Synthesis of 1,3-Thiazine and 1,4-Thiazepine Derivatives via Cycloadditions and Ring Expansion

Abstract

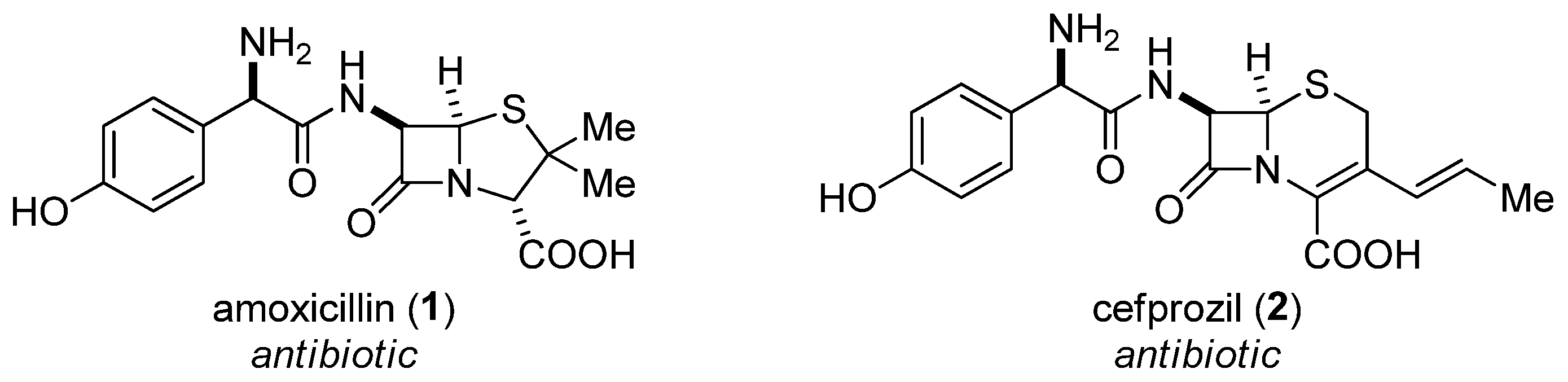

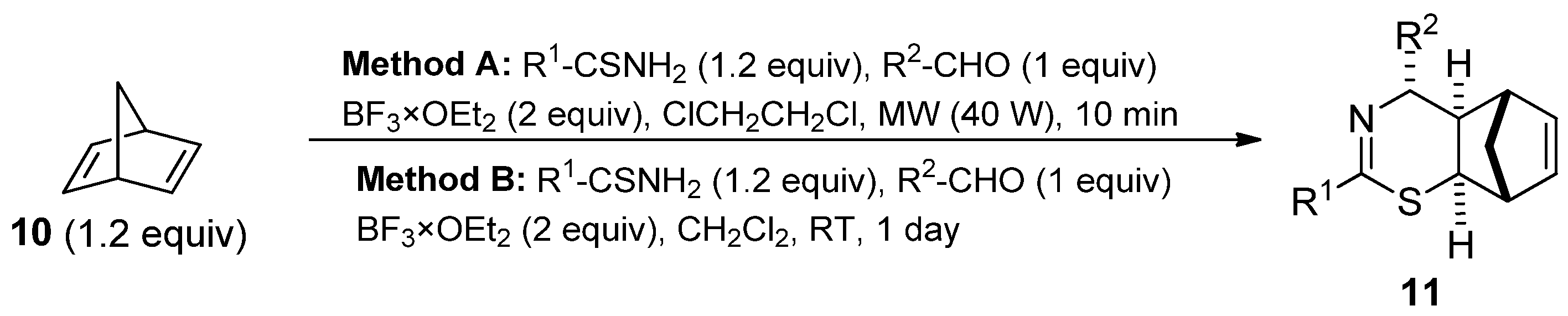

1. Introduction

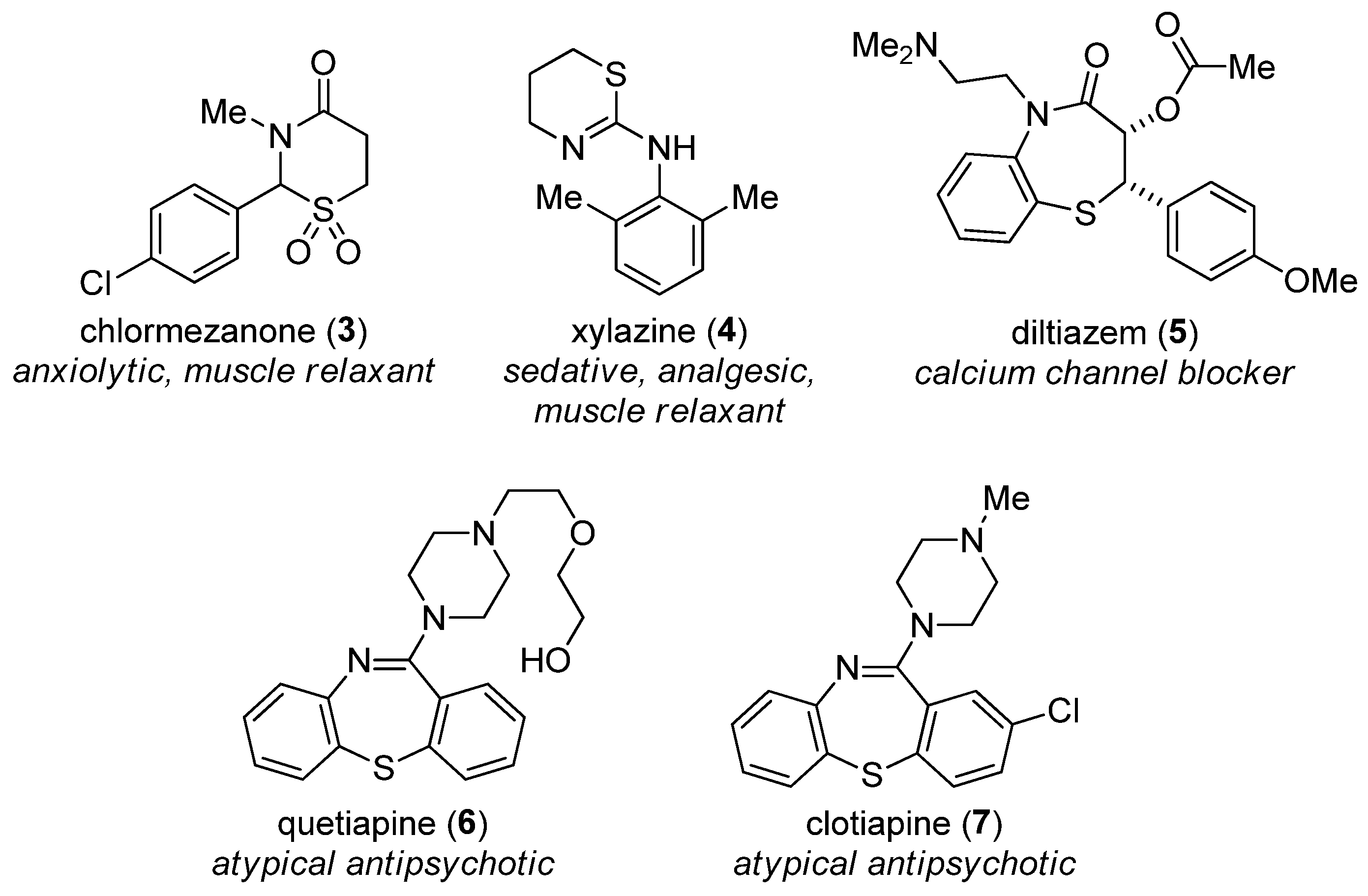

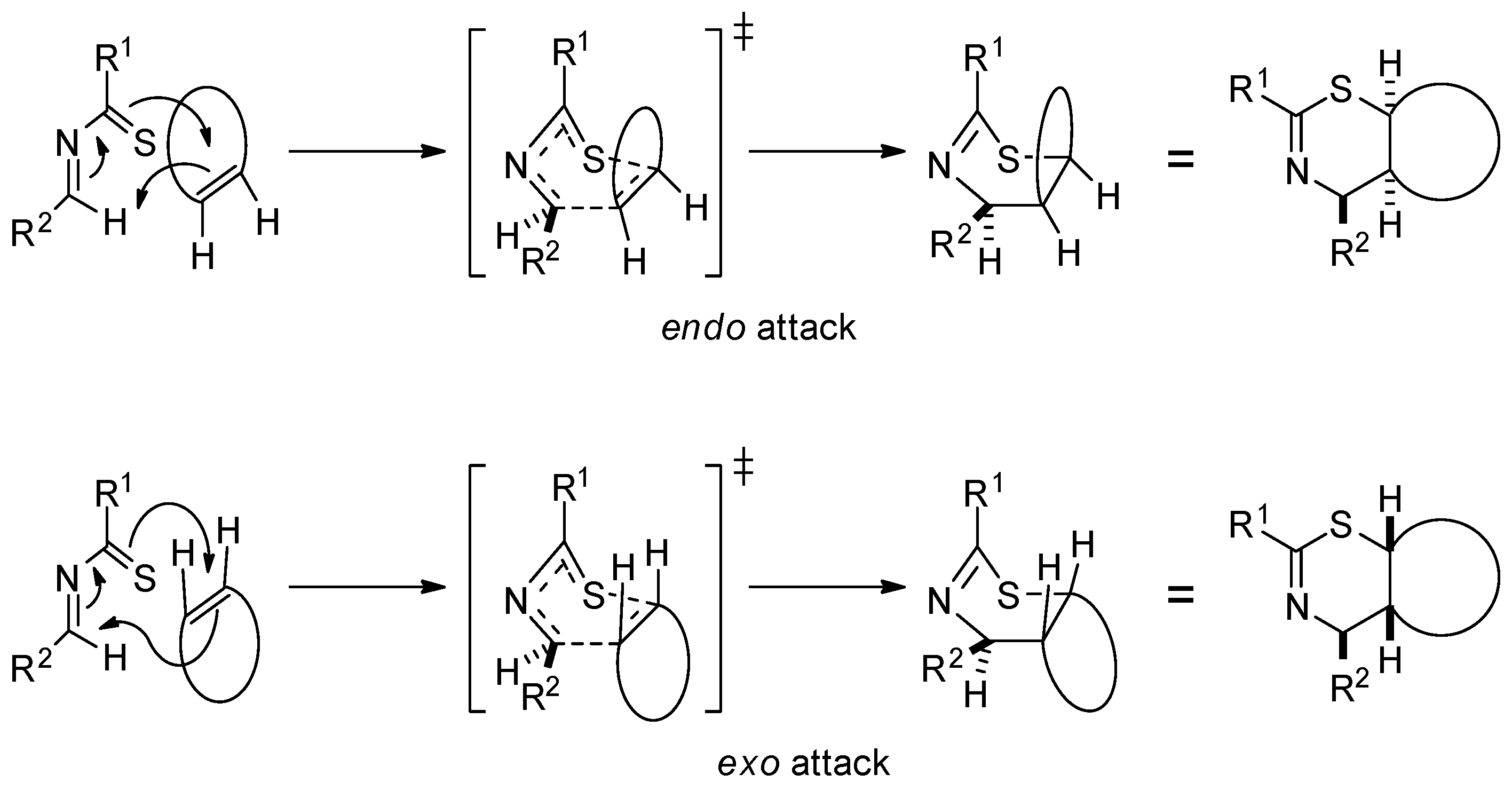

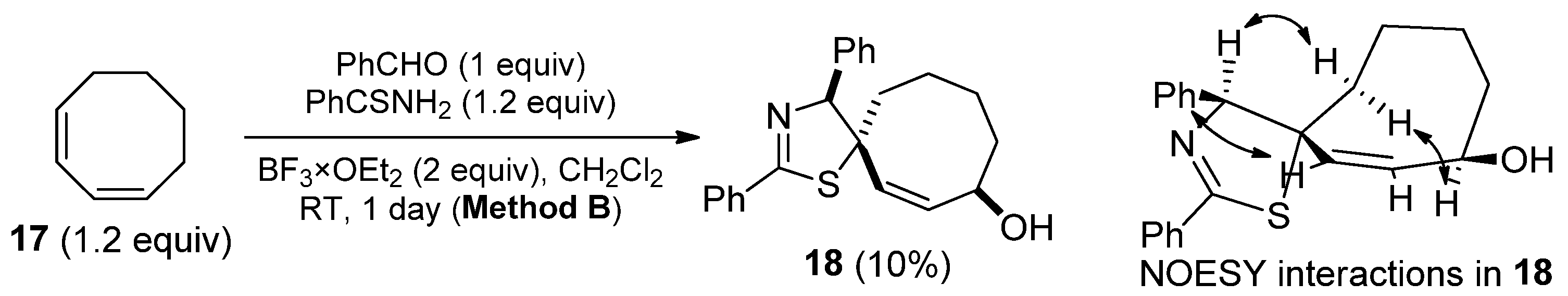

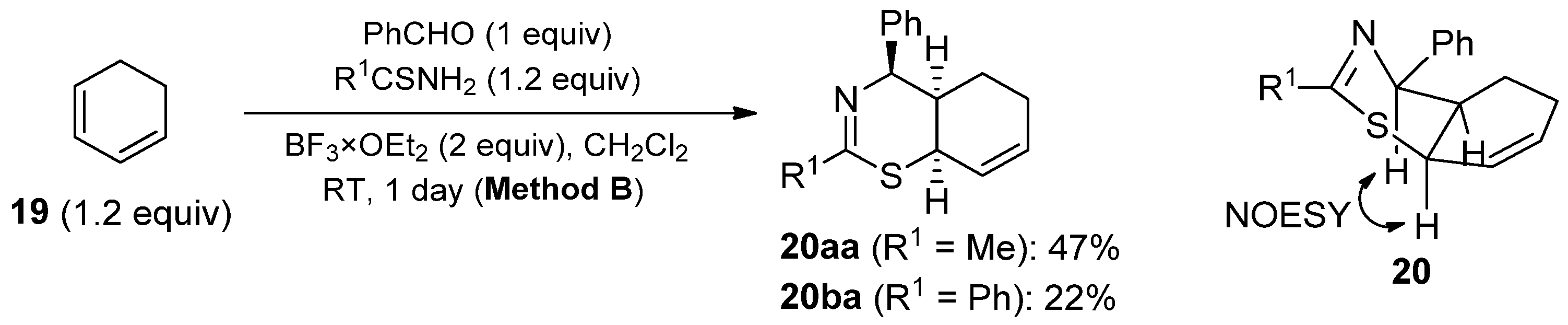

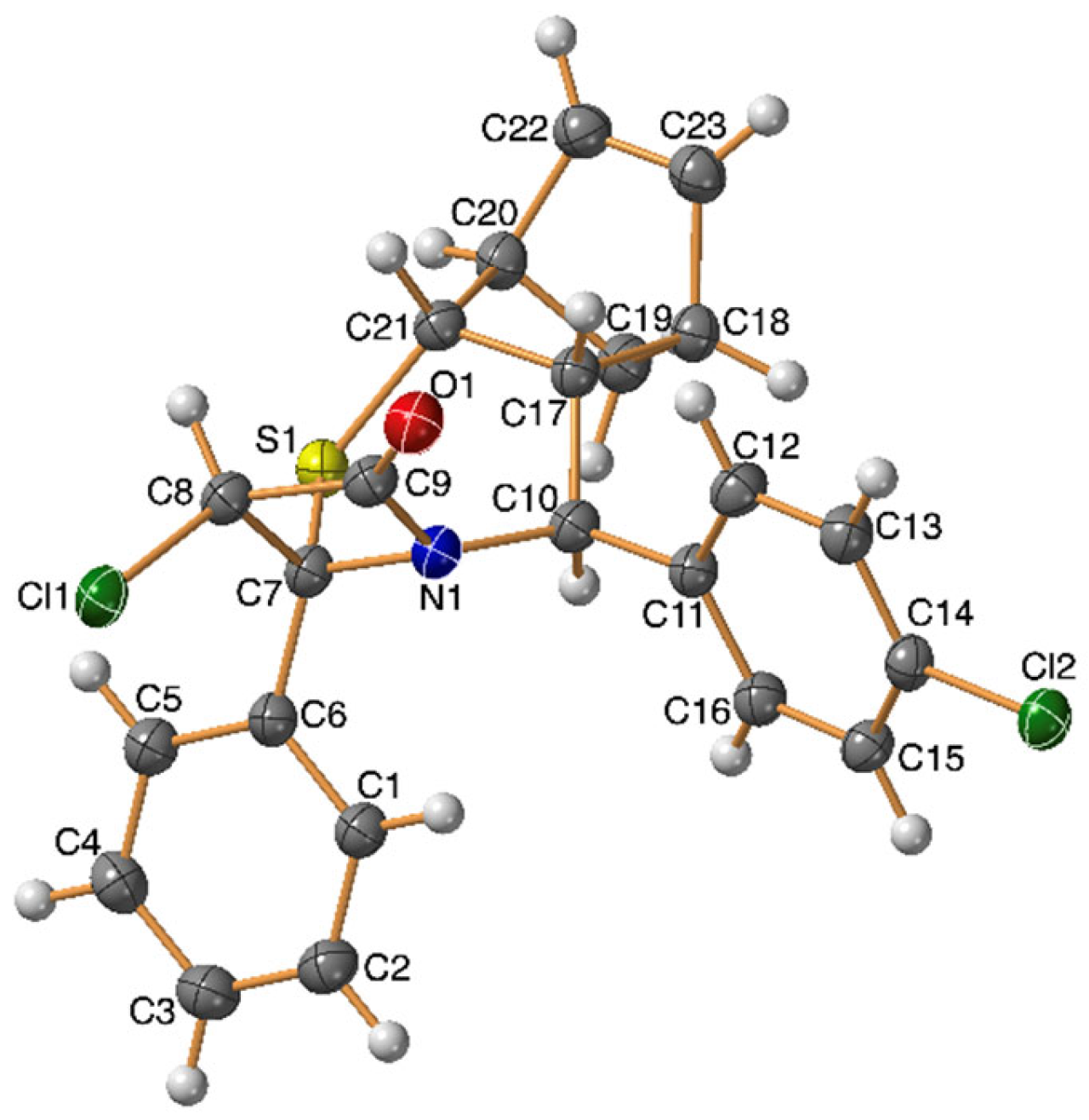

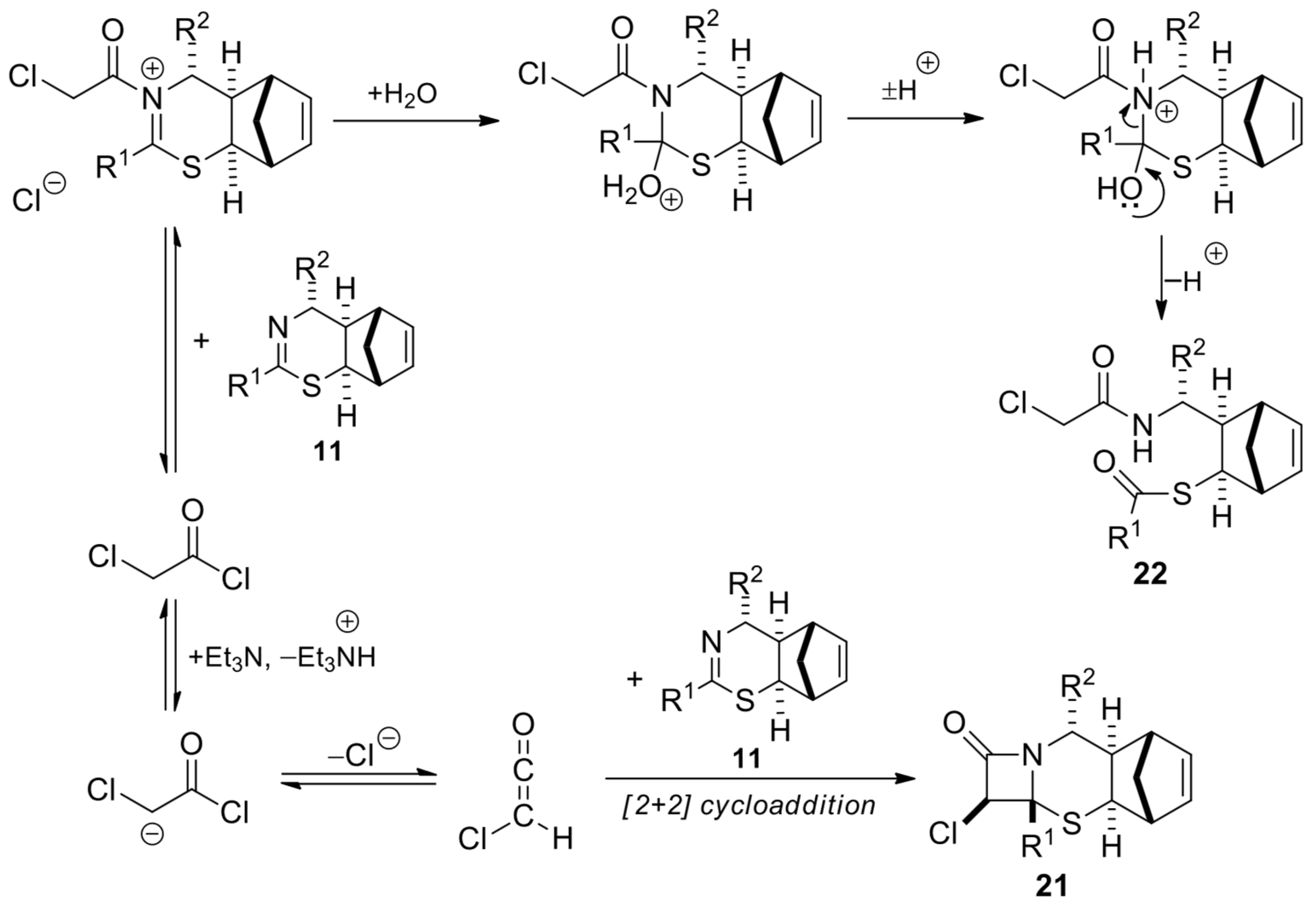

2. Results and Discussion

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. General Methods

3.2. General Methods for the Synthesis of Thiazines

3.3. General Method for the Staudinger Ketene–Imine Cycloaddition of Thiazines

3.4. General Method for the Ring Expansion of β-Lactam Condensed Thiazinanes

3.5. Characterization of Compounds

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Eicher, T.; Hauptmann, S.; Speicher, A. The Chemistry of Heterocycles: Structure, Reactions, Synthesis, and Applications, 3rd ed.; Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Aniszewski, T. Alkaloids: Chemistry, Biology, Ecology, and Applications, 2nd ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaku, E.; Smith, D.T.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of the Structural Diversity, Substitution Patterns, and Frequency of Nitrogen Heterocycles among U.S. FDA Approved Pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 2014, 57, 10257–10274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, C.M.; Federice, J.G.; Bell, C.N.; Cox, P.B.; Njardarson, J.T. An Update on the Nitrogen Heterocycle Compositions and Properties of U.S. FDA-Approved Pharmaceuticals (2013–2023). J. Med. Chem. 2024, 67, 11622–11655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomtsyan, A. Heterocycles in drugs and drug discovery. Chem. Heterocycl. Comp. 2012, 48, 7–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Ochomogo, M.; Lohans, C.T. β-Lactam antibiotic targets and resistance mechanisms: From covalent inhibitors to substrates. RSC Med. Chem. 2021, 12, 1623–1639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Śnieżek, M.; Stecko, S.; Panfil, I.; Furman, B.; Chmielewski, M. Total Synthesis of Ezetimibe, a Cholesterol Absorption Inhibitor. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 7048–7057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, K.A.; Njardarson, J.T. Analysis of US FDA-Approved Drugs Containing Sulfur Atoms. Top Curr. Chem. (Z) 2018, 376, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kapoor, K.; Kaur, N.; Sohal, H.S.; Kaur, M.; Singh, K.; Kumar, A. Drugs and Their Mode of Action: A Review on Sulfur-Containing Heterocyclic Compounds. Polycycl. Aromat. Compd. 2025, 45, 136–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Colón, K.; Chavez-Arias, C.; Díaz-Alcalá, J.E.; Martínez, M.A. Xylazine intoxication in humans and its importance as an emerging adulterant in abused drugs: A comprehensive review of the literature. Forensic Sci. Int. 2014, 240, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koketsu, M.; Tanaka, K.; Takenaka, Y.; Kwong, C.D.; Ishihara, H. Synthesis of 1,3-thiazine derivatives and their evaluation as potential antimycobacterial agents. Eur. J. Pharm. Sci. 2002, 15, 307–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matysiak, J. Synthesis, antiproliferative and antifungal activities of some 2-(2,4-dihydroxyphenyl)-4H-3,1-benzothiazines. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2006, 14, 2613–2619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiadomy, A.; Matysiak, J.; Karpińska, M.M. Synthesis and Anticancer Activity of New 2-Aryl-4H-3,1-benzothiazines. Arch. Pharm. Chem. Life Sci. 2011, 11, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Güschow, M.; Schlenk, M.; Gäb, J.; Paskaleva, M.; Alnouri, M.W.; Scolari, S.; Iqbal, J.; Müller, C.E. Benzothiazinones: A Novel Class of Adenosine Receptor Antagonists Structurally Unrelated to Xanthine and Adenine Derivatives. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 3331–3341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Fan, X.; Deng, J.; Liang, Y.; Ma, S.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shi, T.; Tan, W.; Wang, Z. Design and synthesis of 1,3-benzothiazinone derivatives as potential anti-inflammatory agents. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2020, 28, 115526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Min, Z.; Gao, Y.; Bian, J.; Lin, X.; He, J.; Ye, D.; Li, Y.; Peng, C.; Cheng, Y.; et al. Discovery of Novel Benzothiazepinones as Irreversible Covalent Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3β Inhibitors for the Treatment of Acute Promyelocytic Leukemia. J. Med. Chem. 2021, 64, 7341–7358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolau, S.M.; de Diego, A.M.G.; Cortés, L.; Egea, J.; González, J.C.; Mosquera, M.; López, M.G.; Hernández-Guijo, J.M.; García, A.G. Mitochondrial Na+/Ca2+-exchanger blocker CGP37157 protects against chromaffin cell death elicited by veratridine. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2009, 330, 844–854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitronova, G.Y.; Quentin, C.; Belov, V.N.; Wegener, J.W.; Kiszka, K.A.; Lehnart, S.E. 1,4-Benzothiazepines with Cyclopropanol Groups and Their Structural Analogues Exhibit Both RyR2-Stabilizing and SERCA2a-Stimulating Activities. J. Med. Chem. 2023, 66, 15761–15775. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, N.; Matsuda, R.; Hata, Y.; Shimamoto, K. Pharmacological characteristics and clinical applications of K201. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2009, 4, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wong, B.S.; Camilleri, M. Elobixibat for the treatment of constipation. Expert Opin. Investig. Drugs 2013, 22, 277–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalenić, K.; Ronse, U.; De Jonghe, S.; Persoons, L.; Schols, D.; De Munck, J.; Grootaert, C.; Van Camp, J.; D’hooghe, M. Synthesis and cancer cell cytotoxicity of 2-aryl-4-(4-aryl-2-oxobut-3-en-1-ylidene)-substituted benzothiazepanes. Phytochem. Lett. 2023, 55, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaneko, N.; Loughrey, C.M.; Smith, G.; Matsuda, R.; Hasunuma, T.; Mark, P.B.; Toda, M.; Shinozaki, M.; Otani, N.; Kayley, S.; et al. A novel ryanodine receptor 2 inhibitor, M201-A, enhances natriuresis, renal function and lusi-inotropic actions: Preclinical and phase I study. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2024, 181, 3401–3419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Free, R.B.; Nilson, A.N.; Boldizsar, N.M.; Doyle, T.B.; Rodriguiz, R.M.; Pogorelov, V.M.; Machino, M.; Lee, K.H.; Bertz, J.W.; Xu, J.; et al. Identification and Characterization of ML321: A Novel and Highly Selective D2 Dopamine Receptor Antagonist with Efficacy in Animal Models That Predict Atypical Antipsychotic Activity. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2023, 6, 151–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barcan, G.A.; Kwon, D.-H.; Guo, J.; Kowalski, J.A.; Liu, L.; Nilson, M.; Sisko, J.; Wang, H.; Brown, T.A.; Gholipour-Ranjbar, H. A Sulfur-Controlled Approach to the Synthesis of Linerixibat. J. Org. Chem. 2023, 88, 3970–3974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, X.; Gao, L.; Wang, L.; Liang, C.; Wang, B.; Liu, Y.; Feng, S.; Zhang, B.; Zhou, M.; Yu, X.; et al. Discovery of Ziresovir as a Potent, Selective, and Orally Bioavailable Respiratory Syncytial Virus Fusion Protein Inhibitor. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 62, 6003–6014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Q.; Cai, D.; Yan, R.; Li, L.; Zong, Y.; Guo, L.; Mercier, A.; Zhou, Y.; Tang, A.; Henne, K.; et al. Preclinical Profile and Characterization of the Hepatitis B Virus Core Protein Inhibitor ABI-H0731. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2020, 64, e01463-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harris, P.A.; Berger, S.B.; Jeong, J.U.; Nagilla, R.; Bandyopadhyay, D.; Campobasso, N.; Capriotti, C.A.; Cox, J.A.; Dare, L.; Dong, X.; et al. Discovery of a First-in-Class Receptor Interacting Protein 1 (RIP1) Kinase Specific Clinical Candidate (GSK2982772) for the Treatment of Inflammatory Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2017, 60, 1247–1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kent, C.N.; Fulton, M.G.; Stillwell, K.J.; Dickerson, J.W.; Loch, M.T.; Rodriguez, A.L.; Blobaum, A.L.; Boutaud, O.; Rook, J.L.; Niswender, C.M.; et al. Discovery and optimization of a novel CNS penetrant series of mGlu4 PAMs based on a 1,4-thiazepane core with in vivo efficacy in a preclinical Parkinsonian model. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2021, 37, 127838. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, L.; Szabó, J. Cycloaddition reactions of 1,3-benzothiazines–I. Reactions of 2-phenyl-4-H and 4-phenyl-2H-1,3-benzothiazine derivatives with substituted acetyl chlorides. Tetrahedron 1981, 37, 963–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, L.; Szabó, J.; Bernáth, G. Synthesis of 4,5-dihydro-1,4-benzothiazepine derivatives via ring expansion. Tetrahedron Lett. 1981, 22, 5077–5078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fodor, L.; Szabó, J.; Szűcs, E.; Bernáth, G.; Sohár, P.; Tamás, J. Ring transformations of 1,3-benzothiazine derivatives II. Conversion of 6α-aryl-7α-chloro-2,3(2′,3′-dialkoxybenzo)-1-thiaoctems into 2-carbomethoxy-3-aryl-7,8-dialkoxy-4,5-dihydro-1,4-benzothiazepines. Tetrahedron 1984, 40, 4089–4095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peudru, F.; Lohier, J.-F.; Gulea, M.; Reboul, V. Synthesis of 1,3-thiazines by a three-component reaction and their transformations into β-lactam-condensed 1,3-thiazine and 1,4-thiazepine derivatives. Phosphorus Sulfur Silicon Relat. Elem. 2016, 191, 220–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weichert, A.; Hoffman, H.M.R. Synthesis and Reactions of α-Methylene-β-keto Sulfones. J. Org. Chem. 1991, 56, 4098–4112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsiao, C.-C.; Raja, S.; Liao, H.-H.; Atodiresei, I.; Rueping, M. Ortho-Quinone Methides as Reactive Intermediates in Asymmetric Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Cycloadditions with Unactivated Alkenes by Exclusive Activation of the Electrophile. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 5762–5765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, W.D.; Du, M.; Royal, J.S.; McHale, J.L. Theoretical Study of the Charge-Transfer Spectrum of the Indene-Tetracyanoethylene Electron Donor-Acceptor Complex. J. Phys. Chem. 1990, 94, 5748–5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanessian, S.; Compain, P. Lewis acid promoted cyclocondensations of α-ketophosphonoenoates with dienes—From Diels–Alder to hetero Diels–Alder reactions. Tetrahedron 2002, 58, 6521–6529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clayden, J.; Greeves, N.; Warren, S.; Wothers, P. Organic Chemistry; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2009; p. 919. [Google Scholar]

- Sohár, P.; Szabó, J.; Simon, L.; Talpas, G.S.; Szűcs, E.; Bernáth, G. Synthesis and Steric Structure of Alicycle-Fused 1,3-Thiazine-β-lactams. Magn. Reson. Chem. 1991, 29, 687–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CrysAlisPro, version 1.171.38.41; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Inc.: Yarnton, UK, 2015.

- CrysAlisPro, version 1.171.42.90a; Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Inc.: Yarnton, UK, 2023.

- Sheldrick, G.M. SHELXT—Integrated space-group and crystal-structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. A 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldrick, G.M. Crystal structure refinement with SHELXL. Acta Crystallogr. C 2015, 71, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hübschle, C.B.; Sheldrick, G.M.; Dittrich, B. ShelXle: A Qt graphical user interface for SHELXL. J. Appl. Cryst. 2011, 44, 1281–1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

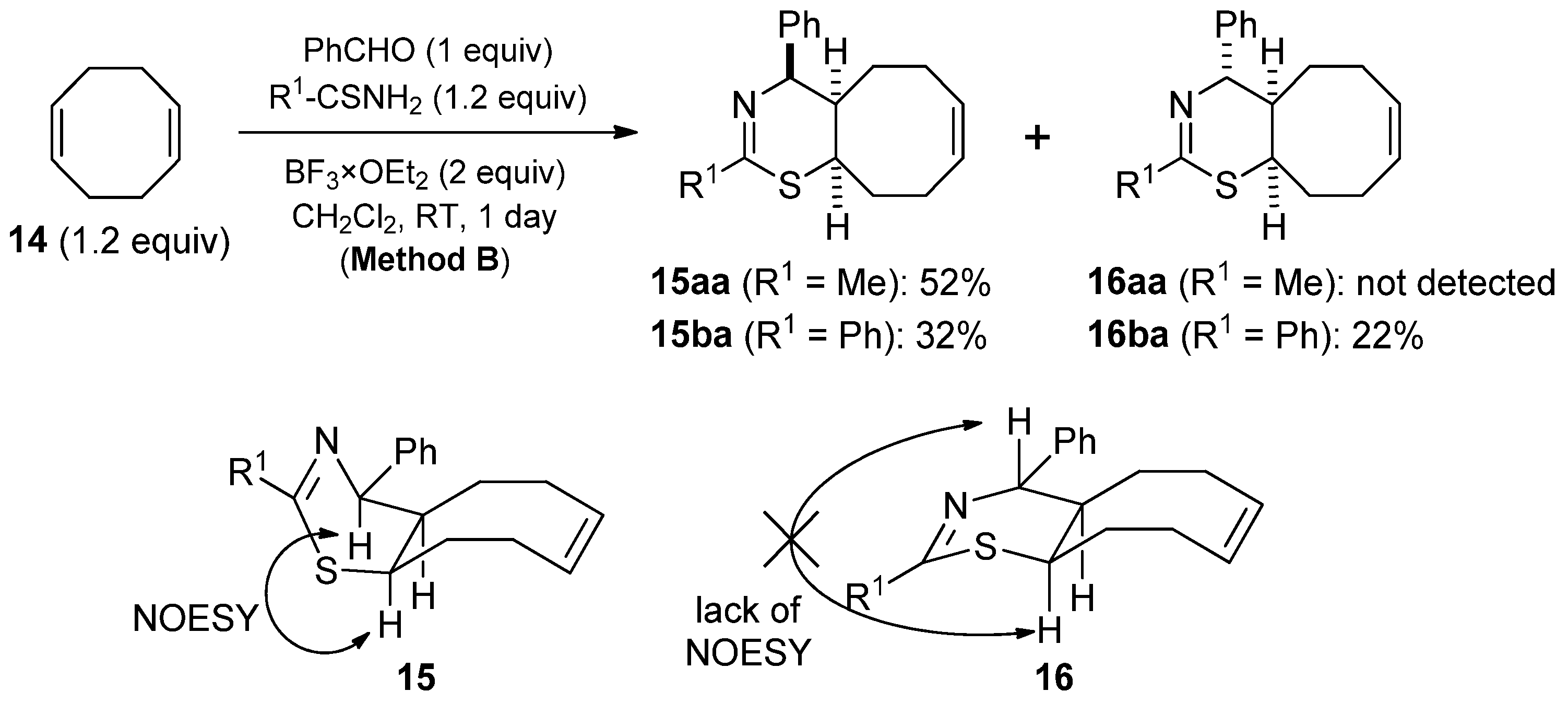

| Product | R1 | R2 | Yields (Method A) | Yields (Method B) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11aa | Me | Ph | 55% | 45% |

| 11ab | Me | 4-Cl-Ph | 56% | – |

| 11ba | Ph | Ph | 58% | 50% |

| 11bb | Ph | 4-Cl-Ph | 36% | 28% |

| Substrate | R1 | R2 | Yield of β-Lactam | Yield of Thioester |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11aa | Me | Ph | not formed | 46% 22aa |

| 11ab | Me | 4-Cl-Ph | 12% 21ab | 25% 22ab |

| 11ba | Ph | Ph | 58% 21ba | not formed |

| 11bb | Ph | 4-Cl-Ph | 56% 21bb | not formed |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Palkó, M.; Becker, N.; Wéber, E.; Haukka, M.; Remete, A.M. Synthesis of 1,3-Thiazine and 1,4-Thiazepine Derivatives via Cycloadditions and Ring Expansion. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311543

Palkó M, Becker N, Wéber E, Haukka M, Remete AM. Synthesis of 1,3-Thiazine and 1,4-Thiazepine Derivatives via Cycloadditions and Ring Expansion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311543

Chicago/Turabian StylePalkó, Márta, Nóra Becker, Edit Wéber, Matti Haukka, and Attila Márió Remete. 2025. "Synthesis of 1,3-Thiazine and 1,4-Thiazepine Derivatives via Cycloadditions and Ring Expansion" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311543

APA StylePalkó, M., Becker, N., Wéber, E., Haukka, M., & Remete, A. M. (2025). Synthesis of 1,3-Thiazine and 1,4-Thiazepine Derivatives via Cycloadditions and Ring Expansion. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11543. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311543