Screening of Salivary Biomarkers of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Diabetic Rat Model

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Animal Experiment

2.2. Procedure for Establishing a Diabetic BRONJ Model

2.3. Evaluation of Diabetic Status

2.4. Morphological Analysis

2.5. Histological Analysis

2.6. Saliva Test

2.7. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Establishment of a Diabetes Model

3.2. Changes in Soft Tissue of Extraction Sockets Following ZA Administration in a Diabetes Model

3.3. Changes in Hard Tissue of the Extraction Socket Following ZA Administration in a Diabetes Model

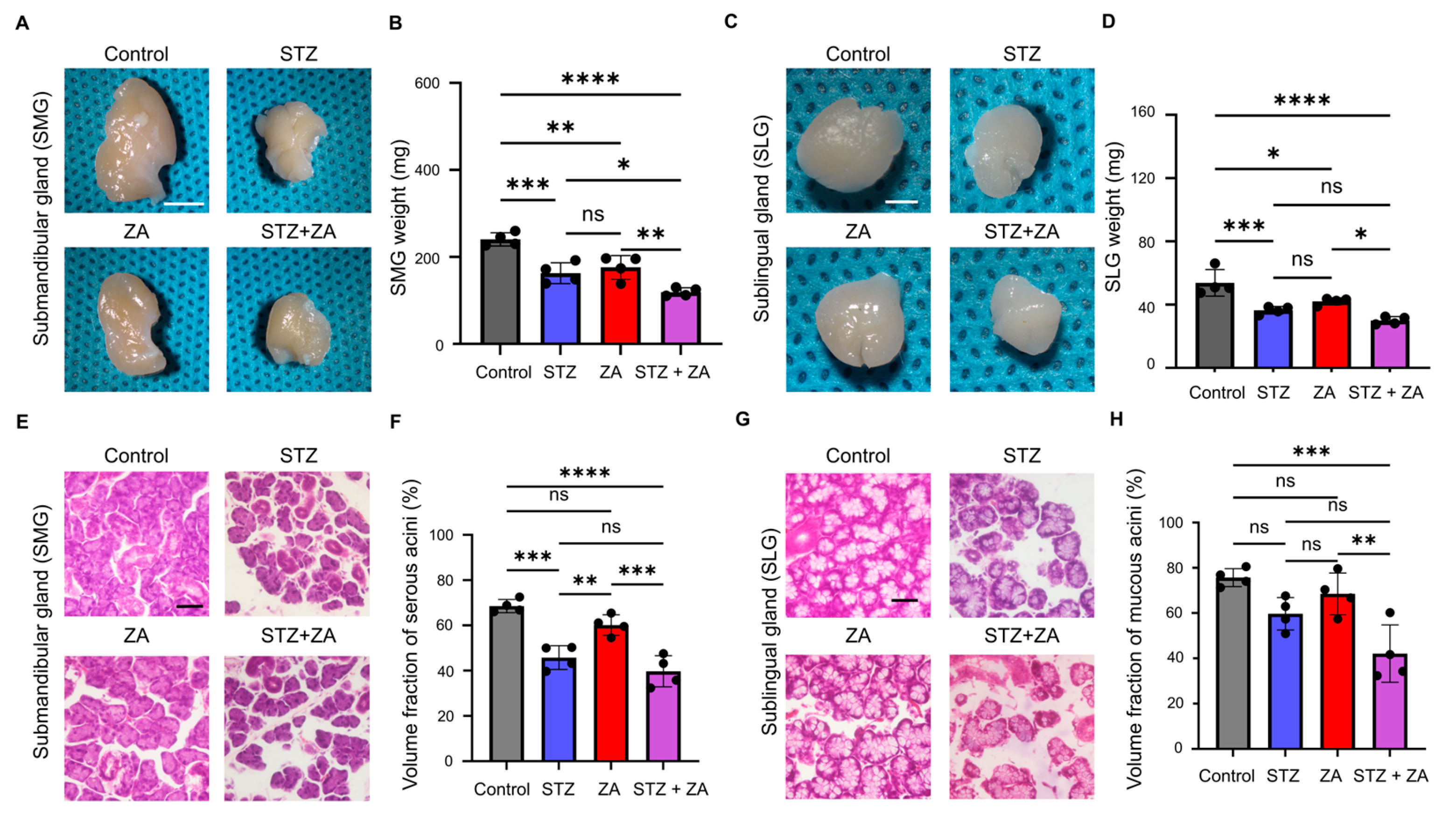

3.4. Changes in SGs Following ZA Administration in a Diabetes Model

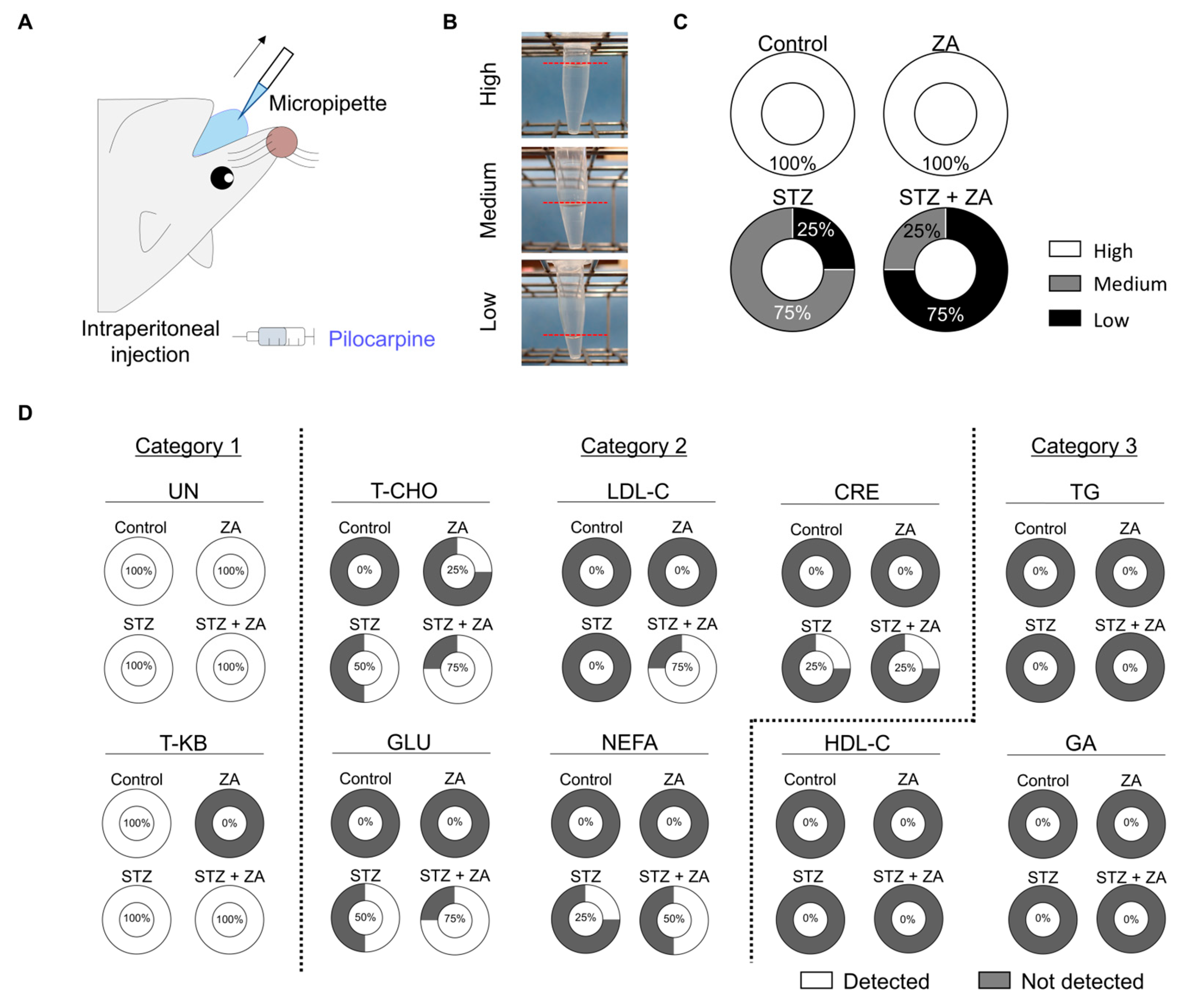

3.5. Changes in Saliva Following ZA Administration in a Diabetes Model

3.6. Second Screening of Saliva Tests

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ANOVA | Analysis of variance |

| BRONJ | Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw |

| BV/TV | Bone volume to total volume ratio |

| CRE | Creatinine |

| EOL | Empty osteocyte lacunae |

| GA | Glycated albumin |

| GLU | Glucose |

| HDL-C | High-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| H-E | Hematoxylin and eosin |

| LDL-C | Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol |

| M1 | Maxillary first molar |

| M2 | Maxillary second molar |

| ND | Not detected |

| NEFA | Non-esterified fatty acids |

| PFA | Paraformaldehyde |

| SD | Standard deviation |

| SGs | Salivary glands |

| SLG | Sublingual gland |

| SMG | Submandibular gland |

| STZ | Streptozotocin |

| Tb.N | Trabecular number |

| TG | Triglyceride |

| T-CHO | Total cholesterol |

| T-KB | Total ketone bodies |

| UN | Urea nitrogen |

| Vv | Volume fraction |

| ZA | Zoledronic acid |

References

- Saeedi, P.; Petersohn, I.; Salpea, P.; Malanda, B.; Karuranga, S.; Unwin, N.; Colagiuri, S.; Guariguata, L.; Motala, A.A.; Ogurtsova, K.; et al. Global and regional diabetes prevalence estimates for 2019 and projections for 2030 and 2045: Results from the international diabetes federation diabetes atlas, 9(th) edition. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2019, 157, 107843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dogruel, H.; Balci, M.K. Development of therapeutic options on type 2 diabetes in years: Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist’s role intreatment; from the past to future. World J. Diabetes 2019, 10, 446–453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adeshara, K.; Di Marco, E.; Bordino, M.; Gordin, D.; Bernardi, L.; Cooper, M.E.; Groop, P.H.; FinnDiane Study Group. Altered oxidant and antioxidant levels are associated with vascular stiffness and diabetic kidney disease in type 1 diabetes after exposure to acute and chronic hyperglycemia. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2024, 23, 350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecerska-Heryc, E.; Engwert, W.; Michalow, J.; Marciniak, J.; Birger, R.; Serwin, N.; Heryc, R.; Polikowska, A.; Goszka, M.; Wojciuk, B.; et al. Oxidative stress markers and inflammation in type 1 and 2 diabetes are affected by BMI, treatment type, and complications. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 23605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Nakagawa, M.; Sumi, Y.; Matsushima, Y.; Uemura, M.; Honda, Y.; Matsumoto, N. Detection of senescent cells in the mucosal healing process on type 2 diabetic rats after tooth extraction for biomaterial development. Dent. Mater. J. 2024, 43, 430–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruggiero, S.L.; Dodson, T.B.; Aghaloo, T.; Carlson, E.R.; Ward, B.B.; Kademani, D. American association of oral and maxillofacial surgeons’ position paper on medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaws-2022 update. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2022, 80, 920–943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tani, M.; Hatano, K.; Yoshimura, A.; Horibe, Y.; Liu, Y.; Sassi, N.; Oka, T.; Okuda, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; Uemura, T.; et al. Cumulative incidence and risk factors for medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw during long-term prostate cancer management. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 13451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frutuoso, F.; Freitas, F.; Vilares, M.; Francisco, H.; Marques, D.; Carames, J.; Moreira, A. Medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review of case reports and case series. Diseases 2024, 12, 205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takaoka, K.; Yamamura, M.; Nishioka, T.; Abe, T.; Tamaoka, J.; Segawa, E.; Shinohara, M.; Ueda, H.; Kishimoto, H.; Urade, M. Establishment of an animal model of bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws in spontaneously diabetic torii rats. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0144355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; Yu, W.; Lee, S.; Xu, Q.; Naji, A.; Le, A.D. Bisphosphonate induces osteonecrosis of the jaw in diabetic mice via nlrp3/caspase-1-dependent il-1beta mechanism. J. Bone Miner. Res. 2015, 30, 2300–2312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thumbigere-Math, V.; Michalowicz, B.S.; de Jong, E.P.; Griffin, T.J.; Basi, D.L.; Hughes, P.J.; Tsai, M.L.; Swenson, K.K.; Rockwell, L.; Gopalakrishnan, R. Salivary proteomics in bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Oral Dis. 2015, 21, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I.; Bravo, S.B.; Carballo, J.; Chantada-Vazquez, M.D.P.; Bagan, J.; Bagan, L.; Chamorro-Petronacci, C.M.; Conde-Amboage, M.; Lopez-Lopez, R.; Garcia-Garcia, A.; et al. Quantitative proteomics in medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A proof-of-concept study. Oral Dis. 2023, 29, 2117–2129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Suryani, I.R.; Ahmadzai, I.; That, M.T.; Shujaat, S.; Jacobs, R. Are medication-induced salivary changes the culprit of osteonecrosis of the jaw? A systematic review. Front. Med. 2023, 10, 1164051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghio, C.; Gravier-Dumonceau, R.; Lafforgue, P.; Giorgi, R.; Pham, T. Identifying a predictive level of serum c-terminal telopeptide associated with a low risk of medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw secondary to oral surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0318260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, S.; Park, M.; Hwang, H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, J.W.; Lee, H.J. Comprehensive profiling of plasma and exosomal micrornas in medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 37333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lorenzo-Pouso, A.I.; Perez-Sayans, M.; Gonzalez-Palanca, S.; Chamorro-Petronacci, C.; Bagan, J.; Garcia-Garcia, A. Biomarkers to predict the onset of biphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaw: A systematic review. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal 2019, 24, e26–e36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kammerhofer, G.; Vegh, D.; Banyai, D.; Vegh, A.; Joob-Fancsaly, A.; Hermann, P.; Geczi, Z.; Hegedus, T.; Somogyi, K.S.; Bencze, B.; et al. Association between hyperglycemia and medication-related osteonecrosis of the jaw (mronj). J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 2976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Kawamoto, A.; Nakagawa, M.; Honda, Y.; Takahashi, K. Cmpk2 gene and protein expression in saliva or salivary glands of dyslipidemic mice. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 12004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarf, E.A.; Bel’skaya, L.V. Salivary bcaa, glutamate, glutamine and urea as potential indicators of nitrogen metabolism imbalance in breast cancer. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samodova, D.; Stankevic, E.; Sondergaard, M.S.; Hu, N.; Ahluwalia, T.S.; Witte, D.R.; Belstrom, D.; Lubberding, A.F.; Jagtap, P.D.; Hansen, T.; et al. Salivary proteomics and metaproteomics identifies distinct molecular and taxonomic signatures of type-2 diabetes. Microbiome 2025, 13, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Relvas, M.; Mendes-Frias, A.; Goncalves, M.; Salazar, F.; Lopez-Jarana, P.; Silvestre, R.; Viana da Costa, A. Salivary il-1beta, il-6, and il-10 are key biomarkers of periodontitis severity. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 8401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poimenidou, A.A.; Geraki, P.; Davidopoulou, S.; Kalfas, S.; Arhakis, A. Oxidative stress and salivary physicochemical characteristics relative to dental caries and restorative treatment in children. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahmad, M.M.; Hassan, H.A.; Saadawy, S.F.; Ahmad, E.A.; Elsawy, N.A.M.; Morsy, M.M. Antox targeting age/rage cascades to restore submandibular gland viability in rat model of type 1 diabetes. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 18160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aihara, M.; Yano, K.; Irie, T.; Nishi, M.; Yachiku, K.; Minoura, I.; Sekimizu, K.; Sakurai, Y.; Kadowaki, T.; Yamauchi, T.; et al. Salivary glycated albumin could be as reliable a marker of glycemic control as blood glycated albumin in people with diabetes. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2024, 218, 111903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teles, F.R.F.; Chandrasekaran, G.; Martin, L.; Patel, M.; Kallan, M.J.; Furquim, C.; Hamza, T.; Cucchiara, A.J.; Kantarci, A.; Urquhart, O.; et al. Salivary and serum inflammatory biomarkers during periodontitis progression and after treatment. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2024, 51, 1619–1631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Furman, B.L. Streptozotocin-induced diabetic models in mice and rats. Curr. Protoc. 2021, 1, e78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Imada, M.; Yagyuu, T.; Ueyama, Y.; Maeda, M.; Yamamoto, K.; Kurokawa, S.; Jo, J.I.; Tabata, Y.; Tanaka, Y.; Kirita, T. Prevention of tooth extraction-triggered bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws with basic fibroblast growth factor: An experimental study in rats. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0211928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbassy, M.A.; Watari, I.; Soma, K. Effect of experimental diabetes on craniofacial growth in rats. Arch. Oral Biol. 2008, 53, 819–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, J.; Koi, K.; Yang, D.Y.; McCauley, L.K. Effect of zoledronate on oral wound healing in rats. Clin. Cancer Res. 2011, 17, 1405–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawamoto, T.; Kawamoto, K. Preparation of Thin Frozen Sections from Nonfixed and Undecalcified Hard Tissues Using Kawamoto’s Film Method. In Skeletal Development and Repair: Methods and Protocols, 2nd ed.; Hilton, M.J., Ed.; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2230, pp. 259–282. [Google Scholar]

- Noorafshan, A. Stereological study on the submandibular gland in hypothyroid rats. APMIS 2001, 109, 223–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rehman, H.U.; Ullah, K.; Rasool, A.; Manzoor, R.; Yuan, Y.; Tareen, A.M.; Kaleem, I.; Riaz, N.; Hameed, S.; Bashir, S. Comparative impact of streptozotocin on altering normal glucose homeostasis in diabetic rats compared to normoglycemic rats. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albasher, G.; Alkahtani, S.; Al-Harbi, L.N. Urolithin A prevents streptozotocin-induced diabetic cardiomyopathy in rats by activating sirt1. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2022, 29, 1210–1220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venuti, M.T.; Roda, E.; Brandalise, F.; Sarkar, M.; Cappelletti, M.; Speciani, A.F.; Soffientini, I.; Priori, E.C.; Giammello, F.; Ratto, D.; et al. A pathophysiological intersection between metabolic biomarkers and memory: A longitudinal study in the stz-induced diabetic mouse model. Front. Physiol. 2025, 16, 1455434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- AlZeer, I.; AlBassam, A.M.; AlFeraih, A.; AlMutairi, A.; AlAskar, B.; Aljasser, D.; AlRashed, F.; Alotaibi, N.; AlGhamdi, S.; AlRashed, Z. Correlation between glycated hemoglobin (hba1c) levels and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus at a tertiary hospital in saudi arabia. Cureus 2025, 17, e80736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuttle, K.R.; Reynolds, C.L.; Kornowske, L.M.; Jones, C.R.; Alicic, R.Z.; Daratha, K.B.; Neumiller, J.J.; Greenbaum, C.; Pavkov, M.E.; Xu, F.; et al. Prevalence and severity of chronic kidney disease in a population with type 1 diabetes from a united states health system: A real-world cohort study. Lancet Reg. Health Am. 2025, 47, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassan, S.S.; Alqahtani, M.S. Early alterations of cytoskeletal proteins induced by radiation therapy in the parenchymal cells of rat major salivary glands: A comparative immunohistochemical analysis. Cureus 2024, 16, e75634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishitani, T.; Mitoh, Y.; Yajima, T.; Tachiya, D.; Hoshika, T.; Fukunaga, T.; Nishitani, Y.; Yoshida, R.; Mizoguchi, I.; Ichikawa, H.; et al. Distribution of alpha-synuclein in rat salivary glands. Anat. Rec. 2024, 307, 2933–2946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashida, M.H.; Da Silva Faria, A.L.; Caldeira, E.J. Estrogen and insulin replacement therapy modulates the expression of insulin-like growth factor-i receptors in the salivary glands of diabetic mice. Anat. Rec. 2011, 294, 1930–1938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, P.; Ebker, T.; Bergauer, J.; Wehrhan, F. Saliva diagnostics in patients suffering from bisphosphonate-associated osteonecrosis of the jaw: Results of an observational study. J. Craniomaxillofac. Surg. 2020, 48, 176–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelaars, S.; Konings, C.; Cox, L.; Boonen, E.; Mischi, M.; Bouwman, R.A.; van de Kerkhof, D. The correlation of urea and creatinine concentrations in sweat and saliva with plasma during hemodialysis: An observational cohort study. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2024, 62, 1118–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaran, R.; Abdalla, M.M.I.; Caszo, B.A.; Somanath, S.D. Saliva urea nitrogen for detection of kidney disease in adults: A meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0324251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kovalcikova, A.G.; Pavlov, K.; Liptak, R.; Hladova, M.; Renczes, E.; Boor, P.; Podracka, L.; Sebekova, K.; Hodosy, J.; Tothova, L.; et al. Dynamics of salivary markers of kidney functions in acute and chronic kidney diseases. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaul, N.; Duan, J.; Cui, D.; Erlichster, M.; Chen, Z.; Anderson, D.; Chan, J.; Scheffer, I.E.; Skafidas, E.; Liao, J.; et al. Serial correlation between saliva and blood beta-hydroxybutyrate levels in children commencing the ketogenic diet for epilepsy. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 3282–3292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Control | STZ | ZA | STZ + ZA | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MEAN | Range | MEAN | Range | MEAN | Range | MEAN | Range | |

| UN (mg/dL) | 11.4 | 9.9–12.3 | 19.6 | 10.6–20.4 | 9.75 | 9.1–10.8 | 27.6 | 11.3–40.3 |

| T-KB (μmol/L) | 8.25 | 3.0–15.0 | 294 | 8.0–482.0 | ND | ND | 419 | 19.0–640.0 |

| T-CHO (mg/dL) | ND | ND | 3 | ND–4.0 | 0.5 | ND–2.0 | 3.7 | ND–6.0 |

| GLU (mg/dL) | ND | ND | 0.5 | ND–2.0 | ND | ND | 2 | ND–3.0 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 1.7 | ND–3.0 |

| NEFA (μEq/L) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 26.4 | ND–105.5 |

| CRE (mg/dL) | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | ND | 0.06 | ND–0.06 |

| Marker | Molecular Weight (Da) | Molecular Formula |

|---|---|---|

| UN (mg/dL) | 60 | CH4N2O |

| T-KB (μmol/L) | 104 | C4H8O3/C4H6O3 |

| T-CHO (mg/dL) | 387 | C27H46O |

| GLU (mg/dL) | 180 | C6H12O6 |

| LDL-C (mg/dL) | ~2.3 × 106 | – |

| NEFA (μEq/L) | 256 | C16H32O2 |

| CRE (mg/dL) | 113 | C4H7N3O |

| HDL-C (mg/dL) | ~3.5 × 105 | – |

| TG (mg/dL) | 885 | C57H104O6 |

| GA (%) | 66,500 | – |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Qin, K.; Nakagawa, M.; Sumi, Y.; Zhang, B.; Uemura, M.; Honda, Y. Screening of Salivary Biomarkers of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Diabetic Rat Model. Curr. Issues Mol. Biol. 2025, 47, 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121002

Qin K, Nakagawa M, Sumi Y, Zhang B, Uemura M, Honda Y. Screening of Salivary Biomarkers of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Diabetic Rat Model. Current Issues in Molecular Biology. 2025; 47(12):1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121002

Chicago/Turabian StyleQin, Ke, Masato Nakagawa, Yoichi Sumi, Baiyan Zhang, Mamoru Uemura, and Yoshitomo Honda. 2025. "Screening of Salivary Biomarkers of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Diabetic Rat Model" Current Issues in Molecular Biology 47, no. 12: 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121002

APA StyleQin, K., Nakagawa, M., Sumi, Y., Zhang, B., Uemura, M., & Honda, Y. (2025). Screening of Salivary Biomarkers of Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaw in a Diabetic Rat Model. Current Issues in Molecular Biology, 47(12), 1002. https://doi.org/10.3390/cimb47121002