SLC35A2-Related Brain Disorders: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Insights

Abstract

1. Introduction: Protein Glycosylation in the Brain

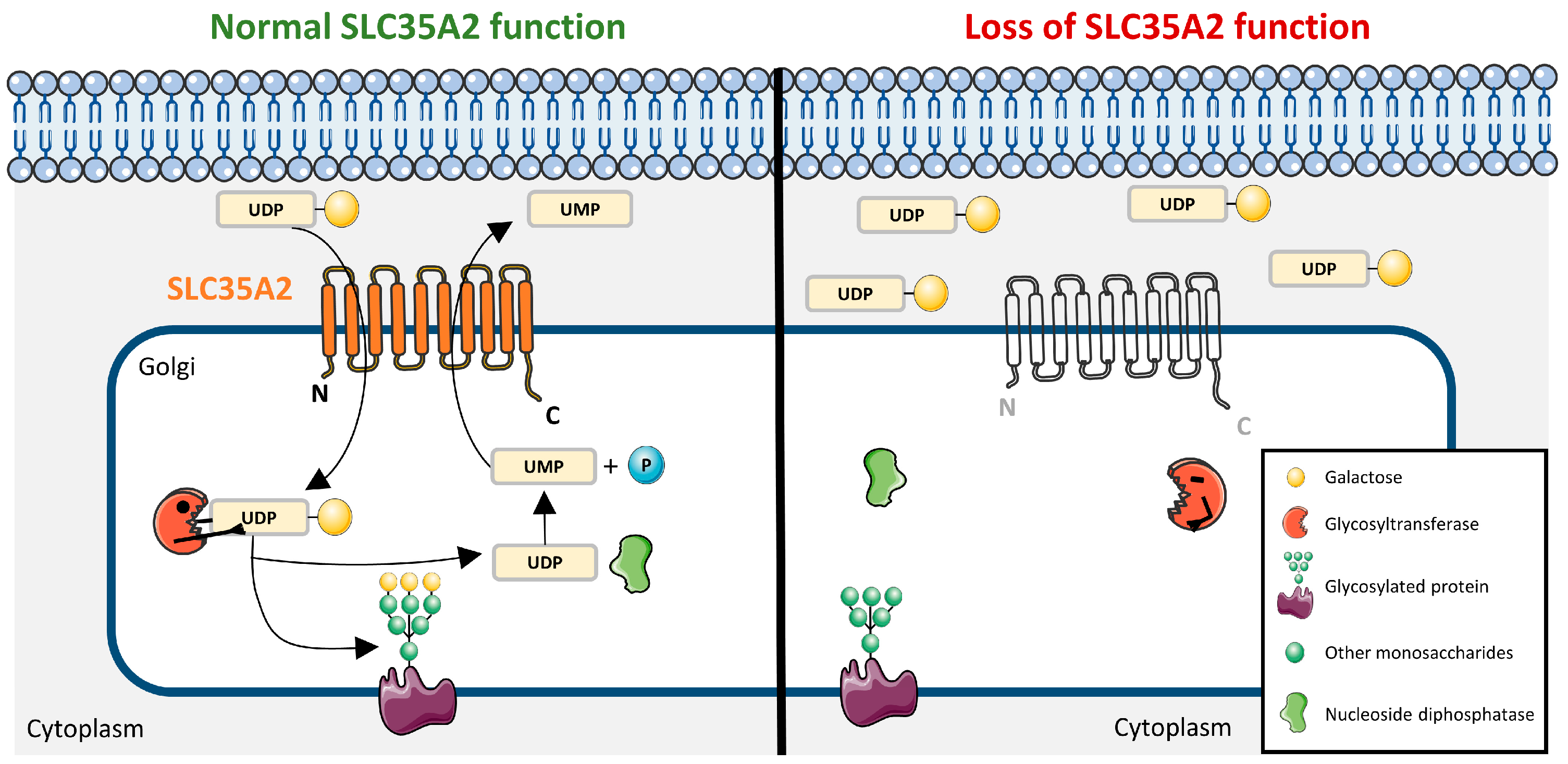

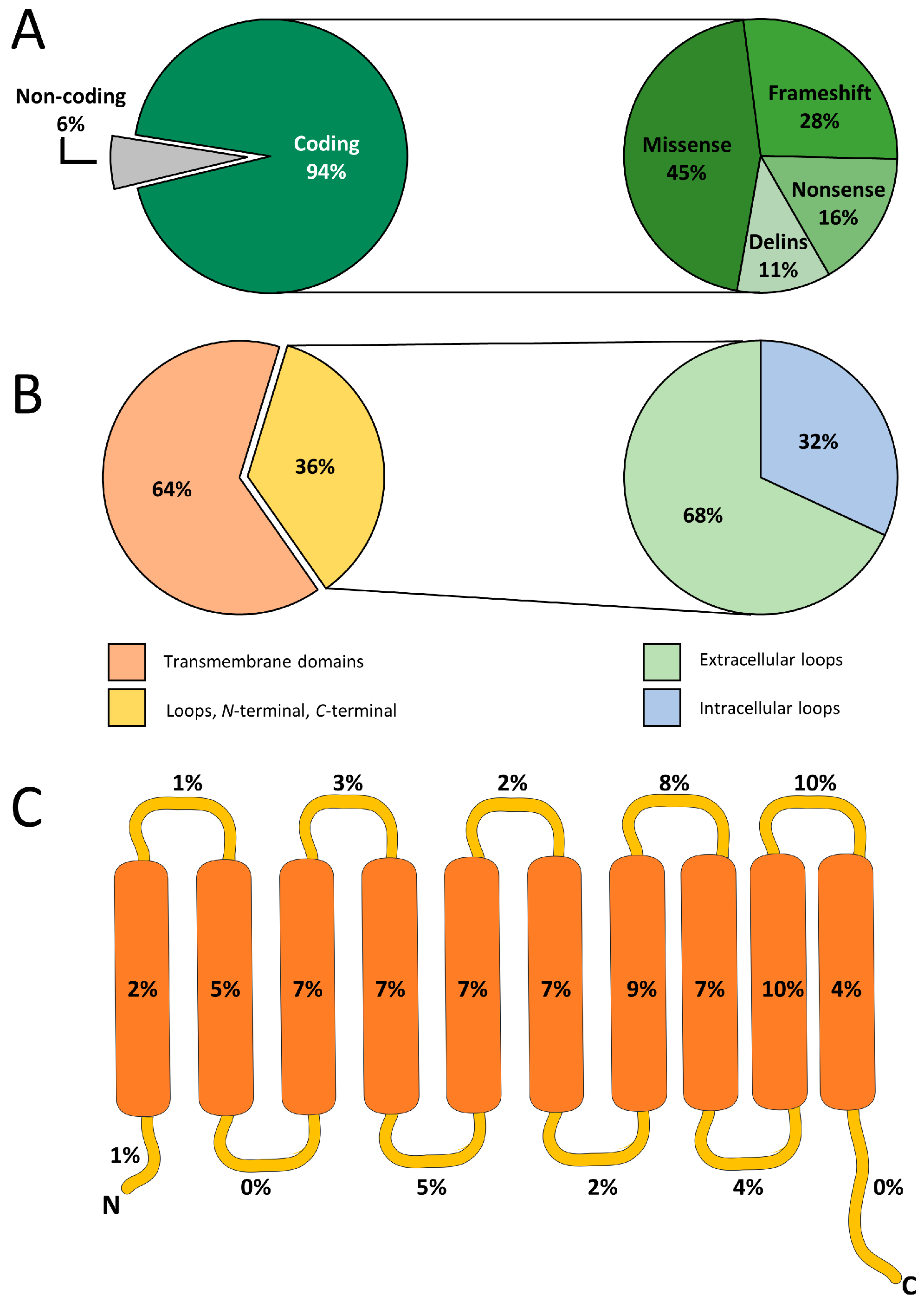

2. The SLC35 Protein Family and SLC35A2

3. From CDG to MOGHE: The Spectrum of SLC35A2-Related Disorders

3.1. SLC35A2 Germline and Systemic Mosaic Variants

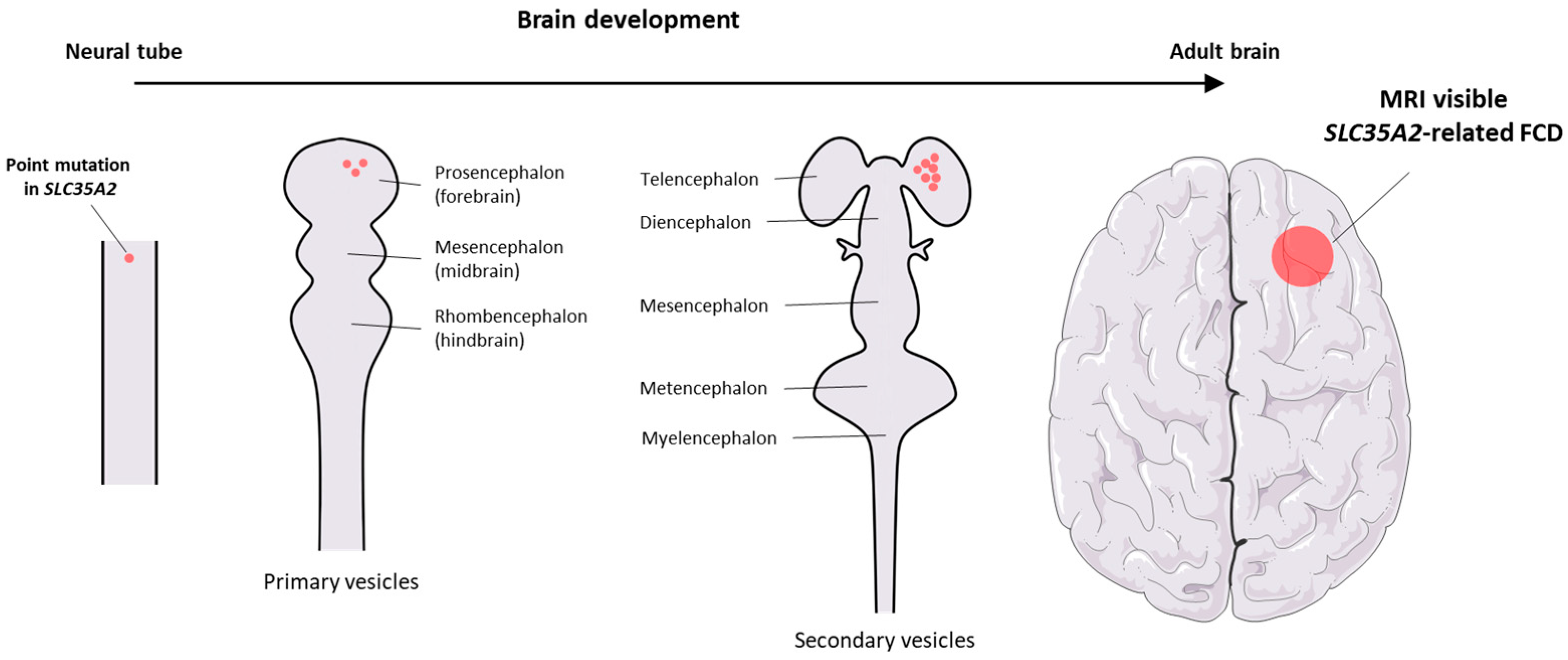

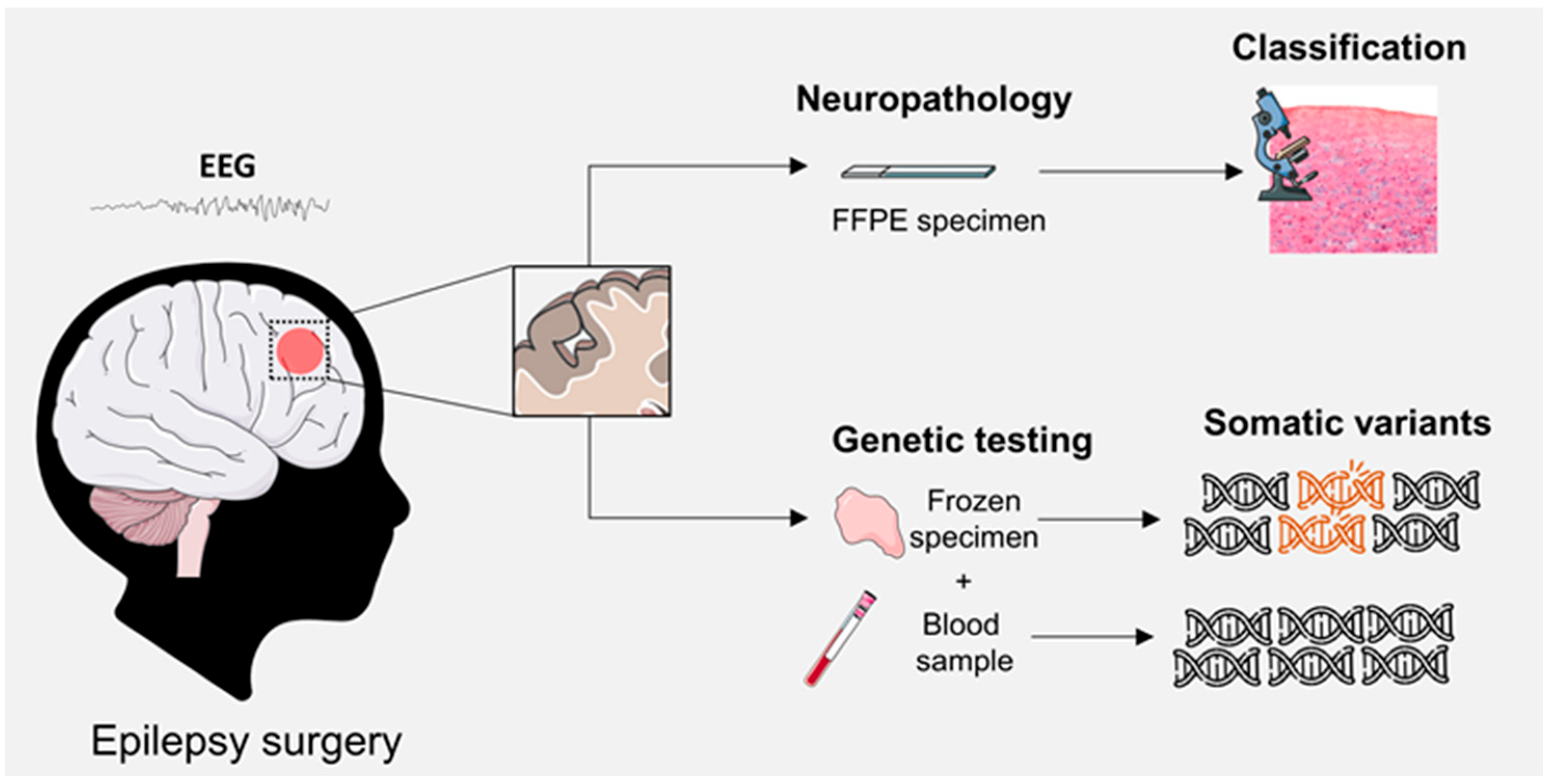

3.2. Somatic SLC35A2 Mosaicism in the Brain

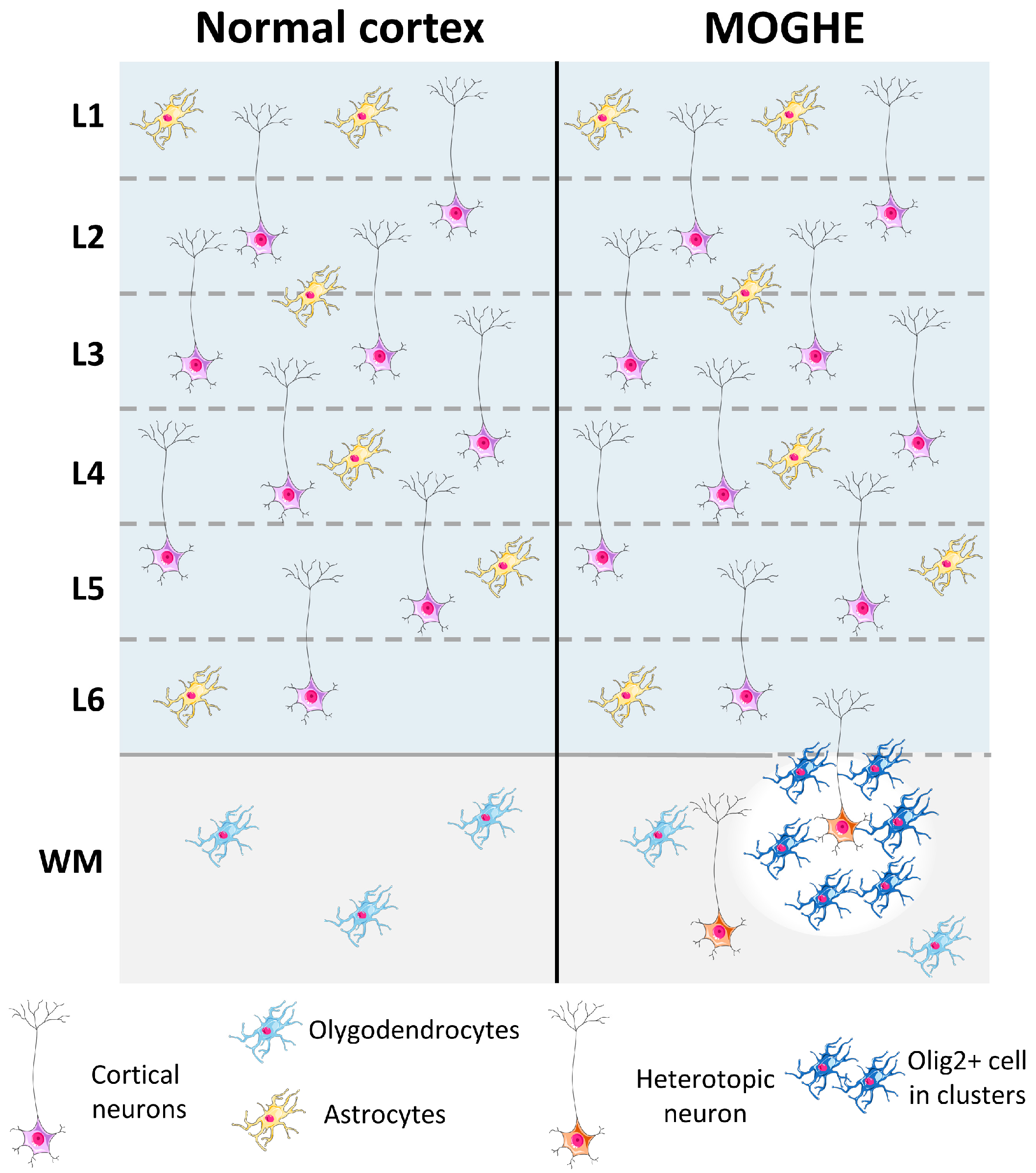

3.3. SLC35A2-Associated MOGHE

4. Molecular and Cellular Pathogenesis of SLC35A2-Related Disorders

4.1. Insights from Human and Induced Pluripotent Stem Cell (iPSC) Models of MOGHE

4.2. In Vivo Mechanistic Studies of SLC35A2 Pathology

5. D-Galactose Supplementation as a Targeted Treatment

6. Limitations and Additional Considerations

7. Conclusions and Perspectives

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

References

- Freeze, H.H.; Chong, J.X.; Bamshad, M.J.; Ng, B.G. Solving glycosylation disorders: Fundamental approaches reveal complicated pathways. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2015, 96, 161–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, M.; Zhou, X.; Wang, X. Glycosylation: Mechanisms, biological functions and clinical implications. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2024, 9, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanley, P.; Taniguchi, N.; Aebi, M. N-Glycans. In Essentials of Glycobiology; Varki, A., Cummings, R.D., Esko, J.D., Stanley, P., Hart, G.W., Aebi, M., Mohnen, D., Kinoshita, T., Packer, N.H., Prestegard, J.H., et al., Eds.; Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press: Cold Spring Harbor, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Moremen, K.W.; Tiemeyer, M.; Nairn, A.V. Vertebrate protein glycosylation: Diversity, synthesis and function. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012, 13, 448–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.; Panin, V.M. The role of protein N-glycosylation in neural transmission. Glycobiology 2014, 24, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reily, C.; Stewart, T.J.; Renfrow, M.B.; Novak, J. Glycosylation in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 2019, 15, 346–366, Erratum in Nat. Rev. Nepheol. 2025, 21, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Endo, T. Glycobiology of α-dystroglycan and muscular dystrophy. J. Biochem. 2015, 157, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, S.E.; Noel, M.; Lehoux, S.; Cetinbas, M.; Xavier, R.J.; Sadreyev, R.I.; Scolnick, E.M.; Smoller, J.W.; Cummings, R.D.; Mealer, R.G. Mammalian brain glycoproteins exhibit diminished glycan complexity compared to other tissues. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeze, H.H.; Eklund, E.A.; Ng, B.G.; Patterson, M.C. Neurology of inherited glycosylation disorders. Lancet Neurol. 2012, 11, 453–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paprocka, J.; Jezela-Stanek, A.; Tylki-Szymańska, A.; Grunewald, S. Congenital Disorders of Glycosylation from a Neurological Perspective. Brain Sci. 2021, 11, 88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pradeep, P.; Kang, H.; Lee, B. Glycosylation and behavioral symptoms in neurological disorders. Transl. Psychiatry. 2023, 13, 154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaller, L.; Lauschke, V.M. The genetic landscape of the human solute carrier (SLC) transporter superfamily. Hum. Genet. 2019, 138, 1359–1377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadley, B.; Litfin, T.; Day, C.J.; Haselhorst, T.; Zhou, Y.; Tiralongo, J. Nucleotide Sugar Transporter SLC35 Family Structure and Function. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 2019, 17, 1123–1134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeshima-Futagami, T.; Sakaguchi, M.; Uehara, E.; Aoki, K.; Ishida, N.; Sanai, Y.; Sugahara, Y.; Kawakita, M. Amino acid residues important for CMP-sialic acid recognition by the CMP-sialic acid transporter: Analysis of the substrate specificity of UDP-galactose/CMP-sialic acid transporter chimeras. Glycobiology 2012, 22, 1731–1740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maszczak-Seneczko, D.; Wiktor, M.; Skurska, E.; Wiertelak, W.; Olczak, M. Delivery of Nucleotide Sugars to the Mammalian Golgi: A Very Well (un)Explained Story. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 8648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maszczak-Seneczko, D.; Sosicka, P.; Majkowski, M.; Olczak, T.; Olczak, M. UDP-N-acetylglucosamine transporter and UDP-galactose transporter form heterologous complexes in the Golgi membrane. FEBS Lett. 2012, 586, 4082–4087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiktor, M.; Wiertelak, W.; Maszczak-Seneczko, D.; Balwierz, P.J.; Szulc, B.; Olczak, M. Identification of novel potential interaction partners of UDP-galactose (SLC35A2), UDP-N-acetylglucosamine (SLC35A3) and an orphan (SLC35A4) nucleotide sugar transporters. J. Proteom. 2021, 249, 104321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.L.; Newstead, S. Gateway to the Golgi: Molecular mechanisms of nucleotide sugar transporters. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 2019, 57, 127–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamiyama, S.; Sone, H. Solute Carrier Family 35 (SLC35)—An Overview and Recent Progress. Biologics 2024, 4, 242–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabuss, R.; Ashikov, A.; Oelmann, S.; Gerardy-Schahn, R.; Bakker, H. Endoplasmic reticulum retention of the large splice variant of the UDP-galactose transporter is caused by a dilysine motif. Glycobiology 2005, 15, 905–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Xu, Y.X.; Hirschberg, C.B. The role of nucleotide sugar transporters in development of eukaryotes. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 2010, 21, 600–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puglielli, L.; Hirschberg, C.B. Reconstitution, purification, and characterization of the rat liver Golgi UDP-galactose transporter. J. Biol. Chem. 1999, 274, 4474–4479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, J.L.; Corey, R.A.; Stansfeld, P.J.; Newstead, S. Structural basis for substrate specificity and regulation of nucleotide sugar transporters in the lipid bilayer. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiertelak, W.; Pavlovskyi, A.; Olczak, M.; Maszczak-Seneczko, D. Cytosolic UDP-Gal biosynthetic machinery is required for dimerization of SLC35A2 in the Golgi membrane and its interaction with B4GalT1. Front Mol. Biosci. 2025, 12, 1563384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kodera, H.; Nakamura, K.; Osaka, H.; Maegaki, Y.; Haginoya, K.; Mizumoto, S.; Kato, M.; Okamoto, N.; Iai, M.; Kondo, Y.; et al. De novo mutations in SLC35A2 encoding a UDP-galactose transporter cause early-onset epileptic encephalopathy. Hum. Mutat. 2013, 34, 1708–1714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.G.; Buckingham, K.J.; Raymond, K.; Kircher, M.; Turner, E.H.; He, M.; Smith, J.D.; Eroshkin, A.; Szybowska, M.; Losfeld, M.E.; et al. Mosaicism of the UDP-galactose transporter SLC35A2 causes a congenital disorder of glycosylation. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 92, 632–636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vals, M.A.; Ashikov, A.; Ilves, P.; Loorits, D.; Zeng, Q.; Barone, R.; Huijben, K.; Sykut-Cegielska, J.; Diogo, L.; Elias, A.F.; et al. Clinical, neuroradiological, and biochemical features of SLC35A2-CDG patients. J. Inherit. Metab. Dis. 2019, 42, 553–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ng, B.G.; Sosicka, P.; Agadi, S.; Almannai, M.; Bacino, C.A.; Barone, R.; Botto, L.D.; Burton, J.E.; Carlston, C.; Chung, B.H.; et al. SLC35A2-CDG: Functional characterization, expanded molecular, clinical, and biochemical phenotypes of 30 unreported Individuals. Hum. Mutat. 2019, 40, 908–925. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kimizu, T.; Takahashi, Y.; Oboshi, T.; Horino, A.; Koike, T.; Yoshitomi, S.; Mori, T.; Yamaguchi, T.; Ikeda, H.; Okamoto, N.; et al. A case of early onset epileptic encephalopathy with de novo mutation in SLC35A2: Clinical features and treatment for epilepsy. Brain Dev. 2017, 39, 256–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yates, T.M.; Suri, M.; Desurkar, A.; Lesca, G.; Wallgren-Pettersson, C.; Hammer, T.B.; Raghavan, A.; Poulat, A.L.; Møller, R.S.; Thuresson, M.; et al. SLC35A2-related congenital disorder of glycosylation: Defining the phenotype. Eur. J. Paediatr. Neurol. 2018, 22, 1095–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quelhas, D.; Correia, J.; Jaeken, J.; Azevedo, L.; Lopes-Marques, M.; Bandeira, A.; Keldermans, L.; Matthijs, G.; Sturiale, L.; Martins, E. SLC35A2-CDG: Novel variant and review. Mol. Genet. Metab. Rep. 2021, 26, 100717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Witters, P.; Tahata, S.; Barone, R.; Õunap, K.; Salvarinova, R.; Grønborg, S.; Hoganson, G.; Scaglia, F.; Lewis, A.M.; Mori, M.; et al. Clinical and biochemical improvement with galactose supplementation in SLC35A2-CDG. Genet. Med. 2020, 22, 1102–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winawer, M.R.; Griffin, N.G.; Samanamud, J.; Baugh, E.H.; Rathakrishnan, D.; Ramalingam, S.; Zagzag, D.; Schevon, C.A.; Dugan, P.; Hegde, M.; et al. Somatic SLC35A2 variants in the brain are associated with intractable neocortical epilepsy. Ann. Neurol. 2018, 83, 1133–1146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, N.S.; Seo, Y.; Lim, J.S.; Kim, W.K.; Son, H.; Kim, H.D.; Kim, S.; An, H.J.; Kang, H.C.; Kim, S.H.; et al. Brain somatic mutations in SLC35A2 cause intractable epilepsy with aberrant N-glycosylation. Neurol. Genet. 2018, 4, e294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassari, S.; Ribierre, T.; Marsan, E.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Ferrand-Sorbets, S.; Bulteau, C.; Dorison, N.; Fohlen, M.; Polivka, M.; Weckhuysen, S.; et al. Dissecting the genetic basis of focal cortical dysplasia: A large cohort study. Acta Neuropathol. 2019, 138, 885–900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.E.; Koboldt, D.C.; Schieffer, K.M.; Bedrosian, T.A.; Crist, E.; Sheline, A.; Leraas, K.; Magrini, V.; Zhong, H.; Brennan, P.; et al. Somatic SLC35A2 mosaicism correlates with clinical findings in epilepsy brain tissue. Neurol. Genet. 2020, 6, e460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaballa, A.; Woermann, F.G.; Cloppenborg, T.; Kalbhenn, T.; Blümcke, I.; Bien, C.G.; Fauser, S. Clinical characteristics and postoperative seizure outcome in patients with mild malformation of cortical development and oligodendroglial hyperplasia. Epilepsia 2021, 62, 2920–2931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barba, C.; Blumcke, I.; Winawer, M.R.; Hartlieb, T.; Kang, H.C.; Grisotto, L.; Chipaux, M.; Bien, C.G.; Heřmanovská, B.; Porter, B.E.; et al. Clinical Features, Neuropathology, and Surgical Outcome in Patients with Refractory Epilepsy and Brain Somatic Variants in the SLC35A2 Gene. Neurology 2023, 100, e528–e542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanders, M.W.C.B.; Koeleman, B.P.C.; Brilstra, E.H.; Jansen, F.E.; Baldassari, S.; Chipaux, M.; Sim, N.S.; Ko, A.; Kang, H.C.; Blümcke, I.; et al. Somatic variant analysis of resected brain tissue in epilepsy surgery patients. Epilepsia 2024, 65, e209–e215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schurr, J.; Coras, R.; Rössler, K.; Pieper, T.; Kudernatsch, M.; Holthausen, H.; Winkler, P.; Woermann, F.; Bien, C.G.; Polster, T.; et al. Mild Malformation of Cortical Development with Oligodendroglial Hyperplasia in Frontal Lobe Epilepsy: A New Clinico-Pathological Entity. Brain Pathol. 2017, 27, 26–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najm, I.; Lal, D.; Alonso Vanegas, M.; Cendes, F.; Lopes-Cendes, I.; Palmini, A.; Paglioli, E.; Sarnat, H.B.; Walsh, C.A.; Wiebe, S.; et al. The ILAE consensus classification of focal cortical dysplasia: An update proposed by an ad hoc task force of the ILAE diagnostic methods commission. Epilepsia 2022, 63, 1899–1919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hartlieb, T.; Winkler, P.; Coras, R.; Pieper, T.; Holthausen, H.; Blümcke, I.; Staudt, M.; Kudernatsch, M. Age-related MR characteristics in mild malformation of cortical development with oligodendroglial hyperplasia and epilepsy (MOGHE). Epilepsy Behav. 2019, 91, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonduelle, T.; Hartlieb, T.; Baldassari, S.; Sim, N.S.; Kim, S.H.; Kang, H.C.; Kobow, K.; Coras, R.; Chipaux, M.; Dorfmüller, G.; et al. Frequent SLC35A2 brain mosaicism in mild malformation of cortical development with oligodendroglial hyperplasia in epilepsy (MOGHE). Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2021, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhan, Y.; Chen, S.; Jin, Z.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.X.; Hou, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zheng, G.; Zheng, Y. Mild Malformation of Cortical Development with Oligodendroglial Hyperplasia and Epilepsy: A Systematic Review. Neurol. Genet. 2025, 11, e200240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, E.; Hartlieb, T.; Gaballa, A.; Kobow, K.; Katoch, M.; Vasileiou, M.; Hofer, W.; Reisch, M.; Kudernatsch, M.; Bien, C.G.; et al. High incidence of Y-chromosome mosaicism in male and female individuals with MOGHE. MedXriv 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cecchini, E.; Geffers, S.; Coras, R.; Schultheis, D.; Holtzhausen, C.; Karandasheva, K.; Herrmann, H.; Paulsen, F.; Stadelmann, C.; Kobow, K.; et al. Human brain tissue with MOGHE carrying somatic SLC35A2 variants reveal aberrant protein expression and protein loss in the white matter. Acta Neuropathol. 2025, 149, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Tang, Q.; Xia, X.; Liu, Q.; Liu, J.; Jin, Y.; Wu, P.; Luo, H.; Gao, K.; Ruan, X.; et al. Somatic variants in SLC35A2 leading to defects in N-glycosylation in mild malformation of cortical development with oligodendroglial hyperplasia in epilepsy (MOGHE). Acta Neuropathol. 2025, 149, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lai, D.; Sosicka, P.; Williams, D.J.; Bowyer, M.E.; Ressler, A.K.; Kohrt, S.E.; Muron, S.J.; Crino, P.B.; Freeze, H.H.; Boland, M.J.; et al. SLC35A2 loss-of-function variants affect glycomic signatures, neuronal fate and network dynamics. Brain 2025, 26, awaf198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvão, I.C.; Lemoine, M.; Kandratavicius, L.; Yasuda, C.L.; Alvim, M.K.M.; Ghizoni, E.; Blümcke, I.; Cendes, F.; Rogerio, F.; Lopes-Cendes, I.; et al. Cell type mapping of mild malformations of cortical development with oligodendroglial hyperplasia in epilepsy using single-nucleus multiomics. Epilepsia 2025, 66, 3064–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elziny, S.; Sran, S.; Yoon, H.; Corrigan, R.R.; Page, J.; Ringland, A.; Lanier, A.; Lapidus, S.; Foreman, J.; Heinzen, E.L.; et al. Loss of Slc35a2 alters development of the mouse cerebral cortex. Neurosci. Lett. 2024, 836, 137881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spyrou, J.; Aung, K.P.; Vanyai, H.; Leventer, R.J.; Maljevic, S.; Lockhart, P.J.; Howell, K.B.; Reid, C.A. Slc35a2 mosaic knockout impacts cortical development, dendritic arborisation, and neuronal firing. Neurobiol. Dis. 2024, 201, 106657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, H.; Ringland, A.; Anderson, J.J.; Sran, S.; Elziny, S.; Huynh, C.; Shinagawa, N.; Badertscher, S.; Corrigan, R.R.; Mashburn-Warren, L.; et al. Mouse models of Slc35a2 brain mosaicism reveal mechanisms of mild malformations of cortical development with oligodendroglial hyperplasia in epilepsy. Epilepsia 2024, 65, 3717–3731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartel, T.M.; Ghosh, C.; Bisaha, K.; Khoury, J.; Nemes-Baran, A.; Blumcke, I.; Najm, I. Olig2-specific loss-of-function Slc35a2 results in hypomyelination and spontaneous seizures. Epilepsia 2025, 00, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falace, A.; Corbières, L.; Silvagnoli, L.; Pelorosso, C.; Tuccari di San Carlo, C.; Buhler, E.; Hoteit, Z.; Bauer, S.; Risso, B.; Cesar, Q.; et al. Mosaic expression of SLC35A2 pathogenetic variants impairs neuronal migration and dendritogenesis in the developing cortex. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2025, ddaf156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holden, H.M.; Rayment, I.; Thoden, J.B. Structure and function of enzymes of the Leloir pathway for galactose metabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2003, 278, 43885–44388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aledo-Serrano, Á.; Valls-Carbó, A.; Fenger, C.D.; Groeppel, G.; Hartlieb, T.; Pascual, I.; Herraez, E.; Cabal, B.; García-Morales, I.; Toledano, R.; et al. D-galactose Supplementation for the Treatment of Mild Malformation of Cortical Development with Oligodendroglial Hyperplasia in Epilepsy (MOGHE): A Pilot Trial of Precision Medicine After Epilepsy Surgery. Neurotherapeutics 2023, 20, 1294–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jáñez Pedrayes, A.; De Craemer, S.; Idkowiak, J.; Verdegem, D.; Thiel, C.; Barone, R.; Serrano, M.; Honzík, T.; Morava, E.; Vermeersch, P.; et al. Glycosphingolipid synthesis is impaired in SLC35A2-CDG and improves with galactose supplementation. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2025, 82, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| AREA | KEY OPEN QUESTIONS/RESEARCH PRIORITIES |

|---|---|

| MOLECULAR MECHANISMS | How does impaired UDP–galactose transport alter neuronal membrane composition, receptor trafficking, and network excitability? Integration of glycoproteomics and electrophysiology is needed to link hypogalactosylation to epileptogenesis. |

| GENETIC HETEROGENEITY | Which additional genes or regulatory mechanisms cause MOGHE in SLC35A2-negative cases? Deep sequencing and methylomic profiling should be applied to unresolved patients. |

| SEX CHROMOSOME BIOLOGY | What is the role of Y-chromosome mosaicism in MOGHE pathogenesis, and how does it interact with glycosylation and oligodendroglial proliferation? |

| CELLULAR AND TRANSLATIONAL MODELS | Develop neuronal–glial co-culture systems and brain organoids to replicate somatic mosaicism and dissect cell-type–specific dysfunction. |

| THERAPEUTIC STRATEGIES | Conduct controlled trials of D-galactose and explore complementary approaches (metabolic boosters, mRNA or viral rescue) to restore glycosylation. |

| CLINICAL INTEGRATION | Standardize diagnostic workflows combining MRI, EEG, and deep brain sequencing to improve identification and management of mosaic SLC35A2-related epilepsies. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Risso, B.; Riva, A.; Volpedo, G.; Conti, V.; di San Carlo, C.T.; Zara, F.; Striano, P.; Falace, A. SLC35A2-Related Brain Disorders: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Insights. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311560

Risso B, Riva A, Volpedo G, Conti V, di San Carlo CT, Zara F, Striano P, Falace A. SLC35A2-Related Brain Disorders: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311560

Chicago/Turabian StyleRisso, Beatrice, Antonella Riva, Greta Volpedo, Valerio Conti, Clara Tuccari di San Carlo, Federico Zara, Pasquale Striano, and Antonio Falace. 2025. "SLC35A2-Related Brain Disorders: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Insights" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311560

APA StyleRisso, B., Riva, A., Volpedo, G., Conti, V., di San Carlo, C. T., Zara, F., Striano, P., & Falace, A. (2025). SLC35A2-Related Brain Disorders: Genetics, Pathophysiology, and Therapeutic Insights. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11560. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311560