Key Genes Involved in the Saline–Water Stress Tolerance of Aloe vera

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. RNA Extraction

2.3. Primers

2.4. RT-qPCR Quantitative Analysis

2.5. Biosynthesis of Mannose-Rich Polysaccharides

2.6. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

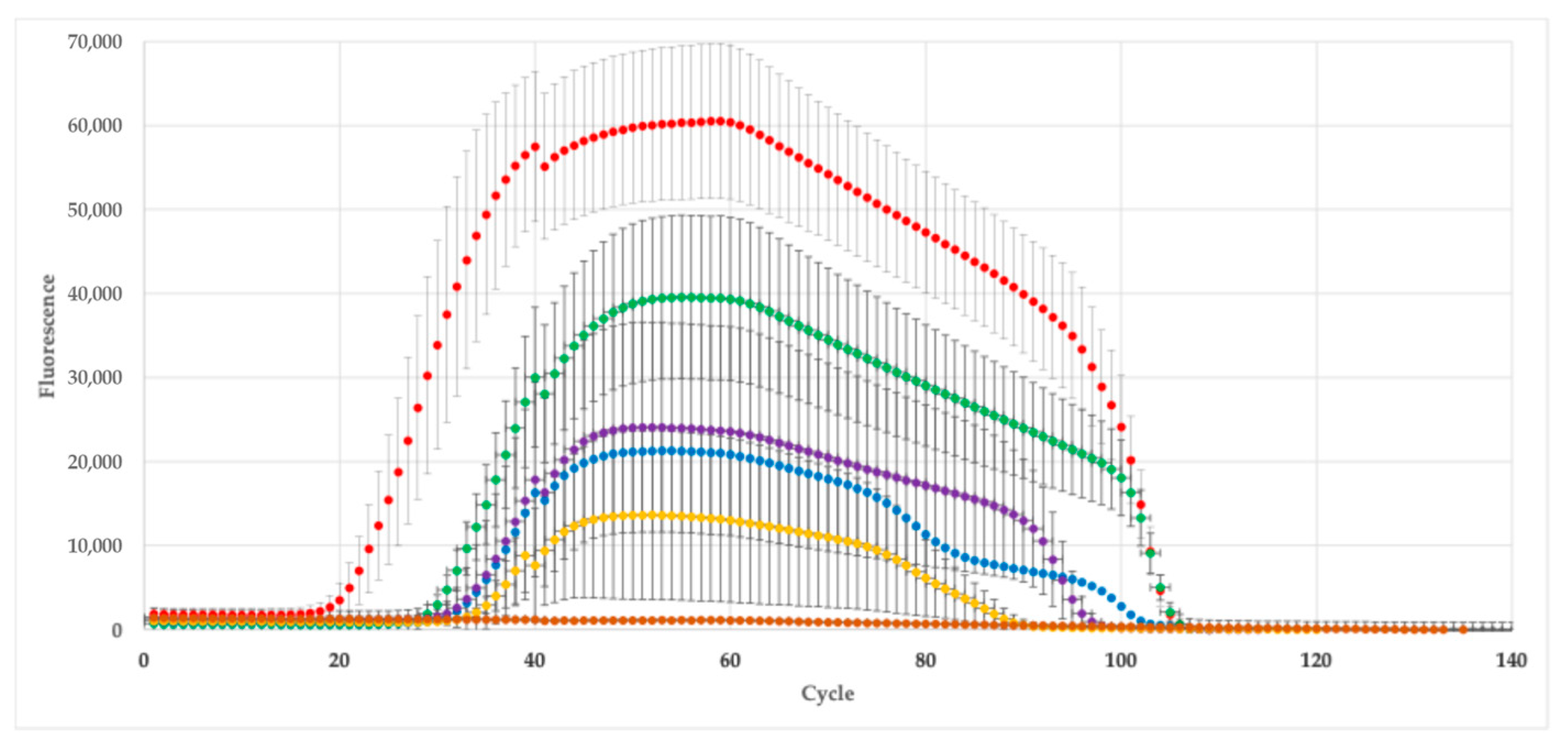

3.1. RNA Extraction and Quality

3.2. Expression of Key Gens on Aloe vera Under Saline–Water Stress

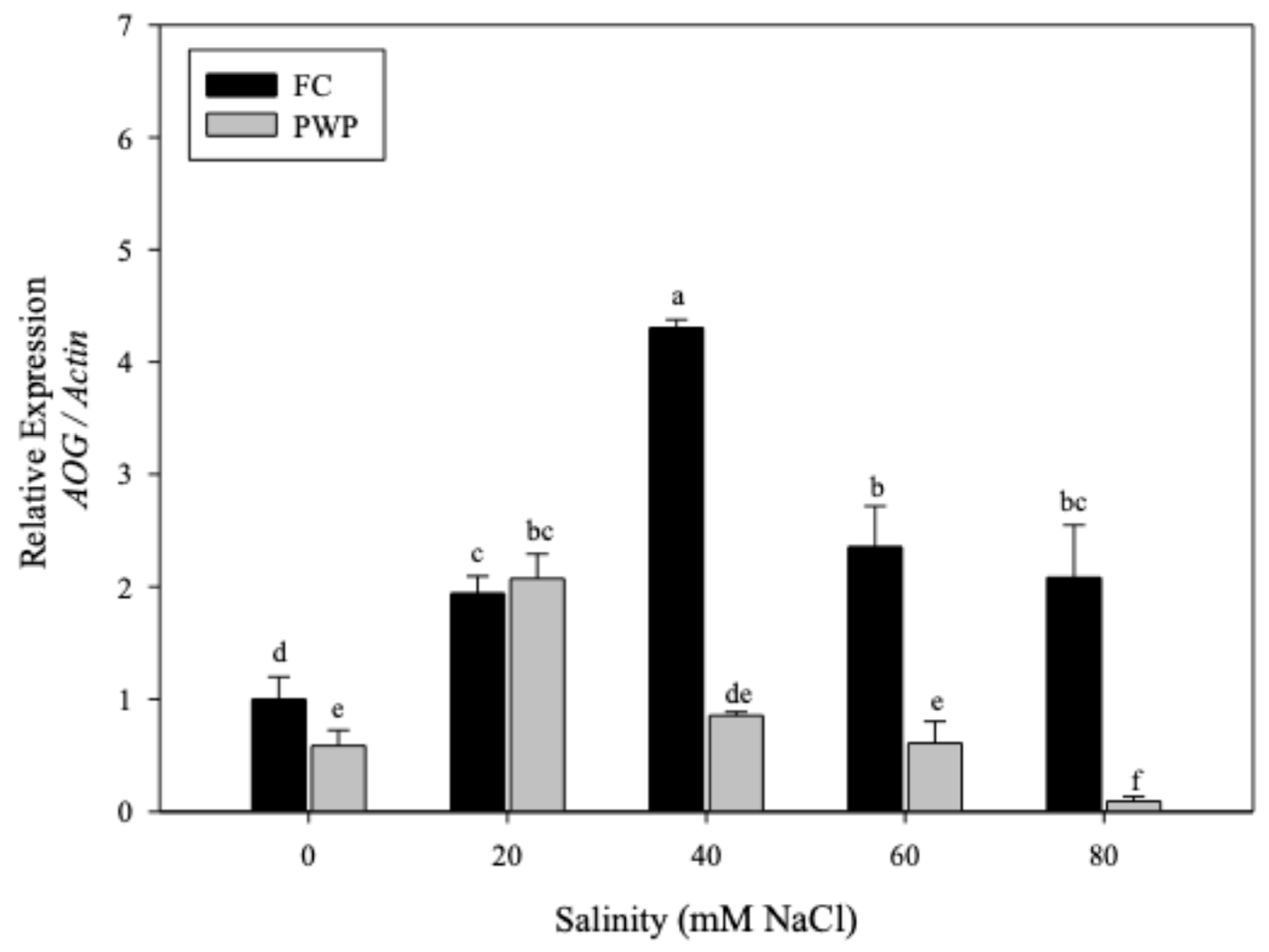

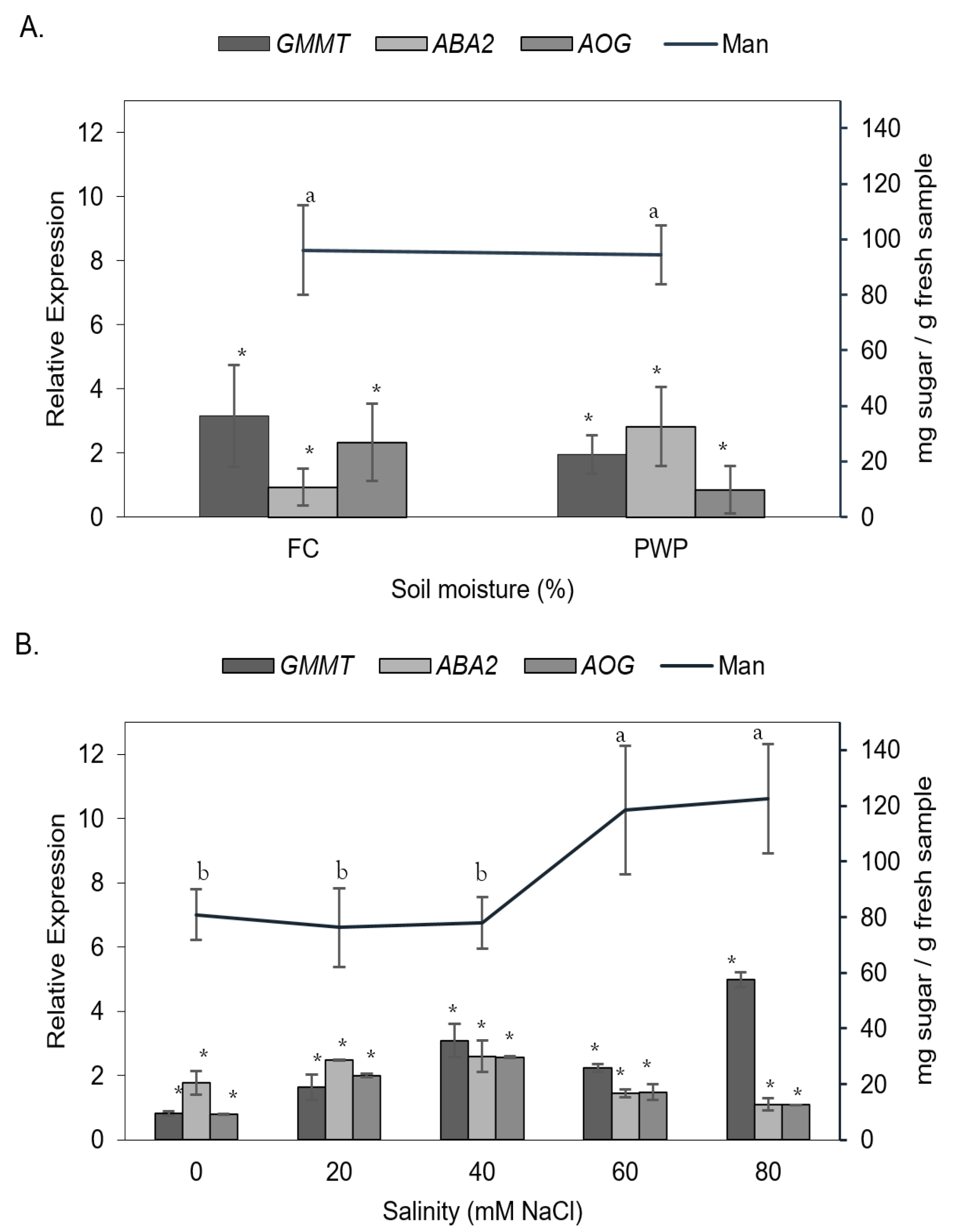

3.2.1. Expression of AOG in Aloe vera Under Saline–Water Stress

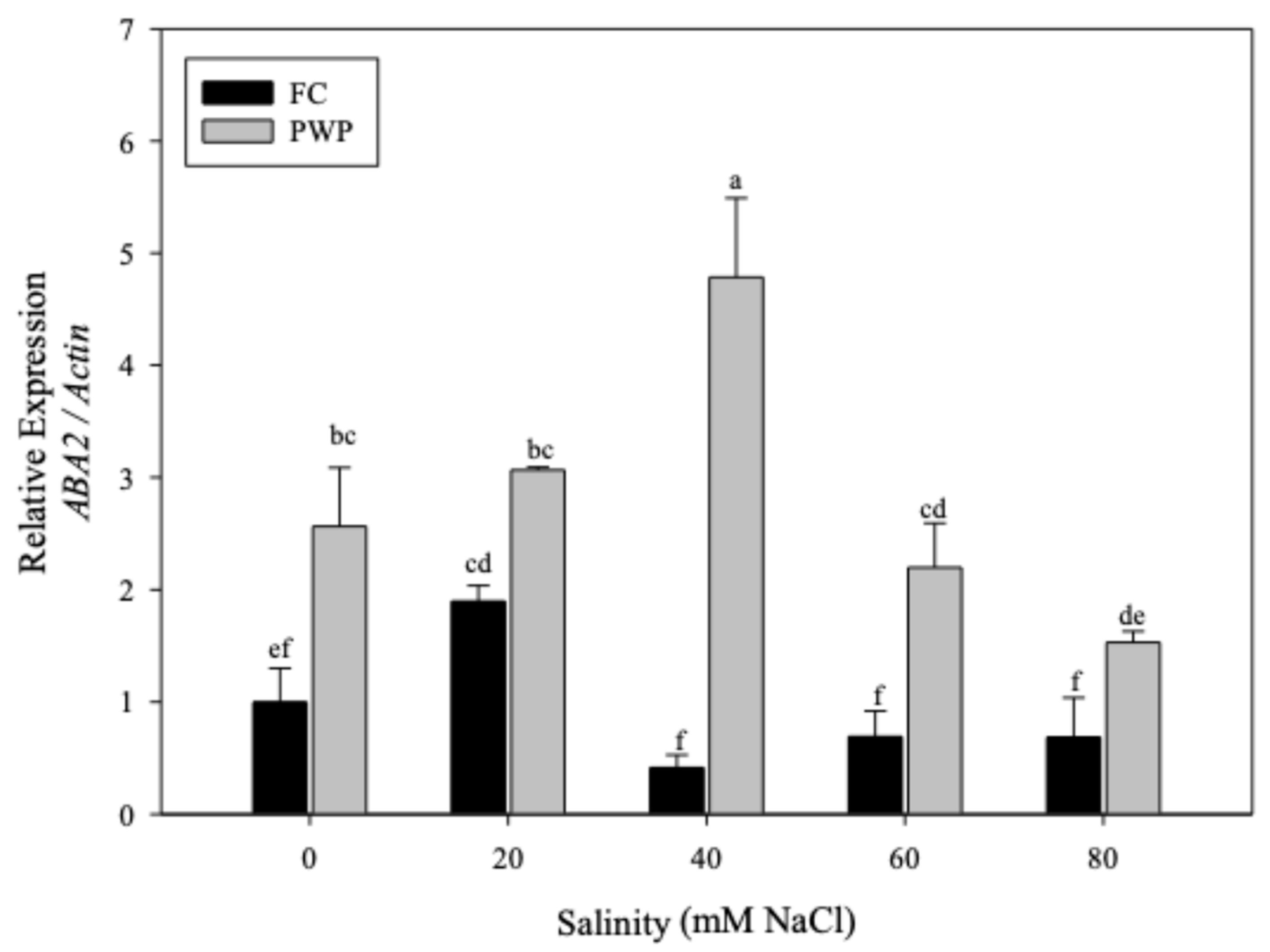

3.2.2. Expression of ABA2 in Aloe vera Under Saline–Water Stress

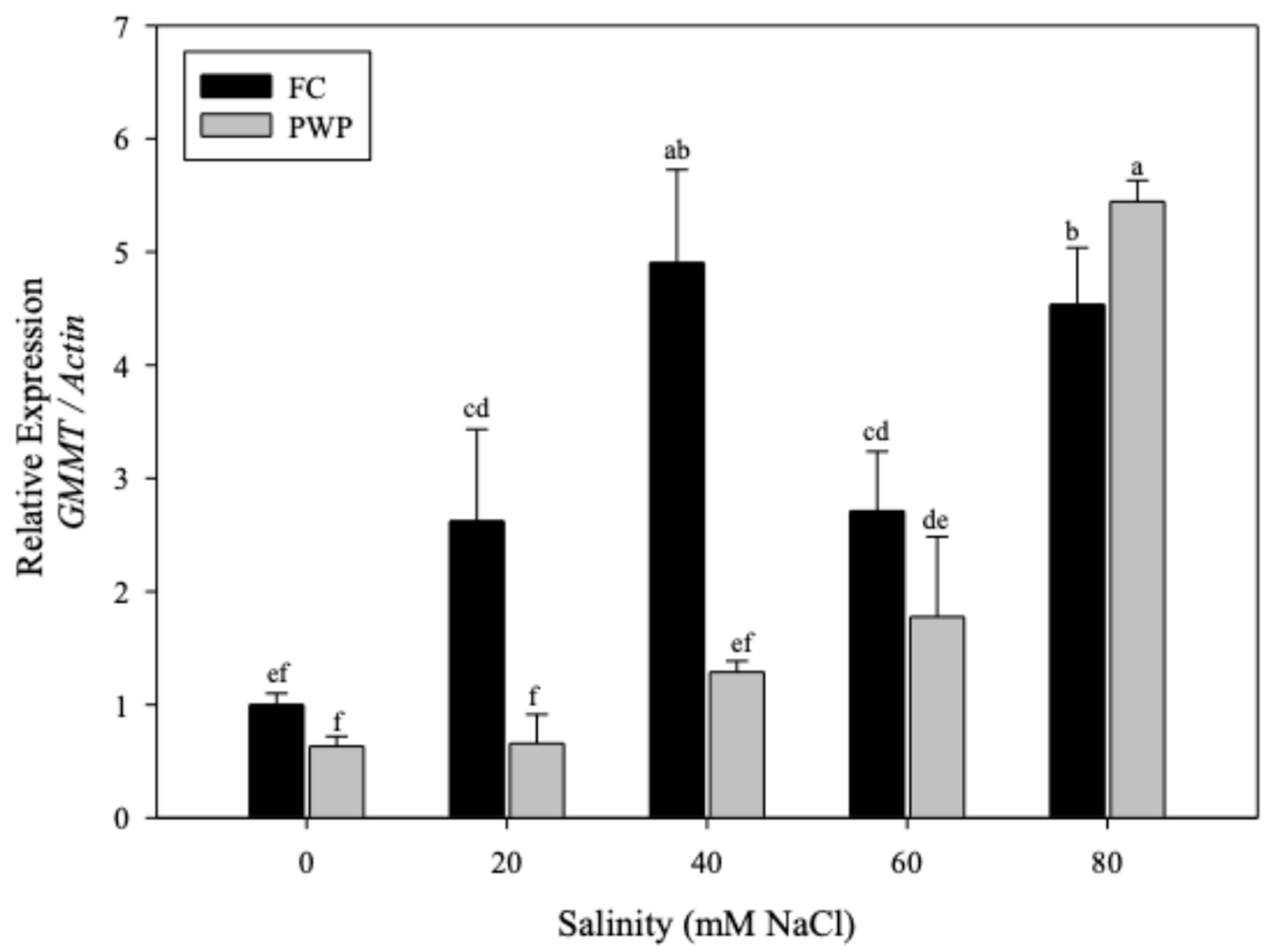

3.2.3. Expression of GMMT in Aloe vera Under Saline–Water Stress

3.3. Effect of Salinity and Water Stress on Gene Expression

3.4. Biosynthesis of Mannose-Rich Polysaccharides in Aloe vera

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Saharan, B.S.; Brar, B.; Duhan, J.S.; Kumar, R.; Marwaha, S.; Rajput, V.D.; Minkina, T. Molecular and physiological mechanisms to mitigate abiotic stress conditions in plants. Life 2022, 12, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mota-Ituarte, M.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Trejo-Calzada, R.; Zegbe, J.A.; Quezada-Rivera, J.J. Water deficit and salinity modify some morphometric, physiological, and productive attributes of Aloe vera (l.). Bot. Sci. 2023, 101, 463–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delatorre-Castillo, J.P.; Delatorre-Herrera, J.; Lay, K.S.; Arenas-Charlín, J.; Sepúlveda-Soto, I.; Cardemil, L.; Ostria-Gallardo, E. Preconditioning to water deficit helps aloe vera to overcome long-term drought during the driest season of atacama desert. Plants 2022, 11, 1523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derouiche, M.; Chkird, F.; Alla, A.; Hamdaoui, H.; Ouahhoud, S.; Benabess, R.; Mzabri, I.; Berrichi, A.; Younous, Y.A.; Badhe, P.; et al. Comparative study of the effect of water stress on morphological, physiological and biochemical parameters of three aloe species. Cogent Food Agric. 2025, 11, 2496691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, P.; Salinas, C.; Contreras, R.A.; Zuñiga, G.E.; Dupree, P.; Cardemil, L. Water deficit and abscisic acid treatments increase the expression of a glucomannan mannosyltransferase gene (GMMT) in Aloe vera burm. F. Phytochemistry 2019, 159, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salinas, C.; Handford, M.; Pauly, M.; Dupree, P.; Cardemil, L. Structural modifications of fructans in Aloe barbadensis Miller (aloe vera) grown under water stress. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0159819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Medina-Torres, L.; González-Laredo, R.F.; Rodríguez-González, V.M.; Eim, V.; Femenia, A. Influence of water deficit on the main polysaccharides and the rheological properties of Aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) mucilage. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 109, 644–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Delgado, M.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Mota-Ituarte, M.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Comas-Serra, F.; Quezada-Rivera, J.J.; Sáenz-Esqueda, Á.; Femenia, A. Joint water and salinity stresses increase the bioactive compounds of aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) gel enhancing its related functional properties. Agric. Water Manag. 2023, 285, 108374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Comas-Serra, F.; Miró, J.L.; Umaña, M.M.; Minjares-Fuentes, R.; Femenia, A.; Mota-Ituarte, M.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A. Role of acemannan and pectic polysaccharides in saline-water stress tolerance of aloe vera (Aloe barbadensis Miller) plant. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delatorre-Herrera, J.; Delfino, I.; Salinas, C.; Silva, H.; Cardemil, L. Irrigation restriction effects on water use efficiency and osmotic adjustment in aloe vera plants (Aloe barbadensis Miller). Agric. Water Manag. 2010, 97, 1564–1570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahi, T.S.; Singh, K.; Singh, B. Screening of sodicity tolerance in aloe vera: An industrial crop for utilization of sodic lands. Ind. Crops Prod. 2013, 44, 528–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaiswal, S.K.; Mahajan, S.; Chakraborty, A.; Kumar, S.; Sharma, V.K. The genome sequence of aloe vera reveals adaptive evolution of drought tolerance mechanisms. iScience 2021, 24, 102079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, K.M.; Thu, S.W.; Balasubramanian, V.K.; Cobos, C.J.; Disasa, T.; Mendu, V. Identification, characterization, and expression analysis of cell wall related genes in Sorghum bicolor (L.) moench, a food, fodder, and biofuel crop. Fron. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagar, S.; Singh, A. Abscisic acid, a principal regulator of plant abiotic stress responses. In Plant Signaling Molecules; Khan, M.I.R., Reddy, P.S., Ferrante, A., Khan, N.A., Eds.; Woodhead Publishing: England, UK, 2019; pp. 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, S.; Li, L.; Sun, Y.-H.; Chiang, V.L. The cellulose synthase gene superfamily and biochemical functions of xylem-specific cellulose synthase-like genes in populus trichocarpa. Plant Physiol. 2006, 142, 1233–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.-J.; Nakajima, M.; Suzuki, Y.; Yamaguchi, I. Cloning and characterization of the abscisic acid-specific glucosyltransferase gene from adzuki bean seedlings. Plant Physiol. 2002, 129, 1285–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmad, F.; Singh, A.; Kamal, A. Osmoprotective role of sugar in mitigating abiotic stress in plants. In Protective Chemical Agents in the Amelioration of Plant Abiotic Stress; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020; pp. 53–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-García, R.; Rodríguez, D.J.d.; Gil-Marín, J.A.; Angulo-Sánchez, J.L.; Lira-Saldivar, R.H. Growth, stomatal resistance, and transpiration of aloe vera under different soil water potentials. Ind. Crops Prod. 2007, 25, 123–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oyebamiji, Y.O.; Adigun, B.A.; Shamsudin, N.A.A.; Ikmal, A.M.; Salisu, M.A.; Malike, F.A.; Lateef, A.A. Recent advancements in mitigating abiotic stresses in crops. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin-Woo, H.; Eun-Kyung, K.; Yon-Suk, K.; Jae Woong, L.; Jeong-Jun, L.; Han-Jong, P.; Sang-Ho, M.; Byong-Tae, J.; Pyo-Jam, P. Growth period effects on the protective properties of aloe vera against t-bhp-induced oxidative stress in chang cells. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015, 25, 2072–2081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ullah, M.; Rasheed, M.; Mohmood, I. Aloe vera (Aloe barbadeenis Mill) screen at suitable salinity and sodicity level. Hortic. Int. J 2018, 2, 365–367. [Google Scholar]

- Sifuentes-Rodriguez, N.S.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Zegbe, J.A.; Trejo-Calzada, R. Indicadores de productividad y calidad de gel de sábila en condiciones de estrés salino. Rev. Fitotec. Mex. 2020, 43, 181–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo-Amador, B.; Nieto-Garibay, A.; Troyo-Diéguez, E.; García-Hernández, J.L.; Hernández-Montiel, L.; Valdez-Cepeda, R.D. Moderate salt stress on the physiological and morphometric traits of aloe vera l. Bot. Sci. 2015, 93, 639–648. [Google Scholar]

- Derouiche, M.; Mzabri, I.; Ouahhoud, S.; Dehmani, I.; Benabess, R.; Addi, M.; Hano, C.; Boukroute, A.; Berrichi, A.; Kouddane, N. The effect of salt stress on the growth and development of three aloe species in eastern morocco. Plant Stress 2023, 9, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-González, M. Expresión Génica como Indicador de Viviparidad en Nogal Pecanero (Carya illinoinensis [wangenh.] k. Koch); Universidad Autónoma Chapingo: Texcoco, Mexico, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Schmittgen, T.D.; Livak, K.J. Analyzing real-time pcr data by the comparative ct method. Nat. Protoc. 2008, 3, 1101–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakraborty, R.; Rehman, R.U.; Siddiqui, M.W.; Liu, H.; Seth, C.S. Phytohormones: Heart of plants’ signaling network under biotic, abiotic, and climate change stresses. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 223, 109839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavi Kishor, P.B.; Tiozon, R.N.; Fernie, A.R.; Sreenivasulu, N. Abscisic acid and its role in the modulation of plant growth, development, and yield stability. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 1283–1295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banerjee, A.; Roychoudhury, A. Abscisic-acid-dependent basic leucine zipper (bzip) transcription factors in plant abiotic stress. Protoplasma 2017, 254, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audran, C.; Borel, C.; Frey, A.; Sotta, B.; Meyer, C.; Simonneau, T.; Marion-Poll, A. Expression studies of the zeaxanthin epoxidase gene in Nicotiana plumbaginifolia. Plant Physiol. 1998, 118, 1021–1028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Audran, C.; Liotenberg, S.; Gonneau, M.; North, H.; Frey, A.; Tap-Waksman, K.; Vartanian, N.; Marion-Poll, A. Localisation and expression of zeaxanthin epoxidase mrna in arabidopsis in response to drought stress and during seed development. Aust. J. Plant Physiol. 2001, 28, 1161–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrero, J.M.; Piqueras, P.; González-Guzmán, M.; Serrano, R.; Rodríguez, P.L.; Ponce, M.R.; Micol, J.L. A mutational analysis of the aba1 gene of Arabidopsis thaliana highlights the involvement of aba in vegetative development. J. Exp. Bot. 2005, 56, 2071–2083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Gene | Encoded Enzyme | Primer Sequence | Melting Temperature (°C) | Amplicon Size (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABA 8H-F | Abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase | 5′-GAGAGAGAGAGGTGCTACATTTG-3′ | 54.0 | 206.0 | [25] |

| ABA 8H-R | 5′-ATGTTTGGGTCTTGAGAGTAGAG-3′ | ||||

| ZEP-F | Zeaxanthin epoxidase | 5′-GAAACTTGGGCAAAGGGAATG-3′ | 55.0 | 258.0 | [25] |

| ZEP-R | 5′-CTTGTTGTACCCACCCTGATAG-3′ | ||||

| ABA2-F | Zeaxanthin epoxidase chloroplastic | 5′-GGACAGTACAGAGGTCCAATTC-3′ | 55.0 | 333.0 | [25] |

| ABA2-R | 5′-TCCTCAGCAACCTCCAAATC-3′ | ||||

| AOG-F | Abscisate beta- glucosyltransferase | 5′-GGTGCCCACCCTCTTATTATC-3′ | 54.0 | 277.0 | [25] |

| AOG-R | 5′-AAGGTGAAGGAGGAGGAGAA-3′ | ||||

| GMMT-F | Glucomannan mannosyltransferase | 5′-GTCCAGATCCCCATGTTCAACGAG-3′ | 60.0 | 107.0 | [5] |

| GMMT-R | 5′-CCAACAGAATTGAGAAGGGTGAT-3′ | ||||

| Act-F | Actin | 5′-AGCCGTCGATGATTGGGATG-3′ | 60.0 | 116.0 | [5] |

| Act-R | 5′-CCACTGAGCACAATGTTGCC-3′ |

| GMMT | ABA2 | AOG | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | p | F | p | F | p | |

| Soil moisture level | 36.33 | <0.0001 | 152.14 | <0.0001 | 539.93 | <0.0001 |

| Salinity | 51.83 | <0.0001 | 14.27 | 0.001 | 99.48 | <0.0001 |

| Interaction | 14.82 | <0.0001 | 17.07 | 0.0006 | 96.28 | <0.0001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mota-Ituarte, M.; Quezada-Rivera, J.J.; Pedroza-Sandoval, A.; Sáenz-Mata, J.; Minjares-Fuentes, R. Key Genes Involved in the Saline–Water Stress Tolerance of Aloe vera. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121000

Mota-Ituarte M, Quezada-Rivera JJ, Pedroza-Sandoval A, Sáenz-Mata J, Minjares-Fuentes R. Key Genes Involved in the Saline–Water Stress Tolerance of Aloe vera. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121000

Chicago/Turabian StyleMota-Ituarte, María, Jesús Josafath Quezada-Rivera, Aurelio Pedroza-Sandoval, Jorge Sáenz-Mata, and Rafael Minjares-Fuentes. 2025. "Key Genes Involved in the Saline–Water Stress Tolerance of Aloe vera" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121000

APA StyleMota-Ituarte, M., Quezada-Rivera, J. J., Pedroza-Sandoval, A., Sáenz-Mata, J., & Minjares-Fuentes, R. (2025). Key Genes Involved in the Saline–Water Stress Tolerance of Aloe vera. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1000. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121000