Modulating Cerebrospinal Fluid Composition in Neurodegenerative Processes: Modern Drug Delivery and Clearance Strategies

Abstract

1. Introduction

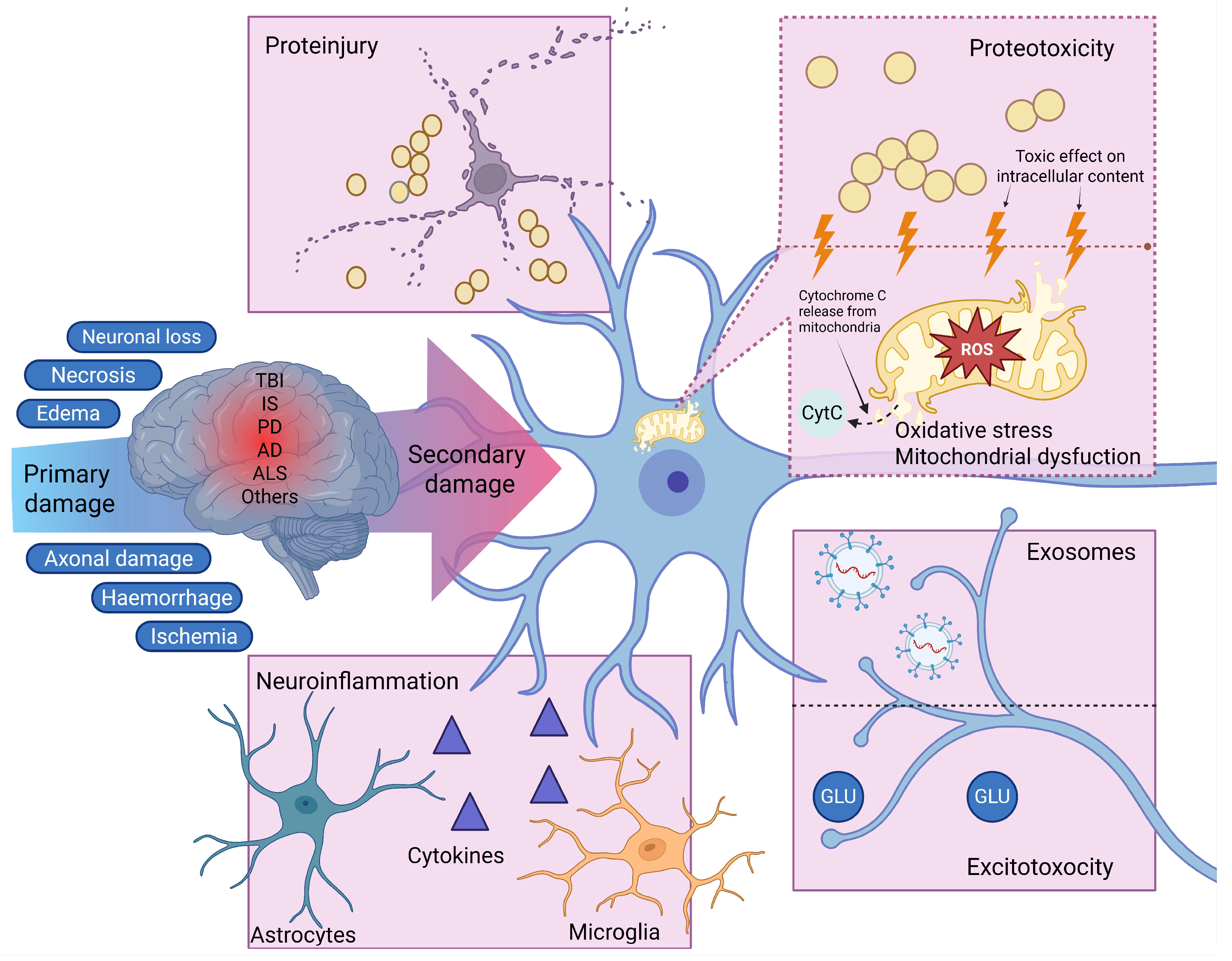

2. CSF as a Mediator of Secondary Injury

2.1. Oxidative Stress

2.2. Excitotoxicity and Disruption of Calcium Homeostasis

2.3. Neuroinflammation

2.4. Proteotoxic Stress and Proteinjury

2.5. The Role of CSF Exosomes in the Spread of Secondary Injury

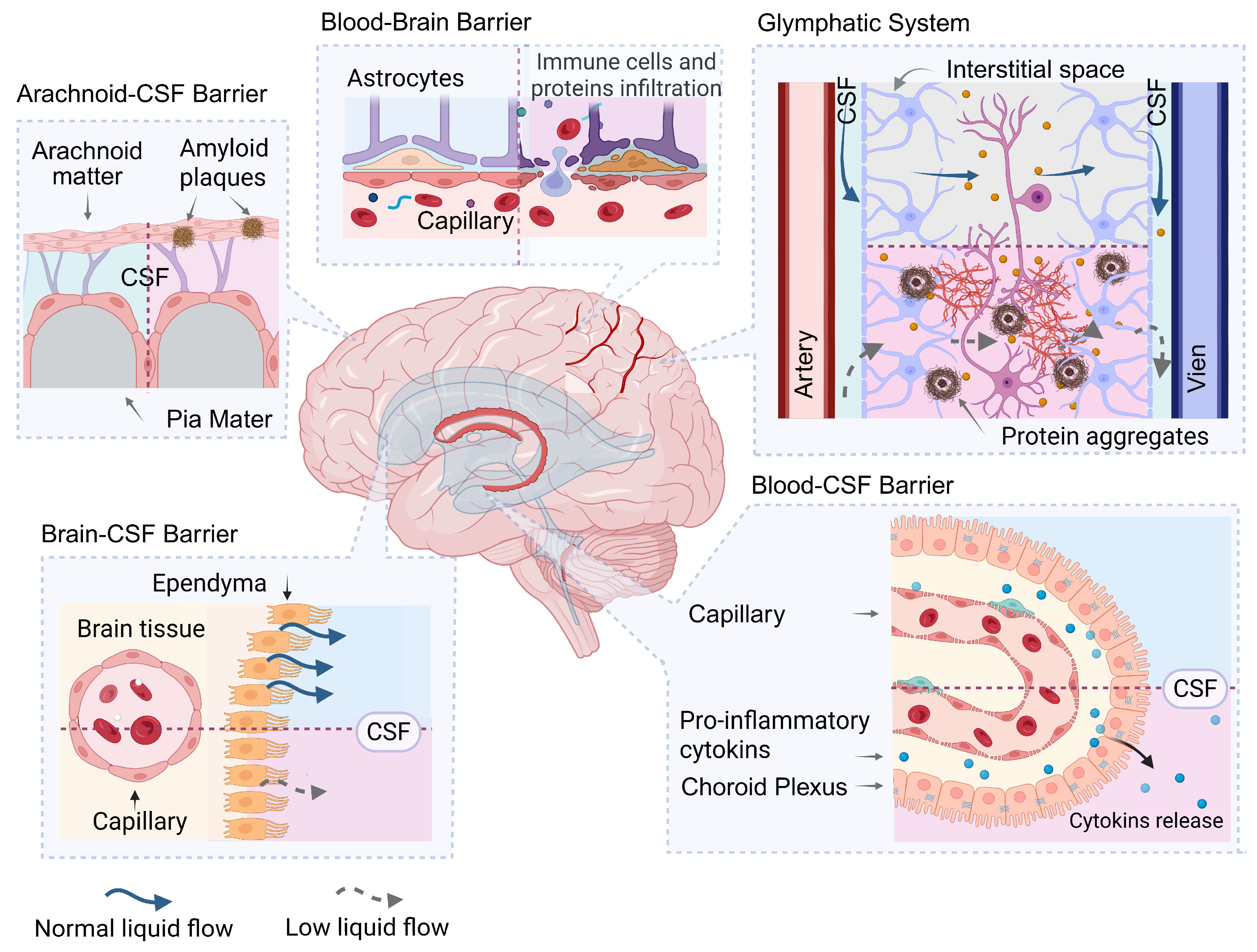

3. Barrier Systems Regulating Homeostasis in the CSF

- -

- isolating the CSF from cytotoxic proteins, proinflammatory cytokines, and other biomolecules that can damage brain tissue when released into the CSF;

- -

- clearing the CSF of cytotoxic proteins and their complexes, and other biological factors that cause secondary brain damage;

- -

- acting as a target for cytotoxic factors contained in the CSF or interstitial space, including pathogenic protein complexes, i.e., as a target for factors that cause secondary damage, including proteinjury.

3.1. Blood–Brain Barrier

3.2. Blood-CSF Barrier

3.3. CSF-Brain Barrier

3.4. Arachnoid and Pia Mater

3.5. Glymphatic System

4. CSF as an Object for Diagnostics

5. Modern Methods of Therapeutic Agents Delivering into the CSF

5.1. Non-Invasive Methods of Delivering Therapeutic Drugs

5.2. Nanoparticles as a Means of Drug Delivery to CSF

5.2.1. Gold Nanoparticles

5.2.2. Lipid-Based Nanoparticles

5.2.3. Polymer-Based Nanoparticles

5.2.4. Dendrimers

5.3. Monoclonal Therapeutic Antibodies

5.3.1. Bispecific Therapeutic Antibodies

5.3.2. Decoy-IgG Receptor Fusion Proteins

5.4. Invasive Technologies for Drug Delivery into the CSF

5.4.1. Immunoselective Nanopheresis and “Pseudodelivery” Through Nanoporous Membranes

5.4.2. Extracorporeal Liquopheresis as a Method of Systemic CSF Modulation

5.4.3. Convection-Enhanced Delivery

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AD | Alzheimer’s disease |

| ALS | Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis |

| AMPA | α-Amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid |

| APP | Amyloid-beta precursor protein |

| ARIA | Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities |

| AuNPs | Gold nanoparticles |

| BACE1 | Beta-site amyloid precursor protein-cleaving enzyme 1 |

| BBB | Blood-brain barrier |

| BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor |

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| CSF | Cerebrospinal fluid |

| DJ-1 | Protein deglycase DJ-1 (Parkinson’s disease protein 7) |

| ECD | Extracellular domain |

| EPO | Erythropoietin |

| FcRn | Neonatal Fc receptor |

| GAPDH | Glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GFAP | Glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GDNF | Glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| HIR | Human insulin receptor |

| HIRMAb | Human insulin receptor monoclonal antibody |

| IDUA | α-L-iduronidase |

| IDS | Iduronate-2-sulfatase |

| IgG | Immunoglobulin G |

| IL | Interleukin |

| LFP | Lateral fluid percussion (used contextually in TBI models) |

| LNPs | Lipid-based nanoparticles |

| mPTP | Mitochondrial permeability transition pore |

| MPS | Mucopolysaccharidosis |

| NDDs | Neurodegenerative diseases |

| NfH | Neurofilament heavy chain |

| NfL | Neurofilament light chain |

| NMDA | N-Methyl-D-aspartate |

| NPs | Nanoparticles |

| PLGA | Poly(lactic-co-glycolic acid) |

| PrPSc | Scrapie form of prion protein |

| RAGE | Receptor for advanced glycation end-products |

| ROS | Reactive oxygen species |

| RNS | Reactive nitrogen species |

| RT-QuIC | Real-time quaking-induced conversion |

| scFv | Single-chain variable fragment |

| SLNs | Solid lipid nanoparticles |

| SOD1 | Superoxide dismutase 1 |

| TBI | Traumatic brain injury |

| TDP-43 | TAR DNA-binding protein 43 |

| TfR | Transferrin receptor |

| TfRMAb | Transferrin receptor monoclonal antibody |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrosis factor alpha |

| TNFR | Tumor necrosis factor receptor |

| VSNL1 | Visinin-like protein 1 |

References

- Ioannidou, S.; Tsolaki, M.; Ginoudis, A.; Tamvakis, A.; Tsolaki, A.; Makedou, K.; Lymperaki, E. Oxidative Stress Biomarkers as Preclinical Markers of Mild Cognitive Impairment: The Impact of Age and Sex. J. Pers. Med. 2025, 15, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimmermann, M.; Brockmann, K. Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers of Inflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Park. Dis. 2022, 12, S183–S200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amerongen, S.; Das, S.; Kamps, S.; Goossens, J.; Bongers, B.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Vanmechelen, E.; Vijverberg, E.G.B.; Teunissen, C.E.; Verberk, I.M.W. Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers and Cognitive Trajectories in Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease and a History of Traumatic Brain Injury. Neurobiol. Aging 2024, 141, 121–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stampanoni Bassi, M.; Nuzzo, T.; Gilio, L.; Miroballo, M.; Casamassa, A.; Buttari, F.; Bellantonio, P.; Fantozzi, R.; Galifi, G.; Furlan, R.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Levels of L-Glutamate Signal Central Inflammatory Neurodegeneration in Multiple Sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 2021, 159, 857–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bagnato, S.; Boccagni, C. Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Biomarkers in Patients with Post-Traumatic Disorders of Consciousness: A Scoping Review. Brain Sci. 2023, 13, 364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, V.E.; Stewart, W.; Smith, D.H. Widespread Tau and Amyloid-Beta Pathology Many Years After a Single Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. Brain Pathol. 2012, 22, 142–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McKee, A.C.; Stein, T.D.; Nowinski, C.J.; Stern, R.A.; Daneshvar, D.H.; Alvarez, V.E.; Lee, H.S.; Hall, G.; Wojtowicz, S.M.; Baugh, C.M.; et al. The Spectrum of Disease in Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Brain 2013, 136, 43–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarev, V.F.; Alhasan, B.A.; Guzhova, I.V.; Margulis, B.A. “Proteinjury”: A Universal Pathological Mechanism Mediated by Cerebrospinal Fluid in Neurodegeneration and Trauma. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2025, 13, 1593122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeon, M.T.; Cogill, S.A.; Kim, K.S.; Kim, Y.; Kim, H.; Lee, C.Y.; Kim, S.; Son, S.; Kim, J.; Lee, J.; et al. TNF-α-NF-κB Activation through Pathological α-Synuclein Disrupts the BBB and Exacerbates Axonopathy. Cell Rep. 2025, 44, 116001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, N.; Miller, F.; Cazaubon, S.; Couraud, P.O. The Blood-Brain Barrier in Brain Homeostasis and Neurological Diseases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)-Biomembr. 2009, 1788, 842–857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutysheva, E.A.; Mikeladze, M.A.; Trestsova, M.A.; Aksenov, N.D.; Utepova, I.A.; Mikhaylova, E.R.; Suezov, R.V.; Charushin, V.N.; Chupakhin, O.N.; Guzhova, I.V.; et al. Pyrrolylquinoxaline-2-One Derivative as a Potent Therapeutic Factor for Brain Trauma Rehabilitation. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarev, V.F.; Dutysheva, E.A.; Komarova, E.Y.; Mikhaylova, E.R.; Guzhova, I.V.; Margulis, B.A. GAPDH-Targeted Therapy—A New Approach for Secondary Damage after Traumatic Brain Injury on Rats. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2018, 501, 1003–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutysheva, E.A.; Mikhaylova, E.R.; Trestsova, M.A.; Andreev, A.I.; Apushkin, D.Y.; Utepova, I.A.; Serebrennikova, P.O.; Akhremenko, E.A.; Aksenov, N.D.; Bon’, E.I.; et al. Combination of a Chaperone Synthesis Inducer and an Inhibitor of GAPDH Aggregation for Rehabilitation after Traumatic Brain Injury: A Pilot Study. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevigny, J.; Chiao, P.; Bussière, T.; Weinreb, P.H.; Williams, L.; Maier, M.; Dunstan, R.; Salloway, S.; Chen, T.; Ling, Y.; et al. The Antibody Aducanumab Reduces Aβ Plaques in Alzheimer’s Disease. Nature 2016, 537, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congdon, E.E.; Sigurdsson, E.M. Tau-Targeting Therapies for Alzheimer Disease. Nat. Rev. Neurol. 2018, 14, 399–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, D.L.; Piani-Meier, D.; Bar-Or, A.; Benedict, R.H.B.; Cree, B.A.C.; Giovannoni, G.; Gold, R.; Vermersch, P.; Arnould, S.; Dahlke, F.; et al. Effect of Siponimod on Magnetic Resonance Imaging Measures of Neurodegeneration and Myelination in Secondary Progressive Multiple Sclerosis: Gray Matter Atrophy and Magnetization Transfer Ratio Analyses from the EXPAND Phase 3 Trial. Mult. Scler. 2022, 28, 1526–1540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz-Ballester, C.; Mahmutovic, D.; Rafiqzad, Y.; Korot, A.; Robel, S. Mild Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Disruption of the Blood-Brain Barrier Triggers an Atypical Neuronal Response. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2022, 16, 821885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, L.; Chen, M.; Margolin, E. Transsynaptic Ganglion Cell Degeneration in Adult Patients After Occipital Lobe Stroke. J. Neuroophthalmol. 2023, 43, 243–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massaad, C.A.; Klann, E. Reactive Oxygen Species in the Regulation of Synaptic Plasticity and Memory. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2011, 14, 2013–2054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Rodriguez, A.; Egea-Guerrero, J.; Murillo-Cabezas, F.; Carrillo-Vico, A. Oxidative Stress in Traumatic Brain Injury. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 1201–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mecocci, P.; Beal, M.F.; Cecchetti, R.; Polidori, M.C.; Cherubini, A.; Chionne, F.; Avellini, L.; Romano, G.; Senin, U. Mitochondrial Membrane Fluidity and Oxidative Damage to Mitochondrial DNA in Aged and AD Human Brain. Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 1997, 31, 53–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schippling, S.; Kontush, A.; Arlt, S.; Buhmann, C.; Stürenburg, H.J.; Mann, U.; Müller-Thomsen, T.; Beisiegel, U. Increased Lipoprotein Oxidation in Alzheimer’s Disease. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, J.; Jones, D.P. Superoxide in Apoptosis. J. Biol. Chem. 1998, 273, 11401–11404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cristofori, L.; Tavazzi, B.; Gambin, R.; Vagnozzi, R.; Vivenza, C.; Amorini, A.M.; Di Pierro, D.; Fazzina, G.; Lazzarino, G. Early Onset of Lipid Peroxidation after Human Traumatic Brain Injury: A Fatal Limitation for the Free Radical Scavenger Pharmacological Therapy? J. Investig. Med. 2001, 49, 450–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, P.; Fei, F.; Zhang, L.; Qu, Y.; Fei, Z. The Role of Glutamate Receptors in Traumatic Brain Injury: Implications for Postsynaptic Density in Pathophysiology. Brain Res. Bull. 2011, 85, 313–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Somayaji, M.R.; Przekwas, A.J.; Gupta, R.K. Combination Therapy for Multi-Target Manipulation of Secondary Brain Injury Mechanisms. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2017, 15, 484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olby, N.J.; Sharp, N.J.H.; Muñana, K.R.; Papich, M.G. Chronic and Acute Compressive Spinal Cord Lesions in Dogs Due to Intervertebral Disc Herniation Are Associated with Elevation in Lumbar Cerebrospinal Fluid Glutamate Concentration. J. Neurotrauma 1999, 16, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chiang, M.F.; Chiu, W.T.; Lin, F.J.; Thajeb, P.; Huang, C.J.; Tsai, S.H. Multiparametric Analysis of Cerebral Substrates and Nitric Oxide Delivery in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Patients with Intracerebral Haemorrhage: Correlation with Hemodynamics and Outcome. Acta Neurochir. 2006, 148, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, B.; Hye, A.; Snowden, S.G. Metabolic Modifications in Human Biofluids Suggest the Involvement of Sphingolipid, Antioxidant, and Glutamate Metabolism in Alzheimer’s Disease Pathogenesis. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2015, 46, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Costantini, T.W.; D’Mello, R.; Eliceiri, B.P.; Coimbra, R.; Bansal, V. Altering Leukocyte Recruitment Following Traumatic Brain Injury with Ghrelin Therapy. J. Trauma. Acute Care Surg. 2014, 77, 709–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinson, H.E.; Rowell, S.; Schreiber, M. Clinical Evidence of Inflammation Driving Secondary Brain Injury: A Systematic Review. J. Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015, 78, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gigase, F.A.J.; Smith, E.; Collins, B.; Moore, K.; Snijders, G.J.L.J.; Katz, D.; Bergink, V.; Perez-Rodriquez, M.M.; De Witte, L.D. The Association between Inflammatory Markers in Blood and Cerebrospinal Fluid: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Mol. Psychiatry 2023, 28, 1502–1515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Errico, F.; Gilio, L.; Mancini, A.; Nuzzo, T.; Bassi, M.S.; Bellingacci, L.; Buttari, F.; Dolcetti, E.; Bruno, A.; Galifi, G.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid, Brain, and Spinal Cord Levels of L-Aspartate Signal Excitatory Neurotransmission Abnormalities in Multiple Sclerosis Patients and Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis Mouse Model. J. Neurochem. 2023, 166, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabirov, D.; Ogurcov, S.; Shulman, I.; Kabdesh, I.; Garanina, E.; Sufianov, A.; Rizvanov, A.; Mukhamedshina, Y. Comparative Analysis of Cytokine Profiles in Cerebrospinal Fluid and Blood Serum in Patients with Acute and Subacute Spinal Cord Injury. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, C.; Shi, J.-X.; Li, J.-S.; Wu, W.; Yin, H. Concomitant Upregulation of Nuclear Factor-KB Activity, Proinflammatory Cytokines and ICAM-1 in the Injured Brain after Cortical Contusion Trauma in a Rat Model. Neurol. India 2005, 53, 312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gertje, E.C.; Janelidze, S.; van Westen, D.; Cullen, N.; Stomrud, E.; Palmqvist, S.; Hansson, O.; Mattsson-Carlgren, N. Associations Between CSF Markers of Inflammation, White Matter Lesions, and Cognitive Decline in Individuals Without Dementia. Neurology 2023, 100, e1812–e1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aisiku, I.P.; Yamal, J.M.; Doshi, P.; Benoit, J.S.; Gopinath, S.; Goodman, J.C.; Robertson, C.S. Plasma Cytokines IL-6, IL-8, and IL-10 Are Associated with the Development of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Patients with Severe Traumatic Brain Injury. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Yin, Y.; Du, L. FUS Aggregation Following Ischemic Stroke Favors Brain Astrocyte Activation through Inducing Excessive Autophagy. Exp. Neurol. 2022, 355, 114144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Anca, M.; Fenoglio, C.; Serpente, M.; Arosio, B.; Cesari, M.; Scarpini, E.A.; Galimberti, D. Exosome Determinants of Physiological Aging and Age-Related Neurodegenerative Diseases. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2019, 11, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anagnostou, D.; Sfakianaki, G.; Melachroinou, K.; Soutos, M.; Constantinides, V.; Vaikath, N.; Tsantzali, I.; Paraskevas, G.P.; Agnaf, O.E.; Vekrellis, K.; et al. Assessment of Aggregated and Exosome-Associated α-Synuclein in Brain Tissue and Cerebrospinal Fluid Using Specific Immunoassays. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chopra, A.; Outeiro, T.F. Aggregation and beyond: Alpha-Synuclein-Based Biomarkers in Synucleinopathies. Brain 2024, 147, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saman, S.; Kim, W.H.; Raya, M.; Visnick, Y.; Miro, S.; Saman, S.; Jackson, B.; McKee, A.C.; Alvarez, V.E.; Lee, N.C.Y.; et al. Exosome-Associated Tau Is Secreted in Tauopathy Models and Is Selectively Phosphorylated in Cerebrospinal Fluid in Early Alzheimer Disease. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 3842–3849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eitan, E.; Hutchison, E.R.; Marosi, K.; Comotto, J.; Mustapic, M.; Nigam, S.M.; Suire, C.; Maharana, C.; Jicha, G.A.; Liu, D.; et al. Extracellular Vesicle-Associated Aβ Mediates Trans-Neuronal Bioenergetic and Ca2+-Handling Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease Models. NPJ Aging Mech. Dis. 2016, 2, 16019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Wang, H.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Sun, Z.; Zhao, S.; Kong, W.; Sun, W.; Wang, C.; Feng, L. Therapeutic Potential of Plant-Derived Exosome-like Nanoparticles for CNS Diseases: Advancements in Preparation and Characterization. Ann. Med. 2025, 57, 2537345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verderio, C.; Muzio, L.; Turola, E.; Bergami, A.; Novellino, L.; Ruffini, F.; Riganti, L.; Corradini, I.; Francolini, M.; Garzetti, L.; et al. Myeloid Microvesicles Are a Marker and Therapeutic Target for Neuroinflammation. Ann. Neurol. 2012, 72, 610–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, S.; Zhou, X.; Yang, Z.H.; Si, X.K.; Sun, X. Stroke-Induced Damage on the Blood-Brain Barrier. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1248970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Canepa, E.; Fossati, S. Impact of Tau on Neurovascular Pathology in Alzheimer’s Disease. Front. Neurol. 2021, 11, 573324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Man, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yao, G.; Chen, J. Medial Prefrontal Cortex Oxytocin Mitigates Epilepsy and Cognitive Impairments Induced by Traumatic Brain Injury through Reducing Neuroinflammation in Mice. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 5214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hay, J.R.; Johnson, V.E.; Young, A.M.H.; Smith, D.H.; Stewart, W. Blood-Brain Barrier Disruption Is an Early Event That May Persist for Many Years After Traumatic Brain Injury in Humans. J. Neuropathol. Exp. Neurol. 2015, 74, 1147–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamson, E.E.; Ikonomovic, M.D. Brain Injury-Induced Dysfunction of the Blood Brain Barrier as a Risk for Dementia. Exp. Neurol. 2020, 328, 113257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nation, D.A.; Sweeney, M.D.; Montagne, A.; Sagare, A.P.; D’Orazio, L.M.; Pachicano, M.; Sepehrband, F.; Nelson, A.R.; Buennagel, D.P.; Harrington, M.G.; et al. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown Is an Early Biomarker of Human Cognitive Dysfunction. Nat. Med. 2019, 25, 270–276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moon, Y.; Jeon, H.J.; Han, S.H.; Min-Young, N.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, K.J.; Moon, W.J.; Kim, S.H. Blood-Brain Barrier Breakdown Is Linked to Tau Pathology and Neuronal Injury in a Differential Manner According to Amyloid Deposition. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2023, 43, 1813–1825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharya, N.K.; Grossman, H.C.; Clifford, P.M.; Levin, E.C.; Light, K.R.; Choi, H.; Swanson II, R.L.; Kosciuk, M.C.; Venkataraman, V.; Libon, D.J.; et al. A Chronic Increase in Blood-Brain Barrier Permeability Facilitates Intraneuronal Deposition of Exogenous Bloodborne Amyloid-Beta1-42 Peptide in the Brain and Leads to Alzheimer’s Disease-Relevant Cognitive Changes in a Mouse Model. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2024, 98, 163–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hourfar, H.; Aliakbari, F.; Aqdam, S.R.; Nayeri, Z.; Bardania, H.; Otzen, D.E.; Morshedi, D. The Impact of α-Synuclein Aggregates on Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity in the Presence of Neurovascular Unit Cells. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 229, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheemala, A.; Kimble, A.L.; Tyburski, J.D.; Leclair, N.K.; Zuberi, A.R.; Murphy, M.; Jellison, E.R.; Reese, B.; Hu, X.; Lutz, C.M.; et al. Loss of Endothelial TDP-43 Leads to Blood Brain Barrier Defects in Mouse Models of Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis and Frontotemporal Dementia. bioRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parodi-Rullán, R.; Ghiso, J.; Cabrera, E.; Rostagno, A.; Fossati, S. Alzheimer’s Amyloid β Heterogeneous Species Differentially Affect Brain Endothelial Cell Viability, Blood-Brain Barrier Integrity, and Angiogenesis. Aging Cell 2020, 19, e13258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosas-Hernandez, H.; Cuevas, E.; Raymick, J.B.; Robinson, B.L.; Sarkar, S. Impaired Amyloid Beta Clearance and Brain Microvascular Dysfunction Are Present in the Tg-SwDI Mouse Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Neuroscience 2020, 440, 48–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tumani, H.; Huss, A.; Bachhuber, F. The Cerebrospinal Fluid and Barriers—Anatomic and Physiologic Considerations. Handb. Clin. Neurol. 2018, 146, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johanson, C.E.; Stopa, E.G.; McMillan, P.N. The Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier: Structure and Functional Significance. Methods Mol. Biol. 2011, 686, 101–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Gan, L.; Cao, F.; Wang, H.; Gong, P.; Ma, C.; Ren, L.; Lin, Y.; Lin, X. The Barrier and Interface Mechanisms of the Brain Barrier, and Brain Drug Delivery. Brain Res. Bull. 2022, 190, 69–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saunders, N.R.; Dziegielewska, K.M.; Fame, R.M.; Lehtinen, M.K.; Liddelow, S.A. The Choroid Plexus: A Missing Link in Our Understanding of Brain Development and Function. Physiol. Rev. 2023, 103, 919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zuo, Z. Impact of Transporters and Enzymes from Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier and Brain Parenchyma on CNS Drug Uptake. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2018, 14, 961–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huttunen, K.M.; Terasaki, T.; Urtti, A.; Montaser, A.B.; Uchida, Y. Pharmacoproteomics of Brain Barrier Transporters and Substrate Design for the Brain Targeted Drug Delivery. Pharm. Res. 2022, 39, 1363–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hutton, D.; Fadelalla, M.G.; Kanodia, A.K.; Hossain-Ibrahim, K. Choroid Plexus and CSF: An Updated Review. Br. J. Neurosurg. 2022, 36, 307–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silverberg, G.D.; Heit, G.; Huhn, S.; Jaffe, R.A.; Chang, S.D.; Bronte-Stewart, H.; Rubenstein, E.; Possin, K.; Saul, T.A. The Cerebrospinal Fluid Production Rate Is Reduced in Dementia of the Alzheimer’s Type. Neurology 2001, 57, 1763–1766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vargas, T.; Ugalde, C.; Spuch, C.; Antequera, D.; Morán, M.J.; Martín, M.A.; Ferrer, I.; Bermejo-Pareja, F.; Carro, E. Abeta Accumulation in Choroid Plexus is Associated with Mitochondrial-Induced Apoptosis. Neurobiol. Aging 2010, 31, 1569–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čarna, M.; Onyango, I.G.; Katina, S.; Holub, D.; Novotny, J.S.; Nezvedova, M.; Jha, D.; Nedelska, Z.; Lacovich, V.; Vyvere, T.V.; et al. Pathogenesis of Alzheimer’s Disease: Involvement of the Choroid Plexus. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2023, 19, 3537–3554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brkic, M.; Balusu, S.; Van Wonterghem, E.; Gorlé, N.; Benilova, I.; Kremer, A.; Van Hove, I.; Moons, L.; De Strooper, B.; Kanazir, S.; et al. Amyloid β Oligomers Disrupt Blood-CSF Barrier Integrity by Activating Matrix Metalloproteinases. J. Neurosci. 2015, 35, 12766–12778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ott, B.R.; Jones, R.N.; Daiello, L.A.; de la Monte, S.M.; Stopa, E.G.; Johanson, C.E.; Denby, C.; Grammas, P. Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Gradients in Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer’s Disease: Relationship to Inflammatory Cytokines and Chemokines. Front. Aging Neurosci. 2018, 10, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seeliger, T.; Gingele, S.; Güzeloglu, Y.E.; Heitmann, L.; Lüling, B.; Kohle, F.; Preßler, H.; Stascheit, F.; Motte, J.; Fisse, A.L.; et al. Comparative Analysis of Albumin Quotient and Total CSF Protein in Immune-Mediated Neuropathies: A Multicenter Study on Diagnostic Implications. Front. Neurol. 2024, 14, 1330484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szmydynger-Chodobska, J.; Gandy, J.R.; Varone, A.; Shan, R.; Chodobski, A. Synergistic Interactions between Cytokines and AVP at the Blood-CSF Barrier Result in Increased Chemokine Production and Augmented Influx of Leukocytes after Brain Injury. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e79328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ge, R.; Tornero, D.; Hirota, M.; Monni, E.; Laterza, C.; Lindvall, O.; Kokaia, Z. Choroid Plexus-Cerebrospinal Fluid Route for Monocyte-Derived Macrophages after Stroke. J. Neuroinflamm. 2017, 14, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.S.; Johanson, C.E. Intracerebroventricularly Administered Neurotrophins Attenuate Blood Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Breakdown and Brain Pathology Following Whole-Body Hyperthermia: An Experimental Study in the Rat Using Biochemical and Morphological Approaches. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2007, 1122, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, H.S.; Zimmermann-Meinzingen, S.; Johanson, C.E. Cerebrolysin Reduces Blood-Cerebrospinal Fluid Barrier Permeability Change, Brain Pathology, and Functional Deficits Following Traumatic Brain Injury in the Rat. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2010, 1199, 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lazarevic, I.; Soldati, S.; Mapunda, J.A.; Rudolph, H.; Rosito, M.; de Oliveira, A.C.; Enzmann, G.; Nishihara, H.; Ishikawa, H.; Tenenbaum, T.; et al. The Choroid Plexus Acts as an Immune Cell Reservoir and Brain Entry Site in Experimental Autoimmune Encephalomyelitis. Fluids Barriers CNS 2023, 20, 39, Correction in Fluids Barriers CNS 2023, 20, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serra, R.; Simard, J.M. Adherens, Tight, and Gap Junctions in Ependymal Cells: A Systematic Review of Their Contribution to CSF-Brain Barrier. Front. Neurol. 2023, 14, 1092205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hatta, K.; Takagi, S.; Fujisawa, H.; Takeichi, M. Spatial and Temporal Expression Pattern of N-Cadherin Cell Adhesion Molecules Correlated with Morphogenetic Processes of Chicken Embryos. Dev. Biol. 1987, 120, 215–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Piontek, J.; Wolburg, H.; Piehl, C.; Liss, M.; Otten, C.; Christ, A.; Willnow, T.E.; Blasig, I.E.; Abdelilah-Seyfried, S. Establishment of a Neuroepithelial Barrier by Claudin5a Is Essential for Zebrafish Brain Ventricular Lumen Expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2010, 107, 1425–1430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sival, D.A.; Guerra, M.; Den Dunnen, W.F.A.; Bátiz, L.F.; Alvial, G.; Castañeyra-Perdomo, A.; Rodríguez, E.M. Neuroependymal Denudation Is in Progress in Full-Term Human Foetal Spina Bifida Aperta. Brain Pathol. 2011, 21, 163–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, M.J.; Park, Y.H.; Kim, S.; Yi, S. Hydrocephalus in a Patient with Alzheimer’s Disease. Dement. Neurocogn. Disord. 2018, 17, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, C.H. Differential Diagnosis of Parkinson’s Disease. Med. Clin. N. Am. 1999, 83, 349–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.H.; Lee, C.P.; Yang, Y.H.; Yang, Y.H.; Chen, C.M.; Lu, M.L.; Lee, Y.C.; Chen, V.C.H. Incidence of Hydrocephalus in Traumatic Brain Injury: A Nationwide Population-Based Cohort Study. Medicine 2019, 98, e17568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saugier-Veber, P.; Marguet, F.; Lecoquierre, F.; Adle-Biassette, H.; Guimiot, F.; Cipriani, S.; Patrier, S.; Brasseur-Daudruy, M.; Goldenberg, A.; Layet, V.; et al. Hydrocephalus Due to Multiple Ependymal Malformations Is Caused by Mutations in the MPDZ Gene. Acta Neuropathol. Commun. 2017, 5, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, G.; Elkind, J.A.; Kundu, S.; Smith, C.J.; Antunes, M.B.; Tamashiro, E.; Kofonow, J.M.; Mitala, C.M.; Stein, S.C.; Grady, M.S.; et al. Traumatic Brain Injury-Induced Ependymal Ciliary Loss Decreases Cerebral Spinal Fluid Flow. J. Neurotrauma 2014, 31, 1396, Correction in J. Neurotrauma 2015, 32, 287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maslinska, D.; Laure-Kamionowska, M.; Taraszewska, A.; Deregowski, K.; Maslinski, S. Immunodistribution of Amyloid Beta Protein (Aβ) and Advanced Glycation End-Product Receptors (RAGE) in Choroid Plexus and Ependyma of Resuscitated Patients. Folia Neuropathol. 2011, 49, 295–300. [Google Scholar]

- Go, K.G. The Normal and Pathological Physiology of Brain Water. Adv. Tech. Stand. Neurosurg. 1997, 23, 47–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeeb, N.; Deep, A.; Griessenauer, C.J.; Mortazavi, M.M.; Watanabe, K.; Loukas, M.; Tubbs, R.S.; Cohen-Gadol, A.A. The Intracranial Arachnoid Mater: A Comprehensive Review of Its History, Anatomy, Imaging, and Pathology. Childs Nerv. Syst. 2013, 29, 17–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiyama, H.; Yamada, T.; McGeer, P.L.; Kawamata, T.; Tooyama, I.; Ishii, T. Columnar Arrangement of Beta-Amyloid Protein Deposits in the Cerebral Cortex of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease. Acta Neuropathol. 1993, 85, 400–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, R.A. A Comparison of the Spatial Patterns of β-Amyloid (Aβ) Deposits in Five Neurodegenerative Disorders. Folia Neuropathol. 2018, 56, 284–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iliff, J.J.; Wang, M.; Liao, Y.; Plogg, B.A.; Peng, W.; Gundersen, G.A.; Benveniste, H.; Vates, G.E.; Deane, R.; Goldman, S.A.; et al. A Paravascular Pathway Facilitates CSF Flow through the Brain Parenchyma and the Clearance of Interstitial Solutes, Including Amyloid β. Sci. Transl. Med. 2012, 4, 147ra111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Kress, B.T.; Weber, H.J.; Thiyagarajan, M.; Wang, B.; Deane, R.; Benveniste, H.; Iliff, J.J.; Nedergaard, M. Evaluating Glymphatic Pathway Function Utilizing Clinically Relevant Intrathecal Infusion of CSF Tracer. J. Transl. Med. 2013, 11, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naganawa, S.; Taoka, T. The Glymphatic System: A Review of the Challenges in Visualizing Its Structure and Function with MR Imaging. Magn. Reson. Med. Sci. 2022, 21, 182–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, M.; Wang, M.X.; Ismail, O.; Braun, M.; Schindler, A.G.; Reemmer, J.; Wang, Z.; Haveliwala, M.A.; O’Boyle, R.P.; Han, W.Y.; et al. Loss of Perivascular Aquaporin-4 Localization Impairs Glymphatic Exchange and Promotes Amyloid β Plaque Formation in Mice. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2022, 14, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nedergaard, M.; Goldman, S.A. Glymphatic Failure as a Final Common Pathway to Dementia. Science 2020, 370, 50–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kress, B.T.; Iliff, J.J.; Xia, M.; Wang, M.; Wei Bs, H.S.; Zeppenfeld, D.; Xie, L.; Hongyi Kang, B.S.; Xu, Q.; Liew, J.A.; et al. Impairment of Paravascular Clearance Pathways in the Aging Brain. Ann. Neurol. 2014, 76, 845–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fagan, A.M.; Perrin, R.J. Upcoming Candidate Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers of Alzheimer’s Disease. Biomark. Med. 2012, 6, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buerger, K.; Zinkowski, R.; Teipel, S.J.; Arai, H.; DeBernardis, J.; Kerkman, D.; McCulloch, C.; Padberg, F.; Faltraco, F.; Goernitz, A.; et al. Differentiation of Geriatric Major Depression from Alzheimer’s Disease with CSF Tau Protein Phosphorylated at Threonine 231. Am. J. Psychiatry 2003, 160, 376–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, H.M.; Carrillo, M.C.; Grodstein, F.; Henriksen, K.; Jeromin, A.; Lovestone, S.; Mielke, M.M.; O’Bryant, S.; Sarasa, M.; Sjøgren, M.; et al. Developing Novel Blood-Based Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2014, 10, 109–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease: Current Status and Prospects for the Future. J. Intern. Med. 2018, 284, 643–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Jong, D.; Jansen, R.W.M.M.; Pijnenburg, Y.A.L.; Van Geel, W.J.A.; Borm, G.F.; Kremer, H.P.H.; Verbeek, M.M. CSF Neurofilament Proteins in the Differential Diagnosis of Dementia. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2007, 78, 936–938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cedazo-Minguez, A.; Winblad, B. Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Forms of Dementia: Clinical Needs, Limitations and Future Aspects. Exp. Gerontol. 2010, 45, 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Postuma, R.B.; Berg, D.; Stern, M.; Poewe, W.; Olanow, C.W.; Oertel, W.; Obeso, J.; Marek, K.; Litvan, I.; Lang, A.E.; et al. MDS Clinical Diagnostic Criteria for Parkinson’s Disease. Mov. Disord. 2015, 30, 1591–1601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marques, T.M.; van Rumund, A.; Bruinsma, I.B.; Wessels, H.J.C.T.; Gloerich, J.; Esselink, R.A.J.; Bloem, B.R.; Kuiperij, H.B.; Verbeek, M.M. Cerebrospinal Fluid Galectin-1 Levels Discriminate Patients with Parkinsonism from Controls. Mol. Neurobiol. 2019, 56, 5067–5074. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, X.; Carroni, M.; Nussbaum-Krammer, C.; Mogk, A.; Nillegoda, N.B.; Szlachcic, A.; Guilbride, D.L.; Saibil, H.R.; Mayer, M.P.; Bukau, B. Human Hsp70 Disaggregase Reverses Parkinson’s-Linked α-Synuclein Amyloid Fibrils. Mol. Cell 2015, 59, 781–793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonsen, A.H.; Herukka, S.K.; Andreasen, N.; Baldeiras, I.; Bjerke, M.; Blennow, K.; Engelborghs, S.; Frisoni, G.B.; Gabryelewicz, T.; Galluzzi, S.; et al. Recommendations for CSF AD Biomarkers in the Diagnostic Evaluation of Dementia. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2017, 13, 274–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.; Surova, Y.; Öhrfelt, A.; Zetterberg, H.; Lindqvist, D.; Hansson, O. CSF Biomarkers and Clinical Progression of Parkinson Disease. Neurology 2015, 84, 57–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majbour, N.K.; Vaikath, N.N.; Eusebi, P.; Chiasserini, D.; Ardah, M.; Varghese, S.; Haque, M.E.; Tokuda, T.; Auinger, P.; Calabresi, P.; et al. Longitudinal Changes in CSF Alpha-Synuclein Species Reflect Parkinson’s Disease Progression. Mov. Disord. 2016, 31, 1535–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fairfoul, G.; McGuire, L.I.; Pal, S.; Ironside, J.W.; Neumann, J.; Christie, S.; Joachim, C.; Esiri, M.; Evetts, S.G.; Rolinski, M.; et al. Alpha-Synuclein RT-QuIC in the CSF of Patients with Alpha-Synucleinopathies. Ann. Clin. Transl. Neurol. 2016, 3, 812–818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hall, S.; Öhrfelt, A.; Constantinescu, R.; Andreasson, U.; Surova, Y.; Bostrom, F.; Nilsson, C.; Widner, H.; Decraemer, H.; Nägga, K.; et al. Accuracy of a Panel of 5 Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in the Differential Diagnosis of Patients with Dementia and/or Parkinsonian Disorders. Arch. Neurol. 2012, 69, 1445–1452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Skillbäck, T.; Farahmand, B.Y.; Rosén, C.; Mattsson, N.; Nägga, K.; Kilander, L.; Religa, D.; Wimo, A.; Winblad, B.; Schott, J.M.; et al. Cerebrospinal Fluid Tau and Amyloid-Β1-42 in Patients with Dementia. Brain 2015, 138, 2716–2731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siderowf, A.; Concha-Marambio, L.; Lafontant, D.E.; Farris, C.M.; Ma, Y.; Urenia, P.A.; Nguyen, H.; Alcalay, R.N.; Chahine, L.M.; Foroud, T.; et al. Assessment of Heterogeneity among Participants in the Parkinson’s Progression Markers Initiative Cohort Using α-Synuclein Seed Amplification: A Cross-Sectional Study. Lancet Neurol. 2023, 22, 407–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laurens, B.; Constantinescu, R.; Freeman, R.; Gerhard, A.; Jellinger, K.; Jeromin, A.; Krismer, F.; Mollenhauer, B.; Schlossmacher, M.G.; Shaw, L.M.; et al. Fluid Biomarkers in Multiple System Atrophy: A Review of the MSA Biomarker Initiative. Neurobiol. Dis. 2015, 80, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdalinou, N.K.; Paterson, R.W.; Schott, J.M.; Fox, N.C.; Mummery, C.; Blennow, K.; Bhatia, K.; Morris, H.R.; Giunti, P.; Warner, T.T.; et al. A Panel of Nine Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers May Identify Patients with Atypical Parkinsonian Syndromes. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2015, 86, 1240–1247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schade, S.; Mollenhauer, B. Biomarkers in Biological Fluids for Dementia with Lewy Bodies. Alzheimer’s Res. Ther. 2014, 6, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganesalingam, J.; An, J.; Shaw, C.E.; Shaw, G.; Lacomis, D.; Bowser, R. Combination of Neurofilament Heavy Chain and Complement C3 as CSF Biomarkers for ALS. J. Neurochem. 2011, 117, 528–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blokhuis, A.M.; Groen, E.J.N.; Koppers, M.; Van Den Berg, L.H.; Pasterkamp, R.J. Protein Aggregation in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Acta Neuropathol. 2013, 125, 777–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agah, E.; Saleh, F.; Sanjari Moghaddam, H.; Saghazadeh, A.; Tafakhori, A.; Rezaei, N. CSF and Blood Biomarkers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Protocol for a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Syst. Rev. 2018, 7, 237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Irwin, K.E.; Sheth, U.; Wong, P.C.; Gendron, T.F. Fluid Biomarkers for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Review. Mol. Neurodegener. 2024, 19, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranganathan, S.; Williams, E.; Ganchev, P.; Gopalakrishnan, V.; Lacomis, D.; Urbinelli, L.; Newhall, K.; Cudkowicz, M.E.; Brown, R.H.; Bowser, R. Proteomic Profiling of Cerebrospinal Fluid Identifies Biomarkers for Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. J. Neurochem. 2005, 95, 1461–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhury, K.R.; Das, S.; Bhattacharyya, N.P. Differential Proteomic and Genomic Profiling of Mouse Striatal Cell Model of Huntington’s Disease and Control; Probable Implications to the Disease Biology. J. Proteom. 2016, 132, 155–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vinther-Jensen, T.; Simonsen, A.H.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Hjermind, L.E.; Nielsen, J.E. Ubiquitin: A Potential Cerebrospinal Fluid Progression Marker in Huntington’s Disease. Eur. J. Neurol. 2015, 22, 1378–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clavijo, C.A.; Buenaventura, A.M.P.; Albornoz, G.S.B.; Cabrera, J.J.M.; Reyes, M.C.M.; Gallego, A.C.; González, C.A.H.; Otalvaro, S.O.; Escobar, C.S.M.; Mera, K.J.Q.; et al. Case Report: Three Case Reports of Rapidly Progressive Dementias and Narrative Review. Case Rep. Neurol. 2022, 14, 449–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zanusso, G.; Fiorini, M.; Ferrari, S.; Gajofatto, A.; Cagnin, A.; Galassi, A.; Richelli, S.; Monaco, S. Cerebrospinal Fluid Markers in Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2011, 12, 6281–6292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atarashi, R.; Satoh, K.; Sano, K.; Fuse, T.; Yamaguchi, N.; Ishibashi, D.; Matsubara, T.; Nakagaki, T.; Yamanaka, H.; Shirabe, S.; et al. Ultrasensitive Human Prion Detection in Cerebrospinal Fluid by Real-Time Quaking-Induced Conversion. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jonaitis, E.M.; Jeffers, B.; VandenLangenberg, M.; Ma, Y.; Van Hulle, C.; Langhough, R.; Du, L.; Chin, N.A.; Przybelski, R.J.; Hogan, K.J.; et al. CSF Biomarkers in Longitudinal Alzheimer Disease Cohorts: Pre-Analytic Challenges. Clin. Chem. 2024, 70, 538–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seidu, N.M.; Kern, S.; Sacuiu, S.; Sterner, T.R.; Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H.; Lindberg, O.; Ferreira, D.; Westman, E.; Zettergren, A.; et al. Association of CSF Biomarkers with MRI Brain Changes in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2024, 16, e12556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vrillon, A.; Ashton, N.J.; Karikari, T.K.; Götze, K.; Cognat, E.; Dumurgier, J.; Lilamand, M.; Zetterberg, H.; Blennow, K.; Paquet, C. Comparison of CSF and Plasma NfL and PNfH for Alzheimer’s Disease Diagnosis: A Memory Clinic Study. J. Neurol. 2024, 271, 1297–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.; Zuo, H.; Ma, D.; Song, D.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, O. Cerebrospinal Fluid GFAP Is a Predictive Biomarker for Conversion to Dementia and Alzheimer’s Disease-Associated Biomarkers Alterations among de Novo Parkinson’s Disease Patients: A Prospective Cohort Study. J. Neuroinflamm. 2023, 20, 167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Xiao, S.; Wan, M. Association of CSF Visinin-like Protein 1 Levels with Cerebral Glucose Metabolism among Older Adults. PLoS ONE 2025, 20, e0329386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voytyuk, I.; Mueller, S.A.; Herber, J.; Snellinx, A.; Moechars, D.; van Loo, G.; Lichtenthaler, S.F.; De Strooper, B. BACE2 Distribution in Major Brain Cell Types and Identification of Novel Substrates. Life Sci. Alliance 2018, 1, e20180002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farina, A.; Villagrán-García, M.; Abichou-Klich, A.; Benaiteau, M.; Bernard, E.; Bouhour, F.; Desestret, V.; Joubert, B.; Picard, G.; Pinto, A.L.; et al. Serum Neurofilament Light Chain Correlates With Clinical Severity and Predicts Mortality in Anti-IgLON5 Disease. Neurol. Neuroimmunol. Neuroinflamm. 2025, 12, e200498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Lazzaro, G.; Paolini Paoletti, F.; Bellomo, G.; Schirinzi, T.; Grillo, P.; Giuffrè, G.M.; Petracca, M.; Picca, A.; Mercuri, N.B.; Parnetti, L.; et al. Effect of Aging on Biomarkers and Clinical Profile in Parkinson’s Disease. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bissacco, J.; Di Lazzaro, G.; Bovenzi, R.; Sancesario, G.M.; Conti, M.; Simonetta, C.; Mascioli, D.; Mancini, M.; Buttarazzi, V.; Pierantozzi, M.; et al. CSF Phospho-Tau Levels at Parkinson’s Disease Onset Predict the Risk for Development of Motor Complications. J. Neurol. 2025, 272, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bougea, A.; Colosimo, C.; Falup-Pecurariu, C.; Palermo, G.; Degirmenci, Y. Fluid Biomarkers in Atypical Parkinsonism: Current State and Future Perspectives. J. Neurol. 2025, 132, 921–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonini, C.; Zucchi, E.; Martinelli, I.; Gianferrari, G.; Lunetta, C.; Sorarù, G.; Trojsi, F.; Pepe, R.; Piras, R.; Giacchino, M.; et al. Neurodegenerative and Neuroinflammatory Changes in SOD1-ALS Patients Receiving Tofersen. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 11034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kjældgaard, A.L.; Pilely, K.; Olsen, K.S.; Lauritsen, A.Ø.; Pedersen, S.W.; Svenstrup, K.; Karlsborg, M.; Thagesen, H.; Blaabjerg, M.; Theódórsdóttir, Á.; et al. Complement Profiles in Patients with Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: A Prospective Observational Cohort Study. J. Inflamm. Res. 2021, 14, 1043–1053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bowser, R.; An, J.; Schwartz, K.; Sucholeiki, R.L.; Sucholeiki, I. ALS Patients Exhibit Altered Levels of Total and Active MMP-9 and Several Other Biomarkers in Serum and CSF Compared to Healthy Controls and Other Neurologic Diseases. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 8900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuo, Y.C.; Yang, C.C.; Tsai, L.K. Exploring CSF Biomarkers in Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis: Highlighting the Significance of TDP-43. J. Neurol. Sci. 2025, 472, 123479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Sun, S.; Bai, Z.; Gao, N.; Yu, W.; Sun, X.; Li, W.; Zhao, Y.; Yan, C.; Lin, P.; et al. CSF Aβ, Tau, Axonal, Synaptic, Glial, Neural, and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients With Sporadic Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Neurology 2025, 105, e213914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vardheim, E.G.; Toft, A.; Nielsen, J.E.; Hasselbalch, S.G.; Simonsen, A.H. Cerebrospinal Fluid Ubiquitin as a Biomarker for Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Systematic Review. Neurosci. Appl. 2023, 2, 102438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caron, N.S.; Byrne, L.M.; Lemarié, F.L.; Bone, J.N.; Aly, A.E.E.; Ko, S.; Anderson, C.; Casal, L.L.; Hill, A.M.; Hawellek, D.J.; et al. Elevated Plasma and CSF Neurofilament Light Chain Concentrations Are Stabilized in Response to Mutant Huntingtin Lowering in the Brains of Huntington’s Disease Mice. Transl. Neurodegener. 2024, 13, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenmann, H.; Meiner, Z.; Kahana, E.; Halimi, M.; Lenetsky, E.; Abramsky, O.; Gabizon, R. Detection of 14-3-3 Protein in the CSF of Genetic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Neurology 1997, 49, 593–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buerger, K.; Otto, M.; Teipel, S.J.; Zinkowski, R.; Blennow, K.; DeBernardis, J.; Kerkman, D.; Schröder, J.; Schönknecht, P.; Cepek, L.; et al. Dissociation between CSF Total Tau and Tau Protein Phosphorylated at Threonine 231 in Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Neurobiol. Aging 2006, 27, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermann, P.; Appleby, B.; Brandel, J.P.; Caughey, B.; Collins, S.; Geschwind, M.D.; Green, A.; Haïk, S.; Kovacs, G.G.; Ladogana, A.; et al. Biomarkers and Diagnostic Guidelines for Sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob Disease. Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, 235–246, Correction in Lancet Neurol. 2021, 20, e3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardridge, W.M. The Blood-Brain Barrier: Bottleneck in Brain Drug Development. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Meer, G.; Gumbiner, B.; Simons, K. The Tight Junction Does Not Allow Lipid Molecules to Diffuse from One Epithelial Cell to the Next. Nature 1986, 322, 639–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pardridge, W.M. Blood-Brain Barrier Endogenous Transporters as Therapeutic Targets: A New Model for Small Molecule CNS Drug Discovery. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets 2015, 19, 1059–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghose, A.K.; Viswanadhan, V.N.; Wendoloski, J.J. A Knowledge-Based Approach in Designing Combinatorial or Medicinal Chemistry Libraries for Drug Discovery. 1. A Qualitative and Quantitative Characterization of Known Drug Databases. J. Comb. Chem. 1999, 1, 55–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lipinski, C.A. Drug-like Properties and the Causes of Poor Solubility and Poor Permeability. J. Pharmacol. Toxicol. Methods 2000, 44, 235–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajay; Bemis, G.W.; Murcko, M.A. Designing Libraries with CNS Activity. J. Med. Chem. 1999, 42, 4942–4951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsuji, A. Small Molecular Drug Transfer across the Blood-Brain Barrier via Carrier-Mediated Transport Systems. NeuroRx 2005, 2, 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sugano, K.; Kansy, M.; Artursson, P.; Avdeef, A.; Bendels, S.; Di, L.; Ecker, G.F.; Faller, B.; Fischer, H.; Gerebtzoff, G.; et al. Coexistence of Passive and Carrier-Mediated Processes in Drug Transport. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2010, 9, 597–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haqqani, A.S.; Bélanger, K.; Stanimirovic, D.B. Receptor-Mediated Transcytosis for Brain Delivery of Therapeutics: Receptor Classes and Criteria. Front. Drug Deliv. 2024, 4, 1360302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, F.C.; Taskar, K.; Rudraraju, V.; Goda, S.; Thorsheim, H.R.; Gaasch, J.A.; Mittapalli, R.K.; Palmieri, D.; Steeg, P.S.; Lockman, P.R.; et al. Uptake of ANG1005, a Novel Paclitaxel Derivative, through the Blood-Brain Barrier into Brain and Experimental Brain Metastases of Breast Cancer. Pharm. Res. 2009, 26, 2486–2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thom, G.; Tian, M.M.; Hatcher, J.P.; Rodrigo, N.; Burrell, M.; Gurrell, I.; Vitalis, T.Z.; Abraham, T.; Jefferies, W.A.; Webster, C.I.; et al. A Peptide Derived from Melanotransferrin Delivers a Protein-Based Interleukin 1 Receptor Antagonist across the BBB and Ameliorates Neuropathic Pain in a Preclinical Model. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2019, 39, 2074–2088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, M.S.; Shin, M.; Ottoy, J.; Aliaga, A.A.; Mathotaarachchi, S.; Quispialaya, K.; Pascoal, T.A.; Collins, D.L.; Chakravarty, M.M.; Mathieu, A.; et al. Preclinical in Vivo Longitudinal Assessment of KG207-M as a Disease-Modifying Alzheimer’s Disease Therapeutic. J. Cereb. Blood Flow. Metab. 2022, 42, 788–801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhuria, S.V.; Hanson, L.R.; Frey, W.H. Intranasal Delivery to the Central Nervous System: Mechanisms and Experimental Considerations. J. Pharm. Sci. 2010, 99, 1654–1673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Inoue, D.; Furubayashi, T.; Tanaka, A.; Sakane, T.; Sugano, K. Effect of Cerebrospinal Fluid Circulation on Nose-to-Brain Direct Delivery and Distribution of Caffeine in Rats. Mol. Pharm. 2020, 17, 4067–4076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tripathi, D.; Pandey, P.; Sharma, S.; Rai, A.K.; Prabhu, M.B.H. Advances in Nanomaterials for Precision Drug Delivery: Insights into Pharmacokinetics and Toxicity. Bioimpacts 2024, 15, 30573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, R.; Grumezescu, A. Metal Based Frameworks for Drug Delivery Systems. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 2015, 15, 1532–1542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harush-Frenkel, O.; Rozentur, E.; Benita, S.; Altschuler, Y. Surface Charge of Nanoparticles Determines Their Endocytic and Transcytotic Pathway in Polarized MDCK Cells. Biomacromolecules 2008, 9, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.W.; Monteiro-Riviere, N.A. Mechanisms of Quantum Dot Nanoparticle Cellular Uptake. Toxicol. Sci. 2009, 110, 138–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arellano, A.; Palma-Florez, S.; Cabrera, P.; Cortés-Adasme, E.; Bolaños, K.; Celis, F.; Pérez, M.; Crespo, A.; Matus, M.; Araya, E.; et al. Attenuation of Blood-Brain Barrier Dysfunction by Functionalized Gold Nanoparticles Against Amyloid-Β Peptide in an Alzheimer’s Disease-on-A-Chip Model. Mater. Today Fam. J. 2025, 35, 102453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lilius, T.O.; Mortensen, K.N.; Deville, C.; Lohela, T.J.; Stæger, F.F.; Sigurdsson, B.; Fiordaliso, E.M.; Rosenholm, M.; Kamphuis, C.; Beekman, F.J.; et al. Glymphatic-Assisted Perivascular Brain Delivery of Intrathecal Small Gold Nanoparticles. J. Control. Release 2023, 355, 135–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, C.; Liu, H.; Zhang, M.; Deng, H.; Lei, C.; Shen, L.; Jiao, B.; Tu, Q.; Jin, Y.; Xiang, L.; et al. Light-Up Nonthiolated Aptasensor for Low-Mass, Soluble Amyloid-Β40 Oligomers at High Salt Concentrations. Anal. Chem. 2018, 90, 1710–1717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mu, H.; Holm, R. Solid Lipid Nanocarriers in Drug Delivery: Characterization and Design. Expert Opin. Drug Deliv. 2018, 15, 771–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barriga, H.M.G.; Holme, M.N.; Stevens, M.M. Cubosomes: The Next Generation of Smart Lipid Nanoparticles? Angew. Chem.-Int. Ed. 2019, 58, 2958–2978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hald Albertsen, C.; Kulkarni, J.A.; Witzigmann, D.; Lind, M.; Petersson, K.; Simonsen, J.B. The Role of Lipid Components in Lipid Nanoparticles for Vaccines and Gene Therapy. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2022, 188, 114416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garti, N.; Libster, D.; Aserin, A. Lipid Polymorphism in Lyotropic Liquid Crystals for Triggered Release of Bioactives. Food Funct. 2012, 3, 700–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Fong, C.; Tran, N.; Drummond, C.J. Non-Lamellar Lyotropic Liquid Crystalline Lipid Nanoparticles for the Next Generation of Nanomedicine. ACS Nano 2019, 13, 6178–6206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajesh, S.; Zhai, J.; Drummond, C.J.; Tran, N. Synthetic Ionizable Aminolipids Induce a PH Dependent Inverse Hexagonal to Bicontinuous Cubic Lyotropic Liquid Crystalline Phase Transition in Monoolein Nanoparticles. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2021, 589, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yaghmur, A.; Glatter, O. Characterization and Potential Applications of Nanostructured Aqueous Dispersions. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2009, 147–148, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwarz, C.; Mehnert, W.; Lucks, J.S.; Müller, R.H. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for Controlled Drug Delivery. I. Production, Characterization and Sterilization. J. Control. Release 1994, 30, 83–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zur Mühlen, A.; Schwarz, C.; Mehnert, W. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles (SLN) for Controlled Drug Delivery—Drug Release and Release Mechanism. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 1998, 45, 149–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenning, V.; Schäfer-Korting, M.; Gohla, S. Vitamin A-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Topical Use: Drug Release Properties. J. Control. Release 2000, 66, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almuhayawi, M.S.; Ramadan, W.S.; Harakeh, S.; Al Jaouni, S.K.; Bharali, D.J.; Mousa, S.A.; Almuhayawi, S.M. The Potential Role of Pomegranate and Its Nano-Formulations on Cerebral Neurons in Aluminum Chloride Induced Alzheimer Rat Model. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2020, 27, 1710–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacomeli, R.; Izoton, J.C.; dos Santos, R.B.; Boeira, S.P.; Jesse, C.R.; Haas, S.E. Neuroprotective Effects of Curcumin Lipid-Core Nanocapsules in a Model Alzheimer’s Disease Induced by β-Amyloid 1-42 Peptide in Aged Female Mice. Brain Res. 2019, 1721, 146325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dara, T.; Vatanara, A.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Khani, S.; Vakilinezhad, M.A.; Vakhshiteh, F.; Nabi Meybodi, M.; Sadegh Malvajerd, S.; Hassani, S.; Mosaddegh, M.H. Improvement of Memory Deficits in the Rat Model of Alzheimer’s Disease by Erythropoietin-Loaded Solid Lipid Nanoparticles. Neurobiol. Learn. Mem. 2019, 166, 107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yazihan, N.; Uzuner, K.; Salman, B.; Vural, M.; Koken, T.; Arslantas, A. Erythropoietin Improves Oxidative Stress Following Spinal Cord Trauma in Rats. Injury 2008, 39, 1408–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, X.; Gong, X.; Pan, L.; Lu, L. Erythropoietin Relieves Neuronal Apoptosis in Epilepsy Rats via TGF-β/Smad Signaling Pathway. Cell Mol. Biol. 2023, 69, 239–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Song, J.; Song, Q.; Li, L.; Tian, X.; Wang, L. Recombinant Human Erythropoietin Protects against Immature Brain Damage Induced by Hypoxic/Ischemia Insult. Neuroreport 2023, 34, 801–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ralvenius, W.T.; Andresen, J.L.; Huston, M.M.; Penney, J.; Bonner, J.M.; Fenton, O.S.; Langer, R.; Tsai, L.H. Nanoparticle-Mediated Delivery of Anti-PU.1 SiRNA via Localized Intracisternal Administration Reduces Neuroinflammation. Adv. Mater. 2024, 36, 2309225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Straten, D.; Sork, H.; van de Schepop, L.; Frunt, R.; Ezzat, K.; Schiffelers, R.M. Biofluid Specific Protein Coronas Affect Lipid Nanoparticle Behavior In Vitro. J. Control. Release 2024, 373, 481–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, Y.K.; Kim, S.W. Recent Advances in Polymeric Drug Delivery Systems. Biomater. Res. 2020, 24, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tong, X.; Pan, W.; Su, T.; Zhang, M.; Dong, W.; Qi, X. Recent Advances in Natural Polymer-Based Drug Delivery Systems. React. Funct. Polym. 2020, 148, 104501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elibol, B.; Beker, M.; Terzioglu-Usak, S.; Dalli, T.; Kilic, U. Thymoquinone Administration Ameliorates Alzheimer’s Disease-like Phenotype by Promoting Cell Survival in the Hippocampus of Amyloid Beta1–42 Infused Rat Model. Phytomedicine 2020, 79, 153324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yusuf, M.; Khan, M.; Alrobaian, M.M.; Alghamdi, S.A.; Warsi, M.H.; Sultana, S.; Khan, R.A. Brain Targeted Polysorbate-80 Coated PLGA Thymoquinone Nanoparticles for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease, with Biomechanistic Insights. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2021, 61, 102214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathew, A.; Fukuda, T.; Nagaoka, Y.; Hasumura, T.; Morimoto, H.; Yoshida, Y.; Maekawa, T.; Venugopal, K.; Kumar, D.S. Curcumin Loaded-PLGA Nanoparticles Conjugated with Tet-1 Peptide for Potential Use in Alzheimer’s Disease. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e32616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.K.; Agarwal, S.; Seth, B.; Yadav, A.; Nair, S.; Bhatnagar, P.; Karmakar, M.; Kumari, M.; Chauhan, L.K.S.; Patel, D.K.; et al. Curcumin-Loaded Nanoparticles Potently Induce Adult Neurogenesis and Reverse Cognitive Deficits in Alzheimer’s Disease Model via Canonical Wnt/β-Catenin Pathway. ACS Nano 2014, 8, 76–103, Correction in ACS Nano 2019, 13, 7355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, X.; Zhang, X.; Li, R.; Yang, X.; Fu, P.; Feng, R.; Sun, X.; Wang, Z.; Yu, J.; Cao, X.; et al. Platelet Membrane-Coated Curcumin-PLGA Nanoparticles Promote Astrocyte-Neuron Transdifferentiation for Intracerebral Hemorrhage Treatment. Small 2024, 20, 2311128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graverini, G.; Piazzini, V.; Landucci, E.; Pantano, D.; Nardiello, P.; Casamenti, F.; Pellegrini-Giampietro, D.E.; Bilia, A.R.; Bergonzi, M.C. Solid Lipid Nanoparticles for Delivery of Andrographolide across the Blood-Brain Barrier: In Vitro and in Vivo Evaluation. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2018, 161, 302–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guccione, C.; Oufir, M.; Piazzini, V.; Eigenmann, D.E.; Jähne, E.A.; Zabela, V.; Faleschini, M.T.; Bergonzi, M.C.; Smiesko, M.; Hamburger, M.; et al. Andrographolide-Loaded Nanoparticles for Brain Delivery: Formulation, Characterisation and In Vitro Permeability Using HCMEC/D3 Cell Line. Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 119, 253–263, Erratum in Eur. J. Pharm. Biopharm. 2017, 120, 146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, D.; Li, N.; Zhang, W.; Zhao, Z.; Mou, Z.; Huang, D.; Liu, J.; Wang, W. Design of PLGA-Functionalized Quercetin Nanoparticles for Potential Use in Alzheimer’s Disease. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2016, 148, 116–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sathya, S.; Shanmuganathan, B.; Saranya, S.; Vaidevi, S.; Ruckmani, K.; Pandima Devi, K. Phytol-Loaded PLGA Nanoparticle as a Modulator of Alzheimer’s Toxic Aβ Peptide Aggregation and Fibrillation Associated with Impaired Neuronal Cell Function. Artif. Cells Nanomed. Biotechnol. 2018, 46, 1719–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández, L.; Santo, M.; Silber, J.J.; Cerecetto, H. Solubilization and Release Properties of Dendrimers. Evaluation as Prospective Drug Delivery Systems. Supramol. Chem. 2006, 18, 633–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.K.; Chaudhary, S.; Rani, S.; Sharma, A.K.; Gupta, L.; Gupta, U. Dendrimer-Drug Conjugates in Drug Delivery and Targeting. Pharm. Nanotechnol. 2016, 3, 239–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCarthy, J.M.; Franke, M.; Resenberger, U.K.; Waldron, S.; Simpson, J.C.; Tatzelt, J.; Appelhans, D.; Rogers, M.S. Anti-Prion Drug MPPIg5 Inhibits PrPC Conversion to PrPSc. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e55282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, G.; Long, H.; Zhou, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, J.; Han, J.; Yang, X.; Yu, Y.; Chen, F.; Shi, S. Blood-Brain Barrier Permeable Nanoparticles for Alzheimer’s Disease Treatment by Selective Mitophagy of Microglia. Biomaterials 2022, 288, 121690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Evren, G.; Er, E.; Yalcinkaya, E.E.; Horzum, N.; Odaci, D. Electrospun Nanofibers Including Organic/Inorganic Nanohybrids: Polystyrene- and Clay-Based Architectures in Immunosensor Preparation for Serum Amyloid A. Biosensors 2023, 13, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milowska, K.; Szwed, A.; Mutrynowska, M.; Gomez-Ramirez, R.; De La Mata, F.J.; Gabryelak, T.; Bryszewska, M. Carbosilane Dendrimers Inhibit α-Synuclein Fibrillation and Prevent Cells from Rotenone-Induced Damage. Int. J. Pharm. 2015, 484, 268–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, Y.; Xu, T. Design of Biocompatible Dendrimers for Cancer Diagnosis and Therapy: Current Status and Future Perspectives. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 2673–2703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Awad, R.; Avital, A.; Sosnik, A. Polymeric Nanocarriers for Nose-to-Brain Drug Delivery in Neurodegenerative Diseases and Neurodevelopmental Disorders. Acta Pharm. Sin. B 2023, 13, 1866–1886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, P.V.; de Queiroz, A.A.A. Long Term Multiple Sclerosis Drug Delivery Using Dendritic Polyglycerol Flower-like Microspheres. J. Biomater. Sci. Polym. Ed. 2020, 31, 188–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doran, S.J.; Sawyer, R.P. Risk Factors in Developing Amyloid Related Imaging Abnormalities (ARIA) and Clinical Implications. Front. Neurosci. 2024, 18, 1326784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J. IgG Fusion Proteins for Brain Delivery of Biologics via Blood–Brain Barrier Receptor-Mediated Transport. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehlin, D.; Roshanbin, S.; Zachrisson, O.; Ingelsson, M.; Syvänen, S. A Brain-Penetrant Bispecific Antibody Lowers Oligomeric Alpha-Synuclein and Activates Microglia in a Mouse Model of Alpha-Synuclein Pathology. Neurotherapeutics 2024, 22, e00510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giugliani, R.; Giugliani, L.; De Oliveira Poswar, F.; Donis, K.C.; Corte, A.D.; Schmidt, M.; Boado, R.J.; Nestrasil, I.; Nguyen, C.; Chen, S.; et al. Neurocognitive and Somatic Stabilization in Pediatric Patients with Severe Mucopolysaccharidosis Type I after 52 Weeks of Intravenous Brain-Penetrating Insulin Receptor Antibody-Iduronidase Fusion Protein (Valanafusp Alpha): An Open Label Phase 1-2 Trial. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2018, 13, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boado, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, C.F.; Pardridge, W.M. Fusion Antibody for Alzheimer’s Disease with Bidirectional Transport Across the Blood-Brain Barrier and Abeta Fibril Disaggregation. Bioconjug Chem. 2007, 18, 447–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peppel, K.; Crawford, D.; Beutler, B. A Tumor Necrosis Factor (TNF) Receptor-IgG Heavy Chain Chimeric Protein as a Bivalent Antagonist of TNF Activity. J. Exp. Med. 1991, 174, 1483–1489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nawashiro, H.; Martin, D.; Hallenbeck, J.M. Neuroprotective Effects of TNF Binding Protein in Focal Cerebral Ischemia. Brain Res. 1997, 778, 265–271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knoblach, S.M.; Fan, L.; Faden, A.I. Early Neuronal Expression of Tumor Necrosis Factor-α after Experimental Brain Injury Contributes to Neurological Impairment. J. Neuroimmunol. 1999, 95, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchand, F.; Tsantoulas, C.; Singh, D.; Grist, J.; Clark, A.K.; Bradbury, E.J.; McMahon, S.B. Effects of Etanercept and Minocycline in a Rat Model of Spinal Cord Injury. Eur. J. Pain 2009, 13, 673–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tweedie, D.; Sambamurti, K.; Greig, N. TNF-α Inhibition as a Treatment Strategy for Neurodegenerative Disorders: New Drug Candidates and Targets. Curr. Alzheimer Res. 2007, 4, 378–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Himmerich, H.; Fulda, S.; Linseisen, J.; Seiler, H.; Wolfram, G.; Himmerich, S.; Gedrich, K.; Kloiber, S.; Lucae, S.; Ising, M.; et al. Depression, Comorbidities and the TNF-α System. Eur. Psychiatry 2008, 23, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortí-Casañ, N.; Boerema, A.S.; Köpke, K.; Ebskamp, A.; Keijser, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, T.; Dolga, A.M.; Broersen, K.; Fischer, R.; et al. The TNFR1 Antagonist Atrosimab Reduces Neuronal Loss, Glial Activation and Memory Deficits in an Acute Mouse Model of Neurodegeneration. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 10622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boado, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Xia, C.F.; Wang, Y.; Pardridge, W.M. Genetic Engineering of a Lysosomal Enzyme Fusion Protein for Targeted Delivery across the Human Blood-Brain Barrier. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008, 99, 475–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.Z.; Boado, R.J.; Hui, E.K.W.; Zhou, Q.H.; Pardridge, W.M. Expression in CHO Cells and Pharmacokinetics and Brain Uptake in the Rhesus Monkey of an IgG-Iduronate-2-Sulfatase Fusion Protein. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2011, 108, 1954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, C.I.; Caram-Salas, N.; Haqqani, A.S.; Thom, G.; Brown, L.; Rennie, K.; Yogi, A.; Costain, W.; Brunette, E.; Stanimirovic, D.B. Brain Penetration, Target Engagement, and Disposition of the Blood-Brain Barrier-Crossing Bispecific Antibody Antagonist of Metabotropic Glutamate Receptor Type 1. FASEB J. 2016, 30, 1927–1940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J.; Hui, E.K.W.; Lu, J.Z.; Zhou, Q.H.; Pardridge, W.M. Selective Targeting of a TNFR Decoy Receptor Pharmaceutical to the Primate Brain as a Receptor-Specific IgG Fusion Protein. J. Biotechnol. 2010, 146, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J.; Hui, E.K.W.; Zhiqiang Lu, J.; Pardridge, W.M. Drug Targeting of Erythropoietin across the Primate Blood-Brain Barrier with an IgG Molecular Trojan Horse. J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 2010, 333, 961–969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Pardridge, W.M. GDNF Fusion Protein for Targeted-Drug Delivery across the Human Blood-Brain Barrier. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2008, 100, 387–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boado, R.J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Pardridge, W.M. Genetic Engineering, Expression, and Activity of a Fusion Protein of a Human Neurotrophin and a Molecular Trojan Horse for Delivery across the Human Blood-Brain Barrier. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 97, 1376–1386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pornnoppadol, G.; Bond, L.G.; Lucas, M.J.; Zupancic, J.M.; Kuo, Y.H.; Zhang, B.; Greineder, C.F.; Tessier, P.M. Bispecific Antibody Shuttles Targeting CD98hc Mediate Efficient and Long-Lived Brain Delivery of IgGs. Cell Chem. Biol. 2023, 31, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Gonzalez, M. Intrathecal Immunoselective Nanopheresis for Alzheimer’s Disease: What and How? Why and When? Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 10632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Teleanu, R.I.; Preda, M.D.; Niculescu, A.G.; Vladâcenco, O.; Radu, C.I.; Grumezescu, A.M.; Teleanu, D.M. Current Strategies to Enhance Delivery of Drugs across the Blood–Brain Barrier. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delhaas, E.M.; Huygen, F.J.P.M. Complications Associated with Intrathecal Drug Delivery Systems. BJA Educ. 2020, 20, 51–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martínez-Morillo, E.; Childs, C.; García, B.P.; Álvarez Menéndez, F.V.; Romaschin, A.D.; Cervellin, G.; Lippi, G.; Diamandis, E.P. Neurofilament Medium Polypeptide (NFM) Protein Concentration Is Increased in CSF and Serum Samples from Patients with Brain Injury. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2015, 53, 1575–1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manuel, M.G.; Tamba, B.I.; Leclere, M.; Mabrouk, M.; Schreiner, T.G.; Ciobanu, R.; Cristina, T.Z. Intrathecal Pseudodelivery of Drugs in the Therapy of Neurodegenerative Diseases: Rationale, Basis and Potential Applications. Pharmaceutics 2023, 15, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hilal, N.; Al-Zoubi, H.; Darwish, N.A.; Mohammad, A.W.; Abu Arabi, M. A Comprehensive Review of Nanofiltration Membranes:Treatment, Pretreatment, Modelling, and Atomic Force Microscopy. Desalination 2004, 170, 281–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.K.; Alam, J.; Alhoshan, M. Recent Advancements in Polyphenylsulfone Membrane Modification Methods for Separation Applications. Membranes 2022, 12, 247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lalia, B.S.; Kochkodan, V.; Hashaikeh, R.; Hilal, N. A Review on Membrane Fabrication: Structure, Properties and Performance Relationship. Desalination 2013, 326, 77–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ban, G.; Hou, Y.; Shen, Z.; Jia, J.; Chai, L.; Ma, C. Potential Biomedical Limitations of Graphene Nanomaterials. Int. J. Nanomed. 2023, 18, 1695–1708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Osama, L.; ElShebiney, S.; Beherei, H.H.; Elzayat, E.M.; Mabrouk, M. Modulation of Experimental Alzheimer’s Disease in Rats through Donepezil-Loaded CSF Implant. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 42017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cicchetti, A.; Berrino, A.; Casini, M.; Codella, P.; Facco, G.; Fiore, A.; Marano, G.; Marchetti, M.; Midolo, E.; Minacori, R.; et al. Health Technology Assessment of Pathogen Reduction Technologies Applied to Plasma for Clinical Use. Blood Transfus. 2016, 14, 287–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coto-Vilcapoma, M.A.; Castilla-Silgado, J.; Fernández-García, B.; Pinto-Hernández, P.; Cipriani, R.; Capetillo-Zarate, E.; Menéndez-González, M.; Álvarez-Vega, M.; Tomás-Zapico, C. New, Fully Implantable Device for Selective Clearance of CSF-Target Molecules: Proof of Concept in a Murine Model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peydayesh, M. Nanofiltration Membranes: Recent Advances and Environmental Applications. Membranes 2022, 12, 518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, M.M. Implantable Systems for Continuous Liquorpheresis and CSF Replacement. Cureus 2017, 9, e1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menéndez González, M. Mechanical Filtration of the Cerebrospinal Fluid: Procedures, Systems, and Applications. Expert Rev. Med. Devices 2023, 20, 199–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hülser, P.J.; Wiethölter, H.; Wollinsky, K.H. Liquorpheresis Eliminates Blocking Factors from Cerebrospinal Fluid in Polyradiculoneuritis (Guillain-Barré Syndrome). Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 1991, 241, 69–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Proctor, M.R.; Black, P.M.; Vogel, T.W.; Bruce, J.N. Local Delivery Methods into the CNS. In Minimally Invasive Neurosurgery; Humana Press: Totowa, NJ, USA, 2005; pp. 297–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimenez, F.; Krauze, M.T.; Valles, F.; Hadaczek, P.; Bringas, J.; Sharma, N.; Forsayeth, J.; Bankiewicz, K.S. Image-Guided Convection-Enhanced Delivery of GDNF Protein into Monkey Putamen. Neuroimage 2011, 54, S189–S195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nicholson, C. Diffusion and Related Transportmechanisms in Brain Tissue. Rep. Progress Phys. 2001, 64, 815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bander, E.D.; Tizi, K.; Wembacher-Schroeder, E.; Thomson, R.; Donzelli, M.; Vasconcellos, E.; Souweidane, M.M. Deformational Changes after Convection-Enhanced Delivery in the Pediatric Brainstem. Neurosurg. Focus. 2020, 48, E3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellat, V.; Alcaina, Y.; Tung, C.H.; Ting, R.; Michel, A.O.; Souweidane, M.; Law, B. A Combined Approach of Convection-Enhanced Delivery of Peptide Nanofiber Reservoir to Prolong Local DM1 Retention for Diffuse Intrinsic Pontine Glioma Treatment. Neuro-Oncology 2020, 22, 1495–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikeladze, M.A.; Dutysheva, E.A.; Kartsev, V.G.; Margulis, B.A.; Guzhova, I.V.; Lazarev, V.F. Disruption of the Complex between GAPDH and Hsp70 Sensitizes C6 Glioblastoma Cells to Hypoxic Stress. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 1520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Disease | Marker | Characteristics of Changes in CSF Content (Compared to Healthy Patients) and References |

|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer’s disease | Aβ42 | Reduction in content, one of the main markers |

| Tau (total and phosphorylated) | Increased content, one of the main markers [125,126] | |

| NfL и NfH; GFAP; BACE1; APP; VSNL1 | Increased content, are candidates for the role of additional markers [127,128,129,130] | |

| Parkinson’s disease | α-synuclein | Decreased levels, a leading candidate for biomarker [131,132] |

| NfL | There are no changes, but it is reduced in comparison with atypical parkinsonian syndromes [132] | |

| Aβ42 | Reduction in content [132] | |

| Tau | Increase in content [133] | |

| Atypical parkinsonian syndromes | NfL and NfH | The nature of the changes depends on the specific disease and are considered the most promising markers [131,132] |

| Aβ40 and Aβ42, tau, α-synuclein, tau/α-synuclein ratio | The nature of the changes depends on the specific disease [134] | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | NfL and NfH | Increase in content [135] |

| Complement 3 | Increase in content [136] | |

| SOD1, metalloproteinases 2 and 9 (MMP 2 and 9) | Data on the nature of the changes is contradictory [137] | |

| TDP-43 | Increase in content [138] | |

| A combination of transthyretin, cystatin C, and the carboxyl-terminal fragment of neuroendocrine protein 7B2 | Increase in content [139] | |

| Huntington’s disease | Huntingtin (mutant form) | Appearance in CSF (absent in healthy people) [120] |

| Ubiquitin | Increase in content [140] | |

| Tau, NfL | Increase in content [141] | |

| Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease | Protein 14-3-3 | Increased content, the main biomarker of CSF [142] |

| Tau, ratio of total and phosphorylated tau | An increase in the content is considered as an additional marker of the disease [143] | |

| PrPSc | Appearance in CSF (absent in healthy people) [144] |

| Fused Protein IgG 1 | Therapeutic Domain | Disease of the Nervous System | Therapeutic Effect | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RmAb38E2-scFv8D3 | Antibody to the oligomeric form of α-synuclein | PD (synucleinopathy) | Reduction of α-synuclein oligomer accumulation in a mouse model of synucleinopathy | [206] |

| HIRMAb-IDUA (valanafusp alpha) | Iduronidase (IDUA) | Hurler syndrome (MPS I) | Decreased glucosaminoglycan production in fibroblasts from patients with MSP I | [216] |

| HIRMAb-IDS | Iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS) | Hunter syndrome (MPS II) | Reduction of polysaccharide accumulation | [217] |

| BBB-mGluR1 | Antagonist of metabotropic glutamate receptor type 1 | Chronic pain of inflammatory origin | Suppression of thermal hyperalgesia in a rat model of chronic pain | [218] |

| Bispecific antibody HIRMAb-Aβ | Anti-Aβ single-chain Fv antibody (scFv) | AD * | Reduction of Aβ deposits in a transgenic mouse model | [208] |

| HIRMAb-TNFR | Tumor necrosis factor decoy receptor (TNFR) | PD, ALS, AD, stroke * | Effective penetration of the BBB and clearance from the brain in rhesus macaquesReduction of TNFα-mediated cell death in an in vitro model of actinomycin D action | [219] |

| HIRMAb-EPO | Erythropoietin (EPO) | PD, AD, Friedreich’s ataxia * | Reduction of ischemic lesion volume in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model | [220] |

| HIRMAb-GDNF | Glial cell-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) | PD, stroke, drug/EtOH addiction * | Reduction of ischemic lesion volume in the rat middle cerebral artery occlusion model | [221] |

| HIRMAb-BDNF | Brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) | Stroke, recovery (regenerative processes) of the nervous system * | Crossing the BBB was confirmed in isolated capillaries.Reduction of cell death in an in vitro hypoxia model. | [222] |

| CD98hc-TrkB | Neurotrophin receptor antibodies (TrkB) | AD, PD, Huntington’s disease | Blockade of TrkB-mediated signaling in vivo | [223] |

| Delivery Method | Mechanism | Route of Administration | Estimated Concentration/Efficiency | Risks | Clinical Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nanoparticles | Lipophilic diffusion, adsorptive-mediated transcytosis of NPs with therapeutic cargo | Intravenous, intranasal, oral | 0.001% to 0.01% of the injected dose | Hepatotoxicity, chronic neuroinflammation, BBB disruption, complement activation-related pseudoallergy, burst drug release and local neurotoxicity | Pre-clinical |

| Engineered antibodies | Target inactivation with specific antibodies passing through BBB with the help of molecular “Trojan horse” targeting an endogenous BBB receptor | Intravenous, intranasal | 0.5% to 3% of plasma concentration, 5–10 times more compared to passive immunization | Immunogenicity, unfavorable pharmacokinetics, cytokine release syndrome, anemia | Phase I/II |

| Nanopheresis | Target inactivation through continuous CSF filtration through nanopore membrane filled with drug e.g., antibody | Invasive through intrathecal capsule | Reduction of 30–50% of therapeutic target | Intracranial hemorrhage, inflammatory response, loss of essential biomolecules | Pre-clinical |

| Liquorpheresis | CSF filtering—protein depletion total protein | Invasive: intrathecal CSF Filtration | 20–40% of protein decrease in CSF | Loss of essential biomolecules, protein aggregation, hydrodinamic stress, intracranial hypotension, | Phase I |

| Convection-enchased delivery | Direct delivery into parenchyma with a drain | Invasive through cerebral catheter | High concentration of drug near the catheter but decreases logarithmically within millimeters of the catheter tip | Backflow (reflux), local neurotoxicity | Phase I/II |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dutysheva, E.A.; Zaerko, A.V.; Valko, M.A.; Antipina, E.O.; Zimatkin, S.M.; Margulis, B.A.; Guzhova, I.V.; Lazarev, V.F. Modulating Cerebrospinal Fluid Composition in Neurodegenerative Processes: Modern Drug Delivery and Clearance Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 11541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311541

Dutysheva EA, Zaerko AV, Valko MA, Antipina EO, Zimatkin SM, Margulis BA, Guzhova IV, Lazarev VF. Modulating Cerebrospinal Fluid Composition in Neurodegenerative Processes: Modern Drug Delivery and Clearance Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2025; 26(23):11541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311541

Chicago/Turabian StyleDutysheva, Elizaveta A., Anastasiya V. Zaerko, Mikita A. Valko, Ekaterina O. Antipina, Sergey M. Zimatkin, Boris A. Margulis, Irina V. Guzhova, and Vladimir F. Lazarev. 2025. "Modulating Cerebrospinal Fluid Composition in Neurodegenerative Processes: Modern Drug Delivery and Clearance Strategies" International Journal of Molecular Sciences 26, no. 23: 11541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311541

APA StyleDutysheva, E. A., Zaerko, A. V., Valko, M. A., Antipina, E. O., Zimatkin, S. M., Margulis, B. A., Guzhova, I. V., & Lazarev, V. F. (2025). Modulating Cerebrospinal Fluid Composition in Neurodegenerative Processes: Modern Drug Delivery and Clearance Strategies. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 26(23), 11541. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms262311541