Abstract

Efficient berth allocation remains a critical challenge in bulk port operations due to the stochastic nature of vessel arrivals and the complex interaction among loading resources. This study proposes an integrated optimisation–simulation framework to minimise total demurrage costs under uncertainty. The mathematical model was formulated as a mixed-integer linear program (MILP) to determine the optimal assignment and sequencing of vessels to berths and shiploaders, subject to time-window and capacity constraints. The MILP was solved using a Simulated Annealing (SA) metaheuristic to improve computational efficiency for large-scale instances. Subsequently, the optimised berth plans were evaluated in FlexSim, a discrete-event simulation environment, to assess the operational variability arising from stochastic factors, including vessel arrival times, service durations, and loader availability. System performance was measured through vessel waiting time, berth utilisation rate, and demurrage cost variability across multiple replications. Results indicate that the proposed SA–FlexSim framework reduced average demurrage costs by 28.7% compared to the deterministic MILP and by 21.3% relative to standalone SA, confirming its effectiveness and robustness under uncertain operating conditions. The hybrid methodology provides a practical decision-support tool for terminal operators seeking to enhance scheduling reliability and cost efficiency in bulk port environments.

1. Introduction

The Berth Allocation Problem (BAP) is a significant and computationally demanding scheduling challenge in marine logistics. The process entails allocating incoming vessels to vacant berths along a quay within a specified planning timeframe, aiming to reduce costs and optimise the utilisation of port resources. Effective berth allocation impacts both the total turnaround time of vessels and the operational efficiency and economic competitiveness of port terminals [1,2].

Historically, the majority of research on the BAP has been on container ports, where operational conditions—characterised by standardised cargo units, many quay cranes, and organised service patterns—facilitate deterministic or semi-deterministic modelling [3,4]. Conversely, bulk ports exhibit unique operational characteristics: vessel dimensions and loading rates are very variable, environmental and equipment limitations are markedly unpredictable, and any departures from agreed laytime promptly incur demurrage charges. These expenses represent direct financial repercussions for prolonged vessel stays, rendering the scheduling dilemma in bulk terminals an intrinsically uncertain and high-stakes optimisation challenge [5,6,7]. Consequently, traditional mathematical models and deterministic heuristic algorithms frequently neglect the randomness and interdependencies that characterise bulk port operations.

In the past two decades, various analytical and heuristic methods have been proposed to address distinct versions of the BAP. Initial research utilised mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) in small-scale deterministic contexts, concentrating on the reduction in vessel waiting times or overall service duration [8]. Subsequently, metaheuristic algorithms such as Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), and Particle Swarm Optimisation (PSO) were developed to tackle bigger, non-linear formulations [9,10]. Concurrently, discrete-event simulation has become significant for modelling intricate port systems characterised by stochastic arrival patterns, resource limitations, and fluctuating berth occupancy [11,12]. Nevertheless, the majority of research addresses optimisation and simulation independently, overlooking the feedback loop between scheduling decisions and stochastic operational performance.

This gap has prompted the development of simheuristics—a research domain that merges metaheuristic optimisation with simulation-based assessment—to incorporate stochastic variability directly into the optimisation process. Ref. [13] presented the concept and demonstrated its ability to capture uncertainty in logistics and transportation networks. Recent advancements, exemplified by [14], have employed hybrid simulation–optimisation frameworks to improve the resilience of berth scheduling. Nevertheless, implementations in bulk ports are limited, despite their increased susceptibility to random disturbances, including inconsistent shiploader availability, equipment malfunctions, and variable cargo-handling rates [15].

This study addresses these limitations by developing a hybrid optimisation–simulation approach for the Berth Allocation Problem in bulk ports. The methodology combines a Simulated Annealing (SA) metaheuristic with a discrete-event simulation model that dynamically assesses the effects of scheduling decisions on demurrage expenses and resource utilisation. In contrast to deterministic models, the suggested approach facilitates iterative feedback between the optimiser and the simulator, yielding resilient and probabilistically validated solutions amid operational uncertainty. The hybrid approach leverages the expanding corpus of simulation-based optimisation research [16,17] and modifies it to accommodate the stochastic and contractual characteristics of bulk terminal operations.

The main contributions of this work are fourfold:

- (1)

- To propose a stochastic berth scheduling framework integrating metaheuristic optimisation and discrete-event simulation;

- (2)

- To formalise a mathematical model that explicitly minimises demurrage costs under discrete berth and shiploader constraints;

- (3)

- To demonstrate the computational efficiency and robustness of the hybrid Simulated Annealing–Simulation framework against other metaheuristics such as GA and ACO;

- (4)

- To provide operational insights regarding berth and shiploader utilization under uncertainty, relevant for decision-making in real bulk ports.

The subsequent sections of this article are structured as follows: Section 2 examines the relevant literature on heuristic and simheuristic methodologies for berth allocation. Section 3 delineates the mathematical description of the problem and the hybrid optimisation–simulation framework. Section 4 presents computational experiments and comparative findings. Section 5 addresses ramifications, restrictions, and prospective extensions. Ultimately, Section 6 culminates in a synthesis of findings and recommendations for subsequent research endeavours.

2. Related Works

Research on the Berth Allocation Problem (BAP) has progressed through many methodological phases, demonstrating enhanced model complexity and realism. This review categorises previous investigations into four theme groups: (i) deterministic and precise optimisation models, (ii) metaheuristic techniques, (iii) discrete-event simulation models, and (iv) hybrid and simheuristic frameworks.

2.1. Deterministics and Exact Optimisation Models

Early research on the BAP primarily adopted deterministic and mathematically exact formulations based on Mixed-Integer Linear Programming (MILP) and Mixed-Integer Nonlinear Programming (MINLP). These models aim to find globally optimal berth assignments given fully known vessel arrival times, handling rates, and service durations.

Representative studies include [1,2,8], which proposed MILP-based formulations minimising vessel waiting time or total turnaround duration. These models were solved using commercial solvers such as CPLEX or Gurobi, ensuring optimality for small-scale instances. However, their performance deteriorates significantly when the number of vessels and berths increases or when uncertainty is introduced.

Subsequent deterministic works, such as [3], refined these formulations by incorporating spatial berth discretisation and multiple operational constraints. Nevertheless, the computational complexity of these exact approaches—classified as NP-hard—makes them unsuitable for real-time decision-making in dynamic port environments. Thus, deterministic optimisation serves as a baseline for benchmarking, rather than a practical solution method for large, stochastic systems.

2.2. Metaheuristic Techniques

To overcome the scalability limitations of deterministic approaches, numerous studies have explored metaheuristic algorithms that search for near-optimal solutions through stochastic exploration and iterative improvement. Unlike precise models, metaheuristics do not guarantee global optimality but offer significant advantages in computational speed and adaptability to complex, nonlinear problem spaces.

Several metaheuristic techniques have been applied to the BAP. In the case of employing Simulated Annealing (SA) to minimise total turnaround time, its robustness was demonstrated against local optima. Consequently, refs. [9,10] implemented Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO), respectively, focusing on vessel sequencing and congestion reduction. These approaches achieved substantial performance improvements compared with MILP-based models, particularly under variable vessel arrivals.

Recent developments also include hybridized or enhanced metaheuristics, such as Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO) and Tabu Search, which incorporate adaptive parameter tuning or memory-based strategies [14,18]. Metaheuristics, therefore, represent a flexible class of approximate algorithms that effectively address the computational intractability of deterministic models while maintaining solution quality across diverse operating conditions.

2.3. Discrete-Event Simulation in Port Operations

Discrete-Event Simulation (DES) is commonly used for modelling the uncertainty of port operations. Thus, modelling the sequence of vessel arrivals, equipment usage, and cargo handling events, DES enables analysts to assess the performance of different berth allocation strategies under uncertainty [19,20]. Consequently, simulation models provide flexibility to incorporate random events into the model, such as weather variations, equipment variability, and resource unavailability, which are not easy to represent in mathematical expressions [14]. Recent applications have extended DES to evaluate quay crane assignment, yard management, and integrated port logistics systems [21].

Rather than emphasizing a particular software environment such as FlexSim, recent research underscores the methodological value of the discrete-event paradigm itself. This paradigm enables dynamic performance assessment, sensitivity analysis, and probabilistic validation of scheduling strategies, which are essential for decision-making in bulk cargo operations where variability dominates. Studies by [15,17] illustrate how simulation models can be coupled with optimisation algorithms to replicate real-world operational uncertainty.

2.4. Hybrid and Simheuristic Frameworks

The integration of optimization and simulation has given rise to simheuristics, an approach that combines the search efficiency of metaheuristics with the realism of simulation-based evaluation [13,22]. Simheuristic frameworks iteratively evaluate candidate solutions within stochastic simulation environments, allowing feedback between deterministic optimisation and probabilistic assessment. This coupling enhances robustness and provides performance measures such as confidence intervals or probabilistic dominance.

Several studies have applied hybrid approaches to transportation and logistics systems [23,24], but their adoption in bulk port scheduling remains limited. Most existing hybrid models focus on container terminals, while bulk terminals—with their complex cargo handling systems and demurrage-driven objectives—have received comparatively little attention. Recent research trends advocate integrating metaheuristics such as SA, GA, and ACO with DES frameworks to represent uncertainty explicitly and improve the solution [25]. The present study builds upon this line of research by proposing a Simulated Annealing–Simulation hybrid model that explicitly minimises demurrage costs, a critical economic indicator unique to bulk port operations.

Table 1 summarises representative contributions from the literature, highlighting their methodological approach, objectives, and limitations. As shown, most studies neglect stochastic components or focus exclusively on container terminals. The present work addresses these limitations by proposing a simheuristic framework that integrates stochastic simulation into the optimisation process for bulk port berth allocation.

Table 1.

Summary of representative studies addressing the Berth Allocation Problem (BAP).

3. Materials and Methods

The Berth Allocation Problem (BAP) has been categorised into three types, discrete, continuous, and hybrid, according to Bierwirth and Meisel [3]. This study focuses specifically on the discrete BAP, in which the quay is divided into distinct sections or berths, each capable of accommodating only one vessel at a time. A schematic representation of this berth layout is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Representation of discrete BAP.

The study focuses on optimising vessel scheduling at bulk maritime terminals where shiploaders perform loading. Standard shiploader design comprises a telescopic boom, a belt conveyor, a tripper that redirects cargo from the source belt, and a gantry for mobile manoeuvrability. Shipowners commit to the port by notifying the anticipated arrival dates for loading, while ports, through contractual obligations, guarantee that operations will occur within the agreed window—the period labeled laytime. Deviations causing loading to exceed laytime trigger demurrage, a penalty imposed on the charterers and intended to offset the costs incurred by the vessel due to extended port stay.

In this context, the scheduling scenario involves assigning a sequence of vessels to be loaded by a set of available shiploaders. Notably, multiple shiploaders can simultaneously serve a single vessel, increasing operational flexibility. This study considers a realistic scenario of a bulk port located on Colombia’s Atlantic coast. The port includes a quay where vessels (labeled V1, V2, …) arrive and wait for berthing, three discrete berths (Berth 1, Berth 2, and Berth 3), and a set of shiploaders. The number of available shiploaders is equal to or greater than the number of berths. Upon a vessel’s arrival at the quay, port management determines berth availability: if a berth is free, the vessel is allowed to dock; otherwise, it must wait until a berth becomes available. The mathematical definition of the variables is in Table 2.

Table 2.

Notation and variable definitions.

3.1. Mathematical Model

The following assumptions are made in formulating the problem:

- •

- All berths are discrete, and any vessel can be berthed in any unoccupied section.

- •

- Multiple shiploaders can be assigned to a single vessel simultaneously.

- •

- There is a predefined maximum number of shiploaders that can serve each vessel.

- •

- Estimated times of vessel arrival and cargo volumes are known in advance.

- •

- Once assigned, a shiploader continues working with a vessel until loading is complete.

The total number of shiploaders is equal to or greater than the number of berths.

While [1] proposed a mixed-integer linear programming (MILP) model to minimize the total service time for vessels in port, this study aims to minimize the total demurrage cost. The formulation introduces additional constraints, making it a highly complex nonlinear optimization problem. Below is the formal structure of the discrete BAP model adapted for bulk port operations.

Objective Function:

Objective Function (1): minimizes the total demurrage cost of all vessels berthing at the port (Pi is the penalty cost of vessel i ∈ N).

The model constraints are described below:

Table 3.

Constraint description.

Table 3.

Constraint description.

| Constraint | Description |

|---|---|

| (2) | Ensures that the size of the berth is not exceeded. |

| (3) | Ensures that vessels do not surpass the maximum depth allowed for the berth. |

| (4) | Guarantees that each vessel is assigned to only one berth. |

| (5) | Ensures that vessels must arrive before they can be serviced. |

| (6)–(8) | Impose limitations to prevent overlapping between two vessels berthed at the port. |

| (9) | Ensures that if vessel i is before vessel j, the opposite condition cannot occur. |

| (10) | States that vessels must complete loading operations before leaving the port. |

| (11) | Ensures that shiploader q is assigned to vessel i in berth k. |

| (12)–(13) | Require that at least one shiploader be assigned; if a shiploader is allocated to a specific berth for a vessel, it ensures that the vessel utilizes that shiploader. |

| (14)–(15) | Specify that if shiploader q continues loading vessel j after attending vessel i, it must begin only once vessel i has departed the port. |

| (16)–(21) | Represent additional technical restrictions of the model. |

The proposed model was tested on small-scale instances inspired by real operational data using AMPL and CPLEX. However, as the problem size increases, the number of feasible assignments grows exponentially, making exact optimization computationally intractable.

The main contribution of this research lies in the simultaneous use of metaheuristics (Simulated Annealing) and discrete-event simulation to address the BAP. The Simulated Annealing algorithm determines vessel scheduling decisions, which are then fed into a simulation model built in FlexSim to evaluate system performance under uncertainty—specifically, shiploader utilization and berth occupancy rates.

3.2. Metaheuristics in a Simulation Model

This section articulates the Simulated Annealing (SA) metaheuristic as quantitatively formulated for addressing the Berth Allocation Problem (BAP) at bulk ports. Subsequently, the specific algorithmic architecture of SA adopted herein is presented, together with the corresponding procedure for generating candidate solutions within the overarching optimization schema.

Simulated Annealing Algorithm—General Structure.

| Begin Require: List control parameters (To, L, α) X ← Xo; X* ← Xo; T ← To; iteration ← 1; While (0.005 ≤ T) Generate a new solution X’; F(X’) − F(X) ← ΔE; If (ΔE ≤ 0) then X ← X’; X* ← X; Else p ← e(−∆E/T); End if If (N ≤ p) then X ← X’; iteration ← iteration + 1; End |

To implement the SA algorithm, several parameters were defined based on the problem characteristics and computational testing. A factorial experimental design was conducted to determine the best combination of SA parameters when interfaced with FlexSim Software 2022. The primary performance measure used to evaluate solution quality was the total demurrage cost, as this directly aligns with the objective function of the problem.

The initial temperature T0 was set to 100 to allow for an initial acceptance rate above 85% of feasible but suboptimal solutions. A chain length of 2 was defined for each temperature level, and the cooling constant alpha was set to 0.9. Table 4 summarises the factor levels considered for the cooling rate and initial temperature in the experimental design.

Table 4.

Simulated Annealing setup.

The initial solution X0 represents a feasible berth–vessel assignment generated through a greedy initialization heuristic. Vessels are first sorted by arrival time, and each vessel is assigned to the earliest available berth and compatible shiploader that satisfies draft and length constraints. The resulting schedule constitutes the initial state of the SA search, providing a valid yet suboptimal reference for subsequent improvement.

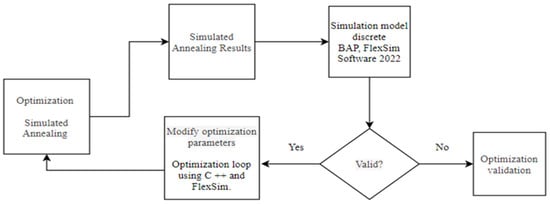

To capture the stochastic nature of port operations, the discrete BAP simulation model was built in FlexSim Software 2022 and linked to the Simulated Annealing algorithm. The integration was achieved through a structured optimization loop using C++ as the coordinating platform. The loop operates as follows:

- •

- FlexSim is launched from a C++ script with parameter values passed via command-line arguments.

- •

- Upon model initialisation, the OnModelOpen trigger in FlexSim reads an input file containing the vessel scheduling decisions generated by the SA algorithm.

- •

- FlexSim executes the simulation using the provided schedule and collects performance metrics—such as total demurrage cost, shiploader utilisation, and berth occupancy.

- •

- These performance metrics are written to an output file.

- •

- C++ reads the output file and updates the SA search process based on the new objective function value.

This integration enables dynamic feedback between the optimisation algorithm and the simulation model, creating a closed-loop optimisation architecture. A flowchart illustrating this hybrid SA–simulation framework is presented in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Flowchart of simulated annealing with discrete simulation.

4. Results

The principal performance measure employed in this investigation is the aggregation of demurrage charges, since it serves as the most immediate gauge for efficaciously curtailing financial liabilities associated with breaches of laytime stipulations. The methodological framework was executed and validated via FlexSim Software 2022, hosted on a desktop configuration featuring an Intel® Core i7 microarchitecture and 8.0 GB of system memory.

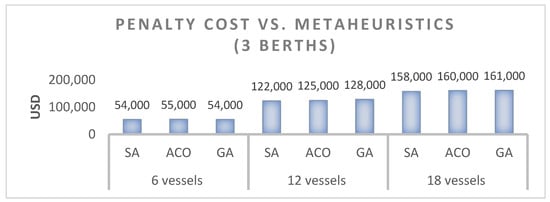

An array of computational protocols was orchestrated to scrutinize the efficacy of the Simulated Annealing (SA) paradigm when synchronized with discrete-event simulation. Three discrete experimental sets were executed, each corresponding to fleets of 6, 12, and 18 vessels, respectively. The performance of the SA–Simulation amalgamation was benchmarked against SA in isolation as well as two other stochastic heuristics, namely, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Ant Colony Optimisation (ACO). The comparative assessment drew on previous data reported by [27], in which only genetic algorithms were operated in a static ranking environment devoid of simulation.

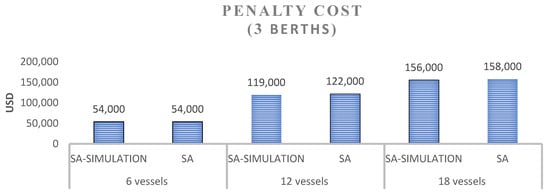

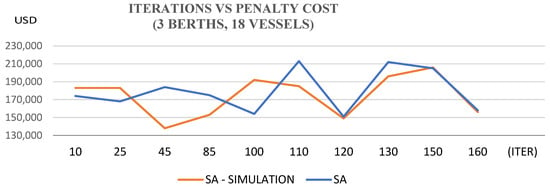

Demurrage charges per simulation run are plotted in Figure 3 for the three terminal positions assessed, contrasting the output of the SA, GA, and ACO heuristics. The validity of incorporating simulation is substantiated in Figure 4, which juxtaposes the penalisation incurred by the SA–Simulation framework against the baseline SA run. Figure 5 traces the iterative contraction of demurrage charges in the 18-vessel configuration, involving three concurrently employed shiploaders.

Figure 3.

Penalization costs of the SA, ACO and GA.

Figure 4.

Penalization costs of the SA vs. SA–Simulation.

Figure 5.

Iterations vs. penalty cost (3 variables and 18 vessels).

Table 5 presents the mean and standard deviation of the demurrage costs for each of the three instance sizes under both SA and SA–Simulation. Table 6 details the berthing schedule of the vessels and the corresponding shiploader assignments for the 18-vessel case with 160 SA iterations. Finally, Table 7 reports the utilisation percentages of shiploaders and berths, derived from the simulation model under uncertainty.

Table 5.

Mean and standard deviation of the SA vs. SA–Simulation.

Table 6.

Schedule of the vessel in each berth.

Table 7.

Percentage use of shiploaders and percentage use of berths.

Figure 3 and Figure 4 indicate that for the scenario involving three shiploaders and eighteen vessels, there is no substantial difference in demurrage costs between SA–Simulation and SA alone in terms of best solution values. However, SA–Simulation consistently demonstrates lower mean costs and standard deviations, indicating improved robustness under uncertainty.

More importantly, the simulation-based approach enables the evaluation of performance measures—such as resource utilisation rates—that cannot be derived from optimisation alone. This integration offers richer operational insights and supports better-informed decision-making for real-world port management.

Statistical Validation

To evaluate the effect of simulation coupling, the results were validated through 30 independent replications of the discrete-event simulation model. Table 8 presents the average, minimum, and maximum demurrage cost across all replications.

Table 8.

Replications results.

The small standard deviation (<2% of the mean) confirms the stability and robustness of the hybrid model. In addition, a one-way ANOVA test (p < 0.01) confirmed that the SA–DES performance was statistically different from the other heuristics, highlighting the significance of incorporating stochastic simulation feedback into the optimization process.

5. Discussion

The proposed Simulated Annealing–Discrete Event Simulation (SA–DES) framework offers a novel and competitive approach for addressing the Berth Allocation Problem (BAP) in bulk ports under uncertainty. The results revealed a substantial 28.7% reduction in total demurrage cost compared to a deterministic MILP formulation and a 21.3% improvement over standalone SA. These gains demonstrate the strength of combining metaheuristic search with stochastic feedback from simulation, a direction that has recently become prominent in port optimisation literature.

Recent studies have increasingly emphasised the use of hybrid and intelligent optimisation approaches to tackle the inherent stochasticity of berth allocation. For instance, ref. [18] introduced a Diffused Memetic Optimiser (DMO) capable of responding to disruptions through adaptive scheduling, while [28] developed a Heuristic Decoding Method integrated with a time-variant quay crane assignment model, improving large-scale computational efficiency. Similarly, ref. [29] proposed a Memetic Algorithm that integrates clustering-based local search for enhanced reactivity. These models demonstrate that hybridisation and adaptive learning significantly outperform classical mathematical formulations in both quality and response time.

Compared to these recent advancements, the proposed SA–DES contributes an alternative hybridisation mechanism that embeds simulation-driven feedback within the metaheuristic loop. While memetic and neural approaches (e.g., [30]) rely on algorithmic adaptation through learned heuristics, the present framework introduces operational realism by recalculating service durations and vessel handling times dynamically during the optimisation process. This capability allows the model to reproduce port congestion effects and vessel delays—conditions that are often ignored in purely computational models—without compromising computational feasibility.

Moreover, while Chang et al. (2024) [31,32] explored cooperative and game-theoretic formulations emphasising coordination among multiple ports or agents, the SA–DES model focuses on intra-port efficiency under stochastic operational conditions. This distinction positions the model as a practical decision-support tool for terminal operators managing variable arrivals, resource limitations, and fluctuating shiploader performance.

From a computational standpoint, the SA–DES achieved convergence within approximately 150 iterations, maintaining execution times under five minutes for realistic bulk port scenarios. This performance is consistent with the efficiency benchmarks reported by recent evolutionary approaches (e.g., [18,33]), confirming that hybridisation can improve both robustness and runtime stability. The low standard deviation (<2%) across 30 simulation replications further validates the reliability of the results under stochastic conditions.

Despite its promising performance, this study acknowledges certain limitations. First, the simulation model assumes a fixed number of shiploaders, without dynamic reassignment across berths. Second, environmental factors such as tide level, weather delays, or equipment failures were not included in the current model. Future research could extend the framework by integrating multi-agent simulation, machine learning-based parameter tuning, or multi-objective optimisation (e.g., balancing demurrage cost, fuel consumption, and service level). Moreover, incorporating real-time data streams from port information systems could enable continuous model calibration and near-real-time decision support.

6. Conclusions

This study proposed a hybrid optimisation–simulation framework integrating Simulated Annealing (SA) with Discrete-Event Simulation (DES) to address the Berth Allocation Problem (BAP) in bulk ports under demurrage constraints. The integration aimed to capture both the stochastic operational variability of port logistics and the optimization efficiency of metaheuristic algorithms.

The results demonstrated that the proposed SA–DES model achieved significant improvements over classical optimization approaches. In particular, it reduced total demurrage costs by 28.7% compared with the MILP baseline and by 21.3% relative to the standalone SA model. The hybrid model also maintained a low computational time (<5 min), confirming its suitability for practical decision-making in real port operations. Statistical validation through multiple simulation replications revealed a low variance (<2%), confirming the robustness of the proposed framework under uncertainty.

Beyond quantitative performance, this research provides methodological and managerial contributions. Methodologically, it extends the traditional SA approach by embedding stochastic feedback from the simulation component, enabling adaptive decision-making as vessel arrival and service conditions change dynamically. From a managerial perspective, the framework offers port operators a decision-support tool capable of visualising berth occupancy, vessel sequencing, and loader utilisation before implementation—enhancing operational reliability and reducing idle times.

However, the study acknowledges some limitations. The current model assumes fixed numbers of berths and shiploaders and does not account for real-time weather or tide disruptions. Future research could address these aspects by incorporating multi-agent simulation, real-time data integration, and multi-objective optimization to simultaneously minimize demurrage, energy use, and service delays. Moreover, exploring machine learning-based parameter tuning could enhance convergence efficiency and adaptability to larger-scale port systems.

In summary, this work contributes to the ongoing advancement of hybrid simulation–optimization approaches in maritime logistics. By combining analytical rigor with operational realism, the SA–DES framework represents a scalable, data-driven tool capable of supporting decision-makers in achieving more resilient and cost-efficient port operations.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.D.-D. and D.M.-C.; Methodology, E.D.-D.; Formal analysis, D.M.-C.; Investigation, D.M.-C.; Data curation, D.M.-C.; Writing—original draft, A.M.-M.; Writing—review & editing, A.M.-M.; Supervision, A.M.-M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to the experimental setup of the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Umang, N.; Bierlaire, M.; Vacca, I. Exact and Heuristic Methods to Solve the Berth Allocation Problem in Bulk Ports. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2013, 54, 14–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhrkal, K.; Zuglian, S.; Ropke, S.; Larsen, J.; Lusby, R. Models for the Discrete Berth Allocation Problem: A Computational Comparison. Transp. Res. Part E Logist. Transp. Rev. 2011, 47, 461–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bierwirth, C.; Meisel, F. A Survey of Berth Allocation and Quay Crane Scheduling Problems in Container Terminals. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2010, 202, 615–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, C.; Guo, J.; Yang, Y. Multi-Objective Hybrid Genetic Algorithm for Quay Crane Dynamic Assignment in Berth Allocation Planning. J. Intell. Manuf. 2011, 22, 471–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, V.H.; Costa, T.S.; Oliveira, A.C.M.; Lorena, L.A.N. Model and Heuristic for Berth Allocation in Tidal Bulk Ports with Stock Level Constraints. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2011, 60, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, S.; Lu, C.-C.; Hsieh, J.-H.; Lin, H.-C. A Dynamic and Flexible Berth Allocation Model with Stochastic Vessel Arrival Times. Netw. Spat. Econ. 2019, 19, 903–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Dong, M.; Li, X.; Liu, H.; Wang, W. Cooperative Optimization of Shore Power Allocation and Berth Allocation: A Balance between Cost and Environmental Benefit. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 279, 123816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robenek, T.; Umang, N.; Bierlaire, M.; Ropke, S. A Branch-and-Price Algorithm to Solve the Integrated Berth Allocation and Yard Assignment Problem in Bulk Ports. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 235, 399–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, L.; Wang, J.; Zheng, J. Berth Allocation Problem with Uncertain Vessel Handling Times Considering Weather Conditions. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2021, 158, 107417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osaba, E.; Villar-Rodriguez, E.; Del Ser, J.; Nebro, A.J.; Molina, D.; LaTorre, A.; Suganthan, P.N.; Coello Coello, C.A.; Herrera, F. A Tutorial On the Design, Experimentation and Application of Metaheuristic Algorithms to Real-World Optimization Problems. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2021, 64, 100888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tengku-Adnan, T.; Sier, D.; Ibrahim, R.N. Performance of Ship Queuing Rules at Coal Export Terminals. In Proceedings of the 2009 IEEE International Conference on Industrial Engineering and Engineering Management, Hong Kong, China, 8–11 December 2009; pp. 1795–1799. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S.; Xu, A.; Song, W.; Li, X. Structural Optimization of the Production Process in Steel Plants Based on Flexsim Simulation. Steel Res. Int. 2019, 90, 1900201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juan, A.A.; Faulin, J.; Grasman, S.E.; Rabe, M.; Figueira, G. A Review of Simheuristics: Extending Metaheuristics to Deal with Stochastic Combinatorial Optimization Problems. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2015, 2, 62–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de León, A.D.; Lalla-Ruiz, E.; Melián-Batista, B.; Moreno-Vega, J.M. A Simulation–Optimization Framework for Enhancing Robustness in Bulk Berth Scheduling. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2021, 103, 104276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheimanoff, N.; Féniès, P.; Kitri, M.N.; Tchernev, N. Exact and Metaheuristic Approaches to Solve the Integrated Production Scheduling, Berth Allocation and Storage Yard Allocation Problem. Comput. Oper. Res. 2023, 153, 106174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kastner, M.; Nellen, N.; Schwientek, A.; Jahn, C. Integrated Simulation-Based Optimization of Operational Decisions at Container Terminals. Algorithms 2021, 14, 42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.; Li, W.; Li, C. A Dynamic Simulation Framework Based on Hybrid Modeling Paradigm for Parallel Scheduling Systems in Warehouses. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2024, 133, 102921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulebenets, M. A Diffused Memetic Optimizer for Reactive Berth Allocation and Scheduling at Marine Container Terminals in Response to Disruptions. Swarm Evol. Comput. 2023, 80, 101334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legato, P.; Mazza, R.M.; Gullì, D. Integrating Tactical and Operational Berth Allocation Decisions via Simulation–Optimization. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2014, 78, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, F. The Berth Allocation Problem in Bulk Terminals under Uncertainty. Oper. Res. Perspect. 2025, 14, 100334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neagoe, M.; Hvolby, H.-H.; Taskhiri, M.S.; Turner, P. Using Discrete-Event Simulation to Compare Congestion Management Initiatives at a Port Terminal. Simul. Model. Pract. Theory 2021, 112, 102362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leithner, M.; Fikar, C. A Simulation Model to Investigate Impacts of Facilitating Quality Data within Organic Fresh Food Supply Chains. Ann. Oper. Res. 2022, 314, 529–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauri, G.R.; Oliveira, A.C.M.; Lorena, L.A.N. A Hybrid Column Generation Approach for the Berth Allocation Problem. In Proceedings of the Evolutionary Computation in Combinatorial Optimization, Naples, Italy, 26–28 March 2008; van Hemert, J., Cotta, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2008; pp. 110–122. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, P.; Cai, L.; Guo, W.; Li, W. A Proactive-Reactive Approach for Dynamic Hybrid Berth Allocation Problem Considering Vessels Arrival Delay. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Symposium Series on Computational Intelligence (SSCI), Mexico City, Mexico, 5–8 December 2023; pp. 1753–1758. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, Y.; Wang, J.; Liu, Z.; Zou, M. From Heuristics to Multi-Agent Learning: A Survey of Intelligent Scheduling Methods in Port Seaside Operations. Mathematics 2025, 13, 2744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzekri, H.; Alpan, G.; Giard, V. Integrated Laycan and Berth Allocation Problem with Ship Stability and Conveyor Routing Constraints in Bulk Ports. Comput. Ind. Eng. 2023, 181, 109341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atencio, F.N.; Casseres, D.M. A Comparative Analysis of Metaheuristics for Berth Allocation in Bulk Ports: A Real World Application. IFAC-Pap. 2018, 51, 1281–1286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.-S.; Huang, T.; Zhao, B.; Gong, Y.; Liu, J. Continuous Berth Allocation and Time-Variant Quay Crane Assignment: Memetic Algorithm with a Heuristic Decoding Method. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 3387–3401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J. Nearest-Better Clustering-Based Memetic Algorithm for Berth Allocation and Crane Assignment Problem. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 82247–82260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korekane, S.; Nishi, T.; Tierney, K.; Liu, Z. Neural Network Assisted Branch and Bound Algorithm for Dynamic Berth Allocation Problems. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2024, 319, 531–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.-C.; Lin, M.-H.; Tsai, J.-F. An Optimization Approach to Berth Allocation Problems. Mathematics 2024, 12, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin-Iradi, B.; Pacino, D.; Røpke, S. The Multiport Berth Allocation Problem with Speed Optimization: Exact Methods and a Cooperative Game Analysis. Transp. Sci. 2020, 56, 972–999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ting, C.; Wu, K.-C.; Chou, H. Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for the Berth Allocation Problem. Expert Syst. Appl. 2014, 41, 1543–1550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).