Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infects Human Visceral White Adipocytes and Expresses Dormancy Genes and Inflammatory Cytokines: The Role of Visceral Adipocytes in Latent Tuberculosis Infection

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

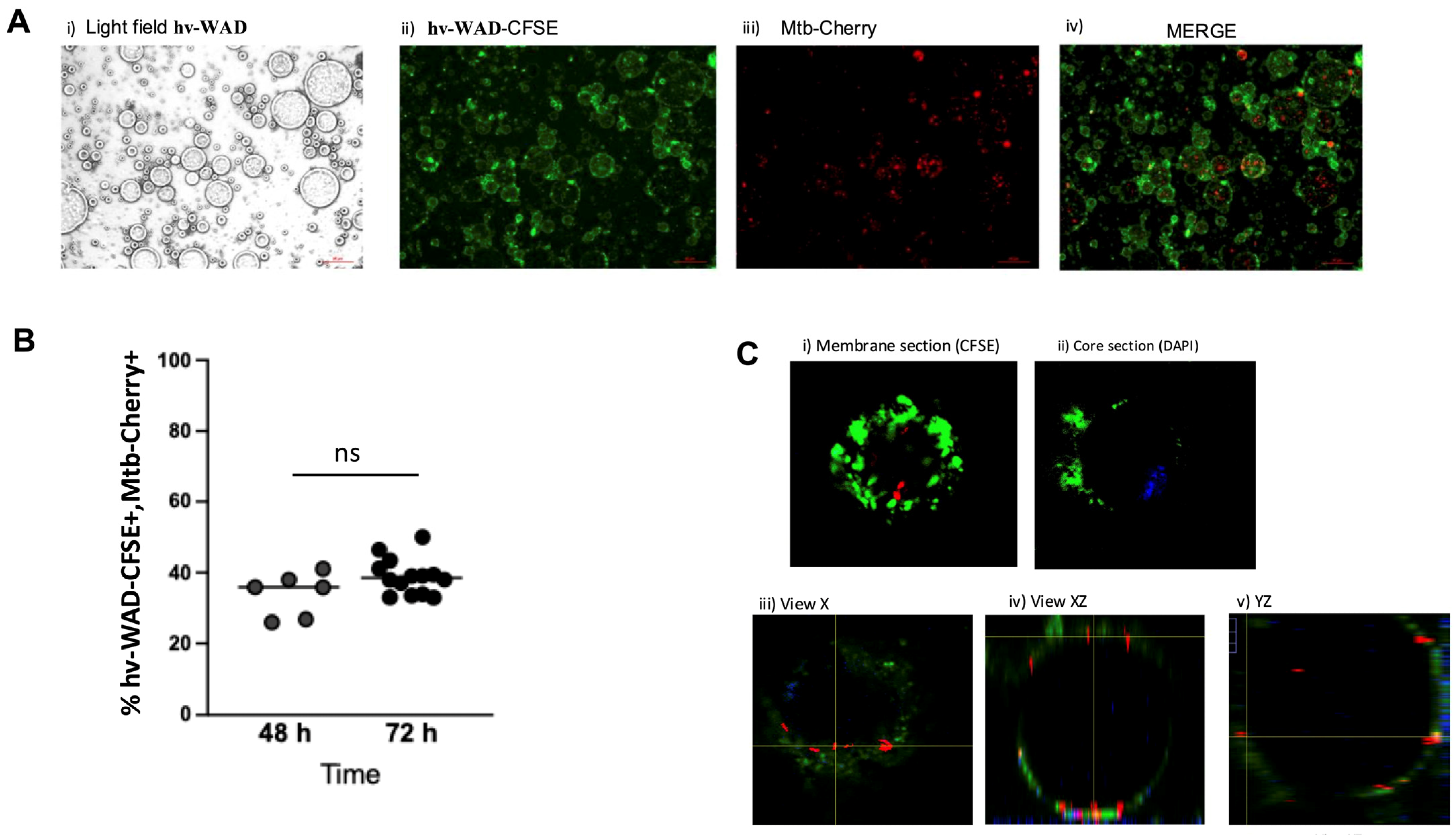

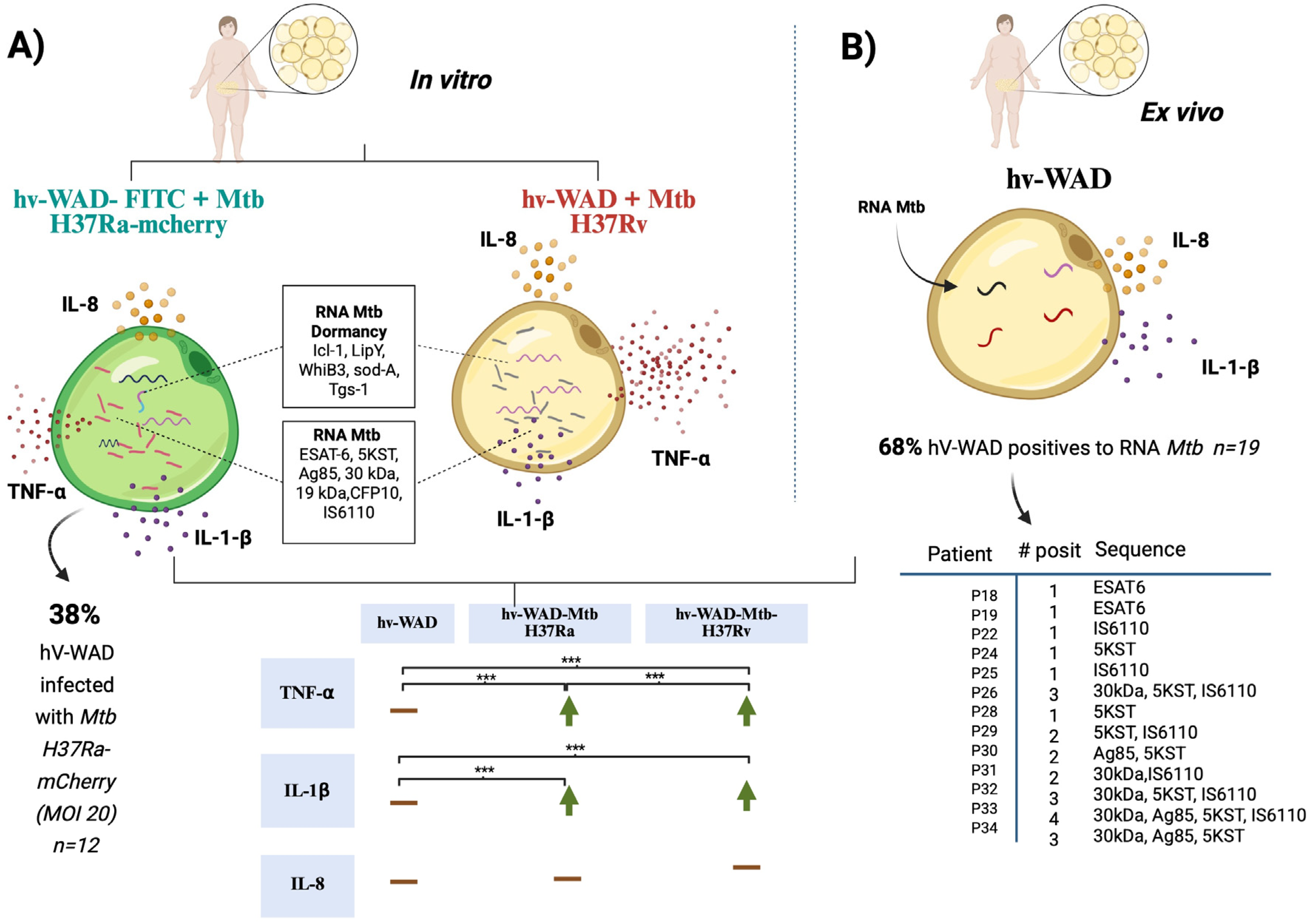

2.1. Mtb Infects hv-WAD Cells

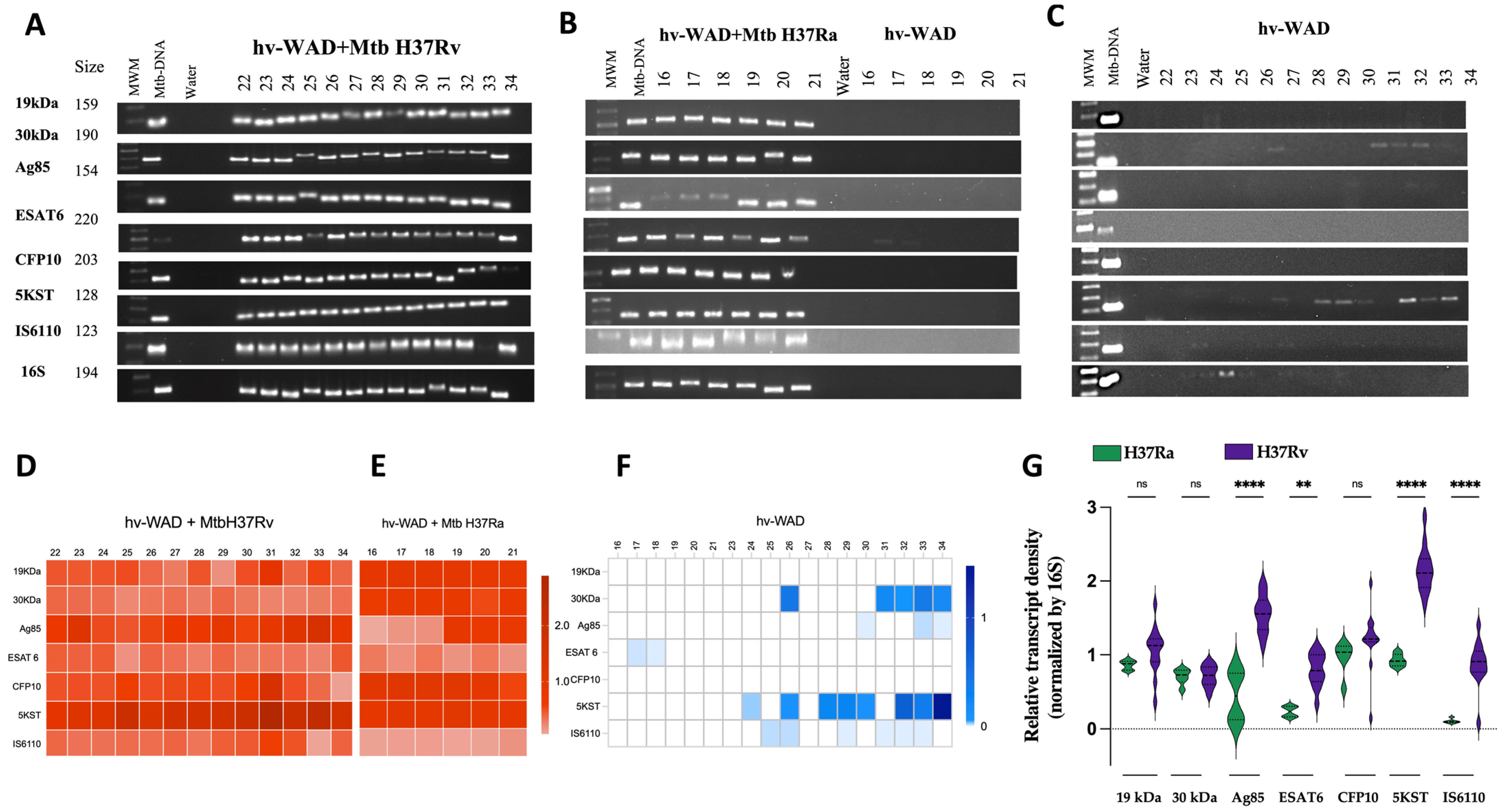

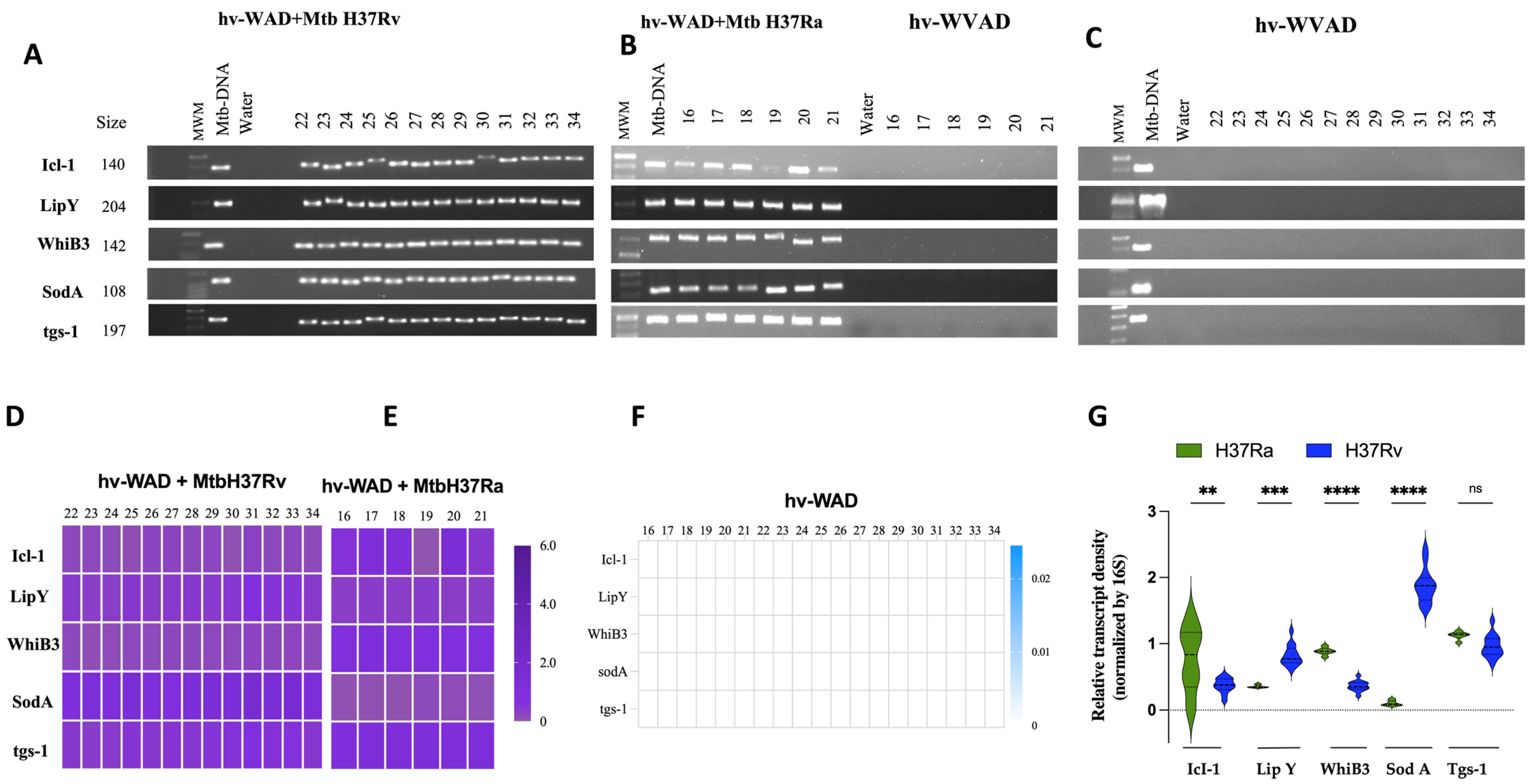

2.2. RNA Transcripts Expressed in hv-WAD

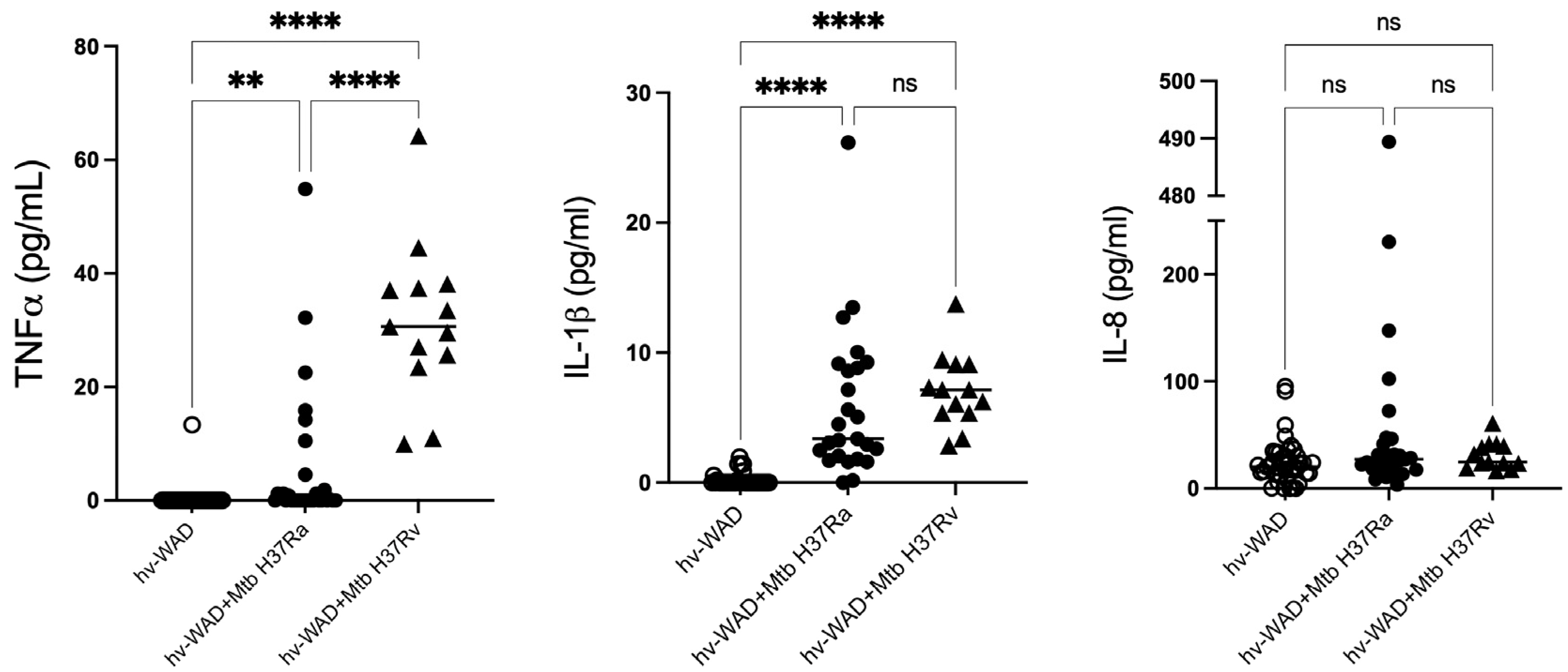

2.3. Proinflammatory Cytokines in Cultures of hv-WAD

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement and Patients

4.2. Human Visceral White Adipocyte Tissue (hv-WAT)

4.3. Fluorescent Staining of hv-WAD

4.4. Mtb-H37Ra-mCherry and Mtb-H37Rv Strains

4.5. Internalization of Mtb-Cherry by hv-WAD

4.6. hv-WAD Infected with Mtb-H37Ra-Cherry or Mtb-H37Rv Strain

4.7. RNA Extraction from hv-WAD

4.8. Amplification of Mtb-RNA in hv-WAD by PCR

4.9. Densitometric Analysis of Gene Amplifications

4.10. Immunoassays for IL-1β, IL-8, and TNF-α

4.11. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pinto, P.F.P.S.; Teixeira, C.S.S.; Ichihara, M.Y.; Rasella, D.; Nery, J.S.; Sena, S.O.L.; Brickley, E.B.; Barreto, M.L.; Sanchez, M.N.; Pescarini, J.M. Incidence and risk factors of tuberculosis among 420 854 household contacts of patients with tuberculosis in the 100 Million Brazilian Cohort (2004–18): A cohort study. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2024, 24, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Houben, R.M.G.J.; Dodd, P.J. The Global Burden of Latent Tuberculosis Infection: A Re-estimation Using Mathematical Modelling. PLoS Med. 2016, 13, e1002152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cohen, A.; Mathiasen, V.D.; Schön, T.; Wejse, C. The global prevalence of latent tuberculosis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur. Respir. J. 2019, 54, 1900655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Report 2024; Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Ehlers, S. Lazy, dynamic or minimally recrudescent? on the elusive nature and location of the Mycobacterium responsible for latent tuberculosis. Infection 2009, 37, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez-González, L.H.; Juárez, E.; Carranza, C.; Carreto-Binaghi, L.E.; Alejandre, A.; Cabello-Gutiérrrez, C.; Gonzalez, Y. Immunological aspects of diagnosis and management of childhood tuberculosis. Infect. Drug Resist. 2021, 14, 929–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.-S.; Ryu, M.-J.; Byun, E.-H.; Kim, W.S.; Whang, J.; Min, K.-N.; Shong, M.; Kim, H.-J.; Shin, S.J. Differential immune response of adipocytes to virulent and attenuated Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Microbes Infect. 2011, 13, 1242–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neyrolles, O.; Hernández-Pando, R.; Pietri-Rouxel, F.; Fornès, P.; Tailleux, L.; Payán, J.A.B.; Pivert, E.; Bordat, Y.; Aguilar, D.; Prévost, M.-C.; et al. Is adipose tissue a place for Mycobacterium tuberculosis persistence? PLoS ONE 2006, 1, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry Boom, W.; Schaible, U.E.; Achkar, J.M. The knowns and unknowns of latent Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e136222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wayne, L.G.; Sohaskey, C.D. Nonreplicating persistence of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 2001, 55, 139–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torrelles, J.B.; Schlesinger, L.S. Integrating Lung Physiology, Immunology, and Tuberculosis. Trends Microbiol. 2017, 25, 688–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayyappan, J.P.; Ganapathi, U.; Lizardo, K.; Vinnard, C.; Subbian, S.; Perlin, D.S.; Nagajyothi, J.F. Adipose tissue regulates pulmonary pathology during TB infection. mBio 2019, 10, e02771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayyappan, J.P.; Vinnard, C.; Subbian, S.; Nagajyothi, J.F. Effect of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection on adipocyte physiology. Microbes Infect. 2018, 20, 81–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agarwal, P.; Gordon, S.; Martinez, F.O. Foam Cell Macrophages in Tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 775326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van der Klugt, T.; van den Biggelaar, R.H.G.A.; Saris, A. Host and bacterial lipid metabolism during tuberculosis infections: Possibilities to synergise host- and bacteria-directed therapies. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2025, 51, 463–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinton, M.C.; Kajimura, S. From fat storage to immune hubs: The emerging role of adipocytes in coordinating the immune response to infection. FEBS J. 2025, 292, 1868–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gengenbacher, M.; Kaufmann, S.H.E. Mycobacterium tuberculosis: Success through dormancy. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012, 36, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, D.J.; Brown, J.R. Identification of gene targets against dormant phase Mycobacterium tuberculosis infections. BMC Infect. Dis. 2007, 7, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beigier-Bompadre, M.; Montagna, G.N.; Kühl, A.A.; Lozza, L.; Weiner, J.; Kupz, A.; Vogelzang, A.; Mollenkopf, H.-J.; Löwe, D.; Bandermann, S.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection modulates adipose tissue biology. PLoS Pathog. 2017, 13, e1006676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solovic, I.; Sester, M.; Gomez-Reino, J.J.; Rieder, H.L.; Ehlers, S.; Milburn, H.J.; Kampmann, B.; Hellmich, B.; Groves, R.; Schreiber, S.; et al. The risk of tuberculosis related to tumour necrosis factor antagonist therapies: A TBNET consensus statement. Eur. Respir. J. 2010, 36, 1185–1206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Banaiee, N.; Jacobs, W.R.; Ernst, J.D. Regulation of Mycobacterium tuberculosis whiB3 in the mouse lung and macrophages. Infect. Immun. 2006, 74, 6449–6457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Geiman, D.E.; Raghunand, T.R.; Agarwal, N.; Bishai, W.R. Differential gene expression in response to exposure to antimycobacterial agents and other stress conditions among seven Mycobacterium tuberculosis whiB-like genes. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 2836–2841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikitushkin, V.; Shleeva, M.; Loginov, D.; Dycka, F.; Sterba, J.; Kaprelyants, A. Shotgun proteomic profiling of dormant, “nonculturable” Mycobacterium tuberculosis. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0269847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neshani, A.; Kakhki, R.K.; Sankian, M.; Zare, H.; Chichaklu, A.H.; Sayyadi, M.; Ghazvini, K. Modified genome comparison method: A new approach for identification of specific targets in molecular diagnostic tests using Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex as an example. BMC Infect. Dis. 2018, 18, 517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreejit, G.; Ahmed, A.; Parveen, N.; Jha, V.; Valluri, V.L.; Ghosh, S.; Mukhopadhyay, S. The ESAT-6 Protein of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Interacts with Beta-2-Microglobulin (β2M) Affecting Antigen Presentation Function of Macrophage. PLoS Pathog. 2014, 10, e1004446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Renshaw, P.S.; Lightbody, K.L.; Veverka, V.; Muskett, F.W.; Kelly, G.; Frenkiel, T.A.; Gordon, S.V.; Hewinson, R.G.; Burke, B.; Norman, J.; et al. Structure and function of the complex formed by the tuberculosis virulence factors CFP-10 and ESAT-6. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 2491–2498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huygen, K. The immunodominant T-cell epitopes of the mycolyl-transferases of the antigen 85 complex of M. tuberculosis. Front. Immunol. 2014, 5, 321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haas, M.K.; Belknap, R.W. Diagnostic Tests for Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Clin. Chest Med. 2019, 40, 829–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Brizuela, E.; Apriani, L.; Mukherjee, T.; Lachapelle-Chisholm, S.; Miedy, M.; Lan, Z.; Korobitsyn, A.; Ismail, N.; Menzies, D. Assessing the Diagnostic Performance of New Commercial Interferon-γ Release Assays for Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2023, 76, 1989–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robert, M.; Miossec, P. Reactivation of latent tuberculosis with TNF inhibitors: Critical role of the beta 2 chain of the IL-12 receptor. Cell Mol. Immunol. 2021, 18, 1644–1651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zainabadi, K.; Lee, M.H.; Walsh, K.F.; Vilbrun, S.C.; Mathurin, L.D.; Ocheretina, O.; Pape, J.W.; Fitzgerald, D.W. An optimized method for purifying, detecting and quantifying Mycobacterium tuberculosis RNA from sputum for monitoring treatment response in TB patients. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 17382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rustad, T.R.; Roberts, D.M.; Liao, R.P.; Sherman, D.R. Isolation of mycobacterial RNA. In Mycobacteria Protocols; Methods in Molecular Biology; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2008; Volume 465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carroll, P.; Schreuder, L.J.; Muwanguzi-Karugaba, J.; Wiles, S.; Robertson, B.D.; Ripoll, J.; Ward, T.H.; Bancroft, G.J.; Schaible, U.E.; Parish, T. Sensitive detection of gene expression in mycobacteria under replicating and non-replicating conditions using optimized far-red reporters. PLoS ONE 2010, 5, e9823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Number | Percentage | |

| Subjects | 54 | ----- |

| Male | 21 | 38.8 |

| Female | 33 | 61.1 |

| Age (18–65) | 41 | ---- |

| Body Mass Index | ||

| Class II obesity (35.0–39.9) | 4 | 7.4 |

| Class III obesity (>39.9) | 40 | 92.6 |

| Type 2 Diabetes | 41 | 75.9 |

| Target | Primer Sequences 5′ | Size (bp) |

|---|---|---|

| 19 kDa | F: GAGACCACGACCGCGGCAGG R: AATGCCGGTCGCCGCCCCGCCGAT | 159 |

| 30 kDa (fbpB) | F: TGTACCAGTCGCTGTAGAAG R: GACATCAAGGTTCAGTTC | 190 |

| Ag85 (fbpC) | F: AAGGTCCAGTTCCAGGGCG R: ATTGGCCGCCCACGGGCATGAT | 154 |

| ESAT6 | F: GTCCATTCATTCCCTCCT R: CTATGCGAACATCCCAGT | 220 |

| CFP10 | F: GGATCCATGGCAGAGATGAAGACC R: GGATCCGAAGCCCATTTGCGAGG | 203 |

| 5KST | F: TTGCTGAACTTGACCTGCCCGTA R: GCGTCTCTGCCTTCCTCCGAT | 128 |

| IS6110 | F: CCTGCGAGCGTAGGCGTCGG R: CTCGTCCAGCGCCGCTFCGG | 123 |

| rRNA 16S | F: GCCGTAAACGGTGGGTACTA R: TGCATGTCAAACCCAGGTAA | 194 |

| Icl-1 | F: CGGATCAACAACGCACTGCA R: TTCTGCAGCTCGTAGACGTT | 140 |

| LipY | F: GTATTAGCCGCTGCCGAGGA R: GATACCGCTGGCGAATTCACTCT | 204 |

| WhiB3 | F: TGGACTCATCGATGTTCTTCC R: TAGGGCTCACCGACCTCTAA | 142 |

| SodA | F: ACACCTTGCCAGACCTGGA R: CGCCCTTTACGTAGGTGGC | 108 |

| Tgs-1 | F: AACGAAGACAGTTATTCGAGC R: CTCATACCTTTCATCGGAGAGCC | 197 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Garduño-Torres, A.E.; Salgado-Cantú, M.G.; Guzmán-Beltrán, S.; Montoya-Ramírez, J.; Suárez-Cuenca, J.A.; Ortega, E.; Orozco-Solís, D.R.; Uribe-López, D.I.; Herrera, M.T.; Gutiérrez-González, L.H.; et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infects Human Visceral White Adipocytes and Expresses Dormancy Genes and Inflammatory Cytokines: The Role of Visceral Adipocytes in Latent Tuberculosis Infection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311595

Garduño-Torres AE, Salgado-Cantú MG, Guzmán-Beltrán S, Montoya-Ramírez J, Suárez-Cuenca JA, Ortega E, Orozco-Solís DR, Uribe-López DI, Herrera MT, Gutiérrez-González LH, et al. Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infects Human Visceral White Adipocytes and Expresses Dormancy Genes and Inflammatory Cytokines: The Role of Visceral Adipocytes in Latent Tuberculosis Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311595

Chicago/Turabian StyleGarduño-Torres, Ana E., Manuel G. Salgado-Cantú, Silvia Guzmán-Beltrán, Jesús Montoya-Ramírez, Juan Antonio Suárez-Cuenca, Enrique Ortega, David Ricardo Orozco-Solís, Daniela I. Uribe-López, María Teresa Herrera, Luis Horacio Gutiérrez-González, and et al. 2025. "Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infects Human Visceral White Adipocytes and Expresses Dormancy Genes and Inflammatory Cytokines: The Role of Visceral Adipocytes in Latent Tuberculosis Infection" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311595

APA StyleGarduño-Torres, A. E., Salgado-Cantú, M. G., Guzmán-Beltrán, S., Montoya-Ramírez, J., Suárez-Cuenca, J. A., Ortega, E., Orozco-Solís, D. R., Uribe-López, D. I., Herrera, M. T., Gutiérrez-González, L. H., & González, Y. (2025). Mycobacterium tuberculosis Infects Human Visceral White Adipocytes and Expresses Dormancy Genes and Inflammatory Cytokines: The Role of Visceral Adipocytes in Latent Tuberculosis Infection. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11595. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311595