Exploring Fourier-Transform Infrared Microscopy for Scabies Mite Detection in Human Tissue Sections: A Preliminary Technical Feasibility Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. FTIR Spectral Comparison of Skin Layers and Scabies Mite Structures

2.2. Multivariate Image Analysis (Mia) of the 1000–1200 cm−1 Fingerprint Region

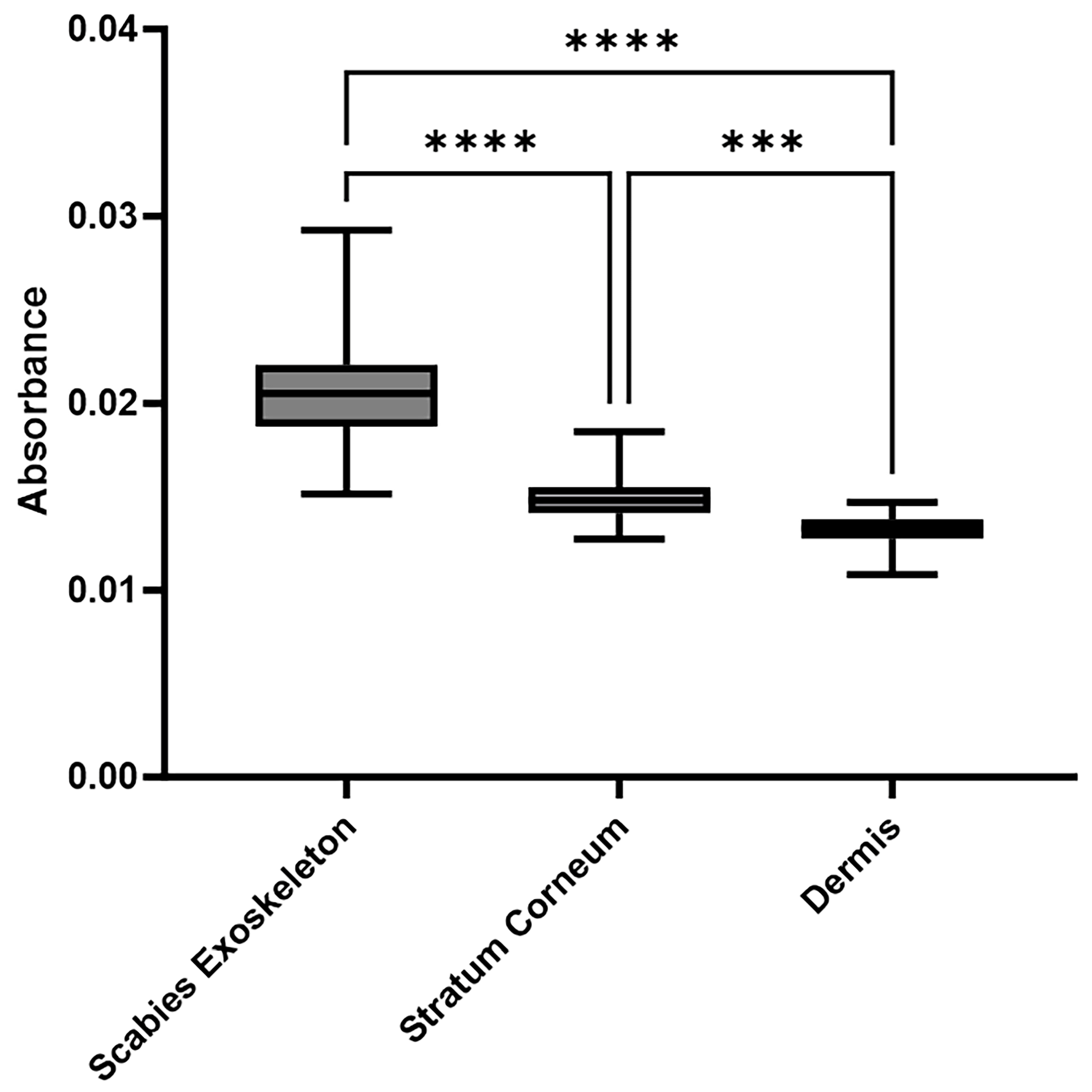

2.3. Consistent and Quantitatively Validated Scabies-Associated Absorbance at 1072 cm−1 Across Patients

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Reagents and Materials

4.2. Acquisition and Preparation of Skin Tissue Specimens

4.3. FTIR Microscopy for Tissue Characterisation

4.4. Spectral Data Processing and Image Assembly

4.5. FTIR Imaging Analysis

4.6. Statistical Analysis of Absorbance Values

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FTIR | Fourier-transform infrared |

| IR | infrared |

| FFPE | formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded |

| H&E | hematoxylin and eosin |

| FPA | focal plane array |

| MIA | multivariate image analysis |

| FCM | fuzzy c-means |

| KMC | k-means clustering |

| HCA | hierarchical cluster analysis |

| ANOVA | analysis of variance |

| SD | standard deviation |

References

- Micali, G.; Lacarrubba, F.; Verzì, A.E.; Chosidow, O.; Schwartz, R.A. Scabies: Advances in Non-invasive Diagnosis. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2016, 10, e0004691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoukat, Q.; Rizvi, A.; Wahood, W.; Coetzee, S.; Wrench, A. Sight the Mite: A Meta-Analysis on the Diagnosis of Scabies. Cureus 2023, 15, e34390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, V.; Miller, M. Detection of scabies: A systematic review of diagnostic methods. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol. 2011, 22, 143–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lacarrubba, F.; Musumeci, M.L.; Caltabiano, R.; Impallomeni, R.; West, D.P.; Micali, G. High-magnification videodermatoscopy: A new non-invasive diagnostic tool for scabies in children. Pediatr. Dermatol. 2001, 18, 439–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Neynaber, S.; Wolff, H. Diagnosis of scabies with dermoscopy. Can. Med. Assoc. J. 2008, 178, 1540–1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walton, S.F.; Currie, B.J. Problems in diagnosing scabies, a global disease in human and animal populations. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 268–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woodley, D.; Saurat, J.H. The Burrow Ink Test and the scabies mite. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1981, 4, 715–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuy, A.; Dehen, L.; Bourrat, E.; Lacroix, C.; Benderdouche, M.; Dubertret, L.; Morel, P.; Feuilhade de Chauvin, M.; Petit, A. Accuracy of standard dermoscopy for diagnosing scabies. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2007, 56, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petter, C.H.; Heigl, N.; Rainer, M.; Bakry, R.; Pallua, J.; Bonn, G.K.; Huck, C.W. Development and application of Fourier-transform infrared chemical imaging of tumour in human tissue. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 318–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhargava, R. Towards a practical Fourier transform infrared chemical imaging protocol for cancer histopathology. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 389, 1155–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, G.; Hussein, N.; Owen, R.J.; Toso, C.; Patel, V.H.; Bhargava, R.; Shapiro, A.M. Role of imaging in clinical islet transplantation. Radiographics 2010, 30, 353–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bird, B.; Miljkovic, M.; Romeo, M.J.; Smith, J.; Stone, N.; George, M.W.; Diem, M. Infrared micro-spectral imaging: Distinction of tissue types in axillary lymph node histology. BMC Clin. Pathol. 2008, 8, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, D.C.; Bhargava, R.; Hewitt, S.M.; Levin, I.W. Infrared spectroscopic imaging for histopathologic recognition. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005, 23, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steiner, G.; Koch, E. Trends in Fourier transform infrared spectroscopic imaging. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2009, 394, 671–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannan, L.; Untereiner, V.; Proult, I.; Boulagnon-Rombi, C.; Colin-Pierre, C.; Sockalingum, G.D.; Brézillon, S. Label-Free Infrared Spectral Histology of Skin Tissue Part I: Impact of Lumican on Extracellular Matrix Integrity. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amro, A.; Hamarsheh, O. Epidemiology of scabies in the West Bank, Palestinian Territories (Occupied). Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2012, 16, e117–e120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castro, P.; Lima, C.; Zorn, T.M.T.; Zezell, D.M. FTIR spectroscopy: An optical method to study wound healing process. In Proceedings of the Latin America Optics and Photonics Conference, Lima, Peru, 12–15 November 2018; p. Th4A.42. [Google Scholar]

- Peñaranda, F.; Naranjo, V.; Lloyd, G.R.; Kastl, L.; Kemper, B.; Schnekenburger, J.; Nallala, J.; Stone, N. Discrimination of skin cancer cells using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. Comput. Biol. Med. 2018, 100, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tosi, G.; Conti, C.; Giorgini, E.; Ferraris, P.; Garavaglia, M.G.; Sabbatini, S.; Staibano, S.; Rubini, C. FTIR microspectroscopy of melanocytic skin lesions: A preliminary study. Analyst 2010, 135, 3213–3219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.; Eklouh-Molinier, C.; Sebiskveradze, D.; Feru, J.; Terryn, C.; Manfait, M.; Brassart-Pasco, S.; Piot, O. Changes of skin collagen orientation associated with chronological aging as probed by polarized-FTIR micro-imaging. Analyst 2014, 139, 2482–2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klaassen, M.; De Vries, E.G.; Masen, M.A. Interpersonal differences in the friction response of skin relate to FTIR measures for skin lipids and hydration. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2020, 189, 110883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Caspers, P.J.; Lucassen, G.W.; Carter, E.A.; Bruining, H.A.; Puppels, G.J. In vivo confocal Raman microspectroscopy of the skin: Non-invasive determination of molecular concentration profiles. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2001, 116, 434–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boncheva, M.; Damien, F.; Normand, V. Molecular organization of the lipid matrix in intact Stratum corneum using ATR-FTIR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—Biomembr. 2008, 1778, 1344–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kılcı, L.; Altun, N.; Karaoğlu, Ş.A.; Karaduman Yeşildal, T. Characterization of chitin and description of its antimicrobial properties obtained from Cydalima perspectalis adults. Polym. Bull. 2024, 81, 14217–14234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunner, A.; Unterberger, S.H.; Auer, H.; Hautz, T.; Schneeberger, S.; Stalder, R.; Badzoka, J.; Kappacher, C.; Huck, C.W.; Zelger, B.; et al. Suitability of Fourier transform infrared microscopy for the diagnosis of cystic echinococcosis in human tissue sections. J. Biophotonics 2024, 17, e202300513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallua, J.D.; Unterberger, S.H.; Pemberger, N.; Woess, C.; Ensinger, C.; Zelger, B.; Lass-Flörl, C.; Lackner, M. Retrospective case study on the suitability of mid-infrared microscopic imaging for the diagnosis of mucormycosis in human tissue sections. Anal. Methods 2017, 9, 4135–4142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kidder, L.H.; Colarusso, P.; Stewart, S.A.; Levin, I.W.; Appel, N.M.; Lester, D.S.; Pentchev, P.G.; Lewis, E.N. Infrared spectroscopic imaging of the biochemical modifications induced in the cerebellum of the Niemann–Pick type C mouse. J. Biomed. Opt. 1999, 4, 7–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pallua, J.D.; Pezzei, C.; Zelger, B.; Schaefer, G.; Bittner, L.K.; Huck-Pezzei, V.A.; Schoenbichler, S.A.; Hahn, H.; Kloss-Brandstaetter, A.; Kloss, F.; et al. Fourier transform infrared imaging analysis in discrimination studies of squamous cell carcinoma. Analyst 2012, 137, 3965–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dučić, T.; Sanchez-Mata, A.; Castillo-Sanchez, J.; Algarra, M.; Gonzalez-Munoz, E. Monitoring oocyte-based human pluripotency acquisition using synchrotron-based FTIR microspectroscopy reveals specific biomolecular trajectories. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 297, 122713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Czamara, K.; Majzner, K.; Pacia, M.Z.; Kochan, K.; Kaczor, A.; Baranska, M. Raman spectroscopy of lipids: A review. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2015, 46, 4–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantsch, H.H.; Chapman, D. Infrared Spectroscopy of Biomolecules; Wiley-Liss: New York, NY, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Gremlich, H.-U.; Yan, B. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy of Biological Materials; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2001; Volume 24. [Google Scholar]

- Salzer, R.; Siesler, H.W. Infrared and Raman Spectroscopic Imaging; Vch Pub: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Bhargava, R.; Levin, I. Spectrochemical Analysis Using Infrared Multichannel Detectors; Wiley-Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Colthup, N.B.; Daly, L.H.; Wiberley, S.E. Introduction to Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Lin-Vien, D.; Colthup, N.B.; Fateley, W.G.; Grasselli, J.G. The Handbook of Infrared and Raman Characteristic Frequencies of Organic Molecules; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Hengge, U.R.; Currie, B.J.; Jäger, G.; Lupi, O.; Schwartz, R.A. Scabies: A ubiquitous neglected skin disease. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 769–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, E.; Romani, L.; Whitfeld, M.J. Recent advances in understanding and treating scabies. Fac. Rev. 2021, 10, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernigaud, C.; Fischer, K.; Chosidow, O. The Management of Scabies in the 21st Century: Past, Advances and Potentials. Acta Derm. Venereol. 2020, 100, adv00112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hicks, M.I.; Elston, D.M. Scabies. Dermatol. Ther. 2009, 22, 279–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M.J.; Byrne, H.J.; Chalmers, J.; Gardner, P.; Goodacre, R.; Henderson, A.; Kazarian, S.G.; Martin, F.L.; Moger, J.; Stone, N.; et al. Clinical applications of infrared and Raman spectroscopy: State of play and future challenges. Analyst 2018, 143, 1735–1757, Erratum in Analyst 2018, 143, 1934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barth, A. Infrared spectroscopy of proteins. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2007, 1767, 1073–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, H.J.; Cameron, J.M.; Jenkins, C.A.; Hithell, G.; Hume, S.; Hunt, N.T.; Baker, M.J. Shining a light on clinical spectroscopy: Translation of diagnostic IR, 2D-IR and Raman spectroscopy towards the clinic. Clin. Spectrosc. 2019, 1, 100003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellisola, G.; Sorio, C. Infrared spectroscopy and microscopy in cancer research and diagnosis. Am. J. Cancer Res. 2012, 2, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zelger, B. Zehn Clues zur histopathologischen Diagnose von infektiösen Hautkrankheiten. Der Pathol. 2002, 23, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toplak, M.; Read, S.T.; Sandt, C.; Borondics, F. Quasar: Easy Machine Learning for Biospectroscopy. Cells 2021, 10, 2300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| NO | Biopsie Site | Sex | Age | Histology |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | left thigh | M | 73 | positive |

| 2 | gluteal | M | 81 | positive |

| 3 | lumbal | M | 36 | positive |

| 4 | not specified | F | 68 | positive |

| 5 | not specified | F | 88 | positive |

| 6 | abdomen | F | 21 | positive |

| Wavenumber (cm−1) | Vibrational Mode | Dermis | Stratum Corneum | Scabies Exoskeleton | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ~3300 | OH/NH stretch | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | ✓✓✓ | protein amide A vibration [27,28] |

| ~2920 | CH2 asym. stretch | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | Lipid chains (membranes, cuticle) [29] |

| ~2850 | CH2 sym. stretch | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | ✓✓ | Lipid methylene groups [29] |

| ~1730 | C=O stretch (ester) | — | ✓✓ | ✓ | Triacylglycerol:Tripetroselinin (TPE) [30] |

| ~1650 | Amide I (C=O) | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | Protein secondary structure [31,32] |

| ~1550 | Amide II (N-H/C-N) | ✓✓✓ | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | Proteins with α-helix and random coil conformations [33,34] |

| ~1200–1000 | C–O/C–C stretch | — | ✓ | ✓✓✓ | Chitin-rich carbohydrate (arthropod exoskeleton component) [35,36] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lammer, M.; Schmuth, M.; Bellmann, P.; Moosbrugger-Martinz, V.; Zelger, B.; Moser, B.; Stalder, R.; Huck, C.W.; Klosterhuber, M.; Pallua, J.D. Exploring Fourier-Transform Infrared Microscopy for Scabies Mite Detection in Human Tissue Sections: A Preliminary Technical Feasibility Study. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311597

Lammer M, Schmuth M, Bellmann P, Moosbrugger-Martinz V, Zelger B, Moser B, Stalder R, Huck CW, Klosterhuber M, Pallua JD. Exploring Fourier-Transform Infrared Microscopy for Scabies Mite Detection in Human Tissue Sections: A Preliminary Technical Feasibility Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311597

Chicago/Turabian StyleLammer, Maximilian, Matthias Schmuth, Paul Bellmann, Verena Moosbrugger-Martinz, Bernhard Zelger, Birgit Moser, Roland Stalder, Christian Wolfgang Huck, Miranda Klosterhuber, and Johannes Dominikus Pallua. 2025. "Exploring Fourier-Transform Infrared Microscopy for Scabies Mite Detection in Human Tissue Sections: A Preliminary Technical Feasibility Study" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311597

APA StyleLammer, M., Schmuth, M., Bellmann, P., Moosbrugger-Martinz, V., Zelger, B., Moser, B., Stalder, R., Huck, C. W., Klosterhuber, M., & Pallua, J. D. (2025). Exploring Fourier-Transform Infrared Microscopy for Scabies Mite Detection in Human Tissue Sections: A Preliminary Technical Feasibility Study. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11597. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311597