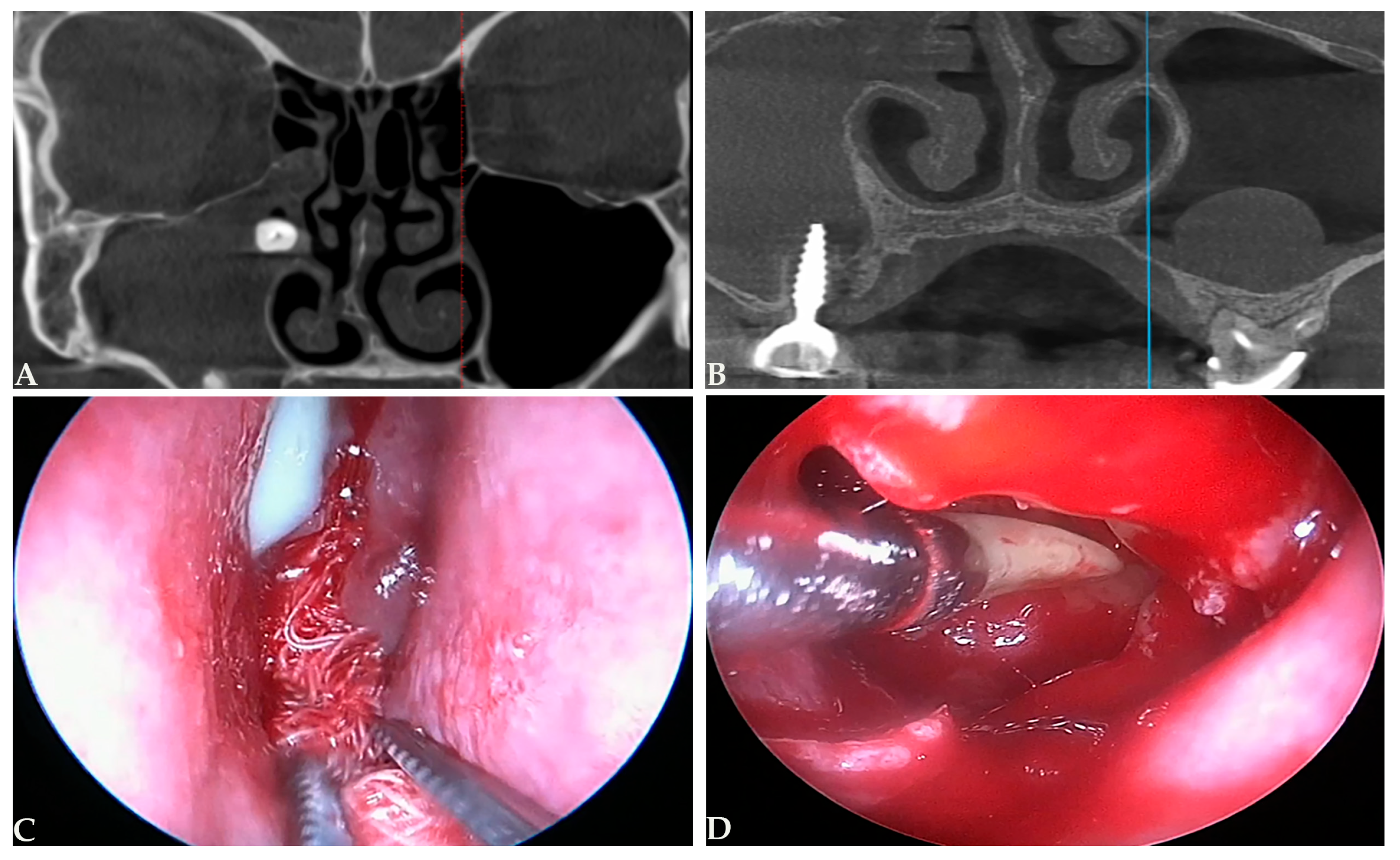

3. Dental Pathology Triggering Odontogenic Sinusitis

4. Management Options in Odontogenic Sinusitis

4.1. Antibiotic Therapy in Odontogenic Sinusitis

4.2. Dental Treatment in Odontogenic Sinusitis

4.3. Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Odontogenic Sinusitis

4.4. The Treatment Sequence of ESS and Dental Therapy in Odontogenic Sinusitis

4.5. Extent of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery in Odontogenic Sinusitis

4.6. Recurrence Rates in Odontogenic Sinusitis

5. Future Directions in the Management of Odontogenic Sinusitis

6. Limitations

7. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CT | Computed tomography |

| ESS | Endoscopic sinus surgery |

| MA | Maxillary antrostomy |

| OAC | Oroantral communication |

| OAF | Oroantral fistula |

| ODS | Odontogenic sinusitis |

| SNOT-22 | Sino-Nasal Outcome Test-22 |

References

- Craig, J.R.; Poetker, D.M.; Aksoy, U.; Allevi, F.; Biglioli, F.; Cha, B.Y.; Chiapasco, M.; Lechien, J.R.; Safadi, A.; Simuntis, R.; et al. Diagnosing Odontogenic Sinusitis: An International Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 1235–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.R. Odontogenic Sinusitis: A State-of-the-Art Review. World J. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2022, 8, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melén, I.; Lindahl, L.; Andréasson, L.; Rundcrantz, H. Chronic maxillary sinusitis. Definition, diagnosis and relation to dental infections and nasal polyposis. Acta Otolaryngol. 1986, 101, 320–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albu, S.; Baciut, M. Failures in Endoscopic Surgery of the Maxillary Sinus. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010, 142, 196–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turfe, Z.; Ahmad, A.; Peterson, E.I.; Craig, J.R. Odontogenic Sinusitis Is a Common Cause of Unilateral Sinus Disease with Maxillary Sinus Opacification. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 1515–1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lechien, J.R.; Filleul, O.; Costa de Araujo, P.; Hsieh, J.W.; Chantrain, G.; Saussez, S. Chronic Maxillary Rhinosinusitis of Dental Origin: A Systematic Review of 674 Patient Cases. Int. J. Otolaryngol. 2014, 2014, 465173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zirk, M.; Dreiseidler, T.; Pohl, M.; Rothamel, D.; Buller, J.; Peters, F.; Zöller, J.E.; Kreppel, M. Odontogenic Sinusitis Maxillaris: A Retrospective Study of 121 Cases with Surgical Intervention. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2017, 45, 520–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, V.K.; Spillinger, A.; Peterson, E.I.; Craig, J.R. Odontogenic Sinusitis Publication Trends from 1990 to 2019: A Systematic Review. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2021, 278, 3857–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simuntis, R.; Vaitkus, J.; Kubilius, R.; Padervinskis, E.; Tušas, P.; Leketas, M.; Šiupšinskienė, N.; Vaitkus, S. Comparison of Sino-Nasal Outcome Test 22 Symptom Scores in Rhinogenic and Odontogenic Sinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2019, 33, 44–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goyal, V.K.; Ahmad, A.; Turfe, Z.; Peterson, E.I.; Craig, J.R. Predicting Odontogenic Sinusitis in Unilateral Sinus Disease: A Prospective, Multivariate Analysis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2021, 35, 164–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allevi, F.; Fadda, G.L.; Rosso, C.; Martino, F.; Pipolo, C.; Cavallo, G.; Felisati, G.; Saibene, A.M. Diagnostic Criteria for Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2021, 35, 713–721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckhoff, A.; Cox, D.; Luk, L.; Maidman, S.; Wise, S.K.; DelGaudio, J.M. Unilateral versus bilateral sinonasal disease: Considerations in differential diagnosis and workup. Laryngoscope 2020, 130, E116–E121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin-Kassab, A.; Bhargava, P.; Tibbetts, R.J.; Griggs, Z.H.; Peterson, E.I.; Craig, J.R. Comparison of Bacterial Maxillary Sinus Cultures between Odontogenic Sinusitis and Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2021, 11, 40–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saibene, A.M.; Vassena, C.; Pipolo, C.; Trimboli, M.; De Vecchi, E.; Felisati, G.; Drago, L. Odontogenic and Rhinogenic Chronic Sinusitis: A Modern Microbiological Comparison: Odonto- and Rhinogenic Sinusitis Microbiology. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2016, 6, 41–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.R.; Tataryn, R.W.; Cha, B.Y.; Bhargava, P.; Pokorny, A.; Gray, S.T.; Mattos, J.L.; Poetker, D.M. Diagnosing Odontogenic Sinusitis of Endodontic Origin: A Multidisciplinary Literature Review. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2021, 42, 102925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.R.; Tataryn, R.W.; Aghaloo, T.L.; Pokorny, A.T.; Gray, S.T.; Mattos, J.L.; Poetker, D.M. Management of Odontogenic Sinusitis: Multidisciplinary Consensus Statement. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2020, 10, 901–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grayson, J.W.; Hopkins, C.; Mori, E.; Senior, B.; Harvey, R.J. Contemporary Classification of Chronic Rhinosinusitis beyond Polyps vs. No Polyps: A Review: A Review. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2020, 146, 831–838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fokkens, W.J.; Lund, V.J.; Hopkins, C.; Hellings, P.W.; Kern, R.; Reitsma, S.; Toppila-Salmi, S.; Bernal-Sprekelsen, M.; Mullol, J.; Alobid, I.; et al. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps 2020. Rhinology 2020, 58 (Suppl. S29), 1–464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.R.; Saibene, A.M.; Felisati, G. Sinusitis Management in Odontogenic Sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 57, 1157–1171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brook, I. Microbiology of Acute and Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis Associated with an Odontogenic Origin. Laryngoscope 2005, 115, 823–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, J.C.; Xia, T. Antibiotic Susceptibility of Bacteria Associated with Endodontic Abscesses. J. Endod. 2003, 29, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglisi, S.; Privitera, S.; Maiolino, L.; Serra, A.; Garotta, M.; Blandino, G.; Speciale, A. Bacteriological Findings and Antimicrobial Resistance in Odontogenic and Non-Odontogenic Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis. J. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 60 Pt 9, 1353–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siqueira, J.F., Jr.; Rôças, I.N. Microbiology and Treatment of Acute Apical Abscesses. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2013, 26, 255–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cope, A.L.; Francis, N.; Wood, F.; Chestnutt, I.G. Systemic Antibiotics for Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis and Acute Apical Abscess in Adults. Cochrane Libr. 2018, 2018, CD010136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skucaite, N.; Peciuliene, V.; Vitkauskiene, A.; Machiulskiene, V. Susceptibility of Endodontic Pathogens to Antibiotics in Patients with Symptomatic Apical Periodontitis. J. Endod. 2010, 36, 1611–1616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthews, D.C.; Sutherland, S.; Basrani, B. Emergency Management of Acute Apical Abscesses in the Permanent Dentition: A Systematic Review of the Literature. J. Can. Dent. Assoc. 2003, 69, 660. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Otero, N.; Posse, L.; Carmona, J. Efficacy of Fluoroquinolones against Pathogenic Oral Bacteria. Mini. Rev. Med. Chem. 2009, 9, 1147–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sato, K.; Chitose, S.I.; Sato, K.; Sato, F.; Ono, T.; Umeno, H. Pathophysiology of current odontogenic maxillary sinusitis and endoscopic sinus surgery preceding dental treatment. Auris Nasus Larynx 2021, 48, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Endodontics. AAE Position Statement: AAE Guidance on the Use of Systemic Antibiotics in Endodontics. Spec. Comm. Antibiot. Use Endod. 2017, 43, 1409–1413. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, J.R.; Cheema, A.J.; Dunn, R.T.; Vemuri, S.; Peterson, E.L. Extrasinus Complications from Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2021, 166, 623–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, J.E.; Patel, T.; Rullan-Oliver, B. Odontogenic Sinusitis Is a CommonCause of Operative Extra-Sinus Infectious Complications. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2022, 36, 808–815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Association of Endodontics. Treatment Standards; American Association of Endodontics: Chicago, IL, USA, 2018; Available online: https://www.aae.org/specialty/wp-content/uploads/sites/2/2018/04/TreatmentStandards_Whitepaper.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2025).

- Tomomatsu, N.; Uzawa, N.; Aragaki, T.; Harada, K. Aperture Width of the Osteomeatal Complex as a Predictor of Successful Treatment of Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2014, 43, 1386–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Longhini, A.B.; Branstetter, B.F.; Ferguson, B.J. Unrecognized Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis: A Cause of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery Failure. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2010, 24, 296–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.L.; Nichols, B.G.; Poetker, D.M.; Loehrl, T.A. Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Case Series Studying Diagnosis and Management: Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Case Series. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2015, 5, 597–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, B.J.; Jung, S.M.; Lee, H.N.; Kim, H.G.; Chung, J.H.; Jeong, J.H. Treatment Strategy for Odontogenic Sinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2021, 35, 206–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Simuntis, R.; Kubilius, R.; Tušas, P.; Leketas, M.; Vaitkus, J.; Vaitkus, S. Chronic Odontogenic Rhinosinusitis: Optimization of Surgical Treatment Indications. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2020, 34, 767–774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crovetto-Martínez, R.; Martin-Arregui, F.-J.; Zabala-López-de-Maturana, A.; Tudela-Cabello, K.; Crovetto-de la Torre, M.-A. Frequency of the Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis Extended to the Anterior Ethmoid Sinus and Response to Surgical Treatment. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2014, 19, e409–e413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwiatkowska, M.A.; Szczygielski, K.; Brociek-Piczynska, A. The Influence of Endodontic Lesions on The Clinical Evolution of Odontogenic Sinusitis-A Cohort Tudy. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiam, N.T.-L.; Goldberg, A.N.; Murr, A.H.; Pletcher, S.D. Surgical Treatment of Chronic Rhinosinusitis after Sinus Lift. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2017, 31, 271–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, S.J.; Park, J.S.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, C.H.; Park, Y.H.; Bae, J.H. Clinical Features and Treatment Outcomes of Dental Implant-Related Paranasal Sinusitis: A 2-Year Prospective Observational Study. Clin. Oral Implants Res. 2016, 27, e100–e104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.-W.; Huang, C.-C.; Chang, P.-H.; Chen, C.-W.; Wu, C.-C.; Fu, C.-H.; Lee, T.-J. The Characteristics and New Treatment Paradigm of Dental Implant-Related Chronic Rhinosinusitis. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2013, 27, 237–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shin, J.-M.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, H.-M.; Park, I.-H. Changing Trends in the Clinical Characteristics and Treatment Strategies for Odontogenic Sinusitis over the Past 10 Years. Ear Nose Throat J. 2024, 103, 717–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsuzuki, K.; Kuroda, K.; Hashimoto, K.; Okazaki, K.; Noguchi, K.; Kishimoto, H.; Nishikawa, H.; Sakagami, M. Odontogenic Chronic Rhinosinusitis Patients Undergoing Tooth Extraction: Oral Surgeon and Otolaryngologist Viewpoints and Appropriate Management. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2020, 134, 241–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yassin-Kassab, A.; Peterson, E.L.; Craig, J.R. Total Times to Treatment Completion and Clinical Outcomes in Odontogenic Sinusitis. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2023, 44, 103921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, H.; Sakashita, M.; Adachi, N.; Matsuda, S.; Fujieda, S.; Yoshimura, H. Relationship between Infected Tooth Extraction and Improvement of Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis. Laryngoscope Investig. Otolaryngol. 2022, 7, 335–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Craig, J.R.; McHugh, C.I.; Griggs, Z.H.; Peterson, E.I. Optimal Timing of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery for Odontogenic Sinusitis. Laryngoscope 2019, 129, 1976–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocum, P.; Sedý, J.; Traboulsi, J.; Jirák, P. One-Stage Combined ENT and Dental Surgical Treatment of Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Prospective Study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 1347–1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saibene, A.M.; Collurà, F.; Pipolo, C.; Bulfamante, A.M.; Lozza, P.; Maccari, A.; Arnone, F.; Ghelma, F.; Allevi, F.; Biglioli, F.; et al. Odontogenic Rhinosinusitis and Sinonasal Complications of Dental Disease or Treatment: Prospective Validation of a Classification and Treatment Protocol. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2019, 276, 401–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galli, M.; De Soccio, G.; Cialente, F.; Candelori, F.; Federici, F.R.; Ralli, M.; De Vincentiis, M.; Minni, A. Chronic Maxillary Sinusitis of Dental Origin and Oroantral Fistula: The Results of Combined Surgical Approach in an Italian University Hospital. Bosn. J. Basic Med. Sci. 2020, 20, 524–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molteni, M.; Bulfamante, A.M.; Pipolo, C.; Lozza, P.; Allevi, F.; Pisani, A.; Chiapasco, M.; Portaleone, S.M.; Scotti, A.; Maccari, A.; et al. Odontogenic Sinusitis and Sinonasal Complications of Dental Treatments: A Retrospective Case Series of 480 Patients with Critical Assessment of the Current Classification. Acta Otorhinolaryngol. Ital. 2020, 40, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felisati, G.; Chiapasco, M.; Lozza, P.; Saibene, A.M.; Pipolo, C.; Zaniboni, M.; Biglioli, F.; Borloni, R. Sinonasal Complications Resulting from Dental Treatment: Outcome-Oriented Proposal of Classification and Surgical Protocol. Am. J. Rhinol. Allergy 2013, 27, e101–e106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.-Y.; Mo, J.-H.; Chung, Y.-J. Analysis of Treatment Outcome Associated with Pre-Operative Diagnostic Accuracy Changes and Dental Treatment Timing in Odontogenic Sinusitis Involving Unilateral Maxillary Sinus. Korean J. Otorhinolaryngol.-Head Neck Surg. 2019, 62, 624–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, F.; Emanuelli, E.; Franz, L.; Tel, A.; Robiony, M. Single-Step Surgical Treatment of Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis: A Retrospective Study of 98 Cases. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2019, 47, 1249–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gâta, A.; Toader, C.; Valean, D.; Trombitaș, V.E.; Albu, S. Role of Endoscopic Sinus Surgery and Dental Treatment in the Management of Odontogenic Sinusitis Due to Endodontic Disease and Oroantral Fistula. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 2712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almanzo, S.; Astray-Gómez, S.; Tortajada-Torralba, I.; Cabrera-Guijo, J.; Fito-Martorell, L.; Muñoz-Fernández, N.; Armengot-Carceller, M.; García-Piñero, A. Impact of Combined Surgery on Reoperation Rates in Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Retrospective Comparative Study. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2025, 282, 4123–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.; Li, Z.; Liu, J. The necessity of subsequent dental treatment for odontogenic sinusitis after endoscopic sinus surgery. Ear Nose Throat J. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ungar, O.J.; Yafit, D.; Kleinman, S.; Raiser, V.; Safadi, A. Odontogenic Sinusitis Involving the Frontal Sinus: Is Middle Meatal Antrostomy Enough? Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2018, 275, 2291–2295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Safadi, A.; Kleinman, S.; Oz, I.; Wengier, A.; Mahameed, F.; Vainer, I.; Ungar, O.J. Questioning the Justification of Frontal Sinusotomy for Odontogenic Sinusitis. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2020, 78, 762–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.R.; Saibene, A.M.; Adappa, N.D.; Douglas, J.E.; Eide, J.G.; Felisati, G.; Kohanski, M.A.; Kshirsagar, R.S.; Kwiecien, C.; Lee, D.; et al. Maxillary Antrostomy versus Complete Sinus Surgery for Odontogenic Sinusitis with Frontal Sinus Extension. Laryngoscope 2025, 135, 586–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeConde, A.S.; Smith, T.L. Outcomes after Frontal Sinus Surgery: An Evidence-Based Review. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2016, 49, 1019–1033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakkas, A.; Weiß, C.; Ebeling, M.; Pietzka, S.; Wilde, F.; Evers, T.; Thiele, O.C.; Mischkowski, R.A.; Scheurer, M. Factors Influencing Recurrence after Surgical Treatment of Odontogenic Maxillary Sinusitis: An Analysis from the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Point of View. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J.; Wang, C.; Wang, X.; Chen, F.; Zhang, W.; Sun, H.; Yan, F.; Pan, Y.; Zhu, D.; Yang, Q.; et al. Expert consensus on odontogenic maxillary sinusitis multi-disciplinary treatment. Int J Oral Sci. 2024, 16, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.R.; Tataryn, R.W.; Saibene, A.M. The Future of Odontogenic Sinusitis. Otolaryngol. Clin. N. Am. 2024, 57, 1173–1181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shukairy, M.K.; Burmeister, C.; Ko, A.B.; Craig, J.R. Recognizing Odontogenic Sinusitis: A National Survey of Otolaryngology Chief Residents. Am. J. Otolaryngol. 2020, 41, 102635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Lan, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Zhang, L. Formation of Papillary Mucosa Folds and Enhancement of Epithelial Barrier in Odontogenic Sinusitis: Papillary Mucosa Folds in OS. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2019, 9, 1281–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andric, M.; Saranovic, V.; Drazic, R.; Brkovic, B.; Todorovic, L. Functional Endoscopic Sinus Surgery as an Adjunctive Treatment for Closure of Oroantral Fistulae: A Retrospective Analysis. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endod. 2010, 109, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosso, C.; Urbanelli, A.; Spoldi, C.; Felisati, G.; Pecorari, G.; Pipolo, C.; Nava, N.; Saibene, A.M. Pediatric Odontogenic Sinusitis: A Systematic Review. J. Clin. Med. 2024, 13, 2215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Craig, J.R.; Dai, X.; Bellemore, S.; Woodcroft, K.J.; Wilson, C.; Keller, C.; Bobbitt, K.R.; Ramesh, M. Inflammatory Endotype of Odontogenic Sinusitis. Int. Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2023, 13, 998–1006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saibene, A.M.; Allevi, F.; Calvo-Henriquez, C.; Maniaci, A.; Mayo-Yáñez, M.; Paderno, A.; Vaira, L.A.; Felisati, G.; Craig, J.R. Reliability of Large Language Models in Managing Odontogenic Sinusitis Clinical Scenarios: A Preliminary Multidisciplinary Evaluation. Eur. Arch. Otorhinolaryngol. 2024, 281, 1835–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murad, M.H.; Sultan, S.; Haffar, S.; Bazerbachi, F. Methodological quality and synthesis of case series and case reports. BMJ Evid. Based Med. 2018, 23, 60–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bazerbachi, F.; Haffar, S.; Szarka, L.A.; Wang, Z.; Prokop, L.J.; Murad, M.H.; Camilleri, M. Secretory diarrhea and hypokalemia associated with colonic pseudo-obstruction: A case study and systematic analysis of the literature. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2017, 29, e13120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the Lithuanian University of Health Sciences. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albu, S.; Roman, A. Navigating the Treatment Landscape of Odontogenic Sinusitis: Current Trends and Future Directions. Medicina 2025, 61, 2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122175

Albu S, Roman A. Navigating the Treatment Landscape of Odontogenic Sinusitis: Current Trends and Future Directions. Medicina. 2025; 61(12):2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122175

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbu, Silviu, and Alexandra Roman. 2025. "Navigating the Treatment Landscape of Odontogenic Sinusitis: Current Trends and Future Directions" Medicina 61, no. 12: 2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122175

APA StyleAlbu, S., & Roman, A. (2025). Navigating the Treatment Landscape of Odontogenic Sinusitis: Current Trends and Future Directions. Medicina, 61(12), 2175. https://doi.org/10.3390/medicina61122175